- Skip to main content

India’s Largest Career Transformation Portal

Essay on Cultural Transformation in 21st Century

June 4, 2019 by Sandeep

We are living in a highly privileged society where families have transformed from joint set-up to single, individual or nuclear families. Cultural know-hows of one generation usually gets passed on to the next generation through word-of-mouth and continuous practice.

Institutionalisation of science in society

The term ‘institutionalisation’ refers to the standardisation or making/building a standardised pattern over the years. People living in a society begin to accept these norms or set patterns as part of their living and think that they have to live by these norms each and everyday of their lives.

This is where the concept of ‘institutionalisation’ sets in. Our society relies on education for their fundamental living, for finding jobs and getting better plans in society. It is education that culturally guides them to extend cordial behaviour and live in co-operation and harmony with others.

From our forefathers, we have inherited the spirit of scientific thinking. Science is the abstract knowledge or the core institution that we fundamentally received from our ancestors. The turning point or the application of this knowledge in user specific ways has created more modern society for us.

But the scientific institution from where we received and are passing on the basic fundamentals remain unchallenged. People have moved beyond this institution and not challenged scientific ethics after a certain point. The challengers lie in effective utilization of resources for meaningful and purposeful services to mankind.

Adaptive changes in religious values and beliefs

With time and technological advancement, reasoning and scientific temper replace age-old traditions, customs, religious beliefs and orthodox values. The aspect of ‘questioning’ our customs is not a very healthy motion though. Many traditional practices that were followed still have a connection with the world of science, only if we dug deeper into the subject matter.

The relation or inter-connection would be lost or forgotten in the course of time leading to selective changes and adaptive transformations in the way we see and understand religion and traditions as a whole. Religion should be a part of cultural upliftment and not a barrier in itself.

Indian society at crossroads

The older generations are now opening up to accept good and collective points of other cross cultures as well. We can broadly say that Indian culture to some extent has had a shadow of British influence in the past. Nevertheless our ancestors made sure to pull it back and behold the cultural enigma in a nutshell and preserved if for years. The grandeur of this lost tradition was somehow protected and put in its place.

With time, our people have got falsely attracted to pseudo western values and cultures making them think twice about embracing their own culture. For example, yoga practices are part and parcel of our own Indian culture, slowly making big business in the west. The Indian community embraced yoga to greater levels after the western community gave it recognition. Definitely, Indian society is at crossroads.

Process of social restructuration

They say, father is the head of the family and it’s good to have the whole family for dinner. This was a thing of the past. Now, our lives are ruled by gadgets, people work in flexible hours and the cultural togetherness has become more of a matter of social re-union.

Earlier, joint families played a very vital role in our society. The older and younger generations interacted with each other and perceived, understood and imbibed our cultural values. When this set-up got slowly replaced by a nuclear family setup, cultural value transfer took a backseat. Time for daily chores, the need for one’s independence, career boost and gained more and more importance leading to severe social restructuration.

Paradigm shift in Indian philanthropy

India is a country with a lot of social issues. Some have been addressed, others are yet to gain a platform. ‘Giving’ has been a part of our greater culture since years. Apart from the common man who ‘gave’ to society-in-need in the form of charity, rulers, beings and their counterparts donated for the welfare of society and people.

In today’s world ‘giving’ is no more a fancy word found in cultural textbooks, it is part of a greater form of ‘contribution’. NGOs make name and fame by being part of this ‘philanthropy’! People do not necessarily refer to their culture to be part of philanthropy.

They seek relief from their taxable income, so as a means to their financial upliftment too, things have taken a dramatic change. For good reasons and on value based moral grounds, philanthropy has more outreach with advanced technology, people contribute in modern ways and has become a synonymous task with politicians too.

Emergence of new classes

When India was created an economic grounds, the backward classes or peeres classes took the lowest stream in society, followed by the middle class and then the upper class. The cultural values travelled in the other way, the upper class believed to be culturally more significant too.

The situation today is different. We have the modern class which is believed to be flying high with modern waves, yet has a touch of cultural roots attached to it. The ultra-modern classes that are believed to be taken off the cultural radar and living in a liberal society.

The gates-buffet model

People of the younger generation discard their cultural connection, way ahead to see a path of money making. Today, their role models are based on the likes of Gates and Waren Buffet. What makes this model interesting is the five fold theory it is composed of. The first working principle is the glory built with the vision they sought in their minds. People get attracted to the beauty of this glory.

The second principle is ruling out distractions on the way and focusing on the path to success. The third principle exemplifies efficiency, perseverance in our tasks. The fourth principal talks about is social status and well being arising out of his work. The fifth principle exudes inspiration to others on account of our well being.

These words are seen in role models like Gates and Buffet as per the choices of the present generations. In reality, these words can be found way back in our Bhagavad Gitta and has been treasured for long in our cultural values.

Decline of traditional cultural institutions

Religion is different from culture. Religion lays down certain principles that have to be followed in order to practice and preach specific belief. Culture on the other hand teaches a humane way of leading life. No religious text book will go far without the periphery of culture. Religion is the inner stuff and culture is like the extend contact periphery that helps follow religion in the righteous way.

For long, India has been a place of cultural extravaganza and is rich in its value-system. But slowly, due to the mindset prevailing and a bid to take people off their cultural roots, things like corruption and other social evils are thriving.

Traditional cultural institutions in the form of Gurukuls imparted knowledge and education to children in earlier days. The British invasion in India brought along formal education system and also imposed syllabi and rote learning methods.

So, to a great extent, christian missionaries had a very huge impact on our education system. To a certain known perimeter, our culture and values still found a place in these textbooks but with modernity, that started deciling.

India still has its huge share of institutions concerned with the likes of cultural roots of India. Things look bleak when we see the number of patrons and the general public associated with these institutions. Though they impart cultural knowledge in their medium, the number of takers are scanty. There is demand for knowledge in the cultural sphere, but people prefer going the western way.

Social Mobility

Travelling to foreign shores in olden days was considered a taboo. Such practices had no base and were precariously removed. Many such upliftment were a welcome move. Along with this, population shift towards the European and American countries began with a steady rise.

So, we could see cross culture exchanges happening at a fast rate. This mixed with other cultures and gave rise to a new concepts of multi-lingual, multi-ethical culture. These days our cultural system is more accessible, acceptable and mobile too.

Composite culture of India

India is not just about Indians. We have people across nations, finding homes here. That is an external bird view. Internally within our own country, we have people from diverse cultures, of various beliefs and values coming together, tying themselves up on the common ground of being an Indian.

The composite cultural makeup of India has led to the concept of unity in diversity. We are one nation but we follow different religions, speak different languages, have cultural difference, yet accept each other on the sole grounds of being on Indian first.

With cross cultural interactions and multi ethnic cultures making in roads and affecting our values in small and big ways, there sure is a long way ahead to be travelled.

Cultural migration in India

Be it festivals, food practices, important days, ceremonies or events, there is a natural cultural affiliation attached to each one of them. Overtime, things change, get more updated with the time and that is when we see apart of our practices seeking a migration.

We can definitely see our cultural systems seeking more modern ways and approaches that suits different mindsets. It is about opening up to allow fresh cease of air. While letting out those threads that seems outdated and irrelevant at present times.

Modernism & traditional socio-ethical values

When we see modernisation of our culture, it does not mean leaving behind what was there and bringing in something that was non-existent. The concept of modernism in cultural contexts simply mean that we move ahead with our times. In a traditional social set-up, the families refrained from staying differently in individual houses. A joint set up with a primary head of the family was the norm.

Today we have small units living happily in cities. It is a necessity today. We no longer see large, joint family systems everywhere. It has become a rarity now. This concept does not mean that people have forgotten their ethics or customs or traditions. They still follow them. Festivals are still celebrated at homes. Only the way in which it is celebrated must have changed, owing to changing times and traditions.

Occupational diversification

Earlier a son used to carry on his father’s business and this continued for many more generations in the future. Today, if the father is in a particular city, his son may be working on an offshore unit. Times have changed occupations and opportunities have diversified mindsets have also changed accordingly. The bonding and cultural roots remain the same. But that does not inhibit a person to explore out of his boundary.

Cultural values impart good ethics in humans. Indians have always been enriched culturally. Indians are known for their good culture and mannerisms. No matter where we are employed or where we study, we should leave behind our negative traits. We should not forget our cultural setups and values that we are made of.

Transformations happen in the world at every sphere and every aspect of life. With improved science and technology, lives are more modernised. Thinking and reasoning has changed. People go back to their cultures as a reference point.

Racial and Cultural Diversity in the 21st Century Essay

Cyberbullying, society in the 21st century: connected leadership, society in the 21st century: developmental trends.

The concepts of multiculturalism and diversity are related to the ethnic and racial composition of the population. Various cultural traditions, values, and customs significantly influence individuals and shape their self-identity because as a person grows, he or she adopts particular behavioral pertinent to his/her social environment. In this way, individuals’ cultural identity defines their actions, decisions, social orientations, and preferences. Thus, leaders and advocates in the field of human behavior should be aware of these multicultural differences, their effects on individuals’ conduct, as well as their relationships to various social issues such as oppression and discrimination (NASW, 2014).

In the professional performance requiring an unprejudiced attitude, such as counseling, cultural biases may create significant barriers to the provision of high-quality service. Prejudices based on the demographic factors interfere with the establishment of professional relationships and increase misunderstanding. Therefore, the development of awareness of own cultural and social biases may be regarded as the initial phase in increasing multicultural competence. Hays (2008) suggests to analyze own cultural heritage and develop the understanding of how cultural values affect interactions with diverse people. When a person shows the willingness to change shehe becomes more open to the reception of new knowledge, the transformation of a cultural perspective, as well as the development of new personal and cultural values. In the field of human behavior, it is possible to build intercultural competence through the investigation of relevant ethical standards and multiple informational sources. It can be useful to develop relationships with diverse people within the multicultural professional or academic contexts. The development of cultural awareness is essential for every advocate and leader, and it is an intrinsic part of the professional competence which is liable for the successful communication, maintenance of objectivity, and compliance with a significant number of ethical standards and principles.

Nowadays, communication via online social networks is widespread. Although the use of the Internet is beneficial in many spheres of life, it also can negatively impact human lives when misused. Cyberbullying is a contemporary topical issue that affected millions of children and teenagers. According to the recent statistics, over 25 percent of adolescents are repeatedly exposed to bullying through their cell phones, and online pages and less than one out of five incidents of cyberbullying are reported (“Cyberbullying statistics,” 2016). Unlike offline bullying, cyberbullying is anonymous, and it makes the identification of offenders almost impossible. At the same time, any form of bullying is detrimental to victims’ psychological and social well-being. For these reasons, the prevention of the problem is one of the major public concerns.

The preventive strategy may include the following activities: educating youth on how to react to cyberbullying incidents, promoting a supportive environment in schools, designing and enforcing relevant policies. To engage adolescents in prevention endeavors, the strategy should be aligned with their interests and needs. The personal benefits which the young people may gain through the involvement include academic success, friendships, improved peer communication, emotional health, and so on. The major barrier to the implementation of the strategy is the sense of bullies’ invincibility because they remain faceless in the cyberspace. However, by improving the school climate, we may promote the understanding that the problem can be inhibited. As Notar, Padgett, and Roden (2013) state, “bullying is mainly framed as an issue of the school climate on the part of the participants” (p. 136). Based on this, to prevent bullying, it is essential to develop a safe, respectful, and positive school environment as it may play an important role in preventing cyberbullying.

Staying connected to forces that impact society is one of the essential developmental trends in the 21st century. According to Marx (2006a), the connected leadership implies the acknowledgment of “the political, economic, social, technological, environmental, demographic, and other forces that are affecting the whole of society” (p. 5). The assessment of potential impacts these environmental factors may have on organizations and systems is one of the most efficient external scanning tools. By evaluating the community in which the organization is located, leaders become able to create an appropriate vision and formulate relevant goals that will worth striving for.

When pursuing synergy with and close connections to society, organizations should also analyze their abilities to become better. For this reason, Marx (2006b) suggests using the internal scan instruments such as review of the corporate history, culture development, evaluation of financial health, improvement of the organizational image, and so on.

The development of corporate culture may be regarded as one of the best tools for the improvement of organizational connectedness to the external environment. Organizational culture is a complex of values, norms, and behaviors shared among all employees, and it affects the representation of a company in the society, its image, and perceptions held by stakeholders (Tilchin & Essawi, 2013). Thus, as a leader, I will strive to incorporate the essential ethical and social values into everyday organizational practices and activities. The process of cultural development should start from the evaluation of stakeholders’ interests, needs, and concerns, as well as the current external developmental tendencies. With consideration of the accumulated data, our organization will modify the current mission and generate new values which will consequently be manifested in employees’ professional behaviors and attitudes. Through the incorporation of the social values into the corporate culture, the organization may raise public awareness regarding the up-to-date social problems and encourage the movement towards their resolving. In this way, the firm will manifest itself as a responsible corporate citizen and gain public trust. Based on this, it is possible to say that the establishment of the stakeholder dialogue and the improvement of stakeholder relationships through value creation are highly beneficial.

“Continuous improvement will replace quick fixes and defense of the status quo,” “Scientific discoveries and societal realities will force widespread ethical choices,” and “Polarization and narrowness will bend toward reasoned discussion, evidence, and consideration of varying points of view” are among the sixteen societal trends proposed by Marx (2006b, p. 6). The trends have some serious implications for both social and professional development as, due to the increase in the international links, people become more and more aware of multicultural differences but do not understand how to deal with them so far. The given trends emphasize the need to embrace diversity and innovation, practice accountability, and consider multiple points of view.

Leadership plays an essential role in bringing positive changes to the community. Additionally, by monitoring the developmental trends, leaders become able to spot the upcoming problems and crises beforehand and undertake measures to avoid them. To maintain continual learning and encourage innovation in my professional practice, I will try to promote an interdisciplinary management approach. Being transformative does not necessarily imply inventing new things out of nothing but rather means using the available resources in a new way (Kim, 2015). By encouraging interdisciplinary discussions, we may consider multiple perspectives on various issues more efficiently and develop a holistic picture of problems. By doing so, we may significantly increase the organizational and community fitness to the ever-changing environment, become more responsive to the needs of stakeholders, and support social sustainability.

Cyber bullying statistics . (2016). Web.

Hays, P. A. (2008). Looking into the clinician’s mirror: Cultural self-assessment. In P. A. Hays (Ed.), Addressing cultural complexities in practice: Assessment, diagnosis, and therapy (pp. 41–62). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Kim, S. (2015). Interdisciplinary approaches and methods for sustainable transformation and innovation. Sustainability, 7 (4), 3977-3983. Web.

Marx, G. (2006). Using trend data to create a successful future for our students, our schools, and our communities . Web.

Marx, G. (2006). Future-focused leadership: Preparing schools, students, and communities for tomorrow’s realities . Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development

National Association of Social Workers. (2014). The importance of cultural competence in social work practice . Web.

Notar, C., Padgett, S., & Roden, J. (2013). Cyberbullying: Resources for intervention and prevention. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 1 (3): 133-145.

Tilchin, O., & Essawi, M. (2013). Knowledge management through organizational culture change. International Journal of Business Administration 4 (5), 24.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, August 13). Racial and Cultural Diversity in the 21st Century. https://ivypanda.com/essays/racial-and-cultural-diversity-in-the-21st-century/

"Racial and Cultural Diversity in the 21st Century." IvyPanda , 13 Aug. 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/racial-and-cultural-diversity-in-the-21st-century/.

IvyPanda . (2020) 'Racial and Cultural Diversity in the 21st Century'. 13 August.

IvyPanda . 2020. "Racial and Cultural Diversity in the 21st Century." August 13, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/racial-and-cultural-diversity-in-the-21st-century/.

1. IvyPanda . "Racial and Cultural Diversity in the 21st Century." August 13, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/racial-and-cultural-diversity-in-the-21st-century/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Racial and Cultural Diversity in the 21st Century." August 13, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/racial-and-cultural-diversity-in-the-21st-century/.

- Cyberbullying and Bullying: Similarities

- Bullying and Cyberbullying Among Peers

- Handling Cyberbullying in the 21st Century

- Cyberbullying and Its Impacts on Youths Today

- Cyberbullying Impact on Teenagers

- Cyberbullying Impact on Mental and Physical Health

- Cyberbullying: Definition, Forms, Groups of Risk

- Cyberbullying Through Social Media

- The Problem of Childrens' Cyberbullying

- Cyberbullying and Its Impact on Children

- Police ‘Shooter Bias’ Against African-Americans

- Racial Identity Development Model

- Social and Cultural Diversity and Racism

- Race and Ethnicity Relations in the United States

- White Privilege: History and Understanding

Changing Faces: Immigrants and Diversity in the Twenty-First Century

Subscribe to this week in foreign policy, audrey singer and as audrey singer james m. lindsay jml james m. lindsay.

June 1, 2003

Herman Melville exaggerated 160 years ago when he wrote, “You cannot spill a drop of American blood without spilling the blood of the world.” However, the results of the 2000 Census show that his words accurately describe the United States of today. Two decades of intensive immigration are rapidly remaking our racial and ethnic mix. The American mosaic—which has always been complex—is becoming even more intricate. If diversity is a blessing, America has it in abundance.

But is diversity a blessing? In many parts of the world the answer has been no. Ethnic, racial, and religious differences often produce violence—witness the disintegration of Yugoslavia, the genocide in Rwanda, the civil war in Sudan, and the “Troubles” in Northern Ireland. Against this background the United States has been a remarkable exception. This is not to say it is innocent of racism, bigotry, or unequal treatment—the slaughter of American Indians, slavery, Jim Crow segregation, and the continuing gap between whites and blacks on many socioeconomic indicators make clear otherwise. However, to a degree unparalleled anywhere else, America has knitted disparate peoples into one nation. The success of that effort is visible not just in America’s tremendous prosperity, but also in the patriotism that Americans, regardless of their skin color, ancestral homeland, or place of worship, feel for their country.

America has managed to build one nation out of many people for several reasons. Incorporating newcomers from diverse origins has been part of its experience from the earliest colonial days—and is ingrained in the American culture. The fact that divisions between Congregationalists and Methodists or between people of English and Irish ancestry do not animate our politics today attests not to homogeneity but to success—often hard earned—in bridging and tolerating differences. America’s embrace of “liberty and justice for all” has been the backdrop that has promoted unity. The commitment to the ideals enshrined in the Declaration of Independence gave those denied their rights a moral claim on the conscience of the majority—a claim redeemed most memorably by the civil rights movement. America’s two-party system has fostered unity by encouraging ethnic and religious groups to join forces rather than build sectarian parties that would perpetuate demographic divides. Furthermore, economic mobility has created bridges across ethnic, religious, and racial lines, thereby blurring their overlap with class divisions and diminishing their power to fuel conflict.

Read the full chapter (PDF-191kb)

More on the forthcoming book, Agenda for the Nation .

Brookings Metro Foreign Policy

William H. Frey

April 15, 2024

Gabriel R. Sanchez

March 4, 2024

Gabriel R. Sanchez, Carly Bennett

November 1, 2022

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Review article, impact culture: transforming how universities tackle twenty first century challenges.

- 1 Department of Rural Economies, Environment & Society, Thriving Natural Capital Challenge Centre, Scotland's Rural College (SRUC), Edinburgh, United Kingdom

- 2 Department of Environment and Geography, University of York, York, United Kingdom

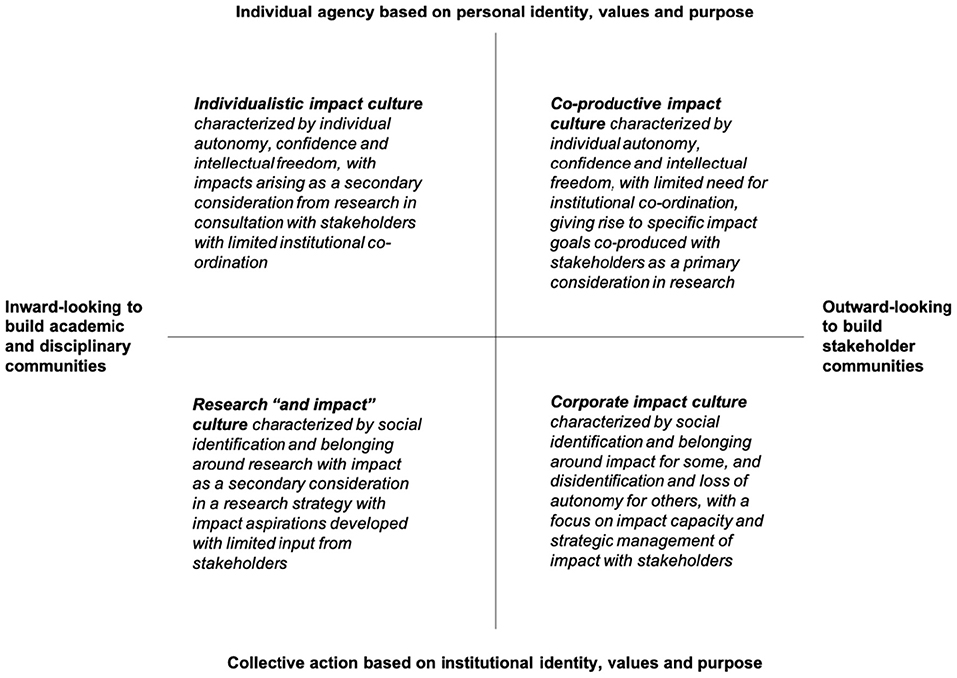

New ways of doing research are needed to tackle the deep interconnected nature of twenty first century challenges, like climate change, obesity, and entrenched social and economic inequalities. While the impact agenda has been shaping research culture, this has largely been driven by economic imperatives, leading to a range of negative unintended consequences. Alternative approaches are needed to engage researchers in the pursuit of global challenges, but little is known about the role of impact in research cultures, how more or less healthy “impact cultures” might be characterized, or the factors that shape these cultures. We therefore develop a definition, conceptual framework, and typology to explain how different types of impact culture develop and how these cultures may be transformed to empower researchers to co-produce research and action that can tackle societal challenges with relevant stakeholders and publics. A new way of thinking about impact culture is needed to support more societally relevant research. We propose that healthy impact cultures are: (i) based on rigorous, ethical, and action-oriented research; (ii) underpinned by the individual and shared purpose, identities, and values of researchers who create meaning together as they generate impact from their work; (iii) facilitate multiple impact sub-cultures to develop among complementary communities of researchers and stakeholders, which are porous and dynamic, enabling these communities to work together where their needs and interests intersect, as they build trust and connection and attend to the role of social norms and power; and (iv) enabled with sufficient capacity, including skills, resources, leadership, strategic, and learning capacity. Based on this framework we identify four types of culture: corporate impact culture; research “and impact” culture; individualistic impact culture; and co-productive impact culture. We conclude by arguing for a bottom-up transformation of research culture, moving away from the top-down strategies and plans of corporate impact cultures, toward change driven by researchers and stakeholders themselves in more co-productive and participatory impact cultures that can address twenty first century challenges.

Introduction

The world is facing challenges of unprecedented complexity and uncertainty that are bringing us to the edge of planetary boundaries where ecosystems may collapse, threating societal well-being and prosperity ( Rockström et al., 2009 ; Steffen et al., 2015 ; Nash et al., 2017 ). Working with these challenges, such as keeping global warming to within 1.5°C of pre-industrial levels (Article 2, Paris Agreement, 2015 ; IPCC, 2018 ) will require social, institutional, and technological transformations on a scale not previously seen. In this context, universities and research funders are increasingly positioning themselves to produce knowledge to address these issues.

This civic or societal mission is increasingly being codified and operationalized as impact 1 , driving the design of research policy and institutional structures and processes that seek to assess “objective” outcomes from research that can be quantified and rewarded. These assessments have led to a narrowing of the types of knowledge and impact that are valued and deemed legitimate ( de Lange et al., 2010 ; Smith et al., 2011 ; Parker and Van Teijlingen, 2012 ), leading to gaming behaviors, and an increase in stress and anxiety among researchers who are increasingly held accountable for the public goods arising from their use of public funding ( Watermeyer, 2019 ). Nevertheless, higher education and research institutions and funders are increasingly investing in impact ( Oancea, 2019 ). This has built significant capacity for impact across the sector, including specialist staff, training courses, internal impact grants, sabbaticals, awards, and the creation of boundary organizations ( Watermeyer, 2019 ). As a result, impact is now widely considered to be a key component of an institution's research culture ( Alene et al., 2006 ; Leeuwis et al., 2018 ; Moran et al., 2020 ).

However, limited attention has been paid to the growing importance of impact in research culture, including the values, beliefs, and norms of researchers and how they or their institutions find and articulate meaning and purpose in relation to research impact ( Moran et al., 2020 ; Rickards et al., 2020 ). We refer to this as “impact culture” and seek to understand how more or less healthy impact cultures might be characterized, and the factors that shape these cultures. To do this, we develop a definition, conceptual framework, and typology to explain how different types of impact culture develop and how these cultures may be transformed to empower researchers to co-produce research and action that can tackle twenty first century challenges with relevant stakeholders and publics.

Although there is limited research on impact culture, there is growing literature on research culture and culture change within Higher Education institutions. Some have argued that it is not possible to define a research culture at an institutional level, given the division of research between differently managed faculties with different research traditions ( Deem and Brehony, 2000 ; Becher and Trowler, 2001 ). Notwithstanding debate over the appropriate organizational scale at which research cultures develop and persist, the organizational culture literature typically defines research culture as the shared values, beliefs, and norms of an academic community that influence its behaviors and research outputs, and which then define the collective identity of that community and distinguish the strengths and foci of one institution from another (after Hildebrandt et al., 1991 ; Evans, 2007 ; Schneider et al., 2013 ; Shah et al., 2019 ). Alternatively, many psychologists and sociologists study culture by understanding how people find meaning as individuals (on the basis of their own perceptions), collectively (on the basis of social norms and shared perceptions), and through their relationship with objects ( Ashforth and Pratt, 2003 ; Mohr et al., 2020 ). Given the important role of values and meaning in these two understandings of research culture, impact may play a crucial role in shaping an institution's culture, providing both important values and meaning to justify and so underpin the production of research. Indeed, Chubb (2017) showed how researchers from more applied disciplines often felt personally validated and their work legitimized by the increasing recognition afforded to impact in UK and Australian universities.

However, this research also provided evidence that researchers from arts, humanities, and pure science disciplines, whose work was of less immediate or obvious public interest, were concerned that their work was expected to generate impact, and felt that their academic freedom was under threat from the increasing evaluation (and especially metricization) of impact ( Bulaitis, 2017 ; Chubb et al., 2017 ; Chubb and Reed, 2018 ). In a recent survey of over 4000 UK researchers by the Wellcome Trust ( Moran et al., 2020 ), three out of the top five words researchers used to describe their research culture were “competitive,” “pressured,” and “metrics.” Research has always been competitive, but now researchers are also competing to gain the trust of stakeholders who might be able to give them impact. To the “publish or perish” mantra, we have added “impact or implode” ( Reed, 2021 ), as universities, governments, and funders demand that researchers prove the value of their research to society. Indeed, 75% of those responding to the Wellcome Trust survey felt their creativity was being stifled by an “impact agenda” that was increasingly driving their research ( Moran et al., 2020 ). Similarly, Chubb and Reed (2018) , based on interviews with UK and Australian researchers, heard stories of researchers who had stopped asking the questions they thought were most important, because they were not impactful enough to be funded. It is clear that the impact agenda is generating its own negative impacts on research culture. Ironically, the impact agenda may be compromising the capacity of research institutions to address global challenges.

As such, it is important to understand how the impact agenda is shaping organizational cultures across the sector, and how these cultures may be re-shaped to avoid the conflicts of interest, demotivation of researchers, and other negative unintended consequences that are increasingly associated with impact. In one of the few attempts to characterize the development of impact culture, drawing primarily on Australian experience, Rickards et al. (2020) proposed three generations of impact culture. First-generation impact culture, they argued, focuses on making rigorous research more relevant and accessible, promoting messages from research to a wide audience, and encouraging end users to use it. As a result, first-generation approaches focus primarily on communication, equipping their most senior researchers to work with the mass media or social media to get their message across to as many people as possible. They also tend to focus on tackling visible impact challenges ( Fazey et al., 2018 ), such as the creation of new medical treatments or drugs.

Second-generation impact culture is more two-way, according to Rickards et al. (2020) . It shifts the focus to working with partners to ensure research is both relevant and legitimate, and quantifies the value generated for these partners. For example, the “triple helix” model of the university ( Leydesdorff, 2012 ) has been extended to a quintuple helix model in which the activities of universities are conceptualized as intrinsically intertwined with those of business, government, civic society, and the environment ( Carayannis et al., 2012 ). Second-generation approaches focus on improving “research impact literacy” ( Bayley and Phipps, 2019 ) across the institution and equipping researchers at all career stages with the skills they need to understand and meet needs among stakeholders and publics. They are as likely to focus on more conceptual impact challenges as they are to tackle visible challenges ( Fazey et al., 2018 ), for example shifting behaviors or other causes of the symptoms for which others are creating drugs.

Third-generation impact culture seeks to examine, and where necessary question, the assumptions driving the systems that both generate and apply knowledge, asking who generates what knowledge for whom, for what purpose, and why ( Rickards et al., 2020 ). Third-generation impact culture does not assume that universities are even necessary to generate the knowledge or impact that society needs. As a result, third-generation cultures are open to systemic innovations in the way researchers work, creating safe spaces in which researchers and partners can try out new ideas without fear of failure, and providing the support to refine, adapt, and mainstream the best ideas, even if these disrupt the current status quo. They are more likely to focus on systemic and transformative change, moving beyond technological and behavioral change to transform systems and structures ( Haberl et al., 2011 ; Kanger and Schot, 2019 ; Victor et al., 2019 ) and underlying beliefs, assumptions, values, and mindsets ( O'Brien and Sygna, 2013 ), including changing the assumptions held by researchers about how change itself happens ( Hodgson, 2013 , 2019 ; Connor and Marshall, 2015 ; O'Brien, 2016 ). As a result, these cultures are more likely to tackle existential challenges ( Fazey et al., 2018 ), for example, tackling the cultural drivers of unhealthy behavior or trying to transform the medical model that uses drugs to treat symptoms because it is cheaper in the short-term than funding social prescribing programs or “lifestyle medicine” that attempts to tackle the causes of poor health.

The three-generation model explains how impact culture may develop over time or to different degrees, and characterizes some of the activities that are likely to be found in different types of impact culture. However, it has less to say about the drivers of impact culture (including the role of researchers, stakeholders, and institutional co-ordination in constructing impact culture) or the ways in which universities may need to transform their operating models in response to these drivers, to facilitate more healthy impact cultures that are more likely to tackle twenty first century challenges. It is also not clear if impact cultures necessarily evolve in “stages” from first to second and then third generations, or if culture change processes can “leapfrog” the earlier stages. Impact culture may also not be homogeneous across an institution, and it may be possible for all three generations to co-exist within the same institution as different groups develop their own cultures. For this reason, we sought to develop a conceptual framework that could be used to both evaluate and shape impact culture proactively in response to change without further disempowering researchers through top-down, technocratic approaches, whilst providing an alternative explanation for how impact cultures may evolve and co-exist in research institutions. The next section explains how this was done.

The insights in this paper were based on a narrative literature review and further developed over the course of a year of dialogue and workshops with professional services staff working on impact, senior managers in universities, and researchers from a wide range of disciplines (e.g., biomedical, physical and natural sciences, social sciences, arts and humanities). Narrative literature reviews are more appropriate than systematic reviews where it is not possible to identify specific outcome measures, and the aim is to provide an expert-based synthesis of a broad range of literature ( Baumeister and Leary, 1997 ; Greenhalgh et al., 2018 ). We integrated literature from a wide range of disciplines and fields, including research impact, cultural sociology, research ethics, public engagement, participation, deliberative democracy, individual values and self-identity, social and cultural values, the psychology of meaning making (in particular the meaning of work), motivation, social learning, social capital, trust, social norms, power, responsible research and innovation, capacity building, leadership, and organizational development.

The literature review led to the development of an initial conceptual framework, which was refined iteratively through 11 training workshops with different universities in the UK, Australia, and Sweden. These workshops were designed to create a safe space for participants to critically evaluate and discuss challenges and successes in their own culture and learn from each other. The proposed framework helped them consider how different elements of impact culture could be built or enhanced in their own contexts, but also allowed for new insights to emerge that helped to further develop the framework. Between the workshops, bi-lateral discussions also took place between the co-authors, and between the lead author with trainees and others working on impact culture internationally, further shaping the work.

As such, the insights in this paper came from a reflexive interplay between different kinds of knowledge, from many different people with different experiences and backgrounds. This included iterative development from working initially to articulate the authors' implicit knowledge in ways combined with epistemic knowledge (written accounts from other studies), which were then explicitly articulated, tested, and refined through social learning and different forms of interaction, to lead to a new set of insights expressed in this paper. Much of the learning that led to our insights thus emerged through the interplay between the dynamics articulating, connecting, embodying, and empathizing knowledge, as described in seminal work on learning ( Nonaka et al., 2000 ; Wenger-Trayner and Wenger-Trayner, 2020 ). Thus, while our insights were not derived from traditional academic empirical approaches, they did come from creative processes conducive to advancing conceptual understandings of impact culture and what might be needed to facilitate change to improve it. Further, the insights were explicitly meant to be a combination of what we know now (usually considered to be experience of, or evidence from, the past or the present) with a normative and desired sense of what should be. Such approaches are consistent with calls for the development and application of future methods that enable the enaction of ideas that support change ( Fazey et al., 2018 , 2020 ). The outcome has been a refined framework and set of insights that can be applied, tested, and further refined through and across different disciplinary and institutional contexts. This outcome includes a definition, framework, and typology that are rooted in existing literature and shaped by the experience of many who currently work in diverse domains of research and knowledge creation.

Impact Culture: a Conceptual Framework

The conceptual framework that emerged from the iterative process described in the previous section describes a number of connected domains within which impact cultures may develop and be lived out in research institutions. The framework is bottom-up, starting by understanding how impact interacts with the purpose of individuals and groups as they find meaning in their work, and how this in turn influences their identity and motivation as researchers. As individuals with a shared purpose begin to form groups and create community, different sub-cultures, rooted in very different values, beliefs, and norms, are likely to emerge across an institution. Although these groups may sometimes work at cross purposes, the flourishing of multiple impact cultures underpinned by different purposes and values is an important expression of academic freedom and agency. Such a bottom-up approach may co-exist and interact productively with more top-down, collective approaches to creating impact cultures around institutional visions, missions, and values. However, we argue that participatory change from the bottom up is more likely to achieve meaningful and lasting change in the practices and behaviors of researchers, and so deliver impacts that are consistent with their values, beliefs, and norms, maintaining the motivation of researchers as they address twenty first century challenges.

Rather than expecting all researchers to engage with impact, there is room for pure, basic, and non-applied research, which has no obvious impact, alongside more applied, action-oriented research designed explicitly to tackle societal challenges, with researchers drawn to impact on their own terms, as opportunities intersect with their interests and values. While extrinsic incentives, in the form of research funding and impact assessments, have increasingly driven engagement with impact around the world ( Reed et al., 2020 ), it has also driven negative unintended consequences, as outlined in the Background section. An approach that seeks to build more on the diverse intrinsic motivations of researchers may be slower to affect behavior change. However, the changes that occur are likely to be deeper, longer lasting, and less likely to lead to the conflicts of interest, mistrust, and demotivation often associated with more extrinsic approaches.

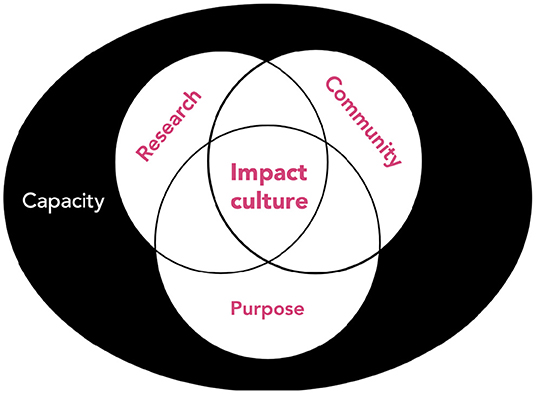

Specifically, the framework includes four interlinked domains: purpose, research, communities, and capacity. Here, we provide a normative description of each component, as we would expect it to contribute toward a “healthy” impact culture that generates impact from research with the fewest possible negative unintended consequences for stakeholders and publics, and for researchers and their institutions/funders. A healthy impact culture:

1. Emerges from clear individual and shared purpose;

2. Generates impacts that are based on rigorous, ethical, and action-oriented research;

3. Forms and is lived out by groups of people as they interact with both academic and non-academic communities; and

4. Builds the capacity needed to facilitate the research, community, and priorities that underpin impact.

Based on this conceptual framework, we define impact culture as communities of people with complementary purpose who have the capacity to use their research to benefit society .

While our definition and framework are based on insights from the literature, the interpretation, framing, and integration of this evidence was shaped through an iterative process of individual interviews and discussion in workshops over the course of a year, as described in the previous section. This led to the articulation of the four domains under which our review of the literature is arranged in the rest of this section.

Clear purpose is the foundation of a healthy impact culture because culture is in large part about meaning making ( Ashforth and Pratt, 2003 ; Mohr et al., 2020 ). Meaning is a key component of most academic definitions of purpose, which suggest that purpose is found by finding meaning in past, present, and future life experiences ( Ryff, 1989 ), leading to an intention or goals to achieve something that is meaningful and of consequence ( Damon et al., 2003 ; Kosine et al., 2008 ). Alternatively, McKnight and Kashdan (2009) suggest that purpose is more of a guiding principle or “self-organizing life aim” that organizes goals and behaviors to generate a sense of meaning. This includes the meaning researchers derive from their work, as it is influenced by values, self-identity, and significant others, how this influences motivation, and how the impact agenda has created goal conflicts for many researchers that have further influenced the meaning, identity, and motivation they derive from work.

Meaning of Work

There is a rich literature on the meaning of work. From the individual, psychological perspective, this ranges from research on beliefs, values, and attitudes toward work (e.g., Nord et al., 1990 ; Roberson, 1990 ; Ros et al., 1999 ) to the subjective experience and significance of work (e.g., Wrzesniewski et al., 2003 ; de Boeck et al., 2019 ). From a more sociological perspective, meaning is constructed through social interaction and reflects social norms and shared value systems that ascribe meaning to certain types of work (e.g., Mead, 1934 ; Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck, 1961 ; Geertz, 1973 ). Ultimately, meaning is sense-making, in terms of how a person makes sense of (or understands) something, or perceives its significance, in a given social or some other context ( Ashforth and Pratt, 2003 ; Wrzesniewski et al., 2003 ).

The meaning that any individual ascribes to work is strongly influenced by their values and self-identity. For example, the Life Framework of Values ( O'Connor and Kenter, 2019 ) can be adapted to show how researchers live with, from, in , and as part of their work. This gives rise to the consideration of instrumental values (the value of what researchers can get from work), relational values (how researchers value their relationships in and with work) and intrinsic values (the value of work without reference to any benefits for the researcher). More simply put, Roberson (1990) classifies value orientations as primarily intrinsic vs. extrinsic, and others have applied Schwartz's (2012) “compass” of 10 basic values to consider how a person's values influence the meaning they derive from work.

In addition to the influence of individual values, meaning making, and hence the development of any work culture, is influenced by co-workers, leaders, communities, and family relationships ( Rosso et al., 2010 ). These relationships may provide cues about how to interpret work experiences and derive meaning through an inter-personal sense-making process in which alternative meanings based on different value orientations may be considered ( Salancik and Pfeffer, 1978 ; Wrzesniewski et al., 2003 ). Social identity theory suggests an alternative mechanism, based on membership and identification with “in-groups” at work that help people establish a clearer sense of self-identity (often in contrast to “out-groups”) and purpose as they contribute to others in their work community ( Kahn, 1990 ; Grant, 2007 ; Grant et al., 2008 ). Having a sense of belonging to a group can help people find meaning as they experience a common identity, shared fate, or connection with others ( Homans, 1958 ; White, 1959 ).

Motivation for Work

Meta-analyses have shown a strong relationship between the perceived meaningfulness of work and intrinsic motivation to do work that a person feels matters ( Hackman and Oldham, 1976 , 1980 ; Fried and Ferris, 1987 ). But what “matters” is deeply personal, and is strongly linked to a person's identity or “self-concept,” which Rosenberg (1979 , p. 7) defines as “the totality of a [person's] thoughts and feelings that have reference to himself as an object”, which will change over time in response to different experiences and contexts ( Ashforth and Mael, 1989 ). There is evidence that intrinsic motivation for work is strongly influenced by the perceived alignment between work tasks and a person's self-identity ( Pinder, 1984 ; Deci and Ryan, 1985 ), especially when the person experiences autonomy and competence as they perform the tasks ( Deci and Ryan, 2000 ), and perceives that they are in control of their own decisions ( Rosso et al., 2010 ). The authenticity of aligning work with perceptions of the “true” self is a key mechanism through which people derive meaning from work ( Gecas, 1991 ), enabling them to maintain and affirm their identity and values while working ( Shamir, 1991 ).

This marries with the perceived loss of autonomy and “academic freedom” described by the largely demotivated respondents to the Wellcome Trust survey ( Moran et al., 2020 ). This is important in the academic sphere because researchers often self-identify strongly with their work, gaining significant levels of self-esteem from their psychological identification with their jobs. As a result, many academics see their work as a “calling” in which they work for fulfillment rather than financial award or advancement, as opposed to having a job (in which meaning is derived from material benefits that can be enjoyed away from work) or career (in which meaning is derived from advancing through an occupational structure, and attaining increased status as well as pay) (see Baumeister, 1991 for more on this tripartite model of work orientation). The perception of work as a calling is typically associated with beliefs that “ work contributes to the greater good and makes the world a better place ” ( Rosso et al., 2010 , p98), for example, the advancement of the discipline or non-academic impact.

The idea of work as a “calling” has theological roots ( Luther, 1520 ; Calvin, 1574 ), and although most workers are reluctant to discuss it openly, empirical research has shown that many think of their work in spiritual terms ( Davidson and Caddell, 1994 ; Grant et al., 2004 ; Sullivan, 2006 ). Here, we define spiritual as a personal search for meaning or purpose ( Tanyi, 2002 ) typically associated with a connection to something other, larger, more significant, and lasting than the self ( Dyson et al., 1997 ), including a higher power, guiding force or energy, or belief system ( Hill and Pargament, 2003 ). Maslow (1971) described this as “transcendence,” and Rosso et al. (2010) referred to it as “interconnection,” where individuals supersede their ego to connect with an entity greater than themselves or beyond the material world. In this sense, engaging in research and impact both have the potential to contribute to a “ greater good ” (as Rosso et al., 2010 put it) of lasting significance. If cultures are built through the creation of meaning, it seems important to understand how universities can give researchers the autonomy, capacity, and opportunities to make contributions that will provide this deeper sense of purpose in their work. As such, the transformation of universities to become purpose-driven, rather than being driven by the impact agenda, is an opportunity for universities to enable researchers to find their own purpose as much as it is an opportunity to connect with the purpose of the university or the stakeholders it seeks to serve.

This transition, however, has created a goal conflict between research and impact for many researchers. As the Wellcome Trust survey showed ( Moran et al., 2020 ), many universities' attempts to transition to a more social mission has compromised the perceived autonomy of researchers, with 74% saying that they thought “ creativity was being stifled due to research being driven by an impact agenda .”

Goal Conflicts

A clear sense of purpose leads to the creation of meaningful goals and behaviors that re-enforce and support that purpose ( Damon et al., 2003 ; Kosine et al., 2008 ; McKnight and Kashdan, 2009 ). Therefore, pressures that force researchers to prioritize their time in ways that are not in line with their purpose can lead to significant levels of psychological dissonance and demotivation, and may in some cases compromise well-being ( Haradkiewicz and Elliot, 1998 ; Bronk et al., 2009 ; Burrow et al., 2010 ). As such, resolving goal conflicts, such as those identified by the Wellcome Trust survey ( Moran et al., 2020 ) between research and impact is a crucial component of enabling researchers to create a healthy impact culture.

Goal hierarchy theory has been widely applied to goal conflicts ( Unsworth et al., 2011 ), and so is pertinent to the duel challenge of producing both research and impact, faced by researchers who are under increasing pressure to both publish and generate impact from their research. The theory helps explain how purpose emerges from an individual's values and self-identity and is expressed through priorities, ultimately influencing which tasks are completed, and which are postponed or discontinued.

At the top of the goal hierarchy are values (referred to in the theory as “self-goals”). Although often implicit and unspoken, a researcher's values ultimately determine the decisions they make as their values create a domino effect through each of the other goals in the hierarchy. These values inform and shape the researcher's identity (or “principle goals” in the theory). Their identity then informs and shapes their purpose and priorities (“project goals” in the theory) because they want their purpose and priorities to be consistent with their self-identity. Their purpose and priorities then dictate the tasks that are prioritized at the bottom of the goal hierarchy. Psychological dissonance arises when a person has to prioritize tasks that are not aligned with their identity and values, leading to demotivation and disengagement from work. As such, someone who has a strong identity as a researcher, informed by values such as the intrinsic value of knowledge and curiosity, is likely to be demotivated when confronted with impact-related tasks. Similarly, research tasks may demotivate someone who sees themselves primarily as an impactful knowledge broker, based on values that drive empathic connection with those facing real-world challenges.

Goal hierarchy theory suggests two approaches to resolving goal conflicts between research and impact. In the first approach, tasks are ranked on the basis of their alignment with the identity and values of the researcher, and this is used as a justification to drop tasks that align poorly, where this is possible. In reality this is often not practical, so task integration seeks to identify tasks that are aligned with core identities and values, that will also enable the achievement of non-aligned tasks. For example, someone whose primary identity is as a curiosity-driven researcher might co-author more applied papers with stakeholders or draw on impact evaluation data to enhance their applied research, enhancing impact while pursuing research tasks. Alternatively, someone whose primary identity is linked to their impact might extend or complete a stalled paper with some new research that makes the work more relevant to stakeholder needs, or apply for research funding with stakeholders who will benefit if the project is funded.

If culture is created through meaning-making, then it is crucial to understand how engaging with impact can contribute toward or conflict with the identity, values, and purpose of researchers, and their intrinsic motivation. A lack of attention to these deeper issues may explain the demotivation associated with impact in the Wellcome Trust survey ( Moran et al., 2020 ) and negative attitudes held toward the Research Excellence Framework, which assesses the impact of UK research ( Weinstein et al., 2021 ). Indeed, in interviews with researchers in the UK and Australia, where the institutional impact agenda is most advanced ( Chubb and Reed, 2017 , 2018 ; Chubb et al., 2017 ), researchers from less applied disciplines (primarily in the sciences, arts, and humanities) reported feeling judged by their colleagues for doing work that was perceived to be self-indulgent and of little public interest. A university that prioritizes impact may only provide purpose for more applied researchers, whose work is already well-aligned with the impact agenda. To create a more inclusive impact culture, in which all researchers can feel valued and find deeper meaning in their work, it is important to create opportunities for researchers to engage with impact authentically, on their own terms, in ways that are consistent with their unique purpose, identity, and values, and hence build their intrinsic motivation, rather than building yet more extrinsic incentives to push colleagues toward impact.

How we produce research is an intrinsic part of any impact culture that seeks to meet needs and be evidence-based. This includes the ethics and disciplinary-specific notions of rigor that underpin our research and the extent to which research focuses on understanding problems vs. solutions. Although co-production could have fitted under the community theme (in the next section), it is covered here on the basis of literature arguing for Mode 2 research which includes co-production ( Nowotny et al., 2003 ).

Rigorous and Ethical Research

Healthy impact cultures underpin their impacts with rigorous and ethical research. Without relevant safeguards, it is possible for research to have seriously negative impacts, for example as was seen from now discredited research on the link between the MMR vaccine and autism ( Wakefield, 1999 ) or the many highly influential studies from psychology that have failed to be replicated, whose findings are now thought to have arisen from the practice of “data dredging” or “p-hacking,” where researchers search large datasets for statistically significant relationships and then retrofit a hypothesis that could explain the finding ( Maxwell et al., 2015 ). The open science movement is now tackling this by creating new norms in many disciplines to pre-publish research protocols and make data available for others to analyze ( Friesike et al., 2015 ; Vicente-Sáez and Martínez-Fuentes, 2018 ).

However, it is important to recognize that perceptions of rigor and ethics may vary between researchers and disciplines. Ethical issues may differ between research groups, and even between members of the same group, including many that researchers may be unaware of. For example, female, ethnic minority, vulnerable, or hard-to-reach groups may inadvertently be excluded from social science due to the timing, location, or design of interviews or focus groups ( Morgan and Morgan, 1993 ; Flanagan and Hancock, 2010 ). There is also growing pressure on researchers to make “policy recommendations” from single studies, whether in response to journal editors and reviewers who want the research to be more widely read (and cited) or funders who want to see impacts from their investment. However, while there is growing recognition that such recommendations should only be made on the basis of evidence synthesis, there are limited incentives from funders or universities to prioritize synthesis work over conducting new original research. More worrying still is evidence that researchers perceive that certain gendered personality traits are better suited to achieving impact, biasing researchers and evaluators toward pursuing ‘hard' impacts that can be counted, instead of ‘softer', less quantifiable impacts ( Chubb and Derrick, 2020 ). In response to some of these challenges, there is now rich literature on “responsible research and innovation” ( Owen et al., 2012 ; Von Schomberg, 2013 ). This community advocates for responsible research that is inclusive (for example, of genders, publics, disadvantaged and hard-to-reach groups), open (pre-publishing research protocols, pre-print papers, and data), and responsive (to the needs of those who might benefit from the research, providing them with opportunities to engage throughout the research cycle).

Action-Oriented Research

The second reason we need to consider the research that underpins our impact culture is the tendency to focus on understanding problems rather than researching solutions. We need to shift our focus from amassing more and more knowledge about the problems the world is facing, to devising and testing solutions that might tackle the underlying drivers of the problems we have studied for so long. Often described as “mode 1” research ( Nowotny et al., 2003 ), the majority of the peer-reviewed literature to date has sought to describe the world as it is, with all its problems, by proposing and testing theories that can be generalized to provide universal knowledge that can be applied across many different contexts.

“Mode 2” research pays more attention to the context in which knowledge is generated and applied, and focuses more on the applicability of knowledge in any given context, than its generalizability between contexts ( Nowotny et al., 2003 ; Caniglia et al., 2021 ). As researchers connect with the contexts in which they do research, they become able to legitimately connect with the people and contested issues in that context, and it becomes increasingly difficult to act as a detached observer. For example, researchers might seek solutions to visible challenges, such as increasing research funding to early career researchers and groups that are more likely to experience discrimination (such as women, researchers from ethnic minorities, and those with disabilities or long-term health conditions). However, it is possible to go beyond this to find solutions to the deeper conceptual and existential issues that are driving the problems we can see at the surface. We need to tackle problems within the underlying systems and structures that perpetuate inequality and discrimination. Some of these solutions need to be conceptual, for example how to transform institutional structures, financial models, and modes of governance in our universities and funding bodies. Or we may focus on the values, beliefs, and norms of those who make and follow the rules that govern our institutions. Other solutions need to tackle existential challenges, for example reconceptualizing what universities are for, and who they are meant to serve.

An interesting example of action research with local communities is Staffordshire University's Creative Communities Unit (CCU), a dedicated public engagement unit which ran from 2002 to 2018 ( Gratton, 2020 ). Their “Get Talking” approach to participatory action research emphasized the use of creative engagement techniques to connect with vulnerable and hard-to-reach groups via “community researchers” who were trained and often paid to work as partners on projects. Community researchers could also enroll on a course to get credit for their work, enabling people who had never engaged in Higher Education before (and probably would never have considered doing so) to gain a qualification. Over time, the Unit built up a large team of community researchers who could work on new projects as they came in. The work was so successful that the CCU started attracting funding from local government and charities to deliver outcomes for the local communities they were serving. Whilst the CCU no longer exists, the Get Talking approach has been adapted for a diverse range of projects. In addition to the contributions of community researchers to the university, there were positive impacts for community members who gained new friends through taking part in events. They established a network that became a lifeline for many when the country then went into lockdown in response to the Coronavirus outbreak.

A similar approach has been taken by a number of projects that have applied to their funders for flexible funding in which there is a pot of money dedicated for use in community projects. Community groups propose projects, and a panel of community members help decide who gets the funding in collaboration with the research team. Impact monitoring might be built into the projects by the researchers, but otherwise there is no formal reporting requirement, enabling community groups to share what they have used the money to do in more creative ways than writing reports. The creativity of the projects that emerge from this sort of approach can be unexpected. For example, the Managing Telecoupled Landscapes project ( Zaehringer et al., 2019 ) built in flexible funding for local project partners to generate impact based on evidence arising from the research. For each of the three countries they worked in, Laos, Madagascar, and Myanmar, they had a budget of 50,000 CHF to fund two “implementation actions” per country. In Madagascar they organized a workshop with stakeholders from the vanilla sector and discussed how the revenues generated through vanilla trade could be steered toward more sustainable regional development. As part of this, they developed a film that integrated the voices of different vanilla stakeholders. At the same time, they implemented an agricultural diversification scheme, training young farmers from different villages to facilitate farmer-to-farmer knowledge exchange and innovation. Building on this, they then were able to attract funding from a private donor, through which other individuals and groups of farmers can now apply for funding for forest-friendly development projects.

More radical than this however are the Ownership, Control, Access, and Possession (OCAP) principles which are used by a range of indigenous populations around the world (including First Nations communities in North America, Métis, and Inuit communities) to ensure research is not exploitative ( Schnarch, 2004 ). In some of these communities, researchers who want to work with local communities have to agree to the OCAP principles before they can work through the organizations representing the community. This means that indigenous communities control data collection processes themselves, and they own, protect, and control how their information is used. They, not the researchers, have the final say in any decision about how and by whom the research data are collected, used, or shared. At the end of your 3 year project, if the community you worked with decide they do not want you to publish your research, they have the power to block publication. This option is important given the extractive nature of many research practices this community had previously been exposed to. In reality, this is rare however, unless the necessary steps of relationship building and trust had not been established, and the research did not respond to their stated needs. While co-production can be described as a way of doing research and delivering impact, it is clearly also about trust and relationship building, and so in the next section, ways of building community with stakeholders is explored in greater depth.

There are three elements of community that may significantly influence impact culture: trust, connection, and the role of social norms and power. Taken together, these represent the “social capital” that an individual, team, or institution has with those they need to work with to generate impact ( Bachmann, 2001 ; Rust et al., 2020 ).

Cairney and Wellstead (2020) define trust simply as, “a belief in the reliability of other people, organizations, or processes” as their actions affect the person who is trusting (after Gambetta, 1988 ). The perceived trustworthiness of researchers depends on their integrity (or honesty), credibility (the feasibility and evidential basis of their claims), and competence (or ability) ( Cairney and Wellstead, 2020 ). The role of cognitive biases should not be underestimated in the formation of these perceptions, as people use heuristic shortcuts, including both evidence-based and potentially prejudicial assessments, to evaluate the trustworthiness of others they do not know, based on prior experience ( Kahneman and Tversky, 2013 ). Trust is necessary for research impact because it enables people to co-operate without the need for contracts, non-disclosure agreements and, other cumbersome arrangements, reducing complexity and facilitating efficient collaboration. Trust can exist between individuals and between institutions, and to understand trust, it is necessary to look both ways, from the perspective of each party to the relationship ( Luhmann, 1979 ; Zucker, 1986 ).

Public trust in research was put to the test during the recent COVID crisis. Although it can be difficult to disentangle public trust in research vs. the governments who are implementing scientific advice, it is clear that public trust in the scientific basis for COVID precautions differs significantly around the world. For example, in Saudi Arabia there is evidence of public trust in both government pandemic policy and its scientific basis ( Almutairi et al., 2020 ), while trust has been low in the Democratic Republic of Congo ( Whembolua and Tshiswaka, 2020 ). Kreps and Kriner (2020) found evidence that US researchers who downplayed uncertainty gained public and political support for their recommendations in the short term, but later contradictory studies or reversals in projections reduced trust in research over the longer term. Agley (2020) showed that US public trust in science about COVID was influenced by factors such as religious and political orientation.

This is, of course, the latest in a long line of issues that have tested public trust in research. For example, in a European Commission (1997) survey, 26% of citizens identified environmental organizations when asked whom they trusted most to tell the truth about genetically modified crops, compared to just 6% who named universities (and 1% and 4% who named industry and national public authorities, respectively). The earthquake and tsunami that triggered Japan's 2011 nuclear accident shook Japanese public trust in science, as researchers were viewed as endorsing defensive government narratives on the accident ( Arimoto and Sato, 2012 ). In the UK, controversies surrounding bovine spongiform encephalopathy during the 1990s prompted public criticism of the role of scientific advice in policy-making, leading to the formulation of rules for science-based policy-making by the government ( UK Government Office for Science, 2010 , 2011 ). Other guides have been produced by governments around the world in an attempt to strengthen public trust in research, and the role of research evidence in policy-making (e.g., Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften, 2008 in Germany, Commission of the European Communities, 2002 , and Government of Japan, 2011 ).

To retain and build public trust in research(ers), Wilson et al. (2017) suggested 10 strategies: be transparent; develop protocols and procedures; build credibility; be proactive; put the public first; collaborate with stakeholders; be consistent; educate stakeholders and the public; build your reputation; and keep your promises. Similarly, McAllister (1995) argues that interpersonal trust depends on perceiving someone as competent, reciprocal, fair, reliable, responsible, and dependable. It is possible to trust a researcher or institution on one issue for which they are deemed competent but not on other issues, where they do not have the same track record. However, by following guidelines such as those proposed by Wilson et al. (2017) , it may be possible for researchers and their institutions to systematically build trust with publics and key stakeholders over time.

Trust is an important precondition for many impacts because we know that people are more likely to act on evidence they receive via trusted individuals and networks ( Carolan, 2006 ; de Vries et al., 2015 ; Taylor and Van Grieken, 2015 ). This effect is more pronounced when there is risk or uncertainty ( O'Brien, 2001 ), complexity ( Luhmann, 1979 ), or credibility issues ( Ingram et al., 2016 ) associated with the evidence or the actions being proposed. Knowledge is exchanged more frequently and freely among networks of people who trust each other, while the presence of just one person in the network who is perceived to be untrustworthy can instantly shut down group communication ( Lyon, 2000 ; Levin and Cross, 2004 ; Stobard, 2004 ). Indeed, de Vente et al. (2016) showed that having senior decision-makers in the room (in this case policy-makers) was more likely to deliver decisions that were implemented on the ground, but discussion, learning, and trust building were much more significant when these people were not in the room.

The temporal dynamics of trust are worth noting. Trust typically forms slowly over many small steps, and so the first step toward building trust with someone is to engage with them, and give each other low-risk opportunities to give and take, and see what happens ( Rust et al., 2020 ). It is this reciprocity that builds trust over time. Once a trusting relationship has been established, we continue to perform acts of trust and trustworthiness in the day-to-day give and take of our relationship ( de Vries et al., 2015 ). When trust is broken, it often happens in an instant, and can take far longer to rebuild than it took to build in the first place ( Lewicki et al., 1998 ; Lewicki and Tomlinson, 2003 ).

Despite the clear link between reciprocity and trust building, the majority of researchers invest little time in reciprocal relationships beyond their disciplinary networks. This remains one of the most powerful ways researchers can build trusting, impactful relationships beyond the academy. Using stakeholder analysis ( Reed et al., 2009 ; Kendall and Reed, in preparation), it is possible to identify individuals, groups, and organizations that might benefit from engaging with research, and starting with these connections, small beneficial acts can initiate the process of reciprocity that builds trust over time. Many supposedly “serendipitous” impacts arise from this process of “being in the right place at the right time” as researchers build their non-academic networks, and become more visible and accessible to those looking for help. Such networking activities can build three types of connection, which can each play a different role in promoting impact ( Pretty and Ward, 2001 ; Pretty, 2003 ; Rust et al., 2020 ):

1. Researchers build “bonding” connections when they invest in relationships with people who are similar to them, typically sharing similar interests and attitudes. While this might typically refer to institutional and disciplinary networks, it is possible to create bonding capital within diverse communities of interest;

2. Researchers can take on the role of “bridging” connections if they are able to build trusting relationships with key individuals in very different networks who would not normally interact with each other, e.g., Neumann (2021) and Reed et al. (2020) showed how researchers played particularly important bridging roles between members of the research, business, charity, and policy communities in UK and German peatland governance bodies.