We use cookies to enhance our website for you. Proceed if you agree to this policy or learn more about it.

- Essay Database >

- Essays Samples >

- Essay Types >

- Case Study Example

Philosophy Case Studies Samples For Students

80 samples of this type

Do you feel the need to examine some previously written Case Studies on Philosophy before you get down to writing an own piece? In this open-access database of Philosophy Case Study examples, you are granted an exciting opportunity to explore meaningful topics, content structuring techniques, text flow, formatting styles, and other academically acclaimed writing practices. Adopting them while composing your own Philosophy Case Study will definitely allow you to finish the piece faster.

Presenting superb samples isn't the only way our free essays service can aid students in their writing endeavors – our authors can also create from point zero a fully customized Case Study on Philosophy that would make a solid foundation for your own academic work.

Good Case Study About Japans Changing Culture

Section 1: provide a general description of the company., m.11 case study samples, kant case study example.

Don't waste your time searching for a sample.

Get your case study done by professional writers!

Just from $10/page

Case Study On Marketing Concept

Case study on initech vs the coffee bean.

Modern day managers who care less about employee motivation and satisfaction do so at the business’s peril. It is imperative that the business managers put in place strategies to maintain low staff turnover by placing value not only on clients but also on the employees (Grant, 1984). Fullerton and Toossi (2001) assert that doing this assures the business of continuity and gives it a competitive edge over its competitors. The case of a Peter Gibbons working for Initech exemplifies this issue by contrasting the working conditions at Initech to those at Coffee Beans.

Peter’s achievement orientation

The mens warehouse case study example, ethical issue and core stakeholders case study, the technicians get the feedback through the inspection of their own work case study, freedom vs determination case study.

The issue of free will (freedom) versus determination has been around for a long time. It has continued to be a puzzle for philosophers ever since. Philosophers face such trouble with the issue of freedom versus determination because without freedom morality would be unheard of among the humankind; and such there would be no good, no wrong, or evil. All of humankind’s behavior would be priory determined, and; therefore, man would be left with no choice or creativity (Fischer 1994).

Introduction

Write by example of this transformation of general electric by jack welch. case study case study.

Executive Summary

Good Case Study About The Italian Tax Mores

History, circumstances, ethical issues, philosophy of religion case study sample.

In the contemporary world, the concept of religion is more specialized and diverse among varied religious affiliation. Therefore, various forums for philosophical discussion have come up with dissimilar ideas centered on religion. The intent of this thesis is to respond to a series of questions concerning religion.

- What is the doctrine of divine simplicity?

The doctrine of divine simplicity God is simply outlined as a supreme being that lacks distinct metaphysical parts, constituents, or properties. Rather, God is given special attributes such as holiness, goodness, merciful, etc. Therefore, God is divine hence can only be attributed to his greatness, power, and wisdom.

- Can we make sense of the idea that perfect goodness is identical to perfect power?

Hospitality customer service case study sample, part i: questions.

Question 1: The four core tools for service excellence delivery include taking care of the employee needs simultaneously. This could include provision of good and right training for employees, providing employees with a good compensation that is proportionate with the work done, retention of employees through provision of job security and lastly hiring the right employees to do the right job based on their skills. All these components must be implemented simultaneously. These could be illustrated as below:

Question 2: A service philosophy is the

Case study on customer service and sales policy, good axiology, epistemology, and ontology and their importance to organizational communication name case study example, culture sensitivity: example case study by an expert writer to follow, international management in an asian context: business life and management in china.

Introduction Globalization has complicated the management process. As such, for one to be an effective manager, that individual needs to understand the global context of the management process. Fundamentally, one needs to appreciate the role of culture in the management process (Luthans & Doh, 2014). As such, the paper shall examine several features of the Chinese society and evaluate the ways they will affect the management process.

Comparative Analysis On Mitsui And Samsung Groups Case Study Example

Whole foods market 2007 case study sample, good example of case study on employment law, example of ethical analysis of dilemma 4 using utilitarianism principles case study, free case study about the ethical model.

[First Last Name]

Business Ethics [Number]

Example of charles manson case study, example of mr paulsons store case study.

- What is the compensation package for full-time sales force at the stores? Classify by kind of compensation.

Sample Case Study On Ethical Consultants

Example of ethical theory and its application case study.

There have been increased awareness on ethical business and environmental degradation within the recent decades. Just like human, organizations are held responsible for their actions. This paper explores the ethical theories and concepts as they apply to the case study of the OK Tedi Copper Mine. The new CEO of BHP, Paul Anderson had just come in office and faced with the task of managing what people had referred to as the world’s greatest ongoing “environmental disaster” (Velasquez, 2012).

Utilitarianism

Drug development case study case study examples, example of case study on role of the manager and the impact of organizational theories on managers.

Management is a task that brings together the various aspects of the roles of managers. In particular, the tasks performed by managers in organizations are quite huge because it is essential that a person is courageous enough to deal with the various views and characteristics of people that make up the workforce of the organization (Rice, 2013). Therefore, the analysis of the effects of the management theories on the management roles of managers is a timely analysis that requires adequate time and resources for the investigation of the various aspects of the subject.

Free Case Study On Buad 3000 Career Development II

Discovery project part 3: merging the brands.

Sections 1 and 2: Company Focus and Merging the Brands 60 Points total--50 points for content; 10 for typos and grammar

Late Assignments Are Not Accepted

Proper case study example about stakeholders, analysis of the documentary food, inc. through the lens of ethical theories and ideas, real-time satellite imaging: example case study by an expert writer to follow, brief summary, free case study about methods of communication, influencing individuals and groups, good case study on nucor, free acorn house restaurant case study example, ethical, legal and moral dilemma case study example, internal control auditing case study example, internal control auditing.

Integrity and ethical values Integrity and ethical values can be seen to be well present in XYZ. All the staff members are well cooperative and there is an atmosphere of trust and reliability among the staff notably among Tim, Bill and Day. Everybody has a clear perspective of the ethical values and follow the company systems properly. There is a moderate control environment on the basis of integrity and ethical values among the members of XYZ.

Commitment to competence

Free southwest case analysis case study sample, case study on executive summaries and critiques, executive summary, free case study on brand value, case study on developing chinks in the vaunted toyota way, case study on men's wearhouse, case study on death penalty, free case study on executive summary2.

Table of Contents

Introduction.2

Mission and Goals2 Situation Analysis3 Corporate Level Strategy..10 Business Level Strategy11

Example Of Case Study On Gm Eds

The british phone hacking scandal case study examples, good ethical analysis case study example, gillette company leadership for change: a top-quality case study for your inspiration, first step 3.

Decision maker and responsibilities 3 Issues and significance 4 Reasoning for current issue and decision maker involvement 5 Timeline and urgency 6 Exhibits analyze 7 Second Step: Analyzing the Case 8 Defining the issue 8 Analyzing the data of the case 8 Genearting alternatives 8 Selecting decision criteria 9 Analyzing and evaluating alternatives 10 Selecting the preferred alternative 10 Developing an action/implementation of plan 10

References 12

Good foundations of education: case study outline case study example, an assignment submitted by, toxicology: animals in research case study template for faster writing, good case study on fetal abnormality, sample case study on sandel’s account of what he takes to be a morally significant difference between a “lie” and a “misleading truth”, free case study about diagnosing managerial characteristics.

(Name of Author)

The exercise is designed to help one manage other people more effectively by putting in practice the diagnosis of the differences in their styles, values, and attitudes. To complete the exercise, an analysis of four successful managers with different values, interpersonal and change orientations and learning styles was done. The managers were then ranked in descending order in the following categories; emotional intelligence, values maturity, tolerance of ambiguity, and core self-valuation.

Emotional Intelligence

Analyzing mary’s case using the social learning theory case studies example, case study on simon sinek golden circle model, a comparative study of kfc in china and lincoln, uk case study example, background of the study, comparing mrp and kanban case study example.

Material Requirements Planning (MRP) and Kanban control systems are one of the most prominent production planning and inventory control systems of today. These systems are the most popular implementations of push and pull strategies respectively. Speaking of MRP, it is a material control system that tries to maintain adequate inventory levels to ensure that the required materials are available, when needed. MRP is used where there are multiple items with complex bills of materials. It is not suited for continuous processes that are tightly linked.

The major objective of an MRP system is to simultaneously:

Case study on abnormal psychology: charles manson, good case study on case #5 chipotle, the essence of the firm/industry problem, lean manufacuring class case study examples, question one, example of customer-based production case study, implement lean elements on project management, general electric under jack welch case study sample.

Password recovery email has been sent to [email protected]

Use your new password to log in

You are not register!

By clicking Register, you agree to our Terms of Service and that you have read our Privacy Policy .

Now you can download documents directly to your device!

Check your email! An email with your password has already been sent to you! Now you can download documents directly to your device.

or Use the QR code to Save this Paper to Your Phone

The sample is NOT original!

Short on a deadline?

Don't waste time. Get help with 11% off using code - GETWOWED

No, thanks! I'm fine with missing my deadline

- Free Samples

- Premium Essays

- Editing Services Editing Proofreading Rewriting

- Extra Tools Essay Topic Generator Thesis Generator Citation Generator GPA Calculator Study Guides Donate Paper

- Essay Writing Help

- About Us About Us Testimonials FAQ

- Philosophy Case Study

- Samples List

An case study examples on philosophy is a prosaic composition of a small volume and free composition, expressing individual impressions and thoughts on a specific occasion or issue and obviously not claiming a definitive or exhaustive interpretation of the subject.

Some signs of philosophy case study:

- the presence of a specific topic or question. A work devoted to the analysis of a wide range of problems in biology, by definition, cannot be performed in the genre of philosophy case study topic.

- The case study expresses individual impressions and thoughts on a specific occasion or issue, in this case, on philosophy and does not knowingly pretend to a definitive or exhaustive interpretation of the subject.

- As a rule, an essay suggests a new, subjectively colored word about something, such a work may have a philosophical, historical, biographical, journalistic, literary, critical, popular scientific or purely fiction character.

- in the content of an case study samples on philosophy , first of all, the author’s personality is assessed - his worldview, thoughts and feelings.

The goal of an case study in philosophy is to develop such skills as independent creative thinking and writing out your own thoughts.

Writing an case study is extremely useful, because it allows the author to learn to clearly and correctly formulate thoughts, structure information, use basic concepts, highlight causal relationships, illustrate experience with relevant examples, and substantiate his conclusions.

- Studentshare

Examples List on Philosophy Case Study

- TERMS & CONDITIONS

- PRIVACY POLICY

- COOKIES POLICY

PLATO is pleased to launch a student ethics case writing project. Any middle or high school student in the United States can participate.

The goal is to create an open-access library of case studies focusing on ethical dilemmas relevant to middle and high school students that can be used in middle and high school classrooms and in other ethics forums.

Accepted cases will be published on PLATO’s website, with credit to the writers, and students will receive $100 for each published case. A team of graduate students will review and edit the cases before publication.

All published cases become the property of PLATO.

Description of Ethics Cases

Guidelines: Each case should focus on an ethical issue, current or perennial, relevant to middle and/or high school students. The case must consider the ethical issue from at least two viewpoints presented fully and generously, so that the complexity of the case is made clear. If you have suggestions for study questions for students analyzing the case, please include them.

Length: 300-500 words

Sample case: “ Standing for the National Anthem .”

Authorship: Cases can be written by individuals or a group of students (all contributors will be credited).

Judging Criteria

All submissions will be anonymously reviewed by a committee of five judges according to the following criteria:

- Does the case clearly articulate the ethical issue and its ethical complications?

- Does the case explicitly consider at least two viewpoints in a balanced way?

- Is the case well-written and clearly organized?

DEADLINE: Submit cases online by completing the form to the right (or below on mobile), by 5 pm Monday, August 14, 2023.

Writers of accepted cases will be notified in September 2023.

Submit Your Case Here

Upload Case File:

Connect With Us!

Stay Informed

PLATO is part of a global UNESCO network that encourages children to participate in philosophical inquiry. As a partner in the UNESCO Chair on the Practice of Philosophy with Children, based at the Université de Nantes in France, PLATO is connected to other educational leaders around the world.

If you would like to change or adapt any of PLATO's work for public use, please feel free to contact us for permission at [email protected] .

McCombs School of Business

- Español ( Spanish )

Videos Concepts Unwrapped View All 36 short illustrated videos explain behavioral ethics concepts and basic ethics principles. Concepts Unwrapped: Sports Edition View All 10 short videos introduce athletes to behavioral ethics concepts. Ethics Defined (Glossary) View All 58 animated videos - 1 to 2 minutes each - define key ethics terms and concepts. Ethics in Focus View All One-of-a-kind videos highlight the ethical aspects of current and historical subjects. Giving Voice To Values View All Eight short videos present the 7 principles of values-driven leadership from Gentile's Giving Voice to Values. In It To Win View All A documentary and six short videos reveal the behavioral ethics biases in super-lobbyist Jack Abramoff's story. Scandals Illustrated View All 30 videos - one minute each - introduce newsworthy scandals with ethical insights and case studies. Video Series

Case Studies UT Star Icon

Case Studies

More than 70 cases pair ethics concepts with real world situations. From journalism, performing arts, and scientific research to sports, law, and business, these case studies explore current and historic ethical dilemmas, their motivating biases, and their consequences. Each case includes discussion questions, related videos, and a bibliography.

A Million Little Pieces

James Frey’s popular memoir stirred controversy and media attention after it was revealed to contain numerous exaggerations and fabrications.

Abramoff: Lobbying Congress

Super-lobbyist Abramoff was caught in a scheme to lobby against his own clients. Was a corrupt individual or a corrupt system – or both – to blame?

Apple Suppliers & Labor Practices

Is tech company Apple, Inc. ethically obligated to oversee the questionable working conditions of other companies further down their supply chain?

Approaching the Presidency: Roosevelt & Taft

Some presidents view their responsibilities in strictly legal terms, others according to duty. Roosevelt and Taft took two extreme approaches.

Appropriating “Hope”

Fairey’s portrait of Barack Obama raised debate over the extent to which an artist can use and modify another’s artistic work, yet still call it one’s own.

Arctic Offshore Drilling

Competing groups frame the debate over oil drilling off Alaska’s coast in varying ways depending on their environmental and economic interests.

Banning Burkas: Freedom or Discrimination?

The French law banning women from wearing burkas in public sparked debate about discrimination and freedom of religion.

Birthing Vaccine Skepticism

Wakefield published an article riddled with inaccuracies and conflicts of interest that created significant vaccine hesitancy regarding the MMR vaccine.

Blurred Lines of Copyright

Marvin Gaye’s Estate won a lawsuit against Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams for the hit song “Blurred Lines,” which had a similar feel to one of his songs.

Bullfighting: Art or Not?

Bullfighting has been a prominent cultural and artistic event for centuries, but in recent decades it has faced increasing criticism for animal rights’ abuse.

Buying Green: Consumer Behavior

Do purchasing green products, such as organic foods and electric cars, give consumers the moral license to indulge in unethical behavior?

Cadavers in Car Safety Research

Engineers at Heidelberg University insist that the use of human cadavers in car safety research is ethical because their research can save lives.

Cardinals’ Computer Hacking

St. Louis Cardinals scouting director Chris Correa hacked into the Houston Astros’ webmail system, leading to legal repercussions and a lifetime ban from MLB.

Cheating: Atlanta’s School Scandal

Teachers and administrators at Parks Middle School adjust struggling students’ test scores in an effort to save their school from closure.

Cheating: Sign-Stealing in MLB

The Houston Astros’ sign-stealing scheme rocked the baseball world, leading to a game-changing MLB investigation and fallout.

Cheating: UNC’s Academic Fraud

UNC’s academic fraud scandal uncovered an 18-year scheme of unchecked coursework and fraudulent classes that enabled student-athletes to play sports.

Cheney v. U.S. District Court

A controversial case focuses on Justice Scalia’s personal friendship with Vice President Cheney and the possible conflict of interest it poses to the case.

Christina Fallin: “Appropriate Culturation?”

After Fallin posted a picture of herself wearing a Plain’s headdress on social media, uproar emerged over cultural appropriation and Fallin’s intentions.

Climate Change & the Paris Deal

While climate change poses many abstract problems, the actions (or inactions) of today’s populations will have tangible effects on future generations.

Cover-Up on Campus

While the Baylor University football team was winning on the field, university officials failed to take action when allegations of sexual assault by student athletes emerged.

Covering Female Athletes

Sports Illustrated stirs controversy when their cover photo of an Olympic skier seems to focus more on her physical appearance than her athletic abilities.

Covering Yourself? Journalists and the Bowl Championship

Can news outlets covering the Bowl Championship Series fairly report sports news if their own polls were used to create the news?

Cyber Harassment

After a student defames a middle school teacher on social media, the teacher confronts the student in class and posts a video of the confrontation online.

Defending Freedom of Tweets?

Running back Rashard Mendenhall receives backlash from fans after criticizing the celebration of the assassination of Osama Bin Laden in a tweet.

Dennis Kozlowski: Living Large

Dennis Kozlowski was an effective leader for Tyco in his first few years as CEO, but eventually faced criminal charges over his use of company assets.

Digital Downloads

File-sharing program Napster sparked debate over the legal and ethical dimensions of downloading unauthorized copies of copyrighted music.

Dr. V’s Magical Putter

Journalist Caleb Hannan outed Dr. V as a trans woman, sparking debate over the ethics of Hannan’s reporting, as well its role in Dr. V’s suicide.

East Germany’s Doping Machine

From 1968 to the late 1980s, East Germany (GDR) doped some 9,000 athletes to gain success in international athletic competitions despite being aware of the unfortunate side effects.

Ebola & American Intervention

Did the dispatch of U.S. military units to Liberia to aid in humanitarian relief during the Ebola epidemic help or hinder the process?

Edward Snowden: Traitor or Hero?

Was Edward Snowden’s release of confidential government documents ethically justifiable?

Ethical Pitfalls in Action

Why do good people do bad things? Behavioral ethics is the science of moral decision-making, which explores why and how people make the ethical (and unethical) decisions that they do.

Ethical Use of Home DNA Testing

The rising popularity of at-home DNA testing kits raises questions about privacy and consumer rights.

Flying the Confederate Flag

A heated debate ensues over whether or not the Confederate flag should be removed from the South Carolina State House grounds.

Freedom of Speech on Campus

In the wake of racially motivated offenses, student protests sparked debate over the roles of free speech, deliberation, and tolerance on campus.

Freedom vs. Duty in Clinical Social Work

What should social workers do when their personal values come in conflict with the clients they are meant to serve?

Full Disclosure: Manipulating Donors

When an intern witnesses a donor making a large gift to a non-profit organization under misleading circumstances, she struggles with what to do.

Gaming the System: The VA Scandal

The Veterans Administration’s incentives were meant to spur more efficient and productive healthcare, but not all administrators complied as intended.

German Police Battalion 101

During the Holocaust, ordinary Germans became willing killers even though they could have opted out from murdering their Jewish neighbors.

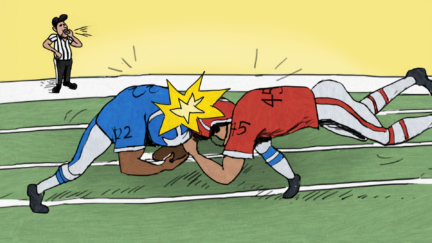

Head Injuries & American Football

Many studies have linked traumatic brain injuries and related conditions to American football, creating controversy around the safety of the sport.

Head Injuries & the NFL

American football is a rough and dangerous game and its impact on the players’ brain health has sparked a hotly contested debate.

Healthcare Obligations: Personal vs. Institutional

A medical doctor must make a difficult decision when informing patients of the effectiveness of flu shots while upholding institutional recommendations.

High Stakes Testing

In the wake of the No Child Left Behind Act, parents, teachers, and school administrators take different positions on how to assess student achievement.

In-FUR-mercials: Advertising & Adoption

When the Lied Animal Shelter faces a spike in animal intake, an advertising agency uses its moral imagination to increase pet adoptions.

Krogh & the Watergate Scandal

Egil Krogh was a young lawyer working for the Nixon Administration whose ethics faded from view when asked to play a part in the Watergate break-in.

Limbaugh on Drug Addiction

Radio talk show host Rush Limbaugh argued that drug abuse was a choice, not a disease. He later became addicted to painkillers.

U.S. Olympic swimmer Ryan Lochte’s “over-exaggeration” of an incident at the 2016 Rio Olympics led to very real consequences.

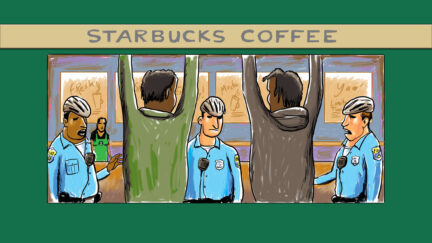

Meet Me at Starbucks

Two black men were arrested after an employee called the police on them, prompting Starbucks to implement “racial-bias” training across all its stores.

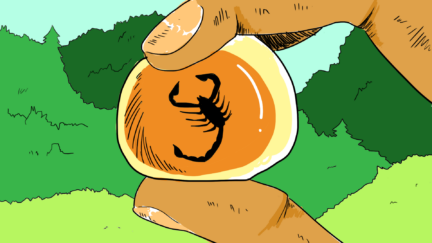

Myanmar Amber

Buying amber could potentially fund an ethnic civil war, but refraining allows collectors to acquire important specimens that could be used for research.

Negotiating Bankruptcy

Bankruptcy lawyer Gellene successfully represented a mining company during a major reorganization, but failed to disclose potential conflicts of interest.

Pao & Gender Bias

Ellen Pao stirred debate in the venture capital and tech industries when she filed a lawsuit against her employer on grounds of gender discrimination.

Pardoning Nixon

One month after Richard Nixon resigned from the presidency, Gerald Ford made the controversial decision to issue Nixon a full pardon.

Patient Autonomy & Informed Consent

Nursing staff and family members struggle with informed consent when taking care of a patient who has been deemed legally incompetent.

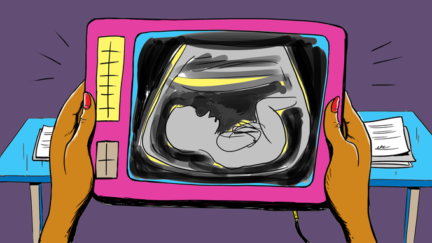

Prenatal Diagnosis & Parental Choice

Debate has emerged over the ethics of prenatal diagnosis and reproductive freedom in instances where testing has revealed genetic abnormalities.

Reporting on Robin Williams

After Robin Williams took his own life, news media covered the story in great detail, leading many to argue that such reporting violated the family’s privacy.

Responding to Child Migration

An influx of children migrants posed logistical and ethical dilemmas for U.S. authorities while intensifying ongoing debate about immigration.

Retracting Research: The Case of Chandok v. Klessig

A researcher makes the difficult decision to retract a published, peer-reviewed article after the original research results cannot be reproduced.

Sacking Social Media in College Sports

In the wake of questionable social media use by college athletes, the head coach at University of South Carolina bans his players from using Twitter.

Selling Enron

Following the deregulation of electricity markets in California, private energy company Enron profited greatly, but at a dire cost.

Snyder v. Phelps

Freedom of speech was put on trial in a case involving the Westboro Baptist Church and their protesting at the funeral of U.S. Marine Matthew Snyder.

Something Fishy at the Paralympics

Rampant cheating has plagued the Paralympics over the years, compromising the credibility and sportsmanship of Paralympian athletes.

Sports Blogs: The Wild West of Sports Journalism?

Deadspin pays an anonymous source for information related to NFL star Brett Favre, sparking debate over the ethics of “checkbook journalism.”

Stangl & the Holocaust

Franz Stangl was the most effective Nazi administrator in Poland, killing nearly one million Jews at Treblinka, but he claimed he was simply following orders.

Teaching Blackface: A Lesson on Stereotypes

A teacher was put on leave for showing a blackface video during a lesson on racial segregation, sparking discussion over how to teach about stereotypes.

The Astros’ Sign-Stealing Scandal

The Houston Astros rode a wave of success, culminating in a World Series win, but it all came crashing down when their sign-stealing scheme was revealed.

The Central Park Five

Despite the indisputable and overwhelming evidence of the innocence of the Central Park Five, some involved in the case refuse to believe it.

The CIA Leak

Legal and political fallout follows from the leak of classified information that led to the identification of CIA agent Valerie Plame.

The Collapse of Barings Bank

When faced with growing losses, investment banker Nick Leeson took big risks in an attempt to get out from under the losses. He lost.

The Costco Model

How can companies promote positive treatment of employees and benefit from leading with the best practices? Costco offers a model.

The FBI & Apple Security vs. Privacy

How can tech companies and government organizations strike a balance between maintaining national security and protecting user privacy?

The Miss Saigon Controversy

When a white actor was cast for the half-French, half-Vietnamese character in the Broadway production of Miss Saigon , debate ensued.

The Sandusky Scandal

Following the conviction of assistant coach Jerry Sandusky for sexual abuse, debate continues on how much university officials and head coach Joe Paterno knew of the crimes.

The Varsity Blues Scandal

A college admissions prep advisor told wealthy parents that while there were front doors into universities and back doors, he had created a side door that was worth exploring.

Providing radiation therapy to cancer patients, Therac-25 had malfunctions that resulted in 6 deaths. Who is accountable when technology causes harm?

Welfare Reform

The Welfare Reform Act changed how welfare operated, intensifying debate over the government’s role in supporting the poor through direct aid.

Wells Fargo and Moral Emotions

In a settlement with regulators, Wells Fargo Bank admitted that it had created as many as two million accounts for customers without their permission.

Stay Informed

Support our work.

Quick Links

Current Courses Don Berkich: PHIL 2306.001: Intro to Ethics PHIL 2306.003: Intro to Ethics Minds and Machines Resources Reading Philosophy Writing Philosophy

- This Semester

- Next Semester

- Past Semesters

- Descriptions

- Two-Year Rotation

- Double-Major

- Don Berkich

- Stefan Sencerz

- Glenn Tiller

- Administration

- Philosophy Club

- Finding Philosophy

- Reading Philosophy

- Writing Philosophy

- Philosophy Discussions

- The McClellan Award

- Undergraduate Journals

- Undergraduate Conferences

What is a case study?

I will assign one of the Ethics Bowl cases where it is unclear whether or not a course of action described in the case is or would be morally right. You will be asked to evaluate the action in the story in light of one or more of the moral normative theories we've discussed this semester. As an example, consider the following case:

Ms. Jane Bradely is a successful commercial real estate agent. She is 41 years old, recently divorced, and is the mother of a 4 year old son who has Down's Syndrome. She has sole custody of her son, Algernon. Like most people with Down's Syndrome, Algernon is typically good natured, apparently very happy, and is mentally retarded. Ms. Bradely retains the services of a nanny to help take care of Algernon.

Ms. Bradely very much wants to have a healthy child. Towards that end, she opts for artificial insemination. Her physician warns her that the incidence of Trisomy-21 (the chromosomal aberation which results in Down's Syndrome) increases with the age of the mother. Understanding the risk, Ms. Bradely decides to go ahead with the procedure.

After several attempts, Ms. Bradely becomes pregnant. Unfortunately, karyotyping after amniocentesis reveals that the fetus has Trisomy-21. Ms. Bradely is deeply troubled by the news. She is now three months pregnant.

Having carefully evaluated her options, she decides to get an abortion.

After aborting her pregnancy she fully intends to try again in a few months.

Is it morally right for Ms. Bradely to have an abortion?

This case asks us to evaluate the morality Ms. Bradely's action of aborting her pregnancy. Of course the story is complicated, much as actual stories are complicated. There is a great deal to consider in such a case as this. But then there's a great deal to consider in the "real-world" as well.

You are asked to think about the case at length. Is her action right or wrong? Of course, we can't simply say right or wrong. We have to say right or wrong based on some particular conception of what it means for an action to be right or wrong. In other words, you need to select one of the theories we have discussed and reason, on the basis of that theory, about whether her action is right or wrong. Be sure that the theory you assume is defensible. CER, for example, would be a poor choice at this stage. It might be tempting to give an argument like:

Assuming CER, and given that Ms. Bradely is a member of the American Culture, it follows that it is morally right for her to abort her pregancy since she is in the first trimester and abortion is always permissible in the first trimester in the American Culture given the Supreme Court's decision in Roe v. Wade.

This is a well-put argument, clearly stating as it does the assumptions and clearly stepping as it does from the assumptions to the moral permissibility of her action. But just because the argument can be clearly stated does not mean that it is a good argument. In particular, this argument is obviously unsound. CER is one of the theories our Standards of Evaluation rejected. CER is self-contradictory and has implications which are absolutely unacceptable. Thus the person who put forward this argument would open themselves up to these and other criticisms, which is surely something to be avoided as much as possible.

Indeed, as we work through the theories we will discover a number that are critically unusuable in light of the assumptions they make. It will only be later that we find usuable theories. Nevertheless, it is important to learn how to apply indefensible theories so as to understand them better.

A further point should be made. The theories we consider should in no way be considered decision boxes where you plug in the facts of the case in the theory spits out an answer--"this action is morally wrong" or "this action is morally right". Ethics, as many of you will note, is never so clear-cut or straightforward. We must wrestle with extremely complicated issues. In the above case, for example, we have added the complication that Ms. Bradely's fetus has Down's Syndrome. The theories serve to make precise a particular conception of what it is for an action to be morally right or morally wrong. That does not mean that they suddenly make it black-and-white or even easy to see whether a particular action is right or wrong. All we can do in studying these often complicated issues is, naturally enough, the best we can. We try to make our assumptions clear and defensible. In particular, we try to make our conceptions of ethics clear and defensible by formulating them into theories which have a chance at passing our pre-established Standards. But then it is up to us to argue back and forth about what is in fact implied by a particular understanding of ethics. Sometimes it is obvious what follows, but sometimes it is not. Perhaps it would be nice if everything were straightforward and mechanical. But would any of us really want it that way? After all, it's nothing less than our lives and how we should live them that we're talking about here.

That said, let us describe each of the three sections in a Case.

The first section is the Argument :

Here you will assume a theory and argue, on the basis of that theory, to a conclusion. Your conclusion will be either "the act of __ is morally right" or "the act of __ is morally wrong". So, for example, in the above case your conclusion will either be "the act of Ms Bradely's aborting her pregnancy is morally right" or "the act of Ms. Bradely's aborting her pregnancy is morally right", whichever conclusion you think best follows from the theoretical assumption you've made. Then you will actually give an argument, preferably in paragraph form, to show that the conclusion does follow from the theory you've assumed. Presumably you will give the best argument you can.

The second section is the Critical Analysis :

Here you have the opportunity to criticize each other's arguments. You will be paired off with a partner and you will exchange your arguments. It is open to you to criticize any of the steps in your partner's argument and any of the assumptions your partner makes--either explicitly or implicitly and including the theory she or he has assumed. It is not open to you to criticize your partner. You are encouraged to see me if you do not understand the difference. You must state your criticisms clearly and carefully and provide appropriate justification.

The third and final section is the Response :

Here you have the opportunity to respond to your partner's criticisms. Your responses should be to show that (and how) your partner's criticisms fail, or to show that a better argument can be made for your conclusion which does not have the same problems as your first argument.

So that's the content of your case. The format should be followed precisely as the following outline.

Following the format precisely means that everything in your email should appear exactly as it does above, except, of course, what is in parentheses. Thus, "ARGUMENT" should be in all-caps and should be preceded by a series of dashes to demarcate the section.

Finally, some students find it odd or disconcerting that their case will include some of their partner's work - i.e., the Critical Analysis. They go to great lengths to include their own critical analysis, which only confuses me. I am very easily confused, so please do not include your critical analysis. A case should read like a point/counterpoint/counter-counterpoint debate. Your partner will include your critical analysis with her case, and you will be duly credited for your work.

- College of Liberal Arts

- Bell Library

- Academic Calendar

Advertisement

- Previous Article

- Next Article

- 1. Introduction

- 4. Discussion

- 5. Conclusion

The Case Study Method in Philosophy of Science: An Empirical Study

Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the 26th Biennial Meeting of the Philosophy of Science Association in Seattle, Washington (November 1–4, 2018) and the Workshop on Experimental Philosophy of Science at Aarhus University in Denmark (October 15–16, 2019). I thank Samuel Schindler for inviting me to the workshop and the audience for their helpful comments. I am also grateful to two anonymous reviewers of Perspectives on Science for helpful comments on an earlier draft of this paper. Special thanks as well to the Editor, Alex Levine.

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Search Site

Moti Mizrahi; The Case Study Method in Philosophy of Science: An Empirical Study. Perspectives on Science 2020; 28 (1): 63–88. doi: https://doi.org/10.1162/posc_a_00333

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

There is an ongoing methodological debate in philosophy of science concerning the use of case studies as evidence for and/or against theories about science. In this paper, I aim to make a contribution to this debate by taking an empirical approach. I present the results of a systematic survey of the PhilSci-Archive, which suggest that a sizeable proportion of papers in philosophy of science contain appeals to case studies, as indicated by the occurrence of the indicator words “case study” and/or “case studies.” These results are confirmed by data mined from the JSTOR database on research articles published in leading journals in the field: Philosophy of Science , the British Journal for the Philosophy of Science ( BJPS ), and the Journal for General Philosophy of Science ( JGPS ), as well as the Proceedings of the Biennial Meeting of the Philosophy of Science Association ( PSA ). The data also show upward trends in appeals to case studies in articles published in Philosophy of Science , the BJPS , and the JGPS . The empirical work I have done for this paper provides philosophers of science who are wary of the use of case studies as evidence for and/or against theories about science with a way to do philosophy of science that is informed by data rather than case studies.

Client Account

Sign in via your institution, email alerts, related articles, affiliations.

- Online ISSN 1530-9274

- Print ISSN 1063-6145

A product of The MIT Press

Mit press direct.

- About MIT Press Direct

Information

- Accessibility

- For Authors

- For Customers

- For Librarians

- Direct to Open

- Open Access

- Media Inquiries

- Rights and Permissions

- For Advertisers

- About the MIT Press

- The MIT Press Reader

- MIT Press Blog

- Seasonal Catalogs

- MIT Press Home

- Give to the MIT Press

- Direct Service Desk

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Statement

- Crossref Member

- COUNTER Member

- The MIT Press colophon is registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

The Use of Examples in Philosophy of Technology

- Open access

- Published: 27 September 2021

- Volume 27 , pages 1421–1443, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Mithun Bantwal Rao 1

5041 Accesses

Explore all metrics

This paper is a contribution to a discussion in philosophy of technology by focusing on the epistemological status of the example. Of the various developments in the emerging, inchoate field of philosophy of technology, the “empirical turn” stands out as having left the most enduring mark on the trajectory contemporary research takes. From a historical point of view, the empirical turn can best be understood as a corrective to the overly “transcendentalizing” tendencies of “classical” philosophers of technology, such as Heidegger. Empirically oriented philosophy of technology emphasizes actual technologies through case-study research into the formation of technical objects and systems (constructivist studies) and how they, for example, transform our perceptions and conceptions (the phenomenological tradition) or pass on and propagate relations of power (critical theory). This paper explores the point of convergence of classical and contemporary approaches by means of the notion of the “example” or “paradigm.” It starts with a discussion of the quintessential modern philosopher of technology, Martin Heidegger, and his thinking about technology in terms of the ontological difference. Heidegger’s framing of technology in terms of this difference places the weight of intelligibility entirely on the side of being, to such an extent that his examples become heuristic rather than constitutive. The second part of the paper discusses the methodological and epistemological import of the “example” and the form of intelligibility it affords. Drawing on the work of Wittgenstein (standard metre), Foucault (panopticism), and Agamben (paradigm), we argue that the example offers an alternative way of understanding the study of technologies from that of empirical case studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Technologizing the Transcendental, not Discarding it

Pieter Lemmens

Notes on a Nonfoundational Phenomenology of Technology

Robert Rosenberger

Philosophical Potencies of Postphenomenology

Martin Ritter

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction: Classical and Contemporary Philosophy of Technology

Heidegger once remarked that Dasein , human being, is ontically closest to itself, but ontologically we are farthest removed from our being. Does not something similar hold for examples, that we give them all the time but do we know what they are? In Philosophical Investigations , Wittgenstein draws attention to a curious artifact that is not an example of something but an example as example:

There is one thing of which one can neither say that it is one metre long, nor that it is notone metre long, and that is the standard metre in Paris.— But, this is, of course, not to ascribe any extraordinary property to it, but only to mark its peculiar role in the language-game of measuring with a metre-rule (Wittgenstein, 1953 , 21, emphasis in original).

A few lines later we read: “It is a paradigm in our language-game: something with which comparison is made. And this may be an important observation; but it is nonetheless an observation concerning our language-game.—our method of representation” (ibid., 22). The standard metre rule (the physical object) is as mundane as it is extraordinary, or rather, it is extraordinary not because of some intrinsic quality of this specific platinum bar but for the very reason that it is treated as a paradigm . It is extraordinary in that we cannot attribute length to it in meters as such for the very reason that it renders intelligible what length in meters is (of course, nowadays, it does not fulfill this role anymore, given the transition to a definition based on lightspeed in vacuum, and has gone from paradigm to relic). The objective of this article is to understand the relevance of the structure of such artifacts for the philosophy of technology.

Of the various developments that have taken place over the last 30 years or so in the emerging, inchoate field of philosophy of technology, the empirical turn (Achterhuis, 2001 ) stands out as having left the most enduring mark on the trajectory contemporary research takes (Brey, 2010 ). Footnote 1 Roughly, the “empirical turn” is an umbrella term for a collection of approaches aimed at bringing philosophy of technology into dialogue with the well-developed body of literature in the sociology of science and technology, or what is generally referred to as “science and technology studies” (STS). A chief methodological tenet of empirically oriented philosophy is its adherence to case-study research (Gerring, 2007 ; Yin, 2013 ) and a constructivist outlook. Footnote 2 Whether it is politics (Winner, 1986 ) that is under investigation, or the technical mediation of experience (Ihde, 1993 ), or the reproduction of capitalist hegemony (Feenberg, 2002 ), empirically oriented philosophy of technology tends to highlight the contingency of technology, its development, its use, placing itself at a critical distance from earlier “substantive” theories. Bringing philosophy of technology into debate with STS is the position taken by representatives of empirically oriented thinkers such as Verbeek ( 2015 ), who believes that substantive theory adheres to outdated conceptions of human-society-technology relations, whereas Feenberg ( 1999 ) maintains the position that his main sources of inspiration (Marx and critical theory) can learn from the insights of (social) constructivism in terms of its study of particular cases, be it that Feenberg is much more reluctant to let go of “macro-concepts”. While case-study research has many controversies surrounding it and its methodologies, another way of putting it is that the empirical turn is a turn to things in concrete (Coeckelbergh, 2018 ), as opposed to concepts in abstract, and perhaps more of an attitude than a methodology in the strict sense.

The empirical turn in the philosophy of technology has in many respects brought about what Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions did a few decades earlier in the philosophy of science: just as historians and sociologists of science found that social practice was constitutive of scientific rationality, philosophers of technology came to see the practical factors implied in the formation of technical artifacts, and as philosophers of science started studying the intricacies of specific sciences as opposed to science as such, philosophers of technology began to recognize the specificities of technologies. Instead of understanding science and society as two separate realms only intersecting and interacting in terms of cause and effect, a discourse emerged that stressed the co-construction or co-evolution of science and society (i.e., how “external” social and economic factors influence science, and how science in a sense takes place within these relations), which, mutatis mutandis , was taken up and appropriated by philosophers of technology.

To be sure, this analogy only goes so far: the sociological turn in philosophy of science transformed the discipline from a prescriptive one (Popper, Vienna Circle) into a descriptive one. The stakes of the empirical turn in philosophy of technology are less clear. Achterhuis ( 2001 ) speaks of a difference in approach between “classical” philosophy of technology (Heidegger, Marcuse, Ellul, Jonas) and contemporary theory. Footnote 3 The distinction is made on the basis of the former’s preoccupation with transcendental and historical conditions and the latter’s with “real” empirical technologies. Feenberg ( 1999 ) distinguishes his own “critical constructivism” from Heidegger’s essentialism by taxing Heidegger with a view which reduces technology to pure functionality, one that has Heidegger overlooking the social meanings of technologies, and how technology emerges from social relations. Feenberg’s execution of the empirical turn, however, retains an element of transcendental discourse in its dual layer instrumentalization theory, in which the layers of function and meaning make up the a-historic essence of technology and empirical case studies reveal how instrumentalization is concretized.

Ihde’s ( 2000 ) postphenomenological pluralism rejects transcendentalism and essentialism tout court , preferring to describe the effects of technologies on experience instead of the monolithic, reificatory character ascribed to technology by classical thinkers, arguing, for example, that Marcuse analyzed Technology with a capital “T” (1990, 6), or rather techniques . According to Van Den Eede et al. ( 2015 ), the chief virtue of classical philosophy of technology lay in the destruction of the neutrality thesis, sometimes called “instrumentalism,” and that the empirical turn is the reinterpretation of real technologies having dispensed with the image of technology as a mere means to an end.

The empirical turn is not without its detractors, however, such as Scharff ( 2011 ), who argues that philosophy of technology has lost track of abstraction by venturing too much into the concrete. The reliance on case-study research at the micro-level, as practiced in STS, may reveal nuances and details, but case-study research is equally bad at what grand theory excels at, such as the elucidation of systematic technological developments, or, a fortiori , the relations between technology and modernity as such. Accordingly, there has been a call for a bridging of the gap between technology studies and modernity theory, and indeed, some steps have been taken in that direction (e.g., Misa et al., 2003). Nevertheless, the discarding of the transcendental perspective has met with considerable hostility, ranging from warnings about how the empirical turn “carries the danger of turning ‘philosophy of technology’ into a shallow and uncritical field, parasitically dependent on developments in industry” (Smith, 2014 , 15) to assertions about “the necessity of a ‘transcendental (re)turn’” (Lemmens, 2015 , 4).

This ungenerous assessment is unwarranted insofar as empirically oriented philosophy of technology does not, in fact, advocate a wholesale abolition of philosophical abstraction, but, rather, desires to set out from the empirical description of actual technologies—aiming to determine the transformative character of technologies with regard to such philosophical fields such as politics or ethics. (Verbeek, 2015 ). One way of putting the matter differently is that there is no hard divide between “empirical” thinkers, who only make context-dependent claims and “transcendental” thinkers, who only engage in characterizations of technological epochs. Another way of making the same point is that the difference between the two schools of thought is not so much “real” as it is rhetorical or even “polemical”. Footnote 4 For example, Feenberg ( 1999 , 2002 , 2010 ) construes his critical theory/critical constructivism by engaging with Marx, the Frankfurt school, and social constructivism, but is at the same reluctant to let go of macro-concepts, such as (the technical code of) capitalism, class/formal bias and its counter-hegemony in democratic rationalization, while not shying away from concrete analysis (user appropriation of the Minitel as an exemplary case). Put differently, the claim that “empirically” oriented philosophy of technology only engages with the concrete, and empirical, and neglects abstraction is a more difficult position to maintain. In that sense, the analysis that follows is akin to and indebted to the work of Borgmann ( 1984 ), who in fact gives an analysis of the contemporary technological era in a very Heideggerian spirit, but is methodically more difficult to put in one category or the other: in fact his analysis of the “device paradigm” is an “ontical” rewriting of Heideggerian insights by more supple concepts such as pattern, example, and paradigm.

Our own inclination in this debate is follow up on this style of analysis: the empirical turn has brought about a more nuanced and evenhanded view on the particularities of specific technologies in comparison to more classical thinkers and a more direct link to technology development, and has been helpful when one is interested in fields such as ethics and politics, but that it is more difficult to see how the repetition of case studies brings us closer to a philosophy of technology. In a certain sense, philosophy of technology is in an aporia, having to choose between the general form of the transcendental and the particular content of the empirical. Thus, we would ask, how can we rethink the opposition between the transcendental and the empirical within philosophy of technology? Indeed, can the empirical and the transcendental meet? Is there a point of convergence where the two intertwine and become indistinguishable? Thus, is there a possibility of a philosophical approach to technology studies that starts off from “actual technologies” but does not treat them as empirical givens? In the following we will argue that the notion of the “paradigm” can cast the debate in a different light: empirically oriented philosophers may argue that transcendentalists should get out of their armchair, whereas the latter uphold the view that empirical philosophy is an oxymoron; the aporia resorts to polemics as to whether philosophy has its own proper object or is more or less in line with the sciences (such as STS). Footnote 5 Put simply, we argue that the empirical turn is a turn to examples of technologies, but in a very specific way, namely, by the formation of empirical case studies. In this paper we explore how the notion of “paradigm” can shed light on the philosophical meaning of technologies without treating them as empirical givens.

Any mention of “paradigm” will immediately evoke associations with, and cannot bypass, the aforementioned Thomas Kuhn’s seminal work on the paradigmatic character of the development of the natural sciences. Though notoriously equivocal, Footnote 6 in Structure the notion of paradigm has at least two distinct meanings. First, paradigm is a disciplinary matrix or “the constellation of group commitments” (Kuhn, 1962 , 182) that signifies the theories, beliefs, methods, and convictions upheld by and defining a community of scientists. This is indeed the meaning that paradigm has in common parlance, for example, when we say that Marxism was the dominant paradigm in technology studies in the 1970s, whereas nowadays it is STS. The second meaning, which Kuhn ( 1962 , 187) considered to be “the most novel and least understood aspect” of his book, is that of shared example, or exemplar . Kuhn’s own example is Newton’s second law of motion, and his point is probably well known to any freshman in natural sciences. Becoming a scientist consists less in rational reflection, let alone in falsification or verification, than that it does in the repetition of such exemplars. Instead of understanding science as a rule-based enterprise, Kuhn’s depiction emphasizes the normative character of exemplars, which need to be mastered in order to count as an accepted member of a scientific community.

Kuhn’s interest in paradigms sprang from their guiding scientists’ normative behavior; ours here lies in their ontological, epistemological and methodological import. This paper has a two-fold structure. First, we start off by looking at Heidegger’s philosophy of technology, which has been described as too abstract, too gloomy, and lacking practical insight. Without wishing to settle these matters, we interpret his thinking in a particular way: as against thinking in paradigms, and as thinking in terms of being , making his examples in the end heuristic rather than constitutive ; our main reason for discussing Heidegger is not so much to give a new interpretation of his work, but rather to show how his thinking, and in this context, his use of examples, has given rise to a turn away from the type of analysis he engages in. The second part of this paper contains its positive contribution through readings of Wittgenstein, Foucault, and Agamben. In Wittgenstein’s analysis of the standard metre we find an ontology of paradigms vis-à-vis the Platonist metaphysical tradition (Sect. 3 ). In Sect. 4 , we show that Foucault’s analysis of the panopticon and panopticism , his most directly relevant contributions to the philosophy of technology, offer him a methodological way of evading the empirical/transcendental distinction he finds so problematic in the “Age of Man.” Finally, we draw on the work of Agamben and his notion of example/paradigm as a generalization of Foucault’s methodology, making explicit and systematic Foucault’s epistemological and methodological relevance for the notion of analogy for philosophy of technology. The relation between the authors is thus a move from ontology (Wittgenstein), through exhibition (Foucault), towards systematization as method (Agamben). In the end our aim is to raise new questions about philosophical thinking about technology: the empirical turn has brought about a very fruitful and worthwhile turn towards things, and allows for a way about thinking about the meaning and ontology of the technological age, not so much in terms of abstract concepts such as “Enframing” or “Total mobilization,” but we want to draw attention to singularities, which are at the basis of our technological age: in biotechnology we can think, for example, of the Arabidopsis plant (as a concrete paradigm), in computer science of the Turing Machine (as the standard metre of computationality); these remarks will however be preliminary, setting the stage for a research agenda. Accordingly, the paper does not end with conclusion perse, but rather as a question on how paradigm/analogy can raise overlooked questions in philosophical thinking about technology.

2 The Interior of Beings and the Exterior of Being: Heidegger and the Hydroelectric Plant

The difference between the transcendental and the empirical, as Achterhuis ( 2001 ) uses it, goes back to Kant, who employs it in an epistemic context, i.e., the conditions under which pure mathematics, physics, and metaphysics as a science are possible, and defines it as a mode of cognition “that is occupied not so much with objects but rather with our mode of cognition of objects insofar as this is to be possible a priori” (Kant, 1998 , 133). In Critique of Pure Reason , Kant regards this project as too comprehensive to complete and limits himself to spelling out the necessary conditions of possibility for objects of experience, viz., the forms of intuition of space and time and the twelve categories of understanding. In the strict technical sense, an argument is transcendental when a given premise cannot be thought without assuming a nonobvious presupposition without which the premise cannot be thought (Rorty, 1971 ; Stroud, 1968 ); when reduced to its bare essentials, however, the difference between the transcendental and the empirical arguably boils down to a way of developing a more sophisticated jargon serving to rephrase the form/content dichotomy. That is to say, Kant finds in the form of the transcendental structures of experience a transhistorical basis that is exempt from the contingency of the content of that very experience. In philosophy of technology, more recently, there is no a consensus view on what to make of this distinction within the field. Lemmens ( 2021 ), for example, argues for a return to the transcendental in the historical technological sense, in effect arguing for a Stieglerian view in which technics is the transcendental, but also more generally, he argues that philosophy of technology needs to reckon with totality in view of the planetary crisis, or more popularly: the Anthropocene. Besmer ( 2021 ) argues that philosophy of technology also needs a turn away from the empirical but perhaps not towards the transcendental, in fact arguing that the very distinction is not very useful from the outset. Zwier et al. ( 2016 ), on the other hand, argue for the continuing relevance of Heideggerian questioning for thinking about technology. Heidegger’s philosophy of technology, as elaborated in The Question Concerning Technology , is often regarded as the most pregnant instantiation of a “classical, transcendental” approach, if only for the fact that it does not analyze technology in terms of technical artifacts or systems but identifies the essence of technology with something that “is by no means anything technological” (Heidegger, 1977 , 4). This “something” is being.

Perhaps there is no other being beyond what has been enumerated, but perhaps, as in the German idiom for “there is,” ( es gibt literally, it gives), still something else is given . Even more. In the end something is given which must be given if we are able to make beings accessible to us as beings and comport ourselves towards them, something which, to be sure, is not but which must be given if we are able to experience and understand any beings at all. We are able to grasp beings as such, as beings, only if we understand something like being (Heidegger, 1982 , 10, emphasis in original).

From the outset, Heidegger’s questioning is guided by his self-professed most profound contribution to philosophy, i.e., the ontological difference , the difference between beings (entities, the ontic) and that on the basis of which beings can show themselves as such, being (the ontological):

It is a distinction which is first and foremost constitutive for ontology. We call it the ontological difference —the differentiation between being and beings. Only by making this distinction—krinein in Greek— not between one being and another being but between being and beings do we first enter the field of philosophical research (Heidegger, 1982 , 17, emphasis in original).

In this context, a few things stand out regarding the ontological difference. Being precedes, or more precisely, is concomitant with any showing of beings; being is “no class or genus of entities” but “ the transcendens pure and simple ” (Heidegger, 1962 , 62); being is the “object” proper of philosophy. In the traversal of the pathway of his thinking, Heidegger would gesture more and more towards being, to such an extent that beings would drop out of sight. In Being and Time , Heidegger tackles the question of the meaning of being by interrogating an “exemplary being”— lest we say paradigm—, i.e., human being, or, more precisely, the being that we are ourselves and to whose constitution a pre-understanding of being belongs and which has questioning itself as a mode of being.

Heidegger’s ontology takes the form of a revealing or unveiling of being (to which concealing necessarily belongs) by means of the passing over of the implicit pre-understanding of Dasein of the being of beings into explicit understanding (Heidegger, 1962 , 61, 188–94). This essentially circular interpretation rests on the distinction between implicit/explicit, or showing/not-showing; it is, in brief, phenomenological (Derrida, 1982 , 126), relating not to the empirical what of things, but to their how (Heidegger, 1962 , 50). Crowell and Malpas ( 2007 ) observed, the extent to which this involves the transcendental in the Kantian sense is unclear, as witnesses this passage:

We also call the science of being, as critical science, transcendental science . In doing so we are not simply taking over unaltered the concept of the transcendental in Kant, although we are indeed adopting its original sense and its true tendency, perhaps still concealed from Kant. (Heidegger, 1982 , 17) Footnote 7

It is clear that Heidegger wants to remove the transcendental from the epistemic context used by Kant and from its subjectivist conception. On a subtler note, Heidegger’s reinterpretation of the Kantian project consists in the fact that his conception of the transcendental does not signify the a priori of an object of experience but rather the hermeneutic conditions under which a being can show itself as the being that it is ( as an tool of practical circumspection, as an object of objective contemplation) (Carman, 2003 ).

In fact, it was only until 1930 that Heidegger would explicitly associate himself with transcendental philosophy and a conception of philosophy as a science, claiming in his lectures that philosophy is no science but something “ comparable with nothing else in terms of which it could be positively determined. In that case, philosophy is something that stands on its own , something ultimate ” (Heidegger, 1995 , 2, emphasis in original). Heidegger’s essays on technology belong to his post-1930s work, after the so-called “turning,” in which he would no longer interrogate the meaning of being through the pre-understanding of Dasein but would venture into the historical destining of being.

Whether or not Heidegger’s later work still adheres to the principles of phenomenology is unimportant here, Footnote 8 for the irreducible play between implicit/explicit, showing/not-showing, light/dark, concealment/unconcealment remains firmly intact. Heidegger enters the field of technological research equipped with the ontological difference—or, put differently, the question concerning technology was never a question concerning technologies; Heidegger’s question concerning technology may have as its impetus the ever more pervasiveness of ontic technologies in the modern age, but he tackles this question at the level of being, not that of beings. Nevertheless, Heidegger does not shy away from analyzing an example of a modern technology that, at face value, exhibits archetypical exemplarity, the hydroelectric plant. Of the hydroelectric plant Heidegger writes:

The hydroelectric plant is set into the current of the Rhine. It sets the Rhine to supplying its hydraulic pressure, which then sets the turbines turning. This turning sets those machines in motion whose thrust sets going the electric current for which the long-distance power station and its network of cables are set up to dispatch electricity. In the context of the interlocking processes pertaining to the orderly disposition of electrical energy, even the Rhine itself appears as something at our command. The hydroelectric plant is not built in the Rhine River as was the old wooden bridge that joined bank with bank for hundreds of years. Rather the river is dammed up into the power plant. What the river is now, namely a water supplier, derives from out of the essence of the power station. (Heidegger, 1977 , 16)

For Heidegger, the construction and functioning of the hydroelectric plant challenges the Rhine to deliver energy, which is “unlocked,” and “what is unlocked is transformed, what is transformed is stored up, what is stored up is, in turn, distributed, and what is distributed is switched about ever anew” (ibid.). This challenging character derives from, but does not have its ground in, the calculations of modern natural science, Heidegger alleges, and this is provocative about this assertion, that modern science is ontologically dependent on technology, pace the historical priority of the scientific revolution to the industrial one; challenging was not present in traditional, pre-modern technology. In the case of a windmill, for example, the wind was merely utilized, as something serviceable; its sails are “left entirely to the wind’s blowing. But the windmill does not unlock energy from the air currents in order to store it” (ibid., 14). This contrast between modern industrial technology and traditional, artisanal technologies is expressed several times in the Question , such as in the peasant taking care of his land and the modern transformation of agriculture into a food industry (ibid., 15).

It is tempting to read Heidegger’s differentiation between pre-modern and modern technology as the juxtaposition of two lists consisting of “good” traditional technologies on the one hand and “bad” modern ones on the other. But this would not do justice to his ontologizing of technology. To be sure, Heidegger does want to differentiate between pre-modern and modern technology, but on the level of being, and not of beings. The differentiation between the relationship with the manifest of the ancient Greeks and ours resides in a prior revealing , captured in the word aletheia , truth. Footnote 9 Technology, or techne , is rooted in such revealing and is a way of revealing. In Greek times, Heidegger alleges, such techne was intrinsically intertwined with poiesis , with bringing-forth (see also: Heidegger, 1993 , 184).

Somewhat simplified, Heidegger points here to the phenomenon well known in popular culture by Michelangelo’s remark that every stone has a statue inside it and the task of the sculptor is to dis-cover it. This poiesis brings-forth in such a manner that it brings-something-into-presence. In the epoch of modern technology, the poetry of technology has been lost. Modern technology brings-forth in such a manner that it does not bring beings-into-presence, but covers them over. Heidegger’ name for the prior revealing that is at the basis of this kind of bringing-forth is enframing ( das Gestell ) (1977, pp., 19, 19). Enframing reveals reality, and, indeed, humanity itself as standing-reserve ( Bestand ), as a resource to be ordered, exploited and transferred at will. The character of enframing is to totalizing: “it drives out every possibility of revealing” (ibid., 27). The world as such shows itself as standing-reserve.

Heidegger’s approach remains influential in contemporary technology studies and philosophical thinking about technology, but mostly through eliciting antagonism; his work on enframing usually functions as a good lesson on how not to do philosophy of technology. Two “continental” approaches representative of the empirical turn, Don Ihde’s “postphenomenology” and Andrew Feenberg’s “critical constructivism,” share the assumption that Heideggerianism is an intellectual dead-end street. Ihde ( 1993 , 106) speaks of Heidegger’s nostalgic preference for artisanal technologies in favor of modern ones, while Feenberg ( 2010 , 24) thinks that the ontological difference “may have once seemed more interesting than it does today,” and that Heidegger “literally cannot discriminate between electricity and atom bombs, agricultural techniques and the Holocaust” ( 1999 , 187), since they “[a]ll are merely different expressions of the identical ‘enframing’,” Footnote 10 and that he “cannot take the notion of technological reform seriously because he reifies modern technology as something separate from society, as an inherently contextless force aiming at pure power” ( 2010 , 25).

Both Ihde’s and Feenberg’s critiques are interesting because they assume that we can differentiate between atom bombs and agricultural techniques, between a windmill and a power plant. However, if we take Heidegger’s claim seriously that ontology does not consist in any “cataloguing of the furniture of the universe” (Brandom, 1983 , 388) and that enframing does not “mean the general concept of such resources” (Heidegger, 1977 , 29), then talk of ontic technologies being “expressions” of “enframing” or “preferences” for one ontic technology in favor of the other becomes idle. Put differently, the hydroelectric plant is not a paradigm of enframing, but rather, the example belongs to the interior of beings and the exterior of being . Footnote 11 The point here is as follows: whereas in Being and Time it is clear that the understanding of being of Dasein is grounded ontically in its being ontological, or put differently: the difference between Dasein and the categories in Being and Time is to be understood in terms of the mode of being and understanding of being of Dasein (Brandom, 1983 ). In the Question this ontic rooting of ontology is much less clear, as observed by “empirical turner” Verbeek ( 2005 , 63): “[Heidegger’s] words reveal that, for him, what is happening is not that the construction of an electrical generating plant has brought about the transformation of the Rhine into standing-reserve, but rather the other way around—that the unlocking of the Rhine as standing-reserve has brought about the construction of an electrical power plant in it. This is underscored by his remark about the tourist industry[.]”.

3 What is a Paradigm: Wittgenstein and the Standard Metre

Heidegger’s ontological difference, by definition, precludes the possibility of a being coming-into-presence prior to any clearing of being; Heideggerian phenomenological showing is the showing of this prior clearing. In this section we argue, however, that Heidegger was not sensitive to another type of showing than of an object of hermeneutics, i.e., in terms of the prior disclosure of the whole from which a part is understood. We look for a different type of non-empirical showing in terms of a para-showing of the part towards the whole. In his early work Tractatus-Logico Philosophicus , indebted to Kantianism and associated with logical positivism, Wittgenstein also struggled with the transcendental and showing/not-showing, declaring that “What can be shown, cannot be said” and that “Logic is transcendental” (Wittgenstein, 2001 , 31, 78, emphasis in original). True or false (scientific) propositions belong to the realm of the sayable, but their form, the ground of the sayable, eludes enunciation, it is transcendental. By the time of his later work, of which such books as Philosophical Investigations and On Certainty are the precipitates, and in some sense close to post-structuralism (e.g., Staten, 1984 ), Wittgenstein would neither use metaphysical jargon such as “transcendental” nor entertain the belief that scientific propositions are the only bearers of genuine meaning, nor that logical form is the ground of the sayable:

But if someone were to say: “So logic too is an empirical science” he would be wrong. Yet this is right: the same proposition may get treated at one time as something to test by experience, at another as a rule of testing. (Wittgenstein, 1969 , 15)

Nevertheless, Wittgenstein’s interest in finding the grounds of the sayable and the role showing plays in it did not wane (McGinn, 2001 ), to which his analysis of the meter rule attests. The standard metre is an empirical phenomenon but at the same time it is not: it is a material artifact that renders intelligible what a meter is . In this instance, talk of transcendental or empirical are problematized because we are dealing with a phenomenon the content of which expresses its own form. Wittgenstein’s remark surfaces in his rejection of what might be called a Platonist treatment of universal categories, “the great sources of philosophical bewilderment: a substantive makes us look for a thing that corresponds to it” (Wittgenstein, 1958 , 1), or the “indestructibles”(Wittgenstein, 1953 , 24). There is no-thing that corresponds to length just as there is nothing that corresponds to the color red as such. The Platonist solution to this problem is idealism : the universals belong to a realm ontologically distinct from that of the empirical, the sensible. Footnote 12 Wittgenstein’s position, however, is a problematization of this very distinction: the ideal here appears as the empirical and vice versa.