03 Nov 2001 Susan B. Anthony on a Woman’s Right to Vote – 1873

Woman’s Rights to the Suffrage

by Susan B. Anthony (1820-1906)

This speech was delivered in 1873, after Anthony was arrested, tried and fined $100 for voting in the 1872 presidential election.

Friends and Fellow Citizens: I stand before you tonight under indictment for the alleged crime of having voted at the last presidential election, without having a lawful right to vote. It shall be my work this evening to prove to you that in thus voting, I not only committed no crime, but, instead, simply exercised my citizen’s rights, guaranteed to me and all United States citizens by the National Constitution, beyond the power of any State to deny.

The preamble of the Federal Constitution says:

“We, the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.”

It was we, the people; not we, the white male citizens; nor yet we, the male citizens; but we, the whole people, who formed the Union. And we formed it, not to give the blessings of liberty, but to secure them; not to the half of ourselves and the half of our posterity, but to the whole people–women as well as men. And it is a downright mockery to talk to women of their enjoyment of the blessings of liberty while they are denied the use of the only means of securing them provided by this democratic-republican government–the ballot.

For any State to make sex a qualification that must ever result in the disfranchisement of one entire half of the people is to pass a bill of attainder, or an ex post facto law, and is therefore a violation of the supreme law of the land. By it the blessings of liberty are for ever withheld from women and their female posterity. To them this government has no just powers derived from the consent of the governed. To them this government is not a democracy. It is not a republic. It is an odious aristocracy; a hateful oligarchy of sex; the most hateful aristocracy ever established on the face of the globe; an oligarchy of wealth, where the right govern the poor. An oligarchy of learning, where the educated govern the ignorant, or even an oligarchy of race, where the Saxon rules the African, might be endured; but this oligarchy of sex, which makes father, brothers, husband, sons, the oligarchs over the mother and sisters, the wife and daughters of every household–which ordains all men sovereigns, all women subjects, carries dissension, discord and rebellion into every home of the nation.

Webster, Worcester and Bouvier all define a citizen to be a person in the United States, entitled to vote and hold office.

The only question left to be settled now is: Are women persons? And I hardly believe any of our opponents will have the hardihood to say they are not. Being persons, then, women are citizens; and no State has a right to make any law, or to enforce any old law, that shall abridge their privileges or immunities. Hence, every discrimination against women in the constitutions and laws of the several States is today null and void, precisely as in every one against Negroes.

The National Center for Public Policy Research is a communications and research foundation supportive of a strong national defense and dedicated to providing free market solutions to today’s public policy problems. We believe that the principles of a free market, individual liberty and personal responsibility provide the greatest hope for meeting the challenges facing America in the 21st century. Learn More About Us Subscribe to Our Updates

Susan B. Anthony

Champion of temperance, abolition, the rights of labor, and equal pay for equal work, Susan Brownell Anthony became one of the most visible leaders of the women’s suffrage movement . Along with Elizabeth Cady Stanton , she traveled around the country delivering speeches in favor of women's suffrage.

Susan B. Anthony was born on February 15, 1820 in Adams, Massachusetts. Her father, Daniel, was a farmer and later a cotton mill owner and manager and was raised as a Quaker. Her mother, Lucy, came from a family that fought in the American Revolution and served in the Massachusetts state government. From an early age, Anthony was inspired by the Quaker belief that everyone was equal under God. That idea guided her throughout her life. She had seven brothers and sisters, many of whom became activists for justice and emancipation of slaves.

After many years of teaching, Anthony returned to her family who had moved to New York State. There she met William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass , who were friends of her father. Listening to them moved Susan to want to do more to help end slavery. She became an abolition activist, even though most people thought it was improper for women to give speeches in public. Anthony made many passionate speeches against slavery.

In 1848, a group of women held a convention at Seneca Falls , New York. It was the first Women’s Rights Convention in the United States and began the Suffrage movement. Her mother and sister attended the convention but Anthony did not. In 1851, Anthony met Elizabeth Cady Stanton. T he two women became good friends and worked together for over 50 years fighting for women’s rights. They traveled the country and Anthony gave speeches demanding that women be given the right to vote. At times, she risked being arrested for sharing her ideas in public.

Anthony was good at strategy. Her discipline, energy, and ability to organize made her a strong and successful leader. Anthony and Stanton co-founded the American Equal Rights Association. In 1868 they became editors of the Association’s newspaper, The Revolution , which helped to spread the ideas of equality and rights for women. Anthony began to lecture to raise money for publishing the newspaper and to support the suffrage movement. She became famous throughout the county. Many people admired her, yet others hated her ideas.

When Congress passed the 14 th and 15 th amendments which give voting rights to African American men, Anthony and Stanton were angry and opposed the legislation because it did not include the right to vote for women. Their belief led them to split from other suffragists. They thought the amendments should also have given women the right to vote. They formed the National Woman Suffrage Association , to push for a constitutional amendment giving women the right to vote.

In 1872, Anthony was arrested for voting. She was tried and fined $100 for her crime. This made many people angry and brought national attention to the suffrage movement. In 1876, she led a protest at the 1876 Centennial of our nation’s independence. She gave a speech—“Declaration of Rights”—written by Stanton and another suffragist, Matilda Joslyn Gage.

“Men, their rights, and nothing more; women, their rights, and nothing less.”

Anthony spent her life working for women’s rights. In 1888, she helped to merge the two largest suffrage associations into one, the National American Women’s Suffrage Association . She led the group until 1900. She traveled around the country giving speeches, gathering thousands of signatures on petitions, and lobbying Congress every year for women. Anthony died in 1906, 14 years before women were given the right to vote with the passage of the 19 th Amendment in 1920.

- Anthony, Susan. “Declaration of Rights of the Women of the United States by the National Woman Suffrage Association, July 4th, 1876.” The Elizabeth Cady Stanton & Susan B. Anthony Papers Project. http://ecssba.rutgers.edu/docs/decl.html . Accessed May 2016.

- “Biography of Susan B. Anthony.” National Susan B. Anthony Museum & House. http://susanbanthonyhouse.org/her-story/biography.php . Accessed May 2016.

- Lange, Allison. “Suffragist Organize: National Woman Suffrage Association.” National Women’s History Musuem. http://www.crusadeforthevote.org/nwsa-organize/ . Accessed May 2016.

- Lange, Allison. “Suffragist Unite: National American Woman Suffrage Association.” National Women’s History Museum. http://www.crusadeforthevote.org/nawsa-united/ . Accessed May 2016.

- Mayo, Edith. “Rights for Women: The Suffrage Movement and Its Leaders.” National Women’s History Museum. https://www.nwhm.org/online-exhibits/rightsforwomen/index.html . Accessed May 2016.

- “Susan B. Anthony.” National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/wori/learn/historyculture/susan-b-anthony.htm . Accessed May 2016.

- PHOTO: Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University .

MLA – Hayward, Nancy. “Susan B. Anthony.” National Women’s History Museum, 2017. Date accessed.

Chicago – Hayward, Nancy. “Susan B. Anthony.” National Women’s History Museum. 2017. www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/susan-brownell-anthony.

- Crusade for the Vote, National Women's History Museum

- Rights for Women, National Women's History Museum

- Susan B. Anthony House

- 1873 Speech of Susan B. Anthony on woman suffrage

- Susan B. Anthony House, National Park Service

- Susan B. Anthony, National Women's Hall of Fame

- Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony Project

- Public Broadcasting System (PBS) - "Not For Ourselves Alone: The Story of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony"

- Trial of Susan B. Anthony

- Anthony, Susan B. The Trial of Susan B. Anthony (Humanity Books, 2003).

- Anthony, Katherine Susan. Susan B. Anthony: Her Personal History and Her Era (Russell & Russell, 1975).

- Barry, Kathleen. Susan B. Anthony: A Biography of a Singular Feminist (Authorhouse, 2000).

- Dubois, Ellen Carol. The Elizabeth Cady Stanton-Susan B. Anthony Reader: Correspondences, Writings and Speeches (Boston: Northeaster University Press, 1992).

- Harper, Ida. Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony (Beaufort books - 3 volume set).

- Isaacs, Sally Senzell. America in the Time of Susan B. Anthony: The Story of Our Nation from Coast to Coast (Heinemann Library, 2000).

- Monsell, Helen Albee. Susan B. Anthony: Champion Women's Rights (Aladdin, 1986).

- Sherr, Lynn. Failure is Impossible: Susan B. Anthony in Her Own Words (Three Rivers Press, 1996).

- Stanton, Elizabeth Cady, Ann De Gordon, and Susan B. Anthony. Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony: In the School of Anti-Slavery, 1840-1866 (Rutgers, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1997).

- Ward, Geoffery C. and Ken Burns. Not For Ourselves Alone: The Story of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony (Knopf, 2001).

Related Biographies

Stacey Abrams

Abigail Smith Adams

Jane Addams

Toshiko Akiyoshi

Related background, mary church terrell , belva lockwood and the precedents she set for women’s rights, women’s rights lab: black women’s clubs, educational equality & title ix:.

A blog of the U.S. National Archives

Pieces of History

Susan B. Anthony: Women’s Right to Vote

The National Archives is celebrating the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment with the exhibit Rightfully Hers: American Women and the Vote , which runs in the Lawrence F. O’Brien Gallery of the National Archives in Washington, DC, through January 3, 2021. Today’s post comes from Michael J. Hancock in the National Archives History Office.

More than any other woman of her time, Susan B. Anthony recognized that many of the legal disabilities women faced were the result of their inability to vote.

Anthony worked tirelessly her whole adult life fighting for the right to vote, and she was instrumental in bringing the issue to the forefront of American consciousness.

She spoke publicly, petitioned Congress and state legislatures, and published a feminist newspaper for a cause that would not come to fruition until the ratification of the 19th Amendment , 14 years after her death in 1906.

Despite this, she found satisfaction in casting a ballot (albeit illegally) in Rochester, New York, on November 5, 1872. What followed was a trial for illegal voting and a unique opportunity for Anthony to broadcast her arguments for woman suffrage to a wider audience.

Anthony had planned to vote long before 1872. She reasoned that she would take the first opportunity as long as she met the New York state requirement of voters residing in their homes for at least 30 days prior to the election in the district where they cast their vote. Anthony’s logic was based on the recently adopted 14th Amendment that stated that “all persons born and naturalized in the United States . . . are citizens of the United States.” Anthony reasoned that that since women were citizens, and the privileges of citizens of the United States included the right to vote, states could not exclude women from the electorate.

The 15th Amendment’s reference to the “right of citizens of the United States to vote” suggested women’s right as citizens to vote. Fundamentally, woman suffragists’ objective was to validate their interpretation through either an act of Congress or a favorable decision in Federal courts.

On November 5, 1872, in the first district of the Eighth Ward of Rochester, New York, Anthony and 14 other women voted in an election that included choosing members of Congress. The women had successfully registered to vote several days earlier but, a poll watcher challenged Anthony’s qualification as a voter.

Taking the steps required by state law when a challenge occurred, the election inspectors asked Anthony under oath if she was a citizen, if she lived in the district, and if she had accepted bribes for her vote. Anthony answered these questions to their satisfaction, and the inspectors promptly placed her ballot in the boxes.

Nine days after the election, U.S. Commissioner William Storrs, an officer of the Federal courts, issued warrants for the arrest of Anthony and an order to the U.S. Marshal to deliver her to county jail along with the 14 other women who voted in Rochester. Based on the complaint of Sylvester Lewis, a poll watcher who challenged Anthony’s vote, the women were charged with voting for members of the U.S. House of Representatives “without having a lawful right to vote,” a violation of section 19 of the Enforcement Act of 1870.

Anthony’s attorneys researched a way to appeal her arrest and detention to the Supreme Court of the United States. They decided that a petition to the district court for a writ of habeas corpus would ensure it would reach the Supreme Court, even though Congress in 1868 had repealed the provision for appeals on writs of habeas corpus from the lower Federal courts to the Supreme Court. Attorney John Van Voorhis argued that Anthony had a right to vote and petitioned the district court for a writ of habeas corpus that would bring Anthony before the court so that the judge could rule if she were properly held in custody.

Judge Nathan Hall of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of New York granted the petition. The U.S. attorney announced that he was unprepared for argument, and the judge rescheduled the hearing for January in Albany.

At the district court session in Albany, Anthony’s attorney Henry Selden broadened the argument he made previously and insisted Anthony had a right to vote. He acknowledged that the question of women’s right to vote was still unresolved and that the government had no justification for holding her as a criminal defendant. Anthony’s release from custody was eventually denied.

Anthony’s trial began in Canandaigua, New York, on June 17, 1873. Before a jury of 12 men, Richard Crowley stated the government’s case and called an inspector of election as a witness to confirm that Anthony cast a ballot for congressional candidates.

Henry Selden had himself sworn in as a witness and testified that he advised Anthony that the Constitution validated her capacity to vote. In transcripts of Susan B. Anthony’s testimony in her own defense, it is clear that she was thoughtful and deliberate in her account of how she made the progression from interpretation of the Constitution to affirming her perceived rights under its principles.

Judge Hunt declared that “The Fourteenth Amendment gives no right to a woman to vote, and the voting by Miss Anthony was in violation of the law.” He rejected Anthony’s argument that her good faith prohibited a finding that she “knowingly” cast an illegal vote and stated that “Assuming that Miss Anthony believed she had a right to vote which was illegal, and thus is subject to the penalty of law.” He surprised Anthony and her attorney by directing the jury deliver a verdict of guilty.

In her sentencing, Susan B. Anthony was given the opportunity to address the court, and what she said stunned everyone in the courthouse:

Your honor, I have many things to say; for in your ordered verdict of guilty, you have trampled under foot every vital principle of our government. My natural right, my civil rights, my political rights, my judicial rights, are all alike ignored. Robbed of the fundamental privilege of citizenship, I am degraded from the status of a citizen to that of a subject; and not only myself individually, but all of my sex, are, by your honor’s verdict, doomed to political subjection under this, so-called, form of government.

Ultimately, Anthony was fined $100 and the cost of prosecution. In steadfast defiance, she declared that she would never pay a penny of her fine, and the government never made a serious effort to collect. In the end, Susan B. Anthony’s protest echoed the old revolutionary adage that “Resistance to tyranny is obedience to God.”

Share this:

6 thoughts on “ susan b. anthony: women’s right to vote ”.

Very interesting info, thank you!

thats all…

This is the amazing post which I liked the most, Thanks for creating such good content!

Source: https://tractorguru.in/vst-tractors

It was a good experience while reading your blogs. Thanks for sharing with us.

Iâm lucky enough to live right across the street from Mount Hope Cemetery where this tremendous patriotic women has been buried along with her family. We visit her every week & will especially visit her today & ask her to PLEASE watch over & bless this country and city she loved so very muchðºð¸ Thank you Susan

- Pingback: Images of the Week: Vote, Voting, Voted! – The Unwritten Record

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Undergraduate

- High School

- Architecture

- American History

- Asian History

- Antique Literature

- American Literature

- Asian Literature

- Classic English Literature

- World Literature

- Creative Writing

- Linguistics

- Criminal Justice

- Legal Issues

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Political Science

- World Affairs

- African-American Studies

- East European Studies

- Latin-American Studies

- Native-American Studies

- West European Studies

- Family and Consumer Science

- Social Issues

- Women and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Natural Sciences

- Pharmacology

- Earth science

- Agriculture

- Agricultural Studies

- Computer Science

- IT Management

- Mathematics

- Investments

- Engineering and Technology

- Engineering

- Aeronautics

- Medicine and Health

- Alternative Medicine

- Communications and Media

- Advertising

- Communication Strategies

- Public Relations

- Educational Theories

- Teacher's Career

- Chicago/Turabian

- Company Analysis

- Education Theories

- Shakespeare

- Canadian Studies

- Food Safety

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

- Movie Review

- Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

- Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Marketing Plan

- Multiple Choice Quiz

- Personal Statement

- Power Point Presentation

- Power Point Presentation With Speaker Notes

- Questionnaire

- Reaction Paper

Research Paper

- Research Proposal

- SWOT analysis

- Thesis Paper

- Online Quiz

- Literature Review

- Movie Analysis

- Statistics problem

- Math Problem

- All papers examples

- How It Works

- Money Back Policy

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- We Are Hiring

Rhetorical Analysis: On Women’s Right to Vote, Essay Example

Pages: 6

Words: 1715

Hire a Writer for Custom Essay

Use 10% Off Discount: "custom10" in 1 Click 👇

You are free to use it as an inspiration or a source for your own work.

Susan B. Anthony delivered her “On Women’s Right to Vote” speech after she was arrested and fined $100 for voting in the 1872 presidential election. To appreciate this speech, the history of its occasion should be considered. When ex-slaves were awarded the right to vote through passage of the 15 th amendment, many suffragists fought for the amendment to grant universal suffrage rather than suffrage for only this group. It was no surprise, then, the passion, anger, and persuasive message of women’s rights that Anthony used in her speech to the court when she was arrested in 1873. It is well known that this argument was a major turning point in history because it led to controversy and change for women in following years. To fully understand the reason behind why her speech went so well and persuaded many people to believe in her cause, it will be useful to conduct a rhetorical analysis; the method of speaking that Anthony uses involves logos, ethos, and pathos in “On Women’s Right to Vote” if used in any similar situation, should effectively promote the same change and action for a new speaker as it did for Anthony and her supporters.

The main argument Susan B. Anthony makes in “On Women’s Right to Vote” is the belief that women, like men, should be able to democratically elect their politicians. Women were still considered as somehow less human than men and had not been granted the same rights. Anthony argues that “For any State to make sex a qualification that must ever result in the disfranchisement of one entire half of the people is to pass a bill of attainder, or an ex post facto law, and is therefore a violation of the supreme law of the land” (15). In this statement, she directly refers to the fact that statements in the Constitution meant to provide rights and protections have historically only referred to the white male; after the ratification of the 15 th amendment, Constitutional rights were extended to colored people as well. Despite this, she argues against the fact that the Constitution doesn’t apply to 50 percent of the population in the United States. She uses the rest of her speech to explain why women’s rights are important and that women should receive the right to vote.

The purpose of this speech is to persuade the audience that women should be afforded the right to vote. When she delivers this speech, Susan B. Anthony is hoping to appeal to the audience in court. Specifically, the men and women who she believed that could be convinced that women should be afforded equal rights. The ultimate goal of her speech is to drive physical change by encouraging people who have not yet been involved in the women’s suffrage movement to take action.

Anthony’s appeal to her audience is particularly convincing due to her use of evidence throughout her speech When Susan B. Anthony says, “It shall be my work this evening to prove to you that in thus voting, I not only committed no crime, but, instead, simply exercised my citizen’s right, guaranteed to me and all United States citizens by the National Constitution, beyond the power of any State to deny” she appeals to the audience by comparing women’s rights to human rights. To support this argument, she uses the Constitution as a source both information and evidence because everyone that she is speaking to in the courthouse is expected to be fundamentally aware of law it describes. When she says this sentence, Anthony explains that women are not being treated as human beings despite the protections that the Constitution is supposed to afford to all people in this country. When Susan B. Anthony says, “And it is downright mockery to talk to women of their enjoyment of the blessings of liberty while they are denied the use of the only means of securing them provided by this democratic-republican government-the ballot.”, she appeals to the audience by using a specific example that supports the statement discussed above. Women cannot possibly enjoy the rights given to the people of this country if they are not allowed to vote using the ballot. By detailing the story that led to her arrest, she provides a concrete example of the inequality that the Constitution is unable to protect against. Therefore, in these parts of the speech, she emphasizes unfair treatment of women and demonstrates how they are being treated as inferior. In doing so, she persuades the audience that voting is the only way to start treating women as equals.

To strengthen her argument, Susan B. Anthony uses logos in her argument. Logos is a component of rhetoric that refers to the ability of a speaker to persuade by the use of reasoning. In this speech, Susan B. Anthony uses a combination of logic and reasoning several times in order to emphasize her point. Specifically she says, “It was we, the people; not we, the white male citizens; nor yet we, the male citizens; but we, the whole people, who formed this Union” (15). By doing so, she cites an exact phrase that was used in the Constitution of the United States and applied it to suffrage. By doing so, she uses reasoning to demonstrate that the country’s forefathers wanted equality for all people and this is the foundation on which this country was established. As a result of this reference, the audience was expected to connect more substantially with the purpose of her speech because they will draw the connection that she wants them to; the constitution applies to people as a whole, not just men, so women deserve the same rights that men are given.

Anthony uses a second example of logos when she states “Our democratic-republican government is based on the idea of the natural right of every individual member thereof to a voice and a vote in making and executing laws”. By doing so, she uses logical appeal to refer to the fact that she should have the right to vote under the Fourteenth Amendment and that the Constitution was supposed to ensure all citizens rights. She went on to say that, “the Declaration of Independence, the United States Constitution, the constitutions of several States and the organic laws of the Territories, all alike propose to protect the people in the exercise of their God-given rights”. Therefore her argument used deductive logical reasoning to show that if these documents were meant for all people, and they granted rights and protections, that women are people and should be given the same rights and protections.

A third example of logos refers to the terminology used in the Constitution; many people argued that the use of the words “he, his, and him” in the Constitution only refer to men, and therefore these rights only apply to men. She uses logical reasoning to retort that if only men are given these rights by the Constitution, then women should be freed from obligations like taxation because these documents clearly don’t refer to them. In addition, women are exempted from criminal laws under these conditions; since there is no she, hers, or her in these laws, only men are able to break the law. These examples above show how Susan B Anthony effectively uses logos to strengthen her argument.

Anthony uses another appeal in her argument in order to persuade her audience which is ethos. It refers to the credibility of the speaker. Susan B. Anthony uses ethos when she cites Senator Charles Sumner. She uses the credibly of a man who holds the same belief as her regarding her rights as a citizen. Many people both knew and respected the Senator in 1873. Since the male audience voted him into office, they should share many opinions with him. As a result, people would be more likely to believe in Anthony’s statement knowing she had some backup from a person who holds power.

Anthony uses ethos a second time when she cites the authority of a Quaker preacher, who holds authority on her subject because the preacher was prominent at the time that the country was being founded. If during the time that the Declaration of Independence was written, the Quakers believed that women should have equal value in society as men, it is interesting that this belief was lost as society continued to grow over time. Nonetheless, Anthony uses the reference to this Quaker preacher to appeal to her audience because his belief reflects the beliefs of this country’s forefathers, who intended all people to be treated equally.

A third example of ethos occurs when Anthony cites a reputable source that is the Fourteenth Amendment: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States, and of the State wherein they reside” (16). By this definition of the word citizen, then all the rights afforded by the Constitution should also apply to women; if this is the case, women have the right to vote under the laws that our country’s forefathers established.

Although Susan. B Anthony could have simply accepted the fine she received for trying to vote and not given a speech like this at her trial, she was so passionate about the women’s rights that she delivered this speech. Even though we read this speech rather than heard it being said, we can expect that when she recited this speech, the audience could detect emotion in her tone. In conclusion, Susan B. Anthony’s speech was highly effective because of the rhetorical principles that she took advantage of while conveying her message of women’s suffrage to the courts. The elements of rhetoric that she uses include logos, pathos, and ethos. She speaks in an ideal manner to her target audience and knows them well so she can maximize their response. Anthony makes her argument and purpose clear throughout the speech, using evidence and logic to support her statements. Eventually, this was an ideal speech because many of her listeners respected her opinion and became supporters of the women’s suffrage movement. This moment in history sparked belief in the idea of women’s rights, and many women in the United States today are able to enjoy its outcome.

Works Cited

Anthony, Susan B. “On Women’s Right to Vote”. Language Matters, Ed, Debra De Southlake, TX:Fountainhead Press, 2010.13-19.Print

Stuck with your Essay?

Get in touch with one of our experts for instant help!

From Childhood Through Adolescence, Essay Example

The Politics of Kenya, Research Paper Example

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free guarantee

Privacy guarantee

Secure checkout

Money back guarantee

Related Essay Samples & Examples

Voting as a civic responsibility, essay example.

Pages: 1

Words: 287

Utilitarianism and Its Applications, Essay Example

Words: 356

The Age-Related Changes of the Older Person, Essay Example

Pages: 2

Words: 448

The Problems ESOL Teachers Face, Essay Example

Pages: 8

Words: 2293

Should English Be the Primary Language? Essay Example

Pages: 4

Words: 999

The Term “Social Construction of Reality”, Essay Example

Words: 371

- HISTORY & CULTURE

Susan B. Anthony fought for women’s suffrage in the face of ridicule

This leading suffragist devoted her life to the movement but never got to vote—legally at least.

Susan B. Anthony was a leading force in the early suffragist movement and spent most of her life advocating for equal rights for women.

They called her “the woman who dared.” A tireless activist who crisscrossed the nation agitating for women’s rights in the 19th century, Susan B. Anthony devoted most of her 86 years to helping women get the vote. Though she was mocked, ridiculed, and often ignored, Anthony became one of the best known voices of the suffragist movement.

Born on February 15, 1820, Anthony was a member of an activist Quaker family. At first, Anthony was more interested in abolitionism than suffrage. She was first drawn to the nascent women’s rights movement by a different issue—pay equity—when she learned male teachers were paid four times her monthly salary.

Susan B. Anthony, left, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton were lifelong friends and activists. In a 1902 letter , Anthony wrote Stanton, “It is fifty-one years since we first met, and we have been busy through every one of them, stirring up the world to recognize the rights of women.”

Over time, Anthony became increasingly involved with social issues such as temperance and abolition. She agitated for more comfortable, less restrictive fashions for women along with feminist activist Amelia Bloomer, and in 1851 Bloomer introduced her to suffrage advocate Elizabeth Cady Stanton. They forged a lifelong friendship and collaborated on many reform issues.

Along the way, they encountered constant resistance to the idea of women speaking in public. Anthony, who had been raised to speak her mind, was incensed by being told to “listen and learn” at conventions in which males were encouraged to be vocal. She began to advocate for things like property rights and a woman’s right to divorce.

At first, Anthony continued her abolitionist activism, facing down riots and even being burned in effigy for speaking out against slavery. In 1866, she and Stanton founded the American Equal Rights Association, a group devoted to securing equal rights for all American citizens. (Related: Will the Equal Rights Amendment ever be ratified? )

But after the passage of the 14th Amendment guaranteeing formerly enslaved men the right to vote, a rift formed between those who thought that black men should be enfranchised before white women and those who wanted to prioritize women’s suffrage instead. Anthony interpreted Frederick Douglass ’s support of black male suffrage as an affront to women and split bitterly with him and his supporters, using racist rhetoric and saying “let…woman be first…and the negro last.”

After the split, Anthony devoted herself to women’s rights full time, publishing a feminist newspaper called the Revolution and eventually forming the National Woman Suffrage Association. She traveled the country much of the year , delivering impassioned lectures on women’s suffrage and lobbying state governments to extend the vote to women. She became a nationally recognizable (and much mocked) face of the suffrage movement.

In 1872, Anthony became even more visible when she was arrested and tried for voting in the presidential election. She was indicted by an all-male grand jury, tried by a judge who instructed the jury to find her guilty, and slapped with a $100 fine she refused to pay.

Six suffragists at the 1920 Republican National Convention in Chicago hold a banner with a quote from Anthony. Although Anthony died 14 years before women gained the right to vote, her message and drive carried on to the next generation of suffragists.

The trial was Anthony’s most controversial and public moment, but it did not stop her agitation on behalf of women’s rights. Throughout her later years, she co-wrote a history of women’s suffrage, helped broker a merger between the split national women’s suffrage groups, and continued to travel the country and even the globe speaking out for the right to vote. She ultimately reconciled with Douglass before his death in 1895.

“If I could only live another century!” she said in 1902. “I do so want to see the fruition of the work for women in the past century.” Four years later, Anthony died.

It would take until 1920 for the first women to legally vote in federal elections in the United States. Now, more than a century after her death, women bring their “I Voted” stickers to Anthony’s grave in Rochester on election days—a small but fitting tribute to the leader whose tireless work helped pave the way for women’s political rights.

FREE BONUS ISSUE

Related topics, you may also like.

A century after women’s suffrage, the fight for equality isn’t over

Arrested and tortured, the Silent Sentinels suffered for suffrage

4 countries where women have gained political power—and the obstacles they still face

She was Genghis Khan’s wife—and made the Mongol Empire possible

MLK and Malcolm X only met once. Here’s the story behind an iconic image.

- Environment

- Perpetual Planet

- History & Culture

History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Paid Content

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Susan B. Anthony’s Speech Analysis: Rhetorical Devices, Purpose, & More

📢 susan b. anthony speech analysis – introduction, 📝 logos in susan b. anthony’s speech, ✍️ ethos in susan b. anthony’s speech, 📜 historical parallels in susan b. anthony’s speech, ↪️ susan b. anthony speech rhetorical analysis – summary, 💡 work cited.

The speech delivered by Susan B. Anthony following her arrest for casting a vote in the presidential election stands as a remarkable exemplar of American oratory. In “On Women’s Right to Vote,” Anthony set forth a clear objective: to persuade her audience that women’s suffrage was not only constitutionally justified but also a fundamental right, as inherently granted to men. To achieve her goal, Anthony deftly employed a combination of logos, ethos, and historical parallels, weaving together a persuasive argument that resonated deeply with her listeners. With skillful logical reasoning, Susan B. Anthony established her credibility through ethos and cleverly linked the struggles of women to the historical struggle for equality. Anthony delivered a powerful and convincing plea for women’s right to vote. Her succinct yet impactful rhetoric not only left an indelible mark on the suffrage movement but also solidified her position as a key figure in the fight for women’s rights in American history. Read this essay sample of Susan B. Anthony’s speech analysis to learn more about her purpose, contribution, and rhetorical devices used.

Logos is, by far, the most prominent rhetorical strategy used in the speech. Essentially, the core of the author’s argument is a classical syllogism: the Constitution secures liberties for all people, women are people – therefore, women should enjoy the freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution – including suffrage – as much as men. She even adopts the form of a syllogism directly when she speaks of this discrimination from a legal perspective.

Any law that contradicts the universal suffrage is unconstitutional, and restrictions on voting are in contradiction to the Constitution – therefore, such law is “a violation of the supreme law of the land” (Anthony 5). Thus, Anthony represents her thesis – that women have the right to vote and restricting it is against the spirit and letter of the Constitution – as an inevitable logical conclusion of an impartial inquiry into the matter.

Anthony’s use of ethos is not typical, but all the more impressive because of that. Closer to the end of her speech, she mentions that the only way do deny citizens’ rights to women is to deny they are persons and doubts that her opponents “will have the hardihood to say they are not” (Anthony 8). As a rule, the speaker tries to establish credibility by pointing to something that makes him or her more competent to speak on a given topic than others, be that knowledge or personal experience. However, Anthony does not opt for that – rather, she appeals to a bare minimum of credibility a sentient creature is entitled to: being considered a person. While not elevating her above the audience, this appeal to credibility is still enough for her rhetorical purpose.

To further her case and root it in the audience’s relatively recent experiences, Anthony also draws a historical parallel with the emancipation and enfranchisement of former slaves. She emphasizes that the Constitution says, “we, the people; not we, the white male citizens” (Anthony 4). This specific reference to whiteness is a clear reference to the 15 th Amendment prohibiting the denial of the right to vote based on color, race, or previous condition of servitude.

By linking the issue of women’s suffrage to voting rights for black citizens, Anthony claims the former is an important progressive endeavor, just like the latter. This parallel is likely an attempt to appeal to the audience’s self-perception as progressive citizens of a free country. The implicit reasoning is clear: those who decided that race is an obstacle for casting a ballot cannot, in all honesty, claim that the gender is.

As one can see, Susan B. Anthony’s 1873 speech combines logos, ethos, and historical parallels to make a case for women’s voting rights. Anthony’s appeals to logic are simple and clear syllogisms based on the Constitution itself. She claims no greater credibility that is due to any sentient being, but that is just enough for her rhetorical purpose. Finally, a historical parallel with the recent enfranchisements of citizens of all races appeals to the audience’s sense of justice and self-perception as progressive people.

Anthony, Susan B. “ On Women’s Right to Vote. ” The History Place .

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2021, June 20). Susan B. Anthony’s Speech Analysis: Rhetorical Devices, Purpose, & More. https://studycorgi.com/susan-b-anthonys-speech-rhetorical-analysis/

"Susan B. Anthony’s Speech Analysis: Rhetorical Devices, Purpose, & More." StudyCorgi , 20 June 2021, studycorgi.com/susan-b-anthonys-speech-rhetorical-analysis/.

StudyCorgi . (2021) 'Susan B. Anthony’s Speech Analysis: Rhetorical Devices, Purpose, & More'. 20 June.

1. StudyCorgi . "Susan B. Anthony’s Speech Analysis: Rhetorical Devices, Purpose, & More." June 20, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/susan-b-anthonys-speech-rhetorical-analysis/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "Susan B. Anthony’s Speech Analysis: Rhetorical Devices, Purpose, & More." June 20, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/susan-b-anthonys-speech-rhetorical-analysis/.

StudyCorgi . 2021. "Susan B. Anthony’s Speech Analysis: Rhetorical Devices, Purpose, & More." June 20, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/susan-b-anthonys-speech-rhetorical-analysis/.

This paper, “Susan B. Anthony’s Speech Analysis: Rhetorical Devices, Purpose, & More”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: November 9, 2023 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

Susan B Anthony Women's Right To Vote Essay

Women's Voting Rights A woman voter, Susan B. Anthony, in her speech, Woman’s Right to Vote (1873), says that women should be allowed to vote. She supports this claim first by explaining that the preamble of the Federal Constitution states that she did not commit a crime, then she goes on about how women should be able to vote, then about how everyone hates the africans, and finally that the people of the United States should let women and africans vote. Anthony’s purpose is to make women able to vote in order to give women the right to vote on decisions made by the people. She creates a serious tone for the people of the United States. The author of this speech is talking to many different people. But the main people she is talking to are her fellow woman species of people. She is trying to make the woman able to vote. She also speaks to the africans …show more content…

Actually, this whole speech is ethos. The speech is about getting people to believe that women have the right to vote. And the definition of ethos is convincing someone of the character or credibility of the persuader. This speech is about convincing the people of the United States to refer to the written laws of the country. And then telling the people about how sorry they were for treating women like they were slaves. How they couldn’t vote and how they didn’t have the rights that white men had. But throughout the whole speech, she is trying to convince people to start a big ordeal on how white men are not the only ones able to vote. In conclusion, the author is speaking to her fellow women and the to the wrong white men of the United States. Her purpose of making this speech is that woman have just as much right to vote as white men do. The attitude toward the subject is very serious, and the attitude towards the listeners is also very serious. And Last, that the essay is pretty much an essay of ethos considering how much there is in the

Rhetorical Analysis Of Anthony's Speech

During the 1800s, women did not have the right to vote and were denied many other rights that all men had. In 1872, Anthony voted in the presidential election. Two weeks later, she was arrested. After her charge, Anthony gave her famous “Women's Right to Suffrage” speech. She stated in her speech,”It shall be my work this evening to prove to you that in thus voting, I not only committed no crime, but, instead, simply exercised my citizen’s rights.”

Florence Kelley's Speech

She asks a number of questions throughout the speech, specifically Kelley asks “If the mothers and teachers in Georgia could vote, would the Georgia Legislature have refused at every session for the last three years to stop the work in the mills of children under twelve years of age?”(lines 55-58) Kelley asks this question to assert the argument of women’s suffrage. Kelly argues that if women had the right to vote there would be better guidelines for child labor laws. Kelley also asks “ Would the New Jersey Legislature have passed that shameful repeal bill enabling girls of fourteen years to work all night, if the mothers in New Jersey were enfranchised?”(lines 59-62) Kelley takes this opportunity to emphasize the importance of women fighting for their rights to vote.

What Is The Right To Suffrage Speech By Susan B Anthony

A year later, she gave the speech intended to reach out to the nation, in hopes of the leaders to change their views on women’s rights. This speech gave Anthony the chance to finally speak up and encourage the U.S to join her in the fight for justice. By utilizing anaphora, sentence fragments, and asyndeton, Anthony empowers the nation to gain momentum towards the issue that was at hand: women’s rights.

Women In The Women's Suffrage Movement

Women used many different methods to earn the right to vote in the Women’s Suffrage Movement. One method women used to earn support is that they organized a parade in Washington, D.C., the same day the president was coming into town so that there was large crowds. Many of the people in the crowd were men who, along with drinking also disagreed with the right for women to vote. They began to yell then even throw objects at the women walking in the parade. Eventually, the police walked away giving the men the opportunity to attack.

Analyze The Causes Of The Progressive Movement

Women suffrage is a major problem that women doesn 't have to right to vote for what they believed in, When women should have every right to their opinion on the country they live in and should have just as much of a valued input and opinion as any man would have. Men and government often see women 's as a person who keep the house clean, wholesome, and feed her children properly. "If women would fulfill her traditional responsibility to her own children, Then she must bring herself to use the ballot, American women need

Women's Rights During The Progressive Era

During Progressive Era, there were many reforms that occurred, such as Child Labor Reform or Pure Food and Drug Act. Women Suffrage Movement was the last remarkable reform, and it was fighting about the right of women to vote, which was basically about women’s right movement. Many great leaders – Elizabeth Cad Stanton and Susan B. Anthony - formed the National American Women Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Although those influential leaders faced hardship during this movement, they never gave up and kept trying their best. This movement was occurred in New York that has a huge impact on the whole United States.

Women Suffrage Movement In The Progressive Era

During Progressive Era, there were many reforms that occurred, such as Child Labor Reform or Pure Food and Drug Act. Women Suffrage Movement was the last remarkable reform. This movement was fighting about the right of women to vote, which was basically about women’s right movement. Many great leaders – Elizabeth Cad Stanton and Susan B. Anthony - formed the National American Women Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Although those influential leaders faced hardship during this movement, they never gave up and kept trying their best.

Research Paper On Women's Suffrage Movement

Many speeches were given to help them gain their right. Susan B. Anthony gave speeches so that it would help them gain the support they needed for their journey. She did this to prove to women that they were not going to be taken seriously unless they prove that they can, which was getting that right for them. In 1872 Susan started doing things by herself. She went to vote illegally for the presidential election

The Fundamental Principle Of A Republic Summary

She states that men and women are equal and should have the same rights and should not be treated differently than each other. This quote by Anna from the speech backs this point up, “Now I want to make this proposition, and I believe every man will accept it. Of course, he will if he is intelligent. Whenever a Republic prescribes the qualifications as applying equally to all the citizens of the Republic, when the Republic says in order to vote, a citizen must be twenty-one years of age, it applies to all alike, there is no discrimination against any race or sex”. (Shaw,4)

Declaration Of Sentiments Rhetorical Analysis

This obviously shows she is on the side of women's rights in her argument and again, quoting the Declaration of Independence, gives her the quality of formality using lines from a piece that dear to American

Hillary Clinton Women's Rights Are Human Rights Essay

Clinton attempts to use propaganda, empathy, and logic to present her point, that women to her audience, and succeeds at it. Overall, the speech is balanced in its argument style and use of rhetoric, such as the factors mentioned above. At this point, Clinton was not a New York senator yet, but only First Lady, yet she used her position to go to conferences, such as this conference, and speak out for women’s rights, as they are the same as human

The Perils Of Indifference Speech Similarities And Differences

Comparison Between On the Right of Women to Vote and the Perils of Indifference Speeches “On the Right of Women to Vote by Suzan B. Anthony and “The Perils of Indifference” by Elie Wiesel are among the most popular and significant speeches in the United States of America. Suzan B. Anthony made this speech in 1872 when she was accused to vote illegally. Elie Wiesel made his speech in 1999 where he was invited as intellectual to participate in Millennium Lecture Series. Although these speeches have some apparent similarities, the differences between them are also remarkable.

Rhetorical Analysis Of Susan B. Anthony's Speech

For a very long time, the voting rights of the citizens have been a problem in the US. It started out with only men with land being able to vote, and then expanded to white men, and then to all men. However, women were never in the situation, they were disregarded and believed to not be worthy enough to have the same rights as men. They were essentially being treated as property, therefore having no rights. But, in Susan B. Anthony’s speech, she hits upon the point that women are just as righteous as men.

Rhetorical Analysis Of Hillary Clinton Speech On Women's Rights

Hillary Rodham Clinton delivered her speech “Women’s Rights are Human Rights” September 5, 1995 while speaking at the United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing, China with the intent to educate and spread awareness in regards to the rights and treatment of women around the world, while encouraging women to take initiative and highlight the potential women have if presented with the opportunity of equality. Early in Clinton’s speech, she uses the power of ethos to establish her credibility and continues to build upon it throughout, bringing attention to the fact she has had years of experience fighting for change among people of all kinds. Clinton convinces listeners that she has made women’s rights a priority in her life

Susan B Anthony On Women's Right To Vote Analysis

Susan B. Anthony, a woman who was arrested for illegally voting in the president election of 1872, in her “On Women's Right to Vote” speech, argues that women deserve to be treated as citizens of America and be able to vote and have all the rights that white males in America have. She begins by introducing her purpose, then provides evidence of how women are citizens of America, not just males by using the preamble of the Constitution, then goes on about the how this problem has became a big problem and occurs in every home in the nation, and finally states that women deserve rights because the discrimination against them is not valid because the laws and constitutions give rights to every CITIZEN in America. Anthony purpose is to make the woman of America realize that the treatment and limitations that hold them back are not correct because they are citizens and they deserve to be treated like one. She adopts a expressive and confident tone to encourage and light the hearts of American woman. To make her speech effective, she incorporates ethos in her speech to support her claims and reasons.

More about Susan B Anthony Women's Right To Vote Essay

Susan B. Anthony Essay

Susan B. Anthony Susan Brownell Anthony was a magnificent women who devoted most of her life to gain the right for women to vote. She traveled the United States by stage coach, wagon, and train giving many speeches, up to 75 to 100 a year, for 45 years. She went as far as writing a newspaper, the Revolution, and casting a ballot, despite it being illegal. Susan B. Anthony was born on February 15, 1820, in Adams, Massachusetts. She was the second of eight children in her family. In the early 1800's girls were not allowed an education. Susan's father, Daniel, believed in equal treatment for boys and girls and allowed her to receive her education from a private boarding school in Philadelphia. At the age of seven her …show more content…

During the Civil War, in 1863, Susan founded the Women's Loyal League, which fought for the freeing of slaves. Susan's work for women's rights began when she met a mother of young children by the name of Elizabeth Cady Stanton in 1851. The two women worked on reforming New York state laws discriminating women. Susan organized state campaigns for legal reforms and delivered speeches written by Stanton. Elizabeth and Susan organized the National Women Suffrage Association and worked hard for a constitutional amendment giving women the right to vote. Even though the 15th amendment allowed newly freed slaves to vote, women of any race still could not vote. For ten years, Susan and Elizabeth wrote their newspaper, the Revolution, focusing on the injustices suffered by women. In the 1872 presidential election, Susan decided to register and cast a ballot to protest for women's rights. She was arrested, convicted, and refused to pay the one hundred dollar fine. Susan Anthony went to Europe in 1883, to meet other women's rights activists. Later, in 1888, she helped form the International American Council of Women, which represented 48 countries. At the age of eighty, Susan B. Anthony resigned as president of the National American Women Suffrage Association, but continued to be a speaker at the conventions until she died in Rochester, New York, on March 13, 1906. In

How Did Women's Suffrage Change In America

“It took 400 years after the declaration of independence was signed and 50 years after black men were given voting rights before women were treated as full American citizens and able to vote.” A women named Susan B. Anthony was one of those women struggling to be the same as mankind. Susan B. Anthony worked helped form women’s way to the 19th amendment. Anthony was denied an opportunity to speak at a convention because she was a woman. She then realized that no one would take females seriously unless they had the right to vote. Soon after that she became the founder of the National Woman Suffrage Association in 1869. In 1872, she voted in the presidential election illegally and then arrested with a hundred dollar fine she never paid.” I declare to you that woman must not depend upon the protection of man, but must be taught to protect herself, and there I take my stand.”(Anthony) When Susan B. Anthony died on March 13, 1906, women still didn’t have the right to vote. 14 years after her death, the 19th amendment was passed. In honor of Anthony her portrait was put on one dollar coins in

Summary Of Susan B Anthony Statement At The Closing Of Her Trial

Susan B. Anthony was born on February 15, 1820 in Adams, Massachusetts. Susan became a pioneer crusader for the woman suffrage movement in the United States and eventually became the president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Susan B. Anthony’s work helped lay the foundation for the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution, giving women the right to vote. Susan B. Anthony, a teacher and abolitionist, was found guilty of voting. This was a federal crime in the United States of America. In 1873, at Susan’s B. Anthony's trial in Canandaigua, Judge Hunt set many roadblocks in her trial. For example, he refused to allow Susan to testify on her own behalf, allowed

How Did Susan B Anthony Change Society

She was arrested and fined, but she ended up never paying the fine. Then finally, 14 years after she died, women had the right to vote. Even before Susan was born, her family was already a part of politics. Growing up, her parents had strong beliefs against slavery,

Susan B Anthony Research Paper

Anthony was tireless in her efforts, she even took matters into her own hands in 1872, when she had voted illegally in the presidential election. Susan was then arrested for the crime, she unsuccessfully fought the charges; she was fined $100, which she never paid. Even in her last years, Antony never gave up on her fight for Women's Suffrage. In 1905, she met with president

How Did Susan B Anthony Use The Word 'We'?

Susan Brownell Anthony was one of the most famous women’s suffrage activists in America. Anthony was born in 1820 in Massachusetts and raised by Quaker tradition her whole life. She moved around from New York to Philadelphia with her family when she was growing up, but eventually settled her family in Rochester, New York after taking a position in the Quaker seminary in 1839 (“Susan B. Anthony). She began teaching at a female academy from 1846-1849 (“Susan B. Anthony”). With the help of Elizabeth Stanton, Anthony became involved with women’s rights in 1852 where she organized the Women’s New York State Temperance Society (“Susan B. Anthony”).

What Is Susan B Anthony Violation Of Women's Rights

Susan B. Anthony was the ultimate leader in the woman's suffrage movement. She was so famous because she was one of the first true women's rights activists. At her first woman's rights convention in 1852, she declared "that the right which woman needed above every other, the one indeed which would secure to her all the others, was the right of suffrage." She then led several rallies and marches to encourage women's right to vote. On November 5th 1872, Anthony cast a vote in the Presidential election which she had previously registered to vote on November 1, 1872 at a local barbershop, along with her three sisters. Even though the inspectors refused her initial demand to register, Anthony used her power of persuasive speaking and her relationship with Judge Henry R. Selden to obtain her registration. However, she was arrested for her illegal action violating the voting law two weeks later.

Susan B. Anthony and the Fight For Equality Essay

Susan was born in 1820 in New England, she was born into a Quaker family, which Cenegage learning states that her religious background and upbringing played a crucial role in her impact on woman's suffrage, and her eventual discontent with christianity in America. The Quakers, who believe in equality and an “inner light” within everyone, instilled the idea into Susan that equality was essential, which could predict her future role in things such as the women’s rights movement, abolitionist movement, and the temperance movement. As Susan moved through her life she partook in many movements, but also switched religions three times, from Quaker, Unitarianism, and eventually and agonistic.

Biography Of Susan B. Anthony

She was born on February 15, 1820 in the city of Adams in Massachusetts. Susan was raised in a Quaker family with long activist traditions. Once Susan and her family moved to Rochester in 1845, lots of her family members and her were very involved in the anti-slavery movement.

Women 's Suffrage By Susan B. Anthony Essay

Susan B. Anthony played a huge role in the woman 's suffrage, she had traveled around the country to give speeches, circulate petitions, and organize local woman 's rights organization. Her family moved to Rochester, New York in 1845 and they became active in the antislavery movement. The antislavery Quakers met at their farm almost every Sunday, where Fredrick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison sometimes joined. Susan was working as a teacher and became involved in the teacher 's union when she discovered that male teachers had a monthly salary of S10.00, while the female teachers earned $2.50 a month. Her sister and parents both attended the 1848 Rochester Woman 's Rights Convention held on August 2. Her experience with the teacher 's union, antislavery, and Quaker upbringing, made her realize that it was time for a career in woman 's rights reform to grow.

Susan Byj.b Anthony : The Second Child Of 8

Susan Brownell Anthony was born on February 15, 1820 in Adams, Massachusetts. Anthony was the second child of 8. During the time of Susan’s upbringing females were not allowed an education, however Susan’s father, Daniel who was a liberal Quaker, believed different. Daniel believed in equal treatment for boys and girls and he allowed her to receive an education at a home school in which was established by her father and she was later enrolled in a female seminary, a Quaker boarding school in Philadelphia. Susan became a teacher however she soon became tired of that and moved with her family to Rochester, New York to help run the family farm and this is where Susan’s lifelong career in reform began. Susan B. Anthony was a significant woman who devoted her life to abolish slavery, implement stricter laws on liquor and fought for a woman’s right to vote and stand for electoral office. She would travel the United States via stage coach, wagon and the train and she would give speeches hoping to influence and expand the knowledge of those in America on these certain topics. In her life she had written a newspaper titled the revolution and she even went as far as casting a ballot which at the time was illegal and she was put on trial for this.

What Role Did Lucy Stone And Gage Play In The Women's Rights Movement

Susan B. Anthony was born on february 15 1820 and she was born into a politically active family. They worked to end slavery she then realized that politicians did not take women seriously. So when she was involved in the women’s rights movement she was voted president of the rights activist. She also founded the national woman's suffrage association.

Susan B. Anthony's Role In Civil Disobedience

Anthony’s role in civil disobedience, one must first have knowledge of his her personal life. Susan Browned Anthony was born February 15, 1820, in Adams, Massachusetts. Susan was born and raised in a Quaker family, which is a highly strict religion. Anthony was the second oldest of eight including her sibling who had passed early on in life (Susan). Anthony’s father was a owner of a cotton mill, also he was a very devoted religious person, and taught his children good moral values, such as loving and helping others. Later on while Anthony was you she attended a boarding school in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1837 After attending boarding school, she began work as a teacher after her family became in debt and we forced to sell their cotton mill business and move to Rochester, New York (Susan

Susan B. Anthony: Women's Suffrage Movement

Susan B. Anthony was famous for dedicating her time to the women's right movement. She made

Who Is Susan B Anthony's Activist

Susan B. Anthony is one of the first ever recorded women’s activist. She was a constant participant in a small group with other local Women’s activists which included others like Elizabeth Stanton and Carrie Chapman Catt. This “miniature” group would soon expand massively over the country and soon, Susan would become leader.

Susan B. Anthony: Women's Rights Activist

People know Susan B. Anthony as one of the leading women's suffrage activist but how did who was she before the fame? How did she get inspired to take action and give women a voice? Anthony’s full name is Susan Brownell Anthony. She was born on February 15th 1820 in Adams Massachusetts [Women's Hall of Fame]. Her family lived on a cotton farm which failed in the early 1830’s which caused them to move to Rochester, New York. In the 1840’s Anthony found work being a teacher in the “Abolition State” of New York. Living in New York inspired Anthony to want to share her opinion with others. Anthony eventually met Elizabeth Stanton and they worked together on many occasions. Unfortunately people would not listen to Anthony’s

Related Topics

- Boarding school

- Women suffrage

- Temperance movement

- Brownell anthony

- Constitutional amendment

- Skip to global NPS navigation

- Skip to the main content

- Skip to the footer section

Exiting nps.gov

Learning from susan b. anthony.

These activities were researched and written by Alison Russell a NCPE intern with the Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education. Susan B. Anthony is one of the most recognizable suffragists. She was born in Adams, Massachusetts in 1820. Her family moved to Rochester, New York in 1845 where she lived and worked for most of her life. Her family participated in the anti-slavery and early women’s rights movements. Their work introduced Anthony to activism as a young woman. She met Lucy Ston e and Elizabeth Cady Stanton in the 1850s. In 1868, Anthony and Stanton founded the American Equal Rights Association and edited The Revolution, a women’s rights newspaper.

The debate over the Fifteen th Amendment, which granted voting rights to African American men but not women, caused Anthony and Stanton to split from other suffragists and allies , basing their objections on racist assumptions. They formed the National Women Suffrage Association to focus on women’s right to vote. Anthony and her sisters voted in the 1872 and were arrested. In the 1880s, Anthony, Stanton, and Matilda Josyln Gage wrote “The History of Woman Suffrage.” While it detailed white women’s contributions, women of color’s efforts were not included.

Anthony traveled and fought tirelessly for women’s right to vote. She was an accomplished speaker and organizer. Susan B. Anthony died in 1906 in her home in Rochester. The Nineteenth Amendment , named the Susan B. Anthony Amendment in her honor, was ratified in 1920. You can find out more about Anthony by visiting this article about her and by exploring the Places of Susan B. Anthony .

Identify rights and privileges protected for all citizens of the United States and evaluate voting as a privilege.

Connect the actions of a historical figure to the ways we see and remember them.

Create images and memorials using different symbols, composition, or action based on the message you are trying to convey.

Inquiry Question

What is a cause worth dedicating your life to? Is there a cause that is more important than all the others?

Activity 1: What are the Rights in Equal Rights?

Susan B. Anthony was arrested for trying to vote in 1872. In court, she argued the Fourteenth Amendment guaranteed rights to all citizens. Therefore, as a natural-born citizen, she was within her rights to vote. The Fourteenth Amendment says that “All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States.” It continues, “No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens.”

What does the Fourteenth Amendment guarantee? Make a list of what “privileges” you think are guaranteed to citizens of the United States. Where does voting fit? Do you agree with Anthony’s characterization in this 1872 speech:

“Is the right to vote one of the privileges or immunities of citizens? I think the disfranchised ex-rebels, and the ex-state prisoners will agree with me, that it is not only one of them, but the one without which all others are nothing. Seek the first kingdom of the ballot, and all things else shall be given thee, is the political injunction…. To be a person was to be a citizen, and to be a citizen was to be a voter.”1

Since Anthony’s argument, the Supreme Court has listed some but not all privileges protected by the Fourteenth Amendment. These include access to the seats of government and courts, access to seaports, protection abroad, the right of assembly, to access public lands, to pass from state to state, and to vote for national officers, among others. Is it a good idea to have a list of what counts as a privilege? Are there any disadvantages to listing them? Are there any that you would add to the list?

Voting is still not guaranteed to all citizens. The Fifteenth, Nineteenth, Twenty- Third and Twenty- Sixth Amendments have helped expand voting, but as of 2020 only 66% of eligible Americans are registered to vote.2 Other Americans aren’t even eligible because of age, geographic location or former incarcerated status. How do you think Anthony would view this access to the ballot? How do you? Do you think their should be restrictions or limitations on access to voting? Do you think more people should be able to vote? Why?

To learn more about the interpretation of the Privileges and Immunities Clause Check out these essays from the National Constitution Center.

Activity 2: Symbols of Memory

Ratified fourteen years after her death, the Nineteenth Amendment extended the right to vote to women. Lawmakers and activists called it the Susan B. Anthony Amendment in her honor. In recent years, voters have left “I Voted” stickers on Anthony’s grave as a tribute. Anthony was also the first woman to appear on U.S. currency. Her portrait appeared on the dollar coin from 1971 to 1981 and in 1999.

Commemorating a historical figure doesn’t just have to come in the form of a statue, or even an official action. What’s important is to make a connection with that historical figure and why they are important you. Think about a person who fought for progress you benefit from directly or indirectly. What’s one thing you can do to show you appreciate the work of a person in history? Is there an action you can take? Is there an art form (painting, song, poem) that you could dedicate to them? Is there a group or organization that does work that honors the person you are celebrating? Can you volunteer or do something to support your shared mission?

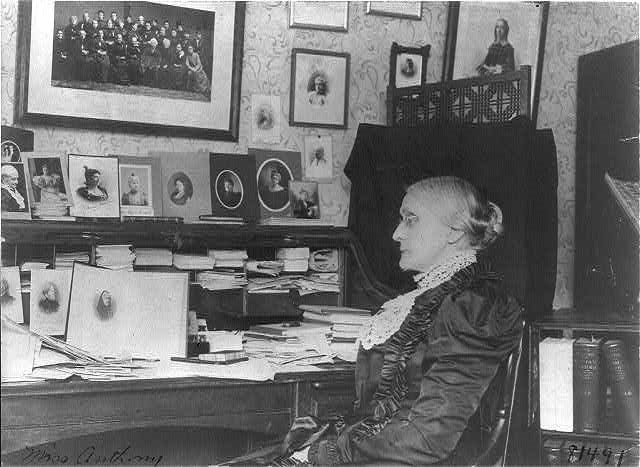

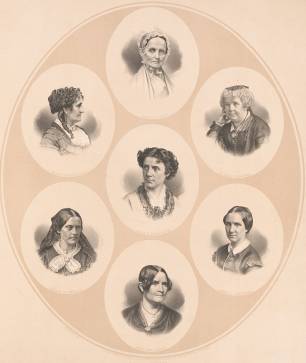

Activity 3: A Picture’s worth a thousand words

Susan B. Anthony co-wrote a history of women’s suffrage, focused on the efforts of white women. She oversaw the images for the book. She wanted the portraits of women to counter the negative stereotypes of suffragists in popular media. Borrowing strategies from anti-slavery reformers, Anthony wrote and gave specific instructions on pose, dress and setting to featured women . It is Anthony herself who has become one of the most recognizable suffragists. Look at her picture in “The History of Woman Suffrage.” What message do you think she is trying to send with her pose, facial expression and dress? Forty-five years after the image and twenty years after the publication of the book, Anthony sat for a new portrait. How is this one different? What parts of the picture stand out to you? What message do you think this is trying to convey to the viewer?

Susan B. Anthony, c. 1855.

From "The History of Woman Suffrage" by Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Volume 1, 1881.

Susan B. Anthony seated at her desk, 1900. Collections of the Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2016651849/).

Think about how different pictures of the same person can say or do different things. Take photos with your friends or family members. Try to convey serious, funny, inspiring, and other emotions. How do you change the person’s pose, the framing of the photograph or even what accessories they use to create the mood? What does the picture tell a viewer about that person? What does it hide?

Part of a series of articles titled Curiosity Kit: Susan B. Anthony .

Next: Places of Susan B. Anthony

You Might Also Like

- women’s history

- women’s rights

- women’s suffrage

- 19th amendment

- susan b. anthony

- teaching with historic places

- educational activity

- curiosity kit

Last updated: August 9, 2021