African American Heritage

Black Arts Movement (1965-1975)

The Black Arts Movement was a Black nationalism movement that focused on music, literature, drama, and the visual arts made up of Black artists and intellectuals. This was the cultural section of the Black Power movement, in that its participants shared many of the ideologies of Black self-determination, political beliefs, and African American culture.

The Black Arts Movement started in 1965 when poet Amiri Baraka [LeRoi Jones] established the Black Arts Repertory Theater in Harlem, New York, as a place for artistic expression. Artists associated with this movement include Audre Lorde, Ntozake Shange, James Baldwin, Gil Scott-Heron, and Thelonious Monk. Records at the National Archives related to the Black Arts Movement primarily focus on individual artists and their interaction with various Federal agencies.

Search the Catalog for Records on the Black Arts Movement

Prominent Figures of the Black Arts Movement at the National Archives

Maya Angelou

Amiri Baraka

James Baldwin

Gwendolyn Brooks

Nikki Giovanni

Lorraine Hansberry

Maya Angelou (April 4, 1928 - May 28, 2014)

Marguerite “Maya” Johnson was born in St. Louis, Missouri. She was a writer, poet, activist, and actress. Angelou was exposed to the Civil Rights Movement and African culture during the 1960s. In the 1970s, she began her writing career, focusing on stories and anecdotes based on her life, Blackness, and feminism. In 1993, Angelou became the first poet to recite a poem at a presidential inauguration since 1961. Records at the National Archives related to Maya Angelou consist of appearances at Federal events and her time on tour with a production of Porgy & Bess .

Social Networks and Archival Context - Maya Angelou

Angelou Reciting "On the Pulse of Morning" at the Inauguration of President Clinton, January 20, 1993; Photo ID: P00162_24; William J. Clinton Presidential Library

Amiri baraka [everett leroi jones] (october 7, 1934 - january 9, 2014).

Amiri Baraka was born Everett LeRoi Jones in Newark, New Jersey on October 7, 1934. In 1954 he earned a bachelor’s degree in English at Howard University. Following graduation, Jones joined the military and served three years in the Air Force. After receiving a honorable discharge, he settled in Greenwich Village in New York and began to interact with various musicians and artists. While living in New York, Jones became a well-respected novelist and poet for his writings on Black liberation and white racism. He also met Hettie Cohen, a Jewish writer. Later on, the two married and co-edited the literary magazine Yugen . They also founded Totem Press, which focused on publishing the works of political activists. Jones taught at several colleges and universities before changing his name to Amiri Baraka. Baraka continued to publish literary works for over 50 years until his death in 2014. Records at the National Archives pertaining to Amiri Baraka include a sound recording of Baraka reciting a poem that was considered to be an un-American activity.

Social Networks and Archival Context - Amiri Baraka

James Baldwin (August 2, 1924 - December 1, 1987)

James baldwin and marlon brando at the march on washington, august 28, 1963 ( naid 542060 ).

James Arthur Baldwin was born August 2, 1924 in Harlem, New York. After graduating from high school in 1942, Baldwin began writing. In 1953, he published his first novel Go Tell It on the Mountain . Prior to releasing his first novel, Baldwin chose to leave America and move to France because of his dissatisfaction with the open racism and homophobia in the United States. In 1962, he visited the United States in order to participate in the the Civil Rights Movement, namely attending the March on Washington (seen in the photo). During the height of the struggle for Black equality, Baldwin was widely known for his militant essays that illustrated the social and economic plight of Black Americans. His writings addressed the issues of race but also mentioned the complexity of homosexuality and sexual orientation among the Black experience in the U.S. After the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968, Baldwin returned to France and continued writing until his death in 1987. Records at the National Archives pertaining to James Baldwin include moving images from the Peace Corps, the Agency for International Development and an interview with Pulitzer Prize winner Gwendolyn Brooks.

Social Networks and Archival Context - James Baldwin

Gwendolyn Brooks (June 7, 1917 to December 3, 2000)

Gwendolyn Brooks was an American poet and teacher and is known as the first African American woman to win a Pulitzer when she was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry for her work Annie Allen (1950). Brooks was born on June 7, 1917 in Topeka, Kansas. Six weeks after her birth, the Brooks family moved to Chicago. Growing up in Chicago and attending majority white, then Black, and then integrated schools gave Brooks a varied perspective on racial dynamics in America which would later come to influence her future work. In the 1940s Brooks became heavily involved in attending poetry workshops in Chicago, in particular workshops organized by Inez Cunningham Stark. World renowned poet Langston Hughes stopped by one of these workshops and after hearing her recite her poem "The Ballad of Pearl May Lee” he became a fan of her work and acted as her mentor.

She published several works of poetry including A Street in Bronzeville (1945), and In the Mecca (1968) which both earned critical acclaim. One of her better known poems “We Real Cool” was published in her third book of poetry, The Bean Eaters (1960), and is widely studied in literature classes and re-printed in literature textbooks. Brooks taught poetry and writing around the country at several well known colleges and universities such as the University of Chicago, Columbia University, and Elmhurst College and continued on in that respect until her death on December 3, 2000 in her hometown of Chicago.

Social Networks and Archival Context - Gwendolyn Brooks

Nikki Giovanni (June 7, 1943)

Nikki Giovanni is an American poet, writer, commentator, activist, and educator. Giovanni was born as Yolande Cornelia "Nikki" Giovanni, Jr. on June 7, 1943 in Knoxville, Tennessee. She attended Fisk University receiving a B.A. in History and later went on to attend graduate school at the University of Pennsylvania and Columbia University. Giovanni’s work covers topics ranging from race and social issues explored through poetry anthologies, poetry recordings, and nonfiction essays. She was a prominent figure in the Black Arts Movement of the late 1960s and her work was heavily influenced by the Civil Rights Movement and the Black Power Movement. Her poetry during this period in Black Feeling, Black Talk and Black Judgement , reflected a strong African American perspective and because of this she was hailed as the "Poet of the Black Revolution." Over the years Giovanni would shift her focus to children’s literature, human relationships, women writers, and hip hop. Currently, Giovanni works as an University Distinguished Professor at Virginia Tech where she teaches courses on writing and poetry.

Social Networks and Archival Context - Nikki Giovanni

Lorraine Hansberry (May 19, 1930 - January 12, 1965)

A native of Chicago, Illinois Lorraine Hansberry is known as one of the most significant and influential playwrights of the 20th century. She wrote the landmark play A Raisin in the Sun , which opened at Ethel Barrymore Theatre in New York City in 1959. A Raisin in the Sun was the first play written by an African American woman to be produced on Broadway. The play depicted the characteristics, emotions, and struggles of an urban Black family and eventually won a New York Drama Critics Circle Award and four Tonys for best play, director, actress and actor. Because of the success of the play, Hansberry was credited for breaking down racial barriers on Broadway and ushering in a new opportunity for African American women playwrights.

In 1961, she wrote the screenplay to A Raisin in the Sun in order to turn the play into a movie. The movie staring Sidney Poitier and Ruby Dee became as successful as the play and allowed the actors to gain considerable recognition for their roles. Hansberry’s second play, and only other production put on in her lifetime, The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window ran for 101 performances. The day that the play closed was the same day that Hansberry died at the age of 34 from pancreatic cancer. Hansberry had many other works, including writings for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) , and contributions to lesbian rights organizations. Records at the National Archives pertaining to Lorraine Hansberry include moving images among the records of the Agency for International Development and sound recordings of a radio broadcast.

Social Media and Archival Contexts - Lorraine Hansberry

BlackPast is dedicated to providing a global audience with reliable and accurate information on the history of African America and of people of African ancestry around the world. We aim to promote greater understanding through this knowledge to generate constructive change in our society.

The black arts movement (1965-1975).

The Black Arts Movement was the name given to a group of politically motivated black poets, artists, dramatists, musicians, and writers who emerged in the wake of the Black Power Movement. The poet Imamu Amiri Baraka is widely considered to be the father of the Black Arts Movement, which began in 1965 and ended in 1975.

After Malcolm X was assassinated on February 21, 1965, those who embraced the Black Power movement often fell into one of two camps: the Revolutionary Nationalists, who were best represented by the Black Panther Party, and the Cultural Nationalists. The latter group called for the creation of poetry, novels, visual arts, and theater to reflect pride in black history and culture. This new emphasis was an affirmation of the autonomy of black artists to create black art for black people as a means to awaken black consciousness and achieve liberation.

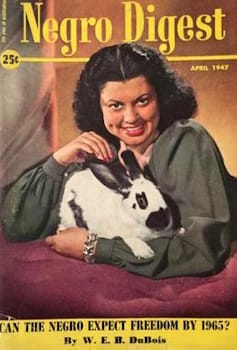

The Black Arts Movement was formally established in 1965 when Baraka opened the Black Arts Repertory Theater in Harlem. The movement had its greatest impact in theater and poetry. Although it began in the New York/Newark area, it soon spread to Chicago, Illinois, Detroit, Michigan, and San Francisco, California. In Chicago, Hoyt Fuller and John Johnson edited and published Negro Digest (later Black World ), which promoted the work of new black literary artists. Also in Chicago, Third World Press published black writers and poets. In Detroit, Lotus Press and Broadside Press republished older works of black poetry. These Midwestern publishing houses brought recognition to edgy, experimental poets. New black theater groups were also established. In 1969, Robert Chrisman and Nathan Hare established The Black Scholar , which was the first scholarly journal to promote black studies within academia.

There was also collaboration between the cultural nationalists of the Black Arts Movement and mainstream black musicians, particularly celebrated jazz musicians including John Coltrane , Thelonious Monk , Archie Shepp, and others. Cultural nationalists saw jazz as a distinctly black art form that was more politically appealing than soul, gospel, rhythm and blues, and other genres of black music.

Although the creative works of the movement were often profound and innovative, they also often alienated both black and white mainstream culture with their raw shock value which often embraced violence. Some of the most prominent works were also seen as racist, homophobic, anti-Semitic, and sexist. Many works put forth a black hyper masculinity in response to historical humiliation and degradation of African American men but usually at the expense of some black female voices.

The movement began to fade when Baraka and other leading members shifted from Black Nationalism to Marxism in the mid-1970s, a shift that alienated many who had previously identified with the movement. Additionally Baraka, Nikki Giovanni , Gil Scott-Heron , Maya Angelou , and James Baldwin achieved cultural recognition and economic success as their works began to be celebrated by the white mainstream.

The Black Arts Movement left behind many timeless and stirring pieces of literature, poetry, and theater. Ironically despite the male-dominated nature of the movement, several black female writers rose to lasting fame including Nikki Giovanni, Sonia Sanchez , Ntozake Shange , Audre Lorde , June Jordan , among others. Additionally, the Black Arts Movement helped lay the foundation for modern-day spoken word and hip-hop.

Do you find this information helpful? A small donation would help us keep this available to all. Forego a bottle of soda and donate its cost to us for the information you just learned, and feel good about helping to make it available to everyone.

BlackPast.org is a 501(c)(3) non-profit and our EIN is 26-1625373. Your donation is fully tax-deductible.

Cite this entry in APA format:

Source of the author's information:.

Darlene Clark Hine, et al., The African American Odyssey (Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson, 2010); Thomas Aiello, “Black Arts Movement,” Encyclopedia of African American History, 1896 to the Present: From the Age of Segregation to the Twenty-first Century , ed. Paul Finkelman (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008).

Your support is crucial to our mission.

Donate today to help us advance Black history education and foster a more inclusive understanding of our shared cultural heritage.

Perspective

Actualité en histoire de l’art

Accueil Versions originales 2 Works Research and Imagine the American...

Research and Imagine the American Black Art Since 2005

Entrées d’index, mots-clés : , keywords: , noms de lieux : , personnes citées :, texte intégral.

1 One hundred years ago, author, editor and civil right activist Freeman Henry Morris Murray published Emancipation and the Freed in American Sculpture (1916), a pioneering study of the depictions of peoples of African descent in art. Although Murray’s primary focus was on figural works produced by some of the leading (i.e. white) American and European sculptors in the latter half of the nineteenth century, his sculptural survey also included works by several important African American artists (specifically, Mary Edmonia Lewis and Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller) and, thus, marked his book as one of the very first histories and critical studies of black American art ( Murray , 1916).

2 Since Murray’s publication the art-historical literature on black artists, their artistic production, the aesthetics of racial difference and cultural distinctiveness, and the black image has grown incrementally, from a rare and happenstance phenomenon at the beginning of the twentieth century to a relatively common occurrence in the first decades of the twenty-first. A non-scientific method of gauging this proliferation of art-historical scholarship on African American artists and their works would be a simple comparison, say, between 1915 and 2015, of the frequency with which known African American artists are referenced in scholarly and popular literature. For example, in 1915 probably the names of only three black artists – William Edouard Scott, Henry Ossawa Tanner, and Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller – would have appeared more than once in newspapers and art journals nationwide. In contrast, in 2015 no listing of significant, contemporary artists would be considered accurate without Dawoud Bey, Mark Bradford, Nick Cave, Renee Cox, Theaster Gates, David Hammons, Lyle Ashton Harris, Rashid Johnson, Glenn Ligon, Steve McQueen, Kerry James Marshall, Julie Mehretu, Wangechi Mutu, Chris Ofili, William Pope.L, Lorna Simpson, Hank Willis Thomas, Mickalene Thomas, Kara Walker, Carrie Mae Weems, Kehinde Wiley, and Fred Wilson, among many other black artists of note.

3 In thinking about a historiography of African American art studies, it is important not to adhere too strictly to a conventional definition of art history: that is, a body of scholarship that, usually in the form of an article, treatise, thesis, or monograph, studies visual production in its historical and/or cultural contexts. African American art histories have not only been produced in these standard ways, but also in less overtly academic formats, such as exhibition catalogues, art gallery and museum publications, periodical art reviews, cultural criticism, and literary anthologies. The breadth and variety of these art-historical and critical studies of black artistic production encourage a broader scope and far more adaptable modes of investigation from scholars: approaches to research that not only take into account the blinders that most of the academy has historically worn when it came to seeing and appreciating African American artists and artistry, but also taking into account those unexpected sources and hidden archives – far off the treaded paths that art historians normally embark upon – in which black art histories can be rediscovered and reimagined.

4 Not unlike other chronological, national, or culture-specific studies in art history, African American art histories fulfill many objectives. Apart from bringing greater scholarly attention to the lives and careers of individual artists, describing certain historical moments or periods during which artists and patrons coalesce around particular ideas and stylistic sensibilities, or charting the contours of this particular subfield (and frequently questioning its very existence), historians of black visual culture scrutinize and visually deconstruct specific works of art. Such close readings invariably involve a quest for meaning, revealing artistic intent, and putting into words the art object’s affinities with a particular style or visual idiom. A matter of endless debates and conceptual disagreements, the question of the necessity of a distinctive African American or black category in art scholarship infiltrates the works of virtually every historian who ventures into this subfield, from Benjamin G. Brawley’s early twentieth-century musings on “Negro Genius,” to Derek C. Maus’ and James J. Donahue’s early twenty-first-century considerations of art and identity in the post-Civil Rights period ( Brawley , 1918; Maus, Donahue , 2014).

5 Among the many topics and theoretical directions African American art-historical studies have touched upon in the past decade, five themes and/or conceptual routes have produced an abundance of new scholarship and, thus, are prime for discussion. These five themes are: the two black movements (“The Harlem Renaissance” and “The Black Arts Movement”); Feminine - masculine - feminine; the Post-black ( noirceur chimérique ou l'art noir sans négritude ); the Insider outsiders; and the revised histories. In the realm of those aforementioned studies that focus on philosophically cohesive historical moments, many revolve around two black cultural movements: 1) the early twentieth-century project known as the Harlem Renaissance, and 2) the circa 1960s and 1970s cultural insurgency popularly known as the Black Arts Movement. These two “black movements,” approximately forty years apart from one another, collectively generate a strain of art-historical scholarship that, since the late twentieth century, has significantly reshaped earlier interpretations of these two cultural nationalist uprisings, by way of a greater emphasis on each movement’s nascent gender and sexual politics, their respective occasions for global outreach, and their mutations via early- and mid-twentieth-century mass media.

6 Parallel to the amplified presence of African American women writers in late twentieth-century American literature, art practitioners and historians throughout the African diaspora increasingly came to terms in their respective works with persistent questions of gender, sexuality, racial and cultural blackness, as well as their often uneasy interrelationships. These theoretical concerns, along with a new disciplinary commitment to highlighting the contributions of black women in art history and visual culture, have significantly reshaped African American art studies. A preponderance of African American art-historical studies in this period grappled with these themes and the ethical dilemmas they imposed upon audiences for art and, intentionally improvising upon the title of one of Jean-Luc Godard’s film classics, I make my subheading for this discussion feminine-masculine-feminine; a kind of methodological coda for this direction in art research, alluding here to the gender interdependency and, in particular, to the feminist focus of recent scholarship.

7 A popular topic in African American art scholarship over the past decade is the concept of a “post-black” aesthetic in contemporary art. Manifested in the actual examples of “post-black” art – rather than in the term’s connotations of a total departure from racial and/or cultural blackness – is a parallel (or “shadow”) racial/cultural preoccupation: one which privileges a kind of playfulness, or an irreverence, with regards to identity, history, and/or culture. Although art historians and critics who have written about this noirceur chimérique have tended to keep an objective distance when chronicling this phenomenon, many scholars are not as dispassionate, exploring instead the philosophical pitfalls of embracing racial ambiguities, or the broader political implications of taking a more inventive attitude toward black history. Very much like the research that has developed around the other African American art topics discussed in this essay, most “post-black” studies approach the topic without an a priori agenda that views this phenomenon, “l’art noir sans négritude,” uncritically.

8 Coinciding with the contemporary art scene’s heightened appreciation for works by socially marginalized, non-academically trained visual artists, art historians and theoreticians have begun to look closely at these part-artistic, part-sociological practices, from providing biographical information and career trajectories for these “insider outsiders,” to positing cultural and social theories about the artistic appeal of this work. Since African American artists figure prominently in this group, as do artists located mostly in the American South, much of the research is understandably indebted to critical race theory and cultural hypotheses that address center/periphery social dynamics.

9 Finally, a lot of the recent research in African American art history hasn’t been so much directed toward particular topics or a set of theoretical concerns, as fundamentally revising or offering correctives to an extant art history. These “historical revisions” have taken many forms, including alternative approaches to the art survey, multi-volume or multi-authored studies, and thematic investigations based on art genres, styles, or historical occurrences. Like the other categories of recent scholarship, monographic studies – usually in the form of exhibition catalogues published in collaboration with art galleries and museums – readily lend themselves to historical revisions, either providing augmented histories of recognized art-world figures, or introducing relatively unknown individuals to the art-viewing public. A more detailed description of each of these art-historical topics follows.

Two Black Movements: “The Harlem Renaissance” and “The Black Arts Movement”

- 1 Fully developed but relatively concise accounts of the Harlem Renaissance and the Black Arts Moveme (...)

10 The Harlem Renaissance or, as it was popularly referred to the 1920s and 1930s, the “New Negro Arts Movement,” was an interlude in the larger span of modern history that most scholars agree was a period of major artistic flowering among African Americans, celebrated and championed by an assortment of advocates on many fronts: cultural, social, political, and racial. Commencing around the end of World War I and continuing well into the Great Depression, the Harlem Renaissance trained a virtual spotlight on African American artists, highlighting their contributions to the literary, performing, and visual arts, with a special emphasis on their almost libidinal powers during the jazz age. In contrast, the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and 1970s, with its comparable examples of an insurgent black creativity, has only recently become recognized – in the last twenty-five years or so – as another, very important moment in African American arts and letters. Born out of the ashes of the Civil Rights Movement and the alternative battle cries of “Black Power” and “Black is Beautiful,” the Black Arts Movement privileged a politically inspired aesthetic of figural expressionism and racial romanticism, as played out in spoken poetry, ritual theater, and hyper-visuality. In tandem with a new appreciation for the Black Arts Movement, cultural historians over the past decade have used the notion of a chronologically defined, black artistic “renaissance” to critically revisit the 1960s/70s and the 1920s/30s, perhaps seeing in both moments occasions for a radical rethinking of race and the role of the artist in re-conceptualizing society. Apart from a common emphasis on producing art that reflected “race pride,” or that exemplified a kind of conspicuous blackness, the Harlem Renaissance and the Black Arts Movement were both cultural projects in which cross-generational debates around the black artist’s responsibilities to the black masses abounded, often initiated by youthful black provocateurs who lambasted their opposers without formal restraints or political inhibitions. 1

11 Since 2005, several important books and anthologies have reassessed these two movements, questioning, for example, the efficacy of the Harlem Renaissance’s call to racial distinctiveness in the arts ( Calo , 2007), and critiquing the assumptions of racial exclusivity in the reception and understanding of art during the Black Arts Movement ( Collins, Crawford, 2006; Hassan, Crawford, 2011, 2012 ). The Harlem Renaissance has especially inspired art historians of late, fostering previously uncharted research into that era’s expansive, art-informed print culture ( Goeser , 2007), the underappreciated role of women artists ( Kirschke , 2014), Chicago, Illinois as an important, but frequently unmapped New Negro territory ( They Seek a City , 2013), and other thematic directions ( Tribe , 2007; Thompson K. , 2007). Recently, some of the most important Harlem Renaissance artists have been the subjects of major art exhibitions, such as Aaron Douglas ( Aaron Douglas , 2007), Hale Woodruff ( Amaki, Barnwell Brownlee , 2007; Rising Up , 2012), Nancy Elizabeth Prophet ( Amaki, Barnwell Brownlee , 2007), and Archibald J. Motley, Jr. ( Archibald Motley , 2014), while the life and work of sculptor Richmond Barthé were the focal points of two very important biographies ( Vendryes, 2008; Lewis, 2009 ). Journal articles have also offered alternative readings of the Harlem Renaissance, introducing into the topic the era's overtures toward the esoteric and spiritual in art ( Vincenti , 2006) and artistic explorations of stereotype and satire ( Ott, 2008; Wolfskill, 2009 ).

12 Given the contemporary visual appeal of classic works by such Black Arts Movement figures as Barkley L. Hendricks, Joe Overstreet, Faith Ringgold, Betye Saar, and Charles White, much of the recent scholarship surrounding this period can be found in exhibition publications. From a scholarly repositioning of some of the Movement’s most significant activities to Los Angeles, ( ‘Now Dig This!’ , 2013), to a philosophical volleying between the Movement’s activist orientations ( Witness , 2014) and its psychological performances of race ( Back to Black , 2005), the Black Arts Movement has prompted many historians and curators to go beyond the period’s agitprop façades and political rhetoric ( Black Panther , 2007) and, instead, to delve deeply into its philosophy of community ( Zorach , 2011) and its revamped aesthetic of the black quotidian ( Fine , 2005). Despite the focus on individual careers, many monographic studies on Black Arts Movement artists have considered their subjects within more theoretical frameworks, taking into account the broader question of artistic genre ( Barkley L. Hendricks , 2008; Dawoud Bey … , 2012) and divergent, alternative modernisms ( American People … , 2011; Fine, Francis , 2011; Romare Bearden , 2011).

Feminine-masculine-feminine

13 Feminist perspectives within recent studies of African American art and visual culture have traversed the rather obvious identity politics of gender recognition and the attendant critiques of historic, male-dominated institutions and social practices. Instead, some of the most interesting scholarship of late has been informed by a subset of cultural theorists and social scientists who foreground the situational realities of gender, race, sexuality, and class, and the need for rigorous, fully engaged examinations which address questions of fundamental rights, individual agency, engendering practices, and the full, conceptual arc of recognition/misrecognition ( Brand , 2006).

14 As suggested in this section’s subheading feminine-masculine-feminine, the sandwiched nature of an ontological maleness between concepts of the feminine, womanhood, and the entire gendered/sexual scale of lived experiences has shaped much of the scholarship, especially writings that definitively insert issues of racial and cultural blackness into art history ( Golden , 2012). Indeed, a good number of these investigations aim at the shifting perceptions of the black female subject in art ( Brown , 2012), from pictorial meditations on beauty and corporeality ( Willis , 2009) to case studies of real-life black women as paragons of elegance and style ( Williams , 2007) and investigations of cultural stereotypes ( Thompson C. , 2013).

15 Arguably, though, the never-ending need for original scholarship on forgotten or under-examined black women artists has persisted well into the present, and several art historians have addressed this historical void, utilizing the comprehensive overview ( Farrington , 2005a) as well as the monograph to examine such canonical figures as the nineteenth-century sculptor Mary Edmonia Lewis ( Woods, 2009; Buick, 2010 ) and the twentieth-century painter Lois Mailou Jones ( Lois Mailou Jones … , 2009), the latter being one of the very few artists who participated in both the Harlem Renaissance and the Black Arts Movement. Contemporary black women artists have also inspired art historians and curators to bridge their work with feminist thought, identity politics, and unresolved questions of gender, sexuality and social difference. Again, recent monographic studies on artists such as Carrie Mae Weems ( Carrie Mae Weems , 2012), Mickalene Thomas ( Mickalene Thomas , 2012) and especially Lorna Simpson ( Enwezor, 2006; Lamm, 2011; Belisle, 2011 ) have all relied on modern and contemporary feminist theories for their impetus as much as on the artists’ careers and works themselves. Clearly, the gulf between examining the creative output of black women artists and investigating black female imagery in the visual arts is negligible when considering performance art or, rather, the black female body as an artistic vehicle, and several authors have taken up this topic with thought-provoking and compelling findings ( Smith, 2011; Bowles, 2011 ). An exhibition catalogue that took as its premise the uncharted occurrence of black women filmmakers and videographers since 1970 ( Barnwell, Oliver , 2008) added appreciably to these recent histories of African American art and visual culture, also augmenting the few extant studies of women across the racial spectrum working in media arts.

Post-black (noirceur chimérique ou l’art noir sans négritude)

16 The 2001 minting of the term “post-black” by Studio Museum in Harlem director Thelma Golden and visual artist Glenn Ligon was not only perspicacious to a shift in the cultural mindsets of the latest generation of African American artists, but it was prescient for what was on the artistic horizon: a parallel (or “shadow”) racial preoccupation among African American artists that unapologetically embraced the contradiction of making black art without bringing into play a platitudinous, archetypal blackness. Before the decade ended, scholars had given the post-black concept full-court scrutiny ( Keith, 2005; English, 2007; Murray, 2007; Schur, 2007; Taylor, 2007 ), and this interrogation and critical exegesis of the concept have continued unabated ( Gonzalez, 2011; Fleetwood, 2011; Walker H., 2013; Maus, Donahue, 2014 ).

17 Even when the term “post-black” wasn’t prominently positioned in a publication’s title or text, its presence has hovered over certain scholarly enterprises in recent African American art histories and visual studies, whether the topic was conceptualism ( D ouble-Consciousness , 2005), heterodox belief systems ( NeoHoodoo , 2008); the enduring memory of the Civil Rights Movement ( After 1968 , 2008); African diasporic aesthetics ( Thompson K. , 2015), or contemporary art in general ( Black Light/White Noise , 2007; 30 Americans , 2008; Backer, 2013 ). And this same, shadowy blackness – which, again, Golden and Ligon first referenced in the context of a 2001 survey of works by African American artists at the Studio Museum in Harlem ( Freestyle , 2001) – would continue to loom in subsequent iterations of the contemporary African American group show ( Frequency , 2005; Flow , 2008; Fore , 2013); ironically, an exhibition format that was paradigmatic of the prosaically race-based Black Arts Movement exhibitions in the 1960s and 1970s.

18 Also characteristic of the post-black phenomenon was, paradoxically, a greater visibility in major art galleries and museums for black artists and for works that expressed a decidedly ambiguous racial and cultural drift. Although not considered the principal proponents of a post-black philosophy, important African American artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat, Martin Puryear, Kerry James Marshall, and Wangechi Mutu all exuded enough complexity and opacity in their work to garner critical notice and visual currency in a post-black art world, resulting in a steady stream of exhibition publications and monographic studies ( Mayer, 2005; Martin Puryear , 2007; Jean-Michel Basquiat , 2010; Wangechi Mutu , 2013 ). But the artistic purveyors of a post-black aesthetic have been some of the most conspicuous art world figures and subjects for art criticism, as seen in Hank Willis-Thomas’s digital odes to visual appropriation ( Guzman , 2008), Glenn Ligon’s text-based paintings and sculptures ( Glenn Ligon , 2011; DeLand, 2012 ), Rashid Johnson’s racially deconstructive assemblages ( Morton, 2012; Rashid Johnson , 2012 ), and, last but not least, Kara Walker’s silhouetted satires and frank moral defamations ( Kara Walker , 2007; Berry, 2007; Walker K., 2007; Wall, 2010; Als, 2013 ).

Insider outsiders

19 Sociologist Gary Alan Fine’s 2004 study of the position and perception of artists operating on the fringes of the modern and contemporary art world had major consequences for subsequent African American art scholarship ( Fine , 2004). The typical profile of Fine’s subjects – African American, non-academically trained, and socio-economically vulnerable – represented a vital yet frequently ignored subset among African American artists: an artistic contingent that, following the critically acclaimed Corcoran Gallery of Art’s exhibition Black Folk Art in America, 1930 – 1980 ( Black Folk Art … , 1982), forever challenged the art world’s presumptive notions of authenticity, insularity, hierarchy, and difference. Indeed, Fine’s emphases on the social and economic forces that essentially created this artistic cohort shifted the discussion away from the stylistic vagaries of visual crudity and the individual eccentricities of these artists and, instead, prompted a close and critical scrutiny of the art world trends, market forces, and mythologizing around these “insider outsiders.”

20 Variously described as “folk,” “self-taught,” or “outsider,” these accidental artists and their champions troubled an already fractious art world. Because of their separate yet vaunted status, they provided additional fodder for viewing the greater art scene as often racist and exploitative, especially in light of more established and, yet, overlooked African American artists and their documented struggles for greater recognition. Social scientists and art historians have looked closely at this cultural phenomenon, and have not resisted casting a critical eye on the politics of institutionally embracing these artists ( Rothenberg, Fine, 2008; Cooks, 2014 ). Despite the formation of a “black folk art” canon decades earlier, several recent historical summaries ( Crown, Russell, 2007; Russell, 2011 ) and survey exhibitions ( ‘Great and Mighty Things’… , 2013 ; When the Stars… , 2014 ) have further institutionalized this subgenre, aligning much of this art with spiritual aims and/or regional interests. Artists who live and work in the southern United States and many within a small-town or rural context have often been studied from the perspective of such vernacular art forms as quilting ( Arnett , 2006a) or, with an eye directed more toward an urban visual lexicon like yard decorations ( Gundaker, McWillie, 2005) and street performances ( Becker, 2013).

21 As with the other research-generating areas of African American art history, recent case studies of individual self-taught or outsider artists have both strengthened the primary source materials on these artists, and used the monographic format as a vehicle for thinking about the theoretical issues that impact the outsider art category ( Arnett, 2006 b ; The Treasure of Ulysses Davis , 2008). Artist Bill Traylor, an ex-slave working in Depression-era Alabama, inspired several scholars to grapple with the idea of an African diasporic racial memory in art ( Bill Traylor , 2005, 2012; Sobel, 2009 ), while both Clementine Hunter and Horace Pippin, two celebrated mid twentieth-century folk artists, encouraged art historians and curators to reconcile these artists' social isolation and provincialism with their well-connected gallery representation and market notoriety ( Whitehead, Shiver, 2012; Horace Pippin , 2015 ).

Revised histories

22 The enduring value in African American art scholarship of conducting original research and reexamining important historical figures and subject matter cannot be overstated. Twenty-first-century scholars of African American art have wholeheartedly embraced historical revisionism in multiple ways, from reimagining earlier versions of the art-historical survey ( Bernier , 2009), to reworking the standard narratives surrounding the art and artists of the African Diaspora, both well-known and relatively obscure ( Afro-Modern , 2010). In using the term “historical revisionism” in this particular context, what is not being suggested are recalibrations that invent false accounts or ignore historical truths. Rather, what has transpired in the literature is a critical enterprise that, by asking different questions and conducting new research into uncharted art-historical waters, amends the record with a fresh and, yet, an anarchistic perspective.

23 The most comprehensive of these art-historical reconsiderations was the African American artists-themed volumes The Image of the Black in Western Art ( Bindman, Gates , 2014), which conceived modern and contemporary black artistic production in a part-chronological, part-international, and wholly original fashion. In a somewhat different manner, a number of American art museums have organized major African American art exhibitions with accompanying catalogues that, exclusively focusing on their own, occasionally encyclopedic collections, utilized the survey exhibition formula for somewhat different purposes ( Golden, 2010; African American Art , 2012; Mercer V.J., 2012 ; Represent , 2014; Common Wealth , 2015 ).

24 Original scholarship has continued to take place around individual artists and their artistic production, but often integrating novel ways of interpreting these artists’ works and careers. One observes this radical rethinking of African American artists and their art in studies chronologically located in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, where the memories of enslavement, the specters of racial prejudice, and the movements toward African American social activism undergirded many art-historical studies ( Shaw, 2005; Charles Ethan Porter , 2008; Ketner, 2011; Henry Ossawa Tanner , 2012 ). From relatively under-appreciated but historically significant artists such as sculptor Meta Warrick Fuller and painters William Edouard Scott and Norman Lewis ( Ater, 2011; Pinder, 2011, From the Margins , 2014 ), to canonical American art figures like Jacob Lawrence ( Hills, 2009; Jacob Lawrence , 2015 ) recent art histories have revisited the standard African American art narrative in light of alternative readings of American nationalism, mid-twentieth-century gestures and aspirations toward universality, and a corresponding race- and class-informed modernism.

25 Since 2005 theme-based research has continued to capture the attention of many historians of African American art ( Francis , 2012), enabling scholars to focus more intently on unresolved issues in the literature, such as race and abstraction ( Energy/Experimentation , 2006), philanthropy for black artists ( A Force for Change , 2009), African Americans and art museums ( Cooks , 2011), and art, race and trauma ( Tribe , 2013). Several anthologies ( Farrington, 2005 b ; Jones, 2011 ) and exhibition catalogues ( Portraits of a People , 2006; Cooksey, 2013) brought greater attention to the notion that African American art scholarship could be deeply topical, and particular enough to engage with comparable and similarly focused research in the visual arts and the humanities. Cultural historian and theoretician Kobena Mercer successfully integrated and assembled many of these thematically focused studies of African American art into the four-volume series, Cross Cultural Perspectives in the Visual Arts, framing this scholarship within the larger contexts of cosmopolitanism, abstraction, the vernacular, and expatriation ( Mercer, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008 ).

26 This fairly recent theoretical turn in African American art history – conterminous with many humanities subfields and their shift toward more critical and ideational approaches to history – has manifested itself in many ways over the past decade. For example, the often pedantic and moralistic lens through which the history of slavery has been viewed was deconstructed through a part-thematic, part-theoretical perspective ( Copeland , 2013), and a similar multi-pronged tack was undertaken on the subject of black portraiture ( Powell , 2008). Likewise, certain basic themes in African American art, such as the African diaspora and the idea of a distinctive black aesthetic, have been significantly reconceived, both through the conceptual mechanisms of the dialogic ( Mercer, 2012 ) and the synaesthetic ( Thompson K. , 2009), and by means of the relatively traditional, yeoman-like processes of historiography and critical interpretation ( Thompson K. , 2011).

- 2 For an in depth examination of the historiographic breadth of African American art research, includ (...)

- 3 Kobena Mercer, “New Practices, New Identities: Hybridity and Globalization” ( Bindman, Gates , 2014, (...)

27 In closing, one might assume that the assorted texts discussed here and the new directions in African American art-historical research are indebted to all of the scholarly undertakings and intellectual “dream work” that preceded them. Today's art historians and cultural critics could not have even imagined pursuing the study and analysis of something called “black” or African American art without the intellectual substratum that had already been surveyed and leveled by the following: William Dawson, Freeman Henry Morris Murray, Benjamin Brawley, Alain Locke, Zora Neale Husrton, Meville Herskovits, James V. Herring, James A. Porter, Dorothy Porter Wesley, Cedric Dover, Sidney Kaplan, David C. Driskell, Robert Farris Thompson, Regenia Perry, Elsa Honig Fine, Marcia M. Mathews, Deirdre Bibby, Ed Spriggs, Harry Henderson, Romare Bearden, Samella Lewis, Edmund B. Gaither, Jeff Donaldson, Floyd Coleman, Murry DePillars, Rosalind Jeffries, Maude Wahlman, Mary Schmidt Campbell, Steven Jones, Lucy Lippard, John Michael Vlach, Henry Drewal, Monni Adams, Lynn Igoe, Leslie King-Hammond, Lowery Stokes Sims, Patricia Hills, Sharon F. Patton, Guy McElroy, Lizzetta LeFalle Collins, Judith Wilson, Greg Tate, Ann Gibson, James Smalls, Marilyn Richardson, Albert Boime, Jospeh Ketner, David Lubin, Juanita M. Holland, Beryl Wright, Michael D. Harris, Deborah Willis, and Maurice Berger, among countless others. 2 Prior to the twenty-first century these forerunners in African American art scholarship engaged in intellectual pursuits that, through many decades of archival research, bibliographic groundwork, personal interviews, cultural retrievals, artistic rediscoveries, and thoughtful, desk-bound writing, culminated in what theoretician Kobena Mercer has described as a “multi-vocal dialogue on matters of cultural difference, in which the identities of all participants were open to new possibilities.” 3

28 Scholars working in the early twenty-first century have witnessed a period of creative exchange and intellectual re-engagement with the discipline, in which not only longtime scholars of African American art and culture have participated, but also art historians and theorists from across the geopolitical, ideological, and racial/cultural spectrum. As seen in this state-of-the-field reflection, recent scholarship in African American art touches on a multiplicity of issues, including such previously unexplored or barely addressed topics as the vernacular arts, performance art, mass media, embodiment, corporeality, historicity, spirituality, racial indifference, visual queering, satire, migration, nativism, multi-linguistics, global violence, urbanism, and homelessness, to name just a few.

29 Clearly, an intellectual project such as the study of African American art is, by design and necessity, one that privileges an African diasporic or black perspective. However, the scholarly outpourings of the last decade have made it apparent that the centrality of a black perspective does not mean blackness can be successfully reduced to an inviolable racial category, or a succinct definition. Many of the writings discussed in this essay argue that, in spite of an assumed singularity, blackness and the African diaspora are, in fact, hybrid entities, multilayered in their discursive acts, historically transnational in scope and, yet, reliably unstable and transitory.

30 Although much of this writing opens up art history to a twenty-first-century world of radically different ideas, new artists, and critical, cutting-edge methodologies, probably all of the authors under review perceive the previous century as a key moment for creating unprecedented black images and for reimagining how art history might be more thoroughly documented and democratically narrated. The twentieth century’s chronicled instances of: disenfranchisement and the eventual re-enfranchisement of black peoples; political and cultural imperialism perpetrated on black communities; questions of alliances from both within “the race” and beyond; mass migrations of African peoples to Western metropolises; the flowerings of assorted black cultural “renaissances”; and the ad infinitum debates over racial discrimination; are all proof of that century’s importance to the development of black narratives, whether art-historical or quotidian, retrospective or contemporaneous. If, in 1916, African American art historian Freeman Henry Morris Murray had had a crystal ball, magically enabling him to observe how the study of art by and about peoples of African descent had evolved from his solitary vantage point to, say, one hundred years in the future, not only would he have marveled at the many social and cultural changes that had transpired, but he would have been amazed by a discipline and subfield that, unlike in his more apathetic time, acknowledged the historical importance of black artists, as well as the intrinsic value of studying works that placed questions of race and culture at their very core.

Bibliographie

– 30 Americans , 2008: 30 Americans , (exh. cat., Miami, Rubell Family Collection, 2008), Miami, 2008.

– Aaron Douglas , 2007: Aaron Douglas: African American Modernist, Susan Earle ed., (exh. cat., Lawrence, Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas, 2007), Lawrence, 2007.

– African American Art , 2012: African American Art: Harlem Renaissance, Civil Rights Era and Beyond , Richard J. Powell, Virginia Meckenburg, (exh. cat., Washington, D.C., Smithsonian American Art Museum, 2012), Washington, D,C., 2012.

– Afro-Modern , 2010: Afro-Modern: Journeys through the Black Atlantic , Tanya Barson, Peter Gorschluter eds., (exh. cat., Liverpool, Tate Liverpool, 2010), Liverpool, 2010.

– After 1968 , 2008: After 1968: Contemporary Artists and the Civil Rights Legacy , Jeffrey D. Grove, (exh. cat., Atlanta, High Museum of Art, 2008), Atlanta, 2008.

– Als , 2013: Hilton Als et al., Kara Walker: Dust Jackets for the Niggerati , New York, 2013.

– Amaki , Barnwell Brownlee , 2007: Amalia Amaki, Andrea Barnwell Brownlee, Hale Woodruff, Nancy Elizabeth Prophet, and the Academy , Seattle, 2007.

– American People… , 2011: American People, Black Light: Faith Ringgold’s Paintings of the 1960s , Michele Wallace, (exh. cat., Purchase, Neuberger Museum of Art, 2011), Purchase, 2011.

– Archibald Motley , 2014: Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist , Richard J. Powell ed., (exh. cat., Durham, Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, 2014), Durham, 2014.

– Arnett , 2006a: Paul Arnett ed., Gee’s Bend: The Architecture of the Quilt , Atlanta, 2006.

– Arnett , 2006b: Paul Arnett ed., Thornton Dial in the 21st Century , Atlanta, 2006.

– Ater , 2011: Renee Ater, Remaking Race and History: The Sculpture of Meta Warrick Fuller , Berkeley, 2011.

– Back to Black , 2005: Back to Black: Art, Cinema & the Racial Imaginary , Richard J. Powell ed., (London, Whitechapel Art Gallery, 2005), London, 2005.

– Backer , 2013: Yona Backer, Radical Presence: Black Performance in Contemporary Art , Houston, 2013.

– Barkley L. Hendricks , 2008: Barkley L. Hendricks: Birth of the Cool , Trevor Schoonmaker ed., (exh. cat., Durham, Duke University, Nasher Museum of Art, 2008), Durham, 2008.

– Barnwell , Oliver , 2008: Andrea Barnwell, Valerie Cassel Oliver, Cinema Remixed and Reloaded: Black Women Artists and the Moving Image since 1970 , Seattle, 2008.

– Becker , 2013: Cynthia Becker, “New Orleans Mardi Gras Indians: Mediating Racial Politics from the Backstreets to Main Street,” in African Arts , 46/2, 2013, p. 36-49.

– Belisle , 2011: Brooke Belisle, “Felt Surface, Visible Image: Lorna Simpson’s Photography and the Embodiment of Appearance,” in Photography and Culture , 4/2, 2011, p. 157-178.

– Bernier , 2009: Celeste-Marie Bernier, African American Art and Visual Culture: From Slavery to the Present , Chapel Hill, 2009.

– Berry , 2007: Ian Berry et al., Kara Walker: Narratives of a Negress , New York, 2007.

– Bill Traylor , 2005: Bill Traylor, William Edmondson and the Modernist Impulse , Josef Helfenstein, (exh. cat., Urbana, University of Illinois, Krannert Art Museum, 2005), Urbana, 2005.

– Bill Traylor , 2012: Bill Traylor: Drawings from the Collections of the High Museum of Art and the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts , Susan Crawley, (exh. cat., Atlanta, High Museum of Art, 2012), Atlanta, 2012.

– Bindman , Gates , 2014: David Bindman, Henry Louis Gates Jr. eds., The Image of the Black in Western Art , V, 2, The Twentieth Century: The Rise of Black Artists , Cambridge, 2014.

– Black Folk Art …, 1982: Black Folk Art in America, 1930-1980 , Jane Livingston, John Beardsley, (exh. cat., Washington, D.C., Corcoran Gallery of Art, 1982), Washington, D.C., 1982.

– Black Light/White Noise , 2007: Black Light/White Noise: Sound and Light in Contemporary Art , Marti Mayo et al., (exh. cat., Houston, Contemporary Art Museum, 2007), Houston, 2007.

– Black Panther , 2007: Black Panther: The Revolutionary Art of Emory Douglas , Sam Durant ed., (exh. cat., Los Angeles, Museum of Contemporary Art, 2007), Los Angeles, 2007.

– Bowles , 2011: John P. Bowles, Adrian Piper: Race, Gender, Embodiment , Durham, 2011.

– Brand , 2006: Peg Brand, “Feminist Art Epistemologies: Understanding Feminist Art,” in Hypatia , 21/3, 2006, p. 166-189.

– Brawley , 1918: Benjamin G. Brawley, The Negro in literature and art in the United States , New York, 1918.

– Brown , 2012: Caroline A. Brown, The Black Female Body in American Literature and Art: Performing Identity , New York, 2012.

– Buick , 2010: Kirsten Pai Buick, Child of Fire: Mary Edmonia Lewis and the Problem of Art History’s Black and Indian Subject , Durham, 2010.

– Calo , 2007: Mary Ann Calo, Distinction and Denial: Race, Nation and the Critical Construction of the African American Artist, 1920-1940 , Ann Arbor, 2007.

– Carrie Mae Weems , 2012: Carrie Mae Weems: Three Decades of Photography and Video , Kathryn E. Delmez ed., (exh. cat., New York, Guggenheim Museum, 2012), New York, 2012.

– Charles Ethan Porter , 2008: Charles Ethan Porter: African American Master of Still Life , Hildegard Cummings, (exh. cat., New Britain, New Britain Museum of Art, 2008), New Britain, 2008.

– Collins , Crawford , 2006: Lisa Gail Collins, Margo Natalie Crawford eds., New Thoughts on the Black Arts Movement , New Brunswick, 2006.

– Common Wealth , 2015: Common Wealth: Art by African Americans in the Museum of Fine Arts , Lowery Stokes Sims ed., (exh. cat., Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2015), Boston, 2015.

– Cooks , 2011: Bridget Cooks, Exhibiting Blackness: African Americans and the American Art Museum , Amherst, 2011.

– Cooks , 2014: Bridget Cooks, “The Gee’s Bend Effect,” in Textile: The Journal of Cloth & Culture , 12, 2014, p. 346-363.

– Cooksey , 2013: Susan Cooksey, Kongo Across the Waters , Gainesville, 2013.

– Copeland , 2013: Huey Copeland, Bound to Appear Art, Slavery, and the Site of Blackness in Multicultural America , Chicago, 2013.

– Crown , Russell , 2007: Carol Crown, Charles Russell, Sacred and Profane: Voice and Vision in Southern Self-taught Art , Jackson, 2007.

– Dawoud Bey… , 2012: Dawoud Bey Harlem USA, Matthew S. Witkovsky ed., (exh. cat., Chicago, Art Institute of Chicago, 2012), Chicago, 2012.

– DeLand , 2012: Lauren DeLand, “Black Skin, Black Masks: The Citational Self in the Work of Glenn Ligon,” in Criticism , 54/4, 2012, p. 507-537.

– Double-Consciousness , 2005: Double-Consciousness: Black Conceptual Art Since 1970 , Valerie Cassel Oliver, (exh. cat., Houston, Contemporary Art Museum, 2005), Houston, 2005.

– Energy/Experimentation , 2006: Energy/Experimentation: Black Artists and Abstraction, 1964-1980 , Kellie Jones, (exh. cat., New York, Studio Museum in Harlem, 2006), New York, 2006.

– English , 2007: Darby English, How to See a Work of Art in Total Darkness , Cambridge, 2007.

– Enwezor , 2006: Okwui Enwezor, Lorna Simpson , New York, 2006.

– Farrington , 2005a: Lisa Farrington, Creating in Their Own Image: The History of African American Women Artists , New York, 2005.

– Farrington , 2005b: Lisa Farrington ed., Source: Notes in the History of Art , special issue “African-American Art,” 24, 2005.

– Fine , 2004: Gary Alan Fine, Everyday Genius: Self-Taught Art and the Culture of Authenticity , Chicago, 2004.

– Fine , 2005: Ruth Fine, “Expanding the Mainstream: Romare Bearden Revisited,” in Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society , 149/1, 2005, p. 40-55.

– Fine , Francis , 2011: Ruth Fine, Jacqueline Francis eds., Romare Bearden , American Modernist , ( Studies in the History of Art Series , 71), Washington, D.C., 2011.

– Fleetwood , 2011: Nicole Fleetwood, Troubling Vision: Performance, Visuality and Blackness , Chicago, 2011.

– Flow , 2008: Flow , Thelma Golden ed., (exh. cat., New York, Studio Museum in Harlem, 2008), New York, 2008.

– A Force for Change , 2009: A Force for Change: African American Art and the Julius Rosenwald Fund , Daniel Schulman, (Chicago, Spertus Institute for Jewish Learning and Leadership, 2009), Chicago, 2009.

– Fore , 2013: Fore , Thelma Golden ed., (exh. cat., New York, Studio Museum in Harlem, 2013), New York, 2013.

– Francis , 2012: Jacqueline Francis, Making Race: Modernism and Racial Art in America , Seattle, 2012.

– Freestyle , 2001: Freestyle , Thelma Golden ed., (exh. cat., New York, Studio Museum in Harlem, 2001), New York, 2001.

– Frequency , 2005: Frequency , Thelma Golden ed., (exh. cat., New York, Studio Museum in Harlem, 2005), New York, 2005.

– From the Margins , 2014: From the Margins: Lee Krasner/Norman Lewis, 1945-1952 , Norman L. Kleeblatt, (exh. cat., New York, Jewish Museum, 2014), New York, 2014.

– Glenn Ligon , 2011: Glenn Ligon: AMERICA , Scott Rothkopf, (exh. cat., New York, Whitney Museum of American Art, 2011), New York, 2011.

– Goeser , 2007: Caroline Goeser, Picturing the New Negro: Harlem Renaissance Print Culture and Modern Black Identity , Lawrence, 2007.

– Golden , 2010: Thelma Golden ed., Re: Collection; Selected Works from The Studio Museum in Harlem , New York, 2010.

– Golden , 2012: Thelma Golden ed., Kehinde Wiley , New York, 2012.

– Gonzalez , 2011: Jennifer A. Gonzalez, Subject to Display: Reframing Race in Contemporary Installation Art , Cambridge, 2011.

– ‘Great and Mighty Things’… , 2013: ‘Great and Mighty Things’: Outsider Art from the Jill and Sheldon Bonovitz Collection , Ann Percy ed., (exh. cat., Philadelphie, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2013), Philadelphie, 2013.

– Gundaker , McWillie , 2005: Grey Gundaker, Judith McWillie, No Space Hidden: The Spirit of African American Yard Work , Knoxville, 2005.

– Guzman , 2008: Rene de Guzman, Hank Willis-Thomas: Pitch Blackness , New York, 2008.

– Hassan , Crawford , 2011: Salah Hassan, Margo Crawford eds., theme issue “ Remembering the Black Arts Movement,” Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art , 29, 2011.

– Hassan , Crawford , 2012: Salah Hassan, Margo Crawford eds., theme issue “The Black Arts Movement: Testimonials/Documents/Conversations,” Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art , 30, 2012.

– Henry Ossawa Tanner , 2012: Henry Ossawa Tanner: Modern Spirit , Anna O. Marley ed., (exh. cat., Philadelphie, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 2012), Philadelphie, 2012.

– Hills , 2009: Patricia Hills, Painting Harlem Modern , The Art of Jacob Lawrence , Berkeley, 2009.

– Horace Pippin , 2015: Horace Pippin: The Way I See It , Audrey Lewis et al., (exh. cat., Chadds Ford, Brandywine River Museum of Art, 2015), Chadds Ford, 2015.

– Jacob Lawrence , 2015: Jacob Lawrence: The Migration Series , Leah Dickerman, Elsa Smithgall eds., (exh. cat., New York, Museum of Modern Art, 2015), New York, 2015.

– Jean-Michel Basquiat , 2010: Jean-Michel Basquiat , Dieter Buchhart ed., (exh. cat., Paris, Musée d’art moderne, 2010), Paris, 2010.

– Jones , 2011: Kellie Jones, Eye-Minded , Durham, 2011.

– Kara Walker , 2007: Kara Walker: My Complement, My Enemy, My Oppressor, My Love , Philippe Vergne ed., (exh. cat., Minneapolis, Walker Art Center, 2007), Minneapolis, 2007.

– Keith , 2005: Tricia Keith, “Strategy or Spectacle? Postmodernism, African-American Artists and Art scholarship,” in Third Text , 19, 2005, p. 617-623.

– Ketner , 2011: Joseph D. Ketner, “Struggles many and great: James P. Ball, Robert Duncanson, and other artists of color in antebellum Cincinnati,” in Magazine Antiques , 178, 2011, p. 108-115.

– Kirschke , 2014: Amy Helene Kirschke ed., Women Artists of the Harlem Renaissance , Jackson, 2014.

– Lamm , 2011: Kimberly Lamm, “Seeing Sex and Racism in Lorna Simpson’s You’re Fine ,” in n.paradoxa: International Feminist Art Journal , 28, 2011, p. 88-93.

– Lewis , 2009: Samella Lewis, Barthé: His Life in Art , Los Angeles, 2009.

– Lois Mailou Jones… , 2009: Lois Mailou Jones: A Life in Vibrant Colors , Carla M. Hanzal ed., (exh. cat., Charlotte, Mint Museum of Art, 2009), Charlotte, 2009.

– Martin Puryear , 2007: Martin Puryear , John Elderfield ed., (exh. cat., New York, Museum of Modern Art, 2007), New York, 2007.

– Maus , Donahue , 2014: Derek C. Maus, James J. Donahue eds., Post-Soul Satire: Black Identity After Civil Rights , Jackson, 2014.

– Mayer , 2005: Marc Mayer ed., Basquiat , New York, 2005.

– Mercer , 2005: Kobena Mercer ed., Cosmopolitan Modernisms , Cambridge, 2005.

– Mercer , 2006: Kobena Mercer ed., Discrepant Abstraction , Cambridge, 2006.

– Mercer , 2007: Kobena Mercer ed., Pop Art and Vernacular Cultures , Cambridge, 2007.

– Mercer , 2008: Kobena Mercer ed., Exiles , Diasporas & Strangers , Cambridge, 2008.

– Mercer , 2012: Kobena Mercer, “Art History and the Dialogics of Diaspora,” in Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism , 16/2, 2012, p. 213-227.

– Mercer V.J., 2012: Valerie J. Mercer, “Introduction,” in Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts , theme issue “African American Art,” 86, 1/4, 2012, p. 1-123.

– Mickalene Thomas , 2012: Mickalene Thomas: Origin of the Universe , Lisa Melandri ed., (exh. cat., Santa Monica, Santa Monica Museum of Art, 2012), Santa Monica, 2012.

– Morton , 2012: Tom Morton, “Infinite Blackness,” in Parkett , 90, 2012, p. 122-128.

– Murray , 2007: Derek Conrad Murray, “Post Post-Black: Some Politically Incorrect Thoughts on the Reception and Contemplation of African American Art,” in Art Journal , 66/4, 2007, p. 112-114.

– Murray , 1916: Freeman Henry Morris Murray, Emancipation and the Freed in American Sculpture , Washington, D.C., 1916.

– NeoHoodoo , 2008: NeoHoodoo: Art for a Forgotten Faith , Franklin Sirmans ed., (exh. cat., Houston, Menil Collection, 2008), Houston, 2008.

– ‘Now Dig This!’ , 2013: ‘Now Dig This!’: Art and Black Los Angeles, 1960-1980 , Kellie Jones, (exh. cat., Los Angeles, University of California, Hammer Museum, 2013), Los Angeles, 2013.

– Ott , 2008: John Ott, “Labored Stereotypes: Palmer Hayden’s The Janitor Who Paints ,” in American Art , 22/1, 2008, p. 102-115.

– Patton , 1998: Sharon F. Patton, African American Art , New York, 1998.

– Pinder , 2011: Kymberly N. Pinder, “Painting the Gospel Blues,” in American Art , 25/3, 2011, p. 76-99.

– Portraits of a People , 2006: Portraits of a People: Picturing African Americans in the 19 th Century , Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, (exh. cat., Andover, Addison Gallery of American Art, 2006), Andover, 2006.

– Powell , 2002: Richard J. Powell, Black Art: A Cultural History , London, 2002.

– Powell , 2008: Richard J. Powell, Cutting a Figure: Fashioning Black Portraiture , Chicago, 2008.

– Rashid Johnson , 2012: Rashid Johnson: Message to Our Folks , Julie Rodrigues Widholm, (exh. cat., Chicago, Museum of Contemporary Art, 2012), Chicago, 2012.

– Represent , 2014: Represent: 200 years of African American Art in the Philadelphia Museum of Art , Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw ed., (exh. cat., Philadelphie, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2014), Philadelphie, 2014.

– Rising Up , 2012: Rising Up: Hale Woodruff’s Murals at Talladega College , Stephanie Heydt ed., (exh. cat., Atlanta, High Museum of Art, 2012), Atlanta, 2012.

– Romare Bearden , 2011: Romare Bearden: American Modernist , Ruth Fine, Jacqueline Francis eds., (exh. cat., Washington, D.C., National Gallery of Art, 2011), Washington, D.C., 2011.

– Rothenberg , Fine , 2008: Julia Rothenberg, Gary Alan Fine, “Art Worlds and their ethnographers,” in Éthnologie française , 38, 2008, p. 31-37.

– Russell , 2011: Charles Russell, Groundwaters: A Century of Art by Self-Taught And Outsider Artists , New York, 2011.

– Schur , 2007: Richard Schur, “Post-Soul Aesthetics in Contemporary African American Art,” in African American Review , 41/4, 2007, p. 641-654.

– Shaw , 2005: Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, “Moses Williams, Cutter of Profiles”: Silhouettes and African American Identity in the Early Republic,” in Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society , 149/1, 2005, p. 22-39.

– Smith , 2011: Cherise Smith, Enacting Others: Politics of Identity in Eleanor Antin, Nikki S. Lee, Adrian Piper, and Anna Deavere Smith , Durham, 2011.

– Sobel , 2009: Mechal Sobel, Painting a Hidden Life: The Art of Bill Traylor , Baton Rouge, 2009.

– Taylor , 2007: Paul C. Taylor, “Post-Black, Old Black » in African American Review , 41/4, 2007, p. 625-640.

– They Seek a City , 2013: They Seek a City: Chicago and the Art of the Great Migration , 1910-1950 , Sarah Kelly Oehler, (exh. cat., Chicago, Art Institute of Chicago, 2013), Chicago, 2013.

– Thompson C. , 2013: Cheryl Thompson, “Contesting the Aunt Jemima Trademark through Feminist Art: Why is She Still Smiling?,” in n.paradoxa: International Feminist Art Journal , 31, 2013, p. 65-72.

– Thompson K. , 2007: Krista Thompson, “Preoccupied with Haiti: The Dream of Diaspora in African American Art,” in American Art , 21/3, 2007, p. 74-97.

– Thompson K. , 2009: Krista Thompson, “The Sound of Light: Reflections on Art History in the Visual Culture of Hip-Hop,” in Art Bulletin , 91/4, 2009, p. 481-505.

– Thompson K. , 2011: Krista Thompson, “The Practice of African Diaspora Art History in the United States,” in Art Journal , 70/3, 2011, p. 6-31.

– Thompson K. , 2015: Krista Thompson, Shine: The Visual Economy of Light in African Diasporic Aesthetic Practice , Durham, 2015.

– The Treasure of Ulysses Davis , 2008: The Treasure of Ulysses Davis , Susan Mitchell Crawley, (exh. cat., Atlanta, High Museum of Art, 2008), Atlanta, 2008.

– Tribe , 2007: Tania Tribe, “Visual Narrative and the Harlem Renaissance,” in Word and Image , 23/3, 2007, p. 391-413.

– Tribe , 2013: Tania Tribe, “Slavery to Hiroshima and Beyond: African American art and the Apocalypse,” in Word and Image , 29, 2013, p. 354-384.

– Vendryes , 2008: Margaret Rose Vendryes, Barthé: A Life in Sculpture , Jackson, 2008.

– Vincenti , 2006: Marissa Vincenti, “A Matter of Spirit: Aaron Douglas, Gurdjieffian Thought, and the Expression of ‘Conscious Art’,” in International Review of African American Art , 21/3, 2006, p. 11-15.

– Walker K. , 2007: Kara Walker, After the Deluge , New York, 2007.

– Walker H. , 2013: Hamza Walker, Black Is, Black Ain’t , Chicago, 2013.

– Wall , 2010: David Wall, “Transgression, Excess, and the Violence of Looking in the Art of Kara Walker,” in Oxford Art Journal , 33, 2010, p. 277-299.

– Wangechi Mutu , 2013: Wangechi Mutu: A Fantastic Journey , Trevor Schoonmaker ed., (exh. cat., Durham, Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, 2013), Durham, 2013.

– When the Stars… , 2014: When the Stars Begin to Fall: Imagination and the American South , Thomas L. Lax ed., (exh. cat., New York, Studio Museum in Harlem, 2014), New York, 2014.

– Whitehead , Shiver , 2012: Tom Whitehead, Art Shiver, Clementine Hunter: Her Life and Art , Baton Rouge, 2012.

– Williams , 2007: Carla Williams, “Maudelle Bass: A Model Body,” in Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art , 21, 2007, p. 34-46.

– Willis , 2009: Deborah Willis, Posing Beauty: African American Images from the 1890s to the Present , New York, 2009.

– Witness , 2014: Witness: Art and Civil Rights in the Sixties , Theresa Carbone, Kellie Jones, (exh. cat., Brooklyn, Brooklyn Museum, 2014), Brooklyn, 2014.

– Wolfskill , 2009: Phoebe Wolfskill, “Caricature and the New Negro in the Work of Archibald Motley Jr. and Palmer Hayden,” in Art Bulletin , 91, 2009, p. 343-365.

– Woods , 2009: Naurice Frank Woods Jr., “An African Queen at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition 1876: Edmonia Lewis’s Death of Cleopatra ,” in Meridians: Feminism, Race, Transnationalism , 9/1, 2009, p. 62-82.

– Zorach , 2011: Rebecca Zorach, “Art & Soul: An Experimental Friendship between the Street and a Museum,” in Art Journal , 70/2, 2011, p. 66-87.

1 Fully developed but relatively concise accounts of the Harlem Renaissance and the Black Arts Movement can be found in the author’s two chapters “Enter the Exit the ‘New Negro’” and “Black is a Color” ( Powell , 2002, p. 41-65, p. 121-160).

2 For an in depth examination of the historiographic breadth of African American art research, including many of the historians and critics listed in this Conclusion, see Sharon F. Patton’s comprehensive “Bibliographic Essay” ( Patton , 1998, p. 283-299).

3 Kobena Mercer, “New Practices, New Identities: Hybridity and Globalization” ( Bindman, Gates , 2014, p. 225).

Pour citer cet article

Référence électronique.

Richard J. Powell , « Research and Imagine the American Black Art Since 2005 » , Perspective [En ligne], 2 | 2015, mis en ligne le 10 décembre 2015 , consulté le 02 avril 2024 . URL : http://journals.openedition.org/perspective/6043 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/perspective.6043

Richard J. Powell

Richard J. Powell is Dean of the Humanities and the John Spencer Bassett Professor of Art & Art History at Duke University. He has written extensively on topics ranging from primitivism to postmodernism, including such titles as Homecoming: The Art and Life of William H. Johnson (1991), Black Art: A Cultural History (2002), and Cutting a Figure: Fashioning Black Portraiture (2008). From 2007 until 2010, he was Editor-in-Chief of The Art Bulletin.

Droits d’auteur

Le texte et les autres éléments (illustrations, fichiers annexes importés), sont « Tous droits réservés », sauf mention contraire.

- Personnes citées

- Noms de lieux

Publications à venir

- Numéro à paraître : 2024 – 1 : Autonomie

- Appels en cours

- Appels clos

Numéros en texte intégral

- 2 | 2023 Mode(s)

- 1 | 2023 Obscurités

- 2 | 2022 Raconter

- 1 | 2022 Transports

- 2 | 2021 Habiter

- 1 | 2021 Portugal et espaces lusophones

- 2 | 2020 Danser

- 1 | 2020 Japon

- 2 | 2019 Multiples

- 1 | 2019 Pays nordiques

- 2 | 2018 Détruire

- 1 | 2018 Actualité en histoire de l’art

- 2 | 2017 Le Maghreb

- 1 | 2017 actualité en histoire de l'art

- 2 | 2016 Bibliothèques

- 1 | 2016 Textiles

- 2 | 2015 Les États-Unis

- 1 | 2015

- 2 | 2014 Antiquité/Moyen Âge

- 1 | 2014 L’atelier

Perspective. La revue de l’INHA

- 2 | 2013 Le Brésil

- 1 | 2013 Période moderne/Époque contemporaine

- 2 | 2012 Antiquité/Moyen Âge

- 1 | 2012 Art et pouvoir

- 2 | 2011 Les Pays-Bas

- 1 | 2011 Période moderne/Époque contemporaine

- 2 | 2010 Antiquité/Moyen Âge

- 1 | 2010 Ornement/Ornemental

- 4 | 2009 XX e /XXI e siècles

- 3 | 2009 Période moderne/XIX e siècle

- 2 | 2009 L’Espagne

- 1 | 2009 Antiquité/Moyen Âge

- 4 | 2008 Périodisation et histoire de l’art

- 3 | 2008 XX e -XXI e siècles/Le Canada

- 2 | 2008 Période moderne/XIX e siècle

- 1 | 2008 Antiquité/Moyen Âge

- 4 | 2007 Genre et histoire de l’art

- 3 | 2007 XIX e siècle/XX e -XXI e siècles

- 2 | 2007 La Grande-Bretagne/Période moderne

- 1 | 2007 Antiquité/Moyen Âge

- 4 | 2006 La monographie d’artiste

- 3 | 2006 XIX e siècle/XX e siècle

- 2 | 2006 La Suisse/Période moderne

- 1 | 2006 Antiquité/Moyen Âge

Versions originales

- 2 | 2015 United States

- 2 | 2013 Brasil

Versions anglaises

Tous les numéros, perspective en perspective.

- Comptes rendus

- Sélection de sites

- Sélection de sites thématiques

- Ouvrages reçus

- Présentation

- Soumission et évaluation

- Normes éditoriales

- Abonnement/Vente

Informations

- Mentions légales

- Politiques de publication

Suivez-nous

Lettres d’information

- La Lettre de Perspective

- La Lettre d’OpenEdition

Affiliations/partenaires

ISSN électronique 2269-7721

Voir la notice dans le catalogue OpenEdition

Plan du site – Crédits – Flux de syndication

Politique de confidentialité – Gestion des cookies – Signaler un problème

Nous adhérons à OpenEdition – Édité avec Lodel – Accès réservé

Vous allez être redirigé vers OpenEdition Search

Black Arts Movement

Summary of Black Arts Movement

The Black Arts Movement, sometimes referred to as the Black Aesthetics Movement, was influential in its ability to put together social, cultural, and political elements of the Black experience and established a cultural presence in America on a mainstream level. By incorporating visual motifs representative of the African Diaspora, as well as themes of revolutionary politics supporting Black Nationalism, the Black Arts Movement overtly distanced itself from white Eurocentric forms of art. It not only highlighted the work of Black artists but sought to define a universal experience of Blackness that expressed empowerment, pride, and liberation.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- The Black Arts Movement celebrated Afrocentrism by exploring and blending images from the past, present, and future into visual imagery that would inform a modern-day lexicon using contemporary modes such as poster and commercial art, lettering, and patterning.

- The Black Arts Movement arose in tandem with Identity Art and Identity Politics, a genre in which artists focused on presenting the faces and experiences of their marginalized populations which also included women and the LGBT community. Strong aesthetics and powerful statements representing the Black racial identity emerged during this time that would come to be synonymous with the Black community such as Black Power, "cool-ade" colors and militant chic.

- The Black Arts Movement saw the rise of collectives which would, bond together and provide a solidified front for Black artists to showcase their experiences as a separate and cohesive cultural identity within the nation.

- The Black Arts Movement spurred the rise of many educational and advocacy-related initiatives that would integrate into overall American culture providing the opportunity for immersion into the communal psyche of the country.

Artworks and Artists of Black Arts Movement

The Wall of Respect

The Wall of Respect was a twenty-by-sixty-foot mural painted on the facade of a two-story building at the corner of East 43rd Street and South Langley Avenue in Chicago's Bronzeville neighborhood. The piece was an homage to Black historical and contemporary figures involved in politics, education, athletics, and the arts. Fifty unique portraits were represented of individuals who lived and worked in line with the Black Power and Black Nationalist ideologies. This included Nat Turner, Elijah Muhammad, Malcolm X, Muhammad Ali, Gwendolyn Brooks, W.E.B. DuBois, Marcus Garvey, Aretha Franklin, Nina Simone, and Harriet Tubman. During the creative process, the artists decided not to include Martin Luther King Jr. among the political leaders because he wasn't radical enough from their perspective. Art historian Kirstin Ellsworth noted that the reasoning behind this notable omission was, "the change from what Civil Rights advocates viewed as the fight for equality-based integrationist policies within the American system to separatist politics that answered to the cause of revolution on a global scale created dissension among OBAC artists contributing to the mural." Many of the artists who contributed to the public artwork were associated with the Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC), whose mission was to highlight the Black experience and struggle for racial justice in the United States through art. The mural was laid out by graphic designer Laini (Sylvia) Abernathy, while Jeff Donaldson and William Walker facilitated the painting process. The layout Abernathy developed was a modular design that divided the surfaces of the building into seven sections. These sections were the substrates that the artists painted on. Donaldson recalled that the project "was a clarion call, a statement of the existence of a people." The location of the mural was relevant as a celebration of Black culture. Bronzeville is known as Chicago's Black metropolis due to its history as an early-twentieth-century incubator for African American business and culture and home to one of the mural's subjects, the poet and educator Gwendolyn Brooks. Additional subjects were added to the Wall of Respect as the Civil Rights and Black Liberation movements progressed. Wall of Respect 's existence was short-lived and it was impacted by several acts of vandalism. The building was severely damaged by a fire in 1971, officially ending the mural's tenure in the public space. However, as historians Mariana Mogilevich, Rebecca Ross, and Ben Campkin have noted, Wall of Respect "claimed an everyday surface as a highly visible celebration of black experience and successfully elicited reciprocal identification, and a sense of collective ownership, by local people. In spite - and because - of its destruction, this revolutionary act of image-making had profound influence in the neighborhood, and inspired community mural movements around the USA and internationally."

Artist: Noah Purifoy