- Common misconceptions

- Set Your Location

- Learn the signs

- Symptoms of autism

- What causes autism?

- Asperger syndrome

- Autism statistics and facts

- Learn about screening

- Screening questionnaire

- First Concern to Action

- Autism diagnosis criteria: DSM-5

- Newly diagnosed

- Associated conditions

- Sensory issues

- Interventions

- Access services

- Caregiver Skills Training (CST)

- Information by topic

- Resource Guide

- Autism Response Team

- Our mission

- Our grantmaking

- Research programs

- Autism by the Numbers

- Fundraising & events

- World Autism Month

- Social fundraising

- Ways to give

- Memorial & tributes

- Workplace giving

- Corporate partnership

- Become a partner

- Ways to engage

- Meet our Partners

- Deteccion de autismo

- Deteccion temprana

- My Autism Guide

- Select Your Location

Please enter your location to help us display the correct information for your area.

Teaching children with nonverbal autism to read

This week’s “Got Questions?” response is by psychologist Charlotte DiStefano, an Autism Speaks Meixner Postdoctoral Fellow in Translational Science, at the University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. DiStefano’s Autism Speak Meixner Fellowship in Translational Research involves identifying brain activity patterns that relate to language and literacy abilities in minimally verbal children with autism. The hope is to guide the development of individualized therapy and educational programs that best address each child’s needs.

Any suggestions for teaching a nonverbal 8-year-old to read? He can form sentences using augmentative communication.

I’m so glad you’ve asked this question. Many people wrongly assume that children who don’t speak can’t learn to read. But that’s definitely not true!

Two years ago, I published the results of a small study on the effectiveness of a reading program adapted for minimally verbal 5 and 6 year olds . All the students showed increased story comprehension and engagement. Unfortunately we have little other research on reading ability – or literacy – among minimally verbal kids with autism. As a result, we really don’t know how many nonverbal or minimally verbal children with autism can read or have the ability to learn how to read.

But many parents and professionals can tell you of children who can read despite not using spoken language. So we know it’s possible. What I find especially amazing is that many of these children seem to figure out how to read on their own – because no one ever gave them direct literacy instruction.

I’ve worked with several minimally verbal and non-verbal kids who showed me that they could read. They did so in various ways: matching words and sentences to pictures, typing words and/or following written text with a finger as an adult reads a book.

One of the major challenges to teaching reading to minimally verbal kids is that traditional literacy instruction relies heavily on spoken language. As you’ll probably recall from your own first grade experience, learning to read usually involves a big focus on phonics: Teachers have children enunciate the sounds of letters. Then the children learn how these sounds combine to form words.

For kids who use no or minimal spoken language, this obviously presents some difficulty. How can a child learn to “sound out” words when he or she has difficulty making sounds?

Fortunately there are many ways to teach reading that don’t depend on a child using spoken language.

How to teach nonverbal children to read

1. spend lots of time reading with your child.

First and foremost, I recommend spending lots of time reading with your child! We know that reading with children encourages their development of language and reading.

One of the most beneficial aspects of shared reading is the dialogue between the adult and child, as they discuss the book that they are reading. Although minimally verbal kids won’t be able to have a verbal conversation about the book, they can very much engage non-verbally with the book and the reader.

2. Nonverbal interactive reading

As you read with your child, give him opportunities to interact nonverbally.

Here are some activities you can share as you read:

- Run your finger just under the text as you read. Then ask your child do the pointing.

- Ask your child to turn the pages at the right time.

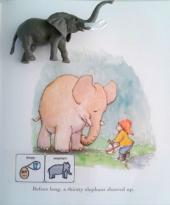

- Give your child some story props so he can act out the story as it unfolds.

- Take turns imitating what the characters are doing.

These and similar activities will help your child engage with a book without relying on spoken language.

3. Discuss stories using assisted communication

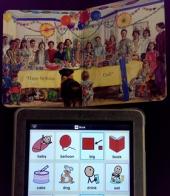

It’s great to hear that your child uses an augmentative and assistive communication (AAC) device. The device can provide your child with added opportunities to interact with you and the book you’re reading together. Before reading a new book, make sure that the system has a good array of symbols related to the story. For example, if you’re reading a book about a birthday party, make sure you have downloaded symbols for, say, “party,” “presents,” “cake” and “balloons.” As you read a story or book, use the symbols to discuss the characters and actions.

The AAC system itself offers great opportunities for developing literacy. Make sure that the device is set to display the words that go with each picture symbol. This will help your child associate written words with objects and actions.

As your child becomes more familiar with the printed words, I suggest gradually reducing the size of the accompanying pictures while increasing the size of the text. Once he’s comfortably recognizing the text, you may be able to remove the pictures entirely!

4. Reading and writing with speech-generating devices

The typing function on speech-generating devices is another wonderful avenue for developing literacy. I’ve worked with minimally verbal children who, after watching me program new words into their device, suddenly start choosing their own symbols and typing in what they want to say!

Since we didn’t know these kids could read, we were certainly surprised! And once they figured out that they could type in words of their choosing, they became much more independent communicators.

Though your child may not yet be able to type and spell words, let him watch as you program new words into the device. Explain what you’re doing. You never know when he’ll surprise you and start typing the words he wants to say.

5. Practice literacy when you’re out and about

I also encourage you to read signs with your child – especially safety-related signage. This can become a natural part of your day when you walk and drive through your community. Reading a stop sign is an important example. The same goes for the street sign or signs that will help your child identify the block where you live. Then there are crosswalk signs, exit and entrance signs. You get the idea.

Putting it all together

To summarize, we can all support literacy development in minimally verbal and non-verbal kids with autism by:

- reading together

- giving them opportunities to interact with a story or other written information in whatever way they’re able

- teaching them to recognize words paired with pictures or symbols

- showing them how we set up symbols in their AAC devices and

- giving them opportunities to type their own words when they’re ready

- reading signage – especially safety signage – when out in the community

I want to thank you again for your question. I hope these tips prove helpful for you, your son and many other readers.

Additional Resources & Tools

- Beaming Health

- Learning Center

Speech Therapy

Augmentative and alternative communication (aac): what to know.

Updated: January 4, 2024 · 7 Minute Read

Reviewed by:

Alex Hurtado

- Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) is a powerful tool that can transform the lives of people who have difficulty with speech.

- AAC is especially important for autistic children, because it gives them a way to communicate without speech.

- AAC can ensure your child always has a way to communicate, allowing for fluctuating communication needs. This helps keep your child safe, promotes autonomy, connection, and meaningful interactions.

- AAC comes in many types and forms, including gestures, facial expressions, writing, drawing, pointing, and high-tech devices. AAC should be implemented in a way that respects and supports your child’s unique communication style.

- 1. What is AAC?

- 2. Why is AAC important for autistic kids?

- 3. Types of AAC

- 4. Will using AAC stop my child from talking?

- 5. How can I use AAC for my child?

- 6. How do I get my child an AAC device?

- 7. All communication is valid

- 8. Your child has something to say

- 9. Conclusion

What is AAC?

Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) is any type of non-spoken communication. Augmentative means adding to someone’s speech. Alternative means that it will be used instead of speech. When you use something other than spoken words to express a thought, feeling, or idea, you’re using AAC! All humans use AAC every day — think about things like gestures, drawing pictures, writing, or facial expressions.

Why is AAC important for autistic kids?

We all have different ways we communicate best. For example, the person writing this article prefers written communication for some things and speaking for other things.

Speech may be difficult for autistic kids for many reasons. AAC gives all people an alternative way to communicate that doesn’t require speech. Autism is a dynamic disability, which means your child’s needs and abilities may fluctuate from day to day or moment to moment. Even neurotypical people sometimes have days when they feel drained and don’t feel up to talking. It is crucial to your child’s safety that they always have a way to communicate.

Types of AAC

Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) can come in many forms. Your child may use AAC for a little while, for their whole lives, or only sometimes. The type of AAC your child uses and the frequency will depend on their unique needs and preferences. Let’s explore the different types of AAC.

AAC can be aided or unaided. Aided AAC requires help from someone or something else, like holding a letter board. Unaided AAC means your child doesn’t need anything but their own body to use it, like sign language.

AAC can also be low-tech or high-tech. Low tech would be options like picture boards. High-tech can be things like speech-generating devices.

- Gestures. This can include pointing, pulling you toward something, making shapes or expressions with their hands or body. Your child may grab your hand and pull you toward the door when they want to go outside, or put the remote in your hand when they want you to turn the TV on. All of these gestures are one way your child communicates.

- Facial expressions. Sad faces, happy faces, all the faces! Facial expressions are often a way to express feelings. Keep in mind, autistic kids may interpret facial expressions differently than neurotypical people. Their own facial expressions may not match what you’d typically expect. For example, you may think your child looks angry, when really they are sad or disappointed.

- Writing and/or typing. Many nonspeaking autistic people prefer to communicate through writing or typing. Even some speaking neurodivergent people prefer written communication. Writing is a less stressful way to communicate because it allows our brains time to process information and create a thoughtful reply. Spoken communication can feel overwhelming, and has a lot of nuance and social cues we may not pick up on. Reading something might make sense when hearing or listening to something doesn’t. But with writing/typing, we can express ourselves at a pace and in a way that feels more intuitive to us. Some autistic children will learn to read or write very young (hyperlexia).

- Drawing. Art can be a powerful tool of communication . Your child may find that they express themselves better sometimes through drawing or creating art than through speech or writing. Many autistic people, like author and scientist Temple Grandin , are visual thinkers. This means the person thinks and learns best in pictures. (Think engineers, artists, and designers.) For an example of this, check out Viktor , a teenage autistic boy who doesn’t speak but communicates through his stunning art.

- Spelling words by pointing to letters. This AAC uses a letter board and the person’s pointing finger or object (like a pencil) to point to the letter the person wants as they spell out words to form sentences. This can be a great option for children with autism who don’t have the fine motor skills to write or type. One example of this communication system is Spelling 2 Communicate (S2C). There is some disagreement about S2C and programs like it. It’s a complex debate, but Not An Autism Mom breaks it down here .

- Pointing to photos, pictures, or written words. One common system used in ABA is PECS (Picture Exchange Communication System). It’s a very rigid system that mostly focuses on requests (“I want”, “I need”, etc.). PCES isn’t a good long term communication solution. Not all picture communication systems are PECS. Visual aids can be extremely helpful for autistic kids, whether they talk a little or a lot. You can use pictures in a variety of ways to help your child communicate. Pictures are a great part of a communication system. Autistic children need more robust communication systems .

- Using an app on an iPad or tablet to communicate. This is one type of high-tech AAC device. Many kinds of AAC devices exist, ranging in cost and complexity. You can purchase some devices online, or you can get them through your child’s insurance provider. There are some PECS-style apps for tablets, but there are also more advanced systems. For many nonverbal adults and kids, their AAC device is a lifeline.

- Using a computer device that “speaks” for them. This is sometimes called a “speech-generating device.” The high-tech device allows the user to input text or select a preset option, and the device will say the word or phrase for them. You may be familiar with the speech-generating device that Dr. Stephen Hawking famously used throughout his career. Speech-generating devices can offer flexibility, opportunity, and robust communication. While there is a slight delay in creating the speech and the computer speaking it, this AAC allows the user to converse with others in real time.

Will using AAC stop my child from talking?

No! In fact, AAC can actually help your child speak more! Your child will continue to develop language and speech. AAC is a tool to support your child’s communication. Children will naturally use speech when they are able. AAC is there to enhance your child’s abilities.

How can I use AAC for my child?

Whether your child is verbal or nonspeaking, autistic or even neurotypical, there are so many ways you can incorporate AAC into your child’s life! Here are some tips:

- Work with an SLP (Speech Language Pathologist) who knows their stuff. We highly recommend working with a qualified and knowledgeable speech therapist . They can help you develop a robust, appropriate communication system for your child. Your child’s personalized communication system should be unique to them. For example, it may look like a combination of pictures, an AAC device, gestures (like sign language), and more. Find a speech therapist who understands and will work with the way your child processes language.

- Create an environment that respects their communication style. It’s important to understand that speakers overtake nonspeakers in conversation and everyday interactions. Society as a whole is biased toward speaking people. This means the burden will likely fall to your child to make themselves heard — which is a big task, especially for a child. It’s vital that you create an environment where your child’s communication style is respected. That means providing space and time for them to listen to and understand what others are saying. Then time for them to think, create, and share a response. It also means acknowledging ALL their communication as valid and important (including behavior).

- Focus on connection and autonomy. The whole point of communication is so your child can express their needs, assert their independence, form connections with people, and have meaningful social interactions. Your child’s AAC should add value to all these areas of their lives. Learning or using AAC should never be about drilling, correction, or getting it right. The focus should be on your child’s strengths, promoting their autonomy, and adding support wherever your child needs it. When adding AAC to your child’s life, always prioritize connection over correction .

How do I get my child an AAC device?

You can get your child an AAC device a few ways.

- Add it to your child’s IEP. If your child has an IEP, you can request that an AAC device be made part of it, and that they always have access to it in school. (Some schools will allow you to take the device home, too.)

- Ask your child’s doctor. You can request an evaluation for an AAC device through your child’s doctor. This requires an evaluation, and your child’s insurance should cover part (or all) of the costs.

- Buy one yourself. Many AAC devices are just apps installed on regular iPads or a tablet. They can be a bit pricey, but getting insurance to pay for AAC devices can take a long time.

Not An Autism Mom’s guide to getting your child an AAC device explains each of those options in more detail. Remember, a speech therapist can help you figure out which AAC device is best for your child and teach them how to use it.

All communication is valid

Unfortunately, many kids are not offered AAC or are denied access to AAC by educators or therapists. Sometimes the adults in a nonverbal child’s life will insist they speak, even if that is not what is most comfortable for them. This can cause a lot of stress on the child, and denies them their right to communication. Jordyn Zimmerman is a nonspeaking autistic person who was denied AAC as a child , but thrived once she had access to it. She’s now on the board of Communication First , a member of President Biden’s committee , and holds a Master’s degree.

Whatever way your child communicates best is worthy of respect. No one should be forcing your child to speak, or denying them access to AAC.

Your child has something to say

We must always presume our children have something to say, even if they cannot speak. The same applies for AAC. We should always presume competence when thinking about AAC. There’s no special training or requirements for a child to learn AAC. Your child doesn’t even have to be a certain age! Assume that your child has something to say and can learn how to share it. Check out AssistiveWare’s guide to presuming competence about AAC for more information.

Whether your child is verbal or nonverbal, understanding and respecting autistic communication is important. AAC can be life-changing, and all people deserve access to it. Using AAC doesn’t make anyone less smart, less worthy, or less capable than anyone else. We all use AAC every day without even realizing it! All ways of communicating are valid and should be respected. For information, check out the deep dives below.

Get our best articles delivered to your inbox each month.

We respect your privacy .

Dive Deeper

Article references.

- ASHA. Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC). Asha.org. Published 2009. https://www.asha.org/public/speech/disorders/aac/

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC). American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Published 2023. https://www.asha.org/NJC/AAC/

- Disability Justice. Abuse and Exploitation of People with Developmental Disabilities | Disability Justice. Disability Justice. Published 2014. https://disabilityjustice.org/justice-denied/abuse-and-exploitation/

- USSAAC. AAC Devices. https://ussaac.org/aac-info/aac-devices/

- USSAAC. Fact Sheet. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://ussaac.org/aac-info/aac-awareness/factsheet/

- Montgomery C. Dear Parents Who Want to Keep Their Nonspeaking Children Safe as They Go Out Into the World. CommunicationFIRST. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://communicationfirst.org/dear-parents-who-want-to-keep-their-nonspeaking-children-safe-as-they-go-out-into-the-world/

- Skenazy L. Severely autistic kids use miracle tool to communicate for first time. Published December 24, 2022. https://nypost.com/2022/12/24/severely-autistic-kids-use-miracle-tool-to-communicate-for-first-time/

- Breglia E. What did you say?! Helping children who are hard to understand. High Hopes. Published April 1, 2020. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.highhopesdubai.com/blog/what-did-you-say-helping-children-who-are-hard-to-understand/

- admin. The positive impact of AAC on Speech and Language Development. High Hopes. Published March 2, 2021. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.highhopesdubai.com/the-positive-impact-of-aac-on-speech-and-language-development/

Alex Hurtado is a freelance writer with nearly 10 years of experience. She has worked in and written for a wide range of industries including education, politics, business, and entertainment, just to name a few.

Written by:

Jeryn Cambrah

Jeryn Cambrah is a neurodivergent writer, artist, poet, author, and mother of an autistic child. She's passionate about equipping parents with the knowledge they need to help their children thrive. Join her in the Infinity Moms Facebook group!

Did you find this article helpful?

Other articles related to speech therapy.

Find our most popular articles in each topic.

For Providers

Parent tips, diagnostic evaluations, aba therapy, schools & ieps, other therapies, our favorites, secure attachment, find child development providers by city.

We have the most comprehensive and up-to-date directory in the country of child development providers.

International Society for Augmentative and Alternative Communication

- About ISAAC

- AAC Awareness

- AAC Emergency Support

- Communication Access

- Conference History

- Publications

- Online Store

- Members Only

- Dis/Ableism in AAC?! What are you talking about?

- “Show Me YOUR AAC Sensitivity” and “I’ll Show You My Voice” – Communication in Health Care Settings

- video on demand thumbnail list test page

- Casting Release for Out of My Mind movie

- Webinar Registration Confirmation

- Information

- » Online Store

- » Books

- » Communication Without Speech

- Communication Without Speech

Communication Without Speech: Augmentative and Alternative Communication Around the World

By Anne Warrick (1998) ISAAC Series: Volume 1

Communication Without Speech is an introduction to AAC. This book answers commonly asked questions and offers practical tips and illustrations. Topics include communication boards, vocabulary selection, assessment and education.

- ISAAC Order Form (PDF, 118 kB)

Pre-payment required PDF downloadable file

Member price : Free to ISAAC Members (see Members Only section) Non-member price : $15 CDN

Communication Without Speech – Traditional Chinese (2010)

Communication without speech – simplified chinese (2010), comunicación sin habla: comunicación augmentativa y alternativa alrededor del mundo.

Escrito por: Anne Warrick (1998)

ISAAC Serie1

Comunicación Sin Habla es una excelente introduccion a la CAA; contiene gran cantidad de cuestiones y de herramientas practicas tales como seleccion de vocabulario, evaluacion, consideraciones educativas y profesionales, elaboracion de tableros, asi mismo incluye excelentes fotografias e ilustraciones.

Comunicacion Sin Habla

PDF downloadable file Pre-payment required

Precio de miembro : Free to ISAAC Members (see Members Only section) Precio de no miembro : $15 CDN

- Affiliated Publications

- Beneath the Surface

- Waves of Words

- Conference Proceedings

Your support provides rehabilitation services to children from all over the United States.

How to Use Books to Promote Communication Skills

Whether or not your child has a disability, reading, and story-telling is a critical way to help them develop speech and language skills.

We use books and story-telling with children to help promote brain development, teach language and emotions, spark curiosity, and encourage children to use their imagination. The book you choose to read is not as important as how you read it to your child. Some books have many words and some books have no words. Feel free to read the books and remember to interact with your child throughout the reading activity.

You can do this by pointing out objects and characters, asking questions about what the characters are doing, describing pictures in the book, calling attention to colors, actions, emotions, animals, or people. This will help your child to develop a robust vocabulary as kids are visual and auditory learners.

Reading every word in the book is an option but not required to engage your child in a language-rich learning experience. Books that include songs, rhymes, and repetitions are a great way to get your child involved in the story. Have them repeat common phrases, sing-a-long, and predict rhymes throughout the story to keep them engaged.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Personalized Early AAC Intervention to Build Language and Literacy Skills: A Case Study of a 3-Year-Old with Complex Communication Needs

Personalized AAC intervention refers to an approach in which intervention is tailored to the individual’s needs and skills, the needs and priorities of the individual’s family and other social environments, the evidence base, and the individual’s response to intervention. This approach is especially relevant to AAC intervention for young children with complex communication needs given their unique constellations of strengths and challenges, and the qualitative and quantitative changes that they experience over time as they develop, as well as the diversity of their families, schools, and communities. This paper provides detailed documentation of personalized AAC intervention over a six-month period for a 3-year-old girl with developmental delay and complex communication needs. The paper describes (1) personalization of multimodal AAC supports to provide this child with the tools to communicate; (2) personalized intervention to build semantic and morphosyntactic skills; and, (3) personalized instruction in literacy skills (i.e., letter-sound correspondences, sound blending, decoding, sight word recognition, reading simple stories, reading comprehension, and encoding skills). Specific goals, instructional materials, and procedures are described; data on speech, language, and literacy outcomes are presented.

The terms, personalized medicine or personalized rehabilitation, refer to a model of service delivery in which interventions are tailored to the individual based on their unique make up, the evidence base, and the individual’s anticipated response to the intervention (e.g., Beukelman, 2016 ; Hamburg & Collins, 2010 ; Nonnekes & Nieuwboer, 2018 ). This personalized approach is focused on ensuring that individuals receive the right intervention at the right time (cf. Hamburg & Collins, 2010 ). This model stands in contrast to a “one size fits all” approach in which all individuals receive the same intervention regardless of their individual needs and skills or the characteristics of their environments ( Beukelman, 2016 ). A personalized approach is particularly relevant to guide decision-making in service delivery for young children who have complex communication needs (e.g., children with autism spectrum disorder, cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, or other developmental disabilities whose natural speech is not sufficient to meet all of their communication needs; Beukelman & Light, 2020 ). These children require augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) to support their communication. AAC is defined as strategies, techniques, and tools used to enhance communication ( ASHA, 2005 ). A vast array of AAC strategies, technologies, and interventions are available that may support children with complex communication needs and decisions must be made as to which of these are the most appropriate fit for each individual child ( Beukelman & Light, 2020 ).

Young children with complex communication needs each have unique constellations of strengths and challenges that impact their response to available AAC supports and interventions (e.g., Romski et al., 2015 ; Romski et al., 2010 ; Kasari et al., 2014 ). They experience significant changes as they learn and grow; their needs and skills show both quantitative and qualitative shifts over time, necessitating modifications to AAC strategies, technologies, and interventions over time to support their development ( Light & McNaughton, 2012 ). Furthermore, children with complex communication needs do not exist in isolation; rather they interact within dynamic social systems including their families, schools, and broader communities. These children and their families are also impacted by the broader societal context that defines legislation, policy, and practices (e.g., Beukelman & Light, 2020 ). Each of these social systems present their own unique constellations of strengths, challenges, values, and priorities that impact the uptake and ultimate success (or failure) of AAC systems and interventions ( Mandak et al., 2017 ). For these reasons, the most effective AAC interventions are personalized so that they take into account the child’s needs and skills; the needs and priorities of the family, school, and broader social context; and the available evidence base ( Granlund et al., 2008 ; Mandak et al., 2017 ). Moreover, the most effective AAC interventions are dynamic; the team carefully monitors the child’s response to intervention and makes modifications as required to reflect changes in the child’s needs and skills as well as those of the environment ( Beukelman & Light, 2020 ).

AAC interventions should support young children with complex communication needs so that they can participate actively in family, school, and community activities; these interventions should prepare them for later involvement in a wide range of meaningful adult activities (e.g., education, employment, volunteer activities, healthcare, and community living; McNaughton & Beukelman, 2010 ). To support such participation, personalized AAC interventions for children may need to target a broad range of individual goals to build communicative competence, foster language development, promote literacy learning, and enhance speech development ( Light & McNaughton, 2014 ). In order to maximize outcomes for young children with complex communication needs, it is critical for practitioners to understand how to personalize AAC supports and interventions to meet targeted goals under a variety of social and environmental conditions at different stages of development.

The field of AAC is still in the early stages of investigating the personalization of AAC intervention. Future research is required to understand how to best implement intervention in an individualized and evidence-based manner ( Beukelman, 2016 ). Detailed case studies are an important first step to identify factors that warrant further investigation. In fact, it has been argued that: “… a scientific discipline without a large number of thoroughly executed case studies is a discipline without systematic production of exemplars, and a discipline without exemplars is an ineffective one” ( Flyvbjerg, 2006 ; p. 219). This paper is intended to contribute to advancing our understanding by providing a comprehensive case study of personalized AAC intervention with a 3-year-old child with complex communication needs over a six-month period (from 38 to 44 months old). The personalized AAC intervention focused on two key domains across this period: (1) building language skills (specifically, semantic and morphosyntactic skills) to support more effective communication; and, (2) teaching literacy skills to facilitate generative communication. The paper provides detailed documentation of intervention goals, AAC supports, and instructional procedures across three phases of intervention over the six-month period and presents data on speech, language, and literacy outcomes. The case study illustrates how we implemented personalized, evidence-based AAC intervention and how we modified intervention based on the child’s response to intervention (RTI; Fuchs & Fuchs, 2006 ). It should be noted that this case study does not provide experimental control and therefore it is not possible to draw a definitive causal relationship between the AAC intervention and the outcomes observed; however, this case provides a source of data to help guide future intervention research.

Background Information

We first met Jessica 1 when she was 35 months old. She was an only child and lived at home with her parents who were very supportive and actively involved with her. When Jessica was 15 months old, her parents had requested an early intervention assessment due to concerns about delays in her acquisition of speech and motor developmental milestones. She qualified for early intervention services at that time and started to receive home-based speech and language intervention, occupational and physical therapy, and vision services. At 26 months, she had a neurodevelopmental evaluation and was diagnosed with global developmental delays with severe expressive language delay, mild receptive language delay, and neuromotor dysfunction. She also had a diagnosis of strabismus-intermittent esotropia (i.e., her eyes turned inward when fixating on objects or activities; Molarte et al., 1991 ) and rotational nystagmus (i.e., involuntary eye movement when the head is rotated; Tibbling, 1969 ). She had been followed by an ophthalmologist since she was 4 months of age and had successful surgery to correct her eye alignment when she was 41 months old (during the course of our intervention). There were no concerns about her hearing. She had passed her newborn hearing screening as well as more formal sound-field testing completed when she was a year old; she responded consistently to spoken input and environmental sounds.

At 35 months of age, Jessica received a comprehensive assessment of her motor, receptive language, expressive communication, and cognitive skills by her early intervention team in preparation for her transition to preschool services. At that time, she demonstrated the ability to walk independently, but did not run or jump. She was able to point with her index finger independent of her thumb and other fingers as well as scribble linear and circular patterns using a fist grasp. She required assistance to hold the paper while coloring, string beads, and fasten her clothing. Her cognitive development was assessed using the Battelle Developmental Inventory, Second Edition (BDI-2 ; Newborg, 2005 ). Her overall cognitive development domain score was 1.67 standard deviations below the mean, qualifying her for preschool services with the diagnosis of developmental delay. Her social and emotional development was also assessed using the BDI-2 . Her score fell within the average range for children with typical development. Per report, she greeted familiar adults spontaneously, enjoyed activities with adults, and responded positively when familiar adults initiated social contact. She separated easily from her parents, used adults for resources, and asked for help when needed. She was able to follow rules within the classroom. She was reported to engage in parallel play with peers and was observed to imitate the play activities of other children. She did not initiate social contact with peers; however, she willingly shared toys with them.

When she was 35 months old, her communication skills were also assessed using the Preschool Language Scale 5 th Edition (PLS-5 ; Zimmerman et al., 2011 ), a language sample, and a phonetic inventory. Her scores on the auditory comprehension portion of the PLS-5 were within the average range for children her age. She was reported to engage in symbolic play, recognize actions in photos, and understand quantitative concepts (e.g., one, some, all). Neither her parents nor her early intervention team reported concerns with Jessica’s receptive language abilities. Her speech production was extremely limited; standardized assessment tools were not administered due to her limited sound repertoire. Her phonetic inventory only included six consonant sounds. Her production of vowels was often distorted and her word shapes were reduplicated open syllables (CV, CVCV). Jessica presented with challenges in saliva management and was often observed to have her tongue out while engaging in activities.

Her expressive communication scores on the PLS-5 fell below the average range for children her age. She recognized photographs and line drawings, but demonstrated difficulty naming objects in photographs due to her expressive limitations. She responded appropriately to bids for social attention and demonstrated referential looking. Her parents and early intervention team had introduced her to signs and a low-tech communication book to augment her communication. She demonstrated a preference for using signs to communicate with her parents and teachers. Her parents and early intervention team reported that she knew approximately 150 signs, including signs for people, animals, actions, objects, descriptors, etc. Her signs were approximations of the required hand shapes, locations, orientations, and movements, but were typically understood by adults who were familiar with her sign inventory. She also had a communication book that contained pictures to support her communication with others, especially those who were unfamiliar with signs. She communicated in single signs (MLU =1.0) with a limited range of concepts. She used conventional gestures to communicate yes (head nod) and no (head shake). Jessica loved reading books with adults and her parents frequently read to her. Her parents had taught her the names of the letters of the alphabet, but not the sounds; she had not received any literacy instruction.

We used the Participation Model (as described in Beukelman & Light, 2020 ) to guide intervention, including consideration of Jessica’s participation patterns and communication needs, her capabilities and skills, and environmental supports and constraints (see Table 1 for a summary of each of these domains when Jessica was 35 months old).

Summary of Jessica’s communication needs and skills at 35 months of age, prior to the personalized AAC intervention.

Personalized AAC Intervention to Build Language and Literacy Skills

When Jessica turned three years old, she transitioned to a community preschool program three half days per week where she received speech and language therapy, physical therapy, and vision services. She was also referred to the Penn State AAC program where she attended an early language group two mornings per week followed by individual instruction for 30 minutes (the focus of this paper); she started these programs at the age of 38 months. Based on the assessment of her needs and skills and environmental supports and constraints, the following areas were identified as priorities for intervention in collaboration with her family and preschool team: (1) enhancing social communication skills with her peers; (2) building her language skills (with a focus on semantic and morphosyntactic skills) to allow her to share her experiences and participate effectively in education; and, (3) learning literacy skills to support generative communication and learning. The first of these skills was addressed during the early language group and is not explicitly discussed in this paper. This paper focuses primarily on her individual sessions that provided literacy instruction with opportunities to enhance language skills integrated into the literacy instruction. The language and literacy intervention was delivered by the third author for the first three months and the fourth author for the following three months, both graduate students in speech language pathology; these students were supervised by a qualified speech language pathologist with expertise in AAC (the second author) while the first author provided consultative support.

As noted earlier, intervention occurred across a six-month period and included three phases, each building on the skills acquired in the prior phase. Data were collected regularly to allow formative evaluation of her performance; modifications to goals, instructional materials, and procedures were made regularly depending on her performance. Thus, intervention was dynamic, reflecting her response to instruction. Table 2 presents a summary of the three intervention phases as well as the language and literacy goals targeted in each phase.

Phases of intervention and targeted language and literacy goals across a six-month period.

Jessica’s parents were actively involved in intervention planning; a parent typically observed the intervention sessions and followed through with many activities in the home environment. Her parents regularly used the following interaction strategies with Jessica to support her communication: providing numerous opportunities for her to communicate, responding to her communication attempts, and expanding on her messages using speech plus signs. They read books regularly with her and talked about the stories, relating them to her experiences.

AAC Supports for Communication

Too often, AAC supports are selected for young children based on clinician preference or the practices of the educational program. In contrast, in keeping with the principles of personalized intervention, we selected and customized AAC supports for Jessica based on her needs, skills, and preferences as well as the values and preferences of her family and preschool program. Most individuals with complex communication needs rely on multiple modes to communicate (e.g., Light et al., 1985 ). Thus, we supported Jessica in the use of multiple modes to enhance her communication across partners and environments, including use of natural speech; gestures and signs; low tech photos, pictures, written words, and letter cards; and mobile technology with an AAC app and keyboard.

The research clearly demonstrates that AAC intervention does not inhibit speech production in individuals with complex communication needs; in fact, the evidence suggests that AAC enhances speech production (e.g., Millar et al., 2006 ; Kasari et al., 2014 ; Romski & Sevcik, 2005 ; Romski et al., 2010 ). Furthermore, based on preliminary observational research of children with complex communication needs, reported by Light and McNaughton (2017) , we believed that literacy learning might be especially facilitative of speech production as the written word would provide a visual support for production of the target spoken word. Thus, we did not consider it to be an “either-or” decision to target natural speech or AAC; rather, as recommended by Oommen and McCarthy (2015) , we worked with Jessica to further her speech development and also provided her with access to AAC (with an emphasis on literacy) to augment her speech and foster her language development. We modeled speech and AAC at all times and responded to all of her speech attempts. Measures of her speech production were collected regularly to determine gains.

Jessica had been introduced to signs during her home-based early intervention program as an infant and toddler; her parents frequently watched the Signing Time videos 2 and signed regularly with her. We continued to emphasize the use of signs with Jessica for a variety of reasons. First and foremost, the research demonstrates the importance of considering preference in selecting AAC supports for individuals with complex communication needs (e.g., van der Meer et al., 2011 ). Consideration of preferences plays a critical role in self-determination and uptake of AAC ( Sigafoos et al., 2005 ). Jessica showed a preference for signs over aided AAC (e.g., low tech photos or pictures; AAC technology). In addition, signs were readily accessible throughout her day and they were easily integrated into all activities (e.g., play, meals, bath, book reading). Furthermore, Jessica was able to approximate the hand shape and movement of the signs without undue effort. She was able to acquire new vocabulary spontaneously by watching others sign throughout her day, using fast mapping to acquire new vocabulary concepts as she needed them (just as children with typical development acquire new spoken words). In addition, Jessica’s parents preferred the spontaneity and accessibility of signs over aided AAC technology; they had spent time developing their own signing skills to support her communication and made an effort to sign with her throughout the day. Jessica and her family had already demonstrated significant uptake and use of signs to enhance her communication. Thus, we built on these individual and family strengths and preferences, encouraging her service providers to sign with her at all times thus modeling language use via speech and sign.

Despite the significant advantages of manual signs as a means to enhance Jessica’s communication, it was clear that this modality was not effective to meet her needs when communicating with peers or adults who were unfamiliar with signs. Therefore, we worked with Jessica and her family to introduce mobile technology with an AAC app to support her communication, especially in the early language group and her preschool program. In keeping with personalized AAC intervention, we reviewed her communication needs and skills and environmental supports and constraints as outlined in Table 1 . As recommended as part of the AAC assessment-intervention process ( Binger et al., 2012 ), based on these factors, we identified the features that Jessica required and selected potential apps that incorporated these features. We then provided opportunities for trial use within her preschool language group and collected data on her accuracy, the effectiveness of her communication, her efficiency, and her preferences. Based on these data, with input from her family and service providers, we introduced her to TouchChat with WordPower 3 42 Basic on a 10.2-inch iPad. The WordPower vocabulary file was used as a foundation; personal vocabulary was added for Jessica as needed (e.g. personal information, family members, preferred activities, classroom themes, etc.). TouchChat with WordPower provided Jessica with access to a range of vocabulary concepts, including a home page of frequently used concepts and 45 main categories of fringe vocabulary plus additional subcategories). Within the WordPower vocabulary file, Jessica had access to numerous displays reflecting various activities (e.g. art, calendar time). The vocabulary concepts were represented by line drawings (i.e. Symbolstix), organized in a grid layout of rows and columns. Each display was organized using a semantic-syntactic organization (see Beukelman & Light, 2020 ) to promote the development of sentence structures. Instruction with the application focused on (1) using a robust vocabulary of semantic concepts (e.g., people, animals, actions, colors, etc.) to express a wide range of messages to fulfill a breadth of communicative functions; and (2) supporting Jessica to communicate phrases and sentences around her areas of interest. For example, when engaging in a classroom activity focused on sports, Jessica used the app to spontaneously communicate, “I like basketball.” As Jessica acquired literacy skills during intervention, she also made use of the TouchChat WordPower phonetic keyboard to type words (see the section on literacy instruction for more details).

We also provided Jessica with access to low tech AAC supports (e.g., photos, line drawings, written words, letter cards) to allow her to participate fully in educational activities and literacy learning and to support communication when manual signs and her AAC technology did not meet her needs. Thus, Jessica had access to multimodal AAC (including natural speech, gestures and signs, low tech AAC, and mobile technology with an AAC app) to enhance her communication and increase her participation across partners and environments. Although these AAC supports were important, simply providing access to these tools was not sufficient to ensure the development of communicative competence ( Light & McNaughton, 2014 ); rather Jessica also needed to develop language and literacy skills to enhance her communication.

Intervention to Support Language Development

When Jessica started to receive AAC services at Penn State when she was 38 months old, she already demonstrated well developed pragmatic skills with familiar adults (e.g., she fulfilled her turns in interactions, maintained the topic, and responded contingently). Therefore, language intervention focused on supporting peer interactions in the early language group, and on fostering semantic and morphosyntactic development to allow her to communicate more complex messages about a wide range of topics and to prepare her to be a full participant in her educational program. In general, we used what is known about the stages of early language development to guide our intervention goals and procedures (see Gerber & Kraat, 1992 ; Beukelman & Light, 2020 ). When Jessica was referred, she was at the stage of early symbolic development. She was an intentional communicator and had acquired more than 100 signs as well as a small number of spoken word approximations; however, she was not yet combining concepts to communicate more complex messages. At this stage, priorities were to continue to build her vocabulary and to extend the complexity of her messages (see Table 2 ).

Language intervention followed a social pragmatic approach, driven by Jessica’s interests, needs, and skills. Some individuals with complex communication needs benefit from explicit instruction to support vocabulary learning ( Reichle & Drager, 2010 ; Wilkinson & McIlvane, 2002 ). However, Jessica demonstrated the ability to use fast-mapping to acquire new language concepts in the context of her daily activities so we built on this individual strength and focused on this approach to intervention, supporting her language development in response to her needs and interests in naturally occurring interactions. Fast mapping is a developmental phenomenon whereby children acquire an initial understanding of a word’s meaning with only minimal exposure; this initial understanding is subsequently fine-tuned with ongoing exposure and use of the word ( Wilkinson & Albert, 2001 ). Throughout the early language group and her individual intervention sessions, Jessica was provided with numerous opportunities to acquire new vocabulary concepts and combine concepts using the following evidence-based strategies: (1) setting up meaningful opportunities for communication; (2) waiting to provide Jessica with the time to express herself; (3) responding to all of her communicative attempts by fulfilling her intent (e.g., requesting information, commenting on experiences, requesting activities); (4) expanding on her message to model more complex language; and, (5) using speech plus AAC (e.g., speech plus signs, speech plus written or typed text) in interactions with her to provide language models that were appropriate given her comprehension skills. The research suggests: (1) the importance of partner responsivity to foster communication early in development (e.g., Warren & Brady, 2007 ); (2) the positive impact of partner models on the expression of longer, more complex messages (e.g., Binger et al., 2008 ; Binger & Light, 2007 ; Binger et al., 2011 ); and (3) the facilitative effect of AAC input from partners on all aspects of language development, including pragmatic, semantic, and morphosyntactic development (e.g., Allen et al., 2017 ; O’Neill et al., 2018 ). Furthermore, the research suggests that children with complex communication needs are frequently pre-empted from opportunities to communicate by partners who dominate the interaction; waiting or expectant delay is a powerful strategy to cue children with complex communication needs to take a turn and to provide them with the time to do so ( Kent-Walsh et al., 2015 ).

We provided Jessica with exposure to a rich language learning environment using speech and AAC to model a wide range of concepts reflecting various semantic roles. In recent years, some researchers have recommended a “universal core vocabulary” approach for beginning communicators (e.g., Geist & Erickson, 2016 ; Project Core, 2020 ); this approach focuses on teaching a very small number of words to beginning communicators. Despite the popularity of the core vocabulary approach with some service providers, we did not restrict Jessica’s vocabulary or specifically emphasize a small number of pre-determined words. There is no empirical evidence to support the effectiveness of this type of core vocabulary approach with beginning communicators as a foundation for robust language learning ( Laubscher & Light, 2020 ). In fact, research suggests that development of a large, diverse vocabulary is a strong predictor of later language and literacy outcomes (e.g., Hemphill & Tivnan, 2008 ; Dickinson et al., 2003 ). Very few of the words included in core vocabulary lists actually reflect the kinds of words that children learn early in language development at the first words stage (cf. Fenson et al., 1994 ). Furthermore, there is no evidence to support restricting expressive vocabulary to a limited set of “core” words; rather, children’s ability to produce word combinations relies heavily on their acquisition of a robust vocabulary including a range of semantic concepts ( Fenson et al., 1994 ). Children with typical development only start to combine language concepts when they have acquired a sufficient number of concepts to communicate a range of semantic relations, that is, once they have acquired approximately 50 concepts ( Laubscher & Light, 2020 ). Thus, vocabulary development is critical to later morphosyntactic development (e.g., Marchman & Bates, 1994 ).

For these reasons, we immersed Jessica in a rich language learning environment that followed principles of language development and regularly introduced new, developmentally-appropriate concepts in response to her interests and environmental demands (e.g., themes in her preschool, concepts from her favorite books). We strove to provide AAC models of everything that was said to her so that she could hear and see language used in communication. Throughout the personalized intervention, language targets were continually revised to reflect Jessica’s learning and her changing needs and skills; in other words, we kept “raising the bar,” targeting more and more complex language concepts and structures.

As summarized in Table 2 , in Phase 1 of the intervention, we started by targeting acquisition of a wide range of single vocabulary concepts representing a variety of semantic roles (e.g., agents, actions, objects, descriptors, locatives, question words, social words) and expression of early emerging two-word combinations (e.g., semantic relations such as agent-action, action-object, descriptor-object; Phase 1). Once Jessica was regularly combining two concepts via speech, signs, and/or aided AAC, we continued to expand her vocabulary introducing new concepts every day in response to her needs and skills; and we used expectant delay to mark opportunities and provide time for her to express longer and more complex sentence structures (Phase 2).

As Jessica built greater fluency combining concepts, we gradually introduced specific function words and morphological and syntactic structures (e.g., use of articles, auxiliaries, conjunctions, etc.) in Phase 3 of intervention. We did not target these concepts in isolation; rather we introduced them in the context of discourse and narratives. As Boenisch and Soto (2015) noted, “…function words become meaningful when used in combination with other words and are typically acquired through discourse” (p. 82). This third phase of language intervention coincided with Jessica’s transition to reading sentences and stories (see the discussion of literacy intervention in the following section). Thus, in addition to modeling language using signs plus speech, we also modeled more complex sentence structures using written text. These models using written language were particularly powerful as they provided a permanent visual support for Jessica to learn specific aspects of morphology (e.g., third person singular -s; articles a or the). The written models were also important at this stage as Jessica’s need for more complex input was beginning to outstrip the sign language skills of her communication partners. Jessica used many of these morphosyntactic structures first when reading and later in her spontaneous interactions.

Language Intervention Outcomes

We collected data on Jessica’s speech and language outcomes using the following techniques: (1) parent and clinician report of vocabulary concepts expressed spontaneously; and (2) transcription and coding of language samples collected each week from informal interactions at the beginning and end of sessions. We analyzed her expression via multiple modalities including natural speech, manual signs, and aided AAC. Table 3 presents data on the language outcomes of intervention. As illustrated in the table, Jessica demonstrated substantial gains in the frequency of her communication turns over the six-month intervention, increasing from a rate of approximately 5–6 turns per minute at baseline to a rate of 10 turns per minute. She also demonstrated substantial gains in the acquisition of vocabulary concepts across the six-month period, acquiring new concepts every day. In addition, she increased her mean length of message from 1.04 (e.g., a single telegraphic sign and/or speech approximation) to multiword sentences.

Language and speech production outcomes of intervention over a six-month period based on 10-min samples at baseline and after 3 and 6 months of intervention.

As is apparent from the examples in Table 3 , her expressive language development across the six-month intervention followed the sequence of typical language development: First she communicated via single words, typically content words (e.g., baby, bubble, mama); next she began to combine semantic concepts such as object + descriptor (baby sad) or action + object (open book); later she started to use longer sentence structures and began to incorporate some structural words including, for example, the use of conjunctions or articles (e.g., Dad has a blue coat). It is interesting to note that very few of the words used spontaneously by Jessica in her early communication messages were on the list of core vocabulary proposed for beginning communicators (e.g., Geist & Erickson, 2016 ; Project Core, 2020 ); rather she utilized a rich array of content words to express herself early in her language development. It was only later in her language development that she began to draw on some of the structural words that are more frequently occurring. As noted earlier, Jessica’s gains in morphosyntax were especially evident as she transitioned to reading sentences and stories where the written text provided a visual model of the structures.

Throughout intervention, Jessica relied on multiple modes to communicate using a combination of signs and natural speech in spontaneous interactions, and also incorporating aided AAC during more structured interactions in the classroom. For example, when she was leaving to go home one day, Jessica communicated the following message about her backpack (which had a picture of a fox, one of her favorite animals): “Fox backpack there” with the word, “fox”, communicated via sign alone, and the words, “backpack there,” communicated via natural speech and sign simultaneously. At the end of a session, she pointed out her dad’s coat and spontaneously communicated, “Dad has a blue coat” using speech and sign simultaneously to express each word. As noted earlier, Jessica also used aided AAC to express herself in more structured interactions. In a discussion of sports in the early language group, she used her AAC app to communicate: I like basketball. (See Table 3 for additional examples.)

Speech Production Outcomes

As noted earlier, throughout intervention, we modeled the use of both speech and AAC (sign and/or aided AAC) in interaction with Jessica and we responded to her communication attempts via any modality. As she developed literacy skills (see the section on literacy intervention for further details), the written text seemed to help to promote speech production. She knew the sounds produced by each letter and the written words provided a visual support marking each sound that should be produced in sequence. Her acquisition of the letters and sounds that underlie literacy coincided with significant increases in the number and range of consonants that she produced. In turn these increases resulted in substantial increases in the intelligibility of her spoken utterances to familiar partners in context. A speech sample at the start of intervention indicated that her phonetic inventory included six consonant sounds /b, p, m, w, d, g/. Her production of vowels was often distorted and her word shapes were reduplicated open syllables (CV, CVCV). In a 10-min sample of interaction, she produced a total of 63 consonants, but 76% of these were either /m/ or /b/. Only 33% of her spoken utterances were intelligible in context (i.e., number of intelligible words out of number of total words). After six-months of language and literacy intervention (when she was 44 months old), she demonstrated significant gains in her speech production. She used a total of 139 consonants in a 10-min sample, including 12 different consonants (only 28% of these were /m/ or /b/ demonstrating much greater diversity of speech sounds). With her increased range of consonants, the intelligibility of her spoken utterances also improved with 95% intelligible for familiar partners in context.

Intervention to Support Literacy Learning

Although language intervention was primarily driven by principles of typical development in determining appropriate goals, we “tampered” with the model of typical development (cf. Gerber & Kraat, 1992 ) and introduced instruction in conventional literacy skills earlier than might usually be expected. We considered the research evidence and Jessica’s and her family’s strengths and priorities in making this decision. The decision was driven by the following considerations. First, literacy skills are of significant importance in society and are fundamental to participation in all aspects of daily life, including education, employment, social interaction, activities of daily living, healthcare, and community living ( Machalicek et al., 2010 ). Literacy skills take on even greater importance for individuals with complex communication needs who have limited speech as they provide access to generative communication. Without literacy skills, children with complex communication needs remain dependent on others to provide and teach picture symbols to represent various vocabulary concepts. With literacy skills, they are able to independently generate any message to express themselves ( Light & McNaughton, 2020 ). Therefore, the development of literacy skills offered Jessica tremendous potential to enhance her communication and support her full participation in educational activities.

In addition, literacy provides a powerful support for language learning. Through literacy, children with complex communication needs have access to a rich vocabulary of concepts (including ones that might not typically be encountered in daily activities), thus furthering their semantic and cognitive development ( Clendon et al., 2014 ). In addition, as noted earlier, written text provides a powerful visual support for learning the morphosyntactic aspects of language. Morphosyntactic skills are especially vulnerable in children with complex communication needs. The research shows that children who rely on AAC typically communicate in face-to-face interactions using telegraphic forms (e.g., Light et al., 1985 ). They often co-construct messages with their communication partners with a focus on the expression of meaning and communicative intent with limited attention to the structural aspects of language. In contrast, written language provides a clear visual representation of the structural aspects of language. Light and McNaughton (2017) have argued that the visual support provided by written text can be leveraged to support morphosyntactic learning by children with complex communication needs. Furthermore, literacy skills may also be beneficial for children with complex communication needs who experience significant challenges in speech production as written language makes explicit the individual speech sounds and their sequence in words through application of letter sound knowledge to the orthographic sequence of letters ( Light & McNaughton, 2017 ). Finally, literacy skills were a priority for Jessica’s parents. These skills are highly valued within society and the acquisition of literacy skills may significantly impact others’ perceptions of a child’s competence, thereby positively impacting learning opportunities and experiences ( Stanovich, 2008 ).

Overall, our approach to literacy instruction followed the evidence-based principles laid out by Light and McNaughton (2009) with the first phase of instruction targeting the foundations for literacy skills (i.e., basic skills such as letter sound correspondences and sound blending) as well as sight word instruction and shared reading to demonstrate the power of literacy (see Table 2 ). As soon as Jessica acquired approximately 6–7 letter sound correspondences, she transitioned to Phase 2 of instruction and we introduced her to decoding (i.e., the skills to look at the letters in a word in sequence, recall their sounds, and blend the sounds together to read the target word). We also continued instruction in the remaining letter sound correspondences, shared reading, and sight word recognition (specifically of frequently-occurring, irregular words and high interest complex words). Once Jessica was consistently applying decoding skills and once she had learned to recognize a corpus of frequently occurring sight words, we focused on teaching her to read and understand simple stories. We also introduced her to keyboarding skills, phoneme segmentation skills, and early encoding /writing skills (Phase 3).

Overall literacy intervention integrated direct instruction in basic skills (e.g., letter sound correspondences, phonological awareness skills, decoding, and encoding skills) with numerous opportunities to apply these skills in meaningful literacy experiences such as shared book reading and shared story writing ( Light & McNaughton, 2020 ). Direct instruction followed the procedures described by Light and McNaughton (2009) : (1) we modeled the target skill; (2) we provided guided practice in the skill (i.e., provided prompting support to ensure Jessica’s success); and (3) we provided independent practice in the skill with feedback for each response. When Jessica successfully demonstrated the target skill, we provided positive encouragement. When she demonstrated an incorrect response, we provided corrective feedback, modeling the correct response for her and providing her with guided practice in the skill. Over time, instructional supports were faded based on Jessica’s learning.

Key instructional materials were personalized to reflect Jessica’s interests and experiences. This personalization was critical to ensure her motivation and to support her understanding based on her experiences and world knowledge. For example, target words and books were personalized to include her family, her daily experiences, and her interest in animals. Instructional tasks and procedures were also adapted to accommodate Jessica’s needs. Specifically, as described by Light and McNaughton (2009) , we adapted instruction to allow her to participate using a range of modalities (e.g., natural speech; signs; photos, line drawings, written words, or letter cards; AAC technology). We provided support initially to help her re-auditorize written letters or words to speech (i.e., translating the letters, c-a-t, to the spoken word). The following sections describe these adaptations in more detail for each of the literacy skills targeted as well as the outcomes of instruction.

Letter-Sound Correspondences

At baseline, prior to instruction, Jessica knew the names of many letters but she did not consistently identify any of their sounds. Since it is knowledge of the sounds (not the names) of letters that is required for reading and writing, we focused on teaching letter sound correspondences, introducing letters and their sounds one at a time, until she acquired all of the individual letter sounds. Digraphs (e.g., th, sh) are typically introduced later in instruction. We started by teaching lower case rather than upper case letters as the vast majority of words in books include lower, not upper case letters. We taught upper case as appropriate in context (e.g., the first letter of her name or other proper names). We did not teach the letter sounds in alphabetical order; rather we taught them in the sequence recommended by Light and McNaughton (2009) , teaching those letter sounds that are most frequently occurring in children’s books first so that Jessica would be able to read more words earlier. When introducing new letter sounds, we separated ones that were visually and auditorily similar (e.g., m and n). Since Jessica was not able to reliably say the letter sounds, we adapted instruction to support her participation. Specifically, we said the letter sound and Jessica found the appropriate letter from a field of 4 or more letter cards ( Light & McNaughton, 2009 ). Once Jessica had learned to consistently identify 15 letters when presented with their sounds, we introduced her to a hard copy keyboard initially (and later a keyboard on the iPad) so that she could practice locating the letters on the keyboard for spelling and writing tasks. We used a standard QWERTY keyboard since Jessica had sufficient motor skills to select with an index finger; this keyboard is most frequently used in society and learning this keyboard would provide her with greatest flexibility across educational, vocational, and community environments.

Figure 1 presents data on Jessica’s acquisition of letter sound correspondences during the first two phases of intervention (Months 1–3). As the graph illustrates, she required a total of 22 instructional sessions (approximately 8 minutes each) to learn all letters and sounds (a total of approximately 170 minutes of instruction). Initially, she required several sessions to learn a single letter sound correspondence (e.g., 6 sessions to learn a; 2 sessions to learn m; 3 sessions to learn t). Once she had learned the first three letter sound correspondences, her rate of learning accelerated rapidly so that we consistently introduced two new letters each session.

Number of letter sound correspondences successfully acquired with >80% accuracy across baseline and intervention (Months 1–3 of intervention; 38–41 months old)

Sound Blending

Learning to read depends not just on letter sound knowledge but also on the phonological awareness skill of sound blending (i.e., blending sounds produced slowly to form words). Since Jessica was not able to reliably blend sounds and say words orally, we adapted instruction to support her participation. We said the letter sounds of a word slowly in sequence and then Jessica had to blend the sounds together in her head, determine the word, and then sign the word or indicate the photo of the target word from a field of 4 or more photos ( Light & McNaughton, 2009 ). At baseline, prior to intervention, Jessica performed at chance levels; she had not yet learned to hold the sounds in her working memory and blend them together to determine the target word. For the most part, she demonstrated steady gains and required a total of 10 instructional sessions during Months 1 and 2 of intervention (approximately 80 minutes total; 8 minutes for each session) to learn this phonological awareness skill (see Figure 2 ).

Percent accuracy with sound blending across baseline and intervention (Months 1–2 of intervention; 38–40 months old)

Sight Word Recognition and Shared Reading

In order to build motivation and ensure that Jessica recognized the power of literacy learning from the outset, we introduced her to approximately 12 high interest words early on which she learned to recognize by sight (before she learned to decode). These high interest words included: family members (i.e., her name, mom, dad), animals which were of great interest to her (i.e., cat, dog, fox, bear), and favorite activities (i.e., book, bike, cook, swing, rock). As with letter-sound instruction, we introduced these words to Jessica one at a time, over time. Once she had learned to recognize these words by sight, we introduced her to additional high interest sight words (e.g., sign, ball, jump, cookie, bubbles, snack, puzzle, juice, duck, cup).

We incorporated these words into simple books so that Jessica could participate in shared reading activities. Each page of the book included a photo of interest to her with a simple sentence typed under the photo; the high interest sight words were highlighted as they occurred. Initially, only a single word was highlighted on each page (often at the end of the sentence). Over time, as Jessica increased her sight word recognition skills and learned to decode words, additional words were targeted in each sentence (e.g., Jessica likes to cook with dad). A familiar adult (e.g., graduate student, parent) read the sentence to Jessica pausing at each of the highlighted words and waiting for Jessica to read the word and then sign it, say it, or point to a picture of the concept. These shared reading activities were her favorite instructional activities; they clearly demonstrated the power and joy of literacy learning.

Decoding Skills

As soon as Jessica had acquired 6–7 letter sounds and was able to reliably blend sounds, we taught her to decode regular words (e.g., CVC, VC, CV words). Decoding skills are essential to literacy learning for they allow children to attack new words that they have not been taught ( Ahlgrim-Delzell et al., 2016 ; Fallon et al., 2004 ). It is challenging to learn to decode. The child must look at the letters in sequence, recall the sound for each letter, hold these sounds in working memory, and then blend them together to determine the word. As Jessica acquired new letters and sounds, new words that included these letter sounds were regularly added to decoding instruction. Thus the task became more challenging over time.

Decoding instruction followed the adapted procedures described by Light and McNaughton (2009) : We provided Jessica with four photos or pictures, each representing a different CVC word; we then provided her with the written word; initially we provided her with guided practice and helped her to point to each of the letters in sequence and say the letter sound; she then blended the sounds together and selected the photo that represented the word. Over time, we faded our support so that Jessica was expected to look at the letters in sequence, retrieve their sounds in her head, and blend them together independently (see Light & McNaughton, 2009 for further details). We selected the foils carefully so that, for the most part, each of the words represented by the photos differed from the target by a single letter-sound (e.g., if the target word was bug, the foils might be rug, bag, and bun); thus, we ensured that Jessica was decoding the entire word and not relying on recognizing the first letter(s). As noted by Mandak et al. (2018) , there are various adaptations that can be used to support the participation of children with complex communication needs in literacy instruction (e.g., saying the target word and asking the child to choose from a field of four or more written words; providing a written word and asking the child to choose the picture that the word represents from a field of four or more, etc.). We specifically chose an approach that required Jessica to re-code the word phonologically from its written form since this is a process that is typically challenging for children with complex communication needs (e.g., Dahlgren Sandberg, 2002 ). As Jessica learned to decode words, regular decodable words were also targeted in her shared reading books along with the sight words that she had acquired.

Figure 3 presents data on Jessica’s performance independently decoding single words. At baseline, as expected with most 3-year-olds, Jessica was not able to decode words. She required 25 instructional sessions from Months 2–6 (a total of approximately 300 minutes of instruction, approximately 10–12 minutes of instruction per session) to learn to decode single words and apply these word attack skills to new words. Her performance demonstrated some variability from session to session since she was expected to decode words including a steadily increasing range of letters and sounds over time.