51 Constructive Feedback Examples for Students

Constructive feedback is feedback that helps students learn and grow.

Even though it highlights students’ weaknesses, it is not negative feedback because it has a purpose. It is designed to help them identify areas for improvement.

It serves both as an example of positive reinforcement and a reminder that there is always room for further improvement. Studies show that students generally like feedback that points them in the right direction and helps them to improve. It can also increase motivation for students.

Why Give Constructive Feedback?

Constructive feedback is given to help students improve. It can help people develop a growth mindset by helping them understand what they need to do to improve.

It can also help people to see that their efforts are paying off and that they can continue to grow and improve with continued effort.

Additionally, constructive feedback helps people to feel supported and motivated to keep working hard. It shows that we believe in their ability to grow and succeed and that we are willing to help them along the way.

How to Give Constructive Feedback

Generally, when giving feedback, it’s best to:

- Make your feedback specific to the student’s work

- Point out areas where the student showed effort and where they did well

- Offer clear examples of how to improve

- Be positive about the student’s prospects if they put in the hard work to improve

- Encourage the student to ask questions if they don’t understand your feedback

Furthermore, it is best to follow up with students to see if they have managed to implement the feedback provided.

General Constructive Feedback Examples for Students

The below examples are general templates that need to be edited so they are specific to the student’s work.

1. You are on the right track. By starting to study for the exam earlier, you may be able to retain more knowledge on exam day.

2. I have seen your improvement over time. As a next step, it is a good idea to…

3. You have improved a lot and should start to look towards taking on harder tasks for the future to achieve more self-development.

4. You have potential and should work on your weaknesses to achieve better outcomes. One area for improvement is…

5. Keep up the good work! You will see better results in the future if you make the effort to attend our study groups more regularly.

6. You are doing well, but there is always room for improvement. Try these tips to get better results: …

7. You have made some good progress, but it would be good to see you focusing harder on the assignment question so you don’t misinterpret it next time.

8. Your efforts are commendable, but you could still do better if you provide more specific examples in your explanations.

9. You have done well so far, but don’t become complacent – there is always room for improvement! I have noticed several errors in your notes, including…

10. It is great that you are trying your best, but don’t stop here – keep pushing yourself to get even better results. It would be good to see you editing your work to remove the small errors creeping into your work…

11. You have put in a lot of hard work, and it is starting to show. One area for improvement is your tone of voice, which sometimes comes across too soft. Don’t be afraid to project your voice next time.

12. You are making good progress, but don’t forget to focus on your weaknesses too. One weakness to focus on is…

13. Your efforts are commendable, but it would have been good to have seen you focus throughout as your performance waned towards the end of the session.

15. While your work is good, I feel you are becoming complacent – keep looking for ways to improve. For example, it would be good to see you concentrating harder on providing critique of the ideas explored in the class.

16. It is great that you are trying your best, but don’t stop here – keep pushing yourself to get even better results! Try to improve your handwriting by slowing down and focusing on every single letter.

17. You have put in a lot of hard work, and it is starting to show. Keep up the good work and you will see your grades slowly grow more and more. I’d like to see you improving your vocabulary for future pieces.

18. You are making good progress, but don’t forget to focus on your weaknesses too. One weakness to focus on is…

19. You have potential and should work on your using more appropriate sources to achieve better outcomes. As a next step, it is a good idea to…

Constructive Feedback for an Essay

1. Your writing style is good but you need to use more academic references in your paragraphs.

2. While you have reached the required word count, it would be good to focus on making sure every paragraph addresses the essay question.

3. You have a good structure for your essay, but you could improve your grammar and spelling.

4. You have made some good points, but you could develop them further by using more examples.

5. Your essay is well-written, but it would be helpful to provide more analysis of the topic.

6. You have answered the question well, but you could improve your writing style by being more concise.

7. Excellent job! You have covered all the key points and your writing is clear and concise.

8. There are a few errors in your essay, but overall it is well-written and easy to understand.

9. There are some mistakes in terms of grammar and spelling, but you have some good ideas worth expanding on.

10. Your essay is well-written, but it needs more development in terms of academic research and evidence.

11. You have done a great job with what you wrote, but you missed a key part of the essay question.

12. The examples you used were interesting, but you could have elaborated more on their relevance to the essay.

13. There are a few errors in terms of grammar and spelling, but your essay is overall well-constructed.

14. Your essay is easy to understand and covers all the key points, but you could use more evaluative language to strengthen your argument.

15. You have provided a good thesis statement , but the examples seem overly theoretical. Are there some practical examples that you could provide?

Constructive Feedback for Student Reports

1. You have worked very hard this semester. Next semester, work on being more consistent with your homework.

2. You have improved a lot this semester, but you need to focus on not procrastinating.

3. You are doing well in most subjects, but you could improve your grades by paying more attention in class and completing all your homework.

4. You are doing well in most subjects, but you could still improve your grades by studying more and asking for help when you don’t understand something.

5. You have shown great improvement this semester, keep up the good work! However, you might want to focus on improving your test scores by practicing more.

6. You have made some good progress this semester, but you need to continue working hard if you want to get good grades next year when the standards will rise again.

7. Next semester, focus on completing all your homework on time and paying more attention in class.

8. You have worked hard this semester, but you could still improve your grades by taking your time rather than racing through the work.

9. Next semester, focus on completing all your homework in advance so you have time to check it over before submission.

10. While you usually understand the instructions, don’t forget to ask for help when you don’t understand something rather than guessing.

11. You have shown great improvement this semester, but you need to focus some more on being self-motivated rather than relying on me to keep you on task.

Constructive feedback on Homework

1. While most of your homework is great, you missed a few points in your rush to complete it. Next time, slow down and make sure your work is thorough.

2. You put a lot of effort into your homework, and it shows. However, make sure to proofread your work for grammar and spelling mistakes.

3. You did a great job on this assignment, but try to be more concise in your writing for future assignments.

4. This homework is well-done, but you could have benefited from more time spent on research.

5. You have a good understanding of the material, but try to use more examples in your future assignments.

6. You completed the assignment on time and with great accuracy. I noticed you didn’t do the extension tasks. I’d like to see you challenging yourself in the future.

Related Articles

- Examples of Feedback for Teachers

- 75 Formative Assessment Examples

Giving and receiving feedback is an important part of any learning process. All feedback needs to not only grade work, but give advice on next steps so students can learn to be lifelong learners. By providing constructive feedback, we can help our students to iteratively improve over time. It can be challenging to provide useful feedback, but by following the simple guidelines and examples outlined in this article, I hope you can provide comments that are helpful and meaningful.

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 5 Top Tips for Succeeding at University

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 50 Durable Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 100 Consumer Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 30 Globalization Pros and Cons

2 thoughts on “51 Constructive Feedback Examples for Students”

Very helpful to see so much great developmental feedback with so many different examples.

Great examples of constructive feedback, also has reinforced on the current approach i take.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Classroom Q&A

With larry ferlazzo.

In this EdWeek blog, an experiment in knowledge-gathering, Ferlazzo will address readers’ questions on classroom management, ELL instruction, lesson planning, and other issues facing teachers. Send your questions to [email protected]. Read more from this blog.

Response: Ways to Give Effective Feedback on Student Writing

- Share article

This is the second post in a four-part series. You can see Part One here .)

The new question-of-the-week is:

What are the best ways to give students feedback on their writing?

Part One began with responses from Anabel Gonzalez, Sarah Woodard, Kim Jaxon, Ralph Fletcher, Mary Beth Nicklaus, and Leah Wilson. You can listen to a 10-minute conversation I had with Anabel, Sarah, and Kim on my BAM! Radio Show . You can also find a list of, and links to, previous shows here.

Today, Susan M. Brookhart, Cheryl Mizerny, Amy Benjamin, Kate Wolfe Maxlow, Karen Sanzo, Andrew Miller, David Campos, and Kathleen Fad share their commentaries.

Response From Susan M. Brookhart

Susan Brookhart, Ph.D., is the author of How to Use Grading to Improve Learning (ASCD 2017) and How to Give Effective Feedback to Your Students (2nd edition, ASCD 2017)). She is a professor emeritus at Duquesne University and an author and consultant. Her focus is classroom assessment and its impact on teaching, learning, and motivation:

Giving feedback on writing is a special responsibility. If you ask students to write thoughtfully to you, it would be hypocritical of you not to write (or speak, if your feedback is oral) thoughtfully back to them. And students will notice! Here are five things to keep in mind as you think about feedback on students’ written work:

#1 - Before the students write, make sure they know what they are trying to learn (more specifically than just “writing”) and what qualities their writing should exhibit. Unless students are trying to learn something specific, they will experience teacher feedback as additional teacher directions they have to follow. So, for example, if students are writing descriptive paragraphs, they should know what the kind of descriptive paragraphs they are aiming for looks like. Criteria for success might be that they (1) use adjectives that describe by telling what the object of their description looks, sounds, tastes, smells, or feels like; and (2) help their readers feel like they “are there,” experiencing whatever is described themselves. If this is what students are aiming to do, then the feedback questions are already set up: Are my adjectives descriptive? Do they conjure up sight, sound, taste, smell, or touch? Did you (my teacher and my reader) feel like you really experienced what I was describing, that you were there? The best feedback on student writing tells students what they want to know to get closer to the particular vision of writing they are working on.

#2 - Describe at least one thing the student did well, with reference to the success criteria. Focus your feedback on the criteria, not on other features of the work (like handwriting or grammar, unless that was the focus of the writing lesson). Even the poorest paper has something to commend it. Find that and begin your feedback there. Students can’t navigate toward learning targets by filling in deficits only; they also need to build on their strengths. And don’t assume that just because a student did something well, they know what that is. The best feedback on student writing names and notices where students are meeting criteria that show their learning.

#3 - Suggest the student’s immediate next steps, again with reference to the success criteria. Your feedback does not need to “fix” everything possible. It only needs to take the student’s work to the next level. Select the one or two—whatever is doable in the next draft of the writing piece—things that the student should do next, given where they are right now.The best feedback on student writing moves students forward in their quest to reach a learning goal.

#4 - Make sure you learn something from the feedback episode, too. Too often, teachers think of feedback as their expert advice on students’ writing. But every opportunity to give feedback on student writing is also an opportunity for you to learn something about what your students are thinking, what kinds of writing skills they have, and what they need to learn next. The best feedback on student writing gives teachers a window into student thinking; it doesn’t just advise students.

#5 - Give students an immediate opportunity to use the feedback. Much feedback on student writing is wasted, because students don’t use it. Many teachers subscribe to the myth that students will use the feedback “next time” they write something similar. However, it’s not true that students have some sort of file drawer in their heads, with files labeled according to type of writing, that they will magically open at some point in the future.

No matter how well-intentioned the student, this just isn’t how it works. The best feedback on student writing is followed immediately by a planned opportunity, within instructional time, for students to use the feedback.

Response From Cheryl Mizerny

Cheryl Mizerny has been teaching for more than 20 years, is passionate about middle-level education, and serves on the faculty of the AMLE Leadership Institute. Her practice is guided by her belief in reaching every student and educating the whole child. She currently teaches 6th grade English in Michigan and writes an education blog, “It’s Not Easy Being Tween,” for Middleweb.com:

Good feedback on student writing is time-consuming and takes a great deal of teacher effort, but the results in the improvement of their writing is worth my time. Over the years, I have found some ways to streamline the process.

First, students can’t hit a target they can’t see. Therefore, it is important that they have a clear understanding of the goal of the writing piece. I do lots of front-loading with using mentor texts to study author’s craft. Valuable feedback will tell them how close they are to the target and how they can get closer to a bullseye.

For me, the most important consideration when giving feedback is how likely is this to be used? Whenever possible, my first step is verbal feedback via an individual writing conference during the first draft stage. This lets me correct any major errors before they get too far along. We use Google docs so that they have access to them everywhere, I can see the revision history, and I am able to type my comments right in line with the text (which is faster and neater than my handwriting). Prior to writing my first comments, I have students identify a couple things on which they’d like me to focus when reading their paper. Just as I have goals for the final piece, so should they. Then, I begin the process of reading for feedback.

For me, I’ve found that feedback works best if it meets the following criteria: It’s prompt (not saying it has to be the next day, but students get very upset if they have to wait three weeks to get a draft back and rightly so), conversational and respectful in tone, specifically identifies areas for improvement and prioritizes them, focuses on larger issues such as content over small ones like punctuation, and is strengths-based with a balance of more positive than negative commentary. Feedback such as “Good job” is not helpful nor is “This is way too short.” Students needs specific information about how to make improvements if they are going to do so. If I have an especially weak piece, I don’t provide all the ways it can be improved via written feedback to avoid the child shutting down. That student obviously needs more assistance, and a conference is warranted. I am careful to address only a few areas of improvement per paper and I also comment on the areas in which they have a personal progress goal.

As they begin revising in class, I give some individual time to students to have a conversation about their work. The rest are looking at my comments and addressing each one or reading each other’s work. Prior to them handing in the second draft, I provide a checklist of things to consider and ask students to “whisper-read” to themselves (Google Docs has a screen reader built in) to find simple errors. Once they hand in this draft, I look at their work using a single-point rubric (see Jennifer Gonzalez article ) and make comments on it as a cover sheet. I hand this back without a grade on it. In my experience, once they see a grade, the learning stops. They then have one final pass to make any corrections before I receive the final. We also have a celebration of the writing and share work with one another. In my class, it’s is all about the writing process and not the product and this method works well for us.

Response From Amy Benjamin

Amy Benjamin is a teacher, educational consultant, and author whose most recent book is Big Skills for the Common Core (Routledge). Her website is www.amybenjamin.com :

Recently I asked a group of English and social studies teachers to list the marginal comments that they typically write on their students’ papers. Many of the comments were frowny-faced reprimands ending in exclamation points: “Check spelling! Be specific! Develop! Proofread! Follow directions! Review apostrophe use! Others were milder admonitions, often in the form of questions: Where’s your evidence? This shows what? Is this accurate? Punctuation?” Then there were suggestions that, though valid, are unlikely to do much good: “Be sure to support your claim, support the quote, make an inference, anchor the quote, connect to the question, elaborate meaning of quote, explain detail, review, set up the context for the claim, work on ‘tightening up’ your writing, follow the rubric.” The teacher knows what these comments mean, but do the students? Despite the inordinate amount of time it takes to pore over essays and write these comments, we have reason to suspect that they are not accomplishing their intended purposes, which are twofold: 1) to justify the grade on top of the paper, and 2) to get students to improve their writing. The second is far more important than the first. But if there’s no follow-up to our commentary, then what is the point? What are the best ways to give feedback that actually leads to improvement?

First, let’s consider the tone of our comments: While not all of the comments I collected were negative, most were. Some of the positive ones were “nicely written, well-supported, excellent topic sentence, insightful point, great evidence provided, good intro, good sentence, good use of vocab, love your voice, I love this point.” The best way to keep someone pursuing a challenge is to encourage them. It is not so hard to find something—anything—that merits a pat on the back.

Second, let’s consider the amount of correction that is necessary to foster incremental improvement. Teachers are not copy editors. The copy editor has not done her job unless she has found and fixed every single error . But a teacher’s job should be to point out errors and weaknesses sparingly, staying within what she perceives to be that student’s zone of proximal development. All students are novice writers. Their progress will be recursive. If they take risks to produce increasingly sophisticated language in an academic register, they are likely to make more grammatical mistakes, not fewer. One positive and one negative comment or correction on a student’s paper is probably sufficient to keep the writer on a learning curve.

Think of a child learning to play the saxophone. The child has practiced and plays the rehearsed piece for her weekly lesson. Imagine a music teacher responding like this: “I heard two squeaks, one wrong note, an underplayed dynamic at Letter C, a missed quarter rest on the fourth measure, and you completely ignored the dynamics. Watch your fingering, your breathing, and your posture. Pay attention to the time signature. While you’re at it, give it some feeling. It’s supposed to sound like music, not noise.”

And, third, consider the follow-up. Rubrics are excellent tools because they establish criteria for success and help students self-monitor. But the rubric has to be written in student-friendly language. With an accessible rubric, the student can chart her progress from one piece of writing to another. You can follow-up on a writing assignment with mini-lessons, using authentic sentences from student writing as models of good writing, not only deficient writing.

If you’d like students to take real responsibility for their own writing growth, you may be interested in a resource that I’ve created called RxEdit and RxRevise. There you will find a collection of DIY lessons keyed to various writing needs. You can refer students to these lessons on an as-needed basis. It’s a great way to differentiate instruction. RxEdit and RxRevise are available for free on my website .

Response From Kate Wolfe Maxlow & Karen Sanzo

Kate Wolfe Maxlow and Karen Sanzo’s are co-authors of 20 Formative Assessment Strategies that Work: A Guide Across Content and Grade Levels . Kate Wolfe Maxlow is the Professional Learning Coordinator at Hampton City Schools and Karen Sanzo is a professor of Educational Foundations and Leadership at Old Dominion University:

How many times in school did you write something that made perfect sense to you only to have your teacher or professor write a big, red question mark next to it? The purpose of writing is to communicate thoughts and ideas to an audience, but because the writer cannot simultaneously be both the author and the audience, young writers often require a great deal of feedback in order to learn how to write clearly for an intended audience. Therefore, it is immensely important that teachers provide quality, frequent feedback to students on their writing.

To this end, it is also important to remember that the role of the teacher is to help students improve, not necessarily to expect a perfect product. Marzano (2017) explains that educators “should view learning as a constructive process in which students constantly update their knowledge.” Likewise, Hattie (2017) emphasizes the importance of helping students to engage in metacognitive strategies, such as Planning and Prediction, Elaboration and Organization, and Evaluation and Reflection. When we think of writing as a constructive process in which we should help students engage in metacognitive strategies, we realize how crucial it is that we provide students with feedback throughout the entire writing process, not simply at the end.

What does this look like? Imagine that you give students the following prompt: Explain why we remember George Washington today. Before students begin to write, have them make a plan that includes how they will conduct research, what questions they will ask, and how they will record answers. Check in with each student and then—this is key—provide feedback on their plans. As students begin to implement their plan and conduct research, collect information, and outline their paper, provide feedback on that, too.

What form does that feedback take? Well, whether it’s electronic (such as using Google Docs), verbal, or written doesn’t matter as much as the kind of thinking that the teacher asks the student to do when providing the feedback. For instance, a student has to do less work and actually learns less when a teacher writes, “George Washington did not have wooden teeth,” than if the teacher writes, “Can you find other sources that confirm that George Washington had wooden teeth?” or even “George Washington’s teeth are indeed an interesting subject; do you think we would remember him even if he had his own teeth based on his other accomplishments? What are the biggest reasons we remember him today?”

Feedback can, of course, also concern writing style. If feedback is too prescribed, we cheat students out of critical- and creative-thinking opportunities; if it is too vague, we risk frustrating them. For instance, instead of simply writing, “Vary your sentence style,” when a student starts each sentence in a paragraph with, “We remember George Washington because...,” a teacher could ask, “How can you start each sentence differently in this paragraph to keep the reader’s attention?” This points students in the right direction and also helps them understand why the change is important.

Lastly, while it’s important to give students feedback on their writing, feedback works best when we also collect it from students (Hattie, 2009). The more we ask students to self-evaluate and reflect on their work, the greater the impact on their achievement (Hattie, 2017). To that end, it can work well to have students first self-evaluate their writing using the rubric then come to a writing conference prepared with examples of what’s working in their paper and where they need help. When we give feedback like this, we encourage students not only to become better writers, but better thinkers as well.

Hattie, J (2009). Visible Learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. New York: Routledge

Hattie, J. (2017). Hattie’s 2017 updated list of factors influencing student achievement. Retrieved from https://www.visiblelearningplus.com/sites/default/files/250%20Influences.pdf

Marzano (2017). The New Art and Science of Teaching. Bloomington, IN: ASCD & Solution Tree Press.

Response From Andrew Miller

Andrew Miller is currently an instructional coach at the Shanghai American School in China. He also serves on the National Faculty for the Buck Institute for Education and ASCD, where he consults on a variety of topics. He has worked with educators in the United States, Canada, Mexico, Australia, Thailand, Vietnam, Singapore, the Philippines, China, Japan, Indonesia, India, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, and the Dominican Republic:

Because we care about our students, we often do two things wrong: We give too much feedback or we tell students the answer in the feedback. Too much feedback is often ground in the traditional “final draft” way of writing, where the teacher collects the papers and then spends hours marking and providing written feedback near the end of the unit and close to when the assignment is due. This is often too much for students to process and/or can be too late. “Why didn’t you tell me my opening paragraph needed work when I wrote it a week ago?” Instead, teachers should provide feedback in smaller chunks in a more ongoing way. This makes the feedback manageable and timely.

For the second problem, teachers should focus on prompting and asking good questions to probe student thinking in the feedback they write. Instead of correcting a large amount of punctuation errors for students, write: “I’m noticing errors in comma and other punctuation usage in your second paragraph.” Here, the student must seek out those errors and correct them. They must learn! If the teacher does all the corrections for the students, then that teacher has done all the thinking for the student. In fact, it may have robbed that student of an opportunity to learn. Feedback should cause students to think and learn, not give away all the answers.

One final rule—don’t give feedback unless you can devote time for students to use and process it. We’ve all made the mistakes where we give feedback on the summative assessment and then students don’t use it. This is because we have indicated to them that it is summative and it is too late to improve. Teachers waste their time, and students don’t find value in the feedback.

Response From David Campos & Kathleen Fad

David Campos, Ph.D., is a professor of education at the University of the Incarnate Word in San Antonio, Texas, where he teaches undergraduate and graduate courses in special education, multicultural education, and instructional design and delivery. He has written books on LGBT youth, childhood health and wellness, and the schooling of Latinos. He has co-authored two books with Kathleen Fad: Tools for Teaching Writing (ASCD 2014) and Practical Ideas That Really Work for English Language Learners (Pro-Ed).

Kathleen Fad, Ph.D., is an author and consultant whose professional experience has spanned more than 30 years as a general education teacher, special education teacher, and university professor. Kathy’s specialty is designing practical, common-sense strategies that are research-based:

We also consider the idea of giving feedback from the special education perspective, and, that is, giving feedback so that it is individualized. Our experiences have taught us that in any given classroom, many students may struggle with the same writing issues, but most will have unique difficulties with their writing.

To help teachers give effective feedback on student writing, we created an evaluation protocol based on eight writing traits (in Tools for Teaching Writing, ASCD). Teachers can use this protocol to isolate the areas of writing that individual students struggle with the most. We identified qualities associated with each trait, which provides the teacher with a common language to use when she conferences with individual students.

Teachers can similarly create their own evaluation measure that has qualities associated with the traits or conventions of writing they address in their lessons. For example, teachers can ask themselves, “How does good presentation manifest in student writing?” Then, they can work toward developing the qualities of presentation they can regularly use in their instruction and student feedback. The key to effective feedback is to give students concrete qualities about the writing trait or convention and use those regularly in their conferences with students.

After teachers have developed this common language about writing, students can learn to self-reflect on their work. As a way of giving feedback, teachers can provide students with checklists associated with the qualities of the trait and have the students self-reflect or review their peers’ writing.

Thanks to Susan, Cheryl, Amy, Kate, Karen, Andrew, David, and Kathleen for their contributions.

Please feel free to leave a comment with your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at [email protected] . When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at @Larryferlazzo .

Education Week has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled Classroom Management Q&As: Expert Strategies for Teaching .

Just a reminder—you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via email or RSS Reader. And if you missed any of the highlights from the first seven years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below. The list doesn’t include ones from this current year, but you can find those by clicking on the “answers” category found in the sidebar.

This Year’s Most Popular Q&A Posts

Race & Gender Challenges

Classroom Management Advice

Best Ways to Begin The School Year

Best Ways to End The School Year

Implementing the Common Core

Student Motivation & Social-Emotional Learning

Teaching Social Studies

Project-Based Learning

Using Tech in the Classroom

Parent Engagement in Schools

Teaching English-Language Learners

Reading Instruction

Writing Instruction

Education Policy Issues

Student Assessment

Differentiating Instruction

Math Instruction

Science Instruction

Advice for New Teachers

Author Interviews

Entering the Teaching Profession

The Inclusive Classroom

Learning & the Brain

Administrator Leadership

Teacher Leadership

Relationships in Schools

Professional Development

Instructional Strategies

Best of Classroom Q&A

I am also creating a Twitter list including all contributers to this column .

Look for Part Three in a few days.

The opinions expressed in Classroom Q&A With Larry Ferlazzo are strictly those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions or endorsement of Editorial Projects in Education, or any of its publications.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Places on our 2024 summer school are filling fast. Don’t miss out. Enrol now to avoid disappointment

- 10 Types of Essay Feedback and How to Respond to Them

The moment of truth has arrived: you’ve got your marked essay back and you’re eagerly scanning through it, taking in the amount of red pen, and looking at the grade and hastily scrawled feedback at the end.

You should also read…

- The Complete Guide to Research Skills for Essay-Writing

- How to Write Dazzlingly Brilliant Essays

After deciphering the handwriting, you’re able to see a brief assessment of how you’ve performed in this essay, and your heart either leaps or sinks. Ideally, you’d receive detailed feedback telling you exactly where you fell short and providing helpful guidance on how to improve next time. However, the person marking your essay probably doesn’t have time for that, so instead leaves you very brief remarks that you then have to decode in order to understand how you can do better. In this article, we look at some of the common sorts of remarks you might receive in essay feedback, what they mean, and how to respond to them or take them on board so that you can write a better essay next time – no matter how good this one was!

1. “Too heavily reliant on critics”

We all fall into the trap of regurgitating whatever scholarship we happen to have read in the run-up to writing the essay, and it’s a problem that reveals that many students have no idea what their own opinion is. We’re so busy paraphrasing what scholars have said that we forget to think about whether we actually agree with what they’ve said. This is an issue we discussed in a recent article on developing your own opinion , in which we talked about how to approach scholarship with an open and critical mind, make up your own mind and give your own opinion in your essays. If you’ve received this kind of feedback, the person marking your essay has probably noticed that you’ve followed exactly the same line of thinking as one or more of the books on your reading list, without offering any kind of original comment. Take a look at the article linked to just now and you’ll soon be developing your own responses.

2. “Too short”

If your essay falls significantly short of the prescribed word count, this could suggest that you haven’t put in enough work. Most essays will require extensive reading before you can do a topic justice, and if you’ve struggled to fill the word count, it’s almost certainly because you haven’t done enough reading, and you’ve therefore missed out a significant line of enquiry. This is perhaps a sign that you’ve left it too late to write your essay, resulting in a rushed and incomplete essay (even if you consider it finished, it’s not complete if it hasn’t touched on topics of major relevance). This problem can be alleviated by effective time management, allowing plenty of time for the research phase of your essay and then enough time to write a detailed essay that touches on all the important arguments. If you’re struggling to think of things to say in your essay, try reading something on the topic that you haven’t read before. This will offer you a fresh perspective to talk about, and possibly help you to understand the topic clearly enough to start making more of your own comments about it.

3. “Too long”

[pullquote] “The present letter is a very long one, simply because I had no leisure to make it shorter” – Blaise Pascal [/pullquote]It sounds counter-intuitive, but it’s actually much easier to write an essay that’s too long than one that’s too short. This is because we’re all prone to waffling when we’re not entirely sure what we want to say, and/or because we want to show the person marking our essay that we’ve read extensively, even when some of the material we’ve read isn’t strictly relevant to the essay question we’ve been set. But the word count is there for a reason: it forces you to be clear and concise, leaving out what isn’t relevant. A short (say, 500-word) essay is actually a challenging academic exercise, so if you see fit to write twice the number of words, the person marking the essay is unlikely to be impressed. Fifty to a hundred words over the limit probably won’t be too much of an issue if that’s less than 10% of the word count, and will probably go unnoticed, but if you’ve ended up with something significantly over this, it’s time to start trimming. Re-read what you’ve written and scrutinise every single line. Does it add anything to your argument? Are you saying in ten words what could be said in three? Is there a whole paragraph that doesn’t really contribute to developing your argument? If so, get rid of it. This kind of ruthless editing and rephrasing can quickly bring your word count down, and it results in a much tighter and more carefully worded essay.

4. “Contradicts itself”

Undermining your own argument is an embarrassing mistake to make, but you can do it without realising when you’ve spent so long tweaking your essay that you can no longer see the wood for the trees. Contradicting yourself in an essay is also a sign that you haven’t completely understood the issues and haven’t formed a clear opinion on what the evidence shows. To avoid this error, have a detailed read through your essay before you submit it and look in particular detail at the statements you make. Looking at them in essence and in isolation, do any of them contradict each other? If so, decide which you think is more convincing and make your argument accordingly.

5. “Too many quotations”

It’s all too easy to hide behind the words of others when one is unsure of something, or lacking a complete understanding of a topic. This insecurity leads us to quote extensively from either original sources or scholars, including long chunks of quoted text as a nifty way of upping the word count without having to reveal our own ignorance (too much). But you won’t fool the person marking your essay by doing this: they’ll see immediately that you’re relying too heavily on the words of others, without enough intelligent supporting commentary, and it’s particularly revealing when most of the quotations are from the same source (which shows that you haven’t read widely enough). It’s good to include some quotations from a range of different sources, as it adds colour to your essay, shows that you’ve read widely and demonstrates that you’re thinking about different kinds of evidence. However, if you’ve received this kind of feedback, you can improve your next essay by not quoting more than a sentence at a time, making the majority of the text of your essay your own words, and including plenty of your own interpretation and responses to what you’ve quoted. Another word of advice regarding quotations: one of my tutors once told me is that one should never end an essay on a quotation. You may think that this is a clever way of bringing your essay to a conclusion, but actually you’re giving the last word to someone else when it’s your essay, and you should make the final intelligent closing remark. Quoting someone else at the end is a cop-out that some students use to get out of the tricky task of writing a strong final sentence, so however difficult the alternative may seem, don’t do it!

6. “Not enough evidence”

In an essay, every point you make must be backed up with supporting evidence – it’s one of the fundamental tenets of academia. You can’t make a claim unless you can show what has lead you to it, whether that’s a passage in an original historical source, the result of some scientific research, or any other form of information that would lend credibility to your statement. A related problem is that some students will quote a scholar’s opinion as though it were concrete evidence of something; in fact, that is just one person’s opinion, and that opinion has been influenced by the scholar’s own biases. The evidence they based the opinion on might be tenuous, so it’s that evidence you should be looking at, not the actual opinion of the scholar themselves. As you write your essay, make a point of checking that everything you’ve said is adequately supported.

7. “All over the place” / “Confused”

An essay described as “all over the place” – or words to that effect – reveals that the student who wrote it hasn’t developed a clear line of argument, and that they are going off at tangents and using an incoherent structure in which one point doesn’t seem to bear any relation to the previous one. A tight structure is vital in essay-writing, as it holds the reader’s interest and helps build your argument to a logical conclusion. You can avoid your essay seeming confused by writing an essay plan before you start. This will help you get the structure right and be clear about what you want to say before you start writing.

8. “Misses the point”

This feedback can feel particularly damning if you’ve spent a long time writing what you thought was a carefully constructed essay. A simple reason might be that you didn’t read the question carefully enough. But it’s also a problem that arises when students spend too long looking at less relevant sources and not enough at the most important ones, because they ran out of time, or because they didn’t approach their reading lists in the right order, or because they failed to identify correctly which the most important sources actually were. This leads to students focusing on the wrong thing, or perhaps getting lost in the details. The tutor marking the essay, who has a well-rounded view of the topic, will be baffled if you’ve devoted much of your essay to discussing something you thought was important, but which they know to be a minor detail when compared with the underlying point. If you’re not sure which items on your reading list to tackle first, you could try asking your tutor next time if they could give you some pointers on which of the material they recommend you focus on first. It can also be helpful to prompt yourself from time to time with the question “What is the point?”, as this will remind you to take a step back and figure out what the core issues are.

9. “Poor presentation”

This kind of remark is likely to refer to issues with the formatting of your essay, spelling and punctuation , or general style. Impeccable spelling and grammar are a must, so proofread your essay before you submit it and check that there are no careless typos (computer spell checks don’t always pick these up). In terms of your writing style , you might get a comment like this if the essay marker found your writing either boring or in a style inappropriate to the context of a formal essay. Finally, looks matter: use a sensible, easy-to-read font, print with good-quality ink and paper if you’re printing, and write neatly and legibly if you’re handwriting. Your essay should be as easy to read as possible for the person marking it, as this lessens their workload and makes them feel more positively towards your work.

10. “Very good”

On the face of it, this is the sort of essay feedback every student wants to hear. But when you think about it, it’s not actually very helpful – particularly when it’s accompanied by a mark that wasn’t as high as you were aiming for. With these two words, you have no idea why you didn’t achieve top marks. In the face of such (frankly lazy) marking from your teacher or lecturer, the best response is to be pleased that you’ve received a positive comment, but to go to the person who marked it and ask for more comments on what you could have done to get a higher mark. They shouldn’t be annoyed at your asking, because you’re simply striving to do better every time.

General remarks on responding to essay feedback

We end with a few general pieces of advice on how to respond to essay feedback.

- Don’t take criticism personally.

- Remember that feedback is there to help you improve.

- Don’t be afraid to ask for more feedback if what they’ve said isn’t clear.

- Don’t rest on your laurels – if you’ve had glowing feedback, it’s still worth asking if there’s anything you could have done to make the essay even better.

It can be difficult to have one’s hard work (metaphorically) ripped apart or disparaged, but feedback is ultimately there to help you get higher grades, get into better universities, and put you on a successful career path; so keep that end goal in mind when you get your essay back.

Image credits: banner ; library ; snake ; magnifying glass ; dartboard ; suggestions box .

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How to Give Feedback on an Essay

4-minute read

- 9th May 2019

Whether you’re teaching or just helping a friend, being asked to offer feedback on an essay can be intimidating if you’ve not done it before. We do, though, have a few tips to share on this subject.

Content vs. Quality of Writing

There are two main things you may want to offer feedback on when reading an essay. These are:

- The content of the essay (i.e. what the author is arguing)

- How it is written (i.e. how well they communicate their argument)

The exact nature of the feedback you provide will depend on the topic and type of essay you are reading. But there are some things you might want to comment on for any paper, including:

- Spelling, grammar and punctuation errors

- Overall structure and readability

- Academic vocabulary and writing style

- Factual inaccuracies or ambiguities

- Whether the author provides evidence for their arguments

- Clarity and consistency of referencing

Ideally, you’ll provide feedback on all of these. However, if you’re simply reading the first draft of a paper to help a friend, you may want to check what kind of feedback they want.

Try, too, to balance the positive and negative feedback. It’s just as important to note things that are good as things that need clarifying. After all, if the author sees nothing but negative comments, they could be discouraged. Positive feedback, on the other hand, is a great motivator.

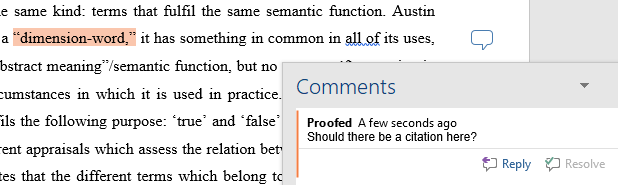

Comments in Margins vs. In-Depth Feedback

One way of leaving feedback is to make notes in the margins (either on paper or using the comment function in Microsoft Word). These should be short notes related to a specific issue, such as highlighting a misspelled word, an incorrect fact, or a missing citation.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Try not to leave too many comments in the margins, though. If there is a recurring problem, such as a word that the author has repeatedly misspelled, don’t comment on it every time. Instead, leave a comment noting the pattern of errors. This highlights the issue without overwhelming the reader.

You may also want to provide overall feedback at the end of the paper. Ideally, this in-depth feedback should:

- Start positive (e.g. This is a well-researched, well-organised paper ).

- Focus on one or two major issues rather than repeating everything you commented on in the margins. If there are too many big problems to pick one or two, you may want to speak to the author in person instead.

- Provide concrete criticism on specific problems, including page or section numbers where relevant, not just general criticisms (e.g. You are missing several citations in section three, so please check… rather than The referencing in this paper could be improved… ).

If you’re offering feedback on an essay that is currently in progress, focus on issues that the author could improve in the next draft. If you’re marking a final draft, however, you may want to focus on what they can learn from the essay’s overall strengths and weaknesses.

Marking Criteria

Finally, if you’re teaching on a university course – or even just marking papers – you should have access to the marking criteria. These will be set by the university or whoever is teaching the class. And, crucially, these guidelines will set out in detail what a good paper should do.

These criteria can also be useful when planning a paper, so it’s worth asking about the marking criteria even if you’re writing an essay rather than offering feedback! And if you’re not sure where to find the marking criteria for your course, check the university website or ask your professor.

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Get help from a language expert. Try our proofreading services for free.

2-minute read

How to Cite the CDC in APA

If you’re writing about health issues, you might need to reference the Centers for Disease...

5-minute read

Six Product Description Generator Tools for Your Product Copy

Introduction If you’re involved with ecommerce, you’re likely familiar with the often painstaking process of...

3-minute read

What Is a Content Editor?

Are you interested in learning more about the role of a content editor and the...

The Benefits of Using an Online Proofreading Service

Proofreading is important to ensure your writing is clear and concise for your readers. Whether...

6 Online AI Presentation Maker Tools

Creating presentations can be time-consuming and frustrating. Trying to construct a visually appealing and informative...

What Is Market Research?

No matter your industry, conducting market research helps you keep up to date with shifting...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

Getting Feedback

What this handout is about.

Sometimes you’d like feedback from someone else about your writing, but you may not be sure how to get it. This handout describes when, where, how and from whom you might receive effective responses as you develop as a writer.

Why get feedback on your writing?

You’ll become a better writer, and writing will become a less painful process. When might you need feedback? You might be just beginning a paper and want to talk to someone else about your ideas. You might be midway through a draft and find that you are unsure about the direction you’ve decided to take. You might wonder why you received a lower grade than you expected on a paper, or you might not understand the comments that a TA or professor has written in the margins. Essentially, asking for feedback at any stage helps you break out of the isolation of writing. When you ask for feedback, you are no longer working in a void, wondering whether or not you understand the assignment and/or are making yourself understood. By seeking feedback from others, you are taking positive, constructive steps to improve your own writing and develop as a writer.

Why people don’t ask for feedback

- You worry that the feedback will be negative. Many people avoid asking others what they think about a piece of writing because they have a sneaking suspicion that the news will not be good. If you want to improve your writing, however, constructive criticism from others will help. Remember that the criticism you receive is only criticism of the writing and not of the writer.

- You don’t know whom to ask. The person who can offer the most effective feedback on your writing may vary depending on when you need the feedback and what kind of feedback you need. Keep in mind, though, that if you are really concerned about a piece of writing, almost any thoughtful reader (e.g., your roommate, mother, R.A., brother, etc.) can provide useful feedback that will help you improve your writing. Don’t wait for the expert; share your writing often and with a variety of readers.

- You don’t know how to ask. It can be awkward to ask for feedback, even if you know whom you want to ask. Asking someone, “Could you take a look at my paper?” or “Could you tell me if this is OK?” can sometimes elicit wonderfully rich responses. Usually, though, you need to be specific about where you are in the writing process and the kind of feedback that would help. You might say, “I’m really struggling with the organization of this paper. Could you read these paragraphs and see if the ideas seem to be in the right order?”

- You don’t want to take up your teacher’s time. You may be hesitant to go to your professor or TA to talk about your writing because you don’t want to bother him or her. The office hours that these busy people set aside, though, are reserved for your benefit, because the teachers on this campus want to communicate with students about their ideas and their work. Faculty can be especially generous and helpful with their advice when you drop by their office with specific questions and know the kinds of help you need. If you can’t meet during the instructor’s office hours, try making a special appointment. If you find that you aren’t able to schedule a time to talk with your instructor, remember that there are plenty of other people around you who can offer feedback.

- You’ve gotten feedback in the past that was unhelpful. If earlier experiences haven’t proved satisfactory, try again. Ask a different person, or ask for feedback in a new way. Experiment with asking for feedback at different stages in the writing process: when you are just beginning an assignment, when you have a draft, or when you think you are finished. Figure out when you benefit from feedback the most, the kinds of people you get the best feedback from, the kinds of feedback you need, and the ways to ask for that feedback effectively.

- You’re working remotely and aren’t sure how to solicit help. Help can feel “out of sight, out of mind” when working remotely, so it may take extra effort and research to reach out. Explore what resources are available to you and how you can access them. What type of remote feedback will benefit you most? Video conferencing, email correspondence, phone conversation, written feedback, or something else? Would it help to email your professor or TA ? Are you looking for the back and forth of a real-time conversation, or would it be more helpful to have written feedback to refer to as you work? Can you schedule an appointment with the Writing Center or submit a draft for written feedback ? Could joining or forming an online writing group help provide a source of feedback?

Possible writing moments for feedback

There is no “best time” to get feedback on a piece of writing. In fact, it is often helpful to ask for feedback at several different stages of a writing project. Listed below are some parts of the writing process and some kinds of feedback you might need in each. Keep in mind, though, that every writer is different—you might think about these issues at other stages of the writing process, and that’s fine.

- The beginning/idea stage: Do I understand the assignment? Am I gathering the right kinds of information to answer this question? Are my strategies for approaching this assignment effective ones? How can I discover the best way to develop my early ideas into a feasible draft?

- Outline/thesis: I have an idea about what I want to argue, but I’m not sure if it is an appropriate or complete response to this assignment. Is the way I’m planning to organize my ideas working? Does it look like I’m covering all the bases? Do I have a clear main point? Do I know what I want to say to the reader?

- Rough draft: Does my paper make sense, and is it interesting? Have I proven my thesis statement? Is the evidence I’m using convincing? Is it explained clearly? Have I given the reader enough information? Does the information seem to be in the right order? What can I say in my introduction and conclusion?

- Early polished draft: Are the transitions between my ideas smooth and effective? Do my sentences make sense individually? How’s my writing style?

- Late or final polished draft: Are there any noticeable spelling or grammar errors? Are my margins, footnotes, and formatting okay? Does the paper seem effective? Is there anything I should change at the last minute?

- After the fact: How should I interpret the comments on my paper? Why did I receive the grade I did? What else might I have done to strengthen this paper? What can I learn as a writer about this writing experience? What should I do the next time I have to write a paper?

A note on asking for feedback after a paper has been graded

Many people go to see their TA or professor after they receive a paper back with comments and a grade attached. If you seek feedback after your paper is returned to you, it makes sense to wait 24 hours before scheduling a meeting to talk about it. If you are angry or upset about a grade, the day off gives you time to calm down and put things in perspective. More important, taking a day off allows you to read through the instructor’s comments and think about why you received the grade that you did. You might underline or circle comments that were confusing to you so that you can ask about them later. You will also have an opportunity to reread your own writing and evaluate it more critically yourself. After all, you probably haven’t seen this piece of work since you handed it in a week or more ago, and refreshing your memory about its merits and weaknesses might help you make more sense of the grade and the instructor’s comments.

Also, be prepared to separate the discussion of your grade from the discussion of your development as a writer. It is difficult to have a productive meeting that achieves both of these goals. You may have very good reasons for meeting with an instructor to argue for a better grade, and having that kind of discussion is completely legitimate. Be very clear with your instructor about your goals. Are you meeting to contest the grade your paper received and explain why you think the paper deserved a higher one? Are you meeting because you don’t understand why your paper received the grade it did and would like clarification? Or are you meeting because you want to use this paper and the instructor’s comments to learn more about how to write in this particular discipline and do better on future written work? Being up front about these distinctions can help you and your instructor know what to expect from the conference and avoid any confusion between the issue of grading and the issue of feedback.

Kinds of feedback to ask for

Asking for a specific kind of feedback can be the best way to get advice that you can use. Think about what kinds of topics you want to discuss and what kinds of questions you want to ask:

- Understanding the assignment: Do I understand the task? How long should it be? What kinds of sources should I be using? Do I have to answer all of the questions on the assignment sheet or are they just prompts to get me thinking? Are some parts of the assignment more important than other parts?

- Factual content: Is my understanding of the course material accurate? Where else could I look for more information?

- Interpretation/analysis: Do I have a point? Does my argument make sense? Is it logical and consistent? Is it supported by sufficient evidence?

- Organization: Are my ideas in a useful order? Does the reader need to know anything else up front? Is there another way to consider ordering this information?

- Flow: Do I have good transitions? Does the introduction prepare the reader for what comes later? Do my topic sentences accurately reflect the content of my paragraphs? Can the reader follow me?

- Style: Comments on earlier papers can help you identify writing style issues that you might want to look out for. Is my writing style appealing? Do I use the passive voice too often? Are there too many “to be” verbs?

- Grammar: Just as with style, comments on earlier papers will help you identify grammatical “trouble spots.” Am I using commas correctly? Do I have problems with subject-verb agreement?

- Small errors: Is everything spelled right? Are there any typos?

Possible sources of feedback and what they’re good for

Believe it or not, you can learn to be your own best reader, particularly if you practice reading your work critically. First, think about writing problems that you know you have had in the past. Look over old papers for clues. Then, give yourself some critical distance from your writing by setting it aside for a few hours, overnight, or even for a couple of days. Come back to it with a fresh eye, and you will be better able to offer yourself feedback. Finally, be conscious of what you are reading for. You may find that you have to read your draft several times—perhaps once for content, once for organization and transitions, and once for style and grammar. If you need feedback on a specific issue, such as passive voice, you may need to read through the draft one time alone focusing on that issue. Whatever you do, don’t count yourself out as a source of feedback. Remember that ultimately you care the most and will be held responsible for what appears on the page. It’s your paper.

A classmate (a familiar and knowledgeable reader)

When you need feedback from another person, a classmate can be an excellent source. A classmate knows the course material and can help you make sure you understand the course content. A classmate is probably also familiar with the sources that are available for the class and the specific assignment. Moreover, you and your classmates can get together and talk about the kinds of feedback you both received on earlier work for the class, building your knowledge base about what the instructor is looking for in writing assignments.

Your TA (an expert reader)

Your TA is an expert reader—he or she is working on an advanced degree, either a Master’s or a Ph.D., in the subject area of your paper. Your TA is also either the primary teacher of the course or a member of the teaching team, so he or she probably had a hand in selecting the source materials, writing the assignment, and setting up the grading scheme. No one knows what the TA is looking for on the paper better than the TA , and most of the TAs on campus would be happy to talk with you about your paper.

Your professor (a very expert reader)

Your professor is the most expert reader you can find. He or she has a Ph.D. in the subject area that you are studying, and probably also wrote the assignment, either alone or with help from TAs. Like your TA, your professor can be the best source for information about what the instructor is looking for on the paper and may be your best guide in developing into a strong academic writer.

Your roommate/friend/family member (an interested but not familiar reader)

It can be very helpful to get feedback from someone who doesn’t know anything about your paper topic. These readers, because they are unfamiliar with the subject matter, often ask questions that help you realize what you need to explain further or that push you to think about the topic in new ways. They can also offer helpful general writing advice, letting you know if your paper is clear or your argument seems well organized, for example. Ask them to read your paper and then summarize for you what they think its main points are.

The Writing Center (an interested but not familiar reader with special training)

While the Writing Center staff may not have specialized knowledge about your paper topic, our writing coaches are trained to assist you with your writing needs. We cannot edit or proofread for you, but we can help you identify problems and address them at any stage of the writing process. The Writing Center’s coaches see thousands of students each year and are familiar with all kinds of writing assignments and writing dilemmas.

Other kinds of resources

If you want feedback on a writing assignment and can’t find a real live person to read it for you, there are other places to turn. Check out the Writing Center’s handouts . These resources can give you tips for proofreading your own work, making an argument, using commas and transitions, and more. You can also try the spell/grammar checker on your computer. This shouldn’t be your primary source of feedback, but it may be helpful.

A word about feedback and plagiarism

Asking for help on your writing does not equal plagiarism, but talking with classmates about your work may feel like cheating. Check with your professor or TA about what kinds of help you can get legally. Most will encourage you to discuss your ideas about the reading and lectures with your classmates. In general, if someone offers a particularly helpful insight, it makes sense to cite him or her in a footnote. The best way to avoid plagiarism is to write by yourself with your books closed. (For more on this topic, see our handout on plagiarism .)

What to do with the feedback you get

- Don’t be intimidated if your professor or TA has written a lot on your paper. Sometimes instructors will provide more feedback on papers that they believe have a lot of potential. They may have written a lot because your ideas are interesting to them and they want to see you develop them to their fullest by improving your writing.

- By the same token, don’t feel that your paper is garbage if the instructor DIDN’T write much on it. Some graders just write more than others do, and sometimes your instructors are too busy to spend a great deal of time writing comments on each individual paper.

- If you receive feedback before the paper is due, think about what you can and can’t do before the deadline. You sometimes have to triage your revisions. By all means, if you think you have major changes to make and you have time to make them, go for it. But if you have two other papers to write and all three are due tomorrow, you may have to decide that your thesis or your organization is the biggest issue and just focus on that. The paper might not be perfect, but you can learn from the experience for the next assignment.

- Read ALL of the feedback that you get. Many people, when receiving a paper back from their TA or professor, will just look at the grade and not read the comments written in the margins or at the end of the paper. Even if you received a satisfactory grade, it makes sense to carefully read all of the feedback you get. Doing so may help you see patterns of error in your writing that you need to address and may help you improve your writing for future papers and for other classes.

- If you don’t understand the feedback you receive, by all means ask the person who offered it. Feedback that you don’t understand is feedback that you cannot benefit from, so ask for clarification when you need it. Remember that the person who gave you the feedback did so because they genuinely wanted to convey information to you that would help you become a better writer. They wouldn’t want you to be confused and will be happy to explain their comments further if you ask.

- Ultimately, the paper you will turn in will be your own. You have the final responsibility for its form and content. Take the responsibility for being the final judge of what should and should not be done with your essay.

- Just because someone says to change something about your paper doesn’t mean you should. Sometimes the person offering feedback can misunderstand your assignment or make a suggestion that doesn’t seem to make sense. Don’t follow those suggestions blindly. Talk about them, think about other options, and decide for yourself whether the advice you received was useful.

Final thoughts

Finally, we would encourage you to think about feedback on your writing as a way to help you develop better writing strategies. This is the philosophy of the Writing Center. Don’t look at individual bits of feedback such as “This paper was badly organized” as evidence that you always organize ideas poorly. Think instead about the long haul. What writing process led you to a disorganized paper? What kinds of papers do you have organization problems with? What kinds of organization problems are they? What kinds of feedback have you received about organization in the past? What can you do to resolve these issues, not just for one paper, but for all of your papers? The Writing Center can help you with this process. Strategy-oriented thinking will help you go from being a writer who writes disorganized papers and then struggles to fix each one to being a writer who no longer writes disorganized papers. In the end, that’s a much more positive and permanent solution.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Additional menu

Khan Academy Blog

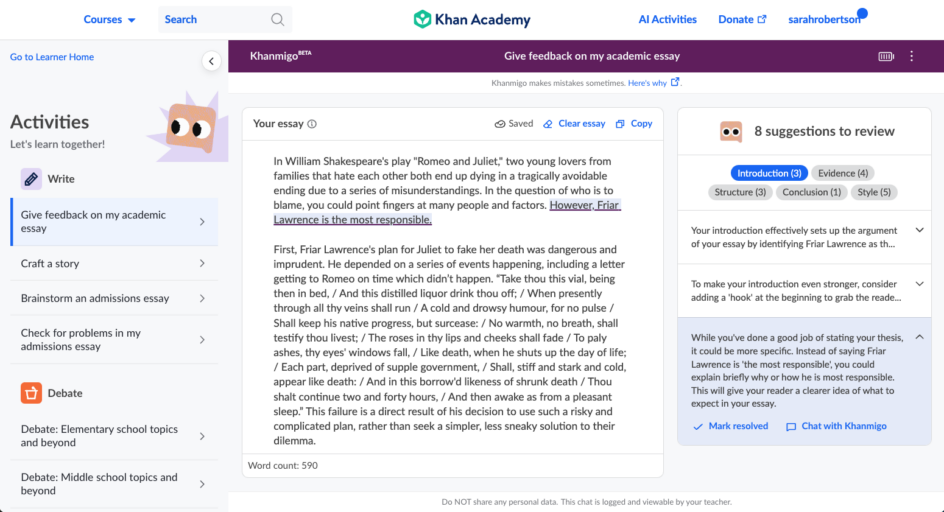

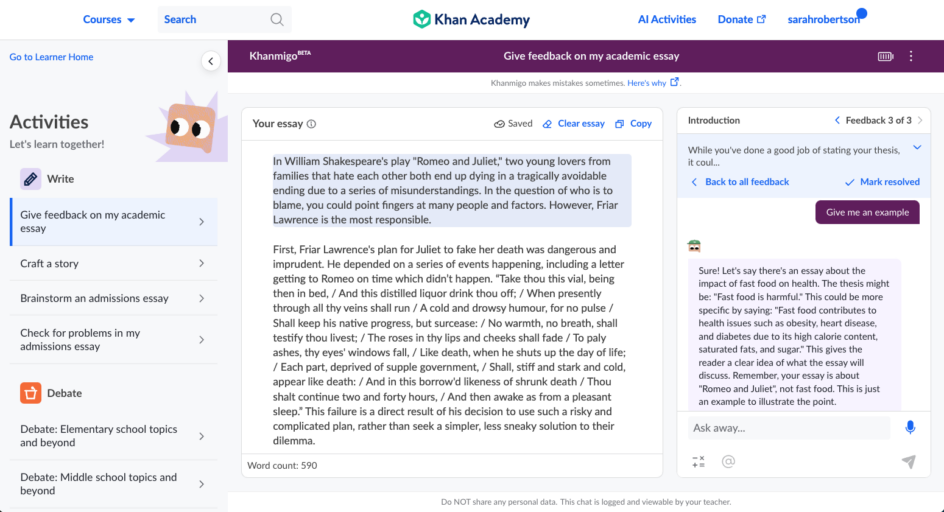

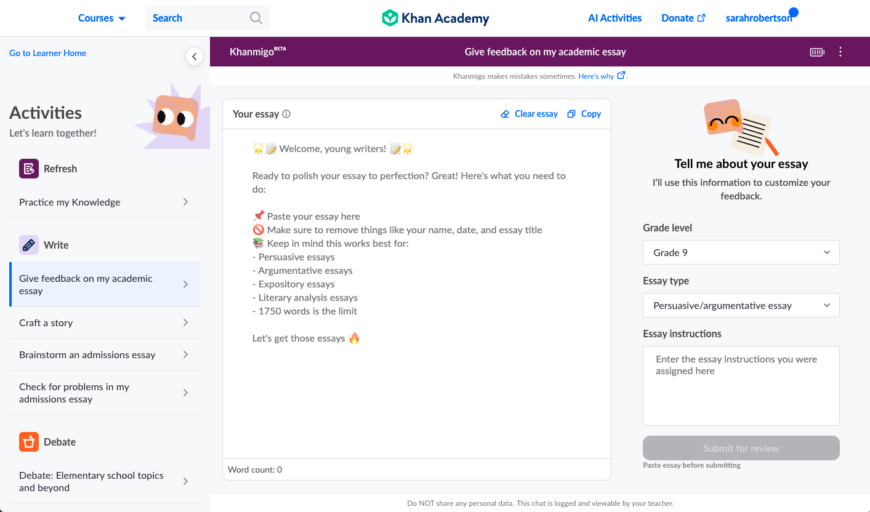

Introducing Khanmigo’s New Academic Essay Feedback Tool

posted on November 29, 2023

By Sarah Robertson , senior product manager at Khan Academy

Khan Academy has always been about leveraging technology to deliver world-class educational experiences to students everywhere. We think the newest AI-powered feature in our Khanmigo pilot—our Academic Essay Feedback tool—is a groundbreaking step toward revolutionizing how students improve their writing skills.

The reality of writing instruction

Here’s a word problem for you: A ninth-grade English teacher assigns a two-page essay to 100 students. If she limits herself to spending 10 minutes per essay providing personalized, detailed feedback on each draft, how many hours will it take her to finish reviewing all 100 essays?

The answer is that it would take her nearly 17 hours —and that’s just for the first draft!

Research tells us that the most effective methods of improving student writing skills require feedback to be focused, actionable, aligned to clear objectives, and delivered often and in a timely manner .

The unfortunate reality is that teachers are unable to provide this level of feedback to students as often as students need it—and they need it now more than ever. Only 25% of eighth and twelfth graders are proficient in writing, according to the most recent NAEP scores .

An AI writing tutor for every student

Developed by experts in English Language Arts (ELA) and writing instruction, the pilot Khanmigo Academic Essay Feedback tool uses AI to offer students specific, immediate, and actionable feedback on their argumentative, expository, or literary analysis essays.

Unlike other AI-powered writing tools, the Academic Essay Feedback tool isn’t limited to giving feedback on sentence- or language-level issues alone, like grammar or spelling. Instead, it provides feedback on areas like essay structure and organization, how well students support their arguments, introduction and conclusion, and style and tone.

The tool also doesn’t just stop at providing feedback, it also guides students through the revision process. Students can view highlighted feedback, ask clarifying questions, see exemplar writing, make revisions, and ask for further review—without the AI doing any actual writing for them.

Unique features of Khanmigo pilot Academic Essay Feedback tool

- Immediate, personalized feedback: within seconds, students get detailed, actionable, grade-level-appropriate feedback (both praise and constructive) that is personalized to their specific writing assignment and tied directly to interactive highlights in their essay.

- Comprehensive approach: feedback covers a wide range of writing skills, from crafting an engaging yet focused introduction and thesis, to overall essay structure and organization, to style and tone, to alignment and use of evidence.

- Interactive revision process: students can interact with Khanmigo to ask questions about specific pieces of feedback, get examples of model writing, make immediate revisions based on the feedback, and see if their revisions addressed the suggestion.

- Support for various essay types: the tool is versatile and assists with multi-paragraph persuasive, argumentative, explanatory, and literary analysis essay assignments for grades 8-12 (and more, coming soon).

- Focus on instruction and growth: like all Khanmigo features, the Academic Essay Feedback tool will not do the work for the student. Teachers and parents can rest assured that Khanmigo is there to improve the students’ independent writing skills, not provide one-click suggested revisions.

How parents can use Khanmigo’s Academic Essay Feedback tool

Any student with Khanmigo access can find the feedback tool under the “Write” category on their AI Activities menu.

For academic essays, students should simply paste their first draft into the essay field, select their grade level and essay type, and provide the essay instructions from the teacher.

Students then click “Submit” and feedback begins generating. Once Khanmigo is done generating feedback, students can work their way through the suggestions for each category, chat with Khanmigo for help, make revisions, and resolve feedback. They can then submit their second draft for another round of feedback, or copy the final draft to submit to their teacher.

Bringing Khanmigo to your classroom, school, or district

Teachers in Khan Academy Districts partnerships can begin using the Khanmigo Academic Essay Feedback tool with their students right away. Simply direct students to the feedback tool under the “Write” category on their AI Activities menu.

Like all other Khanmigo activities, students’ interactions are monitored and moderated for safety. Teachers or parents can view the student’s initial draft, AI-generated feedback, chat history, and final draft in the student’s chat history. If anything is flagged for moderation, teachers or parents will receive an email notification.

Looking ahead

With the Academic Essay Feedback tool in our Khanmigo pilot, teachers and parents can empower students to take charge of their writing.The tool helps facilitate a deeper understanding of effective writing techniques and encourages self-improvement. For teachers, we think this tool is a valuable ally, enabling them to provide more frequent, timely, detailed, and actionable feedback for students on multiple drafts.

In the coming months, we’ll be launching exciting improvements to the tool and even more writing resources for learners, parents, teachers, and administrators:

- The ability for teachers to create an essay-revision assignment for their students on Khan Academy

- More varied feedback areas and flexibility in what feedback is given

- Support for students in essay outlining and drafting

- Insights for teachers and parents into their students’ full writing process

Stay tuned!

Sarah Robertson is a senior product manager at Khan Academy. She has a M.Ed. in Curriculum and Instruction and over a decade of experience teaching English, developing curriculum, and creating software products that have helped tens of millions of students improve their reading and writing skills.

Get Khanmigo

The best way to learn and teach with AI is here. Ace the school year with our AI-powered guide, Khanmigo.

For learners For teachers For parents

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Give Feedback Effectively and Respectfully

5 rules that will help you crush your next round of performance reviews