Problem-solving in Leadership: How to Master the 5 Key Skills

The role of problem-solving in enhancing team morale, the right approach to problem-solving in leadership, developing problem-solving skills in leadership, leadership problem-solving examples.

Other Related Blogs

What’s the Role of Problem-solving in Leadership?

- Getting to the root of the issue: First, Sarah starts by looking at the numbers for the past few months. She identifies the products for which sales are falling. She then attempts to correlate it with the seasonal nature of consumption or if there is any other cause hiding behind the numbers.

- Identifying the sources of the problem: In the next step, Sarah attempts to understand why sales are falling. Is it the entry of a new competitor in the next neighborhood, or have consumption preferences changed over time? She asks some of her present and past customers for feedback to get more ideas.

- Putting facts on the table: Next up, Sarah talks to her sales team to understand their issues. They could be lacking training or facing heavy workloads, impacting their productivity. Together, they come up with a few ideas to improve sales.

- Selection and application: Finally, Sarah and her team pick up a few ideas to work on after analyzing their costs and benefits. They ensure adequate resources, and Sarah provides support by guiding them wherever needed during the planning and execution stage.

- Identifying the root cause of the problem.

- Brainstorming possible solutions.

- Evaluating those solutions to select the best one.

- Implementing it.

- Analytical thinking: Analytical thinking skills refer to a leader’s abilities that help them analyze, study, and understand complex problems. It allows them to dive deeper into the issues impacting their teams and ensures that they can identify the causes accurately.

- Critical Thinking: Critical thinking skills ensure leaders can think beyond the obvious. They enable leaders to question assumptions, break free from biases, and analyze situations and facts for accuracy.

- Creativity: Problems are often not solved straightaway. Leaders need to think out of the box and traverse unconventional routes. Creativity lies at the center of this idea of thinking outside the box and creating pathways where none are apparent.

- Decision-making: Cool, you have three ways to go. But where to head? That’s where decision-making comes into play – fine-tuning analysis and making the choices after weighing the pros and cons well.

- Effective Communication: Last but not at the end lies effective communication that brings together multiple stakeholders to solve a problem. It is an essential skill to collaborate with all the parties in any issue. Leaders need communication skills to share their ideas and gain support for them.

How do Leaders Solve Problems?

Business turnaround, crisis management, team building.

Process improvement

Ace performance reviews with strong feedback skills..

Master the art of constructive feedback by reviewing your skills with a free assessment now.

Why is problem solving important?

What is problem-solving skills in management, how do you develop problem-solving skills.

Top 15 Tips for Effective Conflict Mediation at Work

Top 10 games for negotiation skills to make you a better leader, manager effectiveness: a complete guide for managers in 2023, 5 proven ways managers can build collaboration in a team.

- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- *New* Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

Why Problem-Solving Skills Are Essential for Leaders in Any Industry

- 17 Jan 2023

Any organization offering a product or service is in the business of solving problems.

Whether providing medical care to address health issues or quick convenience to those hungry for dinner, a business’s purpose is to satisfy customer needs .

In addition to solving customers’ problems, you’ll undoubtedly encounter challenges within your organization as it evolves to meet customer needs. You’re likely to experience growing pains in the form of missed targets, unattained goals, and team disagreements.

Yet, the ubiquity of problems doesn’t have to be discouraging; with the right frameworks and tools, you can build the skills to solve consumers' and your organization’s most challenging issues.

Here’s a primer on problem-solving in business, why it’s important, the skills you need, and how to build them.

Access your free e-book today.

What Is Problem-Solving in Business?

Problem-solving is the process of systematically removing barriers that prevent you or others from reaching goals.

Your business removes obstacles in customers’ lives through its products or services, just as you can remove obstacles that keep your team from achieving business goals.

Design Thinking

Design thinking , as described by Harvard Business School Dean Srikant Datar in the online course Design Thinking and Innovation , is a human-centered , solutions-based approach to problem-solving and innovation. Originally created for product design, design thinking’s use case has evolved . It’s now used to solve internal business problems, too.

The design thinking process has four stages :

- Clarify: Clarify a problem through research and feedback from those impacted.

- Ideate: Armed with new insights, generate as many solutions as possible.

- Develop: Combine and cull your ideas into a short list of viable, feasible, and desirable options before building prototypes (if making physical products) and creating a plan of action (if solving an intangible problem).

- Implement: Execute the strongest idea, ensuring clear communication with all stakeholders about its potential value and deliberate reasoning.

Using this framework, you can generate innovative ideas that wouldn’t have surfaced otherwise.

Creative Problem-Solving

Another, less structured approach to challenges is creative problem-solving , which employs a series of exercises to explore open-ended solutions and develop new perspectives. This is especially useful when a problem’s root cause has yet to be defined.

You can use creative problem-solving tools in design thinking’s “ideate” stage, which include:

- Brainstorming: Instruct everyone to develop as many ideas as possible in an allotted time frame without passing judgment.

- Divergent thinking exercises: Rather than arriving at the same conclusion (convergent thinking), instruct everyone to come up with a unique idea for a given prompt (divergent thinking). This type of exercise helps avoid the tendency to agree with others’ ideas without considering alternatives.

- Alternate worlds: Ask your team to consider how various personas would manage the problem. For instance, how would a pilot approach it? What about a young child? What about a seasoned engineer?

It can be tempting to fall back on how problems have been solved before, especially if they worked well. However, if you’re striving for innovation, relying on existing systems can stunt your company’s growth.

Related: How to Be a More Creative Problem-Solver at Work: 8 Tips

Why Is Problem-Solving Important for Leaders?

While obstacles’ specifics vary between industries, strong problem-solving skills are crucial for leaders in any field.

Whether building a new product or dealing with internal issues, you’re bound to come up against challenges. Having frameworks and tools at your disposal when they arise can turn issues into opportunities.

As a leader, it’s rarely your responsibility to solve a problem single-handedly, so it’s crucial to know how to empower employees to work together to find the best solution.

Your job is to guide them through each step of the framework and set the parameters and prompts within which they can be creative. Then, you can develop a list of ideas together, test the best ones, and implement the chosen solution.

Related: 5 Design Thinking Skills for Business Professionals

4 Problem-Solving Skills All Leaders Need

1. problem framing.

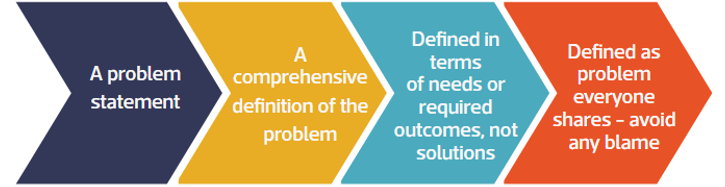

One key skill for any leader is framing problems in a way that makes sense for their organization. Problem framing is defined in Design Thinking and Innovation as determining the scope, context, and perspective of the problem you’re trying to solve.

“Before you begin to generate solutions for your problem, you must always think hard about how you’re going to frame that problem,” Datar says in the course.

For instance, imagine you work for a company that sells children’s sneakers, and sales have plummeted. When framing the problem, consider:

- What is the children’s sneaker market like right now?

- Should we improve the quality of our sneakers?

- Should we assess all children’s footwear?

- Is this a marketing issue for children’s sneakers specifically?

- Is this a bigger issue that impacts how we should market or produce all footwear?

While there’s no one right way to frame a problem, how you do can impact the solutions you generate. It’s imperative to accurately frame problems to align with organizational priorities and ensure your team generates useful ideas for your firm.

To solve a problem, you need to empathize with those impacted by it. Empathy is the ability to understand others’ emotions and experiences. While many believe empathy is a fixed trait, it’s a skill you can strengthen through practice.

When confronted with a problem, consider whom it impacts. Returning to the children’s sneaker example, think of who’s affected:

- Your organization’s employees, because sales are down

- The customers who typically buy your sneakers

- The children who typically wear your sneakers

Empathy is required to get to the problem’s root and consider each group’s perspective. Assuming someone’s perspective often isn’t accurate, so the best way to get that information is by collecting user feedback.

For instance, if you asked customers who typically buy your children’s sneakers why they’ve stopped, they could say, “A new brand of children’s sneakers came onto the market that have soles with more traction. I want my child to be as safe as possible, so I bought those instead.”

When someone shares their feelings and experiences, you have an opportunity to empathize with them. This can yield solutions to their problem that directly address its root and shows you care. In this case, you may design a new line of children’s sneakers with extremely grippy soles for added safety, knowing that’s what your customers care most about.

Related: 3 Effective Methods for Assessing Customer Needs

3. Breaking Cognitive Fixedness

Cognitive fixedness is a state of mind in which you examine situations through the lens of past experiences. This locks you into one mindset rather than allowing you to consider alternative possibilities.

For instance, your cognitive fixedness may make you think rubber is the only material for sneaker treads. What else could you use? Is there a grippier alternative you haven’t considered?

Problem-solving is all about overcoming cognitive fixedness. You not only need to foster this skill in yourself but among your team.

4. Creating a Psychologically Safe Environment

As a leader, it’s your job to create an environment conducive to problem-solving. In a psychologically safe environment, all team members feel comfortable bringing ideas to the table, which are likely influenced by their personal opinions and experiences.

If employees are penalized for “bad” ideas or chastised for questioning long-held procedures and systems, innovation has no place to take root.

By employing the design thinking framework and creative problem-solving exercises, you can foster a setting in which your team feels comfortable sharing ideas and new, innovative solutions can grow.

How to Build Problem-Solving Skills

The most obvious answer to how to build your problem-solving skills is perhaps the most intimidating: You must practice.

Again and again, you’ll encounter challenges, use creative problem-solving tools and design thinking frameworks, and assess results to learn what to do differently next time.

While most of your practice will occur within your organization, you can learn in a lower-stakes setting by taking an online course, such as Design Thinking and Innovation . Datar guides you through each tool and framework, presenting real-world business examples to help you envision how you would approach the same types of problems in your organization.

Are you interested in uncovering innovative solutions for your organization’s business problems? Explore Design Thinking and Innovation —one of our online entrepreneurship and innovation courses —to learn how to leverage proven frameworks and tools to solve challenges. Not sure which course is right for you? Download our free flowchart .

About the Author

Smart. Open. Grounded. Inventive. Read our Ideas Made to Matter.

Which program is right for you?

Through intellectual rigor and experiential learning, this full-time, two-year MBA program develops leaders who make a difference in the world.

A rigorous, hands-on program that prepares adaptive problem solvers for premier finance careers.

A 12-month program focused on applying the tools of modern data science, optimization and machine learning to solve real-world business problems.

Earn your MBA and SM in engineering with this transformative two-year program.

Combine an international MBA with a deep dive into management science. A special opportunity for partner and affiliate schools only.

A doctoral program that produces outstanding scholars who are leading in their fields of research.

Bring a business perspective to your technical and quantitative expertise with a bachelor’s degree in management, business analytics, or finance.

A joint program for mid-career professionals that integrates engineering and systems thinking. Earn your master’s degree in engineering and management.

An interdisciplinary program that combines engineering, management, and design, leading to a master’s degree in engineering and management.

Executive Programs

A full-time MBA program for mid-career leaders eager to dedicate one year of discovery for a lifetime of impact.

This 20-month MBA program equips experienced executives to enhance their impact on their organizations and the world.

Non-degree programs for senior executives and high-potential managers.

A non-degree, customizable program for mid-career professionals.

MIT Leadership Center

Problem-led Leadership: An MIT Style of Leading

Read the full paper here

By and large, MIT graduates don’t see becoming a “leader” as a top priority. In fact, they are often even uncomfortable with the label and rarely describe themselves that way. Instead, they follow their passion for solving big, complex problems and consequently develop into problem-led leaders along the way.

What makes problem-led leadership distinct

They choose challenge over trappings. Intellect, innovation, and real outputs matter more than the appearance of success. They are passionately curious and obsessive problem-solvers. They embrace ambiguity, energized by the impossible and value the role iteration plays in finding solutions that work.

They let problems lead. This variety of leader doesn’t follow people, they follow problems—big, tricky, complex problems that have the potential to make a much-needed impact on the world. Finding viable solutions drives them at the core.

They choose collaboration. They recognize they can’t do it alone and enlist the most capable people they know to advance their mission. They bring together diverse perspectives and extraordinary skill sets. They appreciate the elevated creativity and output it yields in service of finding a solution.

They step up and step out. They believe that the best person to lead the charge is the one with the “super power”—knowledge and expertise—most relevant to that phase of work. They step up and lead until it is time to pass the baton and defer to another teammate. This manner of working demands a sense of humility and respect for others’ unique strengths and abilities.

They work the problem tirelessly. They embrace the scientific method, starting by identifying the right questions to make sure they’re solving the right problem. They roll up their sleeves, get their hands dirty and develop new skills as needed to create, fail fast, and iterate. They do whatever it takes to move the needle.

They do what the data say. Highly analytical by nature, they rely on data when it comes to making decisions. Using facts and findings as their compass enables them to flourish in the midst of an otherwise ambiguous and unstructured process.

A style of leadership worth sharing

In their recent article, “ How to Cultivate Leadership That Is Honed to Solve Problems ,” Ancona and Gregersen synthesize the findings from numerous in-depth interviews, assessments of institutional artifacts and earlier data from companies that employ MIT alumni. They take a deep dive into the patterns that emerge and ultimately define the highly effective style as Problem-Led Leadership . This distinct approach to leadership has implications for individuals and organizations, is critical in highly innovative and creative environments, and can help people solve complex problems in our world.

- What is Strategy?

- Business Models

- Developing a Strategy

- Strategic Planning

- Competitive Advantage

- Growth Strategy

- Market Strategy

- Customer Strategy

- Geographic Strategy

- Product Strategy

- Service Strategy

- Pricing Strategy

- Distribution Strategy

- Sales Strategy

- Marketing Strategy

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Organizational Strategy

- HR Strategy – Organizational Design

- HR Strategy – Employee Journey & Culture

- Process Strategy

- Procurement Strategy

- Cost and Capital Strategy

- Business Value

- Market Analysis

- Problem Solving Skills

- Strategic Options

- Business Analytics

- Strategic Decision Making

- Process Improvement

- Project Planning

- Team Leadership

- Personal Development

- Leadership Maturity Model

- Leadership Team Strategy

- The Leadership Team

- Leadership Mindset

- Communication & Collaboration

- Problem Solving

- Decision Making

- People Leadership

- Strategic Execution

- Executive Coaching

- Strategy Coaching

- Business Transformation

- Strategy Workshops

- Leadership Strategy Survey

- Leadership Training

- Who’s Joe?

PROBLEM SOLVING

The leadership team maturity model.

“We cannot solve our problems with the same level of thinking that created them.” ―ALBERT EINSTEIN

Problem solving is about properly defining problems, correctly diagnosing situations, ideating creative and elegant solutions, deciding on the appropriate path, creating efficient and effective plans, and continuously optimizing and driving execution . Problem solving skills are at the core of great strategy and high-performing leadership teams. Essentially, the primary activity of elite leadership groups revolves around solving problems . Developing this skill set is arguably the most complex challenge for individuals and leadership teams alike, as it demands enhancements in both personal and collective critical thinking and creativity. The good news is that leadership teams can learn and systematically improve their problem solving by working on the fundamentals of focus, framing, logic, and creative ideation.

High-performing teams focus their problem solving on what matters to drive the business forward. They are artful and creative in properly framing problems and solution sets. They use strong logic backed by fact-bases and analytics to seek the truth. And, they are great at the creative ideation necessary to develop elegant solutions to their problems.

1. Focus: Prioritizing problem-solving efforts on what significantly impacts the business's long-term success is crucial. High-performing leadership teams excel in focusing their resources and brainpower on critical issues, enhancing their efficiency and effectiveness in driving the business model forward.

2. Framing: How leadership teams frame problems and solutions determines their approach to solving them. High-performing teams adeptly use correct framing and frameworks, stepping back to carefully consider the best way to address an issue and facilitating the discovery of robust solutions.

- LEADERSHIP MATURITY MODEL

- Communication

- Collaboration

- The Author - Joe Newsum

3. Logic: Logic forms the backbone of problem-solving, involving the breakdown of issues, hypothesis testing, and thorough analysis . High-performing teams invest considerable time in logical reasoning to diagnose problems, ideate solutions, and develop effective plans, often requiring a significant improvement in logical skills for lower-performing teams.

4. Creative Ideation: The critical phase where groundbreaking solutions are conceived, necessitating a commitment to expanding and refining ideas. High-performing leadership teams are distinguished by their ability to brainstorm and refine a wide array of ideas, leading to elegant solutions that propel the business forward.

Problem solving things that don't matter doesn't matter. Most of what most leadership teams bother themselves with day in and day out doesn't matter. Low-performing leadership teams don't focus enough on their problem solving and thinking on things that matter to the business's long-term success. They often focus on short-term issues, the constant fires that flare up, cutting costs at the expense of the value proposition , and low-value strategies. High-performing leadership teams focus their brainpower and resources on what matters to propel the business model forward. The opportunity to improve focus is in every conversation, meeting, document, message, plan, etc. It materializes in solid agendas, an outcome and output orientation, redirecting off-topic conversations to what matters, and prioritizing everything.

A big element of focused problem solving is prioritization . High-performing leadership teams are constantly prioritizing everything in their problem solving. They prioritize the issues they are going to problem solve , the drivers of those issues, the ideas they can pursue, and the solutions that will drive the most value .

Focus is hard. It takes a ton of discipline. Not only do we all need to focus problem-solving on the right things, but we also need to focus people or teams on being efficient through problem-solving. As a leadership team improves its focus on what matters, its efficiency and effectiveness dramatically improve on its journey to creating a leading business model.

How we frame problems is how we will solve those problems. Anything you or your team solve necessitates a framework to solve it. Frameworks are everywhere. They are in the school textbooks, best practices and methodologies we use in our work, the approach we take to solving a problem, and what you are currently reading is a framework for developing a high-performing leadership team.

Low-performing leadership teams struggle to frame problems and solutions correctly and, in turn, struggle with problem-solving. The leaders rely too heavily on their functional lens. They can't elevate or change perspective to see things through other, more appropriate lenses, creating inherent conflict since most bold strategies necessitate give and take from various functions. They don't frame things from the customers' perspective enough, or the implications to the business model, or are too myopic.

High-performing teams use the correct framing and framework(s) to solve their problems. They constantly take a step back to deliberate and figure out how best to frame and approach a problem, understanding that the right approach will elegantly unlock robust solutions. The leaders of high-performing teams understand they must mature their framing beyond the methods they rely on in their functional roles as CFOs, COOs, CMOs, CROs, etc., and can't just be a hammer where everything looks like a nail. They must collaboratively determine the best approach for the problem at hand. This framing maturity of high-performing teams elevates the effectiveness and efficiency of their problem solving.

Focus and framing provide structure and context for problem solving. Still, the hard work is the logic necessary to diagnose issues, ideate solutions properly, decide on the right path, and develop effective plans. The realm of logic is where leadership teams spend a considerable amount of their time in problem solving. Logic includes breaking things down, creating hypotheses , proving or disproving those hypotheses through deduction , induction , analysis, researching, organizing, and thinking through second and third-order implications. Our logic is our problem-solving DNA prevalent within our argumentation, writing, presentations, work product, discussions, meetings, and brainstorming sessions. One of the reasons why there are so many Ph.D. scientists at McKinsey (a little-known fact) is that they are masters of sound and profound logic. And, instead of applying their logical skill set towards furthering scientific research and discovery, they get to use it in business and strategy.

Logic is a tricky competency to evolve for a lower-performing leadership team. You can coach individuals and groups a bit up the maturity ladder through directive coaching on breaking down problems using a hypothesis tree , generating hypotheses, structuring and executing strong analyses and research, creating storylines and presentations using the Minto Pyramid Principle, utilizing prioritization matrices in decision-making, and training on logic, problem solving and analytics, but often you are fighting an uphill battle of trying to change people's engrained way of solving things built over their life. Their logic has gotten them far in their career, so why change now? CEOs in this situation often must replace one or two weaker performers with A-logic players, which creates a step-function improvement in the overall logic maturity of the team.

4. CREATIVE IDEATION

Creative ideation is when the rubber meets the road in problem solving, during which great ideas and strategies percolate from our minds. You can focus on the right things, frame things correctly, and have sound logic, but if you and your team lack the creativity and struggle to connect the dots to ideate elegant solutions, it's all for not. Many people take the first idea that pops into their head and run with it, which is suboptimal and not conducive to growing the competency of ideation. Strong performers and top leadership teams spend the necessary time, effort, and mental energy expanding their option set of ideas and intellectually massaging those to a better state. I can't count the number of brainstorming sessions I've been in where the team pushes and often struggles through their problem solving until finally, the real creative and elegant solution emerges. The smiles and confidence created from these eureka moments give me much joy and satisfaction.

Maturing a leadership team's ability to be creative is easier than it may seem. However, foundational Management Maturity Model conditions will accelerate this maturity by having the right team and composition, a growth , value, and team mindset , strong governance , focused agendas, trust built through communication and collaboration norms, and high expectations . Management teams who complement each other in experience and skills with a collaborative team and growth mindset are typically strong at creativity, coming up with various differing ideas, and building on each other's ideas. Management teams that periodically meet to ideate their strategy and have built trust through communication and collaboration norms get in the practice they need to improve their ideation. We've all heard the saying, "Don't bring me problems; bring me solutions." The practice ground for people to get better at ideation is the space created when their managers exert this solution-orientation expectation on their team members. I often improve in-session ideation by asking the right questions , reframing things, or focusing the group's cognition on a vital vein of thinking.

It is typically uncomfortable to mature a leadership team's creative ideation because most leaders aren't usually challenged and pushed in their thinking, especially in a group setting. Still, that eureka moment is often just around the corner, waiting to be discovered in someone's mind. I often tell leadership teams to embrace the uncomfortable moments and questions because that is when elegant solutions emerge.

TAKE THE FREE LEADERSHIP TEAM PROBLEM SOLVING ASSESSMENT

The next section of the leadership maturity model, become a high-performing team with personal coaching.

I hope you are enjoying the leadership maturity model. Seeing the rapid improvements leadership teams have realized using the model has been rewarding. As an executive, consultant , and coach, I've worked with many leadership teams over my 25+ year career. If you want to take your leadership team to the next level, I encourage you to learn more about my background and reach out or set up some time if you think there is a fit. We'll work together to develop your team into a high-performing leadership team and your business into a market leader.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

A Framework for Leaders Facing Difficult Decisions

- Eric Pliner

Five sets of questions to help guide you.

Many traditional decision-making tools fall short when it comes to the complex, subjective decisions that today’s leaders face every day. In this piece, the author provides a simple framework to help guide leaders through these difficult decisions. By interrogating the ethics (what is viewed as acceptable in your organization or society), morals (your internal sense of right and wrong), and responsibilities associated with your specific role, you can begin to understand how different courses of action align with these different values, and make informed decisions when they inevitably come into conflict. While there are no easy answers, proactively thinking about your decisions through these three distinct lenses — and recognizing where your past actions may have been inconsistent with these values — is the key to leading with integrity.

Many decision-making frameworks aim to help leaders use objective information to mitigate bias , operate under time pressure , or leverage data . But these frameworks tend to fall short when it comes to decisions based on subjective information sources that suggest conflicting courses of action. And most complex decisions fall into this category.

- EP Eric Pliner is the CEO of YSC Consulting.

Partner Center

- Creating Environments Conducive to Social Interaction

- Thinking Ethically: A Framework for Moral Decision Making

- Developing a Positive Climate with Trust and Respect

- Developing Self-Esteem, Confidence, Resiliency, and Mindset

- Developing Ability to Consider Different Perspectives

- Developing Tools and Techniques Useful in Social Problem-Solving

Leadership Problem-Solving Model

- A Problem-Solving Model for Improving Student Achievement

- Six-Step Problem-Solving Model

- Hurson’s Productive Thinking Model: Solving Problems Creatively

- The Power of Storytelling and Play

- Creative Documentation & Assessment

- Materials for Use in Creating “Third Party” Solution Scenarios

- Resources for Connecting Schools to Communities

- Resources for Enabling Students

Weblink: Problem-Solving Model from Reflective Leadership Summit Analysis 2015

This problem-solving model has the following basic elements:

1. Define the issue(s) . (Very important! Sometimes just getting to the bottom of what the problem actually is saves much time and effort!)

2. Analyze the data . (What do we know about the problem so far? Whom does this problem affect?)

3. Generate alternatives . (Gathering solution ideas from oneself and others!)

4. Select decision criteria . (What things will guide our choice(s) from the possible solutions generated?)

5. Analyze and evaluate alternatives .

6. Select the preferred alternative(s) . (It is very important to note that if one solution doesn’t work, we can move on to try other solutions. Never give up! If Plan A doesn’t work, we can move on to Plan B or Plan C!) (Sometimes more than one solution can happen simultaneously!)

7. Develop an action/implementation plan . (The plan should be specific, measurable, and accountable. Resources and time frame should be established.)

Here is a PowerPoint on this leadership model which was created by Tessa McDonnell for a Leadership Summit for Child Care Aware, NH:

Problem-Solving Model from Reflective Leadership Summit Analysis-2015

- Author Rights

- Diversity, Equity & Inclusion

- JOLE 2023 Special Issue

- Editorial Staff

- 20th Anniversary Issue

- Addressing Complex Challenges through Adaptive Leadership: A Promising Approach to Collaborative Problem Solving

Tenneisha Nelson, Vicki Squires DOI: 10.12806/V16/I4/T2

Introduction

Leadership plays a vital role in facilitating the development of effective and innovative schools and educational systems that promote quality teaching and learning (Dinham, 2005; Leithwood, 2007). The environment within which educational leaders operate is dynamic and continues to change in response to external pressures and societal changes. This dynamic environment manifests itself in an ever increasing demand from stakeholders for improved performance in the operations of educational institutions. Robertson and Webber (2002) stated that “educational leaders today are compelled to practice in complex politicized diverse conditions to a greater degree than ever in the history of education” (p. 520). Given these conditions, Ingleton (2013) argued that leaders needed to be even more creative and innovative. Leadership in education then plays a key role in navigating the ever changing environment. When describing school leadership, for example, Kelly and Peterson (2002) pointed out that “in educational administration the range of problems that present themselves is also large, but procedures for solving them tend to be less routinized and unique problems present themselves much more frequently” (p. 364). Owens and Valesky (2007) posited that there is a growing body of literature which addresses the need to find new and better ways to lead under these unstable and unpredictable conditions. In offering a solution to this quandary, Heifetz and Linsky (2004) proffered that, given this complex environment, educators need to embrace the practice of adaptive leadership.

In this conceptual paper, we seek to present a compelling case for the infusion of adaptive leadership practices within all levels of educational systems. We first examine several of the well-known leadership theories, including the limitations of these theories, and then pay particular attention to adjectival and situational theories in an effort to contextualize adaptive leadership practices as a means of responding to the challenges being faced in today’s educational environment. We then describe the model in more detail and illustrate its potential impact in educational settings. Finally, we identify implications that the application of this type of leadership may have on educational institutions, including primary, secondary, and tertiary education.

Understanding leadership. The concept of leadership continues to be a central focus of study in academic fields. For example, Heifetz, Kania, and Kramer (2004) suggested that leadership is “the activity of mobilizing people to tackle the toughest problems and do the adaptive work necessary to achieve progress” (p. 24). On the other hand, Gardner (1990) defined leadership as “the process of persuasion or example by which an individual (or leadership team) induces a group to pursue objectives held by the leader or shared by the leader and his or her followers” (p. 17), and furthermore, indicated that leaders are situated within a particular historic context, a particular setting, and a particular system. Gardner (1990) pointed out that leaders are essential to the organization and perform activities that are integral for the group to accomplish its purposes. Given its importance to organizational effectiveness, Leithwood (2007) suggested that leadership significantly impacts the quality of the school organization and student learning. He further contended that talented leadership in schools is connected with improvements in student achievement. Given the importance of leadership in organizations, it is not surprising that there have been numerous theories advanced, especially within the last few decades.

The Evolution of Leadership Theories and Practices. The area of leadership research continues to evolve, as studies unearth more about the concept and as social and political contexts change. Leadership theories, generally, and more specifically their applications in the field of education have undergone a significant shift over time. According to Leithwood, Jantzi, and Steinbach (1999), “there is much yet to be learned about leadership, the different forms it can take and the effects of these forms” (p. 6). The following section examines several leadership theories that have been advanced in the literature on educational administration.

Leadership research has traditionally focused on one aspect of leadership or variables that influence leadership (Chance, 2009). Some theories focus on the agency of the leader and his or her role in transforming the organization. Other theories examine the environment and the systems that enable leadership. These descriptions of leadership are highly contextual, being linked to the industrial and post-industrial time period in which they were advanced and thus, are somewhat outdated given the current climate within which educational organizations operate. These theories include trait theories, behavioural theories, as well as situational theories of leadership.

Trait based theories of leadership . With the aim of finding out what makes certain individuals great leaders, this approach to the study of leadership is influenced by the Great Man Theory, which implies that “leadership is reserved for only the gifted few” (Northouse, 2013, p. 47). Premised on the assumption that traits can predict the likelihood of an individual attaining a leadership position and being effective in the role, attention is paid to traits such as abilities, physical and personality characteristics and how they differ between leaders and non-leaders. In his review of 124 trait studies undertaken between 1904 and 1947, Stogdill (1948) sought to compile a comprehensive list of universal traits related to successful leadership. The results of this review outlined several leadership traits that distinguished a leader from a non-leader in a group; among these traits are initiative, persistence, self-confidence, knowing how to get things done, adaptability and sociability. While initial research seemed to suggest a range of inheritable traits, later work by researchers such as Zacarro (2007) purported that a range of individual characteristics supported effective leadership and combinations of these traits and attributes needed to be considered within the situation itself. However, continuing critiques of trait based leadership theories include the lack of a definitive identification of which traits contribute to leadership effectiveness and leadership outcomes,

Behavior based theories of leadership. This approach to leadership investigates behaviours enacted by leaders and how these behaviours are reflected in the treatment of followers (Day & Antonakis, 2012). Douglas McGregor (1960), in studying behaviours of leaders in relation to their followers, distinguished between two types of leaders. The distinguishing characteristic between the types is their beliefs and assumptions regarding how people approach work. The behaviour of Theory X leaders reflect their view that the average individual dislikes work and therefore needs to be coerced and controlled for them to work effectively (McGregor, 1960). According to McGregor, the Theory Y leader, on the other hand, sees workers as motivated and happy to work. Therefore this leader will be more participatory in their approach to leadership; their participation, though, presupposes that workers would be allowed to actively participate in organizational decision making. Further work by theorists such as Blake and Mouton (1985) noted the two types of behaviours of leaders: task and relationship. Leaders need to focus their efforts on both areas in order to be the most effective. Continuing critiques of this group of theories include the lack of research that clearly links the types of task and relationship behaviours to positive leadership outcomes, and lack of identification of a style of leadership that is effective across all situations.

Skills theories of leadership . Katz (1955) first identified three broad categories of skills that leaders should exhibit: those aligned with technical skills, human skills, and conceptual skills. Further work by theorists such as Mumford, Zaccaro, Harding, Jacobs, and Fleishman (2000) identified five components of leadership skills: competencies, individual attributes, leadership outcomes, career experiences, and environmental influences. Furthermore, the components of their skills model was further categorized into discrete abilities and skills. Because this model was developed based on military organizations (Mumford, et al., 2000), criticisms of this model include the lack of research and application to other organizations. Additionally, several of the components are reliant on traits, such as cognitive ability, and the theory does not provide insight into leadership development and the translation of some of these skills into leader effectiveness.

Situational theories of leadership. A recognized limitation of theories focusing on skills, traits, and behaviours is the influence of context on leadership. Hersey and Blanchard (1969) and subsequently over the following decades, Blanchard and his associates developed a situational leadership model. Within this model, the directive and supportive elements of strong leadership are described, but there is a recognition that these elements need to be examined within the particular context or situation (Blanchard, Zigarmi, & Zigarmi, 2013). Moreover, Blanchard and his associates developed a series of questionnaires to measure situational leadership. This very prescriptive approach has been critiqued because of the lack of theoretical underpinnings of the approach, the lack of research regarding application, and the lack of examination of the dynamics between approaches to leadership and the followers’ development level (Northouse, 2013).

Transformational and transactional leadership. As research on leadership developed, other theories emerged as scholars sought to examine the effectiveness of leadership by looking at the ways in which leadership can transform organizations (Chance, 2009). Burns (1978), in his seminal work, focused on two types of leader-follower relationships, namely transactional and transformational leadership. The transactional leader influences followers through the “exchange of valued things” (Burns, 1978, p. 20). On the other hand, a transformational leader encourages “an engagement between leaders and followers bound by a common purpose where leaders and followers raise one another to higher levels of motivation and morality” (p. 20). In comparing the two styles, the transformational leader is considered the ideal state of leadership. However, the theory has been criticized for its focus on traits, and the role traits such as charisma play on elements such as followership; reliance on traits rather than behaviours suggests that leadership cannot be learned, Further criticism can be levied around the underlying idea of the heroic leader who inspires other to follow an inspirational vision, and enact change in the organization.

Distributed leadership. A more recent model of leadership that has been advanced is that of distributed leadership. This theory of leadership does not focus on one person as the leader but instead pays attention to the interactions between persons within the organization in an effort to understand leadership. Spillane (2005) outlined that distributed leadership involves interactions of school leaders, followers and their situations, the “interactions among the various leaders in a given situation define leadership practice as individuals play off one another” (p144). There may be positional leadership, but leadership roles are distributed among key stakeholders within the organization. This approach ensures multiple perspectives and leadership styles are incorporated into a working body that has defined roles. A critique of this approach, though, is that it appears to be a way to distribute the work of leadership across the formal and informal leaders of the institution without focusing at the underlying complex issues of the organization. While distributed leadership may engage more members in the organization, and build investment in the advancing of the organizational goals, the model does not focus on the collaborative efforts required for difficult problem-solving.

Inadequacies of Previous Theories. The different leadership theories all play a role in understanding school leadership. The trait and behaviour theories provide only a list of characteristics and behaviours that individuals should possess that may contribute to effective leadership (Chance, 2009), but yet research has yet to uncover an optimal combination for leadership that works effectively in all situations. Examining leadership solely based on traits and behaviours is inadequate since the context within which leaders operate also play an integral role in determining their effectiveness. Moreover, the debate regarding whether leadership is innate or learned is a not a helpful approach to resolving issues of leadership in organizations.

It should be noted that leadership studies that have paid exclusive attention to the actions of the individual leader or administrator and their role in improving the organization tended to attribute the improvements made to the person charged with leading the institution. According to Evers and Lakomski (2013), one of the draw backs of individualism “is that the emphasis on the leader as an individual can both bracket and discount the causal field in which organizational functioning occurs” (p. 164). Spillane (2015) also rejected leader-centric studies in education, suggesting that leadership based on the individual is flawed. Spillane (2015) further argued that individual focused research tends to pay attention to the logistics of leadership rather than the enactment of leadership. Paying attention to not only what individuals do but how they interact within their socio-material environment as they lead (the practice of leadership) should be the focus of any study in leadership. Speaking from his years of studies in political leadership, Cronin (1984) emphasized that leadership is “highly situational and contextual… there is chemistry between leaders and followers which is usually context specific” (p. 23). Ultimately, it is in this context that leadership can be understood, as emphasized by Spillane (2005) who proposed that an examination of leadership practices is key to understanding school leadership.

Attempting to confine leadership to one “key thing” is an activity in futility because there appears to be no one right model that works across all cultures and contexts (Riley & Macbeath, 2002). Gardner (1990) stated that “the issues are too technical and the pace of change too swift to expect that a leader, no matter how gifted will be able to solve personally the major problems facing the system over which he or she presides” (p. 26). Whether it is internationalization pressures, global mobility, economic disparity, competitive recruitment of students, or the pace of technological change, educational leaders need to work together with others in the organization to address the challenges.

In examining school leadership within several contexts Riley and Macbeath (2002) advanced that “leadership can be developed, nurtured and challenged; (it is) not static, leaders do not learn how to do school leadership and then stick to set patterns and ways of doing things” (p. 356). In other words the concept of leadership is evolving as society changes. With this in mind, Heifetz et al. (2004) advanced that leadership is better understood by focusing on what is done instead of focusing on individual attributes. In defining leadership they contended that leadership is the “activity of mobilizing people to tackle the toughest problems and do the adaptive work necessary to achieve progress” (Heifetz, et al., 2004, p. 24). Solving complex current problems requires a leadership style that influences the organization in a way that galvanizes a collaborative response to the problem.

Adaptive leadership. The challenges that educational organizations face today have far reaching implications for the sustainability of the institutions and its members. Challenges include issues such as the best way to implement reform for the mutual benefit of all stakeholders or to overcome deep rooted systemic problems that curtail the successful operation of the organizations. Although Heifetz and his colleagues originally developed the model of adaptive leadership within the context of business, they identified that their model could be applied to educational systems because the problems are complex and multi-faceted. They contended that this model was process and follower oriented that proposed a prescriptive approach to resolving these challenges. In this context Heifetz and Linsky (2007) purported that:

Leadership in education means mobilizing schools, families, and communities to deal with some difficult issues —issues that people often prefer to sweep under the rug. The challenges of student achievement, health, and civic development generate real but thorny opportunities for each of us to demonstrate leadership every day in our roles as parents, teachers, administrators, or citizens in the community. (p. 7).

Owens and Valesky (2009) pointed out that the degree of change or stability in the environment should influence the selection of a strategy for leadership. Principals are problem solvers, who are expected and needed to address and buffer the technical care of the organization the school from the immediate and pressing demands of student’s parents and other short term sources of perturbation in the system (Kelly & Peterson, 2002). Indeed, in taking on this role as problem solvers, Kelly and Peterson (2002) further pointed out that principals are also expected to “work effectively in increasing diverse fragmented and pluralistic communities with vocal stakeholders,” all the while fulfilling their central role of facilitating school reform and improvement (p. 351). With this in mind, leaders are now more than ever required to reframe how leadership is understood and enacted.

Robertson and Webber (2002) called for educational leaders to “move past the practices that were successful in an industrial model of education to address the ambiguity and complexity of working in a rapidly changing, diverse society” (p. 520). There is a need, as outlined by Kelly and Peterson (2002), for principals to have both problem finding and problem solving skills in order to address not only routine challenges, but also unique emergent issues. Bringing attention to the preparation programs for principals, Kelly and Peterson (2002) highlighted the need for these programmes “to address the existing realities —by providing skills, knowledge and experiences that will prepare future principals” (p. 359). In an environment where there are no clear cut solutions for many of the challenges being faced, school leaders need to engage in adaptive leadership techniques. Although researchers of adaptive leadership contend that this approach is applicable to all large organizations, there has been little written on this model within post-secondary education. However, senior administration in universities and colleges are facing many emergent issues as well, including a move away from public funding of post-secondary education to a model of more diversified funding (Austin & Jones, 2016). Indeed, the term of post-secondary presidents are becoming shorter and shorter as the multidimensional tensions on campuses grow (Paul, 2015; Trachtenberg, Kauver, & Bogue, 2013).

Application of Adaptive Leadership in Educational Institutions. Given the complex environment of educational institutions, a more robust model of leadership would be a useful tool to assist leaders of these organizations to navigate this dynamic landscape. Owens and Valesky (2007) have advanced that the “problems facing schools today are adaptive problems…and require adaptive leadership concepts and techniques” (p. 271). In referring to the landscape of post-secondary education Randall and Coakley (2007) indicated that an “outcome of the changing academic environment is the need to challenge models of leadership that focus on the competencies, behaviors, and situational contingencies of individual leaders” (p. 325). Leadership, when seen in this light, requires a learning strategy, a new approach to leadership; “the adaptive demands of our time require leaders who take responsibility without waiting for revelation or request. One can lead with no more than a question in hand” (Heifetz & Laurie, 2011, p. 78). Leaders and organizations need to adapt to the evolving societal and political contexts.

Heifetz (1994) advanced a model of leadership that can equip principals or post- secondary leaders to navigate the challenges common to uncertain educational environments. This model views the problems that school leaders possibly face as either technical or adaptive. According to Owens and Valesky (2007), technical problems are clear and can be solved by applying technical expertise, while adaptive problems are “complex and involve so many ill understood factors that the outcomes of any course of action is unpredictable” (p. 271). A technical challenge is not necessarily quickly resolved; however, the problem is readily understood and the solution is achievable using current policies and practices. On the other hand, an adaptive challenge requires careful examination or diagnosis of the problem itself, followed by actions that may include changes to people’s assumptions, attitudes, and behaviours. A further complication in the diagnosis of the issue may be that the challenge is both technical and adaptive; parts of the solution can be achieved using current practices and resources, whereas other elements of the issue require much more complex approaches.

Heifetz, Grashow, and Linsky (2009) emphasized that diagnosing the problem was a critical step that required considerable time for a thorough evaluation. They cautioned leaders to put aside the pressures to react too quickly to the problem. Proper diagnosis requires a diagnosis of the system, of the problem, and of the political landscape. After this careful and systematic collection of data and related information, the next task is the interpretation of the data (Heifetz et al., 2009). This stage is essential for identifying the technical and adaptive elements of the challenge which then informs decisions with regard to courses of action. The leaders should design interventions that address these challenges adequately with consideration given to the context and available resources. Heifetz et al. (2009) noted that this process involves potential conflict, as the organization moves into a “productive zone of disequilibrium” (Heifetz et al., 2009, p. 30). The solutions are unlikely linear, and introduce times where members need to confront their ideas, beliefs, and behaviours. Leaders of change need to understand that resistance and conflict are an expected part of the process (Heifetz et al., 2009).

In shedding light on adaptive leadership in practice, Heifetz, et al. (2004) shared the experience of three foundations in Pittsburg, United States that faced an adaptive problem. The foundations abruptly suspended their funding to local public schools sending the system into a quandary. This move forced the school board to pay attention to a concern the foundations had repeatedly brought up, which is the manner in which the school district operated. As a result of this bold move, a Mayoral Commission was launched to conduct an independent assessment of the city’s school system. This assessment led to dramatic reforms in the way the school district was governed and operated. According to Heifetz, et al. (2004) many of the problems the district encountered could be traced back to a school board “long paralyzed by intramural conflicts” (p. 22). Using this incident as a case, Heifetz, et al. (2004) advanced that in dealing with adaptive problems getting people to pay attention to a certain issue is the first hurdle. As they explained, this focus was successfully done when the foundations publicly announced the withdrawal of their support of the public schools valued at approximately 12 million dollars.

As illustrated in this example, the second step in the adaptive process involves the generation and maintenance of productive distress. Heifetz, et al. (2004) pointed out that “adaptive problems often take a great deal of time to resolve, with progress coming in fits and starts. The erratic pace often distresses stakeholders” (p. 30). They further added that “the job of adaptive leadership is not to eliminate this stress – and thus reduce the impetus for adaptive solutions – but to harness it, keeping it at a level that motivates change without overwhelming participants” (Heifetz, et al., 2004, p. 30). Fostering an adaptive culture includes managing this conflict and making the process an acceptable part of the organization’s practices.

Framing the issues is the next step in the process, where participants are made aware that difficult problems present opportunities as well as challenges. Mediating the conflict among stakeholders is the final component of the process. According to Heifetz, et al. (2004), “many different people and groups may hold keys to the solutions of complex adaptive problems. But trying to get them all moving in the same direction may result in conflict across racial, cultural, or socioeconomic lines” (p. 30). The members are tasked with mitigating these potential challenges by understanding the necessity of collaborative problem solving even when it is difficult.

It should be noted that “tackling complex adaptive social problems is not easy” (Heifetz, et al, 2004, p. 30), a disclaimer made by the authors. However, given its potential to assist in providing tangible and sustainable responses to the challenges that are evident in an ever- changing educational landscape makes it viable as a leadership process worthy of investigation and application in challenging leadership situations. Engaging in this form of leadership requires a shift from the traditional view of leadership as an “authoritative experience” (Heifetz & Laurie, 2011, p. 58) where leaders are the sole source of authority for solving organizational problems. Arguably, solutions to adaptive problems in schools are not found in the leaders “but in the collective intelligence of employees at all levels, who need to use one another as resources, often across boundaries, and learn their way to those solutions” (Heifetz & Lauire, 2011, p. 58).

The adaptive leadership framework provides a useful means for principals and post- secondary senior administration to navigate the uncertain climate in which schools have to operate. Similar to continuous improvement initiatives in the manufacturing sector where multidisciplinary teams are used to solve unique organizational problems in an effort to move the organization to the next level, this approach can also assist educational leaders to overcome adaptive challenges that threaten their existence. One of the first things this method of intervention emphasized is that leaders do not have all the answers to the problems an organization faces. In adaptive leadership, workable solutions are usually found by engaging those persons who are closest to the problem within the system; they work with the system every day and know what can or cannot work for its improvement. This approach implies that all individuals are treated equally in diagnosing the problem and finding workable solutions. They are thereby given a voice in the organization, and actively participate to ensure its viability. In such a situation the leader’s role is to facilitate the emergence of these solutions, and put processes and systems in place to facilitate their implementation.

While the structure of post-secondary organizations are significantly different from the other educational systems, this type of leadership can also be utilized. Diagnosing the complex system is the first piece of the puzzle; understanding the political landscape is even more challenging with the collegium model of governance and decision making (Austin & Jones, 2016). However, the work of identifying and understanding adaptive challenges is still very relevant. In some cases, solutions could include recrafting of policies and processes which would entail the commitment of necessary stakeholders to make relatively small adjustment to address technical challenges. In other cases, the issues will require interdisciplinary problem solving to generate innovative solutions, such as improving post-secondary outcomes for Indigenous students. Universities and colleges are engaging in interdisciplinary research into global challenges such as food and water security. This collaborative work in research, though, is not extended towards collaborative models of decision making and governance. Rather, universities especially have a reputation for holding onto traditional models and structures (Austin & Jones, 2016). The individualistic and competitive nature of distributing resources across the campus becomes a significant barrier to implementing adaptive leadership more broadly across the campus. Although collegial processes promote multiple levels of input in decision making, those same processes encode a very structured method of addressing change (Austin & Jones, 2016).

Implications for Practice and Research. The model of adaptive leadership was developed as a very practical approach. Because of this genesis, the process includes helpful strategies for addressing challenges. For example, Heifetz et al. (2009) noted the need for engaging in occasional views from the ‘balcony’ where leaders take a step away and examine the broader view of the organization. Furthermore, they suggest developing a ‘holding environment’, where possible solutions are expressed and ideas are discussed in a safe environment. Within this space, leaders manage productive dialogue, ensuring that when conflicts arise, the discussions lead to constructive solutions. It is beyond the scope of this paper to examine all of the tips and tools suggested, but the approach is practical enough for leaders to understand the process.

Because adaptive leadership was developed for use by leaders in the field, the conceptual underpinnings of the model need further research and development (Northouse, 2016). The relationality of the different elements needs to be refined, including better describing some of the more abstract elements. An additional critique is that the strategies are too wide-ranging and sometimes too abstract; this plethora of helpful tools and tips could lead to confusion (Northouse, 2016). Perhaps by trying to be a model that could apply to the complex realities of many types of contemporary organizations, too many elements were introduced. Further articulation of the model may resolve this issue.

Although Heifetz introduced this model over two decades ago, there has been limited adoption of the model across different types of large organizations (Northouse, 2016). Each organization has unique structures and challenges, and as noted earlier in the paper, the evolving complexities of current organizations require different problem solving approaches. However, to date, there exists very little empirical research demonstrating the effective implementation of this leadership process (Dugan, 2017; Northouse, 2016). The assumptions and ideas upon which this model is built need to be further evaluated. A body of evidence generated by research would be beneficial not only for validating the theory but also for promoting further adoption of the model across large organizations.

This body of research could possibly address the critiques of the theory as outlined by Dugan (2017). Dugan agreed that there is not enough empirical research on the adaptive leadership model. More problematic, according to Dugan is the commodification of workers. Dugan (2017) described commodification as “the extent to which workers are considered fully agentic, vested partners in the process of production or simply tools to augment it” (p. 141).

Dugan contended that the theory further reinforces the power dynamics of the organization, and can lead to workers becoming dependent on the direction of the leader or reacting to the leader’s agenda, rather than working collaboratively to explore issues. Furthermore, the theory supports conflict and disequilibrium, but that kind of environment needs to be safe. Resistors to the process may be penalized socially or economically for their viewpoints, even though the theory identifies the idea of a holding environment to explore issues safely. The question of whether the process is guided by manipulation to achieve predetermined goals of the leader or by authentic efforts at collaboration to resolve complex issues needs to be resolved.

There is no disputing that the adaptive leadership process “is uncomfortable, as it challenges our most deeply held beliefs and suggests that deeply held values are losing relevance, bringing to the surface legitimate but competing perspectives or commitments” (Australian Public Service Commission, 2011, p. 14). As pointed out by Heifetz and Linsky (2004), it is important that educational leaders at all levels exercise adaptive leadership to allow those perspectives to come to the fore. The multiple and sometimes competing viewpoints and ideas are required to examine complex issues from new angles.

Moving away from the adjectival descriptors, behaviours, and situational contexts within which leaders have to operate, adaptive leadership provides an alternative approach that focuses on diagnosing the complex issues and collaboratively exploring the technical and adaptive elements embedded in the problems in order to construct an appropriate response. The adaptive leadership framework offers a unique means by which to conceptualize and sustainably address the unique challenges facing educational institutions today.

Austin, I., & Jones, G. A. (2016). Governance of higher education: Global perspectives, theories and practices . New York: Routledge.

Australian Public Service Commission. (2011). Thinking about leadership a brief history of leadership thought . Retriveied from Australian Public Service Commission website: http://www.apsc.gov.au/publications-and-media/current-publications/thinking-about- leadership-a-brief-history-of-leadership-thought

Blake, R. R., & Mouton, J. S. (1985). The managerial grid III. Houston, TX: Gulf Publishing Company.

Blanchard, K. H., Zigarmi, D., & Zigarmi, P. (2013). Leadership and the One Minute Manager: Increasing effectiveness through situational leadership . New York: William Morrow.

Burns, J. M. (1978). Leadership . New York: Harper & Row.

Chance, P. L. (2009). Introduction to educational leadership and organizational behaviour: Theory into practice .(2nd ed.). Larchmont, NY: Eye on Education.

Cronin, T. E. (1984). Thinking and learning about leadership. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 14 (1), 22–34. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/27550029

Day, D., & Antonakis, J. (2012). The nature of leadership . SAGE Publications. Retrieved from: https://serval.unil.ch/resource/serval:BIB_E24FFBFEBE58.P001/REF

Dinham, S. (2005). Principal leadership for outstanding educational outcomes. Journal of Educational Adminsitration, 43 (4), 338-356. DOI: 10.1108/09578230510605405

Dugan, J. P. (2017). Leadership theory: Cultivating critical perspectives . Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Evers, C, & Lakomski, G. (2013). Methodological individualism, educational adminsitration and leadership . Journal of Educational Adminsitration and History, 45 (2), 159-173. DOI: 10.1080/00220620.2013.768969

Gardner, J. (1990). The nature of leadership. In The Jossey-Bass Reader on Educational Leadership (pp. 17-26). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Heifetz, R. A. (1994). Leadership without easy answers . Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

Heifetz, R. A., Grashow, A., & Linsky, M. (2009). The practice of adaptive leadership:Tools and tactics for changing your organization and the world . Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press.

Heifetz, R., Kania, J., & Kramer., M. (2004). Leading boldly. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 21 – 31 . Retrieved from: http://ssireview.com

Heifetz, R. A.., & Laurie, D. (2011). The work of leadership. In HBR’s 10 Must Reads: On Leadership , (pp. 57-78). Retrieved from: http://thequalitycoach.com/wp- content/uploads/2013/05/hbr-10-must-reads-on-leadership-1.pdf

Heifetz, R., & Linsky, M. (2004). When leadership spells danger. Educational Leadership ; 61 (7), 33 – 37.

Hersey, P., & Blanchard, K. H. (1969). Life-cycle theory of leadership. Training and Development Journal, 23 , 26-34.

Ingleton, T. (2013). College student leadership development: Transformational leadership as a theoretical foundation. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 3 , 219 – 229. DOI: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v3-i7/28

Katz, R. L. (1955). Skills of an effective administrator. Harvard Business Review, 33 (1), 33 – 42.

Kelley, C., & Peterson, K. (2002). The work of principals and their preparation: Addressing critical needs for the twenty-first century. In The Jossey-Bass Reader on Educational Leadership (pp. 351-401). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Leithwood, K. (2007). What we know about educational leadership. In C. F. Webber, J. Burger, & P. Klinck, P. (Eds), Intelligent leadership: Constructs for thinking education leaders, 6 , 41-66. Springer Science & Business Media.

Leithwood K., Jantzi D., & Steinbach, R. (1999). Changing leadership for changing times. Suffolk: Open University Press.

McGregor, D. (1960). The human side of enterprise . New York: McGraw Hill.

Mumford, M. D., Zaccaro, S. J., Harding, F. D., Jacobs, T. O., & Fleishman, E. A. (2000). Leadership skills for a changing world: Solving complex social problems. The Leadership Quarterly , 11 (1), 11-35.

Northouse, P. (2013). Leadership: Theory and practice (6th ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Northouse, P. (2016). Leadership: Theory and practice (7th ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Owens, R. G., & Valesky, T. C. (2014). Organizational behavior in education: Leadership and school reform (11th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Paul, R. H. (2015). Leadership under fire: the challenging role of the Canadian university president . McGill-Queen’s Press-MQUP.

Randall, L., & Coakley, L. (2007). Applying adaptive leadership to successful change initiatives in academia. Leadership & Organization Development Journal. 28 (4), pp. 325-335 . Doi.org/10.1108/01437730710752201

Riley, K., & Macbeath, J. (2002). Leadership in diverse contexts and cultures. In Leithwood, & P. Hallinger, (Eds.), Second International Handbook of Educational Leadership and Administration, (pp. 351-358). Kluwer, Netherlands: Springer.

Robertson, J. M., & Webber, C. F. (2002). Boundary-breaking leadership: A must for tomorrow’s learning communities. In K. Leithwood, & P. Hallinger (Eds.), Second International Handbook of Educational Leadership and Administration (pp. 519-553). Kluwer, Netherlands: Springer.

Spillane, J. (2005). Distributed leadership. The Educatonal Forum , 69 (2), 143-150. DOI: 10.1080/00131720508984678

Stogdill, R. (1948). Personal factors associated with leadershiop:A survey of the literature. The Journal of Psychology, 25 (1), 35-71.

Trachtenberg, S. J., Kauvar, G. B., & Bogue, E. G. (2013). Presidencies derailed: Why university leaders fail and how to prevent it . Baltimore, ML: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Author Biographies

Tenneisha Nelson is a Doctoral Candidate in the Department of Educational Administration, College of Education, University of Saskatchewan. Her areas of research are leadership theory, school leadership and the principalship, as well as rural education.

Vicki Squires, PhD, is an Assistant Professor, Department of Educational Administration, College of Education, University of Saskatchewan. Her areas of research are post-secondary education and student well-being, including an examination of how all stakeholder groups can achieve their goals while working together to achieve the mission of the university

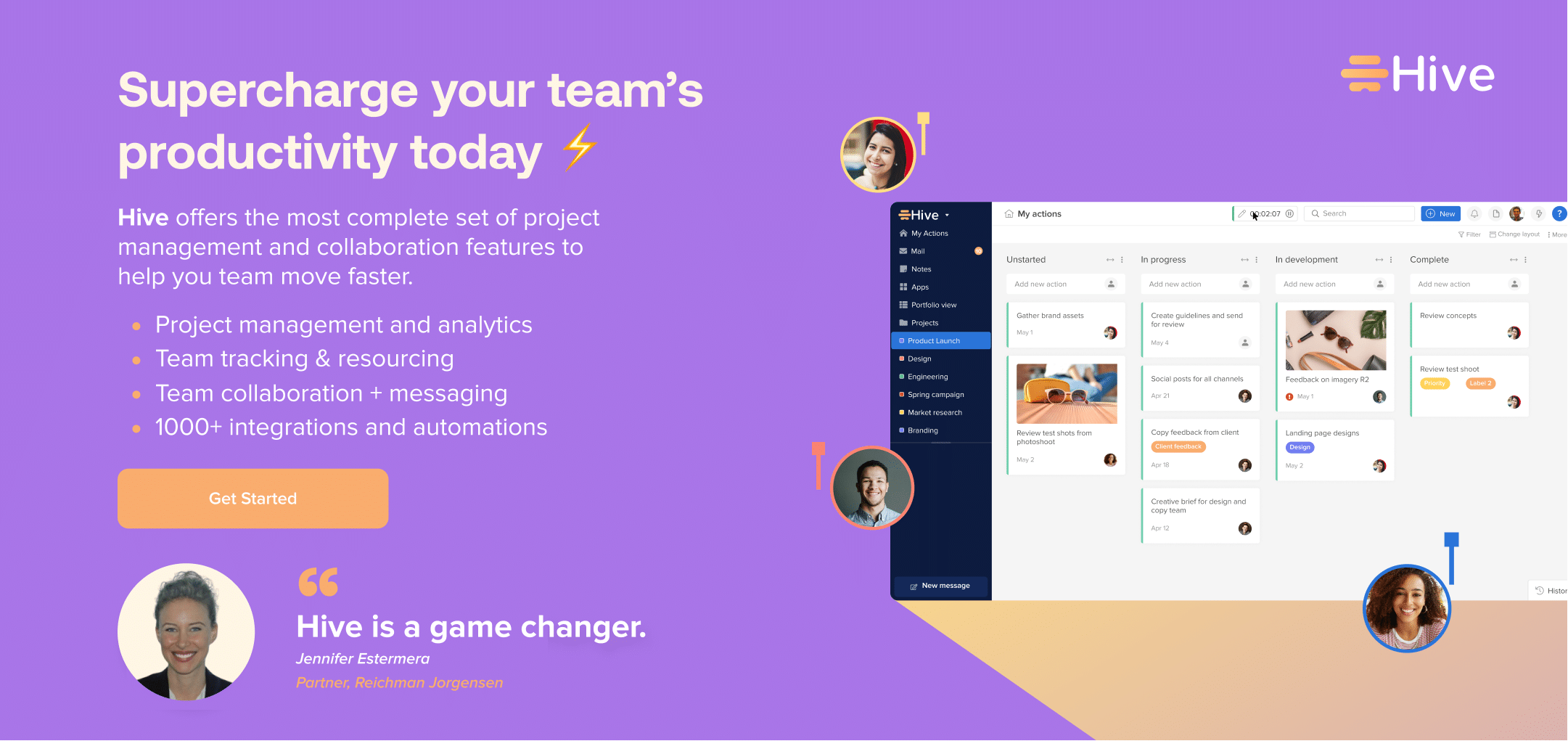

- Project management Track your team’s tasks and projects in Hive

- Time tracking Automatically track time spent on Hive actions

- Goals Set and visualize your most important milestones

- Collaboration & messaging Connect with your team from anywhere

- Forms Gather feedback, project intake, client requests and more

- Proofing & Approvals Streamline design and feedback workflows in Hive

- See all features

- Analytics Gain visibility and gather insights into your projects

- Automations Save time by automating everyday tasks

- Hive Apps Connect dozens of apps to streamline work from anywhere

- Integrations Sync Hive with your most-used external apps

- Templates Quick-start your work in Hive with pre-built templates

- Download Hive Access your workspace on desktop or mobile

- Project management Streamline initiatives of any size & customize your workflow by project

- Resource management Enable seamless resourcing and allocation across your team

- Project planning Track and plan all upcoming projects in one central location

- Time tracking Consolidate all time tracking and task management in Hive

- Cross-company collaboration Unite team goals across your organization

- Client engagement Build custom client portals and dashboards for external use

- All use cases

- Enterprise Bring your organization into one unified platform

- Agency Streamline project intake, project execution, and client comms

- University Marketing Maximize value from your marketing and admissions workflows with Hive

- Nonprofits Seamless planning, fundraising, event execution and more

- Marketing Streamline your marketing projects and timelines

- Business operations Track and optimize strategic planning and finance initiatives

- Education Bring your institutions’ planning, fundraising, and more into Hive

- Design Use Hive to map out and track all design initiatives and assets

- On-demand demo Access a guided walk through Hive

- Customers More on how Teams are using Hive now

- FAQ & support articles Find answers to your most asked questions

- Hive University Become a Hive expert with our free Hive U courses

- Webinars Learn about Hive’s latest features

- Hive Community Where members discuss and answer questions in the community

- Professional Services Get hands-on help from our Professional Services team

- Hive Partners Explore partners services or join as a partner

- FEATURED WEBINAR

Simplifying University Marketing Workflows in Hive

In this webinar, Brooke will detail her end-to-end intake process, workflow, and organizational system for tracking marketing assets and projects in Hive.

- Request Demo