Guide to Scholarly Articles

Getting started, what makes an article scholarly, why does this matter.

- Scholarly vs. Popular vs. Trade Articles

- Types of Scholarly Articles

- Anatomy of Scholarly Articles

- Tips for Reading Scholarly Articles

Scholarship is a conversation.

That conversation is often found in the form of published materials such as books, essays, and articles. Here, we will focus on scholarly articles because scholarly articles often contain the most current scholarly conversation.

After reading through this guide on scholarly articles you will be able to identify and describe different types of scholarly articles. This will allow you to navigate the scholarly conversation more effectively which in turn will make your research more productive.

The distinguishing feature of a scholarly article is not that it is without errors; rather, a scholarly article is distinguished by a few characteristics which reduce the likelihood of errors. For our purposes, those characteristics are expert authors , peer-review , and citations .

- Expert Authors - Authority is constructed and contextual. In other words it is built through academic credentialing and lived experience. Scholarly articles are written by experts in their respective fields rather than generalists. Expertise often comes in the form of academic credentials. For example, an article about the spread of various diseases should be written by someone with credentials and experience in immunology or public health.

- Peer-review - Peer-review is the process whereby scholarly articles are vetted and improved. In this process an author submits an article to a journal for publication. However, before publication, an editor of the journal will send the article to other experts in the field to solicit their informed and professional opinions of it. These reviewers (sometimes called referees) will give the editor feedback regarding the quality of the article. Based on this process, articles may be published as is, published after specific changes are made, or not published at all.

- Citations - One of the key differences between scholarly articles and other kinds of articles is that the former contain citations and bibliographies. These citations allow the reader to follow up on the author's sources to verify or dispute the author's claim.

There is a well-known axiom that says "Garbage in, garbage out." In the context of research this means that the quality of your research output is dependent on the information sources that go into you own research. Generally speaking, the information found in scholarly articles is more reliable than information found elsewhere. It is important to identify scholarly articles and prioritize them in your own research.

- Next: Scholarly vs. Popular vs. Trade Articles >>

- Last Updated: Aug 23, 2023 8:53 AM

- URL: https://researchguides.library.tufts.edu/scholarly-articles

Finding Scholarly Articles: Home

What's a Scholarly Article?

Your professor has specified that you are to use scholarly (or primary research or peer-reviewed or refereed or academic) articles only in your paper. What does that mean?

Scholarly or primary research articles are peer-reviewed , which means that they have gone through the process of being read by reviewers or referees before being accepted for publication. When a scholar submits an article to a scholarly journal, the manuscript is sent to experts in that field to read and decide if the research is valid and the article should be published. Typically the reviewers indicate to the journal editors whether they think the article should be accepted, sent back for revisions, or rejected.

To decide whether an article is a primary research article, look for the following:

- The author’s (or authors') credentials and academic affiliation(s) should be given;

- There should be an abstract summarizing the research;

- The methods and materials used should be given, often in a separate section;

- There are citations within the text or footnotes referencing sources used;

- Results of the research are given;

- There should be discussion and conclusion ;

- With a bibliography or list of references at the end.

Caution: even though a journal may be peer-reviewed, not all the items in it will be. For instance, there might be editorials, book reviews, news reports, etc. Check for the parts of the article to be sure.

You can limit your search results to primary research, peer-reviewed or refereed articles in many databases. To search for scholarly articles in HOLLIS , type your keywords in the box at the top, and select Catalog&Articles from the choices that appear next. On the search results screen, look for the Show Only section on the right and click on Peer-reviewed articles . (Make sure to login in with your HarvardKey to get full-text of the articles that Harvard has purchased.)

Many of the databases that Harvard offers have similar features to limit to peer-reviewed or scholarly articles. For example in Academic Search Premier , click on the box for Scholarly (Peer Reviewed) Journals on the search screen.

Review articles are another great way to find scholarly primary research articles. Review articles are not considered "primary research", but they pull together primary research articles on a topic, summarize and analyze them. In Google Scholar , click on Review Articles at the left of the search results screen. Ask your professor whether review articles can be cited for an assignment.

A note about Google searching. A regular Google search turns up a broad variety of results, which can include scholarly articles but Google results also contain commercial and popular sources which may be misleading, outdated, etc. Use Google Scholar through the Harvard Library instead.

About Wikipedia . W ikipedia is not considered scholarly, and should not be cited, but it frequently includes references to scholarly articles. Before using those references for an assignment, double check by finding them in Hollis or a more specific subject database .

Still not sure about a source? Consult the course syllabus for guidance, contact your professor or teaching fellow, or use the Ask A Librarian service.

- Last Updated: Oct 3, 2023 3:37 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/FindingScholarlyArticles

Harvard University Digital Accessibility Policy

How to Find, Evaluate, and Cite Scholarly Articles: Getting Started

- Getting Started

- Finding Articles

- Evaluating Articles

- Citing Articles

Header Image

This guide features information and resources on scholarly articles. You'll find material on how to:

- find articles

- evaluate the credibility of articles

- read and annotate articles

- cite articles

What is a Scholarly Article?

Scholarly articles , also known as journal articles , are essay-length publications that make arguments, present research, and draw conclusions about an idea, problem, or text . You may read scholarly articles for a class assignment or while conducting your own original research.

How to Read a Scholarly Article This article breaks down the components of scholarly articles and features tips for reading them.

- Next: Finding Articles >>

- Last Updated: Sep 30, 2022 5:14 AM

- URL: https://paperpile.libguides.com/scholarly-articles

Evaluating Information Sources

- Evaluate Your Sources

- Publication Types and Bias

Structure of Scientific Papers

Reading a scholarly article, additional reading tips, for more information.

- Reading Scholarly Articles

- Impact Factors and Citation Counts

- Predatory Publishing

Research papers generally follow a specific format. Here are the different parts of the scholarly article.

Abstract (Summary)

The abstract, generally written by the author(s) of the article, provides a concise summary of the whole article. Usually it highlights the focus, study results and conclusion(s) of the article.

Introduction (Why)

In this section, the authors introduce their topic, explain the purpose of the study, and present why it is important, unique or how it adds to existing knowledge in their field. Look for the author's hypothesis or thesis here.

Introduction - Literature Review (Who else)

Many scholarly articles include a summary of previous research or discussions published on this topic, called a "Literature Review". This section outlines what others have found and what questions still remain.

Methodology / Materials and Methods (How)

Find the details of how the study was performed in this section. There should be enough specifics so that you could repeat the study if you wanted.

Results (What happened)

This section includes the findings from the study. Look for the data and statistical results in the form of tables, charts, and graphs. Some papers include an analysis here.

Discussion / Analysis (What it means)

This section should tell you what the authors felt was significant about their results. The authors analyze their data and describe what they believe it means.

Conclusion (What was learned)

Here the authors offer their final thoughts and conclusions and may include: how the study addressed their hypothesis, how it contributes to the field, the strengths and weaknesses of the study, and recommendations for future research. Some papers combine the discussion and conclusion.

A scholarly paper can be difficult to read. Instead of reading straight through, try focusing on the different sections and asking specific questions at each point.

What is your research question?

When you select an article to read for a project or class, focus on your topic. Look for information in the article that is relevant to your research question.

Read the abstract first as it covers basics of the article. Questions to consider:

- What is this article about? What is the working hypothesis or thesis?

- Is this related to my question or area of research?

Second: Read the introduction and discussion/conclusion. These sections offer the main argument and hypothesis of the article. Questions to consider for the introduction:

- What do we already know about this topic and what is left to discover?

- What have other people done in regards to this topic?

- How is this research unique?

- Will this tell me anything new related to my research question?

Questions for the discussion and conclusion:

- What does the study mean and why is it important?

- What are the weaknesses in their argument?

- Is the conclusion valid?

Next: Read about the Methods/Methodology. If what you've read addresses your research question, this should be your next section. Questions to consider:

- How did the author do the research? Is it a qualitative or quantitative project?

- What data are the study based on?

- Could I repeat their work? Is all the information present in order to repeat it?

Finally: Read the Results and Analysis. Now read the details of this research. What did the researchers learn? If graphs and statistics are confusing, focus on the explanations around them. Questions to consider:

- What did the author find and how did they find it?

- Are the results presented in a factual and unbiased way?

- Does their analysis agree with the data presented?

- Is all the data present?

- What conclusions do you formulate from this data? (And does it match with the Author's conclusions?)

Review the References (anytime): These give credit to other scientists and researchers and show you the basis the authors used to develop their research. The list of references, or works cited, should include all of the materials the authors used in the article. The references list can be a good way to identify additional sources of information on the topic. Questions to ask:

- What other articles should I read?

- What other authors are respected in this field?

- What other research should I explore?

When you read these scholarly articles, remember that you will be writing based on what you read.

While you are Reading:

- Keep in mind your research question

- Focus on the information in the article relevant to your question (feel free to skim over other parts)

- Question everything you read - not everything is 100% true or performed effectively

- Think critically about what you read and seek to build your own arguments

- Read out of order! This isn't a mystery novel or movie, you want to start with the spoiler

- Use any keywords printed by the journals as further clues about the article

- Look up words you don't know

How to Take Notes on the Article

Try different ways, but use the one that fits you best. Below are some suggestions:

- Print the article and highlight, circle and otherwise mark while you read (for a PDF, you can use the highlight text feature in Adobe Reader)

- Take notes on the sections, for example in the margins (Adobe Reader offers pop-up sticky notes )

- Highlight only very important quotes or terms - or highlight potential quotes in a different color

- Summarize the main or key points

Reflect on what you have read - draw your own conclusions . As you read jot down questions that come to mind. These may be answered later on in the article or you may have found something that the authors did not consider. Here are a few questions that might be helpful:

- Have I taken time to understand all the terminology?

- Am I spending too much time on the less important parts of this article?

- Do I have any reason to question the credibility of this research?

- What specific problem does the research address and why is it important?

- How do these results relate to my research interests or to other works which I have read?

- Anatomy of a Scholarly Article (Interactive tutorial) Andreas Orphanides, North Carolina State University Libraries, 2009

- How to Read an Article in a Scholarly Journal (Research Guide) Cayuga Community College Library, 2016

- How To Read a Scholarly Journal Article (YouTube Video) Tim Lockman, Kishwaukee College Library, 2012.

- How To Read a Scientific Paper (Interactive tutorial) Michael Fosmire, Purdue University Libraries, 2013. PDF

- How to Read a Scientific Paper (Online article) Science Buddies, 2012

- How to Read a Scientific Research Paper (Article) Durbin Jr., C. G. Respiratory Care, 2009

- The Illusion of Certainty and the Certainty of Illusion: A Caution when Reading Scientific Articles (Article) T. A. Lang, International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 2011,

- Infographic: How to Read Scientific Papers Natalia Rodriguez, Elsevier, 2015

- Library Research Methods: Read & Evaluate Culinary Institute of America Library, 2016

- << Previous: Publication Types and Bias

- Next: Impact Factors and Citation Counts >>

- Last Updated: Mar 8, 2024 1:17 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/evaluate

What is a Scholarly Article: What is a scholarly article

Determineif a source is scholarly, determine if a source is scholarly, what is a scholarly source.

Scholarly sources (also referred to as academic, peer-reviewed, or refereed sources) are written by experts in a particular field and serve to keep others interested in that field up to date on the most recent research, findings, and news. These resources will provide the most substantial information for your research and papers.

What is peer-review?

When a source has been peer-reviewed, it has undergone the review and scrutiny of a review board of colleagues in the author’s field. They evaluate this source as part of the body of research for a particular discipline and make recommendations regarding its publication in a journal, revisions prior to publication, or, in some cases, reject its publication.

Why use scholarly sources?

Scholarly sources’ authority and credibility improve the quality of your own paper or research project.

How can I tell if a source is scholarly?

The following characteristics can help you differentiate scholarly sources from those that are not. Be sure to look at the criteria in each category when making your determination, rather than basing your decision on only one piece of information.

- Are author names provided?

- Are the authors’ credentials provided?

- Are the credentials relevant to the information provided?

- Who is the publisher of the information?

- Is the publisher an academic institution, scholarly, or professional organization?

- Is their purpose for publishing this information evident?

- Who is the intended audience of this source?

- Is the language geared toward those with knowledge of a specific discipline rather than the general public?

- Why is the information being provided?

- Are sources cited?

- Are there charts, graphs, tables, and bibliographies included?

- Are research claims documented?

- Are conclusions based on evidence provided?

- How long is the source?

Currency/Timeliness

- Is the date of publication evident?

Additional Tips for Specific Scholarly Source Types

Each resource type below will also have unique criteria that can be applied to it to determine if it is scholarly.

- Books published by a University Press are likely to be scholarly.

- Professional organizations and the U.S. Government Printing Office can also be indicators that a book is scholarly.

- Book reviews can provide clues as to if a source is scholarly and highlight the intended audience. See our Find Reviews guide to locate reviews on titles of interest.

- Are the author’s professional affiliations provided?

- Who is the publisher?

- How frequently is the periodical published?

- How many and what kinds of advertisements are present? For example, is the advertising clearly geared towards readers in a specific discipline or occupation?

- For more information about different periodical types, see our Selecting Sources guide.

- What is the domain of the page (for example: .gov, .edu, etc.)?

- Who is publishing or sponsoring the page?

- Is contact information for the author/publisher provided?

- How recently was the page updated?

- Is the information biased? Scholarly materials published online should not have any evidence of bias.

Is My Source Scholarly? (Accessible View)

Step 1: Source

The article is most likely scholarly if:

- You found the article in a library database or Google Scholar

- The journal the article appears in is peer-reviewed

Move to Step 2: Authors

Step 2: Authors

The source is most likely scholarly if:

- The authors’ credentials are provided

- The authors are affiliated with a university or other research institute

Move to Step 3: Content

Step 3: Content

- The source is longer than 10 pages

- Has a works cited or bibliography

- It does not attempt to persuade or bias the reader

- It attempts to persuade or bias the reader, but treats the topic objectively, the information is well-supported, and it includes a works cited or bibliography

If the article meets the criteria in Steps 1-3 it is most likely scholarly.

Common Characteristics of a Scholarly Article

Common characteristics of scholarly (research) articles.

Articles in scholarly journals may also be called research journals, peer reviewed journals, or refereed journals. These types of articles share many common features, including:

- articles always provide the name of the author or multiple authors

- author(s) always have academic credentials (e.g. biologist, chemist, anthropologist, lawyer)

- articles often have a sober, serious look

- articles may contain many graphs and charts; few glossy pages or color pictures

- author(s) write in the language of the discipline (e.g. biology, chemistry, anthropology, law, etc.)

- authors write for other scholars, and emerging scholars

- authors always cite their sources in footnotes, bibliographies, notes, etc.

- often (but not always) associated with universities or professional organizations

Types of Scholarly Articles

Peer Review in 3 Minutes

North Carolina State University (NCSU) Libraries (3:15)

- What do peer reviewers do? How are they similar to or different from editors?

- Who are the primary customers of scholarly journals?

- Do databases only include peer-reviewed articles? How do you know?

Is my source scholarly

Is My Source Scholarly?: INFOGRAPHIC

This infographic is part of the Illinois Library's Determine if a source is scholarly.

"Is my source scholarly" by Illinois Library https://www.library.illinois.edu/ugl/howdoi/scholarly/

Anatomy of a Scholarly Article: Interactive Tutorial

Typical Sections of a Peer-Reviewed Research Article

Typical sections of peer-reviewed research articles.

Research articles in many disciplines are organized into standard sections. Although these sections may vary by discipline, common sections include:

- Introduction

- Materials and Methods

It's not hard to spot these sections; just look for bold headings in the article, as shown in these illustrations:

- Last Updated: Oct 22, 2020 11:31 AM

- URL: https://libguides.mccd.edu/WhatisaScholarlyArticle

Scholarly Articles

Scholarly articles defined, how to find scholarly articles, how do i tell if an article is scholarly, reading and using scholarly articles.

Scholarly articles (also known as academic or peer-reviewed articles) are written by experts for experts (and for college students!). Scholarly articles usually contain cited references and are often written in specialized, technical language. They are in-depth explorations of focused topics, and because they’ve been through an intensive review process before publication, they are highly trustworthy sources.

Learn more at What Is a Refereed/Peer-Reviewed Article .

Almost every library database has a way to limit your keyword search so that you retrieve only scholarly articles. Look for checkboxes marked “scholarly” or “academic” or “peer-reviewed”:

With practice, you can tell at a glance if an article is scholarly. Look for these characteristics of a scholarly article:

- Even the title of a scholarly article may sound complicated—much more complicated than a news headline, for example

- In-text citations throughout the article and a list of references at the end

- The library database will usually show where the authors of an article work.

- Scholarly articles are often written by people at research institutions, like a university or think tank or laboratory.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Methods

- Results

- Discussion

- Literature Cited

- For more info on the structure and characteristics of a scholarly article, see Anatomy of a Scholarly Article

- Many library databases will indicate whether an article (or the journal it appeared in) is scholarly. And remember, “peer reviewed” and “academic” mean the same thing as “scholarly”:

Distinguishing among Scholarly, Popular, and Trade Journals offers more help understanding the differences between scholarly, popular, and trade journals.

Because they usually are written by experts, in specialized/technical language, scholarly articles can be hard to read! But if you review one carefully, even if you don’t understand every detail, you should be able to extract from the article one or two main ideas or facts that you can incorporate into your research project.

In a scientific scholarly article, there may be terms you don’t understand—Google them! Also, a scientific article may contain complicated numerical/statistical data that’s hard for non-experts to understand. But again, you don’t have to understand every detail of the article to be able to use it!

Try reviewing the Introduction section and Discussion section of a scientific article. That’s where the authors lay out the purpose of their research and the importance of what they discovered—you can often extract main ideas and interesting facts from those sections.

- Last Updated: Jan 16, 2024 5:53 PM

- URL: https://libguides.umgc.edu/articles

Reference management. Clean and simple.

Google Scholar: the ultimate guide

What is Google Scholar?

Why is google scholar better than google for finding research papers, the google scholar search results page, the first two lines: core bibliographic information, quick full text-access options, "cited by" count and other useful links, tips for searching google scholar, 1. google scholar searches are not case sensitive, 2. use keywords instead of full sentences, 3. use quotes to search for an exact match, 3. add the year to the search phrase to get articles published in a particular year, 4. use the side bar controls to adjust your search result, 5. use boolean operator to better control your searches, google scholar advanced search interface, customizing search preferences and options, using the "my library" feature in google scholar, the scope and limitations of google scholar, alternatives to google scholar, country-specific google scholar sites, frequently asked questions about google scholar, related articles.

Google Scholar (GS) is a free academic search engine that can be thought of as the academic version of Google. Rather than searching all of the indexed information on the web, it searches repositories of:

- universities

- scholarly websites

This is generally a smaller subset of the pool that Google searches. It's all done automatically, but most of the search results tend to be reliable scholarly sources.

However, Google is typically less careful about what it includes in search results than more curated, subscription-based academic databases like Scopus and Web of Science . As a result, it is important to take some time to assess the credibility of the resources linked through Google Scholar.

➡️ Take a look at our guide on the best academic databases .

One advantage of using Google Scholar is that the interface is comforting and familiar to anyone who uses Google. This lowers the learning curve of finding scholarly information .

There are a number of useful differences from a regular Google search. Google Scholar allows you to:

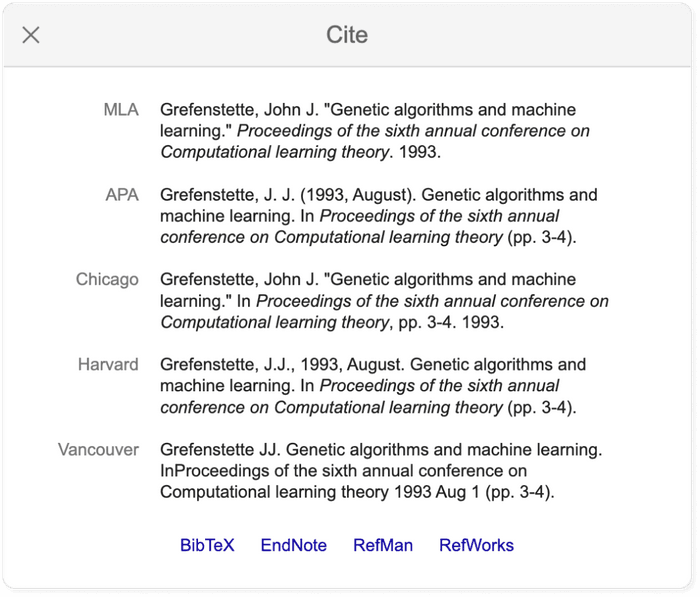

- copy a formatted citation in different styles including MLA and APA

- export bibliographic data (BibTeX, RIS) to use with reference management software

- explore other works have cited the listed work

- easily find full text versions of the article

Although it is free to search in Google Scholar, most of the content is not freely available. Google does its best to find copies of restricted articles in public repositories. If you are at an academic or research institution, you can also set up a library connection that allows you to see items that are available through your institution.

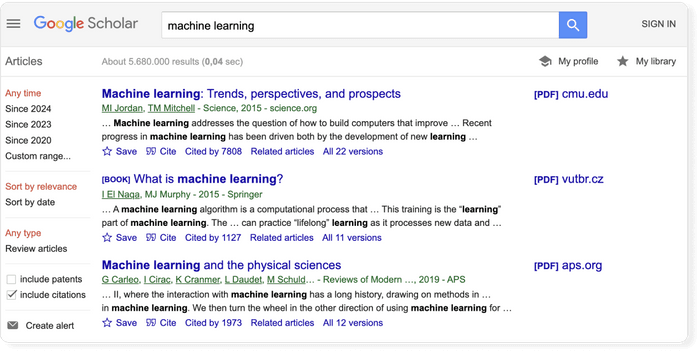

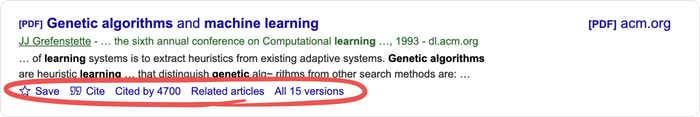

The Google Scholar results page differs from the Google results page in a few key ways. The search result page is, however, different and it is worth being familiar with the different pieces of information that are shown. Let's have a look at the results for the search term "machine learning.”

- The first line of each result provides the title of the document (e.g. of an article, book, chapter, or report).

- The second line provides the bibliographic information about the document, in order: the author(s), the journal or book it appears in, the year of publication, and the publisher.

Clicking on the title link will bring you to the publisher’s page where you may be able to access more information about the document. This includes the abstract and options to download the PDF.

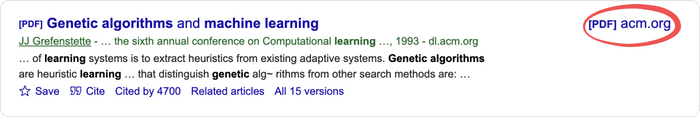

To the far right of the entry are more direct options for obtaining the full text of the document. In this example, Google has also located a publicly available PDF of the document hosted at umich.edu . Note, that it's not guaranteed that it is the version of the article that was finally published in the journal.

Below the text snippet/abstract you can find a number of useful links.

- Cited by : the cited by link will show other articles that have cited this resource. That is a super useful feature that can help you in many ways. First, it is a good way to track the more recent research that has referenced this article, and second the fact that other researches cited this document lends greater credibility to it. But be aware that there is a lag in publication type. Therefore, an article published in 2017 will not have an extensive number of cited by results. It takes a minimum of 6 months for most articles to get published, so even if an article was using the source, the more recent article has not been published yet.

- Versions : this link will display other versions of the article or other databases where the article may be found, some of which may offer free access to the article.

- Quotation mark icon : this will display a popup with commonly used citation formats such as MLA, APA, Chicago, Harvard, and Vancouver that may be copied and pasted. Note, however, that the Google Scholar citation data is sometimes incomplete and so it is often a good idea to check this data at the source. The "cite" popup also includes links for exporting the citation data as BibTeX or RIS files that any major reference manager can import.

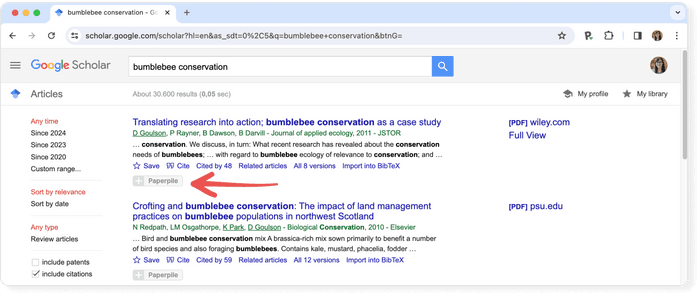

Pro tip: Use a reference manager like Paperpile to keep track of all your sources. Paperpile integrates with Google Scholar and many popular academic research engines and databases, so you can save references and PDFs directly to your library using the Paperpile buttons and later cite them in thousands of citation styles:

Although Google Scholar limits each search to a maximum of 1,000 results , it's still too much to explore, and you need an effective way of locating the relevant articles. Here’s a list of pro tips that will help you save time and search more effectively.

You don’t need to worry about case sensitivity when you’re using Google scholar. In other words, a search for "Machine Learning" will produce the same results as a search for "machine learning.”

Let's say your research topic is about self driving cars. For a regular Google search we might enter something like " what is the current state of the technology used for self driving cars ". In Google Scholar, you will see less than ideal results for this query .

The trick is to build a list of keywords and perform searches for them like self-driving cars, autonomous vehicles, or driverless cars. Google Scholar will assist you on that: if you start typing in the search field you will see related queries suggested by Scholar!

If you put your search phrase into quotes you can search for exact matches of that phrase in the title and the body text of the document. Without quotes, Google Scholar will treat each word separately.

This means that if you search national parks , the words will not necessarily appear together. Grouped words and exact phrases should be enclosed in quotation marks.

A search using “self-driving cars 2015,” for example, will return articles or books published in 2015.

Using the options in the left hand panel you can further restrict the search results by limiting the years covered by the search, the inclusion or exclude of patents, and you can sort the results by relevance or by date.

Searches are not case sensitive, however, there are a number of Boolean operators you can use to control the search and these must be capitalized.

- AND requires both of the words or phrases on either side to be somewhere in the record.

- NOT can be placed in front of a word or phrases to exclude results which include them.

- OR will give equal weight to results which match just one of the words or phrases on either side.

➡️ Read more about how to efficiently search online databases for academic research .

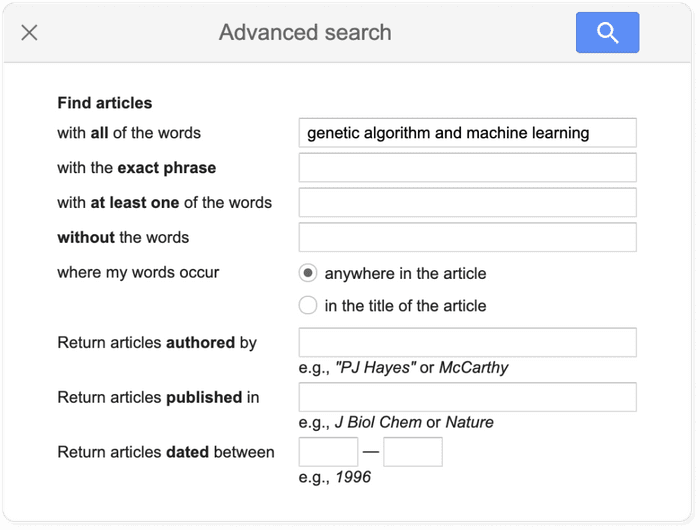

In case you got overwhelmed by the above options, here’s some illustrative examples:

Tip: Use the advanced search features in Google Scholar to narrow down your search results.

You can gain even more fine-grained control over your search by using the advanced search feature. This feature is available by clicking on the hamburger menu in the upper left and selecting the "Advanced search" menu item.

Adjusting the Google Scholar settings is not necessary for getting good results, but offers some additional customization, including the ability to enable the above-mentioned library integrations.

The settings menu is found in the hamburger menu located in the top left of the Google Scholar page. The settings are divided into five sections:

- Collections to search: by default Google scholar searches articles and includes patents, but this default can be changed if you are not interested in patents or if you wish to search case law instead.

- Bibliographic manager: you can export relevant citation data via the “Bibliography manager” subsection.

- Languages: if you wish for results to return only articles written in a specific subset of languages, you can define that here.

- Library links: as noted, Google Scholar allows you to get the Full Text of articles through your institution’s subscriptions, where available. Search for, and add, your institution here to have the relevant link included in your search results.

- Button: the Scholar Button is a Chrome extension which adds a dropdown search box to your toolbar. This allows you to search Google Scholar from any website. Moreover, if you have any text selected on the page and then click the button it will display results from a search on those words when clicked.

When signed in, Google Scholar adds some simple tools for keeping track of and organizing the articles you find. These can be useful if you are not using a full academic reference manager.

All the search results include a “save” button at the end of the bottom row of links, clicking this will add it to your "My Library".

To help you provide some structure, you can create and apply labels to the items in your library. Appended labels will appear at the end of the article titles. For example, the following article has been assigned a “RNA” label:

Within your Google Scholar library, you can also edit the metadata associated with titles. This will often be necessary as Google Scholar citation data is often faulty.

There is no official statement about how big the Scholar search index is, but unofficial estimates are in the range of about 160 million , and it is supposed to continue to grow by several million each year.

Yet, Google Scholar does not return all resources that you may get in search at you local library catalog. For example, a library database could return podcasts, videos, articles, statistics, or special collections. For now, Google Scholar has only the following publication types:

- Journal articles : articles published in journals. It's a mixture of articles from peer reviewed journals, predatory journals and pre-print archives.

- Books : links to the Google limited version of the text, when possible.

- Book chapters : chapters within a book, sometimes they are also electronically available.

- Book reviews : reviews of books, but it is not always apparent that it is a review from the search result.

- Conference proceedings : papers written as part of a conference, typically used as part of presentation at the conference.

- Court opinions .

- Patents : Google Scholar only searches patents if the option is selected in the search settings described above.

The information in Google Scholar is not cataloged by professionals. The quality of the metadata will depend heavily on the source that Google Scholar is pulling the information from. This is a much different process to how information is collected and indexed in scholarly databases such as Scopus or Web of Science .

➡️ Visit our list of the best academic databases .

Google Scholar is by far the most frequently used academic search engine , but it is not the only one. Other academic search engines include:

- Science.gov

- Semantic Scholar

- scholar.google.fr : Sur les épaules d'un géant

- scholar.google.es (Google Académico): A hombros de gigantes

- scholar.google.pt (Google Académico): Sobre os ombros de gigantes

- scholar.google.de : Auf den Schultern von Riesen

➡️ Once you’ve found some research, it’s time to read it. Take a look at our guide on how to read a scientific paper .

No. Google Scholar is a bibliographic search engine rather than a bibliographic database. In order to qualify as a database Google Scholar would need to have stable identifiers for its records.

No. Google Scholar is an academic search engine, but the records found in Google Scholar are scholarly sources.

No. Google Scholar collects research papers from all over the web, including grey literature and non-peer reviewed papers and reports.

Google Scholar does not provide any full text content itself, but links to the full text article on the publisher page, which can either be open access or paywalled content. Google Scholar tries to provide links to free versions, when possible.

The easiest way to access Google scholar is by using The Google Scholar Button. This is a browser extension that allows you easily access Google Scholar from any web page. You can install it from the Chrome Webstore .

Read a scholarly article

- Introduction

- Types of Scholarly Articles

- Interactive Article Diagram

- Reading for different purposes

The Structure of Scholarly Articles

Understanding the structure of scholarly articles is probably the most important part of understanding the article. The following structure is used in most scholarly articles, with the exception of (a) articles which are entirely literature reviews and (b) humanities articles.

These sections may not always be labeled this way, and sometimes multiple sections will be merged into one (like the introduction & literature review).

Article sections in the order in which they appear

- Literature Review (sometimes not labeled)

- Methodology

- Discussion / Conclusion

Article sections in order of importance

You should always read..., the abstract.

The abstract is usually a one-paragraph summary of the article. If the article doesn't seem useful after reading the abstract, don't read any further.

The Introduction & Literature Review

The introduction and literature review will help you understand:

- What the authors are writing about (their research questions )

- Why the authors are writing about this topic

- What others have written on this topic

The Discussion & Conclusion

The discussion and conclusion are at the end (just before the reference list). If the authors conducted an experiment, these sections should provide a summary of what the authors found, how their findings fit into the larger conversation about the topic, and what they believe should be researched in the future.

You may not need to read...

Methodology & results.

Do you need to read the methodology & results sections? It depends on your purpose for reading the article. You may want to read these sections if:

You're using the article as a source in a research paper *

If you're a first or second year student, or the research paper is on a topic unrelated to your major , you may want to skip over these sections. These sections are the most difficult to understand unless you have a high level of expertise in both the topic and research in your discipline.

If you're a junior, a senior, or a graduate student, and the article is in your discipline, then you most likely have the level of expertise necessary to understand most of these sections.

You're conducting your own research project *

You may be required to read this section in a particular class.

If you're not sure whether you should read these sections, ask your professor.

* Research has two meanings:

- Doing a thorough investigation of a topic (this would include things like searching Google, doing library research, etc.). When we say "research paper", we're referring to this kind of research.

- Trying to answer a specific question through experimentation and analysis. When we say "research project", we're referring to this kind of research.

The methodology section:

- Explains how the authors intend to answer their research questions

- What kind of data they are going to collect, and from who (or what)

- How they are going to (or how they did) collect that data

The results section usually involves analysis of the data collected.

- Search Google or Wikipedia for unfamiliar terms or concepts

- Ask your professor for help with other questions

Here's a real-life example:

- Researchers wanted to know whether pet ownership and/or medication had the best effects on high blood pressure caused by stress.

- They tested this by having some participants adopt a pet and take a medication, while others just took medication.

- The data they collected included blood pressure readings.

- They analyzed this data using statistical methods.

Source : Allen, K., Shykoff, B. E., & Izzo Jr, J. L. (2001). Pet ownership, but not ACE inhibitor therapy, blunts home blood pressure responses to mental stress. Hypertension, 38 (4), 815-820.

Other Important Sections to Review

These parts of a scholarly article probably won't contribute to your understanding of the article, but they're helpful in other ways:

References / Bibliographies

If you've read the introduction and literature review, you may have come across some sources that might be useful for your topic. All their sources should be at the end of the article or in footnotes! Check out our guide on finding sources using bibliographies .

Citation information

Many articles have the journal title, volume and issue numbers, and page numbers listed right on the article. This information is usually at the top of the first page of the article.

Author credentials

Author credentials are usually listed on the first page of the article, underneath the authors' names, or listed as footnotes. These credentials usually indicate where the authors work. This should help if you want to contact the authors with questions!

- << Previous: Types of Scholarly Articles

- Next: Interactive Article Diagram >>

- Last Updated: Dec 19, 2019 11:08 AM

- URL: https://libraryguides.oswego.edu/c.php?g=890416

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Scholarly Writing: Scholarly Writing

Introduction.

Scholarly writing is also known as academic writing. It is the genre of writing used in all academic fields. Scholarly writing is not better than journalism, fiction, or poetry; it is just a different category. Because most of us are not used to scholarly writing, it can feel unfamiliar and intimidating, but it is a skill that can be learned by immersing yourself in scholarly literature. During your studies at Walden, you will be reading, discussing, and producing scholarly writing in everything from discussion posts to dissertations. For Walden students, there are plenty of opportunities to practice this skill in a writing intensive environment.

The resources in the Grammar & Composition tab provide important foundations for scholarly writing, so please refer to those pages as well for help on scholarly writing. Similarly, scholarly writing can differ depending on style guide. Our resources follow the general guidelines of the APA manual, and you can find more APA help in the APA Style tab.

Read on to learn about a few characteristics of scholarly writing!

Writing at the Graduate Level

Writing at the graduate level can appear to be confusing and intimidating. It can be difficult to determine exactly what the scholarly voice is and how to transition to graduate-level writing. There are some elements of writing to consider when writing to a scholarly audience: word choice, tone, and effective use of evidence . If you understand and employ scholarly voice rules, you will master writing at the doctoral level.

Before you write something, ask yourself the following:

- Is this objective?

- Am I speaking as a social scientist? Am I using the literature to support my assertions?

- Could this be offensive to someone?

- Could this limit my readership?

Employing these rules when writing will help ensure that you are speaking as a social scientist. Your writing will be clear and concise, and this approach will allow your content to shine through.

Specialized Vocabulary

Scholarly authors assume that their audience is familiar with fundamental ideas and terms in their field, and they do not typically define them for the reader. Thus, the wording in scholarly writing is specialized, requiring previous knowledge on the part of the reader. You might not be able to pick up a scholarly journal in another field and easily understand its contents (although you should be able to follow the writing itself).

Take for example, the terms "EMRs" and "end-stage renal disease" in the medical field or the keywords scaffolding and differentiation in teaching. Perhaps readers outside of these fields may not be familiar with these terms. However, a reader of an article that contains these terms should still be able to understand the general flow of the writing itself.

Original Thought

Scholarly writing communicates original thought, whether through primary research or synthesis, that presents a unique perspective on previous research. In a scholarly work, the author is expected to have insights on the issue at hand, but those insights must be grounded in research, critical reading , and analysis rather than personal experience or opinion. Take a look at some examples below:

Needs Improvement: I think that childhood obesity needs to be prevented because it is bad and it causes health problems.

Better: I believe that childhood obesity must be prevented because it is linked to health problems and deaths in adults (McMillan, 2010).

Good: Georges (2002) explained that there "has never been a disease so devastating and yet so preventable as obesity" (p. 35). In fact, the number of deaths that can be linked to obesity are astounding. According to McMillan (2010), there is a direct correlation between childhood obesity and heart attacks later in their adult lives, and the American Heart Association's 2010 statistic sheet shows similar statistics: 49% of all heart attacks are preventable (AHA, 2010). Because of this correlation, childhood obesity is an issue that must be addressed and prevented to ensure the health of both children and adults.

Notice that the first example gives a personal opinion but cites no sources or research. The second example gives a bit of research but still emphasizes the personal opinion. The third example, however, still gives the writer's opinion (that childhood obesity must be addressed), but it does so by synthesizing the information from multiple sources to help persuade the reader.

Careful Citation

Scholarly writing includes careful citation of sources and the presence of a bibliography or reference list. The writing is informed by and shows engagement with the larger body of literature on the topic at hand, and all assertions are supported by relevant sources.

Crash Course in Scholarly Writing Video

Note that this video was created while APA 6 was the style guide edition in use. There may be some examples of writing that have not been updated to APA 7 guidelines.

- Crash Course in Scholarly Writing (video transcript)

Related Webinars

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Next Page: Common Course Assignments

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

Research Strategies

- Reference Resources

- News Articles

- Scholarly Sources

- Search Strategy

- OneSearch Tips

- Evaluating Information

- Revising & Polishing

- Presentations & Media

- MLA 9th Citation Style

- APA 7th Citation Style

- Other Citation Styles

- Citation Managers

- Annotated Bibliography

- Literature Review How to

What are Scholarly Sources?

Scholarly sources (also referred to as academic, peer-reviewed, or refereed sources) are written by subject experts with systems in place to ensure the quality and accuracy of information.

Scholarly sources include books from academic publishers, peer-reviewed journal articles , and reports from research institutes.

What is peer review? When a source has been peer-reviewed, it has undergone the review and scrutiny of a review board of colleagues in the author’s field. They evaluate this source as part of the body of research for a particular discipline and make recommendations regarding its publication in a journal, revisions prior to publication, or, in some cases, reject its publication.

How to Read a Scholarly Article

Scholarly sources often have a particular writing style and can be challenging to read compared to other types of sources. When reading scholarly literature, read strategically. Don't start by reading the article from start to finish but rather focus on the sections that will give you the information you need first. This will quickly let you know what the article is about and its relevancy for your research. It will also prepare you for when you’re ready to read the full article, giving you a mental map of its structure and purpose.

Here is a suggestion on how to read a scholarly article and which sections to focus on first.

Show/Hide Infographic Text

- Read the abstract An abstract is a summary of the article, and will give you an idea of what the article is about and how it will be written. If there are lots of complicated subject-specific words in the abstract, the article will be just as hard to read.

- Read the conclusion This is where the author will repeat all of their ideas and their findings. Some authors even use this section to compare their study to others. By reading this, you will notice a few things you missed, and will get another overview of the content.

- Read the first paragraph or the introduction This is usually where the author will lay out their plan for the article and describe the steps they will take to talk about their topic. By reading this, you will know what parts of the article will be most relevant to your topic!

- Read the first sentence of every paragraph These are called topic sentences, and will usually introduce the idea for the paragraph that follows. By reading this, you can make sure that the paragraph has information relevant to your topic before you read the entire thing.

- The rest of the article Now that you have gathered the idea of the article through the abstract, conclusion, introduction, and topic sentences, you can read the rest of the article!

- To review: Abstract, Conclusion, Introduction, Topic Sentences, Entire Article

How can I tell if an article is scholarly?

There are several ways to determine whether an article qualifies as "scholarly" or "peer-reviewed". First it depends on how you found the source. If you are using library resources such as OneSearch or databases such as Academic Search Premier - you can limit the search to peer-reviewed journals. Many databases will have this feature to allow you to limit searches for scholarly, peer-reviewed, or academic sources.

Here are some qualities that set them apart from "popular" sources such as newspapers, magazines, etc.

- Purpose : is to communicate research and scholarly ideas.

- Author(s): are researchers, scholars, and/or faculty, and they will typically have an institutional affiliation listed.

- Citations: should have a works cited/references/bibliography with full citations.

- Length: usually long, typically range between 8 and 30+ pages.

- Audience: is other researchers, scholars, and/or faculty.

- Coverage: tends to be focused and narrow.

- Publisher: are usually university presses, professional associations, academic institutions, and commercial publishers.

- Peer-review process can take months if not years--from the time that an article is submitted for review and ultimate publication.

- What it is NOT: some parts of scholarly journals are not peer-reviewed. These include book reviews and letters/responses to the editor.

Ulrich's Periodicals Directory (often referred to as UlrichsWeb ) is a database that the University Library subscribes to. You may be told to "check Ulrich's," but what does that mean? Ulrich's will tell you if a journal is still in print, available online, where it is indexed, and most critically, what type of journal it is (scholarly, trade, popular, etc.). This is useful for students being asked to find specific types of sources.

Search using the name of the journal and then look for the black and white referee jacket. This indicates that the journals content is peer-reviewed.

How can I tell if a book is scholarly?

Look for several things to determine if a book is scholarly:

- Publisher: who is the publisher? University presses (e.g. Stanford University Press, University of Pittsburgh Press, University of Washington press) publish scholarly, academic books.

- Author: what are the author's credentials? Typically written by a scholar/researcher with academic credentials listed.

- Content: scholarly books always have information cited in the text, in footnotes, and have a bibliography or references. Scholarly books also often contain a combination of primary and secondary sources.

- Style: Language is formal and technical; usually contains discipline-specific jargon.

Where to find Scholarly Sources?

The library subscribes to over 250 databases! You can browse databases by Subject Area and read the description for the different types of resources you can find searching that particular database. Otherwise, here are some general multisubject databases and a good place to get started.

- Academic Search Premier (EBSCO) This link opens in a new window Multi-disciplinary database provides full text for more than 4,600 journals, including full text for nearly 3,900 peer-reviewed titles.

- JSTOR This link opens in a new window Archive of back issues of core scholarly journals across a wide range of subjects, with an emphasis on arts, humanities, and social sciences. Also includes current content for select journals and a large collection of University Press books.

- OneSearch Here you can search for books and e-books, videos, articles, digital media, and more. Make sure to use the limiter on the left hand side and limit to Peer-Reviewed Journals.

- Project MUSE This link opens in a new window Full text of over 300 peer-reviewed journals published by university presses and scholarly societies with emphasis on humanities and social sciences.

- << Previous: News Articles

- Next: Search Strategy >>

- Last Updated: Apr 8, 2024 9:46 AM

- URL: https://libguides.csun.edu/research-strategies

Report ADA Problems with Library Services and Resources

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

Research articles

SCB-YOLOv5: a lightweight intelligent detection model for athletes’ normative movements

Fuchs’ uveitis syndrome: a 20-year experience in 466 patients.

- Farzan Kianersi

- Hamidreza Kianersi

- Pegah Noorshargh

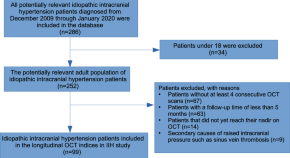

Longitudinal optical coherence tomography indices in idiopathic intracranial hypertension

- Rachel Shemesh

- Ruth Huna-Baron

A psycholinguistic study of intergroup bias and its cultural propagation

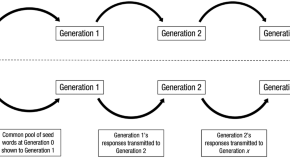

- Daniel Schmidtke

- Victor Kuperman

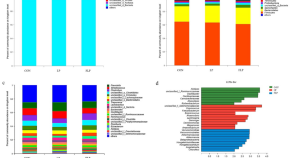

Effects of Lactobacillus -fermented low-protein diets on the growth performance, nitrogen excretion, fecal microbiota and metabolomic profiles of finishing pigs

- Dongyan Zhang

Genetic diversity and antagonistic properties of Trichoderma strains from the crop rhizospheres in southern Rajasthan, India

- Prashant P. Jambhulkar

- Bhumica Singh

- Pratibha Sharma

Equilibrium and kinetic modeling of Cr(VI) removal by novel tolerant bacteria species along with zero-valent iron nanoparticles

- Shashank Garg

- Simranjeet Singh

- Joginder Singh

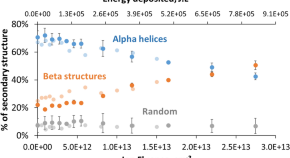

Radiolysis of myoglobin concentrated gels by protons: specific changes in secondary structure and production of carbon monoxide

- Nicolas Ludwig

- Catherine Galindo

- Quentin Raffy

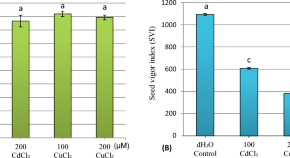

Embryo growth alteration and oxidative stress responses in germinating Cucurbita pepo seeds exposed to cadmium and copper toxicity

- Smail Acila

- Samir Derouiche

- Nora Allioui

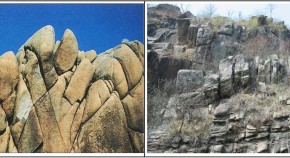

Shear damage mechanisms of jointed rock mass: a macroscopic and mesoscopic study

- Chengcheng Zheng

A noise audit of human-labeled benchmarks for machine commonsense reasoning

- Mayank Kejriwal

- Henrique Santos

- Deborah L. McGuinness

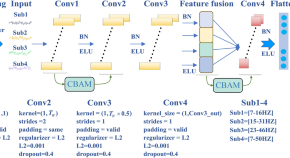

A fused multi-subfrequency bands and CBAM SSVEP-BCI classification method based on convolutional neural network

- Dongyang Lei

- Chaoyi Dong

Transcriptomics analysis of long non-coding RNAs in smooth muscle cells from patients with peripheral artery disease and diabetes mellitus

- Yankey Yundung

- Shafeeq Mohammed

- Jaroslav Pelisek

Building adjustment capacity to cope with running water in cultured grass carp through flow stimulation conditions

- Qingrong Xie

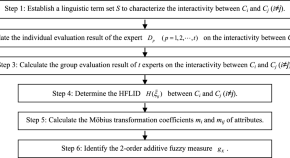

A 2-order additive fuzzy measure identification method based on hesitant fuzzy linguistic interaction degree and its application in credit assessment

An air door opening and closing time identification and stage division method based on the wind speed data of a single sensor

- Wentian Shang

Implementation of a hybrid neural network control technique to a cascaded MLI based SAPF

- Rashmi Rekha Behera

- Ashish Ranjan Dash

- Demissie Jobir Gelmecha

Molecular modelling studies and in vitro enzymatic assays identified A 4-(nitrobenzyl)guanidine derivative as inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro

- Kaio Maciel de Santiago-Silva

- Priscila Goes Camargo

- Marcelle de Lima Ferreira Bispo

Study on dynamic characteristics of cavitation in underwater explosion with large charge

- Xian-pi Zhang

- Yuan-Qing Xu

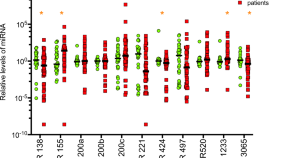

Circulating microRNA-155-3p levels predicts response to first line immunotherapy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma

- Maryam Soleimani

- Lucia Nappi

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

How to Think about Criminal Justice Reform: Conceptual and Practical Considerations

Charis e. kubrin.

Social Ecology II, University of California, Room 3309, Irvine, CA 92697-7080 USA

Rebecca Tublitz

How can we improve the effectiveness of criminal justice reform efforts? Effective reform hinges on shared understandings of what the problem is and shared visions of what success looks like. But consensus is hard to come by, and there has long been a distinction between “policy talk” or how problems are defined and solutions are promoted, and “policy action” or the design and adoption of certain policies. In this essay, we seek to promote productive thinking and talking about, as well as designing of, effective and sustainable criminal justice reforms. To this end, we offer reflections on underlying conceptual and practical considerations relevant for both criminal justice policy talk and action.

Across the political spectrum in the United States, there is agreement that incarceration and punitive sanctions cannot be the sole solution to crime. After decades of criminal justice expansion, incarceration rates peaked between 2006 and 2008 and have dropped modestly, but consistently, ever since then (Gramlich, 2021 ). Calls to ratchet up criminal penalties to control crime, with some exceptions, are increasingly rare. Rather, where bitter partisanship divides conservatives and progressives on virtually every other issue, bipartisan support for criminal justice reform is commonplace. This support has yielded many changes in recent years: scaling back of mandatory sentencing laws, limiting sentencing enhancements, expanding access to non-prison alternatives for low-level drug and property crimes, reducing revocations of community supervision, and increasing early release options (Subramanian & Delaney, 2014 ). New laws passed to reduce incarceration have outpaced punitive legislation three-to-one (Beckett et al., 2016 , 2018 ). Rather than the rigid “law and order” narrative that characterized the dominant approach to crime and punishment since the Nixon administration, policymakers and advocates have found common ground in reform conversations focused on cost savings, evidence-based practice, and being “smart on crime.” A “new sensibility” prevails (Phelps, 2016 ).

Transforming extensive support for criminal justice reform into substantial reductions in justice-involved populations has proven more difficult, and irregular. While the number of individuals incarcerated across the nation has declined, the U.S. continues to have the highest incarceration rate in the world, with nearly 1.9 million people held in state and federal prisons, local jails, and detention centers (Sawyer & Wagner, 2022 ; Widra & Herring, 2021 ). Another 3.9 million people remain on probation or parole (Kaeble, 2021 ). And, not all jurisdictions have bought into this new sensibility: rural and suburban reliance on prisons has increased during this new era of justice reform (Kang-Brown & Subramanian, 2017 ). Despite extensive talk of reform, achieving actual results “is about as easy as bending granite” (Petersilia, 2016 :9).

How can we improve the effectiveness of criminal justice reform? At its core, a reform is an effort to ameliorate an undesirable condition, eliminate an identified problem, achieve a goal, or strengthen an existing (successful) policy. Scholarship yields real insights into effective programming and practice in response to a range of issues in criminal justice. Equally apparent, however, is the lack of criminological knowledge incorporated into the policymaking process. Thoughtful are proposals to improve the policy-relevance of criminological knowledge and increase communication between research and policy communities (e.g., Blomberg et al., 2016 ; Mears, 2022 ). But identifying what drives effective criminal justice reform is not so straightforward. For one, the goals of reform vary across stakeholders: Should reform reduce crime and victimization? Focus on recidivism? Increase community health and wellbeing? Ensure fairness in criminal justice procedure? Depending upon who is asked, the answer differs. Consensus on effective reform hinges on shared understandings of what the problem is and shared visions of what success looks like. Scholars of the policy process often distinguish “policy talk,” or how problems are defined and solutions are promoted, from “policy action,” or the design and adoption of policy solutions, to better understand the drivers of reform and its consequences. This distinction is relevant to criminal justice reform (Bartos & Kubrin, 2018 :2; Tyack & Cuban, 1995 ).

We argue that an effective approach to criminal justice reform—one that results in policy action that matches policy talk—requires clarity regarding normative views about the purpose of punishment, appreciation of practical realities involved in policymaking, and insight into how the two intersect. To this end, in this essay we offer critical reflections on underlying conceptual and practical considerations that bear on criminal justice policy talk and action.

Part I. Conceptual Considerations: Narratives of Crime and Criminal Justice

According to social constructionist theory, the creation of knowledge is rooted in interactions between individuals through common language and shared meanings in social contexts (Berger & Luckmann, 1966 ). Common language and shared meanings create ways of thinking, or narratives, that socially construct our reality and profoundly influence public definitions of groups, events, and social phenomena, including crime and criminal justice. As such, any productive conversation about reform must engage with society’s foundational narratives about crime and criminal justice, including views about the rationales for punishment.

I. Rationales of Punishment

What is criminal justice? What purpose does our criminal justice system serve? Answers to these questions are found in the theories, organization, and practices of criminal justice. A starting point for discovery is the fact that criminal justice is a system for the implementation of punishment (Cullen & Gilbert, 1982 ). This has not always been the case but today, punishment is largely meted out in our correctional system, or prisons and jails, which embody rationales for punishment including retribution, deterrence, incapacitation, rehabilitation, and restoration. These rationales offer competing purposes and goals, and provide varying blueprints for how our criminal justice system should operate.

Where do these rationales come from? They derive, in part, from diverse understandings and explanations about the causes of crime. While many theories exist, a useful approach for thinking about crime and its causes is found in the two schools of criminological thought, the Classical and Positivist Schools of Criminology. These Schools reflect distinct ideological assumptions, identify competing rationales for punishment, and suggest unique social policies to address crime—all central to any discussion of criminal justice reform.

At its core, the Classical School sought to bring about reform of the criminal justice systems of eighteenth century Europe, which were characterized by such abuses as torture, presumption of guilt before trial, and arbitrary court procedures. Reformers of the Classical School, most notably Cesare Beccaria and Jeremy Bentham, were influenced by social contract theorists of the Enlightenment, a cultural movement of intellectuals in late seventeenth and eighteenth century Europe that emphasized reason and individualism rather than tradition, along with equality. Central assumptions of the Classical School include that people are rational and possessed of free will, and thus can be held responsible for their actions; that humans are governed by the principle of utility and, as such, seek pleasure or happiness and avoid pain; and that, to prevent crime, punishments should be just severe enough such that the pain or unhappiness created by the punishment outweighs any pleasure or happiness derived from crime, thereby deterring would-be-offenders who will see that “crime does not pay.”

The guiding concept of the Positivist School was the application of the scientific method to study crime and criminals. In contrast to the Classical School’s focus on rational decision-making, the Positivist School adopted a deterministic viewpoint, which suggests that crime is determined by factors largely outside the control of individuals, be they biological (such as genetics), psychological (such as personality disorder), or sociological (such as poverty). Positivists also promote the idea of multiple-factor causation, or that crime is caused by a constellation of complex forces.

When it comes to how we might productively think about reform, a solid understanding of these schools is necessary because “…the unique sets of assumptions of two predominant schools of criminological thought give rise to vastly different explanations of and prescriptions for the problem of crime” (Cullen & Gilbert, 1982 :36). In other words, the two schools of thought translate into different strategies for policy. They generate rationales for punishment that offer competing narratives regarding how society should handle those who violate the law. These rationales for punishment motivate reformers, whether the aim is to “rehabilitate offenders” or “get tough on crime,” influencing policy and practice.

The earliest rationale for punishment is retribution. Consistent with an individual’s desire for revenge, the aim is that offenders experience an unpleasant consequence for violating the law. Essentially, criminals should get what they deserve. While other rationales focus on changing future behavior, retribution focuses on an individual’s past actions and implies they have rightfully “earned” their punishment. Punishment, then, expresses moral disapproval for the criminal act committed. Advocates of retribution are not concerned with controlling crime; rather, they are in the business of “doing justice.” The death penalty and sentencing guidelines, a system of recommended sentences based upon offense (e.g., level of seriousness) and offender (e.g., number and type of prior offenses) characteristics, reflect basic principles of retribution.

Among the most popular rationales for punishment is deterrence, which refers to the idea that those considering crime will refrain from doing so out of a fear of punishment, consistent with the Classical School. Deterrence emphasizes that punishing a person also sends a message to others about what they can expect if they, too, violate the law. Deterrence theory provides the basis for a particular kind of correctional system that punishes the crime, not the criminal. Punishments are to be fixed tightly to specific crimes so that offenders will soon learn that the state means business. The death penalty is an example of a policy based on deterrence (as is obvious, these rationales are not mutually exclusive) as are three-strikes laws, which significantly increase prison sentences of those convicted of a felony who have been previously convicted of two or more violent crimes or serious felonies.

Another rationale for punishment, incapacitation, has the goal of reducing crime by incarcerating offenders or otherwise restricting their liberty (e.g., community supervision reflected in probation, parole, electronic monitoring). Uninterested in why individuals commit crime in the first place, and with no illusion they can be reformed, the goal is to remove individuals from society during a period in which they are expected to reoffend. Habitual offender laws, which target repeat offenders or career criminals and provide for enhanced or exemplary punishments or other sanctions, reflect this rationale.

Embodied in the term “corrections” is the notion that those who commit crime can be reformed, that their behavior can be “corrected.” Rehabilitation refers to when individuals refrain from crime—not out of a fear of punishment—but because they are committed to law-abiding behavior. The goal, from this perspective, is to change the factors that lead individuals to commit crime in the first place, consistent with Positivist School arguments. Unless criminogenic risks are targeted for change, crime will continue. The correctional system should thus be arranged to deliver effective treatment; in other words, prisons must be therapeutic. Reflective of this rationale is the risk-need-responsibility (RNR) model, used to assess and rehabilitate offenders. Based on three principles, the risk principle asserts that criminal behavior can be reliably predicted and that treatment should focus on higher risk offenders, the need principle emphasizes the importance of criminogenic needs in the design and delivery of treatment and, the responsivity principle describes how the treatment should be provided.

When a crime takes place, harm occurs—to the victim, to the community, and even to the offender. Traditional rationales of punishment do not make rectifying this harm in a systematic way an important goal. Restoration, or restorative justice, a relatively newer rationale, aims to rectify harms and restore injured parties, perhaps by apologizing and providing restitution to the victim or by doing service for the community. In exchange, the person who violated the law is (ideally) forgiven and accepted back into the community as a full-fledged member. Programs associated with restorative justice are mediation and conflict-resolution programs, family group conferences, victim-impact panels, victim–offender mediation, circle sentencing, and community reparative boards.

II. Narratives of Criminal Justice

Rationales for punishment, thus, are many. But from where do they arise? They reflect and reinforce narratives of crime and criminal justice (Garland, 1991 ). Penological and philosophical narratives constitute two traditional ways of thinking about criminal justice. In the former, punishment is viewed essentially as a technique of crime control. This narrative views the criminal justice system in instrumental terms, as an institution whose overriding purpose is the management and control of crime. The focal question of interest is a technical one: What works to control crime? The latter, and second, narrative considers the philosophy of punishment. It examines the normative foundations on which the corrections system rests. Here, punishment is set up as a distinctively moral problem, asking how penal sanctions can be justified, what their proper objectives should be, and under what circumstances they can be reasonably imposed. The central question here is “What is just?”.

A third narrative, “the sociology of punishment,” conceptualizes punishment as a social institution—one that is distinctively focused on punishment’s social forms, functions, and significance in society (Garland, 1991 ). In this narrative, punishment, and the criminal justice system more broadly, is understood as a cultural and historical artifact that is concerned with the control of crime, but that is shaped by an ensemble of social forces and has significance and impacts that reach well beyond the population of criminals (pg. 119). A sociology of punishment narrative raises important questions: How do specific penal measures come into existence?; What social functions does punishment perform?; How do correctional institutions relate to other institutions?; How do they contribute to social order or to state power or to class domination or to cultural reproduction of society?; What are punishment’s unintended social effects, its functional failures, and its wider social costs? (pg. 119). Answers to these questions are found in the sociological perspectives on punishment, most notably those by Durkheim (punishment is a moral process, functioning to preserve shared values and normative conventions on which social life is based), Marx (punishment is a repressive instrument of class domination), Foucault (punishment is one part of an extensive network of “normalizing” practices in society that also includes school, family, and work), and Elias (punishment reflects a civilizing process that brings with it a move toward the privatization of disturbing events), among others.