Covering a story? Visit our page for journalists or call (773) 702-8360.

UChicago Class Visits

Top stories.

- Book of Gary Becker’s unpublished work shows his evolution as an economist

Winners of the 2024 UChicago Science as Art competition announced

Ways to celebrate earth month 2024 at the university of chicago, the origin of life on earth, explained.

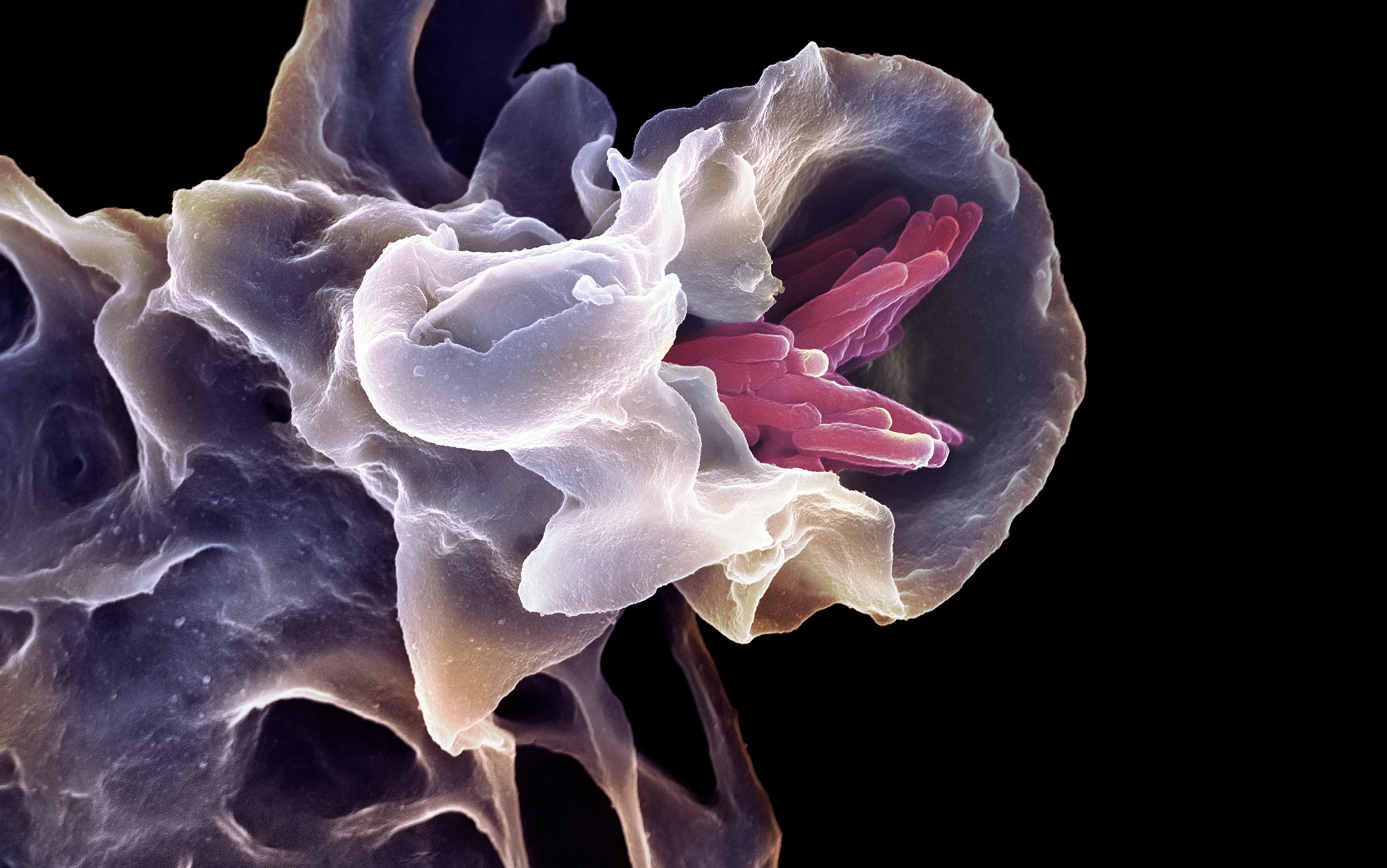

The origin of life on Earth stands as one of the great mysteries of science. Various answers have been proposed, all of which remain unverified. To find out if we are alone in the galaxy, we will need to better understand what geochemical conditions nurtured the first life forms. What water, chemistry and temperature cycles fostered the chemical reactions that allowed life to emerge on our planet? Because life arose in the largely unknown surface conditions of Earth’s early history, answering these and other questions remains a challenge.

Several seminal experiments in this topic have been conducted at the University of Chicago, including the Miller-Urey experiment that suggested how the building blocks of life could form in a primordial soup.

Jump to a section:

- When did life on Earth begin?

Where did life on Earth begin?

What are the ingredients of life on earth, what are the major scientific theories for how life emerged, what is chirality and why is it biologically important, what research are uchicago scientists currently conducting on the origins of life, when did life on earth begin .

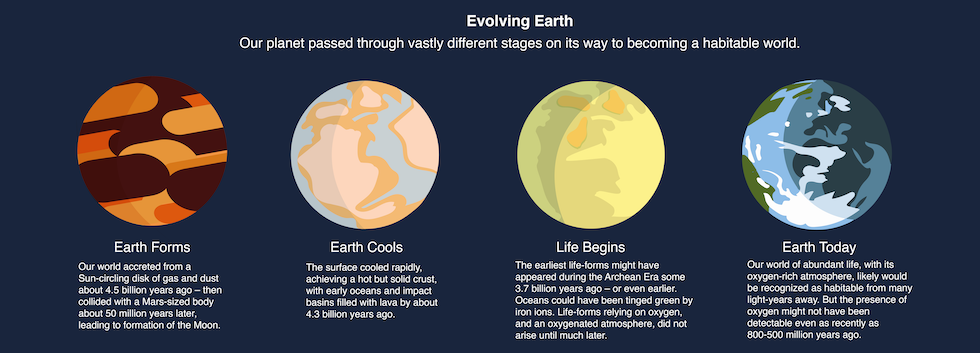

Earth is about 4.5 billion years old. Scientists think that by 4.3 billion years ago, Earth may have developed conditions suitable to support life. The oldest known fossils, however, are only 3.7 billion years old. During that 600 million-year window, life may have emerged repeatedly, only to be snuffed out by catastrophic collisions with asteroids and comets.

The details of those early events are not well preserved in Earth’s oldest rocks. Some hints come from the oldest zircons, highly durable minerals that formed in magma. Scientists have found traces of a form of carbon—an important element in living organisms— in one such 4.1 billion-year-old zircon . However, it does not provide enough evidence to prove life’s existence at that early date.

Two possibilities are in volcanically active hydrothermal environments on land and at sea.

Some microorganisms thrive in the scalding, highly acidic hot springs environments like those found today in Iceland, Norway and Yellowstone National Park. The same goes for deep-sea hydrothermal vents. These chimney-like vents form where seawater comes into contact with magma on the ocean floor, resulting in streams of superheated plumes. The microorganisms that live near such plumes have led some scientists to suggest them as the birthplaces of Earth’s first life forms.

Organic molecules may also have formed in certain types of clay minerals that could have offered favorable conditions for protection and preservation. This could have happened on Earth during its early history, or on comets and asteroids that later brought them to Earth in collisions. This would suggest that the same process could have seeded life on planets elsewhere in the universe.

The recipe consists of a steady energy source, organic compounds and water.

Sunlight provides the energy source at the surface, which drives photosynthesis. On the ocean floor, geothermal energy supplies the chemical nutrients that organisms need to live.

Also crucial are the elements important to life . For us, these are carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, and phosphorus. But there are several scientific mysteries about how these elements wound up together on Earth. For example, scientists would not expect a planet that formed so close to the sun to naturally incorporate carbon and nitrogen. These elements become solid only under very cold temperatures, such as exist in the outer solar system, not nearer to the sun where Earth is. Also, carbon, like gold, is rare at the Earth’s surface. That’s because carbon chemically bonds more often with iron than rock. Gold also bonds more often with metal, so most of it ends up in the Earth’s core. So, how did the small amounts found at the surface get there? Could a similar process also have unfolded on other planets?

The last ingredient is water. Water now covers about 70% of Earth’s surface, but how much sat on the surface 4 billion years ago? Like carbon and nitrogen, water is much more likely to become a part of solid objects that formed at a greater distance from the sun. To explain its presence on Earth, one theory proposes that a class of meteorites called carbonaceous chondrites formed far enough from the sun to have served as a water-delivery system.

There are several theories for how life came to be on Earth. These include:

Life emerged from a primordial soup

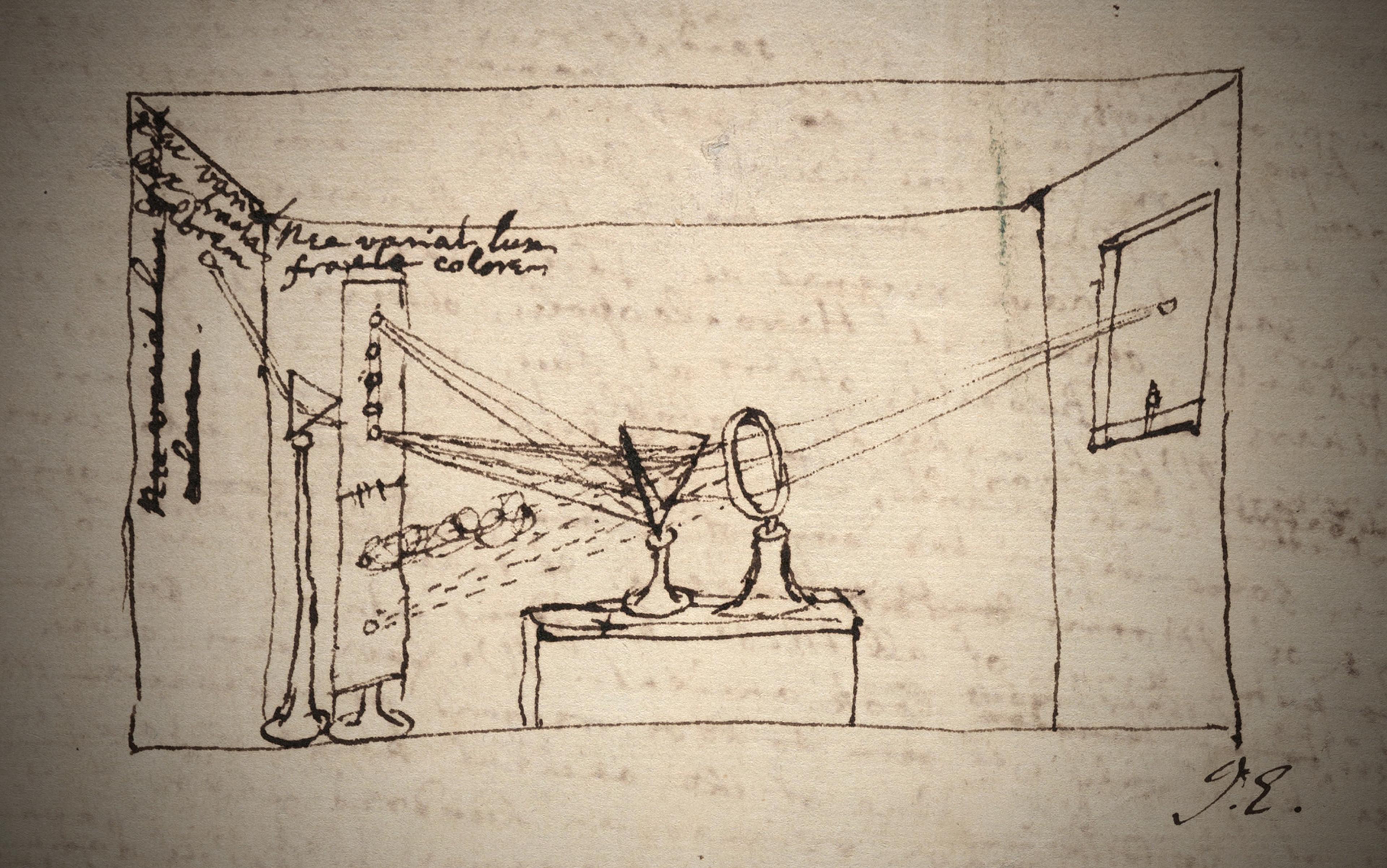

As a University of Chicago graduate student in 1952, Stanley Miller performed a famous experiment with Harold Urey, a Nobel laureate in chemistry. Their results explored the idea that life formed in a primordial soup.

Miller and Urey injected ammonia, methane and water vapor into an enclosed glass container to simulate what were then believed to be the conditions of Earth’s early atmosphere. Then they passed electrical sparks through the container to simulate lightning. Amino acids, the building blocks of proteins, soon formed. Miller and Urey realized that this process could have paved the way for the molecules needed to produce life.

Scientists now believe that Earth’s early atmosphere had a different chemical makeup from Miller and Urey’s recipe. Even so, the experiment gave rise to a new scientific field called prebiotic or abiotic chemistry, the chemistry that preceded the origin of life. This is the opposite of biogenesis, the idea that only a living organism can beget another living organism.

Seeded by comets or meteors

Some scientists think that some of the molecules important to life may be produced outside the Earth. Instead, they suggest that these ingredients came from meteorites or comets.

“A colleague once told me, ‘It’s a lot easier to build a house out of Legos when they’re falling from the sky,’” said Fred Ciesla, a geophysical sciences professor at UChicago. Ciesla and that colleague, Scott Sandford of the NASA Ames Research Center, published research showing that complex organic compounds were readily produced under conditions that likely prevailed in the early solar system when many meteorites formed.

Meteorites then might have served as the cosmic Mayflowers that transported molecular seeds to Earth. In 1969, the Murchison meteorite that fell in Australia contained dozens of different amino acids—the building blocks of life.

Comets may also have offered a ride to Earth-bound hitchhiking molecules, according to experimental results published in 2001 by a team of researchers from Argonne National Laboratory, the University of California Berkeley, and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. By showing that amino acids could survive a fiery comet collision with Earth, the team bolstered the idea that life’s raw materials came from space.

In 2019, a team of researchers in France and Italy reported finding extraterrestrial organic material preserved in the 3.3 billion-year-old sediments of Barberton, South Africa. The team suggested micrometeorites as the material’s likely source. Further such evidence came in 2022 from samples of asteroid Ryugu returned to Earth by Japan’s Hayabusa2 mission. The count of amino acids found in the Ryugu samples now exceeds 20 different types .

In 1953, UChicago researchers published a landmark paper in the Journal of Biological Chemistry that marked the discovery of the pro-chirality concept , which pervades modern chemistry and biology. The paper described an experiment showing that the chirality of molecules—or “handedness,” much the way the right and left hands differ from one another—drives all life processes. Without chirality, large biological molecules such as proteins would be unable to form structures that could be reproduced.

Today, research on the origin of life at UChicago is expanding. As scientists have been able to find more and more exoplanets—that is, planets around stars elsewhere in the galaxy—the question of what the essential ingredients for life are and how to look for signs of them has heated up.

Nobel laureate Jack Szostak joined the UChicago faculty as University Professor in Chemistry in 2022 and will lead the University’s new interdisciplinary Origins of Life Initiative to coordinate research efforts into the origin of life on Earth. Scientists from several departments of the Physical Sciences Division are joining the initiative, including specialists in chemistry, astronomy, geology and geophysics.

“Right now we are getting truly unprecedented amounts of data coming in: Missions like Hayabusa and OSIRIS-REx are bringing us pieces of asteroids, which helps us understand the conditions that form planets, and NASA’s new JWST telescope is taking astounding data on the solar system and the planets around us ,” said Prof. Ciesla. “I think we’re going to make huge progress on this question.”

Last updated Sept. 19, 2022.

Faculty Experts

Clara Blättler

Fred Ciesla

Jack Szostak

Recommended Stories

Earth could have supported crust, life earlier than thought

Earth’s building blocks formed during the solar system’s first…

Additional Resources

The Origins of Life Speaker Series

Recommended Podcasts

Big Brains podcast: Unraveling the mystery of life’s origins on Earth

Discovering the Missing Link with Neil Shubin (Ep. 1)

More Explainers

Improv, Explained

Cosmic rays, explained

Related Topics

Latest news.

Office of Sustainability

Meet A UChicagoan

Ecologist tracks how insects can devastate forests—and how to stop them

Big Brains podcast

Big Brains podcast: What dogs are teaching us about aging

Where do breakthrough discoveries and ideas come from?

Explore The Day Tomorrow Began

Department of Race, Diaspora, and Indigeneity

Course on Afrofuturism brings together UChicago students and community members

Education Lab

National study finds in-school, high-dosage tutoring can reverse pandemic-era learning loss

Around uchicago.

Lecture Series

Author and ‘Odyssey’ translator Daniel Mendelsohn to deliver Berlin Family Lectures beginning April 23

Alumni Awards

Two Nobel laureates among recipients of UChicago’s 2024 Alumni Awards

Faculty Awards

Profs. John MacAloon and Martha Nussbaum to receive 2024 Norman Maclean Faculty…

Sloan Research Fellowships

Five UChicago scholars awarded prestigious Sloan Fellowships in 2024

Convocation

Prof. John List named speaker for UChicago’s 2024 Convocation ceremony

The College

Anna Chlumsky, AB’02, named UChicago’s 2024 Class Day speaker

UChicago Medicine

“I saw an opportunity to leverage the intellectual firepower of a world-class university for advancing cancer research and care.”

Announcement

Ethan Bueno de Mesquita appointed dean of the Harris School of Public Policy

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.8: Evolution of Life

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 6259

This timeline shows the history of life on Earth. In the entire span of the time, humans are a relatively new addition.

Today, the most accepted theory of life on Earth is evolution, and there is a vast amount of evidence supporting this theory. However, this wasn’t always the case.

An introduction to evolution and natural selection can be viewed at http ://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GcjgWov7mTM .

As you view Introduction to Evolution and Natural Selection, focus on these concepts: the relationship between evolution and natural selection, the relationship between natural selection and variation, the evolution of the peppered moth.

Darwin and the Theory of Evolution

The idea of evolution has been around for centuries. In fact, it goes all the way back to the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle. However, evolution is most often associated with Charles Darwin . Darwin published a book on evolution in 1859 titled On the Origin of Species . In the book, Darwin stated the theory of evolution by natural selection. He also presented a great deal of evidence that evolution occurs.

Evolution is a change in the characteristics of living things over time. As described by Darwin, evolution occurs by a process called natural selection . In natural selection, some members of a species, being better adapted or suited to their environment, produce more offspring than others, so they pass "advantageous traits" to their offspring. Over many generations, this can lead to major changes in the characteristics of the species. Evolution explains how living things are changing today and how modern living things have descended from ancient life forms that no longer exist on Earth. As living things evolve, they generally become better suited for their environment. This is because they evolve adaptations. An adaptation is a trait that helps an organism survive and reproduce in a given environment.

Despite all the evidence Darwin presented, his theory was not well-received at first. Many people found it hard to accept the idea that humans had evolved from an ape-like ancestor, and they saw evolution as a challenge to their religious beliefs. Look at the cartoon in Figure below . Drawn in 1871, it depicts Darwin himself as an ape. The cartoon reflects how many people felt about Darwin and his theory during his own time. Darwin had actually expected this type of reaction to his theory and had waited a long time before publishing his book for this reason. It was only when another scientist, named Alfred Russel Wallace, developed essentially the same theory of evolution that Darwin put his book into print.

Charles Darwin’s name is linked with the theory of evolution. This cartoon from the 1870s makes fun of both Darwin and his theory.

Although Darwin presented a great deal of evidence for evolution in his book, he was unable to explain how evolution occurs. That’s because he knew nothing about genes. As a result, he didn’t know how characteristics are passed from parents to offspring, let alone how they could change over time.

Evolutionary Theory After Darwin

Since Darwin’s time, scientists have gathered even more evidence to support the theory of evolution. Some of the evidence comes from fossils , and some comes from studies that show how similar living things are to one another. By the 1930s, scientists had also learned about genes. As a result, they could finally explain how characteristics of organisms could pass from one generation to the next and change over time.

Using modern technology, scientists can now directly compare the genes of living species . The more genes different species share in common, the more closely related the species are presumed to be. Consider humans and chimpanzees. They share about 98% of their genes. This means that they shared a common ancestor in the not-too-distant past. This is just one of many pieces of evidence that show we are part of the evolution of life on Earth.

Misconceptions About Evolution

Today, evolution is still questioned by some people. Often, people who disagree with the theory of evolution do not really understand it. For example, some people think that the theory of evolution explains how life on Earth first began. In fact, the theory explains only how life changed after it first appeared. Some people think the theory of evolution means that humans evolved from modern apes. In fact, the theory suggests humans and modern apes have a common ancestor that lived several million years ago. These and other misconceptions about evolution contribute to the controversy that still surrounds this fundamental principle of biology.

- Life began on Earth at least 3.5 to 4 billion years ago, and it has been evolving ever since.

- Darwin stated the theory of evolution by natural selection, presenting a great deal of evidence to support his theory.

- Evolution is a change in the characteristics of living things over time. Evolution occurs by natural selection.

- Characteristics of organisms are passed from one generation to the next through their genes.

Making Connections

Explore more.

Use this resource to answer the questions that follow.

- Natural Selection at evolution.berkeley.edu/evosit...election.shtml.

- What is meant by differential reproduction?

- What is the end result of this process?

- What three things are necessary for evolution by natural selection?

- What is evolution?

- What is natural selection?

- Briefly, explain the theory of evolution.

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Unit 27: History of life on Earth

About this unit.

This unit is part of the Biology library. Browse videos, articles, and exercises by topic.

Formation of Earth and early life

- Earth formation (Opens a modal)

- Beginnings of life (Opens a modal)

- Origins of life (Opens a modal)

- Hypotheses about the origins of life (Opens a modal)

- The RNA origin of life (Opens a modal)

- RNA world (Opens a modal)

The diversification of life

- Ozone layer and eukaryotes show up in the Proterozoic eon (Opens a modal)

- First living things on land clarification (Opens a modal)

- Biodiversity flourishes in Phanerozoic eon (Opens a modal)

- Human evolution overview (Opens a modal)

Radiometric dating

- Chronometric revolution (Opens a modal)

- Carbon 14 dating 1 (Opens a modal)

- Carbon 14 dating 2 (Opens a modal)

- Potassium-argon (K-Ar) dating (Opens a modal)

- K-Ar dating calculation (Opens a modal)

- Atomic number, atomic mass, and isotopes (Opens a modal)

Advertisement

How we will discover the mysterious origins of life once and for all

Seventy years ago, three discoveries propelled our understanding of how life on Earth began. But has the biggest clue to life's origins been staring biologists in the face all along?

By Michael Marshall

30 October 2023

The constant changing landscape of Earth may be a vital part of the story of the origins of the first ecosystems.

MARK GARLICK/Spl/Alamy;

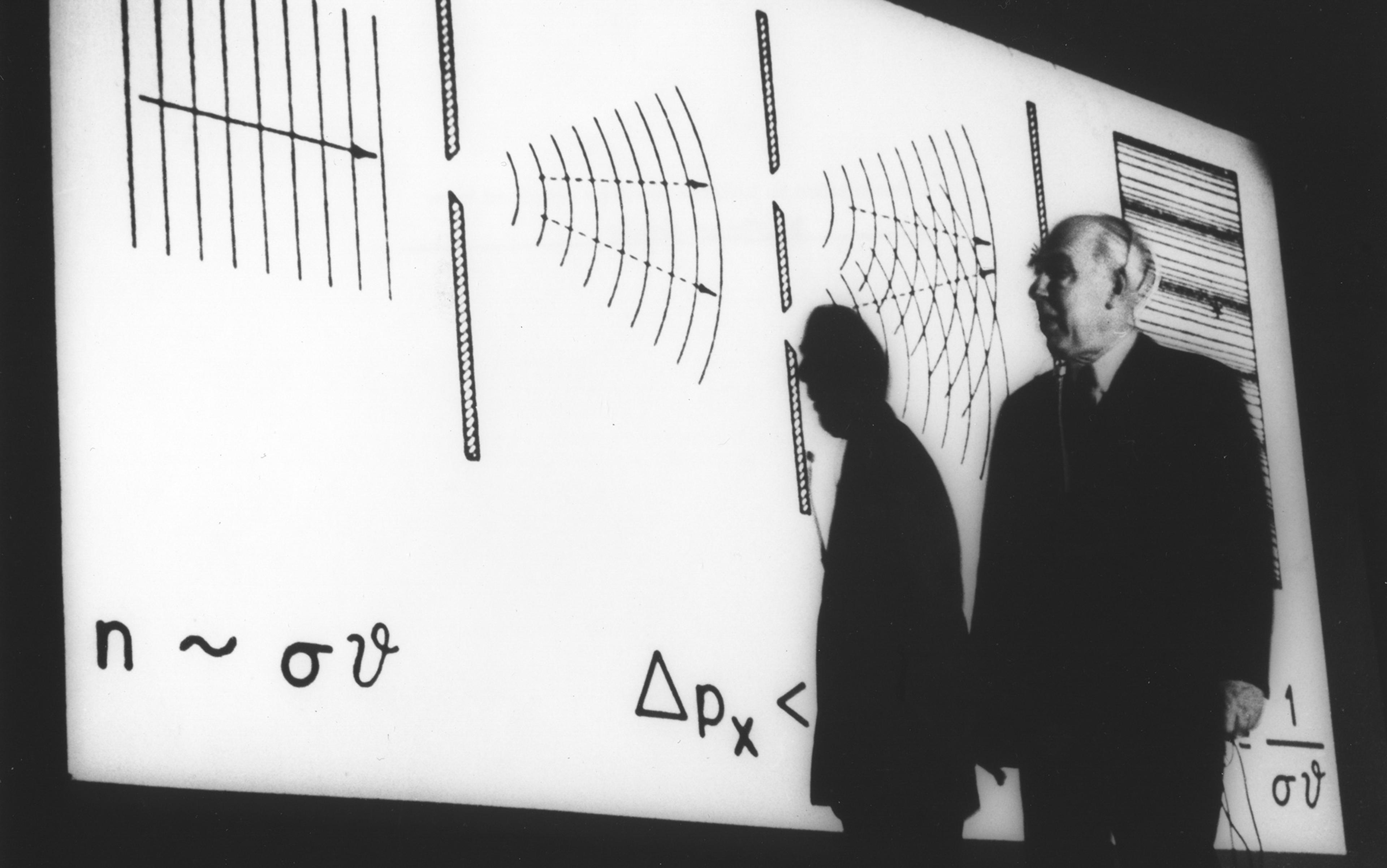

HOW did life on Earth begin? Until 70 years ago, generations of scientists had failed to throw much light on biology’s murky beginnings. But then came three crucial findings in quick succession.

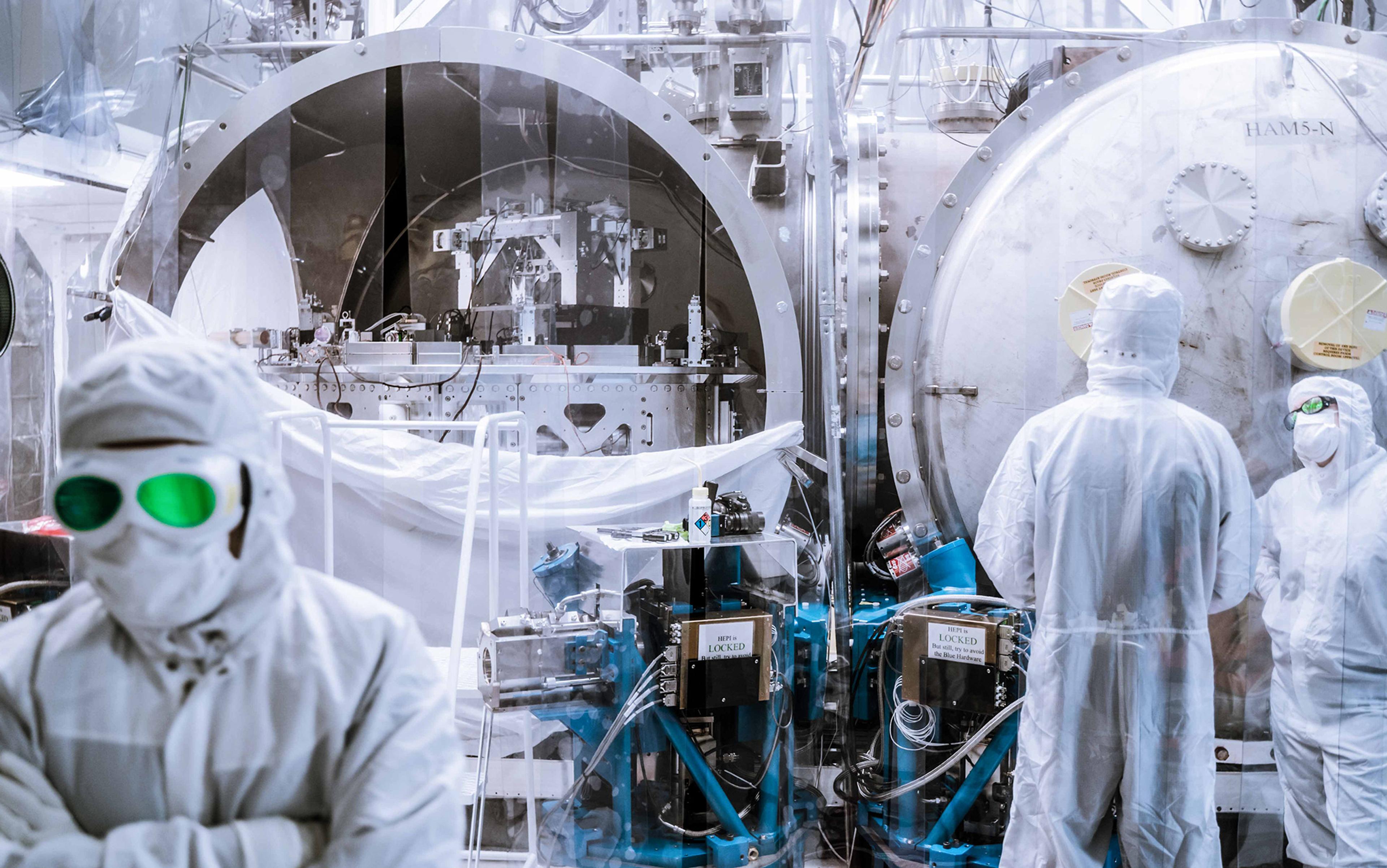

In April 1953, the race to uncover the structure of DNA reached its climax. Geneticists soon realised that its double helix form could help explain how life replicates itself – a fundamental property thought to have appeared at or around the origin of life. Just three weeks later, news broke of the astonishing Miller-Urey experiment, which showed how a simple cocktail of chemicals could spontaneously generate amino acids, vital for building the molecules of life. Finally, in September 1953, we gained our first accurate estimate for the age of Earth, giving us a clearer idea of exactly how old life might be.

At that point, we seemed poised to finally understand life’s origins. Today, conclusive answers remain elusive. But the past few years have brought real signs of progress.

For instance, we have found that life’s ability to replicate is not wholly reliant on DNA. We also have a far better idea of the conditions on early Earth when life first appeared – and we are beginning to conduct experiments into how it emerged that are much more sophisticated than Miller-Urey.

A radical new theory rewrites the story of how life on Earth began

It has long been thought that the ingredients for life came together slowly, bit by bit. Now there is evidence it all happened at once in a chemical big bang

So, 70 years on from that incredible year of breakthroughs, how has our picture of life’s origins changed? And what remains to be figured out before we can satisfactorily answer biology’s ultimate question?

Definitions of life

“I think in the 50s we knew very little about life,” says …

Article amended on 3 November 2023

Sign up to our weekly newsletter.

Receive a weekly dose of discovery in your inbox! We'll also keep you up to date with New Scientist events and special offers.

To continue reading, subscribe today with our introductory offers

No commitment, cancel anytime*

Offer ends 2nd of July 2024.

*Cancel anytime within 14 days of payment to receive a refund on unserved issues.

Inclusive of applicable taxes (VAT)

Existing subscribers

More from New Scientist

Explore the latest news, articles and features

Life’s vital chemistry may have begun in hot, cracked rock

It's time to accept that we are in the anthropocene once and for all.

Subscriber-only

Mars's gravitational pull may be strong enough to stir Earth's oceans

Surprise decision not to define the anthropocene shocks scientists, popular articles.

Trending New Scientist articles

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- Image & Use Policy

- Translations

UC MUSEUM OF PALEONTOLOGY

Understanding Evolution

Your one-stop source for information on evolution

- ES en Español

Important events in the history of life

A timeline can provide additional information about life’s history not visible on an evolutionary tree. These include major geologic events, climate changes, radiations of organisms into new habitats, changes in ecosystems, changes in continental positions, and widespread extinctions. Explore the timeline below to review some of the important events in life’s history.

(If the timeline doesn’t work, view the Text-only version .)

- More Details

- Evo Examples

- Teaching Resources

Read more about the origins of life on Earth with this advanced tutorial or about human evolution in this brief summary.

To learn more about the formation of the Earth, the building blocks of life, and the conditions required for life to arise, visit A Place for Life: A special astronomy exhibit of Understanding Evolution .

To get a more detailed timeline of the history of life and learn more about deep time in general, visit the ChronoZoom Time Atlas of Earth History and Big History .

Learn more about the origin of life in context: From the origin of life to the future of biotech: The work of Andy Ellington , a research profile.

Learn more about human evolution in context: When it comes to evolution, headlines often get it wrong , a news brief with discussion questions.

Teach your students about timelines: A long time , a classroom activity for grades K-2.

Teach your students about the history of life: What came first? , a classroom activity for grades 6-8.

Find additional lessons, activities, videos, and articles that focus on the history of life.

How we know what happened when

Mechanisms: the processes of evolution

Subscribe to our newsletter

- Teaching resource database

- Correcting misconceptions

- Conceptual framework and NGSS alignment

- Image and use policy

- Evo in the News

- The Tree Room

- Browse learning resources

- Introduction to Ecology; Major patterns in Earth’s climate

- Behavioral Ecology

- Population Ecology 1

- Population Ecology 2

- Community Ecology 1

- Community Ecology 2

- Ecosystems 1

- Ecosystems 2

- Strong Inference

- What is life?

- What is evolution?

- Evolution by Natural Selection

- Other Mechanisms of Evolution

- Population Genetics: the Hardy-Weinberg Principle

- Phylogenetic Trees

Earth History and History of Life on Earth

- Origin of Life on Earth

- Gene expression: DNA to protein

- Gene regulation

- Cell division: mitosis and meiosis

- Mendelian Genetics

- Chromosome theory of inheritance

- Patterns of inheritance

- Chemical context for biology: origin of life and chemical evolution

- Biological molecules

- Membranes and Transport

- Energy and enzymes

- Respiration, chemiosmosis and oxidative phosphorylation

- Oxidative pathways: electrons from food to electron carriers

- Fermentation, mitochondria and regulation

- Why are plants green, and how did chlorophyll take over the world? (Converting light energy into chemical energy)

- Carbon fixation

- Recombinant DNA

- Cloning and Stem Cells

- Adaptive Immunity

- Human evolution and adaptation

Learning Objectives

- Connect changes in the Earth’s atmosphere with evolutionary changes in the Earth’s biosphere.

- Explain the fundamentals of stratigraphy.

- Identify the appropriate uses and limitations for various methods of dating, including carbon-14, potassium-40.

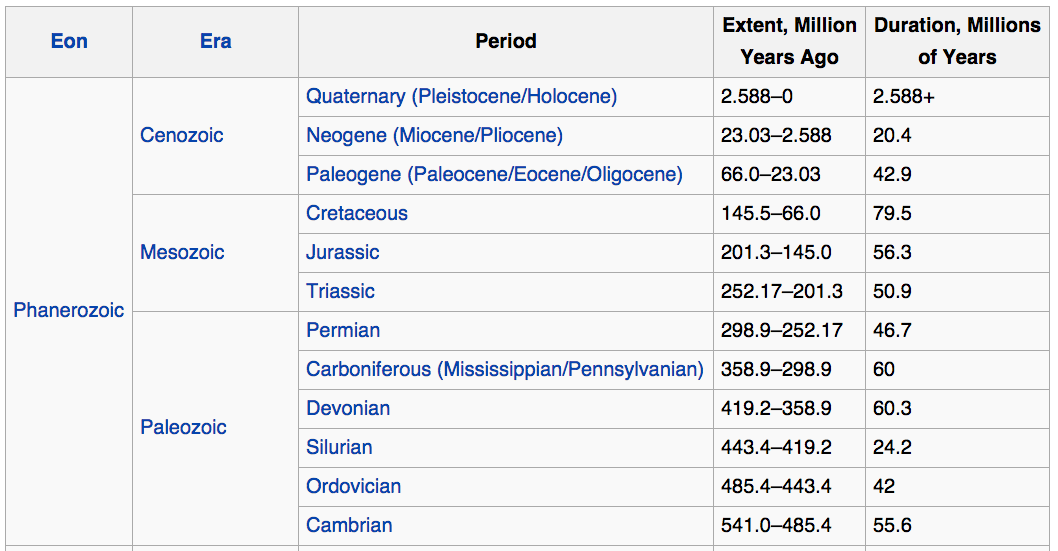

- Identify major geological periods with respect to the history of life on Earth.

- Recognize the features of adaptive radiations and mass extinctions.

Geology, Earth history, and biological evolution

Evolution writ large takes a great deal of time. Natural selection will favor different genetic variants as geologic conditions change, such as climate, chemical composition, and sea level. A key of Charles Darwin’s thinking was his study and familiarity with the latest advances in the science of geology, including the works of Hutton and Lyell. And interpretation of the fossil record, and inferring the sequence of evolutionary changes, would be impossible without a grounding in the fundamentals of stratigraphy.

Fossils are found in sedimentary rocks

There are 3 different kinds of rocks:

- igneous – rock formed from cooling of lava. Any organismal remnants are destroyed by the extreme heat of the lava.

- metamorphic – rock whose crystal structure is altered by extreme heat and high pressure when buried miles deep in the Earth’s crust; may be formed from either igneous or sedimentary rock. Any fossils contained in sedimentary rock are destroyed during the transformation to metamorphic rock.

- sedimentary – rock formed by deposition of fine sand and particles of organic and inorganic debris at the bottoms of oceans and lakes, compressed and often visible as layered rock formations. May contain fossils.

Dating and ordering the geological record

Stratigraphy applies to sedimentary rock formations. The fundamental principle is that newer layers are always deposited on top of older layers. Therefore, a vertical dig reveals a historical record, with deeper digs revealing older sedimentary deposits. However, crustal movements and uplifts may cause these layers to tilt, fold and even become inverted in some locations. In addition, erosion can cause loss of layers and gaps in the rock record, called unconformities .

Stratigraphy of the Grand Canyon. Image from Wikipedia

Radiometric dating

Stratigraphy reveals the order of geological events, but not their absolute dates. Depending on the age of the rocks or samples and their type, various radioisotope decay methods may be used to estimate the absolute ages of rocks found in different layers. This page by Dr. Roger Wiens has a thorough explanation of how carbon-14 and potassium-40 and other isotopes are used to date rocks and fossils of different ages. In brief:

- Potassium-40 (K-40) decays to argon-40 (Ar-40); half-life = 1.26 billion years; used to date formation of igneous rocks. Ar-40 found trapped in the rock is compared to amount of K-40 remaining. A 1:1 ratio of K-40 to Ar-40 indicates the igneous rock has an age of 1 half-life, or 1.26 billion years.

- Uranium-238 (U-238) decays to lead-206 (Pb-206); half-life = 4.5 billion years; used to date zircons (see “How to Date a Planet” video above). Again, the ratio of U-238 to Pb-206 reveals how many half-lives have passed since the zircon crystal was formed.

- Carbon-14 (C-14) decays to nitrogen-14 (N-14); half-life = 5715 years; used to date organic matter. In this case, the amount of the daughter isotope (N-14) is uninformative, because N-14 is the common isotope of nitrogen and occurs at high levels in all organic matter and in the atmosphere. Only the amount of C-14 compared to the amount of C-12 matters. The ratio of C-14 to C-12 has been mostly constant over the last 100,000 years, so newly created (by photosynthesis) organic matter starts out with a certain ratio of C-14 to C-12 that is similar to the present-day atmospheric ratio of C-14 to C-12. Depletion of C-14 relative to C-12 is used to date the age of organic matter. After 5700 years, the ratio of C-14 to C-12 will be only half of the initial ratio of C-14 to C-12.

Amount of parent isotope remaining after passage of time, indicated in half-lives. from https://www.asa3.org/ASA/resources/wiens.html

This figure shows exponential decay of a parent radioactive isotope, contrasted with the linear decrease of sand in an hourglass. For samples containing organic carbon, the fraction of C-14 remaining in the sample can be used to determine how many half-lives, and hence years, have passed since the organic matter was formed.

A common misconception is that scientists use carbon-14 to date rocks or fossils that are millions of years old, such as fossil dinosaur bones from 100 million years ago. Instead, scientists date igneous rocks found in layers above and below the sedimentary rocks containing the fossils. Why isn’t carbon-14 useful for dating fossil dinosaur bones?

Plate Tectonics and Continental Drift

During this time the continents have been in constant motion across the surface of the earth, splitting and merging. This video animation reconstructs continental movements for the last 560 million years:

Often the major eras and periods of Earth history are arranged on a clock face in an effort to visualize the amount of time that has passed since each period, as such:

Major periods of earth history, shown as a clockface, with time going from 4.5 billion years ago at the 12:00 start position proceeding clockwise to the present at the 12:00 position. Image from Wikipedia: By WoudloperDerivative work: Hardwigg – File:Geologic_clock.jpg, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11926892

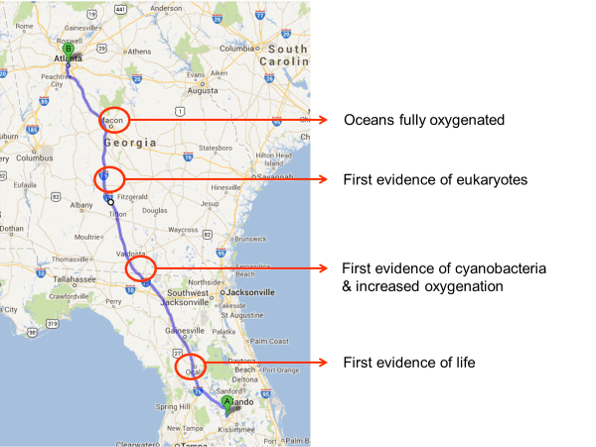

However, humans are very bad at thinking about time. But we’re pretty good at thinking about distance. So let’s “map” the different periods of Earth history and major evolutionary milestones onto a—you guessed it—map. Let’s take a trip from Disney World to a classroom inside the Clough building on Georgia Tech campus. If the location of Disney World in Orlando, Florida is the origin of the Earth (A), and the Clough building is present day (B), that means we have 441 miles to travel 4.6 billion years.

- The oldest evidence for life is about 3.8 billion years old. That means we’ve traveled almost a quarter of the whole distance to about 70 miles from Orlando, a bit south of Ocala, before there is any evidence of life on Earth.

- While there was no oxygen in early Earth’s atmosphere or oceans, by about 3.5 Ga, we start seeing the first traces of O2 in the atmosphere. These increases in ocean and atmospheric oxygen levels become quite large with appearance of cyanobacteria about 2.7 billion years ago (Bya). That means it takes almost half trip: we’ve traveled about 200 miles and we’re at the GA/FL border before we start seeing evidence of increasing oxygen levels on Earth. The first eukaryotes appear in the fossil record after oxygen begins to accumulate about 1.5 BYA, about halfway between Tifton and Macon, near Cordele, GA. This isn’t much of a landmark, but we could stop and get lunch. Oxygen didn’t accumulate all at once, and evidence indicates that the oceans weren’t fully oxygenated until 850 milling years ago (Mya), which puts us all the way up to Macon, GA – only about 80 miles from Tech.

Here is our map so far:

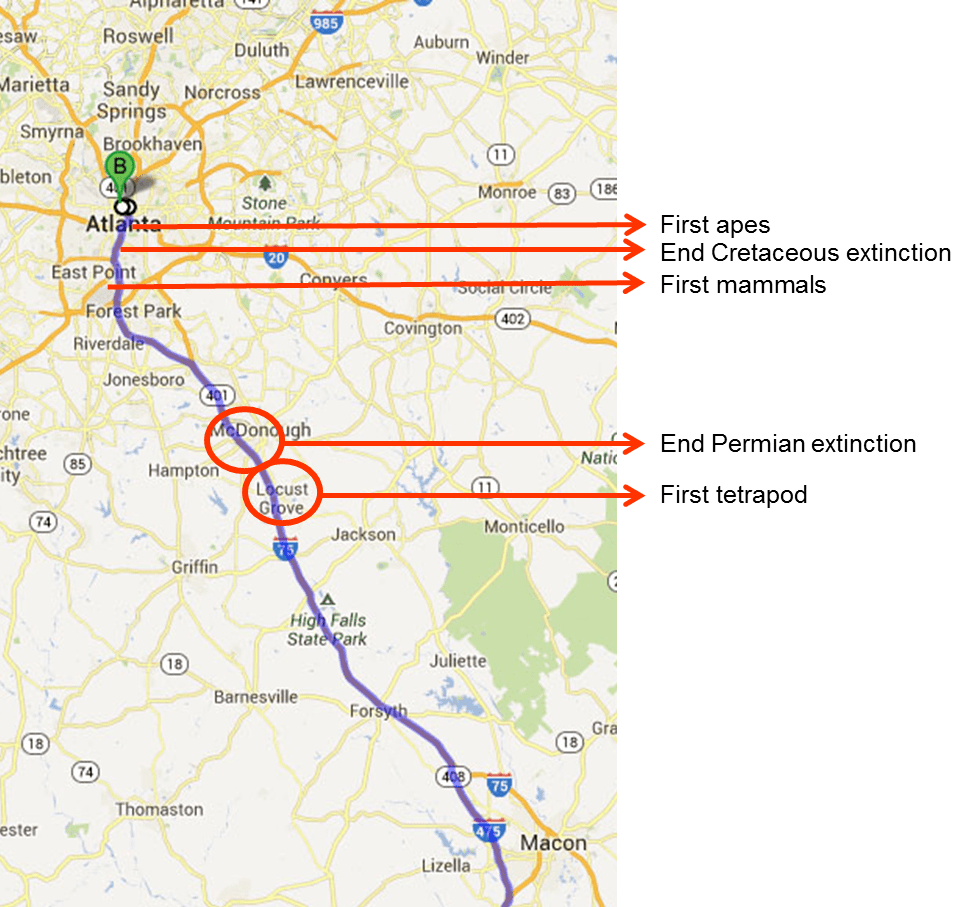

Now let’s zoom in a little:

- Much of the life on earth was singled celled until shortly before the Cambrian “explosion,” when we see emergence of all modern animal phyla. The Cambrian radiation (meaning rapid evolutionary diversification) occurred approx. 540 Mya, which puts it north of Macon in High Fall State Park. This is the first part of the Paleozoic (early animals) era.

- The largest mass extinction in the fossil record occurred at the end of the Permian period (299-252 Mya), near McDonough, GA.

- The first mammals appear during the Jurassic period (200-145 Mya), or just inside the I-285 Perimeter.

- Dinosaurs became extinct at the end of the Cretaceous period (145-66 Mya). This is solidly inside the Perimeter.

- The first apes appear in the fossil record about 25 Mya, or near the intersection of I-20 and the I-75/I-85 Downtown Connector. We’re almost to Tech campus now!

- Human evolution occurs entirely on Tech campus. The fossil Lucy ( Australopithecus ) dates to approximately 3 Mya, or right around Tech Tower.

- Modern Homo sapiens arise and migrate out of Africa inside Clough Commons. Neanderthals go extinct inside the classroom with us. Recorded human history occurs in the current Holocene epoch, from 11,700 years ago to the present, or about 6 feet from where you are sitting in the classroom. The Holocene epoch is the last part of the Quarternary period (2.59 Mya-present), which in turn is the last part of the Cenozoic era (66 Mya-present), which in turn is the last part of the Phanerozoic eon (540 Mya-present).

Co-evolution of life and the planet

The geochemistry of the Earth’s atmosphere, water and land surfaces have shaped the evolutionary history of life. And in turn, major changes in the biosphere have profoundly altered the chemistry of the Earth’s water, atmosphere, and land surfaces. The figure below shows milestones in the 4.5-billion year history of the Earth, changes in atmospheric oxygen levels, and the timing of the origin of microbial life and the origin of eukaryotes.

Atmospheric and oceanic conditions have changed over time alongside (and promoting) conditions of organismal evolution Credit: Brian Kendall, Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Waterloo

Adaptive Radiations

The Cambrian “explosion” refers to an increase in biodiversity of multicellular organisms at the start of the Cambrian, 540 million years ago. Multicellular life appeared only several tens of millions of years before the start of the Cambrian, as enigmatic fossils ( Ediacaran biota ) exhibiting body plans unlike present-day animals. These largely disappeared and were replaced by Cambrian fauna, whose variety includes all of the body plans found in present-day animal phyla. The appearance of Cambrian fauna span millions of years; they did not all appear simultaneously as the term “explosion” inaccurately implies.

Periods of increasing biodiversity and rapid speciation are called evolutionary radiations . They occur when new ecological niches become available, as after a mass extinction. They may also occur in response to an evolutionary innovation. One example would be the evolution of jaws. The ability to bite gave predators a huge advantage. Prey species adapted in a variety of ways, such as faster speed, body armor, defensive weapons such as horns and stingers, chemical defenses in the form of poison, larger body size, smaller body size, etc.

The Cambrian radiation also coincides with an increase in free oxygen to near-present day levels.

O2 build-up in the Earth’s atmosphere. Red and green lines represent the range of the estimates while time is measured in billions of years ago (Ga). Stage 1 (3.85–2.45 Ga): Practically no O2 in the atmosphere. Stage 2 (2.45–1.85 Ga): O2 produced, but absorbed in oceans and seabed rock. Stage 3 (1.85–0.85 Ga): O2 starts to gas out of the oceans, but is absorbed by land surfaces. Stages 4 and 5 (0.85–present): O2 sinks filled and the gas accumulates.

The increase in oxygen enabled the evolution of larger bodies and organs and tissues, such as brains, with high metabolic rates.

The increase in oxygen is a dramatic example of how life can alter the planet. Evolution of oxygenic photosynthesis changed the planet’s atmosphere over billions of years, and in turn caused radical shifts in the biosphere: from an anoxic environment populated by anaerobic, single-celled prokaryotes, to eukaryotes living in a micro-aerophilic (low-oxygen) environment, to multicellular-organisms in an oxygen-rich environment.

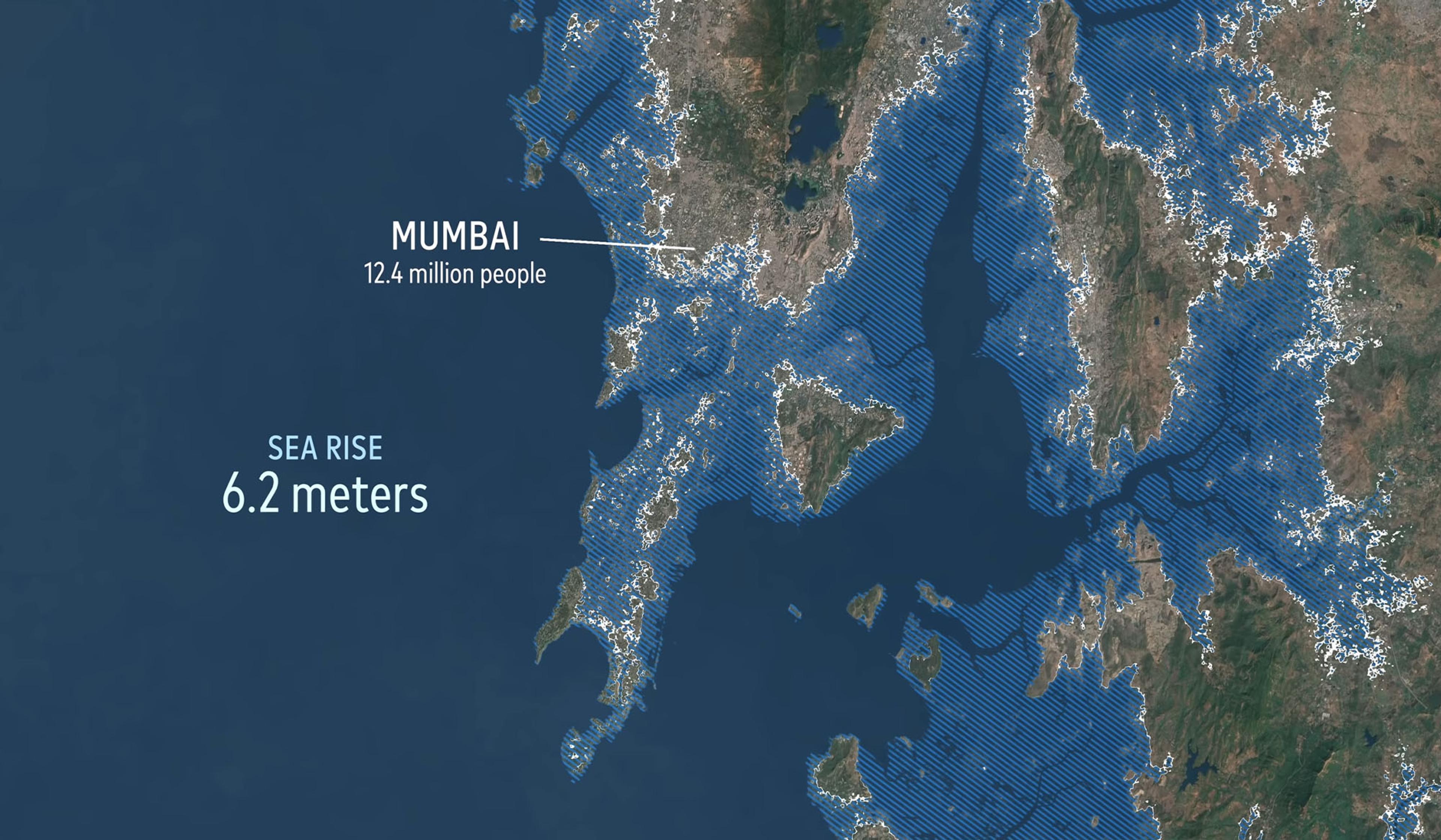

Human impacts are the latest in a succession of major evolutionary influences. We are now altering the planet with as yet undetermined consequences for life on Earth.

No other planet in our solar system has oxygen gas in the atmosphere. Oxygen is highly reactive, and quickly consumed by oxidation reactions. On Earth, oxygenic photosynthesis continually replenishes the oxygen consumed by respiration and other oxidative processes (e.g., rusting of iron, weathering of rocks). The history of oxygen gas in the Earth’s atmosphere sums up the history of life.

- The early Earth had no oxygen gas

banded iron formation, Karijini National Park, Western Australia from Wikipedia

- Oxygen dissolved in the water column led to more efficient (aerobic) metabolism, and eventually enabled the evolution of eukaryotes (around 2 BYA), and the first multicellular organisms (around 800 MYA).

- Oxygen gas in the upper atmosphere formed the ozone layer. The ozone layer absorbed harmful UV rays and allowed animals and plants to colonize land surfaces (350 MYA).

- Burial of large quantities of organic material in anaerobic sediments (eventually turning into coal and petroleum) allowed oxygen to accumulate in the atmosphere to present-day levels. Q: why is burial of organic carbon necessary for oxygen to accumulate in the atmosphere?

Here’s a link to an HHMI Interactive on the oxygen history on earth. Select region 2 and click on “Howie” to step into an explanation of the two hypotheses of how oxygen outgassed into the atmosphere.

Temperature and sea level

The Earth experienced large swings in global temperature, from “snowball” to hothouse, and intermittent glaciation. Note the conditions during the entire period of hominid evolution (circa 3 Mya) and recorded human history (circa 10 Kya). Also note the change in scale on the X axis (time).

Reconstruction of global temperature in the Phanerozoic. Note that these are a series of different linear scales on the time axis. Click the image to enlarge and for more information on the sources of data used to construct this timeline. From Wikimedia Commons; Image Credit: Glen Fergus.

Reconstruction of Phanerozoic atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations. Time axis is a log scale. Click the image for more information about the data and analysis used to construct this timeline. by Gavin Foster, Dana Royer and Dan Lunt

Multiple factors caused these large swings in global temperature, including changes in solar output, extreme volcanic activity, meteor strikes, and atmospheric greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide. The figure above by Foster et al. shows that carbon dioxide levels above 400 ppm are now the highest in the past 10 million years.

And this recent comic from XKCD graphs what we know about the Earth’s temperature from ~20,000 BC to present day, with projections for the future based on current CO2 emission patterns:

A Timeline of Earth’s Average Temperature Since the Last Ice Age Glaciation. https://xkcd.com/1732/

Earthviewer app for tablets allows visualization of Earth through time

Another Youtube video explaining basic principles of stratigraphy

Land plants gave oxygen to predators

Radiometric Dating: A Christian Perspective a long and thorough, and yet very readable, explanation of how radiometric dating works, how the techniques are calibrated, the sources of error. The “Christian perspective” is about countering young-Earth misconceptions from any religious belief.

Recent papers of interest

M. O. Clarkson, S. A. Kasemann, R. A. Wood, T. M. Lenton, S. J. Daines, S. Richoz, F. Ohnemueller, A. Meixner, S. W. Poulton, E. T. Tipper. Ocean acidification and the Permo-Triassic mass extinction. Science , 2015 DOI: 10.1126/science.aaa0193

UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 9: Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure – Dating methods such as carbon-14 and potassium-40 are important tools for studying the history of life on Earth, and are used in other scientific fields such as archaeology and geology. The ability to accurately date rocks and fossils using various dating methods is essential for advancing scientific research, determining the location and viability of fossil-fuel-based industrial endeavors, and developing infrastructure projects that require knowledge of geological history.

5 Responses to Earth History and History of Life on Earth

So, from the youtube video, it’s predicted that the continents will merge back together?

Apparently so, but this is beyond my area of expertise.

Maybe only old farts like me will like this, but I do like it: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EMwxwRA9Xr8

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/22/science/fungi-fossils-plants.html Story about discovery of billion-year-old microfossils with morphology and chitinous cell wall of fungi, predating colonization of land by plants. What did these fungi eat?

https://www.trollart.com/wp-content/uploads/photo-gallery/imported_from_media_libray/Ages-of-Rock-CORRECT-copy.jpg?bwg=1543862013

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

- Entries RSS

- Comments RSS

- Sites@GeorgiaTech

- Search for:

Creative Commons License

- eradication of Asian tiger mosquitos

- gut bacteria and stunted growth

- gut pathogens and autoimmune disease

- human milk oligosaccharides

- Legionella and mitochondria

- mannosides and uropathogenic E. coli

- origin of sickle cell mutation

- trehalose and C. difficile

- Uncategorized

Module 3: History of Life

Why it matters: history of life, why discuss the history of life on earth.

Human beings are just one of countless examples of life on Earth. The sheer amount of diversity can seem overwhelming. However, over the years, scientists have developed tools and methods to organize all known living organisms. With the phylogenetic tree and the taxonomic classification system, scientists have grouped and organized organisms by domain, kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species.

The term kingdom is likely familiar to you, and you may even know the genus and species names of some organisms, as these names are used to create scientific names such as Canis lupus familiaris (dogs) and Felis catus (cats). But how does this type of organization matter in everyday life?

Evolutionary biologists could list many reasons why understanding phylogeny is important to everyday life in human society. For botanists, phylogeny acts as a guide to discovering new plants that can be used to benefit people. Think of all the ways humans use plants—food, medicine, and clothing are a few examples. If a plant contains a compound that is effective in treating disease, scientists might want to examine all of the relatives of that plant for other useful drugs.

Learning Outcomes

- Explain the theory of evolution

- Define species and identify how species form

- Discuss the ways populations evolve

- Read and analyze a phylogenetic tree that documents evolutionary relationships

Contribute!

Improve this page Learn More

- Why It Matters: History of Life. Authored by : Shelli Carter and Lumen Learning. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Biology 2e. Provided by : OpenStax. Located at : http://cnx.org/contents/[email protected] . License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/biology-2e/pages/1-introduction

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

The meaning of life: early continental and analytic perspectives.

The question of the meaning of life is one that interests philosophers and non-philosophers alike. The question itself is notoriously ambiguous and possibly vague. In asking about the meaning of life, one may be asking about the essence of life, about life’s purpose, about whether and how anything matters, or a host of other things.

Not everyone is plagued by questions about life’s meaning, but some are. The circumstances in which one does ask about life’s meaning include those in which: one is well off but bothered by either a sense of dissatisfaction or the prospect of bad things to come; one is young at heart and has a sense of wonder; one is perplexed by the discordant plurality of things and wants to find some unity in all the diversity; or one has lost faith in old values and narratives and wants to know how to live in order to have a meaningful life.

We may read our ancestors in such a way that warrants the claim that the meaning of life has been a human concern from the beginning. But it was only early in the nineteenth century that writers began to write directly about “the meaning of life.” The most significant writers were: Schopenhauer, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, and Tolstoy. Schopenhauer ended up saying that the meaning of life is to deny it; Kierkegaard, that the meaning of life is to obey God passionately; Nietzsche, that the meaning of life is the will to power; and Tolstoy, that the meaning of life lies in a kind of irrational knowledge called “faith.”

In the twentieth century, in the Continental tradition, Heidegger held that the meaning of life is to live authentically or (alternatively) to be a guardian of the earth. Sartre espoused the view that life is meaningless but urged us nonetheless to make a free choice that would give our lives meaning and responsibility. Camus also thought that life is absurd and meaningless. The best way to cope with this fact, he held, is to live life with passion, using everything up, and with an attitude of revolt, defiance, or scorn.

In the Anglo-American tradition, William James held that life is meaningful and worth living because of a spiritual order in which we should believe, or else that it is meaningful when there is a marriage of ideals with pluck, will, and the manly virtues; Bertrand Russell argued that to live a meaningful life one must abandon private and petty interests and instead cultivate an interest in the eternal; Moritz Schlick argued that the meaning of life is to be found in play; and A. J. Ayer asserted that the question of the meaning of life is itself meaningless.

All of these set the table for a veritable feast of philosophical writing on the meaning of life that began in the 1950s with Kurt Baier’s essay “The Meaning of Life,” followed in 1970 by Richard Taylor’s influential essay on the same topic, followed shortly by Thomas Nagel’s important 1971 essay on “The Absurd.” See “Meaning of Life: The Analytic Perspective” for more on the course of the debate in analytic philosophy about the meaning of life.

Table of Contents

- The Origin of the English Expression “the Meaning of Life”

- Questions about the Meaning of Life

- The Broader Historical Background

- Schopenhauer

- Kierkegaard

- Some Common Aspects of the Lives of Schopenhauer, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, and Tolstoy

- References and Further Reading

1. Background

A. the origin of the english expression “the meaning of life”.

The English term “meaning” dates back to the fourteenth century C.E. Its origins, according to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), lie in the Middle English word “meenyng” (also spelled “menaynge,” “meneyng,” and “mennyng”).

In its earliest occurrences, in English original compositions as well as in English translations of earlier works, meaning is most often what, on the one hand, sentences, utterances, and stories, and, on the other hand, dreams, visions, signs, omens, and rituals have or might have. One asks about the meaning of some puzzling utterance, or of the writing on the wall, or of the vision that appeared to somebody in the night, or of the ritual performed on a hallowed occasion. Meaning is often conceived of as something non-obvious and somewhat secretive, discernible only by a seer granted with special powers.

It is much later that life is spoken of as something that might, or might not, have meaning in this sense. Such speech would have to wait upon the development of the concept of life as something like a word, a linguistic utterance, a narrative, a story, a gesture, a puzzling episode, a sign, a dream, a vision, or a surface phenomenon that points to some deep inner essence, to which it would be proper to inquire into its meaning, or to apply epithets like “meaningful” or “meaningless.” One of the earliest instances of the occurrence of the concept “life” as such a thing, as signifying something that might or might not have something like meaning, appears in Shakespeare’s Macbeth (c. 1605), where Macbeth characterizes life as “a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.” But notice that even here the words “meaning” and “life” are not linked.

The OED ‘s definition of “meaning” in something like our sense is “The significance, purpose, underlying truth, etc., of something.” Further elaboration of early uses of the word gives us, “That which is indicated or expressed by a (supposed) symbol or symbolic action; spec. a message, warning, idea, etc., supposed to be symbolized by a dream, vision, omen, etc.” A bit later, in one of its senses, meaning takes on the sense in which it is the “signification; intention; cause, purpose; motive, justification,” . . . “[o]f an action, condition, etc.” Finally we get the sense that most nearly concerns us here: “Something which gives one a sense of purpose, value, etc., esp. of a metaphysical or spiritual kind; the (perceived) purpose of existence or of a person’s life. Freq. in the meaning of life .” (All this is from the OED .)

The first English use of the expression “the meaning of life” appeared in 1834 in Thomas Carlyle’s (1795-1881) Sartor Resartus II. ix, where Teufelsdrockh observes, “our Life is compassed round with Necessity; yet is the meaning of Life itself no other than Freedom.” The usage shortly caught on, and over the next century and a half the phrase “the meaning of life” became common. The adjective “meaningful” did not appear until 1852, the noun “meaningfulness” until 1904.

b. Questions about the Meaning of Life

The most familiar form of the question(s) about the meaning of life is simply, “What is the meaning of life?” Although the form of the question is one, when it is asked, any one (or more) of several different senses may be intended. Here are some of the more common of them.

(1) In some cases, what the seeker seeks is the kernel, the inner reality, the core, or the essence, underlying some phenomenon. Thus one might ask what his essence, his true self is, and then feel that he has found the meaning of his life if he discovers that true self.

(2) In other cases, the question is about the point, aim, object, purpose, end, or goal of life, typically one’s own. Here, in some cases, the question is about some pre-existing purpose that the questioner might (or might not) discover; in other cases, the question might be about some end or purpose the agent might invent or create and give her life. The latter questioner, when she is successful, may believe that her life has a meaning because she herself has given it one.

(3) In yet other cases, the question of the meaning of life is that of whether our lives, and anything we do within them, matter, or have any sort of importance. If one can show that they matter, and in virtue of what they do, one will have provided a substantive answer to the question of the meaning of life. A common, but not universal, assumption on this score is that our lives have significance and importance only if they issue in some lasting achievement the ravages of time will not destroy.

(4) In still other cases, what bothers the questioner is the discord, plurality, and chaotic nature of his apparent empirical life as it is actually lived. He can make no sense of it; there is no rhyme or reason to it. The drive here, one might well think, is to see one’s life as intelligible, as something that makes sense. The discovery or invention of some kind of unity in his life would amount to an answer to his question, “What is the meaning of life?”

(5) Yet another thing the question about the meaning of life can be is a request for a narrative or picture, a way of seeing life (perhaps a metaphorical one) that enables one to make sense of it and achieve a sense of meaning while living it. And so we get “Life is a bowl of cherries” and various and sundry religious narratives.

(6) Sometimes what the questioner is really wondering is whether it makes sense to go on and his question is “Is life worth living?” He may actually be contemplating suicide. His predicament has to do with meaning if he is assuming that it makes sense to continue living only if (his) life has a suitable meaning, something which, at the moment, he can’t see it as having.

(7) Finally, the question of the meaning of life can be the question of how one should live in order to have a meaningful life, or, if such a life is impossible, then what the best way to live meaninglessly is.

The seven questions just distinguished may be, but need not be, discrete and self-contained. A given seeker may very well be interested in several of them at once and see them as intimately connected. For example, a person may be interested in his core or essence because he thinks that knowledge of that may reveal the goal or purpose of his life, a purpose that makes his life seem important and intelligible, and gives him a reason for going on, as well as insight into how he must live in order to have a meaningful life. It is commonly the case that several of the questions press themselves on the seeker all at the same time.

One or more of these questions were of concern to the philosophers discussed below. Some were concerned with nearly all of them. Distinct from all the above are second-order, analytic, conceptual questions of the sort that dominate current philosophical discussion of the issue in analytic circles. These questions are not so much about the meaning of life as about the meaning of “the meaning of life” and its component concepts (“meaning,” “life”), or related ones (“meaningfulness,” “meaninglessness,” “vanity,” “absurdity,” and so forth).

c. The Broader Historical Background

Although nineteenth century thinkers were the first in the West to put the question precisely in the form “What is the meaning of life?” concern with questions in what may be called “the meaning-of-life family,” that is, ultimate questions about life, the world, existence, and its purpose may be found, in the East and the West alike, almost as far back as we can trace human thought about anything. Thus Gilgamesh (c. 2000 B.C.E.) asked why he must die; the composers of The Rig Veda (c. 1200 B.C.E.) wondered where everything came from; Job (c. 500 B.C.E.) asked why he must suffer; the ancient Taoists (Laozi c. 500 B.C.E. and Zhuangzi c. 300 B.C.E.) asked what the origin or principle of everything is, and how one must live to be in accord with it; ancient Upanishadic seekers (500-300 B.C.E.) were much vexed with the nature of the true self and its end or goal; the Buddha (c. 500 B.C.E.), before he became the Buddha, sought an understanding of life that would enable one to overcome suffering; the author of The Bhagavad Gita (c. 200 B.C.E.) was concerned, as other Indian thinkers tended to be, with the identity and nature of the true self, and also with the question of how to live; the ancient Greeks of the classical period (c. 430-320 B.C.E.) talked about the goal or end of life and how to reach it; Epicurus (341-270 B.C.E.) followed suit and developed his own unique take on these matters; Qoheleth, the author of Ecclesiastes (c. 200 B.C.E.), was struck by the vanity or futility of everything and wondered how to deal with it; Greek and Roman Hellenistic philosophers (c. 300 B.C.E. – 250 C.E.)—Epicurean, Stoic, Cynic, Skeptic, and Neo-Platonist—wondered about the good and how to achieve it; Marcus Aurelius (121-180 C.E.) mused on his cosmic insignificance.

The Christian-dominated medieval period did not produce thinkers who asked in any radical way about the meaning of life, because everyone already had a perfectly good answer, the one provided by the Christian story. Still, even in medieval times, there was room for at least three questions in the meaning-of-life family. First, there was occasion for the questions when things ran counter to the Christian story, or to what one expected. Thus Boethius (480-525) was perplexed by the deep questions when, after a life of honor, piety, and power, he fell into disgrace, had everything stripped from him unaccountably and unjustly, and found himself faced with imprisonment that lead eventually to his execution. Second, though the great Christian philosopher-theologians thought they knew the meaning of life in outline, they still asked and answered questions about the details of the final or highest good of man. Thomas Aquinas (1224-1274), for example, who accepted with unblinking assurance the general answer supplied by Christianity, found himself wondering about the exact nature of the summum bonum (the highest good) and about how to square the Christian view of it with that of Aristotle. Third, other Christian believers, medieval ones as well as present-day ones with medieval outlooks, committed to an overall view of what is going on, may be vexed by the question of what God intends for them specifically and may worry about their “calling,” the particular purpose, role, or plan God has especially for them. Hence we find confirmed believers worried deeply about the question, “What is the meaning of my life?”

In any event, since the early modern period, there has been a resurgence of interest in fundamental meaning-of-life questions. Writers as diverse as Shakespeare (1564-1616), Pascal (1623-1662), Dr. Johnson (1709-84), Kant (1724-1804), and Hegel (1770-1831) have asked, in different forms, questions about life’s ultimate point, goal, or purpose, and they are just a few of the many religious, philosophical, and literary figures who have raised and (sometimes) answered ultimate questions in the meaning-of-life family prior to Schopenhauer’s work early in the nineteenth century. There have been philosophers too since Schopenhauer’s time who have addressed the big questions, but not explicitly in terms of “the meaning of life.” This article will confine itself largely to those philosophers who have explicitly put their concerns in those terms.

The standard explanation of the rise of questions about life’s meaning in the early modern period points to three or four distinct but related things: (1) the scientific revolution; (2) the Protestant Reformation; (3) voyages and travels of exploration and discovery, in which were encountered peoples with very different outlooks on the nature of the universe and the meaning of life; and (4), as a result of all of these, the evaporation of a widely held, firmly believed Christian conception of the nature of things.

2. Nineteenth Century Philosophers

Let us turn now to the story of what philosophers from Schopenhauer in the early 1800s to Ayer and Camus in the 1940s have had to say about the meaning of life.

a. Schopenhauer

The first Western philosopher to link the ideas of life and meaning, and to ask expressly “What is the meaning of life?” was the great German pessimist Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860). At least he was the first to ask the question and get it noticed by other philosophers. Schopenhauer, a contemporary of Carlyle, wrote in German, in which “the meaning of life” is “ der Sinn des Lebens .” Profoundly influencing the thought of both Nietzsche and Tolstoy, Schopenhauer’s work may be regarded as the springboard that launched modern Western philosophical inquiry into the problem of the meaning of life. Here is the passage in which Schopenhauer explicitly asked the question:

Since a man does not alter, and his moral character remains absolutely the same all through his life; since he must play out the part which he has received, without the least deviation from the character; since neither experience, nor philosophy, nor religion can effect any improvement in him, the question arises, What is the meaning of life at all? (1860b) [emphasis added]

The circumstances under which concern with the problem of the meaning of life were, in Schopenhauer’s case, not merely academic but real and personal. Well off financially, but struggling with personal misery and a sense of loneliness and isolation, he felt driven to find some understanding of himself and of the world around him that seemed so bleak and senseless.

Schopenhauer’s philosophy begins with a metaphysical structure he inherited from Kant and more or less simply decrees. There is a difference between the thing-in-itself and the phenomenal world of appearances. The thing-in-itself is the will to live, or, more simply, the will. It is the fundamental power and reality that underlies all things. The world we know and live in, with its stupendous abundance of things and forms, is merely the phenomena of the will, the objectification of it, its mirror, something not entirely real, or not real at all. (There is also a pure, will-less subject of knowledge whose metaphysical status is unclear: sometimes it seems to be in the very realm of the will, the realm of true reality, of things-in-themselves; at other times it seems to be something like the first creation and objectification of the will.)

The will itself just wills. It is pretty nasty, perhaps demonic. It is a blind striving, craving, and grasping, aiming at nothing in the end, except to go on willing and aggrandizing itself. It has in itself an inner contradiction, manifest in the constant struggle and strife between the billions of individual objectifications of itself in the phenomenal world. I am one such objectification; you are another. My true self, my inner essence, is the will; the same is true of you: my essence and yours are one and the same. When we fight (as we usually do), the will is engaged in a battle with itself.

The phenomenal world is an awful place. It is full of misery, pain, suffering. Little happiness is found anywhere. The twin poles of human life are pain (want, desire, stress) and boredom. Almost everyone lives a life that, from without, is meaningless and insignificant and, from within, dull and senseless.

But what is the meaning of life? The question is appropriate because life as we know it is something like Macbeth’s tale told by an idiot, a “farce.” If the question is about life’s inner essence, Schopenhauer’s answer is simply “the will-to-live.” The meaning of life is the will.

Another way of taking the question “What is the meaning of life?” is to construe it as a question about the goal, point, aim, end, or purpose of life. When Schopenhauer explicitly asks the question (in On Human Nature), it is this sense of it he appears to have in mind. His answer is depressing. The point or purpose of life is to suffer. We are being punished for the crime of being born, punished for who we are, namely, the nasty thoroughly egoistic will. The meaning of life in this sense, then, is to suffer, to be punished for our sin.

Schopenhauer suggests a number of ways of thinking about our phenomenal, experienced life. All of them are pretty bleak. He recommends that we look upon our life: as an unprofitable episode interrupting the blessed calm of nothingness; as on the whole a disappointment, nay, a cheat; as Hell, in which on the one hand men are the tormented souls and on the other the tormenting devils; as a place of atonement, a sort of penal colony; as some kind of mistake; and as a process of disillusionment. Any or all of these could be taken as answers to the question “What is the meaning of life?” (or to the question “What is life?”)

If we ask what we should do, how we can give our lives worth and meaning, Schopenhauer does have an answer. “Salvation” lies in the total denial of the will. Knowledge of the will and its horrific phenomena can and should function as a quieter of the will, bringing it to a state in which it stops willing and effectively abolishes itself. Thinking in this vein, a Schopenhauerian might say that the meaning of life is to deny, quiet, and eventually abolish the will to live that is essentially oneself.

One naturally wants to know whether this is not just suicide—whether the cessation of willing simply means that one passes into a state of nothingness. Schopenhauer’s answer is “No.” The state of the will-less individual after death seems to be nothing to us; but our present state would seem to be nothing to him. His state is wonderful and blessed, but what it is like is inconceivable to us.

In our current state, when one denies the will in herself, she does not literally commit suicide. Suicide doesn’t work because it is itself a powerful act of willing. Instead, she practices self-denial and asceticism, cultivates detachment, stops wanting and pursuing the things most people go for; and although there is still some struggle with the dying will in her, on the whole her life becomes full of peace and joy. The will is quieted and eventually abolishes itself in the individual. Very few people are capable of doing this heroic thing, Schopenhauer says, but he himself does not claim to be one of these people.

For all the darkness of his philosophy, the moral for all of us—even those of us who are not prepared to totally deny the will—which Schopenhauer derives in the end is very much in the Christian/Buddhist vein. We should not be competitive or grasping or villainous, but rather we should show compassion and kindness to everyone, since everyone is always having a bad day in this hell we are all living in, and what we all need above all are love, compassion, help, and consideration. The fundamental principle of morality, which you should follow, is: Don’t hurt anyone; help everyone you can. Following this principle, one can achieve, short of complete denial of the will, a kind of half-way salvation.

Another of Schopenhauer’s points about meaning in life should be mentioned. It is that the meaningfulness of one’s life depends not on one’s outer circumstances but rather on the way one looks at life. People look at life differently, and so the meaningfulness of her life varies considerably from person to person. To one person life is barren, dull, and superficial; to another rich, interesting, and full of meaning.

b. Kierkegaard

A major nineteenth century European philosopher who continued the tradition of thought on the meaning of life was the Danish philosopher Soren Kierkegaard (1813-1855). Kierkegaard was not an academic. The sources of his interest in problems of meaning seem to have been his not having to work for a living, his personal demons, his Nordic gloom, his congenital tendencies toward guilt, depression, anxiety, and dread, his awareness of increasing doubt all around him of the teachings of his inherited Christianity, and his agonizing failure to live up to his own Christian ideals, primarily because of his embodiment and its concomitant proclivity for the things of the flesh, especially sensuousness and sex. Out of all that emerged what appears to be a severe case of self-loathing, which in turn prompted serious inquiry into the meaning of (his) life.

It is difficult to determine what Kierkegaard’s own views were on just about everything because he constantly used humor, satire, paradox, and irony, and even more because he spoke in different voices and wrote from different perspectives under different pseudonyms.

Nonetheless, the standard view is that Kierkegaard was fundamentally a Christian. He claimed that one’s life can be meaningful and worth living only if one believes genuinely and passionately in the Christian God.

And then there is the leap. Christian belief goes beyond rational evidence, and even conflicts with it. One must make a leap from knowledge to Christian faith—the only thing in which one can find true meaning—a leap over the confines of common sense and reason. One is to accept Christian faith even if (or just because?) it is absurd. For it is the only adequate source of the kind of meaning a human being has to have to keep on going with a sense that life is worthwhile.

Another way to describe Kierkegaard’s overall philosophy is to characterize it in terms of his three stages or levels of life. One should make an ascent from the lowest stage, the aesthetic (sensuous, even sensual), through the higher ethical stage, and on to the highest stage of all, the religious, which somehow baptizes and incorporates the two lower stages into itself. Only one who has reached the religious stage can have a truly meaningful life and thus a life worth living.

Whatever Kierkegaard’s own view was, we can make the following observations about things Kierkegaard (or one or other of his pseudonymous authors) said about the meaning of life.

(1) One thing is that life can seem meaningless. In the early work, Either/Or (1843), we find this passage: “How empty and meaningless life is.” Elsewhere in Either/Or we get similar thoughts and questions, for instance, “What, if anything, is the meaning of this life?” and “My life is utterly meaningless.” Perhaps, though, the idea is that, though life is often meaningless, it need not be so, and, when it is, it is because of some kind of failure of the liver (of the life, not the organ).

(2) A second interesting idea in Kierkegaard is that meaning has something to do with unity. In a meaningful life all the diverse aspects of it come together to form some kind of coherent whole. One pursues some one goal, to which everything in one’s life is subordinated.

(3) A third point, an important one, is that, though meaning is a good thing, it is possible for there to be too much meaning in one’s life, or in its parts. Kierkegaard observes:

No part of life ought to have so much meaning for a person that he cannot forget it any moment he wants to; on the other hand, every single part of life ought to have so much meaning for a person that he can remember it at any moment. ( Either/Or )

To have one’s life full of meaning to the brim, to regard life and everything one does in it as infinitely significant, brings with it so much pressure and stress that one’s life becomes unbearable.

To me [says Kierkegaard] it seems . . . that to be known in time by God makes life enormously strenuous. Everywhere where he is present each half hour is of infinite importance. Yet to live like that for sixty years is unsupportable. It is difficult enough putting up even with the three years’ hard study for an examination, and those are still not as strenuous as half an hour like this. ( Concluding Unscientific Postscript )

(4) A fourth idea about meaning in Kierkegaard is the idea that one can give one’s life meaning, or that one can acquire meaning in life, by doing something like devoting oneself to something. Of Antigone he says, “her life acquires meaning for her in its devotion to showing him [her father, after his death] the last honors daily, almost hourly, by her unbroken silence.” ( Either/Or )

(5) Meaning does not come from abstract, objective knowledge of any kind, whether philosophical, or scientific, or historical, or even theological. It comes from some kind of faith, a faith that is passionately acquired and lived daily.

(6) One twentieth century approach to the problem of the meaning of life is to see, accept, and bask more or less happily in the absurdity of life. Kierkegaard anticipated this approach prophetically in his characterization of the “humorist.” Kierkegaard writes: “Weary of time and its endless succession, the humorist runs away and finds humorous relief in stating the absurd.” ( Concluding Unscientific Postscript )

(7) Kierkegaard’s humorist also at one point expresses a view which is surprisingly rare, namely, the view that one’s life may have a meaning, but one doesn’t know what it is. Kierkegaard writes: “[L]et a humorist say what he has in mind and he will speak, for example, as follows: What is the meaning of life? Yes, good question. How should I know?” ( Concluding Unscientific Postscript )

(8) Although Kierkegaard himself was a Christian who viewed meaning as ultimately grounded in religious faith, in one’s personal relation to a supernatural God, yet, paradoxically perhaps, and certainly in an admirable spirit of non-exclusivity, he said:

It is possible both to enjoy life and to give it meaning and substance outside Christianity, just as the most famous poets and artists, the most eminent of thinkers, even men of piety, have lived outside Christianity ( Concluding Unscientific Postscript ).

(9) One finds in Kierkegaard the idea that life has meaning only insofar as it is related in some way to the Infinite. Nothing finite can supply the meaning of life.

On the whole, if for no other reason, Kierkegaard’s work is valuable because of its suggestiveness. Under one pseudonym or another, Kierkegaard made many important points which were taken up, or unfortunately overlooked, by subsequent philosophers concerned with the meaning of life.

c. Nietzsche

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) cut his philosophical teeth on Schopenhauer and devoted himself in his later works—from 1883 up to the onset of insanity in January 1889—to struggle with, among other things, the meaning of life.

Nietzsche’s grand project was the revaluation of all values. Part of this project was that of giving to life a new meaning. Nietzsche’s interest in the matter was not merely academic. Coming up with new values and giving life a new meaning was a project that involved a total transformation of Nietzsche’s own self, early versions of which he became dissatisfied with. One thing Nietzsche wanted to do was to produce an affirmative philosophy of life to replace Schopenhauer’s pessimistic, life-denying philosophy.

Nietzsche rejected Schopenhauer’s picture of life as suffering, or punishment for one’s sin, together with its ethic of compassion toward the poor and the sick. Such a picture belonged to a weak, sick, decadent, nay-saying mode of being in decline. Nietzsche himself wanted to produce a positive, healthy, life-affirming philosophy, one suitable for life in the ascendant.

Sometimes, particularly early in his writings, Nietzsche seemed to think some end or other is required to make things meaningful. At times, both early and late, Nietzsche spoke as though the very concept of the meaning of something is the concept of its end, object, or goal.

In other places, however, Nietzsche spoke as if the meaning of life lies in freedom from , not in the achievement of, ends. Perhaps this should be construed as the rejection of given ends to be discovered, not in the rejection of all ends, particularly those one creates. Moritz Schlick—whose thought we will consider in more detail later—claimed that Nietzsche saw that life has no meaning so long as it stands wholly under the domination of purposes. In Nietzsche’s Zarathustra, “Sir Hazard,” expressing Nietzsche’s own considered view, says, “I have saved them from the slavery of ends.” (Klemke, 3 rd ed., 63).

Nietzsche sometimes spoke as if life, before he came into it, or before he revaluated all values, had no meaning: “Sombre is human life, and as yet without meaning: a buffoon may be fateful to it” ( Thus Spake Zarathustra, 1883). There is no meaning “out there” to be discovered, no meaning in the essences of things, apart from human will, desire, perspective. In fact, apart from perspective, there is no world out there at all, no “thing-in-itself,” no “facts-in-themselves.” But a psychologically strong person can do without things in themselves and meaning (already there) to be discovered in them. That is because he can organize a small part of the world himself and thus create meaning. In The Will to Power, Nietzsche speaks of “the creative strength to create meaning,” and he says:

It is a measure of the degree of strength of will to what extent one can do without meaning in things, to what extent one can endure to live in a meaningless world because one organizes a small portion of it oneself. ( The Will to Power )

Whatever the meaning of life is, or is to be, it is terrestrial, not celestial. Meaning must not be placed in some fabricated “true world” but in this very earth in which we live and have our being. And the meaning of life is to be created, not discovered.

Still, somehow, man is not the meaning and measure of all things, though he has posited himself as such.

All the values by means of which we have tried so far to render the world estimable for ourselves and which then proved inapplicable and therefore devaluated the world—all these values are, psychologically considered, the results of certain perspectives of utility, designed to maintain and increase human constructs of domination—and they have been falsely projected into the essence of things. What we find here is still the hyperbolic naiveté of man: positing himself as the meaning and measure of the value of things. ( The Will to Power )