The Speech Writing Process

By Philippe John Fresnillo Sipacio & Anne Balgos (Page 62)

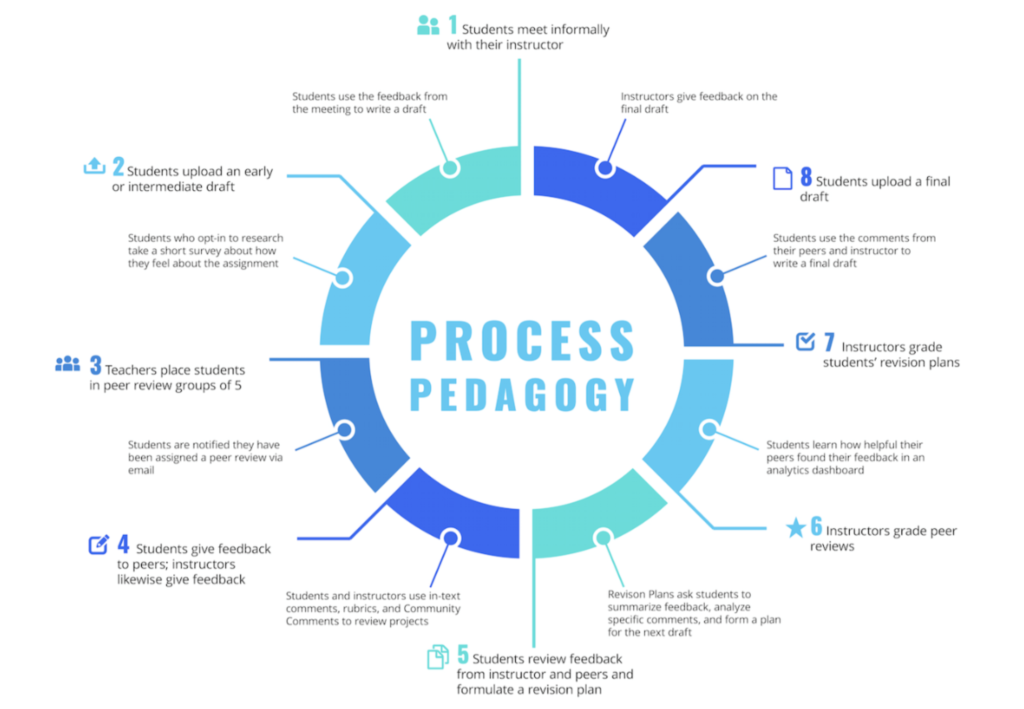

Just like events planning, or any other activities, writing an effective speech follows certain steps or processes. The process for writing is not chronological or linear ; rather, it is recursive . That means you have the opportunity to repeat a writing procedure indefinitely, or produce multiple

drafts first before you can settle on the right one.

By Philippe John Fresnillo Sipacio & Anne Balgos

The following are the components of the speech writing process.

• Audience analysis entails looking into the profile of your target audience. This is done so you can tailor-fit your speech content and delivery to your audience. The profile includes the following information.

Q demography (age range, male-female ratio, educational background and affiliations or degree program taken, nationality, economic status, academic or corporate designations)

Q situation (time, venue, occasion, and size)

Q psychology (values, beliefs, attitudes, preferences, cultural and racial ideologies , and needs)

A sample checklist is presented below.

The purpose for writing and delivering the speech can be classified into three — to inform, to entertain, or to persuade .

- An informative speech provides the audience with a clear understanding of the concept or idea presented by the speaker.

- An entertainment speech provides the audience with amusement.

- A persuasive speech provides the audience with well-argued ideas that can influence their own beliefs and decisions.

The purpose can be general and specific. Study the examples below to see the differences. The general purpose is to inform ….

These are examples of specific purpose….

- To inform Grade 11 students about the process of conducting an

- automated student government election

- To inform Grade 11 students about the definition and relevance of

information literacy today

- To inform Grade 11 students about the importance of effective money management

The purpose can be general and specific. Study the examples below to see the differences. The general purpose is to entertain ….

- To entertain Grade 11 students with his/her funny experiences in

automated election

- To entertain Grade 11 students with interesting observations of people who lack information literacy

- To entertain Grade 11 students with the success stories of the people in the community

The purpose can be general and specific. Study the examples below to see the differences. The general purpose is to persuade ….

- To persuade the school administrators to switch from manual to

- To persuade Grade 11 students to develop information literacy skills

- To persuade the school administrators to promote financial literacy

- among students

The topic is your focal point of your speech, which can be determined once you have decided on your purpose. If you are free to decide on a topic, choose one that really interests you. There are a variety of strategies used in selecting a topic, such as using your personal experiences, discussing with your family members or friends, free writing, listing, asking questions, or semantic webbing .

Narrowing down a topic means making your main idea more specific and focused. The strategies in selecting a topic can also be used when you narrow down a topic. In the example below, “Defining and developing effective money management skills of Grade 11 students” is the specific topic out of a general one, which is “ Effective money management.”

Data gathering is the stage where you collect ideas, information, sources, and references relevant or related to your specific topic. This can be done by visiting the library, browsing the web, observing a certain phenomenon or event related to your topic, or conducting an

interview or survey. The data that you will gather will be very useful in making your speech informative, entertaining, or persuasive .

Writing patterns, in general, are structures that will help you organize the ideas related to your topic. Examples are biographical , categorical / topical , causal , chronological , comparison / contrast , problem-solution, and spatial .

The different writing patterns

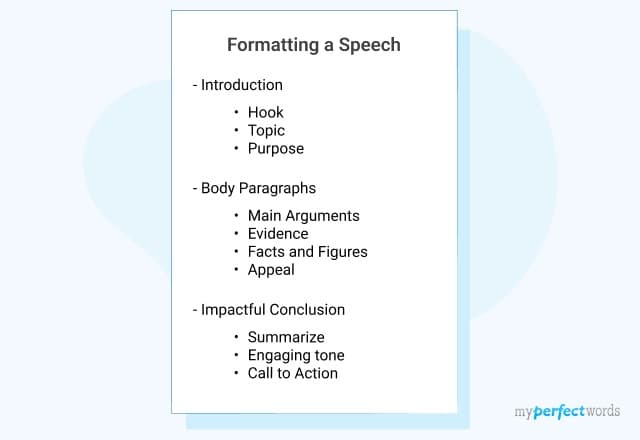

An outline is a hierarchical list that shows the relationship of your ideas. Experts in public speaking state that once your outline is ready, two-thirds of your speech writing is finished. A good outline helps you see that all the ideas are in line with your main idea or message. The elements of an outline include introduction, body, and conclusion. Write your outline based on how you want your ideas to develop. Below are some of the suggested formats.

The body of the speech provides explanations, examples, or any details that can help you deliver your purpose and explain the main idea of your speech. One major consideration in developing the body of your speech is the focus or central idea. The body of your speech should only have one central idea.

The following are some strategies to highlight your main idea.

- Present real-life or practical examples

- Show statistics

- Present comparisons

- Share ideas from the experts or practitioners

The introduction is the foundation of your speech. Here, your primary goal is to get the attention of your audience and present the subject or main idea of your speech. Your first few words should do so. The following are some strategies.

- Use a real-life experience and connect that experience to your subject.

- Use practical examples and explain their connection to your subject.

- Start with a familiar or strong quote and then explain what it means.

- Use facts or statistics and highlight their importance to your subject.

- Tell a personal story to illustrate your point.

The conclusion restates the main idea of your speech. Furthermore, it provides a summary, emphasizes the message, and calls for action. While the primary goal of the introduction is to get the attention of your audience, the conclusion aims to leave the audience with a memorable statement.

The following are some strategies.

- Begin your conclusion with a restatement of your message.

- Use positive examples, encouraging words, or memorable lines from songs or stories familiar to your audience.

- Ask a question or series of questions that can make your audience reflect or ponder.

Editing/Revising your written speech involves correcting errors in mechanics, such as grammar, punctuation, capitalization, unity, coherence, and others. Andrew Dlugan (2013), an awar di ng public speaker, lists six power principles for speech editing.

- Edit for focus.

“So, what’s the point? What’s the message of the speech?”

Ensure that everything you have written, from introduction to conclusion, is related to your central message.

- Edit for clarity.

“I don’t understand the message because the examples or supporting details were confusing.”

Make all ideas in your speech clear by arranging them in logical order (e.g., main idea first then supporting details, or supporting details first then main idea).

- Edit for concision.

“The speech was all over the place; the speaker kept talking endlessly as if no one was listening to him/her.”

Keep your speech short, simple, and clear by eliminating unrelated stories and sentences and by using simple words.

- Edit for continuity.

“The speech was too difficult to follow; I was lost in the middle.”

Keep the flow of your presentation smooth by adding transition words and phrases.

- Edit for variety.

“I didn’t enjoy the speech because it was boring.”

Add spice to your speech by shifting tone and style from formal to conversational and vice-versa, moving around the stage, or adding humor.

- Edit for impact and beauty.

“There’s nothing really special about the speech.”

Make your speech memorable by using these strategies: surprise the audience, use vivid descriptive images, write well-crafted and memorable lines, and use figures of speech.

Rehearsing gives you an opportunity to identify what works and what does not work for you and for your target audience. Some strategies include reading your speech aloud, recording for your own analysis or for your peers or coaches to give feedback on your delivery. The best

thing to remember at this stage is: “Constant practice makes perfect.”

Some Guidelines in Speech Writing

1. Keep your words short and simple. Your speech is meant to be heard by your audience, not read.

2. Avoid jargon , acronyms, or technical words because they can confuse your audience.

3. Make your speech more personal. Use the personal pronoun “I,” but take care not to overuse it. When you need to emphasize collectiveness with your audience, use the personal pronoun “we.”

4. Use active verbs and contractions because they add to the personal and conversational tone of your speech.

5. Be sensitive of your audience. Be very careful with your language, jokes, and nonverbal cues.

6. Use metaphors and other figures of speech to effectively convey your point.

7. Manage your time well; make sure that the speech falls under the time limit.

Rice Speechwriting

Beginners guide to what is a speech writing, what is a speech writing: a beginner’s guide, what is the purpose of speech writing.

The purpose of speech writing is to craft a compelling and effective speech that conveys a specific message or idea to an audience. It involves writing a script that is well-structured, engaging, and tailored to the speaker’s delivery style and the audience’s needs.

Have you ever been called upon to deliver a speech and didn’t know where to start? Or maybe you’re looking to improve your public speaking skills and wondering how speech writing can help. Whatever the case may be, this beginner’s guide on speech writing is just what you need. In this blog, we will cover everything from understanding the art of speech writing to key elements of an effective speech. We will also discuss techniques for engaging speech writing, the role of audience analysis in speech writing, time and length considerations, and how to practice and rehearse your speech. By the end of this article, you will have a clear understanding of how speech writing can improve your public speaking skills and make you feel confident when delivering your next big presentation.

Understanding the Art of Speech Writing

Crafting a speech involves melding spoken and written language. Tailoring the speech to the audience and occasion is crucial, as is captivating the audience and evoking emotion. Effective speeches utilize rhetorical devices, anecdotes, and a conversational tone. Structuring the speech with a compelling opener, clear points, and a strong conclusion is imperative. Additionally, employing persuasive language and maintaining simplicity are essential elements. The University of North Carolina’s writing center greatly emphasizes the importance of using these techniques.

The Importance of Speech Writing

Crafting a persuasive and impactful speech is essential for reaching your audience effectively. A well-crafted speech incorporates a central idea, main point, and a thesis statement to engage the audience. Whether it’s for a large audience or different ways of public speaking, good speech writing ensures that your message resonates with the audience. Incorporating engaging visual aids, an impactful introduction, and a strong start are key features of a compelling speech. Embracing these elements sets the stage for a successful speech delivery.

The Role of a Speech Writer

A speechwriter holds the responsibility of composing speeches for various occasions and specific points, employing a speechwriting process that includes audience analysis for both the United States and New York audiences. This written text is essential for delivering impactful and persuasive messages, often serving as a good start to a great speech. Utilizing NLP terms like ‘short sentences’ and ‘persuasion’ enhances the content’s quality and relevance.

Key Elements of Effective Speech Writing

Balancing shorter sentences with longer ones is essential for crafting an engaging speech. Including subordinate clauses and personal stories caters to the target audience and adds persuasion. The speechwriting process, including the thesis statement and a compelling introduction, ensures the content captures the audience’s attention. Effective speech writing involves research and the generation of new ideas. Toastmasters International and the Writing Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill provide valuable resources for honing English and verbal skills.

Clarity and Purpose of the Speech

Achieving clarity, authenticity, and empathy defines a good speech. Whether to persuade, inform, or entertain, the purpose of a speech is crucial. It involves crafting persuasive content with rich vocabulary and clear repetition. Successful speechwriting demands a thorough understanding of the audience and a compelling introduction. Balancing short and long sentences is essential for holding the audience’s attention. This process is a fusion of linguistics, psychology, and rhetoric, making it an art form with a powerful impact.

Identifying Target Audience

Tailoring the speechwriting process hinges on identifying the target audience. Their attention is integral to the persuasive content, requiring adaptation of the speechwriting process. A speechwriter conducts audience analysis to capture the audience’s attention, employing new york audience analysis methods. Ensuring a good introduction and adapting the writing process for the target audience are key features of a great speech. Effective speechwriters prioritize the audience’s attention to craft compelling and persuasive speeches.

Structuring Your Speech

The speechwriting process relies on a well-defined structure, crucial to both the speech’s content and the writing process. It encompasses a compelling introduction, an informative body, and a strong conclusion. This process serves as a foundation for effective speeches, guiding the speaker through a series of reasons and a persuasive speechwriting definition. Furthermore, the structure, coupled with audience analysis, is integral to delivering a great speech that resonates with the intended listeners.

The Process of Writing a Speech

Crafting a speech involves composing the opening line, developing key points, and ensuring a strong start. Effective speech writing follows a structured approach, incorporating rhetorical questions and a compelling introduction. A speechwriter’s process includes formulating a thesis statement, leveraging rhetorical questions, and establishing a good start. This process entails careful consideration of the audience, persuasive language, and engaging content. The University of North Carolina’s writing center emphasizes the significance of persuasion, clarity, and concise sentences in speechwriting.

Starting with a Compelling Opener

A speechwriting process commences with a captivating opening line and a strong introduction, incorporating the right words and rhetorical questions. The opening line serves as both an introduction and a persuasive speech, laying the foundation for a great speechwriting definition. Additionally, the structure of the speechwriting process, along with audience analysis, plays a crucial role in crafting an effective opening. Considering these elements is imperative when aiming to start a speech with a compelling opener.

Developing the Body of the Speech

Crafting the body of a speech involves conveying the main points with persuasion and precision. It’s essential to outline the speechwriting process, ensuring a clear and impactful message. The body serves as a structured series of reasons, guiding the audience through the content. Through the use of short sentences and clear language, the body of the speech engages the audience, maintaining their attention. Crafting the body involves the art of persuasion, using the power of words to deliver a compelling message.

Crafting a Strong Conclusion

Crafting a strong conclusion involves reflecting the main points of the speech and summarizing key ideas, leaving the audience with a memorable statement. It’s the final chance to leave a lasting impression and challenge the audience to take action or consider new perspectives. A good conclusion can make the speech memorable and impactful, using persuasion and English language effectively to drive the desired response from the audience. Toastmasters International emphasizes the importance of a strong conclusion in speechwriting for maximum impact.

Techniques for Engaging Speech Writing

Engage the audience’s attention using rhetorical questions. Create a connection through anecdotes and personal stories. Emphasize key points with rhetorical devices to capture the audience’s attention. Maintain interest by varying sentence structure and length. Use visual aids to complement the spoken word and enhance understanding. Incorporate NLP terms such as “short sentences,” “writing center,” and “persuasion” to create engaging and informative speech writing.

Keeping the Content Engaging

Captivating the audience’s attention requires a conversational tone, alliteration, and repetition for effect. A strong introduction sets the tone, while emotional appeals evoke responses. Resonating with the target audience ensures engagement. Utilize short sentences, incorporate persuasion, and vary sentence structure to maintain interest. Infuse the speech with NLP terms like “writing center”, “University of North Carolina”, and “Toastmasters International” to enhance its appeal. Engaging content captivates the audience and compels them to listen attentively.

Maintaining Simplicity and Clarity

To ensure clarity and impact, express ideas in short sentences. Use a series of reasons and specific points to effectively convey the main idea. Enhance the speech with the right words for clarity and comprehension. Simplify complex concepts by incorporating anecdotes and personal stories. Subordinate clauses can provide structure and clarity in the speechwriting process.

The Power of Nonverbal Communication

Nonverbal cues, such as body language and gestures, can add emphasis to your spoken words, enhancing the overall impact of your speech. By incorporating visual aids and handouts, you can further augment the audience’s understanding and retention of key points. Utilizing a conversational tone and appropriate body language is crucial for establishing a genuine connection with your audience. Visual aids and gestures not only aid comprehension but also help in creating a lasting impression, captivat**ing** the audience with compelling visual elements.

The Role of Audience Analysis in Speech Writing

Tailoring a speech to the audience’s needs is paramount. Demographics like age, gender, and cultural background must be considered. Understanding the audience’s interests and affiliation is crucial for delivering a resonating speech. Content should be tailored to specific audience points of interest, engaging and speaking to their concerns.

Understanding Audience Demographics

Understanding the varied demographics of the audience, including age and cultural diversity, is crucial. Adapting the speech content to resonate with a diverse audience involves tailoring it to the different ways audience members process and interpret information. This adaptation ensures that the speech can effectively engage with the audience, no matter their background or age. Recognizing the importance of understanding audience demographics is key for effective audience analysis. By considering these factors, the speech can be tailored to meet the needs and preferences of the audience, resulting in a more impactful delivery.

Considering the Audience Size and Affiliation

When tailoring a speech, consider the audience size and affiliation to influence the tone and content effectively. Adapt the speech content and delivery to resonate with a large audience and different occasions, addressing the specific points of the target audience’s affiliation. By delivering a speech tailored to the audience’s size and specific points of affiliation, you can ensure that your message is received and understood by all.

Time and Length Considerations in Speech Writing

Choosing the appropriate time for your speech and determining its ideal length are crucial factors influenced by the purpose and audience demographics. Tailoring the speech’s content and structure for different occasions ensures relevance and impact. Adapting the speech to specific points and the audience’s demographics is key to its effectiveness. Understanding these time and length considerations allows for effective persuasion and engagement, catering to the audience’s diverse processing styles.

Choosing the Right Time for Your Speech

Selecting the optimal start and opening line is crucial for capturing the audience’s attention right from the beginning. It’s essential to consider the timing and the audience’s focus to deliver a compelling and persuasive speech. The right choice of opening line and attention to the audience set the tone for the speech, influencing the emotional response. A good introduction and opening line not only captivate the audience but also establish the desired tone for the speech.

Determining the Ideal Length of Your Speech

When deciding the ideal length of your speech, it’s crucial to tailor it to your specific points and purpose. Consider the attention span of your audience and the nature of the event. Engage in audience analysis to understand the right words and structure for your speech. Ensure that the length is appropriate for the occasion and target audience. By assessing these factors, you can structure your speech effectively and deliver it with confidence and persuasion.

How to Practice and Rehearse Your Speech

Incorporating rhetorical questions and anecdotes can deeply engage your audience, evoking an emotional response that resonates. Utilize visual aids, alliteration, and repetition to enhance your speech and captivate the audience’s attention. Effective speechwriting techniques are essential for crafting a compelling introduction and persuasive main points. By practicing a conversational tone and prioritizing clarity, you establish authenticity and empathy with your audience. Develop a structured series of reasons and a solid thesis statement to ensure your speech truly resonates.

Techniques for Effective Speech Rehearsal

When practicing your speech, aim for clarity and emphasis by using purposeful repetition and shorter sentences. Connect with your audience by infusing personal stories and quotations to make your speech more relatable. Maximize the impact of your written speech when spoken by practicing subordinate clauses and shorter sentences. Focus on clarity and authenticity, rehearsing your content with a good introduction and a persuasive central idea. Employ rhetorical devices and a conversational tone, ensuring the right vocabulary and grammar.

How Can Speech Writing Improve Your Public Speaking Skills?

Enhancing your public speaking skills is possible through speech writing. By emphasizing key points and a clear thesis, you can capture the audience’s attention. Developing a strong start and central idea helps deliver effective speeches. Utilize speechwriting techniques and rhetorical devices to structure engaging speeches that connect with the audience. Focus on authenticity, empathy, and a conversational tone to improve your public speaking skills.

In conclusion, speech writing is an art that requires careful consideration of various elements such as clarity, audience analysis, and engagement. By understanding the importance of speech writing and the role of a speech writer, you can craft effective speeches that leave a lasting impact on your audience. Remember to start with a compelling opener, develop a strong body, and end with a memorable conclusion. Engaging techniques, simplicity, and nonverbal communication are key to keeping your audience captivated. Additionally, analyzing your audience demographics and considering time and length considerations are vital for a successful speech. Lastly, practicing and rehearsing your speech will help improve your public speaking skills and ensure a confident delivery.

Expert Tips for Choosing Good Speech Topics

Master the art of how to start a speech.

Popular Posts

How to write a retirement speech that wows: essential guide.

June 4, 2022

The Best Op Ed Format and Op Ed Examples: Hook, Teach, Ask (Part 2)

June 2, 2022

Inspiring Awards Ceremony Speech Examples

November 21, 2023

Mastering the Art of How to Give a Toast

Short award acceptance speech examples: inspiring examples, best giving an award speech examples.

November 22, 2023

Sentence Sense Newsletter

The General Steps in the Speechwriting Process

- First Online: 15 March 2019

Cite this chapter

- Jens E. Kjeldsen 7 ,

- Amos Kiewe 8 ,

- Marie Lund 9 &

- Jette Barnholdt Hansen

Part of the book series: Rhetoric, Politics and Society ((RPS))

913 Accesses

In this chapter, we outline the general steps speechwriters ought to follow in the process of writing speeches for others. These guidelines are flexible and allow for comfortable adaptation given the varied implementation of speechwriting practices as well as the different approaches in the European and American systems. Our model follows the classical perspective that focuses on topic selection, the speaker-speechwriter negotiation of rhetorical constraints of context and audience as well as determining the fitting style and delivery. The chapter also develops a master rhetorical plan that can be used as a prompt or an outline for speechwriters when drafting a speech, covering the key variables of speech, situation, audience, and a suitable mode of communication.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Information Science and Media Studies, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway

Jens E. Kjeldsen

Department of Communication and Rhetorical Studies, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY, USA

School of Communication and Culture, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jens E. Kjeldsen .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Kjeldsen, J.E., Kiewe, A., Lund, M., Barnholdt Hansen, J. (2019). The General Steps in the Speechwriting Process. In: Speechwriting in Theory and Practice. Rhetoric, Politics and Society. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03685-0_13

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03685-0_13

Published : 15 March 2019

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-03684-3

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-03685-0

eBook Packages : Political Science and International Studies Political Science and International Studies (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

What this handout is about

This handout will help you create an effective speech by establishing the purpose of your speech and making it easily understandable. It will also help you to analyze your audience and keep the audience interested.

What’s different about a speech?

Writing for public speaking isn’t so different from other types of writing. You want to engage your audience’s attention, convey your ideas in a logical manner and use reliable evidence to support your point. But the conditions for public speaking favor some writing qualities over others. When you write a speech, your audience is made up of listeners. They have only one chance to comprehend the information as you read it, so your speech must be well-organized and easily understood. In addition, the content of the speech and your delivery must fit the audience.

What’s your purpose?

People have gathered to hear you speak on a specific issue, and they expect to get something out of it immediately. And you, the speaker, hope to have an immediate effect on your audience. The purpose of your speech is to get the response you want. Most speeches invite audiences to react in one of three ways: feeling, thinking, or acting. For example, eulogies encourage emotional response from the audience; college lectures stimulate listeners to think about a topic from a different perspective; protest speeches in the Pit recommend actions the audience can take.

As you establish your purpose, ask yourself these questions:

- What do you want the audience to learn or do?

- If you are making an argument, why do you want them to agree with you?

- If they already agree with you, why are you giving the speech?

- How can your audience benefit from what you have to say?

Audience analysis

If your purpose is to get a certain response from your audience, you must consider who they are (or who you’re pretending they are). If you can identify ways to connect with your listeners, you can make your speech interesting and useful.

As you think of ways to appeal to your audience, ask yourself:

- What do they have in common? Age? Interests? Ethnicity? Gender?

- Do they know as much about your topic as you, or will you be introducing them to new ideas?

- Why are these people listening to you? What are they looking for?

- What level of detail will be effective for them?

- What tone will be most effective in conveying your message?

- What might offend or alienate them?

For more help, see our handout on audience .

Creating an effective introduction

Get their attention, otherwise known as “the hook”.

Think about how you can relate to these listeners and get them to relate to you or your topic. Appealing to your audience on a personal level captures their attention and concern, increasing the chances of a successful speech. Speakers often begin with anecdotes to hook their audience’s attention. Other methods include presenting shocking statistics, asking direct questions of the audience, or enlisting audience participation.

Establish context and/or motive

Explain why your topic is important. Consider your purpose and how you came to speak to this audience. You may also want to connect the material to related or larger issues as well, especially those that may be important to your audience.

Get to the point

Tell your listeners your thesis right away and explain how you will support it. Don’t spend as much time developing your introductory paragraph and leading up to the thesis statement as you would in a research paper for a course. Moving from the intro into the body of the speech quickly will help keep your audience interested. You may be tempted to create suspense by keeping the audience guessing about your thesis until the end, then springing the implications of your discussion on them. But if you do so, they will most likely become bored or confused.

For more help, see our handout on introductions .

Making your speech easy to understand

Repeat crucial points and buzzwords.

Especially in longer speeches, it’s a good idea to keep reminding your audience of the main points you’ve made. For example, you could link an earlier main point or key term as you transition into or wrap up a new point. You could also address the relationship between earlier points and new points through discussion within a body paragraph. Using buzzwords or key terms throughout your paper is also a good idea. If your thesis says you’re going to expose unethical behavior of medical insurance companies, make sure the use of “ethics” recurs instead of switching to “immoral” or simply “wrong.” Repetition of key terms makes it easier for your audience to take in and connect information.

Incorporate previews and summaries into the speech

For example:

“I’m here today to talk to you about three issues that threaten our educational system: First, … Second, … Third,”

“I’ve talked to you today about such and such.”

These kinds of verbal cues permit the people in the audience to put together the pieces of your speech without thinking too hard, so they can spend more time paying attention to its content.

Use especially strong transitions

This will help your listeners see how new information relates to what they’ve heard so far. If you set up a counterargument in one paragraph so you can demolish it in the next, begin the demolition by saying something like,

“But this argument makes no sense when you consider that . . . .”

If you’re providing additional information to support your main point, you could say,

“Another fact that supports my main point is . . . .”

Helping your audience listen

Rely on shorter, simpler sentence structures.

Don’t get too complicated when you’re asking an audience to remember everything you say. Avoid using too many subordinate clauses, and place subjects and verbs close together.

Too complicated:

The product, which was invented in 1908 by Orville Z. McGillicuddy in Des Moines, Iowa, and which was on store shelves approximately one year later, still sells well.

Easier to understand:

Orville Z. McGillicuddy invented the product in 1908 and introduced it into stores shortly afterward. Almost a century later, the product still sells well.

Limit pronoun use

Listeners may have a hard time remembering or figuring out what “it,” “they,” or “this” refers to. Be specific by using a key noun instead of unclear pronouns.

Pronoun problem:

The U.S. government has failed to protect us from the scourge of so-called reality television, which exploits sex, violence, and petty conflict, and calls it human nature. This cannot continue.

Why the last sentence is unclear: “This” what? The government’s failure? Reality TV? Human nature?

More specific:

The U.S. government has failed to protect us from the scourge of so-called reality television, which exploits sex, violence, and petty conflict, and calls it human nature. This failure cannot continue.

Keeping audience interest

Incorporate the rhetorical strategies of ethos, pathos, and logos.

When arguing a point, using ethos, pathos, and logos can help convince your audience to believe you and make your argument stronger. Ethos refers to an appeal to your audience by establishing your authenticity and trustworthiness as a speaker. If you employ pathos, you appeal to your audience’s emotions. Using logos includes the support of hard facts, statistics, and logical argumentation. The most effective speeches usually present a combination these rhetorical strategies.

Use statistics and quotations sparingly

Include only the most striking factual material to support your perspective, things that would likely stick in the listeners’ minds long after you’ve finished speaking. Otherwise, you run the risk of overwhelming your listeners with too much information.

Watch your tone

Be careful not to talk over the heads of your audience. On the other hand, don’t be condescending either. And as for grabbing their attention, yelling, cursing, using inappropriate humor, or brandishing a potentially offensive prop (say, autopsy photos) will only make the audience tune you out.

Creating an effective conclusion

Restate your main points, but don’t repeat them.

“I asked earlier why we should care about the rain forest. Now I hope it’s clear that . . .” “Remember how Mrs. Smith couldn’t afford her prescriptions? Under our plan, . . .”

Call to action

Speeches often close with an appeal to the audience to take action based on their new knowledge or understanding. If you do this, be sure the action you recommend is specific and realistic. For example, although your audience may not be able to affect foreign policy directly, they can vote or work for candidates whose foreign policy views they support. Relating the purpose of your speech to their lives not only creates a connection with your audience, but also reiterates the importance of your topic to them in particular or “the bigger picture.”

Practicing for effective presentation

Once you’ve completed a draft, read your speech to a friend or in front of a mirror. When you’ve finished reading, ask the following questions:

- Which pieces of information are clearest?

- Where did I connect with the audience?

- Where might listeners lose the thread of my argument or description?

- Where might listeners become bored?

- Where did I have trouble speaking clearly and/or emphatically?

- Did I stay within my time limit?

Other resources

- Toastmasters International is a nonprofit group that provides communication and leadership training.

- Allyn & Bacon Publishing’s Essence of Public Speaking Series is an extensive treatment of speech writing and delivery, including books on using humor, motivating your audience, word choice and presentation.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Boone, Louis E., David L. Kurtz, and Judy R. Block. 1997. Contemporary Business Communication . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Ehrlich, Henry. 1994. Writing Effective Speeches . New York: Marlowe.

Lamb, Sandra E. 1998. How to Write It: A Complete Guide to Everything You’ll Ever Write . Berkeley: Ten Speed Press.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Get in touch with us – here

- About Ginger

- About Leadership

- All programmes and courses

- Purpose-Driven Leadership

- Storytelling Mastery

- 1-2-1 training/coaching

- Elevate your Influence

- Executive Presence

- Present with Influence

- Public Speaking Foundations

- Assertive Communications

- Boosting Visibility and Confidence

- Building Your Personal Brand

- Clear & Concise Communications

- Courageous Communications

- Fearless Feedback

- High-Impact Communications

- Messages that Stand Out From the Crowd

- The Essentials of Storytelling for Business

- Virtually Brilliant for Online Communicators

- hello@gingerleadershipcomms.com

- +44 (0) 207 3888 645

Speech Writing: How to write a speech in 5 steps

Every great speech starts with an idea, be it for school or work or a TED talk about your area of speciality. We investigate how to get all those ideas from your head to a written speech and then back to your heart. Author of “ How to be Brilliant at Public Speaking “, Sarah Lloyd-Hughes explains the five steps of speech writing…

Even heads of state and other renowned orators have help in writing a speech. They often have professional speech writers to provide them with great content, but you too can learn not only how to talk but also how to write a speech like a pro.

Here are 5 steps that we take our speakers through when they’re writing a speech – and it’s the same process as we use for writing TED style talks.

Speech writing step 1: Get focused

TED talks famously focus on ‘one idea worth spreading’ and this is what helps them to retain their power. Before you write a single line, figure out what the ONE idea is that you’ll shape your talk around.

When your talk has a single focus you’ll see huge benefits:

- Clarity: For yourself and your audience.

- Easy to pass on: Popular talks, like Simon Sinek’s TED talk ‘ How great leaders inspire action ‘ or Ken Robinson’s TED favourite ‘ Do schools kill creativity? ‘ are utterly focused and easy to pass on because they have just one idea.

- Powerful: When you’re digging in one hole you get deeper, likewise with your talk you can go further with one idea.

- Memorability: Audiences these days are overwhelmed with ideas and information. You need to be much simpler than you think to stand a chance of your message being remembered.

To find your ‘idea worth spreading’ takes a little time and skill, which is why we’ve devised a complete programme for speakers who are interested in writing World Class Speeches , like the finest TED speakers.

But if you’re just looking for a place to start, these questions will help you get going:

- What do I want to say?

- What effect am I trying to have by speaking?

- If I can only put across one message in my speech, what will that be?

- What is my broader purpose in speaking?

You’re looking for one idea that is clear, interesting and hasn’t been heard before. Good luck!

Speech writing step 2: Think about your audience

Ironically, most speakers completely fail to think about their audience! Yet the best speakers are intimately aware of the needs, questions and doubts facing their audience.

Ask: To whom am I speaking? Before you start writing you first must ask yourself Who is my audience and what are they seeking ? Writing a speech for a group of human rights activists would be very different to a speech for business managers. Technology engineers might have a totally different perspective on your subject than a room full of English professors. Thinking deeply about your audience’s needs is the quality of a public speaker I call Empathy. It’s an important starting point on your speech writing journey.

Ask: Why should they listen to you? Great speech writing is grounded in purpose and message. Consider what qualifies you to speak; what you have to offer the audience that they would not be able to hear from anyone else (we all have something).

Ask: What do you want to leave your audience with? As a result of your Empathetic investigations, what would be your desired outcome as a result of the speech? Decide what your main message will be and continually return to that primary point as you compose your speech. This keeps the audience (and you) focused. As Winston Churchill said: “If you have an important point to make, don’t try to be subtle or clever. Use a pile driver. Hit the point once. Then come back and hit it again. Then hit it a third time with a tremendous whack. ”

Speech writing step 3: Build up your speech

Now you have a clear focus to your speech and an idea of how to communicate that clearly to your audience. That’s the skeleton of the speech. It’s now time to fill in that skeleton with meaty content:

- Brain Storming. Make lists of all the things you want to speak about. Once listed, it will be easier to cut or rearrange your points.

- Categorize for the win. Brainstorming should lead to a nice list with several categories. Speech writing is all about organization and finding what fits best with your audience and their needs. Think of these categories as stepping stones. Leaving a gap too large between any two stones and they will turn into stumbling blocks will sinking you and your audience. Speech writing is not very much different than writing a paper; thesis statement, support of the thesis, and a conclusion.

- Edit for the jewels . Look for the key moments in your speech that will stimulate the hearts, minds and even stomachs of your audience. Seek the most vivid experiences and stories that you can use to make your point – these are what will make your speech stand out from all the other public speaking our there.

Speech writing step 4: Create a journey

Another key skill of speech writing is to get the right information in the right order. Think of your speech like a journey up a mountain:

Get ready for the trip (introduction).

- The beginning of your speech is the place where you grab the attention of the audience and get them ready to go on a journey with you. For them to travel up your mountain with you they need to know where you’re going together, why it’s an interesting journey to go on and why you are a credible guide to lead them there.

Pass some interesting sights on the way (main body).

- Keep an audience engaged for an entire speech by raising the stakes, or raising the tension as you progress through the speech. Think about contrasts between the ‘good’ and the ‘evil’ of your subject matter and contrast the two with stories, facts, ideas or examples.

- Here you might write multiple sections to your speech, to help you stay focused. You might like to write an introduction, main body, and conclusion for each section also. All sections don’t have to be the same length. Take time to decide and write about the ones that need the most emphasis.

Reach your summit (climax).

- The climax is the moment of maximum emotional intensity that most powerfully demonstrates your key message. Think of the key ‘Ahah!’ moment that you want to take your audience to. This is the moment where you reach the top of your mountain and marvel at the view together. It’s a powerful, but underused speech writing tool.

A speedy descent (the close).

- Once you’ve hit your climax, the story is almost over. We don’t want to go all the way down the mountain with you, we’d much rather get airlifted off the top of the mountain whilst we still have the buzz of reaching our goal. This is what great speech writing manages time and again.

- Strangely enough the close can be the hardest part of speech writing. Here’s where you get to hit home your action point – the key thing you want your audience to do differently as a result of listening to your speech. Often the close is where speakers undermine the power of the rest of their speech. So, write a memorable conclusion that captures the essence of your speech, give it some punch, and stick to it!

Speech writing step 5: Test your material

Practice your speech several times so that you can feel comfortable with the material. Try the speech out on camera or to a friend to see which parts are most powerful and which you can take the red pen to.

However skilled you are (or not) at speech writing, remember that you are the magic that makes the speech work. It’s your authentic voice that will shine to the audience them and inspire them towards your message.

Follow these speech writing tips, give it some practice and you’ll be sure to be a speech writing winner.

But I’ve collected my years of experience working with world-class conference speakers and TED speakers and distilled it into a simple guidebook that you can access now for just £20 (+VAT) .

Ginger Leadership Communications

This showcase of inspiring female speakers is part of Ginger’s work with game changing leaders.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

3.6: The Speech Communication Process

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 82730

Most who study the speech communication process agree that there are several critical components present in nearly every speech. We have chosen in this text to label these components using the following terms:

- Listener(s)

Interference

As you might imagine, the speaker is the crucial first element within the speech communication process. Without a speaker, there is no process. The speaker is simply the person who is delivering, or presenting, the speech. A speaker might be someone who is training employees in your workplace. Your professor is another example of a public speaker as s/he gives a lecture. Even a stand-up comedian can be considered a public speaker. After all, each of these people is presenting an oral message to an audience in a public setting. Most speakers, however, would agree that the listener is one of the primary reasons that they speak.

The listener is just as important as the speaker; neither one is effective without the other. The listener is the person or persons who have assembled to hear the oral message. Some texts might even call several listeners an “audience. ” The listener generally forms an opinion as to the effectiveness of the speaker and the validity of the speaker’s message based on what they see and hear during the presentation. The listener’s job sometimes includes critiquing, or evaluating, the speaker’s style and message. You might be asked to critique your classmates as they speak or to complete an evaluation of a public speaker in another setting. That makes the job of the listener extremely important. Providing constructive feedback to speakers often helps the speaker improve her/his speech tremendously.

Another crucial element in the speech process is the message. The message is what the speaker is discussing or the ideas that s/he is presenting to you as s/he covers a particular topic. The important chapter concepts presented by your professor become the message during a lecture. The commands and steps you need to use, the new software at work, are the message of the trainer as s/he presents the information to your department. The message might be lengthy, such as the President’s State of the Union address, or fairly brief, as in a five-minute presentation given in class.

The channel is the means by which the message is sent or transmitted. Different channels are used to deliver the message, depending on the communication type or context. For instance, in mass communication, the channel utilized might be a television or radio broadcast. The use of a cell phone is an example of a channel that you might use to send a friend a message in interpersonal communication. However, the channel typically used within public speaking is the speaker’s voice, or more specifically, the sound waves used to carry the voice to those listening. You could watch a prerecorded speech or one accessible on YouTube, and you might now say the channel is the television or your computer. This is partially true. However, the speech would still have no value if the speaker’s voice was not present, so in reality, the channel is now a combination of the two -the speaker’s voice broadcast through an electronic source.

The context is a bit more complicated than the other elements we have discussed so far. The context is more than one specific component. For example, when you give a speech in your classroom, the classroom, or the physical location of your speech, is part of the context . That’s probably the easiest part of context to grasp.

But you should also consider that the people in your audience expect you to behave in a certain manner, depending on the physical location or the occasion of the presentation . If you gave a toast at a wedding, the audience wouldn’t be surprised if you told a funny story about the couple or used informal gestures such as a high-five or a slap on the groom’s back. That would be acceptable within the expectations of your audience, given the occasion. However, what if the reason for your speech was the presentation of a eulogy at a loved one’s funeral? Would the audience still find a high-five or humor as acceptable in that setting? Probably not. So the expectations of your audience must be factored into context as well.

The cultural rules -often unwritten and sometimes never formally communicated to us -are also a part of the context. Depending on your culture, you would probably agree that there are some “rules ” typically adhered to by those attending a funeral. In some cultures, mourners wear dark colors and are somber and quiet. In other cultures, grieving out loud or beating one’s chest to show extreme grief is traditional. Therefore, the rules from our culture -no matter what they are -play a part in the context as well.

Every speaker hopes that her/his speech is clearly understood by the audience. However, there are times when some obstacle gets in the way of the message and interferes with the listener’s ability to hear what’s being said. This is interference , or you might have heard it referred to as “noise. ” Every speaker must prepare and present with the assumption that interference is likely to be present in the speaking environment.

Interference can be mental, physical, or physiological. Mental interference occurs when the listener is not fully focused on what s/he is hearing due to her/his own thoughts. If you’ve ever caught yourself daydreaming in class during a lecture, you’re experiencing mental interference. Your own thoughts are getting in the way of the message.

A second form of interference is physical interference . This is noise in the literal sense -someone coughing behind you during a speech or the sound of a mower outside the classroom window. You may be unable to hear the speaker because of the surrounding environmental noises.

The last form of interference is physiological . This type of interference occurs when your body is responsible for the blocked signals. A deaf person, for example, has the truest form of physiological interference; s/he may have varying degrees of difficulty hearing the message. If you’ve ever been in a room that was too cold or too hot and found yourself not paying attention, you’re experiencing physiological interference. Your bodily discomfort distracts from what is happening around you.

The final component within the speech process is feedback. While some might assume that the speaker is the only one who sends a message during a speech, the reality is that the listeners in the audience are sending a message of their own, called feedback . Often this is how the speaker knows if s/he is sending an effective message. Occasionally the feedback from listeners comes in verbal form – questions from the audience or an angry response from a listener about a key point presented. However, in general, feedback during a presentation is typically non-verbal -a student nodding her/his head in agreement or a confused look from an audience member. An observant speaker will scan the audience for these forms of feedback, but keep in mind that non-verbal feedback is often more difficult to spot and to decipher. For example, is a yawn a sign of boredom, or is it simply a tired audience member?

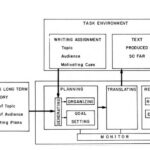

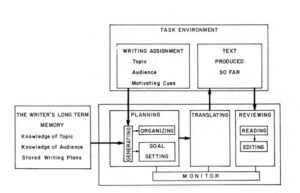

Generally, all of the above elements are present during a speech. However, you might wonder what the process would look like if we used a diagram to illustrate it. Initially, some students think of public speaking as a linear process -the speaker sending a message to the listener -a simple, straight line. But if you’ll think about the components we’ve just covered, you begin to see that a straight line cannot adequately represent the process, when we add listener feedback into the process. The listener is sending her/his own message back to the speaker, so perhaps the process might better be represented as circular. Add in some interference and place the example in context, and you have a more complete idea of the speech process.

- Provided by : Florida State College at Jacksonville. License : CC BY: Attribution

Speechwriting 101: Writing an Effective Speech

Whether you are a communications pro or a human resources executive, the time will come when you will need to write a speech for yourself or someone else. when that time comes, your career may depend on your success..

J. Lyman MacInnis, a corporate coach, Toronto Star columnist, accounting executive and author of “ The Elements of Great Public Speaking ,” has seen careers stalled – even damaged – by a failure to communicate messages effectively before groups of people. On the flip side, solid speechwriting skills can help launch and sustain a successful career. What you need are forethought and methodical preparation.

Know Your Audience

Learn as much as possible about the audience and the event. This will help you target the insights, experience or knowledge you have that this group wants or needs:

- Why has the audience been brought together?

- What do the members of the audience have in common?

- How big an audience will it be?

- What do they know, and what do they need to know?

- Do they expect discussion about a specific subject and, if so, what?

- What is the audience’s attitude and knowledge about the subject of your talk?

- What is their attitude toward you as the speaker?

- Why are they interested in your topic?

Choose Your Core Message

If the core message is on target, you can do other things wrong. But if the message is wrong, it doesn’t matter what you put around it. To write the most effective speech, you should have significant knowledge about your topic, sincerely care about it and be eager to talk about it. Focus on a message that is relevant to the target audience, and remember: an audience wants opinion. If you offer too little substance, your audience will label you a lightweight. If you offer too many ideas, you make it difficult for them to know what’s important to you.

Research and Organize

Research until you drop. This is where you pick up the information, connect the ideas and arrive at the insights that make your talk fresh. You’ll have an easier time if you gather far more information than you need. Arrange your research and notes into general categories and leave space between them. Then go back and rearrange. Fit related pieces together like a puzzle.

Develop Structure to Deliver Your Message

First, consider whether your goal is to inform, persuade, motivate or entertain. Then outline your speech and fill in the details:

- Introduction – The early minutes of a talk are important to establish your credibility and likeability. Personal anecdotes often work well to get things started. This is also where you’ll outline your main points.

- Body – Get to the issues you’re there to address, limiting them to five points at most. Then bolster those few points with illustrations, evidence and anecdotes. Be passionate: your conviction can be as persuasive as the appeal of your ideas.

- Conclusion – Wrap up with feeling as well as fact. End with something upbeat that will inspire your listeners.

You want to leave the audience exhilarated, not drained. In our fast-paced age, 20-25 minutes is about as long as anyone will listen attentively to a speech. As you write and edit your speech, the general rule is to allow about 90 seconds for every double-spaced page of copy.

Spice it Up

Once you have the basic structure of your speech, it’s time to add variety and interest. Giving an audience exactly what it expects is like passing out sleeping pills. Remember that a speech is more like conversation than formal writing. Its phrasing is loose – but without the extremes of slang, the incomplete thoughts, the interruptions that flavor everyday speech.

- Give it rhythm. A good speech has pacing.

- Vary the sentence structure. Use short sentences. Use occasional long ones to keep the audience alert. Fragments are fine if used sparingly and for emphasis.

- Use the active voice and avoid passive sentences. Active forms of speech make your sentences more powerful.

- Repeat key words and points. Besides helping your audience remember something, repetition builds greater awareness of central points or the main theme.

- Ask rhetorical questions in a way that attracts your listeners’ attention.

- Personal experiences and anecdotes help bolster your points and help you connect with the audience.

- Use quotes. Good quotes work on several levels, forcing the audience to think. Make sure quotes are clearly attributed and said by someone your audience will probably recognize.

Be sure to use all of these devices sparingly in your speeches. If overused, the speech becomes exaggerated. Used with care, they will work well to move the speech along and help you deliver your message in an interesting, compelling way.

More News & Resources

Measuring and Communicating the Value of Public Affairs

July 26, 2023

Benchmarking Reports Reveal Public Affairs’ Growing Status

November 16, 2023

Volunteer of the Year Was Integral to New Fellowship

Is the Fight for the Senate Over?

New Council Chair Embraces Challenge of Changing Profession

October 25, 2023

Are We About to Have a Foreign Policy Election?

Few Americans Believe 2024 Elections Will Be ‘Honest and Open’

Rural Americans vs. Urban Americans

August 3, 2023

What Can We Learn from DeSantis-Disney Grudge Match?

June 29, 2023

Laura Brigandi Manager of Digital and Advocacy Practice 202.787.5976 | [email protected]

Featured Event

Digital media & advocacy summit.

The leading annual event for digital comms and advocacy professionals. Hear new strategies, and case studies for energizing grassroots and policy campaigns.

Washington, D.C. | June 10, 2024

Previous Post Hiring Effectively With an Executive Recruiter

Next post guidance on social media policies for external audiences.

Comments are closed.

Public Affairs Council 2121 K St. N.W., Suite 900 Washington, DC 20037 (+1) 202.787.5950 [email protected]

European Office

Public Affairs Council Square Ambiorix 7 1000 Brussels [email protected]

Contact Who We Are

Stay Connected

LinkedIn X (Twitter) Instagram Facebook Mailing List

Read our Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | COPYRIGHT 2024 PUBLIC AFFAIRS COUNCIL

- Browse All Content

- Upcoming Events

- On-Demand Recordings

- Team Training with ‘Membership Plus+’

- Earn Your Certificate

- Sponsorship Opportunities

- Content Search

- Connect with Our Experts

- PAC & Political Engagement

- Grassroots & Digital Advocacy

- Communications

- Social Impact

- Government Relations

- Public Affairs Management

- Browse Research

- Legal Guidance

- Election Insights

- Benchmarking, Consulting & Training

- Where to Start

- Latest News

- Impact Monthly Newsletter

- Member Spotlight

- Membership Directory

- Recognition

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 1: The Speech Communication Process

The Speech Communication Process

- Listener(s)

Interference

As you might imagine, the speaker is the crucial first element within the speech communication process. Without a speaker, there is no process. The speaker is simply the person who is delivering, or presenting, the speech. A speaker might be someone who is training employees in your workplace. Your professor is another example of a public speaker as s/he gives a lecture. Even a stand-up comedian can be considered a public speaker. After all, each of these people is presenting an oral message to an audience in a public setting. Most speakers, however, would agree that the listener is one of the primary reasons that they speak.

The listener is just as important as the speaker; neither one is effective without the other. The listener is the person or persons who have assembled to hear the oral message. Some texts might even call several listeners an “audience. ” The listener generally forms an opinion as to the effectiveness of the speaker and the validity of the speaker’s message based on what they see and hear during the presentation. The listener’s job sometimes includes critiquing, or evaluating, the speaker’s style and message. You might be asked to critique your classmates as they speak or to complete an evaluation of a public speaker in another setting. That makes the job of the listener extremely important. Providing constructive feedback to speakers often helps the speaker improve her/his speech tremendously.

Another crucial element in the speech process is the message. The message is what the speaker is discussing or the ideas that s/he is presenting to you as s/he covers a particular topic. The important chapter concepts presented by your professor become the message during a lecture. The commands and steps you need to use, the new software at work, are the message of the trainer as s/he presents the information to your department. The message might be lengthy, such as the President’s State of the Union address, or fairly brief, as in a five-minute presentation given in class.

The channel is the means by which the message is sent or transmitted. Different channels are used to deliver the message, depending on the communication type or context. For instance, in mass communication, the channel utilized might be a television or radio broadcast. The use of a cell phone is an example of a channel that you might use to send a friend a message in interpersonal communication. However, the channel typically used within public speaking is the speaker’s voice, or more specifically, the sound waves used to carry the voice to those listening. You could watch a prerecorded speech or one accessible on YouTube, and you might now say the channel is the television or your computer. This is partially true. However, the speech would still have no value if the speaker’s voice was not present, so in reality, the channel is now a combination of the two -the speaker’s voice broadcast through an electronic source.

The context is a bit more complicated than the other elements we have discussed so far. The context is more than one specific component. For example, when you give a speech in your classroom, the classroom, or the physical location of your speech, is part of the context . That’s probably the easiest part of context to grasp.

But you should also consider that the people in your audience expect you to behave in a certain manner, depending on the physical location or the occasion of the presentation . If you gave a toast at a wedding, the audience wouldn’t be surprised if you told a funny story about the couple or used informal gestures such as a high-five or a slap on the groom’s back. That would be acceptable within the expectations of your audience, given the occasion. However, what if the reason for your speech was the presentation of a eulogy at a loved one’s funeral? Would the audience still find a high-five or humor as acceptable in that setting? Probably not. So the expectations of your audience must be factored into context as well.

The cultural rules -often unwritten and sometimes never formally communicated to us -are also a part of the context. Depending on your culture, you would probably agree that there are some “rules ” typically adhered to by those attending a funeral. In some cultures, mourners wear dark colors and are somber and quiet. In other cultures, grieving out loud or beating one’s chest to show extreme grief is traditional. Therefore, the rules from our culture -no matter what they are -play a part in the context as well.

Every speaker hopes that her/his speech is clearly understood by the audience. However, there are times when some obstacle gets in the way of the message and interferes with the listener’s ability to hear what’s being said. This is interference , or you might have heard it referred to as “noise. ” Every speaker must prepare and present with the assumption that interference is likely to be present in the speaking environment.

Interference can be mental, physical, or physiological. Mental interference occurs when the listener is not fully focused on what s/he is hearing due to her/his own thoughts. If you’ve ever caught yourself daydreaming in class during a lecture, you’re experiencing mental interference. Your own thoughts are getting in the way of the message.

A second form of interference is physical interference . This is noise in the literal sense -someone coughing behind you during a speech or the sound of a mower outside the classroom window. You may be unable to hear the speaker because of the surrounding environmental noises.

The last form of interference is physiological . This type of interference occurs when your body is responsible for the blocked signals. A deaf person, for example, has the truest form of physiological interference; s/he may have varying degrees of difficulty hearing the message. If you’ve ever been in a room that was too cold or too hot and found yourself not paying attention, you’re experiencing physiological interference. Your bodily discomfort distracts from what is happening around you.

The final component within the speech process is feedback. While some might assume that the speaker is the only one who sends a message during a speech, the reality is that the listeners in the audience are sending a message of their own, called feedback . Often this is how the speaker knows if s/he is sending an effective message. Occasionally the feedback from listeners comes in verbal form – questions from the audience or an angry response from a listener about a key point presented. However, in general, feedback during a presentation is typically non-verbal -a student nodding her/his head in agreement or a confused look from an audience member. An observant speaker will scan the audience for these forms of feedback, but keep in mind that non-verbal feedback is often more difficult to spot and to decipher. For example, is a yawn a sign of boredom, or is it simply a tired audience member?

Generally, all of the above elements are present during a speech. However, you might wonder what the process would look like if we used a diagram to illustrate it. Initially, some students think of public speaking as a linear process -the speaker sending a message to the listener -a simple, straight line. But if you’ll think about the components we’ve just covered, you begin to see that a straight line cannot adequately represent the process, when we add listener feedback into the process. The listener is sending her/his own message back to the speaker, so perhaps the process might better be represented as circular. Add in some interference and place the example in context, and you have a more complete idea of the speech process.

Fundamentals of Public Speaking Copyright © by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

SemiOffice.Com

Your Office Partner

The Definition of Speech and the Writing Process

Speech and writing are two fundamental forms of communication that humans employ to express their thoughts, ideas, and emotions. While speech involves the oral delivery of language, writing involves the graphical representation of language. Both speech and writing play crucial roles in our daily lives, enabling us to communicate, share information, and preserve knowledge. This article aims to define speech and explore the process of writing, shedding light on their similarities and differences.

I. Definition of Speech: Speech refers to the oral expression of language, utilizing sounds, words, and gestures to convey meaning. It is an innate human ability, developed through language acquisition during childhood. Speech involves the coordination of various systems, such as the respiratory, phonatory, and articulatory systems. It allows for real-time interaction and immediate feedback, facilitating spontaneous communication. Speech can take various forms, including formal presentations, conversations, debates, lectures, and more.

II. The Writing Process: The writing process encompasses the steps involved in transforming thoughts and ideas into written form. It is a complex cognitive and linguistic activity that requires planning, organizing, drafting, revising, and editing. The writing process typically involves the following stages:

- Pre-Writing: During this stage, the writer generates ideas, explores the topic, and conducts research. They may brainstorm, create outlines, and gather relevant information to establish a clear understanding of the subject matter.

- Drafting: In the drafting stage, the writer begins to put their ideas into written form. They develop a structure, write sentences and paragraphs, and establish the overall flow of the piece. The focus is on generating content without worrying too much about grammar, punctuation, or style.

- Revising: During revision, the writer reviews the initial draft, considering aspects such as clarity, coherence, and effectiveness of communication. They make changes to improve the overall quality of the writing, rearranging sentences, adding or deleting information, and refining the language.

- Editing: In the editing stage, the writer pays attention to grammar, punctuation, spelling, and style. They carefully proofread the document, ensuring correctness and consistency. Editing involves correcting errors, enhancing sentence structure, and refining the overall language usage.

- Publishing: The final stage involves preparing the written piece for its intended audience. Formatting, citation, and referencing are finalized. The work may be shared through various mediums, such as print, digital platforms, or presentations.

III. Similarities and Differences: Both speech and writing share the common goal of communication, allowing individuals to convey messages and express ideas. However, there are significant differences between the two:

- Temporal Aspect: Speech is often spontaneous and immediate, allowing for real-time interaction and feedback. Writing, on the other hand, is a more deliberate and time-consuming process, enabling writers to carefully construct their message.

- Mode of Delivery: Speech relies on oral and auditory channels, employing tone, pitch, volume, and gestures to convey meaning. Writing, on the contrary, uses the graphical representation of language through symbols, such as letters, numbers, and punctuation marks.

- Permanence and Preservation: Speech is transient in nature, leaving minimal room for revision or preservation. Writing, however, allows for editing, revising, and archiving, ensuring longevity and accessibility of information.

Conclusion: Speech and writing are two distinct yet interconnected forms of communication. While speech allows for spontaneous interaction, writing provides a more deliberate and structured means of expression. Understanding the definition of speech and the writing process enhances our ability to effectively communicate and share ideas, contributing to the development and exchange of knowledge in various spheres of life.

Share this:

Author: david beckham.

I am a content creator and entrepreneur. I am a university graduate with a business degree, and I started writing content for students first and later for working professionals. Now we are adding a lot more content for businesses. We provide free content for our visitors, and your support is a smile for us. View all posts by David Beckham

Please Ask Questions? Cancel reply

25,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today

Here’s your new year gift, one app for all your, study abroad needs, start your journey, track your progress, grow with the community and so much more.

Verification Code

An OTP has been sent to your registered mobile no. Please verify

Thanks for your comment !

Our team will review it before it's shown to our readers.

Speech Writing

- Updated on

- Jan 16, 2024

The power of good, inspiring, motivating, and thought-provoking speeches can never be overlooked. If we retrospect, a good speech has not only won people’s hearts but also has been a verbal tool to conquer nations. For centuries, many leaders have used this instrument to charm audiences with their powerful speeches. Apart from vocalizing your speech perfectly, the words you choose in a speech carry immense weight, and practising speech writing begins with our school life. Speech writing is an important part of the English syllabus for Class 12th, Class 11th, and Class 8th to 10th. This blog brings you the Speech Writing format, samples, examples, tips, and tricks!

What is Speech Writing?

Must Read: Story Writing Format for Class 9 & 10

Speech writing is the art of using proper grammar and expression to convey a thought or message to a reader. Speech writing isn’t all that distinct from other types of narrative writing. However, students should be aware of certain distinct punctuation and writing style techniques. While writing the ideal speech might be challenging, sticking to the appropriate speech writing structure will ensure that you never fall short.

“There are three things to aim at in public speaking: first, to get into your subject, then to get your subject into yourself, and lastly, to get your subject into the heart of your audience.”- Alexander Gregg

Speech in English Language Writing