Student Engagement and School Dropout: Theories, Evidence, and Future Directions

- First Online: 20 October 2022

Cite this chapter

- Isabelle Archambault 3 ,

- Michel Janosz 3 ,

- Elizabeth Olivier 3 &

- Véronique Dupéré 3

3269 Accesses

13 Citations

School dropout is a major preoccupation in all countries. Several factors contribute to this outcome, but research suggests that dropouts mostly have gone through a process of disengaging from school. This chapter aims to present a synthesis of this process according to the major theories in the field and review empirical research linking student disengagement and school dropout. This chapter also presents the common risk and protective factors associated with these two issues, the profiles of students who drop out as well as the disengagement trajectories they follow and leading to their decision to quit school. Finally, it highlights the main challenges as well as the future directions that research should prioritize in the study of student engagement and school dropout.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Afia, K., Dion, E., Dupéré, V., Archambault, I., & Toste, J. (2019). Parenting practices during middle adolescence and high school dropout. Journal of Adolescence, 76 , 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.08.012

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Agirdag, O., Van Houtte, M., & Van Avermaet, P. (2013). School segregation and self-fulfilling prophecies as determinants of academic achievement in Flanders. In S. De Groof & M. Elchardus (Eds.), Early school leaving and youth unemployment (pp. 46e74) . Amsterdam University Press.

Google Scholar

Alexander, K. L., Entwisle, D. R., & Kabbani, N. S. (2001). The dropout process in life course perspective: Early risk factors at home and school. Teachers College Record, 103 (5), 760–822. https://doi.org/10.1111/0161-4681.00134

Article Google Scholar

Alliance for Excellent Education. (2013). Saving futures, saving dollars: The impact of education on crime reduction and earnings . Retrived from https://mk0all4edorgjxiy8xf9.kinstacdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/SavingFutures.pdf .

Appleton, J. J., Christenson, S. L., Kim, D., & Reschly, A. L. (2006). Measuring cognitive and psychological engagement: Validation of the student engagement instrument. Journal of School Psychology, 44 (5), 427–445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2006.04.002

Archambault, I., Pascal, S., Tardif-Grenier, K., Dupéré, V., Janosz, M., Parent, S., & Pagani, L. (2021). The contribution of teacher structure, involvement, and autonomy support on student engagement in low-income elementary schools. Teachers and Teaching, 26 (5–6), 428–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2020.1863208

Archambault, I., & Dupéré, V. (2017). Joint trajectories of behavioral, affective, and cognitive engagement in elementary school. The Journal of Educational Research, 110 (2), 188–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2015.1060931

Archambault, I., Janosz, M., Dupéré, V., Brault, M.-C., & Andrew, M. M. (2017). Individual, social, and family factors associated with high school dropout among low- SES youth: Differential effects as a function of immigrant status. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 87 (3), 456–477. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12159

Archambault, I., Janosz, M., Fallu, J.-S., & Pagani, L. S. (2009a). Student engagement and its relationship with early high school dropout. Journal of Adolescence, 32 (3), 651–670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.06.007

Archambault, I., Janosz, M., Morizot, J., & Pagani, L. (2009b). Adolescent behavioral, affective, and cognitive engagement in school: Relationship to dropout. Journal of School Health, 79 (9), 408–415. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2009.00428.x

Basharpoor, S., Issazadegan, A., Zahed, A., & Ahmadian, L. (2013). Comparing academic self-concept and engagement to school between students with learning disabilities and normal. The Journal of Education and Learning Studies, 5 , 47–64.

Bingham, G. E., & Okagaki, L. (2012). Ethnicity and student engagement. In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 65–95). Springer Science + Business Media). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7_4

Chapter Google Scholar

Björklund, A., & Salvanes, K. G. (2011). Education and family background: Mechanisms and policies. In E. A. Hanushek, S. Machin, & L. Woessmann (Eds.), Handbook in economics of education (Vol. 3, pp. 201–247). Elsevier.

Blondal, K. S., & Adalbjarnardottir, S. (2014). Parenting in relation to school dropout through student engagement: A longitudinal study. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76 (4), 778–795. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12125

Bowers, A. J., & Sprott, R. (2012). Why tenth graders fail to finish high school: A dropout typology latent class analysis. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk, 17 (3), 129–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/10824669.2012.692071

Brault, M.-C., Janosz, M., & Archambault, I. (2014). Effects of school composition and school climate on teacher expectations of students: A multilevel analysis. Teaching and Teacher Education, 44 , 148–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.08.008

Brière, F. N., Pascal, S., Dupéré, V., Castellanos-Ryan, N., Allard, F., Yale-Soulière, G., & Janosz, M. (2017). Depressive and anxious symptoms and the risk of secondary school non-completion. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 211 , 163–168. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.117.201418

Brooks-Gunn, J., & Duncan, G. J. (1997). The effects of poverty on children. The Future of Children: Children and Poverty, 7 (2), 55–71. https://doi.org/10.2307/1602387

Brozo, W. G., Sulkunen, S., Shiel, G., Garbe, C., Pandian, A., & Valtin, R. (2014). Reading, gender, and engagement. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 57 (7), 584–593. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.291

Buhs, E. S., Koziol, N. A., Rudasill, K. M., & Crockett, L. J. (2018). Early temperament and middle school engagement: School social relationships as mediating processes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 110 (3), 338–354. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000224

Buhs, E. S. (2005). Peer rejection, negative peer treatment, and school adjustment: Self-concept and classroom engagement as mediating processes. Journal of School Psychology, 43 (5), 407–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2005.09.001

Cappella, E., Kim, H. Y., Neal, J. W., & Jackson, D. R. (2013). Classroom peer relationships and behavioral engagement in elementary school: The role of social network equity. American Journal of Community Psychology, 52 (3–4), 367–379. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-013-9603-5

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Caraway, K., Tucker, C. M., Reinke, W. M., & Hall, C. (2003). Self-efficacy, goal orientation and fear of failure as predictors of school engagement in high school students. Psychology in the Schools, 40 (4), 417–427. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.10092

Carmona-Halty, M., Salanova, M., Llorens, S., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2019). Linking positive emotions and academic performance: The mediated role of academic psychological capital and academic engagement. Current Psychology , 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00227-8

Chen, J., Huebner, E., & Tian, L. (2020). Longitudinal relations between hope and academic achievement in elementary school students: Behavioral engagement as a mediator. Learning and Individual Differences, 78 , 101824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2020.101824

Cicchetti, D., & Rogosch, F. A. (1996). Equifinality and multifinality in developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 8 , 597–600. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579400007318

Chiefs Assembly on Education. (2012). A portrait of first nations and education. Retrived from https://www.afn.ca/uploads/files/events/fact_sheet-ccoe-3.pdf

Christenson, S. L., & Thurlow, M. L. (2004). School dropouts: Prevention considerations, interventions, and challenges. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13 (1), 36–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.01301010.x

Christle, C. A., Jolivette, K., & Nelson, M. (2007). School characteristics related to high school dropout rates. Remedial and Special Education, 28 (6), 325–339. https://doi.org/10.1177/07419325070280060201

Cleary, T. J., et al. (2021). Linking student self-regulated learning profiles to achievement and engagement in mathematics. Psychology in the Schools, 58 (3), 443–457. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22456

Cornell, D., Gregory, A., Huang, F., & Fan, X. (2013). Perceived prevalence of teasing and bullying predicts high school dropout rates. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105 (1), 138–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030416

Crosnoe, R., & Johnson, M. K. (2011). Research on adolescence in the twenty-first century. Annual Review of Sociology, 37 , 439–460. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-081309-150008

Crosnoe, R., & Turley, R. N. (2011). K-12 educational outcomes of immigrant youth. The Future of Children, 21 (1), 129–152. https://doi.org/10.1353/foc.2011.0008

Crowder, K. D., & South, S. J. (2003). Neighborhood distress and school dropout: The variable significance of community context. Social Science Research, 32 , 659–698. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0049-089X(03)00035-8

Crul, M., & Mollenkopf, J. (2012). The changing face of world cities: Young adult children of immigrants in Europe and the United States (pp. 3–25). Russell Sage Foundation. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7758/9781610447911

Curhan, A. L., Rabinowitz, J. A., Pas, E. T., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2020). Informant discrepancies in internalizing and externalizing symptoms in an at-risk sample: The role of parenting and school engagement. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49 (1), 311–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-01107-x

Danneel, S., Colpin, H., Goossens, L., Engels, M., Van Leeuwen, K., Van Den Noortgate, W., & Verschueren, K. (2019). Emotional school engagement and global self-esteem in adolescents: Genetic susceptibility to peer acceptance and rejection. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 65 (2), 158–182. https://doi.org/10.13110/merrpalmquar1982.65.2.0158

Datu, J. A. D., & King, R. B. (2018). Subjective Well-being is reciprocally associated with academic engagement: A short-term longitudinal study. Journal of School Psychology, 69 , 100–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2018.05.007

DePaoli, J. L., Hornig Fox, J., Ingram, E. S., Maushard, M., Bridgeland, J. M., & Balfanz, R. (2015). Building a grad nation: Progress and challenge in ending the high school dropout epidemic.

De Witte, K., Cabus, S., Thyssen, G., Groot, W., & van Den Brink, H. M. (2013). A critical review of the literature on school dropout. Educational Research Review, 10 , 13–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2013.05.002

Dierendonck, C., Milmeister, P., Kerger, S., & Poncelet, D. (2020). Examining the measure of student engagement in the classroom using the bifactor model: Increased validity when predicting misconduct at school. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 44 (3), 279–286. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025419876360

Dupéré, V., Dion, E., Cantin, S., Archambault, I., & Lacourse, E. (2020). Social contagion and high school dropout: The role of friends, romantic partners, and siblings. Journal of Education Psychology, 113 (3), 572–584. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000484

Dupéré, V., Dion, E., Leventhal, T., Crosnoe, R., Archambault, A., & Goulet, M. (2019). Circumstances preceding dropout among rural high schoolers: A comparison with urban peers. Journal of Research in Rural Education, 35 , 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000484

Dupéré, V., Dion, E., Leventhal, T., Archambault, I., Crosnoe, R., & Janosz, M. (2018). High school dropout in proximal context: The triggering role of stressful life events. Child Development, 89 (2), e107–e122. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12792

Dupéré, V., Leventhal, T., Dion, E., Crosnoe, R., Archambault, I., & Janosz, M. (2015). Stressors and turning points in high school and dropout: A stress process, life course framework. Review of Educational Research, 859 (4), 591–629. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654314559845

Duchesne, S., Larose, S., & Feng, B. (2019). Achievement goals and engagement with academic work in early high school: Does seeking help from teachers matter? The Journal of Early Adolescence, 39 (2), 222–252. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431617737626

Duckworth, A. (2015). OECD report of skills for social progress: The power of social emotional skills (Peer Commentary on IECD report). Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/edu/ceri/seminarandlaunchofthereportskillsforsocialprogressthepowerofsocialandemotionalskills.htm

Duncan, G. J., & Murnane, R. J. (2011). Whither opportunity? Rising inequality, schools, and children’s life chances . Russel Sage Foundation.

Eurostats. (2017). Decrease in “early school leavers” in the EU. Retrived from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/en/web/products-eurostat-news/-/edn-20170908-1 .

Fan, W., & Wolters, C. A. (2014). School motivation and high school dropout: The mediating role of educational expectations. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 84 (1), 22–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12002

Farrell, E. (1990). Hanging in and dropping out: Voices of at-risk students . Teachers College Press.

Finn, J. D. (1989). Withdrawing from school. Review of Educational Research, 59 (2), 117–142. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543059002117

Finn, J. D., & Zimmer, K. S. (2012). Student engagement: What is it? Why does it matter? In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 97–131). Springer.

Fortin, L., Royer, É., Potvin, P., Marcotte, D., & Yergeau, É. (2004). La prediction du risque de decrochage scolaire au secondaire : Facteurs personnels, familiaux et scolaires [Prediction of risk for secondary school dropout: Personal, family and school factors]. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 36 (3), 219–231. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0087232

Fraysier, K., Reschly, A., & Appleton, J. (2020). Predicting postsecondary enrollment with secondary student engagement data. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 38 (7), 882–899. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282920903168

Fredricks, J. A., Hofkens, T., Wang, M.-T., Mortenson, E., & Scott, P. (2018). Supporting girls’ and boys’ engagement in math and science learning: A mixed methods study. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 55 (2), 271–298. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21419

Fredricks, J. A., Ye, F., Wang, M., & Brauer, S. (2019). Profiles of school disengagement: Not all disengaged students are alike. In J. A. Fredricks, A. L. Reschly, & S. L. Christenson (Eds.), Handbook of student engagement interventions (pp. 31–43). Academic Press.

Fredricks, J. A., Wang, M., Schall, J., Hokfkens, T., Snug, H., Parr, A., & Allerton, J. (2016). Using qualitative methods to develop a survey of math and science engagement. Learning and Instruction, 43 , 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.01.009

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74 (1), 59–109. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001059

French, D. C., & Conrad, J. (2001). School dropout as predicted by peer rejection and antisocial behavior. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 11 (3), 225–244. https://doi.org/10.1111/1532-7795.00011

García Coll, C. G., & Marks, A. K. (Eds.). (2012). The immigrant paradox in children and adolescents: Is becoming American a developmental risk? American Psychological Association.

Garrett-Peters, P. T., Mokrova, I. L., Carr, R. C., Vernon-Feagans, L., & Family Life Project Key Investigators. (2019). Early student (dis)engagement: Contributions of household chaos, parenting, and self-regulatory skills. Developmental Psychology, 55 (7), 1480–1492. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000720

Georgiades, K., Boyle, M. H., & Duku, E. (2007). Contextual influences on children’s mental health and school performance: The moderating effects of family immigrant status. Child Development, 78 (5), 1572–1591. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01084.x

Gonzales, N. A., Wong, J. J., Toomey, R. B., Millsap, R., Dumka, L. E., & Mauricio, A. M. (2014). School engagement mediates long-term prevention effects for Mexican American adolescents. Prevention Science, 15 (6), 929–939. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-013-0454-y

Goulet, M., Clément, M.-E., Helie, S., & Villatte, A. (2020). Longitudinal associations between risk profiles, school dropout risk, and substance abuse in adolescence. Child & Youth Care Forum, 49 , 687–706.

Gubbels, J., van der Put, C. E., & Assink, M. (2019). Risk factors for school absenteeism and dropout: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48 (9), 1637–1667. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-01072-5

Henry, K. L., Knight, K. E., & Thornberry, T. P. (2012). School disengagement as a predictor of dropout, delinquency, and problem substance use during adolescence and early adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence , 41 (2), 156–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-011-9665-3 .

Hoff, E., Laursen, B., & Tardiff, T. (2002). Socioeconomic status and parenting. In P. M. Greenfield & R. R. Cocking (Eds.), Cross-cultural roots of minority children development (pp. 285–313). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Holen, S., Waaktaar, T., & Sagatun, Å. (2018). A chance lost in the prevention of school dropout? Teacher-student relationships mediate the effect of mental health problems on noncompletion of upper-secondary school. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 62 (5), 737–753. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2017.1306801

Hong, W., Zhen, R., Liu, R.-D., Wang, M.-T., Ding, Y., & Wang, J. (2020). The longitudinal linkages among Chinese children’s behavioral, cognitive, and emotional engagement within a mathematics context. Educational Psychology, 40 (6), 666–680. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2020.1719981

Hosan, N. E., & Hoglund, W. (2017). Do teacher–child relationship and friendship quality matter for children’s school engagement and academic skills? School Psychology Review, 46 (2), 201–218. https://doi.org/10.17105/SPR-2017-0043.V46-2

Hospel, V., & Galand, B. (2016). Are both classroom autonomy support and structure equally important for students’ engagement? A multilevel analysis. Learning and Instruction, 41 , 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2015.09.001

Hunt, J., Eisenberg, D., & Kilbourne, A. M. (2010). Consequences of receipt of a psychiatric diagnosis for completion of college. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 61 (4), 399–404. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2010.61.4.399

Hymel, S., Comfort, C., Schonert-Reichl, K., & McDougall, P. (1996). Academic failure and school dropout: The influence of peers. In J. Juvonen & K. R. Wentzel (Eds.), Cambridge studies in social and emotional development. Social motivation: Understanding children’s school adjustment (pp. 313–345). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511571190.015

Jang, H., Kim, E. J., & Reeve, J. (2012). Longitudinal test of self-determination theory’s motivation mediation model in a naturally occurring classroom context. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104 (4), 1175–1188. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028089

Janosz, M., Archambault, I., Morizot, J., & Pagani, L. S. (2008a). School engagement trajectories and their differential predictive relations to dropout. Journal of Social Issues, 64 (1), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2008.00546.x

Janosz, M., Archambault, I., Pagani, L. S., Pascal, S., Morin, A. J., & Bowen, F. (2008b). Are there detrimental effects of witnessing school violence in early adolescence? The Journal of Adolescent Health : Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 43 (6), 600–608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.04.011

Janosz, M., Le Blanc, M., Boulerice, B., & Tremblay, R. E. (2000). Predicting different types of school dropouts: A typological approach with two longitudinal samples. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92 (1), 171–190. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.92.1.171

Janosz, M., Le Blanc, M., Boulerice, B., & Tremblay, R. E. (1997). Disentangling the weight of school dropout predictors: A test on two longitudinal samples. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 26 (6), 733–762. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022300826371

Jiang, S., & Dong, L. (2020). The effects of teacher discrimination on depression among migrant adolescents: Mediated by school engagement and moderated by poverty status. Journal of Affective Disorders, 275 , 260–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.029

Jimerson, S. R., Campos, E., & Greif, J. L. (2003). Towards an understanding of definitions and measures of school engagement and related terms. The California School Psychologist, 8 , 7e28. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4405(00)00051-0

Jimerson, S. R., Egeland, B., Sroufe, L. A., & Carlson, B. (2000). A prospective longitudinal study of high school dropouts: Examining multiple predictors across development. Journal of School Psychology, 38 (6), 525–549. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4405(00)00051-0

Jordan, W. J., McPartland, J. M., & Lara, J. (1999). Rethinking the causes of high school dropout. The Prevention Researcher, 6 , 1–4.

Krauss, S. E., Kornbluh, M., & Zeldin, S. (2017). Community predictors of school engagement: The role of families and youth-adult partnership in Malaysia. Children and Youth Services Review, 73 , 328–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.01.009

Korhonen, J., Linnanmäki, K., & Aunio, P. (2014). Learning difficulties, academic well-being and educational dropout: A person-centered approach. Learning & Individual Differences, 31 , 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2013.12.011

Kurdi, V., & Archambault, I. (2020). Self-perceptions and engagement in low socio-economic elementary school students: The moderating effects of immigration status and anxiety. School Mental Health, 12 , 400–416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-020-09360-3

Ladd, G. W., & Dinella, L. M. (2009). Continuity and change in early school engagement: Predictive of children’s achievement trajectories from first to eighth grade? Journal of Educational Psychology, 101 (1), 190–206. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013153

Ladd, G. W., Kochenderfer, B. J., & Coleman, C. C. (1997). Classroom peer acceptance, friendship, and victimization: Distinct relational systems that contribute uniquely to children’s school adjustment? Child Development, 68 (6), 1181–1197. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1132300

PubMed Google Scholar

Landis, R. N., & Reschly, A. L. (2013). Reexamining gifted underachievement and dropout through the lens of student engagement. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 36 (2), 220–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162353213480864

Lansford, J. E., Dodge, K. A., Pettit, G. S., & Bates, J. E. (2016). A public health perspective on school dropout and adult outcomes: A prospective study of risk and protective factors from age 5 to 27 years. Journal of Adolescent Health, 58 (6), 652–658. https://doi.org/10.1016/2Fj.jadohealth.2016.01.014

Lavoie, L., Dupéré, V., Dion, E., Crosnoe, R., Lacourse, É., & Archambault, I. (2019). Gender differences in adolescents’ exposure to stressful life events and differential links to impaired school functioning. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 47 (6), 1053–1064. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-018-00511-4

Lawson, M. A., & Lawson, H. A. (2013). New conceptual frameworks for student engagement research, policy, and practice. Review of Educational Research, 83 (3), 432–479. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654313480891

Leventhal, T., & Dupéré, V. (2019). Neighborhood effects on youth development in experimental and nonexperimental research. Annual Review of Developmental Psychology, 1 , 149–176. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-devpsych-121318-085221

Lewis, A. D., Huebner, E. S., Malone, P. S., & Valois, R. F. (2011). Life satisfaction and student engagement in adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40 (3), 249–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9517-6

Li, Y., & Lerner, R. M. (2013). Interrelations of behavioral, emotional, and cognitive school engagement in high school students. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42 (1), 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9857-5

Li, Y., & Lerner, R. M. (2011). Trajectories of school engagement during adolescence:Implications for grades, depression, delinquency, and substance use. Developmental Psychology, 47 (1), 233–247. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021307

Li, Y., Lerner, J. V., & Lerner, R. M. (2010). Personal and ecological assets and academic competence in early adolescence: The mediating role of school engagement. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39 , 801–815. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9535-4

Liu, R.-D., Zhen, R., Ding, Y., Liu, Y., Wang, J., Jiang, R., & Xu, L. (2018). Teacher support and math engagement: Roles of academic self-efficacy and positive emotions. Educational Psychology, 38 (1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2017.1359238

Lovelace, M. D., Reschly, M. L., & Appleton, J. J. (2018). Beyond school records: The value of cognitive and affective engagement in predicting dropout and on-time graduation. Professional School Counseling, 21 (1), 70–84. https://doi.org/10.5330/1096-2409-21.1.70

Luo, W., Hughes, J. N., Liew, J., & Kwok, O. (2009). Classifying academically at-risk first graders into engagement types: Association with long-term achievement trajectories. The Elementary School Journal, 109 (4), 380–405. https://doi.org/10.1086/593939

Mahuteau, S., Karmel, T., Mavromaras, K., & Zhu, R. (2015). Educational outcomes of young Indigenous Australians . National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education, Curtin University, Bentley, viewed 7 February 2017. https://www.ncsehe.edu.au/educationaloutcomes-of-young-indigenous-australians/

Marsh, H. W., & Kleitman, S. (2005). Consequences of employment during high school: Character building, subversion of academic goals, or a threshold? American Educational Research Journal, 42 (2), 331–369. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312042002331

Martin, A. J. (2007). Examining a multidimensional model of student motivation and engagement using a construct validation approach. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77 , 413–440. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709906X118036

McDermott, E. R., Donlan, A. E., & Zaff, J. F. (2019). Why do students drop out? Turning points and long-term experiences. The Journal of Educational Research, 112 , 270–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2018.1517296

McDermott, E. R., Anderson, S., & Zaff, J. (2017). Dropout typologies: Relating profiles of risk and support to later educational re-engagement. Applied Developmental Science, 22 , 217–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2016.1270764

Melkevik, O., Nilsen, W., Evensen, M., Reneflot, A., & Mykletun, A. (2016). Internalizing disorders as risk factors for early school leaving: A systematic review. Adolescent Research Review, 1 (3), 245–255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-016-0024-1

Mojtabai, R., Stuart, E. A., Hwang, I., Eaton, W. W., Sampson, N., & Kessler, R. C. (2015). Long-term effects of mental disorders on educational attainment in the National Comorbidity Survey ten-year follow-up. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 50 (10), 1577–1591. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-015-1083-5

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2018). Equity in education: Breaking down barriers to social mobility . PISA, OECD.

Olivier, E., Galand, B., Morin, A. J. S., & Hospel, V. (2020a). Need-supportive teaching and student engagement : Comparing the additive, synergistic, and balanced contributions. Learning and Instruction, 71 , 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2020.101389

Olivier, E., Morin, A. J. S., Langlois, J., Tardif-Grenier, K., & Archambault, I. (2020b). Internalizing and externalizing behavior problems and student engagement in elementary and secondary school. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49 , 2327–2346. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01295-x

Olivier, E., Archambault, I., & Dupéré, V. (2018). Boys’ and girls’ latent profiles of behavior and social adjustment in school: Longitudinal links with later student behavioral engagement and academic achievement? Journal of School Psychology, 69 , 28–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2018.05.006

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2015). Helping immigrant students to succeed at school – and beyond . OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/education/Helping-immigrant-students-to-succeed-at-school-and-beyond.pdf

Pagani, L. S., Fitzpatrick, C., & Parent, S. (2012). Relating kindergarten attention to subsequent developmental pathways of classroom engagement in elementary school. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40 (5), 715–725. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-011-9605-4

Perry, J. C. (2008). School engagement among urban youth of color: Criterion pattern effects of vocational exploration and racial identity. Journal of Career Development, 34 (4), 397–422. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845308316293

Pintrich, P. R. (2004). Conceptual framework for assessing motivation and self-regulated learning in college students. Psychological Bulletin, 16 , 385–407.

Reeve, J. (2009). Why teachers adopt a controlling motivating style toward students and how they can become more autonomy supportive. Educational Psychologist, 44 (3), 159–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520903028990

Réseau Eurydice. (2010). Différences entre les genres en matière de réussite scolaire: étude sur les mesures prises et la situation actuelle en Europe.

Reschly, A. L., & Christenson, S. L. (2012). Jingle, jangle, and conceptual haziness: Evolution and future directions of the engagement construct. In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 3–19). Springer Science + Business Media). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7_1

Reschly, A., & Christenson, S. L. (2006a). Promoting school completion. In G. Bear & K. Minke (Eds.), Children’s needs III: Understanding and addressing the developmental needs of children . Bethesda.

Reschly, A. L., & Christenson, S. L. (2006b). Prediction of dropout among students with mild disabilities: A case for the inclusion of student engagement variables. Remedial and Special Education, 27 (5), 276–292. https://doi.org/10.1177/07419325060270050301

Rocque, M., & Snellings, Q. (2018). The new disciplinology: Research, theory, and remaining puzzles on the school-to-prison pipeline. Journal of Criminal Justice, 59 , 3–11.

Rosenthal, B. S. (1998). Non-school correlates of dropout: An integrative review of the literature. Children and Youth Services Review, 20 (5), 413–433. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0190-7409(98)00015-2

Rumberger, R. W. (2011). Dropping out: Why students drop out of high school and what can be done about it . Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674063167

Book Google Scholar

Rumberger, R. W., & Larson, K. A. (1998). Student mobility and the increased risk of high school dropout. American Journal of Education, 107 (1), 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1086/444201

Rumberger, R. W. (1987). High school dropouts: A review of issues and evidence. Review of Educational Research, 57 (2), 101–121. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543057002101

Samuel, R., & Burger, K. (2020). Negative life events, self-efficacy, and social support: Risk and protective factors for school dropout intentions and dropout. Journal of Educational Psychology, 112 (5), 973–986. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000406

Skinner, E. A., & Pitzer, J. R. (2012). Developmental dynamics of student engagement, coping, and everyday resilience. In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 21–44). Springer Science + Business Media). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7_2

Skinner, E. A., Kindermann, T. A., & Furrer, C. J. (2009). A motivational perspective on engagement and disaffection: Conceptualization and assessment of children’s behavioral and emotional participation in academic activities in the classroom. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 69 (3), 493–525. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164408323233

Skinner, E., Furrer, C., Marchand, G., & Kindermann, T. (2008). Engagement and disaffection in the classroom: Part of a larger motivational dynamic? Journal of Educational Psychology, 100 (4), 765–781. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012840

Skinner, E. A., & Belmont, M. J. (1993). Motivation in the classroom: Reciprocal effects of teacher behavior and student engagement across the school year. Journal of Educational Psychology, 85 (4), 571–581. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.85.4.571

Staffs, J., & Kreager, D. A. (2008). Too cool for school? Violence, peer status and high school dropout. Social Forces, 87 (1), 445–471. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.0.0068

Statistics Canada (2017). Insights on Canadian society young men and women without a high school diploma. Retrived from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-006-x/2017001/article/14824-fra.htm

Suárez-Orozco, C., Rhodes, J., & Milburn, M. (2009). Unraveling the immigrant paradox: Academic engagement and disengagement among recently arrived immigrant youth. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk, 6 , 7–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X09333647

Strand, S. (2014). School effects and ethnic, gender and socio-economic gaps in educational achievement at age 11. Oxford Review of Education, 40 (2), 223–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2014.891980

Taylor, G., Lekes, N., Gagnon, H., Kwan, L., & Koestner, R. (2012). Need satisfaction, work-school interference and school dropout: An application of self-determination theory. The British Journal of Educational Psychology, 82 (4), 622–646. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.2011.02050.x

Teese, R., Lamb, S., & Duru-Bellat, M. (2007). International studies in education inequality, theory and policy . Springer.

Tinto, V. (1975). Dropout from higher education: A theoretical synthesis of recent research. Review of Educational Research, 45 (1), 89–125. https://doi.org/10.2307/1170024

Tuominen-Soini, H., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2014). Schoolwork engagement and burnout among Finnish high school students and young adults: Profiles, progressions, and educational outcomes. Developmental Psychology, 50 (3), 649–662. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033898

Tyler, J., & Lofstrom, M. (2009). Finishing high school: Alternative pathways and dropout recovery. The Future of Children, 19 (1), 77–103. https://doi.org/10.1353/foc.0.0019

UNESCO. (2020). World inequality database on education . UNESCO Institute for Statistics.

U.S. Department of Commerce. (2017). Census bureau, current population survey (CPS), selected years, October 1977 through 2017 . Table 2.5. Retrived from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/dropout/ind_02.asp .

U.S. Department of Education. (2016). Digest of Education Statistics 2016, table 219.70. Retrived from https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2017/2017094.pdf

Van Uden, J. M., Ritzen, H., & Pieters, J. M. (2016). Enhancing student engagement in pre-vocational and vocational education: a learning history. Teachers and Teaching, 22 (8), 983–999. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2016.1200545

Véronneau, M.-H., Vitaro, F., Pedersen, S., & Tremblay, R. E. (2008). Do peers contribute to the likelihood of secondary school graduation among disadvantaged boys? Journal of Educational Psychology, 100 (2), 429–442. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.100.2.429

Wang, M. T., Fredricks, J., Ye, F., Hofkens, T., & Linn, J. S. (2019). Conceptualization and assessment of adolescents’ engagement and disengagement in school. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 35 (4), 592–606. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000431

Wang, M.-T., Kiuru, N., Degol, J. L., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2018). Friends, academic achievement, and school engagement during adolescence: A social network approach to peer influence and selection effects. Learning and Instruction, 58 , 148–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2018.06.003

Wang, M. T., Fredricks, J. A., Ye, F., Hofkens, T. L., & Linn, J. S. (2016). The math and science engagement scales: Scale development, validation, and psychometric properties. Learning and Instruction, 43 , 16–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.01.008

Wang, M. T., & Degol, J. (2014). Motivational pathways to STEM career choices: Using expectancy-value perspective to understand individual and gender differences in STEM fields. Developmental Review, 33 , 304e340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2013.08.001

Wang, M.-T., & Fredricks, J. A. (2014). The reciprocal links between school engagement, youth problem behaviors, and school dropout during adolescence. Child Development, 85 (2), 722–737. https://doi.org/10.1111/2Fcdev.12138

Wang, M. T., & Peck, S. C. (2013). Adolescent educational success and mental health vary across school engagement profiles. Developmental Psychology, 49 (7), 1266–1276. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030028

Wang, M.-T., Willett, J. B., & Eccles, J. S. (2011). The assessment of school engagement: Examining dimensionality and measurement invariance by gender and race/ethnicity. Journal of School Psychology, 49 (4), 465–480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2011.04.001

Wang, M.-T., & Eccles, J. S. (2012). Adolescent behavioral, emotional, and cognitive engagement trajectories in school and their differential relations to educational success. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 22 (1), 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2011.00753.x

Wehlage, G. G., Rutter, R. A., Smith, G. A., Lesko, N., & Fernandez, R. R. (1989). Reducing the risk: Schools as communities of support . The Falmer Press.

Wentzel, K. R., Jablansky, S., & Scalise, N. R. (2020). Peer social acceptance and academic achievement: A meta-analytic study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 113 (1), 157–180. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000468

Zhou, Q., Main, A., & Wang, Y. (2010). The relations of temperamental effortful control and anger/frustration to Chinese children’s academic achievement and social adjustment: A longitudinal study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102 (1), 180–196. https://doi.org/10.1037/a001590

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Montreal, Montreal, QC, Canada

Isabelle Archambault, Michel Janosz, Elizabeth Olivier & Véronique Dupéré

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Isabelle Archambault .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA

Amy L. Reschly

University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA

Sandra L. Christenson

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Archambault, I., Janosz, M., Olivier, E., Dupéré, V. (2022). Student Engagement and School Dropout: Theories, Evidence, and Future Directions. In: Reschly, A.L., Christenson, S.L. (eds) Handbook of Research on Student Engagement. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-07853-8_16

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-07853-8_16

Published : 20 October 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-07852-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-07853-8

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Open supplemental data

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Systematic review article, dropout in rural higher education: a systematic review.

- 1 School of Economic and Administrative Sciences, Corporación Universitaria de Asturias, Bogotá, Colombia

- 2 Faculty of Natural Sciences and Engineering, Universidad de Bogotá Jorge Tadeo Lozano, Bogotá, Colombia

Student dropout in higher education has been of great interest to the academic community, state and social actors over the last three decades, due to the various effects that this event has on the student, the family, higher education institutions, and the state itself. It is recognised that dropout at this level of education is extremely complex due to its multi-causality which is expressed in the existing relationship in its explanatory variables associated with the students, their socioeconomic and academic conditions, as well as the characteristics of the educational institutions. Thus, the aim of this article was to identify the individual, socioeconomic, academic, and institutional explanatory variables involved in student dropout in rural populations, based on a synthesis of the evidence available in the SCOPUS database. In order to achieve it, a mixed systematic review was defined under the PRISMA 2020 method. The analysis was approached in two stages; the first concerned the identification of the documents and the conformation of the sample, where 21 documents were distinguished for effectively dealing with dropout in rural higher education; and the second corresponded to the procedures defined for the development of the bibliometric analysis and synthesis of the information found in the documents. The results showed the distribution of studies by country, years of publication, the categorisation of the documents in SCOPUS, their classification by type and the methodologies used in the development of the studies analysed, as well as the variables that have been addressed in previous research. In this way, it is concluded that the results of the studies are not generalisable, either because of the size of the sample or because of the marked social asymmetries that exist in some countries, which can make the findings lack significance; on the other hand, the interest in research on variables associated with individual and academic determinants to explain rural student dropout is highlighted. In addition, some future research lines which can be addressed as a complement to the current view of the dropout event in rural higher education were identified.

Introduction

In the last three decades, the study of student dropout in higher education has become one of the lines of research of greatest interest for the academic community, state and social actors due to the high rates of this event, its multi-causality and the effects or consequences it has for the individual, the family, Higher Education Institutions (HEIs), society in general and the state. Considering what has been stated, it is also recognised that dropout rates worldwide have not been controlled and, on the contrary, have increased from an aggregate perspective, being sharpened by the health, economic and social crisis derived from COVID-19, which indicates the ineffectiveness of the actions of governments and HEIs, represented in public policies, the establishment of retention and graduation plans (P&GO for its Spanish acronym) and early warning systems (SAT for its Spanish acronym) ( Marquez-Vera et al., 2013 ; Orellana et al., 2021 ; UNESCO, 2021 ). An example of this is the situation in OECD countries where the dropout rate rose from 35% in 2005 to 64.5% in 2018, and in countries such as Luxembourg, Hungary, Sweden, Czech Republic and Slovakia this rate was higher than 70% ( OECD, 2018 ); or the particular case of Latin America, which has historically had high levels of dropout in higher education, close to 54%, and which are expected to increase as an effect of COVID-19 due to the strong social asymmetries that exist in the region ( Becerra et al., 2020 ; UNESCO, 2021 ).

Faced with the multi-causality of dropout, efforts have been made to establish the variables that explain current dropout rates and the causes that lead students not to complete their higher education studies, which has resulted in various perspectives and the development of tools that allow decision-makers to have a holistic view of dropout prevention and mitigation ( Kehm et al., 2019 ). That said, research has focused on analysing the influence of specific variables on the materialisation of dropout based on individual student conditions such as age, gender, marital status, family environment, intrinsic motivations and academic self-regulation (e.g., Ghignoni, 2017 ; Arias-Velandia et al., 2018 ; Behr et al., 2020 ); the student’s socioeconomic background exemplified by the socioeconomic stratum of the dwelling he or she lives in, family income, economic dependency and the macro-economic environment of the country (e.g., Contreras, 2017 ; Behr et al., 2020 ; Palacio et al., 2020 ; Schmitt et al., 2020 ); the academic factors represented in the development of competencies prior to entry into higher education, secondary school graduation tests, levels of satisfaction in the training programme and the number of courses concurrently taken (e.g., Guzmán, et al., 2020a ; Heidrich, 2018 ); and finally, institutional circumstances in relation to HEI policies, the technological and pedagogical resources provided by the educational institution, the level of interaction with teachers and students and the pedagogical model (e.g., Armstrong et al., 2018 ; Choi and Kim, 2018 ).

On the other hand, the analysis of the multi-causality of dropout has been widely linked to the construction of qualitative, quantitative and mixed models, with the aim of explaining the event in terms of multiple variables; of such studies, the developments made by Spady (1970) , Tinto and Cullen (1973) , Fishbein and Ajzen (1975) , as well as Tinto (1975 ; 1987) , which formed the basis of subsequent studies, and, more recently, Barragán and González (2017) , Pérez et al. (2019) , Venegas-Muggli (2020) , Kilian et al. (2020) , Segovia-Garcia and Said-Hung (2021) , among others.

However, the consequences of dropout for the actors in the tertiary education subsystem are usually varied. Thus, in the case of students, dropout represents the affectation of learning factors related to emotion, cognition, motivation, among others ( Hällsten, 2017 ), which has long-term repercussions on various difficulties, especially in terms of their work performance ( Hällsten, 2017 ; Sosu and Pheunpha, 2019 ). For the family, the student’s dropout symbolises a sunk cost, due to the expenses were incurred to cover the studies which will never be recovered, ( Moreno et al., 2019 ), as well as the destruction or impossibility of building long-term social capital that allows changing the family’s future conditions in both educational and socioeconomic aspects ( Ghignoni, 2017 ). As far as HEIs are concerned, the materialisation of this event means a difficulty in fulfilling their substantive functions ( Voelkle and Sander, 2008 ) by affecting the quality conditions of the training programmes and the reputation of the institutions ( Ortiz and Dehon, 2013 ), as well as impacting the income of HEIs in terms of student enrolments, since dropout represents an opportunity cost that translates into the loss of financial support ( Barragán and Rodríguez, 2015 ).

Finally, in the case of the state, the consequences of dropping out can be categorised as financial and social. In this sense, the materialisation of student dropout represents a damage to the resources made available by the State, since " (...) students who do not graduate on time (or at all) when they receive public funding consume valuable fiscal resources, which in many cases are not recoverable" ( The World Bank, 2017 , p. 14); and, on the other hand, dropout prevents the consolidation of the benefits of higher education by making it impossible to improve the average income of the population ( Cristia and Pulido, 2020 ), increase the productivity of the economy ( Cristia and Pulido, 2020 ), consolidate democratic processes ( Lance, 2011 ) and reduce crime ( Chalfin and Deza, 2019 ). In brief, student dropout in higher education can slow down the development and social transformation sought by implementing public policies related to access to higher education, hence the importance of its prevention and mitigation ( Guzmán et al., 2021 ).

Under the widespread interest of the academic community, state, and social actors in the study of dropout at the higher education level, multiple opportunities have been identified for understanding the event, especially in student groups such as those from or located in rural areas, ethnic minorities and those displaced by armed conflict, which have not been widely studied. This has been evidenced in literature reviews focused on identifying the variables that influence dropout by educational modality, (e.g., Kara et al., 2019 ; Guzmán et al., 2020b ; Orellana et al., 2021 ), the role of the intrinsic and extrinsic context to the student ( Broadbent and Poon, 2015 ), the methodological approach to the study of dropout ( Rodriguez Urrego, 2019 ) and the organisational perspective of the effects of dropout ( Fonseca and Garcia, 2016 ). Based on what has been previously stated, a holistic view of this event in rural higher education is required, due to the efforts made in recent years by states and HEIs to link a population that was marginalised, especially in developing countries, to the educational subsystem and to materialise the direct and indirect benefits of a higher level of education for the population, which are mitigated by the high dropout rates in rural areas. In addition, the lack of such a holistic view makes it difficult for decision-makers to develop effective and efficient public and institutional policies by governments and HEIs to deal with the event of dropout. Thus, the aim of this article was to identify the individual, socioeconomic, academic, and institutional explanatory variables involved in student dropout in rural populations, based on a synthesis of the evidence available in the SCOPUS database. Hence, student dropout in rural higher education merits a comprehensive view of the explanatory variables which affect it, in order to move towards its prevention and mitigation by the various actors in the tertiary education subsystem, especially the State and HEIs ( Gibbs, 1998 ; Byun et al., 2012 ; Guzmán et al., 2021 ; Snyder and Dillow, 2021 ). To guide the systematised review presented here, the following research questions were proposed:

RQ1: What trends have been followed in the study of student dropout in rural higher education in terms of the characteristics of publications and methodologies?

RQ2: What progress has been made in the study of student dropout in rural higher education, based on the determinants of study (individual, socio-economic, academic, and institutional)?

Accordingly, this article is structured in four main sections. The first section describes the conceptualisation of dropout and the theoretical reference model; the second, the methodology used to achieve the objective; the third, the main findings obtained with the implementation of the methodology; and the fourth, the discussions, conclusions, and final considerations.

Dropout and the Theoretical Reference Model

When referring to student dropout, multiple meanings have been developed both by the academic community and by state and social agents, which generates diverse points of view and an enrichment of the discussion around it ( Kehm et al., 2019 ), in other words, these perceptions are not mutually exclusive. As Guzmán et al. (2021) expressed it, the multiplicity of definitions derives from specific purposes of analysis, and they have the capacity to complement each other in order to give a broader view of dropping out. In relation with the wide variety of conceptual and operational definitions of this event, this article is based on the one given by the Alpha Guidance Project. Thus, drop-out is defined as "the cessation of the relationship between the student and the training programme leading to a higher education degree before the degree is achieved. An event of a complex, multidimensional and systemic nature, which can be understood as cause or effect, failure or reorientation of a training process, choice or obligatory response, or as an indicator of the quality of the education system" (ALFA GUIA Project DCI-ALA/2010/94, 2013, p. 6).

This definition encompasses both the analysis of specific variables and of the models developed. Consequently, its use allows the theoretical framework of student dropout to be understood from a holistic viewpoint, integrating the perspectives of the academic community, state and social agents. With this integration of perspectives, the study of dropout has been carried out from a multidisciplinary orientation in which the sociological, interactionist, organisational, psychological and economic approach are highlighted ( Lázaro Alvarez et al., 2020 ), and have resulted in the analysis of variables intrinsic and extrinsic to the student, categorising them into four determinants: individual, socioeconomic, academic and institutional ( Fonseca and García, 2016 ; Barragán and González, 2017 ; Donoso and Schiefelbein, 2021 ; Guzmán et al., 2021 ).

Thus, the sociological approach sets the basis for the study of dropout in higher education, assessing the influence of external factors on the student. The contributions made by Spady (1970) explained the event in terms of Durkheim’s theory of suicide, in which it is argued that this action is the result of the subject’s disconnection from the social system, and therefore, dropout is explained as the lack of social integration of the student into the higher education environment. In addition, this approach considered variables other than social integration in the HEI such as family, expectations and demands that affect the student’s academic potential and performance.

Subsequently, the mainstream study of drop-out emerged with its basis on the interactionist and organisational approaches in which this event is explained by the student’s academic and social interaction in the HEI. An example of this approach was the model developed by Tinto (1975 ; 1987) in which the student’s emotional and intellectual background was taken as a point of reference, also involving various individual, academic, and family characteristics that directly affect the student’s permanence in the HEI. Later mainstream models, such as Bean (1986) or Heublein et al. (2010) , incorporated other related variables such as funding opportunities for tuition and other costs associated with the level of education, organisational characteristics of the HEI and student effort, thus providing a broader picture of the drop-out event.

From the psychological perspective, the student’s own characteristics and attributes were incorporated, considering aspirations, values, personality, motivation, and expectations of success, so that the individual and his or her variables associated with dropout were observed ( Ethington, 1990 ). This approach has grouped studies that include psychological aspects of the student from the perspective of the educational sciences. Prior to the research carried out by Ethington (1990) , the explanatory variables of dropout associated with the student’s psyche were not incorporated into the models, which is why the variables categorised in the individual determinant have been incorporated from his analysis. Recent studies have shown the influence of variables such as self-determination ( Jeno et al., 2018 ), personality ( Alkan, 2014 ), introversion ( Migali and Zucchelli, 2017 ) and neuroticism ( Migali and Zucchelli, 2017 ).

Finally, the economic approach has privileged the socioeconomic context of the student and his or her family by evaluating the cost-benefit ratio of staying or dropping out of higher education ( Palacio et al., 2020 ), the influence of family income on the probability of not completing the educational process ( Adrogué and García de Fanelli, 2018 ), social class as a constraint to the creation of social capital ( Palacio et al., 2020 ), among others. While most studies have focused on the student and the family, they have also assessed the impact of the drop-out event on the operational income of HEIs and their financial sustainability ( Barragán and Rodríguez, 2015 ).

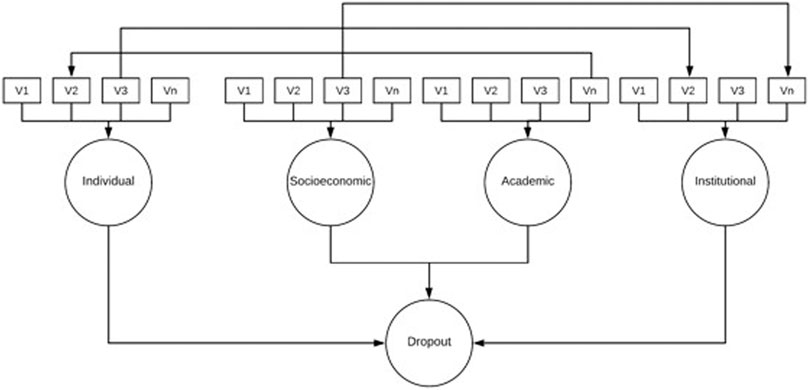

Based on this interdisciplinary orientation of the study of dropout and the categorisation of the explanatory variables into the four determinants, this article is linked to the conceptual model described in Figure 1 , which has been widely used in previous research (e.g., Barragán and González, 2017 ; Klein, 2019 ; Radovan, 2019 ; Kemper et al., 2020 ; Vera et al., 2020 ; Guzmán et al., 2021 ) as well as in the development of public policies such as in the Colombian case ( Ministry of National Education, 2009 ), because it is adaptive to the educational modality or type of student population, the new realities of the higher education context, as well as allowing the development of explanatory and predictive models of dropout in higher education ( Guzmán et al., 2021 ).

FIGURE 1 . Conceptual model of determinants of dropout. Note: Each determinant groups n variables v1, v2,...,vn as exemplified in the individual determinant. A variable can have an impact on other variables in the same or a different determinant.

Thus, the determinants are conceptualised as follows:

• Individual: describes the characteristics associated with the student and his/her personal environment that have a direct influence on the decision to leave the study process unfinished. Examples of the variables related to this determinant are age, gender, marital status, position in the number of siblings, health problems at the time of enrolment at HEI, family environment, fulfilled expectations, family and personal obligations, motivation in relation to the teaching and learning process, self-regulation, and time management.

• Socioeconomic: this refers to the influence of the social and economic context in which the student is immersed, and which may lead him/her not to complete the higher education process. Among the variables related to this determinant are the stratum, the employment situation, the economic income of the family nucleus and of the student, the economic dependence, and the macroeconomic environment of the country.

• Academic: these are all those variables related to the teaching and learning process both in previous levels of education and in higher education that may lead students to drop out. Among the variables of this determinant, the following stand out: previous academic performance, courses taken before higher education, secondary school graduation tests, results of admission exams to higher education, teaching qualifications and levels of satisfaction with the academic programme.

• Institutional: refers to all the characteristics of the HEIs that allow for the correct development of the learning process and others associated with the student, which, if they generate dissatisfaction in the student, may lead him/her not to complete the learning process. Examples of explanatory variables associated with the determinant are institutional policies, funding services, pedagogical resources, the level of interaction between teachers and students, as well as academic support.

Methodology

To carry out the systematic review developed in this article, and in order to achieve the proposed objective, a mixed study was defined under the PRISMA 2020 method. This method was intended for use in reviews that include syntheses of quantitative and qualitative information ( Page et al., 2021 ). Thus, under this approach, two stages were carried out. The first related to the identification of the documents (records); and the second to the analysis and synthesis of the findings.

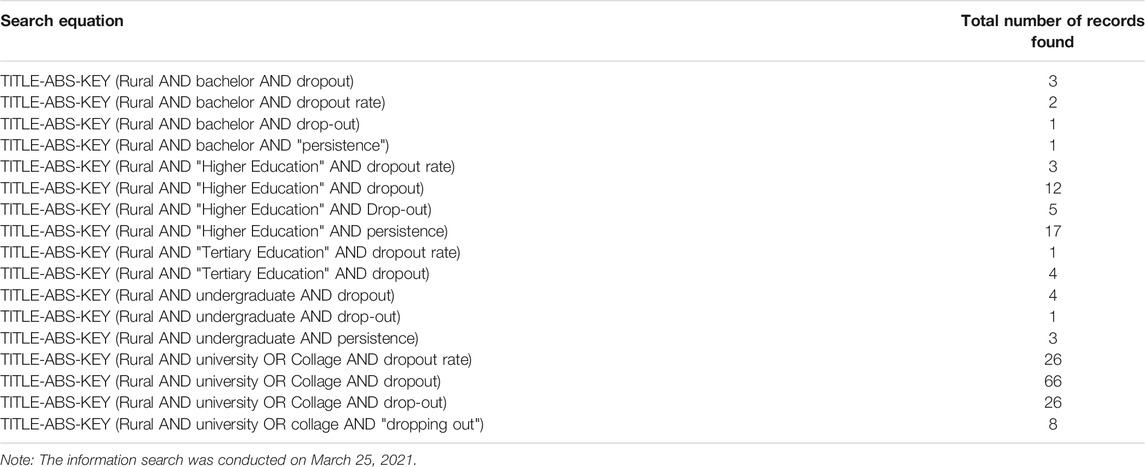

Stage One: Identification of the Documents and Sample Formation

In order to identify the literature with the greatest impact on higher education dropout in the rural student population, documents were searched in SCOPUS, which is a curated database of abstracts and citations of scientific documents (e.g., articles, books and conference proceedings), whose content is generally considered of the highest quality by the academic community, since each of the grouped documents is reviewed by peer reviewers and published under rigorous editorial processes ( Schotten et al., 2017 ). Thus, the equations presented in Table 1 were used to determine the search for the documents. The search was conducted in English, as SCOPUS lists titles, abstracts, and keywords in that language. In addition, other filters were not used in the search for information such as: the period of publication, the geographical area of the study and the quartile of categorisation of the journals determined by SCOPUS. This was not considered relevant because previous empirical research (e.g., Byun et al., 2012 ; Guzmán et al., 2021 ) highlighted the lack of studies in a generalized manner, for that reason it was sought to include as many studies as possible with the purpose of avoiding the loss of information. In addition, the search for documents was limited to articles, books, book chapters and conference proceedings. On the other hand, for the selection of search keywords, reference to those used in previous systematic literature reviews was made such as Orellana et al. (2021) , Guzmán et al. (2020a) , Rodriguez Urrego (2019) and Kara et al. (2019) , as well as recent empirical studies such as Guzmán et al. (2021) , Behr et al. (2020) , Kehm et al. (2019) , Barragán and González (2017) , as well as Vera et al. (2020) .

TABLE 1 . Ratio of records found by search equation.

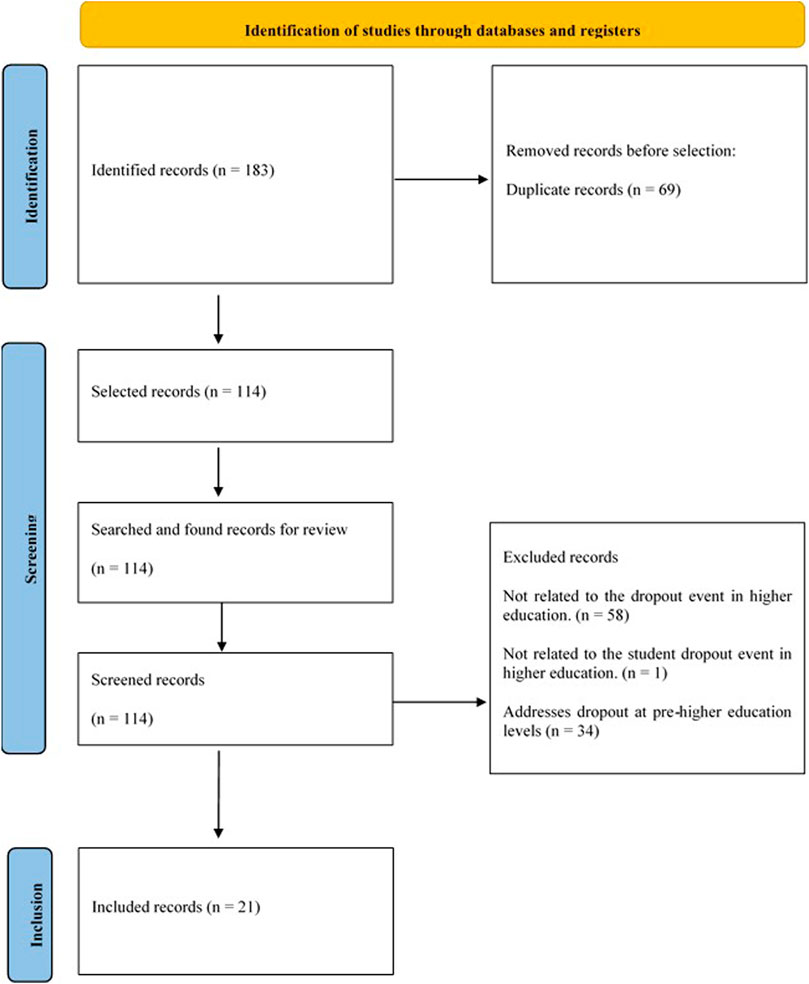

As a result of the SCOPUS search, a total of 183 documents possibly related to the event of dropout in rural higher education were detected, which were registered in a database composed of the following data: type of document, year, authors, title of the document, journal, name of the book or conference proceedings, quartile of citation classification (only applied to journals), ISSN or ISBN, and keywords. From the documents found, a total of 69 were eliminated because they were duplicate records. Thus, with the remaining 114 records, the titles, abstracts, and keywords were read, with the intention of purging those documents not related to the topic of study, consolidating the documentary analysis sample consisting of 17 articles, one book chapter resulting from research and three conference proceedings. It is important to highlight that in the screening phase, and in order to eliminate bias in the selection of the documents, an independent review was carried out by each of the authors, evaluating the full text in the case of those documents in which the concepts were not unanimous. In addition, the PRISMA 2020 checklist was completed for each of the documents. Figure 2 shows the flow diagram of the PRISMA 2020 method.

FIGURE 2 . PRISMA 2020 method flow chart. Adapted from ( Page et al., 2021 ).

Stage Two: Analysis and Synthesis

This stage sought to analyse and synthesise the findings to fulfil the objective of this article. In this way, two phases were carried out: the first was related to the bibliometric analysis of the documents included for review using descriptive statistics and data visualisation in accordance with the parameters established by Nightingale (2009) . This phase sought to respond to RQ1. In this way, the country of origin in which the research was carried out, the frequency of publication per year, the categorisation of the articles according to SCOPUS ranking, methodologies used in the development of the studies, among others, were determined. The second phase corresponded to the content analysis of the documents, which answered RQ2, in which the explanatory variables of dropout in rural higher education were sought and associated with each of the determinants of the model described in Figure 1 . Thus, each of the sample documents was loaded into the Atlas. ti software and the open coding technique was carried out, as it allows the researcher to establish categories or variables from the reading of the documents, so it is not limited to a pre-established theoretical framework, which results in the possibility of providing answers to questions of a general nature ( Flick, 2012 ). After coding the variables, the findings were synthesised using an inductive approach.

Bibliometric Analysis

The review of the sample of papers showed that research had been carried out in ten countries of origin. Thus, seven papers related to rural people in higher education were published in the United States, two in Finland, two in Australia, and, in the case of Bangladesh, Brazil, China, Colombia, Ecuador, Norway and South Africa, one publication each. On the other hand, three of the papers in the sample did not specify the countries in which the research took place.

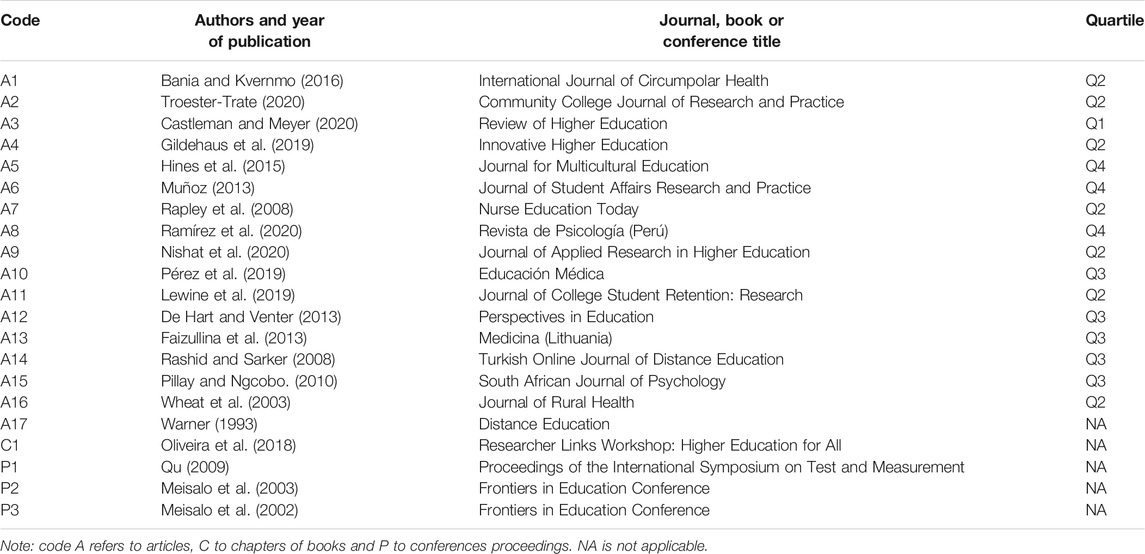

However, regarding the distribution of the sample by year of publication, no trend was evident, although it was observed that after 2010 the academic community’s interest in the study of the event of dropout in the population under study at the higher level has grown, accounting for 52.38% of the documents analysed since that year (see Table 2 and Supplementary Figure S1 ).

TABLE 2 . Documents in the sample under analysis.

In relation to the 19 published articles that are susceptible to categorisation by the SCOPUS indicators, only 18 of the sample had such categorisation. Of the categorised articles, 6.25% were in quartile one, 43.75% in quartile two, 31.25% in quartile three and 18.75% in quartile four. Table 2 summarises the papers in the sample, showing that by journal or conference there is no preference in the publication of research related to rural dropout at higher education level.

About the methodological approach used in previous research, it was found that 71.41% of the studies were characterised by a quantitative approach, 14.29% by a qualitative approach and 14.3% by a mixed approach. Thus, the quantitative studies, and as presented in Supplementary Table S1 there is a tendency to use the survey as the main data collection technique. In the case of qualitative studies, data collection techniques focus on interviews (in-depth or semi-structured), focal groups and workshops, and finally, in mixed studies, both surveys, in-depth interviews and focal groups are used. Regarding the sample size, most of the studies are characterised by being relatively small in comparison to the country’s population, and more specifically, those students linked to higher education in rural areas. Thus, only 29% of the studies had samples larger than 1,000 students, 62% had samples smaller than 1,000 students and 10%, being academic experiences, did not reflect a sample in their methodological section.

Variables Influencing Rural Student Dropout in Higher Education

Corresponding to the model described in Figure 1 , the results of previous research by determinant are presented below. In this sense, a total of 59 variables that have been the object of study were coded. Supplementary Table S2 presents the explanatory variables found in each of the documents. According to Supplementary Table S2 , 35% of the explanatory variables studied for dropout in rural higher education corresponded to the individual determinant, 27% to the academic, 25% to the socio-economic and 13% to the individual. Thus, in the case of the most studied variables of dropout in rural higher education in the studies analysed, they correspond to: 1. the P&GO programmes, this variable has been analysed in 10 case studies; 2. Previous academic experience, being addressed in eight case studies; 3. the state support, the family income and the labour obligations, each of these was analysed in five case studies.

However, the explanatory variables that were only identified once in the documents studied, were: adaptation to the HEI, self-learning, communication, course contents, family dysfunction, ethnicity, lack of job opportunities, academic failure, absences from classes, dissatisfaction with the programme, slow academic progress, Learning Management System, personal goals, fear of failure, motivation, death of relatives, parents' educational level, poverty, nutrition problems, scheduling problems, relationship problems with parents, racism, knowledge recognition, transfer to another university and use of ICTs.

Individual Determinant

With regards to the gender variable, it is evident in the documents analysed that rural women are more likely to drop out of higher education, a situation that has been constant over time, as evidenced by Meisalo et al. (2002) in a population of students in virtual programmes, as well as ( De Hart and Venter, 2013 ) in face-to-face education. The latter authors emphasise that gender is a good predictor of rural students' intention to drop out of higher education because women tend to be more vulnerable as a result of housework and raising children, while men who drop out tend to do so because of work obligations or because they receive material in a second language, the last variable was analysed in the rural South African population, which is characterised by a large linguistic variety.

In relation to personal obligations represented in domestic and household chores, unemployed adults tend to drop out due to the need to provide basic goods and services to their houses, leading them to limit their spending to cover these needs, reducing or eliminating investments in education, so that if the chief member of the family or any of his relatives is the one who studies, he has to drop out, due to the economic insecurity that exists in rural areas ( Nishat et al., 2020 ; De Hart and Venter, 2013 ). In the case of the work obligations of rural students, research generally agrees that the hours allocated to work compete with study hours. This was reflected by Pérez et al. (2019) when analysing the causes of desertion of a group of rural nursing students, where the greatest number of absences were due to work-related causes, affecting the academic average and influencing the student’s decision to abandon their academic process. The same situation is described by ( De Hart and Venter, 2013 ) in rural students employed in the finance sector. On the other hand, it has been established that having partial work obligations such as part-time or service jobs are related to sources of stress for the student as they do not secure sufficient resources to cover their educational and personal expenses, leading them to prioritise seeking full-time employment and sacrificing their professional career ( Pillay and Ngcobo, 2010 ).

In terms of age, research has indicated that both younger and older students located in or coming from rural areas are at risk of dropping out, however, the causes are different. In this regard, Pillay and Ngcobo (2010) identified that arguments and conflicts with and between parents led to young students not completing their academic process. On the other hand, ( De Hart and Venter, 2013 ), established that, in developing countries, young students were the first generation to enter HEIs, so that support structures such as parents, close social references and HEIs' own support structures such as SATs and P&GOs could fail to effectively address the counselling needs of those students. In the case of older students, it was observed that the main reason for dropping out of education was due to work and personal obligations ( De Hart and Venter, 2013 ; Pillay and Ngcobo, 2010 ).

Following with the support structures, especially with parents, it became clear that the educational level of the parents is significantly related to the student’s intention to continue their educational process. Bania and Kvernmo (2016) found that for rural women a higher level of parental education had an influence on the completion of pre-higher education, while for men the level of parental education was related to the completion of higher education. However, the same study argues that the educational level of parents does not have an impact on the completion of higher education among young students.

Another variable related to rural dropout in higher education is the ethnicity or social group to which the student belongs. In this sense, the language in which the study material is designed has a direct impact on the continuity of the academic process, as argued by ( De Hart and Venter, 2013 ) in identifying this case in the Nguni community in South Africa, where unfamiliarity with the learner’s culture is propitious to the materialisation of the event. Another phenomenon related to this variable is the racism that students from social groups that have historically been considered minorities may suffer at the educational level, as is the case of Afro-descendants in the United States or illegal immigrants, in which social pressure can lead to a process of demotivation and end up in desertion ( Muñoz, 2013 ; Hines et al., 2015 ).

Regarding health as an explanatory variable of dropout, studies have focused on the psychological aspects of the student, finding that rural youth with behavioural problems tend to limit the number of years of study they take, which leads them to drop out of the education system or to choose less demanding training programmes, in which the risk of dropping out is greater for students who do not have behavioural problems ( Bania and Kvernmo, 2016 ). In this scenario, it should be recognised that male rural students with particular mental health conditions are more likely to fail to complete their training programme; this is related to the lack of search for HEI support structures ( Bania and Kvernmo, 2016 ). In addition to what has been stated, Hines et al. (2015) found in their research that student mental health affects academic and social processes, being a determinant of non-completion of their studies.

What is more, it has been documented that rural students have a variety of difficulties in adapting to HEIs ( Castleman and Meyer 2020 ). This is due to the change of educational environment involving commuting, creation of new personal relationships, conflict with the size of the educational institution and new academic demands, thus leading, in the words of Castleman and Meyer (2020) , to a "shock" that may end in student dropout. This was exemplified in the study by Ramírez et al. (2020) in which they segmented rural students who dropped out of a Colombian university, and who had in common the lack of adaptation to the HEI as the main reason for the materialisation of the desertion event.

Regarding other variables, Ramírez et al. (2020) identified that the type of family can influence the non-continuation of the educational process. Students with single-parent or extended nuclear families (parents, siblings, grandparents and aunts and uncles who live together in the same house) have a greater risk of not concluding their educational process, as explained in the case of those students with work and personal obligations ( Nishat et al., 2020 ) and in the case of the latter to sources of pressure and stress derived from the family environment ( Pillay and Ngcobo, 2010 ). The death of family members or close relatives as an explanatory variable of dropout is related as a source of stress which, in conjunction with other psychological problems of the student, leads him/her to not complete the training process ( Pillay and Ngcobo, 2010 ).

In relation to individual student variables related to the learning process, Meisalo et al. (2002) found an inversely proportional relationship between rural students' dropout and their attitude towards their academic process. Similarly, the lack of student autonomy in the development of academic activities, specifically in virtual programmes, was considered a persistent contributor to the occurrence of dropout ( Meisalo et al., 2002 ), hence, P&GOs focused on strengthening student autonomy in order to mitigate dropout rates in both virtual and face-to-face training programmes ( Gildehaus et al., 2019 ). Similarly, rural students in the study developed by Lewine et al. (2019) showed higher levels of motivation leading them to complete their higher education studies, explaining this phenomenon in the equivalence of effort, thus stipulating a curvilinear hypothesis of resilience in those who face more obstacles in their higher education, as is the case of rural students, seek to have better results in their formative process due to the additional effort they have to do in order to stay linked to the HEI ( Lewine et al., 2019 ). However, fear of failure can mitigate the resilience curve, especially in the first year of study ( Pillay and Ngcobo, 2010 ). Finally, rural students' procrastination affects their academic performance and may lead them to drop out due to loss of purpose ( Warner 1993 ).

Socioeconomic Determinant