Critical Thinking

- What is Critical Thinking?

- Intellectual Standards

- Elements of Thought

Intellectual Traits

- Intellectual Traits - What Are My Intellectual Habits?

Critical Thinking and The Intellectual Traits by Dr. Richard Paul

Quiz yourself on intellectual traits.

- Helpful Resources

- Cite Sources Accurately

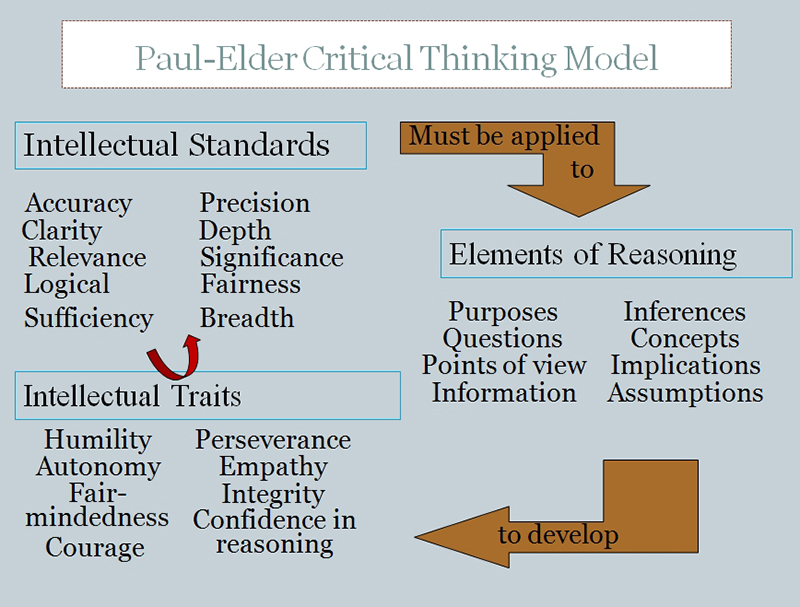

If standards of thought are applied, a student has potential to grow into an individual who exhibits the intellectual character described by the Paul- Elder Intellectual Traits. These intellectual traits include intellectual integrity, independence, perseverance, empathy, humility, courage, confidence in reason and fair-mindedness (Figure 1). - By Crest + Oral-B Professional Community

Intellectual integrity – this trait requires that the standards that guide actions and thoughts need to be the same standards by which others are evaluated. an individual exhibiting this trait treats others with kindness while avoiding harm and outwardly projects this trait. this trait eliminates double standards and hypocrisy., intellectual autonomy – this trait requires an individual to use critical thinking tools, such as the paul-elder model, and to trust their own ability to reason critically. for example, a dental professional exhibiting intellectual autonomy will ask questions about new products and will critically think through all aspects of the products to determine their implications of use. these individuals do not have to rely on others to do their thinking., intellectual perseverance – the tag phase for this trait is "never give up" and encourages individuals to work through any difficulties. a clinician exhibiting intellectual perseverance has to depend on their critical thinking toolkit to keep working through challenging patient issues or unfamiliar situations., intellectual empathy – an individual achieves intellectual empathy when they actively put themselves in someone else’s shoes in terms of how they think and feel. for instance, a dental clinician may encounter a patient who has a different viewpoint about certain dental preventive agents such as fluoride. a clinician exhibiting intellectual empathy strives to understand the patient’s point of view in order to think fully about the situation before responding to it. while the clinician does not have to agree with your patient’s point of view, intellectual empathy demands that they accurately represent the thinking of a different view despite what they believe., intellectual humility – individuals exhibiting intellectual humility accept they are human and that they do not know everything. they continue to learn and grow as they age. they acknowledge their limitations. dental professionals exhibiting intellectual humility are okay to tell patients they are not familiar with a certain product, technique, condition or research behind the product or technique, and acknowledge that they are an ongoing learner in the profession., intellectual courage – individuals with intellectual courage stand up for their beliefs and the conclusions they have fully thought through, especially when it is difficult to do so. sometimes it will not be a popular or common thought, but if they stand up for their beliefs, change can occur., confidence in reason and fair-mindedness - utilizing the elements of thought and the standards will lead to confidence in reason and fair-mindedness and requires individuals to look at all of the evidence and relevant points of views and arrive at conclusions that embodies the intellectual traits. this allows dental professionals with confidence in reason and fair-mindedness to trust, as thinkers, to come to sound conclusions for patient care simply by applying the framework to their thought process. 2-6.

Dr. Richard Paul briefly defines and discusses the Intellectual Traits and the importance of fostering their development in students. Excerpted from the Spring 2008 Workshop on Teaching for Intellectual Engagement. Apr 15, 2008 - (9:53)

- Quizlet on Intellectual Traits of Critical Thinking

- << Previous: Elements of Thought

- Next: Helpful Resources >>

- Last Updated: Jan 22, 2024 6:00 PM

- URL: https://paradisevalley.libguides.com/critical_thinking

- Programs & Services

- Delphi Center

Ideas to Action (i2a)

- Paul-Elder Critical Thinking Framework

Critical thinking is that mode of thinking – about any subject, content, or problem — in which the thinker improves the quality of his or her thinking by skillfully taking charge of the structures inherent in thinking and imposing intellectual standards upon them. (Paul and Elder, 2001). The Paul-Elder framework has three components:

- The elements of thought (reasoning)

- The intellectual standards that should be applied to the elements of reasoning

- The intellectual traits associated with a cultivated critical thinker that result from the consistent and disciplined application of the intellectual standards to the elements of thought

According to Paul and Elder (1997), there are two essential dimensions of thinking that students need to master in order to learn how to upgrade their thinking. They need to be able to identify the "parts" of their thinking, and they need to be able to assess their use of these parts of thinking.

Elements of Thought (reasoning)

The "parts" or elements of thinking are as follows:

- All reasoning has a purpose

- All reasoning is an attempt to figure something out, to settle some question, to solve some problem

- All reasoning is based on assumptions

- All reasoning is done from some point of view

- All reasoning is based on data, information and evidence

- All reasoning is expressed through, and shaped by, concepts and ideas

- All reasoning contains inferences or interpretations by which we draw conclusions and give meaning to data

- All reasoning leads somewhere or has implications and consequences

Universal Intellectual Standards

The intellectual standards that are to these elements are used to determine the quality of reasoning. Good critical thinking requires having a command of these standards. According to Paul and Elder (1997 ,2006), the ultimate goal is for the standards of reasoning to become infused in all thinking so as to become the guide to better and better reasoning. The intellectual standards include:

Intellectual Traits

Consistent application of the standards of thinking to the elements of thinking result in the development of intellectual traits of:

- Intellectual Humility

- Intellectual Courage

- Intellectual Empathy

- Intellectual Autonomy

- Intellectual Integrity

- Intellectual Perseverance

- Confidence in Reason

- Fair-mindedness

Characteristics of a Well-Cultivated Critical Thinker

Habitual utilization of the intellectual traits produce a well-cultivated critical thinker who is able to:

- Raise vital questions and problems, formulating them clearly and precisely

- Gather and assess relevant information, using abstract ideas to interpret it effectively

- Come to well-reasoned conclusions and solutions, testing them against relevant criteria and standards;

- Think open-mindedly within alternative systems of thought, recognizing and assessing, as need be, their assumptions, implications, and practical consequences; and

- Communicate effectively with others in figuring out solutions to complex problems

Paul, R. and Elder, L. (2010). The Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking Concepts and Tools. Dillon Beach: Foundation for Critical Thinking Press.

- SACS & QEP

- Planning and Implementation

- What is Critical Thinking?

- Why Focus on Critical Thinking?

- Culminating Undergraduate Experience

- Community Engagement

- Frequently Asked Questions

- What is i2a?

Copyright © 2012 - University of Louisville , Delphi Center

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

8 Perseverance: Overcome Obstacles

- Published: March 2021

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter explores intellectual perseverance, the virtue needed to overcome obstacles to our getting, keeping, and sharing knowledge. After locating perseverance as a virtue between the deficiency of irresolution and the vice of intransigence, the chapter considers the structure of the virtue in greater detail. It argues that perseverance involves a disposition to expend serious effort in order to overcome obstacles to the completion of our intellectual projects—particularly obstacles that make it difficult for us to achieve our intellectual ends. The chapter concludes by relating the notion of intellectual perseverance to recent work on grit, and to the concept of a growth mindset.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

- Google Scholar Indexing

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Are you trying to learn something new but it's a struggle and you're tempted to give up? Are you trying to understand philosophy or level up your thinking and sometimes you just feel stuck and confused? Then this post is designed for you, philosophical lifer! I'm giving you the 5 best steps to develop intellectual perseverance and succeed intellectually.

What is Intellectual Perseverance?

Intellectual perseverance is a habit that comes from a love of learning. It's the tendency to not give up on learning when the learning gets tough. Instead, you embrace intellectual struggle. You persist toward greater understanding.

Intellectual perseverance is an intellectual virtue. What's an intellectual virtue and why is perseverance one of them?

For Aristotle, a virtue is a midway point between two extremes. For instance, moral courage is a virtue that lies in-between the tendency to act cowardly or rashly. A person having the moral virtue of courage takes just the right amount of risk given the circumstances. They do not foolishly rush into a battle when they are clearly outmatched or haven't planned their attack. They do not take unwise risks or act rashly. And they do not retreat from battle out of fear when victory was possible. They do not act cowardly. What's an intellectual virtue as opposed to a moral one?

An intellectual virtue is a habit that comes from a desire to gain knowledge. It involves seeking the truth about what you're learning. But, it isn't an all-out desire for truth no matter the costs. Enter movie quote from A Few Good Men , "You can't handle the truth!" It involves correct moderation. It's a midway point. Between what?

Intellectual perseverance lies in-between the tendency to give up on learning too easily and the tendency to keep banging your head against a problem when no reasonable progress is in sight. However, we tend to give up too easily. So it's usually better to lean toward keeping going.

Now onto developing this awesome intellectual habit!

Step 1: Connect What You're Learning to the Real World!

Develop the habit of intellectual perseverance by connecting your subject to the real world.

Keep learning when the learning gets tough by seeing your subject in 3-D. If a subject is flat and one-dimensional it's boring to look at. When you get bored you tend to move onto something else. Bring your subject to life by connecting it to the real world. How?

Take ethics, for instance. Reading Jeremy Bentham on utilitarianism can be...well...boring. The text is old school.

To make reading utilitarianism come to life you can connect your learning to the real world. There's a movement called Effective Altruism . It's utilitarianism in action. Reading about the movement or attending meetups may keep you engaged in learning about utilitarianism. It will motivate you to keep going even when reading Bentham gets tough or boring.

Step 2: Ignite Your Curiosity!

Spark your curiosity to keep learning when the learning gets tough.

Curious people learn because learning is rewarding. They don't just learn to get kudos or rewards. They learn for learning's sake. Curiosity keeps you focused on this pursuit.

If you find yourself tempted to quit an intellectual project, try to your ignite your curiosity.

Sticking with the example of learning utilitarianism. If you find reading John Stuart Mill on Utilitarianism is difficult you can ignite your curiosity by looking at a general article on utilitarianism, such as this one on The History of Utilitarianism .

Or, if learning about about the history of ideas doesn't spark your curiosity, watch a fun video on your subject. For example, you could watch a video on utilitarianism by Crash Course Philosophy . This helps you think about interesting scenarios relevant to utilitarianism, such as whether it's permissible to kill one person to save five people.

Step 3: Break Free from What's Holding You Back!

There are predicable things that are preventing you from persevering intellectually. Recognize these roadblocks. Don't let them stop you from learning.

Intellectual laziness prevents learning. Learning requires mental effort. If you find yourself unwilling to exert yourself mentally, you're prone to intellectual laziness. Like the habit of physical laziness makes your muscles atrophy the habit of intellectual laziness makes your mind atrophy. It makes your intellectual skills grow dull and flabby.

Another big roadblock is the P-word...procrastination. It involves putting off what's hard by distracting yourself with what's easy and less important in moving your learning forward. Instead of forcing yourself to do what's hard, you occupy yourself with busy work.

Yet another P-word that's a roadblock is perfectionism. This is the one I struggle with most. I tend to fuss over details. I tend to endlessly tweak things. If I cannot learn something and learn it perfectly, I think "why bother." I've learned it's better to take small steps over time than to try to take huge leaps of improvement in one fell swoop. If you're a perfectionist like me, you may be waiting for the perfect moment to learn, the perfect school or teacher, or the perfect method. Get learning and stay learning. Even if it's messy. Even if it's not perfect. It's better to get it done.

The last roadblock to intellectual perseverance I'll mention is closed-mindedness. When you're closed-minded you're unwilling to think outside the box. Learning something new requires going out on a limb. It requires thinking new thoughts. If you are unwilling to entertain new ideas and perspectives, this will make you give up when you encounter something new, especially something that challenges your preexisting beliefs. To overcome this roadblock, become open-minded.

To help you become open-minded I created a video. It contains 3 tips to boost your open-mindedness so you can better learn and think critically. Click here to watch the video.

Step 4: Remember Your Past Intellectual Achievements!

When you're tempted to give up on learning something it's helpful to remember your past successes. Did you succeed in learning a new skill at work? Did you learn a new language? Did you learn a new theory or philosophy? Did you achieve a degree? Did you complete a training course?

On a sheet of paper write down some of your past intellectual successes. Remember these successes. Let them give you strength to keep going because you've done so in the past.

Step 5: Think About Frederick Douglass!

Frederick Douglass went from being a slave to being an adviser to the President. How did he escape slavery and become an activist for the abolition of slavery? He learned to read and write. But, it wasn't easy.

Frederick first learned the alphabet when he was a young boy. The wife of his slave owner and master began teaching him the ABC's. When the slave owner discovered his wife was teaching Frederick to read, he forbid his wife from continuing. But this did not prevent Frederick from persisting in becoming literate. He did not give up.

He used ingenuity to achieve literacy. While running household chores, such as going to the store, Frederick would bring bread with him. He would get poor white boys to spell out words. He would offer them bread in exchange for a spelling lesson.

Frederick learned to write in an ingenuous way. One day while passing by a shipyard he noticed letters on the wood used to build the ships. Carpenters would write in chalk where the wood was to be placed on the ship. Frederick used discarded chalk to practice tracing the letters he found on the wood. It took him a long time to learn. But, his persistence paid off.

Thus, after a long, tedious effort for years, I finally succeeded in learning how to write.

Frederick Douglass

When you're tempted to give up on an intellectual project, think about Frederick Douglass. Think about the ingenuity and perseverance he displayed in learning to read and write. Let that encourage you to find new ways to overcome your struggles in learning.

For a video version of this post, check out the video below!

The 5 steps for developing the habit of intellectual perseverance will help you succeed in your intellectual projects. When the learning gets tough, you will persist through those challenges. In the end, it's worth it. Completing your intellectual projects is satisfying and rewarding. It gives you confidence. It sharpens and expands your mind.

Related Posts

Intellectual Responsibility – The Importance of Admitting Mental Mistakes

3 Smart Strategies to Amplify Your Intellectual Humility

Thinking Skills – If You’re Missing These Skills, Your Thinking Will Fail You

About the Author

I'm a philosopher, content creator, and entrepreneur. I strive to provide entertaining educational experiences that transform your thinking and learning. When I'm not teaching I enjoy taking my fluffy Golden Doodle for walks on the beach and watching movies and TV shows with my wife.

Session expired

Please log in again. The login page will open in a new tab. After logging in you can close it and return to this page.

Westside Toastmasters is located in Los Angeles and Santa Monica, California

Chapter 3. evolving into a balanced critical thinker, chapter 3. evolving into an evenhanded thinker, weak versus strong critical thinking.

Critical thinking involves basic intellectual skills, but these skills can be used to serve two incompatible ends: self-centeredness or fair-mindedness. As we develop the basic intellectual skills that critical thinking entails, we can begin to use those skills in a selfish or in a fair-minded way. In other words, we can develop in such a way that we learn to see mistakes in our own thinking, as well as the thinking of others. Or we can merely develop some proficiency in making our opponent's thinking look bad.

Typically, people see mistakes in other's thinking without being able to credit the strengths in those opposing views. Liberals see mistakes in the arguments of conservatives; conservatives see mistakes in the arguments of liberals. Believers see mistakes in the thinking of nonbelievers; nonbelievers see mistakes in the thinking of believers. Those who oppose abortion readily see mistakes in the arguments for abortion; those who favor abortion readily see mistakes in the arguments against it.

We call these thinkers weak-sense critical thinkers. We call the thinking "weak" because, though it is working well for the thinker in some respects, it is missing certain important higher-level skills and values of critical thinking. Most significantly, it fails to consider, in good faith, viewpoints that contradict its own viewpoint. It lacks fair-mindedness.

Another traditional name for the weak-sense thinker is found in the word sophist. Sophistry is the art of winning arguments regardless of whether there are obvious problems in the thinking being used. There is a set of lower-level skills of rhetoric, or argumentation, by which one can make bad thinking look good and good thinking look bad. We see this often in unethical lawyers and politicians who are merely concerned with winning. They use emotionalism and trickery in an intellectually skilled way.

Sophistic thinkers succeed only if they do not come up against what we call strong-sense critical thinkers. Strong-sense critical thinkers are not easily tricked by slick argumentation. As William Graham Sumner ( -->1906) said almost a century ago, they

cannot be stampeded ... are slow to believe ... can hold things as possible or probable in all degrees, without certainty and without pain ... can wait for evidence and weigh evidence ... can resist appeals to their dearest prejudices....

Perhaps even more important, strong-sense critical thinkers strive to be fair-minded. They use thinking in an ethically responsible manner. They work to understand and appreciate the viewpoints of others. They are willing to listen to arguments they do not necessarily hold. They change their views when faced with better reasoning. Rather than using their thinking to manipulate others and to hide from the truth (in a weak-sense way), they use thinking in an ethical, reasonable manner.

We believe that the world already has too many skilled selfish thinkers, too many sophists and intellectual con artists, too many unscrupulous lawyers and politicians who specialize in twisting information and evidence to support their selfish interests and the vested interests of those who pay them. We hope that you, the reader, will develop as a highly skilled, fair-minded thinker, one capable of exposing those who are masters at playing intellectual games at the expense of the well-being of innocent people. We hope as well that you develop the intellectual courage to argue publicly against what is unethical in human thinking. We write this resource with the assumption that you will take seriously the fair-mindedness implied by strong-sense critical thinking.

To think critically in the strong sense requires that we develop fair-mindedness at the same time that we learn basic critical thinking skills, and thus begin to "practice" fair-mindedness in our thinking. If we do, we avoid using our skills to gain unfair advantage over others. We avoid using our thinking to get what we want at the expense of the rights and needs of others. We treat all thinking by the same high standards. We expect good reasoning from those who support us as well as those who oppose us. We subject our own reasoning to the same criteria we apply to reasoning to which we are unsympathetic. We question our own purposes, evidence, conclusions, implications, and points of view with the same vigor that we question those of others.

Developing fair-minded thinkers try to see the actual strengths and weaknesses of any reasoning they assess. This is the kind of thinker we hope this resource will help you become. So, right from the beginning, we are going to explore the characteristics that are required for the strongest, most fair-minded thinking. As you read through the rest of the book, we hope you will notice how we are attempting to foster "strong-sense" critical thinking. Indeed, unless we indicate otherwise, every time we now use the words "critical thinking," from this point onward, we will mean critical thinking in the strong sense.

In the remainder of this chapter, we will explore the various intellectual "virtues" that fair-minded thinking requires (Figure 3.1) . Figure 3.1 ).--> There is much more to fair-mindedness than most people realize. Fair-mindedness requires a family of interrelated and interdependent states of mind.

Figure 3.1. Critical thinkers strive to develop essential traits or characteristics of mind. These are interrelated intellectual habits that lead to disciplined self-command.

In addition to fair-mindedness, strong-sense critical thinking implies higher-order thinking. As you develop as a thinker and internalize the traits of mind that we shall soon discuss, you will develop a variety of skills and insights that are absent in the weak-sense critical thinker.

As we examine how the various traits of mind are conducive to fair-mindedness, we will also look at the manner in which the traits contribute to quality of thought (in general). In addition to the fairness that strong-sense critical thinking implies, depth of thinking and high quality of thinking are also implied. Weak-sense critical thinkers develop a range of intellectual skills (for example, skills of argumentation) and may achieve some success in getting what they want, but they do not develop any of the traits highlighted in this chapter.

It is important to note that many people considered successful in business or in their profession are, in fact, selfish thinkers. In self-indulgent and materialistic cultures, the idea "if it is good for me it is good for everyone" is tacitly assumed when not overtly stated. The pursuit of money, often at the expense of the rights and needs of others, is considered not only acceptable, but also commendable. Nevertheless when the pursuit of wealth and power is unbridled, injustice often results. The human mind is readily able to justify its own selfishness and lack of consideration for others. The powerful find many reasons to ignore the interests of the weak (Figure 3.2) . Figure 3.2 ).-->

Figure 3.2. These are the opposites of the intellectual virtues. They occur naturally in the mind and can only be countered through culturalization of intellectual virtues.

True critical thinkers, in the strong sense, realize the ease with which the mind can ignore the rights and needs of others. They recognize that to be reasonable and just is not to comply with nature but to defy it. They recognize the difficulty of entering into points of view different from our own. They are willing to do the work that is required to go beyond selfish thinking.

Let us turn to the component traits of the strong-sense critical thinker. After we take up each individual trait as it stands in relation to fair-mindedness, we will highlight its significance as a contributor to the general development of high levels of thinking.

What Does Fair-Mindedness Require?

First, the basic concept:

Fair-mindedness entails a consciousness of the need to treat all viewpoints alike, without reference to one's own feelings or selfish interests, or the feelings or selfish interests of one's friends, company, community, or nation. It implies adherence to intellectual standards (such as accuracy and sound logic), uninfluenced by one's own advantage or the advantage of one's group.

To be fair-minded is to strive to treat every viewpoint relevant to a situation in an unbiased, unprejudiced way. It entails a consciousness of the fact that we, by nature, tend to prejudge the views of others, placing them into "favorable" (agrees with us) and "unfavorable" (disagrees with us) categories. We tend to give less weight to contrary views than to our own. This is especially true when we have selfish reasons for opposing views. For example, the manufacturers of asbestos advocated its use in homes and schools, and made large profits on its use, even though they knew for many years that the product was carcinogenic. They ignored the viewpoint and welfare of the innocent users of their product. If we can ignore the potentially harmful effects of a product we manufacture, we can reap the benefits that come with large profits without experiencing pangs of conscience. Thus, fair-mindedness is especially important when the situation calls on us to consider the point of view of those who welfare is in conflict with our short-term vested interest.

The opposite of fair-mindedness is intellectual self-centeredness. It is demonstrated by the failure of thinkers to treat points of view that differ significantly from their own by the same standards that they treat their own.

Achieving a truly fair-minded state of mind is challenging. It requires us to simultaneously become intellectually humble, intellectually courageous, intellectually empathetic, intellectually honest, intellectually perseverant, confident in reason (as a tool of discovery and learning), and intellectually autonomous.

Without this family of traits in an integrated constellation, there is no true fair-mindedness. But these traits, singly and in combination, are not commonly discussed in everyday life, and are rarely taught. They are not discussed on television. Your friends and colleagues will not ask you questions about them.

In truth, because they are largely unrecognized, these traits are not commonly valued. Yet each of them is essential to fair-mindedness and the development of critical thinking. Let us see how and why this is so.

Intellectual Humility: Having Knowledge of Ignorance

We will begin with the fair-minded trait of intellectual humility:

Intellectual humility may be defined as having a consciousness of the limits of one's knowledge, including a sensitivity to circumstances in which one's native egocentrism is likely to function self-deceptively. This entails being aware of one's biases, one's prejudices, the limitations of one's viewpoint, and the extent of one's ignorance. Intellectual humility depends on recognizing that one should not claim more than one actually knows. It does not imply spinelessness or submissiveness. It implies the lack of intellectual pretentiousness, boastfulness, or conceit, combined with insight into the logical foundations, or lack of such foundations, of one's beliefs.

The opposite of intellectual humility is intellectual arrogance, a lack of consciousness of the limits of one's knowledge, with little or no insight into self-deception or the limitations of one's point of view. Intellectually arrogant people often fall prey to their own bias and prejudice, and frequently claim to know more than they actually know.

When we think of intellectual arrogance, we are not necessarily implying a person who is outwardly smug, haughty, insolent, or pompous. Outwardly, the person may appear humble. For example, a person who uncritically believes in a cult leader may be outwardly self-effacing ("I am nothing. You are everything"), but intellectually he or she is making a sweeping generalization that is not well founded, and has complete faith in that generalization.

Unfortunately, in human life people of the full range of personality types are capable of believing they know what they don't know. Our own false beliefs, misconceptions, prejudices, illusions, myths, propaganda, and ignorance appear to us as the plain, unvarnished truth. What is more, when challenged, we often resist admitting that our thinking is "defective." We then are intellectually arrogant, even though we might feel humble. Rather than recognizing the limits of our knowledge, we ignore and obscure those limits. From such arrogance, much suffering and waste result.

It is not uncommon for the police, for example, to assume a man is guilty of a crime because of his appearance, because he is black for example, or because he wears an earring, or because he has a disheveled and unkempt look about him. Owing to the prejudices driving their thinking, the police are often incapable of intellectual humility. In a similar way, prosecutors have been known to withhold exculpatory evidence against a defendant in order to "prove" their case. Intellectually righteous in their views, they feel confident that the defendant is guilty. Why, therefore, shouldn't they suppress evidence that will help this "guilty" person go free?

Intellectual arrogance is incompatible with fair-mindedness because we cannot judge fairly when we are in a state of ignorance about the object of our judgment. If we are ignorant about a religion (say, Buddhism), we cannot be fair in judging it. And if we have misconceptions, prejudices, or illusions about it, we will distort it (unfairly) in our judgment. We will misrepresent it and make it appear to be other than it is. Our false knowledge, misconceptions, prejudices, and illusions stand in the way of the possibility of our being fair. Or if we are intellectually arrogant, we will be inclined to judge too quickly and be overly confident in our judgment. Clearly, these tendencies are incompatible with being fair (to that which we are judging).

Why is intellectual humility essential to higher-level thinking? In addition to helping us become fair-minded thinkers, knowledge of our ignorance can improve our thinking in a variety of ways. It can enable us to recognize the prejudices, false beliefs, and habits of mind that lead to flawed learning. Consider, for example, our tendency to accept superficial learning. Much human learning is superficial. We learn a little and think we know a lot. We get limited information and generalize hastily from it. We confuse cutesy phrases with deep insights. We uncritically accept much that we hear and read - especially when what we hear or read agrees with our intensely held beliefs or the beliefs of groups to which we belong.

The discussion in the chapters that follow encourages intellectual humility and will help to raise your awareness of intellectual arrogance. See if you, from this moment, can begin to develop in yourself a growing awareness of the limitations of your knowledge and an increasing sensitivity to instances of your inadvertent intellectual arrogance. When you do, celebrate that sensitivity. Reward yourself for finding weaknesses in your thinking. Consider recognition of weakness an important strength, not a weakness. As a starter, answer the following questions:

Can you construct a list of your most significant prejudices? (Think of what you believe about your country, your religion, your company, your friends, your family, simply because others - colleagues, parents, friends, peer group, media - conveyed these to you.)

Do you ever argue for or against views when you have little evidence upon which to base your judgment?

Do you ever assume that your group (your company, your family, your religion, your nation, your friends) is correct (when it is in conflict with others) even though you have not looked at the situation from the point of view of the others with which you disagree?

Intellectual Courage: Being Willing to Challenge Beliefs

Now let's consider intellectual courage:

Intellectual courage may be defined as having a consciousness of the need to face and fairly address ideas, beliefs, or viewpoints toward which one has strong negative emotions and to which one has not given a serious hearing. Intellectual courage is connected to the recognition that ideas that society considers dangerous or absurd are sometimes rationally justified (in whole or in part). Conclusions and beliefs inculcated in people are sometimes false or misleading. To determine for oneself what makes sense, one must not passively and uncritically accept what one has learned. Intellectual courage comes into play here because there is some truth in some ideas considered dangerous and absurd, and distortion or falsity in some ideas strongly held by social groups to which we belong. People need courage to be fair-minded thinkers in these circumstances. The penalties for nonconformity can be severe.

The opposite of intellectual courage, intellectual cowardice, is the fear of ideas that do not conform to one's own. If we lack intellectual courage, we are afraid of giving serious consideration to ideas, beliefs, or viewpoints that we perceive as dangerous. We feel personally threatened by some ideas when they conflict significantly with our personal identity - when we feel that an attack on the ideas is an attack on us as a person.

All of the following ideas are "sacred" in the minds of some people: being a conservative, being a liberal; believing in God, disbelieving in God; believing in capitalism, believing in socialism; believing in abortion, disbelieving in abortion; believing in capital punishment, disbelieving in capital punishment. No matter what side we are on, we often say of ourselves: "I am a (an) [insert sacred belief here; for example, I am a Christian. I am a conservative. I am a socialist. I am an atheist]."

Once we define who we are in relation to an emotional commitment to a belief, we are likely to experience inner fear when that idea or belief is questioned. Questioning the belief seems to be questioning us. The intensely personal fear that we feel operates as a barrier in our minds to being fair (to the opposing belief). When we do seem to consider the opposing idea, we subconsciously undermine it, presenting it in its weakest form, in order to reject it. This is one form of intellectual cowardice. Sometimes, then, we need intellectual courage to overcome our self-created inner fear - the fear we ourselves have created by linking our identity to a specific set of beliefs.

Intellectual courage is just as important in our professional as in our personal lives. If, for example, we are unable to analyze the work-related beliefs we hold, then we are essentially trapped by those beliefs. We do not have the courage to question what we have always taken for granted. We are unable to question the beliefs collectively held by our co-workers. We are unable to question, for example, the ethics of our decisions and our behavior at work. But fair-minded managers, employers, and employees do not hesitate to question what has always been considered "sacred" or what is taken for granted by others in their group. It is not uncommon, for example, for employees to think within a sort of "mob mentality" against management, which often includes routinely gossiping to one another about management practices, especially those practices that impact them. Those with intellectual courage, rather than participating in such gossip in a mindless way, will begin to question the source of the gossip. They will question whether there is good reason for the group to be disgruntled, or whether the group is irrational in its expectations of management.

Another important reason to acquire intellectual courage is to overcome the fear of rejection by others because they hold certain beliefs and are likely to reject us if we challenge those beliefs. This is where we invest the group with the power to intimidate us, and such power is destructive. Many people live their lives in the eyes of others and cannot approve of themselves unless others approve of them. Fear of rejection is often lurking in the back of their minds. Few people challenge the ideologies or belief systems of the groups to which they belong. This is the second form of intellectual cowardice. Both make it impossible to be fair to the ideas that are contrary to our, or our group's, identity.

You might note in passing an alternative way to form your personal identity. This is not in terms of the content of any given idea (what you actually believe) but, instead, in terms of the process by which you came to it. This is what it means to take on the identity of a critical thinker. Consider the following resolution:

I will not identify with the content of any belief. I will identify only with the way I come to my beliefs. I am a critical thinker and, as such, am ready to abandon any belief that cannot be supported by evidence and rational considerations. I am ready to follow evidence and reason wherever they lead. My true identity is that of being a critical thinker, a lifelong learner, and a person always looking to improve my thinking by becoming more reasonable in my beliefs.

With such an identity, intellectual courage becomes more meaningful to us, and fair-mindedness more essential. We are no longer afraid to consider beliefs that are contrary to our present beliefs. We are not afraid of being proven wrong. We freely admit to having made mistakes in the past. We are happy to correct any mistakes we are still making: Tell me what you believe and why you believe it, and maybe I can learn from your thinking. I have cast off many early beliefs. I am ready to abandon as many of the present beliefs as are not consistent with the way things are.

Intellectual Empathy: Entertaining Opposing Views

Next let's consider intellectual empathy, another trait of mind necessary to fair-mindedness:

Intellectual empathy is an awareness of the need to imaginatively put oneself in the place of others so as to genuinely understand them. To have intellectual empathy is to be able to accurately reconstruct the viewpoints and reasoning of others and to reason from premises, assumptions, and ideas other than one's own. This trait also correlates with the willingness to remember occasions when one was wrong in the past despite an intense conviction of being right, and with the ability to imagine being similarly deceived in a case at hand.

The opposite of intellectual empathy is intellectual self-centeredness. It is thinking centered on self. When we think from a self-centered perspective, we are unable to understand others' thoughts, feelings, and emotions. From this natural perspective, we are the recipients of most of our attention. Our pain, our desires, and our hopes are most pressing. The needs of others pale into insignificance before the domination of our own needs and desires. We are unable to consider issues, problems, and questions from a viewpoint that differs from our own and that, when considered, would force us to change our perspective.

How can we be fair to the thinking of others if we have not learned to put ourselves in their intellectual shoes? Fair-minded judgment requires a good-faith effort to acquire accurate knowledge. Human thinking emerges from the conditions of human life, from very different contexts and situations. If we do not learn how to take on the perspectives of others and to accurately think as they think, we will not be able to fairly judge their ideas and beliefs. Actually trying to think within the viewpoint of others is not easy, though. It is one of the most difficult skills to acquire.The extent to which you have intellectual empathy has direct implications for the quality of your life. If you cannot think within the viewpoint of your supervisor, for example, you will have difficulty functioning successfully in your job and you may often feel frustrated. If you cannot think within the viewpoints of your subordinates, you will have difficulty understanding why they behave as they do. If you cannot think within the viewpoint of your spouse, the quality of your marriage will be adversely affected. If you cannot think within the viewpoints of your children, they will feel misunderstood and alienated from you.

Intellectual Integrity: Holding Ourselves to the Same Standards to Which We Hold Others

Let us now consider intellectual integrity:

Intellectual integrity is defined as recognition of the need to be true to one's own thinking and to hold oneself to the same standards one expects others to meet. It means to hold oneself to the same rigorous standards of evidence and proof to which one holds one's antagonists - to practice what one advocates for others. It also means to honestly admit discrepancies and inconsistencies in one's own thought and action, and to be able to identify inconsistencies in one's own thinking.

The opposite of intellectual integrity is intellectual hypocrisy, a state of mind unconcerned with genuine integrity. It is often marked by deep-seated contradictions and inconsistencies. The appearance of integrity means a lot because it affects our image with others. Therefore, hypocrisy is often implicit in the thinking and action behind human behavior as a function of natural egocentric thinking. Our hypocrisy is hidden from us. Though we expect others to adhere to standards to which we refuse to adhere, we see ourselves as fair. Though we profess certain beliefs, we often fail to behave in accordance with those beliefs.

To the extent that we have intellectual integrity, our beliefs and actions are consistent. We practice what we preach, so to speak. We don't say one thing and do another.

Suppose I were to say to you that our relationship is really important to me, but you find out that I have lied to you about something important to you. My behavior lacks integrity. I have acted hypocritically.

Clearly, we cannot be fair to others if we are justified in thinking and acting in contradictory ways. Hypocrisy by its very nature is a form of injustice. In addition, if we are not sensitive to contradictions and inconsistencies in our own thinking and behavior, we cannot think well about ethical questions involving ourselves.

Consider this political example. From time to time the U.S. media discloses highly questionable practices by the CIA. These practices run anywhere from documentation of attempted assassinations of foreign political leaders (say, attempts to assassinate President Castro of Cuba) to the practice of teaching police or military representatives in other countries (say, Central America or South America) how to torture prisoners to get them to disclose information about their associates. To appreciate how such disclosures reveal a lack of intellectual integrity, we only have to imagine how the U.S. government and citizenry would respond if another nation were to attempt to assassinate the president of the U.S or trained U.S. police or military in methods of torture. Once we imagine this, we recognize a basic inconsistency common in human behavior and a lack of intellectual integrity on the part of those who plan, engage in, or approve of, such activities.

All humans sometimes fail to act with intellectual integrity. When we do, we reveal a lack of fair-mindedness on our part, and a failure to think well enough as to grasp the internal contradictions in our thought or life.

Intellectual Perseverance: Working Through Complexity and Frustration

Let us now consider intellectual perseverance:

Intellectual perseverance can be defined as the disposition to work one's way through intellectual complexities despite the frustration inherent in the task. Some intellectual problems are complex and cannot be easily solved. One has intellectual perseverance when one does not give up in the face of intellectual complexity or frustration. The intellectually perseverant person displays firm adherence to rational principles despite the irrational opposition of others, and has a realistic sense of the need to struggle with confusion and unsettled questions over an extended time to achieve understanding or insight.

The opposite of intellectual perseverance is intellectual laziness, demonstrated in the tendency to give up quickly when faced with an intellectually challenging task. The intellectually indolent, or lazy, person has a low tolerance for intellectual pain or frustration.

How does a lack of intellectual perseverance impede fair-mindedness? Understanding the views of others requires that we do the intellectual work to achieve that understanding. That takes intellectual perseverance-insofar as those views are very different from ours or are complex in nature. For example, suppose you are a Christian wanting to be fair to the views of an atheist. Unless you read and understand the reasoning of intelligent and insightful atheists, you are not being fair to those views. Some intelligent and insightful atheists have written books to explain how and why they think as they do. Some of their reasoning is complicated or deals with issues of some complexity. It follows that only those Christians who have the intellectual perseverance to read and/or understand atheists can be fair to atheist views. Of course, a parallel case could be developed with respect to atheists' understanding the views of intelligent and insightful Christians.

Finally, it should be clear how intellectual perseverance is essential to all areas of higher-level thinking. Virtually all higher-level thinking requires some intellectual perseverance to overcome. It takes intellectual perseverance to reason well through complex questions on the job, to work through complex problems in intimate relationships, to solve problems in parenting. Many give up during early stages of working through a problem. Lacking intellectual perseverance, they cut themselves off from all the insights that thinking through an issue at a deep level provides. They avoid intellectual frustration, no doubt, but they end up with the everyday frustrations of not being able to solve complex problems.

Confidence in Reason: Recognizing that Good Reasoning Has Proven Its Worth

Let us now consider the trait of confidence in reason:

Confidence in reason is based on the belief that one's own higher interests and those of humankind will be best served by giving the freest play to reason. Reason encourages people to come to their own conclusions by developing their own rational faculties. It is the faith that, with proper encouragement and cultivation, people can learn to think for themselves. As such, they can form insightful viewpoints, draw reasonable conclusions, and develop clear, accurate, relevant, and logical thought processes., In turn, they can persuade each other by appealing to good reason and sound evidence, and become reasonable persons, despite the deep-seated obstacles in human nature and social life. When one has confidence in reason, one is "moved" by reason in appropriate ways. The very idea of reasonability becomes one of the most important values and a focal point in one's life. In short, to have confidence in reason is to use good reasoning as the fundamental criterion by which to judge whether to accept or reject any belief or position.

The opposite of confidence in reason is intellectual distrust of reason, given by the threat that reasoning and rational analysis pose to the undisciplined thinker. Being prone toward emotional reactions that validate present thinking, egocentric thinkers often express little confidence in reason. They do not understand what it means to have faith in reason. Instead, they have confidence in the truth of their own belief systems, however flawed their beliefs might be.