To Save the Soul of America

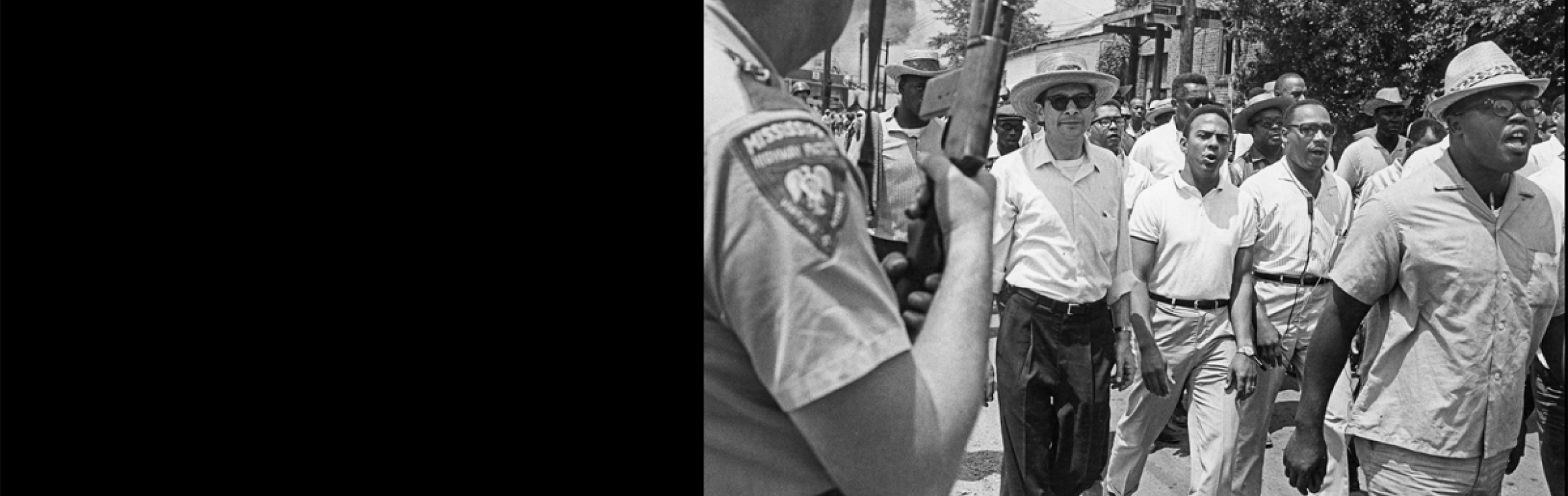

“Somewhere I read of the freedom of assembly. Somewhere I read of the freedom of speech. Somewhere I read of the freedom of press. Somewhere I read that the greatness of America is the right to protest for right. And so just as I say we aren’t going to let any dogs or water hoses turn us around, we aren’t going to let any injunction turn us around. We are going on.” —“I’ve Been to the Mountaintop,” Address Delivered at Bishop Charles Mason Temple, 3 April 1968. Photo of King and Andrew Young marching in Philadelphia, Mississippi, June 1966, courtesy of the Bob Fitch Photography Archive, Stanford University Libraries.

Welcome to the Martin Luther King, Jr. Research & Education Institute

Building upon the achievements of Stanford University's Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers Project, the King Institute supports a broad range of educational activities illuminating Dr. King's life and the movements he inspired.

The King Papers

A comprehensive collection of Dr. King's most significant correspondence, sermons, speeches, published writings, and unpublished manuscripts.

King Resources

Database with the archival locations of King-related documents, ancillary Institute publications, and recommended readings.

The Institute

News, events, and information about the staff of the King Papers Project.

King Encyclopedia

The Encyclopedia , based on the extensive historical research originally conducted for The Papers , has over 280 articles on civil rights movement figures, events, and organizations.

Explore the King Institute

National history day.

We are always excited to hear from students engaged in historical research about Dr. King. Unfortunately, we do not have the capacity to respond to all the research requests we receive. Our website offers some of the best primary and secondary sources available and we hope you enjoy the process of discovering new information and ideas about the past and present.

Copyright Notice

The Institute cannot give permission to use or reproduce any of the writings, statements, or images of Martin Luther King, Jr. Please do not contact us for this purpose. To obtain proper authorization for use of Dr. King's works and intellectual property, please contact Intellectual Properties Management (IPM), the exclusive licensor of the Estate of Martin Luther King, Jr., Inc. at [email protected] or 404 526-8968. Screenshots are considered by the King Estate a violation of this notice.

Dr. Lerone A. Martin

The second faculty director of the King Institute, Dr. Martin is Associate Professor of Religious Studies at Stanford University. Previously, he was a member of the faculty at the John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics at Washington University in Saint Louis.

Recent News

Statement by king institute faculty director dr. lerone martin on the passing of mr. dexter scott king.

January 22, 2024

- Announcement

Dexter Scott King, son of Martin Luther King, Jr., dies at 62

Online King Records Access (OKRA)

Document Research Requests

King Papers Publications

Information for

Suggested readings about the Civil Rights Movement, fun facts, and audio-visual resources.

Primary and secondary sources about the modern African American Freedom Struggle.

King-related primary and secondary sources and a guide for History Day research.

Researchers

A database of King-related primary documents and recommended scholarly sources.

Join the March

National Historical Publications & Records Commission

The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr.

Stanford University

Additional information: https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/publications/king-papers

A comprehensive edition of the papers of Martin Luther King, Jr. (1929 –1968) clergyman, activist, and leader in the African-American Civil Rights Movement. He is best known for his role in the advancement of civil rights using nonviolent civil disobedience. King has become a national icon in the history of American progressivism. A Baptist minister, King became a civil rights activist early in his career. He led the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott and helped found the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in 1957, serving as its first president. With the SCLC, King led an unsuccessful struggle against segregation in Albany, Georgia, in 1962, and organized nonviolent protests in Birmingham, Alabama, that attracted national attention following television news coverage of the brutal police response. King also helped to organize the 1963 March on Washington, where he delivered his "I Have a Dream" speech. This edition of speeches, sermons, correspondence, and other papers of America’s foremost leader of the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. The project was initiated by the King Center in Atlanta before moving to the Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford.

Seven completed volumes of a planned 14-volume edition

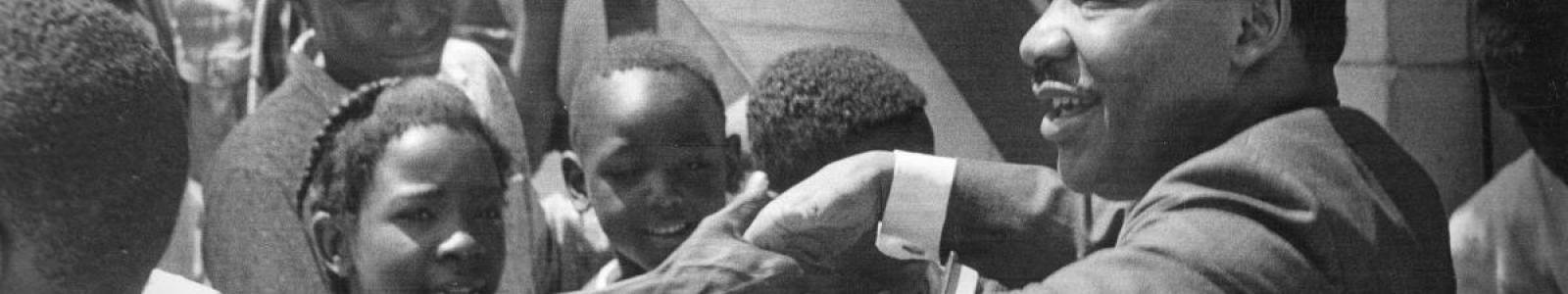

Martin Luther King, Jr. addresses the crowd at the Civil Rights March, August 28, 1963. National Archives.

Previous Record | Next Record | Return to Index

Black Power

Although African American writers and politicians used the term “Black Power” for years, the expression first entered the lexicon of the civil rights movement during the Meredith March Against Fear in the summer of 1966. Martin Luther King, Jr., believed that Black Power was “essentially an emotional concept” that meant “different things to different people,” but he worried that the slogan carried “connotations of violence and separatism” and opposed its use (King, 32; King, 14 October 1966). The controversy over Black Power reflected and perpetuated a split in the civil rights movement between organizations that maintained that nonviolent methods were the only way to achieve civil rights goals and those organizations that had become frustrated and were ready to adopt violence and black separatism.

On 16 June 1966, while completing the march begun by James Meredith , Stokely Carmichael of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) rallied a crowd in Greenwood, Mississippi, with the cry, “We want Black Power!” Although SNCC members had used the term during informal conversations, this was the first time Black Power was used as a public slogan. Asked later what he meant by the term, Carmichael said, “When you talk about black power you talk about bringing this country to its knees any time it messes with the black man … any white man in this country knows about power. He knows what white power is and he ought to know what black power is” (“Negro Leaders on ‘Meet the Press’”). In the ensuing weeks, both SNCC and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) repudiated nonviolence and embraced militant separatism with Black Power as their objective.

Although King believed that “the slogan was an unwise choice,” he attempted to transform its meaning, writing that although “the Negro is powerless,” he should seek “to amass political and economic power to reach his legitimate goals” (King, October 1966; King, 14 October 1966). King believed that “America must be made a nation in which its multi-racial people are partners in power” (King, 14 October 1966). Carmichael, on the other hand, believed that black people had to first “close ranks” in solidarity with each other before they could join a multiracial society (Carmichael, 44).

Although King was hesitant to criticize Black Power openly, he told his staff on 14 November 1966 that Black Power “was born from the wombs of despair and disappointment. Black Power is a cry of pain. It is in fact a reaction to the failure of White Power to deliver the promises and to do it in a hurry … The cry of Black Power is really a cry of hurt” (King, 14 November 1966).

As the Southern Christian Leadership Conference , the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People , and other civil rights organizations rejected SNCC and CORE’s adoption of Black Power, the movement became fractured. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Black Power became the rallying call of black nationalists and revolutionary armed movements like the Black Panther Party, and King’s interpretation of the slogan faded into obscurity.

“Black Power for Whom?” Christian Century (20 July 1966): 903–904.

Branch, At Canaan’s Edge , 2006.

Carmichael and Hamilton, Black Power , 1967.

Carson, In Struggle , 1981.

King, Address at SCLC staff retreat, 14 November 1966, MLKJP-GAMK .

King, “It Is Not Enough to Condemn Black Power,” October 1966, MLKJP-GAMK .

King, Statement on Black Power, 14 October 1966, TMAC-GA .

King, Where Do We Go from Here , 1967.

“Negro Leaders on ‘Meet the Press,’” 89th Cong., 2d sess., Congressional Record 112 (29 August 1966): S 21095–21102.

- Divisions and Offices

- Grants Search

- Manage Your Award

- NEH's Application Review Process

- Professional Development

- Grantee Communications Toolkit

- NEH Virtual Grant Workshops

- Awards & Honors

- American Tapestry

- Humanities Magazine

- NEH Resources for Native Communities

- Search Our Work

- Office of Communications

- Office of Congressional Affairs

- Office of Data and Evaluation

- Budget / Performance

- Contact NEH

- Equal Employment Opportunity

- Human Resources

- Information Quality

- National Council on the Humanities

- Office of the Inspector General

- Privacy Program

- State and Jurisdictional Humanities Councils

- Office of the Chair

- NEH-DOI Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Partnership

- NEH Equity Action Plan

- GovDelivery

The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr.

Division of research programs.

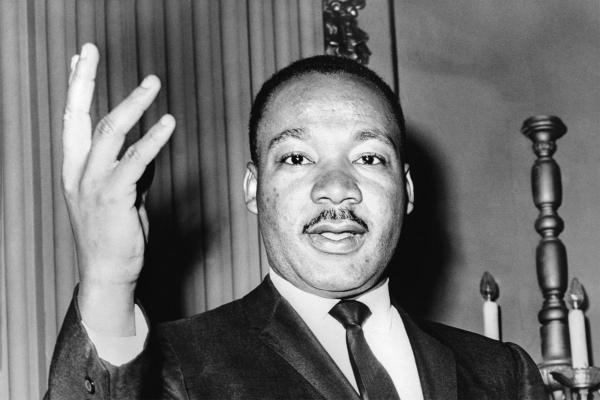

Martin Luther King Jr, 1964.

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

This definitive edition of Dr. King’s most significant speeches, sermons, correspondence, public statements, published writings and unpublished manuscripts documents King’s family roots, his rise to prominence, and influence as a national spokesperson for civil rights.

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Finding middle way out of Gaza war

Roadmap to Gaza peace may run through Oslo

Why Democrats, Republicans, who appear at war these days, really need each other

The Harvard Crimson’s April 8, 1968, edition.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Losing King: Shock, sorrow, anger, and a voice time hasn’t silenced

Five decades after assassination, views from Gates, Gordon-Reed, others on the nation then and now

Colleen Walsh

Harvard Staff Writer

Fifty years ago the murder of a Baptist minister turned Civil Rights giant shook the nation. Just after 6 p.m. on April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. was gunned down on the second-floor balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tenn. There to support the city’s striking sanitation workers, King was about to head to dinner when he was struck in the jaw by a single bullet. In a country already roiled by racial violence and civil unrest, the killing set off a wave of deadly riots from coast to coast.

We asked a group of Harvard scholars to reflect on King’s life, death, and legacy. Historians Annette Gordon-Reed and Henry Louis Gates Jr . recalled where they were when they heard about the assassination. Philosopher Tommie Shelby remembered his earliest impressions of King’s language and rhetoric. All three shared thoughts on how the Civil Rights leader would view today’s America. Political theorist Danielle Allen , set to deliver the keynote at a King-focused conference on Friday, said that 50 years on, his work remains unfinished.

Annette Gordon-Reed (from left), Danielle Allen, Henry Louis Gates Jr., and Tommie Shelby.

File photos by Stephanie Mitchell and Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff

‘It’s a shock that I’ve never gotten over’

A senior in high school, Gates was at home in Piedmont, Va., watching TV when an announcement interrupted the news.

“I had three best friends that were black and they came over and we were just shocked — we were stunned,” said Gates, the Alphonse Fletcher Jr. University Professor and director of the Hutchins Center . “There was nothing that we could do.

“Basically it’s a shock that I’ve never gotten over, really. I mean, I still can’t believe it when I watch the footage.”

The shock lingered in Gates’ voice as he considered King’s relative youth.

“He seemed like such an old man but he was 39 years old. He did all of that when he was 39, and I definitely believe — I am one of the black people who thinks there was some kind of conspiracy to kill him. I think he could have been the first black president and I don’t think America was ready for that.”

King, Gates added, was “moving toward an amalgamation of race and class and that was threatening to the system.”

What would he think of the U.S. today?

Gates said King would be surprised by how much the country has moved the dial, and stunned by the numbers of upper- and middle-class African-Americans. “But he would be equally shocked that the percentage of black children living at or beneath the poverty line is roughly the same as it was in 1970, roughly the same as it was when he died.”

And while King would be pleased by the progress made since 1968, and “astonished and delighted” that the country was led by an African-American president for eight years, he would also be dismayed “at mass incarceration” and at “deindustrialization which interrupted the cycle of moving from the working class to the middle class and the middle class to the upper-middle class.”

‘ It was clear that he was making lots of people angry ’

More like this.

When King came to Harvard

Beyond ‘I Have a Dream’

Gordon-Reed, 9 years old in 1968, was with her mother at the home of one her friends “when her son came into the room and told us that King had been assassinated.”

Her Texas community’s reaction was one of “great sadness,” said Gordon-Reed, Harvard Law School ’s Charles Warren Professor of American Legal History, a professor of history in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences , and a Pulitzer Prize winner for “The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family.”

“But this was a small town with a small black population,” she said. “More open anger was expressed in urban communities.”

Gordon-Reed said her mother and father “were not surprised” by King’s murder. “It was clear that he was making lots of people angry. The possibility of violence was always present given all that was at stake.”

Her parents’ reaction was likely shared by countless Americans. King had endured repeated physical attacks during his years of nonviolent protests, and death threats against him were common. In his last public address, delivered at Memphis’ Mason Temple the day before his death, King alluded to his own mortality.

“Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land.”

Turning to today, Gordon-Reed said King would have been amazed by the Obama presidency, though unsurprised by the backlash against it.

“I would imagine he may also be surprised at how he has been embraced by so many different segments of society, for their own purposes,” she added, and “by the pace of social changes — the women’s movement, the movement for LGBTQ rights. And [that] the issue of race is not just a matter of black and white anymore.”

While much has changed for the better, Gordon-Reed said the economic advances King pressed for at the end of this life “have not come to fruition.”

“All available evidence indicates that communities of color still lag behind in terms of wealth,” she said. “The legacies of slavery, segregation, and the commitment to white supremacy have not yet been overcome. In fact, the issue of inequality is not just about race. The situation of organized labor — the weakening of unions overall — would have surprised him, I think. He thought that unions, along with working-class people of all colors, could cooperate to strike a blow on behalf of all marginalized people. That does not seem to be on the horizon.”

‘Leaders should not seek riches, fame, or even recognition for their efforts’

One of Shelby’s most powerful King moments was the first time he read “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.”

“It has so many important ethical lessons,” said the Caldwell Titcomb Professor of African and African American Studies and of Philosophy. “For instance, King argued that it is wrong to counsel the oppressed not to fight for their rights because this might provoke others to engage in violence or might create social strife. ‘Law and order’ and civil peace are not ends in themselves. They are means for establishing and maintaining just social conditions.”

Which of King’s beliefs would most surprise people today? Reparations are high on Shelby’s list.

In “Why We Can’t Wait” (1964), King wrote that while the cost made it “impossible to fully pay reparations to blacks for all the wrongs of slavery … compensation was due to the descendants of slaves for the unpaid toil of their ancestors.”

And King’s life still contains crucial lessons for those in charge today, said Shelby, co-editor of “To Shape a New World: Essays on the Political Philosophy of Martin Luther King Jr.”

“Leaders should not seek riches, fame, or even recognition for their efforts,” Shelby said. “They should see their vocation as one of service and sacrifice and should lead by example. This kind of leadership requires integrity, resilience, a willingness to speak hard truths in public, and most of all hope — the conviction that, through our determined efforts, we can make our world more peaceful and just.”

‘C ourage, endurance, moral clarity, and love’

With Harvard students on spring break the week of the assassination, King was remembered on Palm Sunday at Memorial Church. The Harvard Crimson’s Monday, April 8, edition ran a picture of the slain icon accompanied by an article headlined “Funeral, Sympathy March Draw Thousands to South.” The following day, President Nathan M. Pusey canceled morning and early afternoon classes to allow students to attend a special service in Memorial Church. The Harvard leader addressed the crowd during the somber ceremony.

“I do not know when the death of a private citizen has quickened such a universal response of grief and deprivation — nationwide and worldwide,” said Pusey. “Our grief is for the man and for the many unaccomplished things for which he worked and died.”

The impact of King’s death rippled through Commencement events. In March 1968, students had broken from tradition and directly invited the Class Day speaker. They selected King, whose speech, set for June 12, was expected to address the Vietnam War .

A year earlier King had registered his opposition to the conflict in a blistering New York speech that connected war, racism, and poverty. Congressman John Lewis of Georgia was in the audience that day. “I heard him speak so many times,” Lewis told The New Yorker in 2017 . “I still think this is probably the best.” (In a fitting turn, Lewis will be the principal speaker at the Afternoon Program of Harvard’s 367th Commencement on May 24. )

Her husband’s death still raw, Coretta Scott King agreed to speak in his place on Class Day. By then the nation was mourning another loss. Six days earlier Civil Rights advocate and presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy had been shot to death in Los Angeles.

“These two men addressed themselves to the burning issues of our times: They spoke out against great evils in our society: racism, poverty, and war,” King told seniors at Sanders Theatre. “They were great and effective actors on the stage of history. They played their parts exceedingly well, thus inspiring millions. They are a part of that creative minority which helped to move society forward.

“As young people, as students, your lives have been greatly affected by the loss of these champions of freedom, of justice, of human dignity and peace. In a power-drunk world, where means become ends, and violence becomes a favorite pastime, we are swiftly moving toward self-annihilation. Your generation must speak out with righteous indignation against the forces which are seeking to destroy us.”

Five decades removed from the grieving widow’s show of courage and resolve, Allen, the James Bryant Conant University Professor, will focus her address at Friday’s symposium on urging the same qualities upon a nation still struggling to live up to Martin Luther King Jr.’s highest hopes.

“The Civil Rights movement is far from done; the onward march of freedom still requires courage, endurance, moral clarity, and love,” Allen said. “I think we can best memorialize the men and women who worked with King, and King himself, by finding the courage to insist, over and over again and lovingly, on the ethical demands of full integration.”

Share this article

You might like.

Educators, activists explore peacebuilding based on shared desires for ‘freedom and equality and independence’ at Weatherhead panel

Former Palestinian Authority prime minister says strengthening execution of 1993 accords could lead to two-state solution

Political philosopher Harvey C. Mansfield says it all goes back to Aristotle, balance of competing ideas about common good

College accepts 1,937 to Class of 2028

Students represent 94 countries, all 50 states

Pushing back on DEI ‘orthodoxy’

Panelists support diversity efforts but worry that current model is too narrow, denying institutions the benefit of other voices, ideas

So what exactly makes Taylor Swift so great?

Experts weigh in on pop superstar's cultural and financial impact as her tours and albums continue to break records.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

The Institute cannot give permission to use or reproduce any of the writings, statements, or images of Martin Luther King, Jr. Please contact Intellectual Properties Management (IPM), the exclusive licensor of the Estate of Martin Luther King, Jr., Inc. at [email protected] or 404 526-8968. Screenshots are considered by the King Estate a ...

Martin Luther King, Jr. (born January 15, 1929, Atlanta, Georgia, U.S.—died April 4, 1968, Memphis, Tennessee) was a Baptist minister and social activist who led the civil rights movement in the United States from the mid-1950s until his death by assassination in 1968.

This edition of speeches, sermons, correspondence, and other papers of America’s foremost leader of the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. The project was initiated by the King Center in Atlanta before moving to the Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford. Seven completed volumes of a planned 14-volume ...

Statement on Research. As part of a long-term effort to preserve the historical legacy of the African- American freedom struggle, the Martin Luther King, Jr., Papers Project is preparing a definitive, multivolume edition of King's papers.'. King Project staff members and students at Stanford University, Emory University, and at the Martin ...

Early histories of the civil rights movement that appeared prior to the 1980s were primarily biographies of Martin Luther King, Jr. Collectively, these works helped to create the familiar “Montgomery to Memphis” narrative framework for understanding the history of the civil rights movement in the United States.

The Institute cannot give permission to use or reproduce any of the writings, statements, or images of Martin Luther King, Jr. Please contact Intellectual Properties Management (IPM), the exclusive licensor of the Estate of Martin Luther King, Jr., Inc. at [email protected] or 404 526-8968. Screenshots are considered by the King Estate a ...

Martin Luther King Jr, 1964. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons This definitive edition of Dr. King’s most significant speeches, sermons, correspondence, public statements, published writings and unpublished manuscripts documents King’s family roots, his rise to prominence, and influence as a national spokesperson for civil rights.

And King’s life still contains crucial lessons for those in charge today, said Shelby, co-editor of “To Shape a New World: Essays on the Political Philosophy of Martin Luther King Jr.” “Leaders should not seek riches, fame, or even recognition for their efforts,” Shelby said.