Home — Essay Samples — Nursing & Health — Covid 19 — My Experience during the COVID-19 Pandemic

My Experience During The Covid-19 Pandemic

- Categories: Covid 19

About this sample

Words: 440 |

Published: Jan 30, 2024

Words: 440 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Table of contents

Introduction, physical impact, mental and emotional impact, social impact.

- World Health Organization. (2021). Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/

- American Psychiatric Association. (2020). Mental health and COVID-19. https://www.psychiatry.org/news-room/apa-blogs/apa-blog/2020/03/mental-health-and-covid-19

- The New York Times. (2020). Coping with Coronavirus Anxiety. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/11/well/family/coronavirus-anxiety-mental-health.html

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof Ernest (PhD)

Verified writer

- Expert in: Nursing & Health

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 1104 words

6 pages / 2925 words

1 pages / 603 words

1 pages / 670 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Covid 19

COVID-19, caused by the novel coronavirus, has had a profound impact on the global education system. The pandemic has forced educational institutions to rapidly adapt to unprecedented challenges while also presenting new [...]

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the indispensable role of accurate information and scientific advancements in managing public health crises. In a time marked by uncertainty and fear, access to reliable data and ongoing [...]

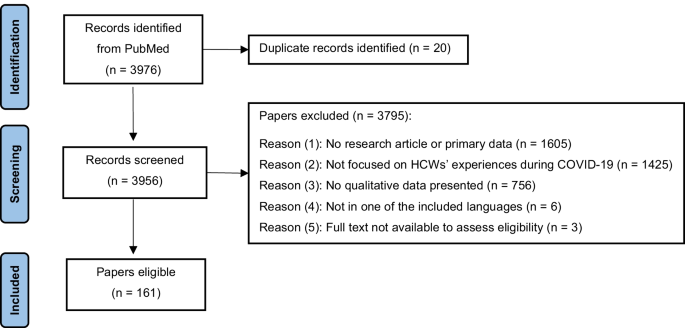

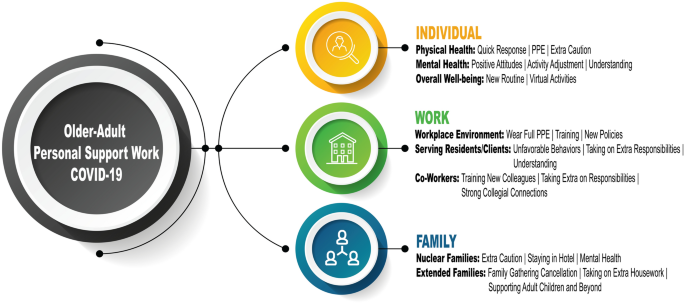

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought unprecedented challenges to healthcare workers worldwide. This qualitative essay employs a research approach to gain insights into the perceptions and experiences of healthcare workers on the [...]

The United Kingdom has long been a popular destination for tourists from around the world, known for its rich history, diverse culture, and stunning landscapes. However, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 had a [...]

As a Computer Science student who never took Pre-Calculus and Basic Calculus in Senior High School, I never realized that there will be a relevance of Calculus in everyday life for a student. Before the beginning of it uses, [...]

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought about unprecedented challenges and shifts in various aspects of our lives, including the realm of selfless service. In this essay, we explore how the pandemic has impacted selfless service, [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Personal Experience With the COVID-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected many areas of individuals’ daily living. The vulnerability to any epidemic depends on a person’s social and economic status. Some people with underlying medical conditions have succumbed to the disease, while others with stronger immunity have survived (Cohut para.6). Governments have restricted movements and introduced stern measures against violating such health precautions as physical distancing and wearing masks. The COVID-19 pandemic has forced people to adopt various responses to its effects, such as homeschooling, working from home, and ordering foods and other commodities from online stores.

I have restricted my movements and opted to order foodstuffs and other essential goods online with doorstep delivery services. I like adventure, and before the pandemic, I would go to parks and other recreational centers to have fun. But this time, I am mostly confined to my room studying, doing school assignments, or reading storybooks, when I do not have an in-person session at college. I have also had to use social media more than before to connect with my family and friends. I miss participating in outdoor activities and meeting with my friends. However, it is worth it because the virus is deadly, and I have had to adapt to this new normal in my life.

With the pandemic requiring stern measures and precautions due to its transmission mode, the federal government has done well in handling the matter. One of the positives is that it has sent financial and material aid to individual state and local governments to help people cope up with the economic challenges the pandemic has posed (Solomon para. 8). Another plus for the federal government is funding the COVID-19 testing, contact tracing, and distributing the vaccine. Lastly, the government has extended unemployment benefits as a rescue plan to help households with an income of less than $150,000 (Solomon para. 9). Therefore, the federal government is trying its best to handle this pandemic.

The New Jersey government has done all it can to handle this pandemic well, but there are still some areas of improvement. As of March 7, 2021, New Jersey was having the highest number of deaths related to COVID-19, but Governor Phil Murphy’s initial handling of the pandemic attracted praises from many quarters (Stanmyre para. 10). In his early days in office, Gov. Murphy portrayed a sense of competency and calm, but it seems other states adopted much of his policies better than he did, explaining the reduction in the approval ratings. In November 2020, Governor Murphy signed an Executive Order cushioning and protecting workers from contracting COVID-19 at the workplace (Stanmyre para. 12). Therefore, although there are mixed feelings, the NJ government is handling this pandemic well.

Some states have reopened immediately after the vaccination, but this poses a massive risk of spreading the virus. Soon, citizens will begin to neglect the laid down health protocols, which would increase the possibility of the increase of the COVID-19 cases. There is a need for health departments to ensure that the health precautions are followed and campaign on the need to adhere to the guidelines. Some individuals are protesting their states’ economy to be reopened, but that is a rash, ill-informed decision. The threat of the pandemic is still high, and it is not the right time to demand the reopening of the economy yet.

In conclusion, the pandemic has affected individuals, businesses, and governments in many ways. Due to how the virus spreads, physical distancing has become a new normal, with people forced to homeschool or work from home to prevent themselves from contracting the disease. The federal government has done its best to cushion its people from the pandemic’s economic effects through various financial rescue schemes and plans. New Jersey’s government has also done well, although its cases continue to soar as it is the leading state in COVID-19 prevalence. Some states have reopened, while in others, people continue to demand their state governments to open the economy, which would be a risky move.

Works Cited

Cohut, Maria. “COVID-19 at the 1-year Mark: How the Pandemic Has Affected the World.” Medical and Health Information . Web.

Solomon, Rachel. “What is the Federal Government Doing to Help People Impacted by Coronavirus?” Cancer Support Community . Web.

Stanmyre, Matthew. “N.J.’s Pandemic Response Started Strong. Why Has So Much Gone Wrong Since?” 2021. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, February 26). Personal Experience With the COVID-19 Pandemic. https://ivypanda.com/essays/personal-experience-with-the-covid-19-pandemic/

"Personal Experience With the COVID-19 Pandemic." IvyPanda , 26 Feb. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/personal-experience-with-the-covid-19-pandemic/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'Personal Experience With the COVID-19 Pandemic'. 26 February.

IvyPanda . 2024. "Personal Experience With the COVID-19 Pandemic." February 26, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/personal-experience-with-the-covid-19-pandemic/.

1. IvyPanda . "Personal Experience With the COVID-19 Pandemic." February 26, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/personal-experience-with-the-covid-19-pandemic/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Personal Experience With the COVID-19 Pandemic." February 26, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/personal-experience-with-the-covid-19-pandemic/.

- American Great Depression and New Deal Reforms

- Art Gallery with Ko-Kutani

- Why Howard Stern is an Effective Communicator

- The 4th and 14th Amendments of the US: Cupp v. Murphy

- Social Distancing During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Pros and Cons

- Climate Change: Nicholas Stern and Ross Garnaut Views

- Good Leadership by Cub Master Mike Murphy in the Cub Scout Pack 81 Organization

- The Character of Elizabeth Gilbert in "Eat Pray Love" by Ryan Murphy

- "The Week the World Stood Still" by Sheldon Stern

- “Performance Evaluation Will Not Die, but It Should” by Kevin R. Murphy

- Living as an Arab Girl in the United States

- The Myers-Briggs Test: Personal Leadership

- Making Career Choices: Refinery

- Assessing the Personal Stress Levels

- Death, Dying, and Bereavement: Reflection

- Newsletters

Site search

- Israel-Hamas war

- 2024 election

- Solar eclipse

- Supreme Court

- All explainers

- Future Perfect

Filed under:

Read these 12 moving essays about life during coronavirus

Artists, novelists, critics, and essayists are writing the first draft of history.

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: Read these 12 moving essays about life during coronavirus

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/66606035/1207638131.jpg.0.jpg)

The world is grappling with an invisible, deadly enemy, trying to understand how to live with the threat posed by a virus . For some writers, the only way forward is to put pen to paper, trying to conceptualize and document what it feels like to continue living as countries are under lockdown and regular life seems to have ground to a halt.

So as the coronavirus pandemic has stretched around the world, it’s sparked a crop of diary entries and essays that describe how life has changed. Novelists, critics, artists, and journalists have put words to the feelings many are experiencing. The result is a first draft of how we’ll someday remember this time, filled with uncertainty and pain and fear as well as small moments of hope and humanity.

At the New York Review of Books, Ali Bhutto writes that in Karachi, Pakistan, the government-imposed curfew due to the virus is “eerily reminiscent of past military clampdowns”:

Beneath the quiet calm lies a sense that society has been unhinged and that the usual rules no longer apply. Small groups of pedestrians look on from the shadows, like an audience watching a spectacle slowly unfolding. People pause on street corners and in the shade of trees, under the watchful gaze of the paramilitary forces and the police.

His essay concludes with the sobering note that “in the minds of many, Covid-19 is just another life-threatening hazard in a city that stumbles from one crisis to another.”

Writing from Chattanooga, novelist Jamie Quatro documents the mixed ways her neighbors have been responding to the threat, and the frustration of conflicting direction, or no direction at all, from local, state, and federal leaders:

Whiplash, trying to keep up with who’s ordering what. We’re already experiencing enough chaos without this back-and-forth. Why didn’t the federal government issue a nationwide shelter-in-place at the get-go, the way other countries did? What happens when one state’s shelter-in-place ends, while others continue? Do states still under quarantine close their borders? We are still one nation, not fifty individual countries. Right?

Award-winning photojournalist Alessio Mamo, quarantined with his partner Marta in Sicily after she tested positive for the virus, accompanies his photographs in the Guardian of their confinement with a reflection on being confined :

The doctors asked me to take a second test, but again I tested negative. Perhaps I’m immune? The days dragged on in my apartment, in black and white, like my photos. Sometimes we tried to smile, imagining that I was asymptomatic, because I was the virus. Our smiles seemed to bring good news. My mother left hospital, but I won’t be able to see her for weeks. Marta started breathing well again, and so did I. I would have liked to photograph my country in the midst of this emergency, the battles that the doctors wage on the frontline, the hospitals pushed to their limits, Italy on its knees fighting an invisible enemy. That enemy, a day in March, knocked on my door instead.

In the New York Times Magazine, deputy editor Jessica Lustig writes with devastating clarity about her family’s life in Brooklyn while her husband battled the virus, weeks before most people began taking the threat seriously:

At the door of the clinic, we stand looking out at two older women chatting outside the doorway, oblivious. Do I wave them away? Call out that they should get far away, go home, wash their hands, stay inside? Instead we just stand there, awkwardly, until they move on. Only then do we step outside to begin the long three-block walk home. I point out the early magnolia, the forsythia. T says he is cold. The untrimmed hairs on his neck, under his beard, are white. The few people walking past us on the sidewalk don’t know that we are visitors from the future. A vision, a premonition, a walking visitation. This will be them: Either T, in the mask, or — if they’re lucky — me, tending to him.

Essayist Leslie Jamison writes in the New York Review of Books about being shut away alone in her New York City apartment with her 2-year-old daughter since she became sick:

The virus. Its sinewy, intimate name. What does it feel like in my body today? Shivering under blankets. A hot itch behind the eyes. Three sweatshirts in the middle of the day. My daughter trying to pull another blanket over my body with her tiny arms. An ache in the muscles that somehow makes it hard to lie still. This loss of taste has become a kind of sensory quarantine. It’s as if the quarantine keeps inching closer and closer to my insides. First I lost the touch of other bodies; then I lost the air; now I’ve lost the taste of bananas. Nothing about any of these losses is particularly unique. I’ve made a schedule so I won’t go insane with the toddler. Five days ago, I wrote Walk/Adventure! on it, next to a cut-out illustration of a tiger—as if we’d see tigers on our walks. It was good to keep possibility alive.

At Literary Hub, novelist Heidi Pitlor writes about the elastic nature of time during her family’s quarantine in Massachusetts:

During a shutdown, the things that mark our days—commuting to work, sending our kids to school, having a drink with friends—vanish and time takes on a flat, seamless quality. Without some self-imposed structure, it’s easy to feel a little untethered. A friend recently posted on Facebook: “For those who have lost track, today is Blursday the fortyteenth of Maprilay.” ... Giving shape to time is especially important now, when the future is so shapeless. We do not know whether the virus will continue to rage for weeks or months or, lord help us, on and off for years. We do not know when we will feel safe again. And so many of us, minus those who are gifted at compartmentalization or denial, remain largely captive to fear. We may stay this way if we do not create at least the illusion of movement in our lives, our long days spent with ourselves or partners or families.

Novelist Lauren Groff writes at the New York Review of Books about trying to escape the prison of her fears while sequestered at home in Gainesville, Florida:

Some people have imaginations sparked only by what they can see; I blame this blinkered empiricism for the parks overwhelmed with people, the bars, until a few nights ago, thickly thronged. My imagination is the opposite. I fear everything invisible to me. From the enclosure of my house, I am afraid of the suffering that isn’t present before me, the people running out of money and food or drowning in the fluid in their lungs, the deaths of health-care workers now growing ill while performing their duties. I fear the federal government, which the right wing has so—intentionally—weakened that not only is it insufficient to help its people, it is actively standing in help’s way. I fear we won’t sufficiently punish the right. I fear leaving the house and spreading the disease. I fear what this time of fear is doing to my children, their imaginations, and their souls.

At ArtForum , Berlin-based critic and writer Kristian Vistrup Madsen reflects on martinis, melancholia, and Finnish artist Jaakko Pallasvuo’s 2018 graphic novel Retreat , in which three young people exile themselves in the woods:

In melancholia, the shape of what is ending, and its temporality, is sprawling and incomprehensible. The ambivalence makes it hard to bear. The world of Retreat is rendered in lush pink and purple watercolors, which dissolve into wild and messy abstractions. In apocalypse, the divisions established in genesis bleed back out. My own Corona-retreat is similarly soft, color-field like, each day a blurred succession of quarantinis, YouTube–yoga, and televized press conferences. As restrictions mount, so does abstraction. For now, I’m still rooting for love to save the world.

At the Paris Review , Matt Levin writes about reading Virginia Woolf’s novel The Waves during quarantine:

A retreat, a quarantine, a sickness—they simultaneously distort and clarify, curtail and expand. It is an ideal state in which to read literature with a reputation for difficulty and inaccessibility, those hermetic books shorn of the handholds of conventional plot or characterization or description. A novel like Virginia Woolf’s The Waves is perfect for the state of interiority induced by quarantine—a story of three men and three women, meeting after the death of a mutual friend, told entirely in the overlapping internal monologues of the six, interspersed only with sections of pure, achingly beautiful descriptions of the natural world, a day’s procession and recession of light and waves. The novel is, in my mind’s eye, a perfectly spherical object. It is translucent and shimmering and infinitely fragile, prone to shatter at the slightest disturbance. It is not a book that can be read in snatches on the subway—it demands total absorption. Though it revels in a stark emotional nakedness, the book remains aloof, remote in its own deep self-absorption.

In an essay for the Financial Times, novelist Arundhati Roy writes with anger about Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s anemic response to the threat, but also offers a glimmer of hope for the future:

Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.

From Boston, Nora Caplan-Bricker writes in The Point about the strange contraction of space under quarantine, in which a friend in Beirut is as close as the one around the corner in the same city:

It’s a nice illusion—nice to feel like we’re in it together, even if my real world has shrunk to one person, my husband, who sits with his laptop in the other room. It’s nice in the same way as reading those essays that reframe social distancing as solidarity. “We must begin to see the negative space as clearly as the positive, to know what we don’t do is also brilliant and full of love,” the poet Anne Boyer wrote on March 10th, the day that Massachusetts declared a state of emergency. If you squint, you could almost make sense of this quarantine as an effort to flatten, along with the curve, the distinctions we make between our bonds with others. Right now, I care for my neighbor in the same way I demonstrate love for my mother: in all instances, I stay away. And in moments this month, I have loved strangers with an intensity that is new to me. On March 14th, the Saturday night after the end of life as we knew it, I went out with my dog and found the street silent: no lines for restaurants, no children on bicycles, no couples strolling with little cups of ice cream. It had taken the combined will of thousands of people to deliver such a sudden and complete emptiness. I felt so grateful, and so bereft.

And on his own website, musician and artist David Byrne writes about rediscovering the value of working for collective good , saying that “what is happening now is an opportunity to learn how to change our behavior”:

In emergencies, citizens can suddenly cooperate and collaborate. Change can happen. We’re going to need to work together as the effects of climate change ramp up. In order for capitalism to survive in any form, we will have to be a little more socialist. Here is an opportunity for us to see things differently — to see that we really are all connected — and adjust our behavior accordingly. Are we willing to do this? Is this moment an opportunity to see how truly interdependent we all are? To live in a world that is different and better than the one we live in now? We might be too far down the road to test every asymptomatic person, but a change in our mindsets, in how we view our neighbors, could lay the groundwork for the collective action we’ll need to deal with other global crises. The time to see how connected we all are is now.

The portrait these writers paint of a world under quarantine is multifaceted. Our worlds have contracted to the confines of our homes, and yet in some ways we’re more connected than ever to one another. We feel fear and boredom, anger and gratitude, frustration and strange peace. Uncertainty drives us to find metaphors and images that will let us wrap our minds around what is happening.

Yet there’s no single “what” that is happening. Everyone is contending with the pandemic and its effects from different places and in different ways. Reading others’ experiences — even the most frightening ones — can help alleviate the loneliness and dread, a little, and remind us that what we’re going through is both unique and shared by all.

Will you support Vox today?

We believe that everyone deserves to understand the world that they live in. That kind of knowledge helps create better citizens, neighbors, friends, parents, and stewards of this planet. Producing deeply researched, explanatory journalism takes resources. You can support this mission by making a financial gift to Vox today. Will you join us?

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

Next Up In Culture

Sign up for the newsletter today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

Thanks for signing up!

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

Tucker Carlson went after Israel — and his fellow conservatives are furious

The dairy industry really, really doesn’t want you to say “bird flu in cows”

Why the case at the center of Netflix’s What Jennifer Did isn’t over yet

The Supreme Court’s confusing new anti-trans decision, explained

Vox podcasts tackle the Israel-Hamas war

Alec Baldwin’s Rust, the on-set shooting, and the ongoing legal cases, explained

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Tell us about your experiences during the Covid pandemic

Whether you’ve suffered in the past year or been lucky enough to escape the worst of it, we would like to hear your stories about the pandemic

The pandemic has been a difficult, dramatic time for so many of us, for so many different reasons. We have lost loved ones, had our families torn apart, struggled financially and emotionally. Some of us have been stressed by overwork; others by sudden unemployment. We have had to shield from the outside world – or been reluctantly obliged to mix with it.

If you have a story to share we would love to hear from you. You might be a doctor working flat out in A&E, a student who was locked down at university, a key worker forced to serve the public with inadequate PPE, a single mother who had to go months without childcare, a son who couldn’t visit his dying father in the care home … or even one of the lucky ones who has come out of the past year feeling stronger and more optimistic about life.

For a special feature, we’re aiming to put readers in touch with each other, to talk about their experiences and insights.

Share your experiences

You can get in touch by filling in the form below. Your responses are secure as the form is encrypted and only the Guardian has access to your contributions. One of our journalists will be in contact before we publish, so please do leave contact details.

If you’re having trouble using the form, click here . Read terms of service here .

- Coronavirus

Most viewed

Resources for

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Admin Resources

Search form

Essays reveal experiences during pandemic, unrest.

Field study students share their thoughts

Members of Advanced Field Study, a select group of Social Ecology students who are chosen from a pool of applicants to participate in a year-long field study experience and course, had their internships and traditional college experience cut short this year. During our final quarter of the year together, during which we met weekly for two hours via Zoom, we discussed their reactions as the world fell apart around them. First came the pandemic and social distancing, then came the death of George Floyd and the response of the Black Lives Matter movement, both of which were imprinted on the lives of these students. This year was anything but dull, instead full of raw emotion and painful realizations of the fragility of the human condition and the extent to which we need one another. This seemed like the perfect opportunity for our students to chronicle their experiences — the good and the bad, the lessons learned, and ways in which they were forever changed by the events of the past four months. I invited all of my students to write an essay describing the ways in which these times had impacted their learning and their lives during or after their time at UCI. These are their voices. — Jessica Borelli , associate professor of psychological science

Becoming Socially Distant Through Technology: The Tech Contagion

The current state of affairs put the world on pause, but this pause gave me time to reflect on troubling matters. Time that so many others like me probably also desperately needed to heal without even knowing it. Sometimes it takes one’s world falling apart for the most beautiful mosaic to be built up from the broken pieces of wreckage.

As the school year was coming to a close and summer was edging around the corner, I began reflecting on how people will spend their summer breaks if the country remains in its current state throughout the sunny season. Aside from living in the sunny beach state of California where people love their vitamin D and social festivities, I think some of the most damaging effects Covid-19 will have on us all has more to do with social distancing policies than with any inconveniences we now face due to the added precautions, despite how devastating it may feel that Disneyland is closed to all the local annual passholders or that the beaches may not be filled with sun-kissed California girls this summer. During this unprecedented time, I don’t think we should allow the rare opportunity we now have to be able to watch in real time how the effects of social distancing can impact our mental health. Before the pandemic, many of us were already engaging in a form of social distancing. Perhaps not the exact same way we are now practicing, but the technology that we have developed over recent years has led to a dramatic decline in our social contact and skills in general.

The debate over whether we should remain quarantined during this time is not an argument I am trying to pursue. Instead, I am trying to encourage us to view this event as a unique time to study how social distancing can affect people’s mental health over a long period of time and with dramatic results due to the magnitude of the current issue. Although Covid-19 is new and unfamiliar to everyone, the isolation and separation we now face is not. For many, this type of behavior has already been a lifestyle choice for a long time. However, the current situation we all now face has allowed us to gain a more personal insight on how that experience feels due to the current circumstances. Mental illness continues to remain a prevalent problem throughout the world and for that reason could be considered a pandemic of a sort in and of itself long before the Covid-19 outbreak.

One parallel that can be made between our current restrictions and mental illness reminds me in particular of hikikomori culture. Hikikomori is a phenomenon that originated in Japan but that has since spread internationally, now prevalent in many parts of the world, including the United States. Hikikomori is not a mental disorder but rather can appear as a symptom of a disorder. People engaging in hikikomori remain confined in their houses and often their rooms for an extended period of time, often over the course of many years. This action of voluntary confinement is an extreme form of withdrawal from society and self-isolation. Hikikomori affects a large percent of people in Japan yearly and the problem continues to become more widespread with increasing occurrences being reported around the world each year. While we know this problem has continued to increase, the exact number of people practicing hikikomori is unknown because there is a large amount of stigma surrounding the phenomenon that inhibits people from seeking help. This phenomenon cannot be written off as culturally defined because it is spreading to many parts of the world. With the technology we now have, and mental health issues on the rise and expected to increase even more so after feeling the effects of the current pandemic, I think we will definitely see a rise in the number of people engaging in this social isolation, especially with the increase in legitimate fears we now face that appear to justify the previously considered irrational fears many have associated with social gatherings. We now have the perfect sample of people to provide answers about how this form of isolation can affect people over time.

Likewise, with the advancements we have made to technology not only is it now possible to survive without ever leaving the confines of your own home, but it also makes it possible for us to “fulfill” many of our social interaction needs. It’s very unfortunate, but in addition to the success we have gained through our advancements we have also experienced a great loss. With new technology, I am afraid that we no longer engage with others the way we once did. Although some may say the advancements are for the best, I wonder, at what cost? It is now commonplace to see a phone on the table during a business meeting or first date. Even worse is how many will feel inclined to check their phone during important or meaningful interactions they are having with people face to face. While our technology has become smarter, we have become dumber when it comes to social etiquette. As we all now constantly carry a mini computer with us everywhere we go, we have in essence replaced our best friends. We push others away subconsciously as we reach for our phones during conversations. We no longer remember phone numbers because we have them all saved in our phones. We find comfort in looking down at our phones during those moments of free time we have in public places before our meetings begin. These same moments were once the perfect time to make friends, filled with interactive banter. We now prefer to stare at other people on our phones for hours on end, and often live a sedentary lifestyle instead of going out and interacting with others ourselves.

These are just a few among many issues the advances to technology led to long ago. We have forgotten how to practice proper tech-etiquette and we have been inadvertently practicing social distancing long before it was ever required. Now is a perfect time for us to look at the society we have become and how we incurred a different kind of pandemic long before the one we currently face. With time, as the social distancing regulations begin to lift, people may possibly begin to appreciate life and connecting with others more than they did before as a result of the unique experience we have shared in together while apart.

Maybe the world needed a time-out to remember how to appreciate what it had but forgot to experience. Life is to be lived through experience, not to be used as a pastime to observe and compare oneself with others. I’ll leave you with a simple reminder: never forget to take care and love more because in a world where life is often unpredictable and ever changing, one cannot risk taking time or loved ones for granted. With that, I bid you farewell, fellow comrades, like all else, this too shall pass, now go live your best life!

Privilege in a Pandemic

Covid-19 has impacted millions of Americans who have been out of work for weeks, thus creating a financial burden. Without a job and the certainty of knowing when one will return to work, paying rent and utilities has been a problem for many. With unemployment on the rise, relying on unemployment benefits has become a necessity for millions of people. According to the Washington Post , unemployment rose to 14.7% in April which is considered to be the worst since the Great Depression.

Those who are not worried about the financial aspect or the thought never crossed their minds have privilege. Merriam Webster defines privilege as “a right or immunity granted as a peculiar benefit, advantage, or favor.” Privilege can have a negative connotation. What you choose to do with your privilege is what matters. Talking about privilege can bring discomfort, but the discomfort it brings can also carry the benefit of drawing awareness to one’s privilege, which can lead the person to take steps to help others.

I am a first-generation college student who recently transferred to a four-year university. When schools began to close, and students had to leave their on-campus housing, many lost their jobs.I was able to stay on campus because I live in an apartment. I am fortunate to still have a job, although the hours are minimal. My parents help pay for school expenses, including housing, tuition, and food. I do not have to worry about paying rent or how to pay for food because my parents are financially stable to help me. However, there are millions of college students who are not financially stable or do not have the support system I have. Here, I have the privilege and, thus, I am the one who can offer help to others. I may not have millions in funding, but volunteering for centers who need help is where I am able to help. Those who live in California can volunteer through Californians For All or at food banks, shelter facilities, making calls to seniors, etc.

I was not aware of my privilege during these times until I started reading more articles about how millions of people cannot afford to pay their rent, and landlords are starting to send notices of violations. Rather than feel guilty and be passive about it, I chose to put my privilege into a sense of purpose: Donating to nonprofits helping those affected by COVID-19, continuing to support local businesses, and supporting businesses who are donating profits to those affected by COVID-19.

My World is Burning

As I write this, my friends are double checking our medical supplies and making plans to buy water and snacks to pass out at the next protest we are attending. We write down the number for the local bailout fund on our arms and pray that we’re lucky enough not to have to use it should things get ugly. We are part of a pivotal event, the kind of movement that will forever have a place in history. Yet, during this revolution, I have papers to write and grades to worry about, as I’m in the midst of finals.

My professors have offered empty platitudes. They condemn the violence and acknowledge the stress and pain that so many of us are feeling, especially the additional weight that this carries for students of color. I appreciate their show of solidarity, but it feels meaningless when it is accompanied by requests to complete research reports and finalize presentations. Our world is on fire. Literally. On my social media feeds, I scroll through image after image of burning buildings and police cars in flames. How can I be asked to focus on school when my community is under siege? When police are continuing to murder black people, adding additional names to the ever growing list of their victims. Breonna Taylor. Ahmaud Arbery. George Floyd. David Mcatee. And, now, Rayshard Brooks.

It already felt like the world was being asked of us when the pandemic started and classes continued. High academic expectations were maintained even when students now faced the challenges of being locked down, often trapped in small spaces with family or roommates. Now we are faced with another public health crisis in the form of police violence and once again it seems like educational faculty are turning a blind eye to the impact that this has on the students. I cannot study for exams when I am busy brushing up on my basic first-aid training, taking notes on the best techniques to stop heavy bleeding and treat chemical burns because at the end of the day, if these protests turn south, I will be entering a warzone. Even when things remain peaceful, there is an ugliness that bubbles just below the surface. When beginning the trek home, I have had armed members of the National Guard follow me and my friends. While kneeling in silence, I have watched police officers cock their weapons and laugh, pointing out targets in the crowd. I have been emailing my professors asking for extensions, trying to explain that if something is turned in late, it could be the result of me being detained or injured. I don’t want to be penalized for trying to do what I wholeheartedly believe is right.

I have spent my life studying and will continue to study these institutions that have been so instrumental in the oppression and marginalization of black and indigenous communities. Yet, now that I have the opportunity to be on the frontlines actively fighting for the change our country so desperately needs, I feel that this study is more of a hindrance than a help to the cause. Writing papers and reading books can only take me so far and I implore that professors everywhere recognize that requesting their students split their time and energy between finals and justice is an impossible ask.

Opportunity to Serve

Since the start of the most drastic change of our lives, I have had the privilege of helping feed more than 200 different families in the Santa Ana area and even some neighboring cities. It has been an immense pleasure seeing the sheer joy and happiness of families as they come to pick up their box of food from our site, as well as a $50 gift card to Northgate, a grocery store in Santa Ana. Along with donating food and helping feed families, the team at the office, including myself, have dedicated this time to offering psychosocial and mental health check-ups for the families we serve.

Every day I go into the office I start my day by gathering files of our families we served between the months of January, February, and March and calling them to check on how they are doing financially, mentally, and how they have been affected by COVID-19. As a side project, I have been putting together Excel spreadsheets of all these families’ struggles and finding a way to turn their situation into a success story to share with our board at PY-OCBF and to the community partners who make all of our efforts possible. One of the things that has really touched me while working with these families is how much of an impact this nonprofit organization truly has on family’s lives. I have spoken with many families who I just call to check up on and it turns into an hour call sharing about how much of a change they have seen in their child who went through our program. Further, they go on to discuss that because of our program, their children have a different perspective on the drugs they were using before and the group of friends they were hanging out with. Of course, the situation is different right now as everyone is being told to stay at home; however, there are those handful of kids who still go out without asking for permission, increasing the likelihood they might contract this disease and pass it to the rest of the family. We are working diligently to provide support for these parents and offering advice to talk to their kids in order to have a serious conversation with their kids so that they feel heard and validated.

Although the novel Coronavirus has impacted the lives of millions of people not just on a national level, but on a global level, I feel that in my current position, it has opened doors for me that would have otherwise not presented themselves. Fortunately, I have been offered a full-time position at the Project Youth Orange County Bar Foundation post-graduation that I have committed to already. This invitation came to me because the organization received a huge grant for COVID-19 relief to offer to their staff and since I was already part-time, they thought I would be a good fit to join the team once mid-June comes around. I was very excited and pleased to be recognized for the work I have done at the office in front of all staff. I am immensely grateful for this opportunity. I will work even harder to provide for the community and to continue changing the lives of adolescents, who have steered off the path of success. I will use my time as a full-time employee to polish my resume, not forgetting that the main purpose of my moving to Irvine was to become a scholar and continue the education that my parents couldn’t attain. I will still be looking for ways to get internships with other fields within criminology. One specific interest that I have had since being an intern and a part-time employee in this organization is the work of the Orange County Coroner’s Office. I don’t exactly know what enticed me to find it appealing as many would say that it is an awful job in nature since it relates to death and seeing people in their worst state possible. However, I feel that the only way for me to truly know if I want to pursue such a career in forensic science will be to just dive into it and see where it takes me.

I can, without a doubt, say that the Coronavirus has impacted me in a way unlike many others, and for that I am extremely grateful. As I continue working, I can also state that many people are becoming more and more hopeful as time progresses. With people now beginning to say Stage Two of this stay-at-home order is about to allow retailers and other companies to begin doing curbside delivery, many families can now see some light at the end of the tunnel.

Let’s Do Better

This time of the year is meant to be a time of celebration; however, it has been difficult to feel proud or excited for many of us when it has become a time of collective mourning and sorrow, especially for the Black community. There has been an endless amount of pain, rage, and helplessness that has been felt throughout our nation because of the growing list of Black lives we have lost to violence and brutality.

To honor the lives that we have lost, George Floyd, Tony McDade, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Eric Garner, Oscar Grant, Michael Brown, Trayon Martin, and all of the other Black lives that have been taken away, may they Rest in Power.

Throughout my college experience, I have become more exposed to the various identities and the upbringings of others, which led to my own self-reflection on my own privileged and marginalized identities. I identify as Colombian, German, and Mexican; however navigating life as a mixed race, I have never been able to identify or have one culture more salient than the other. I am visibly white-passing and do not hold any strong ties with any of my ethnic identities, which used to bring me feelings of guilt and frustration, for I would question whether or not I could be an advocate for certain communities, and whether or not I could claim the identity of a woman of color. In the process of understanding my positionality, I began to wonder what space I belonged in, where I could speak up, and where I should take a step back for others to speak. I found myself in a constant theme of questioning what is my narrative and slowly began to realize that I could not base it off lone identities and that I have had the privilege to move through life without my identities defining who I am. Those initial feelings of guilt and confusion transformed into growth, acceptance, and empowerment.

This journey has driven me to educate myself more about the social inequalities and injustices that people face and to focus on what I can do for those around me. It has motivated me to be more culturally responsive and competent, so that I am able to best advocate for those around me. Through the various roles I have worked in, I have been able to listen to a variety of communities’ narratives and experiences, which has allowed me to extend my empathy to these communities while also pushing me to continue educating myself on how I can best serve and empower them. By immersing myself amongst different communities, I have been given the honor of hearing others’ stories and experiences, which has inspired me to commit myself to support and empower others.

I share my story of navigating through my privileged and marginalized identities in hopes that it encourages others to explore their own identities. This journey is not an easy one, and it is an ongoing learning process that will come with various mistakes. I have learned that with facing our privileges comes feelings of guilt, discomfort, and at times, complacency. It is very easy to become ignorant when we are not affected by different issues, but I challenge those who read this to embrace the discomfort. With these emotions, I have found it important to reflect on the source of discomfort and guilt, for although they are a part of the process, in taking the steps to become more aware of the systemic inequalities around us, understanding the source of discomfort can better inform us on how we perpetuate these systemic inequalities. If we choose to embrace ignorance, we refuse to acknowledge the systems that impact marginalized communities and refuse to honestly and openly hear cries for help. If we choose our own comfort over the lives of those being affected every day, we can never truly honor, serve, or support these communities.

I challenge any non-Black person, including myself, to stop remaining complacent when injustices are committed. We need to consistently recognize and acknowledge how the Black community is disproportionately affected in every injustice experienced and call out anti-Blackness in every role, community, and space we share. We need to keep ourselves and others accountable when we make mistakes or fall back into patterns of complacency or ignorance. We need to continue educating ourselves instead of relying on the emotional labor of the Black community to continuously educate us on the history of their oppressions. We need to collectively uplift and empower one another to heal and rise against injustice. We need to remember that allyship ends when action ends.

To the Black community, you are strong. You deserve to be here. The recent events are emotionally, mentally, and physically exhausting, and the need for rest to take care of your mental, physical, and emotional well-being are at an all time high. If you are able, take the time to regain your energy, feel every emotion, and remind yourself of the power you have inside of you. You are not alone.

The Virus That Makes You Forget

Following Jan. 1 of 2020 many of my classmates and I continued to like, share, and forward the same meme. The meme included any image but held the same phrase: I can see 2020. For many of us, 2020 was a beacon of hope. For the Class of 2020, this meant walking on stage in front of our families. Graduation meant becoming an adult, finding a job, or going to graduate school. No matter what we were doing in our post-grad life, we were the new rising stars ready to take on the world with a positive outlook no matter what the future held. We felt that we had a deal with the universe that we were about to be noticed for our hard work, our hardships, and our perseverance.

Then March 17 of 2020 came to pass with California Gov. Newman ordering us to stay at home, which we all did. However, little did we all know that the world we once had open to us would only be forgotten when we closed our front doors.

Life became immediately uncertain and for many of us, that meant graduation and our post-graduation plans including housing, careers, education, food, and basic standards of living were revoked! We became the forgotten — a place from which many of us had attempted to rise by attending university. The goals that we were told we could set and the plans that we were allowed to make — these were crushed before our eyes.

Eighty days before graduation, in the first several weeks of quarantine, I fell extremely ill; both unfortunately and luckily, I was isolated. All of my roommates had moved out of the student apartments leaving me with limited resources, unable to go to the stores to pick up medicine or food, and with insufficient health coverage to afford a doctor until my throat was too swollen to drink water. For nearly three weeks, I was stuck in bed, I was unable to apply to job deadlines, reach out to family, and have contact with the outside world. I was forgotten.

Forty-five days before graduation, I had clawed my way out of illness and was catching up on an honors thesis about media depictions of sexual exploitation within the American political system, when I was relayed the news that democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden was accused of sexual assault. However, when reporting this news to close friends who had been devastated and upset by similar claims against past politicians, they all were too tired and numb from the quarantine to care. Just as I had written hours before reading the initial story, history was repeating, and it was not only I who COVID-19 had forgotten, but now survivors of violence.

After this revelation, I realize the silencing factor that COVID-19 has. Not only does it have the power to terminate the voices of our older generations, but it has the power to silence and make us forget the voices of every generation. Maybe this is why social media usage has gone up, why we see people creating new social media accounts, posting more, attempting to reach out to long lost friends. We do not want to be silenced, moreover, we cannot be silenced. Silence means that we have been forgotten and being forgotten is where injustice and uncertainty occurs. By using social media, pressing like on a post, or even sending a hate message, means that someone cares and is watching what you are doing. If there is no interaction, I am stuck in the land of indifference.

This is a place that I, and many others, now reside, captured and uncertain. In 2020, my plan was to graduate Cum Laude, dean's honor list, with three honors programs, three majors, and with research and job experience that stretched over six years. I would then go into my first year of graduate school, attempting a dual Juris Doctorate. I would be spending my time experimenting with new concepts, new experiences, and new relationships. My life would then be spent giving a microphone to survivors of domestic violence and sex crimes. However, now the plan is wiped clean, instead I sit still bound to graduate in 30 days with no home to stay, no place to work, and no future education to come back to. I would say I am overly qualified, but pandemic makes me lost in a series of names and masked faces.

Welcome to My Cage: The Pandemic and PTSD

When I read the campuswide email notifying students of the World Health Organization’s declaration of the coronavirus pandemic, I was sitting on my couch practicing a research presentation I was going to give a few hours later. For a few minutes, I sat there motionless, trying to digest the meaning of the words as though they were from a language other than my own, familiar sounds strung together in way that was wholly unintelligible to me. I tried but failed to make sense of how this could affect my life. After the initial shock had worn off, I mobilized quickly, snapping into an autopilot mode of being I knew all too well. I began making mental checklists, sharing the email with my friends and family, half of my brain wondering if I should make a trip to the grocery store to stockpile supplies and the other half wondering how I was supposed take final exams in the midst of so much uncertainty. The most chilling realization was knowing I had to wait powerlessly as the fate of the world unfolded, frozen with anxiety as I figured out my place in it all.

These feelings of powerlessness and isolation are familiar bedfellows for me. Early October of 2015, shortly after beginning my first year at UCI, I was diagnosed with Post-traumatic Stress Disorder. Despite having had years of psychological treatment for my condition, including Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Eye Movement Desensitization and Retraining, the flashbacks, paranoia, and nightmares still emerge unwarranted. People have referred to the pandemic as a collective trauma. For me, the pandemic has not only been a collective trauma, it has also been the reemergence of a personal trauma. The news of the pandemic and the implications it has for daily life triggered a reemergence of symptoms that were ultimately ignited by the overwhelming sense of helplessness that lies in waiting, as I suddenly find myself navigating yet another situation beyond my control. Food security, safety, and my sense of self have all been shaken by COVID-19.

The first few weeks after UCI transitioned into remote learning and the governor issued the stay-at-home order, I hardly got any sleep. My body was cycling through hypervigilance and derealization, and my sleep was interrupted by intrusive nightmares oscillating between flashbacks and frightening snippets from current events. Any coping methods I had developed through hard-won efforts over the past few years — leaving my apartment for a change of scenery, hanging out with friends, going to the gym — were suddenly made inaccessible to me due to the stay-at-home orders, closures of non-essential businesses, and many of my friends breaking their campus leases to move back to their family homes. So for me, learning to cope during COVID-19 quarantine means learning to function with my re-emerging PTSD symptoms and without my go-to tools. I must navigate my illness in a rapidly evolving world, one where some of my internalized fears, such as running out of food and living in an unsafe world, are made progressively more external by the minute and broadcasted on every news platform; fears that I could no longer escape, being confined in the tight constraints of my studio apartment’s walls. I cannot shake the devastating effects of sacrifice that I experience as all sense of control has been stripped away from me.

However, amidst my mental anguish, I have realized something important—experiencing these same PTSD symptoms during a global pandemic feels markedly different than it did years ago. Part of it might be the passage of time and the growth in my mindset, but there is something else that feels very different. Currently, there is widespread solidarity and support for all of us facing the chaos of COVID-19, whether they are on the frontlines of the fight against the illness or they are self-isolating due to new rules, restrictions, and risks. This was in stark contrast to what it was like to have a mental disorder. The unity we all experience as a result of COVID-19 is one I could not have predicted. I am not the only student heartbroken over a cancelled graduation, I am not the only student who is struggling to adapt to remote learning, and I am not the only person in this world who has to make sacrifices.

Between observations I’ve made on social media and conversations with my friends and classmates, this time we are all enduring great pain and stress as we attempt to adapt to life’s challenges. As a Peer Assistant for an Education class, I have heard from many students of their heartache over the remote learning model, how difficult it is to study in a non-academic environment, and how unmotivated they have become this quarter. This is definitely something I can relate to; as of late, it has been exceptionally difficult to find motivation and put forth the effort for even simple activities as a lack of energy compounds the issue and hinders basic needs. However, the willingness of people to open up about their distress during the pandemic is unlike the self-imposed social isolation of many people who experience mental illness regularly. Something this pandemic has taught me is that I want to live in a world where mental illness receives more support and isn’t so taboo and controversial. Why is it that we are able to talk about our pain, stress, and mental illness now, but aren’t able to talk about it outside of a global pandemic? People should be able to talk about these hardships and ask for help, much like during these circumstances.

It has been nearly three months since the coronavirus crisis was declared a pandemic. I still have many bad days that I endure where my symptoms can be overwhelming. But somehow, during my good days — and some days, merely good moments — I can appreciate the resilience I have acquired over the years and the common ground I share with others who live through similar circumstances. For veterans of trauma and mental illness, this isn’t the first time we are experiencing pain in an extreme and disastrous way. This is, however, the first time we are experiencing it with the rest of the world. This strange new feeling of solidarity as I read and hear about the experiences of other people provides some small comfort as I fight my way out of bed each day. As we fight to survive this pandemic, I hope to hold onto this feeling of togetherness and acceptance of pain, so that it will always be okay for people to share their struggles. We don’t know what the world will look like days, months, or years from now, but I hope that we can cultivate such a culture to make life much easier for people coping with mental illness.

A Somatic Pandemonium in Quarantine

I remember hearing that our brains create the color magenta all on their own.

When I was younger I used to run out of my third-grade class because my teacher was allergic to the mold and sometimes would vomit in the trash can. My dad used to tell me that I used to always have to have something in my hands, later translating itself into the form of a hair tie around my wrist.

Sometimes, I think about the girl who used to walk on her tippy toes. medial and lateral nerves never planted, never grounded. We were the same in this way. My ability to be firmly planted anywhere was also withered.

Was it from all the times I panicked? Or from the time I ran away and I blistered the soles of my feet 'til they were black from the summer pavement? Emetophobia.

I felt it in the shower, dressing itself from the crown of my head down to the soles of my feet, noting the feeling onto my white board in an attempt to solidify it’s permanence.

As I breathed in the chemical blue transpiring from the Expo marker, everything was more defined. I laid down and when I looked up at the starlet lamp I had finally felt centered. Still. No longer fleeting. The grooves in the lamps glass forming a spiral of what felt to me like an artificial landscape of transcendental sparks.

She’s back now, magenta, though I never knew she left or even ever was. Somehow still subconsciously always known. I had been searching for her in the tremors.

I can see her now in the daphnes, the golden rays from the sun reflecting off of the bark on the trees and the red light that glowed brighter, suddenly the town around me was warmer. A melting of hues and sharpened saturation that was apparent and reminded of the smell of oranges.

I threw up all of the carrots I ate just before. The trauma that my body kept as a memory of things that may or may not go wrong and the times that I couldn't keep my legs from running. Revelations bring memories bringing anxieties from fear and panic released from my body as if to say “NO LONGER!”

I close my eyes now and my mind's eye is, too, more vivid than ever before. My inner eyelids lit up with orange undertones no longer a solid black, neurons firing, fire. Not the kind that burns you but the kind that can light up a dull space. Like the wick of a tea-lit candle. Magenta doesn’t exist. It is perception. A construct made of light waves, blue and red.

Demolition. Reconstruction. I walk down the street into this new world wearing my new mask, somatic senses tingling and I think to myself “Houston, I think we’ve just hit equilibrium.”

How COVID-19 Changed My Senior Year

During the last two weeks of Winter quarter, I watched the emails pour in. Spring quarter would be online, facilities were closing, and everyone was recommended to return home to their families, if possible. I resolved to myself that I would not move back home; I wanted to stay in my apartment, near my boyfriend, near my friends, and in the one place I had my own space. However, as the COVID-19 pandemic worsened, things continued to change quickly. Soon I learned my roommate/best friend would be cancelling her lease and moving back up to Northern California. We had made plans for my final quarter at UCI, as I would be graduating in June while she had another year, but all of the sudden, that dream was gone. In one whirlwind of a day, we tried to cram in as much of our plans as we could before she left the next day for good. There are still so many things – like hiking, going to museums, and showing her around my hometown – we never got to cross off our list.

Then, my boyfriend decided he would also be moving home, three hours away. Most of my sorority sisters were moving home, too. I realized if I stayed at school, I would be completely alone. My mom had been encouraging me to move home anyway, but I was reluctant to return to a house I wasn’t completely comfortable in. As the pandemic became more serious, gentle encouragement quickly turned into demands. I had to cancel my lease and move home.

I moved back in with my parents at the end of Spring Break; I never got to say goodbye to most of my friends, many of whom I’ll likely never see again – as long as the virus doesn’t change things, I’m supposed to move to New York over the summer to begin a PhD program in Criminal Justice. Just like that, my time at UCI had come to a close. No lasts to savor; instead I had piles of things to regret. In place of a final quarter filled with memorable lasts, such as the senior banquet or my sorority’s senior preference night, I’m left with a laundry list of things I missed out on. I didn’t get to look around the campus one last time like I had planned; I never got to take my graduation pictures in front of the UC Irvine sign. Commencement had already been cancelled. The lights had turned off in the theatre before the movie was over. I never got to find out how the movie ended.

Transitioning to a remote learning system wasn’t too bad, but I found that some professors weren’t adjusting their courses to the difficulties many students were facing. It turned out to be difficult to stay motivated, especially for classes that are pre-recorded and don’t have any face-to-face interaction. It’s hard to make myself care; I’m in my last few weeks ever at UCI, but it feels like I’m already in summer. School isn’t real, my classes aren’t real. I still put in the effort, but I feel like I’m not getting much out of my classes.

The things I had been looking forward to this quarter are gone; there will be no Undergraduate Research Symposium, where I was supposed to present two projects. My amazing internship with the US Postal Inspection Service is over prematurely and I never got to properly say goodbye to anyone I met there. I won’t receive recognition for the various awards and honors I worked so hard to achieve.

And I’m one of the lucky ones! I feel guilty for feeling bad about my situation, when I know there are others who have it much, much worse. I am like that quintessential spoiled child, complaining while there are essential workers working tirelessly, people with health concerns constantly fearing for their safety, and people dying every day. Yet knowing that doesn't help me from feeling I was robbed of my senior experience, something I worked very hard to achieve. I know it’s not nearly as important as what many others are going through. But nevertheless, this is my situation. I was supposed to be enjoying this final quarter with my friends and preparing to move on, not be stuck at home, grappling with my mental health and hiding out in my room to get some alone time from a family I don’t always get along with. And while I know it’s more difficult out there for many others, it’s still difficult for me.

The thing that stresses me out most is the uncertainty. Uncertainty for the future – how long will this pandemic last? How many more people have to suffer before things go back to “normal” – whatever that is? How long until I can see my friends and family again? And what does this mean for my academic future? Who knows what will happen between now and then? All that’s left to do is wait and hope that everything will work out for the best.

Looking back over my last few months at UCI, I wish I knew at the time that I was experiencing my lasts; it feels like I took so much for granted. If there is one thing this has all made me realize, it’s that nothing is certain. Everything we expect, everything we take for granted – none of it is a given. Hold on to what you have while you have it, and take the time to appreciate the wonderful things in life, because you never know when it will be gone.

Physical Distancing

Thirty days have never felt so long. April has been the longest month of the year. I have been through more in these past three months than in the past three years. The COVID-19 outbreak has had a huge impact on both physical and social well-being of a lot of Americans, including me. Stress has been governing the lives of so many civilians, in particular students and workers. In addition to causing a lack of motivation in my life, quarantine has also brought a wave of anxiety.

My life changed the moment the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention and the government announced social distancing. My busy daily schedule, running from class to class and meeting to meeting, morphed into identical days, consisting of hour after hour behind a cold computer monitor. Human interaction and touch improve trust, reduce fear and increases physical well-being. Imagine the effects of removing the human touch and interaction from midst of society. Humans are profoundly social creatures. I cannot function without interacting and connecting with other people. Even daily acquaintances have an impact on me that is only noticeable once removed. As a result, the COVID-19 outbreak has had an extreme impact on me beyond direct symptoms and consequences of contracting the virus itself.

It was not until later that month, when out of sheer boredom I was scrolling through my call logs and I realized that I had called my grandmother more than ever. This made me realize that quarantine had created some positive impacts on my social interactions as well. This period of time has created an opportunity to check up on and connect with family and peers more often than we were able to. Even though we might be connecting solely through a screen, we are not missing out on being socially connected. Quarantine has taught me to value and prioritize social connection, and to recognize that we can find this type of connection not only through in-person gatherings, but also through deep heart to heart connections. Right now, my weekly Zoom meetings with my long-time friends are the most important events in my week. In fact, I have taken advantage of the opportunity to reconnect with many of my old friends and have actually had more meaningful conversations with them than before the isolation.

This situation is far from ideal. From my perspective, touch and in-person interaction is essential; however, we must overcome all difficulties that life throws at us with the best we are provided with. Therefore, perhaps we should take this time to re-align our motives by engaging in things that are of importance to us. I learned how to dig deep and find appreciation for all the small talks, gatherings, and face-to-face interactions. I have also realized that friendships are not only built on the foundation of physical presence but rather on meaningful conversations you get to have, even if they are through a cold computer monitor. My realization came from having more time on my hands and noticing the shift in conversations I was having with those around me. After all, maybe this isolation isn’t “social distancing”, but rather “physical distancing” until we meet again.

Follow us on social media

How to Write About Coronavirus in a College Essay

Students can share how they navigated life during the coronavirus pandemic in a full-length essay or an optional supplement.

Writing About COVID-19 in College Essays

Getty Images

Experts say students should be honest and not limit themselves to merely their experiences with the pandemic.

The global impact of COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, means colleges and prospective students alike are in for an admissions cycle like no other. Both face unprecedented challenges and questions as they grapple with their respective futures amid the ongoing fallout of the pandemic.

Colleges must examine applicants without the aid of standardized test scores for many – a factor that prompted many schools to go test-optional for now . Even grades, a significant component of a college application, may be hard to interpret with some high schools adopting pass-fail classes last spring due to the pandemic. Major college admissions factors are suddenly skewed.

"I can't help but think other (admissions) factors are going to matter more," says Ethan Sawyer, founder of the College Essay Guy, a website that offers free and paid essay-writing resources.

College essays and letters of recommendation , Sawyer says, are likely to carry more weight than ever in this admissions cycle. And many essays will likely focus on how the pandemic shaped students' lives throughout an often tumultuous 2020.

But before writing a college essay focused on the coronavirus, students should explore whether it's the best topic for them.

Writing About COVID-19 for a College Application

Much of daily life has been colored by the coronavirus. Virtual learning is the norm at many colleges and high schools, many extracurriculars have vanished and social lives have stalled for students complying with measures to stop the spread of COVID-19.

"For some young people, the pandemic took away what they envisioned as their senior year," says Robert Alexander, dean of admissions, financial aid and enrollment management at the University of Rochester in New York. "Maybe that's a spot on a varsity athletic team or the lead role in the fall play. And it's OK for them to mourn what should have been and what they feel like they lost, but more important is how are they making the most of the opportunities they do have?"

That question, Alexander says, is what colleges want answered if students choose to address COVID-19 in their college essay.

But the question of whether a student should write about the coronavirus is tricky. The answer depends largely on the student.

"In general, I don't think students should write about COVID-19 in their main personal statement for their application," Robin Miller, master college admissions counselor at IvyWise, a college counseling company, wrote in an email.

"Certainly, there may be exceptions to this based on a student's individual experience, but since the personal essay is the main place in the application where the student can really allow their voice to be heard and share insight into who they are as an individual, there are likely many other topics they can choose to write about that are more distinctive and unique than COVID-19," Miller says.

Opinions among admissions experts vary on whether to write about the likely popular topic of the pandemic.

"If your essay communicates something positive, unique, and compelling about you in an interesting and eloquent way, go for it," Carolyn Pippen, principal college admissions counselor at IvyWise, wrote in an email. She adds that students shouldn't be dissuaded from writing about a topic merely because it's common, noting that "topics are bound to repeat, no matter how hard we try to avoid it."

Above all, she urges honesty.

"If your experience within the context of the pandemic has been truly unique, then write about that experience, and the standing out will take care of itself," Pippen says. "If your experience has been generally the same as most other students in your context, then trying to find a unique angle can easily cross the line into exploiting a tragedy, or at least appearing as though you have."

But focusing entirely on the pandemic can limit a student to a single story and narrow who they are in an application, Sawyer says. "There are so many wonderful possibilities for what you can say about yourself outside of your experience within the pandemic."

He notes that passions, strengths, career interests and personal identity are among the multitude of essay topic options available to applicants and encourages them to probe their values to help determine the topic that matters most to them – and write about it.

That doesn't mean the pandemic experience has to be ignored if applicants feel the need to write about it.

Writing About Coronavirus in Main and Supplemental Essays

Students can choose to write a full-length college essay on the coronavirus or summarize their experience in a shorter form.

To help students explain how the pandemic affected them, The Common App has added an optional section to address this topic. Applicants have 250 words to describe their pandemic experience and the personal and academic impact of COVID-19.

"That's not a trick question, and there's no right or wrong answer," Alexander says. Colleges want to know, he adds, how students navigated the pandemic, how they prioritized their time, what responsibilities they took on and what they learned along the way.

If students can distill all of the above information into 250 words, there's likely no need to write about it in a full-length college essay, experts say. And applicants whose lives were not heavily altered by the pandemic may even choose to skip the optional COVID-19 question.

"This space is best used to discuss hardship and/or significant challenges that the student and/or the student's family experienced as a result of COVID-19 and how they have responded to those difficulties," Miller notes. Using the section to acknowledge a lack of impact, she adds, "could be perceived as trite and lacking insight, despite the good intentions of the applicant."

To guard against this lack of awareness, Sawyer encourages students to tap someone they trust to review their writing , whether it's the 250-word Common App response or the full-length essay.

Experts tend to agree that the short-form approach to this as an essay topic works better, but there are exceptions. And if a student does have a coronavirus story that he or she feels must be told, Alexander encourages the writer to be authentic in the essay.

"My advice for an essay about COVID-19 is the same as my advice about an essay for any topic – and that is, don't write what you think we want to read or hear," Alexander says. "Write what really changed you and that story that now is yours and yours alone to tell."