Why Students Drop Out

Even though school completion rates have continually grown during much of past 100 years, dropping out of school persists as a problem that interferes with educational system efficiency and the most straightforward and satisfying route to individual educational goals for young people. Doll, Eslami, and Walters (2013) present data from seven nationally representative studies (spanning more than 50 years) regarding reasons students drop out of high school. Some excerpts are presented below in tables; however, for a complete discussion, please see the original article: “ Understanding Why Students Drop Out of High School, According to Their Own Reports ”

The selected tables are presented in opposite order than they appear in the article so as to present the most recent data first. Note also that survey questions varied from study to study (database to database) so caution should be taken in making comparisons across years and studies.

Included in the tables presented is an analysis of whether the reasons presented are considered “push,” “pull,” or “falling out” factors. The following briefly presents an explanation from Doll et al. (2013).

Jordan et al. (1994) explained pressures on students of push and pull dropout factors. A student is pushed out when adverse situations within the school environment lead to consequences, ultimately resulting in dropout. . . . [S]tudents can be pulled out when factors inside the student divert them from completing school. . . . Watt and Roessingh (1994) added a third factor called falling out of school, which occurs when a student does not show significant academic progress in schoolwork and becomes apathetic or even disillusioned with school completion. It is not necessarily an active decision, but rather a “side-effect of insufficient personal and educational support” (p. 293).

The National Dropout Prevention Center (NDPC) exists to support those who work to improve student success and graduation rates. NDPC offers a wide range of resources and services to schools, districts, regional agencies, and states. Contact NDPC by (email: [email protected] or phone: (864-642-6372.).

Featured Resources

- Our Mission

How to End the Dropout Crisis: 10 Strategies for Student Retention

Proven tactics for keeping kids engaged and in school, all the way through high school graduation.

Are you sitting down? Each year, more than a million kids will leave school without earning a high school diploma -- that's approximately 7,000 students every day of the academic year. Without that diploma, they'll be more likely to head down a path that leads to lower-paying jobs, poorer health, and the possible continuation of a cycle of poverty that creates immense challenges for families, neighborhoods, and communities.

For some students, dropping out is the culmination of years of academic hurdles, missteps, and wrong turns. For others, the decision to drop out is a response to conflicting life pressures -- the need to help support their family financially or the demands of caring for siblings or their own child. Dropping out is sometimes about students being bored and seeing no connection between academic life and "real" life. It's about young people feeling disconnected from their peers and from teachers and other adults at school. And it's about schools and communities having too few resources to meet the complex emotional and academic needs of their most vulnerable youth.

Although the reasons for dropping out vary, the consequences of the decision are remarkably similar. Over a lifetime, dropouts typically earn less, suffer from poorer health as adults, and are more likely to wind up in jail than their diploma-earning peers. An August 2007 report by the California Dropout Research Project (PDF) detailed the economic and social impacts of failing to finish high school in the Golden State. The numbers cited in the report are sobering: High school graduates earn an average of nearly $290,000 more than dropouts over their lifetime, and they are 68 percent less apt to rely on public assistance. The link between dropout rates and crime is also well documented, and the report's data indicates that high school graduation reduces violent crime by 20 percent. And nationally, the economic impact is clear: A 2011 analysis by the Alliance for Excellent Education estimates that by halving the 2010 national dropout rate, for example (an estimated 1.3 million students that year), "new" graduates would likely earn a collective $7.6 billion more in an average year than they would without a high school diploma.

Mounting research on the causes and consequences of dropping out, coupled with more accurate reporting on the extent of the crisis, has led to increased public focus on what's been called the silent epidemic. And with that focus comes the possibility of more action at the local, state, and national levels to implement a mix of reforms that will support all students through high school graduation. Such reforms include early identification of and support for struggling students, more relevant and engaging courses, and structural and scheduling changes to the typical school day.

Decades of research and pockets of success point to measures that work. Here are ten strategies that can help reduce the dropout rate in your school or community. We begin with steps to connect students and parents to school and then address structural, programmatic, and funding changes:

1. Engage and Partner with Parents

It's an all-too-familiar story: Parent involvement declines as students get older and become more independent. But although the role of parents changes in secondary school, their ongoing engagement -- from regular communication with school staff to familiarity with their child's schedule, courses, and progress toward graduation -- remains central to students' success. Findings in a March 2006 report, " The Silent Epidemic ," illustrate the importance of engaged parents throughout secondary school. Sixty-eight percent of the high school dropouts who participated in the study said their parents became involved in their education only after realizing their student was contemplating dropping out of school.

In Sacramento, California, high school staff members make appointments with parents for voluntary home visits, to keep parents engaged with their children's progress. This strategy -- which has so far been replicated nationally in eleven states, plus the District of Columbia -- includes placing as many visits as possible during summer and fall to parents of teens entering high school -- a critical transition point for many students -- to begin building a net of support and to connect parents to the new school. Staffers also conduct summer, fall, and spring home visits between and during the sophomore and junior years to students who are at risk of not graduating because of deficiencies in course credits, the possibility of failing the state high school exit exam (a condition of graduation), or poor grades. Visits in the summer after junior year and fall of senior year are to ensure that students are on track for either career or college. Early evaluations of the program by Paul Tuss of Sacramento County Office of Education's Center for Student Assessment and Program Accountability found that students who received a home visit were considerably more likely to be successful in their exit exam intervention and academic-support classes and pass the English portion of the exit exam. A follow-up evaluation of the initial cohort of students at Luther Burbank High School showed that the students both passed the exit exam and graduated high school at significantly higher rates. (Visit the website of the Parent/Teacher Home Visit Project .)

2. Cultivate Relationships

A concerned teacher or trusted adult can make the difference between a student staying in school or dropping out. That's why secondary schools around the country are implementing advisories -- small groups of students that come together with a faculty member to create an in-school family of sorts. These advisories, which meet during the school day, provide a structured way of enabling those supporting relationships to grow and thrive. The most effective advisories meet regularly, stay together for several years, and involve staff development that helps teachers support the academic, social, and emotional needs of their students. In Texas, the Austin Independent School District began incorporating advisories into all of its high schools in 2007/2008 to ensure that all students had at least one adult in their school life who knew them well, to build community by creating stronger bonds across social groups, to teach important life skills, and to establish a forum for academic advisement and college and career coaching. (Download a PDF summary of the results of a 2010 survey about Austin's advisory program .)

3. Pay Attention to Warning Signs

Project U-Turn , a collaboration among foundations, parents, young people, and youth-serving organizations such as the school district and city agencies in Philadelphia, grew out of research that analyzed a variety of data sources in order to develop a clear picture of the nature of Philadelphia's dropout problem, get a deeper understanding of which students were most likely to drop out, and identify the early-warning signs that should alert teachers, school staff, and parents to the need for interventions. After looking at data spanning some five years, researchers were able to see predictors of students who were most at risk of not graduating .

Key indicators among eighth graders were a failing final grade in English or math and being absent for more than 20 percent of school days. Among ninth graders, poor attendance (defined as attending classes less than 70% of the time), earning fewer than two credits during 9th grade, and/or not being promoted to 10th grade on time were all factors that put students at significantly higher risk of not graduating, and were key predictors of dropping out. Armed with this information, staff members at the school district, city, and partner organizations have been developing strategies and practices that give both dropouts and at-risk students a web of increased support and services, including providing dropout-prevention specialists in several high schools, establishing accelerated-learning programs for older students who are behind on credits, and implementing reading programs for older students whose skills are well below grade level.

4. Make Learning Relevant

Boredom and disengagement are two key reasons students stop attending class and wind up dropping out of school. In "The Silent Epidemic," 47 percent of dropouts said a major reason for leaving school was that their classes were not interesting. Instruction that takes students into the broader community provides opportunities for all students -- especially experiential learners -- to connect to academics in a deeper, more powerful way.

For example, at Big Picture Learning schools throughout the country, internships in local businesses and nonprofit organizations are integrated into the regular school week. Students work with teacher advisers to find out more about what interests them and to research and locate internships; then on-the-job mentors work with students and school faculty to design programs that build connections between work life and academics. Nationwide, Big Picture schools have an on-time graduation rate of 90 percent. Watch an Edutopia video about Big Picture Schools .

5. Raise the Academic Bar

Increased rigor doesn't have to mean increased dropout rates. Higher expectations and more challenging curriculum, coupled with the support students need to be successful, have proven to be an effective strategy not only for increasing graduation rates, but also for preparing students to graduate from high school with options. In San Jose, California, the San Jose Unified School District implemented a college-preparatory curriculum for all students in 1998. Contrary to the concerns of early skeptics, the more rigorous workload didn't cause graduation rates to plummet. Recent data shows that the SJUSD has a four-year dropout rate of just 11.4 percent, compared with a statewide average of 18.2 percent.

6. Think Small

For too many students, large comprehensive high schools are a place to get lost rather than to thrive. That's why districts throughout the country are working to personalize learning by creating small schools or reorganizing large schools into small learning communities, as part of their strategy for reducing the dropout rate. A 2010 MDRC report funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation looked at the 123 "small schools of choice," or SSCs, that have opened in New York City since 2002. The report showed higher graduation rates at the new schools compared with their much larger predecessors. By the end of their first year in high school, 58.5 percent of students enrolled in SSCs were on track to graduate, compared with 48.5 percent of their peers in other schools, and by the fourth year, graduation rates increased by 6.8 percentage points.

7. Rethink Schedules

For some students, the demands of a job or family responsibilities make it impossible to attend school during the traditional bell schedule. Forward-thinking districts recognize the need to come up with alternatives. Liberty High School , a Houston public charter school serving recent immigrants, offers weekend and evening classes, providing students with flexible scheduling that enables them to work or handle other responsibilities while still attending school. Similarly, in Las Vegas, students at Cowan Sunset Southeast High School's campus can attend classes in the late afternoon and early evening to accommodate work schedules, and they may be eligible for child care, which is offered on a limited basis to help young parents continue their education. Watch an Edutopia video about Cowan Sunset High School .

8. Develop a Community Plan

In its May 2007 report " What Your Community Can Do to End Its Drop-Out Crisis ," the Center for Social Organization of Schools at Johns Hopkins University advocates development of a community-based strategy to combat the problem. Author Robert Balfanz describes three key elements of a community-driven plan: First is knowledge -- understanding the scope of the problem as well as current programs, practices, and resources targeted at addressing it. Second is strategy -- development of what Balfanz describes as a "dropout prevention, intervention, and recovery plan" that focuses community resources. Last is ongoing assessment -- regular evaluation and improvement of practices to ensure that community initiatives are having the desired effect.

9. Invest in Preschool

In their August 2007 report " The Return on Investment for Improving California's High School Graduation Rate " (PDF), Clive R. Belfield and Henry M. Levin review both evidential and promising research as well as economically beneficial interventions for addressing the dropout crisis. Preschool, they argue, is an early investment in youth that yields significant economic results later on. In their review of the research on preschool models in California and elsewhere, the authors found that one preschool program increased high school graduation rates by 11 percent, and another by 19 percent. A 2011 article published in Science by researchers who followed participants in Chicago's early childhood education program Child-Parent Center for 25 years found, among other results, that by age 28, the group that began preschool at age three or four had higher educational levels and incomes, and lower substance abuse problems.

10. Adopt a Student-Centered Funding Model

Research shows that it costs more to educate some students, including students living in poverty, English-language learners, and students with disabilities. Recognizing this need, some districts have adopted a student-centered funding model, which adjusts the funding amount based on the demographics of individual students and schools, and more closely aligns funding to their unique needs. Flexible funding enables schools with more challenging populations to gain access to more resources so they can take needed steps such as reducing class size, hiring more experienced and effective teachers, and implementing other programs and services to support students with greater needs.

Although switching to this funding model does require an infusion of new dollars -- to support the added costs associated with educating certain groups of students without reducing funds to schools with smaller at-risk populations -- many districts have already explored or are using this option, including districts in Denver, New York City, Oakland and San Francisco, Boston, Chicago, Houston, Seattle, Baltimore, Hartford, Cincinnati, and the state of Hawaii, which has only one school district.

Roberta Furger is a contributing writer for Edutopia .

Back to Top

Retention Research: Studies About Keeping Kids in School

The following reports provide valuable insight into the causes of and solutions for the dropout crisis plaguing many of our schools and communities:

"Unfulfilled Promise: The Dimensions and Characteristics of Philadelphia's Dropout Crisis, 2000-2005" (PDF)

By analyzing a unique collection of both city and school district data sets over multiple years, researchers Ruth Curran Neild and Robert Balfanz were able to identify key characteristics of students most at risk for dropping out of school. The report describes the project and discusses the factors, such as grades and attendance, that are identified as predictive of high-risk students.

"The Silent Epidemic: Perspectives of High School Dropouts" (PDF)

This 2006 report, sponsored by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation , is based on interviews with young men and women, ages 16 - 25, who dropped out of high school. The findings debunk some of the commonly held myths about why students decide to drop out of school. (For example, a majority of the young people who were interviewed had at least a C average when they dropped out, and 47 percent reported that they dropped out because school was not interesting.) Embedded in these insights are useful strategies for addressing the crisis.

"Transforming the High School Experience: How New York City's New Small Schools are Boosting Student Achievement and Graduation Rates"

This 2010 report, published by the nonprofit education and social policy research organization MDRC , takes a close look at New York City’s 123 "small schools of choice," or SSCs. These schools are open to students at all levels of academic achievement, located in disadvantaged communities, and emphasize strong relationships between students and faculty. So far, they’ve also been successful at raising graduation rates.

"What Your Community Can Do to End Its Drop-Out Crisis" (PDF)

Drawing on drop-out crisis research at the national level, as well as author Robert Balfanz's decade-long experience working with middle and high schools that serve low-income students, this report provides a unique guide to tackling the issue locally. It begins with strategies for developing a deep understanding of local needs and then guides readers step by step through the creation of a comprehensive plan to assist students inside and outside of school.

"Building a Grad Nation: Progress and Challenge in Ending the High School Dropout Epidemic"

This 2011 annual update on a November 2010 report by Civic Enterprises , The Everyone Graduates Center at Johns Hopkins University, and America's Promise Alliance takes a look at the big picture. It is still grim, but getting less so: For instance, the number of high schools that qualify as "dropout factories" (schools that graduate 60 percent or less of their students) has declined from 2,007 in 2002 to 1,634 in 2009. The report compares current data with national goals and explores best practices through several in-depth case studies of struggling school districts.

"On Track for Success: The Use of Early Warning Indicator and Intervention Systems to Build a Grad Nation" (PDF)

Another report from Civic Enterprises and The Everyone Graduates Center at Johns Hopkins University, published in November 2011, asks how effective early intervention can be to prevent dropouts and build graduation rates. Early Warning Indicator and Intervention Systems (EWS) represent a collaborative approach by educators, administrators, parents, and communities to identify and support students at risk of not graduating. The report investigates the most successful EWS through case studies in eastern Missouri, Chicago, and Philadelphia, among others.

Last updated: 01/03/2012 by Sara Bernard

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Dropping out of school: explaining how concerns for the family’s social-image and self-image predict anger.

- 1 Faculty of Health and Welfare, Østfold University College, Fredrikstad, Norway

- 2 PErSEUs, Sciences Humaines et Sociales, Université de Lorraine (Metz), Nancy, France

As dropping out of school is considered a violation of moral norms, the family associated with the drop out can react with anger directed toward the pupil or with anger directed at others that might know of the drop out. In our vignette study ( N = 129), we found that anger at others and anger at the pupil were significantly higher if our community participants imagined a drop out from a vocational education rather than a general education. As expected, anger directed at others was fully explained by a concern for the family’s social-image (i.e., a concern for condemnation by others), while anger directed at the former pupil was fully explained by a concern for the family’s self-image (i.e., a concern for their moral self-image). Thoughts for how to better understand family reactions in relation to drop out are discussed.

Introduction

«Hvorfor er det sånn at jeg må være flau, hvorfor må de som har valgt et yrkesfaglig program bli stemplet som dumme, teorisvake og skoleleie?» [“Why do I have to be embarrassed, how come those who choose vocational education are labeled as stupid, theoretically weak and sick of school?”] - Girl, 17 years, vocational student (interviewed in Aftenposten, 2015 , translated by us).

Even though most educational programs are organized in order to support integration into the social and professional world ( Beblavy et al., 2011 ), some pupils decide to drop out of these educational programs. As a drop out has the potential to be perceived by others as a violation of the expected egalitarian integration path ( Van Hoorn and Maseland, 2013 ), their norm violating decision is often met with stigmatizing condemnation by the larger community ( Weiner et al., 1988 ; Dorn, 1993 ; Hebl et al., 2007 ; Gausel, 2014 ). As a response to condemnation, people sometimes respond with blame ( Gausel, 2014 ) and anger ( Gausel et al., 2018 ). However, little if nothing is known about the families’ reactions and especially whether families respond with anger if their son or daughter drops out of school.

In order to investigate whether families would respond with anger to condemnation for dropping out of school, we asked community participants to imagine how a family would react if their son or daughter dropped out of an educational program. We expected that the more our participants expressed that the family would be concerned about the moral self-image of the family, the more the family would direct anger at their son or daughter (i.e., the former pupil). In contrast, the more our participants expressed that the family would be concerned about the social-image of the family, the more the family would direct anger toward others that might learn of the drop out.

Vocational Education: Dropping Out

In most western countries, the high-school (or upper secondary school) educational system consists of general education and vocational education. Even though most pupils choose vocational education in order to acquire a professional job qualification, the real-world citation by the 17-year old girl in the introduction demonstrates that vocational education has become to be viewed as a second-chance education ( Karmel and Woods, 2008 ) for pupils falsely believed to be less intelligent and thus having “a lower level of general aptitude” ( Arum and Shavit, 1995 , p.188). Due to this stigmatized belief, vocational pupils are therefore seen to be suited for professional work, instead of the more “university-oriented” general education ( Grootaers et al., 1999 ; Gausel, 2014 ). As a consequence of this stigma, many pupils within the vocational education report that they feel that others look down at them for following a vocational program ( Spruyt et al., 2015 ).

As the educational system represents the egalitarian view that everyone deserves a fair chance of bettering their position regardless of their background ( Beblavy et al., 2011 ), dropping out of the educational system represents “a serious problem, not only for the individual, the school system, and the community, but also for society.” ( Christle et al., 2007 , p. 325). Even though dropping out – in general – is understood as a problematic norm violation ( Dorn, 1993 ), dropping out from a vocational education seems to be more problematic for the pupil and its family for at least two reasons: firstly, dropping out violates the social ascension belief that members of low status groups should climb the social ladder via the educational system ( Festinger, 1954 ; Hauser et al., 2000 ). Secondly, as western people typically believe that one is responsible for one’s own fate ( Bénabou and Tirole, 2004 ), a discontinuation of schooling violates the meritocracy belief that individuals should demonstrate perseverance ( Lerner, 1980 ). Dropping out of a vocational education can therefore be perceived by the larger society as the pupil is entering a competitive labor market without formal means to partake ( Christle et al., 2007 ). Thus, the pupil is risking unemployment and dependence on welfare benefits ( Christle et al., 2007 ; King et al., 2010 ). As people generally react harshly toward norm violators ( Crocker et al., 1998 ; Major and O’Brien, 2005 ; Täuber et al., 2018 ), dropping out of vocational education has the potential to cause considerable psychological distress, not only for the pupil ( Dorn, 1993 ), but also for the family associated with the drop out ( Gausel, 2014 ) as families are commonly seen as a group ( Scabini and Manzi, 2011 ).

Anger: The Role of the Self-Image and the Social-Image

According to Gausel and Leach (2011) , a norm violation of this kind can be appraised in at least two main ways: firstly, as an indication that there is something morally defective with the family, since they allowed a violation of a societal norm (i.e., a threat to the moral self-image of the family) by failing to prevent the drop out, and thus, failing take advantage of the social ascension possibility and failing to demonstrate perseverance. Failures that are appraised as representing a threat to the self-image are often associated with anger directed at the self ( Miller and Tangney, 1994 ; Gausel and Leach, 2011 ) or one’s in-group ( Gausel and Leach, 2011 ). As it is well known that families represent a group and its members are group members (for discussions, see Scabini and Manzi, 2011 ), it is interesting to observe that on a family-related level, Gausel et al. (2016) found that participants appraising themselves as suffering from a morally defective self-image directed anger toward themselves as a consequence for their abusive behavior toward a family member. And Berndsen and McGarty (2012) found that majority group members reminded about moral failures committed by their group expressed anger at their own group in response to these failures. Similar to this, Gausel et al. (2012) found that the more their participants appraised their in-group moral failures as a threat to their in-group self-image, the more anger they directed toward their own group. Hence, in response to the current study, we expected that a concern for the self-image of the family as caused by the drop out would be predictive of self-directed anger.

Secondly, as there is a real risk that failures can draw condemning attention from others ( Gausel and Leach, 2011 ), a drop out may pose a serious threat to the family’s social-image as respectable in the eyes of others. If such a threat to the social-image is appraised, people often react with anger directed at the others that can possibly come to condemn them for their failure ( Gausel, 2013 ). In empirical support of this, a recent study on family therapy and reciprocal partner-violence, Zahl-Olsen et al. (2019) found that outburst of anger and violence toward the other was associated with appraised condemnation manifested through rejecting behavior from the other as well as criticism for failure. Gausel et al. (2018) found that the more victims of immorality feared that they would be condemned for their own perpetrating failures in a reciprocal conflict, the more they reacted with hostile anger toward others. In response to the current study, we expected that a concern for the family’s social-image would be predictive of other-directed anger.

In sum, there is ground to assume that being associated with dropping out of school can be appraised by a family as a threat to their self-image as dropping out symbolize the failure to demonstrate perseverance, as well as the failure to conform with the social ascension belief. This might very well predict anger directed at the responsible one, i.e., the pupil. That said, there is also ground to believe that the eyes of others are now critically resting on the family. Thus, being associated with dropping out of school represents a vivid threat to the social-image of the family, especially if they fear that these others get to find out about the failure. If so, the family might very well direct anger against these others.

The Current Study

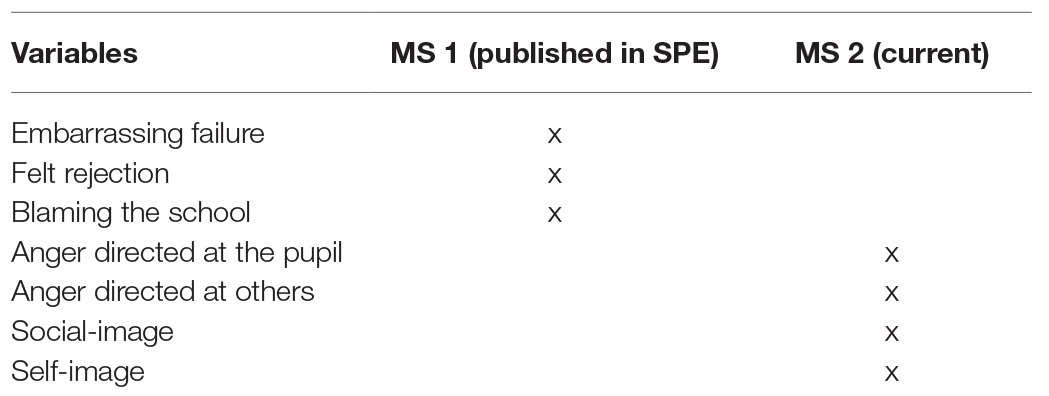

In order to test the above assumptions, we returned to a large-scale study where parts have previously been reported in a manuscript by Gausel (2014) . However, none of the measures, and analyses and none of the correlations reported here in this manuscript have been examined or reported elsewhere. For the sake of clarity, we illustrate how the measures are used across the two manuscripts in Table 1 .

Table 1 . Illustration of the measures used.

In line with previous research and theorizing, we expected that our community participants would regard a drop out as a wrong decision, and that the drop out is expected to hurt the family’s self and social-image. Importantly, based on the folk-view that a vocational education can be seen as a “second-chance” education, we anticipated the following results: firstly, we expected that a drop out from a vocational education would be seen to be making the family more upset, i.e., make them angrier at the former pupil, and angrier at others, than if the drop out had happened in a general education program. Secondly, anger directed at the former pupil would be explained by a concern for the family’s self-image. In contrast, anger directed at others would be explained by a concern for the family’s social-image.

Materials and Methods

Participants.

Hundred and twenty nine community participants (62.2% women, 37.8% men; mean age : 36.1, age range : 17–74 years) agreed to partake in an anonymous, hard copy standardized questionnaire study focusing on social perceptions. They were approached individually in parks, cafes, and libraries in a medium-sized city in Norway. Participants were randomized into two conditions: “ Vocational education drop out ” ( N = 64) and “ General education drop out ” ( N = 65).

Procedure and Measures

On the first page of the questionnaire participants read the information of the study as described above and agreed to partake in the study. On the same page, we asked the participant to fill in demographics of gender and age. On the next page, “ vocational education drop out ” participants were asked to imagine the following: “ A student at the (the name of a locally known vocational education high-school) decided to drop out from the education in the middle of the semester .” Participants allocated to the “ General education drop out ” condition were asked to imagine the same thing, only now naming a locally known general education high-school. On the third page, participants were presented with standardized items measuring how this drop out could be appraised by the family of the student, and how they would respond to the drop out. When finished, participants were debriefed and thanked. All items were adopted from Gausel et al. (2012 , 2016 , 2018 ) and ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much).

Anger directed at the pupil ( α = 0.96) was measured with: “The family would be angry at the pupil,” “The family would be cross at the pupil,” and “The family would be irritated at the pupil.” Anger directed against those who know ( α = 0.93) was measured using three items: “The family would be angry at those who know what the pupil did,” “The family would be cross at those who know what the pupil did,” and “The family would be irritated at those who know what the pupil did.”

Appraisals of Social-Image and Self-Image

The appraisal of being condemned by others, and thus causing damage to the family’s social image ( α = 0.87) was measured using three statements: “The family will think they can be isolated from others because of this,” “The family will think that their reputation can damaged because of what the pupil did,” and “The family will think that others might not have the same respect for them because of this.” The appraisal of damage to the family’s moral self-image ( α = 0.89) was measured with three statements: “The family will think that what the pupil did represented a moral failure in the family,” “The family will think they are defective in one way or another,” and “The family will think this represents a “black mark” in their shared memory.”

Appraising the Drop Out as Wrong

We measured whether participants appraised the dropout as wrong ( α = 0.85) using four items: “What the pupil did was wrong,” “What the pupil did was bad,” “What the pupil did was doubtful,” and “What the pupil did was not good.”

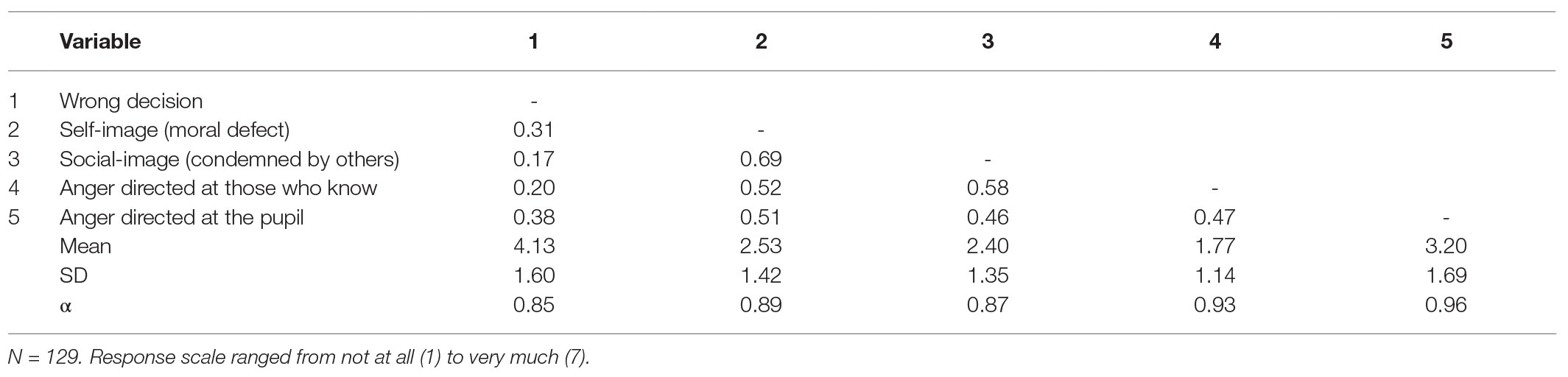

Participants View of Dropping Out of School as Wrong or Not

A one way ANOVA using IBM SPSS 22 (see Table 2 for scale inter-correlations and descriptive statistics) made it clear that participants considered it wrong to drop out from college irrelevant of education, F (1,128) = 1.16, p = 0.28, partial η 2 = 0.01. Interestingly, they saw dropping out from the vocational education as slightly more wrong than from a general education ( M = 4.28, SD = 1.67 and M = 3.97, SD = 1.54, respectively).

Table 2 . Scale inter-correlations and descriptive statistics.

A Concern for Self-Image and Social-Image

A Multivariate ANOVA demonstrated no significant overall effect on the appraisal of self-image and social-image, F (2,126) = 0.587, p = 0.56, partial η 2 = 0.01. A univariate analysis on each of the two variables showed that participants in the “ Vocational education drop out ” and the “ General education drop out ,” saw the drop out of school as equally damaging to the family’s self-image, F (1,127) = 1.16, p = 0.284, partial η 2 = 0.01 ( M = 2.67, SD = 1.53 and M = 2.40, SD = 1.31, respectively), and the family’s social-image, F (1,127) = 0.73, p = 0.395, partial η 2 = 0.01, ( M = 2.51, SD = 1.39 and M = 2.30, SD = 1.30, respectively) even though the means were a bit higher for participants in the vocational education drop out condition.

Participants View on Anger Directed at the Pupil and Anger Directed at Others

A Multivariate ANOVA demonstrated an overall effect on our main dependent variables of anger, F (2,123) = 3.10, p = 0.049, partial η 2 = 0.05. As expected, there was a significant univariate effect on anger directed at others who would know about the drop out, F (1,124) = 4.51, p = 0.036, partial η 2 = 0.04. The pairwise comparison showed that participants in the “ Vocational education drop out ” condition considered it as more likely that the family would be angry at others who knew about the drop out ( M = 1.97, SD = 1.27), than did participants in the “ General education drop out ” condition ( M = 1.55, SD = 0.95). As expected, there was a significant univariate effect on anger directed at the pupil, F (1,124) = 4.53, p = 0.035, partial η 2 = 0.04. The pairwise comparison demonstrated that participants in the “ Vocational education drop out ” condition considered it likely that the family would be more angry with the pupil ( M = 3.51, SD = 1.74), than did participants in the “ General education drop out ” condition ( M = 2.88, SD = 1.58).

Structural Equation Modeling: Explaining Direction of Anger

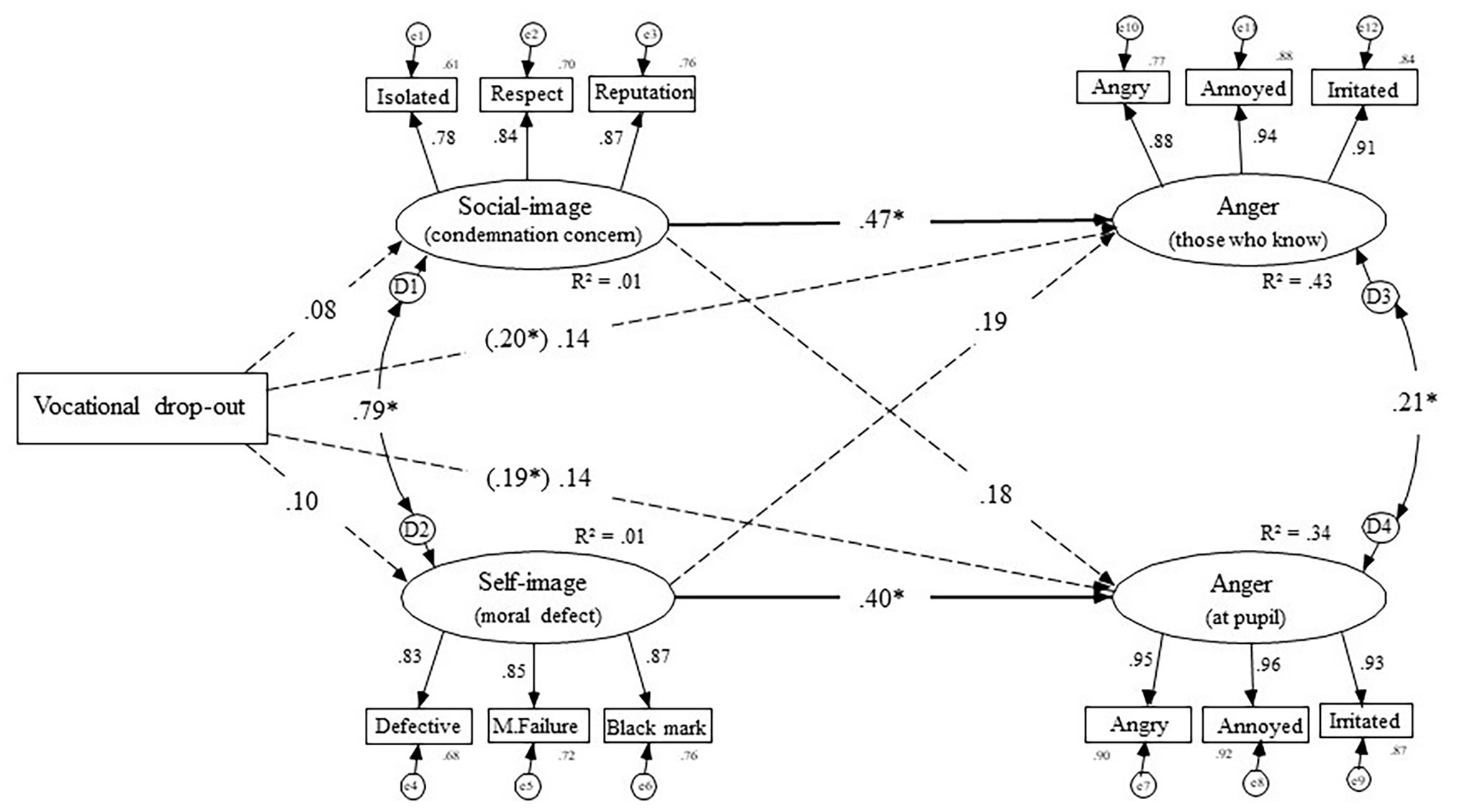

In order to explain anger directed at the pupil and anger directed at others, we specified a latent model using Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS 22 software. Mirroring the two conditions, we used effect coding (vocational education drop out = +1 and general education drop out = −1) in order to trace the main effects of the experimental conditions (represented with a manifest variable) on our two main dependent variables; anger directed at the self and anger directed at others. Since we expected a concern for the family’s self-image and concerns for the family’s social-image to explain the relationship with anger, we allowed them to mediate the relationship between the experimental conditions and the two anger variables (see Figure 1 ). This model fit the data very well, χ 2 (56) = 80.65, p = 0.017, χ 2 / df = 1.44, IFI = 0.982, CFI = 0.982, RMSEA = 0.059.

Figure 1 . Structural path model of the manipulation on concerns for self-image and social-image and their link to the two angers. Solid lines illustrate significant relationships ( * p < 0.05).

As seen in the upper half of Figure 1 , the original link between the experimental conditions and anger directed at the pupil ( β = 0.19, p = 0.031) dropped to non-significant ( β = 0.14, p = 0.077), indicating that the relationship was mediated by concern for the family’s self-image. In contrast, as we argued that the motivation behind anger directed at others was a concern for the family’s social-image, the lower half of Figure 1 illustrate that the original link between the experimental conditions and anger directed at others ( β = 0.20, p = 0.032) dropped to non-significant ( β = 0.14, p = 0.062). Hence, anger at others was mediated by concern for the family’s self-image.

Even though there can be good reasons for dropping out of an educational program, a drop out generally violates societal norms (e.g., Dorn, 1993 ; Gausel, 2014 ) such as the meritocracy norm of perseverance ( Lerner, 1980 ) and taking advantage of the possibility to climb the social ladder via the educational system ( Festinger, 1954 ; Hauser et al., 2000 ; Van Hoorn and Maseland, 2013 ). Probably therefore, our community participants considered dropping out to be moderately wrong regardless of the educational path, and by such, they lend support to Christle et al. (2007) view that a drop out represents a serious challenge, not only for the society but also for the school system, the community and the individual. Similarly, the decision to drop out was also viewed by the participants as a cause for concern in regard of both the family’s self-image and its social-image. This finding support Gausel and Leach (2011) argumentation that a failure to adhere to norms will likely threaten the self-image and the social-image of the individual (or group) associated with the failure.

In line with our hypotheses, we found that participants expected the family to be angrier at the former pupil for dropping out of vocational education than if dropping out of a general education. This is understandable, because expressing anger at the pupil might communicate that the family is disappointed over the decision to drop out of vocational education in an increasingly competitive labor market ( Grootaers et al., 1999 ; Van Hoorn and Maseland, 2013 ). Moreover, since anger directed at the former pupil was explained by concern for moral self-image, the findings support the arguments of Gausel and Leach (2011) that a threat to self-image will likely motivate self-directed anger.

Also in line with our hypotheses, we found that participants in the vocational education condition expected the family to be angrier at others for the drop out than did those in the general education condition. As expected, the motivation to direct anger at others was explained by the concern for loss of respect in the eyes of others (i.e., the threat to the family’s social-image). This finding is in line with Gausel and Leach (2011) argument that the threat to the social-image is a motivator of anti-social responses and hostility. Moreover, this finding bears resemblance to Zahl-Olsen et al. (2019) findings where anger and violence in families seems to be fueled by rejecting criticism for failure. It also lends support to Gausel et al. (2018) findings that victims of failures reacted with hostile anger toward others due to the fears that their social-image would be damaged. By such, it appears that the community participants expected reactions similar to those reported in recent research and theorizing on anger and anti-social motivations.

Possible Limitations

It should be underlined that our study focused on how people in general think a family would respond to a drop out. Naturally, it would be ideal to investigate how actual families of those who drop out would respond to our research questions. Even though this might be seen as a more “natural” approach, it is useful to remember that the vignette method has been found to produce results equal to other ecological methods ( Robinson and Clore, 2001 ) only without the ethical dilemmas attached with real-world challenges. Moreover, as people are good at imagining how others and themselves would feel and do in various situations (e.g., Decety and Grèzes, 2006 ), the vignette design seems to be a useful tool on topics such as failures and how to cope with them.

That said, one should be aware of the practical and ethical difficulties to find and locate families with pupils that have dropped out of school. In relation to the practical difficulties of locating them, we can inform that we first tried to contact the two different schools mentioned in our scenario in order to gain information about the drop outs. However, we were not granted this information and were thus left in the dark in response to locating these families. That said, out of ethical concerns, families of those who drop out might already have been exposed for stigmatizing attitudes and thus have experienced many emotional and practical hardships. One can imagine that if we were to locate them, it might not be welcomed if we were to address them about something they might very well be angry about.

Another limitation rests within the participant pool. We did not check if they had background from a vocational or a general education, and thus, we cannot guarantee that this would not have influenced their perception of drop out from the one or the other educational programs. Moreover, we did not ask for, and therefore could not control for whether their level of education influenced the results in any way. That said, we aimed for a randomized pool of community participants (instead of the more “normal” student participant pool) that were more or less mature participants with a mean-age of 36 years. We do believe that these participants have enough life-experience to be more moderate in their beliefs about the world than younger ones. Hence, we rest assured that the results based on the feedback from our participants can be trusted.

Practical Thoughts

Our findings indicate that professional helpers working with drop outs might meet families that, ironically, communicate anger instead of gratitude for the help they are given. If so, it could be helpful to know that this anger is likely explained by their fear of condemnation and feared damage to their social-image as a respectable family for the “failure” to prevent their son or daughter from dropping out of an educational program. Moreover, if the family is angry at the former pupil then the professional helper might see that their anger can be explained by the worry that there is a moral failure within the family since they could not prevent the drop out. In any way, we think helpers can use our model to better understand how families cope with the social and family-related challenges that a norm violating drop out might represent.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed through the standardized checklist of the Norwegian Centre for Research Data and found not to be subject to notification. Written informed consent from the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

NG did the design and analysis and contributed to the interpretation of the data, theoretical framework and write-up, and approved submission. DB contributed to the interpretation of the data, theoretical framework and write-up, and approved submission. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Agnes Serine Bossum, Linda Lie Christensen, Cathrine Solum Hansen, and Kine Maria Laup Karlsen, Fredrikstad, Norway, for their help collecting data as part of their Bachelor-thesis.

Aftenposten (2015). Available at: https://www.aftenposten.no/meninger/sid/i/dMKq/hvorfor-maa-jeg-vaere-flau-over-aa-gaa-yrkesfag ?

Google Scholar

Arum, R., and Shavit, Y. (1995). Secondary vocational education and the transition from school to work. Soc. Educ. 68, 187–204. doi: 10.2307/2112684

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Beblavy, M., Thum, A. E., and Veselkova, M. (2011). Education policy and welfare regimes in OECD countries: Social stratification and equal opportunity in education. CEPS working document, 357. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2402726

Bénabou, R., and Tirole, J. (2004). Report No.: 230. Incentives and prosocial behavior, Discussion papers in economics/Princeton University, Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/23457

Berndsen, M., and McGarty, C. (2012). Perspective taking and opinions about forms of reparation for victims of historical harm. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 38, 1316–1328. doi: 10.1177/0146167212450322

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Christle, C. A., Jolivette, K., and Nelson, C. M. (2007). School characteristics related to high school dropout rates. Remedial Spec. Educ. 28, 325–339. doi: 10.1177/07419325070280060201

Crocker, J., Major, B., and Steele, C. M. (1998). “Social Stigma” in Handbook of social psychology . Vol. 2. eds. D. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, and G. Lindzey (Boston, MA: McGraw Hill), 504–553.

Decety, J., and Grèzes, J. (2006). The power of simulation: imagining one’s own and other’s behavior. Brain Res. 1079, 4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.12.115

Dorn, S. (1993). Origins of the “dropout problem”. Hist. Educ. Q. 33, 353–373. doi: 10.2307/368197

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Hum. Relat. 7, 117–140. doi: 10.1177/001872675400700202

Gausel, N. (2013). “Self-reform or self-defense? Understanding how people cope with their moral failures by understanding how they appraise and feel about their moral failures” in Walk of shame . eds. M. Moshe and N. Corbu (Hauppauge, NY, USA: Nova Publishers), 191–208.

Gausel, N. (2014). It’s not our fault! Explaining why families might blame the school for failure to complete a high-school education. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 17, 609–616. doi: 10.1007/s11218-014-9267-5

Gausel, N., and Leach, C. W. (2011). Concern for self-image and social-image in the management of moral failure: rethinking shame. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 41, 468–478. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.803

Gausel, N., Leach, C. W., Mazziotta, A., and Feuchte, F. (2018). Seeking revenge or seeking reconciliation? How concern for social-image and felt shame helps explain responses in reciprocal intergroup conflict. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 48, O62–O72. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2295

Gausel, N., Leach, C. W., Vignoles, V. L., and Brown, R. (2012). Defend or repair? Explaining responses to in-group moral failure by disentangling feelings of shame, inferiority and rejection. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 102, 941–960. doi: 10.1037/a0027233

Gausel, N., Vignoles, V. L., and Leach, C. W. (2016). Resolving the paradox of shame: differentiating among specific appraisal-feeling combinations explains pro-social and self-defensive motivation. Motiv. Emot. 40, 118–139. doi: 10.1007/s11031-015-9513-y

Grootaers, D., Franssen, A., and Bajoit, G. (1999). Mutations de l’enseignement technique et professionnel et différenciation des stratégies éducatives (Communauté française de Belgique). Cahiers de la recherche en éducation 6, 21–55. doi: 10.7202/1017010ar

Hauser, R. M., Warren, J. R., Huang, M. H., and Carter, W. Y. (2000). “Occupational status, education, and social mobility in the meritocracy” in Meritocracy and economic inequality . eds. K. Arrow, S. Bowles, and S. Durlauf (Princeton, NJ: Univ. Princeton Press), 179–229.

Hebl, M. R., King, E. B., Glick, P., Singletary, S. L., and Kazama, S. (2007). Hostile and benevolent reactions toward pregnant women. Complementary interpersonal punishments and rewards that maintain traditional roles. J. Appl. Psychol. 92, 1499–1511. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.6.1499

Karmel, T., and Woods, D. (2008). Second chance vocational education and training . Adelaide: National Centre for Vocational Education Research.

King, E., Knight, J., and Hebl, M. (2010). The influence of economic conditions on aspects of stigmatization. J. Soc. Issues 66, 446–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2010.01655.x

Lerner, M. J. (1980). The belief in a just world: A fundamental delusion . New York: Plenum.

Major, B., and O’brien, L. T. (2005). The social psychology of stigma. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 56, 393–421. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070137

Miller, R. S., and Tangney, J. P. (1994). Differentiating embarrassment and shame. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 13, 273–287. doi: 10.1521/jscp.1994.13.3.273

Robinson, M. D., and Clore, G. L. (2001). Simulation, scenarios, and emotional appraisal: testing the convergence of real and imagined reactions to emotional stimuli. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 27, 1520–1532. doi: 10.1177/01461672012711012

Scabini, E., and Manzi, C. (2011). “Family processes and identity” in Handbook of identity theory and research. eds. S. J. Schwartz, K. Luyckx, and V. L. Vignoles (New York, NY: Springer), 565–584.

Spruyt, B., Van Droogenbroeck, F., and Kavadias, D. (2015). Educational tracking and sense of futility: a matter of stigma consciousness? Oxf. Rev. Educ. 41, 747–765. doi: 10.1080/03054985.2015.1117971

Täuber, S., Gausel, N., and Flint, S. W. (2018). Weight bias internalization: the maladaptive effects of moral condemnation on intrinsic motivation. Front. Psychol. 9:1836. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01836

Van Hoorn, A., and Maseland, R. (2013). Does a protestant work ethic exist? Evidence from the well-being effect of unemployment. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 91, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2013.03.038

Weiner, B., Perry, R. P., and Magnusson, J. (1988). An attributional analysis of reactions to stigma. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 55, 738–748. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.55.5.738

Zahl-Olsen, R., Gausel, N., Zahl-Olsen, A., Bjerregaard, B. T., Håland, Å. T., and Tilden, T. (2019). Physical couple and family violence among clients seeking therapy: identifiers and predictors. Front. Psychol. 10:2847. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02847

Keywords: self, social, image, dropping out, school, anger, stigma, family

Citation: Gausel N and Bourguignon D (2020) Dropping Out of School: Explaining How Concerns for the Family’s Social-Image and Self-Image Predict Anger. Front. Psychol . 11:1868. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01868

Received: 12 February 2020; Accepted: 07 July 2020; Published: 04 August 2020.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2020 Gausel and Bourguignon. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nicolay Gausel, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Reflections on “Dropping Out” of School

Meeting the challenge of youth engagement

by: George J. Sefa Dei

date: June 4, 2015

What are the transformative possibilities of schooling and education today? I answer this question with two words: hope and caring. I am hopeful that we can begin to address the problem of school dropouts. I also believe strongly that most educators care about and want the best for their students. However, as many educators have also noted, sometimes our good intentions are not enough. We need to focus on the effects and outcomes of our practices. 1 It is imperative that as educators and practitioners, we take students’ perceptions seriously and examine our practices and beliefs to ensure that students get to know who we truly are, that we do care about learning, teaching and administration of education and that we are intent on creating an inclusive learning environment for all.

In the early 1990s, I led a longitudinal study examining Black youths and the Ontario public school system. We concluded that the term “push out” was more appropriate than “drop out.” 2 Our contention was not that educators literally push students out of the door. However, the messages sent by schools – what is valued and deemed legitimate knowledge, what is discussed or not discussed in classrooms, what experiences and identities count or do not count, and how students are perceived by educators – lead a fair number of Black youth to feel unwelcome and, consequently, become disengaged. It is no longer acceptable for educators and local communities to accept dropping out as simply a matter of individual responsibility. So how do we interrogate conventional knowledge?

Tuck, in an excellent read, discusses how schools push out students through humiliating experiences and assaults on learners’ dignities such that these students no longer want to be in school. She reasons that U.S. schools produce dropping out as a “dialectic of humiliating ironies and dangerous dignities” 3 that stem from educational practices including assessments, exit exams, testing, and school rule enforcements that students find very humiliating. Clearly, when students leave school prematurely they are fully aware of the consequences of their decision in the context of the social and cultural capital assigned to education. Therefore, we must seek to understand why students make these decisions and acknowledge the interplay of institutional and personal responsibilities when accounting for school dropouts.

What educational research in Ontario tells us

Statistics can help us establish the nature and context of a problem. However, considering the general reluctance to engage with race, recent statistics often employ coded language to speak about the experiences of racialized students. For example, studies often focus on language, country of origin, length of time in Canada, or citizenship status as it relates to student disengagement. These studies can provide a glimpse into the issue, though without an honest conversation about the role of race, it remains an incomplete picture.

Research conducted by the Toronto District School Board (TDSB) on dropping out by key languages shows that Portuguese-, Spanish-, and Somali-speaking students leave school at the highest rates: 38 percent, 37.5 percent, and 35.1 percent respectively. 4 By region of birth, English-speaking Caribbean and Central/South American and Mexican students leave at the highest rates, 38 percent and 37 percent. 5 Combined with earlier statistics, these indicate issues that extend above and beyond language and place of origin and point, instead, towards a hostile learning environment for racialized students.

Educational research on the performance of Ontario high school students shows that despite successes, Black/African-Canadians, First Nations/Aboriginals, and Portuguese- and Spanish-speaking students are at the forefront of student disengagement from school. 6 Disproportionate numbers of students from these groups are also enrolled in special education and non-university stream programs. 7 Even for those students alleged to be doing well (e.g. Asian “model minority” students) we observe narrow fields of academic choices, such as the over-subscription in science/mathematics-related occupations. 8

But the figures do not tell us about the human side of dropping out. In our study, we noted the human dimensions to the story of Black and minority youth disengagement from school. These are stories of personal struggles, of family and home hardships, socialization and peer culture struggles – of youth with stolen dreams and unmet expectations who develop a lack of faith in the system. There are also the challenges of navigating the school system, unfriendly and unwelcoming schooling environments, low teacher expectations of minority students, the differential treatment by race, gender, sexuality or class, and the lack of curricular, pedagogic and instructional sophistication. 9 For Black/African students, the cost of school/academic success may be one’s identity and emotional stability. 10 The process of disengagement starts early in the life of the student, culminating in the decision to leave school prematurely.

This calls for a critical interrogation of the structures and processes of educational delivery. Such interrogation allows us to hold systems accountable while also calling for community and parental responsibility. Producing school success is more than an individual undertaking. In asking parents and communities to share responsibility for the education of their children, we must avoid pathologizing families, individual learners and their communities. Such pathologies only reinforce constructed or false negatives of marginalized (working class and racialized) communities and stifle counter-debate. We often throw out the term “taking responsibility” without situating discussions with the recognition that taking on responsibility is only possible when we have the means to support our actions. It easy to sit in the comfort of one’s living room and say, “Gee… these people must take responsibility.”

Hence, in addressing youth dropping out of school we can maintain blind spots on the daily struggles and challenges of families and their resilience to succeed against all odds – and fail to learn from these real-life struggles. We do not value counter- and oppositional stances; yet, it is these counter-stances and strategies of resilience that offer crucial lessons for re-visioning education and thereby promoting change.

Dropping out: philosophical contentions

Rather than pinpoint specific causes and factors contributing to youth dropping out of school, I want now to work with a different intellectual gaze, highlighting some philosophical contentions. I see such analysis as part of a needed paradigmatic shift to understand schooling and education. A major discursive position I am taking is that dropping out is actually a consequence of the structure of the Euro-Canadian/American educational school system, and the collective inability or failure to look at its foundations. The foundation itself contributes to students dropping out – yet we are adding stories to a weak foundation rather than building a new one.

The current school system focuses on individual excellence and success. There is a heavy play on meritocracy, which promotes and sustains rugged individualism and competition. The values and credentials privileged by the Euro-American school system simply mask Whiteness, White power and privilege as the norm. What is presented as “universal” is, in fact, the particularity of the dominant. The values of the dominant that undergird the educational system do not hold for everyone. They are being questioned not because they are wrong, but because they are not universally tenable. They are not inclusive and we need to cultivate values shared by all of our humanity.

We are all in a collective struggle to transform our communities; we are each implicated in the existing inequities.

The implication for dropping out is that the absence of a “school community of learners” they can identify with makes some students feel alienated and disengaged. For example, while a competitive mode may help generate individual brilliance and creativity, it does not necessarily create sustainable communities for everyone. We need to bring back a positive reading to “community.”

It’s important to recognize that we are all in a collective struggle to transform our communities; we are each implicated in the existing inequities. As an educational response we must have all hands on deck, with value given to everyone’s knowledge, history, experience and contributions. This includes students, educators, administrators, policy makers, private, business and public sectors and parents, guardians, community workers and our varied communities – and especially dropouts. We cannot find solutions outside the contributions, experiences and voices of the school dropouts themselves.

Integrating learners into society is seen as an important mission of school. In Canada, there is unquestioned faith in integration, which is rooted in the multicultural paradigm. Our approach to integration is one size fits all. Those who do not fit are cast aside. But we must begin to ask: Integration for whom, how and at what/whose expense? Those who drop out do not find a place in the school system as currently designed. One size cannot fit all. Multiple visions of schooling, including educational innovations and initiatives from marginalized communities, must be envisaged and encouraged. They must equally be valued, promoted and supported. At the policy level, it is troubling to see how a blind faith in integration continues to lead even non-dominant, immigrant, racial minority, and Indigenous learners along the path of “cultural destruction.”

We cannot hope for success while continuing to do the same thing that is failing us. The denial of White dominance distorts reality and does not allow us to put our collective hearts and minds together to find solutions. We have not developed any explicit investment in creating a level playing field. This is because we have failed to recognize the uneven and inequitable circumstances in which education is embedded – the a priori inequality existing among students, within school cultures and educational discourse and in the Euro-American curricula. Teaching and learning should be about decolonizing minds, bodies, souls and spirits to be more critical of ourselves and of our communities.

Strategies for student retention

Dropping out of school is fundamentally a problem of youth disengagement from and disaffection with school. While solutions must embrace school, home and community connections, there are also some concrete strategies that educators and administrators can undertake to retain students in schools.

Many of the strategies discussed here relate to inclusion issues. I am increasingly skeptical of the bland and depoliticized talk of inclusion that ignores issues of power, transparency and accountability. I believe inclusion should lead to structural transformation rather than simply adding to what already exists, since oftentimes what already exists is the source of the problem. Instead, I want to work with “radical inclusion.” We need to recognize the space in between ourselves and others, where all the history, pain, trauma, resistance and love live, in order to see inclusion as about a wholeness, completeness and varied, complex communities.

Education must work with students’ lived experiences, myriad identities, histories, cultures, and knowledge bases – in other words, it must be meaningful and relevant to the students themselves. A holistic education should encompass the material, social, cultural, political, physical, psychological, spiritual and metaphysical realms of learners’ existence, including teaching about society, culture and Nature (i.e. environments and Lands). We need to reclaim multiple and multi-centric ways of knowing. Such knowledges are key to affirming learners’ and educators’ myriad identities, histories and social contexts of learning and teaching; promoting Indigenous cultures and language heritages; and addressing broader questions of curricular, instructional and pedagogic relevance.

All students must feel included and welcome in our schools. Identity is linked with knowledge production. Teaching must recognize the myriad identities that our learners bring to classrooms (e.g. racial, gendered, classed, sexual, (dis)abled). These social differences implicate schooling and are consequential for educational outcomes. Therefore, educators should teach about social difference as sites of power, strength and identity. Teaching must engage the home and community cultures of students. Local and Indigenous languages of learners must be broached alongside teaching in dominant lan-guages. Students must see themselves reflected in the school culture and in the visual and physical landscape of their schools. A diverse teaching and administrative staff will allow students to identity with people in positions of power and influence as equally coming from their own communities.

It is important for educators to access pertinent resources for developing an inclusive curriculum. Students themselves can be used as knowledge holders of their own experiences; parents, Elders, and guest speakers from diverse backgrounds can be welcomed as teachers engaging in multiple conversations with students and staff. Public conferences, seminars and community workshops, local print media and television, community bookstores and public libraries, and popular culture are all resources for youth education. These resources can be employed with a discussion of their social contexts and histories as entry points of dialogues.

Nasir highlights “four aspects of teaching and learning that support this sense of belonging and identification: fostering respectful relationships, making mistakes acceptable, giving learners defined roles, and offering learners ways to participate that incorporate aspects of themselves.” 11 These strategies hold lessons for the classroom. Fostering respectful relationships and making mistakes an acceptable part of the learning process can create cohesion, a sense of community, and build confidence by reframing failure as an opportunity to learn and grow. Defining informal roles based on interests and strengths gives learners a sense of expertise and a valued identity within the group.

Educators should strengthen students’ abilities to ask new and difficult questions in class. The students can begin by questioning their own selves and local communities, the school and wider society. Teaching should also emphasize learners’ responsibilities to their communities, peers and to themselves. Allowing all students to showcase their own voices and knowledges, and to reflect on and assess their own schooling, are important educational strategies of inclusion. Prioritizing students whose voices and knowledges are absent is critical. Educators can also examine their own classroom pedagogies, diversifying the curriculum through the infusion of multiple teaching methodologies. For example, there must be a consideration of more dialogical curriculum co-creation involving students, parents, local communities, and schools. 12

Educators must re-conceptualize rigid Euro-centered evaluation and assessment methods and work with multiple definitions of success. Classrooms should promote collective successes, with evaluations taking into account how students are supporting each other. A failing class would be one that could not support all its members. We could evaluate on the basis of improvement. We can introduce peer reviews and grading, so that the teacher is not solely in control of grades and the hierarchies are less severe.

Educators can recognize and honour multiple ways of knowing and being by enabling students to be creative and present non-traditional papers (arts-based, multimedia). 13 We can consider orality as an equal medium to written text. Educators must include community-based events, which often provide access to Elders or other “teachers,” as sites of learning. School-based learning becomes more meaningful and practical when students can connect it to community work.

These strategies allow students to develop a sense of ownership of their knowledge and knowledge creation process.

Decolonizing education is about looking critically at the structures and processes of educational delivery and changing the ways we teach, learn and administer education. Decolonizing education is about promoting counter and oppositional voices, knowledges and histories, bringing into focus the lived experiences of students who have been marginalized from the school system. Through inclusive practices that engage the diverse group of learners, schools can become welcoming spaces, and the resulting sense of belonging and ownership of the schooling process can help engage students and allow them to stay in school. It is difficult to understand why someone who feels welcome, valued, and engaged will decide to leave school prematurely.

Thanks to Kate Partridge of the Department of Social Justice, OISE/UT, for commenting on an earlier draft of this article.

En Bref – Comment peut-on revoir la scolarisation en fonction des besoins des élèves différents? Dans cet article, George J. Sefa Dei réfléchit aux liens existant entre le décrochage scolaire et les pratiqueséducatives (enseignement, pédagogie et initiatives liées au curriculum, ainsi que culture d’école) qui sont et peuvent être documentées par les apprenants, leurs histoires, identités, mémoires culturelles et patrimoines, ainsi que par leurs expériences et attentes de tous les jours. Il confronte des questions difficiles relatives au pouvoir, au discours et à la représentation des expériences des jeunes qui provoquent et contextualisent le décrochage scolaire. Il se demande comment nous pouvons commencer à démanteler les relations hiérarchiques du pouvoir liées à la scolarisation. Il examine également certains facteurs conventionnels menant au décrochage scolaire et suggère aux éducateurs et aux écoles des façons pouvant favoriser la rétention et la réussite. Il est reconnu que le milieu de scolarisation peut être inhospitalier pour les élèves ne faisant pas partie de la culture dominante (marginalisés par la race, le genre, la sexualité, la classe, etc.) et qu’en décolonisant l’éducation, plus d’élèves auront un sentiment d’appartenance et s’approprieront leur éducation.

Photo: Rich Legg (iStock)

First published in Education Canada, May 2015

1 M. Fine, Framing Dropouts: Notes on the politics of an urban public high school (New York: State University of New York Press, 1991).

2 G. J. S. Dei (with L. Holmes, J. Mazzuca, E. McIsaac, and R. Campbell), Drop Out or Push Out? The dynamics of Black students’ disengagement from school. Report submitted to the Ontario Ministry of Education and Training, 1995; G. J. S. Dei, J. Mazzuca, E. McIsaac, and J. Zine, Reconstructing “Dropout”: A critical ethnography of the dynamics of Black students’ disengagement from school (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997).

3 E. Tuck, “Humiliating Ironies and Dangerous Dignities: A Dialectic of school push out,” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 24, no. 7 (2011): 817.

4 R. S. Brown, Research Report: The Grade 9 Cohort of Fall 2002: A five-year cohort study, 2002-2007 (Toronto: Toronto District School Board, 2008),16. www.tdsb.on.ca/Portals/0/AboutUs/Research/The%205%20Yr%20Study%2002-07.pdf

5 R. S. Brown, Research Report (2008).

6 R. S. Brown, A Follow-Up of the Grade 9 Cohort of 1987 Every Secondary Student Survey Participants (Toronto: Toronto Board of Education, Research Services, Report No. 207, 1993); M. Cheng, M. Yau, and S. Ziegler, The Every Secondary Student Survey, Part II: Detailed profiles of Toronto secondary school students (Toronto: Toronto Board of Education, Research Services, Report No. 204, 1993).

7 R. S. Brown and G. Parekh, Research Report: Special Education: Structural overview and student demographics (Toronto: Toronto District School Board, 2010), 35.

8 M. Cheng, “ Factors that Affect the Decisions of Racial/Ethnic Minorities to Enter and Stay in Teaching and their Implications for School Board’s Teacher Recruitment and Retention Policies” (Ed.D diss., Department of Sociology and Equity Studies, OISE/UT, 2002).

9 Fine, Framing Dropouts ; Dei et al., Drop Out or Push Out?

10 Dei et al., Reconstructing “Dropout”; G. J. S. Dei, “Schooling and the Dilemma of Youth Disengagement,” McGill Journal of Education 38, no. 3 (2003): 241- 256.

11 N. Nasir, “Everyday Pedagogy: Lessons from basketball, track, and dominoes,” Phi Delta Kappan 89, no. 7 (2008): 530.

12 G. J. S. Dei, “Decolonizing the University Curriculum,” Socialist Studies/Etudes Socialistes 10, no. 2 (forthcoming: June 2015). www.socialiststudies.com

13 Dei, “Decolonizing the University Curriculum.”

Meet the Expert(s)

George j. sefa dei.

George J. Sefa Dei (Nana Adusei Sefa Atweneboah I) is Professor of Social Justice Education at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education of the University of Toronto (OISE/UT), Director for the Centre for Integrative Studies at OISE/UT and Carnegie African Diaspora Fellow. His teaching and research interests are in the areas of anti-racism, minority schooling, international development, anti-colonial thought and Indigenous knowledges systems. He has published extensively on African youth education, anti-racism, Indigenous knowledges and anti-colonial thought.

1 /5 Free Articles Left

LOGIN Join The Network

It looks like you've read all of your free articles.

Join the EdCan Network

Join the EdCan Network now for unlimited access to thousands of online articles, to receive our print magazine and access special discount programs.

Thousands of courageous educators rely on our network for content and analysis that can support them working under the radar to reach every learner despite the limitations imposed by the system. You can too.

Not ready to join right now? Check out EdCan Wire for more free content.

It looks like this page isn't available in French.

IDEAS TO SUPPORT EDUCATORS : Subscribe to the EdCan e-Newsletter

Quality research, reports, and professional learning opportunities.

Language Preference Langue de correspondance English Français English Français

- Share full article

Advertisement

Why School Absences Have ‘Exploded’ Almost Everywhere

The pandemic changed families’ lives and the culture of education: “Our relationship with school became optional.”

By Sarah Mervosh and Francesca Paris

Sarah Mervosh reports on K-12 education, and Francesca Paris is a data reporter.

In Anchorage, affluent families set off on ski trips and other lengthy vacations, with the assumption that their children can keep up with schoolwork online.

In a working-class pocket of Michigan, school administrators have tried almost everything, including pajama day, to boost student attendance.

And across the country, students with heightened anxiety are opting to stay home rather than face the classroom.

In the four years since the pandemic closed schools, U.S. education has struggled to recover on a number of fronts, from learning loss , to enrollment , to student behavior .

But perhaps no issue has been as stubborn and pervasive as a sharp increase in student absenteeism, a problem that cuts across demographics and has continued long after schools reopened.

Nationally, an estimated 26 percent of public school students were considered chronically absent last school year, up from 15 percent before the pandemic, according to the most recent data, from 40 states and Washington, D.C., compiled by the conservative-leaning American Enterprise Institute . Chronic absence is typically defined as missing at least 10 percent of the school year, or about 18 days, for any reason.

Source: Upshot analysis of data from Nat Malkus, American Enterprise Institute. Districts are grouped into highest, middle and lowest third.

The increases have occurred in districts big and small, and across income and race. For districts in wealthier areas, chronic absenteeism rates have about doubled, to 19 percent in the 2022-23 school year from 10 percent before the pandemic, a New York Times analysis of the data found.

Poor communities, which started with elevated rates of student absenteeism, are facing an even bigger crisis: Around 32 percent of students in the poorest districts were chronically absent in the 2022-23 school year, up from 19 percent before the pandemic.

Even districts that reopened quickly during the pandemic, in fall 2020, have seen vast increases.