Short Research Report

Carrying out a particular research means adding existing knowledge. When you do some research, document all the processes you have taken. Consider taking note of the findings too. Research reports are commonly used to present a particular topic which focuses on the communication of the relevant information. It is made to convey details pertaining to marketers to implement a new strategic plan .

With the use of research reports, you will be able to share facts, events and other details based on an incident. It will become easier to outline your findings from an investigation and anything that requires inquiry. It is best to know how to make or create a detailed and specific report that proves useful all throughout the research process.

3+ Short Research Report Examples

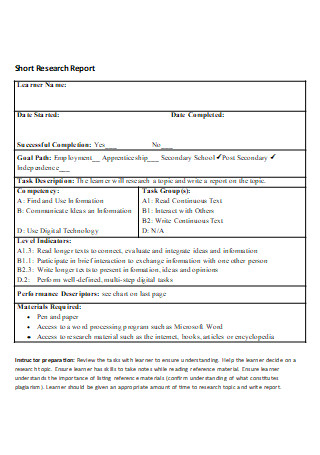

1. short research report template.

Size: 120 KB

2. Basic Short Research Report

Size: 29 KB

3. General Short Research Report

Size: 342 KB

4. Short Research Assessment Report

Size: 61 KB

Short Research Report Definition

A research report is a type of document that gives you an outline of the processes, data and findings based on an investigation. It is considered as a first-hand account in research that needs to be properly written, objective and accurate. This may be a summary of the research process that presents findings, recommendation and other relevant matters regarding the report subject. This time, the length differs. It has to be short.

Features of a Research Report

How can you be able to identify that what you are reading is a research report?

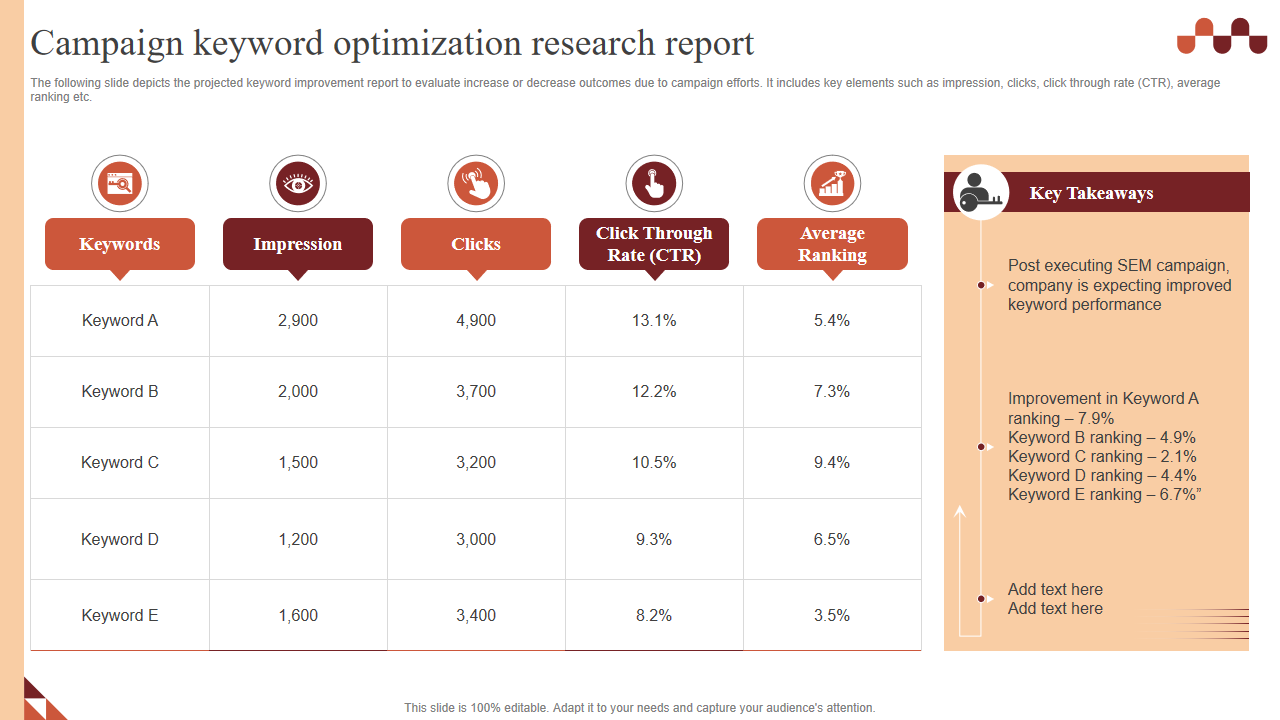

1. It gives a very detailed presentation of the overall research process and findings. It may even use graphic organizers such as tables, charts or graph.

2. It is written formally.

3. It is written in third person.

4. It is highly informative.

5. It has organized structures that uses bullet points, headings, subheadings and sections.

6. It presents recommendations.

Types of Research Report

There are two types of research report: qualitative research report and quantitative research report .

Qualitative Research Report

This type of research report outlines the processes, methods and findings. In academic research, a qualitative research report gives an opportunity to apply one’s learnings and skills in planning and implementing a particular qualitative research projects. Qualitative is descriptive. Aside from having the details of the research process itself, might as well consider giving descriptions by narrating a specific information.

Quantitative Research Report

This type of research report focuses on the numbers and statistics that aids in finding answers to its research questions. The researcher maybe able to present a quantitative data that supports the process. Unlike qualitative research that focuses on describing an information, a quantitative gives importance to numerical values.

Importance of Research Report

1. Knowledge

One of the reasons why conducting research is beneficial because it contributes knowledge. A research report is a tool that can be used to communicate the findings of an investigation.

2. Identifies gaps

Research reports allow you to identify gaps that can be used for further inquiries. This type of report shows what was already done while helping other areas that needs systematic investigation.

Tips for Writing Research Reports

1. Be prepared before you start writing about your topic

Choose the topic that interests you. You should consider your readers too. One of the most difficult thing is when you ask yourself as to how you should be able to start the writing process. Know what could be your title first then make an introduction. Once you have the information, you can write for a conclusion.

2. You should have a clear research objective

Always make sure that the data is in lined with the objectives. Do not speculate. Speculations are only made for conversations, not research reports.

3. Check grammar and spelling

It is advisable to use verbs in the present tense. This will make your research report sound more immediate.

4. Discuss only what is important

If you find some data irrelevant, do not take much of your time to include them in your research report.

5. Include graphs

The graphs will help your readers understand your data. However, you should label your graphs properly to avoid confusion. They should have proper indications, sample, and correct wording.

Does a research report requires an executive summary

Yes. An executive summary , also known as the abstract, summarizes your report to make the readers more acquainted without the need to read it all.

What is a good research report?

A good research report has to be accurate with the information it is presenting. It must be incorporated with its objectives and its conclusion. It must follow the correct structure and most of all, it must be written clearly.

What are the main contents of research report?

Most research reports contain a title page, abstract, introduction, methodology, results and discussion, references, appendix and an author’s note.

Always remember that in making a research report, you must be able to create a very concise document that summarizes all the research process. It is necessary just like when you are conducting a systematic investigation. It allows you to communicate with the use of the research findings. Consider your readers as well. This will help you adjust to the right tone for your report.

Report Generator

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

Generate a report on the impact of technology in the classroom on student learning outcomes

Prepare a report analyzing the trends in student participation in sports and arts programs over the last five years at your school.

8+ SAMPLE Short Research Report in PDF | MS Word

Short research report | ms word, 8+ sample short research report, what is a short research report, what are the characteristics of short research report, how to write a short research report, types of research report, technical report, popular report, what characteristics distinguish good and successful report writing, is a short and long report different, why use a short research report, how can you write a good short research report, how many pages is a short research report.

Short Research Report Template

Short Term Research Report

Lab Short Research Report

Short Action Research Report

Standard Short Research Report

Short Research Report Example

Basic Short Research Report

Short Research Report in DOC

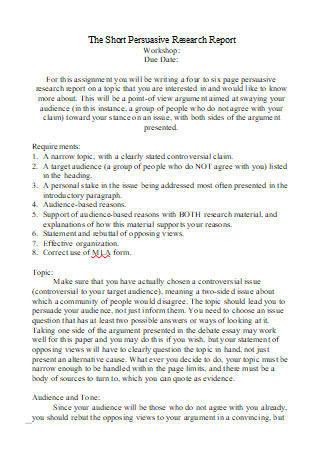

Short Persuasive Research Report

Share this post on your network, file formats, word templates, google docs templates, excel templates, powerpoint templates, google sheets templates, google slides templates, pdf templates, publisher templates, psd templates, indesign templates, illustrator templates, pages templates, keynote templates, numbers templates, outlook templates, you may also like these articles, 12+ sample construction daily report in ms word | pdf.

Introducing our comprehensive sample Construction Daily Report the cornerstone of effective project management in the construction industry. With this easy-to-use report, you'll gain valuable insights into daily activities report,…

25+ SAMPLE Food Safety Reports in PDF | MS Word

Proper food handling ensures that the food we intake is clean and safe. If not, then we expose ourselves to illnesses and food poisoning. Which is why a thorough…

browse by categories

- Questionnaire

- Description

- Reconciliation

- Certificate

- Spreadsheet

Information

- privacy policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Research Report – Example, Writing Guide and Types

Research Report – Example, Writing Guide and Types

Table of Contents

Research Report

Definition:

Research Report is a written document that presents the results of a research project or study, including the research question, methodology, results, and conclusions, in a clear and objective manner.

The purpose of a research report is to communicate the findings of the research to the intended audience, which could be other researchers, stakeholders, or the general public.

Components of Research Report

Components of Research Report are as follows:

Introduction

The introduction sets the stage for the research report and provides a brief overview of the research question or problem being investigated. It should include a clear statement of the purpose of the study and its significance or relevance to the field of research. It may also provide background information or a literature review to help contextualize the research.

Literature Review

The literature review provides a critical analysis and synthesis of the existing research and scholarship relevant to the research question or problem. It should identify the gaps, inconsistencies, and contradictions in the literature and show how the current study addresses these issues. The literature review also establishes the theoretical framework or conceptual model that guides the research.

Methodology

The methodology section describes the research design, methods, and procedures used to collect and analyze data. It should include information on the sample or participants, data collection instruments, data collection procedures, and data analysis techniques. The methodology should be clear and detailed enough to allow other researchers to replicate the study.

The results section presents the findings of the study in a clear and objective manner. It should provide a detailed description of the data and statistics used to answer the research question or test the hypothesis. Tables, graphs, and figures may be included to help visualize the data and illustrate the key findings.

The discussion section interprets the results of the study and explains their significance or relevance to the research question or problem. It should also compare the current findings with those of previous studies and identify the implications for future research or practice. The discussion should be based on the results presented in the previous section and should avoid speculation or unfounded conclusions.

The conclusion summarizes the key findings of the study and restates the main argument or thesis presented in the introduction. It should also provide a brief overview of the contributions of the study to the field of research and the implications for practice or policy.

The references section lists all the sources cited in the research report, following a specific citation style, such as APA or MLA.

The appendices section includes any additional material, such as data tables, figures, or instruments used in the study, that could not be included in the main text due to space limitations.

Types of Research Report

Types of Research Report are as follows:

Thesis is a type of research report. A thesis is a long-form research document that presents the findings and conclusions of an original research study conducted by a student as part of a graduate or postgraduate program. It is typically written by a student pursuing a higher degree, such as a Master’s or Doctoral degree, although it can also be written by researchers or scholars in other fields.

Research Paper

Research paper is a type of research report. A research paper is a document that presents the results of a research study or investigation. Research papers can be written in a variety of fields, including science, social science, humanities, and business. They typically follow a standard format that includes an introduction, literature review, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion sections.

Technical Report

A technical report is a detailed report that provides information about a specific technical or scientific problem or project. Technical reports are often used in engineering, science, and other technical fields to document research and development work.

Progress Report

A progress report provides an update on the progress of a research project or program over a specific period of time. Progress reports are typically used to communicate the status of a project to stakeholders, funders, or project managers.

Feasibility Report

A feasibility report assesses the feasibility of a proposed project or plan, providing an analysis of the potential risks, benefits, and costs associated with the project. Feasibility reports are often used in business, engineering, and other fields to determine the viability of a project before it is undertaken.

Field Report

A field report documents observations and findings from fieldwork, which is research conducted in the natural environment or setting. Field reports are often used in anthropology, ecology, and other social and natural sciences.

Experimental Report

An experimental report documents the results of a scientific experiment, including the hypothesis, methods, results, and conclusions. Experimental reports are often used in biology, chemistry, and other sciences to communicate the results of laboratory experiments.

Case Study Report

A case study report provides an in-depth analysis of a specific case or situation, often used in psychology, social work, and other fields to document and understand complex cases or phenomena.

Literature Review Report

A literature review report synthesizes and summarizes existing research on a specific topic, providing an overview of the current state of knowledge on the subject. Literature review reports are often used in social sciences, education, and other fields to identify gaps in the literature and guide future research.

Research Report Example

Following is a Research Report Example sample for Students:

Title: The Impact of Social Media on Academic Performance among High School Students

This study aims to investigate the relationship between social media use and academic performance among high school students. The study utilized a quantitative research design, which involved a survey questionnaire administered to a sample of 200 high school students. The findings indicate that there is a negative correlation between social media use and academic performance, suggesting that excessive social media use can lead to poor academic performance among high school students. The results of this study have important implications for educators, parents, and policymakers, as they highlight the need for strategies that can help students balance their social media use and academic responsibilities.

Introduction:

Social media has become an integral part of the lives of high school students. With the widespread use of social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat, students can connect with friends, share photos and videos, and engage in discussions on a range of topics. While social media offers many benefits, concerns have been raised about its impact on academic performance. Many studies have found a negative correlation between social media use and academic performance among high school students (Kirschner & Karpinski, 2010; Paul, Baker, & Cochran, 2012).

Given the growing importance of social media in the lives of high school students, it is important to investigate its impact on academic performance. This study aims to address this gap by examining the relationship between social media use and academic performance among high school students.

Methodology:

The study utilized a quantitative research design, which involved a survey questionnaire administered to a sample of 200 high school students. The questionnaire was developed based on previous studies and was designed to measure the frequency and duration of social media use, as well as academic performance.

The participants were selected using a convenience sampling technique, and the survey questionnaire was distributed in the classroom during regular school hours. The data collected were analyzed using descriptive statistics and correlation analysis.

The findings indicate that the majority of high school students use social media platforms on a daily basis, with Facebook being the most popular platform. The results also show a negative correlation between social media use and academic performance, suggesting that excessive social media use can lead to poor academic performance among high school students.

Discussion:

The results of this study have important implications for educators, parents, and policymakers. The negative correlation between social media use and academic performance suggests that strategies should be put in place to help students balance their social media use and academic responsibilities. For example, educators could incorporate social media into their teaching strategies to engage students and enhance learning. Parents could limit their children’s social media use and encourage them to prioritize their academic responsibilities. Policymakers could develop guidelines and policies to regulate social media use among high school students.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, this study provides evidence of the negative impact of social media on academic performance among high school students. The findings highlight the need for strategies that can help students balance their social media use and academic responsibilities. Further research is needed to explore the specific mechanisms by which social media use affects academic performance and to develop effective strategies for addressing this issue.

Limitations:

One limitation of this study is the use of convenience sampling, which limits the generalizability of the findings to other populations. Future studies should use random sampling techniques to increase the representativeness of the sample. Another limitation is the use of self-reported measures, which may be subject to social desirability bias. Future studies could use objective measures of social media use and academic performance, such as tracking software and school records.

Implications:

The findings of this study have important implications for educators, parents, and policymakers. Educators could incorporate social media into their teaching strategies to engage students and enhance learning. For example, teachers could use social media platforms to share relevant educational resources and facilitate online discussions. Parents could limit their children’s social media use and encourage them to prioritize their academic responsibilities. They could also engage in open communication with their children to understand their social media use and its impact on their academic performance. Policymakers could develop guidelines and policies to regulate social media use among high school students. For example, schools could implement social media policies that restrict access during class time and encourage responsible use.

References:

- Kirschner, P. A., & Karpinski, A. C. (2010). Facebook® and academic performance. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(6), 1237-1245.

- Paul, J. A., Baker, H. M., & Cochran, J. D. (2012). Effect of online social networking on student academic performance. Journal of the Research Center for Educational Technology, 8(1), 1-19.

- Pantic, I. (2014). Online social networking and mental health. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17(10), 652-657.

- Rosen, L. D., Carrier, L. M., & Cheever, N. A. (2013). Facebook and texting made me do it: Media-induced task-switching while studying. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3), 948-958.

Note*: Above mention, Example is just a sample for the students’ guide. Do not directly copy and paste as your College or University assignment. Kindly do some research and Write your own.

Applications of Research Report

Research reports have many applications, including:

- Communicating research findings: The primary application of a research report is to communicate the results of a study to other researchers, stakeholders, or the general public. The report serves as a way to share new knowledge, insights, and discoveries with others in the field.

- Informing policy and practice : Research reports can inform policy and practice by providing evidence-based recommendations for decision-makers. For example, a research report on the effectiveness of a new drug could inform regulatory agencies in their decision-making process.

- Supporting further research: Research reports can provide a foundation for further research in a particular area. Other researchers may use the findings and methodology of a report to develop new research questions or to build on existing research.

- Evaluating programs and interventions : Research reports can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of programs and interventions in achieving their intended outcomes. For example, a research report on a new educational program could provide evidence of its impact on student performance.

- Demonstrating impact : Research reports can be used to demonstrate the impact of research funding or to evaluate the success of research projects. By presenting the findings and outcomes of a study, research reports can show the value of research to funders and stakeholders.

- Enhancing professional development : Research reports can be used to enhance professional development by providing a source of information and learning for researchers and practitioners in a particular field. For example, a research report on a new teaching methodology could provide insights and ideas for educators to incorporate into their own practice.

How to write Research Report

Here are some steps you can follow to write a research report:

- Identify the research question: The first step in writing a research report is to identify your research question. This will help you focus your research and organize your findings.

- Conduct research : Once you have identified your research question, you will need to conduct research to gather relevant data and information. This can involve conducting experiments, reviewing literature, or analyzing data.

- Organize your findings: Once you have gathered all of your data, you will need to organize your findings in a way that is clear and understandable. This can involve creating tables, graphs, or charts to illustrate your results.

- Write the report: Once you have organized your findings, you can begin writing the report. Start with an introduction that provides background information and explains the purpose of your research. Next, provide a detailed description of your research methods and findings. Finally, summarize your results and draw conclusions based on your findings.

- Proofread and edit: After you have written your report, be sure to proofread and edit it carefully. Check for grammar and spelling errors, and make sure that your report is well-organized and easy to read.

- Include a reference list: Be sure to include a list of references that you used in your research. This will give credit to your sources and allow readers to further explore the topic if they choose.

- Format your report: Finally, format your report according to the guidelines provided by your instructor or organization. This may include formatting requirements for headings, margins, fonts, and spacing.

Purpose of Research Report

The purpose of a research report is to communicate the results of a research study to a specific audience, such as peers in the same field, stakeholders, or the general public. The report provides a detailed description of the research methods, findings, and conclusions.

Some common purposes of a research report include:

- Sharing knowledge: A research report allows researchers to share their findings and knowledge with others in their field. This helps to advance the field and improve the understanding of a particular topic.

- Identifying trends: A research report can identify trends and patterns in data, which can help guide future research and inform decision-making.

- Addressing problems: A research report can provide insights into problems or issues and suggest solutions or recommendations for addressing them.

- Evaluating programs or interventions : A research report can evaluate the effectiveness of programs or interventions, which can inform decision-making about whether to continue, modify, or discontinue them.

- Meeting regulatory requirements: In some fields, research reports are required to meet regulatory requirements, such as in the case of drug trials or environmental impact studies.

When to Write Research Report

A research report should be written after completing the research study. This includes collecting data, analyzing the results, and drawing conclusions based on the findings. Once the research is complete, the report should be written in a timely manner while the information is still fresh in the researcher’s mind.

In academic settings, research reports are often required as part of coursework or as part of a thesis or dissertation. In this case, the report should be written according to the guidelines provided by the instructor or institution.

In other settings, such as in industry or government, research reports may be required to inform decision-making or to comply with regulatory requirements. In these cases, the report should be written as soon as possible after the research is completed in order to inform decision-making in a timely manner.

Overall, the timing of when to write a research report depends on the purpose of the research, the expectations of the audience, and any regulatory requirements that need to be met. However, it is important to complete the report in a timely manner while the information is still fresh in the researcher’s mind.

Characteristics of Research Report

There are several characteristics of a research report that distinguish it from other types of writing. These characteristics include:

- Objective: A research report should be written in an objective and unbiased manner. It should present the facts and findings of the research study without any personal opinions or biases.

- Systematic: A research report should be written in a systematic manner. It should follow a clear and logical structure, and the information should be presented in a way that is easy to understand and follow.

- Detailed: A research report should be detailed and comprehensive. It should provide a thorough description of the research methods, results, and conclusions.

- Accurate : A research report should be accurate and based on sound research methods. The findings and conclusions should be supported by data and evidence.

- Organized: A research report should be well-organized. It should include headings and subheadings to help the reader navigate the report and understand the main points.

- Clear and concise: A research report should be written in clear and concise language. The information should be presented in a way that is easy to understand, and unnecessary jargon should be avoided.

- Citations and references: A research report should include citations and references to support the findings and conclusions. This helps to give credit to other researchers and to provide readers with the opportunity to further explore the topic.

Advantages of Research Report

Research reports have several advantages, including:

- Communicating research findings: Research reports allow researchers to communicate their findings to a wider audience, including other researchers, stakeholders, and the general public. This helps to disseminate knowledge and advance the understanding of a particular topic.

- Providing evidence for decision-making : Research reports can provide evidence to inform decision-making, such as in the case of policy-making, program planning, or product development. The findings and conclusions can help guide decisions and improve outcomes.

- Supporting further research: Research reports can provide a foundation for further research on a particular topic. Other researchers can build on the findings and conclusions of the report, which can lead to further discoveries and advancements in the field.

- Demonstrating expertise: Research reports can demonstrate the expertise of the researchers and their ability to conduct rigorous and high-quality research. This can be important for securing funding, promotions, and other professional opportunities.

- Meeting regulatory requirements: In some fields, research reports are required to meet regulatory requirements, such as in the case of drug trials or environmental impact studies. Producing a high-quality research report can help ensure compliance with these requirements.

Limitations of Research Report

Despite their advantages, research reports also have some limitations, including:

- Time-consuming: Conducting research and writing a report can be a time-consuming process, particularly for large-scale studies. This can limit the frequency and speed of producing research reports.

- Expensive: Conducting research and producing a report can be expensive, particularly for studies that require specialized equipment, personnel, or data. This can limit the scope and feasibility of some research studies.

- Limited generalizability: Research studies often focus on a specific population or context, which can limit the generalizability of the findings to other populations or contexts.

- Potential bias : Researchers may have biases or conflicts of interest that can influence the findings and conclusions of the research study. Additionally, participants may also have biases or may not be representative of the larger population, which can limit the validity and reliability of the findings.

- Accessibility: Research reports may be written in technical or academic language, which can limit their accessibility to a wider audience. Additionally, some research may be behind paywalls or require specialized access, which can limit the ability of others to read and use the findings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 11: Presenting Your Research

Writing a Research Report in American Psychological Association (APA) Style

Learning Objectives

- Identify the major sections of an APA-style research report and the basic contents of each section.

- Plan and write an effective APA-style research report.

In this section, we look at how to write an APA-style empirical research report , an article that presents the results of one or more new studies. Recall that the standard sections of an empirical research report provide a kind of outline. Here we consider each of these sections in detail, including what information it contains, how that information is formatted and organized, and tips for writing each section. At the end of this section is a sample APA-style research report that illustrates many of these principles.

Sections of a Research Report

Title page and abstract.

An APA-style research report begins with a title page . The title is centred in the upper half of the page, with each important word capitalized. The title should clearly and concisely (in about 12 words or fewer) communicate the primary variables and research questions. This sometimes requires a main title followed by a subtitle that elaborates on the main title, in which case the main title and subtitle are separated by a colon. Here are some titles from recent issues of professional journals published by the American Psychological Association.

- Sex Differences in Coping Styles and Implications for Depressed Mood

- Effects of Aging and Divided Attention on Memory for Items and Their Contexts

- Computer-Assisted Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Child Anxiety: Results of a Randomized Clinical Trial

- Virtual Driving and Risk Taking: Do Racing Games Increase Risk-Taking Cognitions, Affect, and Behaviour?

Below the title are the authors’ names and, on the next line, their institutional affiliation—the university or other institution where the authors worked when they conducted the research. As we have already seen, the authors are listed in an order that reflects their contribution to the research. When multiple authors have made equal contributions to the research, they often list their names alphabetically or in a randomly determined order.

In some areas of psychology, the titles of many empirical research reports are informal in a way that is perhaps best described as “cute.” They usually take the form of a play on words or a well-known expression that relates to the topic under study. Here are some examples from recent issues of the Journal Psychological Science .

- “Smells Like Clean Spirit: Nonconscious Effects of Scent on Cognition and Behavior”

- “Time Crawls: The Temporal Resolution of Infants’ Visual Attention”

- “Scent of a Woman: Men’s Testosterone Responses to Olfactory Ovulation Cues”

- “Apocalypse Soon?: Dire Messages Reduce Belief in Global Warming by Contradicting Just-World Beliefs”

- “Serial vs. Parallel Processing: Sometimes They Look Like Tweedledum and Tweedledee but They Can (and Should) Be Distinguished”

- “How Do I Love Thee? Let Me Count the Words: The Social Effects of Expressive Writing”

Individual researchers differ quite a bit in their preference for such titles. Some use them regularly, while others never use them. What might be some of the pros and cons of using cute article titles?

For articles that are being submitted for publication, the title page also includes an author note that lists the authors’ full institutional affiliations, any acknowledgments the authors wish to make to agencies that funded the research or to colleagues who commented on it, and contact information for the authors. For student papers that are not being submitted for publication—including theses—author notes are generally not necessary.

The abstract is a summary of the study. It is the second page of the manuscript and is headed with the word Abstract . The first line is not indented. The abstract presents the research question, a summary of the method, the basic results, and the most important conclusions. Because the abstract is usually limited to about 200 words, it can be a challenge to write a good one.

Introduction

The introduction begins on the third page of the manuscript. The heading at the top of this page is the full title of the manuscript, with each important word capitalized as on the title page. The introduction includes three distinct subsections, although these are typically not identified by separate headings. The opening introduces the research question and explains why it is interesting, the literature review discusses relevant previous research, and the closing restates the research question and comments on the method used to answer it.

The Opening

The opening , which is usually a paragraph or two in length, introduces the research question and explains why it is interesting. To capture the reader’s attention, researcher Daryl Bem recommends starting with general observations about the topic under study, expressed in ordinary language (not technical jargon)—observations that are about people and their behaviour (not about researchers or their research; Bem, 2003 [1] ). Concrete examples are often very useful here. According to Bem, this would be a poor way to begin a research report:

Festinger’s theory of cognitive dissonance received a great deal of attention during the latter part of the 20th century (p. 191)

The following would be much better:

The individual who holds two beliefs that are inconsistent with one another may feel uncomfortable. For example, the person who knows that he or she enjoys smoking but believes it to be unhealthy may experience discomfort arising from the inconsistency or disharmony between these two thoughts or cognitions. This feeling of discomfort was called cognitive dissonance by social psychologist Leon Festinger (1957), who suggested that individuals will be motivated to remove this dissonance in whatever way they can (p. 191).

After capturing the reader’s attention, the opening should go on to introduce the research question and explain why it is interesting. Will the answer fill a gap in the literature? Will it provide a test of an important theory? Does it have practical implications? Giving readers a clear sense of what the research is about and why they should care about it will motivate them to continue reading the literature review—and will help them make sense of it.

Breaking the Rules

Researcher Larry Jacoby reported several studies showing that a word that people see or hear repeatedly can seem more familiar even when they do not recall the repetitions—and that this tendency is especially pronounced among older adults. He opened his article with the following humourous anecdote:

A friend whose mother is suffering symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) tells the story of taking her mother to visit a nursing home, preliminary to her mother’s moving there. During an orientation meeting at the nursing home, the rules and regulations were explained, one of which regarded the dining room. The dining room was described as similar to a fine restaurant except that tipping was not required. The absence of tipping was a central theme in the orientation lecture, mentioned frequently to emphasize the quality of care along with the advantages of having paid in advance. At the end of the meeting, the friend’s mother was asked whether she had any questions. She replied that she only had one question: “Should I tip?” (Jacoby, 1999, p. 3)

Although both humour and personal anecdotes are generally discouraged in APA-style writing, this example is a highly effective way to start because it both engages the reader and provides an excellent real-world example of the topic under study.

The Literature Review

Immediately after the opening comes the literature review , which describes relevant previous research on the topic and can be anywhere from several paragraphs to several pages in length. However, the literature review is not simply a list of past studies. Instead, it constitutes a kind of argument for why the research question is worth addressing. By the end of the literature review, readers should be convinced that the research question makes sense and that the present study is a logical next step in the ongoing research process.

Like any effective argument, the literature review must have some kind of structure. For example, it might begin by describing a phenomenon in a general way along with several studies that demonstrate it, then describing two or more competing theories of the phenomenon, and finally presenting a hypothesis to test one or more of the theories. Or it might describe one phenomenon, then describe another phenomenon that seems inconsistent with the first one, then propose a theory that resolves the inconsistency, and finally present a hypothesis to test that theory. In applied research, it might describe a phenomenon or theory, then describe how that phenomenon or theory applies to some important real-world situation, and finally suggest a way to test whether it does, in fact, apply to that situation.

Looking at the literature review in this way emphasizes a few things. First, it is extremely important to start with an outline of the main points that you want to make, organized in the order that you want to make them. The basic structure of your argument, then, should be apparent from the outline itself. Second, it is important to emphasize the structure of your argument in your writing. One way to do this is to begin the literature review by summarizing your argument even before you begin to make it. “In this article, I will describe two apparently contradictory phenomena, present a new theory that has the potential to resolve the apparent contradiction, and finally present a novel hypothesis to test the theory.” Another way is to open each paragraph with a sentence that summarizes the main point of the paragraph and links it to the preceding points. These opening sentences provide the “transitions” that many beginning researchers have difficulty with. Instead of beginning a paragraph by launching into a description of a previous study, such as “Williams (2004) found that…,” it is better to start by indicating something about why you are describing this particular study. Here are some simple examples:

Another example of this phenomenon comes from the work of Williams (2004).

Williams (2004) offers one explanation of this phenomenon.

An alternative perspective has been provided by Williams (2004).

We used a method based on the one used by Williams (2004).

Finally, remember that your goal is to construct an argument for why your research question is interesting and worth addressing—not necessarily why your favourite answer to it is correct. In other words, your literature review must be balanced. If you want to emphasize the generality of a phenomenon, then of course you should discuss various studies that have demonstrated it. However, if there are other studies that have failed to demonstrate it, you should discuss them too. Or if you are proposing a new theory, then of course you should discuss findings that are consistent with that theory. However, if there are other findings that are inconsistent with it, again, you should discuss them too. It is acceptable to argue that the balance of the research supports the existence of a phenomenon or is consistent with a theory (and that is usually the best that researchers in psychology can hope for), but it is not acceptable to ignore contradictory evidence. Besides, a large part of what makes a research question interesting is uncertainty about its answer.

The Closing

The closing of the introduction—typically the final paragraph or two—usually includes two important elements. The first is a clear statement of the main research question or hypothesis. This statement tends to be more formal and precise than in the opening and is often expressed in terms of operational definitions of the key variables. The second is a brief overview of the method and some comment on its appropriateness. Here, for example, is how Darley and Latané (1968) [2] concluded the introduction to their classic article on the bystander effect:

These considerations lead to the hypothesis that the more bystanders to an emergency, the less likely, or the more slowly, any one bystander will intervene to provide aid. To test this proposition it would be necessary to create a situation in which a realistic “emergency” could plausibly occur. Each subject should also be blocked from communicating with others to prevent his getting information about their behaviour during the emergency. Finally, the experimental situation should allow for the assessment of the speed and frequency of the subjects’ reaction to the emergency. The experiment reported below attempted to fulfill these conditions. (p. 378)

Thus the introduction leads smoothly into the next major section of the article—the method section.

The method section is where you describe how you conducted your study. An important principle for writing a method section is that it should be clear and detailed enough that other researchers could replicate the study by following your “recipe.” This means that it must describe all the important elements of the study—basic demographic characteristics of the participants, how they were recruited, whether they were randomly assigned, how the variables were manipulated or measured, how counterbalancing was accomplished, and so on. At the same time, it should avoid irrelevant details such as the fact that the study was conducted in Classroom 37B of the Industrial Technology Building or that the questionnaire was double-sided and completed using pencils.

The method section begins immediately after the introduction ends with the heading “Method” (not “Methods”) centred on the page. Immediately after this is the subheading “Participants,” left justified and in italics. The participants subsection indicates how many participants there were, the number of women and men, some indication of their age, other demographics that may be relevant to the study, and how they were recruited, including any incentives given for participation.

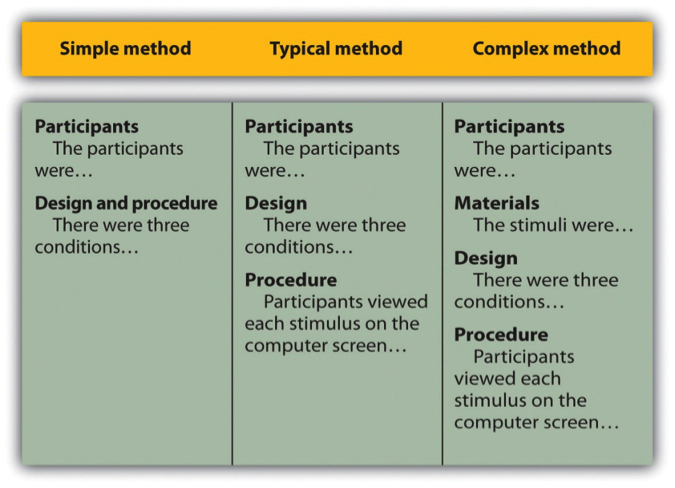

After the participants section, the structure can vary a bit. Figure 11.1 shows three common approaches. In the first, the participants section is followed by a design and procedure subsection, which describes the rest of the method. This works well for methods that are relatively simple and can be described adequately in a few paragraphs. In the second approach, the participants section is followed by separate design and procedure subsections. This works well when both the design and the procedure are relatively complicated and each requires multiple paragraphs.

What is the difference between design and procedure? The design of a study is its overall structure. What were the independent and dependent variables? Was the independent variable manipulated, and if so, was it manipulated between or within subjects? How were the variables operationally defined? The procedure is how the study was carried out. It often works well to describe the procedure in terms of what the participants did rather than what the researchers did. For example, the participants gave their informed consent, read a set of instructions, completed a block of four practice trials, completed a block of 20 test trials, completed two questionnaires, and were debriefed and excused.

In the third basic way to organize a method section, the participants subsection is followed by a materials subsection before the design and procedure subsections. This works well when there are complicated materials to describe. This might mean multiple questionnaires, written vignettes that participants read and respond to, perceptual stimuli, and so on. The heading of this subsection can be modified to reflect its content. Instead of “Materials,” it can be “Questionnaires,” “Stimuli,” and so on.

The results section is where you present the main results of the study, including the results of the statistical analyses. Although it does not include the raw data—individual participants’ responses or scores—researchers should save their raw data and make them available to other researchers who request them. Several journals now encourage the open sharing of raw data online.

Although there are no standard subsections, it is still important for the results section to be logically organized. Typically it begins with certain preliminary issues. One is whether any participants or responses were excluded from the analyses and why. The rationale for excluding data should be described clearly so that other researchers can decide whether it is appropriate. A second preliminary issue is how multiple responses were combined to produce the primary variables in the analyses. For example, if participants rated the attractiveness of 20 stimulus people, you might have to explain that you began by computing the mean attractiveness rating for each participant. Or if they recalled as many items as they could from study list of 20 words, did you count the number correctly recalled, compute the percentage correctly recalled, or perhaps compute the number correct minus the number incorrect? A third preliminary issue is the reliability of the measures. This is where you would present test-retest correlations, Cronbach’s α, or other statistics to show that the measures are consistent across time and across items. A final preliminary issue is whether the manipulation was successful. This is where you would report the results of any manipulation checks.

The results section should then tackle the primary research questions, one at a time. Again, there should be a clear organization. One approach would be to answer the most general questions and then proceed to answer more specific ones. Another would be to answer the main question first and then to answer secondary ones. Regardless, Bem (2003) [3] suggests the following basic structure for discussing each new result:

- Remind the reader of the research question.

- Give the answer to the research question in words.

- Present the relevant statistics.

- Qualify the answer if necessary.

- Summarize the result.

Notice that only Step 3 necessarily involves numbers. The rest of the steps involve presenting the research question and the answer to it in words. In fact, the basic results should be clear even to a reader who skips over the numbers.

The discussion is the last major section of the research report. Discussions usually consist of some combination of the following elements:

- Summary of the research

- Theoretical implications

- Practical implications

- Limitations

- Suggestions for future research

The discussion typically begins with a summary of the study that provides a clear answer to the research question. In a short report with a single study, this might require no more than a sentence. In a longer report with multiple studies, it might require a paragraph or even two. The summary is often followed by a discussion of the theoretical implications of the research. Do the results provide support for any existing theories? If not, how can they be explained? Although you do not have to provide a definitive explanation or detailed theory for your results, you at least need to outline one or more possible explanations. In applied research—and often in basic research—there is also some discussion of the practical implications of the research. How can the results be used, and by whom, to accomplish some real-world goal?

The theoretical and practical implications are often followed by a discussion of the study’s limitations. Perhaps there are problems with its internal or external validity. Perhaps the manipulation was not very effective or the measures not very reliable. Perhaps there is some evidence that participants did not fully understand their task or that they were suspicious of the intent of the researchers. Now is the time to discuss these issues and how they might have affected the results. But do not overdo it. All studies have limitations, and most readers will understand that a different sample or different measures might have produced different results. Unless there is good reason to think they would have, however, there is no reason to mention these routine issues. Instead, pick two or three limitations that seem like they could have influenced the results, explain how they could have influenced the results, and suggest ways to deal with them.

Most discussions end with some suggestions for future research. If the study did not satisfactorily answer the original research question, what will it take to do so? What new research questions has the study raised? This part of the discussion, however, is not just a list of new questions. It is a discussion of two or three of the most important unresolved issues. This means identifying and clarifying each question, suggesting some alternative answers, and even suggesting ways they could be studied.

Finally, some researchers are quite good at ending their articles with a sweeping or thought-provoking conclusion. Darley and Latané (1968) [4] , for example, ended their article on the bystander effect by discussing the idea that whether people help others may depend more on the situation than on their personalities. Their final sentence is, “If people understand the situational forces that can make them hesitate to intervene, they may better overcome them” (p. 383). However, this kind of ending can be difficult to pull off. It can sound overreaching or just banal and end up detracting from the overall impact of the article. It is often better simply to end when you have made your final point (although you should avoid ending on a limitation).

The references section begins on a new page with the heading “References” centred at the top of the page. All references cited in the text are then listed in the format presented earlier. They are listed alphabetically by the last name of the first author. If two sources have the same first author, they are listed alphabetically by the last name of the second author. If all the authors are the same, then they are listed chronologically by the year of publication. Everything in the reference list is double-spaced both within and between references.

Appendices, Tables, and Figures

Appendices, tables, and figures come after the references. An appendix is appropriate for supplemental material that would interrupt the flow of the research report if it were presented within any of the major sections. An appendix could be used to present lists of stimulus words, questionnaire items, detailed descriptions of special equipment or unusual statistical analyses, or references to the studies that are included in a meta-analysis. Each appendix begins on a new page. If there is only one, the heading is “Appendix,” centred at the top of the page. If there is more than one, the headings are “Appendix A,” “Appendix B,” and so on, and they appear in the order they were first mentioned in the text of the report.

After any appendices come tables and then figures. Tables and figures are both used to present results. Figures can also be used to illustrate theories (e.g., in the form of a flowchart), display stimuli, outline procedures, and present many other kinds of information. Each table and figure appears on its own page. Tables are numbered in the order that they are first mentioned in the text (“Table 1,” “Table 2,” and so on). Figures are numbered the same way (“Figure 1,” “Figure 2,” and so on). A brief explanatory title, with the important words capitalized, appears above each table. Each figure is given a brief explanatory caption, where (aside from proper nouns or names) only the first word of each sentence is capitalized. More details on preparing APA-style tables and figures are presented later in the book.

Sample APA-Style Research Report

Figures 11.2, 11.3, 11.4, and 11.5 show some sample pages from an APA-style empirical research report originally written by undergraduate student Tomoe Suyama at California State University, Fresno. The main purpose of these figures is to illustrate the basic organization and formatting of an APA-style empirical research report, although many high-level and low-level style conventions can be seen here too.

Key Takeaways

- An APA-style empirical research report consists of several standard sections. The main ones are the abstract, introduction, method, results, discussion, and references.

- The introduction consists of an opening that presents the research question, a literature review that describes previous research on the topic, and a closing that restates the research question and comments on the method. The literature review constitutes an argument for why the current study is worth doing.

- The method section describes the method in enough detail that another researcher could replicate the study. At a minimum, it consists of a participants subsection and a design and procedure subsection.

- The results section describes the results in an organized fashion. Each primary result is presented in terms of statistical results but also explained in words.

- The discussion typically summarizes the study, discusses theoretical and practical implications and limitations of the study, and offers suggestions for further research.

- Practice: Look through an issue of a general interest professional journal (e.g., Psychological Science ). Read the opening of the first five articles and rate the effectiveness of each one from 1 ( very ineffective ) to 5 ( very effective ). Write a sentence or two explaining each rating.

- Practice: Find a recent article in a professional journal and identify where the opening, literature review, and closing of the introduction begin and end.

- Practice: Find a recent article in a professional journal and highlight in a different colour each of the following elements in the discussion: summary, theoretical implications, practical implications, limitations, and suggestions for future research.

Long Descriptions

Figure 11.1 long description: Table showing three ways of organizing an APA-style method section.

In the simple method, there are two subheadings: “Participants” (which might begin “The participants were…”) and “Design and procedure” (which might begin “There were three conditions…”).

In the typical method, there are three subheadings: “Participants” (“The participants were…”), “Design” (“There were three conditions…”), and “Procedure” (“Participants viewed each stimulus on the computer screen…”).

In the complex method, there are four subheadings: “Participants” (“The participants were…”), “Materials” (“The stimuli were…”), “Design” (“There were three conditions…”), and “Procedure” (“Participants viewed each stimulus on the computer screen…”). [Return to Figure 11.1]

- Bem, D. J. (2003). Writing the empirical journal article. In J. M. Darley, M. P. Zanna, & H. R. Roediger III (Eds.), The compleat academic: A practical guide for the beginning social scientist (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. ↵

- Darley, J. M., & Latané, B. (1968). Bystander intervention in emergencies: Diffusion of responsibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 4 , 377–383. ↵

A type of research article which describes one or more new empirical studies conducted by the authors.

The page at the beginning of an APA-style research report containing the title of the article, the authors’ names, and their institutional affiliation.

A summary of a research study.

The third page of a manuscript containing the research question, the literature review, and comments about how to answer the research question.

An introduction to the research question and explanation for why this question is interesting.

A description of relevant previous research on the topic being discusses and an argument for why the research is worth addressing.

The end of the introduction, where the research question is reiterated and the method is commented upon.

The section of a research report where the method used to conduct the study is described.

The main results of the study, including the results from statistical analyses, are presented in a research article.

Section of a research report that summarizes the study's results and interprets them by referring back to the study's theoretical background.

Part of a research report which contains supplemental material.

Research Methods in Psychology - 2nd Canadian Edition Copyright © 2015 by Paul C. Price, Rajiv Jhangiani, & I-Chant A. Chiang is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Academic Skills

- Reading, writing and referencing

Research reports

This resource will help you identify the common elements and basic format of a research report.

Research reports generally follow a similar structure and have common elements, each with a particular purpose. Learn more about each of these elements below.

Common elements of reports

Your title should be brief, topic-specific, and informative, clearly indicating the purpose and scope of your study. Include key words in your title so that search engines can easily access your work. For example: Measurement of water around Station Pier.

An abstract is a concise summary that helps readers to quickly assess the content and direction of your paper. It should be brief, written in a single paragraph and cover: the scope and purpose of your report; an overview of methodology; a summary of the main findings or results; principal conclusions or significance of the findings; and recommendations made.

The information in the abstract must be presented in the same order as it is in your report. The abstract is usually written last when you have developed your arguments and synthesised the results.

The introduction creates the context for your research. It should provide sufficient background to allow the reader to understand and evaluate your study without needing to refer to previous publications. After reading the introduction your reader should understand exactly what your research is about, what you plan to do, why you are undertaking this research and which methods you have used. Introductions generally include:

- The rationale for the present study. Why are you interested in this topic? Why is this topic worth investigating?

- Key terms and definitions.

- An outline of the research questions and hypotheses; the assumptions or propositions that your research will test.

Not all research reports have a separate literature review section. In shorter research reports, the review is usually part of the Introduction.

A literature review is a critical survey of recent relevant research in a particular field. The review should be a selection of carefully organised, focused and relevant literature that develops a narrative ‘story’ about your topic. Your review should answer key questions about the literature:

- What is the current state of knowledge on the topic?

- What differences in approaches / methodologies are there?

- Where are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

- What further research is needed? The review may identify a gap in the literature which provides a rationale for your study and supports your research questions and methodology.

The review is not just a summary of all you have read. Rather, it must develop an argument or a point of view that supports your chosen methodology and research questions.

The purpose of this section is to detail how you conducted your research so that others can understand and replicate your approach.

You need to briefly describe the subjects (if appropriate), any equipment or materials used and the approach taken. If the research method or method of data analysis is commonly used within your field of study, then simply reference the procedure. If, however, your methods are new or controversial then you need to describe them in more detail and provide a rationale for your approach. The methodology is written in the past tense and should be as concise as possible.

This section is a concise, factual summary of your findings, listed under headings appropriate to your research questions. It’s common to use tables and graphics. Raw data or details about the method of statistical analysis used should be included in the Appendices.

Present your results in a consistent manner. For example, if you present the first group of results as percentages, it will be confusing for the reader and difficult to make comparisons of data if later results are presented as fractions or as decimal values.

In general, you won’t discuss your results here. Any analysis of your results usually occurs in the Discussion section.

Notes on visual data representation:

- Graphs and tables may be used to reveal trends in your data, but they must be explained and referred to in adjacent accompanying text.

- Figures and tables do not simply repeat information given in the text: they summarise, amplify or complement it.

- Graphs are always referred to as ‘Figures’, and both axes must be clearly labelled.

- Tables must be numbered, and they must be able to stand-alone or make sense without your reader needing to read all of the accompanying text.

The Discussion responds to the hypothesis or research question. This section is where you interpret your results, account for your findings and explain their significance within the context of other research. Consider the adequacy of your sampling techniques, the scope and long-term implications of your study, any problems with data collection or analysis and any assumptions on which your study was based. This is also the place to discuss any disappointing results and address limitations.

Checklist for the discussion

- To what extent was each hypothesis supported?

- To what extent are your findings validated or supported by other research?

- Were there unexpected variables that affected your results?

- On reflection, was your research method appropriate?

- Can you account for any differences between your results and other studies?

Conclusions in research reports are generally fairly short and should follow on naturally from points raised in the Discussion. In this section you should discuss the significance of your findings. To what extent and in what ways are your findings useful or conclusive? Is further research required? If so, based on your research experience, what suggestions could you make about improvements to the scope or methodology of future studies?

Also, consider the practical implications of your results and any recommendations you could make. For example, if your research is on reading strategies in the primary school classroom, what are the implications of your results for the classroom teacher? What recommendations could you make for teachers?

A Reference List contains all the resources you have cited in your work, while a Bibliography is a wider list containing all the resources you have consulted (but not necessarily cited) in the preparation of your work. It is important to check which of these is required, and the preferred format, style of references and presentation requirements of your own department.

Appendices (singular ‘Appendix’) provide supporting material to your project. Examples of such materials include:

- Relevant letters to participants and organisations (e.g. regarding the ethics or conduct of the project).

- Background reports.

- Detailed calculations.

Different types of data are presented in separate appendices. Each appendix must be titled, labelled with a number or letter, and referred to in the body of the report.

Appendices are placed at the end of a report, and the contents are generally not included in the word count.

Fi nal ti p

While there are many common elements to research reports, it’s always best to double check the exact requirements for your task. You may find that you don’t need some sections, can combine others or have specific requirements about referencing, formatting or word limits.

Looking for one-on-one advice?

Get tailored advice from an Academic Skills Adviser by booking an Individual appointment, or get quick feedback from one of our Academic Writing Mentors via email through our Writing advice service.

Go to Student appointments

Jerz's Literacy Weblog (est. 1999)

Short research papers: how to write academic essays.

Jerz > Writing > Academic > Research Papers [ Title | Thesis | Blueprint | Quoting | Citing | MLA Format ]

This document focuses on the kind of short, narrowly-focused research papers that might be the final project in a freshman writing class or 200-level literature survey course.

In high school, you probably wrote a lot of personal essays (where your goal was to demonstrate you were engaged) and a lot of info-dump paragraphs (where your goal was to demonstrate you could remember and organize information your teacher told you to learn).

How is a college research essay different from the writing you did in high school?

This short video covers the same topic in a different way; I think the video and handout work together fairly well.

The assignment description your professor has already given you is your best source for understanding your specific writing task, but in general, a college research paper asks you to use evidence to defend some non-obvious, nuanced point about a complex topic.

Some professors may simply want you to explain a situation or describe a process; however, a more challenging task asks you to take a stand, demonstrating you can use credible sources to defend your original ideas.

- Choose a Narrow Topic

- Use Sources Appropriately

Avoid Distractions

Outside the classroom, if I want to “research” which phone I should buy, I would start with Google.

I would watch some YouTube unboxing videos, and I might ask my friends on social media. I’d assume somebody already has written about or knows about the latest phones, and the goal of my “research” is to find what the people I trust think is the correct answer.

An entomologist might do “research” by going into the forest, and catching and observing hundreds or thousands of butterflies. If she had begun and ended her research by Googling for “butterflies of Pennsylvania” she would never have seen, with her own eyes, that unusual specimen that leads her to conclude she has discovered a new species.

Her goal as a field researcher is not to find the “correct answer” that someone else has already published. Instead, her goal is to add something new to the store of human knowledge — something that hasn’t been written down yet.

As an undergraduate with a few short months or weeks to write a research paper, you won’t be expected to discover a new species of butterfly, or convince everyone on the planet to accept what 99.9% of scientists say about vaccines or climate change, or to adopt your personal views on abortion, vaping, or tattoos.

But your professor will probably want you to read essays published by credentialed experts who are presenting their results to other experts, often in excruciating detail that most of us non-experts will probably find boring.

Your instructor probably won’t give the results of a random Google search the same weight as peer-reviewed scholarly articles from academic journals. (See “ Academic Journals: What Are They? “)

The best databases are not free, but your student ID will get you access to your school’s collection of databases, so you should never have to pay to access any source. (Your friendly school librarian will help you find out exactly how to access the databases at your school.)

1. Plan to Revise

Even a very short paper is the result of a process.

- You start with one idea, you test it, and you hit on something better.

- You might end up somewhere unexpected. If so, that’s good — it means you learned something.

- If you’re only just starting your paper, and it’s due tomorrow, you have already robbed yourself of your most valuable resource — time.

Showcase your best insights at the beginning of your paper (rather than saving them for the end).

You won’t know what your best ideas are until you’ve written a full draft. Part of revision involves identifying strong ideas and making them more prominent, identifying filler and other weak material, and pruning it away to leave more room to develop your best ideas.

- It’s normal, in a your very first “discovery draft,” to hit on a really good idea about two-thirds of the way through your paper.

- But a polished academic paper is not a mystery novel. (A busy reader will not have the patience to hunt for clues.)

- A thesis statement that includes a clear reasoning blueprint (see “ Blueprinting: Planning Your Essay “) will help your reader identify and follow your ideas.

Before you submit your draft, make sure the title, the introduction, and the conclusion match . (I am amazed at how many students overlook this simple step.)

2. Choose a Narrow Topic

A short undergraduate research paper is not the proper occasion for you to tackle huge issues, such as, “Was Hamlet Shakespeare’s Best Tragedy?” or “Women’s Struggle for Equality” or “How to Eliminate Racism.” You won’t be graded down simply because you don’t have all the answers right away. The trick is to zoom in on one tiny little part of the argument .

Short Research Paper: Sample Topics

How would you improve each of these paper topics? (My responses are at the bottom of the page.)

- Environmentalism in America

- Immigration Trends in Wisconsin’s Chippewa Valley

- Drinking and Driving

- Local TV News

- 10 Ways that Advertisers Lie to the Public

- Athletes on College Campuses

3. Use Sources Appropriately

Unless you were asked to write an opinion paper or a reflection statement, your professor probably expects you to draw a topic from the assigned readings (if any).

- Some students frequently get this backwards — they write the paper first, then “look for quotes” from sources that agree with the opinions they’ve already committed to. (That’s not really doing research to learn anything new — that’s just looking for confirmation of what you already believe.)

- Start with the readings, but don’t pad your paper with summary .

- Many students try doing most of their research using Google. Depending on your topic, the Internet may simply not have good sources available.

- Go ahead and surf as you try to narrow your topic, but remember: you still need to cite whatever you find. (See: “ Researching Academic Papers .”)

When learning about the place of women in Victorian society, Sally is shocked to discover women couldn’t vote or own property. She begins her paper by listing these and other restrictions, and adds personal commentary such as:

Women can be just as strong and capable as men are. Why do men think they have the right to make all the laws and keep all the money, when women stay in the kitchen? People should be judged by what they contribute to society, not by the kind of chromosomes they carry.

After reaching the required number of pages, she tacks on a conclusion about how women are still fighting for their rights today, and submits her paper.

- during the Victorian period, female authors were being published and read like never before

- the public praised Queen Victoria (a woman!) for making England a world empire

- some women actually fought against the new feminists because they distrusted their motives

- many wealthy women in England were downright nasty to their poorer sisters, especially the Irish.

- Sally’s paper focused mainly on her general impression that sexism is unfair (something that she already believed before she started taking the course), but Sally has not engaged with the controversies or surprising details (such as, for instance, the fact that for the first time male writers were writing with female readers in mind; or that upperclass women contributed to the degradation of lower-class women).

On the advice of her professor, Sally revises her paper as follows:

Sally’s focused revision (right) makes specific reference to a particular source , and uses a quote to introduce a point. Sally still injects her own opinion, but she is offering specific comments on complex issues, not bumper-sticker slogans and sweeping generalizations, such as those given on the left.

Documenting Evidence

Back up your claims by quoting reputable sources . If you write”Recent research shows that…” or “Many scholars believe that…”, you are making a claim. You will have to back it up with authoritative evidence. This means that the body of your paper must include references to the specific page numbers where you got your outside information. (If your document is an online source that does not provide page numbers, ask your instructor what you should do. There might be a section title or paragraph number that you could cite, or you might print out the article and count the pages in your printout.)

Avoid using words like “always” or “never,” since all it takes is a single example to the contrary to disprove your claim. Likewise, be careful with words of causation and proof. For example, consider the claim that television causes violence in kids. The evidence might be that kids who commit crimes typically watch more television than kids who don’t. But… maybe the reason kids watch more television is that they’ve dropped out of school, and are unsupervised at home. An unsupervised kid might watch more television, and also commit more crimes — but that doesn’t mean that the television is the cause of those crimes.

You don’t need to cite common facts or observations, such as “a circle has 360 degrees” or “8-tracks and vinyl records are out of date,” but you would need to cite claims such as “circles have religious and philosophical significance in many cultures” or “the sales of 8-track tapes never approached those of vinyl records.”

Don’t waste words referring directly to “quotes” and “sources.”

If you use words like “in the book My Big Boring Academic Study , by Professor H. Pompous Windbag III, it says” or “the following quote by a government study shows that…” you are wasting words that would be better spent developing your ideas.

In the book Gramophone, Film, Typewriter , by Fredrich A. Kittler, it talks about writing and gender, and says on page 186, “an omnipresent metaphor equated women with the white sheet of nature or virginity onto which a very male stylus could inscribe the glory of its authorship.” As you can see from this quote, all this would change when women started working as professional typists.

The “it talks about” and “As you can see from this quote” are weak attempts to engage with the ideas presented by Kittler. “In the book… it talks” is wordy and nonsensical (books don’t talk).