50 Useful German Essay Words and Phrases

by fredo21

January 9, 2019

2 Comments

Essay-writing is in itself already a difficult endeavor. Now writing an essay in a foreign language like German ---that’s on a different plane of difficulty.

To make it easier for you, here in this article, we’ve compiled the most useful German essay phrases. Feel free to use these to add a dash of pizzazz into your essays. It will add just the right amount of flourish into your writing---enough to impress whoever comes across your work!

You can also download these phrases in PDF format by clicking the button below.

Now here’s your list!

What other German vocabulary list would you like to see featured here? Please feel free to leave a message in the comment section and we’ll try our best to accommodate your requests soon!

Once again, you can download your copy of the PDF by subscribing using the button below!

For an easier way to learn German vocabulary, check out German short stories for beginners!

A FUN AND EFFECTIVE WAY TO LEARN GERMAN

- 10 entertaining short stories about everyday themes

- Practice reading and listening with 90+ minutes of audio

- Learn 1,000+ new German vocabulary effortlessly!

About the author

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked

Thank you for the good writeup. It in fact was a amusement account it. Look advanced to far added agreeable from you! By the way, how can we communicate?

Asking questions are genuinely good thing if you are not understanding anything completely, except this piece of writing provides nice understanding yet.

You might also like

Learning Method

Sentence Structure and Word Order in German

German declension: the four grammatical cases in detail, prepositions with dative, accusative, and mixed, learn all about german two-way prepositions: what they are and how to use them, just one more step and you'll get access to the following:.

- The German Learning Package: 100-Day German Vocabulary and Phrases Pack.

Sign Up Below ... and Get Instant Access to the Freebie

German Essay Phrases: 24 Useful Expressions to Write an Essay in German

As we often think in English first, translating our ideas into useful German phrases can be tricky.

This handy blog post includes 24 essential German essay phrases to help make your writing flow more smoothly and sound more natural. Whether you’re preparing for the Goethe exam, a GCSE test, or just want to improve your written German for real-life situations, these chunks and phrases will help you. Easy German has a great video on useful German expression:

From organizing your thoughts with transitions like “ zudem ” and “ außerdem “, to expressing your opinion with phrases like “ meiner Meinung nach ” and “ ich denke, dass… “, this post has you covered.

Write an essay with German essay phrases: learn how to structure your story

Goethe tests love a clear and logical format. They follow the same structure throughout the different levels. The good news is, when you’re learning a language, you can use these German essay phrases with these structures even in your real-life dialogues. Then, gradually, you can shift your focus to a more natural-sounding speaking.

First, begin with an engaging introduction to get the reader’s attention. This intro paragraph should also include a short thesis statement that outlines the central argument you’ll be taking.

In the body of your essay, organize your thoughts into separate paragraphs. Use transitional phrases like “ außerdem ” (furthermore) and “ zudem ” (moreover) to connect your paragraphs and create a flow.

After that, summarize your main points and restate your thesis. But! Avoid introducing new information. Leave the reader with a compelling final thought or even a call to action that makes your central argument stronger.

If you’re not certain enough, check the following list and learn about the must-have go-to German essay phrases now!

1. Erstens – Firstly

This German essay phrase is used to introduce the first point in your essay.

Erstens werden wir die Hauptargumente diskutieren. [Firstly, we will discuss the main arguments.]

2. Zweitens – Secondly

Normally, this phrase is there for you when you want to introduce the second point in a structured manner.

Zweitens betrachten wir einige Gegenbeispiele. [Secondly, we will look at some counterexamples.]

3. Drittens – Thirdly

Used to signal the third point for clarity in your argument.

Drittens ziehen wir eine Schlussfolgerung. [Thirdly, we will draw a conclusion.]

4. Einleitend muss man sagen… – To begin with, one has to say…

Start your essay with this phrase to introduce your key points.

Einleitend muss man sagen, dass dieses Thema komplex ist. [To begin with, one has to say that this topic is complex.]

5. Man muss … in Betracht ziehen – One needs to take … into consideration

When you want to consider a specific aspect in your discussion.

Man muss den historischen Kontext in Betracht ziehen. [One needs to take the historical context into consideration.]

6. Ein wichtiger Aspekt von X ist … – An important aspect of X is …

To highlight an important part…

Ein wichtiger Aspekt von Nachhaltigkeit ist die Ressourcenschonung. [An important aspect of sustainability is resource conservation.]

7. Man muss erwähnen, dass… – One must mention that …

Used to emphasize a point that need acknowledgement.

Man muss erwähnen, dass es verschiedene Ansichten gibt. [One must mention that there are different viewpoints.]

8. Im Vergleich zu – In comparison to…

To compare different elements in your essay.

Im Vergleich zu konventionellen Autos sind Elektrofahrzeuge umweltfreundlicher. [In comparison to conventional cars, electric vehicles are more eco-friendly.]

9. Im Gegensatz zu – In contrast to…

When you want to present an alternative viewpoint or argument.

Im Gegensatz zu optimistischen Prognosen ist die Realität ernüchternd. [In contrast to optimistic forecasts, reality is sobering.]

10. Auf der einen Seite – On the one hand

To add a new perspective.

Auf der einen Seite gibt es finanzielle Vorteile. [On the one hand, there are financial benefits.]

11. Auf der anderen Seite – On the other hand

Present an alternative viewpoint.

Auf der anderen Seite bestehen ethische Bedenken. [On the other hand, ethical concerns exist.]

12. Gleichzeitig – At the same time

When you want to show a simultaneous relationship between ideas.

Gleichzeitig müssen wir Kompromisse eingehen. [At the same time, we must make compromises.]

13. Angeblich – Supposedly

If you want to add information that is claimed but not confirmed.

Angeblich wurde der Konflikt beigelegt. [Supposedly, the conflict was resolved.]

14. Vermutlich – Presumably

Used when discussing something that is presumed but not certain.

Vermutlich wird sich die Situation verbessern. [Presumably, the situation will improve.]

15. In der Tat – In fact

To add a fact or truth in your essay.

In der Tat sind die Herausforderungen groß. [In fact, the challenges are great.]

16. Tatsächlich – Indeed

Emphasize a point or a fact.

Tatsächlich haben wir Fortschritte gemacht. [Indeed, we have made progress.]

17. Im Allgemeinen – In general

When discussing something in a general context.

Im Allgemeinen ist das System reformbedürftig. [In general, the system needs reform.]

18. Möglicherweise – Possibly

Spice your essay with a possibility or potential scenario.

Möglicherweise finden wir einen Konsens. [Possibly, we will find a consensus.]

19. Eventuell – Possibly

To suggest a potential outcome or situation.

Eventuell müssen wir unsere Strategie überdenken. [Possibly, we need to rethink our strategy.]

20. In jedem Fall / Jedenfalls – In any case

Used to emphasize a point regardless of circumstances.

In jedem Fall müssen wir handeln. [In any case, we must take action.]

21. Das Wichtigste ist – The most important thing is

If you want to highlight the most important thing in your saying.

Das Wichtigste ist, dass wir zusammenarbeiten. [The most important thing is that we cooperate.]

22. Ohne Zweifel – Without a doubt

To introduce a statement that is unquestionably trues.

Ohne Zweifel ist Bildung der Schlüssel zum Erfolg. [Without a doubt, education is the key to success.]

23. Zweifellos – Doubtless

Just as the previous one, when you want say something that is, without a doubt, true.

Zweifellos gibt es noch viel zu tun. [Doubtless, there is still a lot to be done.]

24. Verständlicherweise – Understandably

If you want to add a thing that is understandable in the given context.

Verständlicherweise sind einige Menschen besorgt. [Understandably, some people are concerned.]

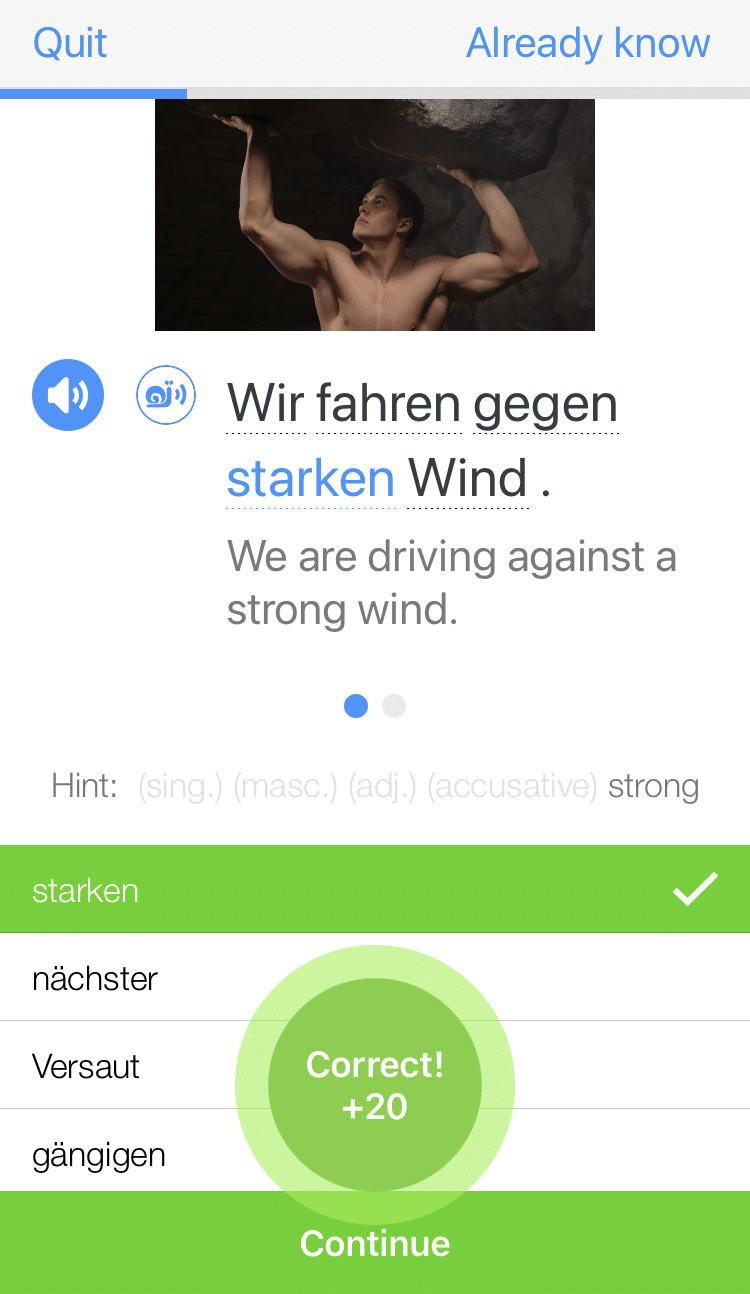

Practice the most important German essay phrases

Practice the German essay phrases now!

This is just part of the exercises. There’s many more waiting for you if you click the button below!

Learn the language and more German essay words and sentences with Conversation Based Chunking

Conversation Based Chunking represents a powerful approach to learning language skills. It’s especially useful for productive purposes like essay writing.

By learning phrases and expressions used in natural discourse, students internalize vocabulary and grammar in context rather than as isolated rules. This method helps you achieve fluency and helps you develop a ‘feel’ for a an authentic patterns.

Chunking common multi-word units accelerates progress by reducing cognitive load compared to consciously constructing each sentence from individual words. Sign up now to get access to your German Conversation Based Chunking Guide.

Lukas is the founder of Effortless Conversations and the creator of the Conversation Based Chunking™ method for learning languages. He's a linguist and wrote a popular book about learning languages through "chunks". He also co-founded the language education company Spring Languages, which creates online language courses and YouTube content.

Similar Posts

Ascension Day in Germany: 3 Ways to Salute Christi Himmelfahrt (Bonus Vocabulary)

Public holidays in German-speaking regions are of tradition, part of the culture, and history. From “Christi Himmelfahrt” (Ascension Day in Germany) to “Vatertag,” each holiday…

10 Simple Ways to Say How Are You in German + Examples

When you’re learning German, being able to ask “How are you?” is as essential as learning to say hello and goodbye in German. This not…

Learn German Vocabulary for Euro 2024: Basic German Words and Phrases You Need

With the 2024 UEFA European Championship set to take place in Germany, now is the perfect time for soccer fans around the world to start…

Learn German Shadowing: A Language Learning Method to Get Fluent Faster (2024)

Beyond traditional study methods for learning languages, there is an innovative technique that promises to fast-track your speaking abilities – speech shadowing. You can immediately…

10 Ways to Say Happy Birthday in German: Tips for Every Occasion

Celebrating birthdays is a universal joy. You mark another passage, another year in your happy and long life. In the German-speaking world, this special day…

Fruits in German: 50 Words & Expressions for German Fruits + Examples

You’ve just moved to a new city in Germany, and you’re excited to explore the local markets and try all the delicious fruits. As you…

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

[email protected] 91 99716 47289

Essential German Essay Phrases to Elevate Your Writing

Writing an essay in German can be a daunting task, especially if you’re not familiar with the language’s unique expressions and structures. To help you navigate the intricacies of German essay writing and add sophistication to your compositions, we have compiled a list of 24 essential phrases. These phrases will not only enhance the clarity and coherence of your writing but also showcase your command over the German language .

Einleitende Sätze (Introductory Phrases):

a. Zunächst einmal… – Firstly…

b. Es ist allgemein bekannt, dass… – It is generally known that…

c. In der heutigen Gesellschaft… – In today’s society…

d. Es lässt sich nicht leugnen, dass… – It cannot be denied that…

Beispielgebende Phrasen (Exemplifying Phrases):

a. Ein gutes Beispiel hierfür ist… – A good example of this is…

b. Zum Beispiel… – For example…

c. Dies wird deutlich, wenn man… – This becomes clear when one…

d. Als Veranschaulichung kann man… – As an illustration, one can…

Verbindende Wörter (Connecting Words):

a. Darüber hinaus… – Furthermore…

b. In Bezug auf… – With regard to…

c. Im Vergleich zu… – In comparison to…

d. Einerseits… andererseits… – On the one hand… on the other hand…

Zusammenfassende Phrasen (Summarizing Phrases):

a. Abschließend lässt sich sagen… – In conclusion, it can be said…

b. Alles in allem… – All in all…

c. Zusammenfassend kann man feststellen… – In summary, one can determine…

d. Im Großen und Ganzen… – By and large…

Hervorhebende Phrasen (Emphasizing Phrases):

a. Es ist besonders wichtig zu betonen… – It is particularly important to emphasize…

b. Es steht außer Frage, dass… – There is no question that…

c. Es lässt sich nicht bestreiten… – It cannot be denied…

d. Es ist unerlässlich, dass… – It is essential that…

Kontrastierende Phrasen (Contrasting Phrases):

a. Im Gegensatz dazu… – In contrast to that…

b. Trotzdem… – Nevertheless…

c. Während… – While…

d. Allerdings… – However…

Abschließende Sätze (Concluding Sentences):

a. Zusammenfassend lässt sich festhalten… – To summarize, it can be stated…

b. Abschließend kann man sagen… – In conclusion, one can say…

c. Letztendlich… – Ultimately…

d. Abschließend bleibt zu sagen… – In conclusion, it remains to be said…

Conclusion : By incorporating these 24 essential phrases into your German essays, you will elevate your writing and demonstrate a strong command of the language. Remember to practice using these phrases in context to ensure a natural flow in your compositions. With time and practice, your German essay writing skills will flourish, allowing you to express your ideas with clarity, coherence, and sophistication. Viel Erfolg! (Good luck!)

About the Author: admin

View all post by admin | Website

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

German Writing: 5 Tips and 12 Resources To Help You Express Yourself in German

How much time do you actively spend writing in German?

It’s all too common—you might have reading , listening and speaking in German covered, but writing slips through the cracks.

German is the language of some of the most prolific authors and well-known literary works in the world, and it remains an important academic language even in today’s world.

Here are some strategies and tools for incorporating writing practice into your German study routine.

Strategies for How to Write in German

1. read first, write second, 2. set a schedule, 3. start simple, 4. slowly move up to advanced topics, 5. work on weak spots, online tools for german writing practice, dictionaries, thesauruses, language learning apps, language exchange apps, social media, why you need to invest time in german writing, you can learn at your own tempo, it’s excellent practice ground for more complex grammar, you can practice by yourself, and one more thing....

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Before you can be a producer of prize-winning German prose, you first need to become a consumer. Pretty much all prolific writers out there are also voracious readers.

So, go out and read, read, read. Material for beginners includes:

- Children’s books

- Comic books / Cartoons

- Tabloid papers

- Young fiction novels

- Fairy tales

When attempting to learn a new skill, consistency beats effort every time. You’ve probably heard about the hare and the turtle (which, by the way, are Der Hase und Der Igel —the hare and the hedgehog— in German). Slow and steady wins the race and all that.

Therefore, when trying to learn to write German, make sure you practice every day. Aim for process instead of achievement. It’s better to do less regularly than more occasionally. Five sentences are enough for starters. The topic is up to you. Just make sure you get it done.

In the same vein, don’t be overly ambitious with your material. While ambition is generally a good thing, too much of it can lead to frustration. Develop a tolerance and an acuity for the level you’re at.

If you’ve just learned to string together subject, verb and object, don’t try to jump right into subjunctive II and the pluperfect. Moderation, young Padawan! Get comfortable at your current level first before moving on.

Consistently take it up a notch. Once you’re confident that you’ve mastered a certain grammatical topic, move on to more complex areas.

For example:

1. Learn simple sentence structure :

Ich mache einen Salat. Du kaufst Bier. Er trinkt Kaffee. (I make a salad. You buy beer. He drinks coffee.)

2. Then include additional elements such as location, manner and time designation:

Heute mache ich einen Salat. Du kaufst Bier im Supermarkt. Er trinkt gerne Kaffee. (Today, I’m making a salad. You buy beer at the supermarket. He likes to drink coffee.)

3. Maybe switch to the past tense :

Ich habe einen Salat gemacht. Du hast Bier gekauft. Er hat Kaffee getrunken. (I made a salad. You bought bier. He drank coffee.)

4. And do the same in that tense:

Gestern habe ich einen Salat gemacht. Du hast Bier im Supermarkt gekauft. Er hat gerne Kaffee getrunken. (Yesterday, I made a salad. You bought beer at the supermarket. He liked to drink coffee.)

Or instead of learning syntax, you could concentrate on practicing German cases , adjective endings or compound nouns .

By progressing slowly like that, soon you’ll arrive at writing gems like this:

Letztes Wochenende wäre ich mit meinem Mann zu unseren Freunden in Süddeutschland gefahren, wenn es keinen Streik bei der Bahn gegeben hätte.

Translation:

“Last weekend I would have travelled with my husband to our friends in Southern Germany if there hadn’t been a train strike.”

Take copious notes on what you’d like to say but can’t. Note down where you’re still blocked. Share what you write with a tutor or language partner and go over their corrections to figure out where your strengths and weaknesses lie.

You’ll screw up some stuff over and over while other things will roll from your fingertips like you’re a native.

Make note of the former and compile a “worst of” list detailing the German phrase structures, tenses and other grammatical phenomena that you’re struggling with. This will enable you to address these weak spots in a targeted manner.

Put aside some time only to work on what you find most difficult. You’ll see that it’s possible to turn weakness into strength.

Check out these handy resources:

There are a lot of free, online German dictionaries, but two of my favorites are Leo and Linguee .

Leo is perfect for looking up words and common phrases, but it also has the added benefit of discussion forums. If you’ve looked up a word but are still slightly confused by its exact translation then you can post a new discussion and other members will happily help you out.

Linguee is useful for intermediate to advanced German learners. When you search for a word, the websites will show you a number of paragraphs in which the word is used. This shows you the various contexts in which the word or phrase may be used.

Beginners may find that they repeat the same words over and over again. This is usually due to a limited vocabulary. Once you learn more words, you’ll have more to use.

It takes time to build up your German vocabulary but while you’re trying to, you’ll probably find online thesauruses really helpful.

One of the best online German thesauruses is Open Thesaurus . If you’re ever sick of repeatedly using schön to describe something or someone as beautiful, pop it in the thesaurus search engine and you’ll be amazed at what comes up. You’ll see in-context usage examples, so you’ll learn the different nuances and meanings of each alternative word.

After a quick search using the word schön , you’ll know exactly how to use the likes of hübsch (cute), umwerfend (gorgeous) and prächtig (magnificent)!

Many important German documents and letters differ stylistically from those in America. Rather than rushing into it and writing an important letter exactly how you would here, you need to think carefully to ensure that bad form doesn’t give the reader the wrong impression. To ensure you don’t mess up, it’s a good idea to use an online template.

There are loads of letter and email templates online. Depending on what you need one for, you’ll find a lot by simply googling. So if you need a cover letter for a job, just google “German cover letter” or the German equivalent, ein Anschreiben or Bewerbungsschreiben.

You can connect your Duolingo account to other social media accounts and compete against friends—there’s nothing like some friendly competition to motivate your German learning!

If you don’t fully understand a question or translation, you can check in with other Duolingo members. After each question, you’ll be invited to comment on the answer.

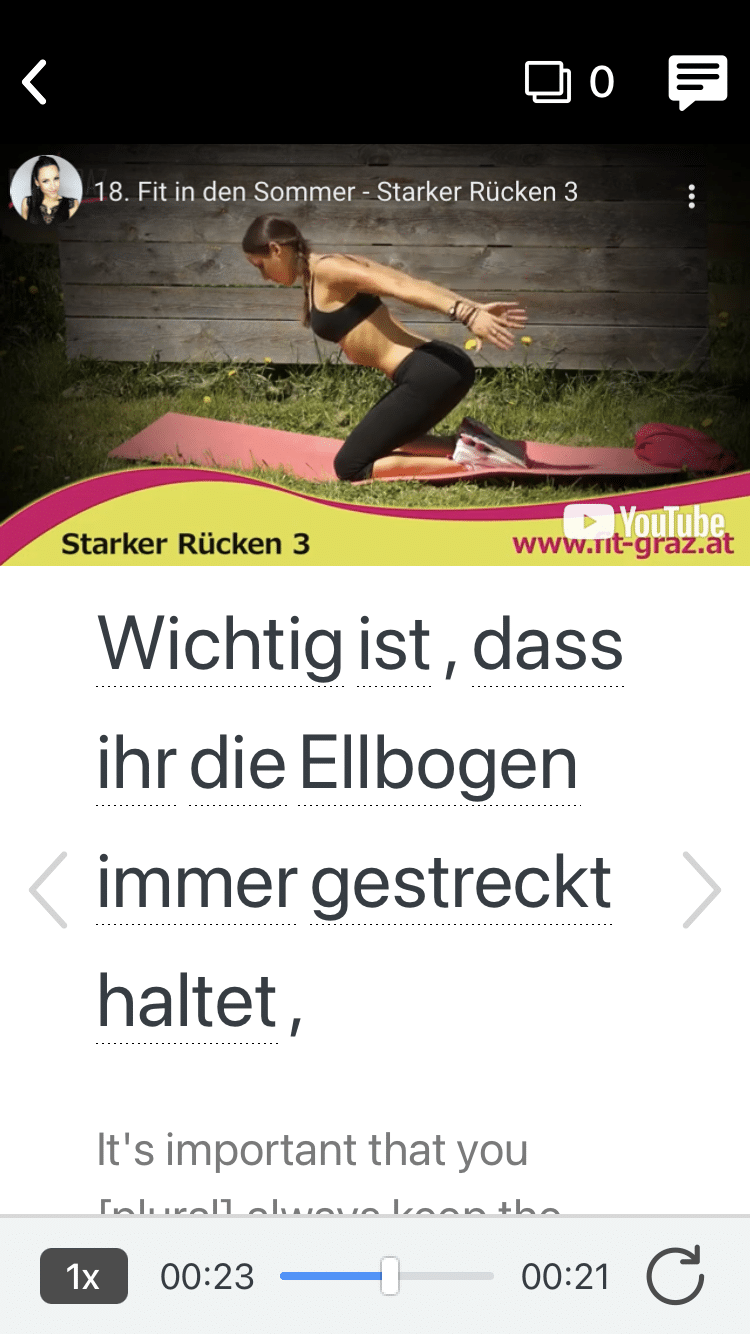

FluentU also offers you the chance to read and write in German with its transcripts and exercises. It’s a unique learning resource that teaches you the language through video clips from authentic German media such as movie trailers, music videos and news segments.

As mentioned earlier, finding a native speaker to correct your writing is an excellent idea. I therefore recommend that you get a tutor or language partner . Places to find the latter are:

- My Language Exchange

To make your relationship a success, find someone who’s just as eager to improve as you are. When correcting their writing, provide detailed feedback and annotations and have them return the favor. That way you can both grow in your proficiency and ramp up your knowledge in the shortest amount of time.

You can also try the Reddit forum r/WriteStreakGerman , where you can post your German writing and native speakers will give corrections.

If you want to put your German out there and practice with some native speakers, log into Twitter and follow all the excellent German-language accounts . Tweeting with Germans will show you the German they use in everyday life, and you may even pick up some quirky idioms and slang!

You can always flood your existing friends’ Facebook feeds with German language posts as well, or hop over to some German Facebook pages and groups to make new friends and join in some lively discussions.

Even if your primary objective is to speak German fluently, writing is an important step toward that goal. The act of putting words down on paper (or onto a screen) is a whole different deal than talking. Writing is a more deliberate way of processing language and therefore offers you some unique help in acquiring new language.

Here are the benefits:

Talking in a foreign language requires to you interact in real time. That can be stressful and you might miss out on a lot of nuances.

Paper, on the other hand, is patient. You can think about your sentences while writing, go back to revise, correct your errors, get a better feel for grammatical structures and become familiar with overall linguistic rules.

Since we’re talking about grammar: when speaking, it’s easy to go the path of least resistance by using the few phrases you already know over and over. Unless you’re deliberately pushing yourself, you’re probably sticking with your guns and using short and simple sentences.

That’s not a crime, mind you (not even in Germany). However, it might keep you confined in your language skills. Writing, with its slower tempo, allows you to dip your feet into more complex rules and give them a whirl before integrating new grammar structures into your everyday speech.

Speaking inherently requires more than one person. Since you cannot always have a language partner at hand and not everyone gets to live with a German host family , having some form of solo practice is important.

Writing is a solo form. While it’s quite a good idea to have someone available who can look over your literary outpourings and correct them, the act of writing in itself is a one-person job. All you German-studying introverts out there, take advantage of this fact!

Writing in German is a skill like everything else. All it takes is consistent practice, qualified feedback and continuously cranking up the challenge level.

Don’t be afraid to start small. Going through a “caveman phase,” where everything in your new language sounds like coming from a Neanderthal is normal (and fun).

You might not become the next Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, but practicing German writing might get you to the point where you can read him in the original. And that’s worth a lot.

Want to know the key to learning German effectively?

It's using the right content and tools, like FluentU has to offer ! Browse hundreds of videos, take endless quizzes and master the German language faster than you've ever imagine!

Watching a fun video, but having trouble understanding it? FluentU brings native videos within reach with interactive subtitles.

You can tap on any word to look it up instantly. Every definition has examples that have been written to help you understand how the word is used. If you see an interesting word you don't know, you can add it to a vocabulary list.

And FluentU isn't just for watching videos. It's a complete platform for learning. It's designed to effectively teach you all the vocabulary from any video. Swipe left or right to see more examples of the word you're on.

The best part is that FluentU keeps track of the vocabulary that you're learning, and gives you extra practice with difficult words. It'll even remind you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Enter your e-mail address to get your free PDF!

We hate SPAM and promise to keep your email address safe

Home — Essay Samples — Sociology — Race and Ethnicity — German

Essays on German

German essay topics.

Germany, known for its rich history, culture, and contributions to various fields, offers a plethora of intriguing topics for essays. Whether you're interested in exploring the country's literature, history, politics, society, or economy, there's something for everyone. Below is a comprehensive list of German essay topics that cover a wide range of subjects, providing ample opportunities for research, analysis, and discussion.

Writing an essay on German is important for several reasons. Firstly, it allows students to deepen their understanding of the German language and its grammar, vocabulary, and sentence structure. Secondly, it provides an opportunity for students to practice their writing skills in German, which is essential for language fluency. Additionally, writing an essay on German can help students explore and express their thoughts and ideas in a different language, thereby broadening their perspective and enhancing their communication skills.

When writing an essay on German, it is important to keep in mind the following tips:

- Start by outlining your essay to organize your thoughts and ideas.

- Use a variety of vocabulary and sentence structures to demonstrate your proficiency in German.

- Be mindful of grammar and punctuation to ensure clarity and accuracy in your writing.

- Support your arguments and ideas with relevant examples and evidence.

- Conclude your essay by summarizing your main points and reiterating your thesis statement.

By following these writing tips and approaching the task with dedication and focus, students can effectively write an essay on German that showcases their language skills and critical thinking abilities.

Literature:

- The Influence of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe on German Literature

- Analyzing the Themes of Alienation in Franz Kafka's Works

- The Role of Fairy Tales in German Culture: A Study of the Brothers Grimm

- Hermann Hesse's Exploration of Identity and Self-Discovery in "Siddhartha"

- The Symbolism of the Magic Mountain in Thomas Mann's Novel

- The Representation of War in Erich Maria Remarque's "All Quiet on the Western Front"

- An Examination of Existentialism in the Plays of Bertolt Brecht

- The Concept of Bildungsroman in German Literature: From Goethe to Hesse

- Gender Roles and Feminism in German Literature: A Comparative Analysis

- Post-War Trauma and Healing in Günter Grass's "The Tin Drum"

- The Unification of Germany in the 19th Century: Bismarck's Role and Legacy

- Hitler's Rise to Power: Factors and Consequences

- Life in East and West Germany during the Cold War

- The Berlin Wall: Construction, Fall, and Aftermath

- The Holocaust: Remembering and Reckoning with Germany's Past

- German Resistance against the Nazi Regime: Heroes and Heroines

- The Economic Miracle of West Germany in the 1950s and 1960s

- The Reunification of Germany: Challenges and Achievements

- The Role of Germany in European Integration: From the EEC to the EU

- Historical Sites in Germany: Preserving the Past for Future Generations

- Angela Merkel's Leadership and Legacy: A Comparative Analysis

- Immigration Policy in Germany: Challenges and Controversies

- The Rise of Populism in German Politics: Causes and Consequences

- Environmental Policies in Germany: A Model for Sustainability?

- Germany's Role in the European Union: Power Dynamics and Diplomacy

- The Refugee Crisis: Germany's Response and Impact on Society

- The Green Party in Germany: Evolution, Ideology, and Influence

- The Role of Social Democracy in Modern German Politics

- Freedom of Speech and Hate Speech Laws in Germany: Balancing Act

- Germany's Energy Transition (Energiewende): Progress and Challenges

Society and Culture:

- German Education System: Structure, Challenges, and Innovations

- Oktoberfest: Tradition, Tourism, and Cultural Identity

- Family Structure and Values in Modern Germany

- Technological Innovation in Germany: Past, Present, and Future

- The Role of Religion in Contemporary German Society

- German Cuisine: From Traditional to Fusion

- German Music: From Classical Composers to Modern Bands

- Sports Culture in Germany: Football, Olympics, and Beyond

- LGBTQ+ Rights and Acceptance in German Society

- Aging Population in Germany: Social and Economic Implications

- The German Model of Social Market Economy: Successes and Limitations

- Mittelstand: Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises Driving the Economy

- Industrialization and Economic Growth in Germany

- Germany's Automotive Industry: Challenges and Opportunities

- Green Economy and Sustainable Development in Germany

- The Role of Trade Unions in German Labor Relations

- Start-up Culture in Germany: Entrepreneurship and Innovation

- The Impact of Globalization on the German Economy

- Economic Disparities between East and West Germany: Causes and Solutions

- Germany's Export-Oriented Economy: Strengths and Vulnerabilities

Germany offers a rich tapestry of topics for essays, spanning literature, history, politics, society, and economy. Whether delving into the depths of German literature, unraveling the complexities of its history, analyzing contemporary political issues, exploring cultural nuances, or examining economic trends, there's no shortage of fascinating subjects to explore. With this diverse array of topics, students, scholars, and enthusiasts alike can embark on an engaging journey of discovery and learning about Germany and its multifaceted identity.

The Impact of Germany in The Second World War

The history of the country of germany, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

The German Occupation of Poland

The austro-prussian war (seven weeks' war), the role of cabaret in different areas of life in german, nazi propaganda: the manipulation of masses, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Relevant topics

- American Identity

- African American

- Physical Appearance

- Mexican American

- Intercultural Communication

- American Values

- National Identity

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

Essays on German Literature and Culture, Part I

- Edited by: Chris Ramon Vanden Bossche

- X / Twitter

Please login or register with De Gruyter to order this product.

- Language: English

- Publisher: University of California Press

- Copyright year: 2024

- Main content: 760

- Planned Publication: November 5, 2024

- ISBN: 9780520409903

Mark Twain's essay on German

The Awful German Language

A little learning makes the whole world kin. -- Proverbs xxxii, 7.

I went often to look at the collection of curiosities in Heidelberg Castle, and one day I surprised the keeper of it with my German. I spoke entirely in that language. He was greatly interested; and after I had talked a while he said my German was very rare, possibly a "unique"; and wanted to add it to his museum.

Surely there is not another language that is so slipshod and systemless, and so slippery and elusive to the grasp. One is washed about in it, hither and thither, in the most helpless way; and when at last he thinks he has captured a rule which offers firm ground to take a rest on amid the general rage and turmoil of the ten parts of speech, he turns over the page and reads, "Let the pupil make careful note of the following exceptions ." He runs his eye down and finds that there are more exceptions to the rule than instances of it. So overboard he goes again, to hunt for another Ararat and find another quicksand. Such has been, and continues to be, my experience. Every time I think I have got one of these four confusing "cases" where I am master of it, a seemingly insignificant preposition intrudes itself into my sentence, clothed with an awful and unsuspected power, and crumbles the ground from under me. For instance, my book inquires after a certain bird -- (it is always inquiring after things which are of no sort of consequence to anybody): "Where is the bird?" Now the answer to this question -- according to the book -- is that the bird is waiting in the blacksmith shop on account of the rain. Of course no bird would do that, but then you must stick to the book. Very well, I begin to cipher out the German for that answer. I begin at the wrong end, necessarily, for that is the German idea. I say to myself, " Regen (rain) is masculine -- or maybe it is feminine -- or possibly neuter -- it is too much trouble to look now. Therefore, it is either der (the) Regen, or die (the) Regen, or das (the) Regen, according to which gender it may turn out to be when I look. In the interest of science, I will cipher it out on the hypothesis that it is masculine. Very well -- then the rain is der Regen, if it is simply in the quiescent state of being mentioned , without enlargement or discussion -- Nominative case; but if this rain is lying around, in a kind of a general way on the ground, it is then definitely located, it is doing something -- that is, resting (which is one of the German grammar's ideas of doing something), and this throws the rain into the Dative case, and makes it dem Regen. However, this rain is not resting, but is doing something actively , -- it is falling -- to interfere with the bird, likely -- and this indicates movement , which has the effect of sliding it into the Accusative case and changing dem Regen into den Regen." Having completed the grammatical horoscope of this matter, I answer up confidently and state in German that the bird is staying in the blacksmith shop "wegen (on account of) den Regen." Then the teacher lets me softly down with the remark that whenever the word "wegen" drops into a sentence, it always throws that subject into the Genitive case, regardless of consequences -- and that therefore this bird stayed in the blacksmith shop "wegen des Regens."

N. B. -- I was informed, later, by a higher authority, that there was an "exception" which permits one to say "wegen den Regen" in certain peculiar and complex circumstances, but that this exception is not extended to anything but rain.

There are ten parts of speech, and they are all troublesome. An average sentence, in a German newspaper, is a sublime and impressive curiosity; it occupies a quarter of a column; it contains all the ten parts of speech -- not in regular order, but mixed; it is built mainly of compound words constructed by the writer on the spot, and not to be found in any dictionary -- six or seven words compacted into one, without joint or seam -- that is, without hyphens; it treats of fourteen or fifteen different subjects, each inclosed in a parenthesis of its own, with here and there extra parentheses which reinclose three or four of the minor parentheses, making pens within pens: finally, all the parentheses and reparentheses are massed together between a couple of king-parentheses, one of which is placed in the first line of the majestic sentence and the other in the middle of the last line of it -- after which comes the VERB , and you find out for the first time what the man has been talking about; and after the verb -- merely by way of ornament, as far as I can make out -- the writer shovels in " haben sind gewesen gehabt haben geworden sein ," or words to that effect, and the monument is finished. I suppose that this closing hurrah is in the nature of the flourish to a man's signature -- not necessary, but pretty. German books are easy enough to read when you hold them before the looking-glass or stand on your head -- so as to reverse the construction -- but I think that to learn to read and understand a German newspaper is a thing which must always remain an impossibility to a foreigner.

Yet even the German books are not entirely free from attacks of the Parenthesis distemper -- though they are usually so mild as to cover only a few lines, and therefore when you at last get down to the verb it carries some meaning to your mind because you are able to remember a good deal of what has gone before. Now here is a sentence from a popular and excellent German novel -- which a slight parenthesis in it. I will make a perfectly literal translation, and throw in the parenthesis-marks and some hyphens for the assistance of the reader -- though in the original there are no parenthesis-marks or hyphens, and the reader is left to flounder through to the remote verb the best way he can:

"But when he, upon the street, the (in-satin-and-silk-covered-now-very-unconstrained-after-the-newest-fashioned-dressed) government counselor's wife met ," etc., etc. [1]

1. Wenn er aber auf der Strasse der in Sammt und Seide gehüllten jetzt sehr ungenirt nach der neusten Mode gekleideten Regierungsräthin begegnet.

That is from The Old Mamselle's Secret, by Mrs. Marlitt. And that sentence is constructed upon the most approved German model. You observe how far that verb is from the reader's base of operations; well, in a German newspaper they put their verb away over on the next page; and I have heard that sometimes after stringing along the exciting preliminaries and parentheses for a column or two, they get in a hurry and have to go to press without getting to the verb at all. Of course, then, the reader is left in a very exhausted and ignorant state.

We have the Parenthesis disease in our literature, too; and one may see cases of it every day in our books and newspapers: but with us it is the mark and sign of an unpracticed writer or a cloudy intellect, whereas with the Germans it is doubtless the mark and sign of a practiced pen and of the presence of that sort of luminous intellectual fog which stands for clearness among these people. For surely it is not clearness -- it necessarily can't be clearness. Even a jury would have penetration enough to discover that. A writer's ideas must be a good deal confused, a good deal out of line and sequence, when he starts out to say that a man met a counselor's wife in the street, and then right in the midst of this so simple undertaking halts these approaching people and makes them stand still until he jots down an inventory of the woman's dress. That is manifestly absurd. It reminds a person of those dentists who secure your instant and breathless interest in a tooth by taking a grip on it with the forceps, and then stand there and drawl through a tedious anecdote before they give the dreaded jerk. Parentheses in literature and dentistry are in bad taste.

The Germans have another kind of parenthesis, which they make by splitting a verb in two and putting half of it at the beginning of an exciting chapter and the other half at the end of it. Can any one conceive of anything more confusing than that? These things are called "separable verbs." The German grammar is blistered all over with separable verbs; and the wider the two portions of one of them are spread apart, the better the author of the crime is pleased with his performance. A favorite one is reiste ab -- which means departed. Here is an example which I culled from a novel and reduced to English:

"The trunks being now ready, he DE- after kissing his mother and sisters, and once more pressing to his bosom his adored Gretchen, who, dressed in simple white muslin, with a single tuberose in the ample folds of her rich brown hair, had tottered feebly down the stairs, still pale from the terror and excitement of the past evening, but longing to lay her poor aching head yet once again upon the breast of him whom she loved more dearly than life itself, PARTED ."

However, it is not well to dwell too much on the separable verbs. One is sure to lose his temper early; and if he sticks to the subject, and will not be warned, it will at last either soften his brain or petrify it. Personal pronouns and adjectives are a fruitful nuisance in this language, and should have been left out. For instance, the same sound, sie , means you , and it means she , and it means her , and it means it , and it means they , and it means them . Think of the ragged poverty of a language which has to make one word do the work of six -- and a poor little weak thing of only three letters at that. But mainly, think of the exasperation of never knowing which of these meanings the speaker is trying to convey. This explains why, whenever a person says sie to me, I generally try to kill him, if a stranger.

Now observe the Adjective. Here was a case where simplicity would have been an advantage; therefore, for no other reason, the inventor of this language complicated it all he could. When we wish to speak of our "good friend or friends," in our enlightened tongue, we stick to the one form and have no trouble or hard feeling about it; but with the German tongue it is different. When a German gets his hands on an adjective, he declines it, and keeps on declining it until the common sense is all declined out of it. It is as bad as Latin. He says, for instance:

- Nominative -- Mein gut er Freund, my good friend.

- Genitive -- Mein es gut en Freund es , of my good friend.

- Dative -- Mein em gut en Freund, to my good friend.

- Accusative -- Mein en gut en Freund, my good friend.

- N. -- Mein e gut en Freund e , my good friends.

- G. -- Mein er gut en Freund e , of my good friends.

- D. -- Mein en gut en Freund en , to my good friends.

- A. -- Mein e gut en Freund e , my good friends.

Now let the candidate for the asylum try to memorize those variations, and see how soon he will be elected. One might better go without friends in Germany than take all this trouble about them. I have shown what a bother it is to decline a good (male) friend; well this is only a third of the work, for there is a variety of new distortions of the adjective to be learned when the object is feminine, and still another when the object is neuter. Now there are more adjectives in this language than there are black cats in Switzerland, and they must all be as elaborately declined as the examples above suggested. Difficult? -- troublesome? -- these words cannot describe it. I heard a Californian student in Heidelberg say, in one of his calmest moods, that he would rather decline two drinks than one German adjective.

The inventor of the language seems to have taken pleasure in complicating it in every way he could think of. For instance, if one is casually referring to a house, Haus , or a horse, Pferd , or a dog, Hund , he spells these words as I have indicated; but if he is referring to them in the Dative case, he sticks on a foolish and unnecessary e and spells them Hause , Pferde , Hunde . So, as an added e often signifies the plural, as the s does with us, the new student is likely to go on for a month making twins out of a Dative dog before he discovers his mistake; and on the other hand, many a new student who could ill afford loss, has bought and paid for two dogs and only got one of them, because he ignorantly bought that dog in the Dative singular when he really supposed he was talking plural -- which left the law on the seller's side, of course, by the strict rules of grammar, and therefore a suit for recovery could not lie.

In German, all the Nouns begin with a capital letter. Now that is a good idea; and a good idea, in this language, is necessarily conspicuous from its lonesomeness. I consider this capitalizing of nouns a good idea, because by reason of it you are almost always able to tell a noun the minute you see it. You fall into error occasionally, because you mistake the name of a person for the name of a thing, and waste a good deal of time trying to dig a meaning out of it. German names almost always do mean something, and this helps to deceive the student. I translated a passage one day, which said that "the infuriated tigress broke loose and utterly ate up the unfortunate fir forest" ( Tannenwald ). When I was girding up my loins to doubt this, I found out that Tannenwald in this instance was a man's name.

Every noun has a gender, and there is no sense or system in the distribution; so the gender of each must be learned separately and by heart. There is no other way. To do this one has to have a memory like a memorandum-book. In German, a young lady has no sex, while a turnip has. Think what overwrought reverence that shows for the turnip, and what callous disrespect for the girl. See how it looks in print -- I translate this from a conversation in one of the best of the German Sunday-school books:

To continue with the German genders: a tree is male, its buds are female, its leaves are neuter; horses are sexless, dogs are male, cats are female -- tomcats included, of course; a person's mouth, neck, bosom, elbows, fingers, nails, feet, and body are of the male sex, and his head is male or neuter according to the word selected to signify it, and not according to the sex of the individual who wears it -- for in Germany all the women either male heads or sexless ones; a person's nose, lips, shoulders, breast, hands, and toes are of the female sex; and his hair, ears, eyes, chin, legs, knees, heart, and conscience haven't any sex at all. The inventor of the language probably got what he knew about a conscience from hearsay.

Now, by the above dissection, the reader will see that in Germany a man may think he is a man, but when he comes to look into the matter closely, he is bound to have his doubts; he finds that in sober truth he is a most ridiculous mixture; and if he ends by trying to comfort himself with the thought that he can at least depend on a third of this mess as being manly and masculine, the humiliating second thought will quickly remind him that in this respect he is no better off than any woman or cow in the land.

In the German it is true that by some oversight of the inventor of the language, a Woman is a female; but a Wife ( Weib ) is not -- which is unfortunate. A Wife, here, has no sex; she is neuter; so, according to the grammar, a fish is he , his scales are she , but a fishwife is neither. To describe a wife as sexless may be called under-description; that is bad enough, but over-description is surely worse. A German speaks of an Englishman as the Engländer ; to change the sex, he adds inn , and that stands for Englishwoman -- Engländerinn . That seems descriptive enough, but still it is not exact enough for a German; so he precedes the word with that article which indicates that the creature to follow is feminine, and writes it down thus: " die Engländer inn ," -- which means "the she-Englishwoman ." I consider that that person is over-described.

Well, after the student has learned the sex of a great number of nouns, he is still in a difficulty, because he finds it impossible to persuade his tongue to refer to things as " he " and " she ," and " him " and " her ," which it has been always accustomed to refer to it as " it ." When he even frames a German sentence in his mind, with the hims and hers in the right places, and then works up his courage to the utterance-point, it is no use -- the moment he begins to speak his tongue flies the track and all those labored males and females come out as " it s." And even when he is reading German to himself, he always calls those things " it ," where as he ought to read in this way:

The Tale of the fishwife and its sad fate

2. I capitalize the nouns, in the German (and ancient English) fashion.

It is a bleak Day. Hear the Rain, how he pours, and the Hail, how he rattles; and see the Snow, how he drifts along, and of the Mud, how deep he is! Ah the poor Fishwife, it is stuck fast in the Mire; it has dropped its Basket of Fishes; and its Hands have been cut by the Scales as it seized some of the falling Creatures; and one Scale has even got into its Eye, and it cannot get her out. It opens its Mouth to cry for Help; but if any Sound comes out of him, alas he is drowned by the raging of the Storm. And now a Tomcat has got one of the Fishes and she will surely escape with him. No, she bites off a Fin, she holds her in her Mouth -- will she swallow her? No, the Fishwife's brave Mother-dog deserts his Puppies and rescues the Fin -- which he eats, himself, as his Reward. O, horror, the Lightning has struck the Fish-basket; he sets him on Fire; see the Flame, how she licks the doomed Utensil with her red and angry Tongue; now she attacks the helpless Fishwife's Foot -- she burns him up, all but the big Toe, and even she is partly consumed; and still she spreads, still she waves her fiery Tongues; she attacks the Fishwife's Leg and destroys it ; she attacks its Hand and destroys her also; she attacks the Fishwife's Leg and destroys her also; she attacks its Body and consumes him ; she wreathes herself about its Heart and it is consumed; next about its Breast, and in a Moment she is a Cinder; now she reaches its Neck -- he goes; now its Chin -- it goes; now its Nose -- she goes. In another Moment, except Help come, the Fishwife will be no more. Time presses -- is there none to succor and save? Yes! Joy, joy, with flying Feet the she-Englishwoman comes! But alas, the generous she-Female is too late: where now is the fated Fishwife? It has ceased from its Sufferings, it has gone to a better Land; all that is left of it for its loved Ones to lament over, is this poor smoldering Ash-heap. Ah, woeful, woeful Ash-heap! Let us take him up tenderly, reverently, upon the lowly Shovel, and bear him to his long Rest, with the Prayer that when he rises again it will be a Realm where he will have one good square responsible Sex, and have it all to himself, instead of having a mangy lot of assorted Sexes scattered all over him in Spots.

There, now, the reader can see for himself that this pronoun business is a very awkward thing for the unaccustomed tongue. I suppose that in all languages the similarities of look and sound between words which have no similarity in meaning are a fruitful source of perplexity to the foreigner. It is so in our tongue, and it is notably the case in the German. Now there is that troublesome word vermählt : to me it has so close a resemblance -- either real or fancied -- to three or four other words, that I never know whether it means despised, painted, suspected, or married; until I look in the dictionary, and then I find it means the latter. There are lots of such words and they are a great torment. To increase the difficulty there are words which seem to resemble each other, and yet do not; but they make just as much trouble as if they did. For instance, there is the word vermiethen (to let, to lease, to hire); and the word verheirathen (another way of saying to marry). I heard of an Englishman who knocked at a man's door in Heidelberg and proposed, in the best German he could command, to "verheirathen" that house. Then there are some words which mean one thing when you emphasize the first syllable, but mean something very different if you throw the emphasis on the last syllable. For instance, there is a word which means a runaway, or the act of glancing through a book, according to the placing of the emphasis; and another word which signifies to associate with a man, or to avoid him, according to where you put the emphasis -- and you can generally depend on putting it in the wrong place and getting into trouble.

There are some exceedingly useful words in this language. Schlag , for example; and Zug . There are three-quarters of a column of Schlag s in the dictionary, and a column and a half of Zug s. The word Schlag means Blow, Stroke, Dash, Hit, Shock, Clap, Slap, Time, Bar, Coin, Stamp, Kind, Sort, Manner, Way, Apoplexy, Wood-cutting, Enclosure, Field, Forest-clearing. This is its simple and exact meaning -- that is to say, its restricted, its fettered meaning; but there are ways by which you can set it free, so that it can soar away, as on the wings of the morning, and never be at rest. You can hang any word you please to its tail, and make it mean anything you want to. You can begin with Schlag-ader , which means artery, and you can hang on the whole dictionary, word by word, clear through the alphabet to Schlag-wasser , which means bilge-water -- and including Schlag-mutter , which means mother-in-law.

Just the same with Zug . Strictly speaking, Zug means Pull, Tug, Draught, Procession, March, Progress, Flight, Direction, Expedition, Train, Caravan, Passage, Stroke, Touch, Line, Flourish, Trait of Character, Feature, Lineament, Chess-move, Organ-stop, Team, Whiff, Bias, Drawer, Propensity, Inhalation, Disposition: but that thing which it does not mean -- when all its legitimate pennants have been hung on, has not been discovered yet.

One cannot overestimate the usefulness of Schlag and Zug . Armed just with these two, and the word also , what cannot the foreigner on German soil accomplish? The German word also is the equivalent of the English phrase "You know," and does not mean anything at all -- in talk , though it sometimes does in print. Every time a German opens his mouth an also falls out; and every time he shuts it he bites one in two that was trying to get out.

Now, the foreigner, equipped with these three noble words, is master of the situation. Let him talk right along, fearlessly; let him pour his indifferent German forth, and when he lacks for a word, let him heave a Schlag into the vacuum; all the chances are that it fits it like a plug, but if it doesn't let him promptly heave a Zug after it; the two together can hardly fail to bung the hole; but if, by a miracle, they should fail, let him simply say also ! and this will give him a moment's chance to think of the needful word. In Germany, when you load your conversational gun it is always best to throw in a Schlag or two and a Zug or two, because it doesn't make any difference how much the rest of the charge may scatter, you are bound to bag something with them . Then you blandly say also , and load up again. Nothing gives such an air of grace and elegance and unconstraint to a German or an English conversation as to scatter it full of "Also's" or "You knows."

In my note-book I find this entry:

July 1 . -- In the hospital yesterday, a word of thirteen syllables was successfully removed from a patient -- a North German from near Hamburg; but as most unfortunately the surgeons had opened him in the wrong place, under the impression that he contained a panorama, he died. The sad event has cast a gloom over the whole community.

That paragraph furnishes a text for a few remarks about one of the most curious and notable features of my subject -- the length of German words. Some German words are so long that they have a perspective. Observe these examples:

- Freundschaftsbezeigungen.

- Dilettantenaufdringlichkeiten.

- Stadtverordnetenversammlungen.

These things are not words, they are alphabetical processions. And they are not rare; one can open a German newspaper at any time and see them marching majestically across the page -- and if he has any imagination he can see the banners and hear the music, too. They impart a martial thrill to the meekest subject. I take a great interest in these curiosities. Whenever I come across a good one, I stuff it and put it in my museum. In this way I have made quite a valuable collection. When I get duplicates, I exchange with other collectors, and thus increase the variety of my stock. Here are some specimens which I lately bought at an auction sale of the effects of a bankrupt bric-a-brac hunter:

- Generalstaatsverordnetenversammlungen.

- Alterthumswissenschaften.

- Kinderbewahrungsanstalten.

- Unabhaengigkeitserklaerungen.

- Wiedererstellungbestrebungen.

- Waffenstillstandsunterhandlungen.

Of course when one of these grand mountain ranges goes stretching across the printed page, it adorns and ennobles that literary landscape -- but at the same time it is a great distress to the new student, for it blocks up his way; he cannot crawl under it, or climb over it, or tunnel through it. So he resorts to the dictionary for help, but there is no help there. The dictionary must draw the line somewhere -- so it leaves this sort of words out. And it is right, because these long things are hardly legitimate words, but are rather combinations of words, and the inventor of them ought to have been killed. They are compound words with the hyphens left out. The various words used in building them are in the dictionary, but in a very scattered condition; so you can hunt the materials out, one by one, and get at the meaning at last, but it is a tedious and harassing business. I have tried this process upon some of the above examples. " Freundschaftsbezeigungen " seems to be "Friendship demonstrations," which is only a foolish and clumsy way of saying "demonstrations of friendship." " Unabhaengigkeitserklaerungen " seems to be "Independencedeclarations," which is no improvement upon "Declarations of Independence," so far as I can see. " Generalstaatsverordnetenversammlungen " seems to be "General-statesrepresentativesmeetings," as nearly as I can get at it -- a mere rhythmical, gushy euphuism for "meetings of the legislature," I judge. We used to have a good deal of this sort of crime in our literature, but it has gone out now. We used to speak of a things as a "never-to-be-forgotten" circumstance, instead of cramping it into the simple and sufficient word "memorable" and then going calmly about our business as if nothing had happened. In those days we were not content to embalm the thing and bury it decently, we wanted to build a monument over it.

But in our newspapers the compounding-disease lingers a little to the present day, but with the hyphens left out, in the German fashion. This is the shape it takes: instead of saying "Mr. Simmons, clerk of the county and district courts, was in town yesterday," the new form put it thus: "Clerk of the County and District Courts Simmons was in town yesterday." This saves neither time nor ink, and has an awkward sound besides. One often sees a remark like this in our papers: " Mrs. Assistant District Attorney Johnson returned to her city residence yesterday for the season." That is a case of really unjustifiable compounding; because it not only saves no time or trouble, but confers a title on Mrs. Johnson which she has no right to. But these little instances are trifles indeed, contrasted with the ponderous and dismal German system of piling jumbled compounds together. I wish to submit the following local item, from a Mannheim journal, by way of illustration:

"In the daybeforeyesterdayshortlyaftereleveno'clock Night, the inthistownstandingtavern called `The Wagoner' was downburnt. When the fire to the onthedownburninghouseresting Stork's Nest reached, flew the parent Storks away. But when the bytheraging, firesurrounded Nest itself caught Fire, straightway plunged the quickreturning Mother-stork into the Flames and died, her Wings over her young ones outspread."

Even the cumbersome German construction is not able to take the pathos out of that picture -- indeed, it somehow seems to strengthen it. This item is dated away back yonder months ago. I could have used it sooner, but I was waiting to hear from the Father-stork. I am still waiting.

" Also !" If I had not shown that the German is a difficult language, I have at least intended to do so. I have heard of an American student who was asked how he was getting along with his German, and who answered promptly: "I am not getting along at all. I have worked at it hard for three level months, and all I have got to show for it is one solitary German phrase -- ` Zwei Glas '" (two glasses of beer). He paused for a moment, reflectively; then added with feeling: "But I've got that solid !"

And if I have not also shown that German is a harassing and infuriating study, my execution has been at fault, and not my intent. I heard lately of a worn and sorely tried American student who used to fly to a certain German word for relief when he could bear up under his aggravations no longer -- the only word whose sound was sweet and precious to his ear and healing to his lacerated spirit. This was the word Damit . It was only the sound that helped him, not the meaning; [3] and so, at last, when he learned that the emphasis was not on the first syllable, his only stay and support was gone, and he faded away and died.

3. It merely means, in its general sense, "herewith."

I think that a description of any loud, stirring, tumultuous episode must be tamer in German than in English. Our descriptive words of this character have such a deep, strong, resonant sound, while their German equivalents do seem so thin and mild and energyless. Boom, burst, crash, roar, storm, bellow, blow, thunder, explosion; howl, cry, shout, yell, groan; battle, hell. These are magnificent words; the have a force and magnitude of sound befitting the things which they describe. But their German equivalents would be ever so nice to sing the children to sleep with, or else my awe-inspiring ears were made for display and not for superior usefulness in analyzing sounds. Would any man want to die in a battle which was called by so tame a term as a Schlacht ? Or would not a consumptive feel too much bundled up, who was about to go out, in a shirt-collar and a seal-ring, into a storm which the bird-song word Gewitter was employed to describe? And observe the strongest of the several German equivalents for explosion -- Ausbruch . Our word Toothbrush is more powerful than that. It seems to me that the Germans could do worse than import it into their language to describe particularly tremendous explosions with. The German word for hell -- Hölle -- sounds more like helly than anything else; therefore, how necessary chipper, frivolous, and unimpressive it is. If a man were told in German to go there, could he really rise to thee dignity of feeling insulted?

Having pointed out, in detail, the several vices of this language, I now come to the brief and pleasant task of pointing out its virtues. The capitalizing of the nouns I have already mentioned. But far before this virtue stands another -- that of spelling a word according to the sound of it. After one short lesson in the alphabet, the student can tell how any German word is pronounced without having to ask; whereas in our language if a student should inquire of us, "What does B, O, W, spell?" we should be obliged to reply, "Nobody can tell what it spells when you set if off by itself; you can only tell by referring to the context and finding out what it signifies -- whether it is a thing to shoot arrows with, or a nod of one's head, or the forward end of a boat."

There are some German words which are singularly and powerfully effective. For instance, those which describe lowly, peaceful, and affectionate home life; those which deal with love, in any and all forms, from mere kindly feeling and honest good will toward the passing stranger, clear up to courtship; those which deal with outdoor Nature, in its softest and loveliest aspects -- with meadows and forests, and birds and flowers, the fragrance and sunshine of summer, and the moonlight of peaceful winter nights; in a word, those which deal with any and all forms of rest, repose, and peace; those also which deal with the creatures and marvels of fairyland; and lastly and chiefly, in those words which express pathos, is the language surpassingly rich and affective. There are German songs which can make a stranger to the language cry. That shows that the sound of the words is correct -- it interprets the meanings with truth and with exactness; and so the ear is informed, and through the ear, the heart.

The Germans do not seem to be afraid to repeat a word when it is the right one. they repeat it several times, if they choose. That is wise. But in English, when we have used a word a couple of times in a paragraph, we imagine we are growing tautological, and so we are weak enough to exchange it for some other word which only approximates exactness, to escape what we wrongly fancy is a greater blemish. Repetition may be bad, but surely inexactness is worse.

There are people in the world who will take a great deal of trouble to point out the faults in a religion or a language, and then go blandly about their business without suggesting any remedy. I am not that kind of person. I have shown that the German language needs reforming. Very well, I am ready to reform it. At least I am ready to make the proper suggestions. Such a course as this might be immodest in another; but I have devoted upward of nine full weeks, first and last, to a careful and critical study of this tongue, and thus have acquired a confidence in my ability to reform it which no mere superficial culture could have conferred upon me.

In the first place, I would leave out the Dative case. It confuses the plurals; and, besides, nobody ever knows when he is in the Dative case, except he discover it by accident -- and then he does not know when or where it was that he got into it, or how long he has been in it, or how he is going to get out of it again. The Dative case is but an ornamental folly -- it is better to discard it.

In the next place, I would move the Verb further up to the front. You may load up with ever so good a Verb, but I notice that you never really bring down a subject with it at the present German range -- you only cripple it. So I insist that this important part of speech should be brought forward to a position where it may be easily seen with the naked eye.

Thirdly, I would import some strong words from the English tongue -- to swear with, and also to use in describing all sorts of vigorous things in a vigorous ways.

4. "Verdammt," and its variations and enlargements, are words which have plenty of meaning, but the sounds are so mild and ineffectual that German ladies can use them without sin. German ladies who could not be induced to commit a sin by any persuasion or compulsion, promptly rip out one of these harmless little words when they tear their dresses or don't like the soup. It sounds about as wicked as our "My gracious." German ladies are constantly saying, "Ach! Gott!" "Mein Gott!" "Gott in Himmel!" "Herr Gott" "Der Herr Jesus!" etc. They think our ladies have the same custom, perhaps; for I once heard a gentle and lovely old German lady say to a sweet young American girl: "The two languages are so alike -- how pleasant that is; we say `Ach! Gott!' you say `Goddamn.'"

Fourthly, I would reorganize the sexes, and distribute them accordingly to the will of the creator. This as a tribute of respect, if nothing else.

Fifthly, I would do away with those great long compounded words; or require the speaker to deliver them in sections, with intermissions for refreshments. To wholly do away with them would be best, for ideas are more easily received and digested when they come one at a time than when they come in bulk. Intellectual food is like any other; it is pleasanter and more beneficial to take it with a spoon than with a shovel.

Sixthly, I would require a speaker to stop when he is done, and not hang a string of those useless " haben sind gewesen gehabt haben geworden sein s" to the end of his oration. This sort of gewgaws undignify a speech, instead of adding a grace. They are, therefore, an offense, and should be discarded.

Seventhly, I would discard the Parenthesis. Also the reparenthesis, the re-reparenthesis, and the re-re-re-re-re-reparentheses, and likewise the final wide-reaching all-inclosing king-parenthesis. I would require every individual, be he high or low, to unfold a plain straightforward tale, or else coil it and sit on it and hold his peace. Infractions of this law should be punishable with death.

And eighthly, and last, I would retain Zug and Schlag , with their pendants, and discard the rest of the vocabulary. This would simplify the language.

I have now named what I regard as the most necessary and important changes. These are perhaps all I could be expected to name for nothing; but there are other suggestions which I can and will make in case my proposed application shall result in my being formally employed by the government in the work of reforming the language.

My philological studies have satisfied me that a gifted person ought to learn English (barring spelling and pronouncing) in thirty hours, French in thirty days, and German in thirty years. It seems manifest, then, that the latter tongue ought to be trimmed down and repaired. If it is to remain as it is, it ought to be gently and reverently set aside among the dead languages, for only the dead have time to learn it.

A Fourth of July Oration in the German Tongue, Delivered at a Banquet of the Anglo-American Club of Students by the Author of This Book

Gentlemen: Since I arrived, a month ago, in this old wonderland, this vast garden of Germany, my English tongue has so often proved a useless piece of baggage to me, and so troublesome to carry around, in a country where they haven't the checking system for luggage, that I finally set to work, and learned the German language. Also! Es freut mich dass dies so ist, denn es muss, in ein hauptsächlich degree, höflich sein, dass man auf ein occasion like this, sein Rede in die Sprache des Landes worin he boards, aussprechen soll. Dafür habe ich, aus reinische Verlegenheit -- no, Vergangenheit -- no, I mean Höflichkeit -- aus reinische Höflichkeit habe ich resolved to tackle this business in the German language, um Gottes willen! Also! Sie müssen so freundlich sein, und verzeih mich die interlarding von ein oder zwei Englischer Worte, hie und da, denn ich finde dass die deutsche is not a very copious language, and so when you've really got anything to say, you've got to draw on a language that can stand the strain.

Wenn haber man kann nicht meinem Rede Verstehen, so werde ich ihm später dasselbe übersetz, wenn er solche Dienst verlangen wollen haben werden sollen sein hätte. (I don't know what "wollen haben werden sollen sein hätte" means, but I notice they always put it at the end of a German sentence -- merely for general literary gorgeousness, I suppose.)

This is a great and justly honored day -- a day which is worthy of the veneration in which it is held by the true patriots of all climes and nationalities -- a day which offers a fruitful theme for thought and speech; und meinem Freunde -- no, mein en Freund en -- mein es Freund es -- well, take your choice, they're all the same price; I don't know which one is right -- also! ich habe gehabt haben worden gewesen sein, as Goethe says in his Paradise Lost -- ich -- ich -- that is to say -- ich -- but let us change cars.

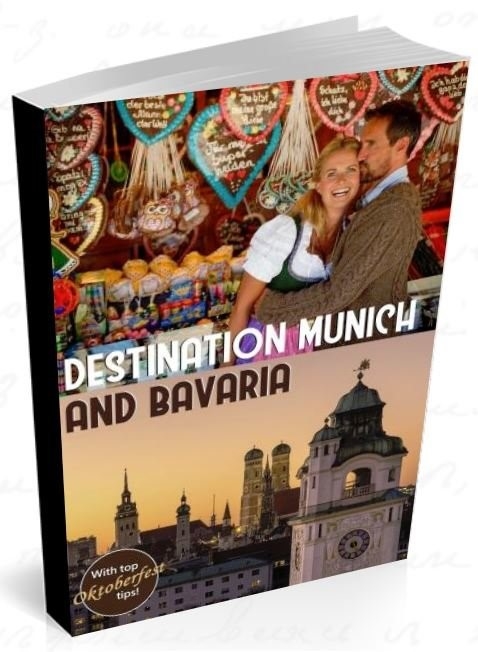

Do you like this site? Get the guidebook!

Destination Munich

Want to learn more about German/Bavarian culture and traditions?

• Go to the main Munich Backstory page. • Jump from Mark Twain's Essay on German back to Destination Munich Home

Readers' faves

- The web's best overview of the Munich Oktoberfest.

- Details of the beer tents, dates, times, FAQs, photos and plenty more.

- Oktoberfest songs

- My new sister site dedicated to the Music of Oktoberfest. Slur along to the most popular tunes - with German and English lyrics, and videos.

- Munich for kids

- Got the little ones along? Here's how to keep them busy.

- Eating out with kids in Munich guide to - 10 places parents won't want to miss

- Munich webcams

- See what's happening around town RIGHT NOW!

- Surfing Munich

- Riding the brakers in a landlocked city - you'll love this! One of the crazier things to do in Munich.

What's fresh

- The crazy ice-cream maker

- This great ice-cream cafe has flavours inclduding white sausage, Oktoberfest beer and pregnancy test.

- Munich Documentation Centre for the History of National Socialism

- A place to learn about and remember Germany's Nazi past.

- The top 10 tourist attractions in Munich

- What are the must-sees on a break to Munich? Don't miss these gems.

- 20 Facts on Germany

- Think you know Germany? Here are 20 fast facts about the powerhouse of Europe.

- German Dirndl Get the backstory behind the dress that launched a thousands hips.

- Kaltenberg Knights Tournament

- Europe's biggest middle-ages festival, coming this summer.

- Cheap Munich - 10 money saving travel tips

- Ideas for a cheap Munich visit.

- Top of page

- Comments? Questions?

- Privacy Policy

- About the author

- What's new on the site

- Worldwide travel sites

- Munich magazine

- Application process for Germany VISA

- Germany Travel Health Insurance

- Passport Requirements

- Visa Photo Requirements

- Germany Visa Fees

- Do I need a Visa for short stays in Germany?

- How to Get Flight Itinerary and Hotel Booking for Visa Application

- Germany Airport Transit Visa

- Germany Business VISA

- Guest Scientist VISA

- Germany Job Seeker Visa

- Medical Treatment VISA