You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Health & Nursing

Courses and certificates.

- Bachelor's Degrees

- View all Business Bachelor's Degrees

- Business Management – B.S. Business Administration

- Healthcare Administration – B.S.

- Human Resource Management – B.S. Business Administration

- Information Technology Management – B.S. Business Administration

- Marketing – B.S. Business Administration

- Accounting – B.S. Business Administration

- Finance – B.S.

- Supply Chain and Operations Management – B.S.

- Accelerated Information Technology Bachelor's and Master's Degree (from the School of Technology)

- Health Information Management – B.S. (from the Leavitt School of Health)

Master's Degrees

- View all Business Master's Degrees

- Master of Business Administration (MBA)

- MBA Information Technology Management

- MBA Healthcare Management

- Management and Leadership – M.S.

- Accounting – M.S.

- Marketing – M.S.

- Human Resource Management – M.S.

- Master of Healthcare Administration (from the Leavitt School of Health)

- Data Analytics – M.S. (from the School of Technology)

- Information Technology Management – M.S. (from the School of Technology)

- Education Technology and Instructional Design – M.Ed. (from the School of Education)

Certificates

- View all Business Degrees

Bachelor's Preparing For Licensure

- View all Education Bachelor's Degrees

- Elementary Education – B.A.

- Special Education and Elementary Education (Dual Licensure) – B.A.

- Special Education (Mild-to-Moderate) – B.A.

- Mathematics Education (Middle Grades) – B.S.

- Mathematics Education (Secondary)– B.S.

- Science Education (Middle Grades) – B.S.

- Science Education (Secondary Chemistry) – B.S.

- Science Education (Secondary Physics) – B.S.

- Science Education (Secondary Biological Sciences) – B.S.

- Science Education (Secondary Earth Science)– B.S.

- View all Education Degrees

Bachelor of Arts in Education Degrees

- Educational Studies – B.A.

Master of Science in Education Degrees

- View all Education Master's Degrees

- Curriculum and Instruction – M.S.

- Educational Leadership – M.S.

- Education Technology and Instructional Design – M.Ed.

Master's Preparing for Licensure

- Teaching, Elementary Education – M.A.

- Teaching, English Education (Secondary) – M.A.

- Teaching, Mathematics Education (Middle Grades) – M.A.

- Teaching, Mathematics Education (Secondary) – M.A.

- Teaching, Science Education (Secondary) – M.A.

- Teaching, Special Education (K-12) – M.A.

Licensure Information

- State Teaching Licensure Information

Master's Degrees for Teachers

- Mathematics Education (K-6) – M.A.

- Mathematics Education (Middle Grade) – M.A.

- Mathematics Education (Secondary) – M.A.

- English Language Learning (PreK-12) – M.A.

- Endorsement Preparation Program, English Language Learning (PreK-12)

- Science Education (Middle Grades) – M.A.

- Science Education (Secondary Chemistry) – M.A.

- Science Education (Secondary Physics) – M.A.

- Science Education (Secondary Biological Sciences) – M.A.

- Science Education (Secondary Earth Science)– M.A.

- View all Technology Bachelor's Degrees

- Cloud Computing – B.S.

- Computer Science – B.S.

- Cybersecurity and Information Assurance – B.S.

- Data Analytics – B.S.

- Information Technology – B.S.

- Network Engineering and Security – B.S.

- Software Engineering – B.S.

- Accelerated Information Technology Bachelor's and Master's Degree

- Information Technology Management – B.S. Business Administration (from the School of Business)

- View all Technology Master's Degrees

- Cybersecurity and Information Assurance – M.S.

- Data Analytics – M.S.

- Information Technology Management – M.S.

- MBA Information Technology Management (from the School of Business)

- Full Stack Engineering

- Web Application Deployment and Support

- Front End Web Development

- Back End Web Development

3rd Party Certifications

- IT Certifications Included in WGU Degrees

- View all Technology Degrees

- View all Health & Nursing Bachelor's Degrees

- Nursing (RN-to-BSN online) – B.S.

- Nursing (Prelicensure) – B.S. (Available in select states)

- Health Information Management – B.S.

- Health and Human Services – B.S.

- Psychology – B.S.

- Health Science – B.S.

- Healthcare Administration – B.S. (from the School of Business)

- View all Nursing Post-Master's Certificates

- Nursing Education—Post-Master's Certificate

- Nursing Leadership and Management—Post-Master's Certificate

- Family Nurse Practitioner—Post-Master's Certificate

- Psychiatric Mental Health Nurse Practitioner —Post-Master's Certificate

- View all Health & Nursing Degrees

- View all Nursing & Health Master's Degrees

- Nursing – Education (BSN-to-MSN Program) – M.S.

- Nursing – Leadership and Management (BSN-to-MSN Program) – M.S.

- Nursing – Nursing Informatics (BSN-to-MSN Program) – M.S.

- Nursing – Family Nurse Practitioner (BSN-to-MSN Program) – M.S. (Available in select states)

- Nursing – Psychiatric Mental Health Nurse Practitioner (BSN-to-MSN Program) – M.S. (Available in select states)

- Nursing – Education (RN-to-MSN Program) – M.S.

- Nursing – Leadership and Management (RN-to-MSN Program) – M.S.

- Nursing – Nursing Informatics (RN-to-MSN Program) – M.S.

- Master of Healthcare Administration

- MBA Healthcare Management (from the School of Business)

- Business Leadership (with the School of Business)

- Supply Chain (with the School of Business)

- Back End Web Development (with the School of Technology)

- Front End Web Development (with the School of Technology)

- Web Application Deployment and Support (with the School of Technology)

- Full Stack Engineering (with the School of Technology)

- Single Courses

- Course Bundles

Apply for Admission

Admission requirements.

- New Students

- WGU Returning Graduates

- WGU Readmission

- Enrollment Checklist

- Accessibility

- Accommodation Request

- School of Education Admission Requirements

- School of Business Admission Requirements

- School of Technology Admission Requirements

- Leavitt School of Health Admission Requirements

Additional Requirements

- Computer Requirements

- No Standardized Testing

- Clinical and Student Teaching Information

Transferring

- FAQs about Transferring

- Transfer to WGU

- Transferrable Certifications

- Request WGU Transcripts

- International Transfer Credit

- Tuition and Fees

- Financial Aid

- Scholarships

Other Ways to Pay for School

- Tuition—School of Business

- Tuition—School of Education

- Tuition—School of Technology

- Tuition—Leavitt School of Health

- Your Financial Obligations

- Tuition Comparison

- Applying for Financial Aid

- State Grants

- Consumer Information Guide

- Responsible Borrowing Initiative

- Higher Education Relief Fund

FAFSA Support

- Net Price Calculator

- FAFSA Simplification

- See All Scholarships

- Military Scholarships

- State Scholarships

- Scholarship FAQs

Payment Options

- Payment Plans

- Corporate Reimbursement

- Current Student Hardship Assistance

- Military Tuition Assistance

WGU Experience

- How You'll Learn

- Scheduling/Assessments

- Accreditation

- Student Support/Faculty

- Military Students

- Part-Time Options

- Virtual Military Education Resource Center

- Student Outcomes

- Return on Investment

- Students and Gradutes

- Career Growth

- Student Resources

- Communities

- Testimonials

- Career Guides

- Skills Guides

- Online Degrees

- All Degrees

- Explore Your Options

Admissions & Transfers

- Admissions Overview

Tuition & Financial Aid

Student Success

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Military and Veterans

- Commencement

- Careers at WGU

- Advancement & Giving

- Partnering with WGU

What Is Humanistic Learning Theory in Education?

- Professional Education

- See More Tags

Good teachers are always looking for ways to improve their methods to help students thrive in their classroom. Different learning theories and techniques help teachers connect with different students based on their learning style and abilities. Teaching strategies that are student-centered often have great success in helping students learn and grow better. Learner-centered approaches place the student as the authority in the educational setting, helping ensure that they are the focus of education and are in control of their learning to an extent.

The idea of student-centered learning is an example of the humanistic learning theory in action. It’s valuable for current and aspiring educators alike to learn about student-centered education and other humanistic approaches to use in their classroom. These approaches can be vital in helping students truly learn and succeed in their education. Learn more about the humanistic learning theory and discover how it can be implemented in the classroom.

The humanistic theory in education.

In history humanistic psychology is an outlook or system of thought that focuses on human beings rather than supernatural or divine insight. This system stresses that human beings are inherently good, and that basic needs are vital to human behaviors. Humanistic psychology also focuses on finding rational ways to solve these human problems. At its root, the psychology of humanism focuses on human virtue. It has been an important movement throughout history, from Greek and Latin roots to Renaissance and now modern revivals.

This theory and approach in education takes root in humanistic psychology, with the key concepts focusing on the idea that children are good at the core and that education should focus on rational ways to teach the “whole” child. This theory states that the student is the authority on how they learn, and that all of their needs should be met in order for them to learn well. For example, a student who is hungry won’t have as much attention to give to learning. So schools offer meals to students so that need is met, and they can focus on education. The humanistic theory approach engages social skills, feelings, intellect, artistic skills, practical skills, and more as part of their education. Self-esteem, goals, and full autonomy are key learning elements in the humanistic learning theory.

The humanistic learning theory was developed by Abraham Maslow, Carl Rogers, and James F. T. Bugental in the early 1900’s. Humanism was a response to the common educational theories at the time, which were behaviorism and psychoanalysis. Abraham Maslow is considered the father of the movement, with Carl Rogers and James F.T. Bugental adding to the psychology later down the line.

Maslow and the humanists believed that behaviorism and other psychology theories had a negative perception of learners—for example operant conditioning in behaviorism psychology suggested that students only acted in a good or bad manner because of the reward or punishment and could be trained based on that desire for a reward. Maslow and humanistic psychology suggests that students are inherently good and will make good decisions when all their needs are met. Humanistic psychology focuses on the idea that learners bring out the best in themselves, and that humans are driven by their feelings more than rewards and punishments. Maslow believed this and wrote many articles to try and demonstrate it.

This belief that humans are driven by feelings causes educators who understand humanistic psychology to focus on the underlying human, emotional issues when they see bad behavior, not to just punish the bad behavior. The humanistic learning theory developed further and harnesses the idea that if students are upset, sad, or distressed, they’re less likely to be able to focus on learning. This encourages teachers to create a classroom environment that helps students feel comfortable and safe so they can focus on their learning. Emotions are at the center of humanism psychology.

The principles of humanistic learning theory.

There are several important principles involved in the humanistic learning theory that all lead to self-actualization. Self-actualization is when all your needs are met, you’ve become the best you’ve can, and you are fulfilled. While Maslow and the humanists don’t believe that most people reach self-actualization, their belief is that we are always in search of it, and the closer we are, the more we can learn.

Student choice. Choice is central to the humanistic learning theory and humanistic psychology. Humanistic learning is student-centered, so students are encouraged to take control over their education. They make choices that can range from daily activities to future goals. Students are encouraged to focus on a specific subject area of interest for a reasonable amount of time that they choose. Teachers who utilize humanistic learning believe that it’s crucial for students to find motivation and engagement in their learning, and that is more likely to happen when students are choosing to learn about something that they really want to know.

Fostering engagement to inspire students to become self-motivated to learn. The effectiveness of this psychology approach is based on learners feeling engaged and self-motivated so they want to learn. So humanistic learning relies on educators working to engage students, encouraging them to find things they are passionate about so they are excited about learning.

The importance of self-evaluation. For most humanistic teachers, grades don’t really matter. Self-evaluation is the most meaningful way to evaluate how learning is going. Grading students encourages students to work for the grade, instead of doing things based on their own satisfaction and excitement of learning. Routine testing and rote memorization don’t lead to meaningful learning in this theory, and thus aren’t encouraged by humanistic teachers. Humanistic educators help students perform self-evaluations so they can see how students feel about their progress.

Feelings and knowledge are both important to the learning process and should not be separated according to humanistic psychology. Humanistic teachers believe that knowledge and feelings go hand-in-hand in the learning process. Cognitive and affective learning are both important to humanistic learning. Lessons and activities should focus on the whole student and their intellect and feelings, not one or the other.

A safe learning environment. Because humanistic learning focuses on the entire student, humanistic educators understand that they need to create a safe environment so students can have as many as their needs met as possible. They need to feel safe physically, mentally, and emotionally in order to be able to focus on learning. So humanistic educators are passionate about the idea of helping students meet as many of their needs as possible.

The role of teacher and student in humanistic learning theory.

In the humanistic learning theory, teachers and students have specific roles for success. The overall role of a teacher is to be a facilitator and role model, not necessarily to be the one doing the teacher. The role of the teacher includes:

Teach learning skills. Good teachers in humanistic learning theory focus on helping students develop learning skills. Students are responsible for learning choices, so helping them understand the best ways to learn is key to their success.

Provide motivation for classroom tasks. Humanistic learning focuses on engagement, so teachers need to provide motivation and exciting activities to help students feel engaged about learning.

Provide choices to students in task/subject selection. Choice is central to humanistic learning, so teachers have a role in helping work with students to make choices about what to learn. They may offer options, help students evaluate what they’re excited about, and more.

Create opportunities for group work with peers. As a facilitator in the classroom, teachers create group opportunities to help students explore, observe, and self evaluate. They can do this better as they interact with other students who are learning at the same time that they are.

Humanistic approach examples in education.

Some examples of humanistic education in action include:

Teachers can help students set learning goals at the beginning of the year, and then help design pathways for students to reach their goals. Students are in charge of their learning, and teachers can help steer them in the right direction.

Teachers can create exciting and engaging learning opportunities. For example, teachers trying to help students understand government can allow students to create their own government in the classroom. Students will be excited about learning, as well as be in-charge of how everything runs.

Teachers can create a safe learning environment for students by having snacks, encouraging students to use the bathroom and get water, and creating good relationships with students so they will trust speaking to their teacher if there is an issue.

Teachers can utilize journaling to help students focus on self-evaluation and their feelings as part of learning. Using prompt questions can help students better understand their feelings and progress in learning.

Best practices from humanistic theory to bring to your classroom.

A teaching degree is a crucial step for those who want to be teachers. A degree can help them learn about current practices and trends in teaching, learning theories, and how to apply them to the classroom. Established teachers can also greatly benefit from continuing education and continuously expanding their techniques.

When considering their own teaching practices, teachers can work to incorporate humanistic theory into their classroom by:

Making time to collaborate with other educators

Co-planning lessons with other teachers

Evaluating student needs and wants regularly

Connecting with parents to help meet specific student needs

Preparing to try new things with students regularly

Ready to Start Your Journey?

HEALTH & NURSING

Recommended Articles

Take a look at other articles from WGU. Our articles feature information on a wide variety of subjects, written with the help of subject matter experts and researchers who are well-versed in their industries. This allows us to provide articles with interesting, relevant, and accurate information.

{{item.date}}

{{item.preTitleTag}}

{{item.title}}

The university, for students.

- Student Portal

- Alumni Services

Most Visited Links

- Business Programs

- Student Experience

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

- Student Communities

What is the Humanistic Theory in Education?

Quick Definition of the Humanistic Theory in Education

Definition: The humanistic theory of teaching and learning is an educational theory that believes in teaching the ‘whole’ child. A humanist approach will have a strong focus on students’ emotional wellbeing and eternally view children as innately good ‘at the core’.

Assumptions of Humanism

A humanist educator’s teaching strategy will have four philosophical pillars. These pillars will guide the teacher’s beliefs and, ultimately, how they teach. These four pillars are:

- Free Will : We have free choice to do and think what we want;

- Emotions impact Learning: We need to be in a positive emotional state to achieve our best;

- Intrinsic Motivation: We generally have an internal desire to become our best selves;

- Innate Goodness: Humans are good at the core.

A Note on Referencing

As my regular readers know, all good essays should start with scholarly definitions . So, here are some scholarly definitions of humanism that you might want to use in your essay:

- Duchesne & McMaugh (2016, p. 263) argue that humanist theorists “consider the broad needs of children, including not just cognitive but also social and emotional needs.”

- Crain (2015, p. 363) points out that the focus of humanist psychology is helping people (humans!) to achieve their personal best. He argues that humanists “have proposed that people, to a much greater extent than has been realized, are free and creative beings, capable of growth and self-actualization.”

- Veugelers (2011, p. 1) argues that humanist education “focuses on developing rationality, autonomy, empowerment, creativity, affections and a concern for humanity.”

- Khatib, Sarem and Hamidi (2013, p. 45) argue that humanist education “emphasizes the importance of the inner world of the learner and places the individual’s thought, emotions and feelings at the forefront of all human development.”

Remember, it’s best to paraphrase definitions (e.g. put them in your own words ). Then, you should reference your sources at the end of your sentence or paragraph.

Here’s my attempt at paraphrasing the above scholarly definitions:

Humanism believes that a learner is free-willed, fundamentally good, and capable of achieving their best when the ideal learning environment is produced. The ideal learning environment should caters to the social, emotional and cognitive needs of the learner (Crain, 2009; Duchesne et al., 2013; Veugelers, 2011).

Now that you’ve got your definition and scholarly sources , don’t forget to include your references at the end of your essay:

Crain, W. (2015). Theories of Development: Concepts and Applications: Concepts and Applications. London: Routledge.

Duchesne, S. & McMaugh, A. (2016). Educational Psychology for Learning and Teaching . Melbourne: Cengage Learning.

Veugelers, W. (2011). Introduction: Linking autonomy and humanity. In: Veugelers, W. (Ed.). Education and Humanism: Linking Autonomy and Humanity (pp. 1 – 7). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Khatib, M., Sarem, S. N., & Hamidi, H. (2013). Humanistic Education: Concerns, Implications and Applications. Journal of Language Teaching & Research , 4 (1), pp. 45 – 51.

The above references for the above sources. They’re in APA format, so if you are required to use another format like MLA, Chicago or Harvard, you’ll need to convert these to the correct style .

2. Origins of Humanist Education

In the early 20 th Century (early 1900s), behaviorism and psychoanalysis were the dominant educational theories. Humanists thought both these theories had very negative perceptions of learners. These theories tried to diagnose and ‘fix’ learners.

In reaction, humanistic education emerged. Humanists argued that people should stop seeing learners as ‘defunct’ or ‘in deficit’. Instead, humanists focussed on how we could help learners bring out the best in themselves.

Another thing humanism rejected was the assumption that learners were easily controlled by rewards and punishments. Humanists thought this ‘behaviorist’ approach of rewards and punishments failed to see that humans are complex thinkers. We’re driven by many different factors, and one major one is of course our emotions : how we’re feeling.

You can’t just punish someone when they do something wrong. No, no, no!

To humanists, you need to explore the factors underpinning their bad behavior. Maybe they’re cold, hungry or feeling unsafe! If we fix the underlying problem, the person will probably start behaving more appropriately.

So, humanists emerged largely as a reaction to the negativity and simplicity of behaviorist beliefs about childhood. If you want to learn more about behaviorism, check my post on behaviorism out here .

3. A Focus on Emotions

Our emotions are important to humanists. Emotions (or what we often refer to in educational psychology as ‘affect’) will shape how, what, when, and how well we will learn something.

If you’re grumpy, sad, frustrated or distressed, you’re probably not going to learn too well. When I’m worried about something, I spend all my time thinking about it – and I forget to concentrate!

So, humanists think we should pay attention to emotions and make sure our learners are feeling positive, relaxed and comfortable. These are emotions that will make us ready to learn.

In fact, humanists think other theorists like behaviorists, cognitivists and sociocultural theorists don’t pay enough attention to emotions. While other theories pay attention to things like social and cognitive (mental processes) learning, they seem to overlook that our emotions have a really important impact on how well we learn.

Humanists want to solve that problem. Below, you’ll read all about different ways in which they do this.

- Related Post: How emotions influence our learning.

4. Humans are Fundamentally Good

According to the humanistic theory of personality , we are all fundamentally good people, humanists argue. We’re not born evil or start out with evil intentions. And we all seem to want the best for ourselves and our tribe.

So why do people end up being bad, even evil?

Well, according to humanist theorists, people do bad things because they have not been nurtured the right ways.

When our fundamental needs as humans are not fulfilled, we might act out. When a young person is treated inhumanely in childhood, they may go on to act inhumanely as a response. When someone is hungry, they may get grumpy and act out. But, if we treat young people well and ensure their needs are cared for, they’ll be able to focus on being good, well-rounded and fulfilled human beings.

So, something really nice about humanism is that humanist teachers tend to see the good in their students. Even when a student is playing up, the teacher doesn’t hand out punishments to try to ‘fix’ the student. Instead, the teacher says “what needs aren’t being fulfilled here?”

- Related Post: How do you see children? Good? Evil? Innocent?

5. Abraham Maslow: Key Humanist Theorist

You need to know about Abraham Maslow. If you write an essay on humanist education and don’t mention him, expect to lose marks.

So here are some basics about Maslow to get you off on the right foot:

- Born in 1908 in New York City.

- Was an unhappy, unfulfilled child (did this impact his beliefs, do you think?)

- Was once a Behaviorist theorist who studied under the famous Edward Thorndike, but decided behaviorism didn’t say enough about the complex nature of human beings.

- Was a professor at Brooklyn College.

- Developed the famous Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

- Died in 1970

I got the above information from this scholarly book:

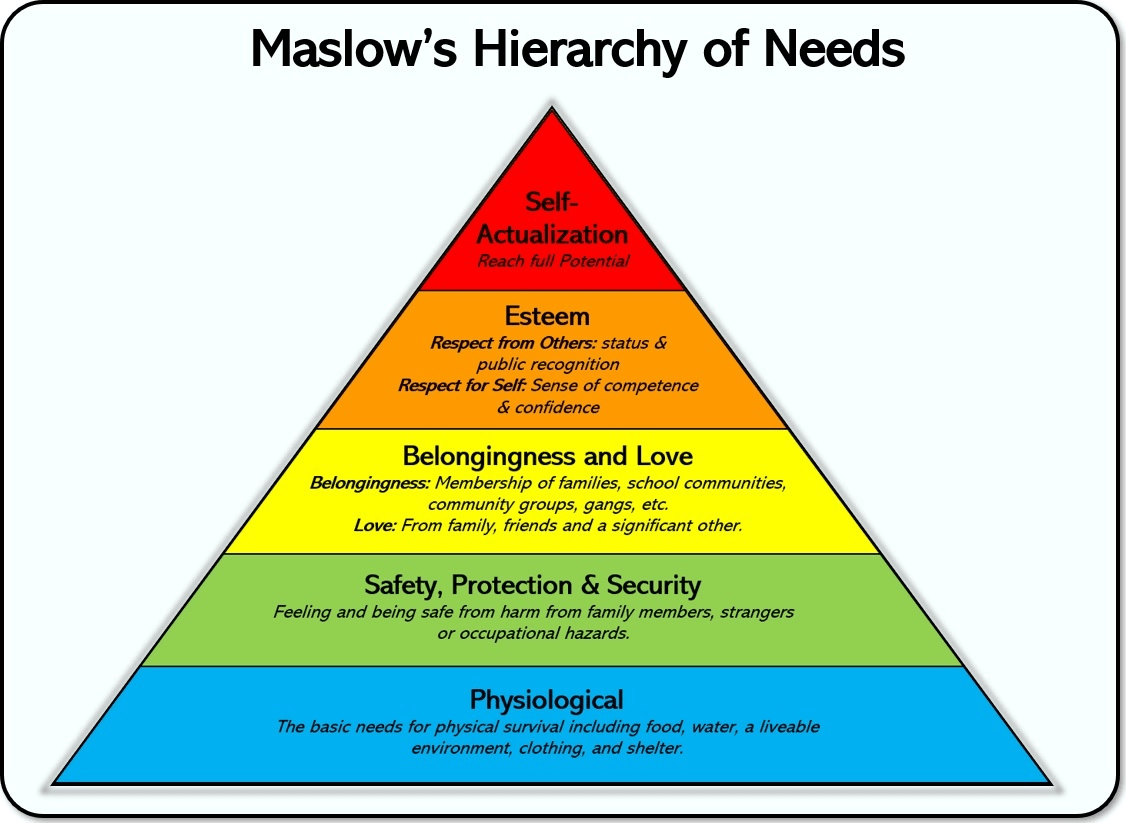

6. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs is a famous pyramid that shows the fundamental things that people need in order to be fulfilled in their lives.

Background to the Hierarchy: Maslow created the Hierarchy of Needs after examining the lives of a group of highly successful people including Mahatma Gandhi, Albert Einstein, Abraham Lincoln and Elanor Roosevelt. According to Maslow, each of these successful people had each of these needs fulfilled, which let them climb to the top of the pyramid and reach ‘self-actualisation’ (a sense of fulfilment). Maslow thought only about 1% of all people reached self-actualisation.

The hierarchy has two types of needs:

- Basic Needs: At the bottom of the pyramid are basic needs or what we sometimes call deficit needs or deprivation needs. When we don’t have these needs, we’re motivated to fulfil them by any means necessary.

- Growth Needs: Once we have our basic needs satisfied, we work on growth needs or what we sometimes call being needs or esteem needs. These are the needs that have to be met to reach self-actualization.

Maslow thinks all of us strive to meet the needs on his pyramid every day of our life, but only few of us make it all the way to the top. Supposedly, we can’t meet higher-up needs until we’ve successfully met the lower needs on the pyramid.

Here’s the hierarchy:

- Physiological Needs (a basic need): Not to be confused with ‘psychological’, physiological needs are the things that we physically need to survive. These include: water, clothing, shelter, and food.

- Safety, Protection and Security Needs (a basic need): We all need to be safe from harm in order to thrive in life. If we’re always looking over our shoulder to see if we’re going to get whacked, we’re less likely to concentrate on learning anything new!

- Belongingness and Love (a basic need): Once we have successfully met our physical and safety needs, we can start working on developing relationships. All humans need positive relationships to be fulfilled. This might include having a sense that you’re included and belong in a classroom, that you’ve got a loving family to go home to, and that you have a group of friends to lean on in times of trouble.

- Esteem (a growth need): ‘ Esteem’ means to be thought well of. You need to think well of yourself ( self-esteem ) but also have others think well of you. If you have low opinions of yourself, you’ll set low standards for yourself and never be able to climb higher up the pyramid.

- Self-actualization (a growth need): The need for self-actualization is the feeling that you want to become the best you can be, now that all your needs have been met. You can go on to pursue creative endeavours and succeed to the best of your abilities because you’re not busy fighting to have all your other needs fulfilled.

7. Examples of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs in the Classroom

Most teachers expect you to use examples in your essays . So, let’s take a look at some examples of each of Maslow’s needs in education:

a) Examples of Maslow’s Physiological Needs in the Classroom

- Food – If a child comes to class hungry, they may not be in a fit state to study. To address this, teachers can implement Crunch n Sip time, start a Breakfast Club , or develop a partnership with a local food bank .

- Water – Teachers can encourage students to drink water before entering the classroom or encourage students to have a clear water bottle sitting on their desk .

- Clothing – I once had a student who started coming to class wearing a hoodie in the middle of the summer. Why? Because her mother had recently left the family and the father wasn’t coping. He hadn’t done the washing in weeks and my poor student didn’t have any shirts to wear. The solution? Our school parents’ committee had a clothing collection that the student could ruffle through to find a shirt she liked, while I contacted the appropriate liaison officer to get the dad some support.

b) Examples of Maslow’s Safety Needs in the Classroom

- Safe from Guns – As an Australian-Canadian, I was shocked when an American Grade 1 teacher relayed how worried she was about gunmen entering her school. I knew it was a worry in an abstract sense for teachers in the US. But I’d never put myself in the shoes of a worried teacher who felt that it might happened to her students any day. I feel for the poor students who have to have this thought go through their minds while trying to study.

- Safe from Strangers – Most schools these days required all visitors to school grounds to head to the front office to get a nametag and sign-in. This is to ensure students feel safe and don’t have strangers walking in and out of their classrooms for no reason.

- Safe from Harm – Classrooms need to keep sharp or dangerous materials a safe distance from students. Cords that could trip students up and tables with splinters need to be replaced so students can concentrate on learning rather than being exposed to harm.

c) Examples of Maslow’s Belongingness Needs in the Classroom

- Memberships – Inclusion of students in table groups in class , afterschool clubs and class research groups can help give them a sense of ownership over the classroom.

- Democratic Class Rules – Students who create their own classroom rules may feel a greater sense of belonging and ownership in the classroom.

- Display Walls – Having exemplary artworks or photos of students on the walls of the classroom can make students feel as if the classroom is a place where they are included and belong.

- Diversity in class books – Students who are of minority backgrounds may feel as if their identities are underrepresented in the classroom. Diverse protagonists in books and diverse representation in imagery around the classroom can help students feel as if their identity is included and respected.

d) Examples of Maslow’s Esteem Needs in the Classroom

- Celebration of Successes – When a student succeeds, feel free to publicly promote that success. When students see their peers spoken about positively, your example may rub-off. Be the leader in having high regard (‘esteem’) for your own students.

- Promotion of Self-Belief – Encourage students to believe in their own abilities to succeed. Teach students about growth mindsets which emphasize that success comes from effort. When students internalize this attitude, they will begin to see themselves as powerful and capable learners.

- High Expectations – Set high expectations for students and praise them only when something is praiseworthy. If you overdo praise, students will not respond well – so give praise genuinely!

8. Strengths and Limitations of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Here are the pros of Maslow’s Hierarchy:

- A focus on emotions – There are not many educational theories that take into account students’ emotional (‘affective’) states. Maslow’s hierarchy helps to address this flaw.

- Clear and understandable – I can see several flaws in Maslow’s hierarchy (see next point) but it’s a good starting point for stimulating discussion about the importance of emotions in learning.

- A positive outlook – the hierarchy sees students as all having positive potential and able to climb to the top.

Here are the cons of Maslow’s Hierarchy:

- Linear – It is evident that people can succeed and learn in very troubling, difficult situations. Students can succeed through poverty, war and hardship to rise to become doctors and artists. Maslow’s hierarchy doesn’t take into account the fact that some people can learn despite some of their basic needs not being fully met.

- Methodologically Limited – Maslow developed the hierarchy by looking at a small subset of successful people. The hierarchy is not statistically relevant and lacks a clear evidence base.

(Note: later in this article there is also a list of general strengths and limitations of humanist theory overall, which you can jump to by clicking here.)

9. Carl Rogers: The other Humanist Theorist

Carl Rogers was another highly influential humanist theorist. If you’re writing an essay about humanism in education, I strongly recommend you also write about Rogers’ ideas.

Here’s an overview of Rogers’ key concepts:

- Actualizing Tendency: According to Rogers, we all have a tendency to strive toward personal growth. We all have ambitions to be better. Rogers called this an ‘actualizing tendency’, and used this concept to underpin his ideas about education.

- Freedom to learn: Rogers write the book Freedom to Learn which outlines how it is important for students to be freed from the constraints of a school curriculum in order that they can be free to explore things they are interested in. If we are freed to learn what we choose to learn (emphasis on free choice here!), we will learn things that our actualizing tendency (desire for self-improvement) lead us towards. This may mean we end up learning more, and learning things that are more important to us personally

- Unconditional positive regard : We have already seen from Maslow that humanists believe students need to have strong self-esteem (positive regard for themselves). Rogers believes that we can help students achieve stronger self-esteem by unconditionally seeing students in a positive light. Much like a parent who loves their child unconditionally, teachers have to see that their students are fundamentally good, even when they’re at their worst.

- Facilitation: Because humanists don’t believe there should be a set curriculum or learning outcomes, teachers become facilitators rather than authority figures . Teachers encourage students to seek new knowledge and provide the materials and support needed. This approach is very similar to the approach used in constructivist and sociocultural education.

- Intrinsic motivation: Rogers believes schools have historically repressed intrinsic motivation that we all had before we went to school. Here’s a great quote from Rogers:

“I become very irritated with the notion that students must be “motivated.” The young human being is intrinsically motivated to a high degree. Many elements of his environment constitute challenges for him. He is curious, eager to discover, eager to know, eager to solve problems. A sad part of most education is that by the time the child has spent a number of years in school this intrinsic motivation is pretty well dampened.” (Rogers, as cited in Schunk, 2012, p. 355).

Related Post: Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic Motivation in the Classroom .

10. Examples of Carl Rogers’ Humanistic Theory in the Classroom

If we are to follow Rogers’ humanistic teaching approach, we would do some of the following things:

- Not use a Curriculum: Throw out the learning outcomes and help students learn things that are motivating and inspiring in their own lives.

- Encourage Choice: Ask the students not only how they want to learn but what they want to learn.

- Encourage Inquiry Learning: When students have chosen a topic to learn about, give them rich resources and an inquiry-based learning environment so students can explore their interests without having them stifled by nasty worksheet printouts!

- Act as a Facilitator: Don’t stand out the front of the class and teach in a teacher-centered manner that you might find from behaviourist theory. Instead, facilitate learning by creating the right learning environment for students to explore.

- Express Unconditional Positive Regard: Even when students are playing up, we need to have positive regard for our students by being empathetic, positive and supportive as educators . Our language should show students we have high regard for them: “This is not like you, I know you as a lovely person usually!”, “Let’s start tomorrow fresh and believe in ourselves that tomorrow will be a better day where you go back to being your well-behaved self.”

11. Strengths and Weaknesses of the Humanist Theory of Education

Strengths of humanism in education include:

- Unlike many theories that attempt to diagnose weaknesses, humanism sees the best in everyone and works hard to promote it;

- It is an empowering philosophy that sees young people as powerful and capable;

- It considers emotional states and how they impact learning, unlike many other theories;

- It is holistic, meaning it sees the ‘whole child’. It will look at cognitive, social and emotional aspects meaning it has many pedagogical overlaps with cognitive and social constructivist theories, but also adds the ‘emotional’ elements;

Weaknesses of humanism in education include:

- It does not follow a set curriculum. This aspect of humanism may be incompatible with contemporary schools which usually have a standardized curriculum that students need to learn from;

- If it were implemented in schools, every student would leave school having different knowledge. Sometimes students need to learn things like mathematics even if they don’t have intrinsic desire to learn about it!

- Some students require structure and routine to learn effectively. With its emphasis on choice-based learning, aspects of humanism may not work well for such students.

Related Motivation Theories:

- Expectancy-Value Theory

- Self-Determination Theory

- Keller’s ARCS Model of Motivation

- The ABC Model of Attitude

Cite these Sources in your Essay

Don’t forget that you need to cite scholarly sources in your essays!

Here’s the APA style citations for some sources I used when writing this article:

Bates, B. (2019). Learning Theories Simplified: …and how to apply them to teaching. London: Sage.

Schunk, D. H. (2012). Learning Theories: An Educational Perspective. Boston: Pearson Education.

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 5 Top Tips for Succeeding at University

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 50 Durable Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 100 Consumer Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 30 Globalization Pros and Cons

1 thought on “What is the Humanistic Theory in Education?”

Dr. Drew’s platform simplifies concepts and assists research students remember basic research and writing skills. Thanks Doc

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Humanistic Learning Theory – Teaching Students to Reach Their Full Potential

The Humanistic Learning Theory is a whole-person approach to learning where the focus is to help students become their best selves.

- By Paul Holt

- Oct 2, 2023

E-student.org is supported by our community of learners. When you visit links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission.

- The humanistic approach to learning is based on the idea that human beings are inherently good and intrinsically motivated.

- According to the Humanistic Learning Theory, students should be responsible for setting their goals and evaluating their progress.

Our main goal as educators is to help our students thrive to increase the possibility of each student reaching their full potential. We want our kids to become functional adults, confident in their abilities, and contributing to the community. The humanistic approach to learning shares the same ideals and goals. Unlike some of the learning theories popular today, this approach focuses on educating the student’s “whole being,” not just the intellect.

So, what does it mean to educate the “whole being”? In this article, we’ll discuss Humanism and how it applies to education. In addition, we’ll look at the benefits and drawbacks of the Humanistic Learning Theory and how this approach can be applied in the online classroom.

Table of Contents

What is humanism.

Humanism is a philosophy that can be traced back to Ancient Greece. It is based on the idea that people are inherently good. The only reason why people do bad things is because their needs aren’t met. Humanism also places importance on human dignity and values – everyone has worth. Moreover, it believes that humans have the ability to control their environment, shaping it according to their needs. It further believes that a person’s potential for growth and development is unlimited.

What is the Humanistic Learning Theory?

So, what does humanism have to do with learning? Well, humanism’s view on education can be broken down into several foundations:

- Free will: Everyone has the freedom to do what they want.

- Innate goodness: Everyone is innately good “at the core,” and we will always want the best for ourselves and for others.

- Positive emotions: Feelings cannot be separated from intellect. A person needs to feel positive and relaxed in order to be open to learning and achieve the best results.

- Intrinsic motivation: Humans are born with the motivation to become the best version of themselves.

Based on these philosophical pillars, we can define what Humanistic Learning Theory is all about. First, it is an approach to education that is centered on the learner . The learner has freedom and autonomy. This means that much of what a person learns and how he learns is based on his choice, not on the teacher’s preferences.

Second, student-centered education includes student-led evaluation , which means that students are responsible for evaluating their progress. When evaluation is based on a grading system, students are encouraged to work hard to earn a high grade instead of being passionate about what they’re learning. According to this theory, rote memorization and routine testing do not promote learning. Self-evaluation , on the other hand, enables students to feel satisfaction and excitement about what they’ve accomplished. Students will focus on improving themselves based on the standards that they have set.

In addition, we all have an intrinsic desire to become our best selves. According to the Humanistic Learning theory, this means that students need to be engaged in the learning process . The desire to learn should come from the students. This means that teachers need to cultivate their curiosity and encourage them to pursue their interests. Once motivated, students will become active participants in the learning process and develop a love for learning.

Moreover, since we are all fundamentally good, teachers who use this approach should not view students who misbehave as “bad.” They also do not dole out punishments or negative feedback in order to fix or correct a behavior. Instead, they need to determine which needs aren’t being fulfilled, causing this type of behavior and preventing the student from reaching his full potential.

Educating the person as a whole

Learning, as defined by this theory, is the growth of a person as a whole. This means that the learning process needs to consider more than just the knowledge a student needs to acquire. The learner’s needs and desires, as well as his emotional state, are equally as important because these can impact learning.

In addition, to unlock a learner’s full potential, teachers need to consider and educate the “whole” person. Teachers should focus on both cognitive and affective learning, putting equal importance on feelings, artistic skills, social skills, self-esteem, and practical skills. Learning is not just about intellect.

Let’s make it easier to understand: When a student is feeling anxious or upset, it’s highly likely that he won’t be able to pay attention in class. Not only could this become a hindrance to the learning process, but it can also cause them to behave badly. Teachers will need to teach students how to deal with anxiety and how to overcome negative emotions in order for them to perform well. In addition, they need to create a learning environment where students feel safe and comfortable.

Here’s an example: Hunger, a basic human need, can affect a student’s attention, making it difficult for him to understand and/or engage in learning activities. This means that schools need to make sure that students are getting their basic needs met while they’re within the halls of the institution (for example, by providing meals in the cafeteria).

Advantages of the humanistic approach to learning

Applying the Humanistic Learning Theory in the classroom has several advantages:

- It promotes positivity in the classroom.

- This approach empowers students to motivate themselves to become the best version of themselves.

- Unlike many other learning theories, the Humanistic Learning Theory is a holistic approach that considers the emotional state of the students and how this can affect their learning.

- The humanistic approach to learning is inclusive of everyone. Learning is focused on the individual, not the group, giving every child the opportunity to succeed.

Disadvantages of the Humanistic Approach to Learning

Like other learning theories, there are also disadvantages to using this approach in the classroom:

- Because the source of authority is the student, the curriculum needs to be less fixed, which may not be compatible with traditional schools.

- This approach requires students to pursue their interests. However, not everyone will have an intrinsic desire to study subjects like mathematics and physics, potentially setting them up for future challenges.

- Routine and structure are necessary for some students to learn effectively. Freedom of choice and authority in learning may not be suitable for these students.

Applying the Humanistic Learning Theory in the online classroom

Because learning is student-centered, the role of the teacher is to be a facilitator and model. The teacher is responsible for helping students develop learning skills, feel motivated and engaged, and provide them with different topics, materials, and tasks to choose from. As a facilitator, teachers also need to create opportunities for students to work with their peers to practice social as well as practical skills.

Some examples of implementing the key principles of humanism in the online classroom include:

- Teachers can help students create goals at the start of the school year. Make sure that you take time to discuss what they want to achieve and how they can achieve them.

- Provide different learning opportunities that cater to the interests and learning styles of the students. For example, students can choose to complete practical activities, watch videos, conduct research on the web, and/or participate in online discussions (e.g., social media interaction, online forums).

- Use gamification to increase engagement and motivation. Instead of prizes, students go up levels and earn experience points, which can help promote a student’s intrinsic desire to improve. In addition, levels and experience points make it easier for students to evaluate their progress. Moreover, this can help them develop a love for learning.

- Give students flexibility in their schedules and modes of participation. Some students learn better in the morning, while others are more efficient later in the day. Some may want to join an online class, while others prefer to do their online lessons on their own. Teachers can look for adaptive software that allows independent self-paced study. Doing this also encourages independent responsibility.

- Create a safe, comfortable learning environment by allowing students to take snack and bathroom breaks when they need them. In addition, encourage them to evaluate and share their feelings because these can impact learning. Cultivate a classroom culture where everyone is accepted and emotional experiences can be shared through honest discussions. If needed, you can create a safe or brave space where they can tell you how they feel privately, such as a breakout room in Zoom .

- Integrate problem-based learning and inquiry-based learning techniques to help students practice critical thinking and feel a sense of accomplishment. Don’t forget to celebrate their milestones to give them recognition and increase their motivation.

- Practice empathy and respect. Prepare for moments when students are experiencing high levels of stress or anxiety. Be ready to listen and become a support system. This may be harder when classes are conducted online; the distance can feel like a barrier. Developing a good relationship with the students and keeping in touch with them online outside of school hours can help them trust you with their feelings.

The Humanistic Learning Theory tells us that learning goes beyond the intellect. The focus is on the student and helping him reach his full potential. The greatest contribution of this theory in the classroom is that it promotes independence, a love for learning, and a motivation for self-growth. As teachers, it is our privilege to help them become the best version of themselves, confident people who make meaningful contributions to our society.

The Flowtime Study Method: A Complete Guide

Do you like the idea of the Pomodoro method but not how it keeps interrupting you just as you are starting to get into your flow. Read our guide to the Flowtime Method to see if this might address your issues.

10 Biggest Disadvantages of E-Learning

These disadvantages of E-Learning must be addressed to ensure the legitimacy and longevity of the online learning industry.

FutureLearn Review: How Do Their Courses Hold Up?

In this FutureLearn review, you will learn about the MOOC platform’s selection of online degrees and certification courses.

Publications

On-demand strategy, speaking & workshops, latest articles, write for us, library/publications.

- Competency-Based Education

- Early Learning

- Equity & Access

- Personalized Learning

- Place-Based Education

- Post-Secondary

- Project-Based Learning

- SEL & Mindset

- STEM & Maker

- The Future of Tech and Work

Julian Guerrero on Pathways and Programs for Indigenous Youth

Cynthia leck and juetzinia kazmer-murillo on igniting agency in early learners, timothy jones and mason pashia on what education can learn from poetry, sydney schaef on the future9 competencies, recent releases.

Unfulfilled Promise: The Forty-Year Shift from Print to Digital and Why It Failed to Transform Learning

The Portrait Model: Building Coherence in School and System Redesign

Green Pathways: New Jobs Mean New Skills and New Pathways

Support & Guidance For All New Pathways Journeys

Unbundled: Designing Personalized Pathways for Every Learner

Credentialed Learning for All

AI in Education

For more, see Library | Publications | Books | Toolkits

Microschools

New learning models, tools, and strategies have made it easier to open small, nimble schooling models.

Green Schools

The climate crisis is the most complex challenge mankind has ever faced . We’re covering what edleaders and educators can do about it.

Difference Making

Focusing on how making a difference has emerged as one of the most powerful learning experiences.

New Pathways

This campaign will serve as a road map to the new architecture for American schools. Pathways to citizenship, employment, economic mobility, and a purpose-driven life.

Web3 has the potential to rebuild the internet towards more equitable access and ownership of information, meaning dramatic improvements for learners.

Schools Worth Visiting

We share stories that highlight best practices, lessons learned and next-gen teaching practice.

View more series…

About Getting Smart

Getting smart collective, impact update, 4 holistic classroom ideas inspired by maslow’s humanist approach.

By: Chris Drew

Too often educators look at students as being ‘in deficit.’ Deficit thinking can be evident in schools that focus too heavily on reforming student behavior rather than creating positive learning climates that bring out the best in students.

This mentality was also dominant amongst educational psychologists in the mid-20th century. However, during this period, humanist theorist Abraham Maslow began to promote a novel idea. Maslow’s humanist perspective emphasized the importance of promoting the innate goodness inside all people.

From Maslow’s perspective, goodness needs to be nurtured by providing learners with a safe and fulfilling learning environment.

Perhaps Maslow’s most influential idea was his hierarchy of needs. To Maslow, we all have a range of needs that should be met in order to bring out the best in ourselves. Those needs are:

- Physiological needs : At the base of Maslow’s pyramid are the physical requirements for life, including food, water and clothing.

- Safety needs : Students need to feel safe and secure in order to focus on learning.

- Belongingness needs : A feeling of inclusion and membership in a classroom community can help students enjoy coming to school.

- Esteem needs : Students need to feel their teachers and peers have positive regard for them. Similarly, students should feel good about themselves and their own ability to succeed.

- Self-Actualization : Also known as self-fulfillment, this need is met when students are achieving to the best of their abilities in the classroom.

Maslow’s hierarchy remains incredibly relevant to educators today. Below, I outline four ways Maslow’s hierarchy can inspire holistic education.

1. Start a Breakfast Club

Researchers from the University of Leeds in England reported in 2012 that 14% of students skip breakfast on a regular basis. Similarly, studies from the United States report 8-12% of children turn up to school hungry.

Furthermore, students who skip breakfast are disproportionately from disadvantaged backgrounds and single-parent households.

Those students who skip breakfast can suffer socially, emotionally and academically throughout the school day. By contrast, researchers from Northumbria University highlight that students who participated in a breakfast club initiative in England self-reported increased capacity to focus in class and moderate their moods.

Thus, school-run breakfast clubs have the potential to support children’s learning by satisfying physiological needs which sit at the foundation of Maslow’s hierarchy.

By providing students with breakfast at the start of the school day, schools can proactively prevent potential issues that arise from low energy levels, fatigue and the inability to complete set tasks.

2. Create Brave Spaces

Maslow emphasizes that people need to feel safe in order to achieve self-actualization. Feeling safe in the classroom is more than simply about a sense of comfort. Rather, it is about feeling safe to step outside of your comfort zone with the knowledge that risks are accepted and encouraged.

Young people who feel insecure or fear harsh punishment from their teachers will be less inclined to be bold or take risks. Therefore, teachers should explicitly promote brave spaces: spaces in which young people know that risk taking, creativity and boldness are rewarded.

Colorado teacher Leticia Guzman Ingram writes that teachers should help students feel safe to make mistakes. She recommends strategies such as ‘Failure Fridays’ where the teacher and students discuss failures people have made and how the failures made them better learners.

3. Give Classroom Ownership to Students

To satisfy what Maslow calls ‘Belongingness needs’, teachers need to help students feel as if they are co-owners of the classroom space.

One way to promote a sense of ownership is to reinforce to the students that the classroom is not ‘mine’ but ‘ours.’ Every student should see a part of themselves in the classroom and be able to tell outsiders about how they were integral to creating a positive classroom culture .

My measure of success for creating belongingness is when I see students leading their parents by hand around the classroom, pointing out displays and telling stories of their creation. I want to see students pointing to one element of each display and showing how their small contribution helped in the creation of the whole.

4. Use Inquiry-Based Learning

Carl Rogers, a humanist contemporary of Maslow, also believed that self-fulfillment would only occur when a student is freed to explore topics that intrinsically motivate them. For this to be achieved, educators should allow students the freedom to choose topics of personal interest and identify ways to explore those topics in depth.

Open-ended, interest-based learning is increasingly difficult in an era of standardized curriculum requirements .

However, I like to give my students as much freedom as possible within the confines of the curriculum by, for example, finding ways curriculum topics overlap with their hobbies.

Educating the Whole Child with a Humanist Approach

I find many educators gravitate toward humanism. It is a theory that affirms that all students are capable of becoming their best so long as educators pay attention to the whole child. We need to attend to our students’ needs, feelings and emotions to ensure their basic needs are met.

When we turn our attention to our students’ needs, we not only embrace a caring approach to education but also create the conditions for supporting each student’s cognitive and social development.

For more, see:

- Educating the Whole Child Through PBL

- Why Every 10-year-old Should Know Maslow’s Hierarchy

- Students’ Basic Needs Must Be Met Before They Can Learn Deeply

Stay in-the-know with innovations in learning by signing up for the weekly Smart Update .

Chris Drew teaches about educational theory and practice at Swinburne Online University. He writes on educational topics on his personal blog, The Helpful Professor .

Guest Author

Discover the latest in learning innovations.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Related Reading

Transforming Student Engagement Through Dialogue: 3 Approaches for Every Classroom

6 Creative Classroom Project Ideas

How Design Thinking Transforms Communities, One Project at a Time

5 Ways to Build Collaborative Learning Skills In and Out of the Classroom

Leave a comment.

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.

Nominate a School, Program or Community

Stay on the cutting edge of learning innovation.

Subscribe to our weekly Smart Update!

Smart Update

What is pbe (spanish), designing microschools download, download quick start guide to implementing place-based education, download quick start guide to place-based professional learning, download what is place-based education and why does it matter, download 20 invention opportunities in learning & development.

Humanism Learning Theory and Implementation in the Classroom

Back to: Learning and Teaching – Unit 2

- The five basic principles of humanistic education can be summarized as follows:

- Students’ learning should be self-directed.

- Schools should produce students who want and know how to learn.

- The only form of meaningful evaluation is self-evaluation.

- Feelings, as well as knowledge, are important in the learning process.

- Students learn best in a nonthreatening environment.

Definition of Humanism Theory

Abraham Maslow, along with Carl Rogers, Malcolm Knowles, and many others propounded the humanism learning theory which focuses on the development of learners. He is considered as the father of Humanistic Psychology. The theory believes in encouraging learners to develop an interest for learning. Maslow believes that experience play a key role in influencing the learning and behaviour of humans. This theory is highly centered on learners. In this theory, teachers serve as role models. They motivate the learners who are required to be observant and keen to explore.

Scholar Definition: The Humanist Teaching and Learning Theory is an educational theory that believes in the teaching of the child “as a whole”. The humanistic approach will pay special attention to students’ emotional well and will always consider children “essentially” good children.

Humanist theory:

Humanism stresses the importance of human values and dignity. It proposes that people can resolve problems through science and reason. Rather than looking to religious traditions, humanism focuses on helping people live well, achieve personal growth, and make the world a better place.Examples of humanistic behavior are everywhere. Everything from being kind to a stranger to scuba diving could be humanistic behavior if the motivation is a desire to live a good, authentic, and meaningful life.

Today, people call Petrarch the “ father of humanism ” and even the “first modern scholar.” Petrarch’s humanism appears in his many poems, letters, essays, and biographies that looked back to ancient pagan Roman times

Basic Principles of Humanistic Education

Students should be able to choose what they want to learn. Humanistic teachers believe that students will be motivated to learn a subject if it’s something they need and want to know.

The goal of education should be to foster students’ desire to learn and teach them how to learn. Students should be self-motivated in their studies and desire to learn on their own.

Humanistic educators believe that grades are irrelevant and that only self evaluation is meaningful. Grading encourages students to work for a grade and not for personal satisfaction. In addition, humanistic educators are opposed to objective tests because they test a student’s ability to memorize and do not provide sufficient educational feedback to the teacher and student.

Humanistic educators believe that both feelings and knowledge are important to the leaming process. Unlike traditional educators, humanistic teachers do not separate the cognitive and affective domains.

Humanistic educators insist that schools need to provide students with a nonthreatening environment so that they will feel secure to learn. Once students feel secure, learning becomes easier and more meaningful.

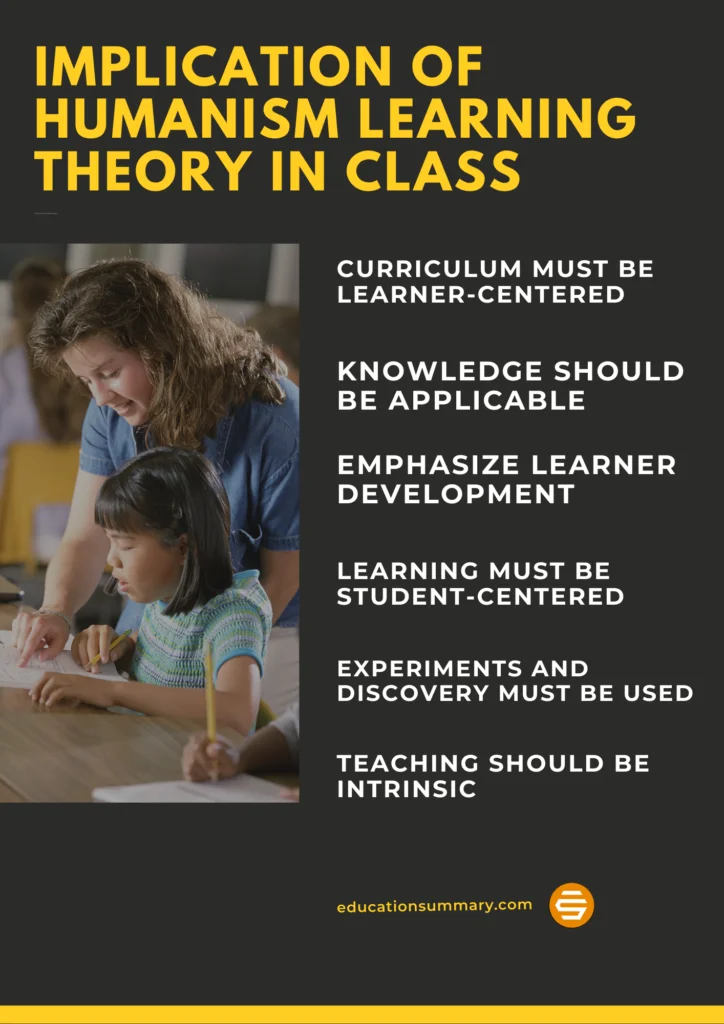

Implementation in the Classroom and Educational Implications

Humanism theory of learning plays an important role in enhancing the knowledge of the learners by fulfilling the ultimate goal of teaching.

Implications of instruction:

- Instruction should be intrinsic rather than extrinsic; instructional design should be student centered.

- Students should learn about their cultural heritage as part of self-discovery and self-esteem.

- Curriculum should promote experimentation and discovery; open-ended activities. .

- Curriculum should be designed to solicit students’ personal knowledge and experience. This shows they are valuable contributors to a nonthreatening and participatory educational environment.

- Learned knowledge should be applicable and appropriate to the student’s immediate needs, goals, and values.

- Students should be part of the evaluation process in determining learning’s worth to their self-actualization.

- Instructional design should facilitate learning by discovery.

- Objectives should be designed so students have to assign value to learned ideals, mores, and concepts.

- Take into account individual learning styles, needs and interests by designing many optional learning/discovery experiences.

- Students should have the freedom to select appropriate learning from many available options in the curriculum.

- Allow students input in instructional objectives.

- Instruction should facilitate personal growth.

- The implementation of humanistic theory in the classroom should take place in the following manner:

Curriculum Must Be Learner-centered

The curriculum should be based on the interest of the learners and should focus on their overall development. Their personal experiences and knowledge must be taken into account.

Knowledge Should Be Applicable

The knowledge being imparted to learners must be applicable in real life situations. They should be able to relate the lessons being taught with real life situations.

Emphasize Learner Development

Teachers must focus on all the round development of learners. Instructional methods should be such that it is comprehensible to learners and fosters their growth and development.

Learning Must Be Student-centered

The teaching learning method should be student-centered and they should also be included in the evaluation process for self actualization.

Experiments and Discovery Must Be Used

Since the humanistic approach to learning focuses on learning by discovery, experiments should be implemented in the curriculum to facilitate the same.

Learning Must Happen Through Discovery

The instructional method being used by the teacher in the classroom must facilitate learning through discovery.

Teaching Should be Intrinsic

Instead of adopting extrinsic teaching methods, teachers should adopt intrinsic teaching methods so that the teaching learning method can be student centered.

STUDENT’S ROLE

- The student must take responsibility in initiating learning; the student must value learning.

- Learners actively choose experiences for learning.

- Through critical self-reflection, discover the gap between one’s real and ideal self.

- Be truthful about one’s own values, attitudes and emotions, and accept their value and worth.

- Improve one’s interpersonal communication skill.

- Become empathetic for the values, concerns and needs of others.

- Value the opinions of other members of the group, even when they are oppositional.

- Discover how to fit one’s values and beliefs into a societal role.

- Be open to differing viewpoints.

TEACHERS ROLE

- Be a facilitator and a participating member of the group.

- Accept and value students as viable members of society.

- Accept their values and beliefs.

- Make learning student centered.

- Guide the student in discovering the gap between the real and the ideal self, facilitate the student in bridging this gap.

- Maximize individualized instruction.

- To facilitate independent learning, give students the opportunity to learn on their own ~ promote open-ended leaming and discovery.

- Promote creativity, insight and initiative.

The humanistic approach mainly focuses on the development of learners due to which factors must be remembered while implementing this approach in the classroom.

Why Schools Need to Change Purpose and Problem-Solving: Developing Leaders in the Classroom

Taiwo A. Togun (he, him, his) Faculty, Pierrepont School, and Co-Founder & Executive Director, InclusionBridge, Inc. in Connecticut

Today’s learners face an uncertain present and a rapidly changing future that demand far different skills and knowledge than were needed in the 20th century. We also know so much more about enabling deep, powerful learning than we ever did before. Our collective future depends on how well young people prepare for the challenges and opportunities of 21st-century life.

As educators transform learning in their classrooms, they can develop their students ’ talent and their own leadership while also making a difference for their community.

“Purpose is a stable and generalized intention to accomplish something that is at once meaningful to the self and consequential to the world beyond the self” –Bill Damon, Professor of Education, Stanford University

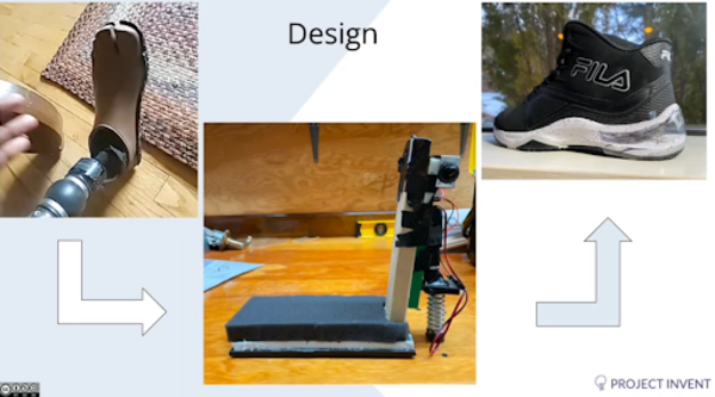

As an educator, my purpose is to nurture and develop young talents. While I have been teaching for over a decade, I only articulated my purpose as an educator last year during my master’s program in technology leadership while learning to integrate technology, strategy, and leadership. Coincidentally, I became a Project Invent fellow at the same time, which only served to embolden my sense of purpose. Clarity of purpose is a vital leadership quality that shapes my experience and something I believe ought to begin every teacher’s leadership journey. While one’s articulation of purpose may change over time, there’s something quite powerful and differently effective about writing down and reading out loud your purpose statement. In the following reflection, my goal is to share how I approach my development as an educator and a leader as one and the same and how my experience with Project Invent’s design thinking curriculum represents a continuing education in leadership.

Developing a Leadership Identity

As I work toward establishing my leadership identity and persona as an educator, I find myself reflecting on Sun Tzu’s Art Of War in which he described “ Leadership [as] a matter of intelligence, trustworthiness, humaneness, courage, and discipline. ” Additional discourses from the likes of Thomas Carlyle , Tolstoy , and Plato have all helped me arrive at an understanding of leadership as a function of nature, nurture, and situation . In addition to clarity of purpose, other leadership qualities must be deliberately nurtured through training and cultivated through practicing acts of leadership. I believe an effective leader empowers others and recognizes situations when the act of leadership is, in fact, letting others lead. This summarizes the core takeaway of my “teacher as a leader” philosophy.

In 2021, I applied to Project Invent’s educator fellowship , hoping to reinforce my leadership identity as an educator. Project Invent is a nonprofit organization that trains educators in six key teacher practices, each aimed at empowering students with the mindsets to become fearless, compassionate, and creative problem solvers. As a Project Invent Fellow, I have made significant progress in mastering these six teacher practices:

- Make failure okay

- Push to the next level

- Be a co-learner

- Let students take the wheel

- Leave room for exploration

- Challenge assumptions

Courtesy of Project Invent

Leadership in Practice

Each of these teacher practices can occur independently but are often interrelated. Deliberately committing to one can undoubtedly lead to others. For example, being comfortable with being a co-learner allows space for leaving room for exploration of alternatives. Openness to the possibility of new alternatives begets making failure okay and also encourages letting students take the wheel and drive the process, while the teacher-leader nudges them to push to the next level. Of course, the order of these is not fixed.

I teach computer science at Pierrepont School in Westport, Connecticut. My Project Invent student teams come from two classes of juniors and seniors, who originally signed up for an Applied Data Science course. We began our journey in the second semester in January, after which the students were informed that their course name had changed from “Applied Data Science” to “Essential Skills of the Emerging Economy” which has two parts: “Critical Reasoning & Storytelling with Data” and “Human-centered Problem-solving.” These are the only details my brave students had to work with. Needless to say, students had to be open-minded about how the journey would shape up. After all, it is not the first time that I would modify course requirements to marry interests and new opportunities that would benefit my students. I enjoy such flexibility and reasonable autonomy at my school; I also enjoy the flexibility and reasonable autonomy of learning as I teach. I am comfortable admitting to my students that I have absolutely no idea how to solve a challenge that I assign them, but assure them we can figure it out together… and we always do.

In January, the challenge was dauntingly ambiguous: We were going to invent a new technology intended to positively impact members of our community. Given their awareness of how little I knew about what we might need, or how to invent anything for that matter, students had to buy into taking a journey with an uncertain destination together. My job as a co-learner was to make sure to emphasize that it was all about the journey, the lessons, and the fun we have; and not necessarily the end. The humility and willingness to be a co-learner with students in the driver's seat have served me very well throughout my journey as a teacher, and I can not begin to describe the gratification of learning with and from students and seeing them rise to the challenge. This time, however, we had access to a community of resources, fellows, and mentors through the extended Project Invent team, who made it even more reassuring despite the many unknowns. From the onset of our journey, my students demonstrated creative confidence and trust in one another (most of the time) and our system as a class. Together as a team, we were ready and excited for the journey.

“Coming into this class with a limited computer science background, I was a little intimidated to embark on a project that had the potential to create such a big and meaningful improvement in our community. However, as I grew more comfortable with my team, my fears eased. I was able to develop from a quiet listener to a confident doer, not only for the duration of this project but also in my longer-term data science pursuits.” –Alexis Bienstock, Pierrepont School Junior

Project Invent as Context for Leadership Development

Human-centeredness brings a new dimension to problem-solving. It helps to establish and define a worthy purpose. My students and I began our journey on our Project Invent experience by getting to know our “client” Roderick Sewell , a Paralympic athlete and swimmer, as a person—what he enjoys doing, how he got to become a serious athlete, and what his goals and aspirations are. We focused on his abilities, accomplishments, and strengths. This set the stage for helping us—students and teachers alike—cultivate mindsets of empathy and curiosity. It is this empathic curiosity that would eventually lead to two Project Invent teams of ambitious students, who set out to address Roderick’s expressed challenges of lower back pain and efficient switch from running to walking legs:

“Because there’s nothing to absorb the load except for my lower back…If there was a little more cushioning on the soles to absorb the impact, then everything would be even more doable.” “ I can’t really run with my walking leg. One question that I always have is if something happened, how fast would I be able to get up and get away? ” –Roderick Sewell