18 Dec 2019

Migration in Nepal: A COUNTRY PROFILE 2019

This inaugural Migration Profile for Nepal presents the most recent census of Nepal on population and housing, which showed that almost 50 per cent of the country’s household had a member who was either working overseas or has returned. Remittances has been a major contributing factor for the socioeconomic development of the country. The Government of Nepal recognizes the central role that migration plays in its socioeconomic development, and that the issue of migration has been high on the policy agenda in Nepal. Nepal is actively seeking to be able to better leverage the link between migration and development, and committed to working towards achieving the targets in the Sustainable Development Goals and seeking to ensure an enabling policy and institutional environment to support this. This Migration Profile will be an important tool for evidence-based policymaking and programme planning for policymakers and practitioners, which provides a comprehensive picture and analysis of the migration situation in Nepal, compiling the available migration data across several entities of the Government.

Population Dynamics in Contemporary South Asia pp 273–301 Cite as

Pattern, Structure and Consequences of International Migration in Nepal

- Deo Kumari Gurung 4

- First Online: 17 March 2020

141 Accesses

Migration is an important component of population change, along with fertility and mortality. Migration is not a biological variable as it comprises socio-economic, cultural, political and human behavioural factors.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Lowland area in the foothills of the Himalayas in Southern Nepal, lies to the north of Indo-Gangetic plane, is characterized by fertile alluvial deposits and rich biodiversity.

Acharya LV (2001) Integration of population in poverty alleviation programmes in Nepal. In: Bal Kumar KC (ed) Population and Development in Nepal, vol 8. Central, Department of Population Studies, Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu

Google Scholar

Adhikari JN, Gurung G (2004) Migrant workers and human rights, Out Migration from south Asia, Nepal: prospects and problem of foreign labour migration. Ahn P (ed) Delhi, India, ILO p 101

Census (2001) Census of Nepal. Nepal Bureau of Statistics

Gurung H (1998) Nepal: Socio-Demography and Expression. New Era, Kathmandu

Jha HB (1995) India-Nepal border relation. Centre for Economic and Technical Studies, Kathmandu

Nair (1998) Migration in a Maelstrom. The World Today March 1998:66–68

Seddon D et.al (1998) Foreign labour Migration and the remittance economy of Nepal Himalaya. J Assoc Nepal Himal Stud 18(2)

UNDP (1998) Human Development Report. Oxford University, NewYork

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Geography, Tribhuban University of Kathmandu, Kathmandu, Nepal

Deo Kumari Gurung

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, Delhi, India

Anuradha Banerjee

Departmrnt of Geography, The University of Burdwan, Barddhaman, West Bengal, India

Narayan Chandra Jana

Indian Institute of Dalit Studies, New Delhi, Delhi, India

Vinod Kumar Mishra

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Gurung, D.K. (2020). Pattern, Structure and Consequences of International Migration in Nepal. In: Banerjee, A., Jana, N., Mishra, V. (eds) Population Dynamics in Contemporary South Asia. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-1668-9_12

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-1668-9_12

Published : 17 March 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-15-1667-2

Online ISBN : 978-981-15-1668-9

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

LUP Student Papers

Lund university libraries, impacts from migration and remittances in the nepali society - analysing the migration process in nepal.

- Axel Fredholm LU

- Social Sciences

Men’s Migration and Women’s Lives: Evidence from Nepal

By Pratistha Joshi Rajkarnikar

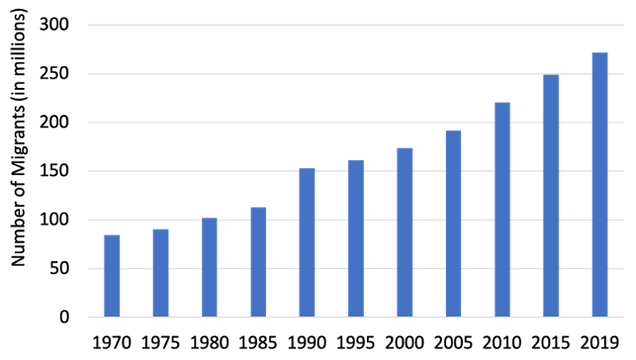

With over 272 million individuals living outside their countries of birth, migration has become one of the most salient features of our times. Much of the literature on migration focuses on the economic benefits of remittances sent home by these migrants. As of 2018, remittances amounted to USD 689 billion and was the largest source of foreign capital for developing countries.

Figure 1. Total number of migrants in the world, Select years

Source: World Migration Report, 2020

The impacts of migration go far beyond just economic gains. Migrants significantly transform the socio-cultural and political structures of both origin and receiving countries, through transfers of social, political, and human capital.

One key consequence of migration is the emergence of transnational households , where families are divided across borders, but continue to share common resources and make decisions jointly. This creates new social structures, which are especially striking in societies with strictly defined gender roles, where men migrate to provide for the family, while women stay behind to provide care.

This transformation in gender roles is one of the central features of labor migration from Nepal, where over half of the country’s households have at least one migrant member and remittances account for more than a more than a quarter of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

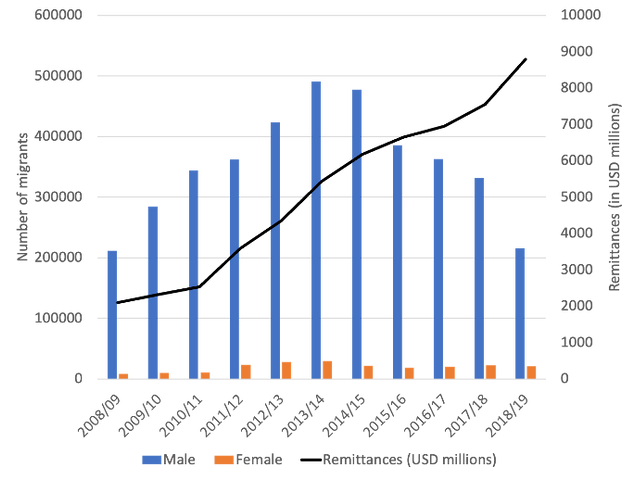

Indeed, in the decade ending in 2018, over 4 million Nepalese workers received government permits to pursue foreign employment and more than 90 percent of these migrants were men.

Figure 2. Total number of migrants by gender and total remittances received (in millions of US dollars), Nepal

Source: Migration in Nepal, A Country Profile, 2019 .

This male-dominated migration has considerably transformed intra-household power relations and resulted in large changes in women’s roles and responsibilities in the domestic and socioeconomic spheres. Women are increasingly taking up the role of household heads, financial managers, and single parents, in a society that has historically suppressed their freedom. Despite these newfound opportunities, the continued existence of gender-segregated labor markets, and inequities in health, education, and restrictions on physical mobility, present significant challenges for women to cope in their new roles.

In-depth research on the gendered impacts of male migration from Nepal reveals a complex picture where women gain opportunities for increased freedom and greater access to economic and social resources during men’s absence, but these opportunities are often constrained by women’s position in the household, their education and employment background, and gendered social norms. The study used a mixed method research, based on quantitative analysis using data from Nepal Living Standard Survey-III (2010/11) and the Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2011 and qualitative analysis based on fieldwork interviewing 178 women in four districts of Nepal.

Main Findings: Women’s Work Responsibilities, Market Participation and Household Work

One of the direct consequences of migration of men is a change in the gender division of labor. Women’s participation in market work is likely to increase if they gain more freedom in the absence of men, or if barriers to entering the labor market for women start disappearing due to shortage of labor. In the case of Nepal, it is, however, seen that women in migrant households have higher domestic and subsistence farming responsibilities and lower participation in market work.

This lower participation in market work for migrant wives is partly explained by the intensification of their domestic work, along with the reduced economic pressures by virtue of receiving remittances. Because of this increase in unpaid work, migrant wives are more likely to remain financially dependent on their husbands. Though they perform vital economic and social functions of household maintenance, their ability to contribute to the family’s economic security declines, thus reinforcing men’s role as the primary breadwinners and maintaining women’s subordinate position in the household.

Agency and Decision-Making

Migration of men is likely to increase women’s autonomy and decision-making power within the household. However, women’s ability to participate in household decision-making may be constrained by their financial dependence on men, as well as social norms on what is expected of them.

Analysis on changes in women’s decision-making power during men’s migration, in the case of Nepal, suggests that the outcome is mainly dependent on women’s position within the household. Women who take on the role of household heads are more likely to gain decision-making power, while those left under the supervision of other members (usually their in-laws) may suffer from reduced decision-making ability.

However, even when women gained decision-making power, the most important decisions – especially those related to financial matters – were made by men. In fact, women often worried about not being able to manage money by themselves and preferred consulting with their husbands, partly because of their economic dependence on men. In extended households, where women experienced either a decline, or no change in their decision-making role, the in-laws were the primary decision-makers.

Most migrant wives also faced higher social scrutiny and increased vulnerabilities during their husbands’ absence, limiting their participation in social spaces. Women who took on the role of household heads in their husband’s absence often had to step into public spaces out of necessity to maintain their livelihood (going to the market, health center or bank). While these women experienced an increase in their social participation, they often complained about increased stress from having to break social barriers and step into public spaces.

The only aspect of increased social participation that women seemed to appreciate was the stronger bond they formed with other women in the society, as they depended on each other for support.

For women in non-head positions, the need to step into public spaces was less severe as they lived in extended households, where other male members could take up work requiring public interaction. These women, in most cases, experienced greater restrictions on their physical mobility in the absence of their husbands.

Regional Differences

The different socio-economic conditions in the four research locations selected for the fieldwork also illustrated important differences in women’s experiences. Two districts (Chitwan and Siraha) were selected from the Terai region of the country, where gender norms are much more restrictive than the other two districts (Rolpa and Syangja) selected from the Hill region. Women’s participation in household decision-making and in public spaces was much higher in the Hill districts, than in the Terai.

Participation in market work was higher for women in the districts with higher poverty rates (Siraha and Rolpa). However, the type of employment for women in these two districts were very different. Women in Siraha were more likely to be involved in home-based production and low-skilled jobs, while women in Rolpa had higher educational qualifications and were often employed in the skilled-labor sector in government offices and as schoolteachers – a difference possibly attributable to the less restrictive gender norms in the Hills.

Policy Implications

The study’s findings help understand the consequences of migration from a gendered perspective and provide insights that may be valuable in developing a socio-political framework for fighting gender inequality and providing women with necessary resources and relevant skills to undertake new roles.

Most issues associated with difficulties faced by women during men’s absence are rooted in gender-based social and structural barriers in Nepal. Reducing these difficulties requires breaking oppressive relations by raising awareness through community programs, or media outlets and increasing access to education and employment opportunities for women.

Provision of public services for child and elderly care, state support towards accessing resources that facilitate performance of unpaid household work – such as access to fuel and water – along with policies to encourage access to labor market and ensure fair wages might help reduce some of the stress of domestic work and allow women to exercise greater autonomy in taking up paid work. Such policies might also help reduce their dependence on male migrant members, strengthen their agency, and contribute towards their empowerment.

As global migration rates continue to rise, it is increasingly important to consider such gendered consequences to ensure the well-being of families left behind.

Never miss an update: Sign up to receive ECI’s newsletter .

- No results found

Impacts from Migration and Remittances in the Nepali Society - Analysing the Migration Process in Nepal

Share "Impacts from Migration and Remittances in the Nepali Society - Analysing the Migration Process in Nepal"

Academic year: 2021

Loading.... (view fulltext now)

Lund University

Department of Sociology

Bachelor of Science in Development Studies

Impacts from migration and remittances in the, nepali society, analysing the migration process in nepal.

Author: Johan Nicander

Bachelor Thesis: UTVK03, 15 Hp

Spring term 2015.

Title: Impacts from Migration and Remittances in the Nepali Society –Analysing the Migration Process in Nepal

Bachelor Thesis: UTVK03, 15 Hp Supervisor: Axel Fredholm

Bachelor of Science in Development Studies 2015

Nepal is one of the countries where remittances in proportion of the GDP are the highest with 28,8 per cent in 2013. A total of 7,2 per cent of Nepal’s population are found abroad and the remittances that they transfer back have been recognized to play an important role in reducing poverty in Nepal, even though critics argue that these remittances are only spent and not invested. The two aims of this thesis are to analyse the impact from migration and remittances and to what extent these reduces poverty within the Nepali society. This thesis is critically analysing the impact of migration and remittances and argues that the global demand and need of cheap labour to the developed industrial societies will continue to attract and pull migrants out of their countries of origin and could act as an equilibrium to prevent this migration process to backlash. Nonetheless further research, and time, is necessary to measure the long-term consequences of migration and what the total impact of this never-ending demand could be for the Nepali society.

Keywords: Migration, Financial-Remittances, Social-Remittances, Poverty Reduction, Development, Nepal, Brain Drain (Gain)

List of Figures

Figure 1.1 Number of migrants that were abroad from Nepal in 2011 12 Figure 1.2 The impacts of migration and remittances in the Nepali Society,

1985-2010/2013 14

Figure 1.3 Brain Drain, total percentages of nearby countries tertiary educated

migrants leaving for the OECD-countries or the US 19

Figure 1.4 Total number of Nepali migrating outside India throughout

List of Abbreviations and Acronyms

FIFA - Fédération Internationale de Football Association FPE - Factor Prize Equalization

GDP - Gross Domestic Product

G24 - Intergovernmental Group of 24 HCH - High Caste Hindus

HDI - Human Development Index LCH - Low Caste Hindus

MLE - Ministry of Labour and Employment MDG - Millennium Development Goals

MTOA - Money Transfers Operators Association NLLS - Nepal Living Standard Surveys

PCA - Peace Comprehensive Accordance RBI - Reserve Bank of India

SLM - Segmented Labour Market

UN - United Nations

UNDP - United Nations Development Program

UNESCO - United Nations Educational, Science, Culture Organization USD - United States Dollar

Table of Contents

I. INTRODUCTION ... 1

I.IINTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND TO RESEARCH AREA ... 1

I.I.IMIGRATION IN RELATION TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF NEPAL ... 1

I.I.IICONTEMPORARY DEBATE OF REMITTANCES IN RELATION TO DEVELOPMENT ... 2

I.I.IIIDISPOSITION OF THESIS ... 3

I.IIAIM AND RESEARCH QUESTIONS ... 4

I.IIIDELIMITATIONS ... 5

I.IVTHE CONTEXT OF NEPAL AND THE HISTORY OF MIGRATION ... 6

I.VTHE GLOBAL DEMAND OF CHEAP LABOUR ... 8

I.VIMETHODOLOGY ... 8

I.VIIDEFINITIONS ... 9

II. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK ... 10

III. RESEARCH OVERVIEW ... 12

III.IMIGRATION AND DEVELOPMENT IN NEPAL ... 12

III.I.IDUTCH DISEASE (DD) ... 13

III.IIPOVERTY AND MIGRATION ... 14

III.IIIFINANCIAL-REMITTANCES ... 15

III.IVTHE PROCESS OF REMITTING MONEY ... 16

III.IV.IHUNDI ... 17

III.VSOCIAL-REMITTANCES,SOCIAL CAPITAL AND SOCIAL NETWORKS .. 18

III.VIBRAIN DRAIN OR BRAIN GAIN ... 19

IV. ANALYSIS ... 20

IV.IMIGRATION AND THE NEPAL GOVERNMENT ... 20

IV.I.IPERCEPTION OF BRAIN DRAIN (GAIN) IN NEPAL ... 22

IV.IIFINANCIAL-, AND SOCIAL-REMITTANCES AND ITS IMPACT WITHIN NEPAL ... 23

IV.II.IFINANCIAL-REMITTANCES ... 23

IV.II.IISOCIAL-REMITTANCES ... 24

V. CONCLUSION ... 29

I. Introduction

I.I Introduction and Background to Research Area

In the trajectories of the overall globalization process that is occurring across the globe, the exchange between information and people from one place to another has never been easier. In these trails of movement flow ideas, behaviours, knowledge and especially money. The transfer of money, remittances, has never been more accessible or cheaper. Also, the social remittances carries information and knowledge that has enhanced the flow of labour migration from the global south to the developed countries in their never-ending demand and need of cheap labour to the low-skilled labour sector within their countries.

In the last decades, the importance of remittances in relation to national development of Nepal has shed light upon the global development agenda. In 2014, the World Bank published their ‘Migration and Development Brief’ where they indicated that in 2013 the total amount of remittances transferred back to the global south, could increase by 3.5 per cent, to reach an estimated total of 436 billion USD (World Bank 2014). In numerous global south countries, the money from the remittances, now often outweigh the total amount of aid received from the developed world (Rosewarne 2012).

In 2004, Kapur published a paper for the G-24, questioning whether remittances could be the new development mantra of the global south. Kapur’s findings show that financial remittances have its greatest influence on tackling transient poverty, which is a major threat to the families left behind. Especially, for the women and girls who are most likely to become second priority, if the family is experiencing an income shock. The income shock could be described as when the expected income fails to be reached and puts the family in direct poverty and danger. Although, Kapur comes to the conclusion that it is very hard to distinguish the enduring effects of remittances on structural poverty, since the definition of economical development is not clear or easily understood (Kapur 2004, Ratha 2007).

I.I.I Migration in Relation to the Development of Nepal

In 2013, the total amount of remittances transferred back to Nepal nearly exceeded the double amount of total income from Nepal’s export sector of goods and services.

Remittances in Nepal stood for 28,8 per cent of Nepal’s total GDP in 2013 and the total amount of money remitted back to Nepal has increased by 40 times in proportion to Nepal’s total GDP between 1991-2008 (Wagle 2012). By 2013, it had increased 57 folds (WB 2015). During the same time, 1991-2013, the export of goods and services in proportion of the GDP, decreased by 0,8 per cent to a total of 10,6 per cent, while the proportion of agriculture in proportion of the GDP, decreased by 12,1 per cent to 35,1 per cent in 2013 (WB 2015).

In correlation, a study made by Adams in 2003 reported that for 119 developing countries, the annual rate of remittances grew faster than the annual rate of the countries GDP, 3,86 versus 1,61 per cent a year (Adams 2003).

I.I.II Contemporary Debate of Remittances in Relation to Development

This section will provide the reader with a short introduction of the contemporary debate of remittances in relation to development that has spurred during the last decades.

The debate has three different strands (I) Remittances spurs national development. This strand is supported by the WB and the UN, and has most likely emerged from a neoclassical approach of rational choice and cost-benefit approach, where the exchange between sending and receiving will benefit everyone in the long run (World Bank 2014). (II) Remittances spurs national development if implemented with good policies and governance. Scholars who support this tend to have a Keynesian approach towards the role of remittances, that it cannot alone spur national development progress. Instead, they emphasize, since remittances tend to be spend and consumed instead of invested, that it is crucial to implement good investment-policies on national levels to make certain that some of these remittances are being invested (Sapkota 2013). (III) Remittances do not spur national development. This strand is stressing that remittances and migration leads to brain drain and that the economy of the sending countries would have done better with the aspiring migrants staying put in their countries to maintain and develop their own industries. These scholars have a historical-structural approach where they perceive migration as something troubling and as a dislocating natural process of enhanced capitalist societies. In short, the developed countries are exploiting the undeveloped by unfair terms of trade, or as laid out by Andre Frank; the global north “Develop

underdevelopment” for the global south-countries ( Massey et al, 2008:34, Chami et al, 2003, Massey et al, 2008; De Haas 2010).

These theoretical strands look upon remittances through different perspectives and differ in views, whether remittances can spur national development. Nonetheless, these three strands all agree upon the importance that remittances have in eliminating and decreasing poverty for the involved in this migration process (Chami et al, 2003, Sapkota 2013, World Bank 2014). These three strands states the contemporary key issues of remittances in relation to development, when it comes to this research overview.

I.I.III Disposition of Thesis

The thesis is organized as follows. The following sections will cover the aim and purpose of thesis and present the main research question for this study, but also the delimitation of thesis and the context of Nepal itself. It will further cover the global demand of labour and the used methodology within this thesis. Then last, it will give the reader a short introduction of certain definitions that will be presented throughout the thesis.

The second section presents two theories that will create the theoretical framework that will be applied throughout the research; segmented labour market-, and social capital-theory.

The third section presents the literature overview and is organized as a series of subsections that represents different aspects of migration, remittances and poverty within the context of Nepal, all in relation to the research questions. The first part within the literature overview presents a brief and general conception of how migration and development are connected, both within Nepal and globally. The second part demonstrates the correlation between migration and decreasing poverty, providing information and numbers that will be used further into the thesis. The third part will highlight the remittances and will consist of two main pillar, financial-, and social-remittances, and their impact and functions within the Nepali society.

The fourth section presents the analysis where the theoretical framework will be applied to the research overview and the collected information, that has been collected and processed along this thesis process, will be presented. The first subsection within this analysis will utilize the concept of migration and how the

Nepali government are facing this in the 21st century, in order to further analyse how migration could spur Nepal’s economy and decreases poverty on both national-, and local-levels within Nepal. In correlation with the first subsection, the second subsection provides a more in depth-analysis of the impact of the financial-, and social-remittances in the Nepali society. The section provides with an overview of the two phenomena and will further analyse the outcomes, issues and the contemporary debates that previously are mentioned in the first subsection of the analysis. The theoretical framework will be used throughout the analysis to give further insight and understanding of the underlying causes of the attraction of migrant workers to the receiving countries and the role that social capital carries in this process of migration. The later subsection will focus mainly on the second research question of this thesis, in relation to the first research question and the previously mentioned subsections. This thesis is stressing that a large proportion of the total poverty reduction in Nepal, through financial remittances, could be the result of the segmented labour market and the never-ending demand and need of cheap labour from the developed capitalistic countries.

Finally, the fifth section will conclude the thesis, which will summarize the gathered information and the analysis, to attempt to put this thesis into a wider perspective within the context of migration and Nepal. It will also include some personal opinion and some comments regarding the future of migration and remittances in Nepal.

I.II Aim and Research Questions

This thesis has two aims; the first aim is to analyse and explain the process of migration and financial-, and social-remittances, and to examine the impact of these phenomena in the Nepali society. The second aim is to examine the impact that migration and remittances have in reducing poverty within Nepal. The two main research question of this thesis are ( I) What kind of impact does migration and remittances have in the case of Nepal (II) How could migration and remittances decrease poverty in Nepal? These research questions are the guidelines of this thesis and will hopefully be able to shed light upon the role of migration and remittances, since the study aims to focus on some major important factors of

migration, remittances and poverty reduction. But also, what the outcomes have been of these factors, or, to some extent, could possibly be.

Seen through a micro/macro-perspective; these remittances create social security for the families and the communities’ left behind on local level, since they now can, hopefully, rely upon greater financial support. Through a macro perspective, in 2013 the total amount of remittances transferred back to Nepal, exceeded the double amount of total income from Nepal’s export of goods and services. Indicators and reports are stressing that these remittances could be the triple amount of total income from the export of goods and services within a couple of years. Remittances are Nepal’s most crucial way of receiving foreign exchange, and play a crucial part in protecting the national currency and to repay both long-, and short- term loans (WB 2015).

Further, this thesis will focus on certain aspects of migration that is, accordingly to my interpretation and my theoretical framework, of great importance for a deeper understanding of migration and the outcomes in Nepal. The study aims to provide an overall overview of important aspects such as, brain drain (gain), poverty reduction, the system of remitting, the Dutch Disease, financial-, and social-remittances and to some extent scrutinise the question of whether migration and remittances in correlation could decrease poverty and develop Nepal.

I.III Delimitations

This research overview is using sources and findings from Nepal where most involved migrants tend to be males. The available research is more male-centred per se even though it might not be the intention of the researcher or the organization. Although, it is of high importance to stress that both females and males are included in the migration process in Nepal and that both, are remitting and migrating from the whole of Nepal to the rest of the world. Hence, the male-centred focus creates a biased view upon how migration and remittances are analysed and explained within the context of Nepal. Therefore, the numbers and the total impact of the Nepali female migrants cannot be precise, it can only be only estimated within this thesis. As a high proportion of the female migration tend to flow through unofficial channels and cannot be accounted for.

There have been estimations that up to 200 000 Nepali women migrate into India alone for prostitution, annually (Chattopadhyay & McKaig 2004). These numbers are not accounted within the official numbers of the total number of female migrants. Furthermore, there have been other estimations that approximately 200 000 Nepali women are working in the Gulf region as well, though only 60 000 work permits have been issued for work in the Gulf region through the formal channels (Ghimire et al, 2011). Each year, a large number of women also travel annually into India to visit a friend or relative, though their purpose of this is false. As Nepal is not handing out any working permit for female migrants heading to the Gulf States to work within the domestic sector, since the high risk of Nepali female getting caught in prostitution and slavery. India has therefore become a gateway, due to the open border between the two countries, for aspiring female Nepali women to migrate worldwide through the unofficial channels (Thieme & Wyss, 2005).

The ban and the open border with India create opportunities, but also challenges, for the Nepali government and for the CBS to keep the total number of migrants correct and trustworthy and have therefore established some delimitations for this thesis. Instead, the available and reliable sources of migration tend to focus on left-out women and empowerment issues in relation to male migration. Remarkably, indicators are reporting that female migrants tend to remit more in proportion of their earnings than male migrants.

I.IV The Context of Nepal and the History of Migration

Nepal’s history of migration is not something new, migration is a process that has been present in Nepal for over 200 years. In pre-colonial times, the British armed forces hired the Gurkhas, disciplined and well-known Nepali soldiers, to fight alongside the British armed forces in their wars. Additionally, Nepali has migrated to India for work for decades; this border crossing is often not even seen as migration, due to India and Nepal’s open border and their longstanding migration history between each other (Thieme & Wyss, 2005, Thieme 2006).

Geographically, Nepal is located right between China and India and is landlocked with no major ports in their near surroundings. The consequence of this is higher transportation costs of goods that are being produced in Nepal than in nearby

countries that have access to ports (Faye et al, 2004). Also, there have been noted a correlation between landlocked countries (excluding European landlocked countries) and achieving human development levels, this is visible in the HDI-scale1 and is

stressed by Faye et al (2004). There are 48 landlocked countries in the world, including four partially recognized states. 14 of these landlocked countries are located within Europe and only one country, Moldova, does not make it to the top 100 on the HDI-scale. Of the other 34 landlocked countries, 26 of these are to be found on the HDI-scale bottom 87 out of 187. Also, the index stress that 9 countries out of the bottom 20 are landlocked countries (Faye et al, 2004, Sapkota 2013, UNDP 2014). Nepal was ranked 157th in 2011 on the HDI-scale, in 2014 they had climbed to 145th out of 187 countries in total. (UNDP 2014:162)

The migration process is highly patriarchal, in 2011/12; just 6 per cent of the registered Nepali that went abroad for work was female (Arnøy 2014). Female-out migration was previously forbidden to the Gulf States, due to the high number of Nepali women that was forced to work as prostitutes or sold to brothels. This ban was eased in 2003, but Nepali women are still not being allowed a work-permit to work in in the unorganized sector, that includes domestic work, in the Gulf States (Thieme & Wyss, 2005).

I.IV.I The Caste System

The caste system of Nepal is a social stratification system that is divided between four different Varnas2 and consists of high caste Hindus, HCH, and low caste Hindus,

LCH. The Brahman (priests and academics) is at the top; Kshatriya (soldiers) and Vaisya (traders and venders) are at the middle, while the Sudra (labourer) is at the bottom. The Sudra is known for being untouchables, also known as Dalit, the lowest group. The group is often ostracized from the main society of Nepal therefore very vulnerable.

There have always been assumptions in Nepal and among scholars, that caste and ethnicity of a labour migrant will determine the economic outcomes. Wagle’s (2012) comparison between LCH and HCH support this. LCH are more likely to receive less remittance than HCH and are less likely to migrate in the first place

1 The index measure how well a country achieves decent standard of living, education and

(Wagle 2012). Nonetheless, even though the LCH receives less remittance, the migration process attracts a high proportion of the LCH within Nepal. A possible cause of this could be that abroad, their belongingness within a LCH does not determine their work occupation, since many LCH have designated work sectors, or whether they are allowed to use the common water supply or whether their hamlet will receive any electricity or not. This was especially recognized to be one of the causes of migration of migrants from the far west of Nepal to Delhi, India (Thieme 2006).

I.V The Global Demand of Cheap Labour

This study acknowledges the classical labour migration theories, such as neoclassical labour migration approach where each agent makes rational decisions to maximise their incomes, and the classical push/pull-theory as reasonable theories to analyse migration in Nepal, though old-fashioned. This thesis is using parts of it but will mainly focus, and stress, that the pulling factors are greater than the pushing factors. Instead, this thesis will analyse through a segmented labour market approach, that migration does not solely steam from rational decisions and the individual itself. In its place, this thesis aims through the theoretical framework to investigate the labour demand from the developed industrialized countries, which spurs this process and attracts the migrants to migrate in the first place (Massey et al, 2008:28).

By approaching the migration process using SLM-, and social capital-theory, I stress that the migrants and the aspiring migrants, with help from e.g. friends, relatives and members of the same caste, networks and through social remittances, enhances their social capital and adjust themselves to the future needs of the pulling countries. These two concepts will be further discussed and analysed in the theoretical framework further down.

I.VI Methodology

This research overview will be carried out as a comparative literature review, where the research will be using secondary sources as the empirical foundation. The study will conduct a meta-analysis that will provide a comprehensive and detailed overview of other scholars’ and organizations information from academic books, reports from

the UN and the WB, articles and other relevant sources (Timulak 2009). All current information have been combined and analysed through a social capital-, and a segmented labour market-theoretical framework, where the contextual meaning of the various types of different information have been of highest priority (Bryman 2008, Massey et al, 2008).

The use of secondary sources makes it feasible, since all information already has been collected, to provide an analysis that focus more in-depth and enhances a deeper clarification for this thesis. The research will examine multiple cases and findings from Nepal, but also abroad, to attempt to get a higher awareness and understanding of the role remittances has for Nepal and the Nepali in a development perspective. Although, these secondary sources are all objective since they all have been collected for different purposes and in different areas. Therefore they can pose some threats to the interpretation of the gathered information if they use different tools for measurements and further on. Thus, this study has been exposed of an intense source criticism of the material, to maintain a high credibility and is therefore alone, my interpretation of the collected material.

The gathered information of this study is mainly focusing on Nepal but is also focusing on nearby countries. Nepal was chosen for this study due to its extreme high proportion of remittances in relation to the total GDP of the country, 28,8 per cent in 2014 (WB 2015). Nepal was further chosen due to the high number of Nepal’s population working abroad, but also since migration has become a normal process in the everyday life of a Nepali and within the Nepali society.

Furthermore, the research overview does not have the intentions to be ground breaking. Instead, this thesis aims to contribute to a greater understanding of poverty alleviation and for future development interventions for maximizing the outcomes of migration and remittances, both from social-, and financial-remittances within Nepal and globally.

Throughout this thesis, a variety of keywords and concepts will be applied. As a recurring theme of development studies, the notion of how to out define development and other concepts is still as of today a very intense topic that does not assemble all

scholars on the same side.

To define the outcomes of financial-remittances, the HDI-scale that was created for the UN, by Amartya Sen and Mahbub ul Haq, will be applied. The scale measure life expectancy, education and per capita income and does present a more nuanced view upon development and not solely upon the economics.

The notion of social-remittances can be defined as the knowledge, ideas and the behaviours, the social capital, which the aspiring migrant, or the

families/communities left behind, receives and obtains prior to migrating or during the migration process. How high this level of social capital, that each labour migrant obtains and perceives, is diverse and cannot hence be said to be equal or the same for everyone involved.

The sub question of this research overview is how migration and remittances tackles poverty, and to which levels, within Nepal. To measure the percentage of Nepal’s population who lives in poverty, the measurement of living on less than 1.25 USD will be applied (WB 2015).

II. Theoretical Framework

This section will discuss and present the chosen theoretical framework and key theoretical concepts, which will be used throughout this research. Beyond the stereotypical push-and-pull theories of migration, a large proportion of scholars and researchers have started to look upon migration as “systems” that interacts on both macro-, and micro-level. The macro-level incorporates global political environment, regulations and laws for controlling the flows of immigration and migration, but also the global demand of cheap labour to modern capitalistic societies. As through a micro-level, scholars have increasingly started to look at the migrant themselves, in order to grasp the social capital that flows between sending-, and receiving-communities, and what kind of knowledge and understanding of the migration process the migrant possess prior to migration (Thieme & Wyss, 2005, Thieme 2006, Wagle 2012).

Two designated theories will create the theoretical framework of this research overview; (I) Segmented labour market theory and (II) Social capital theory (Massey

et al, 2008). The designated theories are thought to complement each other to offer an in-depth understanding of how migration and financial-, and social-remittances transferred back to Nepal actually contribute to, or counteract, for Nepal.

Segmented labour market theory, perceives migration as the result of the demand of labour to the modern industrial societies around the world. The destination countries are pulling the labour migrants to them, instead of the sending countries pushing them out. The choice of segmented labour market theory hopes to give the study a valid ground to better understand the economic aspects of migration and remittances. As a complement, the choice of social capital theory aims to, in relation with SLM theory, to better explain the social aspects of social-remittances in Nepal.

Some criticism that been put forward regarding SLM theory that it is mainly focusing on destination-, and not sending-countries. I argue that SLM approach is applicable to sending-countries and especially Nepal, since the global demand of cheap labour is attracting the labour migrants out of Nepal and towards the global developed labour markets. This phenomenon could be described as push-, and pull-factors, where the migration process is pushing the migrant out of Nepal and pulling the migrant into the destination-countries. Although, accordingly to my interpretation of the gathered information, I find the pulling factors stronger than the pushing factors. I am not stating that there are no pushing factors, because there are some, such as poverty, lack of opportunities and further on. I am solely stating the pulling factors weigh more than the pushing factors. Labour migrants migrate due to the fact that they can migrate and are needed somewhere else. Therefore, I find it valid to relate to SLM theory since it does not focus on the decisions made by individuals and not objecting to income maximization, merely it focuses on the pulling factors alone. To explain the economical aspects of remittances and migration as solely as an individual decision for income maximization, which neoclassical economic theory does, will not be investigated through this research. Further, neoclassical migration theory believes that the flow of labour from rich sending countries to labour-scarce destination countries will create factor prize equalization. This equalization will spur the wages of the fewer remaining workers in the sending countries and in time, this will equalize the wages between the sending and receiving countries between their labour forces (de Haas 2007, Massey et al, 2008). This factor prize

equalization has not occurred within Nepal, the wages have not been increased to those high levels and the shortcoming of labourer has not been noticed. A possible reason of this could be increased population within Nepal (CBS 2011),

As a complement to SLM theory, the social capital theory approach hopes to explain the social aspects of remittances and migration within Nepal. Social capital theory involves concepts such as ideas, behaviour, identities and social capital that are transferred between sending and receiving countries (Lewitt 1998). These key theoretical key concepts will be used in order to explain and examine the social networks that these national and international migrants are using, and the flow of social remittances that travel within those networks.

Hence, by combining these two designated theories and key theoretical concepts, I hope to create a theoretical framework that will help and explain my research overview and improve the understanding of migration and remittances and their roles within the Nepali society.

III. Research Overview

III.I Migration and Development in Nepal

In the Nepal census that was published in 2011 by the CBS, reported that 7,2 per cent of Nepal’s total population were abroad. In comparison, in 2001, only 3,3 per cent of Nepal’s population were abroad (see figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Number of migrants that were abroad from Nepal in 2011

Figure1.1 (CBS 2011) Indicators are stressing that the total sum of migrants are much higher due to India and Nepal’s open border and especially the total sum of female migrants is most likely larger, since the Nepali Government are not handing out any work permit to women heading to the Gulf States. Therefore, a large number of Nepali women travel

Number of migrants Male Female

to India, since they do not need any work permit to go there, from there they can further migrate to the Gulf States and the rest of the world. Also, the total number of Nepali women found in prostitution in brothels and large cities of India and the rest of the world are not included. There has been estimated that around 200,000 Nepali women and girls, one fifth only between the ages 10-14, are being migrated into India for prostitution, annually (Chattopadhyay & McKaig, 2004).

The total sum of remittances that was transferred back to Nepal from the Nepali migrants, did in 2013 nearly exceed the double amount of the total income from Nepal’s export of goods and services. Additionally, the remittances are equivalent to 28,8 per cent of the Nepal’s GDP and are Nepal’s most crucial way of receiving foreign exchange (World Bank 2015). The foreign exchange plays a crucial part in stabilizing the national currency and to repay both long-, and short- term loans.

III.I.I Dutch Disease (DD)

This small subsection is concluded within this thesis due to the debate of whether migration is actually gaining a sending-country, or not. In short, whether the country would earn more, by keeping the aspiring migrants to further gain the Nepal’s own industries and services, instead of brain draining the country of possible knowledge and manpower.

The DD occur when then national currency is rising due to an appreciation of the real exchange rate of the massive inflow of money from a national resource, in the case of Nepal, this is labour, cheap labour. This could harm the national labour-intensive products since it render the export products less competitive to the global market due to the increased currency (Kapur 2003). Nonetheless, this still lacks empirical evidence but indicators and reports are stressing that remittances have induced small levels of DD in other labour exporting countries (Grabel 2008, UNDP 2011).

Furthermore, the effects of remittances are recognized to be of small concern for the economy, since remittances tend to be distributed more widely and grow gradually over long periods. It therefore prevents natural-resource booms and high appreciation of the real exchange rates that could possibly be the outcome of a sudden massive inflow of money from natural resource earnings. A preliminary cross-country analysis has presented indicators and findings that remittances does not have the same

negative effects as other natural resource earnings, e.g. oil exports, since they do not come with the same high levels of corruption, that have been noticed as a problem to the global south countries effected by the DD (World Bank 2006).

In 2013, Sapkota presented an article where his conclusion was that Nepal has induced-remittance DD effects. Sapkota argues that the economy of Nepal cannot fulfil the needs and the demands of the remittance-receiving households due to their enhanced purchasing power capacity. The high demand for non-tradable and tradable goods have increased the prices within both sectors, due to the high numbers of labour migrants, inflation and increased costs of production. The outcome of this is less competitiveness on the global market of tradable goods and less export earnings, since the prices are decided internationally (Sapkota 2013).

III.II Poverty and Migration

Nepal has, and is still as of today, battling and struggling with high numbers of their population living in absolute poverty. In Nepal, approximately 80 per cent of Nepal’s total workforce population are found within the agriculture-sector, despite the fact that only 16.5 per cent of the 147,000 km2 of Nepal’s land is arable, providing each farmer with 0,089 ha fertilized land (Bhattarai 2011). The poverty headcount has decreased from 42,1 per cent in 1985 to 23,7 per cent in 2010. Between 1995-2004, remittances stood for one fifth – one half of the total poverty reduction in Nepal (Lokshin et al, 2010, World Bank 2006, Sapkota 2013). Though, this number only gives us an estimation of the total poverty reduction, since it only comprehends the remittances that went into the country through the official channels. Hence, it excludes the remittances that flow into Nepal through the informal channels, such as the Hundi-system3 . Including this would most likely increase the total decline that

remittances stood for.

In 2005, Adams published a paper asking whether migration and remittances actually could reduce poverty in developing countries. The findings were positive, both remittances and migration combined, but also separately, were decreasing the level and the depth of poverty for the accounted global south-countries (see figure 1.2). According to Adams, a 10 per cent increase of a country’s total migrant

3 Hundi-system is an unofficial financial system that is used for remittances and trade

population could lead to a total of 2,1 per cent decline of the poverty headcount in that specific country. Also, a 10 per cent increase of remittances per capita could further lead to 3,5 per cent drop of people living in poverty (Adams & Page 2005:165)

Figure 1.2 The impacts of migration and remittances in the Nepali Society, 1985-2010/2013 NEPA L Poverty.headc ount 1USD/1.25US D/p/d4 Poverty gap (per cent) Gini-coefficient Remittance s (Million USD) Per Capita Remittances (1995 constant USD) 1985 42,13 10,79 0,334 39 2,4 1995 37,68 9,49 0,387 101 4,95 2010- 23,7(2010) 5,4(2010) 0,328(2010) 5550(2013) 198,2 (2013 USD) Figure 1.2 (Adams 2005, WB 2015) III.III Financial-remittances

Information extracted from the MOF/Nepal and Nepal Rastra Bank estimated that the value of remittances increased 76 folds during 1991 and 2008. In relation to the proportion of GDP, its equal to a 40 times increase (Wagle 2012). As previously mentioned, the total number of official remittances remitted back to Nepal have increased to 5,5 billion USD and stands for 28,8 per cent of the GDP (World Bank 2015). Interestingly, the increase of official remittances in Nepal grew faster than then annul rate of Nepal’s GDP. This is equivalent to Adams (2003) findings, that shows that for 118 developing countries GDP, the annual rate of official remittances grew faster than the annul rate of the countries GDP (3,86 vs. 1,61 per cent a year) (Adams 2003:25).

4 1 993 prices. Often known as “1 USD a day,” the 1.25 USD a day poverty line measured in

2005 prices replaces the 1.08 USD a day poverty line measured in 1993 prices. Often described as “1 USD a day”(UN 2015)

Statistics have shown that in a number of global south-countries that are experiencing economical shocks or whether a natural disaster breaks out e.g. earthquakes or tsunami. Then remittances act as the most stable source of capital inflows, even more stable than private capital inflows during these troubled times. The money remitted back towards families and communities left behind establish a social security web for the involved but also, they create a security net for the Nepal government itself, since they do not have to focus as much on these involved. Also, these remittances generate a foreign exchange reserve that is used to repay Nepal’s debts and protect the Nepalese rupee to inflations and other financial downturns.

Criticism have been put forward towards that remittances is being spent instead of invested, that it is only enhancing consumption instead of enduring investments for the future. Although, Massey reports that in the case of Mexico, another country with high proportion of labour migrants and a total of 23 billion USD remitted back through the official channels in 2013, that every 1 USD migradollar spent, contributed to a total of 2.90 USD back to the GNP (Massey et al, 2008, World Bank 2015). Indicators are showing that this is the same in Nepal, but not to the same great extent as Mexico. Half of Nepal’s total tax revenue is extracted from the consumption tax, mostly from imported consumption goods that are generally consumed by the household that receives remittance. The total collected tax has increased from 8 per cent to 13 per cent of GDP between 2000/01 and 2010/11 (Sapkota 2013).

III.IV The Process of Remitting Money

In the process of the overall globalization that is occurring across the globe, more secure ways of transferring and receiving remittances are established and presented. Areas that previously were remote and hard reached are today easily connected to the outside world and the flow of money and information travels between these areas easier than ever.

Studies are showing that the cost of transferring money is an important factor for how much, how often and how the migrant will transfer money back. Migrants that are given the option to remit to a lower price are more likely to remit, and more often, than migrants that are not offered this (UNDP 2011). High transfer costs in proportion to the total sum, could possibly stop and hinder the migrants from

remitting. Scholars and organizations are now pushing the banks and receiving-, and developed-countries to create more cost-efficient and formal ways of transferring money for the migrants to prevent this obstacle (Ibid).

The typical sum of a remittance is generally 200 USD, in the process of transferring this sum; an estimated cost of 18 USD can be applied for the sender and there could also be a possibility of a fee when to extract the money for the receiver. This could harm the possibility of remitting and it could affect the migrants who wish to transfer lower sums of money (UNDP 2011). This might not harm the migrants as much that are located in countries where the wages are high, in comparison, as it harms the migrants that are in countries where the wages are low i.e. India. The conclusion is, lower the sums transferred, the higher the cost per dollar sent and more unlikely the process of remitting become.

III.IV.I Hundi

The Hundi system is involved within this study due to its massive, both present and historically, contribution to the migration process within Nepal and globally. Before formal banking system made cross-country transfers of money possible, the Hundi system was the only system available for the labour migrants if they needed to transfer money instead of transporting it back by themselves upon their return or using their social networks.

The Reserve Bank of India describes the system, as “a Hundi is an unconditional order in writing made by a person directing another to pay a certain sum of money to a person named in the order”. (RBI 2015) The Hundi system is an informal system of transferring money between people and places. The system has no legal ground in most countries and is recognized to be an unsafe and risky system where the chances of fraud and losses are high. Nonetheless, if a migrant lacks the proper financial tools to remit, the Hundi system can be the only possible way to remit. The Money Transfer Operators Association in Nepal, MTOA, has estimated that 35 per cent of the total sum of remittances that flows into Nepal, flows through the unofficial channel. Keeping the unofficial remittances in mind could mean that remittances possibly could contribute for one third of Nepal’s total GDP, in comparison to the official 28,8 per cent (Ghimire et al, 2011, Thieme & Wyss 2005, World Bank 2015).

The Hundi system is a massive web stretching all over global south and was previously featured in the global north, although this changed with the 9/11 attacks on the US when the system was closed in order to prevent further founding of upcoming terrorist attacks (Ratha 2005, Kapur 2003). The web is created by a series of middlemen that first; (I) Collect the money from the migrants (II) and then transfer the money to another middlemen in the Hundi centres, Dubai, Singapore and Hong-Kong. These middlemen will then import or transfer the designated amount into Nepal, where another middlemen will deliver it to the recipient in Nepal. The system charges nearly the same or lower as the banks, although the sender and the middlemen never sign any official or legal contracts, it is mutual trust that makes these remittances possible (Thieme & Wyss, 2005).

III.V Social-Remittances, Social Capital and Social Networks

"Where everybody knows your name" The motto of the legendary TV-series Cheers, captures the meaning of social capital and social network quite well. In correlation to social remittances, social networks are the networks that enhance the process of the migration journey. These social networks fetch social capital and can in other words be described as transporters of; ”Ideas, behaviours, identities and social capital flowing from host- to sending communities” (Levitt 1998:926) and “…social capital is the sum of the resources, actual or virtual, that accrue to an individual or a group by virtue of possessing a durable network of more or less institutionalized relationships of mutual acquaintance and recognition.” (Bourdieu & Wacquant 1992:119). The main characteristic of social capital is its possibility to adapt and change into other forms of capital, such as financial-, and human-capital (Massey et al, 2008:42).

The labour migrants from the far west of Nepal are frequently relying on their social capital that runs throughout their social networks for; migration, information exchange, loans and to remit money back to their families and communities (Thieme 2006). Through their social network they maintain a membership that could be transformed into other forms of capital that could be to their advantages. For instance, for the migrants who lack proper financial institutions, the social networks work as informal channels of remitting money between sending and receiving areas. These

social networks could reduce the costs of migration and the procedures that it involves. Although, the levels of social capital and how strong your social network is, is individual and cannot be to said to be true and equal for all involved. In this migration process between sending and receiving areas flows information, ideas, behaviours and social capital to and from migration communities (Levitt 1998). Rural and low-skilled labour migrants tend to migrate to India, while high-skilled labour tends to obtain jobs in countries with better salaries. It has been documented from two districts in the far west of Nepal, that 99,6 per cent of the labour migrants within these two districts are found in India and more precise, Delhi. Findings from these far west migrants show that even though their financial-, and human-capitals are low, they can still manage to migrate and obtain a job abroad with the help of their strong bonding social capital and their social networks. Their networks can, with help from the people within their own caste networks, provide the migrant with job, housing and access to saving-, and credit-associations, solely because of the migrant’s belongingness within the same caste (Thieme 2006). In other words, the far west migrants’ strong bonding social capital and their social networks complement their low levels of financial-, and human capital in their migration process and enhances their everyday life.

III.VI Brain Drain or Brain Gain

In 2003 the WB published a research paper by Adams on the subject of brain drain of 24 labour-exporting countries. Adams’s conclusion on the subject was that international migration tend not to extract a high proportion of the highest educated (tertiary-educated). Between 2,3 – 6,4 per cent of their best educated were extracted to the US and 1,3 – 16,5 per cent to the OECD-countries (Adams 2003). Although, Nepal was not in this research, but Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, India and Pakistan were (see figure 1.3). All these countries are located in South Asia and are similar to Nepal in many cases of labour migration and cultural aspects. For Nepal, the migration process attracts neither the most educated nor the least educated (Thieme & Wyss 2005).

Figure 1.3 Brain Drain, total percentages of nearby countries tertiary educated migrants leaving for the OECD-countries or the US

*Teritary (per cent) of total tertiary educated in each country Figure 1.3(Adams 2003) Furthermore, it has been concluded from a case study in Nepal, that migration and remittances enhance the level of education for the children and the total amount of higher educated students in Nepal (Ibid). In 2005, 2,054,165 children were enrolled as secondary pupils, while in 2014, 3,140,613 were enrolled accordingly to UNESCO (UNESCO 2015).

IV. Analysis

IV.I Migration and the Nepal Government

It has been suggested throughout the decades that the underlying causes of migration lies in the sending countries, where the push factors within the countries are pushing the migrants out and pulling them into the receiving countries. This approach is highly neoclassical with its rational choice approach, where they view every migrant and the process of migration as solely rational. This thesis stresses this approach as applicable to some extents, but will focus on the SLM theory and the social capital theory to understand the migration process and the outcomes of remittances for Nepal in another perspective then through the more classical theories.

The SLM theory stems that migration is solely the outcome of the fundamental need in every developed economy of cheap labour. The immense destination countries for the Nepali are opening their borders and allowing them to work, since the developed economics cannot increase the wages within their structural

South Asia-US

Teritary (per cent)

of tot.tet.educated* South Asia-OECD

Teritary (per cent) of tot.tet.educated*

Bangladesh 2,3 Bangladesh 1,5

India 2,8 India 1,3

Pakistan 6,4 Pakistan 3,3

inflation, i.e. their job hierarchy. The modern industrialized countries cannot increase the wages for the natives in the bottom, since this could threaten the relationship between status and remuneration that is socially accepted within this particular society (Massey et al, 2008). The developed industrial countries are inviting the labour migrants to come and work and this has spurred a never-ending cycle of attracting migrants to migrate and do the 3Ds; the dirty, dangerous and demeaning jobs that the natives in the receiving countries will not partake in.

Though, this is not something new for the Nepali, the attraction of cheap labour migrants between Nepal, India, and the rest of the world goes back 200 years, mostly through the Gurkhas. They were hired to fight for causes that were not their own, for salary (Thieme & Wyss, 2005:60). In Delhi, India, there is even a saying regarding the Nepali “ Nepali ra aloo jaha pani painchha = Nepali people and potatoes are found everywhere.” (Seddon 2002:27). The Nepalese Government has even been promoting overseas labour migration, the aim have been to increase the total amount of remittances and ease the high unemployment situation within Nepal, but also to improve the poverty situation within Nepal. This was documented in Nepal’s five-year plan for 1997- 2002 (Thieme & Wyss, 2005).

The process of migrating have become much more efficient since the democratic movement in the 1990 and the Maoist insurgency. Previously, Nepali could only obtain a passport in the main capital, Kathmandu. This meant that not all could afford the cost of traveling to the main capital to pick up their passport. As of today, it is possible to pick up their passport in the nearest district headquarter (Sapkota 2013). Nonetheless, the issue of obtaining a passport, in relation to time and cost, could be a reason for the large amount of labour migrants that are found in India. There is no need for a passport, if the aspiring Nepali migrant is heading to India, but also, the migrants who lack the proper financial, social and thenecessary skills, tend to migrate to India, where 80-90 of the total migrating population from the rural areas of Nepal is to be found (Seddon et al, 2002).

(Figure 1.4) show a steady increase of migrant workers leaving for work outside Nepal/India, with the exception of 2008/09 due to the global economic crashes that occurred that year. The efficiency of obtaining a passport, but also the increase of the demand of labour in the Gulf Region is possible reasons for this increase. Interestingly, the number of female migrants leaving for work outside -

Figure 1.4 Total number of Nepali migrating outside India throughout 1994-2011 and remittances in proportion of the total GDP

Figure 1.4 Information from MoF-2012 and DoFE-2013, diagram from (Sapkota 2013)

Nepal and India increased with 2,571 per cent, from 390 to 10,416 female migrant workers, in the period 2006-2011 (Sapkota 2013:1319). This increase does not have to be an increase; it can simply be that more female migrants decided to migrate through the official channels instead of the unofficial channels that historically have been the gateway for female-out migration from Nepal due to ban to certain areas and within certain sectors (Ghimire et al, 2011, Thieme & Wyss 2005).

Globally, the WB published their Migration and Development Brief stressing the importance of migration and the remittances. Their analyse stresses the need for migration and remittances should be involved in the post-2015 MDG agenda, due to its massive enrolment, since 1 out 7 in this world is recognized to be a national or international migrant (World Bank 2014).

IV.I.I Perception of Brain Drain (Gain) in Nepal

Despite the debate of migration is gaining or draining Nepal, the whole phenomena of brain gain or drain, comes down to the question of whether Nepal can successfully employ all Nepali found abroad. A large proportion of Nepal’s total population is unemployed and a huge proportion of them are found in the harsh agriculture-sector.

Where seasonal unemployment is frequent and the risks of natural disasters, such as floods, earthquakes and soil eruption could threaten their yields and their livelihood at any time (Bhattarai 2011).

Even though the existence of brain drain might be present in Nepal it could at the same time create higher education levels among stay-behind, since the wish of becoming migrants themselves. They could therefore adjust themselves to the future global demand of skilled labour and become more competitive on the global market. This thought of adjustment derives most likely from the social capital exchange that has established itself in Nepal after decades of migration. Aspiring migrants receives first-hand knowledge regarding the destination countries and tips of future upcoming jobs from the pioneer migrants, increasing their social capital prior to migration enhances their utilize maximization and lower the risks in relation to the migration process (Massey et al 2008:42-43). Notably, is that Nepal’s emigration process does not only attract skilled labour, but also low-skilled labour.

The prospect of receiving higher education prior to migration could develop into a brain gain where Nepal is flooded with educated workers, despite the presence of a brain drain, establishing an educated unemployment sector that have been shown in other labour-exporting countries, e.g. The Philippines, ready for departure and employment across the globe to fill the demand of cheap and skilled labour (de Haas 2007).

IV.II Financial-, and Social-Remittances and its Impact within Nepal

IV.II.I Financial-remittances

In recent years, the importance of remittances has shed light within Nepal, especially within the Nepalese government. The government has been supporting labour migration and has established easier ways to maintain a passport for its citizens (Thieme 2006). The financial remittances support improved consumption, land, housing and act as social insurance nets for the involved (Kapur 2003). Despite the criticism of remittances, mainly that most of it is consumed instead of invested, these remittances assist the involved household to climb the social ladder and escape extreme poverty within Nepal. Recent findings are stressing that remittances alone, between 1995-2004, stood for 20 up to 50 per cent of the overall decline of poverty in

Nepal, depending upon what you define as poverty reduction and whether the author included unofficial remittances or not (Lokshin et al, 2010, World Bank 2006, Sapkota 2013).

As earlier stated, the migration process of Nepali across the globe is not something new. The demand of low-skilled labour from Nepal to the receiving countries and India is increasing each year and the amount of remittances in relation to the GDP had by 2013 increased 57 folds, since 1991 (WB 2015, Wagle 2012). In correspondence with the theoretical framework of this thesis, the stress of the never-ending demand of cheap labour from Nepal to the receiving countries is further emphasized, since the improved wages within Nepal has not increased and the improved industries/services that would be the outcome according to the neoclassical economics of migration has not succeed in order to keeping the aspiring migrants to stay put. In its place instead, remittance have become equivalent to the double amount of Nepal’s export of commodities and services, in proportion of the total GDP and is reckon to become the triple amount anytime soon.

IV.II.II Social-Remittances

Areas that previously seemed remote and distant are today just a call away. In this globalization and within its trails, flows information and knowledge between the sending and the receiving areas, the aspiring migrant and the migrant. In the case of the migrants from the far west Nepal working in Delhi, they were frequently relying upon their social capital to maintain information, jobs and the transfer of money between sending-, and receiving-areas. These migrant groups tend to work within the same sectors and with fellow people from the same caste (Thieme 2006). A similar study from Bangalore supported this finding, that migrants mostly migrate and acquire jobs within the same sectors as the others within their social network (Ibid). Interestingly though, at the same time the migrant can acquire a job abroad by using their social capital, the migrant could struggle to acquire a post within Nepal, since social capital can be of various kinds and the belongingness of a certain caste could prevent this to happen, since the castes have designated jobs in Nepal. People form the rural areas of Nepal tend to have lower levels of social capital while urban Nepali, mostly Kathmandu’s’ and people from the western region of Nepal, tend to have a larger improved social-, and financial-capital. They can therefore acquire jobs easier

and much further away within Asia and the rest of the world with improved salaries (Thieme 2006, Seddon 2002). Although, this does not hinder the low-educated migrants to migrate as well, the social remittances that flows between sending and flowing areas makes it possible for low-educated to migrate as well due to the convertibility of social remittances. The aspiring migrants are using their castes, friends and people from the same communities to make this journey possible. In other words, the level of education does not hinder the aspiring migrants, the social remittances is instead enhancing the process and making it possible for many and is therefore an important factor in understanding migration in Nepal (Thieme & Wyss 2005).

The total population of Nepali found abroad exaggerated during the Maoist insurgency between 1996-2006 and stigmatized the migrants that left Nepal. Thus, the migrant that left Nepal were in some cases branded, especially the migrants that originated from the far-west or the mid-west areas of Nepal where the conflicts were most intense, since their possible political standpoint, was recognized as a threat for the country of destination (Menon & Rodgers, 2011). For instance, the Indian government were concerned of migrants who remitted money back to the CPN in their rebellion against the monarchy of Nepal (Thieme 2006). The rebellion ended in the Comprehensive Peace Accordance, PCA, in 2006 and how big the impact of the social remittances is not known. Instead, Deraniyagala (2005) stressed that the underlying causes of the rebellion where the interaction of political, social and historical factors to name a few. These factors throughout the economic injustices that have spurred from decades of poverty did most likely, according to Deranjyagala, spur the armed conflict. The Maoist movement was most frequent and strongest among groups living with low human development levels living in poverty in Nepal (Deranjygala 2005). Nonetheless, social remittances might not have spurred the insurgency but the social remittances created channels for males, mostly, to migrate by using their social networks obtain jobs in India to support their families and communities left behind that had to deal with the insurgency.

IV.III Poverty Reduction Overall in Nepal

migrants. India is still recognized to host most of the migrated, but remittances from e.g. Qatar and UAE have surpassed India in total amount of money being remitted back to Nepal (Ghimire et al, 2011). As previously mentioned, remittances are equivalent to 20 – 50 per cent of the total drop in poverty between 1996-2004 within Nepal, depending on which information and whether the author includes unofficial remittances as well (Lokshin et al, 2010, World Bank 2006, Sapkota 2013). Also, the total sum of households receiving remittances increased with 7 percentages from 11 to 18 per cent during the same period (Wagle 2012). Accordingly, based on information from the NLSS that was collected in 2003/04, if there were no financial remittances remitted back to Nepal, poverty within Nepal should have only declined to 36 per cent, instead of the 31 per cent as it did with the remittances (Ghimire et al, 2011).

The global demand of cheap labour and the improved and more efficient ways to maintain a passport and work permits abroad by the Nepal government is now attracting more Nepali than ever to seek employment abroad. The demand of cheap labour is not yet seen to decrease in the Gulf States, especially not in Qatar with the FIFA World Cup 2022 ahead and all the necessary infrastructure and stadiums that needs to be constructed in Qatar for them to be able to host the event. Travel agencies within Nepal are now daily making arrangements for the labour migrants leaving Nepal to work in Qatar. In 2011/12, 105,681 Nepali got their work permits issued for work in Qatar (Ghimire et al, 2011), which is approximately 290 migrants leaving each day. In other words, a jumbo jet is departing from each day from Nepal, packed with labour migrants to fill the need of the never-ending demand of cheap labour within Qatar where the foreign labour force make up for 95 per cent of Qatar’s total labour force population (Baldwin 2011). Interestingly, the state-owned airline of Qatar, Qatar Airways, now has three direct flights leaving Kathmandu each day to Doha.

During 2001-2011, the total number of labour migrants abroad increased with approximately 250 per cent, from 762,181 in 2001 to 1,917,903 in 2011 (CBS 2011, MLE 2014). In correlation to Adams previously mentioned study, a 10 per cent increase of a country’s total migrant population could lead to a 2,1 per cent decline of the total poverty headcount in that country (Adams 2005). Though, there is no designated number of what the poverty headcount was in Nepal by 2001, but the UN

statistics for the MDG indicators are reporting that in 2003 the poverty headcount was 53,1 per cent and in 2011 it was 24,8 per cent and the WB is presenting that the poverty headcount was 25,2 per cent in Nepal by 2010 (UN 2015, WB 2015). The poverty headcount within Nepal has decreased by 28,3 per cent within the last 8 years, while the total number of labour migrants from Nepal has increased by nearly 250 per cent during the last 10 years. Accordingly to my calculations by using Adams idea, and with the two year of missing information of poverty headcount for Nepal in mind, this should be equivalent to 52,5 per cent decline of poverty headcount for Nepal. The poverty headcount within Nepal should have shrunk to approximately 6,838,350. At the same time, accordingly to UN, the total poverty headcount at 2011 was 6,735,680 in Nepal. The calculation is a possible consideration that could be of further investigation, although the calculation is not stating that migration solely have made this poverty headcount decline possible within Nepal, but it has definitely been a key process in the total decline.