- Our Mission

- What is a Sustainable Built Environment?

- Unlocking the Sustainable Development Goals

- News and Thought Leadership

- Our Annual Reports

- Why become a Green Building Council

- Partner with us

- Work with us

- Case Study Library

- Sustainable Building Certifications

- Advancing Net Zero

- Better Places for People

- Circularity Accelerator

- #BuildingLife

- Net Zero Carbon Buildings Commitment

- Regional Advocacy

- Sustainable Finance

- Corporate Advisory Board

- GBC CEO Network

- Global Directory of Green Building Councils

- Asia Pacific

- Middle East & North Africa

- Regional Leadership

Your lawyers since 1722

Publications.

Home > News and Thought Leadership > Sustainable and Affordable Housing Report

Sustainable and Affordable Housing Report

It is estimated that around 80% of cities worldwide do not have affordable housing options for the majority of their population (1). the world needs to provide two billion homes over the next 75 years — meaning 96,000 new affordable homes need to be built every day (2). the global housing crisis, interlinked with the dual crises of unprecedented climate change and biodiversity loss, is one of the greatest social challenges we are facing today. housing infrastructure can continue to exacerbate problems or can be part of the solution. the global building and construction industry needs a monumental shift. the ‘sustainable and affordable housing’ report challenges the widespread perception that affordable and sustainable housing is not a mass market solution. many of the solutions to the global housing crisis already exist. the case study content from five regions highlights cutting-edge built environment projects, making sustainable and affordable housing a reality for all — from 3d printed homes in kenya, community engagement and collaborative financing models in nepal, to disaster-resilience retrofits in the philippines. through this publication, worldgbc champions a unified vision for sustainable, affordable housing and spotlights best practice worldwide to demonstrate opportunities for success that could be scaled for greater impact. an analysis of case study data derives key calls to action for policy makers, the finance community, community approaches, and the design and construction industry. view the ipaper version of the report download the pdf version of the report references: european parliament, ‘access to decent and affordable housing for all’ (2020) wef, ‘the world needs to build 2 billion new homes over the next 80 years’ (2018) five key principles, co-developed by an international taskforce of green building councils and affordable housing experts, guide the analysis of best practice solutions across the globe, these are:, 1. habitability and comfort.

- Health and comfort: Enhance indoor environmental quality to boost occupants’ mental and physical wellbeing and reduce factors that can lead to viral transmission and ill health, by considering all relevant health and comfort determinants, including air, light, water, sanitation, acoustic, thermal, and visual comfort*.

- Outdoor environment: Enhance outdoor environmental quality, including access to nature and promote walkability*.

- Dignity: Enhance dignity, privacy, and security, providing enough space to prevent overcrowding.

- Rights: Protect against evictions, destruction, and demolition, with appropriate entitlements of land and property.

- Lifestyle: Encourage healthy occupant behaviour and lifestyle choices*.

Further Resources:

* Please see WorldGBC’s Health & Wellbeing Framework for more information on health, equity, and resilience strategies in the built environment

** Please see WorldGBC’s Resilience in the Built Environment Guide for more information about climate resilience and adaptation in the built environment

– IHRB’s Dignity by Design Framework for more information on each stage of the built environment lifecycle, aiming to minimise risks to people and maximise social outcomes.

– ICLEI’s Circular City Actions Framework for more information on a range of strategies and actions available to work towards circular development at the local level.

2. Community and Connectivity

- Inclusive design: Prioritise inclusion of citizens in the planning and design stages of community or project development to avoid issues of social unrest or displacement.

- Access to transport and services: Incorporate accessible transport systems into community or masterplan, to allow accessibility to employment, services, and amenities such as shops, schools, healthcare facilities and public areas.

- Culture and community: Foster inclusion and social equity, by enhancing equality, inclusivity, diversity, non-discriminatory, and culturally relevant environments that foster a sense of belonging.

3. Resilience and Adaptation to a Changing Climate

- Adaptability: Ensure housing is adaptable, durable, and easy to maintain through its lifecycle, to facilitate ease of retrofit and reuse**.

- Nature-based solutions: Enhance natural capital, maintaining and preserving ecological processes to support whole life impact on ecological health, prioritise the regeneration of ecosystem services, and enhance bioclimatic resilience.

- Safety: Ensure structural safety is met and designed to withstand climate change scenarios to offer long-standing usability.

- Hazard and disaster resilience: Consider extreme temperature change and weather conditions such as floods, wildfires, droughts, hurricanes, storms, and high winds**.

4. Economic Accessibility

- Net zero whole life emissions: Target whole life carbon emission reduction, working towards net zero operational and embodied carbon levels at building and community scales.

- Energy transition and efficiency: Support the energy transition away from fossil fuels and towards electrification through the generation and use of clean and renewables-powered electricity, demonstrating energy reduction through efficiency measures to reduce emissions and operational energy use and costs.

- Water: Reduce water footprint of materials and processes and ensure water efficiency in operation.

- Waste and materials: Support recycling and upcycling of materials through circular design principles.

5. Resource Efficiency and Circularity

- Purchase and leasing price: Support affordable purchase, upfront rental costs, with options to secure housing beyond direct payment.

- In-use costs: ensure accessible and affordable operation, maintenance, and ongoing improvement costs.

- Economic security: Ensure financial security and a suitable housing option for any income level, while supporting the progression of a growing household to a successively higher quality of living, habitat, and infrastructure.

- Living costs: Ensure access to affordable utilities and services to increase occupants’ discretionary income.

- Development costs: Source locally and utilise local industries to reduce building costs and support economic development.

Regional Snapshot

The ‘Sustainable and Affordable Housing’ report spotlights case studies from around the world which demonstrate innovative examples of sustainable and affordable housing. These case studies are showcased by region:

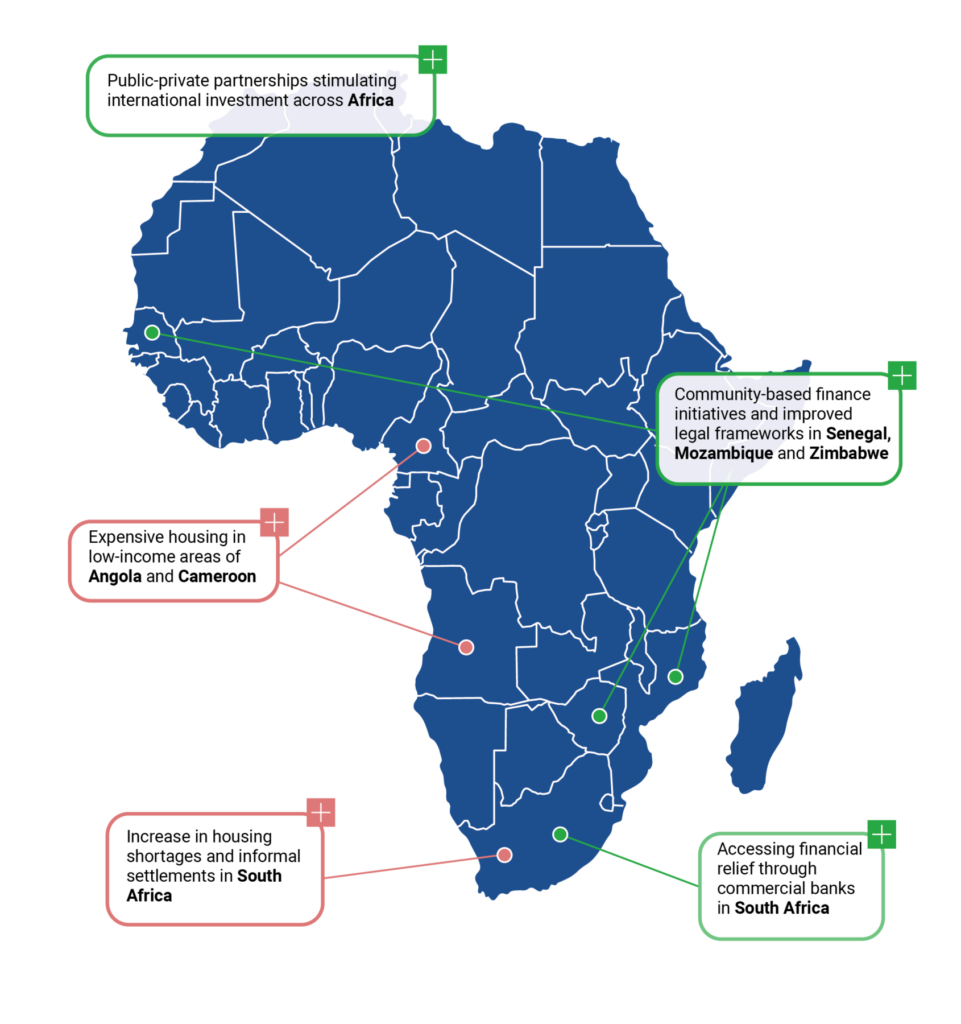

Africa Regional Snapshot

Challenges facing the housing sector

Africa is the most rural region in the world, yet has incredible diversity across the continent, with centres of wealth and urbanisation. The continent is also at the frontline of climate change impacts, such as droughts and expansion of desertification.

Driving the uptake of sustainable and affordable housing

In the last decade, there is a growing body of evidence of sustainable projects, policies and plans being implemented across the built environment in Africa.

Americas Regional Snapshot

The Americas region is the second most disaster prone region in the world, with 152 million people affected by over 1,200 natural disasters from the years 2000-2019; including floods, storms, droughts, wildfire, and extreme temperatures ( 41) .

A range of innovation and traditional financing, policy and development models are being utilised across the continent to drive affordable, sustainable housing across the Americas.

References:

41. OCHA, ‘Natural Disasters in Latin America and the Caribbean, 2000- 2019’ (2020)

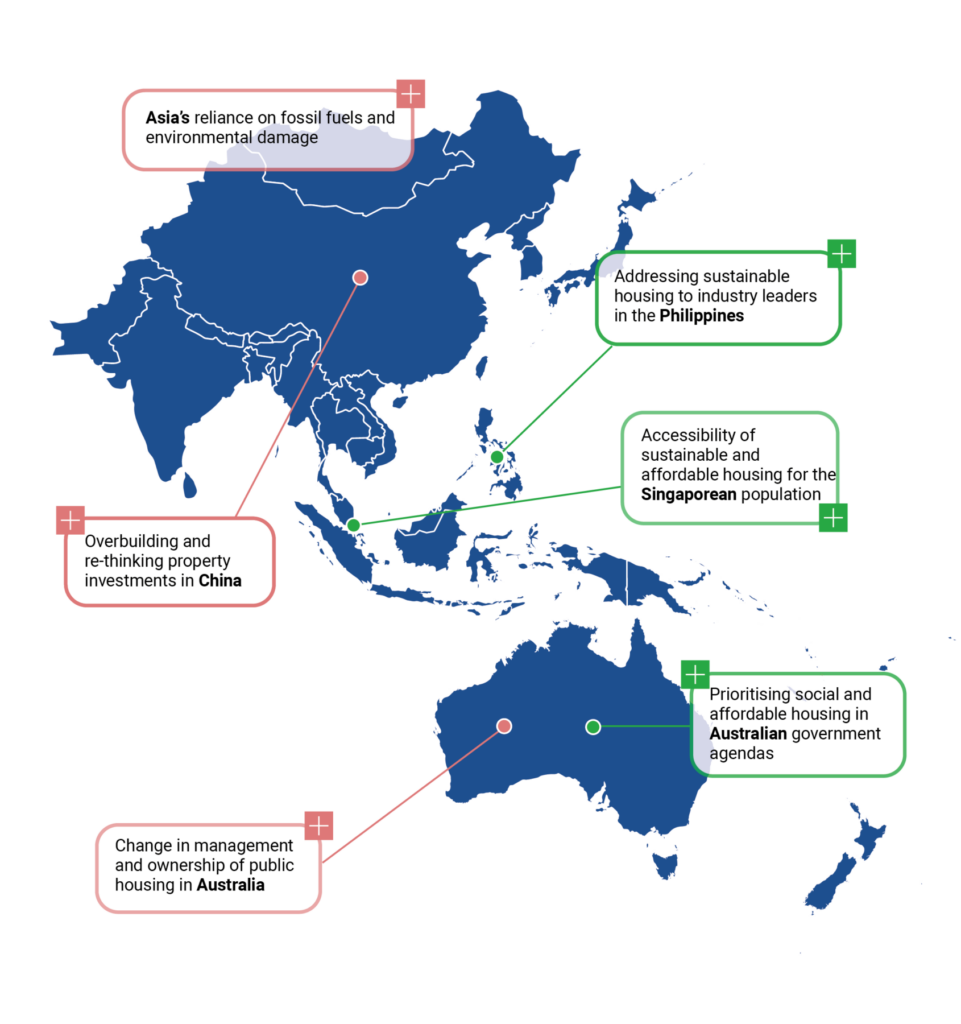

Asia Pacific Regional Snapshot

The continent of Asia is experiencing massive demographic changes, with the growing and urbanising populations of Asia’s developing nations presenting an urgent demand for sustainable and affordable housing. Across the entire continent, the physical impacts and risk of climate change have already been realised ( 62) .

Increasing the supply of sustainable and affordable housing has been a national priority for many governments in the Asia Pacific region, with a consistent message that countries need to build more, and an increase in private investors supporting local development.

62. UN Habitat, ‘pro-poor urban climate resilience in Asia and the pacific’ (2014)

Europe Regional Snapshot

The European region has the highest GDP per capita of any continent 80 , and yet only represents less than 10% of the world’s total population. However, most European countries are projected to experience a 20% decline in population by 2050 ( 81) .

There are many sophisticated examples of affordable and sustainable housing in Europe being driven through a range of channels, from policy to private funding. Concern about physical climate risk is recognised as a key driver for greater investment in the residential sector, alongside EU level policy driving retrofits as part of the ‘Green Deal’; the regional action plan for moving to a clean, circular economy while restoring biodiversity, cutting pollution, and reaching climate neutrality by 2050 ( 91) .

81. Eurostat, ‘Population projected to decline in two-thirds of EU regions’ (2021)

91. WorldGBC, ‘Building Life’ (2022)

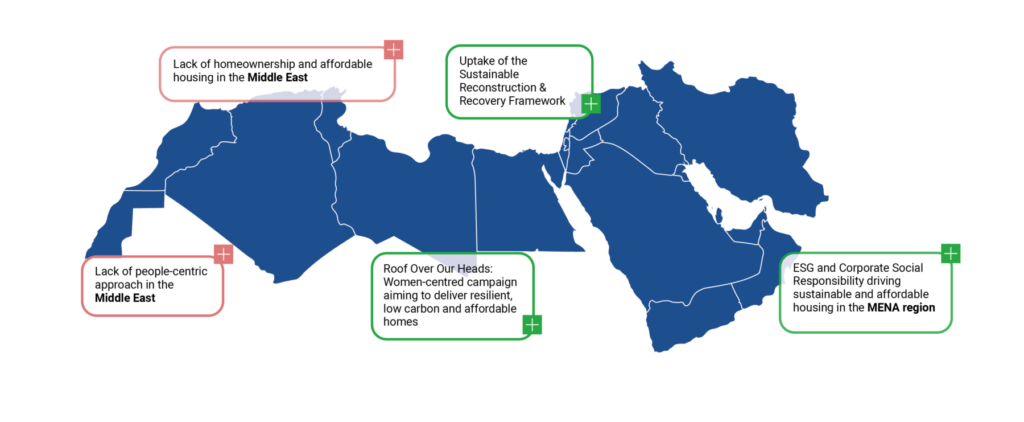

Middle East and North Africa Regional Snapshot

The Middle East is one of the most urbanised regions in the world, with over 56% of inhabitants living in cities. As average inhabitants grow younger and refugee populations increase, this is set to rise to 68% of total inhabitants, approximately 646 million people, living in cities by 2050. The housing demand will result in 70% of land use in most cities comprising housing ( 98) .

Varied approaches to sustainable, affordable housing can be observed, with greater or lesser degrees of government intervention in this area. The MENA region has strived to become more environmentally friendly, with record-breaking developments and a shift towards more sustainable practices in design and construction.

98. ESCWA, ‘Social Housing in the Arab Region: An Overview of Policies for Low- Income Households’ Access to Adequate Housing’ (2017)

World Green Building Council Suite 01, Suite 02, Fox Court, 14 Gray’s Inn Road, London, WC1X 8HN

- Privacy Overview

- Strictly Necessary Cookies

- 3rd Party Cookies

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

If you disable this cookie, we will not be able to save your preferences. This means that every time you visit this website you will need to enable or disable cookies again.

This website uses Google Analytics to collect anonymous information such as the number of visitors to the site, and the most popular pages.

Keeping this cookie enabled helps us to improve our website.

Please enable Strictly Necessary Cookies first so that we can save your preferences!

- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Policy

- Self-Archiving Policy

- About Policy and Society

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Indian housing policy, pmay-u, and clss, social construction of target population framework, discussions and conclusion, acknowledgement, conflict of interest.

- < Previous

Exclusion by design: a case study of an Indian urban housing subsidy scheme

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Manav Khaire, Exclusion by design: a case study of an Indian urban housing subsidy scheme, Policy and Society , Volume 42, Issue 4, December 2023, Pages 493–505, https://doi.org/10.1093/polsoc/puad015

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (Urban)—Housing for All mission (PMAY-U), a flagship mission of the Government of India, aims to address the need for affordable housing in urban areas through five different schemes. One of these schemes is a housing subsidy scheme, the Credit Linked Subsidy Scheme (CLSS), which has significantly contributed to the success of PMAY-U. However, the design of the CLSS scheme favors households considered creditworthy, with stable and secure income streams. This article examines the gap between the policy design and practice of the CLSS scheme to explore how biases get embedded into the policy, resulting in the exclusion of economically vulnerable households. Schneider and Ingram’s Social Construction of Target Population (SCTP) framework is used to identify the target groups involved in the CLSS policy chain. These target groups and policymakers were interviewed to understand their interpretations of the concept of affordable housing. Using a relational lens, these interpretations are compared to know how the meanings of affordable housing get represented within CLSS policy documents. The analysis presents two key insights. First, the power and interests of the target groups predict their representation in policy design and policymaking. Second, privatized implementation design of the subsidy scheme embeds negative selectivism creating exclusionary tendencies in the CLSS design. Lastly, given the shrinking of the welfare state across the globe, this study raises the critical question of “who benefits and who loses?” while challenging the normative aspects of the policy goal of affordable housing.

The world’s urban centers are experiencing a housing affordability crisis characterized by growing income inequality and rising housing costs ( Saiz, 2023 ). This crisis reflects the alarming trend of housing-related expenses increasing at a faster rate than salaries and wages in urban areas ( Wetzstein, 2017 ). In response, national governments worldwide adopt a range of affordable housing policy options targeting various supply and demand aspects of housing markets. Saiz’s (2023) comprehensive global review of these policy options reported that providing direct demand-side subsidies to homebuyers is a prevalent approach in national housing policies. Since the provision of this subsidy is means-tested, identifying and targeting beneficiaries accurately is crucial for policymakers to prevent the misallocation of policy benefits. Therefore, ensuring appropriate targeting in line with policy design is as important as the successful outcome of the subsidy policy itself. This paper presents a case study of an Indian housing subsidy scheme to elucidate the mechanisms behind the potential diversion of policy benefits from the intended targeted groups.

Currently, the Indian government operates a national-level housing mission known as the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (Urban)—Housing for All mission (PMAY-U), launched by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA) in 2015. The PMAY-U, implemented through five schemes, 1 is recognized as one of the largest affordable housing programs globally, with the central objective “of addressing the affordable housing requirements in urban areas” ( MoHUA, 2021 , p. 1). While the implementation time frame for PMAY-U spans from 2015 to 2022, only the housing subsidy scheme, called the Credit Linked Subsidy Scheme (CLSS), concluded in March 2022, while the implementation of the other four schemes has been extended till December 2024. Khaire and Jha (2022a) reported the uneven outcome of PMAY-U schemes, disproportionately favoring two demand-side schemes, including CLSS. Among the five schemes, CLSS has stood out in terms of performance over the years. The allocation of funds for CLSS has increased sevenfold from 2018 to 2022, making it the most successful scheme under PMAY-U. Also, in terms of funds consumed, as of June 2022, CLSS accounted for ₹ 0.5 trillion (US$6.6 billion) 2 out of the total funds released under PMAY-U, which stood at ₹ 1.2 trillion (US$14.5 billion), representing 46% of the total funds ( MoHUA, 2022 ).

Although CLSS was originally targeted at low-income households, 3 the scheme was extended to include the Middle-Income Group (MIG) 4 households under two categories: MIG-I and MIG-II. This arrangement lasted for 4 years, from 2017 to 2021. As of February 2023, 0.6 million MIG households benefited from CLSS out of a total of 2.5 million CLSS beneficiaries, which is almost 24% of total beneficiaries ( MoHUA, 2023 ). A closer examination of the beneficiary profile of CLSS reveals that they belong to household segments deemed creditworthy and have a stable and secure income stream. Holding a mortgage is a prerequisite for availing of a subsidy under CLSS. The mortgage underwriting criteria include long-term credit, large loan sizes, and stringent repayment methods ( Smets, 1997 ) that require households to have sufficient income levels, a regular flow of income, verifiable sources of income, and acceptable collateral. These lending criteria are tailored as per the income profile of middle- and higher-income households, which tends to exclude low-income households, especially those engaged in informal occupations. Any household unable to meet these lending criteria is automatically excluded from the policy’s scope. This suggests a structural bias in the design of the CLSS policy, which is the subject of investigation in this paper. While the CLSS policy design claims to target the needs of economically vulnerable low-income households, in practice, the benefits of the scheme tend to favor economically secure households. Given this disparity between policy design and practice, the following research question guides the investigation: “What are the mechanisms through which exclusionary effects get embedded into the policy design of the CLSS?”

I use a relational lens in conjunction with Schneider & Ingram’s (1997) Social Construction of Target Population (SCTP) framework to examine how the target groups and their power influence the policy design of the CLSS. The relational lens, while probing the lack of fit between policy as practiced and policy as designed ( Sabatier, 1986 ), focuses not only on the outcomes but also on the interrelationships and transactions among the policy actors ( Lejano, 2021 ). Specifically, Lejano (2021) suggested that “policies, as designed, are modified according to the interactions, negotiations, and relationships among the policy actors” (p. 2). The policy actors involved in the policy chain have their own interests and agency, and policy emerges through their interactions, making it a relational process.

The inquiry proceeds in three steps. First, the readers are introduced to the general structure of Indian housing policy and the policy chain of CLSS, which is the housing subsidy scheme under scrutiny. Second, a discussion on Schneider & Ingram’s (1997) SCTP is presented, followed by the identification of the target groups of the CLSS using the classification system provided in the framework. Third, a relational analysis of the interview data of the target groups is presented, examining the diverse and conflicting interpretations of the term “affordable housing” held by the target groups, which reflects their roles and interests within the CLSS. These steps collectively help uncover how the understandings of affordable housing held by politically dominant target groups and their business interests enter into the policy design of CLSS. Lastly, the study’s insights are discussed to highlight the mechanisms through which CLSS embeds exclusionary design.

Indian housing policy operates on a three-tier system, with housing responsibilities distributed at three levels of government: central, state, and local. Housing policy is crafted at the national level by the central government after gathering inputs from state and local levels, signifying a top-down policy approach ( Tiwari & Rao, 2016 ). Indian housing policy has moved in line with the international discourse of housing policy that has shifted from housing provider to housing market enabler ( Yoshino & Helble, 2016 ). The Indian housing policy is broadly characterized by a homeownership bias and market-based policy interventions, especially in urban areas ( Khaire & Jha, 2022b ). Given the market-based housing delivery system in India, the issue of housing affordability becomes a pressing concern for households as they need to depend on the private market for their housing consumption.

India has a long history of urban housing schemes that have mostly remained targeted (at specific income groups) and disjointed (standalone) ( Nallathiga, 2007 ; Sivam & Karuppannan, 2002 ), primarily serving low-income groups. A major departure from this approach was the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM) launched in 2005, which focused on overall urban development, integrating different domains of housing, water, sanitation, and other urban infrastructure ( MoHUA, 2005 ). The JNNURM operated successfully until 2014, facilitating sustainable urban transformation for states and Urban Local Bodies (ULBs), but exhibited a bias toward large cities and a decreasing proportion of spending on the urban poor ( Kundu, 2014 ). In 2015, the JNNURM was repurposed into several sector-specific schemes, such as the Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation, which focused on water supply and sewerage improvement. The PMAY-U, launched in 2015, subsumed the erstwhile housing schemes such as Basic Services to the Urban Poor and Integrated Housing and Slum Development Programme under the JNNURM along with other independent schemes such as Rajiv Awas Yojana and Rajiv Rin Yojana (RRY) ( MoHUA, 2016a ).

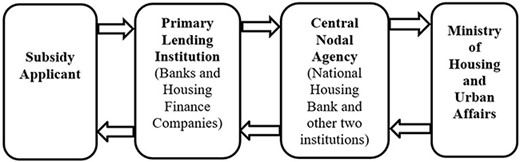

The genesis of CLSS can be traced back to the Interest Subsidy Scheme for Housing the Urban Poor, which was piloted in 2009 and later renamed the RRY in 2013. The RRY was implemented across all the urban areas, providing an interest subsidy on the loans granted to the Economically Weaker Section (EWS) and the Lower Income Group (LIG) households. In 2015, all previous housing schemes were subsumed under PMAY-U, with interest subsidy schemes renamed CLSS. Figure 1 illustrates the policy chain of CLSS. As a demand-side interest subsidy scheme, CLSS offers interest subsidies of up to ₹ 0.267 million (US$3,236) on home loans taken by beneficiaries. The primary goal of CLSS is to enhance housing affordability for beneficiaries through direct cash assistance. It is fully funded by the central government and does not involve participation from state- or local-level governments.

CLSS policy chain, adapted from the CLSS portal by MoHUA (2023) .

Household applicants interested in availing the CLSS need to apply for a subsidy at the lending institution where they have a home loan account. These institutions conduct means-testing eligibility checks and then forward the applications to central nodal agencies appointed by the government. After eligibility checks are performed at different levels, the housing subsidy is disbursed by the nodal agencies directly to the home loan accounts of the beneficiaries through the lending institutions. There are certain eligibility criteria based on the socioeconomic characteristics of households: (1) The household should belong to the EWS or LIG or MIG income group (see Footnote 3), (2) a female should be the owner or co-owner of the home, and (3) the household should be a first-time homebuyer, i.e., they should not own a home in their name in any part of the country ( MoHUA, 2021 ).

There have been limited studies analyzing the outcomes of PMAY-U and its different schemes. Mitra (2022) analyzed the implementation dynamics of PMAY-U in the state of Madhya Pradesh and reported that the scheme providing a subsidy for the construction or enhancement of houses experienced increased uptake, whereas the slum redevelopment scheme performed poorly. The study recommends a coordinated dialogue between the Centre, State, and ULBs to improve the implementation outcomes in small and medium towns in India. Harish and Raveendran (2023) reported low uptake of the slum redevelopment scheme due to limited rent gaps on slum lands across Indian cities. In another instance, Khaire and Jha (2022a) examined the outcome of PMAY-U and reported that two demand-side schemes, CLSS and the scheme providing a subsidy for the construction or enhancement of houses, accounted for 80% of funds allocation, while other three schemes performed poorly. A couple of studies that attempted to understand the effectiveness of PMAY-U with respect to catering to the lowest quartile of the urban population reported that the mission is unable to serve them ( Bhate & Samuel, 2023 ; Kumar & Shukla, 2022 ). Kundu and Kumar (2017) examined the design of CLSS and highlighted that expansion of eligibility criteria to include more beneficiaries might increase the chances of MIGs appropriating housing subsidies, further diluting the pro-poor agenda of the scheme. The current study builds on the existing body of research on the effectiveness and outcomes of PMAY-U and contributes to the literature on housing policy analysis.

The policy design approach addresses the factors that influence the design, selection, implementation, and evaluation of public policies ( Ingram et al., 2007 ). It differs significantly from the mainstream policy process approaches to policy analysis by emphasizing normative aspects in policy design that explore the role of human nature and its impact on policy formulation ( Schneider & Ingram, 1993 ). One prominent policy design approach is the theory of SCTP proposed by Schneider and Ingram (1993) , which suggests that differences in the power and resources of stakeholders involved in a specific policy shape the policy designs. In other words, as a response to Lasswell’s (2018) perennial question in policy analysis—“Who gets what, when, and how?” — Schneider and Ingram argue that it depends on the social construction (social reputation) of the target groups as either “deserving” or “undeserving” that decides whether these groups receive “benefits” or “burdens” in policy implementation ( Schneider & Ingram, 1993 ). This is succinctly captured in the target population proposition of the theory, which states that policy design is a function of social construction and power ( Pierce et al., 2014 ).

The SCTP framework has been widely applied in various national and international contexts across numerous policy domains such as social welfare, health, criminal justice, immigration, education, and housing ( Pierce et al., 2014 ). In addition to theoretical contributions, many of these studies utilize the core proposition of the SCTP framework, which depicts a field of the target groups with differing political power and their positive or negative image ( Pierce et al., 2014 ; Schneider & Sidney, 2009 ). These studies, along with other research applying the feed-forward proposition (focusing on policy consequences of policy design), mainly attempt to understand the causal mechanisms affecting changes in social construction or power that may lead to changes in policy design. Another less-used aspect of the SCTP framework focuses on the social construction of knowledge in the policy process that directs attention to processes of problem definition and interpretations of policy issues ( Schneider & Sidney, 2009 ). Furthermore, a clear link between knowledge construction and power is established, enabling researchers to predict how policy designs are shaped due to the interactions between the political power of various target groups and their social constructions (social reputations). While emphasizing the interactional aspects of policy design, the SCTP framework foregrounds the assumption that policy formulation is contingent on competing interests and the outcome of political and ideological conflicts ( Jacobs & Manzi, 1996 ). Therefore, while enabling the relational dimension of policy design, the SCTP framework provides a theoretically grounded lens to analyze policy design and practice. In applying the SCTP framework through a relational lens, this paper seeks to uncover mechanisms that explain exclusionary aspects of the policy design of CLSS.

Public policies usually identify and mark certain populations or groups, referred to as target groups, to deliver the policy outcomes (benefits or burdens) to them. According to Ingram and Schneider (1991) , target populations are “the persons, groups, or firms selected for behavioral change by public policy initiatives such as statutes, agency guidelines, or operational programs” (p. 334). In the SCTP framework, the target groups are explained using a 2 × 2 matrix with political power on the vertical axis and social construction on the horizontal axis.

Accordingly, the target groups are classified into four categories: “advantaged,” “contenders,” “dependents,” and “deviants” ( Ingram & Schneider, 1991 ; Schneider & Ingram, 1997 ; Schneider & Ingram, 1993 ). The “advantaged” group has a positive social construction and a strong political power that enable them to receive a high share of benefits and access, for example, older people and businesses. The next group, categorized as “contenders,” also exhibits strong political power but is negatively constructed. This group includes groups such as the insurance industry, the rich population, and big unions, but they are considered undeserving due to their negative social construction. The “dependents” have weak political power and are positively constructed. This group includes target groups such as mothers and disabled people, who end up receiving fewer benefits and burdens than the earlier two groups. Lastly, the “deviants” have weak political power and a negative social construction that qualify them to receive many burdens from policies. This group comprises social groups like criminals, drug addicts, or gangs ( Schneider & Ingram, 1993 ).

Application of the SCTP framework to the CLSS: government and target groups

The target group classification provided by the SCTP framework can be applied to any policy domain under consideration. In the case of the CLSS policy chain ( Figure 1 ), the most important stakeholder is the MoHUA, which is responsible for policymaking and implementing housing policies on national, regional, and local levels. Other public institutions are the National Housing Bank, Housing and Urban Development Corporation Ltd, and the State Bank of India, which act as nodal agencies for implementation.

Table 1 represents the mapping of different target groups identified earlier within the social construction framework as applied to the CLSS context. The “advantaged” group includes the builders and real estate developers who are responsible for constructing and delivering the housing stock. According to the Indian Real Estate Industry Report 2022 published by the India Brand Equity Foundation, the real estate sector is estimated to reach a market size of US$1 trillion by 2030, and by 2025, it is estimated to contribute around 13% of gross domestic product of India ( IBEF, 2022 ). Given the vital contribution to the economy, this target group is positively viewed in the policy design and has strong political power.

The political power of target populations by their social construction.

Source . Adapted from Schneider and Ingram (1993) .

Another target group considered advantaged is the Higher-Income Group and MIG households, considered the real demand generators in the housing markets. Some authors have also identified the middle-class group as an advantaged group in the context of urban revitalization policy ( Camou, 2005 ) and the Fair Housing Act ( Trochmann, 2021 ) in the United States. This group is constructed as deserving and intelligent, contributing positively to the overall housing economy, rather vital to the demand–supply equilibrium of the housing market. They receive several home-loan-based tax benefits, such as a deduction on interest paid on a home loan, a deduction on principal repayment, and a deduction for stamp duty and registration charges.

The lending institutions such as banks and housing finance companies (HFCs) responsible for providing housing finance to households can be categorized as the “contenders.” Due to the negative construction, they do not receive the benefits openly but instead sub-rosa (done in secret) benefits ( Schneider & Ingram, 1993 , p. 338). The target populations identified using the SCTP theory do not always follow strict and static characterizations; instead, recognizing a specific group under the SCTP nomenclature is highly context dependent. For instance, in the housing policy research domain, one study identifies the lending institutions such as banks as contenders ( Hunter & Nixon, 1999 ), while another study identifies banks as advantaged ( Drew, 2013 ). In the context of this case study on CLSS, although lending institutions are a part of the policy chain, they are not intended to receive direct benefits of the scheme owing to their negative social construction. Therefore, lending institutions are categorized as the contenders.

CLSS classifies the low-income households belonging to EWS and LIG as the policy targets who can be identified as “dependents.” According to the SCTP theory, “they must apply to the agency for benefits (rather than being sought out through outreach programs) and require them to admit their dependency status” ( Schneider & Ingram, 1993 , p. 342). Similar categorization of economically poor groups as dependents are observed in various studies in the context of the childcare subsidy scheme in Ireland ( Hynes & Hayes, 2011 ), the welfare reform act in the United States ( Chanley & Alozie, 2001 ), and low-income homeownership policy in the United States ( Drew, 2013 ).

Data and procedure

The data for the study are comprised of interviews with stakeholders documenting their subjective meanings of the term “affordable housing.” These interviews were focused on understanding how they perceived the term “affordable housing,” mainly to capture and examine the varying and, at times, competing meanings of the term located across the target groups. A total of 48 semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted in person, and each lasted about 40–60 min. The interviews were conducted from January 2022 to July 2022 in the Palghar district under the Mumbai Metropolitan Region, where the CLSS was operating. Acknowledging stakeholders’ different social locations and institutional affiliations, the questions were open-ended and tailored as per their role in the policy chain of the CLSS. The interviews of the target groups included 12 policymakers and government officials, 12 developers and builders operating in the affordable and mid-segment housing with similar financial capacity, 12 employees of three different mortgage lending institutions, and 12 CLSS beneficiaries belonging to the low-income segment with annual income less than ₹ 0.45 million (US$5,441). All the interviews were pivoted around to three sets of questions: (1) What is the meaning of affordable housing? (2) What is their role in the CLSS policy chain? And (3) how has CLSS contributed to the goal of ameliorating the issue of affordable housing for their work and business (for policymakers, builders, and banks) and life in general (for households)?

The interview data were analyzed using a relational lens that enabled researchers to focus on the transactional nature of relationships between various target groups. A relational lens was also in correspondence with the social construction approach as it enabled probing into “how policy emerges from the interaction of different constructed identities” ( Lejano, 2021 , p. 1). This relational and comparative analysis may offer insights into the intentions and logic behind the target groups’ active involvement in CLSS implementation.

Data analysis

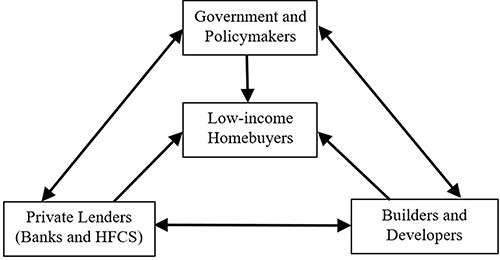

Figure 2 depicts the flow of the meaning of affordability from the government to the end beneficiaries through other target groups. The arrows show the exchange of data and information either one-way or two-way, depending on the parties involved. The interaction of the meanings of the term “affordable housing” at the site of the policy process leads to the final operationalization of the policy goal of affordability. The relational production of the policy goal is directly linked to the power of the target groups, which, in turn, shapes policy design. Concurrently, politically weaker groups such as low-income households fail to push their meanings of policy goals as their opinions are considered less reliable or irrelevant ( Schneider & Sidney, 2009 ), and they cannot mobilize and represent their concerns.

The flow of meanings of the term “affordable housing” among stakeholders.

Policymakers: affordable housing as a policy goal

When asked about the meaning of affordable housing, all the 12 policymakers interviewed fell back on the policy documents while explaining the term. In the context of the implementation of CLSS, affordability was defined in terms of the policy goal of the scheme, which proposes an improvement in the housing affordability of the beneficiaries through interest subsidy on home loans. As one respondent described:

Affordable housing is a complex issue. Although we generally say that a house with a certain price, let’s say ₹ 2 million (US$ 24,183) to ₹ 3 million (US$ 36,275), is affordable, ultimately, it is about the income capacity of people for paying toward housing. CLSS tries to improve the affordable housing segment by providing interest subsidies.

The above account of affordable housing carries two distinct approaches to defining affordability. First, it is defined with a material understanding of housing, considering it as a single unit with a certain price threshold that is deemed affordable. Second, it is explained in terms of an individual’s income, invoking their capacity to afford housing that hints at an individualist approach. Together, the term “affordable housing” is understood in the context of the welfarist framework of housing policy. So, while defining affordable housing, the policy captured both the housing aspect (materialist) and income aspect (individualist). One respondent indicated a specific definition of the term “affordable housing” from the policy document:

The Task Force suggest following core criteria to be adopted while defining “affordable housing:” (1) sizes of EWS and LIG dwelling units and method of measurement (carpet area), (2) income criteria based on income ceiling of households, and (3) affordability, borrowing capacity and house price-to- income multiples. ( MoHUA, 2012 , p. 5)

These criteria are not definitive but rather given in terms of ranges to allow flexibility to implementation agencies working on the ground for housing policy delivery ( MoHUA, 2012 ). So, by design, there is a conceptual vagueness associated with “affordable housing” in-built into the policy documents. The final meaning only takes shape when the actual transaction of policy beneficiary selection takes place and when the implementation agency interacts with the beneficiary on the ground. Therefore, this specific space where all this eligibility criteria assessment takes place becomes a very important site of inquiry. In particular, the role of implementation agencies becomes paramount as they enable the access point for the beneficiaries.

Although the CLSS initially targeted EWS and LIG households, the benefits were also extended to the MIG groups for 4 years, from 2017 to 2021. When asked about the possible drift of policy goals from earlier objective, one of the respondents shared the specific reason behind this step:

This step was taken to stimulate demand for affordable housing, provide stimulus to the real estate sector, and generate employment in construction and other allied sectors like cement, steel, paint, sanitary ware, and transport.

The extension of CLSS benefits to include MIG households proved successful and was welcomed by all the target groups. The policymakers were able to push to extend the scheme benefits to the advantaged group (MIG) under the pretext of economic development. However, Kundu and Kumar (2017) cautioned about the dilution of the pro-poor agenda of the scheme. The PMAY-U policy texts also indicated this drift in policy goals. In 2016, the broad objective of PMAY-U was to “address the housing requirement of urban poor including slum dwellers” ( MoHUA, 2016b ), which was changed in 2021 to “address the affordable housing requirement in urban areas” ( MoHUA, 2021 ). The change of objective from specific to broad indicated the evolution of policy from targeting the low-income population to pushing affordable housing demand that would cater to MIG and the developers (advantaged group).

Private lenders: affordable housing and risk assessment criteria

Private lenders (banks and HFCs) form the key component of privatized implementation strategy used in CLSS, which involves private player participation in policy implementation and delivery ( Schneider & Ingram, 1997 ). Private lenders’ interaction with the beneficiary constitutes a site for policy delivery of subsidy. For the lenders, the term “affordable housing” directly concerns affordability, which refers to creditworthiness assessment criteria that they employ during the underwriting process to determine financial risks posed by individuals. When asked about the general meaning of affordable housing, one of the credit managers of a lending institution connected it to the concept of affordability:

For us, a customer should be able to pay for other household necessities after paying for housing costs (EMI). Therefore, total household income and expenses are what we look at to understand what level of repayment capacity they have. We are concerned more with the loan amount and repayment capacity.

This is a general perception of officials about affordability, but when asked about affordability from the perspective of lending institutions, they introduced credit risk assessment as a key concern. As a lending institution, they must subject each applicant to a creditworthiness check to know their repayment capacity. These are objective criteria that assess the applicant’s income and liabilities to ascertain whether they can afford to get new credit. A credit officer shared that

There are two most important documents that we check during creditworthiness check. One is Income Tax Return (ITR) form that contains exact information individuals’ income and taxes paid by them. Second is their bank transaction detail for the past year. These two documents are enough for us to gauge the repayment capacity of the applicant.

Once the credit officers correctly understand the applicant’s income, expenses, and liabilities, they start the next step of ascertaining how much monthly repayment the applicant can make. The repayment capacity is determined by subtracting all monthly expenses (on food, education, health, energy, and other miscellaneous items) from the monthly net income (take-home salary after deducting taxes). This is the amount that a household can commit toward repayment of any loan they take that also decides the maximum loan amount that can be extended to the applicant by the lender. Several respondents shared that the CLSS has been important for lowering household credit burden. One of the lending institution employees shared an experience related to the financial stress faced by a customer:

One customer was facing difficulty with EMI repayment. After they received the subsidy, the EMI amount reduced, which the customer could manage. This subsidy amount acted as a cushion.

This, in turn, also helps in mitigating credit risk from the lenders’ perspective, specifically for low-income households facing financial issues. In sum, the concept of affordable housing boils down to the credit risk assessment criteria and mitigation of credit risk for the lenders.

Builders and developers: affordable housing as a business opportunity

Builders and developers engaged in the production of affordable housing refer to the selling price of housing they produce and the target customer they cater to. This way of referring to affordable housing from the perspective of end customers reflects clarity in their thinking toward their business, with their target customers being low-income households. However, in practice, they also cater to high-income groups who are second- or third-home buyers. Although high-income groups do not form the intended target customer, they form an important part of sustaining the business. As one of the builders shared:

For any project, we definitely need confirmed bookings that cover our operating expenses. This is why we also approach high-income individuals who buy some units and wait for price appreciation over a period of project completion. On average, our customer base includes 40–50% of high-income individuals.

Builders and developers consider CLSS an effective intervention for generating affordable housing demand. It was considered a much-needed stimulus to the real estate sector, with its benefits trickling down to other ancillary industries. Several respondents echoed the opinion of one of the developers:

CLSS has been a boon for the real estate sector and homebuyers. It acted as a catalyst for the affordable housing segment and the 200 allied industries.

Furthermore, the scheme extended to include the MIG population received unequivocal support from the developer community. The subsidy from CLSS and the lowering of mortgage rates created a positive consumer sentiment. As shared by one of the developers:

The extension of CLSS for MIG attracts many fence-sitters to add to the affordable housing demand. Our builder community hopes to see the extension of this scheme in future.

Usually, affordable and mid-segment developers operate on thin margins and low volumes, which make them very sensitive to variations in input costs. Although the small builders cater to low-income households in the affordable housing sector, their primary objective is to generate enough profit margins to keep their business sustainable. This market logic undergirds how private players engaged in producing affordable housing perceive it within the context of operating their business profitably.

Low-income households: between aspirations and affordability

Analysis of the interviews with 12 low-income CLSS beneficiaries suggests that affordable housing, and specifically affordability, has a very subjective and personalized meaning for them. When specifically asked about how they understand the term “affordable housing,” most households could not express its exact meaning. One of the respondents initially shared the general meaning of indicating that affordable housing is low-priced housing that is affordable to poor households. When further probed about what is the specific individualized meaning, they shared the following understanding:

Affordable housing for me is the house that we can afford to buy. It basically is “what fits our budget.”

All the study participants echoed this understanding that affordable housing is “what fits our budget” while sharing their views. It indicates that some thought process akin to self-assessment goes in the background while thinking about affordable housing. This assessment considers the household’s financial position comprising their assets, liabilities, savings, income, and expenditure. When any household faces a question of whether something is affordable or not, they assess their current financial position to gauge how much money they can commit toward buying something. This subjective assessment also differs for various goods under question, as one of the participants shared:

We will not think much if we are buying a mobile or television. But, if we want to buy a car or a house, then we look at each and every aspect of our finances, right from past savings to future expenses.

Any form of financial subsidy like CLSS facilitates the self-assessment process; therefore, it is quite popular among low-income households. Some respondents also shared their concerns about accessibility to the subsidy having a prerequisite of a home loan from formal markets. One of the households shared a contrasting experience with their friend:

My friend and I, both of us applied for home loan after hearing about CLSS. I got the loan and subsidy within 10 months, but my friend is unable to get the home loan passed in the first place. Bank people say that his income documents are not clear.

In cases where people cannot access home loans through formal markets, lenders’ credit risk assessment takes precedence over the households’ self-assessment to apply for CLSS. In sum, availing of a home loan through formal lending institutions is as critical as identifying the right home after self-assessment to become eligible for the CLSS.

Analyzing the meanings of affordable housing held by different target groups with a relational lens helps to answer the central concern of the paper: What are the mechanisms through which certain meanings of affordable housing are represented in the CLSS design? The following subsection discusses two ways in which the target groups are able to shape the scheme design.

Alignment of interests of the powerful target groups

According to Schneider & Ingram (1993 , 1997) , the “advantaged” groups are powerful and positively constructed groups with substantial resources to influence policy to suit their interests. Affordable housing builders and developers are supply-side players engaged in the production of housing stock. Their business and policy interests are represented by organizations such as the National Real Estate Development Council and the Confederation of Real Estate Developers’ Association of India. They have relatively better access to various policymakers and participate in various consultations with the MoHUA regarding housing policy formulations that benefit the real estate sector. Another group qualifying as an “advantaged” group is MIG, representing the demand-side participation in the housing market. Policymakers were able to push to extend the scheme benefits to the advantaged group (MIG) under the pretext of economic development.

Private lenders, identified as “contenders,” are critical to the functioning of housing finance, which is a crucial part of any economy. They actively shape housing finance policies through government consultations and serve as key implementation partners in the CLSS, and they continuously work with the policymakers for smooth policy delivery. In contrast, “dependents,” such as low-income beneficiaries, have weak political power and struggle to represent their interests on policy design platforms ( Schneider & Ingram, 1993 , 1997 ). Dependents like low-income beneficiaries often rely on advocacy groups to voice collective concerns. However, in the context of the CLSS, there are no such collective platforms for representation. Among all the target groups, dependents (low-income households) have limited representation in the Indian housing policy design deliberation.

Looking closely at the target groups’ interpretations of affordable housing carried by the advantaged group (builders and developers) and the contender group (private lenders), we can observe a convergence of their business interests. Their interpretations of affordable housing as purely a business goal with financial interests align and complement each other. For instance, builders and developers of affordable housing depend on private lenders for financing their projects as well as lending to their prospective clients. Similarly, lenders depend on the builders and developers to complete the affordable housing project in a timely manner. It creates a mutually symbiotic relationship in which both groups depend on each other to realize their business goals. Also, the policymakers interpreting affordable housing as a policy goal are interested in increasing the uptake of the CLSS. For this, they must depend on the builders, developers, and private lenders to implement the scheme seamlessly. Therefore, the alignment of interest of these three target groups requires them to work together and represent their mutually reinforcing interpretations of affordable housing within the CLSS design. On the other hand, the interpretations of affordable housing held by low-income households fail to find a representation in this policy space.

Privatized implementation design and negative selectivism

The CLSS uses a privatized implementation design ( Schneider & Ingram, 1997 ), in which the subsidy is channeled to low-income beneficiary households through private lenders. Additionally, the most important task of means-testing is given to private lenders. Looking closely, we can identify two stages that any household goes through. First, lenders undertake a creditworthiness check before sanctioning the home loan. The prospective beneficiaries can apply only for the housing subsidy after getting the home loan. This means that becoming a homebuyer is the first latent eligibility criteria. After a homebuyer applies for a subsidy, lenders check for eligibility criteria prescribed by the policy document related to the income threshold for EWS and LIG households.

The stage of becoming a homebuyer, which acts as a latent criterion, occurs outside the policy chain of the subsidy scheme. Here, the private lender is acting in their business interest to minimize the financial risk the home loan applicant poses. In some ways, this stage acts as indirect eligibility criteria totally governed by lenders’ economic interests. Private lenders have full control over this stage, which often acts as a filtering stage for low-income households unable to qualify for home loans. This stage that is executed outside the policy chain symbolizes negative selectivism in the policy design that indirectly dissuades economically disadvantaged households’ access to the housing subsidy. Negative selectivism is a specific design favoring the targeting of welfare services based on individual means using some form of means-testing ( Thompson & Hoggett, 1996 ). In the case of CLSS, this means-testing is done by the private lenders guided by the market logic of selecting the households with the least risks. The initial qualifying criteria of becoming a homebuyer to access housing subsidy puts low-income households at a disadvantage as they face various accessibility and affordability constraints.

The analysis of this case study yields two key insights. First, politically strong target groups can actively represent their interests in policy design. In contrast, politically weak groups such as low-income households lack representation in policymaking. Consequently, there is a high likelihood that politically strong target groups advocate for their interpretations of affordable housing in policy design to suit their interests. Second, privatized implementation design embeds negative selectivism in the CLSS policy design. The underwriting performed by private lenders using the affordability criteria tends to select creditworthy households with secured income. This leads to the exclusion of informally employed low-income households unable to pass the affordability criteria, thereby preventing their participation in the housing subsidy scheme. This creates a subgroup within the target group of CLSS that gets structurally excluded from the scheme altogether.

This case study has several theoretical implications. First, it integrates a relational analytic lens with the SCTP framework to examine affordable housing policy goals within CLSS. This way, the study provides a useful example of going beyond the SCTP framework to understand the relational politics within the policy design. In doing so, the study expands the application of the SCTP framework to the Global South context, where it is hitherto underutilized. Second, given the shrinking of the welfare state across the globe, this inquiry brings back the critical question of “who benefits and who loses?” posed by Schneider and Sidney (2009 , p. 116) while questioning the normative aspects of the policy goal of affordable housing. This brings to light the discursive nature of policy goals as a concept prone to the power dynamics within the target groups. Lastly, although the SCTP framework proposes the dynamic nature of the target groups allowing them to move along different categories, there is limited attention given to differences in characterization within the target groups. This study shows the formation of an excluded group within the target group of low-income households emphasizing the heterogeneous characterization that needs the attention of the policymakers.

Considering that this case study represents one of the five schemes under the PMAY-U, there is a need to expand this inquiry to a broader level that includes all the schemes. This will generate a broader comparative picture and uncover the characteristics of the target groups that face systemic exclusion altogether. A deeper reflection by policymakers on these exclusionary tendencies in-built into the CLSS and PMAY-U design will be imperative to keep the welfarist social policy goals intact in the long term.

I thank all the study participants for sharing their experiences during the fieldwork. I am thankful to all the 2023 International Conference on Public Policy Design participants for their questions and discussion on this paper I presented at the conference. I am also grateful to Prof Michael Howlett and Dr Glyn Williams for sharing their insightful comments on the earlier version of the paper. Lastly, thanks to the anonymous reviewers and the journal editors for their constructive comments on the paper.

None declared.

In addition to the CLSS, other schemes are the following: “In-Situ” Slum Redevelopment uses the land as a resource to rehabilitate slum dwellers with financial assistance of ₹ 0.1 million (US$1,209) per housing unit; Affordable Housing in Partnership provides financial assistance of ₹ 0.15 million (US$1,813) per housing unit to affordable housing projects; Beneficiary-Led Construction offers a subsidy of ₹ 0.15 million (US$1,813) to households for the construction or enhancement of the house; and Affordable Rental Housing Complexes provides subsidized rental housing to urban migrants ( MoHUA, 2021 ).

The US$ conversion is provided based on the exchange rate data published by the Reserve Bank of India. 1 US$ equaled ₹ 82.7 on 14 February 2023.

The low-income household target group includes the EWS household with annual income up to ₹ 0.3 million (US$3,636) and the LIG household with annual income ranging from ₹ 0.3 to ₹ 0.6 million (US$7,273) ( MoHUA, 2021 ).

The MIG includes two categories: MIG-I (annual income between ₹ 0.6 million (US$7,273) and ₹ 1.2 million (US$14,510) and MIG-II (annual income between ₹ 1.2 and ₹ 1.8 million (US$21,765) ( MoHUA, 2021 ).

Bhate A. , & Samuel M. ( 2023 ). Affordable housing in India: A beneficiary perspective . Indian Journal of Public Administration , 69 ( 1 ), 188 – 203 . https://doi.org/10.1177/00195561221109065 .

Google Scholar

Camou M. ( 2005 ). Deservedness in poor neighborhoods: A morality struggle. In A. L. Schneider & H. M. Ingram (Eds.), Deserving and entitled: Social constructions of public policy (pp. 243 – 259 ). State University of New York Press .

Google Preview

Chanley S. A. , & Alozie N. O. ( 2001 ). Policy for the ‘deserving,’ but politically weak: The 1996 Welfare Reform Act and battered women . Review of Policy Research , 18 ( 2 ), 1 – 25 . https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-1338.2001.tb00183.x .

Drew R. B. ( 2013 ). Constructing homeownership policy: Social constructions and the design of the low-income homeownership policy objective . Housing Studies , 28 ( 4 ), 616 – 631 . https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2013.760030 .

Harish S. , & Raveendran S. ( 2023 ). In situ redevelopment of slums in Indian cities: Closing a rent gap? Housing Studies , 1 – 25 . https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2023.2180494 .

Hunter C. , & Nixon J. ( 1999 ). The discourse of housing debt: The social construction of landlords, lenders, borrowers and tenants . Housing, Theory and Society , 16 ( 4 ), 165 – 178 . https://doi.org/10.1080/14036099950149893 .

Hynes B. O. D. , & Hayes N. ( 2011 ). Who benefits from early childcare subsidy design in Ireland? Journal of Poverty and Social Justice , 19 ( 3 ), 277 – 288 . https://doi.org/10.1332/175982711X597017 .

IBEF . ( 2022 ) Indian real estate industry report . India Brand Equity Foundation . https://www.ibef.org/industry/real-estate-india .

Ingram H. , & Schneider A. L. ( 1991 ). The choice of target populations . Administration & Society , 23 ( 3 ), 333 – 356 . https://doi.org/10.1177/009539979102300304 .

Ingram H. Schneider A. L. , & DeLeon P. ( 2007 ). Social construction and policy design. In P. A. Sabatier (Ed.), Theories of the policy process (pp. 93 – 126 ). Westview Press .

Jacobs K. , & Manzi T. ( 1996 ). Discourse and policy change: The significance of language for housing research . Housing Studies , 11 ( 4 ), 543 – 560 . https://doi.org/10.1080/02673039608720874 .

Khaire M. , & Jha S. K. ( 2022a ). Evaluating the uneven outcome of Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana . Shelter , 23 ( 2 ), 64 – 70 .

Khaire M. , & Jha S. K. ( 2022b ). Examining homeownership bias in Indian housing policy using frame analysis . Environment and Urbanization ASIA , 13 ( 1 ), 113 – 125 . https://doi.org/10.1177/09754253221079527 .

Kumar A. , & Shukla S. K. ( 2022 ). Affordable housing and the urban poor in India . Social Change , 52 ( 1 ), 58 – 75 . https://doi.org/10.1177/00490857211040249 .

Kundu D. ( 2014 ). Urban development programmes in India: A critique of JNNURM . Social Change , 44 ( 4 ), 615 – 632 . https://doi.org/10.1177/0049085714548546 .

Kundu A. , & Kumar A. ( 2017 ). Housing for the urban poor? Changes in credit-linked subsidy . Economic and Political Weekly , 52 (52), 105 – 110 . https://www.jstor.org/stable/26699169 .

Lasswell H. D. ( 2018 ). Politics: Who gets what, when, how . Pickle Partners Publishing .

Lejano R. P. ( 2021 ). Relationality: An alternative framework for analyzing policy . Journal of Public Policy , 41 ( 2 ), 360 – 383 . https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X20000057 .

Mitra S. ( 2022 ). Policy-implementation dynamics of national housing programmes in India—Evidence from Madhya Pradesh . International Journal of Housing Policy , 22 ( 4 ), 500 – 521 . https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2021.1934649 .

MoHUA . ( 2005 ). Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission: Overview . Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs . https://mohua.gov.in/upload/uploadfiles/files/1Mission%20Overview%20English(1).pdf .

MoHUA . ( 2012 ). Task force report on promoting affordable housing . https://smartnet.niua.org/sites/default/files/resources/Draft%20Task%20Force%20Report%20on%20Promoting%20Affordable%20Housing.pdf .

MoHUA . ( 2016a ). Discontinuation of schemes, May 2015 . https://mohua.gov.in/upload/uploadfiles/files/1Ray_Discontinuation_19_05_2015.pdf .

MoHUA . ( 2016b ). Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana—Housing for All (Urban)—Scheme guidelines 2016 . https://pmay-urban.gov.in/uploads/guidelines/18HFA_guidelines_March2016-English.pdf .

MoHUA . ( 2021 ). Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana—Housing for All (Urban)—Scheme guidelines 2021 . https://pmay-urban.gov.in/uploads/guidelines/62381c744c188-Updated-guidelines-of-PMAY-U.pdf .

MoHUA . ( 2022 ). PMAY-U achievement, 2022 .

MoHUA . ( 2023 ). CLSS awas portal, 2023 . https://pmayuclap.gov.in/content/html/CLSS_Vertical.html .

Nallathiga R. ( 2007 ). Housing policy in India: Challenges and reform . Review of Development and Change , 12 ( 1 ), 71 – 98 . https://doi.org/10.1177/0972266120070103 .

Pierce J. J. , Siddiki S. , Jones M. D. , Schumacher K. , Pattison A. , & Peterson H. ( 2014 ). Social construction and policy design: A review of past applications . Policy Studies Journal , 42 ( 1 ), 1 – 29 . https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12040 .

Sabatier P. A. ( 1986 ). Top-down and bottom-up approaches to implementation research: A critical analysis and suggested synthesis . Journal of Public Policy , 6 ( 1 ), 21 – 48 . https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X00003846 .

Saiz A. ( 2023 ). The global housing affordability crisis: Policy options and strategies ( MIT Center for Real Estate Research Paper No. 23/01).

Schneider A. , & Ingram H. ( 1993 ). Social construction of target populations: Implications for politics and policy . American Political Science Review , 87 ( 2 ), 334 – 347 . https://doi.org/10.2307/2939044 .

Schneider A. L. , & Ingram H. M. ( 1997 ). Policy design for democracy . University Press of Kansas .

Schneider A. , & Sidney M. ( 2009 ). What is next for policy design and social construction theory? Policy Studies Journal , 37 ( 1 ), 103 – 119 . https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2008.00298.x .

Sivam A. , & Karuppannan S. ( 2002 ). Role of state and markets in housing delivery for low-income groups in India . Journal of Housing and the Built Environment , 17 ( 1 ), 69 – 88 . https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014831817503 .

Smets P. ( 1997 ). Private housing finance in India: Reaching down-market? Habitat International , 21 ( 1 ), 1 – 15 . https://doi.org/10.1016/S0197-3975(96)00036-7 .

Thompson S. , & Hoggett P. ( 1996 ). Universalism, selectivism and particularism: Towards a postmodern social policy . Critical Social Policy , 16 ( 46 ), 21 – 42 . https://doi.org/10.1177/026101839601604602 .

Tiwari P. , & Rao J. ( 2016 ). Housing markets and housing policies in India. In N. Yoshino & M. Helble (Eds.), The housing challenge in emerging Asia: Options and solutions (pp. 262–302). Asian Development Bank Institute .

Trochmann M. ( 2021 ). Identities, intersectionality, and otherness: The social constructions of deservedness in American housing policy . Administrative Theory & Praxis , 43 ( 1 ), 97 – 116 . https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.2019.1700456 .

Wetzstein S. ( 2017 ). The global urban housing affordability crisis . Urban Studies , 54 ( 14 ), 3159 – 3177 . https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017711649 .

Yoshino N. , & Helble M. ( 2016 ). The housing challenge in emerging Asia: Options and solutions . Asian Development Bank Institute .

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1839-3373

- Print ISSN 1449-4035

- Copyright © 2024 Darryl S. Jarvis and M. Ramesh

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

AFFORDABLE HOUSING – REALITY CHALLENGE A CASE STUDY IN BANGALORE CITY

The city of Bangalore witnessed several changes in the trading of goods and services from pre-independence period. The city has transformed from selling local produce to setting up the nucleus of the Information Technology industry in the country. This phenomenal growth is also witnessed in the expansion of the geographic boundaries of the city. The city’s developmental fate has changed hands through several bureaucratic powers. The government has segregated the powers based on smaller geographical areas or wards, functional development required and many other criteria. This led many developmental projects to be initiated in isolation, lack of funds and resources and coordination which has largely affected the common man’s day-to-day life.

Related Papers

joydeep neogi

With about one in six urban Indians living in informal squatter settlements, the need for an additional number of affordable housing in India is growing exponentially. The Indian department of “Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation” (MoHUPA) launched its ambitious “Housing for All” scheme under Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana(PMAY) in September 2015 with the goal to make India slum-free by 2022. This scheme is based on similar former programs and shows promise regarding the number of houses that will be built with the help of the government’s credit-linked subsidies for all incomegroups in India. However, the program has many shortcomings, especially from a people-centered perspective: beneficiaries are often perceived as passive, there are few empowerment measures in the scheme, access to benefits is exclusive, and long term effects are neglected. It is concluded that PMAY 2014 is mainly an image campaign for the government and lacks sustainable elements. Even there are many issues like a private partnership and investment which are neglected in a broader perspective. This dissertation intends to suggest possible backdrop from this Housing for All scheme and suggest reforms on policy and also to increase private partnership investment in the scheme. The focus lies on potentials found in decentralized municipal policies, public-private partnerships for upgrading existing housing, as well as provide the housing shortage and providing basic facilities, and on beneficiary’s empowerment. These elements are discussed based on an inclusive and people-centered approach to development to speed up the scheme. The results of this discussion, analysis, and inference will then be abstracted into tentative suggestive guidelines on how to approach affordable housing in a developing country with private partnership and investments.

Dr. Kalpana Gopalan IAS

Affordable Housing is fast taking centre stage in the national agenda. In India, affordable housing is a term largely used in the urban context. This is more a matter of administrative logistics: at the national level, the rural housing sector falls within the purview of the Ministry of Rural Development, while the “Housing and Human Settlements” in urban areas is the jurisdiction of The Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation. It is the latter ministry that has spearheaded affordable housing as a concept and policy.Developing affordable housing on a large scale is the greatest challenge in urban India today, promising a solution to the proliferation of slums, unorganized real estate development, unplanned growth and transit congestion. It is vital that certain critical issues are addressed urgently to make affordable housing a possibility. Affordable housing is a larger concept than low cost housing, it includes within its ambit low and middle income group housing with a larger basic amenities like schools and hospitals. From the above, it is clear that a one size fits all approach cannot and will not work in the affordable housing sector.

Urmi Sengupta

This is a paper prepared by me for the Indian Institute of Management Bangalore-CRERI Real Estate Research Initiative. The paper is intended as a overview of the affordable housing sector with special emphasis on India. Affordable Housing is fast taking centrestage in the national agenda. In India, affordable housing is a term largely used in the urban context.Affordable housing refers to any housing that meets some form of affordability criterion, which could be income level of the family, size of the dwelling unit or affordability in terms of EMI size or ratio of house price to annual income. The demand drivers for affordable housing are several.Alongside the growth of the urban population, rising incomes have led to the expansion of the middle class. This has led to a spike in demand for housing that is affordable but includes basic amenities. The agencies working in the affordable housing sector can be classified into . the public sector and the private sector. Both are dogged by issues such as scarcity of land,scarcity of marketable land parcels,titling Issues, rising costs and regulatory concerns. The way forward calls for a collaborative multi-pronged multi-stakehoder approach.

Kanha Godha

Institute of Town Planners, India Journal

Joy Karmakar

Government of India’s mission of affordable housing for all the citizens by 2022 has become a major talking point for the people including policy makers to private developers to scholars at different levels. The idea of affordability and affordable housing has been defined by various organizations over the years but no unanimous definition has emerged. The need for affordable housing in the urban area is not new to India and especially mega cities like Kolkata. The paper makes an attempt to revisit and assess the affordable housing provision in Kolkata Metropolitan Area and how the idea of affordable housing provision has evolved over the years. It became clear from the analysis that role of the state in providing affordable housing to urban poor has not only been reduced but shifted to the middle class.

Issac Arul Selva

The report reviews various housing related policies and schemes at national and state level and their implementation in Karnataka during last one decade (2007-17). The evaluations are based on surveys and in-depth interviews with the communities in 6 districts and their experience of accessing housing through these schemes. All major models of housing provision have been analyzed and recommendation from the perspective of urban deprived communities has been provided.

International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Growth Evaluation

C.E Dr Sumanta Bhattacharya M.Tech,PhD,P.E,Ch.E

12 to 13% of the GDP is spent on housing which incorporate gross rent, utilizes and owners imputed rent. Housing is important for all, India is a developing economy, housing price and affordable varies from city to city and also depending upon the population of the state, for better income and education facilitates people shift to the metropolitan cities or smart cities. Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai, Surat, Bangalore are facing a rise in population, where people are facing housing problems, in India people either have their own homes or they live in rented house, 65,000 million population live in the slums area in rural India due to heavy storm or cyclone the kaccha houses flow away. 1 % of the village have paccha houses which is part of smart villages. The government has launched many schemes for providing housing loans and construction of loans, however with the growing population, we require more space for housing, the smart city mission is one of the ways to provide housing for all. W...

Devendra B Gupta

Evidence indicates that the situation of urban housing in India has been poor over the past thirty years and may have even deteriorated in many important aspects over this period. This paper documents and brings together a range of scattered information not hitherto accessible to shed light on this neglected area of economic policy in India. It evaluates the existing housing stock in the country and the role of housing in the national economy. It analyses the components of increasing housing demand and identifies the series of constraints that impair the expansion of supply. It concludes that there is a clear need for a major overhaul of many of the government policies and regulations such that housing supply may be more responsive to demand from all income levels.

Lalitha Kamath

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

IMAGES

COMMENTS

series of reports and case studies that together have described awardees' objectives, strategies, methods, and accomplishments. This document, which is the last of these publications, focuses on five remarkable programs that could serve as models for nonprofit affordable housing organizations to replicate. The programs and the collaborations that

a case study - affordable housing. G.VINAY KUMAR 1 , DR.ARCHANAA DO NGRE 2 , GANTA SRINIVAS 3 . ASST.PROFESSOR, CIVIL ENGG, VIDYA JYOTHI INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY 1

Affordable Infill Housing: U S. DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT THE SECRETARY WASHINGTON, D.C. 20410-0001 Five Case Studies HUD in 1981, making affordable housing available to more Americans was high on my list of priorities. When I came to As part of the effort to do so, I created the Joint Venture for Affordable Housing in January ...