Biomedical Graduate Education

Capstone Projects

2022-2023 graduates, nelson moore.

Data Scientist at Essential Software Inc

Capstone Project: Modeling and code implementation to support data search and filter through the NCI Cancer Data Aggregator Industry Mentor: Frederick National Lab for Cancer Research: FNLCR

Joelle Fitzgerald

Business Analyst at Ascension Health Care

Capstone Project: Analysis of patient safety event reports data. Industry Mentor: MedStar Health. National Center for Human Factors in Healthcare

Kader (Abdelkader) Bouregag

Healthcare Xplorer | Medical Informatics at Genentech (internship)

Capstone Project: Transforming the Immuno-Oncology data to the OMOP CDM Industry Mentor: MSKCC/ MedStar/ Georgetown University/ Hackensack

Junaid Imam

Data Scientist at Medstar Institute

Capstone Project: Create an [trans-] eQTL visualization tool

Industry Mentor: Pfizer Inc / Harvard

Abbie Gillen

Staff Data Analyst at Nice Healthcare

Capstone Project: Nice Healthcare: Predicting Nice healthcare utilization

Industry Mentor: Nice Healthcare

Capstone Project: Next Generation Data Commons

Industry Mentor: ICF International

2021-2022 Graduates

Ahson saiyed.

NLP Engineer/Data Scientist at TrinetX

Capstone Project : Research Data Platform Pipelines Industry Mentor: Invitae

Walid Nashashibi

Data Scientist at FEMA

Capstone Project: Xenopus RNA-Seq Analysis to Understand Tissue Regeneration Mechanisms Industry Mentor: FDA

Tony Albini

Data Analyst at ClearView Healthcare Partners

Capstone project: Data Mining to understand the patient landscape of Chronic Kidney Disease Population Industry Mentor: AstraZeneca

Anvitha Gooty Agraharam

Business Account Manager at GeneData

Capstone Project: Computational estimation of Pleiotropy in Genome-Phenome Associations for target discovery Industry Mentor: AstraZeneca

Natalie Cortopassi

Researcher at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation

Capstone project: Analysis of Clinical Trial Attrition in Neuropsychiatric Clinical Trials using Machine Learning Industry Mentor: AstraZeneca

Christle Iroezi

Business System Analyst at Centene Corporation

Capstone project: Visualize Digital HealthCare ROI Industry Mentor: MedStar Health

R & D Analyst II at GEICO

Capstone project: Heat Waves and Health Outcomes Industry Mentor: ICF

Research Specialist at Georgetown University

Capstone project: Mental Health Data Commons Industry Mentor: ICF

2020-2021 Graduates

Technology Transformation Analyst, Grant Thornton LLP

Capstone Project: Research Data Platform Pipelines Industry Mentor: Invitae

Research Technician at Georgetown University

Capstone Project: Using a configurable, open-source framework to create a fully functional data commons with the REMBRANDT dataset Industry Mentor: Frederick National Lab for Cancer Research – FNLCR

Consultant at Deloitte

Capstone Project: Building a patient centric data warehouse Industry Mentor: Invitae

Marcio Rosas

Project Manager of Technology and Informatics at Georgetown University

Capstone Project: Knowledge-Based Predictive Modeling of Clinical Trials Enrollment Rates Industry Mentor : AstraZeneca

Yuezheng (Kerry) He

Data Product Associate at YipitData

Capstone Project: ClinicalTrials2Vec – Accelerating trial-level computing using a vectorized model of clinical trial summaries and results Industry Mentor: AstraZeneca

Data Programmer at Chemonics International

Capstone Project: Multi-scale modeling to enable data-driven biomarker and target discovery Industry Mentor: AstraZeneca

2019-2020 Graduates

Pratyush tandale.

Informatics Specialist I at Mayo Clinic

Capstone Project: Improving clinical mapping process for lab data using LOINC Industry Mentor: Flatiron Roche

Shabeeb Kannattikuni

Senior Statistical Programmer at PRA Health Sciences (ICON Pl)

Capstone Project: NGS Data Analysis for the QA of viral vaccines Industry Mentor: Argentys Informatics

Fuyuan Wang (Bruce)

Software Engineer at Essential Software Inc , Frederick National Labs

Capstone Project: Cancer Data Model Visualization framework Industry Mentor: Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research

Ayah Elshikh

Capstone Project: NGS Data Analysis for the QA of viral vaccines

Industry Mentor: Argentys Informatics

Yue (Lilian) Li

Biostatistician and Statistical Programmer , Baim Institute for Clinical Research

Capstone Project: Analysis of COVID-19 Serological test data to improve the COVID-19 Detection capabalities Industry Mentor: Argentys Informatics

Algorithm Performance Engineer at Optovue

Capstone Project: Socioeconomic factors to readmissions after major cancer surgery Industry Mentor: Medstar Health

Jiazhong Zhang

Management Trainee at China Bohai Bank

Jianyi Zhang

MMHC Capstone Strategy Project

The Capstone Project engages teams of students on projects of significant importance to their organizations. The student team is responsible for diagnosing the critical problem, defining an appropriate scope of work, managing institutional expectations, and producing a suitable recommendation in both written and presentation form.

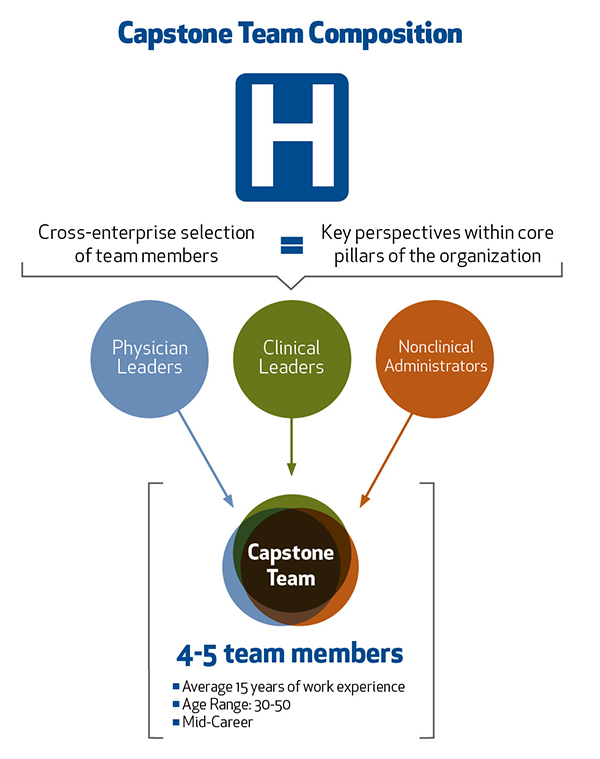

Your Capstone Team

It takes many managers, healthcare practitioners and other executives to care for a patient and to manage a healthcare organization. Having the skills to manage a team, evaluate critical problems, and execute solutions is required to be an effective business leader. This is why your Capstone Team will be comprised of a cross-functional group of 4-5 executives, each with a diverse set of backgrounds and industry experiences, giving you an experience that emulates the work environment of a healthcare delivery organization. Support includes coaching on team dynamics and the progress of your work together, checkpoints to ensure you’re on track, and guidance for projects that serve as a real-world learning lab.

The Project

The Capstone Strategy Project complements the classroom instruction and is defined as learning by construction. It is a total immersion experience in which students are challenged to use all of the tools and concepts learned to date to tackle a current business problem for a healthcare organization.

With faculty oversight, you demonstrate rigorous application of business concepts and disciplines. Leading a project of utmost importance for your organization provides immediate impact that benefits the student and the sponsoring organization.

Your team will kick off the Capstone Strategy Project in Mod 3 by meeting with the client sponsor to outline and discuss the initiative at hand. Your team will spend the next six months working on all aspects of the project, including:

As the class makeup represents a very diverse talent pool within a healthcare organization, it promotes working outside of our comfort zones and valuing the skills and experiences of others. There is no doubt that the biggest thing I will miss after graduation is the weekly (and often several times weekly depending on team project deadlines) camaraderie experienced by the class. Gaelyn Garrett MMHC 2015

The Benefits For You

For the students, the Capstone Strategy Projects are opportunities to exhibit the healthcare business management knowledge you’ve acquired. You will demonstrate, to yourself and your organization, your ability to problem-solve creatively, make strategic decisions, and manage as part of a high-level executive team. Learn More .

The Benefits for Your Organization

For an organization, the Capstone Strategy Projects is an opportunity to have a team of experienced mid-level health care professionals conduct an intense engagement to address a current business need. Learn More .

See how MMHC students' capstone helped improve Emergency Department wait times and efficiency at VUMC.

How MMHC benefits your organization

A closer look at the program through the eyes of students, faculty and sponsoring organizations

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 19 May 2020

A global health capstone: an innovative educational approach in a competency-based curriculum for medical students

- Stacey Chamberlain ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8642-2129 1 ,

- Nicole Gonzalez 1 ,

- Valerie Dobiesz 2 ,

- Marcia Edison 1 ,

- Janet Lin 1 &

- Stevan Weine 1

BMC Medical Education volume 20 , Article number: 159 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

3436 Accesses

3 Citations

Metrics details

Global health educational programs for medical and public health professionals have grown substantially in recent years. The University of Illinois Chicago College of Medicine (UICOM) began a global medicine (GMED) program for selected students in 2012 and has since graduated four classes. As part of the four-year curriculum, students complete a longitudinal global health capstone project. This paper describes the global health capstone project as an innovative educational tool within a competency-based curriculum.

The authors define and describe the longitudinal global health capstone including specific requirements, student deliverables, and examples of how the global health capstone may be used as part of a larger curriculum to teach the competency domains identified by the Consortium of Universities for Global Health. The authors also reviewed the final capstone projects for 35 graduates to describe characteristics of capstone projects completed.

The global health capstone was developed as one educational tool within a broader global health curriculum for medical students. Of the 35 capstones, 26 projects involved original research (74%), and 25 involved international travel (71%). Nine projects led to a conference abstract/presentation (26%) while five led to a publication (14%). Twenty-one projects (60%) had subject matter-focused faculty mentorship.

Conclusions

A longitudinal global health capstone is a feasible tool to teach targeted global health competencies and can provide meaningful opportunities for research and career mentorship. Further refinement of the capstone process is needed to strengthen mentorship, and additional assessment methods are needed.

Peer Review reports

Participation in global health activities by U.S. medical students has grown substantially in recent decades [ 1 ]. Although global health interest has grown, many schools still do not offer structured global health curricula, and there is little standardization for didactic, clinical, scholarly, and cultural components across programs [ 2 , 3 ]. The past decade saw the development of essential competencies to guide global health curricular development [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ]. However, many programs lack well-defined competencies outlining critical skills for global health practitioners. The most notable global health competency framework identifies 39 competencies across 11 domains and was published in 2015 by an interdisciplinary expert panel from the Consortium of Universities for Global Health (CUGH). Many of the identified competencies include not only knowledge acquisition but also skills building and attitude formation [ 4 ]. Particularly in resource-limited settings involving different cultures, political climates, and power dynamics, effective global health practitioners need competence in cultural humility, inter-professional collaboration, ethical conduct, and promotion of health equity. One major challenge is for educators to identify methods to teach these competencies that will enable students to become successful global health practitioners.

Aspects of various global health curricula have been published. Some describe didactic curricula focused on topics such as cultural competency and communication [ 11 ]. Others describe educational formats including e-learning or simulation-based learning to teach competencies such as ethics or professional practice in low-resource settings [ 12 , 13 , 14 ]. Many programs involve international electives or service-learning experiences, and best practice approaches have been proposed to help students in short-term global health experiences build skills in cross-cultural effectiveness, capacity building, and collaboration while addressing the needs of host communities and partners [ 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ]. Although there are some published descriptions of global health capstones for pharmacy and bioengineering students, there are no known published descriptions of global health capstones as part of an educational curriculum for medical students [ 19 , 20 ].

The Global Medicine (GMED) Program is a longitudinal four-year track for select medical students that began in 2012, in response to increased interest in global health at the University of Illinois Chicago College of Medicine (UICOM). Completion of a longitudinal capstone project is required as part of the GMED program. Using a global health capstone project as an educational method for medical students is a novel construct. Although capstones are reported in other disciplines, they have not been routinely incorporated into global health medical student programs. Other fields found capstones beneficial because they allow students to:

Become involved in sustainable impact-oriented research [ 21 ].

Build skills in scholarship and professionalism including writing, presenting, and integrating “core theoretical concepts to form a broad view of professionalism.” [ 21 , 22 , 23 ]

Develop research mentorships and relationships with faculty [ 21 ].

In this paper, we describe the global health capstone including how the capstone can be used to teach essential global health competencies, and we report on characteristics of the global health capstone for the first 35 graduates of the GMED Program. This educational method may be of value to other global health educators who wish to develop or strengthen their global health training programs for health professions students.

Development of the Global Health Capstone

The UICOM GMED Program recruited its first class in 2012 and has since graduated four classes. The program’s goal is to improve the health of populations worldwide by training the next generation of global health leaders [ 24 ]. As part of the program, each GMED student must develop, implement, and present a capstone project to successfully complete the program. The global health capstone is defined as a longitudinal scholarly work focused on expanding knowledge and understanding of global health issues among underserved populations throughout the world. The capstone culminates in an oral presentation and reflection paper at the end of the final year of medical school. In 2019, we added an additional requirement of a formal written paper. The capstone is designed to allow students to acquire knowledge and skills through project planning and implementation.

The global health capstone was developed by a multidisciplinary group of faculty with global health and education experience following the steps outlined in the following section:

Develop Global Health capstone objectives

Faculty identified global health capstone objectives that focused on skills-building and complemented other components of the global health curriculum. The following objectives were identified for GMED students completing the capstone project:

Demonstrate and apply an understanding of global health education competencies;

Identify and utilize credible and scholarly sources of information concerning global health topics and perform an in-depth review of the literature;

Define an overall purpose and associated specific aims for the project;

Collaborate with a faculty mentor to ensure adequate progress on the project and receive regular feedback and evaluations;

Demonstrate effective professional and scientific communication skills through written products and presentations;

Apply critical thinking skills and a scientific methodology to the analysis of a project.

Define capstone focus and parameters

Koplan defines global health as, “an area for study, research, and practice that places a priority on improving health and achieving equity in health for all people worldwide. Global health emphasizes transnational health issues, determinants, and solutions; involves many disciplines within and beyond the health sciences and promotes interdisciplinary collaboration; and is a synthesis of population-based prevention with individual-level clinical care.” [ 25 ] Using this definition of global health to frame the focus of the capstone, students were instructed to identify a global health area that they might want to study further.

Because the UICOM has additional special tracks that address urban and rural health, we further required that global health capstone projects should focus on issues in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) or people from LMICs. This narrower focus allowed our program to avoid overlap with the other programs at our institution that concentrate on domestic health disparities.

Describe capstone structure

Capstone projects could vary in structure and content depending on students’ interests. All students received faculty advising that provided guidance for capstone completion. Projects could focus on original global health research or be comprised of curriculum design, program implementation, field practicum, systematic review, or a meta-analysis. All students were expected to demonstrate an understanding of these accepted global health core competencies: [ 4 ]

Global Burden of Disease

Globalization of Health and Healthcare

Social and Environmental Determinants of Health

Capacity Strengthening

Collaboration, Partnering, and Communication

Professional Practice

Health Equity and Social Justice

Program Management

Sociocultural and Political Awareness

Strategic Analysis

Table 1 identifies how the global health capstone can be used as a tool to address each competency domain and provides illustrative examples from completed student projects.

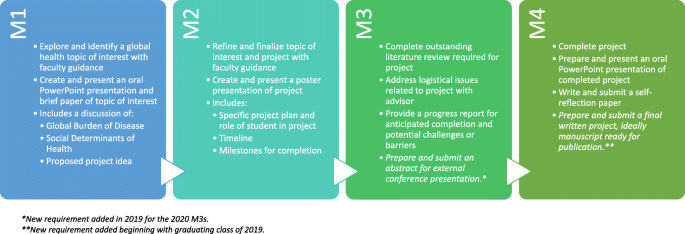

Identify capstone requirements and timeline

Specific deliverables were identified for the capstone project that would be required throughout the 4 years of medical school (Fig. 1 ). During the first year, each student identifies a particular global health issue, performs a literature review, writes a brief paper, and delivers a short oral presentation on his/her selected topic to peers and faculty. In the second year, each student identifies a specific project, defines his/her role in that project, establishes methods and a timeline for project completion, and prepares and presents a scientific poster. In the third and fourth years, students focus on capstone project implementation and evaluation, culminating in oral presentations summarizing their work. In their final presentations, students identify the global health problem addressed; describe the methods, results, and conclusions of the completed projects; and discuss the implications of their projects on the health of underserved communities and on their future practice as global physicians. Graduating students also submit a self-reflection paper upon capstone completion. This paper encourages students to reflect on their accomplishments, articulate the challenges and successes of their projects, and internalize their experiences to translate knowledge acquired to their personal and professional growth.

Global Health Capstone Process Map

It is critical to note that the capstone is only one component of the GMED program. In addition to the regular medical school curriculum, the GMED program includes didactic instruction, colloquia, and skills-building workshops described elsewhere [ 24 ]. GMED programming also includes exposure to supplementary content (e.g. cultural competency, economic perspectives of global aid, ethics of volunteerism) as well as alternative interactive learning formats including film reviews, book club discussions, and simulation-based cases.

Adapt and revise capstone requirements

Based on student feedback and faculty observation, several modifications were made to the original capstone design. We revised and more precisely defined the focus for global health capstone projects; this adaptation was made in response to project proposals that did not clearly have transnational health relevance. We adapted the capstone objectives to include updated global health competencies. The original GMED curriculum addressed global health competencies identified in 2010 by the Global Health Education Consortium. An expanded and updated list of competencies was identified by CUGH in 2018, and we revised our capstone objectives and guidelines to reflect this change [ 4 , 10 ]. A written scholarly paper was added as a requirement for 2019 graduates. Submitting an abstract to a non-UICOM conference was added as a third year requirement that will take effect starting in 2020. Ongoing capstone adaptations based on the findings of this review include instituting a new mentorship program (see Discussion).

We performed a retrospective review of graduating medical student capstone projects from the first three GMED cohorts (2016–2018) to determine the nature and range of projects completed. We were specifically interested in: [ 1 ] the types of projects completed [ 2 ]; whether the students identified a project faculty mentor [ 3 ]; whether the student travelled internationally as part of the project [ 4 ]; whether the project was related to the student’s chosen residency specialty; and [ 5 ] whether the project led to formal scholarship including an abstract/poster presentation or publication. To make these determinations, two authors (S.C., V.D., M.E., or J.L.) completed an independent document review of the capstone PowerPoint presentations of the first 35 graduating students. The authors then met, and any areas of disagreement were discussed until consensus was reached.

The criteria for each of the interest areas above are described here. For “types of projects completed,” we used the broad categories of clinical research, education, quality improvement, and service similar to other analyses [ 26 ]. We further characterized non-interventional clinical research capstones as systematic reviews versus original research. For original research projects, we determined whether projects used quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods. This information was gathered as part of our iterative process for the global health capstone design to help inform our team of potential areas of curricular enhancement. For example, if many students were completing qualitative analyses, we could consider adding additional qualitative assessment instruction as part of the formal GMED curriculum.

As noted previously, all students were assigned a faculty advisor who provided guidance throughout the capstone process. However, these advisors were not necessarily project mentors who possessed content expertise in the capstone area of focus, or may not have directly worked with the students on specific projects. Students who had capstone project-specific mentors explicitly mentioned in their presentations were considered to have had “project faculty mentors.”

It was determined that the student travelled internationally based on the final presentation. Similarly, the extent to which the project was related to residency specialty was determined by the judgment of the faculty reviewers, who decided if there was an evident relationship between the subject matter of the capstone project and the known scope of practice and subject matter relevance to a medical specialty. For example, a project on post-partum hemorrhage for a student who matched into orthopedic surgery was determined to be “unrelated,” but a project looking at point-of-care ultrasound use in emergency departments for a student who matched into emergency medicine was determined to be “related.”

A project led to a scholarly abstract/poster presentation and/or publication if students identified this in their presentations or if a PubMed search done at the time of our study revealed it. Publications of capstone work that occurred after students graduated, identified by the PubMed search, were included in this report.

Finally, one author (N.G.) identified capstone projects that illustrated aspects of the CUGH competencies based on student final presentations (Table 1 ).

The capstone is designed to enhance students’ scholarly skills and knowledge. As noted, students were given some flexibility as to the capstone structure and format. Of the initial 35 program graduates, 32 (91%) completed capstones involving non-interventional clinical research. Of those, five were systematic reviews, and one was a case series. Twenty-six capstones were categorized as original research. Of those, ten (39%) used mixed methods, ten (39%) used quantitative methods, and six (23%) used qualitative methods. Of the capstones that were not clinical research, two were education-focused and involved curriculum development, and one was a quality improvement project.

While all students had faculty advisors, 21 capstones (60%) involved projects where students had additional dedicated faculty mentorship, meaning they worked with a faculty member who possessed subject matter expertise and guided their capstone development and implementation. The remaining 14 projects (40%) were implemented in a more independent manner.

Capstones included projects in 14 different countries; eight additional projects had a transnational global health focus, and four projects focused on domestic and/or refugee populations in the U.S. (Table 2 ). Twenty-five capstones (71%) involved an international field experience.

Multiple medical specialty areas were identified, with the largest percentage of projects focused on emergency medicine (29%), obstetrics/gynecology (17%), and primary care (14%). Other projects focused on internal medicine (9%), psychiatry (6%), neurology (3%), ophthalmology (3%), and pediatrics (3%). In addition, six projects (17%) did not clearly align with a medical specialty area and instead focused on topics including environmental health, medical ethics, health systems, medical education, and mobile health (mHealth) smartphone applications. Eighteen students (51%) completed capstones related to their chosen medical residency specialty. Twenty-six percent of students presented capstone-related abstracts or presentations at conferences, and five (14%) authored peer-reviewed publications related to their capstones.

A longitudinal global health capstone is feasible for medical students

Overall, we found that a four-year longitudinal capstone is feasible. Skill development, knowledge acquisition, and mentorship were among the most important outcomes of the capstone process, and those outcomes were not dependent on students completing a single long-term project. Although many students had more than one specific project during their capstone, all students went through the same four-year longitudinal process with defined deliverables during each year of medical school. We found the focus on process important to provide a continuum of mentorship and opportunity to build cross-disciplinary skills, while allowing the students flexibility to change their specific final project focus and adapt to barriers they encountered in project implementation.

Giving students the flexibility to change their final project focus over time enables students to pursue meaningful scholarship related to their future specialties as their career interests evolve. In addition, it allows some students to participate in different aspects of serial short-term projects. One of the greatest challenges for students we noted was in identifying projects; this may be mitigated by directing students to focus on building translatable skills rather than focusing on specific geographic project locations, patient populations, or narrow topical areas.

We observed personal and professional growth of students as they faced challenges in project planning and implementation. The obstacles confronted by our students reflect real world challenges of global health work and provided student learning opportunities. A longitudinal 4-year capstone with defined progressive requirements exposes students to the challenges of global health work including mentor identification, ethical review of human subjects research, data collection delays, and lack of student availability at times due to competing priorities of exams and clerkships.

Capstones create an opportunity for dedicated mentorship

Rather than assigning project mentors, students are encouraged to pursue global health capstone projects with mentors they align with. Although every student is assigned an advisor to provide support for program completion, these advisors are not necessarily content experts in the student’s research area of interest. Sixty percent of GMED graduates ultimately completed a capstone project where they received dedicated topic-specific faculty mentorship. Completion of quality global health capstones could be enhanced with strategic efforts to create more structured mentorship and recruit more global health faculty.

The mentorship process for successful capstone development and completion can be improved by making sure that every student identifies a research mentor. We anticipate that dedicated mentors can improve the quality of the capstone experience and help the students create a stronger final scholarly product. We found that 26% of students presented capstone-related abstracts at conferences, and 14% were able to publish work related to their capstones. With dedicated project mentorship for every student, we aim to increase the number of students producing quality global health scholarship. For 2020, we added a requirement that students must submit a global health abstract to an external conference in the third year, and in 2019 we added the requirement that students submit a final written scholarly paper in addition to the oral presentations that were part of the original capstone requirements.

An additional aim of expanding our pool of capstone mentors is to increase multidisciplinary mentorship and collaboration among more varied medical specialty areas. When the program was founded, emergency medicine had strong representation among GMED program faculty, which may explain why almost a third of student capstones were in that specialty area. We have implemented a new structured mentorship program that provides wider faculty representation to ensure that students are provided necessary support and guidance regardless of the students’ chosen area of interest.

The capstone is synergistic with other modalities for teaching CUGH competencies

The global health capstone addresses, in part, each competency domain identified by CUGH, but the global health capstone is part of a larger curriculum that employs multiple educational modalities. Some CUGH competencies may be better achieved through these alternate methods, such as lectures, group discussion, and simulation-based exercises. We have also added additional didactic content to support student capstone success and competency attainment including skills-based workshops that focus on community engagement, global health research and scholarship, as well as global health policy and advocacy.

Many students were able to complete global health capstones that did not require international travel. Considering personal and financial restrictions that may affect students’ ability to travel, the global health capstone reinforces the view that global health can focus on transnational health issues addressing health equity, and one need not always travel to participate in effective global health work.

Limitations

This paper aimed to provide a description of the global health capstone including types of projects completed; however, it did not identify clear metrics for capstone success or evaluate student capstone projects. It identified how capstones may be used to teach global health competency domains but did not determine the effectiveness of this approach nor if there are particular domains that are better addressed by this educational tool. Finally, numerous challenges in the assessment of global health competencies have been identified [ 27 , 28 ]. Attempts have been made to develop measures such as surveys, structured instruments, and self-assessments in order to objectively assess global health competencies, but more research is needed in this area, including developing validated measures to assess global health capstones [ 12 , 29 , 30 ].

As the bar is raised on global health education beyond just international electives, students need integrated and formalized programming that enables them to develop skills and the ability to apply concepts in impactful global health endeavors. A structured global health capstone is one method for teaching global health competencies and preparing students for careers as global health practitioners and leaders. The implementation of a global health capstone in medical school is feasible and shows promise as an educational tool that may help teach essential global health core competencies as part of a broader curriculum. Well-defined criteria and expectations for global health capstones may improve scholarly quality and productivity, and strong mentorship is essential for successful capstone and program completion. Further refinement of the global health capstone may allow educators to help students build scholarly skills and target additional competency domains.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Global Medicine Program

University of Illinois College of Medicine

Consortium of Universities for Global Health

Low- and Middle-Income Country

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

mobile health

Nelson BD, Kasper J, Hibberd PL, Thea DM, Herlihy JM. Developing a career in Global Health: considerations for physicians-in-training and academic mentors. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(3):301–6.

Google Scholar

Khan OA, Guerrant R, Sanders J, et al. Global health education in U.S. Medical schools. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13:3.

Peluso MJ, Forrestel AK, Hafler JP, Rohrbaugh RM. Structured Global Health programs in U.S. medical schools: a web-based review of certificates, tracks, and concentrations. Acad Med. 2013;88(1):124–30.

Jogerst K, Callender B, Adams V, et al. Identifying Interprofessional Global Health competencies for 21st-century health professionals. Ann Glob Health. 2015;81(2):239–47.

Battat R, Seidman G, Chadi N, et al. Global health competencies and approaches in medical education: a literature review. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:94.

Gruppen LD, Mangrulkar RS, Kolars JC. The promise of competency-based education in the health professions for improving global health. Hum Resour Health. 2012;10:43.

Ablah E, Biberman DA, Weist EM, et al. Improving Global Health education: development of a Global Health competency model. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;90(3):560–5.

Wilson L, Callender B, Hall TL, Jogerst K, Torres H, Velji A. Identifying global health competencies to prepare 21st century global health professionals: report from the global health competency subcommittee of the consortium of universities for global health. J Law Med Ethics. 2014;42(2):26–31.

Pfeiffer J, Beschta J, Hohl S, Gloyd S, Hagopian A, Wasserheit J. Competency-based curricula to transform Global Health: redesign with the end in mind. Acad Med. 2013;88:1.

Global Health Education Consortium. Global health essential core competencies. https://globalhealtheducation.org/resources_OLD/Documents/Primarily%20For%20Faculty/Basic%20Core_Competencies_Final%202010.pdf . Published 2010. Accessed 13 June 2019.

Teichholtz S, Kreniske JS, Morrison Z, Shack AR, Dwolatzky T. Teaching corner: an undergraduate medical education program comprehensively integrating Global Health and Global Health ethics as Core curricula. J Bioeth Inq. 2015;12(1):51–5.

Gruner D, Pottie K, Archibald D, et al. Introducing global health into the undergraduate medical school curriculum using an e-learning program: a mixed method pilot study. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:142.

Logar T, Le P, Harrison JD, Glass M. Teaching corner: "first do no harm": teaching global health ethics to medical trainees through experiential learning. J Bioeth Inq. 2015;12(1):69–78.

Bertelsen NS, DallaPiazza M, Hopkins MA, Ogedegbe G. Teaching global health with simulations and case discussions in a medical student selective. Glob Health. 2015;11:28.

Thompson MJ, Huntington MK, Hunt DD, Pinsky LE, Brodie JJ. Educational effects of international health electives on U.S. and Canadian medical students and residents: a literature review. Acad Med. 2003;78(3):342–7.

Watson DA, Cooling N, Woolley IJ. Healthy, safe and effective international medical student electives: a systematic review and recommendations for program coordinators. Trop Dis Travel Med Vaccines. 2019;5:4.

Melby MK, Loh LC, Evert J, et al. Beyond medical “missions” to impact-driven short-term experiences in Global Health (STEGHs): ethical principles to optimize community benefit and learner experience. Acad Med. 2016;91(5):633–8.

DeCamp J, Lehmann LS, Jaeel P, et al. Ethical obligations regarding short-term Global Health clinical experiences: an American College of Physicians Position Paper. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(9):651–7.

Gourley DR, Vaidya VA, Hufstader MA, Ray MD, Chisholm-Burns MA. An international capstone experience for pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(3):50.

Oden M, Mirabal Y, Epstein M, Richards-Kortum R. Engaging undergraduates to solve global health challenges: a new approach based on bioengineering design. Ann Biomed Eng. 2010;38(9):3031–41.

Hauhart RC, Grahe JE. The undergraduate capstone course in the social sciences: results from a regional survey. Teach Sociol. 2010;38(1):4–17.

Henderson A. Growing by getting their hands dirty: meaningful research transforms students. J Econ Educ. 2016;47(3):241–57.

Magimairaj BM, McDaniel K. A survey of undergraduate capstone course objectives in communication sciences and disorders. J Allied Health. 2017;46(4):e59–65.

University of Illinois Center for Global Health. GMED Curriculum. Retrieved from: https://globalhealth.uic.edu/education/gmed-program/gmed-curriculum . Accessed 30 Jan 2020.

Koplan JP, Bond TC, Merson MH, et al. Towards a common definition of global health. Lancet. 2009;373(9679):1993–5.

Pitt MB, Slusher TM, Howard CR, et al. Pediatric resident academic projects while on Global Health electives: ten years of experience at the University of Minnesota. Acad Med. 2017;92(7):998–1005.

Eichbaum Q. The problem with competencies in Global Health education. Acad Med. 2015;90(4):414–7.

Eichbaum Q. Acquired and participatory competencies in health professions education: definition and assessment in Global Health. Acad Med. 2017;92(4):468–74.

Veras M, Pottie K, Welch V, et al. Reliability and validity of a new survey to assess Global Health competencies of health professionals. Glob J Health Sci. 2013;5(1):13.

Margolis CZ, Rohrbaugh RM, Tsang L, et al. Student reflection papers on a global clinical experience: a qualitative study. Ann Glob Health. 2017;83(2):333–8.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the GMED students who have enthusiastically participated in the program, including completing the global health capstone projects reviewed in this article.

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Illinois Chicago Center for Global Health, 1940 W. Taylor St., 2nd floor, Chicago, IL, 60612, USA

Stacey Chamberlain, Nicole Gonzalez, Marcia Edison, Janet Lin & Stevan Weine

Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Humanitarian Initiative, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA

Valerie Dobiesz

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

SC contributed to the study design, data analysis, and writing of the manuscript. NG contributed to the study design, data analysis, and writing of the manuscript. VD contributed to the study design, data analysis, and editing/revision of the manuscript. ME contributed to the study design, data analysis, and editing/revision of the manuscript. JL contributed to the study design, data analysis, and editing/revision of the manuscript. SW contributed to the study design and editing/revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Stacey Chamberlain is Associate Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine, and Director of Academic Programs, University of Illinois Chicago Center for Global Health, Chicago, IL.

Nicole Gonzalez is Research Specialist, University of Illinois Chicago Center for Global Health, Chicago, IL.

Valerie Dobiesz is Assistant Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine, and Director of Internal Programs STRATUS Center for Medical Simulation, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Faculty Harvard Humanitarian Initiative, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Marcia Edison is Assistant Professor, Department of Medical Education, and Director of Research and Evaluation, University of Illinois Chicago Center for Global Health, Chicago, IL.

Janet Lin is Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine, and Director of Health Systems Development, University of Illinois Chicago Center for Global Health, Chicago, IL.

Stevan Weine is Professor, Department of Psychiatry, and Director of Global Medicine, University of Illinois Chicago Center for Global Health, Chicago, IL.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Stacey Chamberlain .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests, additional information, publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Chamberlain, S., Gonzalez, N., Dobiesz, V. et al. A global health capstone: an innovative educational approach in a competency-based curriculum for medical students. BMC Med Educ 20 , 159 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02070-z

Download citation

Received : 23 July 2019

Accepted : 11 May 2020

Published : 19 May 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02070-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Global health

- Medical education

- Competencies

BMC Medical Education

ISSN: 1472-6920

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Public Health

- PMC10213715

MPH Capstone experiences: promising practices and lessons learned

Associated data.

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: The data were collected for internal program evaluation. We did not request permission at the time of data collection to disseminate these raw data. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to ude.cnu@deirfdnal .

To ensure workforce readiness, graduate-level public health training programs must prepare students to collaborate with communities on improving public health practice and tools. The Council on Education for Public Health (CEPH) requires Master of Public Health (MPH) students to complete an Integrative Learning Experience (ILE) at the end of their program of study that yields a high-quality written product demonstrating synthesis of competencies. CEPH suggests written products ideally be “developed and delivered in a manner that is useful to external stakeholders, such as non-profit or governmental organizations.” However, there are limited examples of the ILE pedagogies and practices most likely to yield mutual benefit for students and community partners. To address this gap, we describe a community-led, year-long, group-based ILE for MPH students, called Capstone. This service-learning course aims to (1) increase capacity of students and partner organizations to address public health issues and promote health equity; (2) create new or improved public health resources, programs, services, and policies that promote health equity; (3) enhance student preparedness and marketability for careers in public health; and (4) strengthen campus-community partnerships. Since 2009, 127 Capstone teams affiliated with the Department of Health Behavior at the Gillings School of Global Public Health at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill have worked with seventy-nine partner organizations to provide over 103,000 h of in-kind service and produce 635 unique products or “deliverables.” This paper describes key promising practices of Capstone, specifically its staffing model; approach to project recruitment, selection, and matching; course format; and assignments. Using course evaluation data, we summarize student and community partner outcomes. Next, we share lessons learned from 13 years of program implementation and future directions for continuing to maximize student and community partner benefits. Finally, we provide recommendations for other programs interested in replicating the Capstone model.

Introduction

Responding to public health crises like the COVID-19 pandemic requires a public health workforce skilled in community partnership ( 1 , 2 ). Schools and programs of public health are thus charged with designing community-engaged learning experiences while also satisfying accreditation criteria ( 3 ). The accrediting body for schools and programs of public health, the Council on Education for Public Health (CEPH), requires Master of Public Health (MPH) students to complete an Integrative Learning Experience (ILE), which represents a culminating experience near the end of their program of study. The ILE must yield a high-quality written product (e.g., “program evaluation report, training manual, policy statement, take-home comprehensive essay exam, legislative testimony with accompanying supporting research, etc.”) that demonstrates synthesis of a set of competencies ( 2 ). Such products may be generated from practice-based projects, essay-based comprehensive exams, capstone programs, or integrative seminars ( 2 ). CEPH guidelines suggest ILE written products ideally be “developed and delivered in a manner that is useful to external stakeholders, such as non-profit or governmental organizations” ( 2 ).

Within this paper, we describe promising practices employed within a community-led, group-based, year-long, critical service-learning course, called Capstone, for MPH students within the Department of Health Behavior at the Gillings School of Global Public Health (Gillings) at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC-CH) ( 4 ). We explain the specifics of Capstone's staffing model; project recruitment, selection, and matching processes; course format; and assignments, all of which are designed to promote mutual benefit for students and community partners. Using internal and school-level course evaluations, we present findings on student and community partner outcomes. Next, we reflect on lessons learned from 13 years of implementation experience and suggest future directions for Capstone programming. Finally, we share recommendations for other programs interested in replicating Capstone. We hope the information presented in this paper will benefit other programs interested in ILEs that have mutual benefit for students and community partners.

Pedagogical framework

By design, Capstone is a critical service-learning course. Service-learning pedagogies and practices vary widely. Essential elements of service-learning include community-engaged activities tied to learning goals and ongoing reflection ( 5 – 7 ). The literature documents wide-ranging benefits students gain from service-learning programs such as improved critical thinking skills as well as stronger leadership, communication, and interpersonal skills ( 5 , 8 ). Participation in service-learning courses promotes program satisfaction ( 9 ), academic achievement ( 5 , 8 – 10 ), and job marketability ( 9 , 11 ) among students. Finally, service-learning experiences enhance students' civic engagement ( 2 , 4 , 7 ), cultural awareness, and practice of cultural humility ( 8 , 12 ).

Despite these benefits, service-learning implementation challenges are well documented. Service-learning courses require significant resources to cover program expenses and staffing dedicated to developing and maintaining community partner relationships ( 7 , 12 – 15 ). In addition, the academic calendar may not align with community partners' timelines ( 5 , 14 , 16 ). Students and community partners have additional responsibilities and competing priorities outside coursework, thus creating variable levels of engagement across program participants ( 13 – 15 , 17 , 18 ). In cases where students have nascent project management skills and limited professional experience ( 9 , 10 , 13 ), it can be difficult to achieve mutual benefits among students and community partners.

A prominent debate within the field is the degree to which service-learning projects perpetuate the status quo or facilitate social change. Specifically, researchers question which elements of service-learning best create the conditions for student learning and positive community transformation ( 5 , 19 – 21 ). To provide a framework for this debate, Mitchell ( 5 ) differentiates between “traditional service-learning” and “critical service-learning.” Traditional service-learning is often critiqued for prioritizing student learning needs over benefits to the community ( 5 , 21 ). In contrast, critical service-learning is explicitly committed to social justice ( 5 ). Key elements of a critical service-learning approach include: (1) redistributing power among members of the partnership; (2) building authentic relationships (i.e., those characterized by connection, mutual benefits, prolonged engagement, trust, and solidarity); and (3) working from a social change perspective ( 5 ).

Most service-learning program descriptions within public health training do not reference either a traditional or critical service-learning framework ( 8 , 9 , 11 , 13 , 14 , 22 , 23 ). Several published programs align with a traditional service-learning model, due to the exclusive focus on student benefits and the absence of an explicit commitment to power sharing, authentic partnerships, or social change. For example, Schober et al. ( 24 ) underscore service-learning as an effective means to train a younger workforce to address complex public health issues. Gupta et al. ( 8 ) describe the importance of self-reflection activities for personal growth and skill development, structured within a service-learning program for undergraduate students enrolled in a community nutrition course. While these courses contain many of the best practices in service-learning, including reflection, they discuss student outcomes without promoting or evaluating social change ( 6 ).

The literature also cites programs and courses that include elements of critical service-learning but do not use critical service-learning terminology. For example, a service-learning program at the University of Connecticut outlines how students contribute to structural changes and social progress through policy development and implementation as part of their applied practice experience, which culminates with a presentation to the state legislature ( 23 ). Additionally, Sabo et al. ( 12 ) describe a service-learning course at the University of Arizona oriented toward social justice, as the course is “modeled on the reduction of health disparities through exploration, reflection, and action on the social determinants of health” through strong community-academic partnerships across urban, rural, and indigenous settings. These examples highlight commitment to social progress, community impact, and equitable collaboration without overtly applying the language of critical service-learning.

A small number of service-learning practitioners define their programs explicitly as critical-service learning. Mackenzie et al. ( 13 ) document the benefits of a critical service-learning experience for undergraduate public health students, endorsing it as a “feasible, sustainable” high-impact practice. In their model, students partner with community organizations to address social determinants of health; analyze and challenge power dynamics and systems of oppression; and gain skills. As evidence of power sharing and social change, the authors document that communities have continued their partnerships with the university due to the expansive reach and impact of their collaborations. Authentic relationships were also developed as students gained a stronger sense of commitment to communities. Derreth and Wear ( 25 ) describe the transition to an online critical service-learning course as universities grappled with changing instructional formats with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. In this course, public health students collaborated with Baltimore residents to create evaluation tools while participating in reflective activities. As evidence of critical service-learning, they documented students' changed perspectives, ongoing commitment to collaborate with residents after the course, and development of strong connections with faculty. These courses show the possibilities of critical service-learning ILEs. Detailed descriptions of program structures are needed for interested faculty to replicate best practices. To assist others with adopting or adapting elements of critical service-learning ILEs, this paper provides specifics about Capstone programming.

Learning environment

Program overview.

Community-Led Capstone Project: Part I and II (Capstone) is a graduate-level course situated within UNC-CH's Gillings' Department of Health Behavior (Department). The Department developed Capstone in response to faculty concerns about the variable investment in and quality of master's papers ( 26 ), coupled with a desire to design a practice-based culminating experience driven by community partners' needs, interests, and concerns. Capstone satisfies CEPH ILE requirements and serves as the substitute for UNC-CH's master's thesis requirement for students in the Health Behavior (HB) and Health Equity, Social Justice, and Human Rights (EQUITY) MPH concentrations. The overwhelming majority of students in these two concentrations are full-time residential students pursuing an MPH within a two-year time frame, though there are a few students who are enrolled in a dual degree program to earn their MPH alongside a Master of Social Work (MSW) or Master of City and Regional Planning (MCRP) within 3 years.

During this year-long course, which occurs during the second year of the MPH program, students synthesize and apply their MPH training to community-designed public health projects. Supplementary material A , B include a list of HB and EQUITY required courses and their sequencing. The specific competencies applied and assessed during Capstone are listed in Supplementary material C . Each team of four to five Capstone students works with a partner organization and its constituents to produce a set of four to six deliverables (i.e., tangible products). Deliverables are based on the partner organization's self-identified needs. This community-led approach prioritizes partners' interests and gives students an opportunity to do applied public health work on a range of topics with a variety of organization types. Figure 1 details the tasks and timelines entailed in this programming. Table 1 presents information from selected projects that showcase the range of partner organizations, activities, and deliverables present in Capstone. Capstone's specific objectives are to (1) increase capacity among students and partner organizations to address public health issues and promote health equity; (2) create new or improved public health resources, programs, services, and policies that advance health equity; (3) enhance student preparedness and marketability for public health careers; and (4) strengthen campus-community partnerships.

Gantt chart illustrating major Capstone activities and timeline.

Sample projects.

Personnel and resources

Capstone involves numerous constituents and requires dedicated resources. Each partner organization is represented by one or two preceptors (i.e., main points of contact from the partner organization) who provide a vision for, direct, and supervise the project work. Preceptors spend 2–4 h per week meeting with students, providing guidance on the work, and reviewing deliverables. Student teams are responsible for managing Capstone relationships, processes, and tasks and producing deliverables that enhance their skillsets while meeting their partner organization's needs. They are expected to spend 6–9 h per week, outside of class time, on Capstone. One faculty adviser per project provides technical expertise and ensures that each team's project deliverables meet UNC-CH's master's thesis substitute and CEPH ILE requirements. Faculty advisers spend 30 min to an hour a week providing feedback and guidance on the project work. Advising a Capstone team every other year is a service expectation for Department faculty. The teaching team, which is comprised of course instructor(s) and teaching assistants (TAs), recruits the partner organizations and oversees and supports the Capstone experience. Each instructor manages ten to eleven teams (typically between forty and fifty students) and receives coverage equal to twenty percent full-time equivalent per semester. TAs, who are HB or EQUITY MPH alumni and/or HB doctoral students, each work with five to six teams and are expected to work 18 h a week on Capstone. TAs provide feedback on draft deliverables, direct students to resources, and help problem solve. Departmental administrative staff provide additional support to coordinate expenses associated with the program such as project-related travel, equipment, services (e.g., transcription, interpretation, translation), books, software, incentives, postage, and other costs. Capstone students pay a one-time $600 field fee to cover a portion of the expenses associated with Capstone. This fee was approved by the University and is paid when a student enrolls in the first semester of the course.

Project recruitment, selection, and matching

Recruitment.

The process of setting up Capstone projects takes 9 months of advance planning (see Figure 1 ). The Capstone teaching team solicits project proposals in December for the upcoming academic year. They send email solicitations with Capstone overview information ( Supplementary material D ) and the project proposal form ( Supplementary material E ) to current and former Capstone partner organizations, hosts of other experiential education experiences, and department listservs. The Capstone teaching team encourages recipients to share the solicitation information with their networks. Prospective partners' first step is to have an informational interview with a Capstone instructor to discuss their project ideas and to receive coaching on elements of successful proposals. These interviews are also an opportunity for the teaching team to assess an organization's capacity to support a student team and gain insights on the prospective preceptors' communication, work, and leadership styles. The teaching team invites prospective partners to submit draft proposals for their review prior to the proposal deadline. Prospective partners submit their finalized project proposals and a letter of support from their leadership to the teaching team by email in early February.

The teaching team typically receives twenty project proposals. To determine which projects will be presented to incoming Capstone students, a committee consisting of the teaching team and student representatives from the current Capstone class reviews and scores proposals based on the criteria listed in Table 2 . Reviewers score each criterion on a scale of one through five with one being the lowest score and five being the highest score. The fifteen community partners with the highest scoring proposals are invited to share their ideas with students via a recorded seven-minute project overview presentation.

Project selection criteria.

Incoming Capstone students have 1 week in March to review the proposal materials and rank their top five project preferences. Based on student rankings, the teaching team assembles project teams using the following guiding principles: (1) give as many students as possible their top-ranked project; (2) promote diversity of concentrations and experience levels within student teams; and (3) ensure the number of students per team is appropriate for the proposed scope of work. Once the student teams are assembled, the teaching team matches faculty advisers to projects based on faculty's interests and expertise. The teaching team announces final team composition in early April. The course instructor(s) facilitates an initial meeting with each student team, their preceptor(s), and their faculty adviser in May to build community, clarify expectations, and orient the student team to their project work and partner organization. Project work formally begins in August of the following academic year.

Course format

Capstone spans the fall and spring semesters (fifteen weeks per term) and is three credits per term. To help students, preceptors, and faculty advisers become familiar with expectations for Capstone, the teaching team reserves the first 4 weeks of the fall semester for onboarding. As part of the onboarding process, each team cocreates a team charter ( Supplementary material F ) to promote authentic relationships between students and their community partners and to clarify expectations for working together. They also produce a workplan ( Supplementary material G ), which elaborates on the partner's project proposal, to outline the team's scope of work. After the onboarding weeks, the teaching team meets with each student team during class three times per semester to receive project updates and provide support. The teaching team facilitates two whole-class reflection sessions per semester to help students make meaning of their experiences. All other Capstone class sessions are protected time for student teams to meet and work on their projects.

Course assignments

Capstone assignments are designed to ensure a mutually beneficial experience for students and community partners. They are also intended to facilitate critical reflection, yield high-quality written products, assess synthesis of selected competencies, and evaluate how students steward the relationships, processes, and tasks associated with their projects. To share power and collect their unique perspectives, preceptors and faculty advisers participate in the grading process. Tables 3 , ,4 4 summarize course assignments, their descriptions, whether they are completed and assessed at the individual or group level, and the party responsible for assessing the assignment.

Capstone assignments for the fall semester.

TT, Teaching Team; P, Preceptor; FA, Faculty Adviser.

Capstone assignments for the spring semester.

Program evaluation

This study was exempted by UNC Chapel Hill's Institutional Review Board (IRB 21-0510) as it fell under the exemption category of “educational setting,” which includes research on instructional approaches and their effectiveness. To abstract and analyze data on the number of students who have completed Capstone, hours they dedicated to Capstone activities, and deliverables they produced, two authors referenced course records starting in 2009. The teaching team collects students' and preceptors' perspectives on Capstone through mid- and end-of-semester evaluations using Qualtrics. Gillings administers end-of-semester course evaluations that provide additional insights into student outcomes.

Core aspects of Capstone (e.g., program aims and our staffing model) have remained constant over the past 13 years. However, a variety of lessons learned and external conditions have led to program changes. Use of class time and project recruitment, selection, and matching processes have evolved to further promote health equity and maximize mutual student and community partner benefit. The EQUITY concentration joined Capstone in 2020, which led to changes in team composition. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic necessitated a transition from in-person to a remote course format in academic years 2020 and 2021, introducing the opportunity to work with organizations across the nation.

To present qualitative findings that reflect our most current programming, two authors analyzed data from academic years 2020 and 2021. Ninety-eight students and twenty-two preceptors participated in Capstone during that time. The teaching team received a 100 percent response rate to their mid and end-of semester evaluations completed by students and preceptors and a seventy-two percent response rate to the Gillings-administered student course evaluations during academic years 2020 and 2021.

To identify key outcomes for students and preceptors, two authors completed a thematic analysis of evaluation responses ( 27 , 28 ). For students, they analyzed eighty-eight qualitative responses to the Gillings' course evaluation question, “What will you take away from this course?” Next, the two authors familiarized themselves with the data and inductively created a thematic codebook. To ensure consistent code use, they simultaneously coded approximately twenty-five percent of transcripts, coded remaining transcripts separately, and flagged any transcripts that required further review. To identify key preceptor outcomes, the two authors analyzed the twenty-two responses to the spring end-of-semester evaluation question, “Please describe how, if at all, your organization benefited from hosting a Capstone team.” They reviewed the responses to inductively create a codebook and then worked together to apply codes to all quotations to identify thematic groups.

Student outcomes

Since its inception in 2009, 574 students across 127 teams have completed the Capstone program, provided over 103,000 h of in-kind service, and produced more than 635 deliverables with our partner organizations. Between 2020–2022, ninety-eight students completed the current version of Capstone, provided 35,280 h of in-kind service, and produced eighty deliverables. Through our thematic analysis of course evaluation data, we identified two overarching themes for student outcomes: skill development and satisfaction.

Skill development, students' greatest takeaway from Capstone, was reflected in fifty-three percent ( n = 47) of students' qualitative evaluation responses. Students directly named interpersonal skills (e.g., communication, teamwork, collaboration, conflict management, facilitation, community engagement, coalition building) the most. They also commented on acquisition of technical skills (e.g., project management; content development; and data collection, analysis, and reporting). In most cases, students named a mix of skills in their responses. For example, one student said they will take away:

Skills developed on the project, including survey design and implementation as well as strategies for engaging with community advisory board authentically and successfully. Shared skills among team will stick with me as well – project management, inter–team communication, strategies for setting clear expectations and holding each other accountable.

Skill development helps achieve Capstone's course aims of increasing students' capacity to address public health issues and promote health equity while enhancing their preparedness and marketability for public health careers.

Twenty-four students commented on their satisfaction with the experience when sharing key takeaways. Seven students expressed dissatisfaction, primarily with course assignments, while seventeen others remarked on their satisfaction with the experience, particularly the applied format of the course. For example, one student shared,

This Capstone project really was special. Having a community partner that demonstrated how helpful these projects would be and work with us to shape the deliverables was such a unique process. I wish we had more community–focused classes like this one.

In alignment with Capstone's objective of strengthened campus-community partnerships and CEPH ILE goals, these Capstone partnerships afford students the opportunity to see the impacts of their learning and create meaningful work that benefits external constituents.

Community partner outcomes

Over the past 13 years, we have partnered with seventy-nine organizations representing a variety of sectors including healthcare, social services, education, and government. Twenty-five (31.6%) of our partner organizations have hosted multiple Capstone teams. Based on the twenty-two preceptor responses analyzed for this paper, two authors identified four major themes within community partner benefits: deliverable utility, enhanced capacity, broad impacts, and more inclusive processes. Sixteen (72.7%) preceptors said that they benefited from the deliverables (e.g., toolkit, communication tool, datasets, evaluation plan, report, oral history products, protocols, presentation, report, curriculum, manuscript, engagement plan) produced by their team. These findings reflect Capstone's course aim of creating new or improved public health resources, programs, services, and policies.

Fifty-seven percent ( n = 12) of preceptors noted that project outcomes would not have been possible without the support of a Capstone team. The resources teams developed increased partner organizations' capacity to further their work. For example, a preceptor shared:

The Capstone team provided us with SO many hours of highly skilled person power that we would not otherwise have had. We now have a draft of a thorough and high quality [toolkit], which I don't think could have been created without their labor, given the resource constraints of [our organization]. This toolkit will serve as a tool to start conversations with many […] stakeholders in the future. I think it will also serve as a model for other states.

Not only can students' in-kind service and the work they produce help increase the capacity of our partner organizations, but also the Capstone project work can have long-term and far-reaching impacts for public health practice at large. Indeed, preceptors ( n = 8) reported impacts that extend beyond the partner organization. For example, another preceptor noted,

[Our organization] will use the presentation and report that the Capstone team produced for the next decade. Not only will [our organization] benefit from advancing our strategic priorities and deepening our partnerships, but we believe this report will be used by other agencies across the county to advance behavioral health priorities in need of support.

This is an example of how Capstone can yield new and improved public health resources, programs, services, and policies that have lasting impacts beyond those directly benefiting our partner organizations.

A final theme that emerged was organizations' increased ability to implement more inclusive processes. Four preceptors commented on expanded commitment to equity initiatives as illustrated by the following quote:

The work the team did for [our organization] is work that we've talked about doing for several years - but we never had the time. The protocols are important for injured children, so we're grateful for the team's work. We also have never addressed social equity as a group. Working with this team has prompted us to take a look at our practices. The evaluation plan the students developed will provide a mechanism for us to assess and trend our implementation of the protocols and our efforts to reduce inequities in trauma care.

This example demonstrates how Capstone's commitment to working from a social change orientation can impact our partner organizations' cultures. Overall, these findings illustrate the myriad community partner benefits present within Capstone.

These results show that Capstone mutually benefits community partners and students. Overall, students gained skills in collaborating with communities and contributed to collective capacity to improve public health practice and tools for promoting health equity. Our finding that skill development was a key student outcome aligns with Mackenzie et al.'s ( 13 ) and Gupta et al.'s ( 8 ) evaluations of similar service-learning courses. Among skills developed, both studies cited teamwork and professional development skills as key components ( 8 , 13 ). Mackenzie et al. ( 13 ), Derreth and Wear ( 25 ), and Sabo et al. ( 12 ) also report additional student outcomes that were not explicitly measured in our evaluation, including a deeper commitment to work with local communities, a deeper commitment to engaged scholarship, and stronger relationships with faculty.

In our evaluation, community partners benefitted through useful deliverables, enhanced capacity to do more public health work, impacts beyond the scope of the project, and more inclusive and equitable processes. Like our study, Gregorio et al. ( 23 ) found that their students' work products were very useful. Moreover, the Mackenzie et al. ( 13 ) study cited that students were able to offer additional capacity to organizations by “extending the[ir] reach,” which reinforced our main findings of enhanced capacity and impacts beyond the scope of the project. While not all service-learning course evaluation studies included data from community partners, our results aligned with those that did.

Lessons learned

After 13 years, we have identified several lessons learned about implementing a critical service-learning ILE. First, despite proactive planning efforts, the teaching team has learned to expect challenges related to project scope and relationships. The solicitation and refinement of projects and partnerships starts 9 months before the beginning of Capstone. Through extended individualized support and engagement, the teaching team hopes to build trust with community partners and collaborate in shaping and strengthening their project proposals. While there are benefits of this level of engagement, no amount of planning completely insulates projects from the unforeseen challenges of community-engaged work. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic impacted how Capstone could engage with community partners, their priorities, and their staffing. In particular, preceptor turnover creates numerous challenges for team morale and project ownership, satisfaction, and impact.

Second, Capstone course assignments are designed to maximize positive experiences for students and community partners and to uphold the principles of critical service-learning, but students are often frustrated with them. The teaching team refers to the workplan and team charter as the “guardrails” of the Capstone. They exist to clarify expectations, promote power sharing and authentic relationships, and reinforce Capstone's commitment to social change. The teaching team has observed that teams who invest deeply in these documents are the least likely to encounter significant interpersonal and logistical setbacks during the experience. Despite the teaching team's messaging about the importance of these structures for mutually beneficial experiences, students routinely assert that the start of Capstone contains too much “administrative” work. While the teaching team continues to respect and incorporate students' critical feedback, they have learned to expect a certain amount of student dissatisfaction at the start of the experience.