An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.35(2); 2020 Mar

Implications of Language Barriers for Healthcare: A Systematic Review

Hilal al shamsi.

1 Director of Planning and Studies, Directorate General of Planning and Studies, Ministry of Health, Al Buraimi, Oman

Abdullah G. Almutairi

2 Director of Tumair Hospital, Ministry of Health, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Sulaiman Al Mashrafi

3 Directorate General of Planning and Studies, Department of Health Information and Statistics, Ministry of Health, Muscat, Oman

Talib Al Kalbani

4 Director of Pharmaceutical Care and Medical Stores, Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health, Al Buraimi, Oman

Language barriers pose challenges in terms of achieving high levels of satisfaction among medical professionals and patients, providing high- quality healthcare and maintaining patient safety. To address these challenges, many larger healthcare institutions offer interpreter services to improve healthcare access, patient satisfaction, and communication. However, these services increase the cost and duration of treatment. The purpose of this review is to investigate the impact of language barriers on healthcare and to suggest solutions to address the challenges.

We identified published studies on the implications of language barriers in healthcare using two databases: PubMed and Medline. We included 14 studies that met the selection criteria. These studies were conducted in various countries, both developed and developing, though most came from the US. The 14 studies included 300 918 total participants, with participation in each study ranging from 21 to 22 353 people.

We found that language barriers in healthcare lead to miscommunication between the medical professional and patient, reducing both parties’ satisfaction and decreasing the quality of healthcare delivery and patient safety. In addition, the review found that interpreter services contribute indirectly to increased cost and the length of treatment visits. One study reported the implementation of online translation tools such as Google Translate and MediBabble in hospitals, which increased the satisfaction of both medical providers and patients (to 92%) and improved the quality of healthcare delivery and patient safety. Language barriers are responsible for reducing the satisfaction of medical providers and patients, as well as the quality of healthcare delivery and patient safety. Many healthcare institutions use interpreter services that increase the cost and length of treatment visits.

Conclusions

The results of our review suggest that implementing online translation tools such as Google Translate and MediBabble may improve the quality of healthcare and the level of satisfaction among both medical providers and patients.

Introduction

Language barriers have a major impact on the cost and quality of healthcare. They commonly occur between healthcare providers and patients when the two groups do not share a native language. 1 Regardless of language barriers, healthcare providers are required to deliver high-quality healthcare that adheres to the principles of human rights and equity to all their patients. 2

Health disparities such as unequal treatment related to language barriers are associated with unequal access to healthcare and unequal health outcomes. 3 For instance, a recent study demonstrated that patients who do not speak the local language are disadvantaged in terms of access to healthcare services. 4 Similarly, several studies have shown that patients who face language barriers have poorer health outcomes compared with patients who speak the local language. 5 , 6

Growing evidence documents the fact that language barriers indirectly impact the quality of the healthcare that patients receive. Language barriers contribute to reducing both patient and medical provider satisfaction, as well as communication between medical providers and patients. Patients who face language barriers are more likely to consume more healthcare services 2 and experience more adverse events. 7 A recent study conducted in six hospitals in the US found that adverse events occurred more frequently among patients with limited proficiency in English than among those who were proficient in English.

This review investigates the impact of language barriers on healthcare and suggests solutions to address the challenges.

We identified studies of the impact of language barriers on the delivery of healthcare by searching the PubMed and Medline databases using the keywords: ‘language barriers,’ ‘satisfaction,’ ‘healthcare,’ ‘limited English proficiency,’ ‘quality of care,’ ‘communication,’ and ‘access to health services’.

This review includes studies that address the impact of language barriers on the delivery of healthcare. It excludes studies into the impacts of communication barriers other than language barriers on the delivery of healthcare, studies that were not primarily conducted in healthcare organizations, and non-peer-reviewed articles. The search strategy was limited to articles published from 2000 to 2019 to find the most recent literature on the topic.

The extracted data are summarized in two tables. Table 1 outlines the general characteristics of the studies, including the country in which the study was done, the total number of organizations in which the sample was collected, the type of organization that conducted the study, the study type, the data collection method, the sample size, and the response rate. Table 2 presents the implication of language barriers on the delivery of healthcare in each study in the review.

*MOH: Ministry of Health; NA: not applicable; NR: not recorded.

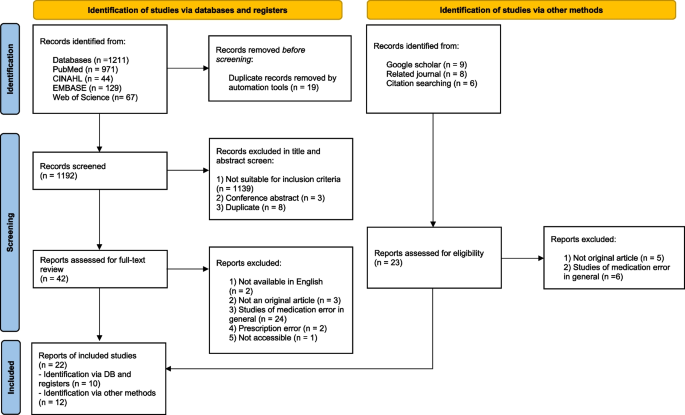

Figure 1 shows the researcher’s method of selecting eligible studies for this review. Initially, the researcher’s search of the PubMed and Medline databases returned 2569 articles. After removing the duplicate articles, 1211 remained. Next, the researcher excluded the articles that were not mainly about language barriers (n = 605) and the non-peer-reviewed articles (n = 532). Then the researcher excluded those studies that were not primarily conducted in healthcare organizations (n = 60), leaving 14 articles to be included in this systematic review.

The process of selecting the included 14 studies in this review.

Table 1 presents a summary of the general characteristics of the 14 studies arranged by the authors’ names. Nine studies used a cross-sectional design, two used a prospective design, two used qualitative research, and one was a report. Five studies collected data from an interview survey, three used questionnaires, one used both an interview survey and questionnaires, three used hospital databases, and two used telephone and mail surveys. Five of the studies were conducted in the US, two in Saudi Arabia, two in Switzerland, and one each in Canada, Germany, England, Norway, and South Africa. The total number of participants in the 14 studies was 300 918, with the number of participants in each study ranging from 21 to 22 353.

Table 2 presents the most important findings of the 14 studies in this review. Seven of the studies focused on language barriers and patient satisfaction, two on the impact of language barriers on healthcare provider satisfaction, one on the impact of language barriers on both healthcare providers and patient satisfaction, two on the cost of interpretation services, one on the quality of interpretation services, and one on online translation tools. The findings of studies can be divided into three categories: the impact of language barriers on medical providers (such as physicians and nurses), patients, and the cost and quality of healthcare services.

Communication between patients and medical providers is at the heart of effective healthcare. In Pytel, 17 94.3% of nurses reported that it was very important for their work environment and communication to understand the language of their patients. Physicians also have difficulty understanding patients who do not speak their language, leading to wrong diagnosis and medications. 18 In Norway, medical providers reported that they had trouble understanding between 36% and 43% of the patients who do not speak the local language, necessitating interpreters. 15 Indeed, 37% of physicians indicated that they felt that patients hide some information because of language barriers. 15 In addition, all South African nurses in Saudi Arabia had difficulty communicating with patients and their family members, as well as nurses from other countries, because of language barriers. 19

Language barriers have negative implications for the delivery of healthcare and patient satisfaction. One study showed that among patients who received treatment from nurses who did not speak the local language, 30% had difficulty understanding medical instructions, 30% had a problem with the reliability of information, and 50% believed that the language barrier contributed to errors. 10 Other studies found that among patients who did not speak the local language, 49% had trouble understanding a medical situation, 34.7% were confused about how to use medication, 41.8% had trouble understanding a label on medication, 15.8% had a bad reaction to medication due to a problem understanding their healthcare provider’s instructions, 20 66.7% faced a barrier when accessing healthcare, and 20% did not seek healthcare services if these were not readily available for fear of not understanding their healthcare provider. 14 Furthermore, many patients with limited local language proficiency experienced adverse health events that resulted in detectable physical harm (49.1% of patients) or moderate temporary harm (46.8%) or experienced some failure in communication with medical providers (52.4%). 5 Patients with limited local language proficiency are also likely to miss medical appointments and have difficulties arranging appointments due to the language barrier. 9 Therefore, these patients have a poor level of satisfaction with their healthcare. 14 , 18

To increase patient satisfaction with healthcare, it is necessary to provide interpreter services. Two studies pointed out that medical providers needed interpreter services for 43.2% of their patients, and 21–76% of medical providers stated they had poor access to these services. 12 , 15 Moreover, 70.7% of limited English proficiency patients (LEPPs) reported limited availability of interpreter services, 13 , 14 and 26.4% reported that there were no interpreters in their healthcare institutions. 2 LEPPs also indirectly raise the cost of health services when they use interpreter services. 12 LEPPs who used interpreter services received more inpatient services and attended more office visits than those who did not. 11 The authors of this study estimated that interpreter services for Medicaid recipients at about $4.7 million annually. Some healthcare organizations use online translation tools such as Google Translate and MediBabble to address the challenges of language barriers. These tools are free and easy to access, and they contribute to improving healthcare delivery, patient safety, and increased (up to 92%) the satisfaction of both medical professionals and patients. 8

This review investigates the impact of language barriers on the delivery of healthcare and identifies possible solutions to the challenges posed by these language barriers. The first impact of language barriers is miscommunication between medical providers (physicians and nurses) and patients [ Table 2 ]. This miscommunication contributes to a reduction in the satisfaction of both medical providers and patients, the quality of healthcare delivery, and patient safety. The second impact is an increase in indirect healthcare costs. The final impact is the application of online translation tools to healthcare organizations, which improves the quality of healthcare delivery and patient safety and increases the satisfaction of both medical professionals and patients.

Language barriers are a key cause of miscommunication between medical providers and patients, and negatively affect the quality of healthcare services and patient satisfaction. Hospital medical professionals perceive language barriers to be a source of workplace stress and an impediment to the delivery of high-quality healthcare. 21 Much evidence shows a significant association between workplace stress and lower satisfaction among medical providers. 22 - 24 In addition, studies indicate that language barriers contribute to medical professionals’ incomplete understanding of patients’ situations, delayed treatment or misdiagnoses, poor patient assessment and incomplete prescribed treatment. 14 , 25

We also found that patients who do not speak the local language will have less satisfaction with their healthcare and less access to usual sources of healthcare. Even when patients with language barriers have access to healthcare, they have decreased satisfaction with that healthcare, decreased understanding of their diagnoses, and increased medication complications. 25 , 26 A study conducted in Saudi Arabia showed that 25% of foreign patients reported that they had difficulty communicating with medical professionals and decreased satisfaction with their healthcare; 20% of medical professionals reported that health outcomes (i.e., healthcare errors, understanding patient needs, feeling satisfaction, and trust in nursing care needs) were always affected by language barriers. 27 Interpreter services are necessary to solve the problem of language barriers in healthcare institutions and to increase the satisfaction of both medical professionals and patients.

To overcome language barriers, some healthcare institutions provide interpreter services; however, these services pose critical challenges in terms of access and financial burden. Previous studies have shown that most healthcare institutions have poor access to interpreter services or no services at all. 12 , 14 The use of interpreter services contributes to increased patient satisfaction and improved patient care among patients with language barriers. 28 Interpreter services have a significant association with increased physician visits, prescription drugs by physicians, and receipt of preventative services among patients. 29 However, providing interpreter services also increases the length and cost of physician visits.

MediBabble is an application created by medical students at the University of California, San Francisco, and released in 2011. Using advanced voice recognition software, it offers translations for thousands of medical instructions, as well as the questions for a standard medical history. 30 , 31 The application contains thousands of instructions and translated questions, organized by symptom. Most questions can be answered with ‘yes’ or ‘no’ gestures. 32 MediBabble can be used online or offline, and it allows physicians to take patient histories and make diagnoses when a language barrier exists. 32 However, the application translates only six languages: English, Spanish, Russian, Cantonese, Haitian Creole, and Mandarin. 32

A case study showed that medical professionals and patients were highly satisfied with MediBabble; they reported that the application was fast and easy in terms of translating and collecting information. 33 In a study done in Canada, MediBabble was used as one strategy to improve the delivery of healthcare for resettled Syrian refugees. It allowed medical professionals to take the refugees’ histories and also make diagnoses. 30 In brief, MediBabble shows success as a medical translator. Using both interpreter services and online translation tools may offer more opportunities to improve healthcare delivery and patient safety.

This review has some limitations. First, there are few existing studies on the application of online translation tools in healthcare to address the problem of language barriers. Second, there are few studies evaluating the challenges of language barriers in private healthcare organizations. The impact of language barriers must be evaluated in both the public and the private sectors to address this problem.

This review also has several strengths. First, studies included in the review were conducted in both developing and developed countries. Second, the response rate was 100% in six of the studies. Third, the studies focused on various aspects of language barriers in healthcare, which helped the researchers to evaluate the challenges from multiple angles and determine solutions.

Language barriers can make the delivery of high-quality healthcare very challenging. They have a negative impact on the quality of healthcare, patient safety, and the satisfaction of medical professionals and patients. While some health organizations provide interpreter services to address these problems, these services indirectly increase the cost of health services and increase the length of treatment visits. Online translation tools such as Google Translate and MediBabble present possible solutions for overcoming these challenges. Further studies on the implications of language barriers and the effectiveness of online translation tools are recommended. Furthermore, new updates with more medical phrases for Google Translate and with more languages included for MediBabble application are recommended.

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Advertisement

Conceptualizing the Pathways and Processes Between Language Barriers and Health Disparities: Review, Synthesis, and Extension

- Original Paper

- Published: 12 December 2015

- Volume 19 , pages 215–224, ( 2017 )

Cite this article

- Sachiko Terui 1

4623 Accesses

30 Citations

4 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

While many may view language barriers in healthcare settings (LBHS) as a simple, practical problem, they present unique challenges to theoretical development and practice implications in healthcare delivery, especially when one considers the implications and impacts of specific contextual factors. By exploring the differences of contextual factors in the US and Japan, this review explores and highlights how such differences may entail different impacts on patients’ quality of care and require different solutions. I conduct narrative review through library database, Google Scholar, and CiNii (a Japanese library database) with multiple search terms, including language barriers, healthcare, medical interpreter, and immigrant. I first present a diagram to show the pathways and process between language barriers and health disparities, using the literature reported in the US. Then, I examined the literature reported in Japan and discuss the needs for re-conceptualizing LBHS. The implications for future research will be discussed.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Why cultural safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: a literature review and recommended definition

Elana Curtis, Rhys Jones, … Papaarangi Reid

Aboriginal community controlled health organisations address health equity through action on the social determinants of health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia

O. Pearson, K. Schwartzkopff, … on behalf of the Leadership Group guiding the Centre for Research Excellence in Aboriginal Chronic Disease Knowledge Translation and Exchange (CREATE)

The ABC of systematic literature review: the basic methodological guidance for beginners

Hayrol Azril Mohamed Shaffril, Samsul Farid Samsuddin & Asnarulkhadi Abu Samah

Karliner LS, Ma L, Hofmann M, Kerlikowske K. Language barriers, location of care, and delays in follow-up of abnormal mammograms. Med Care. 2012;50:171–8.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Schwei RJ, Del Pozo S, Agger-Gupta N, Alvarado-Little W, Bagchi A, Chen AH, et al. Changes in research on language barriers in health care since 2003: a cross-sectional review study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.03.001 .

PubMed Central Google Scholar

Timmins CL. The impact of language barriers on the health care of Latinos in the United States: a review of the literature and guidelines for practice. J Midwifery Women’s Health. 2002;47:80–96.

Article Google Scholar

Jacobs E, Chen AH, Karliner LS, Agger-Gupta N, Mutha S. The need for more research on language barriers in health care: a proposed research agenda. Milbank Q. 2006;84:111–33.

Diamond LC, Schenker Y, Curry L, Bradley EH, Fernandez A. Getting by: underuse of interpreters by resident physicians. JGIM. 2009;24:256–62.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Carrasquillo O, Orav EJ, Brennan TA, Burstin HR. Impact of language barriers on patient satisfaction in an emergency department. JGIM. 1999;14:82–7.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Flores G. Language barriers to health care in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:229–31.

Divi C, Koss RG, Schmaltz SP, Loeb JM. Language proficiency and adverse events in US hospitals: a pilot study. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:60–7.

Diamond LC, Jacobs EA. Let’s not contribute to disparities: the best methods for teaching clinicians how to overcome language barriers to health care. JGIM. 2010;25:189–93.

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Fernandez A, Schillinger D, Warton EM, Adler N, Moffet H, Schenker Y, et al. Language barriers, physician-patient language concordance, and glycemic control among insured Latinos with diabetes: the Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE). JGIM. 2011;26:170–6.

Sentell T, Braun KL, Davis J, Davis T. Colorectal cancer screening: low health literacy and limited English proficiency among Asians and Whites in California. J Health Commun. 2013;18:242–55.

Butow P, Bell M, Goldstein D, Sze M, Aldridge L, Abdo S, et al. Grappling with cultural differences; communication between oncologists and immigrant cancer patients with and without interpreters. Patient Educ Counsel. 2011;84:398–405.

Barber BR. Jihad vs. McWorld. New York: The Random House Publishing Group; 1995.

Google Scholar

Hofstede G. Culture’s consequences: international differences in work-related values. Beverly Hills: Sage; 1980.

Akabayashi A, Fetters MD, Elwyn TS. Family consent, communication, and advance directives for cancer disclosure: a Japanese case and discussion. J Med Ethics. 1999;25:296–301.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

De Jong G, Steinmetz M. Receptivity attitudes and the occupational attainment of male and female immigrant workers. Popul Res Policy Rev. 2004;23:91–116.

Prins E, Toso BW. Receptivity toward immigrants in rural Pennsylvania: perceptions of adult English as second language providers. Rural Sociol. 2012;77:435–61.

Green BN, Johnson CD, Adams A. Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: secrets of the trade. J Chiropr Med. 2006;5:101–17.

Baumeister RF, Leary MR. Writing narrative literature reviews. Rev Gener Psychol. 1997;1:311–20.

Gregg J, Saha S. Communicative competence: a framework for understanding language barriers in health care. JGIM. 2007;22:368–70.

Street RL Jr, Makoul G, Arora NK, Epstein RM. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician–patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74:295–301.

Campbell SM, Roland MO, Buetow SA. Defining quality of care. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51:1611–25.

Ndiaye K, Krieger JL, Warren JR, Hecht ML. Communication and health disparity. In: Thompson TL, Parrott R, Nussbaum JF, editors. The Routledge handbook of health communication. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Routledge; 2011. p. 469–81.

Kleinman A. Patients and healers in the context of culture: an exploration of the borderland between anthropology, medicine, and psychiatry. London: University of California Press; 1980.

Paasche-Orlow MK, Wolf MS. The causal pathways linking health literacy to health outcomes. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31:S19–26.

Institute of Medicine. Unequal treatment: what healthcare providers need to know about racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare. Institute of Medicine; 2002.

Piette JD, Bibbins-Domingo K, Schillinger D. Health care discrimination, processes of care, and diabetes patients’ health status. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60:41–8.

Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. J Behav Med. 2009;32:20–47.

Bradac JJ, Giles H. Language and social psychology: conceptual niceties, complexities, curiosities, monstrosities, and how it all works. In: Fitch KL, Sanders RE, editors. Handbook of language and social interaction. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2005. p. 201–30.

Stuber J, Meyer I, Link B. Stigma, prejudice, discrimination and health. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67:351–7.

Lambert WE, Hodgson RC, Gardner RC, Fillenbaum S. Evaluational reactions to spoken languages. J Abnorm Soc Psychol. 1964;60:44–51.

Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, Williams DR. Racism as a stressor for African Americans: a biopsychosocial model. Am Psychol. 1999;54:805.

Goffman E. Stigma: notes on the management of spoiled identity. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1963.

Thomas SB, Fine MJ, Ibrahim SA. Health disparities: the importance of culture and health communication. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:2050.

Youdelman MK. The medical tongue: U.S. laws and policies on language access. Health Aff. 2008;27:424–33.

DeCamp LR, Kieffer E, Zickafoose JS, DeMonner S, Valbuena F, Davis MM, et al. The voices of limited English proficiency Latina mothers on pediatric primary care: lessons for the medical home. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17:95–109.

Paasche-Orlow MK, Wilson EAH, McCormack L. The evolving field of health literacy research. J Health Commun. 2010;15:5–8.

Kuo DZ, O’Connor KG, Flores G, Minkovitz CS. Pediatricians’ use of language services for families with limited English proficiency. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e920–7.

Jang M, Lee E, Woo K. Income, language, and citizenship status: factors affecting the health care access and utilization of Chinese Americans. Health Soc Work. 1998;23:136–45.

Feinberg E, Swartz K, Zaslavsky A, Gardner J, Walker D. Language proficiency and the enrollment of Medicaid-eligible children in publicly funded health insurance programs. Matern Child Health J. 2002;6:5–18.

Conrad P, Barker KK. The social construction of illness: key insights and policy implications. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51:S67–79.

Ngo-Metzger Q, Sorkin DH, Phillips RS. Healthcare experiences of limited english-proficient asian american patients: a cross-sectional mail survey. Patient. 2009;2:113–20.

Woloshin S, Bickell NA, Schwartz LM, Gany F, Welch HG. Language barriers in medicine in the United States. JAMA. 1995;273:724–8.

Wilson E, Chen AH, Grumbach K, Wang F, Fernandez A. Effects of limited English proficiency and physician language on health care comprehension. JGIM. 2005;20:800–6.

John-Baptiste A, Naglie G, Tomlinson G, Alibhai SMH, Etchells E, Cheung A, et al. The effect of English language proficiency on length of stay and in-hospital mortality. JGIM. 2004;19:221–8.

Kravitz RL, Helms LJ, Azari R, Antonius D, Melnikow J. Comparing the use of physician time and health care resources among patients speaking English, Spanish, and Russian. Med Care. 2000;38:728–38.

Bernstein J, Bernstein E, Dave A, Hardt E, James T, Linden J, et al. Trained medical interpreters in the emergency department: effects on services, subsequent charges, and follow-up. J Immigr Health. 2002;4:171–6.

Sarver J, Baker D. Effect of language barriers on follow-up appointments after an emergency department visit. JGIM. 2000;15:256–64.

Goldenberg M. Defining, “quality of care” persuasively. Theor Med Bioeth. 2012;33:243–61.

Mutchler J, Bacigalupe G, Coppin A, Gottlieb A. Language barriers surrounding medication use among older Latinos. J Cross-Cult Gerontol. 2007;22:101–14.

Fernandez A, Schillinger D, Grumbach K, Rosenthal A, Stewart A, Wang F, et al. Physician language ability and cultural competence. JGIM. 2004;19:167–74.

Diamond LC, Reuland DS. Describing physician language fluency: deconstructing medical Spanish. JAMA. 2009;301:426–8.

Andrulis DP, Brach C. Integrating literacy, culture, and language to improve health care quality for diverse populations. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31:s122–33.

Messias DKH, McDowell L, Estrada RD. Language interpreting as social justice work: perspectives of formal and informal healthcare interpreters. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2009;32:128–43.

Baker DW, Parker RM, Williams MV, Coates WC, Pitkin K. Use and effectiveness of interpreters in an emergency department. JAMA. 1996;275:783–8.

Karliner LS, Jacobs EA, Chen AH, Mutha S. Do professional interpreters improve clinical care for patients with limited English proficiency? A systematic review of the literature. Health Serv Res. 2007;42:727–54.

Flores G, Abreu M, Barone CP, Bachur R, Lin H. Errors of medical interpretation and their potential clinical consequences: a comparison of professional versus ad hoc versus no interpreters. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60:545–53.

Drennan G, Swartz L. The paradoxical use of interpreting in psychiatry. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54:1853–66.

Flores G. The impact of medical interpreter services on the quality of health care: a systematic review. Med Care Res Rev. 2005;62:255–99.

Fagan MJ, Diaz JA, Reinert SE, Sciamanna CN, Fagan DM. Impact of interpretation method on clinic visit length. JGIM. 2003;18:634–8.

Abbe M, Simon C, Angiolillo A, Ruccione K, Kodish ED. A survey of language barriers from the perspective of pediatric oncologists, interpreters, and parents. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;47:819–24.

Ginde A, Clark S, Camargo C Jr. Language barriers among patients in Boston emergency departments: use of medical interpreters after passage of interpreter legislation. J Immigr Minor Health. 2009;11:527–30.

Jacobs E. A better measure of patients’ need for interpreter services. JGIM. 2008;23:1724–5.

Derose KP, Hays RD, McCaffrey DF, Baker DW. Does physician gender affect satisfaction of men and women visiting the emergency department? JGIM. 2001;16:218–26.

O’Leary SCB, Federico S, Hampers LC. The truth about language barriers: one residency program’s experience. Pediatrics. 2003;111:569.

Yawman D, McIntosh S, Fernandez D, Auinger P, Allan M, Weitzman M. The use of Spanish by medical students and residents at one university hospital. Acad Med. 2006;81:468–73.

Schenker Y, Wang F, Selig SJ, Ng R, Fernandez A. The impact of language barriers on documentation of informed consent at a hospital with on-site interpreter services. JGIM. 2007;22:294–9.

Andres E, Wynia M, Regenstein M, Maul L. Should I call an interpreter? How do physicians with second language skills decide? J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24:525–39.

Hsieh E. Not just “getting by”: factors influencing providers’ choice of interpreters. JGIM. 2015;30:75–82.

Rosenberg E, Seller R, Leanza Y. Through interpreters’ eyes: comparing roles of professional and family interpreters. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;70:87–93.

Karliner LS, Auerbach A, Napoles A, Schillinger D, Nickleach D, Perez-Stable EJ. Language barriers and understanding of hospital discharge instructions. Med Care. 2012;50:283–9.

Leyva M, Sharif I, Ozuah PO. Health literacy among Spanish-speaking Latino parents with limited English proficiency. Ambul Pediatr. 2005;5:56–9.

Wilson E, Chen AH, Grumbach K, Wang F, Fernandez A. Effects of limited English proficiency and physician language on health care comprehension. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:800–6.

Xu KT, Rojas-Fernandez CH. Ancillary community pharmacy services provided to older people in a largely rural and ethnically diverse region: a survey of consumers in West Texas. J Rural Health. 2003;19:79–86.

Westberg SM, Sorensen TD. Pharmacy-related health disparities experienced by non-English-speaking patients: impact of pharmaceutical care. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2005;45:48–54.

Sleath B. Pharmacists’ experiences in and perceptions toward serving the needs of Spanish-speaking patients in North Carolina community pharmacies. J Pharm Teach. 2002;9:77–91.

Muzyk AJ, Muzyk TL, Barnett CW. Counseling Spanish-speaking patients: Atlanta pharmacists’ cultural sensitivity, use of language-assistance services, and attitudes. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2003;44:366–74.

Ohtsuki S. Japanese views over the increase in foreigners: using JGSS-2003 data [Japanese]. 社会学論考. 2007;28:1–25.

Terasawa T. 英語以外の異言語に対する「日本人」の態度の社会統計的分析 [Japanese]. 東京大学大学院総合文化研究科言語情報科学専攻. 2014;3:91–107.

Takahashi M. The role of interpreters: from the perspectives of community interpreters [Japanese]. Tokyo University of Foreign Studies: Center for Multilingual Multicultural Education and Research; 2009, p. 50–62.

Iida N. The present condition and problems of community interpreters involved in the support system for returnees from China: a study of interpreter roles [Japanese]. 立命館人間科学研究. 2010;21:75–88.

Okubo T. The national health insurance program and illegal immigrants [Japanese]. 社会研論集. 2004;4:141–53.

Ueda A, Ogihara A, Yamaji M, Mitani H. Fact-finding survey on medical information for foreign residents on the web sites of local governments in Japan [Japanese]. Bull Soc Med. 2011;29:63–71.

Kawauchi K. Problems of medical interpreters in Japan [Japanese]. J Aomori Univ Health Welf. 2011;12:33–40.

Wakimoto T, Chisaki M, Uchida K. The perspectives of medical treatment provided to foreign individuals: the role of medical interpretors [Japanese]. J Pediatr Pract. 2013;76:971–5.

Hasegawa T, Takeda C, Tsukida K, Shirakawa K. A study of nursing care for foreigners in Japan [Japanese]. Fukui Med Res J. 2002;3:49–55.

Ministry of Justice. Statistics of foreign residents. 2014.

Maeno M, Enomoto N, Maeno R, Tamaki Y, Tanakamaru H, Fujihara A. The problem of foreign language translation and supporting for foreigners in clinics accepting foreigners [Japanese] 研究紀要. 2010:13–26.

Nakagawa K, Takuwa N. A study on the present status and prospect on medical care for foreign patients in Ishikawa Prefecture: based on a questionnaire survey for registered medical institutes for foreigners [Japanese]. Ishikawa J Nursing. 2012;9:23–32.

Non Profit Organization: Advanced Medical Promotion Organization. Large hospitals in Tokyo: thirty percent indicated the difficulty to accept patients with language barriers [Japanese]. 特定非営利活動団体 先端医療推進機構; 2013.

Park J-G. Foreign language edition home page: Chica city administration home page [Japanese]. 東京情報大学研究論集. 2007;10:11–20.

Abe Y. Necessity for community interpreters to manage mental illness [Japanese]. Tokyo University of Foreign Studies: Center for Multilingual Multicultural Education and Research. 2013, p. 105–113.

Arai K, Sasaki A, Sato C. 外国人妊産婦に対する産科病棟の対応 [Japanese]. 助産雑誌. 2006;60:355–60.

Miyabe M, Yoshino T, Shigeno A. Development of a multilngual medical reception support system based on parallel texts for foreign patients [Japanese]. 電子情報通信学会論文誌. 2009;J92-D:708–18.

Foundation of Global Health Care. Certification for bilingual medical staff (CBMS). 2014.

Iida N. The present condition and problems of medical interpreters for the foreigners living in Japan and visiting Japan [Japanese]. 立命館人間科学研究. 2011;23:47–57.

Usui S. Foreign residents’ experiences in the Japanese health care system and evaluation of their satisfaction [Japanese]: Tokyo Metropolitan University; 2013.

Schenker Y, Karter AJ, Schillinger D, Warton EM, Adler NE, Moffet HH, et al. The impact of limited English proficiency and physician language concordance on reports of clinical interactions among patients with diabetes: The DISTANCE study. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;81:222–8.

Kim KI, Park H-J, Suzuki N. Reward allocations in the United States, Japan, and Korea: a comparison of individualistic and collectivistic cultures. Acad Manag J. 1990;33:188–98.

Brown P, Levinson SC. Politeness: some universals in language usage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1987.

Akechi T, Miyashita M, Morita T, Okuyama T, Sakamoto M, Sagawa R, et al. Good death in elderly adults with cancer in Japan based on perspectives of the general population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:271–6.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Communication, University of Oklahoma, 610 Elm Ave. #211, Norman, OK, 73019, USA

Sachiko Terui

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sachiko Terui .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Terui, S. Conceptualizing the Pathways and Processes Between Language Barriers and Health Disparities: Review, Synthesis, and Extension. J Immigrant Minority Health 19 , 215–224 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-015-0322-x

Download citation

Published : 12 December 2015

Issue Date : February 2017

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-015-0322-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Language barriers

- The United States

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Implications of Language Barriers for Healthcare: A Systematic Review

Affiliations.

- 1 Director of Planning and Studies, Directorate General of Planning and Studies, Ministry of Health, Al Buraimi, Oman.

- 2 Director of Tumair Hospital, Ministry of Health, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

- 3 Directorate General of Planning and Studies, Department of Health Information and Statistics, Ministry of Health, Muscat, Oman.

- 4 Director of Pharmaceutical Care and Medical Stores, Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health, Al Buraimi, Oman.

- PMID: 32411417

- PMCID: PMC7201401

- DOI: 10.5001/omj.2020.40

Objectives: Language barriers pose challenges in terms of achieving high levels of satisfaction among medical professionals and patients, providing high- quality healthcare and maintaining patient safety. To address these challenges, many larger healthcare institutions offer interpreter services to improve healthcare access, patient satisfaction, and communication. However, these services increase the cost and duration of treatment. The purpose of this review is to investigate the impact of language barriers on healthcare and to suggest solutions to address the challenges.

Methods: We identified published studies on the implications of language barriers in healthcare using two databases: PubMed and Medline. We included 14 studies that met the selection criteria. These studies were conducted in various countries, both developed and developing, though most came from the US. The 14 studies included 300 918 total participants, with participation in each study ranging from 21 to 22 353 people.

Results: We found that language barriers in healthcare lead to miscommunication between the medical professional and patient, reducing both parties' satisfaction and decreasing the quality of healthcare delivery and patient safety. In addition, the review found that interpreter services contribute indirectly to increased cost and the length of treatment visits. One study reported the implementation of online translation tools such as Google Translate and MediBabble in hospitals, which increased the satisfaction of both medical providers and patients (to 92%) and improved the quality of healthcare delivery and patient safety. Language barriers are responsible for reducing the satisfaction of medical providers and patients, as well as the quality of healthcare delivery and patient safety. Many healthcare institutions use interpreter services that increase the cost and length of treatment visits.

Conclusions: The results of our review suggest that implementing online translation tools such as Google Translate and MediBabble may improve the quality of healthcare and the level of satisfaction among both medical providers and patients.

Keywords: Communication Barriers; Limited English Proficiency; Patient Satisfaction; Quality of Health Care.

The OMJ is Published Bimonthly and Copyrighted 2020 by the OMSB.

Publication types

- Open access

- Published: 26 July 2021

Impacts of English language proficiency on healthcare access, use, and outcomes among immigrants: a qualitative study

- Mamata Pandey 1 ,

- R. Geoffrey Maina 2 ,

- Jonathan Amoyaw 3 ,

- Yiyan Li 2 ,

- Rejina Kamrul 4 ,

- C. Rocha Michaels 4 &

- Razawa Maroof 4

BMC Health Services Research volume 21 , Article number: 741 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

29k Accesses

63 Citations

14 Altmetric

Metrics details

Immigrants from culturally, ethnically, and linguistically diverse countries face many challenges during the resettlement phase, which influence their access to healthcare services and health outcomes. The “Healthy Immigrant Effect” or the health advantage that immigrants arrive with is observed to deteriorate with increased length of stay in the host country.

An exploratory qualitative design, following a community-based research approach, was employed. The research team consisted of health researchers, clinicians, and community members. The objective was to explore the barriers to healthcare access among immigrants with limited English language proficiency. Three focus groups were carried out with 29 women and nine men attending English language classes at a settlement agency in a mid-sized city. Additionally, 17 individual interviews were carried out with healthcare providers and administrative staff caring for immigrants and refugees.

A thematic analysis was carried out with transcribed focus groups and healthcare provider interview data. Both the healthcare providers and immigrants indicated that limited language proficiency often delayed access to available healthcare services and interfered with the development of a therapeutic relationship between the client and the healthcare provider. Language barriers also impeded effective communication between healthcare providers and clients, leading to suboptimal care and dissatisfaction with the care received. Language barriers interfered with treatment adherence and the use of preventative and screening services, further delaying access to timely care, causing poor chronic disease management, and ultimately resulting in poor health outcomes. Involving untrained interpreters, family members, or others from the ethnic community was problematic due to misinterpretation and confidentiality issues.

Conclusions

The study emphasises the need to provide language assistance during medical consultations to address language barriers among immigrants. The development of guidelines for recruitment, training, and effective engagement of language interpreters during medical consultation is recommended to ensure high quality, equitable and client-centered care.

Peer Review reports

Major immigrant-destination countries like the United States, Germany, Canada, and Australia admit a large share of immigrants from culturally and linguistically diverse countries [ 1 ]. According to the 2016 Canadian Census, foreign-born individuals make up more than one-fifth (21.9%) of the Canadian population, which is close to the highest level (22.3%), recorded in the 1921 Census [ 2 ]. Most immigrants to Canada come from countries like the Philippines, India, China, Nigeria, and Pakistan, where most citizens’ first language is neither English nor French [ 3 , 4 , 5 ]. Individuals without local language proficiency are more likely to have lower income, and face considerable challenges with economic and social integration [ 6 , 7 , 8 ]. These settlement challenges increase the risk of poor health outcomes among newcomers with limited language proficiency [ 9 ]. Newcomers also face inequities in healthcare settings [ 10 ]. Due to immigration requirements, most newcomers are healthier than the general population, an effect referred to as the “healthy immigrant effect.” This effect is observed to decline over time [ 11 , 12 , 13 ]. Limited language proficiency is associated with decline in self-reported health status of new immigrants during the first 4 years of stay in Canada [ 9 ].

The ability to speak the host country’s official language proficiently appears to be an essential determinant of health [ 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 ]. The ability to speak, read, and write in the local language is necessary to communicate with healthcare providers and interact in other social settings [ 17 , 18 , 19 ]. Language is consistently identified as a barrier for immigrants and refugees seeking, accessing, and using mental health services [ 11 , 12 , 15 , 20 ]. Lee and colleagues [ 21 ] argued that Chinese immigrant women are more likely to choose service providers who speak the same language. Marshall, Wong, Haggerty, and Levesque [ 4 ] observed that Chinese- and Punjabi-speaking individuals with limited English language proficiency might delay accessing healthcare to find providers who speak their language. In the absence of culture-specific words and due to stigma, individuals from some ethnics groups may have difficulty describing mental health conditions or describe them as somatic symptoms [ 12 , 22 , 23 , 24 ]. Lack of language support or culturally appropriate services can interfere with timely mental health diagnosis and/or utilization of mental health services [ 12 , 23 , 24 ].

Language-incongruent encounters within the healthcare system increase the risk of inadequate communications, misdiagnosis, medication errors and complications, and even death [ 15 , 19 , 25 ]. Studies indicate that language barriers adversely affect health outcomes, healthcare access, utilization and cost of healthcare services, health-providers’ effectiveness, and patient satisfaction and safety [ 15 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 ].

Aery and colleagues [ 34 ] argue that the rights that allow individuals access to language interpreters in the justice system are also applicable in the healthcare context. Without language assistance, individuals with language barriers cannot engage in their treatment, determine risks and benefits of suggested treatment, and/or provide informed consent [ 34 , 35 ]. Human rights legislations in Canada have provided a framework and highlight the necessity to provide language interpreters when needed, but these have not been implemented universally [ 35 ]. Some provinces in Canada have launched language interpretation services. These services include: the Language Services Toronto in Ontario, language services for French-Canadians offered by Winnipeg Health Region in Manitoba and CanTalk telephonic interpreter services approved by the Saskatchewan Health Authority in Saskatchewan [ 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 ]. Professional interpreter services are not covered under most provincial health policies and therefore might not be available in all jurisdictions [ 3 ]. In the absence of universal interpretation services across the country, healthcare providers rely on professional interpreters, interpreters from community-based organizations and/or ad hoc (untrained) interpreters such as family members, friends, and volunteers who lack understanding of medical terminology and disease [ 3 , 36 , 37 , 38 ]. Although the services of professional language interpreters are employed in many Canadian healthcare settings, reliance on ad hoc interpreters, is preponderant [ 35 ]. This is partly due to a lack of trained interpreters in the language required and new immigrants’ lack of knowledge about available language supports [ 10 ]. Providers are also not comfortable with interpreters as it is time consuming, and providers might have different expectations about the roles of interpreters [ 3 ]. The impacts of local language proficiency on immigrants’ health and well-being are relevant and have been studied in other major immigrant-destination countries such as Australia, the United Kingdom, the United States of America [ 15 , 17 , 25 , 32 ].

This topic is particularly relevant in the Canadian context as 72.5% of immigrants are reported to have a mother tongue other than English or French according to the 2016 Census [ 39 ]. Given the unique history, culture, ethnic composition, and organization of healthcare services in Canada, scholars have highlighted the need for Canadian-based studies exploring how language barriers contribute to inefficiencies within the Canadian healthcare system and what strategies can be developed to address the gaps [ 10 , 15 ]. This study explores the impact of language barriers at each point of contact with the healthcare delivery system, from the perspective of immigrants and healthcare providers in a Canadian province that is witnessing a rapid influx of immigrants [ 2 ]. Taking a comprehensive approach, the study examined the overall impacts of language barriers on healthcare access, satisfaction with care received and health outcomes.

The study was set in a mid-size prairie city. An exploratory qualitative research approach guided by the principles of community-based research methods was adopted. Clinicians on the research team experienced many challenges while caring for both immigrants and refugees with language barriers. These clinicians approached community members for their perspective. The study idea was conceived after collective brainstorming with multi-sectoral stakeholders, including: representatives from a non-government settlement agency providing various settlement services to immigrants, family physicians caring for both immigrants and refugees in the city, and health researchers. Each stakeholder represented a specific ethnic-minority group and arrived in Canada as a landed immigrant. Through personal experiences and professional interactions with other immigrants, the stakeholders knew about barriers experienced during healthcare access.

Thereafter, stakeholders developed a research partnership. They collectively decided to document these challenges and leverage the research results to advocate for improved healthcare services. The study aim was to explore the perspectives of immigrants and of healthcare providers. Other groups, such as temporary migrant workers and refugees, have other unique challenges not within the scope of the study. Community partners assisted the research team to finalize the research question and determine methods of participant recruitment. The study was carried out in two parts and approved by the provincial health authority’s research ethics board (REB 14–122 and REB 15–69).

Participants

A purposeful sampling method was used. Community partners assisted with participant recruitment by engaging those seeking services through a settlement agency. All participants recruited were immigrants. The consent form and roles of research participants were shared with all 43 individuals attending English language classes at the settlement agency. Language assistance was provided by interpreters and the English language teachers facilitating the classes. Thirty-seven individuals (28 female and nine male) from 15 different countries signed consent forms. Three participants were travelling, two just began English language classes and one participant was not interested and were excluded. All participants lived in Canada for less than 6 years and are hereafter referred to as “clients.” Please refer to demographic information of clients in Table 1 .

Data collection

The focus group discussion (FGD) questions were developed in consultation with the settlement agency staff and focused on: a) the clients’ perceptions of health and the services needed to stay healthy; b) differences between the healthcare systems in the client’s country of origin and Canada; c) access to healthcare services; d) challenges clients faced when accessing care in Canada; and, e) how clients made decisions about healthcare. Clients received the questions before the FGD to organize their thoughts. Medical students representing specific ethnic groups and speaking an additional language assisted with data collection and interpretation during the FGDs.

Three FGDs were held at the settlement agency and lasted 2 h with breaks for refreshments. Each FGD was attended by 10–15 clients and subgroups of 3–4 clients were coordinated by a facilitator speaking the same language. Clients with language barriers were supported by facilitators speaking their language, other clients with advanced English language proficiency, or language interpreters.

Responses from clients were written down by facilitators and reread to the clients for accuracy. Some clients had written down their thoughts in English using online translators prior to the actual FGD to help them verbalise their thoughts with ease. Clients read out their responses during the FGDs and handed in those written notes after the FGDs. Facilitators also wrote field notes of the salient points emerging from these sessions and their reflections, which informed subsequent FGDs. None of the clients received services from any of the family physicians on the research team during data collection. Complementary child minding, light refreshments and a $20 gift card to a grocery store were provided as incentives to participate.

In part 2, healthcare providers’ perspectives on caring for immigrants and refugees were explored to show a more comprehensive view of the situation. Seventeen healthcare providers and health administrative staff signed the consent form: four family physicians, two family physicians providing obstetrical care, a psychiatrist, a registered nurse, a lab technician, a pharmacist, a nutritionist, a psychiatric social worker, a counsellor, an exercise therapist, an ultrasound technician, an executive director, and a receptionist. They were recruited from a community clinic that predominantly served refugees, immigrants, and other socio-economically disadvantaged populations in the city, other medical clinics in the city, and a hospital.

Healthcare providers serving immigrants and refugees participated in an hour-long, in-depth individual interview focusing on a) health services required to better address the healthcare needs of immigrants and refugees; b) the availability of culturally-responsive healthcare services; and c) the barriers to providing such care. Family physicians on the research team with extensive experience caring for immigrants and refugees assisted with the development of the interview guide and data collection. Interviews were carried out in English and were audio recorded. No compensation was provided.

The FGDs and healthcare provider interviews were transcribed verbatim. Data was analyzed qualitatively using NVivo version 9 following the procedure proposed by Miles, Huberman, and Saldana [ 40 , 41 ]. During preliminary data analysis, two rich transcripts were open coded by a team of researchers. Although the project was carried out to explore barriers to healthcare access for immigrants, language barriers emerged as a distinct theme impacting various aspects of care during data analysis. The results were shared with the settlement agency representatives. A collective decision was made to highlight the impacts of limited English language proficiency on healthcare access, utilization, and outcomes for immigrants in this manuscript. This framework guided the rest of the data analysis. The research team collectively reviewed the completed data analysis report and no new themes emerged at this discussion. The research team collectively agreed that further clarifications were not required from participants. Therefore, follow-up focus groups or interviews were not carried out and no new participants were recruited..

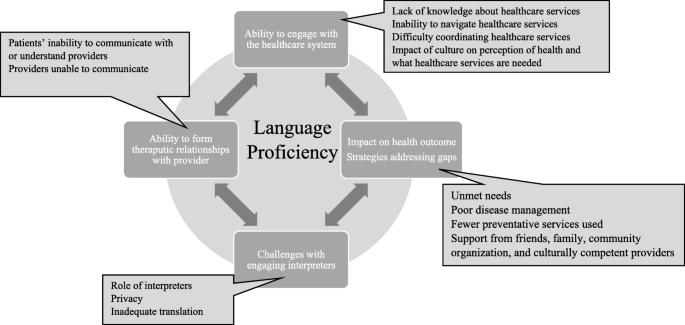

Data was broken into 120 base-level codes. The base-level codes were reviewed a second time, and codes with similar concepts were consolidated into 45 intermediate codes. The intermediate codes were categorized under 11 sub-themes. Title was assigned to each sub-theme to highlight the diverse and pertinent concepts represented by each sub-theme. The sub-themes were then organized under four central themes. Diagrammatic representation shows the relationship between the 11 sub-themes and the four themes and is illustrated in Fig. 1 . Field notes maintained by facilitators were used to cross-reference the themes emerging during data analysis to ensure all pertinent themes were included. The diagram demonstrating the relationship with the subthemes was approved by all team members.

Language Proficiency Leads to Poor Healthcare Access, Suboptimal Care, and Dissatisfaction with Care

Impacts of limited English language proficiency have been summarized under four main themes as follows.

Theme 1: ability to access health information and services

Language proficiency significantly impacted a client’s ability to identify services needed, to secure appointments, and to effectively engage with healthcare providers while seeking care and managing post-appointment care and follow-up. Information about healthcare services is usually provided in English or French. Thus, a client with language barriers lacked adequate information about available services and was unable to access services promptly. Clients with language barriers are less likely to actively seek health and/or mental health services when needed, as is evident from a client’s comment: “ No do not know about mental health services because of the language problem. Can I go to the hospital to access it?” [client]. Another client inquired: “ Do I need appointments for blood tests? ”

The range of healthcare services offered in different countries differs significantly. Lack of knowledge about existing healthcare services in the city created a barrier, which was greatly influenced by clients’ local language proficiency. A healthcare provider in the study commented that,

“We need to make the community or the clients’ population know that this is available for you and this is the process how you get access to this service, the language barrier is a huge barrier for this population and to access like any health care service.”

The way in which healthcare is organized and coordinated varies from country to country, and for newcomers, understanding the services provided within the host country largely depends on their ability to decipher information about them. Those with language limitations might not know how to access various healthcare services. This can lead to misunderstanding between the client and the provider, causing frustrations and unfulfilled expectations for both, as one healthcare provider noted:

“I offer free prescription delivery, but clients didn't come to the door, they didn't understand that the delivery person is delivering it and all they're doing is going to the door, ringing the doorbell expecting them to be let in. On numerous occasions, we were unsuccessful because they [clients] wouldn't open the door, there was no one there or-they did not understand, so, unless someone on the other end speaks English and tells us they're going to be there, we won't deliver now.”

Experience with healthcare delivery in clients’ countries of origin and cultural beliefs about health and what healthcare services should be accessed can interfere with their healthcare access. Language barriers may impede a client’s ability to understand the differences between healthcare organization in Canada and in their country of origin, leading to the underutilization of healthcare services, as one healthcare provider explained:

“If you don't know their language, it becomes difficult to provide care to them. Also, cultural beliefs can interfere with access to care. For example, they [immigrants and refugees with language barrier] do not know how to access an optometrist or dentist. So, I have to give them a lot of information as they have no idea.”

Due to language barriers, clients experienced difficulty following conversations with receptionists, providing proper documentation required for coordinating care, and booking and attending appointments. Clients with language barriers were less likely to seek clarifications when they did not understand instructions or to advocate for their needs. As one client noted, “I don’t speak good English. Therefore, sometimes it is difficult to understand what the receptionist is saying.”

Similarly, a health administrative staff mentioned “I am still waiting for the healthcare number from three clients. They [clients with language barrier] do not understand it is necessary for billing purposes ”.

The degree to which clients with limited language proficiency are able to access the healthcare services they need largely depends on their ability to understand information that is written in English and to understand how the healthcare system is organized.

Theme 2: ability to develop a therapeutic alliance with healthcare providers

English language proficiency significantly affected the therapeutic relationship between patients and healthcare providers. Clients with language barriers were unable to explain their health conditions adequately, as one client noted:

“Without proficiency in English, it is difficult talking to the health care provider. It's a problem to describe what you're feeling. It will be easier as a newcomer if they have a family doctor who speaks the same language. Like for children with pain, it is difficult for them to say what they [children] want or to make them [children] understand .”

Clients reported experiencing difficulty asking questions about their health and understanding treatment instructions. One client mentioned that,

“Sometimes, the doctors describe the illness in a way that I don’t understand what the doctors say. Sometimes this makes it very hard to go to the doctors because of the language problems.”

Healthcare providers were often concerned about not getting adequate information about health concerns from patients with language barriers. They experienced difficulties during physical examinations or when providing treatment instructions, which can have adverse outcomes, as one healthcare provider explained:

“Say I am treating an ear infection. I have told the clients many times that the medication is to be administered by mouth, but they thought it was to be installed in the ears. So, I have a couple of disastrous cases where I have prescribed medication where they don’t realize it is given by mouth. I think also, when they don’t understand, they feel uncomfortable to ask for clarification. They get very embarrassed and they get very frustrated.”

Similarly, clients with English language barriers also mentioned difficulty understanding medication regime as a client mentioned.

“I had problems with the iron levels, the doctors prescribed iron pills. I asked the doctors how many to take, but he did not explain it properly. He first said that I should take one pill a day, then when I ask if that will be enough, he said I can take 2 to 3 pills. How can he advise me like that without explaining it properly?”

Theme 3: challenges with engaging language interpreters

Language interpreters are not available at all clinics and families often bring ad hoc interpreters to the appointments or use volunteers working within the healthcare system. Often, these ad hoc interpreters lack adequate skills and training to carry out medical translation, which creates additional challenges. Healthcare providers may not feel confident that instructions are being translated verbatim. They also noted that often they received a summarized or concise version of what the clients narrated and wondered whether valuable contextual information was lost during translation. This can be frustrating for the healthcare providers and interfere with the development of the therapeutic alliance, as a healthcare provider pointed out:

“Some of the barriers I've experienced, those mainly had to do with communication and interpreters. I guess sometimes I wonder with the translation, what is being said to the patient. because they have quite a long discussion, and then when I ask the interpreter what was said … oh, they have no questions. *laughs* so I'm not sure what the conversation was, so that can be a little bit, um, frustrating.”

Further, some interpreters might provide a cultural and/or religious interpretation of strategies that might not align with Western medical care, as this healthcare provider explained:

“There are times when the clients will bring in their interpreters that I don't feel that my teaching and my advice is being given to them appropriately or word for word. I find that the personal interpreters they bring in will contraindicate and conflict with what I am telling the client because they will say "no that's not how we do things" instead of telling the client what I as a practitioner would like them to do”.

Sometimes, ad hoc interpreters are less helpful in assisting with client-provider communication and they may become an impediment to the therapeutic alliance, as a healthcare provider noted:

“Sometimes working with an interpreter is difficult because you don't always know whether the translator translates exactly what you're trying to come across or explain.”

Some clients were also concerned that their messages were not communicated properly to the healthcare providers during translation as a client mentioned:

“ I cannot speak English so I cannot go by myself to the doctor … … Before I had to wait for my husband he works, and say everything fast as he had to go back to work soon, I could not say everything I wanted, to the doctors, but now my son comes with me so it is better but I have to remind him always to say everything I said, to the doctor as he is still young and may forget .”

A medical interpreter’s presence can create privacy and confidentiality issues, especially for clients with mental health issues. Interpreters assisting clients with mental illness require training to create culturally safe interactions, lest the interaction become more injurious to the clients than the illness itself. The excerpt below from a healthcare provider is an excellent example of culturally unsafe medical translation.

“I had this case where the interpreter was not trained in mental health, and they found the conversation to be funny, so it was an elderly Asian lady who had delusions and hallucinations—well, we had a hard time with that. The interpreter was laughing.”

Some clients were uncomfortable receiving language assistance from family or individuals of the same community. As is mentioned by a women client:

“ I need lady doctor or lady speaking my language. I need medicine to stop baby [contraception] where can I get it. I cannot talk about this with my doctors when others [family members who help with translation] are there with me and I am waiting for 3 months now.”

Moreover, healthcare providers were sometimes concerned about the quality of the translation services provided to their clients. Healthcare providers observed that some interpreters struggled to explain instructions adequately during sample collection and diagnostics tests, leading to delays in the treatment process and linkage to treatment. One healthcare provider conveyed the issues with inadequate medical translation:

“I requested that the client present with a stool sample in the container provided. A couple of times, some clients showed up with urine in there rather than stool. This is after numerous explanations with an interpreter present.”

Another healthcare provider mentioned that:

“Giving simple instructions such as the need for a full bladder before ultrasound, many don’t understand what bladder is. Last week I tried to conduct spirometry on a patient even with the presence of an interpreter and I was not successful. He just didn't understand. I guess he [interpreter] did not translate accurately.”

Effective communication between healthcare providers and clients is vital for providing safe and quality healthcare.

Theme 4: impacts of language barriers on health outcome and strategies addressing gaps

Clients with language barriers often manage care on their own and due to lack of effective communication they are often dissatisfied with care received. Clients felt as though it was not worth seeking care when there was no means of addressing their language limitations, as one client noted:

“This country has so much resources and sometimes I feel the resources are not put to good use . What is the point of seeing a doctor if I do not feel satisfied? First, you must make appointments, manage everything at home to go for that appointment, and then still wait when you reach there, and then the doctors hardly spend time with you.”

In many countries healthcare is accessed on a need to basis and individuals might not have understanding about preventative health. Emphasis is given on preventative medicine in Canada, but providing health education can be challenging due to language barriers as a healthcare provider pointed out:

“If they don’t understand the preventative or the treatment plan but instead of perhaps doing some preventative stuff, they want to jump right to the surgery or jump right to the medication. Like PAP smears and mammograms, there is a lack of education in those countries where they come from. There are no concepts of preventative health care there. We tried to offer an information session with interpreters it really slowed down the meeting; everyone had to wait for the interpreter to interpret our directions and if we didn’t immediately have them interpret the participants were having a hard time following the conversation”

Healthcare providers were apprehensive about the dangers that clients with language barriers might face away from healthcare setting, as was explained by this healthcare provider:

“First of all, they [clients] might not understand what I'm telling them when I'm asking them to administer insulin themselves and increasing their doses based on their numbers. A lot of times they’re very confused on that fact and the translation, something is getting lost in the translation. Any misunderstanding can put them in a very dangerous situation if they give themselves too much insulin.”

Language ability can interfere with chronic disease management, which requires continual monitoring through regular clinic appointments. Even with medical translation, some clients may not comprehend the steps in the treatment plan that they are required to follow to manage chronic conditions effectively. Without additional supports available after medical appointments, these patients struggle to set up follow-up appointments, refill prescriptions, and adhere to medical instructions. In the absence of supports, treatment adherence might be poor. A healthcare provider describes what happens when clients don’t receive post-appointment follow-up or support:

“A lot of them [clients] have chronic conditions such as hypertension and don't come for a routine check-up. You'll see them and start them on medication and try to emphasize that this is long term treatment, and they will need to come back in a month for a check-up. You'll see that they've shown up a year later, and yet they were prescribed medications to last them for one month only and didn't renew them even though they had renewals. They will show up a year later with a headache or something, and their blood pressure is way out of control. I see that a lot.”

Clients mentioned adopting few strategies to address language barriers. Women clients often preferred same gender interpreters for women health issues and they depended on family and friend circles for assistance as a client mentioned: “ I have a very good friend who took holiday from work to come with me, I had to talk to the doctor about women problem .” Clients also consulted friends or family to find relevant healthcare services near them. A client mentioned: “I will ask my sister for healthcare for my family she and her family help us when we need information. I can also find out using the internet.” Clients might also seek information about healthcare services and ways to access it from community organizations providing settlement services as a client mentioned: “ I ask my English teacher when I need information about healthcare services they can help me. ”

Some clients pointed out that finding providers from their ethnic background would be helpful. Many clients take it upon themselves to seek care from these providers and may delay healthcare access, as this participant mentioned: “I am waiting to find a doctor who speak my language and can understand my culture.” Matching clients with providers from the same linguistic and ethnic background is useful but challenging. It may be more feasible in larger cities with larger and established ethnic groups. A client who received care from a provider from the same ethnic background mentioned a positive experience, as is evident from this comment:

“My doctor is from my country and he was able to explain to me why I need the surgery (hysterectomy). I was scared and I did not want to do it, but my husband and my doctor helped me understand that it was needed and if I did not get it done I will get very sick, I did it and I am alright now.”

Alternatively, healthcare providers who are culturally attuned to the challenges that clients with language barriers face are often empathetic and accommodative and ensure that clients receive the required care. One healthcare provider noted:

“They experience barriers accessing health care due to language limitations. Some clients may have challenges with conceptualizing what constitutes good health. This is partly informed by the fact that most of them may have experienced marginalization for so long. Therefore, [clients] might not have the right access to information or ask the right question. I try to talk to them at their level of understanding.”

Specialized clinics providing services to immigrants and refugees might have trained interpreters; however, their time might be limited, and they might not be available for healthcare services outside the clinics. One healthcare provider mentioned:

“We are lucky to have interpreters in our clinic but their time is limited and most of their time is allocated for in-person appointments in the clinics and they might not be available to provide support for other program such as health promotion.”

To achieve a positive treatment outcomes among immigrants with language barriers, effective coordination of care, good patient-provider communication and assistance with follow-up into the community post appointment are required. Lack of these ancillary services discourages individuals from accessing healthcare services. This is evident from a client’s comments:

“ I cannot speak English well and so cannot explain what I need I got so frustrated with the doctors did not go to see one in one whole year but that came to harm me. I now have pain in my ankle which is growing but what is the use of telling the doctors I cannot explain properly and they will not understand and it will not help .”

Individuals might delay access to healthcare which increases patients’ vulnerability to adverse health outcomes.

This study includes the perspectives of immigrants in a Canadian city and healthcare providers serving them. Consistent with the literature, both patients and providers unanimously agreed that limited English language proficiency significantly impacts access to care, quality of care received, and health outcomes for immigrants throughout the continuum of care [3, 10, 15–17, 26–29, 31, 33]. This study examined the impacts of language barriers at all points of contact with the healthcare delivery system. The study highlights that the impacts of language barriers are evident long before an individual meets with a healthcare provider and persist long after an individual has received a treatment or intervention. The cumulative impact of this is delayed access to timely healthcare, suboptimal care, increased risk of adverse events, dissatisfaction with care received and poor health outcomes. The study emphasizes that healthcare delivery in Canada cannot be improved by providing language interpreters during medical consultation alone. A more comprehensive approach is required that includes, developing best practice guidelines for providers, training for interpreters and policy change to address the impacts of language barriers on healthcare delivery, utilization and health outcomes in Canada. This study highlights four ways in which limited English language proficiency can interfere with immigrants’ healthcare access and health outcomes.

As observed by Floyd and Sakellariou [ 29 ], clients in our study were unaware of the available healthcare services, lacked knowledge about ways to navigate the healthcare system, and were unable to advocate for needed services [ 25 ]. Language barriers impacted clients’ engagement with prevention, health promotion, and allied health services, which can create the misperception that they are disengaged in care. Other studies have also identified that language barriers influence access to and use of preventative medicine and screening [ 30 , 42 , 43 , 44 ]. Language barriers interfere with the ability to find information about healthcare services and eligibility. This leads to fragmented, suboptimal care and/or delayed linkage with appropriate care [ 4 , 30 ].