How to Write a Research Paper: Parts of the Paper

- Choosing Your Topic

- Citation & Style Guides This link opens in a new window

- Critical Thinking

- Evaluating Information

- Parts of the Paper

- Writing Tips from UNC-Chapel Hill

- Librarian Contact

Parts of the Research Paper Papers should have a beginning, a middle, and an end. Your introductory paragraph should grab the reader's attention, state your main idea, and indicate how you will support it. The body of the paper should expand on what you have stated in the introduction. Finally, the conclusion restates the paper's thesis and should explain what you have learned, giving a wrap up of your main ideas.

1. The Title The title should be specific and indicate the theme of the research and what ideas it addresses. Use keywords that help explain your paper's topic to the reader. Try to avoid abbreviations and jargon. Think about keywords that people would use to search for your paper and include them in your title.

2. The Abstract The abstract is used by readers to get a quick overview of your paper. Typically, they are about 200 words in length (120 words minimum to 250 words maximum). The abstract should introduce the topic and thesis, and should provide a general statement about what you have found in your research. The abstract allows you to mention each major aspect of your topic and helps readers decide whether they want to read the rest of the paper. Because it is a summary of the entire research paper, it is often written last.

3. The Introduction The introduction should be designed to attract the reader's attention and explain the focus of the research. You will introduce your overview of the topic, your main points of information, and why this subject is important. You can introduce the current understanding and background information about the topic. Toward the end of the introduction, you add your thesis statement, and explain how you will provide information to support your research questions. This provides the purpose and focus for the rest of the paper.

4. Thesis Statement Most papers will have a thesis statement or main idea and supporting facts/ideas/arguments. State your main idea (something of interest or something to be proven or argued for or against) as your thesis statement, and then provide your supporting facts and arguments. A thesis statement is a declarative sentence that asserts the position a paper will be taking. It also points toward the paper's development. This statement should be both specific and arguable. Generally, the thesis statement will be placed at the end of the first paragraph of your paper. The remainder of your paper will support this thesis.

Students often learn to write a thesis as a first step in the writing process, but often, after research, a writer's viewpoint may change. Therefore a thesis statement may be one of the final steps in writing.

Examples of Thesis Statements from Purdue OWL

5. The Literature Review The purpose of the literature review is to describe past important research and how it specifically relates to the research thesis. It should be a synthesis of the previous literature and the new idea being researched. The review should examine the major theories related to the topic to date and their contributors. It should include all relevant findings from credible sources, such as academic books and peer-reviewed journal articles. You will want to:

- Explain how the literature helps the researcher understand the topic.

- Try to show connections and any disparities between the literature.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

More about writing a literature review. . .

6. The Discussion The purpose of the discussion is to interpret and describe what you have learned from your research. Make the reader understand why your topic is important. The discussion should always demonstrate what you have learned from your readings (and viewings) and how that learning has made the topic evolve, especially from the short description of main points in the introduction.Explain any new understanding or insights you have had after reading your articles and/or books. Paragraphs should use transitioning sentences to develop how one paragraph idea leads to the next. The discussion will always connect to the introduction, your thesis statement, and the literature you reviewed, but it does not simply repeat or rearrange the introduction. You want to:

- Demonstrate critical thinking, not just reporting back facts that you gathered.

- If possible, tell how the topic has evolved over the past and give it's implications for the future.

- Fully explain your main ideas with supporting information.

- Explain why your thesis is correct giving arguments to counter points.

7. The Conclusion A concluding paragraph is a brief summary of your main ideas and restates the paper's main thesis, giving the reader the sense that the stated goal of the paper has been accomplished. What have you learned by doing this research that you didn't know before? What conclusions have you drawn? You may also want to suggest further areas of study, improvement of research possibilities, etc. to demonstrate your critical thinking regarding your research.

- << Previous: Evaluating Information

- Next: Research >>

- Last Updated: Feb 13, 2024 8:35 AM

- URL: https://libguides.ucc.edu/research_paper

- Search This Site All UCSD Sites Faculty/Staff Search Term

- Contact & Directions

- Climate Statement

- Cognitive Behavioral Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Adjunct Faculty

- Non-Senate Instructors

- Researchers

- Psychology Grads

- Affiliated Grads

- New and Prospective Students

- Honors Program

- Experiential Learning

- Programs & Events

- Psi Chi / Psychology Club

- Prospective PhD Students

- Current PhD Students

- Area Brown Bags

- Colloquium Series

- Anderson Distinguished Lecture Series

- Speaker Videos

- Undergraduate Program

- Academic and Writing Resources

Writing Research Papers

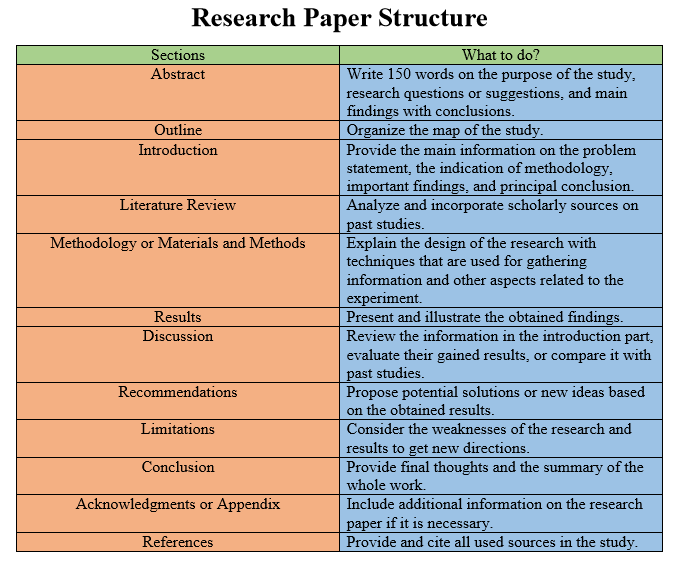

- Research Paper Structure

Whether you are writing a B.S. Degree Research Paper or completing a research report for a Psychology course, it is highly likely that you will need to organize your research paper in accordance with American Psychological Association (APA) guidelines. Here we discuss the structure of research papers according to APA style.

Major Sections of a Research Paper in APA Style

A complete research paper in APA style that is reporting on experimental research will typically contain a Title page, Abstract, Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion, and References sections. 1 Many will also contain Figures and Tables and some will have an Appendix or Appendices. These sections are detailed as follows (for a more in-depth guide, please refer to " How to Write a Research Paper in APA Style ”, a comprehensive guide developed by Prof. Emma Geller). 2

What is this paper called and who wrote it? – the first page of the paper; this includes the name of the paper, a “running head”, authors, and institutional affiliation of the authors. The institutional affiliation is usually listed in an Author Note that is placed towards the bottom of the title page. In some cases, the Author Note also contains an acknowledgment of any funding support and of any individuals that assisted with the research project.

One-paragraph summary of the entire study – typically no more than 250 words in length (and in many cases it is well shorter than that), the Abstract provides an overview of the study.

Introduction

What is the topic and why is it worth studying? – the first major section of text in the paper, the Introduction commonly describes the topic under investigation, summarizes or discusses relevant prior research (for related details, please see the Writing Literature Reviews section of this website), identifies unresolved issues that the current research will address, and provides an overview of the research that is to be described in greater detail in the sections to follow.

What did you do? – a section which details how the research was performed. It typically features a description of the participants/subjects that were involved, the study design, the materials that were used, and the study procedure. If there were multiple experiments, then each experiment may require a separate Methods section. A rule of thumb is that the Methods section should be sufficiently detailed for another researcher to duplicate your research.

What did you find? – a section which describes the data that was collected and the results of any statistical tests that were performed. It may also be prefaced by a description of the analysis procedure that was used. If there were multiple experiments, then each experiment may require a separate Results section.

What is the significance of your results? – the final major section of text in the paper. The Discussion commonly features a summary of the results that were obtained in the study, describes how those results address the topic under investigation and/or the issues that the research was designed to address, and may expand upon the implications of those findings. Limitations and directions for future research are also commonly addressed.

List of articles and any books cited – an alphabetized list of the sources that are cited in the paper (by last name of the first author of each source). Each reference should follow specific APA guidelines regarding author names, dates, article titles, journal titles, journal volume numbers, page numbers, book publishers, publisher locations, websites, and so on (for more information, please see the Citing References in APA Style page of this website).

Tables and Figures

Graphs and data (optional in some cases) – depending on the type of research being performed, there may be Tables and/or Figures (however, in some cases, there may be neither). In APA style, each Table and each Figure is placed on a separate page and all Tables and Figures are included after the References. Tables are included first, followed by Figures. However, for some journals and undergraduate research papers (such as the B.S. Research Paper or Honors Thesis), Tables and Figures may be embedded in the text (depending on the instructor’s or editor’s policies; for more details, see "Deviations from APA Style" below).

Supplementary information (optional) – in some cases, additional information that is not critical to understanding the research paper, such as a list of experiment stimuli, details of a secondary analysis, or programming code, is provided. This is often placed in an Appendix.

Variations of Research Papers in APA Style

Although the major sections described above are common to most research papers written in APA style, there are variations on that pattern. These variations include:

- Literature reviews – when a paper is reviewing prior published research and not presenting new empirical research itself (such as in a review article, and particularly a qualitative review), then the authors may forgo any Methods and Results sections. Instead, there is a different structure such as an Introduction section followed by sections for each of the different aspects of the body of research being reviewed, and then perhaps a Discussion section.

- Multi-experiment papers – when there are multiple experiments, it is common to follow the Introduction with an Experiment 1 section, itself containing Methods, Results, and Discussion subsections. Then there is an Experiment 2 section with a similar structure, an Experiment 3 section with a similar structure, and so on until all experiments are covered. Towards the end of the paper there is a General Discussion section followed by References. Additionally, in multi-experiment papers, it is common for the Results and Discussion subsections for individual experiments to be combined into single “Results and Discussion” sections.

Departures from APA Style

In some cases, official APA style might not be followed (however, be sure to check with your editor, instructor, or other sources before deviating from standards of the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association). Such deviations may include:

- Placement of Tables and Figures – in some cases, to make reading through the paper easier, Tables and/or Figures are embedded in the text (for example, having a bar graph placed in the relevant Results section). The embedding of Tables and/or Figures in the text is one of the most common deviations from APA style (and is commonly allowed in B.S. Degree Research Papers and Honors Theses; however you should check with your instructor, supervisor, or editor first).

- Incomplete research – sometimes a B.S. Degree Research Paper in this department is written about research that is currently being planned or is in progress. In those circumstances, sometimes only an Introduction and Methods section, followed by References, is included (that is, in cases where the research itself has not formally begun). In other cases, preliminary results are presented and noted as such in the Results section (such as in cases where the study is underway but not complete), and the Discussion section includes caveats about the in-progress nature of the research. Again, you should check with your instructor, supervisor, or editor first.

- Class assignments – in some classes in this department, an assignment must be written in APA style but is not exactly a traditional research paper (for instance, a student asked to write about an article that they read, and to write that report in APA style). In that case, the structure of the paper might approximate the typical sections of a research paper in APA style, but not entirely. You should check with your instructor for further guidelines.

Workshops and Downloadable Resources

- For in-person discussion of the process of writing research papers, please consider attending this department’s “Writing Research Papers” workshop (for dates and times, please check the undergraduate workshops calendar).

Downloadable Resources

- How to Write APA Style Research Papers (a comprehensive guide) [ PDF ]

- Tips for Writing APA Style Research Papers (a brief summary) [ PDF ]

- Example APA Style Research Paper (for B.S. Degree – empirical research) [ PDF ]

- Example APA Style Research Paper (for B.S. Degree – literature review) [ PDF ]

Further Resources

How-To Videos

- Writing Research Paper Videos

APA Journal Article Reporting Guidelines

- Appelbaum, M., Cooper, H., Kline, R. B., Mayo-Wilson, E., Nezu, A. M., & Rao, S. M. (2018). Journal article reporting standards for quantitative research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report . American Psychologist , 73 (1), 3.

- Levitt, H. M., Bamberg, M., Creswell, J. W., Frost, D. M., Josselson, R., & Suárez-Orozco, C. (2018). Journal article reporting standards for qualitative primary, qualitative meta-analytic, and mixed methods research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report . American Psychologist , 73 (1), 26.

External Resources

- Formatting APA Style Papers in Microsoft Word

- How to Write an APA Style Research Paper from Hamilton University

- WikiHow Guide to Writing APA Research Papers

- Sample APA Formatted Paper with Comments

- Sample APA Formatted Paper

- Tips for Writing a Paper in APA Style

1 VandenBos, G. R. (Ed). (2010). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (6th ed.) (pp. 41-60). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

2 geller, e. (2018). how to write an apa-style research report . [instructional materials]. , prepared by s. c. pan for ucsd psychology.

Back to top

- Formatting Research Papers

- Using Databases and Finding References

- What Types of References Are Appropriate?

- Evaluating References and Taking Notes

- Citing References

- Writing a Literature Review

- Writing Process and Revising

- Improving Scientific Writing

- Academic Integrity and Avoiding Plagiarism

- Writing Research Papers Videos

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Paper

Definition:

Research Paper is a written document that presents the author’s original research, analysis, and interpretation of a specific topic or issue.

It is typically based on Empirical Evidence, and may involve qualitative or quantitative research methods, or a combination of both. The purpose of a research paper is to contribute new knowledge or insights to a particular field of study, and to demonstrate the author’s understanding of the existing literature and theories related to the topic.

Structure of Research Paper

The structure of a research paper typically follows a standard format, consisting of several sections that convey specific information about the research study. The following is a detailed explanation of the structure of a research paper:

The title page contains the title of the paper, the name(s) of the author(s), and the affiliation(s) of the author(s). It also includes the date of submission and possibly, the name of the journal or conference where the paper is to be published.

The abstract is a brief summary of the research paper, typically ranging from 100 to 250 words. It should include the research question, the methods used, the key findings, and the implications of the results. The abstract should be written in a concise and clear manner to allow readers to quickly grasp the essence of the research.

Introduction

The introduction section of a research paper provides background information about the research problem, the research question, and the research objectives. It also outlines the significance of the research, the research gap that it aims to fill, and the approach taken to address the research question. Finally, the introduction section ends with a clear statement of the research hypothesis or research question.

Literature Review

The literature review section of a research paper provides an overview of the existing literature on the topic of study. It includes a critical analysis and synthesis of the literature, highlighting the key concepts, themes, and debates. The literature review should also demonstrate the research gap and how the current study seeks to address it.

The methods section of a research paper describes the research design, the sample selection, the data collection and analysis procedures, and the statistical methods used to analyze the data. This section should provide sufficient detail for other researchers to replicate the study.

The results section presents the findings of the research, using tables, graphs, and figures to illustrate the data. The findings should be presented in a clear and concise manner, with reference to the research question and hypothesis.

The discussion section of a research paper interprets the findings and discusses their implications for the research question, the literature review, and the field of study. It should also address the limitations of the study and suggest future research directions.

The conclusion section summarizes the main findings of the study, restates the research question and hypothesis, and provides a final reflection on the significance of the research.

The references section provides a list of all the sources cited in the paper, following a specific citation style such as APA, MLA or Chicago.

How to Write Research Paper

You can write Research Paper by the following guide:

- Choose a Topic: The first step is to select a topic that interests you and is relevant to your field of study. Brainstorm ideas and narrow down to a research question that is specific and researchable.

- Conduct a Literature Review: The literature review helps you identify the gap in the existing research and provides a basis for your research question. It also helps you to develop a theoretical framework and research hypothesis.

- Develop a Thesis Statement : The thesis statement is the main argument of your research paper. It should be clear, concise and specific to your research question.

- Plan your Research: Develop a research plan that outlines the methods, data sources, and data analysis procedures. This will help you to collect and analyze data effectively.

- Collect and Analyze Data: Collect data using various methods such as surveys, interviews, observations, or experiments. Analyze data using statistical tools or other qualitative methods.

- Organize your Paper : Organize your paper into sections such as Introduction, Literature Review, Methods, Results, Discussion, and Conclusion. Ensure that each section is coherent and follows a logical flow.

- Write your Paper : Start by writing the introduction, followed by the literature review, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. Ensure that your writing is clear, concise, and follows the required formatting and citation styles.

- Edit and Proofread your Paper: Review your paper for grammar and spelling errors, and ensure that it is well-structured and easy to read. Ask someone else to review your paper to get feedback and suggestions for improvement.

- Cite your Sources: Ensure that you properly cite all sources used in your research paper. This is essential for giving credit to the original authors and avoiding plagiarism.

Research Paper Example

Note : The below example research paper is for illustrative purposes only and is not an actual research paper. Actual research papers may have different structures, contents, and formats depending on the field of study, research question, data collection and analysis methods, and other factors. Students should always consult with their professors or supervisors for specific guidelines and expectations for their research papers.

Research Paper Example sample for Students:

Title: The Impact of Social Media on Mental Health among Young Adults

Abstract: This study aims to investigate the impact of social media use on the mental health of young adults. A literature review was conducted to examine the existing research on the topic. A survey was then administered to 200 university students to collect data on their social media use, mental health status, and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. The results showed that social media use is positively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. The study also found that social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) are significant predictors of mental health problems among young adults.

Introduction: Social media has become an integral part of modern life, particularly among young adults. While social media has many benefits, including increased communication and social connectivity, it has also been associated with negative outcomes, such as addiction, cyberbullying, and mental health problems. This study aims to investigate the impact of social media use on the mental health of young adults.

Literature Review: The literature review highlights the existing research on the impact of social media use on mental health. The review shows that social media use is associated with depression, anxiety, stress, and other mental health problems. The review also identifies the factors that contribute to the negative impact of social media, including social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO.

Methods : A survey was administered to 200 university students to collect data on their social media use, mental health status, and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. The survey included questions on social media use, mental health status (measured using the DASS-21), and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and regression analysis.

Results : The results showed that social media use is positively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. The study also found that social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO are significant predictors of mental health problems among young adults.

Discussion : The study’s findings suggest that social media use has a negative impact on the mental health of young adults. The study highlights the need for interventions that address the factors contributing to the negative impact of social media, such as social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO.

Conclusion : In conclusion, social media use has a significant impact on the mental health of young adults. The study’s findings underscore the need for interventions that promote healthy social media use and address the negative outcomes associated with social media use. Future research can explore the effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing the negative impact of social media on mental health. Additionally, longitudinal studies can investigate the long-term effects of social media use on mental health.

Limitations : The study has some limitations, including the use of self-report measures and a cross-sectional design. The use of self-report measures may result in biased responses, and a cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causality.

Implications: The study’s findings have implications for mental health professionals, educators, and policymakers. Mental health professionals can use the findings to develop interventions that address the negative impact of social media use on mental health. Educators can incorporate social media literacy into their curriculum to promote healthy social media use among young adults. Policymakers can use the findings to develop policies that protect young adults from the negative outcomes associated with social media use.

References :

- Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2019). Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study. Preventive medicine reports, 15, 100918.

- Primack, B. A., Shensa, A., Escobar-Viera, C. G., Barrett, E. L., Sidani, J. E., Colditz, J. B., … & James, A. E. (2017). Use of multiple social media platforms and symptoms of depression and anxiety: A nationally-representative study among US young adults. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 1-9.

- Van der Meer, T. G., & Verhoeven, J. W. (2017). Social media and its impact on academic performance of students. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 16, 383-398.

Appendix : The survey used in this study is provided below.

Social Media and Mental Health Survey

- How often do you use social media per day?

- Less than 30 minutes

- 30 minutes to 1 hour

- 1 to 2 hours

- 2 to 4 hours

- More than 4 hours

- Which social media platforms do you use?

- Others (Please specify)

- How often do you experience the following on social media?

- Social comparison (comparing yourself to others)

- Cyberbullying

- Fear of Missing Out (FOMO)

- Have you ever experienced any of the following mental health problems in the past month?

- Do you think social media use has a positive or negative impact on your mental health?

- Very positive

- Somewhat positive

- Somewhat negative

- Very negative

- In your opinion, which factors contribute to the negative impact of social media on mental health?

- Social comparison

- In your opinion, what interventions could be effective in reducing the negative impact of social media on mental health?

- Education on healthy social media use

- Counseling for mental health problems caused by social media

- Social media detox programs

- Regulation of social media use

Thank you for your participation!

Applications of Research Paper

Research papers have several applications in various fields, including:

- Advancing knowledge: Research papers contribute to the advancement of knowledge by generating new insights, theories, and findings that can inform future research and practice. They help to answer important questions, clarify existing knowledge, and identify areas that require further investigation.

- Informing policy: Research papers can inform policy decisions by providing evidence-based recommendations for policymakers. They can help to identify gaps in current policies, evaluate the effectiveness of interventions, and inform the development of new policies and regulations.

- Improving practice: Research papers can improve practice by providing evidence-based guidance for professionals in various fields, including medicine, education, business, and psychology. They can inform the development of best practices, guidelines, and standards of care that can improve outcomes for individuals and organizations.

- Educating students : Research papers are often used as teaching tools in universities and colleges to educate students about research methods, data analysis, and academic writing. They help students to develop critical thinking skills, research skills, and communication skills that are essential for success in many careers.

- Fostering collaboration: Research papers can foster collaboration among researchers, practitioners, and policymakers by providing a platform for sharing knowledge and ideas. They can facilitate interdisciplinary collaborations and partnerships that can lead to innovative solutions to complex problems.

When to Write Research Paper

Research papers are typically written when a person has completed a research project or when they have conducted a study and have obtained data or findings that they want to share with the academic or professional community. Research papers are usually written in academic settings, such as universities, but they can also be written in professional settings, such as research organizations, government agencies, or private companies.

Here are some common situations where a person might need to write a research paper:

- For academic purposes: Students in universities and colleges are often required to write research papers as part of their coursework, particularly in the social sciences, natural sciences, and humanities. Writing research papers helps students to develop research skills, critical thinking skills, and academic writing skills.

- For publication: Researchers often write research papers to publish their findings in academic journals or to present their work at academic conferences. Publishing research papers is an important way to disseminate research findings to the academic community and to establish oneself as an expert in a particular field.

- To inform policy or practice : Researchers may write research papers to inform policy decisions or to improve practice in various fields. Research findings can be used to inform the development of policies, guidelines, and best practices that can improve outcomes for individuals and organizations.

- To share new insights or ideas: Researchers may write research papers to share new insights or ideas with the academic or professional community. They may present new theories, propose new research methods, or challenge existing paradigms in their field.

Purpose of Research Paper

The purpose of a research paper is to present the results of a study or investigation in a clear, concise, and structured manner. Research papers are written to communicate new knowledge, ideas, or findings to a specific audience, such as researchers, scholars, practitioners, or policymakers. The primary purposes of a research paper are:

- To contribute to the body of knowledge : Research papers aim to add new knowledge or insights to a particular field or discipline. They do this by reporting the results of empirical studies, reviewing and synthesizing existing literature, proposing new theories, or providing new perspectives on a topic.

- To inform or persuade: Research papers are written to inform or persuade the reader about a particular issue, topic, or phenomenon. They present evidence and arguments to support their claims and seek to persuade the reader of the validity of their findings or recommendations.

- To advance the field: Research papers seek to advance the field or discipline by identifying gaps in knowledge, proposing new research questions or approaches, or challenging existing assumptions or paradigms. They aim to contribute to ongoing debates and discussions within a field and to stimulate further research and inquiry.

- To demonstrate research skills: Research papers demonstrate the author’s research skills, including their ability to design and conduct a study, collect and analyze data, and interpret and communicate findings. They also demonstrate the author’s ability to critically evaluate existing literature, synthesize information from multiple sources, and write in a clear and structured manner.

Characteristics of Research Paper

Research papers have several characteristics that distinguish them from other forms of academic or professional writing. Here are some common characteristics of research papers:

- Evidence-based: Research papers are based on empirical evidence, which is collected through rigorous research methods such as experiments, surveys, observations, or interviews. They rely on objective data and facts to support their claims and conclusions.

- Structured and organized: Research papers have a clear and logical structure, with sections such as introduction, literature review, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. They are organized in a way that helps the reader to follow the argument and understand the findings.

- Formal and objective: Research papers are written in a formal and objective tone, with an emphasis on clarity, precision, and accuracy. They avoid subjective language or personal opinions and instead rely on objective data and analysis to support their arguments.

- Citations and references: Research papers include citations and references to acknowledge the sources of information and ideas used in the paper. They use a specific citation style, such as APA, MLA, or Chicago, to ensure consistency and accuracy.

- Peer-reviewed: Research papers are often peer-reviewed, which means they are evaluated by other experts in the field before they are published. Peer-review ensures that the research is of high quality, meets ethical standards, and contributes to the advancement of knowledge in the field.

- Objective and unbiased: Research papers strive to be objective and unbiased in their presentation of the findings. They avoid personal biases or preconceptions and instead rely on the data and analysis to draw conclusions.

Advantages of Research Paper

Research papers have many advantages, both for the individual researcher and for the broader academic and professional community. Here are some advantages of research papers:

- Contribution to knowledge: Research papers contribute to the body of knowledge in a particular field or discipline. They add new information, insights, and perspectives to existing literature and help advance the understanding of a particular phenomenon or issue.

- Opportunity for intellectual growth: Research papers provide an opportunity for intellectual growth for the researcher. They require critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity, which can help develop the researcher’s skills and knowledge.

- Career advancement: Research papers can help advance the researcher’s career by demonstrating their expertise and contributions to the field. They can also lead to new research opportunities, collaborations, and funding.

- Academic recognition: Research papers can lead to academic recognition in the form of awards, grants, or invitations to speak at conferences or events. They can also contribute to the researcher’s reputation and standing in the field.

- Impact on policy and practice: Research papers can have a significant impact on policy and practice. They can inform policy decisions, guide practice, and lead to changes in laws, regulations, or procedures.

- Advancement of society: Research papers can contribute to the advancement of society by addressing important issues, identifying solutions to problems, and promoting social justice and equality.

Limitations of Research Paper

Research papers also have some limitations that should be considered when interpreting their findings or implications. Here are some common limitations of research papers:

- Limited generalizability: Research findings may not be generalizable to other populations, settings, or contexts. Studies often use specific samples or conditions that may not reflect the broader population or real-world situations.

- Potential for bias : Research papers may be biased due to factors such as sample selection, measurement errors, or researcher biases. It is important to evaluate the quality of the research design and methods used to ensure that the findings are valid and reliable.

- Ethical concerns: Research papers may raise ethical concerns, such as the use of vulnerable populations or invasive procedures. Researchers must adhere to ethical guidelines and obtain informed consent from participants to ensure that the research is conducted in a responsible and respectful manner.

- Limitations of methodology: Research papers may be limited by the methodology used to collect and analyze data. For example, certain research methods may not capture the complexity or nuance of a particular phenomenon, or may not be appropriate for certain research questions.

- Publication bias: Research papers may be subject to publication bias, where positive or significant findings are more likely to be published than negative or non-significant findings. This can skew the overall findings of a particular area of research.

- Time and resource constraints: Research papers may be limited by time and resource constraints, which can affect the quality and scope of the research. Researchers may not have access to certain data or resources, or may be unable to conduct long-term studies due to practical limitations.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Scientific and Scholarly Writing

- Literature Searches

- Tracking and Citing References

Parts of a Scientific & Scholarly Paper

Introduction.

- Writing Effectively

- Where to Publish?

- Capstone Resources

Different sections are needed in different types of scientific papers (lab reports, literature reviews, systematic reviews, methods papers, research papers, etc.). Projects that overlap with the social sciences or humanities may have different requirements. Generally, however, you'll need to include:

INTRODUCTION (Background)

METHODS SECTION (Materials and Methods)

What is a title

Titles have two functions: to identify the main topic or the message of the paper and to attract readers.

The title will be read by many people. Only a few will read the entire paper, therefore all words in the title should be chosen with care. Too short a title is not helpful to the potential reader. Too long a title can sometimes be even less meaningful. Remember a title is not an abstract. Neither is a title a sentence.

What makes a good title?

A good title is accurate, complete, and specific. Imagine searching for your paper in PubMed. What words would you use?

- Use the fewest possible words that describe the contents of the paper.

- Avoid waste words like "Studies on", or "Investigations on".

- Use specific terms rather than general.

- Use the same key terms in the title as the paper.

- Watch your word order and syntax.

The abstract is a miniature version of your paper. It should present the main story and a few essential details of the paper for readers who only look at the abstract and should serve as a clear preview for readers who read your whole paper. They are usually short (250 words or less).

The goal is to communicate:

- What was done?

- Why was it done?

- How was it done?

- What was found?

A good abstract is specific and selective. Try summarizing each of the sections of your paper in a sentence two. Do the abstract last, so you know exactly what you want to write.

- Use 1 or more well developed paragraphs.

- Use introduction/body/conclusion structure.

- Present purpose, results, conclusions and recommendations in that order.

- Make it understandable to a wide audience.

- << Previous: Tracking and Citing References

- Next: Writing Effectively >>

- Last Updated: Apr 17, 2024 3:27 PM

- URL: https://libraryguides.umassmed.edu/scientific-writing

The Plagiarism Checker Online For Your Academic Work

Start Plagiarism Check

Editing & Proofreading for Your Research Paper

Get it proofread now

Online Printing & Binding with Free Express Delivery

Configure binding now

- Academic essay overview

- The writing process

- Structuring academic essays

- Types of academic essays

- Academic writing overview

- Sentence structure

- Academic writing process

- Improving your academic writing

- Titles and headings

- APA style overview

- APA citation & referencing

- APA structure & sections

- Citation & referencing

- Structure and sections

- APA examples overview

- Commonly used citations

- Other examples

- British English vs. American English

- Chicago style overview

- Chicago citation & referencing

- Chicago structure & sections

- Chicago style examples

- Citing sources overview

- Citation format

- Citation examples

- College essay overview

- Application

- How to write a college essay

- Types of college essays

- Commonly confused words

- Definitions

- Dissertation overview

- Dissertation structure & sections

- Dissertation writing process

- Graduate school overview

- Application & admission

- Study abroad

- Master degree

- Harvard referencing overview

- Language rules overview

- Grammatical rules & structures

- Parts of speech

- Punctuation

- Methodology overview

- Analyzing data

- Experiments

- Observations

- Inductive vs. Deductive

- Qualitative vs. Quantitative

- Types of validity

- Types of reliability

- Sampling methods

- Theories & Concepts

- Types of research studies

- Types of variables

- MLA style overview

- MLA examples

- MLA citation & referencing

- MLA structure & sections

- Plagiarism overview

- Plagiarism checker

- Types of plagiarism

- Printing production overview

- Research bias overview

- Types of research bias

- Example sections

- Types of research papers

- Research process overview

- Problem statement

- Research proposal

- Research topic

- Statistics overview

- Levels of measurment

- Frequency distribution

- Measures of central tendency

- Measures of variability

- Hypothesis testing

- Parameters & test statistics

- Types of distributions

- Correlation

- Effect size

- Hypothesis testing assumptions

- Types of ANOVAs

- Types of chi-square

- Statistical data

- Statistical models

- Spelling mistakes

- Tips overview

- Academic writing tips

- Dissertation tips

- Sources tips

- Working with sources overview

- Evaluating sources

- Finding sources

- Including sources

- Types of sources

Your Step to Success

Plagiarism Check within 10min

Printing & Binding with 3D Live Preview

Parts of a Research Paper

How do you like this article cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Inhaltsverzeichnis

- 1 Parts of a Research Paper: Definition

- 3 Research Paper Structure

- 4 Research Paper Examples

- 5 Research Paper APA Formatting

- 6 In a Nutshell

Parts of a Research Paper: Definition

The point of having specifically defined parts of a research paper is not to make your life as a student harder. In fact, it’s very much the opposite. The different parts of a research paper have been established to provide a structure that can be consistently used to make your research projects easier, as well as helping you follow the proper scientific methodology.

This will help guide your writing process so you can focus on key elements one at a time. It will also provide a valuable outline that you can rely on to effectively structure your assignment. Having a solid structure will make your research paper easier to understand, and it will also prepare you for a possible future as a researcher, since all modern science is created around similar precepts.

Have you been struggling with your academic homework lately, especially where it concerns all the different parts of a research paper? This is actually a very common situation, so we have prepared this article to outline all the key parts of a research paper and explain what you must focus as you go through each one of the various parts of a research paper; read the following sections and you should have a clearer idea of how to tackle your next research paper effectively.

- ✓ Post a picture on Instagram

- ✓ Get the most likes on your picture

- ✓ Receive up to $300 cash back

What are the main parts of a research paper?

There are eight main parts in a research paper :

- Title (cover page)

Introduction

- Literature review

- Research methodology

- Data analysis

- Reference page

If you stick to this structure, your end product will be a concise, well-organized research paper.

Do you have to follow the exact research paper structure?

Yes, and failing to do so will likely impact your grade very negatively. It’s very important to write your research paper according to the structure given on this article. Follow your research paper outline to avoid a messy structure. Different types of academic papers have very particular structures. For example, the structure required for a literature review is very different to the structure required for a scientific research paper.

What if I'm having trouble with certain parts of a research paper?

If you’re having problems with some parts of a research paper, it will be useful to look at some examples of finished research papers in a similar field of study, so you will have a better idea of the elements you need to include. Read a step-by-step guide for writing a research paper, or take a look at the section towards the end of this article for some research paper examples. Perhaps you’re just lacking inspiration!

Is there a special formatting you need to use when citing sources?

Making adequate citations to back up your research is a key consideration in almost every part of a research paper. There are various formatting conventions and referencing styles that should be followed as specified in your assignment. The most common is APA formatting, but you could also be required to use MLA formatting. Your professor or supervisor should tell you which one you need to use.

What should I do once I have my research paper outlined?

If you have created your research paper outline, then you’re ready to start writing. Remember, the first copy will be a draft, so don’t leave it until the last minute to begin writing. Check out some tips for overcoming writer’s block if you’re having trouble getting started.

Research Paper Structure

There are 8 parts of a research paper that you should go through in this order:

The very first page in your research paper should be used to identify its title, along with your name, the date of your assignment, and your learning institution. Additional elements may be required according to the specifications of your instructors, so it’s a good idea to check with them to make sure you feature all the required information in the right order. You will usually be provided with a template or checklist of some kind that you can refer to when writing your cover page .

This is the very beginning of your research paper, where you are expected to provide your thesis statement ; this is simply a summary of what you’re setting out to accomplish with your research project, including the problems you’re looking to scrutinize and any solutions or recommendations that you anticipate beforehand.

Literature Review

This part of a research paper is supposed to provide the theoretical framework that you elaborated during your research. You will be expected to present the sources you have studied while preparing for the work ahead, and these sources should be credible from an academic standpoint (including educational books, peer-reviewed journals, and other relevant publications). You must make sure to include the name of the relevant authors you’ve studied and add a properly formatted citation that explicitly points to their works you have analyzed, including the publication year (see the section below on APA style citations ).

Research Methodology

Different parts of a research paper have different aims, and here you need to point out the exact methods you have used in the course of your research work. Typical methods can range from direct observation to laboratory experiments, or statistical evaluations. Whatever your chosen methods are, you will need to explicitly point them out in this section.

Data Analysis

While all the parts of a research paper are important, this section is probably the most crucial from a practical standpoint. Out of all the parts of a research paper, here you will be expected to analyze the data you have obtained in the course of your research. This is where you get your chance to really shine, by introducing new data that may contribute to building up on the collective understanding of the topics you have researched. At this point, you’re not expected to analyze your data yet (that will be done in the subsequent parts of a research paper), but simply to present it objectively.

From all the parts of a research paper, this is the one where you’re expected to actually analyze the data you have gathered while researching. This analysis should align with your previously stated methodology, and it should both point out any implications suggested by your data that might be relevant to different fields of study, as well as any shortcomings in your approach that would allow you to improve you results if you were to repeat the same type of research.

As you conclude your research paper, you should succinctly reiterate your thesis statement along with your methodology and analyzed data – by drawing all these elements together you will reach the purpose of your research, so all that is left is to point out your conclusions in a clear manner.

Reference Page

The very last section of your research paper is a reference page where you should collect the academic sources along with all the publications you consulted, while fleshing out your research project. You should make sure to list all these references according to the citation format specified by your instructor; there are various formats now in use, such as MLA, Harvard and APA, which although similar rely on different citation styles that must be consistently and carefully observed.

Paper printing & binding

You are already done writing your research paper and need a high quality printing & binding service? Then you are right to choose BachelorPrint! Check out our 24-hour online printing service. For more information click the button below :

Research Paper Examples

When you’re still learning about the various parts that make up a research paper, it can be useful to go through some examples of actual research papers from your exact field of study. This is probably the best way to fully grasp what is the purpose of all the different parts.

We can’t provide you universal examples of all the parts of a research paper, since some of these parts can be very different depending on your field of study.

To get a clear sense of what you should cover in each part of your paper, we recommend you to find some successful research papers in a similar field of study. Often, you may be able to refer to studies you have gathered during the initial literature review.

There are also some templates online that may be useful to look at when you’re just getting started, and trying to grasp the exact requirements for each part in your research paper:

Research Paper APA Formatting

When you write a research paper for college, you will have to make sure to add relevant citation to back up your major claims. Only by building up on the work of established authors will you be able to reach valuable conclusions that can be taken seriously on a academic context. This process may seem burdensome at first, but it’s one of the essential parts of a research paper.

The essence of a citation is simply to point out where you learned about the concepts and ideas that make up all the parts of a research paper. This is absolutely essential, both to substantiate your points and to allow other researchers to look into those sources in cause they want to learn more about some aspects of your assignment, or dig deeper into specific parts of a research paper.

There are several citation styles in modern use, and APA citation is probably the most common and widespread; you must follow this convention precisely when adding citations to the relevant part of a research paper. Here is how you should format a citation according to the APA style.

In a Nutshell

- There are eight different parts of a research paper that you will have to go through in this specific order.

- Make sure to focus on the different parts of a research paper one at a time, and you’ll find it can actually make the writing process much easier.

- Producing a research paper can be a very daunting task unless you have a solid plan of action; that is exactly why most modern learning institutions now demand students to observe all these parts of a research paper.

- These guidelines are not meant to make student’s lives harder, but actually to help them stay focused and produce articulate and thoughtful research that could make an impact in their fields of study.

We use cookies on our website. Some of them are essential, while others help us to improve this website and your experience.

- External Media

Individual Privacy Preferences

Cookie Details Privacy Policy Imprint

Here you will find an overview of all cookies used. You can give your consent to whole categories or display further information and select certain cookies.

Accept all Save

Essential cookies enable basic functions and are necessary for the proper function of the website.

Show Cookie Information Hide Cookie Information

Statistics cookies collect information anonymously. This information helps us to understand how our visitors use our website.

Content from video platforms and social media platforms is blocked by default. If External Media cookies are accepted, access to those contents no longer requires manual consent.

Privacy Policy Imprint

- Research guides

Writing an Educational Research Paper

Research paper sections, customary parts of an education research paper.

There is no one right style or manner for writing an education paper. Content aside, the writing style and presentation of papers in different educational fields vary greatly. Nevertheless, certain parts are common to most papers, for example:

Title/Cover Page

Contains the paper's title, the author's name, address, phone number, e-mail, and the day's date.

Not every education paper requires an abstract. However, for longer, more complex papers abstracts are particularly useful. Often only 100 to 300 words, the abstract generally provides a broad overview and is never more than a page. It describes the essence, the main theme of the paper. It includes the research question posed, its significance, the methodology, and the main results or findings. Footnotes or cited works are never listed in an abstract. Remember to take great care in composing the abstract. It's the first part of the paper the instructor reads. It must impress with a strong content, good style, and general aesthetic appeal. Never write it hastily or carelessly.

Introduction and Statement of the Problem

A good introduction states the main research problem and thesis argument. What precisely are you studying and why is it important? How original is it? Will it fill a gap in other studies? Never provide a lengthy justification for your topic before it has been explicitly stated.

Limitations of Study

Indicate as soon as possible what you intend to do, and what you are not going to attempt. You may limit the scope of your paper by any number of factors, for example, time, personnel, gender, age, geographic location, nationality, and so on.

Methodology

Discuss your research methodology. Did you employ qualitative or quantitative research methods? Did you administer a questionnaire or interview people? Any field research conducted? How did you collect data? Did you utilize other libraries or archives? And so on.

Literature Review

The research process uncovers what other writers have written about your topic. Your education paper should include a discussion or review of what is known about the subject and how that knowledge was acquired. Once you provide the general and specific context of the existing knowledge, then you yourself can build on others' research. The guide Writing a Literature Review will be helpful here.

Main Body of Paper/Argument

This is generally the longest part of the paper. It's where the author supports the thesis and builds the argument. It contains most of the citations and analysis. This section should focus on a rational development of the thesis with clear reasoning and solid argumentation at all points. A clear focus, avoiding meaningless digressions, provides the essential unity that characterizes a strong education paper.

After spending a great deal of time and energy introducing and arguing the points in the main body of the paper, the conclusion brings everything together and underscores what it all means. A stimulating and informative conclusion leaves the reader informed and well-satisfied. A conclusion that makes sense, when read independently from the rest of the paper, will win praise.

Works Cited/Bibliography

See the Citation guide .

Education research papers often contain one or more appendices. An appendix contains material that is appropriate for enlarging the reader's understanding, but that does not fit very well into the main body of the paper. Such material might include tables, charts, summaries, questionnaires, interview questions, lengthy statistics, maps, pictures, photographs, lists of terms, glossaries, survey instruments, letters, copies of historical documents, and many other types of supplementary material. A paper may have several appendices. They are usually placed after the main body of the paper but before the bibliography or works cited section. They are usually designated by such headings as Appendix A, Appendix B, and so on.

- << Previous: Choosing a Topic

- Next: Find Books >>

- Last Updated: Dec 5, 2023 2:26 PM

- Subjects: Education

- Tags: education , education_paper , education_research_paper

What are the 5 parts of the research paper

A regular research paper usually has five main parts, though the way it’s set up can change depending on what a specific assignment or academic journal wants. Here are the basic parts;

Introduction: This part gives an overview of what the research is about, states the problem or question being studied, and explains why the study is important. It often includes background info, context, and a quick look at the research to show why this study is needed.

Literature Review: In this part, the author looks at and summarizes existing research and writings on the chosen topic. This review helps spot gaps in what we already know and explains why a new study is necessary. It also sets up the theory and hypotheses for the research.

Methodology: The methodology section describes how the research was done – the plan, methods, and steps used to collect and analyze data. It should be detailed enough for others to repeat the study.

Results: This part shares what was found in the study based on the analyzed data. The results are often shown using tables, figures, and stats. It’s important to present the data accurately and without adding personal interpretations or discussions.

Discussion: Here, the results are explained in the context of the research question and existing literature. The discussion looks at what the findings mean, acknowledges any limits to the study, and suggests where future research could go. This is where the researcher can analyze, critique, and connect the results.

Besides these main sections, research papers usually have other parts like a title page, abstract, acknowledgments, and references. The structure might change a bit depending on the subject or type of research, but these five parts are generally found in academic research papers.

What is the structure of a research paper

A research paper usually follows a set format, including these parts:

Title Page: This page has the research paper’s title, the author’s name, where they’re affiliated (like a school), and often the date.

Abstract: The abstract is a short summary of the whole research paper. It quickly talks about the research question, methods, results, and conclusions. It’s usually limited to a specific number of words.

Introduction: This part introduces what the research is about. It states the main question, gives background info, and explains why the study is important. Often, it ends with a thesis statement or research hypothesis.

Literature Review: In this section, the author looks at and talks about other research and writings on the same topic. It helps to place the study in the context of what we already know, finding gaps, and explaining why this new research is needed.

Methodology: Here, the research plan is described. It explains how data was collected and analyzed, including details like who participated, what tools were used, and what statistical methods were applied. The goal is to provide enough info so others can do the same study.

Results: The results section shows what was found in the study based on the analyzed data. Tables, figures, and stats often help present the data. This part should be objective and report the results without personal interpretations.

Discussion: The discussion explains what the results mean in the context of the research question and existing literature. It looks at the implications of the findings, talks about any study limitations, and suggests where future research could go. This is where the author analyzes and connects the results.

Conclusion: The conclusion sums up the key findings of the study and stresses their importance. It might also suggest practical uses and areas for further investigation.

References (or Bibliography): This part lists all the sources cited in the paper, following a specific citation style like APA, MLA, or Chicago, as required by academic or publication guidelines.

Appendices: Extra materials, like raw data, questionnaires, or added info, can be put in the appendices.

Remember, the requirements for each section can vary based on the guidelines given by the instructor, school, or the journal where the paper might be published. Always check the specific requirements for the research paper you’re working on.

What are the 10 common parts of a research paper list in proper order

Here are the ten main parts of a research paper, listed in the right order:

Title Page: This page has the title of the research paper, the author’s name, where they’re affiliated (like a school), and the date.

Abstract: The abstract gives a short summary of the research, covering the main question, methods, results, and conclusions.

Introduction: This part introduces what the research is about. It states the main question, gives background info, and explains why the study is important.

Literature Review: In this section, the author looks at and talks about other research and writings on the same topic. It helps place the study in the context of what we already know and explains why this new research is needed.

Methodology: Here, the research plan is described. It explains how data was collected and analyzed, including details like who participated, what tools were used, and what statistical methods were applied.

Results: The results section shows what was found in the study based on the analyzed data. This part should be objective and report the results without personal interpretations.

Discussion: The discussion explains what the results mean in the context of the research question and existing literature. It looks at the implications of the findings, talks about any study limitations, and suggests where future research could go.

References (or Bibliography): This part lists all the sources cited in the paper, following a specific citation style as required by academic or publication guidelines.

Always check the specific requirements and guidelines given for the research paper you’re working on, as they can vary based on the instructor, school, or the journal where the paper might be published.

How long should a research paper be

The length of a research paper can vary a lot, depending on factors like the academic level, the type of research, and the specific instructions from the instructor or the target journal. Here are some general guidelines;

Undergraduate Level: Research papers at the undergraduate level, usually range from 10 to 20 pages, although this can change based on the requirements of the specific course.

Master’s Level: Master’s level research papers are generally longer, often falling between 20 to 40 pages. However, the length can vary depending on the subject and the program.

Ph.D. Level: Ph.D. dissertations or research papers are typically even longer, often going beyond 50 pages and sometimes reaching several hundred pages. The length is influenced by how deep and extensive the research is.

Journal Articles: For research papers meant for academic journal publication, the length is usually specified by the journal’s guidelines. In many cases, journal articles range from 5,000 to 8,000 words, but this can differ.

It’s really important to stick to the specific guidelines given by the instructor or the target journal. If there aren’t specific guidelines, think about how complex your research is and how in-depth your analysis needs to be to properly address the research question.

Also, some instructors might specify the length in terms of word count instead of pages. In these cases, the word count can vary, but a common range might be 2,000 to 5,000 words for undergraduate papers, 5,000 to 10,000 words for master’s level papers, and 10,000 words or more for Ph.D. dissertations.

What are 3 formatting guidelines from APA

The American Psychological Association (APA) has special rules for how to set up your research paper. Here are three important rules;

Title Page: Make a title page with the title of your paper, your name, and where you’re affiliated (like your school). Put the title in the middle, and your name and school below it in the middle too. In the top right corner, put a short version of the title and the page number.

In-Text Citations: When you mention a source in your paper, use the author’s last name and the year of publication in brackets. For example, if you talk about a book by Smith from 2020, you write (Smith, 2020). If you quote directly, add the page number too, like this: (Smith, 2020, p. 45).

References Page: Make a references page at the end listing all the sources you talked about in your paper. Arrange them alphabetically by the author’s last name. For books, use this format: Author, A. A. (Year of publication). Research Title: Capital letters also appear in the subheading. Publisher. For journal articles, it’s like this: Author, A. A. (Year of publication). Title of article. Title of Journal, volume number(issue number), page range. DOI or URL. Each entry should be indented right.

Remember, these are just a few important rules from APA. It’s crucial to check the official APA Publication Manual or the latest APA style guide for all the details and rules. Also, the rules might be a bit different for different types of sources, so pay attention to what APA says about each one.

What are the 4 major sections of a research paper

A research paper usually has four main parts;

Introduction: This part gets things started. It talks about what the research is about, gives some background info, and states the main question or idea. It’s important to show why the study matters.

Methods (or Methodology): The methods part explains how the research was done. It covers things like the plan, who took part, how data was collected, and how it was analyzed. The goal is to give enough detail so someone else could do the same study.

Results: The results section shows what was found in the research. It includes the raw data, stats, and any other info needed to answer the main question. It should be objective and focused on just reporting what happened, without adding personal thoughts.

Discussion: In the discussion part, the results are explained. It looks at what the findings mean in the context of the main question and other research. It talks about the impact of the results, mentions any study limits, and suggests where more research could go. This is where the researcher shares insights, makes conclusions, and talks about why the study is important.

Even though these four parts are common, the way they are set up can change. It depends on what the instructor, school, or journal wants. Always check the specific guidelines for the research paper you’re working on.

How do you write a reference page in APA format

In APA format, the reference page is super important in a research paper. It’s like a big list that shows all the sources mentioned in the paper. Here are the basic rules for making a reference page in APA format:

Heading: At the top, center the title “References” without making it bold, italicized, underlined, or using quotation marks.

Format for Entries: Each source follows a special format based on its type (like a book, journal article, or website).

For a book, the setup is

- Author, A. A. (Year of publication). Title of work: Capital letter also for subtitle. Publisher.

For a journal article, it’s

- Author, A. A. (Year of publication). Title of article. Title of Journal, volume number(issue number), page range. DOI or URL

Alphabetical Order: Organize the sources chronologically by the last name of the primary writer. If there’s no author, use the title for sorting, ignoring words like “A,” “An,” or “The.”

Hanging Indentation: Each entry has a hanging indentation. This means the first line starts on the left, and the following lines are indented by 0.5 inches.

Italicize Titles: Italicize the titles of bigger things like books and journals. For example: Title of the Book or Title of the Journal .

Use Proper Capitalization: Only capitalize the first word of the title, the first word after a colon in the subtitle, and any special names.

Remember these examples;

Book: Author, A. A. (Year of publication). Title of work: Capital letter also for subheading. Publisher.

Journal Article: Author, A. A. (Year of publication). Title of article. Title of Journal, volume number(issue number), page range. DOI or URL.

To make sure you get the latest information, check the APA rules.

What is the purpose of the Introduction section in a research paper

The Introduction section of a research paper serves several crucial purposes;

- Contextualization: It provides background information to help readers understand the broader context of the research. This may include the historical development of the topic, relevant theoretical frameworks, or existing gaps in knowledge.

- Problem Statement: The introduction outlines the specific problem or question that the research aims to address. It helps to articulate the gap in current knowledge or identify a need for further investigation.

- Justification and Significance: The section explains why the research is important and how it contributes to the existing body of knowledge. It highlights the potential impact and significance of the study.

- Objectives or Hypothesis: The introduction often states the research objectives or formulates a hypothesis, providing a clear roadmap for what the study aims to achieve or test.

- Scope and Limitations: It defines the boundaries of the research, outlining what the study includes and excludes. This helps readers understand the context within which the research findings should be interpreted.

- Research Questions: The introduction may pose specific questions that the research seeks to answer. These questions guide the reader in understanding the focus and purpose of the study.

- Overview of Methodology: While detailed methods are typically discussed in a separate section, the introduction may provide a brief overview of the research design, methods, and data collection techniques.

- Thesis Statement: In some cases, the introduction concludes with a concise thesis statement that encapsulates the main argument or purpose of the research paper.

Overall, the Introduction sets the stage for the research, engaging the reader’s interest, providing necessary context, and establishing the rationale for the study. It is a critical component that helps readers understand the importance of the research and motivates them to continue reading the paper.

How should the Literature Review be structured in a research paper

The structure of a literature review in a research paper typically follows a systematic and organized approach. Here’s a general guideline on how to structure a literature review;

Introduction

- Provide an overview of the topic and its significance.

- Clearly state the purpose of the literature review (e.g., identifying gaps, providing background).

- Mention the criteria used for including or excluding specific studies.

Organizing Themes or Categories

- Group relevant literature into themes or categories based on common themes, concepts, or methodologies.

- This could be chronological, thematic, methodological, or a combination, depending on the nature of the research.

Chronological Order

- If your topic has a historical development, consider presenting studies chronologically to show the evolution of ideas or research in the field.

Thematic Organization

- Group studies based on common themes, concepts, or theoretical frameworks. Each theme could represent a section in your literature review.

Methodological Approach

- Discuss studies based on their research methods. This can be particularly relevant if your research involves comparing or contrasting different methodologies.

Critical Analysis

- Critically evaluate each study, discussing its strengths and weaknesses.

- Identify patterns, inconsistencies, or gaps in the existing literature.

- Highlight the significance of each study to your research question or topic.

- Summarize the key findings and insights from each study.

- Discuss how the studies relate to one another and contribute to the overall understanding of the topic.

Gaps and Limitations

- Identify gaps in the literature and areas where further research is needed.

- Discuss the limitations of existing studies.

- Summarize the main points of the literature review.

- Emphasize the contribution of the literature review to your research.

- Provide a smooth transition to the next section of your research paper.

Remember to use clear and concise language throughout the literature review. Each section should flow logically, with a clear connection between paragraphs. Additionally, ensure that you cite all relevant studies and sources using the appropriate citation style (e.g., APA, MLA).

What information should be included in the Methodology section of a research paper

The Methodology section of a research paper provides a detailed description of the procedures and techniques used to conduct the study. It should offer sufficient information for other researchers to replicate the study and verify the results. Here’s a comprehensive guide on what information should be included in the Methodology section;

Research Design

- Specify the overall design of the study (e.g., experimental, observational, survey, case study).

- Justify why the chosen design is appropriate for addressing the research question.

Participants or Subjects

- Clearly describe the characteristics of the participants (e.g., demographics, sample size).

- Explain the criteria for participant selection and recruitment.

Sampling Procedure