Challenges of religious communities in European secular states and beyond Vol. 16 No. 2 (2023)

The theme of secularism and its impact on religious freedom is an important one. This issue builds on our previous issue on secularism from 2020, “ Responding to secularism ,” vol 13(1/2). This issue explores the challenges of secularism from legal, political and statistical perspectives. This provides a rich array of perspectives.

We are pleased to welcome two guest editors from the Evangelische Theologische Faculteit (ETF) in Leuven, Belgium for this issue. Prof Dr Jelle Creemers is Dean and Professor of the Department of Religious Studies and Missiology. Dr Tatiana Kopaleishvili is an Affiliated Researcher in Religious Studies and Missiology. As they explain below, the papers in this special issue come from their annual conferences addressing religious freedom issues. As a journal dedicated to religious freedom, we are grateful for the work of the ETF in Leuven!

As usual, we have a good variety of book reviews and our regular Noteworthy section highlighting current reports on religious freedom from around the world.

Yours for religious freedom,

Prof Dr Janet Epp Buckingham Executive Editor

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on religious minorities Vol. 16 No. 1 (2023)

The COVID-19 pandemic was more than a health crisis; it had a disproportionate impact on minorities, including religious minorities. We are pleased to publish this special issue on religious freedom in the age of COVID-19. It is a timely analysis of the crisis from a variety of perspectives. While the IJRF has typically had its major focus on persecution of Christians, this issue addresses many religious minorities. It is important to recognize that while diverse religions experience persecution, the experiences of persecution are similar.

We are pleased to welcome two guest editors for this issue. Adelaide Madera is a Full Professor at the Department of Law of the University of Messina, Italy, where she currently teaches Canon Law, Law and Religion, Comparative Religious Laws, and Religious Factor and Antidiscrimination Law. Since 2020, her research has focused on the impact of COVID-19 on religious freedom and the evolution of church-state relationships.

Kerstin Wonish was a PhD researcher in the field of religious minorities at the Institute for Minority Rights at EURAC Bolzano until 2022. With a background in law and religious studies she studied the accommodation of Islamic pluralism, religion and gender, and religion and human rights.

In addition to the thematic articles, I note a short “In my opinion” article by Kyle Wisdom about his project with the International Institute for Religious Freedom on “Good practices to reduce, resolve and prevent religious conflict”. The IIRF is looking for input so please consider participating in this project. As well, we have an interesting selection of book reviews.

We are also very pleased to have a new look for the journal. A hearty thank you to Ben Nimmo of Solid Ground for the new design.

Refugees and religious freedom Vol. 15 No. 1/2 (2022)

We are delighted to publish this special issue on Refugees and FoRB. It is a very timely issue in more ways than one. It is the first issue in several years that is being published in the year that it is dated. The 2019 issue, a special issue on the impact of religious freedom research, contained two articles on refugees and FoRB. We commend those articles by Kareem McDonald, a study on religious refugees in Dan-ish asylum centres, and me, examining the role of religious freedom research in the Canadian refugee determination system, to add to the fine collection in this issue.

We are very pleased to have Dr Marnix Visscher guest edit this issue. He has been working with the Dutch Gave Foundation since 2008. The Gave Foundation supports and trains churches and individual Christians for ministry among asylum seekers and refugees in the Netherlands. During Dr Visscher’s initial years with the foundation, Gave faced an increasing number of questions on issues of religious liberty regarding asylum seekers. The concerns included discrimination against and even harassment of religious minorities in the reception centres, along with how to assess asylum claims based on the fear of religious persecution. Dr Visscher took the initiative to form a judicial support team, campaigning for the rights of religious minorities in the reception centres and supporting asylum lawyers with expert reports based on the case files of individual asylum claims. Most of these reports assessed the credibility of the claimant’s conversion. The expert reports provided by Gave have had a significant impact on the outcome of asylum claims. Moreover, the work of Dr Visscher and his team has shaped important decisions on higher appeals, which in turn initiated further improvements in the decision process. Dr Visscher is also involved in the training of asylum lawyers and in consultations with the Dutch government.

Prof Dr Janet Epp Buckingham Executive editor

The 21 martyrs Vol. 14 No. 1/2 (2021)

This issue represents a number of significant changes for the International Journal for Religious Freedom. There have been some major changes in the leadership of the International Institute for Religious Freedom (IIRF), the research institute that publishes this journal. One of the founders of the IIRF was appointed the Secretary General of the World Evangelical Alliance. Dennis Petri has been appointed the new International Director of the IIRF and has ambitious plans to develop the institute. We have interviews with both Thomas Schirrmacher looking back on his years with the IIRF, and with Dennis Petri looking forward to a new vision for the institute. Also, after seven issues catching up with back issues, this issue represents the final “catch up” issue.

The theme of this issue “The 21 Martyrs” reflects the seriousness of the moment of 21 Coptic Christians being executed for their faith on a beach in Libya. The event was filmed and spread around the world. Two resources countering the ISIS narrative are addressed in this issue. In 2019, a book was published, which is reviewed by Paul Rowe. Second, Mark Rogers, a film producer, is working on an animated film to be released in 2023 on the 21 Martyrs. The cover photo is from the film. These resources paint a very different picture than the ISIS video and reveal 21 heroes of the faith who died on that beach.

The articles in this issue cover a broad diversity of geographical locations and perspectives on persecution. Two articles address theological issues. One addresses a methodological issue. Two articles focus on legal issues, one national and one international. One article focuses on describing the persecution of a religious minority. Another suggests that organized crime can be an engine of persecution. And finally, an article examines religious education. The articles address persecution in China, France, Myanmar and Mexico.

Responding to secularism Vol. 13 No. 1/2 (2020)

We are pleased to address in this issue the important issue of how secularism impacts religion and religious adherents. Secularism arose in the West, largely through the influence of European philosophers and sociologists. Christians in the West have in- creasingly been marginalized in secular states. But secular intolerance has spread to other countries as well. The articles in this issue represent a wide range of current and historical issues across several countries. We trust that you will find them interesting and informative. Please note that this issue is being published in early 2022.

The impact of religious freedom research Vol. 12 No. 1/2 (2019)

We are pleased that IJRF is continuing to catch up on its backlog. While this volume comes under the label of 2019, the articles were written in 2020 and 2021. The issue is being published at the end of 2021.

Our guest editors for this special issue are Dr Dennis P. Petri and Prof Dr Govert J. Buijs. Dr Petri has contributed articles to several previous issues of the IJRF. A political scientist, international consultant and researcher, Petri founded and serves as scholar-at-large of the Observatory of Religious Freedom in Latin America (OLIRE).

From marginalization to martyrdom Vol. 11 No. 1/2 (2018)

This issue covers a wide variety of topics from a truly global array of authors. Several authors show that Christians face marginalization, particularly in the West, for their faith. Christians can even be marginalized within their religious communities. But we are also aware that Christians face death for their faith and we honour those who have been martyred for their faith.

Responding to Persecution Vol. 10 No. 1/2 (2017)

This issue of IJRF deals with responses by those who are persecuted, as well as responses by those advocating on behalf of the persecuted.

Gender and Religious Freedom Vol. 9 No. 1/2 (2016)

Religious persecution is frequently gender-specific, impacting men and women dif-ferently. Grassroots research in countries such as Egypt and Pakistan in 2012 and 2013 showed that many women were experiencing double vulnerability not only due to their faith, but also as women. As a result, representatives of international charities who aid Christians facing persecution decided to form a steering group, bringing together non-governmental agencies, Christian ministries, and church leaders who were already seeking to address these issues. This issue presents some of the papers originally delivered in the scholarly tracks of several conferences, as well as other papers related to the issue of gender and persecution. Some of the papers are more recent than the 2016 date of this issue, which is being published in 2020 because the journal was dormant for several years.

Christian minorities & religious freedom Vol. 8 No. 1/2 (2015)

This issue represents the geographical and interdisciplinary breadth that the jour-nal strives for, with articles ranging from law to theology and from Nigeria to North America. While there was no preconceived thematic focus, the uniting thread of most of the contributions is a focus on Christian minorities and religious freedom.

Religious Extremism & Religious Tolerance Vol. 7 No. 1/2 (2014)

Religious extremism is considered as one of the major causes of contemporary reli-gious persecution, whereas religious tolerance is a foundation of religious freedom. This dual topic covers most of the articles in this issue and its terminology is inspired by the opinion piece of Thomas K. Johnson on “Religious extremism” and the report on the research project “Measuring religious tolerance ...” by Johannes van der Walt et al.

Researching Religious Freedom Vol. 6 No. 1/2 (2013)

There are several platforms and networks used by researchers interested in the study of religious freedom. Some of the contributions in this issue emanate from the In-ternational Consultation on Religious Freedom Research, held in Istanbul on 16-18 March 2013. They have all undergone the usual peer review process for IJRF – includ-ing the opinion pieces. They only represent a fraction of the many papers presented at the consultation. A separate consultation compendium is still being contemplated.The articles fall in roughly three groups: the opinion pieces, research that focuses on various regions and countries and an equal contingent of research on diverse topics relating to religious freedom and persecution.

Measuring and Encountering Persecution Vol. 5 No. 2 (2012)

Religious persecution is a phenomenon experienced by many adherents of various religions worldwide. In some contexts it is not outright persecution, but believers face serious challenges to the free exercise of religion. A common theme that unites most articles of this issue of IJRF is the encountering of persecution. What precisely are the challenges that believers, and particularly Christians, face in various con-texts? How do they cope with it? How do they react? Which role do theological inter-pretations play? Another question connected to the documentation of persecution is how it can be measured, and whether trans-national comparisons are possible.

Rising Restrictions Worldwide Vol. 5 No. 1 (2012)

Religious freedom has been thrust to the top of the political agenda in recent months. The violence in places like Nigeria has been on the front pages for some time, where sadly it continues (as Yakubu Joseph and Rainer Rothfuss describe in this issue in some detail). But in the industrial democracies – and now the United States in particular – religious freedom is becoming newsworthy as seldom be-fore. President Obama’s healthcare mandates have highlighted conflicts between religious freedom and personal behavior elsewhere in the developed world. We hope to explore this in a future issue, but it brings to a head trends that have been explored in this issue and other recent issues of IJRF.

Religion and Civil Society Vol. 4 No. 2 (2011)

“Civil society” is a concept that dates back to the late eighteenth century, as Silvio Ferrari points out in these pages, and it entered the vocabulary of political philoso-phy largely through Hegel and Marx. But it became newly fashionable following the collapse of communism in Central and Eastern Europe. It emphasizes the impor-tance to freedom of autonomous social groups and institutions below the state and not controlled by it. More recently, it has become controversial and the original meaning diluted by being adopted as the mantle for groups that are sometimes funded and supported by governments and international organizations. This is a significant potential pitfall when confronting problems of church and state. We approach civil society and the relations of church and state from several directions in this issue of the International Journal for Religious Freedom.

Advocacy and Law Vol. 4 No. 1 (2011)

This issue of IJRF focuses on “advocacy and law”, namely issues related to reli-gious freedom advocacy and legal matters surrounding religious freedom. Here is a stimulating general definition which applies well to social justice advocacy, includ-ing religious freedom advocacy on behalf of those persecuted for the sake of their religion and/or because of the religious motives of the persecutors: “Advocacy is speaking, acting, writing, with minimal conflict of interest on behalf of the sincerely perceived interests of a disadvantaged person or group to promote, protect and defend their welfare and justice by being on their side and no-one else’s; being primarily concerned with their fundamental needs; remaining loyal and accountable to them in a way which is emphatic and vigorous and which is, or is likely to be, costly to the advocate or advocacy group.” (Action for Advocacy Development).

Volume 3, Issue 2 Vol. 3 No. 2 (2010)

This issue of our journal strongly reflects the interdisciplinarynature of the IJRF, presenting original research in Islamic Studies,Geography, Law and Ethics, Government Science, and Theology.

Volume 3, Issue 1 Vol. 3 No. 1 (2010)

There are a number of global Christian mission conferences happeningin 2010. In addition, the discussion on how the propagation of one’sworld view and the issues of religious freedom, persecution and evenmartyrdom are related, has increased. Therefore we have chosen tofocus in this issue of the International Journal for Religious Freedomon “mission and persecution.”

Volume 2, Issue 2 Vol. 2 No. 2 (2009)

This issue of the International Journal for Religious Freedom wasborn in the tension between a lot of excitement and deep pain. That istrue both on a global as well as on a personal level. The editors, staff, associates of the International Institute for Religious Freedom, and theauthors of this IJRF issue have had many opportunities to contributeto the upholding of religious freedom, some of which are reflected inthis journal. However, researching and documenting the abuse ofhuman beings and the restriction or denial of their religious freedom,do not pass lightly. Some of us have seen moments of breakthroughand triumph as well as various degrees of personal suffering.

Volume 2, Issue 1 Vol. 2 No. 1 (2009)

It gives the editors of the International Journal for Religious Freedom (IJRF) great pleasure to present our readers with the second issue of thisinterdisciplinary and scholarly publication. We hope that you will find thearticles informative, thought-provoking, and of a high standard, and that thejournal will equally serve religious freedom. For that purpose we have addedsome new rubrics.

Volume 1 Vol. 1 No. 1 (2008)

Introducing the International Journal for Religious Freedom: The International Journal for Religious Freedom (IJRF) is dedicated tothe scholarly discourse on the issue of religious freedom in general andthe persecution of Christians in particular. It is an interdisciplinary,international, peer reviewed, scholarly journal, serving the practicalinterests of religious freedom and contains research articles,documentation, book reviews and academic news on the issue.

Information

- For Readers

- For Authors

- For Librarians

Current Issue

Announcements.

Articles on Religious freedom

Displaying 1 - 20 of 158 articles.

‘He just vanished’ − missing activists highlight Tajikistan’s disturbing use of enforced disappearances

Steve Swerdlow , USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

Religious diversity is exploding – here’s what a faith-positive Britain might actually look like

Christopher Wadibia , University of Oxford

Nicaragua released imprisoned priests, but repression is unlikely to relent – and the Catholic Church remains a target

Kai M. Thaler , University of California, Santa Barbara

Louisiana’s ‘In God We Trust’ law tests limits of religion in public schools

Frank S. Ravitch , Michigan State University

Supreme Court is increasingly putting Christians’ First Amendment rights ahead of others’ dignity and rights to equal protection

Pauline Jones , University of Michigan and Andrew Murphy , University of Michigan

French schools’ ban on abayas and headscarves is supposedly about secularism − but it sends a powerful message about who ‘belongs’ in French culture

Carol Ferrara , Emerson College

A constitutional revolution is underway at the Supreme Court, as the conservative supermajority rewrites basic understandings of the roots of US law

Morgan Marietta , University of Texas at Arlington

‘Uncivil obedience’ becomes an increasingly common form of protest in the US

Kristina M. Lee , University of South Dakota

Oklahoma OKs the nation’s first religious charter school – but litigation is likely to follow

Charles J. Russo , University of Dayton

When faith says to help migrants – and the law says don’t

Laura E. Alexander , University of Nebraska Omaha

Co-workers could bear costs of accommodating religious employees in the workplace, as Supreme Court reinterprets 46-year -old precedent

Debbie Kaminer , Baruch College, CUNY

French universalism sidelines ethnic minorities – why that must change

Philippe Marlière , UCL

Kenya cult deaths: a new era in the battle against religious extremism

Fathima Azmiya Badurdeen , Technical University of Mombasa

Are some human rights more important than others? Religious freedom advocates often put it first

Why London’s first Ramadan lights celebration has been so important for Muslims everywhere

Farouq Tahar , University of Sheffield

Plans for religious charter school, though rejected for now, are already pushing church-state debates into new territory

Millions of Americans at risk of losing free preventive care after Texas ruling on ACA

Paul Shafer , Boston University and Kristefer Stojanovski , Tulane University

How far must employers go to accommodate workers’ time off for worship? The Supreme Court will weigh in

Supreme Court signals sympathy with web designer opposed to same-sex marriage in free speech case

Mark Satta , Wayne State University

Religious freedom and LGBTQ rights are clashing in schools and on campuses – and courts are deciding

Related topics.

- Discrimination

- First Amendment

- Marriage equality

- Religion and law

- Religion and society

- Same-sex marriage

- US Supreme Court

Top contributors

Professorial Fellow, University of Canberra

Joseph Panzer Chair in Education and Research Professor of Law, University of Dayton

Dean of Economics, Politics & History, University of Texas at Arlington

Lecturer in Law, University of Tasmania

Senior Lecturer, The University of Western Australia

Associate Professor in Human Rights and International Law, University of Newcastle

Professor of Law, Director of the Center for Religion, Law & Democracy, Willamette University

Assistant Professor of Intellectual Heritage, Temple University

Professor of History, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Assistant Professor of Philosophy, Wayne State University

Lecturer, Faculty of Law, Monash University

Professor, Macquarie School of Social Sciences, Macquarie University

Emeritus Professor of Sociology, Monash University

Associate Professor of Sociology, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Associate Professor of Religious Studies, Texas State University

- X (Twitter)

- Unfollow topic Follow topic

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Public Health Rep

- v.130(5); Sep-Oct 2015

Respecting Religious Freedoms and Protecting the Public's Health

The history of public health law in the United States has always been about compromise. As noted recently by U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, the authority to protect and promote communal health is balanced with constitutional or other legal rights of individuals to act or behave as they wish provided they do not harm others. 1 In many cases, the scales are appropriately weighted to respect individual freedoms while advancing the public's health (e.g., public health surveillance activities). In other instances, furtherance of individual rights (e.g., to bear arms) can negatively impact health outcomes across populations.

For decades, Americans' religious freedoms under federal and state constitutions (and corresponding statutes and regulations) have been counterbalanced successfully with public health mandates. A prominent example entails the exemption of people from school vaccination requirements in 48 states based on religious freedoms undergirded, but not assured, by the First Amendment and encapsulated in statutory laws. While these exceptions have been challenged legally and politically, most recently following the 2015 measles outbreak, 2 widespread support for limited religious exceptions for vaccines remains. When used sparingly within communities, these vaccination exemptions may have minimal public health impacts.

The public health balancing act concerning religious freedoms, however, may be in the process of recalibration. Since the U.S. Supreme Court disallowed use of the controlled substance peyote as part of religious practices in 1990, 3 multiple versions of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) have been passed, first by Congress in 1993 4 and later by 22 states. Fierce debates regarding Indiana's 2015 passage of RFRA centered on potential private-sector sexual orientation discrimination led to an amendment clarifying that the act does not allow such discrimination. 5

The primary objective of RFRAs nationally—respecting individuals' religious beliefs—is laudable. These rights are among the first recognized by the Constitutional Framers and are essential to the fabric of the nation. 6 Yet, continued expansion of religious freedoms runs the risk of shifting trade-offs with essential governmental public health objectives. RFRA applications have the potential to adversely affect public health practices, programs, and objectives depending on ( 1 ) who qualifies as a “person” for the purposes of the Act, ( 2 ) what it means to exercise one's religion, ( 3 ) when and how government may “substantially burden” this exercise, and ( 4 ) whether or not government can demonstrate a compelling interest furthering public health objectives through least restrictive means. These issues appear to pertain not only to laws that are challenged, but also to legal modifications to accommodate religious beliefs.

EXPANSION OF RESPECT FOR RELIGIOUS FREEDOMS

Religious freedoms have long been entitled to respect via the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, similar state constitutional provisions, and civil rights laws and policies. However, federal and state passages of RFRAs expand the pool of people who are able to raise claims or seek defenses based on respect for religious freedoms. In 2014, the U.S. Supreme Court extended federal RFRA defenses to closely held, for-profit corporations in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc. 7 Despite vehement dissents among several Justices, the Court held that closely held, for-profit corporations can exercise the religious beliefs of individuals within the company. Indiana's definition of “person” in its version of RFRA specifically includes natural people, churches or other organizations that operate primarily for religious purposes, and anyone controlling or owning a partnership, corporation, company, society, or “any other entity” that “exercises practices that are compelled or limited by a system of religious belief.” 8 It seems a “person” in Indiana (and other jurisdictions) for purposes of RFRA is just about anyone or anything that claims to exercise religious beliefs.

Exercising one's religion includes any exercise “whether or not compelled by, or central to, a system or religious belief.” 9 This circular concept is exceptionally broad. Exercising religion pursuant to RFRA is literally whatever a religious person says it is. Direct infringements of one's exercise of religion via government are relatively easy for courts to identify. Local or state governments that restrict when, how, or where one can worship are open to RFRA challenges. In 2006, the U.S. Supreme Court relied on RFRA to invalidate a federal prohibition under the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) of the use of hoasca, a hallucinogen found in a sacramental tea used by a religious sect. As Chief Justice Roberts summarized, neither the government's interest in the “war on drugs” nor promotion of public health and safety is sufficient to support its prohibition via RFRA. 10 In another case in Texas in 2009, a federal appellate court dispensed with local ordinances prohibiting the keeping and slaughtering of animals for religious sacrifice on the basis that the ordinances infringed on exercises of religious beliefs in violation of RFRA. 11

Less direct infringements can be more difficult to discern under RFRA and similar First Amendment protections. Given the relative, definitional void of what it means to exercise one's religion, judges are deferential as to the source, nature, and sincerity of expressed religious beliefs. As one court described, “Courts are not permitted to ask whether a particular belief is appropriate or true—however unusual or unfamiliar the belief may be.” 12 In Hobby Lobby , the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Court were reticent to question the existence or sincerity of the plaintiff corporation's Christian beliefs against the use of specific contraceptives. 7 Doing so runs counter to the legislative intent underlying RFRA that the legitimacy or sincerity of one's religious beliefs is not subject to serious questioning.

DEMONSTRATING SUBSTANTIAL BURDENS

A primary finding of any successful RFRA claim or defense relates to whether or not government substantially burdens a person's exercise of religion. Neither the federal nor Indiana versions of RFRA statutorily define “substantial burden,” leaving the matter yet again for courts to decide. In a 1996 New York case, Jolly v. Coughlin , 12 a prisoner suspected of infection with active tuberculosis was quarantined when he refused to submit to testing. The appellate court agreed that quarantine substantially burdened the inmate's Rastafarian beliefs. In Hobby Lobby , the Supreme Court confirmed that economic costs incurred by a multistate corporation to pay for select reproductive products for its employees pursuant to the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act constituted a substantial impact on the company's Christian beliefs. 7

Nearly anytime a person can demonstrate a direct physical or economic impact from a governmental policy or program that contravenes the person's religious exercises, a substantial burden may be found pursuant to RFRA. Following Hobby Lobby , many nonprofit religious entities asserted that their beliefs were substantially burdened by the accommodation concerning the Affordable Care Act's contraceptive mandate proposed by the Supreme Court and HHS. 13 In Catholic Benefits Association LCA v. Burwell , 14 an Oklahoma district court held that the beliefs of certain Catholic Benefits Association members were substantially burdened by having to demonstrate that they qualify as an “eligible organization” to receive the accommodation. Other courts, however, have rejected similar arguments. 15 Still, in response, HHS issued an interim final rule allowing religious nonprofits to bypass the contested accommodation procedure and merely notify HHS of the organization's wishes to be accommodated. 16

In 2001, a federal court in Indiana delineated the meaning of “substantial burden” further as “one that forces adherents of a religion to refrain from religiously motivated conduct, inhibits or constrains conduct or expression that manifests a central tenet of a person's religious beliefs or compels conduct or expression that is contrary to those beliefs.” 17 Under these tests, even relatively minor infringements of an exercise of religion may be ripe for suit under RFRA. In 1995, Virginia-based abortion opponents challenged the constitutionality of the federal Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances (FACE) Act. 18 They posited that their religious opposition to abortion was curtailed by the act's limitations on their ability to physically obstruct access to clinics through peaceful picketing. A federal appellate court agreed that their religious interests were burdened. A year later, protesters argued that FACE burdened their religious mission of counseling women against abortion at Planned Parenthood clinics in Pennsylvania. 19 Such decisions reveal how even tangential impacts on one's exercise of religion may constitute substantial burdens for purposes of RFRA.

COMPELLING PUBLIC HEALTH INTERESTS

Of course, the mere fact that people's exercise of religion is substantially burdened does not mean they prevail under RFRA. Government can overcome a showing of substantial burden by demonstrating that its law, policy, or program furthers a compelling governmental interest, including protecting or promoting the public's health, by the least restrictive means to the expressed religious interests. This threshold built into Indiana's RFRA and similar acts provides a relative safe harbor for many public health programs and initiatives. Alleging that a specific public health program conflicts with or is contrary to one's religious beliefs is insufficient. Some people, for example, may not like how government expends revenues on public health programs to protect maternal and reproductive health, prevent obesity, curtail tobacco use, screen newborns, or control handguns. Government funding decisions alone do not constitute a RFRA violation so long as they do not impinge on constitutional principles of separation of church and state. RFRA claims or defenses are not the religious equivalent of a conscientious objector clause. 20

Broader-based respect for individuals' religious beliefs, however, can still impact public health objectives. In the Jolly case, the court released an inmate at risk of active tuberculosis from his “medical keeplock” because the department of corrections could not justify his continued confinement as serving a compelling interest through the least restrictive means. 12 Expanding the array of objections to school vaccination requirements based on loosely held religious beliefs pursuant to RFRA may further erode herd immunity, leading to increased outbreaks of measles, whooping cough, and other childhood diseases. Enforcement of local licensing or permitting requirements may be questioned to the extent that a business owner's religious principles are implicated. Multiple states, buttressed by court decisions, specifically exempt churches and other religious entities from regulations affecting private-sector child care facilities. 6 In April 2015, a food truck owner in San Antonio, Texas, claimed that local police infringed on her religious freedoms when she was fined for feeding the homeless in a public park without a permit. 21 Law Professor Doug Laycock points to another case in 2013 that struck down a Dallas, Texas, ordinance limiting where charities could feed the homeless based on RFRA despite strong public health and safety concerns underlying the ordinance. 22

Consider the proposed scenario 22 surrounding Indiana's declaration of a public health emergency on March 26, 2015, in response to a localized human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) outbreak. 23 More than 150 individuals in a rural county have been infected with HIV largely through intravenous drug users addicted to a prescription opioid. 24 Governor Mike Pence's declaration allows for the temporary waiver of drug paraphernalia laws to implement a needle exchange program (NEP). 25 These programs are banned federally, 25 in Indiana, and in multiple other states based on ( 1 ) the largely discredited belief that distributing free hypodermic needles furthers illicit drug habits and ( 2 ) prior religious or moral objections to distributing needles to sinful, law-breaking injection drug users and their HIV-infected partners. These discredited opinions largely dissipated as NEPs proved efficacious in preventing new cases of HIV. 26

While multiple religious groups now endorse or directly operate these exchanges locally, could a local church whose congregation works to help injection drug users through its addiction center use RFRA to legally contest NEPs in its community? Governor Pence could simply waive this application of RFRA for the duration of the emergency, but this action may be politically unpopular given his strong support for the law. 27 Even if a case proceeded, government can surely argue that operating a NEP in a public health emergency advances a compelling governmental interest. Yet, the New York State Department of Corrections could not support its compelling interest in quarantining prisoners at risk for tuberculosis in Jolly . 12 Furthermore, whether or not operation of a NEP represents the least restrictive means is debatable to the extent that NEPs have been off limits for three decades in Indiana due in part to initial religious objections.

Challenging government's public health efforts to implement isolation and quarantine measures, exchange needles, or require vaccinations as a condition of school attendance based on limited religious objections may seem far-fetched. Yet, RFRA has already been used as both a sword and a shield to thwart or derail existing public health practices and laws. Additional RFRA actions may not contribute significantly to what one legal commentator identified as a trend toward “religious affirmative action program[s].” 6 However, they have the potential to skew the balance of individual and communal rights toward stronger respect for corporate or other religious beliefs in the larger economic marketplace, and away from protection and promotion of the public's health.

Any views or opinions expressed in this article are those of the author. The author acknowledges Gregory Measer, JD, Asha Agrawal, and Matthew Saria at Arizona State University for their research assistance.

The Fight for Religious Freedom Isn’t What It Used to Be

The way the cause is now deployed drives a perception that conservative Christians, who are tightly linked to Republican politics, will be the beneficiaries of its expansion.

In the legal battle between religious rights and gay rights, religious freedom gained a victory today. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously that the First Amendment’s religious-freedom protections prevent the city of Philadelphia from refusing to contract with a Catholic foster-care agency that, based on its religious beliefs, does not place foster children with same-sex couples. The decision, Fulton v. City of Philadelphia , is a victory for conservative Christians who have been arguing that the Constitution’s guarantees of religious freedom protect religious organizations and individuals who wish to deny certain services to LGBTQ people.

The Fulton decision is substantial, but it is not the blockbuster outcome that some had expected. In a narrow ruling, the Court determined that Philadelphia’s policies were not neutral toward religion and thus violated the First Amendment’s free-exercise clause. Fulton is in line with the Court’s shift toward a broader interpretation of First Amendment protections, but the Court was divided about the bigger question, specifically whether to expand religious-liberty rights by replacing a 1990 legal precedent, Employment Division v. Smith .

The Smith decision was written by Antonin Scalia, the late conservative justice, and it limited the rights of a religious minority—Native Americans—stating that free-exercise rights could not exempt them from “neutral laws” (in this case drug laws) that did not target their religion. Smith ’s circumscribed view of religious liberty has been the prevailing legal precedent ever since, but it has become controversial, especially among conservatives. Although the Court did not overturn Smith today, several justices signaled a willingness to do so. Justice Samuel Alito wrote a lengthy concurring opinion arguing that Smith should be “reexamined.” In her opinion, Justice Amy Coney Barrett wrote that the arguments against Smith are “compelling,” but that Fulton did not require the Court to abandon it.

Thirty years ago, a potential reversal of Smith would have been celebrated, especially by liberals. Today, conservatives are leading the charge to expand religious freedom and overturn Smith . Understanding why reveals the contours of a major transformation that American society has undergone over the past three decades.

Zalman Rothschild: ‘Religious equality’ is transforming American law

Two conversations about religious freedom are happening simultaneously, one legal and one political. The majority opinion in Fulton , written by Chief Justice John Roberts, emphasized the legal conversation, detailing how Philadelphia was not neutral toward religion. Alito’s concurring opinion, calling for the replacement of Smith , similarly emphasized the legal conversation. He argued that repealing Smith would protect religious freedom for everyone, including Orthodox Jews, Sikh men, and Muslim women. Such an approach is common among religious-freedom advocates, but it misses the political context that has developed alongside expansive religious-freedom claims. In politics, the way the religious-freedom cause is deployed drives a perception that conservative Christians, who are tightly linked to Republican politics, will be the beneficiaries of its expansion. This promotes division.

Not long ago, religious freedom used to cut across groups and cross partisan lines. The religious divide between the parties was less stark—evangelical Democrats such as Jimmy Carter were common—and liberal advocacy groups such as the ACLU defended the free exercise of religion before courts. Religious minorities, such as the Amish, Seventh Day Adventists, and Jehovah’s Witnesses, were frequent beneficiaries. After the Supreme Court limited religious-freedom rights with the Smith decision, opposition was nearly universal—and certainly bipartisan—though led by Democrats and progressive groups. Congress passed the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) of 1993 nearly unanimously to weaken Smith and restore broad religious-liberty protections. Bipartisan supermajorities in several states followed suit by enhancing their religious-freedom protections.

Within a decade, these bipartisan currents were changing. Republicans leveraged religious-liberty arguments to advance their position on cultural issues. They argued that Christians’ religious freedom was under threat, and emphasized cultural conflict. In doing so, Republicans adopted the cultural arguments for religious freedom that were championed by white evangelicals. Evangelicals had become a core part of the party’s activist base and electoral coalition, mobilized by a mixture of opposition to civil rights and abortion rights, as well as support for religious nationalism. Evangelicals had been emphasizing religious-freedom arguments for decades to push back against secularism and the sexual revolution, and to promote cultural conservatism, such as prayer in schools. When conservative Christians became integrated into the Republican Party, their religious-freedom messages gained broader appeal.

As conservative Christians were losing cultural and political ground, particularly in the area of gay rights, they turned to constitutional rights to advance their claims, making these appeals to courts and in public life. In the years following Smith and the RFRA legislation, advocates leaned on religious liberty to oppose nondiscrimination policies that protected the civil rights of gays and lesbians. Conservative Christian groups sought to weaken, if not overturn, Smith in order to maximize religious-liberty protections for private Christian actors who might run afoul of generally applicable laws.

Civil-rights groups objected and mobilized the broader Democratic coalition, and religious freedom became a culture-wars flashpoint. The ACLU opposed religious liberty being used to deny gays and lesbians access to housing. LGBTQ groups, after being silent about religious freedom for most of the 1990s, started warning that religious-liberty claims could be used to discriminate. As the conflict expanded and consolidated around the two poles of party politics, support for religious freedom on the left dwindled. Democrats and their allied groups withdrew their sponsorship of a sweeping religious-freedom bill in 1999, and hopes for a continued bipartisan religious-freedom coalition were dashed.

Netta Barak-Corren: How one Supreme Court decision increased discrimination against LGBTQ couples

Over the next two decades, Republicans mobilized around religious freedom, particularly emphasizing the threats to conservative Christians. Republicans sponsored legislation in Congress and in state Houses, championed executive activity defending religious rights, and urged the Court to expand First Amendment protections. In 2014, the U.S. Supreme Court’s Hobby Lobby decision sided with conservative Christians and used the bipartisan RFRA legislation to limit a key piece of the Affordable Care Act—the contraception mandate. When the Court legalized same-sex marriage, in 2015’s Obergefell v. Hodges, dissenters and conservative advocates warned about the decision’s impact on religious believers. Conservative Christians, once the junior partner in the conservative legal movement and the Republican Party, made religious freedom a central cause of the party’s cultural agenda.

Democrats resisted this mobilization. Throughout the 2000s, Democratic sponsorship of religious-freedom legislation diminished. In 2014, religious-freedom bills in five states garnered only four votes from Democrats. The ACLU, once a proud supporter of RFRA, announced that it could no longer back the legislation, and actively campaigned to modify it to prevent discrimination. The Equality Act, which has become a priority of the current Democratic Congress, would do just that. As Republicans rallied around religious freedom for Christians, Democrats changed their outlook as well.

As religious freedom has become polarized, surveys frequently show partisan divides over related policies. My research suggests that the divide is not merely about the actual details of any one policy, but about who is perceived to benefit.

In a survey conducted in October, I showed people a general statement supporting religious freedom, but randomized whether the statement was attributed to Joe Biden or Donald Trump. When it was attached to Trump, respondents’ support declined more than when it was said to come from Biden, and the responses were especially polarizing across party lines. If people believed that the statement was Trump’s, they were also more likely to assume that white Christians would benefit from the religious freedom in question.

Similarly, people seem to alter their opinions when religious freedom is linked to non-Christian groups. In other surveys I conducted, when people were exposed to non-Christian groups advocating for religious freedom—such as Muslim truck drivers arguing for a religious accommodation not to deliver alcohol—polarization of the issue decreases. The perception of who benefits from religious freedom matters for political support.

The Fulton decision, while securing a win for religious-liberty advocates, left open the potential to reverse the Smith precedent. A reversal of Smith has roots in historically bipartisan efforts to defend the rights of religious minorities, and many such groups would benefit from it. In the three decades since Smith , however, conservative Christians have mobilized the Republican Party to promote their religious-freedom interests while often refusing to grant religious-liberty rights to minorities, such as Muslims. Although these Christians have succeeded in getting the Supreme Court to grant them their religious-freedom rights, as with today’s Fulton decision, fusing religious freedom to their interest alone has come at the cost of bipartisan support. These alliances are not easily unwound.

Ultimately, politicizing religious freedom will hurt true civil-liberties claims. Conservative Christians are correct that religious freedom is under threat, but the threat comes as much from partisan politics as it does from legal precedents.

Global religious restrictions rise, social harassment falls

Doidam 10 | Shutterstock

Please consider a gift for Aleteia! Help us spread the joy of Christ's victory. Aleteia depends on your support.

Join our Lenten Campaign 2024.

A March report from Pew Research Center is casting light on the rate of government and social hostilities toward religion worldwide. The data, drawn during 2021, found growth in government restrictions on religion, while social hostilities were seen to drop.

The metrics

The report measured government restriction and social hostilities toward religion in two 10-point indexes, the Government Restrictions Index (GRI) and the Social Hostilities Index (SHI) . Pew explains that the GRI examines laws, policies, and government action that regulate or limit religious belief or practices. This includes governments that extend benefits to some religious groups and not others, as well as those that require religious groups to register to receive some form of benefit.

The SHI, on the other hand, measures hostile actions from individuals or groups that target religious groups, as well as those who use religion to restrict others. Examples of incidents that would be recorded by the SHI include religion-related harassment, mob violence, terrorism/militant activity, and hostilities over religious conversions or the wearing of religious symbols and clothing.

Government restrictions

Although the GRI recorded an increase of just .2, the median level of government restriction on religion was found to be the highest recorded since Pew began tracking religious restrictions in 2007. While the recorded rate of 3.0 is low on a scale with 10 being the highest, it should be noted that this is the median global rate, meaning some nations are more restrictive than 3.0, and some are less.

In total, 55 of 198 (28%) global countries and territories were rated at “high” or “very high” levels of governmental religious restrictions . Interestingly, the number of highly restrictive nations has fallen from 57 in 2020, but the global rate of government restrictions rose due to more nations increasing in score rather than decreasing, even if these nations did not reach “high” or “very high” levels.

Furthermore, it was found that religious groups reported government harassment in 183 countries in 2021. This is the highest rate recorded for this study as well. Governments reportedly interfered in worship in 163 countries in 2021, which is only down 1 point since 2020.

Social harassment

The increases in government restrictions were mirrored in the opposite by the rates of social harassment of religions. In 2021, the SHI dropped from 1.8 in 2020 to 1.6. While social harassment was identified in 164 countries – the same as in 2020 – only 43 (22%) of them were found to have reached “high” or “very high” levels.

While the global rate of social religious harassment has risen from 40 in 2020, it is closer to the all-time low of 18% than it is to the all-time high of 33% . Additionally, physical harassment at the social level was seen to decline from 105 in 2020 to 101 in 2021. Pew writes of physical harassment:

“Property damage was the most common type of physical harassment reported against religious groups (in 105 countries, or 53%). Physical assaults were reported in 91 countries (46%), while detentions occurred in 77 countries (39%). Meanwhile, there were religion-related displacements in 38 countries (19%), and killings were reported in 45 countries (23%).”

See the full report at Pew Research Center.

Articles like these are sponsored free for every Catholic through the support of generous readers just like you.

Help us continue to bring the Gospel to people everywhere through uplifting Catholic news, stories, spirituality, and more.

Read our research on: Abortion | Podcasts | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

8 in 10 americans say religion is losing influence in public life, few see biden or trump as especially religious.

Pew Research Center conducted this survey to explore Americans’ attitudes about religion’s role in public life, including politics in a presidential election year.

For this report, we surveyed 12,693 respondents from Feb. 13 to 25, 2024. Most of the respondents (10,642) are members of the American Trends Panel, an online survey panel recruited through national random sampling of residential addresses, which gives nearly all U.S. adults a chance of selection.

The remaining respondents (2,051) are members of three other panels, the Ipsos KnowledgePanel, the NORC Amerispeak panel and the SSRS opinion panel. All three are national survey panels recruited through random sampling (not “opt-in” polls). We used these additional panels to ensure that the survey would have enough Jewish and Muslim respondents to be able to report on their views.

The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education, religious affiliation and other categories.

For more, refer to the ATP’s Methodology and the Methodology for this report. Read the questions used in this report .

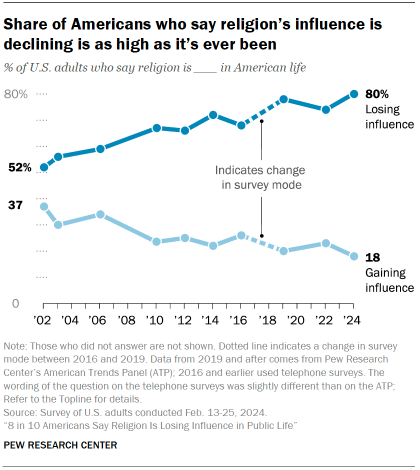

A new Pew Research Center survey finds that 80% of U.S. adults say religion’s role in American life is shrinking – a percentage that’s as high as it’s ever been in our surveys.

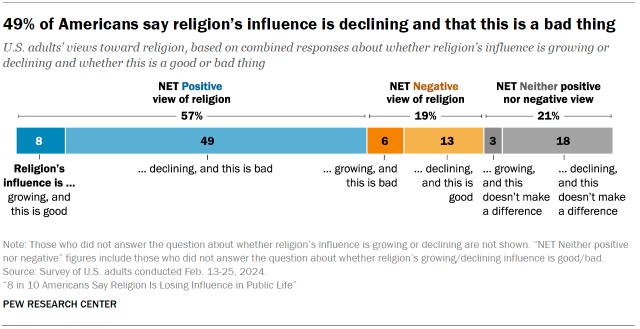

Most Americans who say religion’s influence is shrinking are not happy about it. Overall, 49% of U.S. adults say both that religion is losing influence and that this is a bad thing. An additional 8% of U.S. adults think religion’s influence is growing and that this is a good thing.

Together, a combined 57% of U.S adults – a clear majority – express a positive view of religion’s influence on American life.

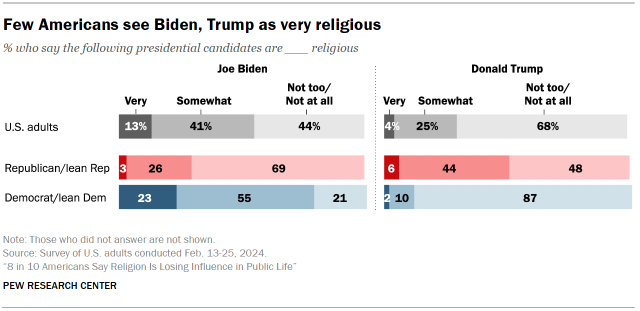

The survey also finds that about half of U.S. adults say it’s “very” or “somewhat” important to them to have a president who has strong religious beliefs, even if those beliefs are different from their own. But relatively few Americans view either of the leading presidential candidates as very religious: 13% of Americans say they think President Joe Biden is very religious, and just 4% say this about former President Donald Trump.

Overall, there are widespread signs of unease with religion’s trajectory in American life. This dissatisfaction is not just among religious Americans. Rather, many religious and nonreligious Americans say they feel that their religious beliefs put them at odds with mainstream culture, with the people around them and with the other side of the political spectrum. For example:

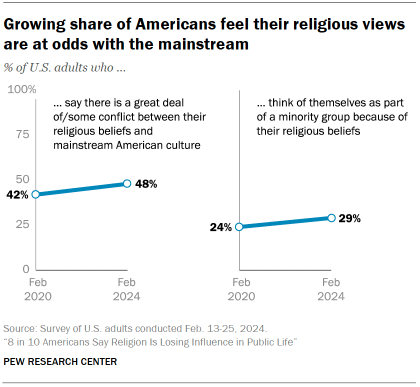

- 48% of U.S. adults say there’s “a great deal” of or “some” conflict between their religious beliefs and mainstream American culture, up from 42% in 2020.

- 29% say they think of themselves as religious minorities, up from 24% in 2020.

- 41% say it’s best to avoid discussing religion at all if someone disagrees with you, up from 33% in 2019.

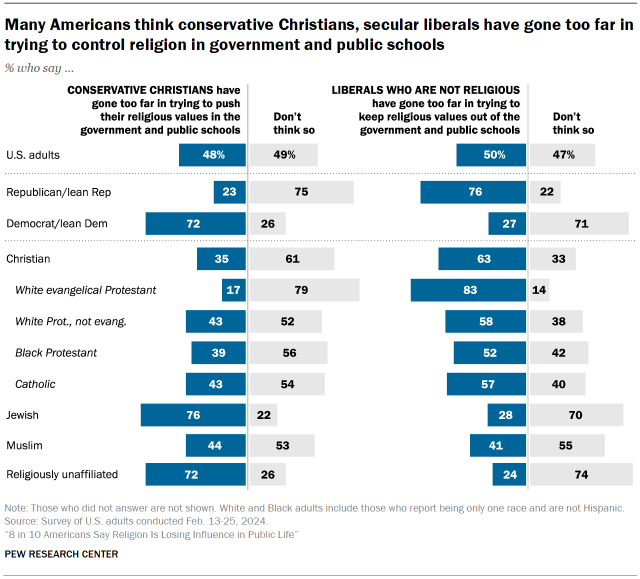

- 72% of religiously unaffiliated adults – those who identify, religiously, as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular” – say conservative Christians have gone too far in trying to control religion in the government and public schools; 63% of Christians say the same about secular liberals.

These are among the key findings of a new Pew Research Center survey, conducted Feb. 13-25, 2024, among a nationally representative sample of 12,693 U.S. adults.

This report examines:

- Religion’s role in public life

- U.S. presidential candidates and their religious engagement

- Christianity’s place in politics, and “Christian nationalism”

The survey also finds wide partisan gaps on questions about the proper role for religion in society, with Republicans more likely than Democrats to favor religious influence in governance and public life. For instance:

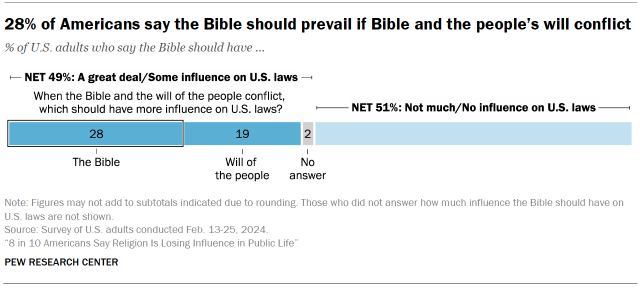

- 42% of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents say that when the Bible and the will of the people conflict, the Bible should have more influence on U.S. laws than the will of the people. Just 16% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents say this.

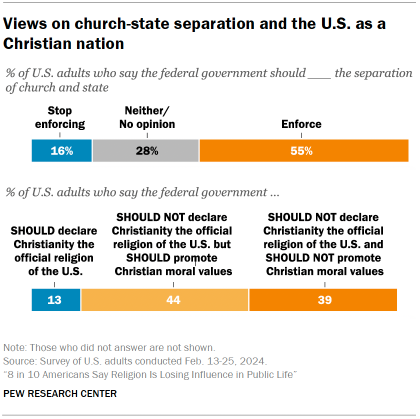

- 21% of Republicans and GOP leaners say the federal government should declare Christianity the official religion of the United States, compared with 7% of Democrats and Democratic leaners.

Moral and religious qualities in a president

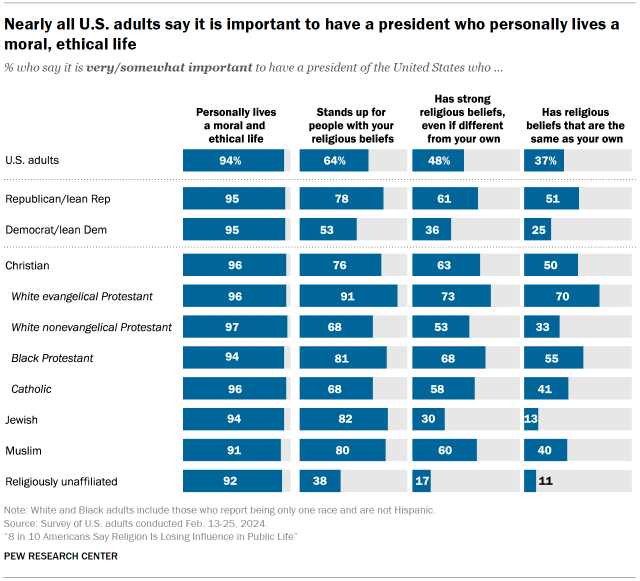

Almost all Americans (94%) say it is “very” or “somewhat” important to have a president who personally lives a moral and ethical life. And a majority (64%) say it’s important to have a president who stands up for people with their religious beliefs.

About half of U.S. adults (48%) say it is important for the president to hold strong religious beliefs. Fewer (37%) say it’s important for the president to have the same religious beliefs as their own.

Republicans are much more likely than Democrats to value religious qualities in a president, and Christians are more likely than the religiously unaffiliated to do so. For example:

- Republicans and GOP leaners are twice as likely as Democrats and Democratic leaners to say it is important to have a president who has the same religious beliefs they do (51% vs. 25%).

- 70% of White evangelical Protestants say it is important to have a president who shares their religious beliefs. Just 11% of religiously unaffiliated Americans say this.

Views of Biden, Trump and their religious engagement

Relatively few Americans think of Biden or Trump as “very” religious. Indeed, even most Republicans don’t think Trump is very religious, and even most Democrats don’t think Biden is very religious.

- 6% of Republicans and GOP leaners say Trump is very religious, while 44% say he is “somewhat” religious. Nearly half (48%) say he is “not too” or “not at all” religious.

- 23% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents say Biden is very religious, while 55% say he is somewhat religious. And 21% say he is not too or not at all religious.

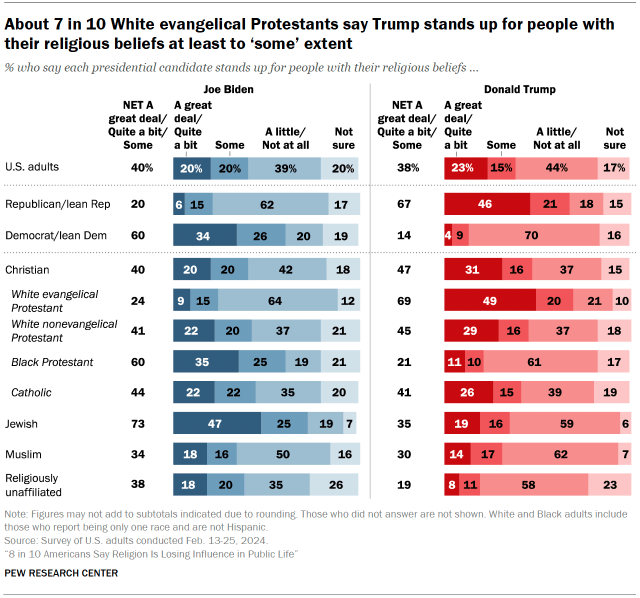

Though they don’t think Trump is very religious himself, most Republicans and people in religious groups that tend to favor the Republican Party do think he stands up at least to some extent for people with their religious beliefs. Two-thirds of Republicans and independents who lean toward the GOP (67%) say Trump stands up for people with their religious beliefs “a great deal,” “quite a bit” or “some.” About the same share of White evangelical Protestants (69%) say this about Trump.

Similarly, 60% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents, as well as 73% of Jewish Americans and 60% of Black Protestants, say Biden stands up for people with their religious beliefs a great deal, quite a bit or some.

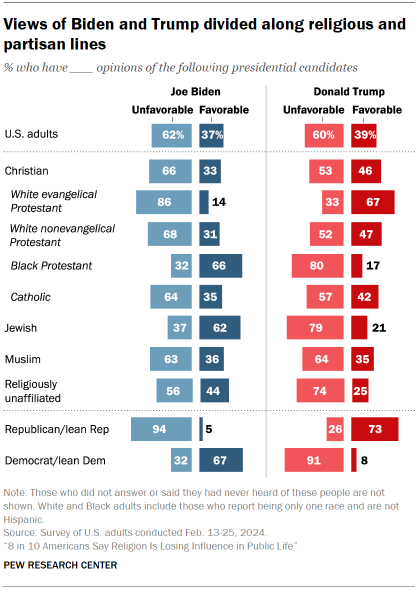

Overall, views of both Trump and Biden are generally unfavorable.

- White evangelical Protestants – a largely Republican group – stand out as having particularly favorable views of Trump (67%) and unfavorable views of Biden (86%).

- Black Protestants and Jewish Americans – largely Democratic groups – stand out for having favorable views of Biden and unfavorable views of Trump.

Views on trying to control religious values in the government and schools

Americans are almost equally split on whether conservative Christians have gone too far in trying to push their religious values in the government and public schools, as well as on whether secular liberals have gone too far in trying to keep religious values out of these institutions.

Most religiously unaffiliated Americans (72%) and Democrats (72%) say conservative Christians have gone too far. And most Christians (63%) and Republicans (76%) say secular liberals have gone too far.

Christianity’s place in politics, and Christian nationalism

In recent years, “Christian nationalism” has received a great deal of attention as an ideology that some critics have said could threaten American democracy .

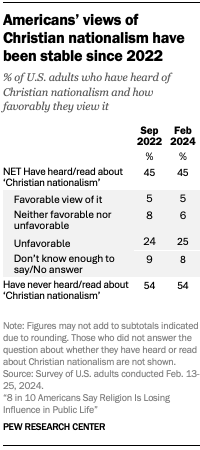

Despite growing news coverage of Christian nationalism – including reports of political leaders who seem to endorse the concept – the new survey shows that there has been no change in the share of Americans who have heard of Christian nationalism over the past year and a half. Similarly, the new survey finds no change in how favorably U.S. adults view Christian nationalism.

Overall, 45% say they have heard or read about Christian nationalism, including 25% who also have an unfavorable view of it and 5% who have a favorable view of it. Meanwhile, 54% of Americans say they haven’t heard of Christian nationalism at all.

One element often associated with Christian nationalism is the idea that church and state should not be separated, despite the Establishment Clause in the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

The survey finds that about half of Americans (49%) say the Bible should have “a great deal” of or “some” influence on U.S. laws, while another half (51%) say it should have “not much” or “no influence.” And 28% of U.S. adults say the Bible should have more influence than the will of the people if the two conflict. These numbers have remained virtually unchanged over the past four years.

In the new survey, 16% of U.S. adults say the government should stop enforcing the separation of church and state. This is little changed since 2021.

In response to a separate question, 13% of U.S. adults say the federal government should declare Christianity the official religion of the U.S., and 44% say the government should not declare the country a Christian nation but should promote Christian moral values. Meanwhile, 39% say the government should not elevate Christianity in either way. 1

Overall, 3% of U.S. adults say the Bible should have more influence on U.S. laws than the will of the people; and that the government should stop enforcing separation of church and state; and that Christianity should be declared the country’s official religion. And 13% of U.S. adults endorse two of these three statements. Roughly one-fifth of the public (22%) expresses one of these three views that are often associated with Christian nationalism. The majority (62%) expresses none.

Guide to this report

The remainder of this report describes these findings in additional detail. Chapter 1 focuses on the public’s perceptions of religion’s role in public life. Chapter 2 examines views of presidential candidates and their religious engagement. And Chapter 3 focuses on Christian nationalism and views of the U.S. as a Christian nation.

- The share saying that the government should declare Christianity the official national religion (13%) is almost identical to the share who said the government should declare the U.S. a Christian nation in a March 2021 survey that asked a similar question (15%). ↩

Sign up for our Religion newsletter

Sent weekly on Wednesday

Report Materials

Table of contents, 5 facts about religion and americans’ views of donald trump, u.s. christians more likely than ‘nones’ to say situation at the border is a crisis, from businesses and banks to colleges and churches: americans’ views of u.s. institutions, most u.s. parents pass along their religion and politics to their children, growing share of americans see the supreme court as ‘friendly’ toward religion, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

- Leadership Crisis

- Editor's Pick

Colleagues Rally to Harvard Sociology Prof.’s Defense Following Plagiarism Allegations

Harvard Says It Wants to Boost Interdisciplinary Research. Its Professors Have Questions.

Harvard to Bring Back Introductory History Course for Fall Semester

Cambridge Teachers, Students Call for End to MCAS Graduation Requirement

Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor Named 2024 Radcliffe Medal Recipient

Harvard, Academic Freedom, and the New Wars of Religion

Council on academic freedom at harvard.

For evidence that intolerance is a problem at Harvard, one need only look at the cases from 2021 involving evolutionary biologist Carole K. Hooven and biostatistician Tyler J. VanderWeele .

Carole claimed that sex (not gender) was binary, the standard position in evolutionary biology. For this she was publicly denounced by the graduate student director of her department’s DEI task force and said she was unable to teach her lecture class as no graduate students were willing to serve as her teaching fellow. The fallout, coupled with the lack of support from her department, led to her eventual resignation.

Tyler, a practicing Catholic, signed an amicus brief opposing a federal, constitutional right to gay marriage in favor of state-by-state resolution. In response to the brief, and past writings of his on abortion, graduate students in public health insisted he be fired or, at minimum, barred from teaching. (He continues to teach at Harvard.)

In part because of these two cases, there have been demands by faculty that the University better protect academic freedom and that the broader Harvard community better ensure civil, reasoned discourse. (For an important statement on inclusion and academic freedom, see Harvard’s 2018 Presidential Task Force Report on Inclusion and Belonging.)

I fully support such calls. I doubt, however, that they will change the behaviors of those who are genuinely convinced about the erroneousness of others’ beliefs and the validity of their own. I will make a different argument: that for academic freedom to prevail, all at Harvard must tolerate others and their beliefs.

Religious and more generally ideological wars are often disastrous. In such conflicts, people are branded as heretics for their beliefs and excluded; they are attacked even though they are members of one’s own community; many people are harmed if not killed; if one side succeeds, it leads to the oppression of others.

In “Politics as Religion,” the renowned Italian scholar Emilio Gentile argues that in recent centuries, particularly in the West, politics has taken on the form of a religion, “claiming as its own the prerogative of defining the fundamental purpose and meaning of human life.” His particular concern is with fascism and communism as forms of totalitarianism that are analogous to those of fundamentalist religion with its total faith in its beliefs and practices. Too often, the horrifying consequence of such total self-surety is the demonization of nonbelievers and the adoption of “coercive measures that range from banishment from public life to [...] physical annihilation.”

The consequences of fascism and communism are — or at least should be — well known. But there is more to consider. For most of the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, Europe was engaged in a series of devastating religious wars. The Thirty Years’ War, for example, is estimated to have resulted in the death of a third of Germany’s population. Today, we witness the carnage in Palestine and Israel, the result of a conflict that goes back more than a century, now fueled by the religious zealotry of Israel’s right and Hamas, both of which are certain that God has promised them the totality of the region’s territory

Recent political strife in the United States has also led to people being killed, as in Charlottesville, V.A. Fortunately, recent campus protests have not resulted in any deaths, but life, particularly for Muslims and Jews, too often consists of repeated harassment, intimidation, and exclusion.

The United States was founded upon the principle that individuals should be allowed to practice their religion free from persecution. Although the U.S.’s historical record on this front is certainly mixed and there is still much to be done, significant progress has occurred, allowing for the coexistence of a diversity of beliefs and practices.

It is ironic then, that today, across the country and on so many college campuses, we are seeing such fierce ideological wars analogous in character to religious conflict, sporting dug-in camps that make broad and increasingly dogmatic claims.

Currently, as in the past, there are strong pleas for Harvard to publicly take political positions. At times, it has, including in response to the murder of George Floyd and the war in Ukraine. Countering these calls, there has been recent debate about whether Harvard should remain neutral on political matters unless the issues involved threaten the very mission of the University. In the present context, this debate is arguably analogous as to those about whether a nation should have a state religion.

My plea in these contentious times is that we at least tolerate each other — that we resist the urge to deplatform, attack, punish, and censor — even if we can’t find it within ourselves to listen to those we deeply disagree with, much less understand and respect their views.

As Bertrand Russel argues: “In this world, which is getting more and more closely interconnected, we have to learn to tolerate each other, we have to learn to put up with the fact that some people say things that we don’t like. We can only live together in that way. But if we are to live together, and not die together, we must learn a kind of charity and a kind of tolerance, which is absolutely vital to the continuation of human life on this planet.”

Toleration of others avoids and ends wars of religion. It would be ideal if we were able to listen to and respect others even when we believe their views are objectionable and fundamentally wrong. But if we want to avoid the current situation becoming even more like a religious war, tolerance is a needed first step.

Christopher Winship is the Diker-Tishman Professor of Sociology.

His piece is part of the Council on Academic Freedom at Harvard’s column , which runs bi-weekly on Mondays and pairs faculty members to write contrasting perspectives on a single theme. Read the companion to Winship’s piece here.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.

COMMENTS

Abstract. Résumé. Religious freedom (RF) is important because it is posited to be a central element of liberal democracy and as having multiple additional benefits including increased security and economic prosperity. Yet, it is also a disputed concept and many liberal democracies restrict the freedoms of religious minorities.

Olga Breskaya, PhD is a senior researcher at the Department of Philosophy, Sociology, Education, and Applied Psychology at University of Padova.Her research focuses on the sociology of human rights and comparative study of religious freedom. She recently co-edited a volume of the Annual Review of the Sociology of Religion Religious Freedom: Social-Scientific Approaches (2021) and co-authored ...

In 2021, government restrictions on religion - laws, policies and actions by state officials that limit religious beliefs and practices - reached a new peak globally. Harassment of religious groups and interference in worship were two of the most common forms of government restrictions worldwide that year. feature | Mar 5, 2024.

This dualist protection of religious interests, complicated by the presence of an anti-discrimination article in the ECHR 7 and a commitment to protecting freedom of religion under article 10 of the CFR, has led to debates concerning the interactions between religious freedom and religious discrimination. Authors have thus discussed which of the ECHR or the Directive is the more effective ...

Here are the key findings: Government restrictions on religion reached a new high in 2021. Globally, the median score on our 10-point Government Restrictions Index rose from 2.8 in 2020 to 3.0 in 2021 - the highest level recorded since we began tracking this in 2007. The index tracks 20 measures on government laws, policies and actions that ...

In 2021, government restrictions on religion - laws, policies and actions by state officials that limit religious beliefs and practices - reached a new peak globally. Harassment of religious groups and interference in worship were two of the most common forms of government restrictions worldwide that year. feature | Mar 5, 2024.

The right to freedom of religion or belief is an integral part of the international human rights framework and, as such, has been criticized alongside human rights in general. ... Bielefeldt's research interests, above all, include different interdisciplinary facets of human rights theory and practice. He served as the United Nations Special ...

In that meeting, 30 parliamentarians from 17 countries signed the Oslo Charter for Freedom of Religion or Belief, the founding document of IPPFoRB. The Canadian government, via its Canadian Office for Religious Freedom, further established an International Contact Group on Freedom of Religion or Belief (ICG) in 2015.

This article offers an overview of the most common misconceptions about religious freedom, with reference to the 2017 UN Report by Mr. Shaheed and the perspectives of other human rights scholars and experts. It proceeds with the operationalization of a selected list of misconceptions about this subject for empirical research of religious freedom awareness.

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. ... Underscoring the external and public dimensions of institutional religious freedom, the article follows the work of law and religion scholar W. Cole Durham in that it analytically disaggregates the freedom of religious institutions ...

This article provides a legal analysis of the policies meant to curb the COVID-19 pandemic with a focus on legislative and judiciary actions and their implications for religious freedom. Ultimately, we hope this article will help inform future legal analyses on conflicts between public health and religious freedom in the context of pandemic ...

The 2019 issue, a special issue on the impact of religious freedom research, contained two articles on refugees and FoRB. We commend those articles by Kareem McDonald, a study on religious refugees in Dan-ish asylum centres, and me, examining the role of religious freedom research in the Canadian refugee determination system, to add to the fine ...

The chapter on religion. The chapter - entitled 'Religions and Social Progress: Critical Assessments and Creative Partnerships' - starts from the fact that more than eight-in-ten of the world's population affirms some kind of religious identification, a proportion that is growing rather than declining, pointing the reader to the statistics compiled by the Pew Forum and freely ...

Articles on Religious freedom. Displaying 1 - 20 of 158 articles. ... Joseph Panzer Chair in Education and Research Professor of Law, University of Dayton Morgan Marietta

View PDF. The relationship between culture and freedom of religion or belief (FoRB) is often seen as a negative one, with freedom of religion often invoked to defend human rights violations. In response, many human rights advocates draw a distinction between culture and religion, and what is insinuated is that culture is the problem, not religion.

And social hostilities involving religion - including violence and harassment by private individuals, organizations or groups - also have risen since 2007, the year Pew Research Center began tracking the issue. Indeed, the latest data shows that 52 governments - including some in very populous countries like China, Indonesia and Russia ...

As noted recently by U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, the authority to protect and promote communal health is balanced with constitutional or other legal rights of individuals to act or behave as they wish provided they do not harm others. 1 In many cases, the scales are appropriately weighted to respect individual freedoms while advancing ...

June 17, 2021. In the legal battle between religious rights and gay rights, religious freedom gained a victory today. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously that the First Amendment's ...

The thesis of this paper is that freedom of religion is a remedy that redresses the (warranted) exclusion of certain religious arguments from the democratic process. The redress is grounded in a ...

The United States has long incorporated the promotion of international religious freedom into its foreign policy in some form, although the legal framework became more robust with the 1998 International Religious Freedom Act (IRFA) and its more recent amendment, the 2016 Frank R. Wolf International Religious Freedom Act.

As such, we question the religious market theory literature's conclusion that the freest religious markets must have the greatest levels of religious participation. We also raise concerns about current measures of religious freedom's capacity to measure individuals' freedom in Muslim-majority countries.

AbstractRésumé. Religious freedom (RF) is important because it is posited to be a central element of liberal democracy and as having multiple additional benefits including increased security and economic prosperity. Yet, it is also a disputed concept and many liberal democracies restrict the freedoms of religious minorities.

Social harassment. The increases in government restrictions were mirrored in the opposite by the rates of social harassment of religions. In 2021, the SHI dropped from 1.8 in 2020 to 1.6. While ...

A new Pew Research Center survey finds that 80% of U.S. adults say religion's role in American life is shrinking - a percentage that's as high as it's ever been in our surveys. Most Americans who say religion's influence is shrinking are not happy about it. Overall, 49% of U.S. adults say both that religion is losing influence and ...

I will make a different argument: that for academic freedom to prevail, all at Harvard must tolerate others and their beliefs. Religious and more generally ideological wars are often disastrous ...

The research on religion and civil society is directly relevant to issues of religious freedom because, conceptually, religious freedom is an integral part of civil society. Madsen ( 1998) pioneered this research in his examination of China's Catholics in the emerging civil society.