To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, online food delivery research: a systematic literature review.

International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management

ISSN : 0959-6119

Article publication date: 26 May 2022

Issue publication date: 26 July 2022

Online food delivery (OFD) has witnessed momentous consumer adoption in the past few years, and COVID-19, if anything, is only accelerating its growth. This paper captures numerous intricate issues arising from the complex relationship among the stakeholders because of the enhanced scale of the OFD business. The purpose of this paper is to highlight publication trends in OFD and identify potential future research themes.

Design/methodology/approach

The authors conducted a tri-method study – systematic literature review, bibliometric and thematic content analysis – of 43 articles on OFD published in 24 journals from 2015 to 2021 (March). The authors used VOSviewer to perform citation analysis.

Systematic literature review of the existing OFD research resulted in six potential research themes. Further, thematic content analysis synthesized and categorized the literature into four knowledge clusters, namely, (i) digital mediation in OFD, (ii) dynamic OFD operations, (iii) OFD adoption by consumers and (iv) risk and trust issues in OFD. The authors also present the emerging trends in terms of the most influential articles, authors and journals.

Practical implications

This paper captures the different facets of interactions among various OFD stakeholders and highlights the intricate issues and challenges that require immediate attention from researchers and practitioners.

Originality/value

This is one of the few studies to synthesize OFD literature that sheds light on unexplored aspects of complex relationships among OFD stakeholders through four clusters and six research themes through a conceptual framework.

- Online food delivery

- Sharing economy

- Systematic literature review

- Bibliometric analysis

- Content analysis

Acknowledgements

The authors thank three anonymous reviewers, the guest editor, and the editor-in-chief for their critical and valuable comments in developing the manuscript in stages.

Shroff, A. , Shah, B.J. and Gajjar, H. (2022), "Online food delivery research: a systematic literature review", International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management , Vol. 34 No. 8, pp. 2852-2883. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-10-2021-1273

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2022, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

- Scholarly Community Encyclopedia

- Log in/Sign up

Video Upload Options

- MDPI and ACS Style

- Chicago Style

In the midst of the global 2020 COVID-19 outbreak, the advantages of online food delivery (FD) were obvious as it facilitated consumer access to prepared meals and enabled food providers to keep operating. However, online FD is not without its critics, with reports of consumer and restaurant boycotts. It is therefore time to take stock and consider the broader impacts of online FD and what they mean for the stakeholders involved. Using the three pillars of sustainability as a lens through which to consider the impacts, this review presents the most up-to-date research in this field revealing a raft of positive and negative impacts. From an economic standpoint, online FD while providing job and sale opportunities has been criticized for high commissions it charges restaurants and questionable working conditions for delivery people. From a social perspective, online FD is affecting the relationship between consumers and their food as well as influencing public health outcomes and traffic systems. Environmental impacts include the generation of worrying amounts of waste and its high carbon footprints. Stakeholders must consider how best to mitigate the negative and promote the positive impacts of online FD to ensure that it is sustainable, in every sense, moving forward.

1. Definition

Online to offline (O2O) is a form of e-commerce in which consumers are attracted to a product or service online and induced to complete a transaction in an offline setting. An area of O2O commerce that is expanding rapidly is the use of online food delivery (online FD) platforms. All around the world, the rise of online FD has changed the way that many consumers and food suppliers interact, and the sustainability impacts (defined by the three pillars of economic, social and environmental [ 1 ] ) of this change has yet to be comprehensively assessed.

2. Introduction

Economic growth and increasing broadband penetration are driving the global expansion of e-commerce. Consumers are increasingly using online services as their disposable income increases, electronic payments become more trustworthy, and the range of suppliers and the size of their delivery networks expand.

3. Overview of the Online Food Delivery Sector

3.1. e-commerce market size.

The e-commerce market has experienced strong growth over the past decade, as customers increasingly move online. This shift in how consumers shop has been driven by a wide range of diverse factors, some being market or country dependent, others occurring as a result of worldwide changes. These changes include: an increase in disposal income, particularly in developing nations; longer work and commuting times; increased broadband penetration and improved safety of electronic payments; a relaxing of trade barriers; an increase in the number of retailers having an online presence; and a greater awareness of e-commerce by customers [ 2 ] .

The strongest growth of e-commerce over the last few years has occurred in China, where, in 2019, sales were worth US$ 1.935 trillion—an amount which was more than three times higher than that spent in the United States (US$ 586.92 billion), the second largest market. On its own, China represents 54.7% of the global e-commerce market, a share nearly twice the market share of the next five highest countries (US, UK, Japan, South Korea, Germany) combined [ 3 ] . The rise of e-commerce in the Asia-Pacific region is demonstrated in Table 1, which highlights the massive increase in the amount spent during key online shopping days between 2015 and 2019. Of particular note is the US$ 38.4 billion spent on Singles Day (11.11) in the Asia-Pacific region in 2019, an amount which is more than double the total sum of the US$9.4 billion spent on Black Friday in North America and much of Europe and the US$ 7.4 billion spent on Cyber Monday in North America. The leading e-commerce platforms worldwide differ by region and include platforms which are now household names, such as Amazon (U.S.), Alibaba (China), and Flipkart (India).

Table 1. Regional sales value of featured online shopping days from 2015–2019 [ 4 ] .

3.2. Online to Offline Business and Online FD

The rapid growth of e-commerce has spawned many new forms of business, such as B2B (business to business), C2C (customer to customer), B2C (business to customer), and O2O (online to offline) [ 5 ] [ 6 ] . The business of O2O is a marketing method based on information and communications technology (ICT) whereby consumers place orders for goods or services online and receive the goods or services at an offline outlet [ 7 ] [ 8 ] .

One of the significant developments driving the O2O commerce explosion has been the proliferation of smartphones and tablets and the development of infrastructures to support payment and delivery. In 2019 there were 5.2 billion smartphone connections, and by the end of 2020, it has been predicted that half of the people in the world will have access to mobile internet services [ 9 ] .

O2O services have emerged in various fields, including the purchase of diverse product and service categories, such as food, hotel rooms, real estate, or car rentals [ 10 ] . Online FD refers to the process whereby food that was ordered online is prepared and delivered to the consumer. The development of online FD has been underpinned by the development of integrated online FD platforms, such as Uber eats, Deliveroo, Swiggy, and Meituan. Online FD platforms serve a variety of functions including providing consumers with a wide variety of food choices, the taking of orders and the relaying of these order to the food producer, the monitoring of payment, the organization of the delivery of the food and the provision of tracking facilities (Figure 1) [ 11 ] . Food delivery applications, or ‘apps’, (FDA) function within the broader context of online FD as they enable the ordering of food through mobile apps [ 12 ] .

Figure 1. The functions associated with online food delivery (FD) platforms. Arrows indicate movement of information or logistic; lines indicate necessary routes; dotted lines indicate optional routes.

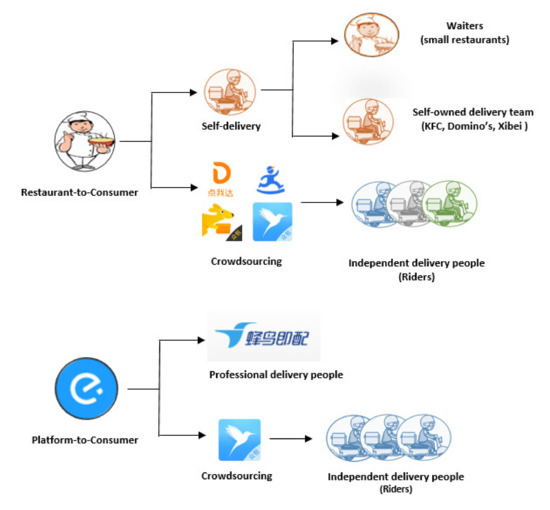

3.3. Online FD Providers and their Delivery System

Food delivery providers can be categorized as being either Restaurant-to-Consumer Delivery or Platform-to-Consumer Delivery operations [ 13 ] . Restaurant-to-Consumer Delivery providers make the food and deliver it, as typified by providers, such as KFC, McDonald’s, and Domino’s. The order can be made directly through the restaurant’s online platform or via a third-party platform. These third-party platforms vary from country to country, and include examples, such as Uber eats in the U.S., Eleme in China, Just Eat in UK, and Swiggy in India. Third-party platforms also provide online delivery services from partner restaurants which do not necessarily offer delivery services themselves, a process which is defined as Platform-to-Consumer Delivery.

Online FD requires highly efficient and scalable real-time delivery services. Restaurants can use existing staff for self-delivery, such as the use of waiters in some small restaurants or they may use specialized delivery teams who are specifically employed and trained for this role, as is seen with some of the big restaurant brands, such as KFC, Domino’s, and Xibei. Alternatively, restaurants can employ crowdsourcing logistics, a network of delivery people (riders) who are independent contractors, a model that provides an efficient, low-cost approach to food delivery [ 14 ] . Online FD platforms can either be responsible for recruiting and training professional delivery people, or they may also resort to crowdsourcing logistics, using delivery people who are not necessarily employed by the online FD platform. Professional delivery people are usually trained, and at least part of their salary is guaranteed, while a portion is commission-based. In contrast, the independent delivery people who are frequently known as “riders” are paid on a commission (per order) basis (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Online FD delivery retailers (Eleme in China, for example).

3.4. Growth of Online FD Worldwide

The rise of online FD is a global trend with many countries around the world having at least one major platform for food delivery (Table 2). China leads the way in market share for online FD, closely followed by the US with the developing markets of India and Brazil, showing rapid (> 9% compound annual growth rate (CAGR)) growth.

Table 2. Revenue of the Online FD segment in major countries [ 13 ] .

The online FD industry has been very proactive in the way it develops new markets and cultivates consumers’ eating habits. For example, in 2018, a promotion campaign by the India-based online FD company Foodpanda offered consumers large discounts, which resulted in Foodpanda increasing the number of users by a factor of 10 [ 15 ] . Moreover, in 2018, Eleme in China, spent three billion yuan (US$443 million) over three months in a successful marketing strategy to increase its market share to more than 50 percent of the Chinese market [ 16 ] . Despite online FD being very strong in some regions, as a whole across the world online FD is in the early stages of market development, and it will require considerable investment to fund promotions and campaigns and to provide subsidies to participating restaurants [ 17 ] [ 18 ] [ 19 ] [ 20 ] [ 21 ] . For example, a restaurant may hold a campaign on an FD platform, in which a consumer obtains ¥8 as a discount if the total amount ordered reaches ¥20. In fact, this discount may only cost the restaurant ¥2, as it will receive a ¥6 subsidy from the FD platform (the actual rules may vary from one platform to another [ 22 ] ). Such an approach is beneficial for a restaurant because it will attract more consumers and orders. It is crucial for the future of online FD to cultivate consumers’ eating habits by introducing them to the choosing and purchasing of food online. By providing consumers with the option of having a meal at a cheaper price or by providing other services, such as free delivery, online FD platforms and providers are encouraging consumers to abandon cooking at home or going out to a restaurant to eat.

Worldwide online FD is becoming increasingly well accepted and embraced by young adults, and nowhere is this trend more evident than in China. A survey in 2019 of 1000 university students in Nanjing, revealed that at least 71.45% of them had used online FD for at least two years and that 85.1% of them used online FD more than once a week [ 23 ] . Online FD has been reported to be popular with Chinese university students because it saves time (50.35% of 141 students in Hebei, China), is convenient (44.35% of 124 students in Jiangxi, China), and is able to provide options that were tastier (39.52% of 124 students) or simply different from canteen meals (36.17% of 141 students) [ 24 ] [ 25 ] . Of course, different populations around the world have different opportunities to purchase food online owing to cultural, technological and economic reasons and these differences can be responsible for the differing rates of uptake of online FD seen around the world. By way of comparison to China, for example, a 2019 survey of 252 Greek university students aged 18–23, reported that most of them cook at home and rarely eat out or have food delivery (45.6%), while others mostly eat at the student restaurant or cook at home (23.4%), with only 21% of the students surveyed stating that they had food delivered [ 26 ] .

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three pillars of sustainability: In search of conceptual origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695.

- Five reasons Why Ecommerce is Growing. Available online: https://archive.is/ndwF2. (accessed on 24 April 2020).

- Global Ecommerce 2019. Available online: https://archive.is/K2mWg (accessed on 14 April 2020).

- The 2020 Ecommerce Stats Report. Available online: https://archive.is/KHSoO (accessed on 14 April 2020).

- Ram, J.; Sun, S. Business benefits of online-to-offline ecommerce: A theory driven perspective. J. Innov. Econ. Manag. 2020, I77-XXVIII.

- Rani, N.S. E-commerce research, practices and applications. Stud. Indian Place Names 2020, 40, 773–780. [Google Scholar]

- Why Online2Offline Commerce is a Trillion Dollar Opportunity. Available online: https://archive.is/zEodV (accessed on 14 April 2020).

- Ji, S.W.; Sun, X.Y.; Liu, D. Research on core competitiveness of Chinese Retail Industry based on O2O. Adv. Mater. Res. 2014, 834–836, 2017–2020.

- The Mobile Economy 2020. Available online: https://archive.is/2Xhj1 (accessed on 14 April 2020).

- Roh, M.; Park, K. Adoption of O2O food delivery services in South Korea: The moderating role of moral obligation in meal preparation. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 47, 262–273.

- How Swiggy Works: Business model of India’s Largest Food Delivery Company. Available online: https://archive.is/JpNdK (accessed on 17 June 2020).

- Thamaraiselvan, N.; Jayadevan, G.R.; Chandrasekar, K.S. Digital food delivery apps revolutionizing food products marketing in India. Int. J. Recent Technol. Eng. 2019, 8, 662–665.

- Online Food Delivery. Available online: https://archive.is/e7OK5 (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Sun, P. Your order, their labor: An exploration of algorithms and laboring on food delivery platforms in China. Chin. J. Commun. 2019, 12, 308–323.

- Watch: Foodpanda’s Crave Party is Set to Be Its Biggest Food Experience Campaign. Available online: https://archive.is/F2uxR (accessed on 14 April 2020).

- Alibaba’s Ele.me Goes on 3 Billion Yuan Summer Spending Spree to Fight Competition. Available online: https://archive.is/woZLB (accessed on 14 April 2020).

- Pigatto, G.; Machado, J.G.C.F.; Negreti, A.D.S.; Machado, L.M. Have you chosen your request? Analysis of online food delivery companies in Brazil. Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 639–657.

- Meenakshi, N.; Sinha, A. Food delivery apps in India: Wherein lies the success strategy? Strat. Dir. 2019, 35, 12–15.

- Investors are Craving Food Delivery Companies. Available online: https://archive.is/B5aCA (accessed on 14 April 2020).

- Li, J. Research on food safety supervision on online Food Delivery industry. China Food Saf. Mag. 2019, 68–71.

- China’s Food Delivery King Feels the Heat from Alibaba. Available online: https://archive.is/9ENN1 (accessed on 14 April 2020).

- Investigation of Commission of Meituan: How Can Restaurants Become Tools for Platform Competition? Available online: https://archive.is/Q8AKn (accessed on 24 April 2020).

- Yin, Y.; Hu, J. The analysis of the advantages and disadvantages of the online food delivery phenomenon in universities and the research on the countermeasures—Based on the empirical study of Jiangpu campus of Nanjing university of technology and its surroundings. Pop. Stand. 2019, 16, 46–48.

- Li, F.; Zhang, J. Current consumption and problems of online food delivery of university students-A case study on students of Jiujiang college. J. Hubei Univ. Econ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 2018, 12, 40–42.

- Han, M.; Zhang, N.; Meng, X. Survey on consumption of online delivered food of college students. Co-Oper. Econ. Sci. 2017, 2, 92–93.

- Kamenidou, I.C.; Mamalis, S.A.; Pavlidis, S.; Bara, E.Z.G. Segmenting the Generation Z cohort university students based on sustainable food consumption behavior: A preliminary study. Sustainability (Basel) 2019, 11, 837.

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Advisory Board

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Factors affecting customer intention to use online food delivery services before and during the COVID-19 pandemic

With the emerging popularity of online food delivery (OFD) services, this research examined predictors affecting customer intention to use OFD services amid the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Specifically, Study 1 examined the moderating effect of the pandemic on the relationship between six predictors (perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, price saving benefit, time saving benefit, food safety risk perception, and trust) and OFD usage intention, and Study 2 extended the model by adding customer perceptions of COVID-19 (perceived severity and vulnerability) during the pandemic. Study 1 showed that all of the predictors except food safety risk perception significantly affected OFD usage intention, but no moderation effect of COVID-19 was found. In Study 2, while perceived severity and vulnerability had no significant impact on OFD usage intention, the altered effects of socio-demographic variables during the COVID-19 pandemic were found. Theoretical and managerial implications are provided.

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) a pandemic due to the high risk of fatality and human-to-human transmission on March 11, 2020 ( World Health Organization, 2020 ). Accordingly, the majority of U.S. states and their local ordinances issued stay-at-home or shelter-in-place orders and forced foodservice operations to be closed or restricted ( Restaurant Law Center, 2020 ). The official orders have had harsh effects on the restaurant industry, such as job losses and worst sales than other sectors (National Restaurant Association [ NRA], 2020a ). For example, by April 2020, more than 8 million employees working in the restaurant industry were furloughed, and consumption at restaurants/bars in April 2020 plummeted to the lowest level after October 1984 ( NRA, 2020b ).

As restaurants struggle to find ways to survive, online food delivery (OFD) services have recently gained high demands by delivering food and drinks to customers’ doorstep ( NPD, 2020 ). OFD services refer to internet-based food ordering and delivery systems that connect customers with partner restaurants via their websites or mobile applications ( Ray, Dhir, Bala, & Kaur, 2019 ). Although the OFD market had significantly grown before the pandemic, more customers have utilized OFD services during the COVID-19 pandemic, as evidenced by a report by the NPD Group, which revealed that the number of the OFD orders surged 67% in March 2020 compared to March 2019 ( NPD, 2020 ).

To date, several researchers have provided a fundamental understanding of OFD customers' decision-making process and their behavioral intentions including motivations to use OFD services ( Yeo, Goh, & Rezaei, 2017 ) and factors affecting OFD usages ( Ray, Dhir, Bala, & Kaur, 2019 ). However, it remains unclear whether the pandemic influences customers' substantial OFD purchasing behavior and decision-making process regarding OFD services. As the COVID-19 pandemic has had the most impact on recent human behavior changes ( Laato, Islam, Farooq, & Dhir, 2020 ), it is salient to consider the COVID-19 pandemic as a contextual factor affecting customers' OFD usages ( Kim, Kim, & Hwang, 2021 ). Furthermore, with several findings demonstrating that people who perceived health risks altered their actions in preventive ways ( Ali, Harris, & Ryu, 2019 ; Cahyanto et al., 2016 ), more customers might utilize OFD services to avoid human contact with restaurant employees and other customers during and even post COVID-19 pandemic. However, no research has considered the impact of customers’ perceptions about the health risk on customer intention to use OFD during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In light of this, this study explores factors affecting customer intention to use OFD services across two-time frames (before and during the COVID-19 pandemic) and investigates how customer perceptions on the COVID-19 pandemic alter their relationships through two studies. Specifically, Study 1 investigates the prominent predictors affecting customer intention to use OFD before and during the COVID-19 pandemic and examines the moderating effect of the COVID-19 outbreak between the relationships. To better understand the high demand for OFD services during the pandemic, Study 2 incorporates customers’ perceptions about the COVID-19 pandemic—perceived severity and perceived vulnerability—into the relationship between the predictors and customer intention to use OFD.

2. Literature review

2.1. study 1, 2.1.1. online food delivery services.

Online food delivery (OFD) refers to “the process whereby food that was ordered online is prepared and delivered to the consumer” ( Li et al., 2020 , p. 3). The proliferation of OFD services was supported by the development of integrated OFD platforms, such as Uber Eats, DoorDash, and Grubhub. When a customer places an order from various restaurant options through an OFD service platform on its mobile application or website and pays for the order, the restaurant receives the order and prepares the food. Then, a delivery driver delivers the order to the customer. Customers can track the status of their orders and contact their drivers via the app. OFD services offer various benefits to their customers including no waiting in line, no traveling for pick-up, no misunderstanding of the order which happen frequently in restaurants or phone call orders, and discounts from daily offers ( The Other Stream , n.d.).

The customer demand of OFD services has increased tremendously over the last few years and is expected to grow steadily. The total revenue of the global OFD service market was estimated at approximately $107.4 billion in 2019 and is expected to exceed $182.3 billion by 2024 ( Statista, 2020 ). Moreover, since the COVID-19 outbreak, the OFD market has gained even more attention globally due to its contactless ordering and delivery system and is expected to continue attracting new customers ( Maida, 2020 ).

Researchers have explored various factors affecting customer intention to use OFD (CIU) ( Cho, Bonn, & Li, 2019 ; Gunden et al., 2020 ; Suhartanto, Helmi Ali, Tan, Sjahroeddin, & Kusdibyo, 2019 ; Yeo, Goh, & Rezaei, 2017 ). For example, Gunden et al. (2020) found that performance expectancy and congruity with a self-image significantly affect customers’ adoption intention of OFD. Additionally, Cho, Bonn, & Li, 2019 identified system trust, convenience, design, and various food choices as significant predictors of customer intention to continuously use food delivery apps. Roh and Park (2019) also revealed that compatibility, ease of use, and usefulness were significant predictors of CIU, but Ray & Bala, 2021 presented price benefits, trust, and app-interaction enhanced CIU. Considering the inconsistent findings, the significant predictors affecting CIU are not clearly outlined. Given the peculiarities of ordering food and beverage online rather than going to restaurants and based on existing literature related to technology acceptance (i.e., Technology Acceptance Model) and OFD-related literature ( Cho, Bonn, & Li, 2019 ; Gunden et al., 2020 ; Ray & Bala, 2021 ; Ray, Dhir, Bala, & Kaur, 2019 ; Roh & Park, 2019 ; Suhartanto, Helmi Ali, Tan, Sjahroeddin, & Kusdibyo, 2019 ; Won et al., 2017 ; Yeo, Goh, & Rezaei, 2017 ; Zhao & Bacao, 2020 ), Study 1 employs the six variables to predict customer intention to use OFD services. Moreover, two factors adopted from the Health Belief Model — perceived severity and perceived vulnerability—were included in Study 2 to reflect the COVID-19 pandemic context. In the following section, these factors are explained in detail.

2.2. Predictors of online food delivery usage intention

2.2.1. service attributes.

The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) originally proposed by Davis (1989) states that perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use of a new technology play significant roles in the adoption of the technology ( Davis, Bagozzi, & Warshaw, 1989 ). In the TAM model, perceived usefulness (PU) was defined as “the prospective user's subjective probability that using a specific application system will increase his or her job performance within an organizational context” ( Davis, Bagozzi, & Warshaw, 1989 , p. 985). When customers consider that new technology will improve their productivity, PU arises ( Gentry & Calantone, 2002 ). Previous studies revealed that PU positively affected technology adoption in a variety of fields, such as mobile phone adoption for shopping ( Hung et al., 2012 ), hotel self-service kiosks ( Kim & Qu, 2014 ), and healthcare wearable technology ( Zhang et al., 2017 ).

In this study, to apply PU to the OFD service setting, PU refers to the degree to which people believe that using an OFD service would be a useful way to order meals. Similar to other technology-related studies, OFD research has demonstrated a significant impact of PU on OFD usage intention. For example, Yeo, Goh, & Rezaei, 2017 demonstrated that PU positively influenced continuance intention toward OFD services. Similarly, Roh and Park (2019) revealed PU to be the strongest factor affecting OFD usage intention.

Perceived ease of use (PEOU) is defined as the degree to which a person expects mental or physical challenges in adopting new technology ( Pinho & Soares, 2011 ). Numerous studies have confirmed that PEOU has a significant effect on customers' usage intentions toward a wide variety of technologies. For instance, Ramayah and Ignatius (2005) proposed that if mobile devices and web interfaces are easy to access and require little effort, customers are willing to accept online shopping. They reported that PEOU is a critical factor affecting online shopping intention. The same positive association between PEOU and CIU has been reported in the OFD context ( Ray, Dhir, Bala, & Kaur, 2019 ; Roh & Park, 2019 ; Won et al., 2017 ). Roh and Park (2019) found that the higher the customer's PEOU, the greater the willingness to use OFD services, and ultimately the higher the chance of OFD service success. Ray, Dhir, Bala, & Kaur, 2019 also emphasized the importance of PEOU of OFD services by demonstrating the important roles of the order process, order tracking, and filtering options of the interface in determining CIU.

Besides PEOU and PU, this study employs trust (TR) as a technology-oriented service attribute because TR in the system has been validated as a key driver in adopting new technology in various disciplines, from self-service kiosks during check-in/out in hotels ( Kaushik, Agrawal, & Rahman, 2015 ) to electronic payments ( Mendoza-Tello, Mora, Pujol-López, & Lytras, 2018 ). TR refers to an index of a positive belief regarding the perceived reliability, dependence, and assurance in an individual, object, or procedure ( Fogg & Tseng, 1999 ). TR produces positive feelings toward the technology-based service ( Liu, 2012 ), and customers with low TR about the service tend to be skeptical and reluctant to adopt it ( Grabner-Kraeuter, 2002 ). In the OFD setting, while Jeon et al. (2016) revealed that TR does not affect intention to reuse OFD, several studies have agreed that TR is one of the most critical factors positively affecting CIU ( Cho, Bonn, & Li, 2019 ; Ray & Bala, 2021 ; Zhao & Bacao, 2020 ). Thus, this study generated the following hypotheses:

PU positively influences CIU.

PEOU positively influences CIU.

TR positively influences CIU.

2.2.2. Perceived benefits

Some OFD services charge customers extra fees, such as delivery charges and service fees ( Lichtenstein, 2020 ). However, as OFD companies compete to gain market shares, they frequently offer promotions that cover the fees or discount the total charges to attract new customers and accelerate orders from new and old customers. For example, Grubhub offers a $10-off promotion to new customers and a student discount ( Groupon, 2021 ). In OFD service setting, price saving promotions often serve as effective marketing tools as demonstrated by Kaur et al. (2021) as well as Ray & Bala, 2021 who revealed that free delivery, lower delivery fees, or promotional incentives enhance CIU. Kaur et al. (2021) further noted that customers using OFD services search for a price advantage. Thus, this study examines price saving benefits (PSB) as a critical predictor of CIU. PSB is defined as money-saving benefits (e.g., 10-off promotion, lower delivery/service fee) as well as not charging any additional costs for purchasing products/services (e.g., free delivery) ( Yeo, Goh, & Rezaei, 2017 ). Considering the significant role of PSB in customer OFD usage from existing literature, it is hypothesized that PSB would increase CIU.

Online shopping also saves time traveling to and from a retail store in a time-sensitive modern society ( Morganosky & Cude, 2000 ). Similarly, OFD services could save customers time by avoiding the time spent traveling to a restaurant and waiting in line. Moreover, many web browsers and OFD apps allow customers to store payment and previous order details for efficient checkout, enabling customers to save time ( Statista, 2020 ; Bansal, 2019 ). While Ray, Dhir, Bala, & Kaur, 2019 found no significant association between time saving benefits (TSB) and customer usage intention, much of the existing literature has indicated that TSB of OFD services positively influence CIU ( Correa et al., 2018 ; He, Han, Cheng, Fan, & Dong, 2019 ; Yeo, Goh, & Rezaei, 2017 ). In other words, when customers believe they can avoid traffic and save time by using OFD services, they are more likely to use OFD services. Hence, this study proposed the following hypotheses:

PSB positively influences CIU.

TSB positively influences CIU.

2.2.3. Perceived risk

When dining out, customers oftentimes do not possess tools or skills to measure actual food safety. Instead, customers evaluate the cleanliness and food safety of the restaurant based on various aspects of the restaurant, including restaurant hygiene and employees’ safety practices of wearing clean uniforms and sanitary gloves while touching food ( Liu & Lee, 2018 ). The perceived risk associated with food consumption is called food safety risk perception (FSRP) ( Nardi, Teixeira, Ladeira, & de Oliveira Santini, 2020 ).

FSRP plays a crucial role in the decision-making process of customers buying food ( Frewer et al., 2009 ). For example, customers who have higher FSRP have a higher willingness to buy and pay a premium for safer products or services ( Sharma et al., 2012 ). Customers might possess different FSRP depending on the selling site. A study by Kitsikoglou et al. (2014) demonstrated that consumers have higher FSRP when buying groceries or food online as compared to offline because they cannot see the freshness of products online.

OFD services are challenged to sustain food safety and hygiene because food delivered through OFD services can also be exposed to contamination due to the addition of delivery processes to the traditional restaurant business model. Specifically, controlling temperature, packaging, and using appropriate food containers during the delivery process are additional concerns with OFD services ( Maimaiti et al., 2018 ). Therefore, customers may have higher FSRP when using OFD because they cannot observe the restaurants and employees’ hygiene in person, which may play a negative role in CIU. Based on the previous research related to FSRP and characteristics of OFD services, the following hypothesis was formulated:

FSRP negatively influences CIU.

2.3. The moderating effect of COVID-19

The hospitality and tourism industry is subject to being immediately influenced by the external environment, such as natural disasters, pandemics, and terrorist incidents ( Jin, Qu, & Bao, 2019 ). One of the noticeable events that affected the hospitality and tourism industry was the September 11 attacks in 2001, which harmed travel demand dramatically with a 30% decline until two years after the attack ( Ito & Lee, 2005 ). A crisis event also can change human behavior positively or negatively.

As the coronavirus has dramatically spread, administrative governments or local ordinances have mandated staying-at-home or shelter-in-place orders in March 2020 onward to help prevent person-to-person transmission and shut down businesses ( Sibley et al., 2020 ). The lockdown has promoted sweeping changes to people's lifestyles and psychological aspects ( Laato, Islam, Farooq, & Dhir, 2020 ). Notably, customers showed unusual buying behavior after the COVID-19 outbreak, such as panic buying, which caused a shortage of toilet paper, hand sanitizer, and canned food products in every store ( Laato, Islam, Farooq, & Dhir, 2020 ). Consequently, this study anticipated that the coronavirus alters customer behavior to use OFD amid the pandemic and devises the following hypothesis:

The COVID-19 outbreak moderates the relationships between the predictors and CIU.

2.4. Study 2

Regardless of the actual risk or contagion of the disease, consumers' perception of the COVID-19 pandemic plays a critical role in their purchase decision-making ( Ali, Harris, & Ryu, 2019 ). Among various measurements used to determine people's perceptions of a disease, researchers have widely used perceived severity (PS) and perceived vulnerability (PV), which have their roots in the Health Belief Model (HBM) proposed by Hochbaum (1958) . PS is defined as a personal concern with the seriousness of a situation, and PV refers to personal belief(s) regarding the risk of getting a disease ( Cahyanto et al., 2016 ). The HBM explains that when people have higher PS and PV to an adverse health condition and such outcomes, individuals are more likely to take actions that reduce the threat ( Carpenter, 2010 ).

In the hospitality literature, researchers have widely utilized PS and PV to predict customer behaviors that might be affected by an event or disease such as foodborne illness ( Ali, Harris, & Ryu, 2019 ), Ebola ( Cahyanto et al., 2016 ), norovirus ( Fisher, Almanza, Behnke, Nelson, & Neal, 2018 ), or H1N1 (swine flu) pandemic ( Scherr, Jensen, & Christy, 2017 ). According to Ali, Harris, & Ryu, 2019 , PS and PV negatively affect customer intention to patronize restaurants, as diners hesitated to revisit restaurants after an outbreak of foodborne illness, mostly when they recognized their high vulnerability and the severity of foodborne illness. In a similar vein, travelers who reported higher PS and PV were more likely to avoid domestic travel after the outbreak of Ebola than those who showed low PS and PV ( Cahyanto et al., 2016 ). Accordingly, this study assumes that customers who have high PS and PV may utilize OFD services to minimize the possibility of exposure to the COVID-19 from dining out at restaurants. Thus, the following two hypotheses were developed:

PS positively influences CIU.

PV positively influences CIU.

Fig. 1 depicts the proposed hypotheses in this study.

The proposed conceptual framework.

Note. PU = Perceived Usefulness, PEOU = Perceived Ease of Use, TR = Trust, PSB = Price Saving Benefits, TSB = Time Saving Benefits, FSRP = Food Safety Risk Perception, PS = Perceived Severity, PV = Perceived Vulnerability, CIU = Customer Intention to Use OFD.

3. Methodology

3.1. sampling and data collection.

The target population of this study was U.S. consumers over 18 years old. The data were collected through Amazon's Mechanical Turk (MTurk) over two time periods: the third week of June 2019 and the fifth week of July 2020, representing before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, respectively.

A total of 1045 responses (571 for the before-COVID-19 group and 474 for the during-COVID-19 group) were collected. In the data screening process, 90 incomplete questionnaires and 46 respondents who incorrectly answered attention check questions were omitted. Additionally, three participants who provided straight-lining answers were dropped. Also, 150 responses that took less than 150 s of response time were removed following the cutoff norms of response time suggested by DeSimone & Harms, 2018 and Huang, Curran, Keeney, Poposki, & DeShon, 2012 . Lastly, 56 responses with the same internet protocol and location were removed to prevent duplicate participants. After scrutinizing the data, a total of 700 responses were retained with 333 respondents in the before-COVID-19 group and 367 respondents in the during-COVID-19 group.

The chi-square ( χ 2 ) test of homogeneity was conducted to determine whether frequency counts in the socio-demographic variables were distributed identically between the before-COVID-19 and during-COVID-19 group. The results showed that the majority of demographic variables had no significant differences between before-and during-COVID-19 respondents ( p > .05), except for education level ( p < .001) (see Table 1 ).

Profiles of respondents ( N = 700).

Note . *** p < .001.

3.2. Measurements

A self-administered questionnaire was developed based on a comprehensive review of previous literature ( Castañeda, Muñoz-Leiva, & Luque, 2007 ; Hung et al., 2006 ; Lando et al., 2016 ; Xie et al., 2017 ; Yeo, Goh, & Rezaei, 2017 ). At the beginning of the questionnaire, a definition of OFD was presented. The first section of the questionnaire was comprised of items measuring study constructs, including PU, PEOU, TR, PSB, TSB, FSRP, PS ( Study 2 only ), PV ( Study 2 only ), and CIU using a 7-point Likert scale (1 being “strongly disagree”; 7 being “strongly agree”). The second section included questions asking the socio-demographic information of the respondents. The measurement items and their references are listed in Appendix A .

3.3. Data analysis

The collected data were analyzed using IBM SPSS v26 and AMOS v25. In Study 1, descriptive statistics including frequencies, means, and standard deviations were conducted to summarize the data, and a hierarchical multiple regression analysis was conducted to test the proposed hypotheses ( H1 −7). Before the hierarchical multiple regression analysis, confirmatory factor analysis was performed to check the validity and reliability of the measurement items. Additionally, in Study 2, multiple regression analysis was conducted to test hypotheses 8 and 9, and an independent samples t- test was used to examine the differences between frequencies to use OFD services both before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

As previous studies discovered the significant effect of demographic factors on consumers' online shopping behavior ( Chiang & Dholakia, 2003 ; Hernández, Jiménez, & Martín, 2011 ), four demographic factors—age, gender, household income, and residency—were controlled to determine the pure relationships between the predictors and CIU. Before conducting the hierarchical multiple regression analysis, respondents' age and income were regrouped. Based on the studies by Dhanapal et al. (2015) and Priporas, Stylos, & Fotiadis, 2017 , age was categorized into two groups comprising of Generation Y/Z and Generation X/Baby Boomers. Furthermore, respondents’ household income was grouped into low (less than $69,999) and high (above $70,000) income categories based on the median household income ($68,703) in the United States ( Ahn & Back, 2018 ; U.S. Census Bureau, 2020 ). All categorical control variables were dummy coded, and all continuous predictor variables were mean-centered to clarify regression coefficients and reduced multicollinearity.

4.1. Study 1

4.1.1. profile of the sample.

Table 1 presents a breakdown of the socio-demographics of both samples. In terms of gender, 365 respondents (52.1%) were male, and 335 respondents (47.9%) were female. The respondents' average age was 39.92 years. The majority of the respondents were Caucasian (73%), and about half of the respondents were married (48.1%). More than half of the respondents (60%) worked full-time, and the largest respondent group reported an annual household income between $30,000 and $49,999 (24.3%). Regarding respondents’ residency, over half of the respondents (52.7%) reported living in suburban.

4.1.2. Validity and reliability of constructs

Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to evaluate the reliability and convergent and discriminant validity of the measurement model which was comprised of seven factors: PU, PEOU, TR, PSB, TSB, FSRP, and CIU. Each of the overall goodness-of-fit indices suggested that the seven-factor model fit the data well, χ 2 (168) = 403.90, p < .001, χ 2 /df = 2.404, CFI = 0.978, TLI = 0.972, RMSEA = 0.045 (90% CI: 0.039-0.050), SRMR = 0.035. The constructs' internal consistency was acceptable with composite reliability coefficients ranging from 0.758 to 0.931 ( Fornell & Larcker, 1981 ). Construct validity was examined by assessing convergent and discriminant validity. For convergent validity, both factor loadings and average variance extracted (AVE) were satisfied with the acceptable ranges ( Anderson & Gerbing, 1988 ). Discriminant validity was determined by comparing AVEs with the squared multiple correlations between constructs, but the results indicated that distinctions between PU and PEOU and between PU and TSB were not established. Therefore, chi-square difference tests were conducted and found that six-factor models—PU-PEOU combined and PU-TSB combined—statistically degraded the original measurement model, PU-PEOU combined: Δχ 2 (6) = 174.47, p < .001 and PU-TSB combined: Δχ 2 (6) = 175.99, p < .001, suggesting that the seven-factor model showed a significant improvement in chi-squares over both six-factor models. Thus, discriminant validity was ensured.

4.1.3. Hypotheses testing

A three-step hierarchical multiple regression was conducted to test the hypotheses. First, the control variables of gender, age, income, and residency were entered. Second, predictor variables (PU, PEOU, TR, PSB, TSB, and FSRP) and a moderator variable (COVID-19) were entered. In the third step, interaction terms were entered into the model.

Table 2 presents the results of the hierarchical multiple regression analysis. As for the control variables, the results indicated that female ( β = −0.08, p < .05), Gen Y/Z ( β = 0.11, p < .01; comparing to Gen X/Baby Boomer), urban ( β = 0.17, p < .01; comparing to rural resident), and suburban residents ( β = 0.15, p < .05; comparing to rural resident) showed significantly higher CIU. However, there was an insignificant difference in CIU between high-income and low-income groups ( β = −0.03, n.s. ). Hypotheses 1–6 predicted that six predictors regarding OFD services influence CIU. As proposed, PU (H 1 : β = 0.45, p < .001), PEOU (H 2 : β = 0.08, p < .05), TR (H 6 : β = 0.19, p < .001), PSB (H 3 : β = 0.11, p < .001), and TSB (H 4 : β = 0.11, p < .01) were positively associated with CIU, supporting H1 , H2 , H3 , H4 , and H5 , respectively, controlling for participants’ gender, age, income, and residency (see Model 2). However, FSRP showed an insignificant, negative relationship with CIU ( β = −.02, n.s. ), failing to support H6 . Additionally, COVID-19—as an independent variable—showed a positive, significant impact on CIU, controlling for other variables. This finding implies that customers tend to show more positive CIU during the COVID-19 pandemic than the before-COVID-19 pandemic.

Results of hierarchical regression analysis predicting customer intention to use OFD.

Note . Ref : Reference group; Durbin-Watson statistic = 2.07.

* p < .05.

** p < .01.

*** p < .001.

Lastly, H7a-f proposed that the COVID-19 pandemic moderates the relationships between the predictors and OFD usage intention. However, as Model 3 shows, none of the interaction terms were statistically significant, and the addition of interactions to the model did not improve the model's predictability (Δ R 2 = 0.00, n.s. ), meaning that H7a-f were not supported. The findings indicate that the pandemic event was significantly associated with CIU but did not affect the relationships between the OFD predictors and CIU.

4.2. Study 2

In response to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the restaurant industry, Study 2 further incorporated PS and PV to the COVID-19 into the OFD usage intention prediction model by conducting a multiple regression.

The results indicated that there were no significant impacts of PS ( β = 0.03, n.s. ) and PV ( β = 0.03, n.s. ) on CIU, failing to support H8 and H9 (see Table 3 ). Although PS and PV were not significantly associated with CIU, the degrees of the effects of the other independent variables—including socio-demographic variables—have changed significantly. Considering these variables in the model, more situation-appropriate findings were proposed, i.e., during the COVID-19 pandemic situation. That is, female customers ( β = −0.05, n.s. ) and urban residents ( β = 0.08, n.s. ) are no longer more favorable to CIU compared to their counterparts. On the other hand, the results indicated that Gen Y/Z customers are more willing to use OFD compared to older generations ( β = 0.07, p < .05). Besides, PU ( β = 0.43, p < .001), TR ( β = 0.17, p < .001), PSB ( β = 0.14, p < .01), and TSB ( β = 0.13, p < .01) were still significantly associated with CIU; however, PEOU was no longer significant ( β = 0.06, n.s. ).

The results of multiple regression analysis predicting customer intention to use OFD during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Note . Ref : Reference group.

R 2 ( adj. R 2 ) = 0.59 (0.57), F (13, 353) = 38.64***, Durbin-Watson statistic = 2.07.

Lastly, the respondents’ actual usage (frequency) of OFD was compared before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. An independent samples t- test was conducted to compare the frequencies of OFD usage. The results indicated that respondents tended to use OFD more frequently during the COVID-19 pandemic than before the COVID-19 pandemic ( t = 5.14, p < .001). Specifically, the number of respondents who used OFD services 2–3 times a month, 1–2 times, or 3–5 times a week has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, while those who used OFD services once a month or less has decreased. Fig. 2 shows more detailed frequencies between the two conditions.

Comparison of the OFD usage between before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

5. Discussion and conclusion

5.1. discussion.

The results of both Study 1 and Study 2 showed that PU was the most influential factor in increasing CIU. Similar to previous studies ( Lee, Lee, & Jeon, 2017 ; Yeo, Goh, & Rezaei, 2017 ), this study confirmed that customers are more likely to adopt OFD if they perceive it as useful. The second most significant factor was TR. This finding is paralleled with Flavián et al. (2006) and Wang, Lin, & Luarn, 2006 who found that TR has a significant effect on customer technology adoption intention in the online shopping context. Considering the nature of OFD services that customers place an order via OFD platforms, customers might doubt whether the restaurant accurately receives orders or the quality of food delivered is as good as the quality of food served at the restaurant which explains the importance of TR in the OFD setting.

Surprisingly, Study 1 found that the COVID-19 pandemic did not moderate the relationships between the predictors and CIU. This finding differs from earlier studies, which claimed that a crisis event brings significant behavioral changes to people ( Jin, Qu, & Bao, 2019 ; Laato, Islam, Farooq, & Dhir, 2020 ). The insignificant moderating effect can be interpreted as the factors that significantly influenced CIU before the pandemic still play decisive roles to customers.

Study 2 revealed that PS and PV did not significantly affect OFD usage intention during the pandemic, contradicting the findings of Ali, Harris, & Ryu, 2019 and Cahyanto et al. (2016) . The insignificant effects of PS and PV might be attributable to OFD usage itself not being considered health-related behavior because the Health Belief Model indicated that PS and PV affect consumer's health-promoting behavior. Additionally, Study 2 uncovered situation-appropriate results under the COVID-19 pandemic situation precisely, showing that younger customers (Generation Y/Z) are more willing to use OFD than older customers (Generation X/Baby Boomers). This finding is consistent with other research that revealed Generation Y/Z's online purchasing frequency was higher than Generation X/Baby Boomers, possibly because Generation Y/Z use the internet more frequently than older generations ( Dhanapal et al., 2015 ; Priporas, Stylos, & Fotiadis, 2017 ).

Another notable finding of Study 2 is that FSRP did not significantly affect CIU during the pandemic even though customers are generally more concerned about their safety and health during the pandemic ( Shin & Kang, 2020 ). This could be because customers are aware of the low risk of getting sick with COVID-19 from food as the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and other media have reported ( Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020 ). Moreover, considering that both PSB and TSB significantly increased CIU, customers might also perceive benefits received from food products/services obtained through OFD as outweighing the risks associated with using OFD which is in line with the findings of Nardi, Teixeira, Ladeira, & de Oliveira Santini, 2020 .

5.2. Theoretical implications

This study contributes to the current literature with various theoretical implications. Most importantly, as the OFD market share has grown, researchers have devoted increased attention to OFD customers and their decision-making process. The present research extended the existing literature related to OFD by incorporating various predictors and perceptions of OFD driven from the TAM with additional constructs of TR, PSB, TSB, and FSRP (Study 1). Additionally, under the pandemic situation, Study 2 integrated customers’ PS and PV adopted from the Health Belief Model to the COVID-19 pandemic to better predict CIU. Even though PS and PV were not significant predictors of OFD usage intention, the findings showed the altered effects of different socio-demographic variables and OFD perceptions by controlling severity and vulnerability factors. In this respect, this study fills a significant gap in the extant literature on OFD attributes and CIU.

The current study is arguably among the first to identify relationships between various predictors and CIU across different time frames (before and during the COVID-19 pandemic) to evaluate the effect of a crisis on OFD usage intention. While the results do not indicate that COVID-19 served as a moderator between the predictors and CIU, this study still enriches the literature on consumer behavior toward OFD and OFD usage intention.

5.3. Practical implications

This research provides several unique practical implications for OFD stakeholders. First, considering that PU was the most significant predictor of CIU in both studies, OFD marketers should focus on increasing current and/or potential customers’ awareness of the business and advertising service efficiency to their customers. Specifically, marketing materials should highlight the usefulness of OFD services by emphasizing that customers can stay where they are, enjoy their food anywhere they want and avoid ordering by phone, traveling to pick up meals, and waiting for pick-up. Moreover, OFD services can be useful during a pandemic like COVID-19 because the service minimizes contact between customers and restaurant employees and allows customers to enjoy their favorite restaurant food at home. For example, Uber Eats and Deliveroo, among others, launched contactless “leave at your door service” to help drivers and customers adhere to social distancing guidelines. This gives the restaurant industry, which has been severely damaged, another opportunity to thrive and evolve by meeting the changing demand in the foodservice market.

Second, the results demonstrate that TR is the second most significant factor of CIU, which means that the more customers trust OFD services, the more willing they are to use them. From the business's perspective, gaining trust from their customers is building relationships with their customers. Therefore, OFD businesses should invest in customer relationship management (CRM) through various communication channels such as social media and newsletters by being transparent, authentic, and willing to listen to their customers. Furthermore, like major online retailers, OFD providers could present tangible evidence to reduce customer uncertainty on the quality of OFD service by showing 100% customer satisfaction guaranteed and statistics on customer satisfaction scores or number of users. Additionally, customers who have not used OFD might consider it a new technology, which might cause them to doubt how OFD operates or how personal information will be protected. Thus, OFD companies need to explain how they work and how personal and payment information collected through the company will be restored and protected.

Third, because this study confirmed that PSB and TSB positively affect CIU, companies should understand that customers expect benefits from using OFD services. Therefore, using promotional materials such as ads and social networking site (SNS) postings, OFD companies should accentuate potential benefits—time and cost— that the customers can receive as compared to cooking over a hot stove all day or waiting in a long line at a restaurant. Additionally, OFD marketers can provide regular discount promotions, such as free delivery, to attract new customers and launch reward programs. For instance, Uber Eats regularly offers a “$0 delivery fee” promotion and advertises this on their website. Furthermore, they recently teamed up with American Express to provide a Free Eats Pass membership, which provides free delivery and 5% off restaurant orders. By providing information on the estimated delivery time on the OFD platform, customers can visualize the time saving benefits they would gain from using the service.

Fourth, the change in frequency of customer usage of OFD between time periods before and during the pandemic indicates that social distancing measures associated with the pandemic led customers to use OFD services more frequently. Thus, as restaurant business models are shifting in keeping with changing consumer preferences, restaurants can benefit from the popularity of OFD services by partnering with them. Many restaurants transformed their service methods during the pandemic, offering curbside pickup and OFD service, to adapt to the new normal and survive in the competitive market. As an extreme case, DoorDash recently launched a “Reopen for Delivery” program, which gives bankrupted restaurants a fighting chance by matching them with ghost kitchen facilities. Thus, for restaurants, a new business model or re-shaping operation could be a plausible strategy to survive in this era.

Lastly, the findings of Study 2 highlight that during the COVID-19 pandemic, generations Y and Z were more willing to use OFD compared to older generations. OFD businesses should target younger generations to maximize business growth. For instance, OFD service marketers can use SNSs to hold competitions and/or distribute discount codes because the younger generations actively use SNSs to communicate with others ( Williams & Page, 2011 ). Utilizing social media influencers to promote OFD would also appeal to the younger generations.

5.4. Limitations and future studies

As with any research, this study is not free from limitations. This study focused on the general perception of OFD rather than focusing on a specific OFD platform. As customers might perceive each OFD service platform differently, future studies can examine whether significant predictors affecting CIU differ depending on the different OFD services. In addition, this study only considered the platform-to-consumer delivery type of OFD services (e.g., DoorDash, Uber Eats) and did not assess restaurant-to-consumer OFD (e.g., Domino's Pizza, Pizza Hut) ( Poluliakh, 2020 ). Factors affecting CIU might change depending on the type of OFD which is worth investigating for future research. Also, this study focused on CIU to use OFD regardless of their previous experience with OFD. Future studies may consider adding more attitudinal and behavioral intention constructs—customer satisfaction, positive word-of-mouth, willingness to pay a premium, and revisit intention—to provide more fruitful explanations of the linkages between them. Lastly, this study collected the during-pandemic data in July 2020, but CIU may change in the early or late stage of the COVID-19 pandemic. Future research can analyze what factors have a significant impact on the CIU in the later period of COVID-19.

Appendix A. Measurement items

- Ahn J., Back K.-J. Antecedents and consequences of customer brand engagement in integrated resorts. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2018; 75 :144–152. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ali F., Harris K.J., Ryu K. Consumers’ return intentions towards a restaurant with foodborne illness outbreaks: Differences across restaurant type and consumers’ dining frequency. Food Control. 2019; 98 :424–430. [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson J.C., Gerbing D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin. 1988; 103 (3):411–423. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bansal A. On-demand food delivery apps are making the life easier. Jungleworks. https://jungleworks.com/on-demand-food-delivery-apps-are-making-the-life-easier/

- Cahyanto I., Wiblishauser M., Pennington-Gray L., Schroeder A. The dynamics of travel avoidance: The case of Ebola in the US. Tourism Management Perspectives. 2016; 20 :195–203. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carpenter C.J. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of health belief model variables in predicting behavior. Health Communication. 2010; 25 (8):661–669. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Castañeda J.A., Muñoz-Leiva F., Luque T. Web acceptance model (WAM): Moderating effects of user experience. Information & Management. 2007; 44 (4):384–396. [ Google Scholar ]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Food and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/daily-life-coping/food-and-COVID-19.html

- Chiang K.-P., Dholakia R.R. Factors driving consumer intention to shop online: An empirical investigation. Journal of Consumer Psychology. 2003; 13 (1–2):177–183. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cho M., Bonn M.A., Li J.J. Differences in perceptions about food delivery apps between single-person and multi-person households. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2019; 77 :108–116. [ Google Scholar ]

- Correa J.C., Garzón W., Brooker P., Sakarkar G., Carranza S.A., Yunado L., Rincón A. Evaluation of collaborative consumption of food delivery services through web mining techniques. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services. 2019; 46 :45–50. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cui B., Liao Q., Lam W.W.T., Liu Z.P., Fielding R. Avian influenza A/H7N9 risk perception, information trust and adoption of protective behaviours among poultry farmers in Jiangsu Province, China. BMC Public Health. 2017; 17 (1):463. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Davis F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly. 1989; 13 (3):319–340. [ Google Scholar ]

- Davis F.D., Bagozzi R.P., Warshaw P.R. User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Management Science. 1989; 35 (8):982–1003. [ Google Scholar ]

- DeSimone J.A., Harms P.D. Dirty data: The effects of screening respondents who provide low-quality data in survey research. Journal of Business and Psychology. 2018; 33 (5):559–577. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dhanapal S., Vashu D., Subramaniam T. Perceptions on the challenges of online purchasing: A study from “baby boomers”, generation “X” and generation “Y” point of views. Contaduría Y Administración. 2015; 60 :107–132. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fisher J.J., Almanza B.A., Behnke C., Nelson D.C., Neal J. Norovirus on cruise ships: Motivation for handwashing? International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2018; 75 :10–17. [ Google Scholar ]

- Flavián C., Guinalíu M., Gurrea R. The role played by perceived usability, satisfaction and consumer trust on website loyalty. Information & Management. 2006; 43 (1):1–14. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fogg B.J., Tseng H. The elements of computer credibility. SIGCHI conference. 1999. http://research.cs.vt.edu/ns/cs5724papers/7.hciincontext.socpsyc.fogg.elements.pdf

- Fornell C., Larcker D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research. 1981; 18 (1):39–50. [ Google Scholar ]

- Frewer L., de Jonge J., van Kleef E. Consumer perceptions of food safety. Medical Science. 2009; 2 :243. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gentry L., Calantone R. A comparison of three models to explain shop‐bot use on the web. Psychology and Marketing. 2002; 19 (11):945–956. [ Google Scholar ]

- Grabner-Kraeuter S. The role of consumers' trust in online-shopping. Journal of Business Ethics. 2002; 39 :43–50. [ Google Scholar ]

- Groupon Grubhub promo codes. 2021. https://www.groupon.com/coupons/grubhub

- Gunden N., Morosan C., DeFranco A. Consumers' intentions to use online food delivery systems in the USA. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. 2020; 32 (3):1325–1345. [ Google Scholar ]

- He Z., Han G., Cheng T.C.E., Fan B., Dong J. Evolutionary food quality and location strategies for restaurants in competitive online-to-offline food ordering and delivery markets: An agent-based approach. International Journal of Production Economics. 2019; 215 :61–72. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hernández B., Jiménez J., Martín M.J. Age, gender and income: Do they really moderate online shopping behaviour? Online Information Review. 2011; 35 (1):113–133. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hochbaum G., Rosenstock I., Kegels S. Vol. 1. 1952. Health belief model. United states public health service. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hung S.-Y., Chang C.-M., Yu T.-J. Determinants of user acceptance of the e-Government services: The case of online tax filing and payment system. Government Information Quarterly. 2006; 23 (1):97–122. [ Google Scholar ]

- Huang J.L., Curran P.G., Keeney J., Poposki E.M., DeShon R.P. Detecting and deterring insufficient effort responding to surveys. Journal of Business and Psychology. 2012; 27 (1):99–114. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hung M.-C., Yang S.-T., Hsieh T.-C. An examination of the determinants of mobile shopping continuance. International Journal of Electronic Business Management. 2012; 10 (1):29. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ito H., Lee D. Assessing the impact of the September 11 terrorist attacks on US airline demand. Journal of the Economics of Business. 2005; 57 (1):75–95. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jeon H.-M., Kim M.-J., Jeong H.-C. Influence of smart phone food delivery apps' service quality on emotional response and app reuse intention-Focused on PAD theory. Culinary Science and Hospitality Research. 2016; 22 (2):206–221. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jin X.C., Qu M., Bao J. Impact of crisis events on Chinese outbound tourist flow: A framework for post-events growth. Tourism Management. 2019; 74 :334–344. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kaur P., Dhir A., Talwar S., Ghuman K. The value proposition of food delivery apps from the perspective of theory of consumption value. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. 2021; 33 (4):1129–1159. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kaushik A.K., Agrawal A.K., Rahman Z. Tourist behaviour towards self-service hotel technology adoption: Trust and subjective norm as key antecedents. Tourism Management Perspectives. 2015; 16 :278–289. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kim J.J., Kim I., Hwang J. A change of perceived innovativeness for contactless food delivery services using drones after the outbreak of COVID-19. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2021; 93 :102758. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kim M., Qu H. Travelers' behavioral intention toward hotel self-service kiosks usage. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. 2014; 26 (2):225–245. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kitsikoglou M., Chatzis V., Panagiotopoulos F., Mardiris V. The 9th mibes international conference. 2014. Factors affecting consumer intention to use internet for food shopping. http://mais.ihu.gr/wp-ontent/uploads/2020/07/2014_MIBES_Kitsikoglou.pdf [ Google Scholar ]

- Laato S., Islam A.N., Farooq A., Dhir A. Unusual purchasing behavior during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic: The stimulus-organism-response approach. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services. 2020; 57 :102224. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lando A., Verrill L., Liu S., Smith E., Branch C.S. 2016 FDA food safety survey. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. 2016. https://www.fda.gov/files/food/published/Food-Safety-Survey-2016.pdf

- Lichtenstein N. The hidden cost of food delivery. Tech Crunch. 2020, March 16. https://techcrunch.com/2020/03/16/the-hidden-cost-of-food-delivery/

- Lee E.-Y., Lee S.-B., Jeon Y.J.J. Factors influencing the behavioral intention to use food delivery apps. Social Behavior and Personality: International Journal. 2017; 45 (9):1461–1473. [ Google Scholar ]

- Li C., Mirosa M., Bremer P. Review of online food delivery pplatforms and their impacts on sustainability. Sustainability. 2020; 12 (14):5528. [ Google Scholar ]

- Liu P., Lee Y.M. An investigation of consumers’ perception of food safety in the restaurants. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2018; 73 :29–35. [ Google Scholar ]

- Liu S. The impact of forced use on customer adoption of self-service technologies. Computers in Human Behavior. 2012; 28 (4):1194–1201. [ Google Scholar ]

- Maida J. Analysis on impact of Covid-19- online on-demand food delivery services market 2019-2023. Businesswire. 2020. https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20200430005160/en/Analysis-Impact-Covid-19--Online-On-Demand-Food-Delivery

- Maimaiti M., Zhao X., Jia M., Ru Y., Zhu S. How we eat determines what we become: Opportunities and challenges brought by food delivery industry in a changing world in China. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2018; 72 (9):1282–1286. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mendoza-Tello J.C., Mora H., Pujol-López F.A., Lytras M.D. Social commerce as a driver to enhance trust and intention to use cryptocurrencies for electronic payments. IEEE Access. 2018; 6 :50737–50751. [ Google Scholar ]

- Morganosky M.A., Cude B.J. Consumer response to online grocery shopping. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management. 2000; 28 (1):17–26. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nardi V.A.M., Teixeira R., Ladeira W.J., de Oliveira Santini F. A meta-analytic review of food safety risk perception. Food Control. 2020; 112 :107089. [ Google Scholar ]

- National Restaurant Association The restaurant industry impact survey. 2020. https://restaurant.org/downloads/pdfs/business/covid19-infographic-impact-survey.pdf

- National Restaurant Association Restaurant sales fell to their lowest real level in over 35 years. 2020. https://restaurant.org/articles/news/restaurant-sales-fell-to-lowest-level-in-35-years

- NPD Online food orders, delivery surge amid COVID-19 lockdown. 2020. https://www.npd.com/wps/portal/npd/us/news/press-releases/2020/while-total-us-restaurant-traffic-declines-by-22-in-march-digital-and-delivery-orders-jump-by-over-60/

- Pinho J.C.M.R., Soares A.M. Examining the technology acceptance model in the adoption of social networks. The Journal of Research in Indian Medicine. 2011; 5 (2/3):116–129. [ Google Scholar ]

- Poluliakh Y. Two types of on-demand food delivery platforms-Pros and cons. Yalantis. 2020 https://yalantis.com/blog/three-types-of-on-demand-delivery-platforms-pros-and-cons/#:~:text=There%20are%20two%20types%20of,demand%20food%20delivery%20businesses%20offer [ Google Scholar ]

- Priporas C.-V., Stylos N., Fotiadis A.K. Generation Z consumers’ expectations of interactions in smart retailing: A future agenda. Computers in Human Behavior. 2017; 77 :374–381. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ramayah T., Ignatius J. Impact of perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use and perceived enjoyment on intention to shop online. The ICFAI Journal of Systems Management. 2005; 3 (3):36–51. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ray A., Bala P.K. User generated content for exploring factors affecting intention to use travel and food delivery services. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2021; 92 :102730. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ray A., Dhir A., Bala P.K., Kaur P. Why do people use food delivery apps (FDA)? A uses and gratification theory perspective. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services. 2019; 51 :221–230. [ Google Scholar ]

- Restaurant Law Center Official orders closing or restricting foodservice establishments in response to COVID-19. 2020. https://restaurant.org/downloads/pdfs/business/covid19-official-orders-closing-or-restricting.pdf

- Roh M., Park K. Adoption of O2O food delivery services in South Korea: The moderating role of moral obligation in meal preparation. International Journal of Information Management. 2019; 47 :262–273. [ Google Scholar ]

- Scherr C.L., Jensen J.D., Christy K. Dispositional pandemic worry and the health belief model: Promoting vaccination during pandemic events. Journal of Public Health. 2017; 39 (4):242–250. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sharma A., Sneed J., Beattie S. Willingness to pay for safer foods in foodservice establishments. Journal of Foodservice Business Research. 2012; 15 (1):101–116. [ Google Scholar ]

- Shin H., Kang J. Reducing perceived health risk to attract hotel customers in the COVID-19 pandemic era: Focused on technology innovation for social distancing and cleanliness. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2020; 91 :102664. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sibley C.G., Greaves L.M., Satherley N., Wilson M.S., Overall N.C., Lee C.H.…Milfont T.L. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and nationwide lockdown on trust, attitudes toward government, and well-being. American Psychologist. 2020; 75 (5):618–630. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Statista eServices Report 2020. 2020. https://www.statista.com/study/42306/eservices-report/

- Suhartanto D., Helmi Ali M., Tan K.H., Sjahroeddin F., Kusdibyo L. Loyalty toward online food delivery service: The role of e-service quality and food quality. Journal of Foodservice Business Research. 2019; 22 (1):81–97. [ Google Scholar ]

- The Other Stream. (n.d.). What are the benefits of online ordering food. http://www.theotherstream.com/what-are-the-benefits-of-online-ordering-food/ .

- U.S. Census Bureau Income and poverty in the United States: 2019. 2020. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2020/demo/p60-270.html#:~:text=Median%20household%20income%20was%20%2468%2C703,and%20Table%20A%2D1

- Wang Y.S., Lin H.H., Luarn P. Predicting consumer intention to use mobile service. Information Systems Journal. 2006; 16 (2):157–179. [ Google Scholar ]

- Williams K.C., Page R.A. Marketing to the generations. Journal of Behavioral Studies in Business. 2011; 3 (1):37–53. [ Google Scholar ]

- Won J., Kang H., Kim B. The effect of food online-to-offline (O2O) service characteristics on customer beliefs using the technology acceptance model. Culinary Science and Hospitality Research. 2017; 23 (7):97–111. [ Google Scholar ]

- World Health Organization HO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020. 2020. https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19

- Xie Q., Song W., Peng X., Shabbir M. Predictors for e-government adoption: Integrating TAM, TPB, trust and perceived risk. The Electronic Library. 2017; 35 (1):2–20. [ Google Scholar ]

- Yazdanpanah M, Forouzani M, Hojjati M. Willingness of Iranian young adults to eat organic foods: Application of the Health Belief Model. Food Quality and Preference. 2015; 41 :75–83. [ Google Scholar ]

- Yeo V.C.S., Goh S.-K., Rezaei S. Consumer experiences, attitude and behavioral intention toward online food delivery (OFD) services. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services. 2017; 35 :150–162. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhang M., Luo M., Nie R., Zhang Y. Technical attributes, health attribute, consumer attributes and their roles in adoption intention of healthcare wearable technology. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2017; 108 :97–109. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhao Y., Bacao F. What factors determining customer continuingly using food delivery apps during 2019 novel coronavirus pandemic period? International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2020; 91 :102683. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

The Evolution of the Online Food Delivery Industry

- The Evolution of the Online Food Delivery Industry Replay

Heath Terry, Goldman Sachs Research’s business unit leader for the Technology, Media and Telecom Group, discusses the surge in demand for food delivery during the pandemic and the outlook for the industry beyond it.

This video was recorded on January 15, 2021

This video should not be copied, distributed, published or reproduced, in whole or in part. the information contained in this recording was obtained from publicly available sources, has not been independently verified by goldman sachs, may not be current, and goldman sachs has no obligation to provide any updates or changes. all price references and market forecasts are as of the date of recording. this video is not a product of goldman sachs global investment research and the information contained in this video is not financial research. the views and opinions expressed in this video are not necessarily those of goldman sachs and may differ from the views and opinions of other departments or divisions of goldman sachs and its affiliates. goldman sachs is not providing any financial, economic, legal, accounting, or tax advice or recommendations in this podcast. the information contained in this video does not constitute investment advice or an offer to buy or sell securities from any goldman sachs entity to the listener and should not be relied upon to evaluate any potential transaction. in addition, the receipt of this video by any listener is not to be taken to constitute such person a client of any goldman sachs entity. neither goldman sachs nor any of its affiliates makes any representation or warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy or completeness of the statements or any information contained in this video and any liability therefore (including in respect of direct, indirect or consequential loss or damage) is expressly disclaimed. , explore more insights, sign up for briefings, a newsletter from goldman sachs about trends shaping markets, industries and the global economy..

Thank you for subscribing to BRIEFINGS: a newsletter from Goldman Sachs about trends shaping markets, industries and the global economy.