Robert Hooke

(1635-1703)

Who Was Robert Hooke?

Scientist Robert Hooke was educated at Oxford and spent his career at the Royal Society and Gresham College. His research and experiments ranged from astronomy to biology to physics; he is particularly recognized for the observations he made while using a microscope and for "Hooke's Law" of elasticity. Hooke died in London in 1703.

Early Life and Education

Robert Hooke was born in the town of Freshwater, on England’s Isle of Wight, on July 18, 1635. His parents were John Hooke, who served as curate for the local church parish, and Cecily (née Gyles) Hooke.

Initially a sickly child, Hooke grew to be a quick learner who was interested in painting and adept at making mechanical toys and models. After his father’s death in 1648, the 13-year-old Hooke was sent to London to apprentice with painter Peter Lely. This connection turned out to be a short one, and he went instead to study at London’s Westminster School.

In 1653, Hooke enrolled at Oxford's Christ Church College, where he supplemented his meager funds by working as an assistant to the scientist Robert Boyle. While studying subjects ranging from astronomy to chemistry, Hooke also made influential friends, such as future architect Christopher Wren.

Teaching, Research and Other Occupations

Hooke was appointed curator of experiments for the newly formed Royal Society of London in 1662, a position he obtained with Boyle's support. Hooke became a fellow of the society in 1663.

Unlike many of the gentleman scientists he interacted with, Hooke required an income. In 1665, he accepted a position as professor of geometry at Gresham College in London. After the "Great Fire" destroyed much of London in 1666, Hooke became a city surveyor. Working with Wren, he assessed the damage and redesigned many of London’s streets and public buildings.

Major Discoveries and Achievements

A true polymath, the topics Hooke covered during his career include comets, the motion of light, the rotation of Jupiter, gravity, human memory and the properties of air. In all of his studies and demonstrations, he adhered to the scientific method of experimentation and observation. Hooke also utilized the most up-to-date instruments in his many projects.

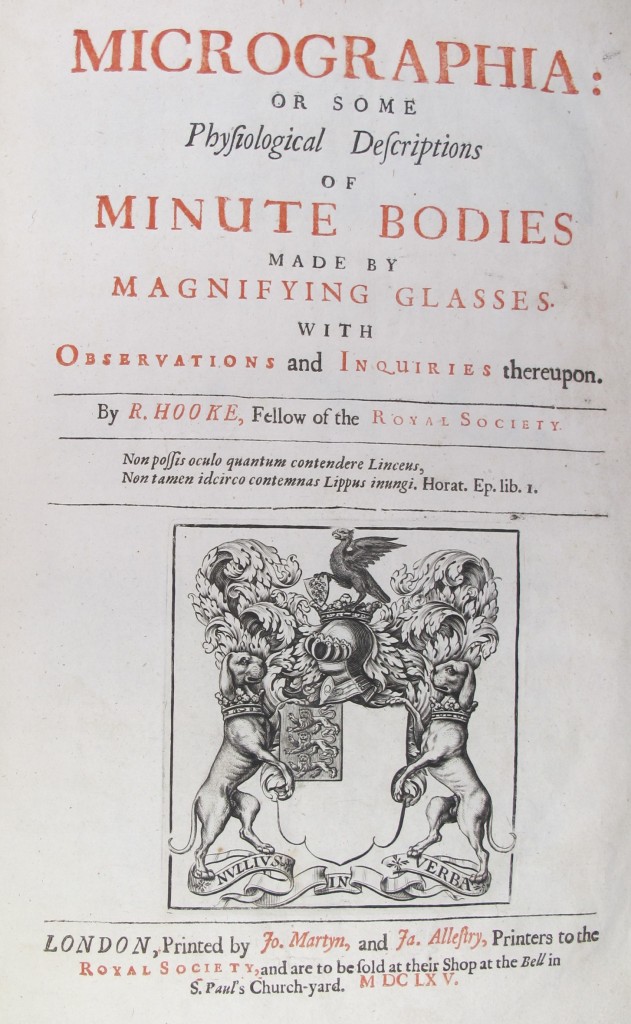

Hooke’s most important publication was Micrographia , a 1665 volume documenting experiments he had made with a microscope. In this groundbreaking study, he coined the term "cell" while discussing the structure of cork. He also described flies, feathers and snowflakes, and correctly identified fossils as remnants of once-living things.

The 1678 publication of Hooke's Lectures of Spring shared his theory of elasticity; in what came to be known as "Hooke’s Law," he stated that the force required to extend or compress a spring is proportional to the distance of that extension or compression. In an ongoing, related project, Hooke worked for many years on the invention of a spring-regulated watch.

Personal Life and Death

Hooke never married. His niece, Grace Hooke, his longtime live-in companion and housekeeper, as well as his eventual lover, died in 1687; Hooke was inconsolable at the loss.

In his last year of life, Hooke suffered from symptoms that may have been caused by diabetes. He died at the age of 67 in London on March 3, 1703.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Robert Hooke

- Birth Year: 1635

- Birth date: July 18, 1635

- Birth City: Freshwater, Isle of Wight

- Birth Country: England

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Robert Hooke is known as a "Renaissance Man" of 17th century England for his work in the sciences, which covered areas such as astronomy, physics and biology.

- Education and Academia

- Journalism and Nonfiction

- Architecture

- Business and Industry

- Science and Medicine

- Technology and Engineering

- Astrological Sign: Cancer

- Wadham College

- Death Year: 1703

- Death date: March 3, 1703

- Death City: London

- Death Country: England

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Robert Hooke Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/scientists/robert-hooke

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: June 22, 2020

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

Famous British People

The Real Royal Scheme Depicted in ‘Mary & George’

William Shakespeare

Anya Taylor-Joy

Kate Middleton, Princess of Wales

Kensington Palace Shares an Update on Kate

Amy Winehouse

Prince William

Where in the World Is Kate Middleton?

Christopher Nolan

Emily Blunt

Jane Goodall

Biography of Robert Hooke, the Man Who Discovered Cells

Robert Hooke/Wikimedia Commons/Public domain

- Cell Biology

- Weather & Climate

Robert Hooke (July 18, 1635–March 3, 1703) was a 17th-century "natural philosopher"—an early scientist—noted for a variety of observations of the natural world. But perhaps his most notable discovery came in 1665 when he looked at a sliver of cork through a microscope lens and discovered cells.

Fast Facts: Robert Hooke

- Known For: Experiments with a microscope, including the discovery of cells, and coining of the term

- Born: July 18, 1635 in Freshwater, the Isle of Wight, England

- Parents: John Hooke, vicar of Freshwater and his second wife Cecily Gyles

- Died: March 3, 1703 in London

- Education: Westminster in London, and Christ Church at Oxford, as a laboratory assistant of Robert Boyle

- Published Works: Micrographia: or some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies made by Magnifying Glasses with Observations and Inquiries Thereupon

Robert Hooke was born July 18, 1635, in Freshwater on the Isle of Wight off the southern coast of England, the son of the vicar of Freshwater John Hooke and his second wife Cecily Gates. His health was delicate as a child, so Robert was kept at home until after his father died. In 1648, when Hooke was 13, he went to London and was first apprenticed to painter Peter Lely and proved fairly good at the art, but he left because the fumes affected him. He enrolled at Westminster School in London, where he received a solid academic education including Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, and also gained training as an instrument maker.

He later went on to Oxford and, as a product of Westminster, entered Christ Church college, where he became the friend and laboratory assistant of Robert Boyle, best known for his natural law of gases known as Boyle's Law. Hooke invented a wide range of things at Christ Church, including a balance spring for watches, but he published few of them. He did publish a tract on capillary attraction in 1661, and it was that treatise the brought him to the attention of the Royal Society for Promoting Natural History, founded just a year earlier.

The Royal Society

The Royal Society for Promoting Natural History (or Royal Society) was founded in November 1660 as a group of like-minded scholars. It was not associated with a particular university but rather funded under the patronage of the British king Charles II. Members during Hooke's day included Boyle, the architect Christopher Wren , and the natural philosophers John Wilkins and Isaac Newton; today, it boasts 1,600 fellows from around the world.

In 1662, the Royal Society offered Hooke the initially unpaid curator position, to furnish the society with three or four experiments each week—they promised to pay him as soon as the society had the money. Hooke did eventually get paid for the curatorship, and when he was named a professor of geometry, he gained housing at Gresham college. Hooke remained in those positions for the rest of his life; they offered him the opportunity to research whatever interested him.

Observations and Discoveries

Hooke was, like many of the members of the Royal Society, wide-reaching in his interests. Fascinated by seafaring and navigation, Hooke invented a depth sounder and water sampler. In September 1663, he began keeping daily weather records, hoping that would lead to reasonable weather predictions. He invented or improved all five basic meteorological instruments (the barometer, thermometer, hydroscope, rain gauge, and wind gauge), and developed and printed a form to record weather data.

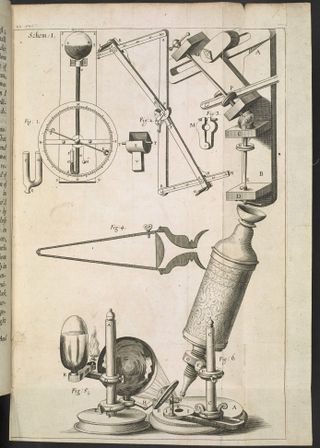

Some 40 years before Hooke joined the Royal Society, Galileo had invented the microscope (called an occhiolino at the time, or "wink" in Italian); as curator, Hooke bought a commercial version and began an extremely wide and varying amount of research with it, looking at plants, molds, sand, and fleas. Among his discoveries were fossil shells in sand (now recognized as foraminifera), spores in mold, and the bloodsucking practices of mosquitoes and lice.

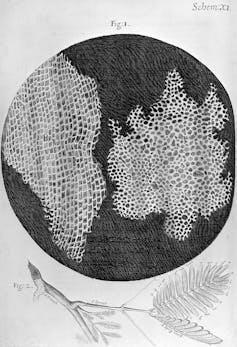

Discovery of the Cell

Hooke is best known today for his identification of the cellular structure of plants. When he looked at a sliver of cork through his microscope, he noticed some "pores" or "cells" in it. Hooke believed the cells had served as containers for the "noble juices" or "fibrous threads" of the once-living cork tree. He thought these cells existed only in plants, since he and his scientific contemporaries had observed the structures only in plant material.

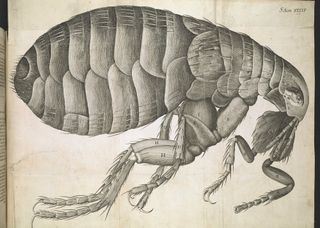

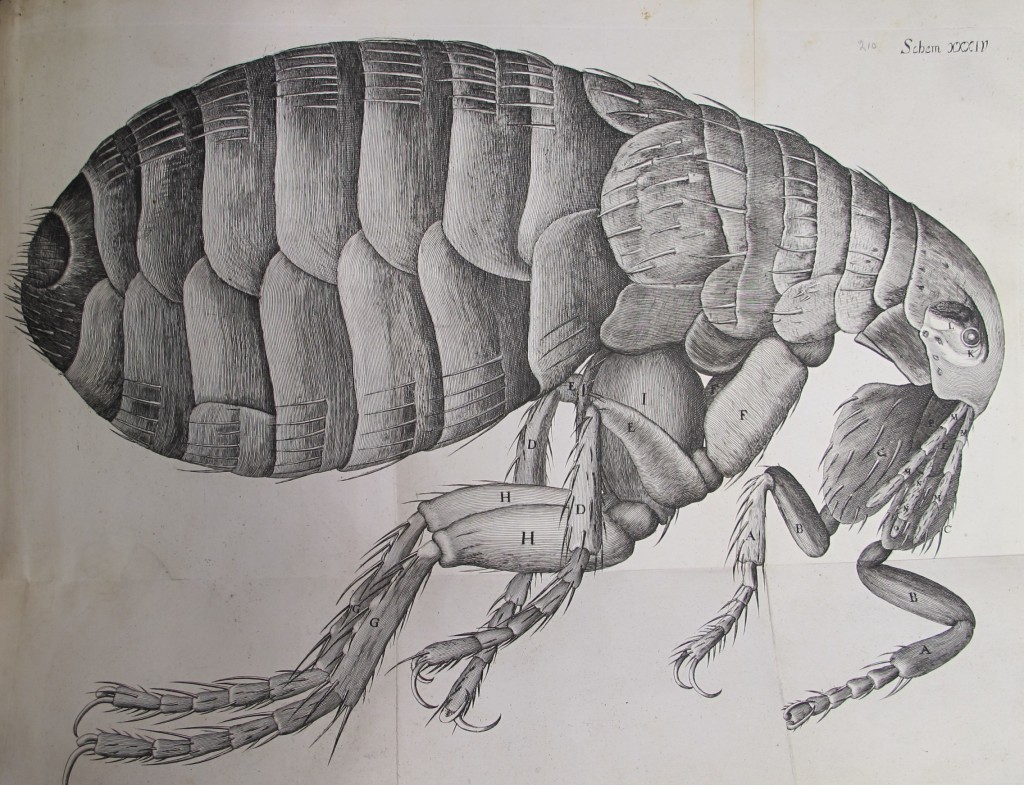

Nine months of experiments and observations are recorded in his 1665 book "Micrographia: or some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies made by Magnifying Glasses with Observations and Inquiries Thereupon," the first book describing observations made through a microscope. It featured many drawings, some of which have been attributed to Christopher Wren, such as that of a detailed flea observed through the microscope. Hooke was the first person to use the word "cell" to identify microscopic structures when he was describing cork.

His other observations and discoveries include:

- Hooke's Law: A law of elasticity for solid bodies, which described how tension increases and decreases in a spring coil

- Various observations on the nature of gravity, as well as heavenly bodies such as comets and planets

- The nature of fossilization, and its implications for biological history

Death and Legacy

Hooke was a brilliant scientist, a pious Christian, and a difficult and impatient man. What kept him from true success was a lack of interest in mathematics. Many of his ideas inspired and were completed by others in and outside of the Royal Society, such as the Dutch pioneer microbiologist Antoni van Leeuwenhoek (1632–1723), navigator and geographer William Dampier (1652–1715), geologist Niels Stenson (better known as Steno, 1638–1686), and Hooke's personal nemesis, Isaac Newton (1642–1727). When the Royal Society published Newton's "Principia" in 1686, Hooke accused him of plagiarism, a situation so profoundly affecting Newton that he put off publishing "Optics" until after Hooke was dead.

Hooke kept a diary in which he discussed his infirmities, which were many, but although it doesn't have literary merit like Samuel Pepys', it also describes many details of daily life in London after the Great Fire. He died, suffering from scurvy and other unnamed and unknown illnesses, on March 3, 1703. He neither married nor had children.

- Egerton, Frank N. " A History of the Ecological Sciences, Part 16: Robert Hooke and the Royal Society of London ." Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America 86.2 (2005): 93–101. Print.

- Jardine, Lisa. " Monuments and Microscopes: Scientific Thinking on a Grand Scale in the Early Royal Society ." Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London 55.2 (2001): 289–308. Print.

- Nakajima, Hideto. " Robert Hooke's Family and His Youth: Some New Evidence from the Will of the Rev. John Hooke ." Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London 48.1 (1994): 11–16. Print.

- Whitrow, G. J. " Robert Hooke ." Philosophy of Science 5.4 (1938): 493–502. Print.

" Fellows ." The Royal Society.

- Robert Hooke Biography (1635 - 1703)

- Biography of Robert Hooke

- Sir Christopher Wren, the Man Who Rebuilt London After the Fire

- Biography of Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, Father of Microbiology

- History of Microscopes

- History of the Microscope

- Meet William Herschel: Astronomer and Musician

- The History of the Hygrometer

- Biography of Isaac Newton, Mathematician and Scientist

- 17th Century Timeline, 1600 Through 1699

- Cosmos Episode 3 Viewing Worksheet

- Jan Ingenhousz: Scientist Who Discovered Photosynthesis

- What Is Cell Biology?

- Biography of Charles Wheatstone, British Inventor and Entrepreneur

- Biography of Jagadish Chandra Bose, Modern-Day Polymath

- Biography of Humphry Davy, Prominent English Chemist

MacTutor

Robert hooke.

Hooke was fortunate in gaining the respect of Dr Busby and being left to follow his own pursuits of knowledge just as he had before attending Westminster School.

... Hooke never took a bachelor's degree [ but ] Oxford had given him more than a thousand degrees could match.

... use of springs instead of gravity for making a body vibrate in any posture.

Before I went to bed I sat up till two o'clock in my chamber reading Mr Hooke's Microscopical Observations, the most ingenious book that ever I read in my life.

Micrographia remains one of the masterpieces of seventeenth century science. ... [ it ] presented not a systematic investigation of any one question, but a bouquet of observations with courses from the mineral, animal and vegetable kingdoms. Above all, the book suggested what the microscope could do for biological science.

Wren and Hooke dominated and guided the work, and cemented a friendship that lasted throughout their lives. To Hooke the position of surveyor was a financial boon, more than compensating for the uncertainty of his other income.

... of compounding the celestiall motions of the planetts of a direct motion by the tangent ( inertial motion ) and an attractive motion towards the centrall body ... my supposition is that the Attraction always is in a duplicate proportion to the Distance from the Center Reciprocall ...

He was a brisk walker, and enjoyed walking in the fields north of the City. ... he generally rose early, perhaps to save candles, and to work in daylight and prevent strain to his eyes. ... Sometimes Hooke would work all through the night, and then have a nap after dinner. As well as drinking a variety of waters ... he drank brandy, port, claret, sack, and birch juice wine which he found to be delicious. He also had a barrel of Flanstead's ale and Tillotson's ale. There are a few instances when he recorded that he had been drunk ... He was a gregarious person, who liked to meet people, particularly those who had travelled abroad ...

.. often troubled with headaches, giddiness, and fainting, and with a general decay all over, which hindered his philosophical studies, yet he still read some lectures whenever he was able.

[ Huygens ' Preface ] is concerning those properties of gravity which I myself first discovered and showed to this Society and years since, which of late Mr Newton has done me the favour to print and publish as his own inventions. And particularly that of the oval figure of the Earth which was read by me to this Society about 27 years since upon the occasion of the carrying the pendulum clocks to sea and at two other times since, though I have had the ill fortune not to be heard, and I conceive there are some present that may very well remember and do know that Mr Newton did not send up that addition to his book till some weeks after I had read and showed the experiments and demonstration thereof in this place and had answered the reproachful letter of Dr Wallis from Oxford. However I am well pleased to find that the truth will at length prevail when men have laid aside their prepossessions and prejudices. And as that hath found approvers in the world and those thinking men too, so I doubt not but that divers other discoveries which I have here first made ( when they come to be well considered and examined ) be found not so unreasonable or extravagant as some would willingly make them.

... lean, bent and ugly man ...

References ( show )

- R S Westfall, Biography in Dictionary of Scientific Biography ( New York 1970 - 1990) . See THIS LINK .

- Biography in Encyclopaedia Britannica. http://www.britannica.com/biography/Robert-Hooke

- V I Arnol'd, Huygens and Barrow, Newton and Hooke. Pioneers in mathematical analysis and catastrophe theory from evolvents to quasicrystals ( Basel, 1990) .

- A N Bogolyubov, Robert Hooke 1635 - 1703 , Scientific-Biographic Literature 'Nauka' ( Moscow, 1984) .

- F F Centore, Robert Hooke's contributions to mechanics : a study in seventeenth century natural philosophy ( The Hague, 1970) .

- J G Crowther, Founders of British science : John Wilkins, Robert Boyle, John Ray, Christopher Wren, Robert Hooke, Isaac Newton ( London, 1960) .

- W Derham ( ed. ) , The Philosophical Works of Dr Robert Hooke ( London, 1726) .

- M Espinasse, Robert Hooke ( London, 1956) .

- M Hunter and S Schaffer ( eds. ) , Robert Hooke : new studies ( Eoodbridge, 1989) .

- R Nichols, The Diaries of Robert Hooke, The Leonardo of London, 1635 - 1703 ( Lewes, 1994) .

- R Waller ( ed. ) , The Postumous Works of Dr Robert Hooke ( London, 1705) .

- E N da C Andrade, Robert Hooke, Proc. Roy. Soc. London 201 A (1950) , 439 - 473 .

- J A Bennett, Robert Hooke as Mechanic and Natural Philosopher, Notes and Records of the Royal Society 35 (1980 - 1981) , 33 - 48 .

- J A Bennett, Hooke and Wren and the system of the world : some points towards an historical account, British J. Hist. Sci. 8 (1975) , 32 - 61 .

- A N Bogolyubov, Robert Hooke as a teacher of mathematics ( Russian ) , Istor.-Mat. Issled. 32 - 33 (1990) , 373 - 383 .

- C Dilworth, Boyle, Hooke and Newton : some aspects of scientific collaboration, Rend. Accad. Naz. Sci. XL Mem. Sci. Fis. Natur. (5) 9 (1985) , 329 - 331 .

- W N Edwards, Robert Hooke as a geologist and evolutionist, Nature 137 (1936) , 96 - 97 .

- M E Ehrlich, Mechanism and Activity in the Scientific Revolution : The Case of Robert Hooke, Annals of Science 52 (1995) , 127 - 152 .

- H Erlichson, Newton and Hooke on centripetal force motion, Centaurus 35 (1) (1992) , 46 - 63 .

- S R Filonovich, Astronomy in the work of Robert Hooke ( on the occasion of the 350 th anniversary of his birth ) ( Russian ) , Istor.-Astronom. Issled. 18 (1986) , 259 - 290 .

- O Gal, Producing knowledge in the workshop : Hooke's 'inflection' from optics to planetary motion, Stud. Hist. Philos. Sci. 27 (2) (1996) , 181 - 205 .

- D C Goodman, Robert Hooke, 1635 - 1703 , in Late seventeenth century scientists ( Oxford, 1969) , 132 - 157 .

- P Gouk, The Role of Acoustics and Music Theory in the Scientific Work of Robert Hooke, Annals of Science 37 (1980) , 573 - 605 .

- A R Hall, Robert Hooke and horology, Notes and Records Roy. Soc. London 8 (1) (1950 - 51) , 167 - 177 .

- A R Hall, Beyond the fringe : diffraction as seen by Grimaldi, Fabri, Hooke and Newton, Notes and Records Roy. Soc. London 44 (1) (1990) , 13 - 23 .

- A R Hall, Two unpublished lectures of Robert Hooke, Isis 42 (1951) , 219 - 230 .

- A R Hall, Horology and criticism : Robert Hooke, in Studia Copernicana 16 - Science and history ( Ossolinskich, 1978) , 261 - 281 .

- M Hesse, Hooke's philosophical algebra, Isis 57 (1966) , 67 - 83 .

- M Hesse, Hooke's vibration theory and the isochrony of springs, Isis 57 (1966) , 433 - 441 .

- P E B Jourdain, Robert Hooke as a precursor of Newton, Monist 23 (1913) , 353 - 385 .

- J C Kassler and D R Oldroyd, Robert Hooke's Trinity College 'Musick Scripts', his music theory and the role of music in his cosmology, Ann. of Sci. 40 (6) (1983) , 559 - 595 .

- V S Kirsanov, The correspondence between Isaac Newton and Robert Hooke : 1679 - 80 ( Russian ) , Voprosy Istor. Estestvoznan. i Tekhn. (4) (1996) , 3 - 39 , 173 .

- A Koyré, A note on Robert Hooke, Isis 41 (1950) , 195 - 196 .

- A Koyré, An unpublished letter of Robert Hooke to Isaac Newton, Isis 43 (1952) , 312 - 337 .

- R Lehti, Newton's road to classical dynamics. II. Robert Hooke's influence on Newton's dynamics ( Finnish ) , Arkhimedes 39 (1) (1987) , 18 - 51 .

- J Lohne, Hooke versus Newton : An analysis of the documents in the case on free fall and planetary motion, Centaurus 7 (1960) , 6 - 52 .

- W S Middleton, The Medical Aspect of Robert Hooke, Annals of Medical History 9 (1927) , 227 - 43 .

- H Nakajima, Two kinds of modification theory of light : some new observations on the Newton-Hooke controversy of 1672 concerning the nature of light, Ann. of Sci. 41 (3) (1984) 261 - 278 .

- M Nauenberg, Hooke, orbital dynamics and Newton's Principia, American Journal of Physics 62 (1994) , 331 - 350 .

- L D Patterson, Hooke's gravitation theory and its influence on Newton I, Isis 40 (1949) , 327 - 341 .

- L D Patterson, Hooke's gravitation theory and its influence on Newton II, Isis 41 (1950) , 23 - 45 .

- A P Rossiter, The first English geologist, Durham University Journal 27 (1935) , 172 - 181 .

- E G R Taylor, Robert Hooke and the Cartographical Projects of the Late Seventeenth Century, Geographical Journal 9 (1937) , 529 - 540 .

- R S Westfall, Hooke and the law of universal gravitation, British J. Hist. Sci. 3 (1967) , 245 - 261 .

- R S Westfall, The development of Newton's theory of colour, Isis 53 (1962) , 339 - 358 .

Additional Resources ( show )

Other pages about Robert Hooke:

- Aubrey's Brief Lives

- Multiple entries in The Mathematical Gazetteer of the British Isles ,

- Astronomy: The Dynamics of the Solar System

Other websites about Robert Hooke:

- Dictionary of Scientific Biography

- Dictionary of National Biography

- Encyclopaedia Britannica

- Robert Hooke home page

- The Galileo Project,

- Sci Hi blog

- Robert Hooke's London

- Mathematical Genealogy Project

- zbMATH entry

Honours ( show )

Honours awarded to Robert Hooke

- Fellow of the Royal Society 1663

- Lunar features Crater Hooke

- Biography in Aubrey's Brief Lives

- Lunar features Crater Hooke on Mars

- Popular biographies list Number 42

Cross-references ( show )

- History Topics: A history of the calculus

- History Topics: A history of time: Classical time

- History Topics: English attack on the Longitude Problem

- History Topics: Light through the ages: Ancient Greece to Maxwell

- History Topics: London Coffee houses and mathematics

- History Topics: Mathematics and Architecture

- History Topics: Orbits and gravitation

- History Topics: Science in the 17 th century: From Europe to St Andrews

- History Topics: The development of the 'black hole' concept

- Societies: London Royal Society

- Other: 10th April

- Other: 15th February

- Other: 19th February

- Other: 2009 Most popular biographies

- Other: 21st January

- Other: 25th August

- Other: 3rd June

- Other: Earliest Known Uses of Some of the Words of Mathematics (E)

- Other: Jeff Miller's postage stamps

- Other: London Learned Societies

- Other: London Miscellaneous

- Other: London Museums

- Other: London Schools

- Other: London Scientific Institutions

- Other: London individuals H-M

- Other: London individuals S-Z

- Other: Most popular biographies – 2024

- Other: Other London Institutions outside the centre

- Other: Oxford Institutions and Colleges

- Other: Oxford individuals

- Other: Popular biographies 2018

- Other: The Dynamics of the Solar System

History of the Cell: Discovering the Cell

Initially discovered by Robert Hooke in 1665, the cell has a rich and interesting history that has ultimately given way to many of today’s scientific advancements.

Biology, Genetics

Loading ...

Although they are externally very different, internally, an elephant, a sunflower, and an amoeba are all made of the same building blocks. From the single cells that make up the most basic organisms to the trillions of cells that constitute the complex structure of the human body, each and every living being on Earth is comprised of cells . This idea, part of the cell theory, is one of the central tenants of biology . Cell theory also states that cells are the basic functional unit of living organisms and that all cells come from other cells . Although this knowledge is foundational today, scientists did not always know about cells .

The discovery of the cell would not have been possible if not for advancements to the microscope . Interested in learning more about the microscopic world, scientist Robert Hooke improved the design of the existing compound microscope in 1665. His microscope used three lenses and a stage light, which illuminated and enlarged the specimens. These advancements allowed Hooke to see something wondrous when he placed a piece of cork under the microscope . Hooke detailed his observations of this tiny and previously unseen world in his book, Micrographia . To him, the cork looked as if it was made of tiny pores, which he came to call “cells” because they reminded him of the cells in a monastery.

In observing the cork’s cells, Hooke noted in Micrographia that, “I could exceedingly plainly perceive it to be all perforated and porous, much like a Honey-comb, but that the pores of it were not regular… these pores, or cells,…were indeed the first microscopical pores I ever saw, and perhaps, that were ever seen, for I had not met with any Writer or Person, that had made any mention of them before this…”

Not long after Hooke’s discovery, Dutch scientist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek detected other hidden, minuscule organisms— bacteria and protozoa . It was unsurprising that van Leeuwenhoek would make such a discovery. He was a master microscope maker and perfected the design of the simple microscope (which only had a single lens), enabling it to magnify an object by around two hundred to three hundred times its original size. What van Leeuwenhoek saw with these microscopes was bacteria and protozoa , but he called these tiny creatures “animalcules.”

Van Leeuwenhoek became fascinated. He went on to be the first to observe and describe spermatozoa in 1677. He even took a look at the plaque between his teeth under the microscope. In a letter to the Royal Society, he wrote, "I then most always saw, with great wonder, that in the said matter there were many very little living animalcules, very prettily a-moving.”

In the nineteenth century, biologists began taking a closer look at both animal and plant tissues, perfecting cell theory. Scientists could readily tell that plants were completely made up of cells due to their cell wall. However, this was not so obvious for animal cells, which lack a cell wall. Many scientists believed that animals were made of “globules.”

German scientists Theodore Schwann and Mattias Schleiden studied cells of animals and plants respectively. These scientists identified key differences between the two cell types and put forth the idea that cells were the fundamental units of both plants and animals.

However, Schwann and Schleiden misunderstood how cells grow. Schleiden believed that cells were “seeded” by the nucleus and grew from there. Similarly, Schwann claimed that animal cells “crystalized” from the material between other cells. Eventually, other scientists began to uncover the truth. Another piece of the cell theory puzzle was identified by Rudolf Virchow in 1855, who stated that all cells are generated by existing cells.

At the turn of the century, attention began to shift toward cytogenetics, which aimed to link the study of cells to the study of genetics. In the 1880s, Walter Sutton and Theodor Boveri were responsible for identifying the chromosome as the hub for heredity —forever linking genetics and cytology. Later discoveries further confirmed and solidified the role of the cell in heredity , such as James Watson and Francis Crick’s studies on the structure of DNA .

The discovery of the cell continued to impact science one hundred years later, with the discovery of stem cells , the undifferentiated cells that have yet to develop into more specialized cells . Scientists began deriving embryonic stem cells from mice in the 1980s, and in 1998, James Thomson isolated human embryonic stem cells and developed cell lines. His work was then published in an article in the journal Science . It was later discovered that adult tissues, usually skin, could be reprogrammed into stem cells and then form other cell types. These cells are known as induced pluripotent stem cells . Stem cells are now used to treat many conditions such as Alzheimer’s and heart disease.

The discovery of the cell has had a far greater impact on science than Hooke could have ever dreamed in 1665. In addition to giving us a fundamental understanding of the building blocks of all living organisms, the discovery of the cell has led to advances in medical technology and treatment. Today, scientists are working on personalized medicine, which would allow us to grow stem cells from our very own cells and then use them to understand disease processes. All of this and more grew from a single observation of the cell in a cork.

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Production Managers

Program specialists, last updated.

October 19, 2023

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

Robert Hooke: English scientist who discovered the cell

Robert Hooke was the English polymath who discovered the building blocks of all life.

- Physics and mechanics discoveries

Microscope and cell theory

Additional resources.

Robert Hooke was a 17th-century scientist who contributed to our knowledge of mathematics , mechanics, biology and astronomy . Hooke is perhaps most famous for discovering the living cell, but he is also well known for finding the law that governs the stretch of elastic material, improving weather measurement devices and discovering new celestial objects.

Hooke was born in 1635 on the Isle of Wight, an island off the southern coast of England. As a child, he was too sickly to attend school, as he suffered from a severe case of smallpox, according to Oxford Academic . Instead, he spent much of his childhood drawing in his bedroom, according to Historic UK . However, even at a young age, Hooke showed a strong mechanical ability, building a clock out of wood and a toy boat with cannons that fired, according to RobertHooke.org.uk .

In his teens, after his father died, Hooke enrolled at Westminster School in London. There, he discovered that his talents extended beyond painting; he excelled in mathematics , mechanics and languages, according to Biography.com .

Related: Cells by the numbers: Facts about the building blocks of life

In 1653, at the age of 18, Hooke began studying at Christ Church College at the University of Oxford, where he spent much of his time building telescopes.

Hooke's contributions to physics and mechanics

One of Hooke's greatest discoveries was that of the fifth star in the trapezium of the Orion constellation, in 1664. During his observations of the night sky, he analyzed planets and was the first to theorize that Jupiter rotates on an axis. Later, in the 19th century, the sketches he made of Mars were used to calculate its rate of rotation, according to Britannica.com .

Hooke was fascinated by how instruments could manipulate light to allow him to see both near and far. Using this interest, Hooke became one of the first scientists to build a working Gregorian telescope, which consists of two concave mirrors inside a brass barrel. Light enters the telescope and travels to the largest of these mirrors at the end of the barrel. The light is reflected back in the opposite direction, towards the smaller mirror, which focuses the light through the eyepiece lens. This was the second successful reflecting telescope designed by Scottish mathematician James Gregory. Gregory was unable to make his telescope work, but 10 years later, Hooke achieved this task for him, according to the History of Science Museum

After Sir Isaac Newton published some of his findings on the law of gravity , Hooke confronted him, demanding some credit. Newton's new law had explained how "all celestial bodies have an attraction or gravitating power toward their own centers," but Hooke had written these words decades earlier, according to Science Focus magazine . Newton denied any plagiarism, but it is widely believed that Newton was able to turn Hooke's accurate description into a mathematical model.

In 1660, Hooke discovered a physical law that would later be named after him. Hooke's law states that the force needed to extend or compress a spring is proportional to the distance it is stretched.

In 1662, Hooke was given the role of Curator of Experiments for the Royal Society , which meant he devised the experiments performed in the society's weekly meetings, according to RobertHooke.org.uk . Today, this is the oldest independent scientific organization, and Hooke's broad scientific interests helped set the society's trajectory during its early years.

In 1663, he invented or improved the five main meteorological instruments: the barometer, thermometer, hydroscope, rain gauge and wind gauge, according to ThoughtCo.com .

This article is brought to you by How It Works .

How It Works is the action-packed magazine that's bursting with exciting information about the latest advances in science and technology, featuring everything you need to know about how the world around you — and the universe — works.

The barometer invented by Hooke was the wheel barometer, which was used to measure the air's atmospheric pressure. This barometer consisted of a curved tube, filled with mercury, and a ball that floated on top. The floating ball was attached to a pointer. The tube, filled with mercury, sat upside down on a small container of mercury. When the air pressure increased, the increased weight pushing down on the mercury forced more mercury into the tube and caused the ball to move upward. This changed the measurement selected by the pointer, according to ThoughtCo.com .

Hooke went on to develop his own versions of wind and rain gauges. His tipping-bucket rain gauge emptied itself when filled with rain. The number of times the bucket became unbalanced and tipped was recorded to measure the cumulative volume of rainwater over a given time. Hooke's wind gauge was a reinvention of the original; as the wind speed changed, so did the position of an attached mobile panel. To improve the thermometer, Hooke added further measurements, including the freezing point of water, according to Royal Society Publishing .

Hooke's most famous work was his 1665 discovery of the living cell. Though scientists had invented the microscope decades earlier, Hooke's innovation dramatically improved the technology. He placed three mirrors in sequence to magnify the images and added a light for better viewing. The intricate internal structure of living things emerged in incredible detail under his more powerful compound microscope, according to National Geographic .

Hooke detailed many of his observations in his 1665 book "Micrographia," which was filled with intricate sketches of the tiny world he saw — everything from six-sided "snowflakes" floating atop frozen urine to mold spores, which, up close, looked like tulips waving in the wind.

Hooke was also the first to examine different fossil types with a microscope, proposing in "Micrographia" that fossils form when "the Shells of certain Shel-fishes, which, either by some Deluge, Inundation, earthquake, or some such other means, came to be thrown to that place, and there to be fill'd with some kind of Mud or Clay, or petrifying Water, or some other substance."

His microscope observations also revealed how mosquitoes and lice suck blood.

In 1666, after the Great Fire of London destroyed much of the city, Hooke was given the opportunity to try his hand at architecture, according to Royal Museums Greenwich . Hooke and Sir Christopher Wren, who was also a scientist, designed a monument to commemorate the fire. The two scientist-architects decided to add scientific elements to the 202-foot-tall (61 meters) monument, which was erected between 1671 and 1677. For instance, Hooke included an underground laboratory where he could conduct many of his science experiments, while the central passage was built to house a large telescope, according to the BBC . This laboratory remains below the monument today, although it is usually inaccessible to the public and its entrance stays covered.

Hooke never married; he died, after years of declining health, in 1703.

Scientists continue to be inspired by, and benefit from, Hooke's findings as they delve further into the microscopic world he revealed. As Hooke wrote in "Micrographia," "By the means of telescopes, there is nothing so far distant but may be represented to our view; and by the help of microscopes, there is nothing so small as to escape our inquiry."

- Check out a digitized version of " Micrographia " provided by the Royal Society

- Learn more about Hooke's life and contributions at RobertHooke.org.uk .

- Book recommendation: " The Curious Life of Robert Hooke: The Man Who Measured London " (Harper Perennial, 2005), by Lisa Jardine.

This article was adapted from a previous version published in How It Works magazine, a Future Ltd. publication. To learn more about the wonders of the natural world, subscribe to How It Works magazine.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ailsa is a staff writer for How It Works magazine, where she writes science, technology, history, space and environment features. Based in the U.K., she graduated from the University of Stirling with a BA (Hons) journalism degree. Previously, Ailsa has written for Cardiff Times magazine, Psychology Now and numerous science bookazines. Ailsa's interest in the environment also lies outside of writing, as she has worked alongside Operation Wallacea conducting rainforest and ocean conservation research.

Largest 3D map of our universe could 'turn cosmology upside down'

Avi Wigderson wins $1 million Turing Award for using randomness to change computer science

World's fastest camera captures images at 156 trillion frames per second

Most Popular

- 2 No, you didn't see a solar flare during the total eclipse — but you may have seen something just as special

- 3 'Gambling with your life': Experts weigh in on dangers of the Wim Hof method

- 4 Eclipse from space: See the moon's shadow race across North America at 1,500 mph in epic satellite footage

- 5 Superfast drone fitted with new 'rotating detonation rocket engine' approaches the speed of sound

- 2 Cancer patients can now be 'matched' to best treatment with DNA and lab-dish experiments

- 3 Space photo of the week: NASA spots enormous pink 'flames' during total solar eclipse. What are they?

- 4 Ancient Indigenous lineage of Blackfoot Confederacy goes back 18,000 years to last ice age, DNA reveals

Robert Hooke: The ‘English Leonardo’ who was a 17th-century scientific superstar

Chancellor's Professor of Medicine, Liberal Arts, and Philanthropy, Indiana University

Disclosure statement

Richard Gunderman does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Indiana University provides funding as a member of The Conversation US.

View all partners

Considering his accomplishments, it’s a surprise that Robert Hooke isn’t more renowned. As a physician, I especially esteem him as the person who identified biology’s most essential unit, the cell.

Like Leonardo da Vinci , Hooke excelled in an incredible array of fields. The remarkable range of his achievements throughout the 1600s encompassed pneumatics, microscopy, mechanics, astronomy and even civil engineering and architecture. Yet this “ English Leonardo ” – well-known in his time – slipped into relative obscurity for several centuries.

His life and times

Hooke’s life is a rags-to-riches tale. Born in 1635, he was educated at home by his clergyman father. Orphaned at 13 with a meager inheritance, Hooke’s artistic talents landed him scholarships to Westminster School and later Oxford University. There he formed relationships with a variety of important people, most notably Robert Boyle . Hooke became the laboratory assistant of this great chemist – the formulator of Boyle’s law, which describes the inverse relation between the pressure and volume of gases.

Unlike his associates, Hooke was not a man of independent means, and he soon took a paying position as “curator of experiments” at the newly formed Royal Society , making him England’s first salaried scientific researcher. Hooke soon became a fellow of the Royal Society and was appointed to a professorship at Gresham College.

Never marrying, he dwelt the rest of his life in rooms near the Royal Society’s meeting place. This placed him at the epicenter of one of the most important epochs in the history of science, epitomized by the publication of Isaac Newton’s “ Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy .”

Experiments and innovations

For millennia before Hooke, people had regarded air, along with fire, water and earth, as one of the four elemental substances that filled the world, leaving no empty spaces. Working with Boyle, Hooke developed a vacuum pump that could empty space. In a vessel so evacuated, a candle couldn’t burn, and a clapping bell was silent, proving that air is necessary for combustion and conducting sound.

Moreover, Hooke showed that air could be expanded and compressed. He also performed foundational experiments on the relationship between air and the process of respiration in living organisms. And he laid the groundwork for thermodynamics, by suggesting that particles in matter move faster as they heat up.

Hooke’s most famous work is his beautifully illustrated “ Micrographia ,” published in 1665. The microscope had been invented 30 years before his birth. Hooke vaulted the technology forward, using an oil lamp as a light source and a water lens to focus its beams in order to enhance visualization.

He showed that the realm of the very small is as rich and complex and the one that meets the naked eye. Inspecting the structure of cork through his instrument, he named the units he saw cells, after the rooms of monks. Biologists now know that a human body contains approximately 40 trillion of them. From his microscope work, Hooke also developed a wave theory of light.

Hooke pondered some of the biggest biological questions as well. He hypothesized that the presence of fossilized fish in mountainous areas meant they had once been under water. His study of fossils led him to conclude that the Earth has been inhabited by many extinct species.

Hooke’s experiments with mechanical springs led to the formulation of Hooke’s Law , which states that the tension or compression of a spring is proportional to the force applied to it. Physicists now know that this law applies not only to springs but also to a variety of solid elastic bodies, such as manometers, which are used to measure pressure.

These same investigations also enabled him to invent the spring-powered balance watch , which would become a favorite means of keeping time for centuries. Hooke foresaw that with a precise timepiece, oceangoing sailors could find their longitude.

As an astronomer , Hooke suggested that the planet Jupiter rotates, described the center of gravity of the Earth and Moon, illustrated lunar craters and speculated on their origin, discovered a double star and illustrated the Pleiades star cluster.

At a more theoretical level, Hooke also described gravity as the force that pulls celestial bodies together, relating in a 1679 letter to Newton a version of the inverse-square law of gravitational force. When seven years later Newton published his great work “Mathematical Principles,” Hooke concluded incorrectly that Newton – who had already been at work on it at the time of their correspondence – had slighted him.

Contributions to his city

The great fire of London in 1666 presented another opportunity for Hooke to shine. Unlike many contemporaries, he refused to profit dishonestly in the aftermath of the disaster by taking bribes as people worked to rebuild. As surveyor of the city , he collaborated with the renowned architect Christopher Wren to create a monument to the fire .

He also designed a number of great buildings , including Bethlem Hospital (known as Bedlam), the Royal Greenwich Observatory and the Royal College of Physicians. It was in large part through his architectural work that Hooke made his fortune, though he never veered from the frugal habits he developed early in life. Hooke even proposed recreating London’s streets on a grid pattern. Though unsuccessful, his idea was subsequently incorporated in cities such as Liverpool and Washington, D.C.

Surveying the range and depth of Hooke’s contributions, it’s difficult to believe that one person could have accomplished so much in 67 years. Unfortunately, his sometimes rancorous disputes with the likes of Newton over scientific priority contributed to his comparative neglect by science historians , and today we lack any contemporary likeness of him. His birthday is a good time to give him his due as one of the world’s all-time great instrument makers, experimentalists and polymaths.

[ Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter . ]

- History of science

- Royal Society

- Robert Hooke

Associate Professor, Occupational Therapy

GRAINS RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION CHAIRPERSON

Technical Skills Laboratory Officer

Faculty of Law - Academic Appointment Opportunities

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

- Previous Article

- Next Article

The Forgotten Genius: The Biography of Robert Hooke 1635–1703

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Reprints and Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Peter Dear; The Forgotten Genius: The Biography of Robert Hooke 1635–1703 . Physics Today 1 February 2005; 58 (2): 66–68. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2405556

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

The Forgotten Genius: The Biography of Robert Hooke 1635–1703 , Stephen Inwood MacAdam/Cage , San Francisco , 2003 . $28.50 ( 482 pp.). ISBN 1-931561-56-7 Google Scholar

Robert Hooke has never really been forgotten. But he is usually remembered only as a peripheral figure of the scientific revolution, famous for his controversies with the great Isaac Newton or, especially in Great Britain, for being a minor colleague of Christopher Wren, the architect of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London who also rebuilt the city after the great fire of 1666. The Curious Life of Robert Hooke: The Man Who Measured London by Lisa Jardine and The Forgotten Genius: The Biography of Robert Hooke 1635–1703 by Stephen Inwood are both biographies by British authors, and Jardine’s book in particular reminds us of Hooke’s major, albeit overshadowed, role in that astonishing rebuilding effort. He would have been much better remembered had he received the kind of hagiographical treatment after his death that so benefited Wren.

Hooke was a founding member of the Royal Society when it received its final royal authorization in 1663. He was its lifeblood for many years, the one who made it much more than just a talking shop. He was appointed the society’s first “curator of experiments,” charged with producing experimental demonstrations for the group’s discussions at each weekly meeting. Hooke received the post after being Robert Boyle’s experimental technician in Oxford for several years; he built Boyle’s air pumps and probably was responsible for the initial formulation of Boyle’s law. (Hooke’s law, of course, is itself well known to engineers and physicists.)

Hooke published on many topics and left a large collection of manuscripts on many others, including geology, astronomy, watchmaking, gravity, chemistry, mechanics, and microscopy. His interest in microscopy in particular produced his greatest lasting legacy: Micrographia, or Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies made by Magnifying Glasses of 1665. That book is perhaps best known for its huge fold-out engraving of a magnified flea, an image that is frequently reproduced without attribution. The magnificent illustrations, some perhaps due to Hooke’s friend and colleague Wren, ensured the book’s success. It was the book’s textual contents, however, that laid the foundation for Hooke’s contemporary reputation. His discussion of the nature of light and color caught the attention of the young Newton—Hooke first described “Newton’s rings” in Micrographia —and set the stage for the controversy between him and Newton in the 1670s after Newton published his own ideas on the same subject.

Readers interested in learning more about Hooke and this controversy with Newton, and about Micrographia , may be disappointed by Jardine’s book. Jardine evidently intended that her book join the ranks of the countless “The Man Who …” books whose many subjects “changed the world,” following the example of the 1995 biography Longitude: The True Story of a Lone Genius Who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of His Time (Walker, 1995) by Dava Sobel. Although Jardine begins with a theme-setting account of Hooke’s battle for credit when Newton’s Principia was published, her narrative provides no discussion of the optical controversy between the two men and, more surprisingly, no real discussion of Micrographia and its contents. Inwood’s The Forgotten Genius , on the other hand, dedicates several pages to each of the famous controversies and an entire chapter (although of modest length) to the Micrographia. His book discusses many of Hooke’s scientific and technical innovations, including all of the major ones, whereas Jardine often mentions them only in passing.

The focus of Jardine’s book is on Hooke as a social being who moves around London consorting with people of many different sorts and social classes, from lords to laborers. Even before his intensive work on the surveying and rebuilding of London after the fire, Hooke appears in a variety of settings, from bookshops to the court of Charles II. He is most typically seen in coffeehouses, a new feature of London life in the 1660s that Hooke took to like a duck to water, where he could meet with Royal Society colleagues, mathematical instrument makers, and sailors. His technical and intellectual capacities, combined with his social skills, recommended him to the City of London as a practical surveyor. The appointment, together with his work for Wren’s architectural firm, made him the single most significant figure in the grand project for rebuilding London, an enterprise whose swiftness amazed foreign visitors. It is in Jardine’s accounts of this period of Hooke’s life, rather than in her accounts of his scientific labors, that Hooke really comes alive.

A feature that recommends Hooke to biographers is the existence of his famous diaries, which both Jardine and Inwood use well. The diaries sketch out the business of Hooke’s everyday life, the breadth of his social acquaintance, and the details of his domestic existence. Jardine and Inwood both discuss his constant concerns with his health and with medical remedies, few of which seemed to have done much good. The diaries are also the source for what historians know about his sex life, without which no biography is nowadays complete.

Jardine’s book is lavishly illustrated and is more appealing to the eye. Inwood’s, by contrast, is comfortable and old-fashioned and takes its biographical task seriously, proceeding largely chronologically and trying not to leave out important events in the course of Hooke’s life. Jardine attempts more vigorously to develop themes, such as the long-lasting importance of Hooke’s childhood in the Isle of Wight. His early years on the island seem to have shaped his later geological ideas and provided social connections (including sources of servants) that continued to be important to him until the end.

Anyone seriously interested in Hooke has, in addition to Jardine’s and Inwood’s books, plenty of specialized scholarly work available. The layperson who wants to learn something about Hooke’s tremendously inventive scientific career would do well to start with Inwood, whereas the reader who is interested in the social and cultural life of later 17th-century London will profit much from Jardine’s colorful and insightful book.

Citing articles via

- Online ISSN 1945-0699

- Print ISSN 0031-9228

- For Researchers

- For Librarians

- For Advertisers

- Our Publishing Partners

- Physics Today

- Conference Proceedings

- Special Topics

pubs.aip.org

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

Connect with AIP Publishing

This feature is available to subscribers only.

Sign In or Create an Account

Accessibility links

- Skip to content

- Skip to local navigation

- Skip to bbc.co.uk navigation

- Skip to bbc.co.uk search

- Accessibility Help

British History in-depth

- Ancient History

- British History

- Historic Figures

- Family History

- Hands on History

- History for Kids

- On This Day

Robert Hooke, Natural Philosopher

By Rod Beavon Last updated 2011-02-17

Although a portrait of Robert Hooke was seen at the Royal Society in 1710, none exists now apart from the memorial window at St Helen's Bishopsgate, which is merely a formulaic portrait. The absence of image is also figuratively true - Hooke has been unjustly obscured by his contemporaries.

On this page

Hooke and his contemporaries, science and technology, hooke the astronomer, hooke and newton, hooke the architect, find out more, page options.

- Print this page

Most who have studied some science will have come across Hooke's Law, that the extension of a spring is proportional to the applied force, but few will know of his theory of combustion or that his Micrographia was the first book on microscopy; that his astronomical observations were some of the best seen at the time and that there is a Hooke crater on the moon, named in his honour; that he contributed to knowledge of respiration, insect flight and the properties of gases; that his work on gravitation preceded Newton's; that he invented the universal joint and the anchor escapement in clocks and numerous other mechanical devices; and that he was an architect of distinction and a Surveyor for the City of London after the Great Fire. Everyone knows the names of Newton and Wren, but Hooke was as distinguished and deserves similar recognition. That he lacks such recognition stems from a mixture of temperament and bad luck.

Everyone knows the names of Newton and Wren, but Hooke was as distinguished and deserves similar recognition.

In 1648 Hooke entered Westminster School under Dr Richard Busby, going on to Christ Church Oxford in 1653. It was here that he met some of those who would be lifelong companions in science and in the Royal Society. Many have become legendary: among his contemporaries were Robert Boyle, aristocrat and experimentalist; the mathematician John Wilkins; William Petty, economist and inventor; the astronomers Jeremiah Horrocks of Liverpool, John Flamsteed and Edmond Halley (the first two Astronomers Royal) and Christopher Wren, who was Savilian Professor of Astronomy at Oxford (1661) before he became more famous as an architect. Add to this Newton, the French astronomer Cassini, Christiaan Huygens, the patronage of King Charles II - and the legacy of Kepler, Galileo and Tycho Brahe, all of who had died in the first half of the 17th century - and Hooke's scientific environment can be seen to be rich indeed.

Hooke understood very well that although technology can progress without science, science needs technology...

Hooke held three appointments of considerable significance. From 1662 he was appointed Curator of Experiments at the newly formed Royal Society; his task was '..to furnish the Society [once a week] with three or four considerable experiments...', so it is as well that ideas came to him very quickly. As a result he seldom worked out his researches to their fullest extent before moving on, and indeed for some of them did not have the mathematical expertise. Other people, more focused, often developed the work to a point where they would justifiably receive credit for it. This frequently affronted Hooke since the indebtedness to his work was not always acknowledged, and he was often acerbically critical of the work of others. In this trait lay the origins of his major disagreements, with Newton and with Huygens, the latter over the invention of the spring balance escapement in clocks.

In 1664 Sir John Cutler founded a lectureship in mechanics for Hooke, though never actually paid him for these; and Hooke was appointed Gresham Professor of Geometry with rooms in Gresham College, in Bishopsgate Street, where he lived for the rest of his life.

The key to these was, as ever, the instrument. Hooke did much work on the development of the telescope, in particular recognising that the diameter of the object lens was crucial in capturing the maximum amount of light. In experiments to find the effect of lens diameter he invented the familiar iris diaphragm. He devised numerous ways of reducing the physical size of telescopes of long focal length, and machinery with which to move them. From this came his invention of the universal joint, found now in all motor vehicles.

The surface of planets particularly interested him; in 1664 and 1666 he reported spots as surface features on Jupiter; he claimed in later years to have measured the rotation of the planet, though the published credit belongs to Cassini. Micrographia (1665) contains detailed images of the lunar surface, observations which led to experiments in which Hooke attempted to explain how the craters could have been formed.

Hooke did much work on the development of the telescope...

Late 1664 saw the arrival of a prominent comet, observed thoroughly by Hooke. The measurement of angles is critical in astronomy since reliable theory or explanation relies on the measurement of the size of remote objects by the angle they subtend at the observer's eye. Hooke gave much thought and exercised much ingenuity in solving this problem, but his designs were sometimes beyond the manufacturing capabilities of the day. Flamsteed, the Astronomer Royal, was particularly frustrated by the failure of some of Hooke's instruments to live up to their promise. In 1677 a second comet appeared, at which time Hooke published his work and his speculations on their nature. In particular he showed that comets have a solid nucleus, and that they generate their own light.

Hooke corresponded with Newton regularly, but was not enough of a mathematician to formulate gravitation in the Newtonian sense. When Newton published his work on gravity in Principia, Hooke felt that he had not been given enough credit for his earlier work, a view that Newton never forgave. Newton wrote to Halley (who was paying for the publication of Principia) in strong terms over the argument. The relationship became more and more acrimonious, such that Hooke became secretive in his work and Newton is said to have delayed the publication of Opticks until after Hooke's death. It has even been suggested that Newton destroyed Hooke's portrait.

It has even been suggested that Newton destroyed Hooke's portrait.

Hooke's arguments with Newton, too powerful a man to be trifled with, and with Huygens has tended to overshadow his achievements and the general respect shown to his work, as well as his energy that was appreciated by those familiar with his company. There were also major disagreements with Oldenburg, President of the Royal Society, but even Wren, mild-mannered, found Oldenburg difficult.

At the same time as his astronomical observations were generating such interest, Hooke was immensely active as an architect. He was involved in the building of the Royal Observatory at Greenwich, but his role as Surveyor to the City of London after the Great Fire of 1666 is poorly appreciated. This is partly due to the fame of his partner Wren; partly because the works in which Hooke was largely involved were things such as boundary disputes and other planning matters, culverts, bridges - not major architectural works.

...his role as Surveyor to the City of London after the Great Fire of 1666 is poorly appreciated.

His radical plan for the rebuilding of the City was not adopted (possibly because of difficulties with boundaries) and does not survive. Of his major architecture only three examples remain: the Monument, usually attributed to Wren but certainly Hooke's; Ragley Hall in Warwickshire; and Willen Church in Buckinghamshire, built for Dr Busby. Neither of the latter two is in original condition. His building for the Royal College of Physicians and his magnificent Bethlehem Hospital (the 'Bedlam') were both demolished in the 19th century. Two statues from the Bedlam are in the Victoria and Albert Museum.

In the last year of his life Robert Hooke became blind and bedridden with swollen legs, suggestive of diabetes. His mind remained active. He died in his rooms at Gresham College, in Bishopsgate Street, on 3rd March 1703.

Robert Hooke and the Royal Society by Richard Nichols (Book Guild, 1999)

About the author

Rod Beavon was born and educated in Birmingham. After a time as a technician at the University of Birmingham Medical School and also in the Department of Physics, he spent three years as a school technician. He gained Grad.RIC and PhD from the University of Aston in Birmingham, and is now Head of Science at Westminster School in London. Has been involved in examining Chemistry at O, GCSE and A level since 1974, and is now Chief Examiner for Edexcel (London) Examinations in Chemistry.

«; More Civil War and Revolution

British history timeline.

- Explore the British History Timeline from the Neolithic to the present day

World War One Centenary

- Find out more about how the BBC is covering the World War One Centenary , and see the latest programmes and online content

Surviving the trenches

- Dan Snow asks why so many soldiers survived the trenches in WW1

Battle of Britain

- Explore the Battle of Britain with clips from BBC programmes

Search term:

BBC navigation

- Northern Ireland

- Full A-Z of BBC sites

You're using the Internet Explorer 6 browser to view the BBC website. Our site will work much better if you change to a more modern browser. It's free, quick and easy. Find out more about upgrading your browser here…

- Mobile site

- Terms of Use

- About the BBC

- Contact the BBC

- Parental Guidance

BBC © 2014 The BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites. Read more.

This page is best viewed in an up-to-date web browser with style sheets (CSS) enabled. While you will be able to view the content of this page in your current browser, you will not be able to get the full visual experience. Please consider upgrading your browser software or enabling style sheets (CSS) if you are able to do so.

Advertisement

Supported by

First Chapter

'The Curious Life of Robert Hooke'

- Share full article

By Lisa Jardine

- April 25, 2004

Many other things I long to be at, but I do extremely want time.

Hooke to Robert Boyle, 5 September 1667

On Saturday, 10 April 1697, a little less than five years before his death, Robert Hooke sat down with 'a small Pocket-Diary', specially purchased for the purpose, to write his autobiography:

I began this Day to write the History of my own Life, wherein I will comprize as many remarkable Passages, as I can now remember or collect out of such Memorials as I have kept in Writing, or are in the Registers of the Royal Society; together with all my Inventions, Experiments, Discoveries, Discourses, &c. which I have made, the time when, the manner how, and means by which, with the success and effect of them, together with the state of my Health, my Employments and Studies, my good or bad Fortune, my Friends and Enemies, &c. all which shall be the truth of Matter of Fact, so far as I can be inform'd by my Memorials or my own Memory, which Rule I resolve not to transgress.

And there, to all intents and purposes, he broke off. Was he perhaps interrupted? Did some urgent piece of business draw him away from his task? Even in these, his later years, there were (as we shall see) so many competing calls on his time. Hooke lived his entire working life 'over the shop' at Gresham College, and anyone - from the Curator of the Royal Society, Henry Hunt, to one or other of his fellow Gresham Professors - might stop by, even outside working hours, even on a Saturday, with a scientific or technical problem to discuss, a practical task to be undertaken, or simply to exchange gossip. Hooke put his autobiography to one side, and his ambition to leave posterity a full account of his brilliant, eventful life came to nothing.

Whatever the distraction, abandoning an undertaking when he had barely begun was entirely typical of Hooke. Although he embarked on everything he did with genuine enthusiasm and with the sincere intention of carrying the task through to completion, he habitually took on too much and promised to deliver more than it was sensible for him to commit himself to. Like many other important projects he proposed for himself - in scribbled lists, on loose sheets of paper, on the flyleafs of his books, in letters to colleagues and in his diary - this one foundered on that most mundane of obstacles: lack of time and opportunity to complete it.

All that Hooke's literary executor Richard Waller found among his old friend's personal papers to flesh out the skeletal autobiography was a few schematic paragraphs about Hooke's boyhood and early life. They begin:

Dr. Robert Hooke was Born at Freshwater, a Peninsula on the West side of the Isle of Wight, on the eighteenth of July, being Saturday, 1635, at twelve a Clock at Noon, and Christened the twenty sixth following by his own Father Minister of that Parish.

Tantalisingly sparse, these matter-of-fact jottings at least provide a starting point. For this discarded shard of an incomplete autobiography focuses immediately on two things which shaped Hooke's life - his Isle of Wight, seaside birthplace and his beloved father's clerical calling.

For a boy born in 1635, where you came from, and what your family's religious and political convictions were, mattered a great deal. Place of origin and parental calling were both deeply bound up with English civil war, the execution of an anointed king, and the ten-year exile of the head of the Anglican Church. However far Hooke rose above his modest beginnings, and however much he appeared to have put his origins and upbringing behind him, he carried permanently with him the mark of the dramatic political events of those early years.

Robert was the fourth and last child of John Hooke, curate of All Saints Church in Freshwater. His mother, Cecily Gyles, was from a local Isle of Wight family. Later, it would be members of her family who took care of Robert's affairs on the island, including the leasing and rent-collecting for his various properties there, after he had left and taken up permanent residence in London. Later still, they would squabble over who was to inherit his substantial legacies.

John Hooke had been on the island since at least 1610 (he had gentry relations near by in mainland Hampshire).

His first appointment (and appearance in the records) on the island was as a 'stand-in' curate that year for the church at St Helen's, near Brading, east of Newport, where there had been an unfilled vacancy since the previous year. There is no evidence that he was at this point an ordained minister, only that he was an intelligent, godly layman.

Around 1615, John Hooke joined the household of Sir John Oglander, a local gentleman remembered for his colourful personal diary of the civil war years and for his unswerving loyalty to King Charles I. The Oglanders were the most prominent family on the Isle of Wight. Sir John took in young John Hooke, by now the properly appointed curate of Oglander's local church, Brading, near the family home of Nunwell, to teach his eldest son George his Latin grammar:

Afterwards, I took Mr. Hooke, curate of Brading, into my house to teach him his accidence, in which my own care and pains were not wanting. Then not long after growing to more expenses, I procured Mr. Elgor, schoolmaster of Chichester School, to come to Newport and there I placed him, where he continued years.

John Hooke may have remained in Sir John's employment after George Oglander had moved on to the newly improved classroom instruction at Newport Grammar School, as this reminiscence implies, since it suggests additional expenditure for 'procuring' Mr Elgor ...

(Continues...)

Excerpted from The Curious Life of Robert Hooke by Lisa Jardine Excerpted by permission.

All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

What can fiction tell us about the apocalypse? The writer Ayana Mathis finds unexpected hope in novels of crisis by Ling Ma, Jenny Offill and Jesmyn Ward .

At 28, the poet Tayi Tibble has been hailed as the funny, fresh and immensely skilled voice of a generation in Māori writing .

Amid a surge in book bans, the most challenged books in the United States in 2023 continued to focus on the experiences of L.G.B.T.Q. people or explore themes of race.

Stephen King, who has dominated horror fiction for decades , published his first novel, “Carrie,” in 1974. Margaret Atwood explains the book’s enduring appeal .

Do you want to be a better reader? Here’s some helpful advice to show you how to get the most out of your literary endeavor .

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

December 1, 1954

Robert Hooke

This 17th-century Englishman was a prodigious scientist and inventor. To mention a few of his achievements, he made basic contributions to physics, chemistry, meteorology, geology, biology and astronomy

By E. N. da C. Andrade

Cambridge University Library Special Collections

Robert Hooke and his Micrographia

Folding plate of the flea from Hooke’s Micrographia (Keynes.S.7.21). The plate is almost half a metre long and over 35cm tall.

When Samuel Pepys strode through the City of London to visit his bookseller – a journey he made frequently – on 2 January 1665, he caught sight of a book which would change forever the way people thought about the world around them. In his diary that evening he wrote “[I] saw Hookes book of the Microscope, which is so pretty that I presently bespoke [ordered] it.” When he received his copy on 20 January he pronounced it “a most excellent piece…of which I am very proud.” The book was Robert Hooke’s Micrographia , the first English book dedicated entirely to the results of microscopic research. His pride presumably stemmed from the fact that the book had been printed by order of the Royal Society, of which he became a fellow just a few weeks later, rising to become its President in the 1680s. The book is now 350 years old and remains a cornerstone of English scientific thought. The Library’s two copies of the first edition will be on display in the Entrance Hall cases until 7 February, along with a selection of books from Hooke’s own extensive library.

Title page of Hooke’s Micrographia (Keynes.S.7.21), with the arms of the Royal Society and its motto, ‘nullius in verba’

Robert Hooke was born on the Isle of Wight in 1635 and was taught by his father John. After John’s death in 1648, Robert, expressing an interest in painting, moved to London and studied with Peter Lely, before gaining a place at Christ Church Oxford in 1653, where he became Robert Boyle’s assistant and counted Christopher Wren among his friends. He went on to become in 1663 one of the early members of the new Royal Society (founded by Charles II in 1660), and was from 1662 its first Curator of Experiments. Although works of biological microscopy had been published before, Hooke’s Micrographia was the most detailed and an impressive feat of engraving and book production. The order of the President of the Royal Society, which gave permission for Micrographia to be printed, is reproduced on the leaf facing the title and bears the date 23 November 1664. The book was evidently complete early in 1665, as we see from Samuel Pepys’ diary. The book began by pointing to the microscopic irregularities in those man-made things which, to the naked eye, appear to be perfection itself, like the tip of a needle or the blade of a razor. Hooke called them “rude mis-shapen things” and noted that “…when view’d with a Microscope, there is little else observable, but their deformity.” This contrasted with the products of nature, perfectly formed and suited to their purpose. The book exemplified the Royal Society’s motto, which appeared on its title page – nullius in verba (take nobody’s word for it) – in that everything it said was based on Hooke’s own observation. It remains an impressive book, still sought by collectors. The plates show just how impressive Hooke’s work must have been in 1665 and, even to our modern eyes, the detail of the engravings remains striking. Each image is based on a drawing by Hooke himself, a skilled draughtsman who has been called “England’s Leonardo.”

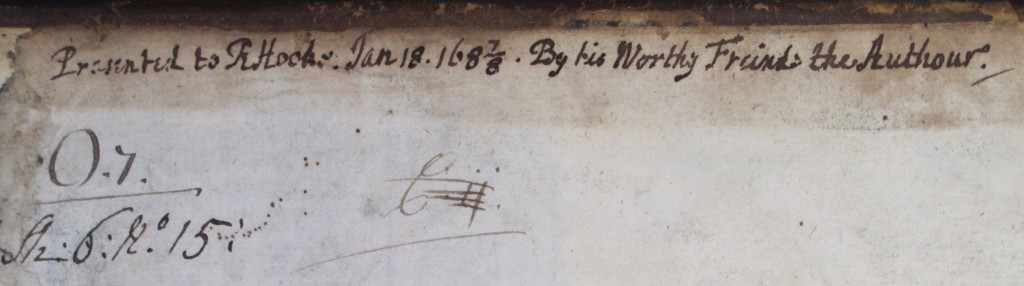

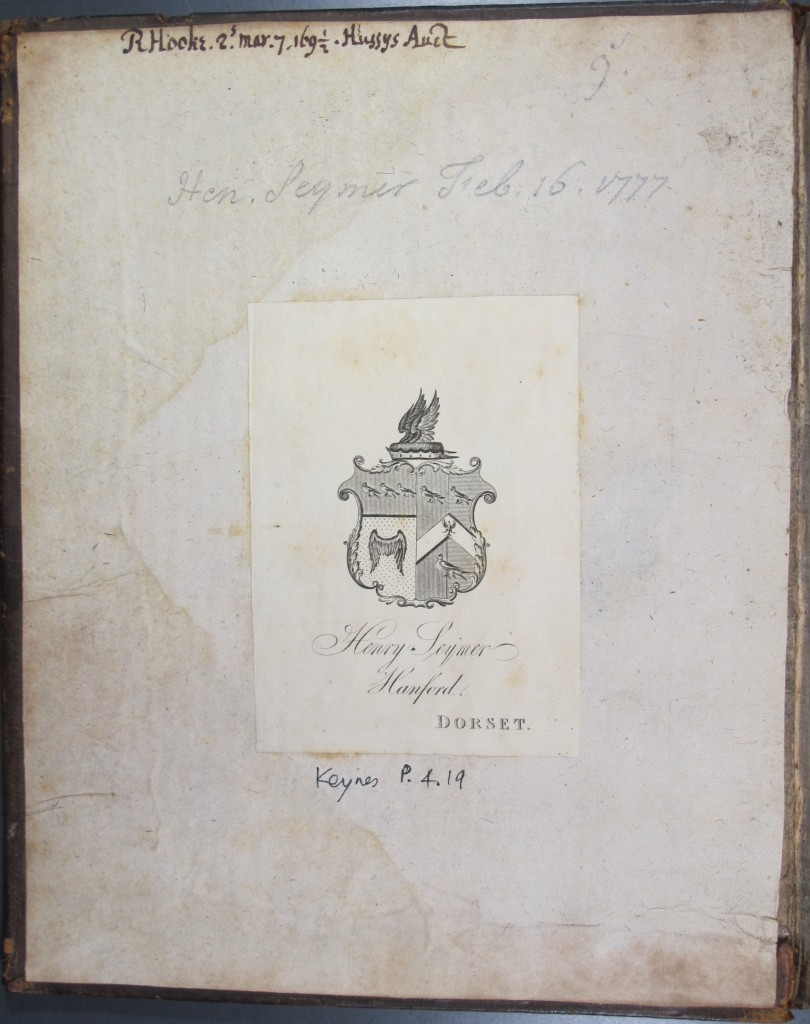

Inscription in Hooke’s hand recording the gift of this book (Perrault: Memoirs for a natural history of animals, London 1688) from “his worthy friend the authour” (the translator Alexander Pitfeild, also a fellow of the Royal Society) on 18 January 1687/8 (Keynes.Q.6.4)

The Library is lucky to possess two copies of the first edition of Micrographia , both of which appear in the exhibition. The first probably arrived soon after 1887, the year of the sale of the library of Freeman Roper, whose bookplate is pasted inside. It also bears the much earlier inscription (dated 1691) of one John Sharp, who may be responsible for the early annotations. The second copy came to us in 1982 with the 8000-volume library of the book-collector and surgeon Sir Geoffrey Keynes (1887–1982) – brother of the economist Maynard Keynes – who probably acquired it in 1947 from the sale of the Earl of Lonsdale’s possessions (it bears the Lonsdale book-label). Keynes collected the works of a number of scientific men, including the naturalist John Ray, the physician William Harvey and Hooke himself. Hooke himself had what was, for the late seventeenth century, a fairly substantial private library. Though it was dispersed at auction eight weeks after his death on 3 March 1703, we are lucky that the sale catalogue survives. It tells us that the library contained over 3000 volumes, probably representing more individual titles, of which around half were in Latin and 1000 in English. There was at least one incunable (Albumasar’s Introductio in Astronomiam , Venice, 1489) and he may have had two copies of Copernicus’ De revolutionibus of 1543, in addition to the first edition of Newton’s Principia mathematica (1687), which was of course published during Hooke’s lifetime. From surviving books once in Hooke’s possession it is evident that he took his collecting very seriously, taking care to inscribe his name or initials inside many volumes (as we see with the copy of Lister’s Historiæ animalium Angliæ ), along with information on where he purchased them and for how much. Some of Hooke’s diaries survive, and they too detail many of his purchases of books and his reading habits. The Library possesses at least three volumes from Hooke’s library, all included in the exhibition; one arrived in 1961 (Daniello Bartoli’s Del ghiaccio e della coagulatione : Rome, 1681) and two (Pitfeild and Lister) came with the collection of Sir Geoffrey Keynes in 1982.