National Museum of African American History & Culture

- Plan Your Visit

- Group Visits

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Accessibility Options

- Sweet Home Café

- Museum Store

- Museum Maps

- Our Mobile App

- Search the Collection

- Exhibitions

- Initiatives

- Museum Centers

- Publications

- Digital Resource Guide

- The Searchable Museum

- Freedmen's Bureau Search Portal

- Early Childhood

- Talking About Race

- Digital Learning

- Strategic Partnerships

- Ways to Give

- Internships & Fellowships

- Today at the Museum

- Upcoming Events

- Ongoing Tours & Activities

- Past Events

- Host an Event at NMAAHC

- About the Museum

- The Building

- Meet Our Curators

- Founding Donors

- Corporate Leadership Councils

- NMAAHC Annual Reports

The Foundations of Black Power

Black power emphasized black self-reliance and self-determination more than integration. Proponents believed African Americans should secure their human rights by creating political and cultural organizations that served their interests.

They insisted that African Americans should have power over their own schools, businesses, community services and local government. They focused on combating centuries of humiliation by demonstrating self-respect and racial pride as well as celebrating the cultural accomplishments of black people around the world. The black power movement frightened most of white America and unsettled scores of black Americans.

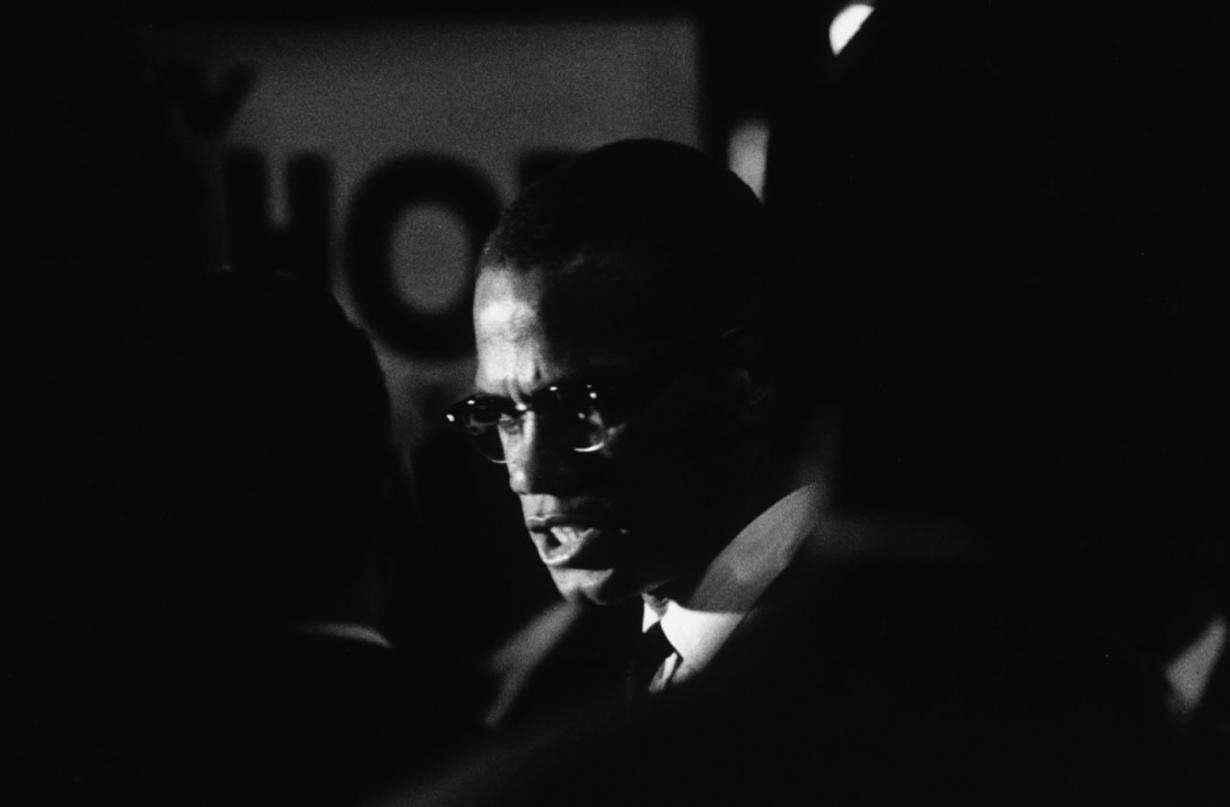

Malcolm X The inspiration behind much of the black power movement, Malcolm X’s intellect, historical analysis, and powerful speeches impressed friend and foe alike. The primary spokesman for the Nation of Islam until 1964, he traveled to Mecca that year and returned more optimistic about social change. He saw the African American freedom movement as part of an international struggle for human rights and anti-colonialism. After his assassination in 1965, his memory continued to inspire the rising tide of black power.

Malcolm X speaking in front of the 369th Regiment Armory, 1964.

More than any other person, Malcolm X was responsible for the growing consciousness and new militancy of black people. Julius Lester 1968

Malcolm X’s expression of black pride and self-determination continued to resonate with and engage many African Americans long after his death in February 1965. For example, listening to recordings of his speeches inspired African American soldiers to organize GIs United Against the War in Vietnam in 1969.

This 16mm film is a short documentary made by Madeline Anderson for National Education Television's Black Journal television program to commemorate the four year anniversary of the assassination of Malcolm X.

Stokely Carmichael Stokely Carmichael set a new tone for the black freedom movement when he demanded “black power” in 1966. Drawing on long traditions of racial pride and black nationalism, black power advocates enlarged and enhanced the accomplishments and tactics of the civil rights movement. Rather than settle for legal rights and integration into white society, they demanded the cultural, political, and economic power to strengthen black communities so they could determine their own futures.

Martin Luther King Jr.'s former associate Stokely Carmichael speaks at civil rights rally in Washington, April 4, 1970.

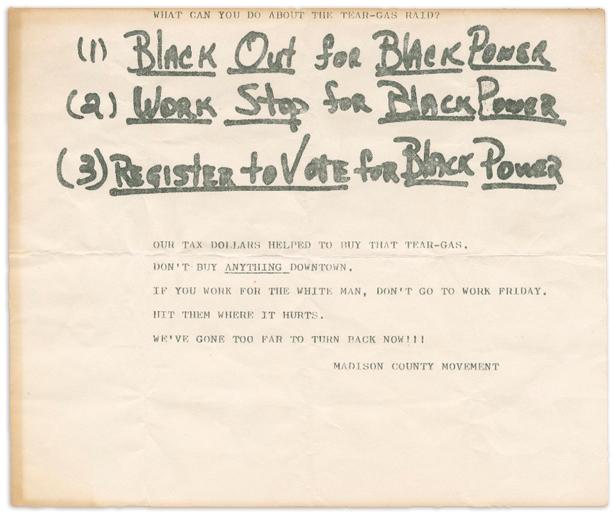

Black Power Intertwines with Civil Rights Organizers made no distinctions between black power and nonviolent civil rights boycotts in Madison County, Mississippi, 1966.

Flyer for the Madison County Movement, founded 1963.

SNCC Supports Black Power SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, created in 1960, destroyed “the psychological shackles which had kept black southerners in physical and mental peonage,” according to its chairman, Julian Bond.

Julian Bond standing and writing as a young African American boy watches closely, 1976.

Protest, Teaneck, New Jersey Building on the successes of the civil rights movement in dismantling segregation, the black power movement sought a further transformation of American society and culture.

A woman sits on a bench outside the Black Panther office in Harlem circa 1970 in New York City. Pictured in the window are Panther founders Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale.

Black Power Around the World Revolutions in other nations inspired advocates of black power. The African revolutions against European colonialism in the 1950s and 1960s were exciting examples of success. Wars of national liberation in Southeast Asia and Northern Africa offered still more encouragement. Stokely Carmichael’s five-month world speaking tour in 1967 made black power a key to revolutionary language in places like Algeria, Cuba and Vietnam.

Sharpeville massacre: Dead and wounded rioters lie in the streets of Sharpeville, South Africa, following an anti-apartheid demonstration organized by the Pan-Africanist Congress which called upon Africans to leave their passes at home, March 21, 1960. The South African police opened fire on the crowd, killing 69 people and injuring 180 others.

Protesting Apartheid, Cape Town, South Africa In 1972 African Americans began annual celebrations of African Liberation Day to commemorate and support liberation movements in Africa.

This flyer announces a protest against apartheid in South Africa, 1977. Pan African Students Organization in the Americas (1960 - 1977) and Youth Against War & Fascism , founded 1961.

“Free All Political Prisoners!” Critics vilified black power organizations as separatist groups or street gangs. These critics ignored the movement’s political activism, cultural innovations and social programs. Of nearly 300 authorized FBI operations against black nationalist groups, more than 230 targeted the Black Panthers. This forced organizations to spend time, money, and effort toward legal defense rather than social programs.

A round, yellow pinback button with a photographic portrait of Angela Davis in the center, 1970-72.

The War on Black Power Between 1956 and 1971, the FBI and other government agencies waged a war against dissidents, especially African Americans and anti-war advocates. The FBI’s Counterintelligence Program (COINTELPRO) targeted Martin Luther King Jr., the Black Panthers, Us and other black groups. Activities included spying, wiretapping phones, making criminal charges on flimsy evidence, spreading rumors and even assassinating prominent individuals, like Black Panther Fred Hampton. By the mid-1970s, these actions helped to weaken or destroy many of the groups associated with the black power movement.

The Black Panther Party, without question, represents the greatest threat to the internal security of the country. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover 1969

Olympic Medalists Giving Black Power Sign, 1968 Tommie Smith (center) and John Carlos (right) gold and bronze medalists in the 200-meter run at the 1968 Olympic Games. During the national anthem, they stand with heads lowered and black-gloved fists raised in the black power salute to protest against unfair treatment of blacks in the United States. Australian Peter Norman is the silver medalist (left).

Subtitle here for the credits modal.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Art

- History of Art

- Theory of Art

- Browse content in History

- Environmental History

- History by Period

- Intellectual History

- Political History

- Regional and National History

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Psycholinguistics

- Browse content in Literature

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Religion

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cultural Studies

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Browse content in Law

- Criminal Law

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Palaeontology

- Environmental Science

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- History of Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Information and Communication Technologies

- Browse content in Economics

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Public Economics

- Browse content in Environment

- Climate Change

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Interdisciplinary Studies

- Browse content in Politics

- Asian Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Environmental Politics

- International Relations

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Economy

- Political Theory

- Public Policy

- Security Studies

- US Politics

- Browse content in Social Work

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Browse content in Sociology

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Sport and Leisure

- Reviews and Awards

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

- < Previous chapter

8 Conclusion: Institutionalizing Black Power

- Published: June 2014

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This concluding chapter revisits popular conceptions of the Black Power movement, considering its role in the development of black professional associational life. It explores the idea of treating the Black Power era as a transition period in race relations. The Black Power movement created interracial interactions in established integrated organizations, and was the prevalent organizing frame for African Americans seeking change within them. While the civil rights movement took significant action against racial discrimination, it had concerned itself primarily with access to institutions that had previously been closed to African Americans, which is not enough. African Americans had to mobilize Black Power ideas, norms, strategies, and tactics within various organizations in order to devise organizational structures that promote racial equality.

because the black power movement has been marginalized in the sociological study of social movements, its impacts have been underestimated. While the black cultural transformation it ushered in is critically important, the movement also had significant institutional outcomes. The Black Power movement shaped interracial interactions in established and emerging integrated organizations, and was the dominant organizing frame for African Americans seeking change within them during the late 1960s and early 1970s. The content of the movement gave form to the relationships within the organizations that African Americans found themselves in. While the civil rights movement had made great strides against racial discrimination, it had concerned itself primarily with access to institutions and organizations that had previously been closed to African Americans. But when access was finally gained, the work was not done. Indeed, African Americans mobilized Black Power ideas, norms, strategies, and tactics within a variety of organizations to hold them accountable for new norms of interracial interaction and to craft organizational structures that promoted racial equality. These struggles often resulted in the development of independent black organizations, which was in line with a central call of the Black Power movement. Most of the independent organizations that developed were founded on Black Power principles and sought to support the goals of the movement, which included challenging white racism, affirming a unique black identity, providing safe spaces to develop black agendas, and protecting the interests of African Americans embedded their institutional contexts. These institutional changes and independent organizations, many of which still exist today, are primary outcomes of the Black Power movement that are worthy of further investigation, and suggest the need for reexaminations of this era as a period of racial transformation and the movement itself as an important precursor to contemporary projects for racial equity that have benefited the black middle class.

Race Relations in Transition

Tensions and uncertainties surrounded the uneasy transition to the fuller, more complete integration happening in U.S. society during the Black Power movement. Rising numbers of black professionals entering integrated workplaces intersected with the dominance of the Black Power ideology to create some tense interracial interactions. This assessment of black social workers organizing during the movement reveals a complex set of relationships between blacks and whites, often characterized by black desires to hold whites accountable for the changes to racial etiquette and practice required by the Black Power movement along with white responses of resentment, fear, and defensiveness. These relational tensions were played out in struggles over institutional change within the profession.

This study also reflects a much broader transformation in relations between blacks and whites in American society. However, there is a relative dearth of studies that attempt to delve into the relational aspects of race relations during the transition to integration. Elizabeth Lasch-Quinn’s Race Experts (2001) is one example. In her book, she attempts to analyze “what happened to racial etiquette in the era of integration” (8) through an examination of popular culture sources, developments in black scholarship, and the development of the “diversity industry.” She writes a seething critique of the so-called race experts—the diversity counselors, academics, activists, etc.—whom she claims hijacked the colorblind vision of the civil rights movement, turning it on its head to actually reinscribe racial oppression by valuing difference rather than disavowing it. Drawing on both contemporary and historical popular culture sources, ranging from Tom Wolfe’s essay “Radical Chic” to the film Jerry McGuire , Lasch-Quinn argues that a cultural script of black assertiveness and white submission and guilt became the central mode of “doing the interracial thing” as a result of the Black Power era.

My points of agreement with Lasch-Quinn (and this line of argument in general) are few. I do agree that it is necessary to examine this crucial transition period in race relations, and that there are insights from this period that help us to understand how American society has progressed in the project of racial justice. However, my research does not support her notion that racial etiquette shifted in such a way that black assertiveness was met with white submission. Rather, an analysis of these interactions in the field of social work shows that black demands for respect, representation, and new organizational arrangements to support these shifts were more often met with white resentment and anger rather than submission as Lasch-Quinn would suggest. Whites did not stop using belittling and patronizing language about their black colleagues even in the face of black assertion. From arguing that people of color were “beguiled by their own rhetoric” when they made demands to accusing them of being “guilty of overkill” when they were given concessions, many white reactions primarily served to downplay black concerns. Further, white leadership often found ways to subvert black demands with partial responses and symbolic concessions, continuing to feel that they knew what was best. So contrary to Lasch-Quinn’s assertions, this research does not find whites simply cowering in the face of a big black threat. Still, though it is this relationship that she argues resulted in the current state of diversity politics, it is simply not the case that black requirements for racial sensitivity by whites made the bed we now lie in. Lasch-Quinn and other critics of identity politics would have us believe that whites were more than willing to throw out all racial distinctions and that black people, because they insisted on affirming a uniquely black identity and asserting new ways of doing race, are to blame for ongoing racial inequality. But the historical record simply does not support this characterization.

On the contrary, it is elite responses, rooted in a desire to maintain power relations “as is” while doling out token representation and engaging in symbolic celebrations of difference rather than really answering the call to relinquish privilege and control in favor of more egalitarian race relations that resulted in the “multiculturalism” we still see today. It is true that many whites responded to Black Power with fear, which lead them to cling more tightly to the power they had. In the case of social work professional associations, this reaction was framed as a desire to value “establishment” and to not be pressured into giving up old ways of doing things just because “hot-blooded” militant blacks said so. But the central problematic of U.S. race relations is white power, white privilege, and white racism, not some sort of adherence to domination in a general neutral sense. In this way, it is white resistance to Black Power that resulted in us missing the racial equality boat the movement may have launched.

Revisiting Black Power

The important and lasting impact of African American activism in the professions forces us to rethink what Black Power was in a way that expands the boundaries of the movement. To be sure, the Black Power movement is more important than popular accounts let on. While the Black Panther Party and similar organizations were vital parts of the movement, their story is not the whole story. The truth is, African Americans who were both inspired and emboldened by the movement’s ideas and figures brought Black Power with them into the institutional context of their lives. Indeed, African American professionals struggled to insert themselves and their interests into civil society through movement-like phenomena within organizations. This Black Power “march through the institutions” should be seen as a part of the movement that, while not the same as more radical manifestations of the movement, had an important impact in society. These efforts to carve out space in existing institutions and build new institutions for the purpose of developing, guarding and promoting black interests shaped and continue to shape the civil sphere in the United States.

In all, black organizing within the professions had at least three important effects. First, the creation of black professional associations—along with the creation of black studies programs, black student associations, and so forth—changed the organizational landscape that all individuals encounter as we make our way through professional training and development. The existence of black professional associations in many of the professions continues the tradition of maintaining the black institutional space that African American professionals built during the Black Power era. Secondly, that black professional associations were so strongly influenced by Black Power created a blueprint for a black professional identity and a commitment to “race politics” as a new professional ethic, an ideology which continues today and works to create a real dividing line around what it means to be authentically black in the world of professional work. Third, the activism of black professionals changed the norms of interaction between blacks and whites, creating frames for understanding workplace racism and how to go about challenging it. In many ways, these norms provide a more effective vehicle for challenging workplace racism than the relatively impotent policies developed around racial harassment. While the law purportedly protects people of color from discrimination in hiring decisions, it does little to protect them from the kinds of interpersonal racism that African Americans embedded in white organizations often face. The development of new professional norms that provide people of color a framework for checking and managing racist behavior from white colleagues is in some cases the only protection that African Americans have in the workplace, particularly against the kinds of racism that create hostile work environments.

Along with these impacts, white responses to black professional organizing laid the roots for a form of corporate and educational “diversity” project that is now nearly completely devoid of its liberatory roots in the Black Power movement. Elite responses, firmly rooted in white emotional reactions to being the targets of dissent in these institutional spaces, created a framework for conciliatory symbolic concessions that were never intended to result in actual power sharing. In other words, white resistance to relinquishing privilege—coupled with Black Power’s emphasis on representation and identity—in many ways paved the path to multiculturalism. Indeed, contemporary forms of diversity and multiculturalism are often examples of the tokenism and symbolic representation that Black Power advocates struggled against: acts of recognition, celebration even, that are devoid of any challenge to existing power relations. They are exactly what Carmichael and Hamilton (1966) warned against when they said that, “Black visibility is not Black Power” (48).

Finally, these middle class black professionals, inspired by the Black Power movement, sought a solution to the white subordination of the black community through the racialization of social issues. One way to conceive of this outcome is that, whether intended or not, black social workers’ solution to white patronization of the black poor can sometimes be characterized as a changing of the guard from white to black officials rather than a real challenge to the practice of social control. As Adolph Reed (1979) put it, “the movement failed because it succeeded.” He argues:

Through federal funding requirements of community representation, reapportionment of electoral jurisdictions, support for voter “education” and growth of the social welfare bureaucracy, the Black elite was provided with broadened occupational opportunities and with official responsibility for administration of the Black population. The rise of Black officialdom in the latter 1970s signals the realization of the reconstructed elite’s social program and the consolidation of its hegemony over Black life. (84)

In other words, by placing black bodies in previously white positions, the movements of the period, combined with new directions in social welfare, did little to overthrow the structure of power relations that maintained domination writ large. Their success in changing professional structures and organizations, however, suggests that Black Power had unexpected benefits for the black middle class.

Black Professional Associations

Citing the economic losses that black families experienced between 1968 and 1988, Audreye Johnson wrote, “NABSW arose out of the climate of times.” The founding of the National Association of Black Social Workers and other organizations like it were certainly responses to economic and social crises and to white racism. But they arose out of more than just the quantitative and qualitative condition of African Americans at the time. The NABSW and its counterparts were also products of the dominance of Black Power as a political and social ideology. Many of these organizations, however, are still in existence today, which begs the following questions: do they still reflect a black power ethic? Do they still serve the same functions as they did in the late 1960s and early 1970s?

The Black Power influence is certainly still obvious in the NABSW. Their history of struggle continues to be central to the organization’s contemporary identity. In the message from National Conference Co-chairs Zelma Smith and Judith D. Jackson printed in the 2008 commemorative program of the 40th meeting of the NABSW in Los Angeles, they write, “Remember why you are here! Also remember that our ancestors and founders made the supreme sacrifice to establish this significant and meaningful organization. The challenges we face today are no less than those that confronted our forefathers and foremothers. As they accepted their roles in the history of the struggle, so must we accept our roles and struggles.” Then-president Gloria Batiste-Roberts also wrote:

40 years ago NABSW began with a dream in California that has now grown into a vibrant national organization with international influence. So, in honor of our 40 years of advocacy and activism, we have returned to California to reflect on where we have been and to honor those whose shoulders carry us still. As NABSW moves into its fifth decade, we will use our time together this week to articulate and recommit ourselves—as a group and as individuals—to 40 more years of commitment to our community. 1 Close

The organization clearly pays homage to their founders and sees their legacy as crucial to their current identity.

Black professional associations, while having moved closer to the professional development side of their concerns, still retain an element of the earlier focus on protest. The NABSW, for example, continues to write position papers on issues they see as important to the black community, such as a 2002 published paper on welfare reform. The organization also maintains a civil liberties and social justice task force.

Black professional associations often take on issues of interest to their profession that may not be conceived of as such by their white counterparts. One case in point is the official statement issued by Association of Black Sociologists (ABS) on the Trayvon Martin case in 2010. In February 2010, Martin, a 17-year-old African American boy, was shot and killed in Florida by George Zimmerman, a neighborhood watchman. His murder resulted in nationwide protests. In releasing such a statement, the Association of Black Sociologists affirmed its commitment to activism and encouraged sociologists to continue to use their research and other resources in the struggle against racism. The statement reads, in part,

As an organization historically committed to community action and social transformation, the Association of Black Sociologists (ABS) stands in support of these protest efforts. We encourage all ABS members to contact your local, state, and national legislators to continue to challenge the Justice Department and FBI to thoroughly investigate the crime, apprehend Zimmerman, and secure justice not only for Trayvon Martin and his family, but also for the nation as a whole. Furthermore, continued pressure is required to amend, reevaluate, and in many cases repeal “Stand Your Ground” legislation across this country—laws tantamount to state-sanctioned use of deadly force against innocent individuals. ABS members are encouraged to remain vigilant in the continued struggle to monitor and proactively respond to all forms of inequality experienced by marginalized people. 2 Close

While the activism of today’s black professional associations is certainly different than the kind of activism they engaged in during the Black Power movement, it reflects a continued commitment to social justice. Statements like this suggest that black professional associations still have something unique to offer those black professionals who are interested in creating a more just and equal society.

Members of black professional associations have varied motivations for membership and can have as many different needs from their associations as there are members. Still, there is evidence that many intend to continue serving the dual functions of professional development and advancement on the one hand and addressing issues important to the black community on the other. In her 2012 presidential address , Sandra Barnes, 36th president of the Association of Black Sociologists (ABS), challenged members to

re-imagine and re-embrace a time and a tradition of Black Sociology that reflects: 1. Our rich inheritance and customs associated with social activism; 2. Community service informed by rigorous research; 3. Dogged determinism to dismantle negative structural forces that undermine the lived experiences of oppressed groups everywhere; and 4. Personal initiative and sacrifice to think of others before ourselves. 3 Close

Both Dr. Batiste-Roberts and Dr. Barnes issue challenges to their members to recommit to the fight for social justice in black communities. This reflects the fact that while black professional associations today are primarily focused on professional development and coordination, the commitment to activism and racial justice remains. As such, this book identifies the space of possibility for black professional associations moving forward. One of the most important ways that black professional associations can continue to do racial justice work is by identifying the spaces within their field that affect people of color and concentrating their work there. Much like how black psychologists addressed the issue of racism in IQ testing and black social workers addressed racism in the child welfare system, today’s black professional associations can focus their work to create meaningful social change within their unique spheres of influence.

1. National Association of Black Social Workers , conference booklet, Ma’at, Sankofa, & Harambee: 40 Years Strong: 40th Annual Conference Souvenir Journal , April 1–5, 2008, in author’s possession.

2. Association of Black Sociologists , e-mail sent to members, “Statement in Support of Trayvon Martin Protests,” March 27, 2012, in author’s possession.

3. Sandra Barnes , “Presidential Address,” August 12, 2012, Annual Meetings of the Association of Black Sociologists, Denver, Colo.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

Gr. 12 HISTORY REVISION: THE BLACK POWER MOVEMENT

REVISION: THE BLACK POWER MOVEMENT

Do you have an educational app, video, ebook, course or eResource?

Contribute to the Western Cape Education Department's ePortal to make a difference.

Home Contact us Terms of Use Privacy Policy Western Cape Government © 2024. All rights reserved.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

BLACK POWER MOVEMENT

Related Papers

Sidahmed ZIANE

This paper revisits the Black Power scholarship by analyzing the major and the new trends that appeared in its historiography in the last two decades.

Nance M Musinguzi

My research paper will discuss the elements of black consciousness and the unification of the African Diaspora through the establishment of the Black Power Movement, particularly focusing on the ideologies and teachings of black revolutionary leaders Malcolm X and Stockley Carmichael. I look to examine how the discovery of an ethnic identity can reshape the attitudes of black-Americans, specifically on the ideas of American citizenship, privilege and nationalist ideology. Does the prior memory of one’s being still remain – whether embraced or rejected – or does the embrace of a newfound identity override its remnants? What do nationalism and its historical rooting in Pan-Africanism do to this renewed identity? How has the definition of blackness been refined over the course of 15 years during this era of ethnic rebirth? As Carmichael stated, “We must do as Brother Malcolm says, we should examine history” in redefining and reclaiming the essence of blackness. The end goal of the Movement was to encourage black youth in America to adopt the black nationalist principles to transcend political, economic and social barriers and to empower the self through a revamped image of the Afro-American, the re-invention of the meaning of blackness, particularly against antitheses of normative societal expectations of the black community. Thus, through the re-examination of history, Malcolm X and Stockley Carmichael ignited black youth to redefine the ideals of “blackness” through empowerment by means of the Black Power Movement and ideas of black consciousness, in addition to restoring the essence of the Black experience within an American construct utilizing political power, shifting attitudes and thoughts of the black-American identity.

Fela Amiri Uhuru

The History of Black Studies

Yohuru Williams

The Black Power Movement represents one of the most important and controversial social and political movements in postwar American history. This graduate redings course examines how the movement for black political self-determination during the 1960s and 1970s transformed American race relations, accelerated the pace of black elected officials nationally, erected new educational, social, political, and cultural institutions nationwide and redefined black politics, identity, and culture. We will also explore the movement’s critique of, and participation in, civil rights struggles; its reimagining of American Democracy; efforts to gain political and economic power within America society while redrawing the landscape of race relations.

Mabogo More

By providing the readers with some context in which Black Arts, Black Power Freedom Movements, and Black Aesthetics matured Cedric Robinson’s Black Marxism, juxtaposed with Jodi Melamed’s Represent and Destroy :Rationalizing Violence In the New Racial Capitalism, and Jordan T. Camp’s Incarcerating the Crisis: Freedom Struggles and the Rise of the Neoliberal State we can potentially navigate ourselves out of the muck of the class and/or/vs race but asking a different question: how do the authors identify the relationship of race and capitalism, and how does the expressive culture of the Black Radical Tradition produce alternative epistemologies about different social and economic systems and relations grounded in Black cosmologies ? I will argue in this paper that the Black Radical Tradition needs to become fully conscious of it-self in order frame addressing the race/class nexus (Fanon, 1967, in Welcome, 2007; Robinson, 1983/2000). Nonetheless, we need to pay attention to the modern movements and the practices on how to exposes the contradictions between race and capitalism. First, I will provide a quick historical development of the Black Radical Tradition through Robinson’s Black Marxism, where he traces the Black Radical Tradition from the 16th century to the present. Second, this will take us to the 1960s-1960s of transnationalism, and anti-imperialism of black freedom fighters Claudia Jones, C.L.R. James, Frantz Fanon, Aime Cesaire, Angela Davis, George Jackson, Huey Newton, Malcolm X, MLK Jr, and how this time was an opportune time for both black, natives and the global take advantage of that moment. Thereby producing a mature black radical formation constituted on the multiple crisis of the 50s, 60s, and 70s. I will list what in my view characterizes a modern Black Radical Tradition.

Journal of African American Studies 16(1): 1-20

Kabria Baumgartner , Jonathan Fenderson

Fabio Cesar Silva Rojas

Race & Class 55(1): 1-22

Jonathan Fenderson

The recent explosion in US scholarship on the Black Power Movement provides the context for this close reading and textual analysis of Peniel Joseph's latest book, "Dark Days, Bright Nights: from Black Power to Barack Obama." Taking into account the context of the book's appearance and the critical public debate surrounding it, this article unpacks Joseph's discussion of Black Power, paying particular attention to his rendering of 'self-determination' and other key political ideologies. It asks what is at stake for Black radical memory when knowledge production on the Black Power Movement is governed by the dictates of the American marketplace and, more specifically, the publishing industry. In addition, it briefly reconnoiters the ways that Black radical (collective) memory can serve as a counterbalance to the erasures of marketplace history, and keep us attentive to the contemporary pertinence and unfinished business of the past. The article closes by highlighting some alternative routes taken by scholars concerned with the future of Black Power Studies.

RELATED PAPERS

Mauri de Souza

Tourism & Management Studies

Celísia Baptista

Kacem Chehdi

Journal of Gastroenterology, Pancreatology & Liver Disorders

Regina Teixeira

Chemical Physics Letters

JOSE CRISLANIO SANTOS SILVA

International Dairy Journal

Gianfranco Mamone

Indian Journal of Fisheries

Anjana Ekka

Debates do NER

Juan Cruz Esquivel

Microchemical Journal

Diogo Rocha

patrick kariuki

Worku Tefera

The Journal of Qazvin University of Medical Sciences

Akram Shahrokhi

Pakistan journal of pharmaceutical sciences

SSRN Electronic Journal

Ariadne Plaitakis

Agustini Ernawati

Journal of Pure and Applied Algebra

Diversitas Journal

Eliane Satu dos Santos

Sajawal Khan

Kronika Ziemi Trzcianeckiej

Dariusz Chojecki

rtytrewer htytrer

Fitopatologia Brasileira

Luadir Gasparotto

Aquatic Conservation-marine and Freshwater Ecosystems

Gert Van Hoey

Orvosi Hetilap

Lóránt Illésy

arXiv (Cornell University)

Alan Anwer Abdulla

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

The Black power movement : rethinking the civil rights-Black power era

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

7 Favorites

Better World Books

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station40.cebu on May 29, 2023

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The Black power movement. Part 1, Amiri Baraka from Black arts to Black radicalism [microform] / editorial adviser, Komozi Woodard; project coordinator, Randolph H. Boehm. p. cm.—(Black studies research sources) Accompanied by a printed guide, compiled by Daniel Lewis, entitled: A guide to the microfilm edition of the Black power movement.

The black power movement, in its challenge of postwar racial liberalism, fundamen-tally transformed struggles for racial justice through an uncompromising quest for social, political, cultural, and economic transformation. The black power movement's activi-ties during the late 1960s and early 1970s encompassed virtually every facet of African

The Black Power movement represents a largely unchronicled epic in American history. Black Power fundamentally altered struggles for racial justice through an uncompromising quest for social, political, and cultural transforma. tion. The movement's sheer breadth during the late 1960s and early.

Historians of the era generally portray the period between the Garvey movement of the 1920s and the Black Power movement of the 1960s as one of declining black nationalist activism, but Keisha N ...

The black power movement frightened most of white America and unsettled scores of black Americans. Malcolm X The inspiration behind much of the black power movement, Malcolm X's intellect, historical analysis, and powerful speeches impressed friend and foe alike. The primary spokesman for the Nation of Islam until 1964, he traveled to Mecca ...

this essay. 1 Taylor Branch, Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954-63 (New York, 1988); Branch, ... The Black Power Movement, Democracy, and America in the King Years 1003 Black Power transformed struggles for racial justice by altering notions of iden tity, citizenship, and democracy.5 Its practical legacies can be seen in the ...

Overview. "Black Power" refers to a militant ideology that aimed not at integration and accommodation with white America, but rather preached black self-reliance, self-defense, and racial pride. Malcolm X was the most influential thinker of what became known as the Black Power movement, and inspired others like Stokely Carmichael of the ...

The Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM) was the only secular political organization that Malcolm X joined before his fateful trip to Mecca in 1964 . Early in 1963, Malcolm took the young Philadelphia militant Max Stanford under his wing. During the last few years of Malcolm's life, few persons were as closely associated with him as was the ...

In a systematic survey of the manifestations and meaning of Black Power in America, John McCartney analyzes the ideology of the Black Power Movement in the 1960s and places it in the context of both African-American and Western political thought. He demonstrates, though an exploration of historic antecedents, how the Black Power versus black ...

Peniel E. Joseph, Waiting 'Til the Midnight Hour: A Narrative History of Black Power in America (New York, 2007); James Smethurst, The Black Arts Movement: Literary Nationalism in the 1960s and 1970s (Chapel Hill, 2005); and Jeffrey O. G. Ogbar, Black Power: Radical Politics and African American Identity (Baltimore, 2005). On the role of Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam in the development of ...

Overall, the emphasis in black politics in the 1980s continued to re ect the pattern of inatten-. tion to Black Power theoretically, and to a lesser extent, BPM organizations (see also Smith 1981 ...

The essays in this volume are an eclectic group of works that seek to do the following: a) provide a more nuanced historiography of the Black Power Movement, b) situate some of. America's most iconic figures within the dynamic construct of Black Power, c) highlight the role. that female Black Powerites played in the cultural nationalist ...

The Black Power movement shaped interracial interactions in established and emerging integrated organizations, and was the dominant organizing frame for African Americans seeking change within them during the late 1960s and early 1970s. ... ranging from Tom Wolfe's essay "Radical Chic" to the film Jerry McGuire, ... This PDF is available ...

NSC Internal Moderators Reports 2020 NSC Examination Reports Practical Assessment Tasks (PATs) SBA Exemplars 2021 Gr.12 Examination Guidelines Assessment General Education Certificate (GEC) Diagnostic Tests

The Black Power Movement represents one of the most important and controversial social and political movements in postwar American history. This graduate redings course examines how the movement for black political self-determination during the 1960s and 1970s transformed American race relations, accelerated the pace of black elected officials ...

The Black Power Movement represents one of the most important and controversial social and political movements in postwar American history. This graduate redings course examines how the movement for black political self-determination during the 1960s and 1970s transformed American race relations, accelerated the pace of black elected officials nationally, erected new educational, social ...

Black Power Movement was a critical step to becoming politically and socially conscious. In turn, the emphasis of legacies is placed on the importance of education. The emphasis on education insinuates that adolescent students today can relate easily to these criticisms, considering that aspects of critical race theory, multiculturalism, and ...

when establishing agendas. For instance, in Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America (1967), the published manifesto that helped to define (without unifying) the Black Power movement, Carmichael and Charles V. Hamilton provided "a political framework and ideol-ogy which represents the last reasonable opportunity for this society

The black power movement or black liberation movement was a branch or counterculture within the civil rights movement of the United States, reacting against its more moderate, mainstream, or incremental tendencies and motivated by a desire for safety and self-sufficiency that was not available inside redlined African American neighborhoods. Black power activists founded black-owned bookstores ...

xii, 385 p., 10 p. of plates : 23 cm Includes bibliographical references (p. 279-354) and index Introduction : toward a historiography of the Black power movement / Peniel E. Joseph -- "Alabama on Avalon" : rethinking the Watts uprising and the character of Black protest in Los Angeles / Jeanne Theoharis -- Amiri Baraka, the Congress of African People and Black power politics from the 1961 ...

The Black Power Movement was a political and social movement whose advocates believed in racial pride, self sufficiency and equality for all people of black and African descent. This essay will critically discuss the significant roles played by various leaders during the black power movement in USA. To begin with, the black power movement is ...

An essay that explains the origins, aims and methods of the Black Power Movement in the 1960s. It discusses the role of Malcolm X, the Black Panther Party and the concept of Black Nationalism in the movement.

Black power is an umbrella term given to a movement for the support of rights and political power for black people in America during the 1960's. Unlike Civil Rights, its motives weren't necessarily complete equality between American citizens, but rather the goal and belief of black supremacy. Black Power is generally associated with figures ...