A Summary and Analysis of Martin Luther King’s ‘I Have a Dream’ Speech

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

‘I Have a Dream’ is one of the greatest speeches in American history. Delivered by Martin Luther King, Jr. (1929-68) in Washington D.C. in 1963, the speech is a powerful rallying cry for racial equality and for a fairer and equal world in which African Americans will be as free as white Americans.

If you’ve ever stayed up till the small hours working on a presentation you’re due to give the next day, tearing your hair out as you try to find the right words, you can take solace in the fact that as great an orator as Martin Luther King did the same with one of the most memorable speeches ever delivered.

He reportedly stayed up until 4am the night before he was due to give his ‘I Have a Dream’, writing it out in longhand. You can read the speech in full here .

‘I Have a Dream’: background

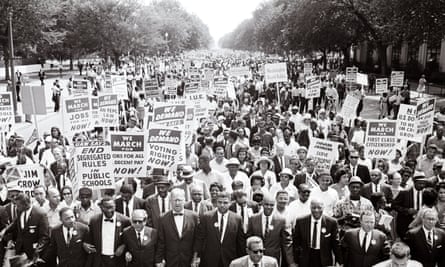

The occasion for King’s speech was the march on Washington , which saw some 210,000 African American men, women, and children gather at the Washington Monument in August 1963, before marching to the Lincoln Memorial.

They were marching for several reasons, including jobs (many of them were out of work), but the main reason was freedom: King and many other Civil Rights leaders sought to remove segregation of black and white Americans and to ensure black Americans were treated the same as white Americans.

1963 was the centenary of the Emancipation Proclamation , in which then US President Abraham Lincoln (1809-65) had freed the African slaves in the United States in 1863. But a century on from the abolition of slavery, King points out, black Americans still are not free in many respects.

‘I Have a Dream’: summary

King begins his speech by reminding his audience that it’s a century, or ‘five score years’, since that ‘great American’ Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This ensured the freedom of the African slaves, but Black Americans are still not free, King points out, because of racial segregation and discrimination.

America is a wealthy country, and yet many Black Americans live in poverty. It is as if the Black American is an exile in his own land. King likens the gathering in Washington to cashing a cheque: in other words, claiming money that is due to be paid.

Next, King praises the ‘magnificent words’ of the US Constitution and the Declaration of Independence . King compares these documents to a promissory note, because they contain the promise that all men, including Black men, will be guaranteed what the Declaration of Independence calls ‘inalienable rights’: namely, ‘life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness’.

King asserts that America in the 1960s has ‘defaulted’ on this promissory note: in other words, it has refused to pay up. King calls it a ‘sacred obligation’, but America as a nation is like someone who has written someone else a cheque that has bounced and the money owed remains to be paid. But it is not because the money isn’t there: America, being a land of opportunity, has enough ‘funds’ to ensure everyone is prosperous enough.

King urges America to rise out of the ‘valley’ of segregation to the ‘sunlit path of racial justice’. He uses the word ‘brotherhood’ to refer to all Americans, since all men and women are God’s children. He also repeatedly emphasises the urgency of the moment. This is not some brief moment of anger but a necessary new start for America. However, King cautions his audience not to give way to bitterness and hatred, but to fight for justice in the right manner, with dignity and discipline.

Physical violence and militancy are to be avoided. King recognises that many white Americans who are also poor and marginalised feel a kinship with the Civil Rights movement, so all Americans should join together in the cause. Police brutality against Black Americans must be eradicated, as must racial discrimination in hotels and restaurants. States which forbid Black Americans from voting must change their laws.

Martin Luther King then comes to the most famous part of his speech, in which he uses the phrase ‘I have a dream’ to begin successive sentences (a rhetorical device known as anaphora ). King outlines the form that his dream, or ambition or wish for a better America, takes.

His dream, he tells his audience, is ‘deeply rooted’ in the American Dream: that notion that anybody, regardless of their background, can become prosperous and successful in the United States. King once again reminds his listeners of the opening words of the Declaration of Independence: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.’

In his dream of a better future, King sees the descendants of former Black slaves and the descendants of former slave owners united, sitting and eating together. He has a dream that one day his children will live in a country where they are judged not by the colour of their skin but by the content of their character.

Even in Mississippi and Alabama, states which are riven by racial injustice and hatred, people of all races will live together in harmony. King then broadens his dream out into ‘our hope’: a collective aspiration and endeavour. King then quotes the patriotic American song ‘ My Country, ’Tis of Thee ’, which describes America as a ‘sweet land of liberty’.

King uses anaphora again, repeating the phrase ‘let freedom ring’ several times in succession to suggest how jubilant America will be on the day that such freedoms are ensured. And when this happens, Americans will be able to join together and be closer to the day when they can sing a traditional African-American hymn : ‘Free at last. Free at last. Thank God almighty, we are free at last.’

‘I Have a Dream’: analysis

Although Martin Luther King’s speech has become known by the repeated four-word phrase ‘I Have a Dream’, which emphasises the personal nature of his vision, his speech is actually about a collective dream for a better and more equal America which is not only shared by many Black Americans but by anyone who identifies with their fight against racial injustice, segregation, and discrimination.

Nevertheless, in working from ‘I have a dream’ to a different four-word phrase, ‘this is our hope’. The shift is natural and yet it is a rhetorical masterstroke, since the vision of a better nation which King has set out as a very personal, sincere dream is thus telescoped into a universal and collective struggle for freedom.

What’s more, in moving from ‘dream’ to a different noun, ‘hope’, King suggests that what might be dismissed as an idealistic ambition is actually something that is both possible and achievable. No sooner has the dream gathered momentum than it becomes a more concrete ‘hope’.

In his ‘I Have a Dream’ speech, King was doing more than alluding to Abraham Lincoln’s signing of the Emancipation Proclamation one hundred years earlier. The opening words to his speech, ‘Five score years ago’, allude to a specific speech Lincoln himself had made a century before: the Gettysburg Address .

In that speech, delivered at the Soldiers’ National Cemetery (now known as Gettysburg National Cemetery) in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania in November 1863, Lincoln had urged his listeners to continue in the fight for freedom, envisioning the day when all Americans – including Black slaves – would be free. His speech famously begins with the words: ‘Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.’

‘Four score and seven years’ is eighty-seven years, which takes us back from 1863 to 1776, the year of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. So, Martin Luther King’s allusion to the words of Lincoln’s historic speech do two things: they call back to Lincoln’s speech but also, by extension, to the founding of the United States almost two centuries before. Although Lincoln and the American Civil War represented progress in the cause to make all Americans free regardless of their ethnicity, King makes it clear in ‘I Have a Dream’ that there is still some way to go.

In the last analysis, King’s speech is a rhetorically clever and emotionally powerful call to use non-violent protest to oppose racial injustice, segregation, and discrimination, but also to ensure that all Americans are lifted out of poverty and degradation.

But most of all, King emphasises the collective endeavour that is necessary to bring about the world he wants his children to live in: the togetherness, the linking of hands, which is essential to make the dream a reality.

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Read Martin Luther King Jr.'s 'I Have a Dream' speech in its entirety

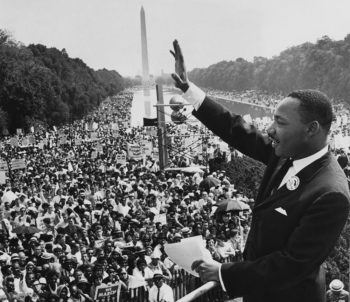

Civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. addresses the crowd at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., where he gave his "I Have a Dream" speech on Aug. 28, 1963, as part of the March on Washington. AFP via Getty Images hide caption

Civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. addresses the crowd at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., where he gave his "I Have a Dream" speech on Aug. 28, 1963, as part of the March on Washington.

Monday marks Martin Luther King, Jr. Day. Below is a transcript of his celebrated "I Have a Dream" speech, delivered on Aug. 28, 1963, on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. NPR's Talk of the Nation aired the speech in 2010 — listen to that broadcast at the audio link above.

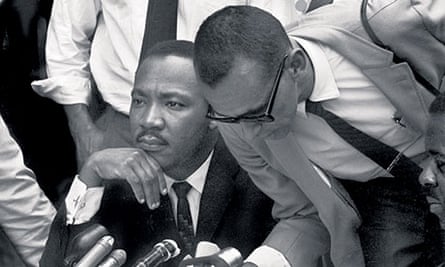

Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights leaders gather before a rally at the Lincoln Memorial on Aug. 28, 1963, in Washington. National Archives/Hulton Archive via Getty Images hide caption

Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.: Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity.

But 100 years later, the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself in exile in his own land. And so we've come here today to dramatize a shameful condition. In a sense we've come to our nation's capital to cash a check.

Code Switch

The power of martin luther king jr.'s anger.

When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men — yes, Black men as well as white men — would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked insufficient funds.

But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt.

Martin Luther King is not your mascot

We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. And so we've come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice.

We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now. This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism.

Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy. Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice. Now is the time to lift our nation from the quick sands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood. Now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God's children.

Civil rights protesters march from the Washington Monument to the Lincoln Memorial for the March on Washington on Aug. 28, 1963. Kurt Severin/Three Lions/Hulton Archive/Getty Images hide caption

It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment. This sweltering summer of the Negro's legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality. 1963 is not an end, but a beginning. Those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual.

There will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights. The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.

But there is something that I must say to my people who stand on the warm threshold which leads into the palace of justice. In the process of gaining our rightful place, we must not be guilty of wrongful deeds. Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred.

Throughline

Bayard rustin: the man behind the march on washington (2021).

We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline. We must not allow our creative protest to degenerate into physical violence. Again and again, we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force. The marvelous new militancy which has engulfed the Negro community must not lead us to a distrust of all white people, for many of our white brothers, as evidenced by their presence here today, have come to realize that their destiny is tied up with our destiny.

And they have come to realize that their freedom is inextricably bound to our freedom. We cannot walk alone. And as we walk, we must make the pledge that we shall always march ahead. We cannot turn back.

There are those who are asking the devotees of civil rights, when will you be satisfied? We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality. We can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities.

We cannot be satisfied as long as the Negro's basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one. We can never be satisfied as long as our children are stripped of their selfhood and robbed of their dignity by signs stating: for whites only.

We cannot be satisfied as long as a Negro in Mississippi cannot vote and a Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote.

No, no, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream.

How The Voting Rights Act Came To Be And How It's Changed

I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulations. Some of you have come fresh from narrow jail cells. Some of you have come from areas where your quest for freedom left you battered by the storms of persecution and staggered by the winds of police brutality. You have been the veterans of creative suffering. Continue to work with the faith that unearned suffering is redemptive. Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to South Carolina, go back to Georgia, go back to Louisiana, go back to the slums and ghettos of our Northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed.

Let us not wallow in the valley of despair, I say to you today, my friends.

So even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.

People clap and sing along to a freedom song between speeches at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963. Express Newspapers via Getty Images hide caption

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today.

I have a dream that one day down in Alabama with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of interposition and nullification, one day right down in Alabama little Black boys and Black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers. I have a dream today.

I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight, and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together.

Nikole Hannah-Jones on the power of collective memory

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

This is our hope. This is the faith that I go back to the South with. With this faith, we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day.

This will be the day when all of God's children will be able to sing with new meaning: My country, 'tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing. Land where my fathers died, land of the pilgrims' pride, from every mountainside, let freedom ring.

And if America is to be a great nation, this must become true. And so let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire. Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York. Let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania. Let freedom ring from the snowcapped Rockies of Colorado. Let freedom ring from the curvaceous slopes of California. But not only that, let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia. Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee. Let freedom ring from every hill and molehill of Mississippi. From every mountainside, let freedom ring.

And when this happens, and when we allow freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God's children, Black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual: Free at last. Free at last. Thank God almighty, we are free at last.

Correction Jan. 15, 2024

A previous version of this transcript included the line, "We have also come to his hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now." The correct wording is "We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now."

Why “I Have A Dream” Remains One Of History’s Greatest Speeches

Monday will mark the holiday in honor of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Texas A&M University Professor of Communication Leroy Dorsey is reflecting on King’s celebrated “I Have a Dream” speech, one which he said is a masterful use of rhetorical traditions.

King delivered the famous speech as he stood before a crowd of 250,000 people in front of the Lincoln Memorial on Aug. 28, 1963 during the “March on Washington.” The speech was televised live to an audience of millions.

“He was not just speaking to African Americans, but to all Americans” ~ Leroy Dorsey

Dorsey , associate dean for inclusive excellence and strategic initiatives in the College of Liberal Arts, said one of the reasons the speech stands above all of King’s other speeches – and nearly every other speech ever written – is because its themes are timeless. “It addresses issues that American culture has faced from the beginning of its existence and still faces today: discrimination, broken promises, and the need to believe that things will be better,” he said.

Powerful Use of Rhetorical Devices

Dorsey said the speech is also notable for its use of several rhetorical traditions, namely the Jeremiad, metaphor-use and repetition.

The Jeremiad is a form of early American sermon that narratively moved audiences from recognizing the moral standard set in its past to a damning critique of current events to the need to embrace higher virtues.

“King does that with his invocation of several ‘holy’ American documents such as the Emancipation Proclamation and Declaration of Independence as the markers of what America is supposed to be,” Dorsey said. “Then he moves to the broken promises in the form of injustice and violence. And he then moves to a realization that people need to look to one another’s character and not their skin color for true progress to be made.”

Second, King’s use of metaphors explains U.S. history in a way that is easy to understand, Dorsey said.

“Metaphors can be used to connect an unknown or confusing idea to a known idea for the audience to better understand,” he said. For example, referring to founding U.S. documents as “bad checks” transformed what could have been a complex political treatise into the simpler ideas that the government had broken promises to the American people and that this was not consistent with the promise of equal rights.

The third rhetorical device found in the speech, repetition, is used while juxtaposing contrasting ideas, setting up a rhythm and cadence that keeps the audience engaged and thoughtful, Dorsey said.

“I have a dream” is repeated while contrasting “sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners” and “judged by the content of their character” instead of “judged by the color of their skin.” The device was used also with “let freedom ring” which juxtaposes states that were culturally polar opposites – Colorado, California and New York vs. Georgia, Tennessee and Mississippi.

Words That Moved A Movement

The March on Washington and King’s speech are widely considered turning points in the Civil Rights Movement, shifting the demand and demonstrations for racial equality that had mostly occurred in the South to a national stage.

Dorsey said the speech advanced and solidified the movement because “it became the perfect response to a turbulent moment as it tried to address past hurts, current indifference and potential violence, acting as a pivot point between the Kennedy administration’s slow response and the urgent response of the ‘marvelous new militancy’ [those fighting against racism].”

What made King such an outstanding orator were the communication skills he used to stir audience passion, Dorsey said. “When you watch the speech, halfway through he stops reading and becomes a pastor, urging his flock to do the right thing,” he said. “The cadence, power and call to the better nature of his audience reminds you of a religious service.”

Lessons For Today

Dorsey said the best leaders are those who can inspire all without dismissing some, and that King in his famous address did just that.

“He was not just speaking to African Americans in that speech, but to all Americans, because he understood that the country would more easily rise together when it worked together,” he said.

“I Have a Dream” remains relevant today “because for as many strides that have been made, we’re still dealing with the elements of a ‘bad check’ – voter suppression, instances of violence against people of color without real redress, etc.,” Dorsey said. “Remembering what King was trying to do then can provide us insight into what we need to consider now.”

Additionally, King understood that persuasion doesn’t move from A to Z in one fell swoop, but it moves methodically from A to B, B to C, etc., Dorsey said. “In the line ‘I have a dream that one day ,’ he recognized that things are not going to get better overnight, but such sentiment is needed to help people stay committed day-to-day until the country can honestly say, ‘free at last!'”

Media contact: Lesley Henton, 979-845-5591, [email protected].

Related Stories

MSC SCOLA Illuminates Path To Success

The three-day Student Conference on Latinx Affairs offers opportunities for learning, leadership and growth.

Asian Pacific Islander Desi American Heritage Month Events

A variety of campus organizations are inviting the Aggie community for unique cultural experiences.

MSC SCOLA 2023: ‘Focusing On The Present To Ensure Our Future’

The MSC Student Conference On Latinx Affairs (SCOLA) will challenge student leaders to focus on the influence of the Latinx community.

Recent Stories

US News & World Report Releases 2024 Rankings Of America’s Best Grad Schools

In its Best Graduate Schools ranking, the publication placed 10 of Texas A&M’s graduate programs in the Top 20; among those, six are Top 10.

Texas A&M Names Head Yell Leader

Jake Carter, a junior management student, will guide the 2024-25 Yell Leaders.

Texas A&M, University Of Colorado Research Collaboration Wins Federal Grant To Help Turn Off ‘Breast Cancer Switch’

The five-year study aims to identify more effective treatments.

Subscribe to the Texas A&M Today newsletter for the latest news and stories every week.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Critic’s Notebook

The Lasting Power of Dr. King’s Dream Speech

By Michiko Kakutani

- Aug. 27, 2013

It was late in the day and hot, and after a long march and an afternoon of speeches about federal legislation, unemployment and racial and social justice, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. finally stepped to the lectern, in front of the Lincoln Memorial, to address the crowd of 250,000 gathered on the National Mall.

He began slowly, with magisterial gravity, talking about what it was to be black in America in 1963 and the “shameful condition” of race relations a hundred years after the Emancipation Proclamation. Unlike many of the day’s previous speakers, he did not talk about particular bills before Congress or the marchers’ demands. Instead, he situated the civil rights movement within the broader landscape of history — time past, present and future — and within the timeless vistas of Scripture.

Dr. King was about halfway through his prepared speech when Mahalia Jackson — who earlier that day had delivered a stirring rendition of the spiritual “I Been ’Buked and I Been Scorned” — shouted out to him from the speakers’ stand: “Tell ’em about the ‘Dream,’ Martin, tell ’em about the ‘Dream’!” She was referring to a riff he had delivered on earlier occasions, and Dr. King pushed the text of his remarks to the side and began an extraordinary improvisation on the dream theme that would become one of the most recognizable refrains in the world.

With his improvised riff, Dr. King took a leap into history, jumping from prose to poetry, from the podium to the pulpit. His voice arced into an emotional crescendo as he turned from a sobering assessment of current social injustices to a radiant vision of hope — of what America could be. “I have a dream,” he declared, “my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today!”

Many in the crowd that afternoon, 50 years ago on Wednesday, had taken buses and trains from around the country. Many wore hats and their Sunday best — “People then,” the civil rights leader John Lewis would recall, “when they went out for a protest, they dressed up” — and the Red Cross was passing out ice cubes to help alleviate the sweltering August heat. But if people were tired after a long day, they were absolutely electrified by Dr. King. There was reverent silence when he began speaking, and when he started to talk about his dream, they called out, “Amen,” and, “Preach, Dr. King, preach,” offering, in the words of his adviser Clarence B. Jones, “every version of the encouragements you would hear in a Baptist church multiplied by tens of thousands.”

You could feel “the passion of the people flowing up to him,” James Baldwin, a skeptic of that day’s March on Washington, later wrote, and in that moment, “it almost seemed that we stood on a height, and could see our inheritance; perhaps we could make the kingdom real.”

Dr. King’s speech was not only the heart and emotional cornerstone of the March on Washington, but also a testament to the transformative powers of one man and the magic of his words. Fifty years later, it is a speech that can still move people to tears. Fifty years later, its most famous lines are recited by schoolchildren and sampled by musicians. Fifty years later, the four words “I have a dream” have become shorthand for Dr. King’s commitment to freedom, social justice and nonviolence, inspiring activists from Tiananmen Square to Soweto, Eastern Europe to the West Bank.

Why does Dr. King’s “Dream” speech exert such a potent hold on people around the world and across the generations? Part of its resonance resides in Dr. King’s moral imagination. Part of it resides in his masterly oratory and gift for connecting with his audience — be they on the Mall that day in the sun or watching the speech on television or, decades later, viewing it online. And part of it resides in his ability, developed over a lifetime, to convey the urgency of his arguments through language richly layered with biblical and historical meanings.

The son, grandson and great-grandson of Baptist ministers, Dr. King was comfortable with the black church’s oral tradition, and he knew how to read his audience and react to it; he would often work jazzlike improvisations around favorite sermonic riffs — like the “dream” sequence — cutting and pasting his own words and those of others. At the same time, the sonorous cadences and ringing, metaphor-rich language of the King James Bible came instinctively to him. Quotations from the Bible, along with its vivid imagery, suffused his writings, and he used them to put the sufferings of African-Americans in the context of Scripture — to give black audience members encouragement and hope, and white ones a visceral sense of identification.

In his “Dream” speech, Dr. King alludes to a famous passage from Galatians, when he speaks of “that day when all of God’s children — black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics — will be able to join hands.” As he did in many of his sermons, he also drew parallels between “the Negro” still an “exile in his own land” and the plight of the Israelites in Exodus, who, with God on their side, found deliverance from hardship and oppression, escaping slavery in Egypt to journey toward the Promised Land.

The entire March on Washington speech reverberates with biblical rhythms and parallels, and bristles with a panoply of references to other historical and literary texts that would have resonated with his listeners. In addition to allusions to the prophets Isaiah (“I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, every hill and mountain shall be made low”) and Amos (“We will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream”), there are echoes of the Declaration of Independence (“the unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness”); Shakespeare (“this sweltering summer of the Negro’s legitimate discontent”); and popular songs like Woody Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land” (“Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York,” “Let freedom ring from the curvaceous slopes of California”).

Such references added amplification and depth of field to the speech, much the way T. S. Eliot’s myriad allusions in “The Waste Land” add layered meaning to that poem. Dr. King, who had a doctorate in theology and once contemplated a career in academia, was shaped by both his childhood in his father’s church and his later studies of disparate thinkers like Reinhold Niebuhr, Gandhi and Hegel. Along the way, he developed a gift for synthesizing assorted ideas and motifs and making them his own — a gift that enabled him to address many different audiences at once, while making ideas that some might find radical somehow familiar and accessible. It was a gift that in some ways mirrored his abilities as the leader of the civil rights movement, tasked with holding together often contentious factions (from more militant figures like Stokely Carmichael to more conservative ones like Roy Wilkins), while finding a way to balance the concerns of grass-roots activists with the need to forge a working alliance with the federal government.

At the same time, Dr. King was also able to nestle his arguments within a historical continuum, lending them the authority of tradition and the weight of association. For some, in his audience, the articulation of his dream for America would have evoked conscious or unconscious memories of Langston Hughes’s call in a 1935 poem to “let America be the dream the dreamers dreamed” and W. E. B. Du Bois’s description of the “wonderful America, which the founding fathers dreamed.” His final lines in the March on Washington speech come from a Negro spiritual reminding listeners of slaves’ sustaining faith in the possibility of liberation: “Free at last, free at last; thank God Almighty, we are free at last.”

For those less familiar with African-American music and literature, there were allusions with immediate, patriotic connotations. Much the way Lincoln redefined the founders’ vision of America in his Gettysburg Address by invoking the Declaration of Independence, so Dr. King in his “Dream” speech makes references to both the Gettysburg Address and the Declaration of Independence. These deliberate echoes helped universalize the moral underpinnings of the civil rights movement and emphasized that its goals were only as revolutionary as the founding fathers’ original vision of the United States. Dr. King’s dream for America’s “citizens of color” was no more, no less than the American Dream of a country where “all men are created equal.”

As for Dr. King’s quotation of “My Country, ’Tis of Thee” — an almost de facto national anthem, familiar even to children — it underscored civil rights workers’ patriotic belief in the project of reinventing America. For Dr. King, it might have elicited personal memories, too. The night his home was bombed during the bus boycott in Montgomery, Ala., endangering the lives of his wife, Coretta, and their infant daughter, he calmed the crowd gathered in front of their house, saying, “I want you to love our enemies.” Some of his supporters reportedly broke into song, including hymns and “My Country, ’Tis of Thee.”

The March on Washington and Dr. King’s “Dream” speech would play an important role in helping pass the 1964 Civil Rights Act, and the pivotal Selma to Montgomery march that he led in 1965 would provide momentum for the passage later that year of the Voting Rights Act. Though Dr. King received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964 , his exhausting schedule (he had been giving hundreds of speeches a year) and his frustration with schisms in the civil rights movement and increasing violence in the country led to growing weariness and depression before his assassination in 1968.

The knowledge that Dr. King gave his life to the cause lends an added poignancy to the experience of hearing his speeches today. And so does being reminded now — in the second term of Barack Obama’s presidency — of the dire state of race relations in the early 1960s, when towns in the South still had separate schools, restaurants, hotels and bathrooms for blacks and whites, and discrimination in housing and employment was prevalent across the country. Only two and a half months before the “Dream” speech, Gov. George Wallace had stood in a doorway at the University of Alabama in an attempt to block two black students from trying to register; the next day the civil rights activist Medgar Evers was assassinated in front of his home in Jackson, Miss.

President Obama, who once wrote about his mother’s coming home “with books on the civil rights movement, the recordings of Mahalia Jackson, the speeches of Dr. King,” has described the leaders of the movement as “giants whose shoulders we stand on.” Some of his own speeches owe a clear debt to Dr. King’s ideas and words.

In his 2004 Democratic National Convention keynote address, which brought him to national attention, Mr. Obama channeled Dr. King’s vision of hope, speaking of coming “together as one American family.” In his 2008 speech about race, he talked, much as Dr. King had, of continuing “on the path of a more perfect union.” And in his 2007 speech commemorating the 1965 Selma march, he echoed Dr. King’s remarks about Exodus, describing Dr. King and the other civil rights leaders as members of the Moses generation who “pointed the way” and “took us 90 percent of the way there.” He and his contemporaries were their heirs, Mr. Obama said — they were members of the Joshua generation with the responsibility of finishing “the journey Moses had begun.”

Dr. King knew it would not be easy to “transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood” — difficulties that persist today with new debates over voter registration laws and the Trayvon Martin shooting. Dr. King probably did not foresee a black president celebrating the 50th anniversary of his speech in front of the Lincoln Memorial, and surely did not foresee a monument to himself just a short walk away. But he did dream of a future in which the country embarked on “the sunlit path of racial justice,” and he foresaw, with bittersweet prescience, that 1963, as he put it, was “not an end, but a beginning.”

Follow Michiko Kakutani on Twitter: @michikokakutani

"I Have a Dream"

August 28, 1963

Martin Luther King’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech, delivered at the 28 August 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom , synthesized portions of his previous sermons and speeches, with selected statements by other prominent public figures.

King had been drawing on material he used in the “I Have a Dream” speech in his other speeches and sermons for many years. The finale of King’s April 1957 address, “A Realistic Look at the Question of Progress in the Area of Race Relations,” envisioned a “new world,” quoted the song “My Country ’Tis of Thee,” and proclaimed that he had heard “a powerful orator say not so long ago, that … Freedom must ring from every mountain side…. Yes, let it ring from the snow-capped Rockies of Colorado…. Let it ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia. Let it ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee. Let it ring from every mountain and hill of Alabama. From every mountain side, let freedom ring” ( Papers 4:178–179 ).

In King’s 1959 sermon “Unfulfilled Hopes,” he describes the life of the apostle Paul as one of “unfulfilled hopes and shattered dreams” ( Papers 6:360 ). He notes that suffering as intense as Paul’s “might make you stronger and bring you closer to the Almighty God,” alluding to a concept he later summarized in “I Have a Dream”: “unearned suffering is redemptive” ( Papers 6:366 ; King, “I Have a Dream,” 84).

In September 1960, King began giving speeches referring directly to the American Dream. In a speech given that month at a conference of the North Carolina branches of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People , King referred to the unexecuted clauses of the preamble to the U.S. Constitution and spoke of America as “a dream yet unfulfilled” ( Papers 5:508 ). He advised the crowd that “we must be sure that our struggle is conducted on the highest level of dignity and discipline” and reminded them not to “drink the poisonous wine of hate,” but to use the “way of nonviolence” when taking “direct action” against oppression ( Papers 5:510 ).

King continued to give versions of this speech throughout 1961 and 1962, then calling it “The American Dream.” Two months before the March on Washington, King stood before a throng of 150,000 people at Cobo Hall in Detroit to expound upon making “the American Dream a reality” (King, Address at Freedom Rally, 70). King repeatedly exclaimed, “I have a dream this afternoon” (King, Address at Freedom Rally, 71). He articulated the words of the prophets Amos and Isaiah, declaring that “justice will roll down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream,” for “every valley shall be exalted, and every hill and mountain shall be made low” (King, Address at Freedom Rally, 72). As he had done numerous times in the previous two years, King concluded his message imagining the day “when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing with the Negroes in the spiritual of old: Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!” (King, Address at Freedom Rally , 73).

As King and his advisors prepared his speech for the conclusion of the 1963 march, he solicited suggestions for the text. Clarence Jones offered a metaphor for the unfulfilled promise of constitutional rights for African Americans, which King incorporated into the final text: “America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned” (King, “I Have a Dream,” 82). Several other drafts and suggestions were posed. References to Abraham Lincoln and the Emancipation Proclamation were sustained throughout the countless revisions. King recalled that he did not finish the complete text of the speech until 3:30 A.M. on the morning of 28 August.

Later that day, King stood at the podium overlooking the gathering. Although a typescript version of the speech was made available to the press on the morning of the march, King did not merely read his prepared remarks. He later recalled: “I started out reading the speech, and I read it down to a point … the audience response was wonderful that day…. And all of a sudden this thing came to me that … I’d used many times before.... ‘I have a dream.’ And I just felt that I wanted to use it here … I used it, and at that point I just turned aside from the manuscript altogether. I didn’t come back to it” (King, 29 November 1963).

The following day in the New York Times, James Reston wrote: “Dr. King touched all the themes of the day, only better than anybody else. He was full of the symbolism of Lincoln and Gandhi, and the cadences of the Bible. He was both militant and sad, and he sent the crowd away feeling that the long journey had been worthwhile” (Reston, “‘I Have a Dream …’”).

Carey to King, 7 June 1955, in Papers 2:560–561.

Hansen, The Dream, 2003.

King, Address at the Freedom Rally in Cobo Hall, in A Call to Conscience , ed. Carson and Shepard, 2001.

King, “I Have a Dream,” Address Delivered at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, in A Call to Conscience , ed. Carson and Shepard, 2001.

King, Interview by Donald H. Smith, 29 November 1963, DHSTR-WHi .

King, “The Negro and the American Dream,” Excerpt from Address at the Annual Freedom Mass Meeting of the North Carolina State Conference of Branches of the NAACP, 25 September 1960, in Papers 5:508–511.

King, “A Realistic Look at the Question of Progress in the Area of Race Relations,” Address Delivered at St. Louis Freedom Rally, 10 April 1957, in Papers 4:167–179.

King, Unfulfilled Hopes, 5 April 1959, in Papers 6:359–367.

James Reston, “‘I Have a Dream…’: Peroration by Dr. King Sums Up a Day the Capital Will Remember,” New York Times , 29 August 1963.

- Australia edition

- International edition

- Europe edition

Martin Luther King: the story behind his 'I have a dream' speech

It’s 50 years since King gave that speech. Gary Younge finds out how it made history (and how it nearly fell flat)

T he night before the March on Washington , on 28 August 1963, Martin Luther King asked his aides for advice about the next day’s speech. “Don’t use the lines about ‘I have a dream’, his adviser Wyatt Walker told him. “It’s trite, it’s cliche. You’ve used it too many times already.”

King had indeed employed the refrain several times before. It had featured in an address just a week earlier at a fundraiser in Chicago, and a few months before that at a huge rally in Detroit. As with most of his speeches, both had been well received, but neither had been regarded as momentous.

This speech had to be different. While King was by now a national political figure, relatively few outside the black church and the civil rights movement had heard him give a full address. With all three television networks offering live coverage of the march for jobs and freedom, this would be his oratorical introduction to the nation.

After a wide range of conflicting suggestions from his staff, King left the lobby at the Willard hotel in DC to put the final touches to a speech he hoped would be received, in his words, “like the Gettysburg address”. “I am now going upstairs to my room to counsel with my Lord,” he told them. “I will see you all tomorrow.”

A few floors below King’s suite, Walker made himself available. King would call down and tell him what he wanted to say; Walker would write something he hoped worked, then head up the stairs to present it to King.

“When it came to my speech drafts,” wrote Clarence Jones, who had already penned the first draft, “[King] often acted like an interior designer. I would deliver four strong walls and he would use his God-given abilities to furnish the place so it felt like home.” King finished the outline at about midnight and then wrote a draft in longhand. One of his aides who went to King’s suite that night saw words crossed out three or four times. He thought it looked as though King were writing poetry. King went to sleep at about 4am, giving the text to his aides to print and distribute. The “I have a dream” section was not in it.

A few hours after King went to sleep, the march’s organiser, Bayard Rustin, wandered on to the Washington Mall, where the demonstration would take place later that day, with some of his assistants, to find security personnel and journalists outnumbering demonstrators. Political marches in Washington are now commonplace, but in 1963 attempting to stage a march of this size in that place was unprecedented. The movement had high hopes for a large turnout and originally set a goal of 100,000. From the reservations on coaches and trains alone, they guessed they should be at least close to that figure. But when the morning came, that expectation did little to calm their nerves. Reporters badgered Rustin about the ramifications for both the event and the movement if the crowd turned out to be smaller than anticipated. Rustin, forever theatrical, took a round pocket watch from his trousers and some paper from his jacket. Examining first the paper and then the watch, he turned to the reporters and said: “Everything is right on schedule.” The piece of paper was blank.

The first official Freedom Train arrived at Washington’s Union station from Pittsburgh at 8.02am, records Charles Euchner in Nobody Turn Me Around. Within a couple of hours, thousands were pouring through the stations every five minutes, while almost two buses a minute rolled into DC from across the country. About 250,000 people showed up that day. The Washington Mall was awash with Hollywood celebrities, including Charlton Heston, Sidney Poitier, Sammy Davis Jr, Burt Lancaster, James Garner and Harry Belafonte. Marlon Brando wandered around brandishing an electric cattle prod, a symbol of police brutality. Josephine Baker made it over from France. Paul Newman mingled with the crowd.

It was a hectic morning for King, paying a courtesy visit with other march leaders to politicians at the Capitol, but he still found time to fiddle with the speech. When he eventually walked to the podium, the typed final version was once more full of crossings out and scribbles.

Rustin had limited the speakers to just five minutes each, and threatened to come on with a crook and haul them from the podium when their time was up. But they all overran and, given the heat – 87F at noon – and humidity, the crowd’s mood began to wane. Weary from a night’s travel, many were anxious to make good time on the journey back and had already left. King was 16th on an official programme that included the national anthem, the invocation, a prayer, a tribute to women, two sets of songs and nine other speakers. Only the benediction and the pledge came after. Portions of the crowd had moved off to seek respite from the heat under the trees on the Mall while others dipped their feet in the reflecting pool. Those most eager for a view of the podium braved the sun under the shade of their umbrellas.

“There was… an air of subtle depression, of wistful apathy which existed in many,” wrote Norman Mailer. “One felt a little of the muted disappointment which attacks a crowd in the seventh inning of a very important baseball game when the score has gone 11-3. The home team is ahead, but the tension is broken: one’s concern is no longer noble.”

But if they were exhausted, they were no less excited. Gospel singer Mahalia Jackson had lifted spirits with I’ve Been ‘Buked and I’ve Been Scorned. Joachim Prinz, president of the American Jewish Congress, followed, recalling his time as a rabbi in Berlin under Hitler: “A great people who had created a great civilisation had become a nation of silent onlookers. They remained silent in the face of hate, in the face of brutality and in the face of mass murder,” he said. “America must not become a nation of onlookers. America must not remain silent.”

King was next. The area around the mic was crowded with speakers, dignitaries and their entourages. Wearing a black suit, black tie and white shirt, King edged through the melee towards the podium.

“I tell students today, ‘There were no jumbotrons [large screen TVs] back then,’ “ says Rachelle Horowitz, the young activist who organised transport to the march. “All people could see was a speck. And they listened to it.”

King started slowly, and stuck close to his prepared text. “I thought it was a good speech,” recalled John Lewis, the leader of the student wing of the movement, who had addressed the march earlier that day. “But it was not nearly as powerful as many I had heard him make. As he moved towards his final words, it seemed that he, too, could sense that he was falling short. He hadn’t locked into that power he so often found.”

King was winding up what would have been a well-received but, by his standards, fairly unremarkable oration. “Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to South Carolina, go back to Georgia, go back to Louisiana,” he said. Then, behind him, Mahalia Jackson cried out: “Tell ‘em about the dream, Martin.” Jackson had a particularly intimate emotional relationship with King, who when he felt down would call her for some “gospel musical therapy”.

“She was his favourite gospel singer, and he would ask her to sing The Old Rugged Cross or Jesus Met The Woman At The Well down the phone,” Jones explains. Jackson had seen him deliver the dream refrain in Detroit in June and clearly it had moved her.

“Go back to the slums and ghettoes of our northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed,” King said. Jackson shouted again: “Tell ‘em about the dream.” “Let us not wallow in the valley of despair. I say to you today, my friends.” Then King grabbed the podium and set his prepared text to his left. “When he was reading from his text, he stood like a lecturer,” Jones says. “But from the moment he set that text aside, he took on the stance of a Baptist preacher.” Jones turned to the person standing next to him and said: “Those people don’t know it, but they’re about to go to church.”

A smattering of applause filled a pause more pregnant than most.

“So even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream.”

“Aw, shit,” Walker said. “He’s using the dream.”

For all King’s careful preparation, the part of the speech that went on to enter the history books was added extemporaneously while he was standing on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, speaking in full flight to the crowd. “I know that on the eve of his speech it was not in his mind to revisit the dream,” Jones insists.

It is open to debate just how spontaneous the insertion of the “I have a dream” section was (Euchner says a guest in the adjacent hotel room to King heard him rehearsing the segment the night before), but the two things we know for sure are that it was not in the prepared text and it wasn’t invented on the spot. King had been using the refrain for well over a year. Talking some months later of his decision to include the passage, King said: “I started out reading the speech, and I read it down to a point. The audience response was wonderful that day… And all of a sudden this thing came to me that… I’d used many times before… ‘I have a dream.’ And I just felt that I wanted to use it here… I used it, and at that point I just turned aside from the manuscript altogether. I didn’t come back to it.”

“Though [King] was extremely well known before he stepped up to the lectern,” Jones wrote, “he had stepped down on the other side of history.”

Watching the whole thing on TV in the White House, President John F Kennedy, who had never heard an entire King speech before, remarked: “He’s damned good. Damned good.” Almost everyone, including even King’s enemies, recognised the speech’s reach and resonance. William Sullivan, the FBI’s assistant director of domestic intelligence, recommended: “We must mark him now, if we have not done so before, as the most dangerous negro of the future of this nation.”

A few in the crowd were unimpressed. Anne Moody, a black activist who had made the trip from rural Mississippi, recalled: “I sat on the grass and listened to the speakers, to discover we had ‘dreamers’ instead of leaders leading us. Just about every one of them stood up there dreaming. Martin Luther King went on and on talking about his dream. I sat there thinking that in Canton we never had time to sleep, much less dream.”

But most were ebullient. “It would be like if, right now in the Arab spring, somebody made a speech that was 15 minutes long that summarised what this whole period of social change was all about,” one of King’s most trusted aides, Andrew Young, told me. “The country was in more turmoil than it had been in since before the second world war. People didn’t understand it. And he explained it. It wasn’t a black speech. It wasn’t just a Christian speech. It was an all-American speech.”

Fifty years on, the speech enjoys both national and global acclaim . A 1999 survey conducted by researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and Texas A&M University , of 137 leading scholars of public address, named it the greatest speech of the 20th century.

During the protests in Tiananmen Square, China, some protesters held up posters of King saying “I have a dream”. On the wall that Israel has built around parts of the West Bank, someone has written “I have a dream. This is not part of that dream.” The phrase “I have a dream” has been spotted in such disparate places as a train in Budapest and on a mural in suburban Sydney. Asked in 2008 whether they thought the speech was “relevant to people of your generation”, 68% of Americans said yes, including 76% of blacks and 67% of whites. Only 4% were not familiar with it.

But few of those in the movement thought at the time that it would be the speech by which King would be remembered 50 years later.

“Rustin always said that King’s genius was that he could simultaneously talk to a black audience about why they needed to achieve their freedom and address a white audience about why they should support that freedom,” recalls Horowitz. “Simultaneously. It was a genius that he could do that as one Gestalt… King’s was the poetry that made the march immortal. He capped off the day perfectly. He did what everybody wanted him to do and expected him to do. But I don’t think anybody predicted at the time that the speech would do what it did since.”

Their bemusement was justified. For if, in its immediate aftermath, the speech had any significant political impact, it was not obvious. “At the time of King’s death in April 1968 , his speech at the March on Washington had nearly vanished from public view,” writes Drew Hansen in his book about the speech, The Dream. “There was no reason to believe that King’s speech would one day come to be seen as a defining moment for his career and for the civil rights movement as a whole… King’s speech at the march is almost never mentioned during the monumental debates over the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which occupy around 64,000 pages of the Congressional record.”

History does not objectively sift through speeches, pick out the best on their merits and then dedicate them faithfully to public memory. It commits itself to the task with great prejudice and fickle appreciation, in a manner that tells us as much about the historian and the times as the speech itself. The speech was marginalised because, in the last few years of his life, King himself was marginalised, and few who had the power to elevate his speech to iconic status had any self-interest in doing so. His growing propensity to take on issues of poverty, followed by his opposition to the Vietnam war, lost him the support of the political class and much of his white and more conservative base.

King’s speech at the March on Washington offers a positive prognosis on the apparently chronic American ailment of racism. As such, it is a rare thing to find in almost any culture or nation: an optimistic oration about race that acknowledges the desperate circumstances that made it necessary while still projecting hope, patriotism, humanism and militancy.

In the age of Obama and the Tea Party, there is something in there for everyone. It speaks, in the vernacular of the black church, with clarity and conviction to African Americans’ historical plight and looks forward to a time when that plight will be eliminated (“We can never be satisfied as long as our children are stripped of their selfhood and robbed of their dignity by signs stating ‘for whites only’. No, no, no, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream”).

Its nod to all that is sacred in American political culture, from the founding fathers to the American dream, makes it patriotic (“I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed, ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.’”). It sets bigotry against colour-blindness while prescribing no route map for how we get from one to the other. (“I have a dream that one day, down in Alabama, with its vicious racists… little black boys and little black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.”)

But the breadth of its appeal is to some extent at the expense of depth. It is in no small part so widely admired because the interpretations of what King was saying vary so widely. Polls show that while African Americans and American whites both agree about the extent to which “the dream has been realised”, they profoundly disagree on the state of contemporary race relations. The recent acquittal of George Zimmerman over the shooting of the black teenager Trayvon Martin illustrates the degree to which blacks and whites are less likely to see the same problems, more likely to disagree on the causes of those problems and, therefore, unlikely to agree on a remedy. Hearing the same speech, they understand different things.

Conservatives, meanwhile, have been keen to co-opt both King and the speech. I n 2010, Tea Party favourite Glenn Beck held the “Restoring Honour” rally at the Lincoln Memorial on the 47th anniversary of the speech, telling a crowd of about 90,000: “The man who stood down on those stairs… gave his life for everyone’s right to have a dream.” Almost a year later, black republican presidential candidate Herman Cain opened his speech to the southern Republican leadership conference with the words, “I have a dream.”

Their embrace of the speech has made some black intellectuals and activists wary. They fear that the speech can too easily be distorted in a manner that undermines the speaker’s legacy. “In the light of the determined misuse of King’s rhetoric, a modest proposal appears in order,” Georgetown university professor Michael Dyson wrote in 2001. “A 10-year moratorium on listening to or reading ‘I Have a Dream’.” At first blush, such a proposal seems absurd and counter- productive. After all, King’s words have convinced many Americans that racial justice should be aggressively pursued. The sad truth is, however, that our political climate has eroded the real point of King’s beautiful words.”

These responses tell us at least as much about now as then, perhaps more. The 50th anniversary of “I have a dream” arrives at a time when the president is black, whites are destined to become a minority in the US in little more than a generation, and civil rights-era protections are being dismantled. Segregationists have all but disappeared, even if segregation as a lived experience has not. Racism, however, remains.

Fifty years on, it is clear that in eliminating legal segregation – not racism, but formal, codified discrimination – the civil rights movement delivered the last moral victory in America for which there is still a consensus. While the struggle to defeat it was bitter and divisive, nobody today is seriously campaigning for the return of segregation or openly mourning its demise. The speech’s appeal lies in the fact that, whatever the interpretation, it remains the most eloquent, poetic, unapologetic and public articulation of that victory.

- Martin Luther King

- US politics

Barack Obama's speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial – full transcript

March on Washington: Barack Obama leads 50th anniversary celebrations

The meaning of Martin Luther King's speech: then and now

Thousands march on Washington to remember Martin Luther King's dream

March on Washington: 50th anniversary – in pictures

March on Washington: thousands arrive for 50th anniversary – as it happened

Remembering my time at the 1963 March on Washington

Comments (…), most viewed.

National Archives at New York City

Martin Luther King, Jr.

On August 28, 1963, Martin Luther King Jr., delivered a speech to a massive group of civil rights marchers gathered around the Lincoln memorial in Washington DC. The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom brought together the nations most prominent civil rights leaders, along with tens of thousands of marchers, to press the United States government for equality. The culmination of this event was the influential and most memorable speech of Dr. King's career. Popularly known as the "I have a Dream" speech, the words of Martin Luther King, Jr. influenced the Federal government to take more direct actions to more fully realize racial equality.

Mister Maestro, Inc., and Twentieth Century Fox Records Company recorded the speech and offered the recording for sale. Dr. King and his attorneys claimed that the speech was copyrighted and the recording violated that copyright. The court found in favor of Dr. King. Among the papers filed in the case and available at the National Archives at New York City is a deposition given by Martin Luther King, Jr. and signed in his own hand.

Educational Activities

Discussion Questions:

- What was the official name for the event on August 28th, 1963? What does this title tell us about its focus?

- What organizations were involved in the the March on Washington? What does this tell us about the event?

- How does Martin Luther King, Jr. describe his writing process?

- What are the major issues of this case? In other words, what is Martin Luther King, Jr. disputing?

- How does Martin Luther King, Jr. describe his earlier speech on June 23rd in Detroit?

- How does Martin Luther King, Jr. compare and contrast the two "I have a dream..." speeches? What are the major similarities and differences?

Additional Resources from the National Archives concerning Martin Luther King, Jr.

- Official Program for the March on Washington

- The March (from the National Archives YouTube Channel)

- Searching for Martin Luther King, Jr., in the records of the National Archives

- Records on African Americans at the National Archives

- Teaching With Documents: Court Documents Related to Martin Luther King, Jr., and Memphis Sanitation Workers

Other Resources on Martin Luther King, Jr.

- The King Center

- National Park Service-National Historic Site

- Read Martin Luther King Jr.'s 'I Have a Dream' speech in its entirety - National Public Radio (NPR)

50 Years Later: The Cultural Significance of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s "I Have A Dream Speech"

On this day 50 years ago, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. gave his famous "I Have a Dream" speech to a crowd of over 200,000 civil rights supporters from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Commentator and Murray State History Professor Dr. Brian Clardy reflects on this defining moment of the Civil Rights Movement, and it's cultural significance then and 50 years later.

On a hot and sweltering Summer of 1963 afternoon, the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered one of the most popularly quoted speeches in American history. It was given towards the end of the historic March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom where nearly a quarter of a million non-violent demonstrators gathered under their First Amendment guarantees of peaceable assembly to present a grievance to their government to protest for first rate citizenship rights.

The speech was known for its sweeping oratory, with a few lines standing out and quoted frequently. Dr. King’s quotation of the Declaration of Independence echoed the essence of the social contracts musings on “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,” but the lines that preceded it are more reflective of the speech’s revolutionary nature. Channeling the early Founders of the United States, King warned of dire consequences should the segregated status quo remain intact. He chided:

"It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment. This sweltering summer of the Negro's legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality. Nineteen sixty-three is not an end, but a beginning. And those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual."

This oft-neglected portion of the speech reflected the more practical elements of non-violent protest movements. An astute student of the writings of Mahatma Gandhi , Henry David Thoreau, and the mystical theologian Howard Thurmann, King believed that if dissent were channeled into creative non-violent protest that the likelihood of any movement disintegrating into an orgy of unrestrained mayhem would be nil. Moreover, King’s theological training informed the speech in its appeals to revolutionary Christian ideals, like that of Paul and later intellectuals like Reinhold Niebuhr and Walter Rauschenbusch.

Dr. King’s clarion call for racial equality was also buttressed by an appeal for racial collaboration and harmony……….a harmony that showed the connection between the freedom and liberation of the human spirit and the acquiescence of basic legal rights.

But the most frequently quoted portion of the speech, must also be put into context, in terms of its rhythm, delivery, and its roots that harken back to the homiletical style of Sacred Rhetoric that is a staple of the Black Church tradition. Dr. King first heard the rhytymic phrase, “I Have a Dream” from a young and enterprising preacher named Prathia Hall at a rally about a year before the 1963 March……and King had given a truncated version of the speech in various cities. However, Dr. King used the ebb and flow of the phrase in order to succinctly describe the movement’s aims and objectives by incorporating the Old Testament prophecy and the idealism of the Social Gospel. He said:

"I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, and every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight; 'and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed and all flesh shall see it together.'"

Fifty years have come and gone since that historic moment in American oratory. And, for the most part, many of the aspects of the “dream” have become reality. But in order to make sure that that spirit of idealism continues uninterrupted, it is absolutely vital to understand the nature and scope of the entire speech……the place it into its proper context…….and to appreciate its contemporary and practical meaning.

Dr. Brian Clardy is an Assistant Professor of History and Coordinator of Religious Studies at Murray State University. He is also the Wednesday night host of Cafe Jazz on WKMS.

Importance of the ‘I Have a Dream’ Speech

[August 28, 2019] It was 56 years ago today, August 28, 1963, when Martin Luther King, Jr. gave his famous and inspiring ‘I Have a Dream’ speech at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. Most of us believe the importance of his speech centered on removing racial segregation and discrimination against blacks in America.

MLK’s speech was much more. Certainly, he was most concerned about how blacks were treated in America. He was also aware of American ideals, and so he drew attention to the U.S. Declaration of Independence because it was the core of America. MLK wanted to express the fact that our nation was not living up to this ideal but were on the precipice of rejecting the legal and social racism of our time.

“I have a dream, that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal.’”

MLK understood that for a nation to remain viable, it must be possible to live among one another; to show respect and care for one another, to be united. This is how any free nation must exist; else it will destroy itself from within. In the following sentences, he expressed the classic American view that it mattered not where you came from, what religion you practiced, or your race but that you could sit down with anyone and create a better place to live, work, and raise a family.

“I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slaveowners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood. I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

MLK also knew that the best way forward was to base social contracts on our hard-earned skills, not upon the color of our skin. He called it ‘character,’ and he was right that no free society can exist without it. We should never be judged based on our skin color, tribe, gender, or religion but upon our moral fiber; that which makes us a good (or bad) person.

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today.” – Martin Luther King, Jr. August 28, 1963

MLK’s belief in God and his view that all humankind was ready for the freedom we so often aspire to, is what drove him in his speeches. Freedom is in the heart of all Americans; sometimes, we don’t see it. Sometimes we need reminding, and he did exactly that for us.

“When we allow freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, ‘Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!’”

18 thoughts on “ Importance of the ‘I Have a Dream’ Speech ”

This was undoubtedly a great speech because it moved us emotionally and intellectually. But most crucial to its success was the emotional appeal to the ideals of our nation’s foundation; freedom !! This is exactly what the people of Hong Kong also wish to achieve.

Video on YouTube of the “I have a dream speech.” Short. I recommend watching it. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I47Y6VHc3Ms

They called him the “moral leader of our nation.” They were right.

Excellent point.

Yes, he was the moral leader of our nation in that respect.

Thanks Martin.

Thank you for the reminder of this great speech. It’s 16 minutes long. I understand that Martin Luther King, Jr. had only 7 minutes to give his speech. Being the last to speak he got carried away and gave, fortunately, one of the greatest speeches ever.

Hi Dennis, haven’t heard from you in a while. Good comment and yes I think you are correct in that he exceeded his time allotment.

Thanks for this article on such a great speech. It is always a pleasure to read about our ideals and how others remind us of them and help point us in the right direction.

My grandfather always said that we are not perfect but I expect you to be damn near perfect. Ha Ha. He was the kind of fellow you never wanted to disappoint. There is a huge difference in Pocahontas, lying Eliz. Warren and MLK.

Contrast this speech by a flawed man to Elizabeth Warren from yesterday’s article by Gen. Satterfield. “‘Pocahontas’ Could Still Be Elizabeth Warren’s Biggest Vulnerability: Sure, she calmed nervous progressives. But it’s moderates who might be susceptible to Trump’s attack on her honesty. ” https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2019/08/27/pocahontas-elizabeth-warrens-biggest-vulnerability-227912

An emotionally stirring speech based on lies differs from a great speech based on our ideals. Yes, I agree, a big difference.

Excellent article on one of the best speeches in America. Study it, for that will help anyone who understands people to better communicate any idea.

There are articles out on the Internet that just discuss the construction of the speech and how it is effective.

Since I am much older than nearly everyone here, I can say that I remember watching the speech on the television. Despite not having a good opinion of MLK at the time, his speech was great.

Good to hear from you again, Eva. Been a long time. Good comment.

Eva, thanks for your spot-on comment and for telling us about when you heard the speech for the first time. I agree that many did not like MLK because he was upsetting our viewpoints. Sometimes it takes someone we don’t like to help set us straight.

Thanks you JT and Andrew. I’ve been ill but I’m back.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

7 Things You May Not Know About MLK’s ‘I Have a Dream’ Speech

By: Sarah Pruitt

Updated: August 3, 2023 | Original: January 13, 2021

On August 28, 1963, in front of a crowd of nearly 250,000 people spread across the National Mall in Washington, D.C., the Baptist preacher and civil rights leader Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his now-famous “I Have a Dream” speech from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.

Organizers of the event, officially known as the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, had hoped 100,000 people would attend. In the end, more than twice that number flooded into the nation’s capital for the massive protest march, making it the largest demonstration in U.S. history to that date.

King’s “I Have a Dream” speech now stands out as one of the 20th century’s most unforgettable moments, but a few facts about it may still surprise you.

1. There were initially no women included in the event.

Despite the central role that women like Rosa Parks , Ella Baker, Daisy Bates and others played in the civil rights movement , all the speakers at the March on Washington were men. But at the urging of Anna Hedgeman, the only woman on the planning committee, the organizers added a “Tribute to Negro Women Fighters for Freedom” to the program. Bates spoke briefly in the place of Myrlie Evers, widow of the murdered civil rights leader Medgar Evers , and Parks and several others were recognized and asked to take a bow. “We will sit-in and we will kneel-in and we will lie-in if necessary until every Negro in America can vote,” Bates said. “This we pledge to the women of America.”

2. A white labor leader and a rabbi were among the 10 speakers on stage that day.