- Advanced search

Deposit your research

- Open Access

- About UCL Discovery

- UCL Discovery Plus

- REF and open access

- UCL e-theses guidelines

- Notices and policies

UCL Discovery download statistics are currently being regenerated.

We estimate that this process will complete on or before Mon 06-Jul-2020. Until then, reported statistics will be incomplete.

Improving The Diagnosis And Risk Stratification Of Prostate Cancer

The current diagnostic and stratification pathway for prostate cancer has led to over-diagnosis and over- treatment. This thesis aims to improve the prostate cancer diagnosis pathway by developing a minimally invasive blood test to inform diagnosis alongside mpMRI and to understand the true Gleason 4 burden which will help better stratify disease and guide clinicians in treatment planning. To reduce the number of patients who have to undergo prostate biopsy after indeterminate or false positive prostate mpMRI, we aimed to develop a new panel of mRNA detectable in blood or urine that was able to improve the detection of clinical significant prostate cancer (Gleason 4+3 or ≥6mm) in combination with prostate mpMRI. mRNA expression of 28 potential genes was studied in four prostate cancer cell lines and, using publicly available datasets, a new seven gene biomarker panel was developed using machine learning techniques. The signature was then validated in blood and urine samples from the ProMPT, PROMIS and INNOVATE trials. To redefine the classification of Gleason 4 disease in prostate cancer patients, digital pathology was used to contour and accurately assess the burden and spread of Gleason 4 in a cohort of PROMIS patients compared to the gold standard manual pathology. There was a significant difference between observed and objective Gleason 4 burden that has implications in patient risk stratification and biomarker discovery. The work presented in this thesis makes a significant step toward improving the patient diagnostic and risk classification pathways by ensuring only the right patients are biopsied when necessary, improving the current pathological reference standard.

Archive Staff Only

- Freedom of Information

- Accessibility

- Advanced Search

- Original Research

- Open access

- Published: 07 November 2020

Assessment of knowledge, practice and attitude towards prostate cancer screening among male patients aged 40 years and above at Kitwe Teaching Hospital, Zambia

- Sakala Gift ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0438-6804 1 ,

- Kasongo Nancy 2 &

- Mwanakasale Victor 1

African Journal of Urology volume 26 , Article number: 70 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

9244 Accesses

5 Citations

Metrics details

Prostate cancer is a leading cause of cancer death in men. Evaluating knowledge, practice and attitudes towards the condition is important to identify key areas where interventions can be instituted.

This was a hospital-based descriptive cross-sectional study aimed at assessing knowledge, practice and attitude towards prostate cancer screening among male patients aged 40 years and above at Kitwe Teaching Hospital, Zambia.

A total of 200 men took part in the study (response rate = 100%). Of the 200 respondents, 67 (33.5%) had heard about prostate cancer and 58 (29%) expressed knowledge of prostate cancer out of which 37 (63.8%) had low knowledge. Twenty-six participants (13%) were screened for prostate cancer in the last 2 years. 98.5% of the participants had a positive attitude towards prostate cancer screening. Binary logistic regression results showed that advanced age ( p = 0.017), having secondary or tertiary education ( p = 0.041), increased knowledge ( p = 0.023) and family history of cancer ( p = 0.003) increased prostate cancer screening practice. After multivariate analysis, participants with increased knowledge ( p = 0.001) and family history of cancer ( p = 0.002) were more likely to practice prostate cancer screening.

The study revealed low knowledge of prostate cancer, low prostate cancer screening practice and positive attitude of men towards prostate cancer screening. These findings indicate a need for increased public sensitization campaigns on prostate cancer and its screening tests to improve public understanding about the disease with the aim of early detection.

1 Background

Prostate cancer, or adenocarcinoma of the prostate as it is called in some settings, can be described as cancer of the prostate gland.

The prostate is a small fibromuscular accessory gland of male reproductive system weighing about 20 g. It is located posterior to the pubic symphysis, superior to the perineal membrane, inferior to the bladder and anterior to the rectum. It produces and secretes proteolytic enzymes into semen, to facilitate fertilization [ 1 , 2 ].

Prostate cancer is characterized by both physical and psychological symptoms [ 3 ]. Early-stage prostate cancer is usually asymptomatic [ 4 ]. More advanced disease has similar symptoms with benign prostate conditions such as weak or interrupted urine flow, hesitancy, frequency, nocturia, hematuria or dysuria. Late-stage prostate cancer commonly spreads to bones and cause pain in the hips, spine or ribs [ 4 ]. The 2 commonly used screening methods for prostate cancer are digital rectal examination (DRE) and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test.

Prostate cancer is one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths among males globally [ 4 ]. The 2018 Global Cancer Project (GLOBOCAN) report estimated 1 276 106 new cases in 2018, representing 7.1% of all cancers worldwide [ 5 ]. The report further estimated the number of deaths due to prostate cancer at 358 989, representing 3.8% of all cancers globally. It was thus ranked the second most common cancer and the fifth leading cause of cancer death in men. The American Cancer Society 2019 report showed that an estimated 174,650 new cases of prostate cancer would be diagnosed in the USA during 2019 [ 4 ]. The report further stated that an estimated 31,620 deaths from prostate cancer would occur in 2019. It further put the incidence of prostate cancer to about 60% higher in blacks than in whites suggesting a genetic predilection to the cancer.

Africa is no exception to this global trend of high incidence and mortality of prostate cancer with age-standardized incidence and mortality rates of 26.6 and 14.6 per 100 000 men, respectively [ 5 ]. This placed prostate cancer as the third most common cancer among both sexes and the fourth leading cause of all cancer deaths among both sexes in the region. Current statistics on Zambia indicate that Zambia has one of the world’s highest estimated mortality rates from prostate cancer [ 6 , 7 ]. The age standardized incidence and mortality rates from prostate cancer are at 45.6 and 28.4 per 100,000 men, respectively [ 5 ].

Although the causes of prostate cancer are not yet fully understood, it is thought that advanced age (above 50 years), positive family history of prostate cancer and an African-American ethnic background are risk factors [ 4 , 8 ].

In mitigating the effects of diseases like prostate cancer, evaluating knowledge, practice and attitudes towards the condition is important to identify key areas where interventions can be instituted. For instance, studies in other countries that accessed these factors were able to identify the role that health workers and political will could play in increasing knowledge and screening for prostate cancer [ 8 , 9 , 10 ]. Furthermore, low level of awareness about prostate cancer or the complete lack of it has been identified as the cause of late presentation and poor prognosis [ 11 , 12 ].

Despite Zambia having one of the world’s highest estimated mortality rates from prostate cancer [ 6 , 7 ] coupled with an increased suggested genetic predilection to the cancer [ 4 ], since the majority of the male population are black, no studies assessing knowledge, practice and attitude towards prostate cancer screening have been done. This study therefore sought to address the gap.

The aims of the study were to determine the knowledge, practice and attitude towards prostate cancer screening at Kitwe Teaching Hospital (KTH). In addition, the study also aimed to determine the association between demographics of participants and knowledge, knowledge of participants and attitude towards prostate cancer screening, knowledge of participants and prostate cancer screening practice as well as attitude of participants towards prostate cancer screening and prostate cancer screening practice.

2.2 Study site and design

The study was done at KTH in the Copperbelt province of Zambia. It is a tertiary referral hospital in the region whose catchment area includes Copperbelt, Luapula and North-western provinces. It has a bed capacity of 630 [ 13 ].

This was a descriptive cross-sectional study of knowledge, practice and attitude towards prostate cancer screening among male patients aged 40 years and above at KTH. The study design was chosen because it is simple to use, cost-effective and time economic.

2.3 Study participants

The sample size was ascertained using the ‘Stalcalc’ function of Epi Info Version 7.1.5. In a month, nearly 419 male patients presented to the target areas for this study at KTH, namely Out-Patient Department (OPD), medical and surgical admission wards. Since data for this study were collected in 1 month, 419 was used as the total population size. A confidence level was 95% and a confidence limit was 5% (at 95% confidence level) and the expected frequency was 50%. Therefore, a sample size of 200 was calculated for this study. Study participants were randomly selected from target areas. All consenting male patients aged 40 years and above in the target areas for this study at KTH were enrolled until the targeted sample size was reached. Male patients aged less than 40 years and participants who did not give consent were excluded from the study.

2.4 Study duration

The study was done in a period of 6 months from April to September 2019.

2.5 Data collection and analysis

The study objectives were explained to participants, and written and informed consent was obtained. Participants were enrolled utilizing a well-structured questionnaire as shown in “Appendix”. The questionnaire collected demographic information including age, marital status, education and occupation. It also collected data on family history of cancer as well as knowledge, practice and attitudes towards prostate cancer screening. Translations to the questionnaire were done from English to a suitable local language according to the participant’s preference. The responses were recorded as given by the participants.

Data collected during the study were checked for completeness and double-entered into the Epi Info version 7 software. Frequency tables and graphs were generated for relevant variables. The data were analysed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23. For comparing associations between variables, Pearson Chi-square test was performed. A p value of equal or less than 0.05 was considered significant. Binary logistic regression, as well as multivariate analysis, was done. Low knowledge was defined as scoring 1–3 correct responses in the knowledge section, moderate knowledge as scoring 4–6 correct responses and high knowledge as scoring 7–9. Positive attitude was defined as scoring 2 or more correct responses in the section assessing attitudes, while negative was defined as scoring less than 2 correct responses. Practice was assessed with a closed-ended question in the practice section.

A total of 200 participants were enrolled.

3.1 Background characteristics

As illustrated in Table 1 , more than half, 149 (74.5%), of the participants in the study were in the 40–60 years age range. All participants were Christians, 161 (80.5%) had no formal education or had primary education, and 198 (99%) were in informal employment or unemployed.

3.2 Knowledge of prostate cancer

Of the 200 participants enrolled, 67 (33.5%) had heard about prostate cancer, while 133 (66.5%) had never heard about it. Majority, 55.3%, of the participants who had had heard about prostate cancer pointed to a doctor or nurse as a source of information as shown in Table 2 .

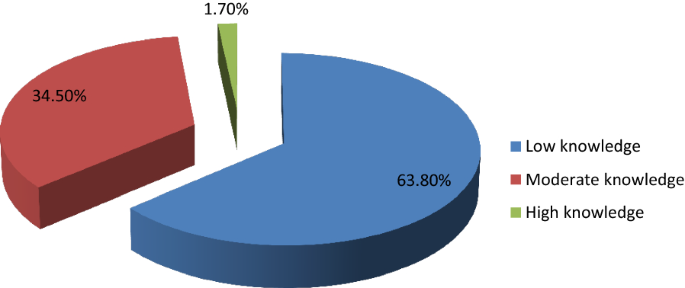

Of the 200 participants enrolled in the study, 58 (29%) expressed knowledge on prostate cancer. Among participants who had knowledge, majority of them, 37 (63.8%) had low knowledge as shown in Fig. 1 .

Levels of knowledge

Participants who had secondary school or tertiary education were more knowledgeable about prostate cancer than those who did not have ( p < 0.001). Participants who had heard about prostate cancer were more knowledgeable than those who had not ( p < 0.001). Participants who had heard about prostate cancer had high levels of knowledge compared to those who had not ( p = 0.009). Participants older than 60 years had more knowledge on prostate cancer compared with those below 60 years ( p = 0.026).

3.3 Practice of prostate cancer screening

Of the 200 participants, only 26 (13%) had been screened in the last 2 years. Among participants who had screened, 20 (76.9%) pointed out DRE as the method used, while 3 (11.5%) pointed out PSA, 2 (7.69%) reported both DRE and PSA, and 1 (3.85%) did not know which screening method was used. Among the 26 participants that had screened in the last 2 years, 18 (69.2%) had a positive prostate cancer outcome, while 8 (30.8%) had a negative prostate cancer outcome. 199 (99.5%) of the participants expressed intentions to screen in future.

Age above 60 years was associated with a positive prostate cancer outcome ( p = 0.002). The study also found that participants who were knowledgeable about prostate cancer were more likely to undergo prostate cancer screening ( p < 0.001) and that high level of knowledge was associated with prostate cancer screening practice ( p = 0.024). Increasing age of participants (over 60) was also associated with prostate cancer screening practice in the last 2 years ( p < 0.001).

3.4 Attitude towards prostate cancer screening

Among 200 participants enrolled in the study, 197 (98.5%) had a positive attitude towards prostate cancer screening, while 3 (1.5%) had a negative attitude. There were no statistically significant associations between age and attitude towards prostate cancer screening ( p = 0.099), knowledge and attitude towards prostate cancer screening ( p = 0.868) as well as between practice in the last 2 years and attitude towards prostate cancer screening ( p = 0.291).

3.5 Factors affecting prostate cancer screening practice

Binary logistic regression analysis was performed to identify factors that affect prostate cancer screening. As shown in Table 3 , prostate cancer screening practice was associated with age ( p = 0.017), education ( p = 0.041), knowledge ( p = 0.023) and family history of cancer ( p = 0.003).

All factors that were significant in binary logistic analysis (with p < 0.05) were analysed using multivariate logistic regression. A backward step-by-step elimination method was employed to manually eliminate factors with insignificant p values. As illustrated in Table 4 , only two factors remained statistically significant, namely knowledge and family history of cancer. Participants who had knowledge about prostate cancer were nearly 11 times more likely to practice prostate cancer screening than those who did not have ( p = 0.001). Participants who had a family history of cancer were 26 times more likely to practice prostate cancer screening than those who had a negative family history of cancer ( p = 0.002).

4 Discussion

The study targeted male patients aged 40 years and above due to available literature which indicates that prostate cancer screening should start at 40 years [ 4 , 14 ]. Literature indicates that the average age of a man to be diagnosed with prostate cancer is about 66 years and above [ 4 , 15 ]. Since the majority of the participants in the study, 149 (74.5%), were in the 40–60 years age group, as also observed by Mofolo and colleagues in their study [ 16 ], there was an over representation of participants at the lowest risk of prostate cancer.

The study found low levels of awareness and knowledge. This is similar to findings of other studies done in other countries [ 10 , 17 ]. This implies that there is little sensitization being done to the public and expresses the need for more public sensitization campaigns utilizing both electronic and print media with the aim of early detection and treatment to improve the prognosis [ 7 , 8 , 11 ]. However, other studies found high levels of awareness [ 9 , 18 , 19 , 20 ]. Of the studies that found high levels of knowledge, one of them was done on a group of public servants who were educated, had good access to health information and this was not a reflection of the general population who are mostly uneducated [ 9 ]. The study also demonstrated that majority of the participants who were knowledgeable about prostate cancer had low level of knowledge which was consistent with findings by other studies [ 10 , 18 , 19 , 21 , 22 , 23 ]. This indicates a need for comprehensive knowledge on prostate cancer to promote early detection.

Participants with higher level of education were more knowledgeable about prostate cancer than those who had lower level of education or no formal education at all consistent with findings by similar studies done in other countries [ 16 , 17 , 21 , 24 ]. However, some studies done in Nigeria and Kenya in 2018 did not find such an association [ 10 , 19 ]. In one of the studies that did not find an association between higher education and knowledge, the sample was drawn from a rural part of the country with more than 60% having no formal education or had primary education [ 19 ]. This could have resulted in the finding.

Participants older than 60 years had more knowledge on prostate cancer than those below 60 years as also demonstrated by Adibe et al. [ 24 ]. This highlights a possible bias that might be present in the provision of information on prostate cancer where individuals who are at an advanced age are educated about it because of their increased risk. It could also indicate the natural history of how older patients are more likely to have information about prostate cancer as they visit healthcare centres for urologic problems like benign prostate hyperplasia which are quiet frequent [ 4 , 15 ].

In addition to health workers contributing to the increase in knowledge of prostate cancer, utilizing media platforms that are widely accessible such as radio presents a great opportunity to achieve this. A 2018 study by Kinyao and Kishoyian which assessed attitudes, perceived risk and intention in a rural county found that over 60% of the participants learnt about prostate cancer from the radio [ 19 ]. This shows how much more applicable this media platform can be in developing regions like Africa.

The low level of prostate cancer screening practice demonstrated in the study is consistent with findings from similar studies [ 10 , 11 , 19 , 21 , 25 ] though majority of participants in this study were willing to be screened after discussing about the condition with them consistent with a study done in Kenya [ 21 ]. However, it is inconclusive whether increased knowledge would increase screening as other factors apart from knowledge on prostate cancer appear to influence this practice. A similar study by Kinyao and Kishoyian in 2018 found that many participants had strong fatalistic attitudes towards screening such as “if I am meant to get prostate cancer, I will get it” and these appeared to influence screening [ 19 ]. Thus in sharing information on prostate cancer, cultural beliefs and fatalistic attitudes must also be addressed.

DRE was the most commonly used method of prostate cancer screening contrary to findings by similar studies done in Nigeria that found PSA to be the most commonly used method [ 24 , 25 ]. This suggests a possible cost barrier to utilization of the PSA screening method in our sample.

The finding demonstrated in the study that participants were more likely to screen for prostate cancer if they were older than 60 years is consistent with findings of similar studies done in Uganda and Nigeria [ 11 , 25 ]. This implies that there is a risk of late presentation and consequently poor prognosis. As such, intensified public sensitization campaigns are needed to attain early detection and treatment as well as good prognosis. Participants who were more educated were more likely to undergo prostate cancer screening consistent with findings from a Nigerian study [ 25 ]. The statistically significant association between knowledge on prostate cancer and prostate cancer screening practice is consistent with other similar studies done [ 10 , 11 , 21 ]. This is another indication of the need to intensify prostate cancer sensitization campaigns.

The high positive attitude level demonstrated in the study was similar to findings from other studies done [ 9 , 23 , 24 ]. However, a Ugandan study found a negative attitude towards prostate cancer screening [ 11 ]. This could be because the study explored other factors under attitude that our study did not. The lack of any statistically significant association between age of participants and attitude towards prostate cancer screening concurs with findings from a study done in Uganda [ 11 ]. However, a 2017 study done in Nigeria found an association between age and attitude [ 24 ].

5 Limitations of Study

Generalizability of findings of this study must be done with caution since this was a hospital-based study. There is thus a need for more studies to be done in other institutions such as universities and colleges, urban and rural communities, district, general, central and other teaching hospitals to have comprehensive knowledge. In addition, certain aspects of knowledge were not assessed, for example, that prostate cancer can present without symptoms. As such, the study findings were limited to comparisons with studies that also did not assess the asymptomatic presentation of prostate cancer.

6 Conclusion

The study revealed low knowledge of prostate cancer, low prostate cancer screening practice and positive attitude of men towards prostate cancer screening. Practice of prostate cancer screening was associated with age, education level, knowledge and family history of cancer.

Being the first study to assess knowledge, practice and attitude towards prostate cancer screening in Zambia, it has bridged the knowledge gap and has also provided valuable information for healthcare intervention.

Availability of data and material

Data used in the study is available in additional file 1 captioned ‘Dataset for AFJU-D-19-00041R2 manuscript’ and authors agree to share it.

Abbreviations

- Digital rectal examination

- Prostate-specific antigen

Out-Patient Department

Tropical Diseases Research Centre

National Health Research Authority

Kitwe Teaching Hospital

Global Cancer Project

Blandy J, Kaisary A (2009) Lecture notes urology, 6th edn. Wiley, Hoboken

Google Scholar

Shenoy KR, Shenoy A (2019) Manipal manual of surgery, 4th edn. CBS Publishers Pvt Ltd., Shenoy Nagar

Desousa A, Sonavane S, Mehta J (2012) Psychological aspects of prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Dis 15(2):120–127

Article CAS Google Scholar

American Cancer Society (2019) Cancer facts and figures, 2019. American Cancer Society, Atlanta

GloboCan (2018). http://globocan.iarc.fr

GloboCan (2012). http://globocan.iarc.fr

National Cancer Control Strategic Plan 2016–2021. Ministry of Health Zambia

So WK, Choi KC, Tang WP, Lee PC, Shiu AT, Ho SS et al (2014) Uptake of prostate cancer screening and associated factors among Chinese men aged 50 or more: a population-based survey. Cancer Biol Med 11(1):56–63

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Oranusi CK, Mbieri UT, Oranusi IO, Nwofor AME (2012) Prostate cancer awareness and screening among male public servants in Anambra State Nigeria. Afr J Urol 18(2):72–74

Article Google Scholar

Awosan KJ, Yunusa EU, Agwu NP, Taofiq S (2018) Knowledge of prostate cancer and screening practices among men in Sokoto, Nigeria. Asian J Med Sci 9(6):51–56

Nakandi H, Kirabo M, Semugabo C, Kittengo A, Kitayimbwa P, Kalungi S, Maena J (2013) Knowledge, attitudes and practices of Ugandan men regarding prostate cancer. Afr J Urol 19(4):165–170

Ito K (2014) Prostate cancer in Asian men. Nat Rev Urol 11:197

Sichula M, Kabelenga E, Mwanakasale V (2018) Factors influencing malnutrition among under five children at Kitwe Teaching Hospital, Zambia. Int J Curr Innov in Adv Res 1(7):9–18

Canadian National Institute of Health (2013)

Cancer Diseases Hospital (2013) Annual report

Mofolo N, Betshu O, Kenna O, Koroma S, Lebeko T, Claassen FM, Joubert Gina (2015) Knowledge of prostate cancer among males attending a Urology clinic, a South African study. SpringerPlus 4:67

Kabore FA, Kambou T, Zango B, Ouédraogo A (2014) Knowledge and awareness of prostate cancer among the general public in Burkina Faso. J Cancer Educ 29:69–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-013-0545-2

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Muhammad FHMS, Soon LK, Azlina Y (2016) Knowledge, awareness and perception towards prostate cancer among male public staffs in Kelantan. Int J of Public Health Clin Sci 3(6):105–115

Kinyao M, Kishoyina G (2018) Attitude, perceived risk and intention to screen for prostate cancer by adult men in Kasikeu sub location, Makueni County, Kenya. Ann Med Health Sci Res 8(3):125–132

Agbugui JO, Obarisiagbon EO, Nwajei CO, Osaigbovo EO, Okolo JC, Akinyele AO (2013) Awareness and knowledge of prostate cancer among men in Benin City, Nigeria. J Med Biomed Res 12(2):42–47

Wanyagah P (2013) Prostate cancer awareness, knowledge, perception on self-vulnerability and uptake of screening among men in Nairobi. Kenyatta University, Kenya

Arafa MA, Rabah DM, Wahdan IH (2012) Awareness of general public towards cancer prostate and screening practice in Arabic communities: a comparative multi-center study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 13:4321–4326

Makado E, Makado RK, Rusere MT (2015) An assessment of knowledge of and attitudes towards prostate cancer screening among men aged 40 to 60 years at Chitungwiza Central Hospital in Zimbabwe. Int J Humanit Soc Stud 3(4):45–55

Adibe MO, Oyine DA, Abdulmuminu I, Chibueze A (2017) Knowledge, attitudes and perceptions of prostate cancer among male staff of the University of Nigeria. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 18(7):1961–1966

Ebuechi OM, Otumu IU (2011) Prostate screening practices among male staff of the University of Lagos, Lagos, Nigeria. Afr J Urol 17(4):122–134

Download references

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, I express my sincere, heartfelt and profound gratitude to the Almighty God for guiding, protecting and seeing me through the entire process of conducting this study. I am also grateful to my supervisor Prof. Victor Mwanasakale for his zeal and tireless efforts in seeing to it that this work becomes a reality. Let me also express my gratitude to Prof. Seter Siziya and the entire public health team for all the advice, encouragement. I would also like to thank the entire management at the Copperbelt University Michael Chilufya Sata School of Medicine for a friendly atmosphere. I would also like to thank my family back home for all the support and trust vested in me as well as my friends, roommates and class mates for the moral support.

A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the award of the Bachelors degree in medicine and surgery (MBChB).

This work was funded by the Government of the Republic of Zambia through the Ministry of Higher Education through its Higher Education Loans and Scholarships Board. As part of policy, the Ministry of Higher Education through its Higher Education Loans and Scholarships Board finances students in Higher Education institutions whose training demands the carrying out of research. Funding given covers for such expenses incurred during research such as printing and photocopying of data collection tools, transport charges for the researcher during the whole process and ethical clearance charges.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Michael Chilufya Sata School of Medicine, The Copperbelt University, P.O. Box 71191, Ndola, Zambia

Sakala Gift & Mwanakasale Victor

Pan - African Organization for Health, Education and Research (POHER), Lusaka, Zambia

Kasongo Nancy

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

SG is the corresponding author, and KN and MV are the contributing authors. SG constructed the manuscript, collected data, analysed and interpreted data and also edited the manuscript. KN constructed the manuscript, analysed and interpreted data and extensively edited the manuscript. MV constructed the manuscript, extensively edited the manuscript and supervised this thesis study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Author’s information

The corresponding author (S.G) is currently pursuing his Bachelors degree in Medicine and Surgery (MBChB) at the Copperbelt University Michael Chilufya Sata School of Medicine in Zambia. K.N is a Pan African Organization for Health, Education and Research (POHER) scholar with a rich research background, who has presented at so many conferences. She was a recipient of the international research elective which took place at University of Missouri School of Medicine, USA, for 2–3 months. She holds a Bachelors Degree of Medicine and Surgery (MBChB) and graduated as the Best student. M.V was also the supervisor of this work. He holds BSc Human Biology, MBChB, MSc and a PhD in Parasitology and is an Associate Professor of Parasitology at the Copperbelt University Michael Chilufya Sata School of Medicine, Zambia.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sakala Gift .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

A request to conduct the study was sought from the Tropical Diseases Research Centre (TDRC) research ethics committee (IRB Registration Number: 00002911, FWA Number: 00003729) as well as the National Health Research Authority (NHRA). Management at Kitwe Teaching Hospital was assured that confidentiality would not be breached and that the data obtained in the study would not be used for any other purpose besides that specified in the study protocol. Informed and written consent was obtained from participants. During data collection, no identifying images or other personal or clinical details of participants were collected. They were treated with at-most respect and dignity and their rights to privacy and confidentiality were not violated at any point.

Consent for publication

In this study, no data that could compromise the anonymity of participants such as images or other personal or clinical details were collected. As such, it was not applicable.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1:.

Dataset for AFJU-D-19-00041R2 manuscript.

Appendix: Questionnaire

Topic: assessment of knowledge, practice and attitude towards prostate cancer screening among male patients aged 40 years and above at Kitwe Teaching Hospital.

NAME OF INTERVIEWER:…………………………………………………………

SERIAL NUMBER OF PARTICIPANT:…………………………………………….

DATE:…………………………………………………………………………………

1.1 Section A: demographic characteristics

Instruction: Please, tick as appropriate.

1. Age:…………years

2. Marital status: Single [] Married [] Divorced [] Separated []

3. Religion: Christian [] Muslim [] Traditional []

4. Educational level: Primary [] Secondary [] Tertiary [] No formal education []

5. Occupation: Trader [] Civil servant [] Taxi driver [] Businessman [] Electrician [] Mechanic [] Barber [] Other (please specify)

1.2 Section B: family history of cancer

6. Does anyone in your family have cancer? Yes [] No []

i) What type of cancer………………………………………………………

ii) What is their relation to you………………………………………………

7. Has anyone in your family died of Cancer Yes [] No []

i) What type of cancer……………………………………………………..

ii) What is their relation to you……………………………………………

1.3 Section C: knowledge

8. Have you heard of prostate cancer before: Yes [] No []

i) Where did you hear it from Friends [] Read about it [] TV [] Radio [] Doctor [] Nurse [] Relative []

ii) Which gender does prostate cancer affect Men only [] Women only [] Both men and women [] I do not know []

iii) Which of the following factors could make a person more likely to develop prostate cancer. Please tick as many as possible

a) Family history of the disease [] b) Drinking alcohol [] c) Age [] d)Exercise [] e) Diet [] f) Smoking []

9. Do you know symptoms of prostate cancer Yes [] No []

If Yes, what are they? Tick as many as possible. a) Excessive urination at night [] b)Headache [] c) blood in urine [] d) High temperature [] e) Bone pain [] f) Painful sex [] g) Loss of sex drive [] h) Infertility [] i) cough []

10. Is prostate cancer preventable Yes [] No [] I do not know []

a) How can it be prevented? Genital hygiene [] regular screening [] condom use [] use of right diet [] avoiding many sexual partners []

11. Is prostate cancer curable Yes [] No [] I don’t know []

1.4 Section D: practice

12. Have you been screened for prostate cancer within the last two years? Yes [] No []

a) Which method was used Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) [] Digital Rectal Examination (DRE) [] I do not know []

b) What was the outcome of the screening? Positive [] Negative []

13. Do you have any intention of getting screened in the nearest future? Yes [] No []

1.5 Section E: attitude towards prostate cancer screening

14. Prostate cancer screening is good Yes [] No []

15. Going for prostate cancer screening is a waste of time Yes [] No []

16. Prostate cancer screening has side effects that can cause harmful effects to the body Yes [] No []

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Gift, S., Nancy, K. & Victor, M. Assessment of knowledge, practice and attitude towards prostate cancer screening among male patients aged 40 years and above at Kitwe Teaching Hospital, Zambia. Afr J Urol 26 , 70 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12301-020-00067-0

Download citation

Received : 01 November 2019

Accepted : 16 September 2020

Published : 07 November 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12301-020-00067-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Prostate cancer screening

- Open access

- Published: 06 May 2021

Knowledge of prostate cancer presentation, etiology, and screening practices among women: a mixed-methods systematic review

- Ebenezer Wiafe ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0496-5737 1 , 2 ,

- Kofi Boamah Mensah 1 , 3 ,

- Adwoa Bemah Boamah Mensah 3 ,

- Varsha Bangalee 1 &

- Frasia Oosthuizen 1

Systematic Reviews volume 10 , Article number: 138 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

2877 Accesses

5 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

With the burden of prostate cancer, it has become imperative to exploit cost-effective ways to tackle this menace. Women have demonstrated their ability to recognize early cancer signs, and it is, therefore, relevant to include women in strategies to improve the early detection of prostate cancer. This systematic review seeks to gather evidence from studies that investigated women’s knowledge about (1) the signs and symptoms, (2) causes and risk factors, and (3) the screening modalities of prostate cancer. Findings from the review will better position women in the fight against the late detection of prostate cancer.

The convergent segregated approach to the conduct of mixed-methods systematic reviews was employed. Five databases, namely, MEDLINE (EBSCOhost), CINAHL (EBSCOhost), PsycINFO (EBSCOhost), Web of Science, and EMBASE (Ovid), were searched from January 1999 to December 2019 for studies conducted with a focus on the knowledge of women on the signs and symptoms, the causes and risk factors, and the screening modalities of prostate cancer.

Of 2201 titles and abstracts screened, 22 full-text papers were retrieved and reviewed, and 7 were included: 3 quantitative, 1 qualitative, and 3 mixed-methods studies. Both quantitative and qualitative findings indicate that women have moderate knowledge of the signs and symptoms and the causes and risk factors of prostate cancer. However, women recorded poor knowledge about prostate cancer screening modalities or tools.

Conclusions

Moderate knowledge of women on the signs and symptoms and the causes and risk factors of prostate cancer was associated with education. These findings provide vital information for the prevention and control of prostate cancer and encourage policy-makers to incorporate health promotion and awareness campaigns in health policies to improve knowledge and awareness of prostate cancer globally.

Systematic review registration

Open Science Framework (OSF) registration DOI: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/BR456

Peer Review reports

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most common non-skin cancer occurring in men and is accountable for 3.8% of all mortality caused by cancer in men [ 1 , 2 ]. According to the GLOBOCAN, 2018 database, it is estimated that it is the fifth primary cause of cancer death in men globally. It further reported that the highest mortality rate is found in the Caribbean and Southern African men worldwide [ 1 , 3 ]. A recent study by Yeboah-Asiamah et al. reported that PCa was the second most common cancer in areas such as Australia, the USA, and New Zealand [ 4 ]. Though fewer than 30% of all incidence of PCa are from developing countries, these countries have previously been estimated to have the highest mortality from PCa due to late diagnosis [ 5 , 6 ]. Although sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has a low rate of the disease, the incidence is projected to increase if screening is encouraged [ 7 ]. Hence, PCa remains a vital public health concern in both developed and developing countries.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in North America organized a workshop with the motive to explore strategies to control and prevent the disease based on the increasing incidence and mortality rate of PCa [ 8 ]. To address mortality rates related to the disease, participants recommended strategies to improve PCa awareness [ 8 ]. Also, as documented by many studies, PCa incidence is a direct reflection of the rate at which high-risk groups screen for the disease [ 4 , 9 ]. In Europe, early screening was attributed to a 20% reduction in PCa mortality rate [ 10 ]. Although there is evidence suggesting a reduction in PCa mortality due to early screening, a United States (US) study did not highlight a reduction in mortality [ 11 ]. The prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test and the digital rectal examination (DRE) are useful screening tools, although initial controversies were surrounding the use of these tools [ 12 ]. Because of overlap in PSA levels in men with prostatitis, benign prostatic hyperplasia, and PCa, it was assumed that PCa cannot be screened using the PSA test [ 13 ]. Catalona et al. demonstrated that PSA could be utilized as a screening tool for PCa, and it has widely been adopted [ 14 ]. DRE is the only procedure whereby physicians can examine part of the prostate gland [ 15 ]. The findings are only based on the physician impression, hence poor inter-rater reliability and also a limitation to the palpable region of the prostate gland [ 15 ]. However, DRE sometimes detects PCa in men with PSA, 4.0 ng/mL [ 16 ]. Regardless of the controversial nature of screening and the potential for early screening to reduce mortality, studies support the need to encourage screening [ 4 , 12 ].

Women have essential characteristics that make them better managers of family health as compared to men. Therefore, it is not surprising that there is evidence positioning women as individuals who make adequate observations about the health of their partners [ 9 , 17 ]. In promoting the early detection of PCa, women have been documented to observe the slightest symptoms presented by their partners and push them to seek medical attention [ 9 , 18 ]. In a study conducted by Blanchard et al., it was recommended that efforts must be made to actively involve women in improving the timely detection of PCa through the closure of knowledge gaps [ 19 ].

Also, men admit seeking out their wives’ opinions as sources of health information [ 20 ]. In the context of the early detection of PCa, women can play various roles such as information seekers, advocates, health advisors, and support persons [ 21 ]. Therefore, there is the need to gather current evidence about women’s knowledge of PCa as the findings will be vital in equipping women to contribute towards the early detection of the disease.

In light of the availability of limited evidence addressing the awareness of women on prostate cancer, this review will seek to combine quantitative and qualitative data to increase the validity of findings through data triangulation as recommended by Caruth and supported by Lizarondo et al. [ 22 , 23 ]. Thus, this review seeks to map out current evidence regarding women’s awareness of PCa under the scopes of (1) signs and symptoms, (2) risk factors and causes, and (3) screening guidelines.

Review question

Do women have adequate knowledge about prostate cancer?

Methodology

The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) reviewer’s manual for the conduct of mixed-methods critical appraisal and synthesis formed the backbone of the study [ 23 ]. With guidance from the JBI manual, a protocol was developed to guide the review process according to the convergent segregated approach [ 23 ]. The respective DOIs of the review protocol and review, registered with the Open Science Framework (OSF), are https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/EYHF2 and https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/BR456 . The review protocol is readily available to the scientific community [ 24 ].

Inclusion criteria

The following were grounds for the inclusion of studies:

Studies that were conducted among women aged 18 years and above.

Studies that were conducted among women of all racial backgrounds.

Studies published from January 1999 to December 2019.

Studies that were conducted among women of all geographical locations.

Studies of all research designs.

Studies that were conducted to investigate the knowledge of women on the signs and symptoms of prostate cancer as highlighted in the review protocol.

Studies that were conducted to investigate the knowledge of women on the causes and risk factors of prostate cancer as highlighted in the review protocol.

Studies that were conducted to investigate the knowledge of women on the screening recommendations of prostate cancer as highlighted in the review protocol.

Studies that were published in the English language.

Studies with abstract and full text available.

Exclusion criteria

The following were grounds for the exclusion of studies:

Studies that were published before January 1999 or after December 2019.

Studies that were not published in the English language.

Studies that include women below the age of 18 years.

Studies in which the age of included women cannot be established.

Studies that did not indicate the number/percentage of included women.

Studies that exclusively included men without any women component (18 years and above).

Studies conducted among women who were previously given education on prostate cancer.

Studies that exclusively involved lesbian, gay, bisexual, transsexual/transgender, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ) participants.

Studies that exclusively included healthcare professionals.

Studies that exclusively involved healthcare and college/university students.

Studies that do not include the outcome of interest.

Book chapters.

Reviews and overviews.

Abstracts and conference papers.

Dissertations and thesis.

Commentaries and letters to editors.

Studies published without abstracts.

Information sources and search strategy

An initial explorative search in PubMed founded search terms in preparation for comprehensive electronic search. The selected search terms, applied as MeSH terms, were combined with Boolean operators for a comprehensive electronic search in MEDLINE (EBSCOhost), CINAHL (EBSCOhost), PsycINFO (EBSCOhost), Web of Science, and EMBASE (Ovid) as “(prostate cancer ) AND (awareness OR knowledge) AND (signs OR symptoms) AND (risk factors OR causes) AND (screening) AND (women)”. The search strategy (Additional file 1 ), so developed, was utilized by the first (EW) and second (KBM) reviewers to independently conduct a literature search as outlined in the review protocol e24].

Selection of studies

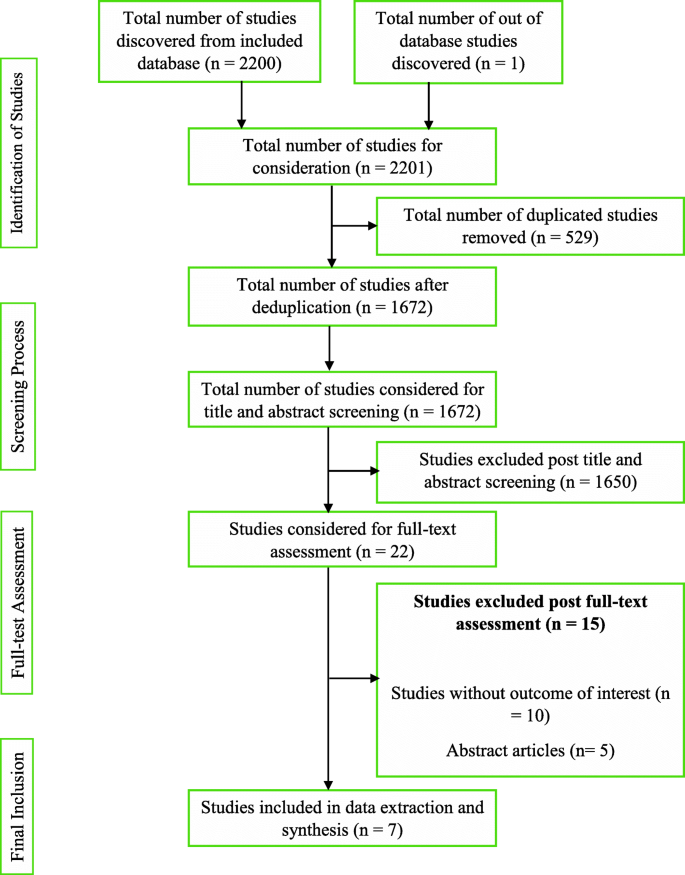

The first and second reviewers, being guided by the developed review protocol, singularly screened and compared the titles and abstracts of the literature search outcomes to a developed standard (the inclusion and exclusion criteria). Studies that successfully passed the initial stage of screening were subjected to the independent full-text reading by EW and KBM before consideration for data extraction. Lastly, hand-searching and snowballing on references of selected articles were done to find eligible studies in the grey area. There were no disagreements between EW and KBM. Hence, the third reviewer (ABBM) assessed the studies before data extraction was conducted by the lead author according to the JBI data extraction tools outlined in the review protocol [ 24 ]. The characteristic of studies that successfully went through the data extraction, the key findings that were extracted, and a summary of the study selection process are detailed respectively (Tables 1 and 2 and Fig. 1 ).

Summary of study selection process

Quality assessment

As described in the review protocol [ 24 ], the methodological quality assessment tool (Additional file 2 ) was adopted and modified for this review due to the similarities this review shares with the study conducted by Mensah et al. [ 30 ]. The tool appraised the studies’ quality based on the study sample representativeness, response rate, reliability, and validity of the data collection tool. The tool was modified to suit the results from the included studies. A score was calculated, and the quality of the studies was classified as weak (0 to 33.9%), moderate (34 to 66.9%), or strong (67 to 100%). Eligible records were subjected to independent quality assessment by EW and KBM. Methodological quality outcomes were not grounds for exclusion.

Synthesis and integration of findings

The review findings were subjected to the convergent segregated approach to synthesis and integration according to the developed review protocol [ 24 ]. A narrative synthesis was separately performed for qualitative and quantitative findings. The heterogeneous nature of the review findings did not support the conduct of a meta-analysis. The results were finally integrated.

Conducting the review, according to the developed protocol, yielded 2200 study results. A detailed citation screening led to an additional study, which increased the total number of studies to 2201. Regarding the summary of the study selection process (Fig. 1 ), 1672 studies were obtained after 529 duplicates were removed from the pool of data. Post-titles and abstract review excluded 1650 studies leaving 22 studies. The 22 studies were further reduced to 7 after a full-text reading resulted in the exclusion of 15 studies.

Characteristics of included studies

The data extracted from the seven (7) studies are detailed (Table 1 ). The publication years ranged from 2003 to 2018 with 5 studies having been conducted in the USA. One of the studies was a multicenter study that involved multinationals [ 28 ]. The study with the highest female participants (4040 women) was conducted in Spain [ 26 ]. Webb et al. recruited the lowest sample size, 14 women [ 29 ]. A total of 5634 women were involved in the 7 studies. Two studies were solely conducted in women, three included other diseases, and two did not disclose study duration.

Quality of included studies

According to the scoring scheme of the quality assessment tool (Additional file 2 ), two studies [ 26 , 29 ] were evaluated as moderate quality whilst five studies were evaluated as strong quality. None of the studies was excluded based on methodological quality assessment outcomes. There was no disagreement between EW and KBM.

Review findings

Study findings, presented in Table 2 , were heterogeneous. Quantitative studies indicate that women knew about the existence of PCa. In exploring qualitative evidence, women exhibited knowledge of PCa. Therefore, both arms of the review are supportive of each other.

Women had moderate knowledge about the signs and symptoms of PCa drawing from quantitative findings. Women knew about the asymptomatic nature of the early stages of PCa. They also moderately knew urinary symptoms such as urinary frequency, difficulty in urinating, and dysuria. Qualitative studies indicate that women were aware prostate cancer patients, usually in advanced stages, could present with signs and symptoms such as urinary frequency, difficulty in urinating, glandular enlargement of the prostate, and erectile dysfunction. Hence, quantitative and qualitative findings revealed that women moderately knew the urinary symptoms of PCa.

Quantitative studies indicate an average score of women on knowledge of risk factors of PCa. Risk factors women knew were increasing age, presence of a first-degree relative, being genetically linked to Africa, and excessive truncal obesity. Qualitative evidence recognized all risk factors documented by the quantitative findings except truncal obesity. Also, identified risk factors included poor diet, inadequate exercise, stressful lifestyle, poor screening habits, cigarette smoking, and poor access to quality healthcare. Women wrongly reported sexual orientation and frequent sexual activity as risk factors. Therefore, qualitative findings confirm the quantitative claim that women have shared knowledge about the risk factors of PCa.

Quantitative studies indicate that women had poor knowledge about PCa screening guidelines, appropriate screening samples, and tools. Although it was reported that women knew about PSA and DRE, the proportions of women who had correct responses to screening knowledge items were not appreciable. Women poorly recognized urine as a screening sample, PSA as an exclusive diagnostic tool (where only 17.5% answered correctly), and failed to identify more than one screening tool (between 41 and 71% of women failed). Qualitative studies respectively reported PSA and blood as a screening tool and sample. Colonoscopy was wrongly reported as a PCa screening tool. Conclusively, both arms of the review reported women knew about PSA and had poor knowledge about PCa screening.

The heterogeneity of the study findings warranted the synthesis as a narrative [ 23 , 31 ]. The convergent segregated approach was employed according to the recommendation of the JBI reviewer’s manual [ 23 ].

Generally, from the quantitative evidence, women knew about prostate cancer [ 19 , 25 , 27 , 28 ]. The knowledge of women was found to have increased with educational and financial status [ 19 ], and disease familiarity [ 19 , 25 ]. The awareness of women about the existence of PCa increased when the disease was mentioned compared to an initial request for women to list cancers [ 28 ]. Qualitative evidence showed that women were aware of PCa [ 18 , 27 ]. They appreciated and specifically requested for PCa education partly because they could not tell the location of the prostate gland [ 18 ]. Thus, quantitative and qualitative evidence indicates that women know about PCa. Women’s awareness could be due to their role in family health management and the possible health-seeking behavior of educated and financially strong women. As persons are faced with the experiences of a health condition, they will seek to make sense of this illness by acquiring knowledge [ 32 ], experiences, and beliefs; hence, this theory might explain the improved awareness of women who were familiar with the disease.

Most of the quantitative studies indicate that women are aware of the asymptomatic nature of early-stage PCa [ 19 , 25 , 27 ]. Symptoms that women had a fair knowledge about included urinary frequency, difficulty in urinating, and dysuria [ 25 ]. Findings from one of the qualitative studies indicate that women fairly recognized urinary frequency, difficulty in urinating, glandular enlargement of the prostate, and erectile dysfunction as signs and symptoms of PCa [ 18 ]. Being familiar with the disease may explain the awareness of women of the urinary symptoms associated with PCa.

According to Okoro and colleagues’ quantitative study, although knowledge of PCa was not adequate, women knew associated risk factors such as being a first-degree relative, being a man of African descent, and excessive truncal obesity [ 27 ]. Blanchard et al. also documented women’s recognition of increasing age as a PCa risk factor [ 19 ]. One of the qualitative studies indicates women knew increasing age could increase a man’s chance for PCa development [ 18 , 29 ]. Other causes and risk factors women identified included poor diet, inadequate exercise, stressful lifestyle, family history of the disease, being of African descent, poor screening habits, cigarette smoking, and poor access to quality healthcare [ 18 ]. Erroneously, one study reported that women perceived sexual orientation and frequent sexual activity as risk factors [ 18 ]. Both quantitative and qualitative findings documented women knew increasing age, family history, and African descent as PCa risk factors.

Quantitatively, women’s responses to queries about PCa screening were poor [ 25 , 28 ]. Some women were unable to recognize at least a PCa screening tool whilst others mistakenly recognized urine as a suitable sample for PCa screening [ 28 ]. According to Okoro et al., the majority of women exclusively tagged PSA elevation as a basis for PCa diagnosis [ 27 ]. This, therefore, calls for extensive education because benign prostatic hyperplasia, prostatitis, and PCa usually present with elevated PSA [ 13 ]. Evidence from qualitative findings indicated women knew physical examination must augment blood analysis [ 29 ]. Also, women mentioned PSA and colonoscopy as screening tools [ 18 ]. The results from included qualitative studies confirmed that women had poor knowledge about PCa screening. The mention of colonoscopy as a screening tool further supports a lack of adequate knowledge about PCa screening.

This critical appraisal and synthesis revealed over the 20 years of study search, only four studies out of the seven included studies investigated all the outcomes of interest. Two studies did not investigate women’s awareness of the signs and symptoms [ 26 , 29 ] and the causes and risk factors [ 25 , 26 ] of PCa. Therefore, although quantitative and qualitative findings were supportive of each other, studies investigating the causes and risk factors, as well as the signs and symptoms of PCa, were lacking.

Recommendations for practice

From the review findings, it is recommended that PCa control programs should also focus on educating women. Clinicians and public health practitioners should include women in prostate cancer health promotion. Women should be encouraged to attend PCa clinics with their male significant others suffering from the disease, and the effect of this strategy in reducing PCa mortality rate must be investigated.

Recommendations for research

Further studies are recommended to investigate the knowledge of women living in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) about PCa. Such studies should focus extensively on the knowledge of women on PCa screening. Also, it is recommended for research to develop and pilot a PCa educational intervention model, applicable to women to reduce the burden of the disease. This tool should be culturally specific for easy acceptance and recognition. Also, current evidence on the willingness of women to offer social support to men with PCa should be investigated.

Study limitations

The various restrictions that were imposed on the literature search included a search range from January 1999 to December 2019, a search into only 5 databases, and the outright exclusion of non-English publications. These constitute selection bias. Therefore, some important studies could have been left out of the review.

Although five (5) out of the seven (7) included studies explicitly indicated recruiting participants of African backgrounds, none of the studies were conducted in Africa. Hence, the global generalizability of the review findings, to most importantly cover low and middle-income countries, cannot be documented.

The exclusion of studies conducted in women who received education on prostate cancer, healthcare professionals, healthcare students, and college/university students, and further exclusion of studies that involved (LGBTQ) participants further constitute selection bias.

It is imperative to note that the various limitations, in connection to the included studies, documented in Table 2 have an effect on this review and, as such, could be considered as potential limitations.

Availability of data and materials

Data and other pieces of information are available at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/BR456

Abbreviations

Centers for disease control and prevention

Digital rectal examination

Global cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence

Joanna briggs institute

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transsexual/transgender, and queer/questioning

Open science framework

Low- and middle-income countries

- Prostate cancer

Prostate-specific antigen

Sub-Saharan Africa

United States

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21492 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

James LJ, Wong G, Craig JC, Hanson CS, Ju A, Howard K, et al. Men’s perspectives of prostate cancer screening: a systematic review of qualitative studies. PloS One. 2017;12(11):e0188258. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0188258 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

GLOBOCAN. GLOBOCAN 2008: Ghana Fact Sheets. 2018. Available from: file:///C:/Users/user-pc/Downloads/288-ghana-fact-sheets.pdf.

Yeboah-Asiamah B, Yirenya-Tawiah D, Baafi D, Ackumey M. Perceptions and knowledge about prostate cancer and attitudes towards prostate cancer screening among male teachers in the Sunyani Municipality, Ghana. Afr J Urol. 2017;23(4):184-91.

Rebbeck TR, Devesa SS, Chang B-L, Bunker CH, Cheng I, Cooney K, et al. Global patterns of prostate cancer incidence, aggressiveness, and mortality in men of African descent. Prostate Cancer. 2013;2013:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/560857 .

Article Google Scholar

Mofolo N, Betshu O, Kenna O, Koroma S, Lebeko T, Claassen FM, et al. Knowledge of prostate cancer among males attending a urology clinic, a South African study. SpringerPlus. 2015;4(1):67. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-015-0824-y .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Jemal A, Bray F, Forman D, O'Brien M, Ferlay J, Center M, et al. Cancer burden in Africa and opportunities for prevention. Cancer. 2012;118(18):4372–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.27410 .

Dimah KP, Dimah A. Prostate cancer among African American men: a review of empirical literature. Journal of African American Studies. 2003;7(1):27–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12111-003-1001-x .

Rashid P, Denham J, Madjar I. Do women have a role in early detection of prostate cancer? Lessons from a qualitative study. Aust Fam Phys. 2007;36(5):375.

Google Scholar

Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, Tammela TL, Ciatto S, Nelen V, et al. Screening and prostate-cancer mortality in a randomized European study. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(13):1320–8. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0810084 .

Andriole GL, Crawford ED, Grubb RL III, Buys SS, Chia D, Church TR, et al. Mortality results from a randomized prostate-cancer screening trial. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(13):1310–9. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0810696 .

Nakandi H, Kirabo M, Semugabo C, Kittengo A, Kitayimbwa P, Kalungi S, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of Ugandan men regarding prostate cancer. Afr J Urol. 2013;19(4):165–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.afju.2013.08.001 .

Catalona WJ. Prostate cancer screening. Med Clin. 2018;102(2):199–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2017.11.001 .

Catalona WJ, Smith DS, Ratliff TL, Dodds KM, Coplen DE, Yuan JJ, et al. Measurement of prostate-specific antigen in serum as a screening test for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(17):1156–61. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199104253241702 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Wilbur J. Prostate cancer screening: the continuing controversy. Am Fam Phys. 2008;78(12):1377–84.

Federman DG, Pitkin P, Carbone V, Concato J, Kravetz JD. Screening for prostate cancer: are digital rectal examinations being performed? Hosp Pract. 2014;42(2):103–7. https://doi.org/10.3810/hp.2014.04.1108 .

Karim R, Lindberg L, Wamala S, Emmelin M. Men’s perceptions of women’s participation in development initiatives in rural Bangladesh. Am J Mens Health. 2018;12(2):398–410. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988317735394 .

Owens OL, Friedman DB, Hebert J. Commentary: Building an evidence base for promoting informed prostate cancer screening decisions: an overview of a cancer prevention and control program. Ethn Dis. 2017;27(1):55–62. https://doi.org/10.18865/ed.27.1.55 .

Blanchard K, Proverbs-Singh T, Katner A, Lifsey D, Pollard S, Rayford W. Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs of women about the importance of prostate cancer screening. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97(10):1378–85.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Taylor KL, Turner RO, Davis JL III, Johnson L, Schwartz MD, Kerner J, et al. Improving knowledge of the prostate cancer screening dilemma among African American men: an academic-community partnership in Washington, DC. Public Health Rep. 2016;116(6):590–8.

Miller SM, Roussi P, Scarpato J, Wen KY, Zhu F, Roy G. Randomized trial of print messaging: the role of the partner and monitoring style in promoting provider discussions about prostate cancer screening among African American men. Psychooncol. 2014;23(4):404–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3437 .

Caruth GD. Demystifying mixed methods research design: a review of the literature. Mevlana Int J Educ. 2013;3(2):112–22. https://doi.org/10.13054/mije.13.35.3.2 .

Lizarondo L, Stern C, Carrier J, Godfrey C, Rieger K, Salmond S, et al. Chapter 8: Mixed methods systematic reviews.: The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017 [Available from: https://wiki.joannabriggs.org/display/MANUAL/Chapter+8%3A+Mixed+methods+systematic+reviews .

Wiafe E, Mensah KB, Mensah ABB, Bangalee V, Oosthuizen F. The awareness of women on prostate cancer: a mixed-methods systematic review protocol. Syst Rev. 2020;9(1):1–6.

Brown N, Naman P, Homel P, Fraser-White M, Clare R, Browne R. Assessment of preventive health knowledge and behaviors of African-American and Afro-Caribbean women in urban settings. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(10):1644–51.

Carrasco-Garrido P, Hernandez-Barrera V, Lopez de Andres A, Jimenez-Trujillo I, Gallardo Pino C, Jimenez-Garcıa R. Awareness and uptake of colorectal, breast, cervical and prostate cancer screening tests in Spain. Eur J Public Health. 2014;24(2):264–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckt089 .

Okoro ON, Rutherford CA, Witherspoon SF. Leveraging the family influence of women in prostate cancer efforts targeting African American Men. J Racial Ethnic Health Disparities. 2018;5(4):820–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-017-0427-0 .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Schulman CC, Kirby R, Fitzpatrick JM. Awareness of prostate cancer among the general public: findings of an independent international survey. European Urology. 2003;44(3):294–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0302-2838(03)00200-8 .

Webb CR, Kronheim L, Williams JE, Hartman TJ. An evaluation of the knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of African-American men and their female significant others regarding prostate cancer screening. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(1):234–8.

PubMed Google Scholar

Mensah KB, Oosthuizen F, Bonsu AB. Cancer awareness among community pharmacist: a systematic review. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):299. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4195-y .

Lockwood C, Porritt K, Munn Z, Rittenmeyer L, Salmond S, Bjerrum M, et al. Chapter 2: Systematic reviews of qualitative evidence: the Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017 [Available from: https://wiki.joannabriggs.org/display/MANUAL/Chapter+2%3A+Systematic+reviews+of+qualitative+evidence .

Petrie K, Weinman J. Why illness perceptions matter. Clin Med. 2006;6(6):536–9. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.6-6-536 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

The review team gives recognition to Dr. Richard Ofori-Asenso.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

Ebenezer Wiafe, Kofi Boamah Mensah, Varsha Bangalee & Frasia Oosthuizen

Ho Teaching Hospital, Ho, Ghana

Ebenezer Wiafe

Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana

Kofi Boamah Mensah & Adwoa Bemah Boamah Mensah

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

EW is credited with the conception of the review, the coordination of the systematic review, the development of the search strategy, the search and selection of studies to be included in the review, the extraction and management of quantitative and qualitative data, the assessment of methodological quality, the filtering of all reference materials, the integration and interpretation of the data, and the drafting of the manuscript, and is the principal reviewer. KBM is credited with the conception of the review, the review of the search strategy, the search and selection of studies to be included in the review, the extraction and management of quantitative and qualitative data, the assessment of methodological quality, the integration and interpretation of the data, and the review of the manuscript. ABBM is credited with the review of the search strategy, the assessment of the studies before data extraction, and the review of the manuscript. VB is credited with the review of the manuscript, the coordination of the systematic review, and the as co-supervisor of the review. FO is credited with the conception of the review, the review of the manuscript, and the overall supervision of the review. All authors have reviewed and accepted the final manuscript of the review for publication. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ebenezer Wiafe .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethical permission was not required since the study did not involve the enrollment of humans or animals as study subjects.

Consent for publication

Competing interests, additional information, publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:..

Proposed search strategy using Medline via EBSCOhost

Additional file 2:.

Assessment of methodological quality of included studies

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Wiafe, E., Mensah, K.B., Mensah, A.B.B. et al. Knowledge of prostate cancer presentation, etiology, and screening practices among women: a mixed-methods systematic review. Syst Rev 10 , 138 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01695-5

Download citation

Received : 01 December 2020

Accepted : 29 April 2021

Published : 06 May 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01695-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Signs and symptoms

- Causes and risk factors

- Screening recommendations

Systematic Reviews

ISSN: 2046-4053

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Men’s perspectives of prostate cancer screening: A systematic review of qualitative studies

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Sydney School of Public Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia, Centre for Kidney Research, The Children’s Hospital at Westmead, Westmead, Australia

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Sydney School of Public Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia, Centre for Kidney Research, The Children’s Hospital at Westmead, Westmead, Australia, Centre for Transplant and Renal Research, Westmead Hospital, Westmead, Australia

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Centre for Kidney Research, The Children’s Hospital at Westmead, Westmead, Australia

Affiliations Department of General Practice, Westmead Clinical School, The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia, The George Institute for Global Health, Sydney, Australia

Affiliation Department of Urology, Westmead Hospital, Westmead, Australia

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

- Laura J. James,

- Germaine Wong,

- Jonathan C. Craig,

- Camilla S. Hanson,

- Angela Ju,

- Kirsten Howard,

- Tim Usherwood,

- Howard Lau,

- Allison Tong

- Published: November 28, 2017

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0188258

- Reader Comments

Prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed non-skin cancer in men. Screening for prostate cancer is widely accepted; however concerns regarding the harms outweighing the benefits of screening exist. Although patient’s play a pivotal role in the decision making process, men may not be aware of the controversies regarding prostate cancer screening. Therefore we aimed to describe men’s attitudes, beliefs and experiences of prostate cancer screening.

Systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies on men’s perspectives of prostate cancer screening. Electronic databases and reference lists were searched to October 2016.

Sixty studies involving 3,029 men aged from 18–89 years, who had been screened for prostate cancer by Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) or Digital Rectal Examination (DRE) and not screened, across eight countries were included. Five themes were identified: Social prompting (trusting professional opinion, motivation from family and friends, proximity and prominence of cancer); gaining decisional confidence (overcoming fears, survival imperative, peace of mind, mental preparation, prioritising wellbeing); preserving masculinity (bodily invasion, losing sexuality, threatening manhood, medical avoidance); avoiding the unknown and uncertainties (taboo of cancer-related death, lacking tangible cause, physiological and symptomatic obscurity, ambiguity of the procedure, confusing controversies); and prohibitive costs.

Conclusions

Men are willing to participate in prostate cancer screening to prevent cancer and gain reassurance about their health, particularly when supported or prompted by their social networks or healthcare providers. However, to do so they needed to mentally overcome fears of losing their masculinity and accept the intrusiveness of screening, the ambiguities about the necessity and the potential for substantial costs. Addressing the concerns and priorities of men may facilitate informed decisions about prostate cancer screening and improve patient satisfaction and outcomes.

Citation: James LJ, Wong G, Craig JC, Hanson CS, Ju A, Howard K, et al. (2017) Men’s perspectives of prostate cancer screening: A systematic review of qualitative studies. PLoS ONE 12(11): e0188258. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0188258

Editor: Jo Waller, UCL, UNITED KINGDOM

Received: December 28, 2016; Accepted: November 1, 2017; Published: November 28, 2017

Copyright: © 2017 James et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding: LJJ and JCC are supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council Program Grant (APP1092957). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed non-skin cancer in men and accounts for 48 deaths per 100,000 men per year in the UK.[ 1 ] One in seven men in Australia and the UK will develop prostate cancer by age 75 years.[ 2 , 3 ] The overall age-standardised incidence is 182 per 100,000 men per year in the UK,[ 4 ] and 163 and 129 per 100,000 men per year in Australia and US respectively.[ 5 , 6 ]

Screening for prostate cancer using prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is widely used in the general population, contributing to a threefold increase in the incidence of diagnosed prostate cancer.[ 7 ] However, screening remains controversial, in part due to conflicting results from recent large randomised controlled trials. One large-scale trial, conducted in the US, found no difference in prostate cancer mortality between the screened and control group after 13 years,[ 8 ] whereas another European trial, with a similar follow up, demonstrated a 21% relative reduction in the risk of prostate cancer-specific death.[ 9 ]

More recently, concerns about overdiagnosis have also been raised.[ 10 – 12 ] Early detection through screening can lead to overdiagnosis, which consequently may require further unnecessary investigations, including prostatectomy and radiation therapy.[ 10 ] It remains uncertain whether screening confers appreciable survival benefits, and treatment of screen detected disease can lead to adverse events including urinary incontinence, erectile dysfunction, bowel problems, and unwarranted anxiety.[ 10 , 13 ] As a result, current guidelines for PSA testing vary worldwide.