Articles on Special education

Displaying 1 - 20 of 40 articles.

Navigating special education labels is complex, and it matters for education equity

Laura Perez Gonzalez , Toronto Metropolitan University ; Henry Parada , Toronto Metropolitan University , and Veronica Escobar Olivo , Toronto Metropolitan University

Schools have a long way to go to offer equitable learning opportunities, especially in French immersion

Diana Burchell , University of Toronto ; Becky Xi Chen , University of Toronto ; Elizabeth Kay-Raining Bird , Dalhousie University , and Roksana Dobrin-De Grace , Toronto Metropolitan University

Daily report cards can decrease disruptions for children with ADHD

Gregory Fabiano , Florida International University

Achieving full inclusion in schools: Lessons from New Brunswick

Melissa Dockrill Garrett , University of New Brunswick and Andrea Garner , University of New Brunswick

Pandemic shut down many special education services – how parents can help their kids catch up

Mitchell Yell , University of South Carolina

Police response to 5-year -old boy who left school was problematic from the start

Elizabeth K. Anthony , Arizona State University

Decades after special education law and key ruling, updates still languish

Charles J. Russo , University of Dayton

ADHD: Medication alone doesn’t improve classroom learning for children – new research

William E. Pelham Jr. , Florida International University

Students of color in special education are less likely to get the help they need – here are 3 ways teachers can do better

Mildred Boveda , Penn State

Students with disabilities are not getting help to address lost opportunities

John McKenna , UMass Lowell

5 tips to help preschoolers with special needs during the pandemic

Michele L. Stites , University of Maryland, Baltimore County and Susan Sonnenschein , University of Maryland, Baltimore County

Children on individual education plans: What parents need to know, and 4 questions they should ask

Tori Trajanovski , York University, Canada

3 ways music educators can help students with autism develop their emotions

Dawn R. Mitchell White , University of South Florida

‘Generation C’: Why investing in early childhood is critical after COVID-19

David Philpott , Memorial University of Newfoundland

Federal spending covers only 8% of public school budgets

David S. Knight , University of Washington

Coronavirus: Distance learning poses challenges for some families of children with disabilities

Jess Whitley , L’Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa

How lockdown could affect South Africa’s children with special needs

Athena Pedro , University of the Western Cape ; Dr Bronwyn Mthimunye , University of the Western Cape , and Ella Bust , University of the Western Cape

5 tips to help parents navigate the unique needs of children with autism learning from home

Amanda Webster , University of Wollongong

Ontario’s high school e-learning still hasn’t addressed students with special needs

Pam Millett , York University, Canada

Excluded and refused enrolment: report shows illegal practices against students with disabilities in Australian schools

Kathy Cologon , Macquarie University

Related Topics

- Children with disability

- Inclusive education

- Special education services

- Special needs

Top contributors

Associate Professor, Tarleton State University

Professor of participation and learning support, The Open University

Senior Lecturer, Department of Educational Studies, Macquarie University

Senior Research Fellow, University of Warwick

Associate Professor of Economics, Carleton University

Assistant Professor of Special Education, Boston University

Assistant Professor of Special Education, UMass Boston

Assistant Professor of Economics, The University of Texas at Austin

Assistant Professor of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies, University of Memphis

Assistant Professor, Nazarbayev University

Professor of Educational Psychology and Special Educational Needs, University of Exeter

PhD Researcher, Swansea University

Associate Professor of Education, Elon University

Associate Professor, Faculty of Law, University of Technology Sydney

- X (Twitter)

- Unfollow topic Follow topic

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Students with disabilities have a right to qualified teachers — but there's a shortage

Lee V. Gaines

This is the first in a two-part series on the special education teacher shortage. You can read part two here .

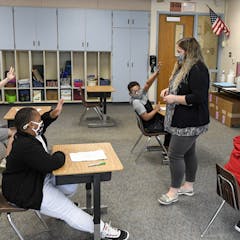

At the beginning of the school year, when Becky Ashcraft attended an open house at her 12-year-old daughter's school, she was surprised to find there was no teacher in her daughter's classroom – just a teacher's aide.

"They're like, 'Oh, well, she doesn't have a teacher right now. But, you know, hopefully, we'll get one soon,' " Ashcraft recalls.

Schools are struggling to hire special education teachers. Hawaii may have found a fix

Ashcraft's daughter attends a public school in northwest Indiana that exclusively serves students with disabilities. She is on the autism spectrum and doesn't speak. Without an assigned teacher, it was difficult for Ashcraft to know what her daughter did everyday.

"I wonder what actually kind of education she was receiving," Ashcraft says.

Ashcraft's daughter spent the entire fall semester without an assigned teacher. One other parent at the school told NPR they were in the same position. Ashcraft says the principal told her they were trying to hire someone, but it was difficult to find qualified candidates.

After Months Of Special Education Turmoil, Families Say Schools Owe Them

The school would not confirm to NPR that Ashcraft's daughter had no teacher, but a spokesperson did say the school has used substitutes to provide special education services amid the shortage of qualified educators.

The federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act guarantees students with disabilities access to fully licensed special educators. But as Ashcraft learned, those teachers can be hard to find. In 2019, 44 states reported special education teacher shortages to the federal government. This school year, that number jumped to 48.

When schools can't find qualified teachers, federal law allows them to hire people who aren't fully qualified so long as they're actively pursuing their special education certification. Indiana, California, Virginia and Maryland are among the states that offer provisional licenses to help staff special education classrooms.

It's a practice that concerns some special education experts. They worry placing people who aren't fully trained for the job in charge of classrooms could harm some of the most vulnerable students.

But given the lack of qualified special education teachers, Ashcraft says she wouldn't mind if her daughter's teacher wasn't fully trained yet.

"Let them work towards that [license], that's wonderful," she says. "But, you know, I guess at this point, you know, we're happy to take anybody."

The case against provisional special education licenses

Jacqueline Rodriguez, with the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education, is alarmed at the number of provisional licenses issued to unqualified special education teachers in recent years — even if those teachers are actively working toward full licensure.

"The band aid has been, let's put somebody who's breathing in front of kids, and hope that everybody survives," she says. Her organization focuses on teacher preparation, and has partnered with higher education institutions to improve recruitment of special educators.

She worries placing untrained people at the helm of a classroom, and in charge of Individualized Education Programs, is harmful for students.

"This to me is like telling somebody there's a dearth of doctors in neurosurgery, so we would love for you to transition into the field by giving you the opportunity to operate on people while you're taking coursework at night," Rodriguez says.

She admits it's a provocative analogy, but says teaching is a profession that requires intensive coursework, evaluation and practice. "And unless you can demonstrate competency, you have no business being a teacher."

One district is building a special education teacher pipeline

Shaleta West had zero teaching experience when she was hired as a special educator by Elkhart Community Schools, a district in northern Indiana.

She says her first couple weeks in the classroom were overwhelming.

"It was very scary because, you know, I know kids, yes. But when you're trying to teach kids it's a whole other ball game. You can't just play around with them and talk to them and chit chat. You have to teach."

The Coronavirus Crisis

Families of children with special needs are suing in several states. here's why..

Her district is helping her work toward her certification at nearby Indiana University South Bend. Elkhart Community Schools pays West's tuition and, in exchange, West has agreed to work for the district for five years.

The district also provides West with a mentor — a seasoned special educator who answers questions, offers tips and looks over the complicated paperwork that's legally required for students with disabilities.

West says she would have been lost without the mentorship and the university classes.

"To be honest, I don't even know if I would have stayed," she explains.

"I knew nothing. I came in without any prior knowledge to what I needed to do on a daily basis."

Administrator Lindsey Brander oversees the Elkhart schools program that supports West. She says the program has produced about 30 fully qualified special educators over the past four years. This year, it's serving about 10 special educators, all on provisional licenses.

"We are able to recruit our own teachers and train them specifically for our students. So the system is working," Brander explains. The challenge, she says, is that it's become increasingly difficult for the district to find people to participate in the program.

And even with a new teacher pipeline in place, the district still has 24 special education vacancies.

Brander would prefer if all the district's special education teachers were fully qualified the first day they set foot in a classroom.

"But that's not reality. That's not going to happen. Until we fix some of the structural challenges that we have in education, this is how business is done now. This is life in education," she says.

How high teacher turnover impacts students

The structural issues contributing to the special educator shortage include heavy workloads and relatively low pay. At Elkhart schools, for example, new special education teachers with bachelor's degrees receive a minimum salary of $41,000, according to district officials.

Desiree Carver-Thomas, a researcher with the Learning Policy Institute, says low compensation and long workdays can lead to high turnover, especially in schools that serve students of color and children from low-income households. And when special education teachers leave the profession, the cycle continues.

"Because when turnover rates are so high, schools and districts they're just trying to fill those positions with whomever they can find, often teachers who are not fully prepared," Carver-Thomas says.

Hiring unprepared teachers can also contribute to high turnover rates, according to Carver-Thomas' research . And it can impact student outcomes.

Schools Say They Have To Do Better For Students With Disabilities This Fall

As NPR has reported , Black students and students with disabilities are disciplined and referred to law enforcement at higher rates than students without disabilities. Black students with disabilities are especially vulnerable; federal data shows they have the highest risk for suspension among all students with disabilities.

"That may be more common when teachers don't have the tools and the experience and the training to respond appropriately," Carver-Thomas says.

Schools and families have to make do

The solution to the special educator shortage isn't simple. Carver-Thomas says it will require schools, colleges and governments to work together to boost teacher salaries and improve recruitment, preparation, working conditions and on-the-job support.

In the meantime, schools and families will have to make do.

In January, Becky Ashcraft learned her northwest Indiana school had found a teacher for her daughter's classroom.

She says she's grateful to finally have a fully licensed teacher to tell her about her daughter's school day. And she wishes the special educators that families like hers rely on were valued more.

"We've got to be thankful for the people that do this work," she says.

Nicole Cohen edited this story for broadcast and for the web.

Plagued by delays and errors, California’s colleges navigate FAFSA fiasco

How Fresno Unified is getting missing students back in class

How can we get more Black teachers in the classroom?

Patrick Acuña’s journey from prison to UC Irvine | Video

Family reunited after four years separated by Trump-era immigration policy

School choice advocate, CTA opponent Lance Christensen would be a very different state superintendent

Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

Is dual admission a solution to California’s broken transfer system?

April 24, 2024

March 21, 2024

Raising the curtain on Prop 28: Can arts education help transform California schools?

February 27, 2024

Keeping options open: Why most students aren’t eligible to apply to California’s public universities

Teacher Voices

Now is the time for schools to invest in special-education inclusion models that benefit all students

Kimberly Berry

November 10, 2021.

Ivan was a fourth grader with big brown eyes, a wide smile and a quiet demeanor who refused to enter my classroom. “Everyone thinks I’m stupid,” he’d say. I’ve changed his name to protect his privacy.

At the time, my school employed a pull-out model for students with disabilities, meaning they were removed from their assigned classrooms to receive specialized services and supports. This left Ivan feeling embarrassed, ostracized and resistant to putting forth academic effort.

One in 8 students in U.S. public schools have an individualized education plan, or IEP, making them eligible for special education services. About 750,000 students with disabilities attend California public schools. Many, like Ivan, do not respond well to being substantially separated from their peers. Research suggests that inclusion models designed to integrate students with and without disabilities into a single learning environment can lead to stronger academic and social outcomes.

At Caliber ChangeMakers Academy — where I have been a program specialist for five of the 10 years I have worked with students with disabilities — we knew an inclusion model was best for Ivan and many others. Yet, we didn’t think we had the tools or resources to make it possible.

We were wrong.

Schools can support students like Ivan — and those of all abilities — to learn from and alongside one another in an inclusive setting without exorbitant costs if they rethink how they allocate resources and develop educators’ confidence and competence in teaching all students in a general education setting.

In 2019, we began intentionally organizing staff, time and money toward inclusion, and we did so without spending more than similar public schools do that don’t focus on inclusion.

Now, with the infusion of federal Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief funding, schools have additional resources to invest in this approach now, in service to longer-term, sustainable change.

The nonprofit Education Resource Strategies studied our school and three others in California that are doing this work without larger investments of resources. Their analysis examines the resource shifts that inclusion-focused schools employ and can be tapped by other schools considering this work, taking a “do now, build toward” approach that addresses student needs and sustains these changes even after the emergency federal funding expires. Many of their recommendations mirror the steps we took to pursue an inclusion model.

It didn’t happen overnight, but three steps were important to our efforts to adopt a more inclusive model for teaching and learning:

- Shift special education staff into general education classrooms to support targeted group sizes. At Caliber ChangeMakers Academy, special education teachers are departmentalized, each serving as a co-teacher to two general education teachers, leveraging their content expertise to share responsibility for classroom instruction. That means some special education teachers now teach students who are not part of their caseload. That means they are tracking the goals of more students, which also means that young people have more specialty educators working together to support their individual needs.

- Prioritize connected professional learning around inclusion for all teachers . We adjusted teachers’ schedules to incorporate collaborative time for general education and special education teachers to meet before, during and after lessons to plan engaging, differentiated instruction for all. On the surface, the reduction in individual planning time might be a challenge. However, our teachers have found that they now feel more prepared, effective and connected because they have a partner to turn to for feedback, suggestions and encouragement.

- Invest in social-emotional and mental health staff to narrow the scope of special education teachers. These staff members work to reduce unnecessary special education referrals and mitigate troubles facing students regardless of their disability status. They also can help address unexpected challenges, meaning special education teachers can spend more time in general education classrooms. A tradeoff we made is to slightly increase class sizes with fewer general administrative and support staff to prioritize hiring experienced social-emotional learning and mental health professionals.

For schools eager to adopt a more inclusive instructional model, now is the time. The emergency federal funding creates unprecedented opportunities for school and system leaders to build research-backed, sustainable inclusion models that can better meet the needs of all students, including students with disabilities.

I’ve seen firsthand that inclusive, diverse classrooms can provide powerful learning opportunities for all students.

As for Ivan, he’s now in eighth grade and thriving in an inclusive, co-teaching classroom. He went from completing almost no academic work independently to completing science lab reports on his own, working in collaborative groups in his English class and declaring that he loves math. Because our school invested in and normalized differentiated supports in an inclusive setting, now Ivan and many other students are getting what they need to be successful academically, socially and emotionally.

Kimberly Berry is a special education program specialist at Caliber ChangeMakers Academy in Vallejo.

The opinions in this commentary are those of the author. If you would like to submit a commentary, please review our guidelines and contact us .

To get more reports like this one, click here to sign up for EdSource’s no-cost daily email on latest developments in education.

Share Article

Comments (3)

Leave a comment, your email address will not be published. required fields are marked * *.

Click here to cancel reply.

XHTML: You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy .

Karina Villalona 2 years ago 2 years ago

I speak as a mom of two kids in co-teaching collaborative classes for their 4 main academic subjects, as well as a former teacher, and a school psychologist for 19 years. I agree with much of what Ms. Berry states. Co-teaching programs can be very successful for both general and special education students if all of the appropriate supports are in place (as listed by Ms. Berry). However, it is important to clarify that this … Read More

I speak as a mom of two kids in co-teaching collaborative classes for their 4 main academic subjects, as well as a former teacher, and a school psychologist for 19 years. I agree with much of what Ms. Berry states. Co-teaching programs can be very successful for both general and special education students if all of the appropriate supports are in place (as listed by Ms. Berry).

However, it is important to clarify that this model is not a panacea. Students with cognitive skills that are far below the average range have also shared how incredibly frustrating being in co-teaching classes can be for them. Even with support from the special education teacher, the pacing for some students is way too fast. In addition, depending on what the student’s specific classification is, co-teaching on its own does not allow an opportunity for remedial instruction.

My daughters are dyslexic. They participate in co-teaching with a lot of support from the special education teacher. They have one period of direct instruction in reading via an Orton-Gillingham based program and one period of Resource Room daily which allows them to work on content from the general education classes that they might need to review, break down or preview.

So, yes, co-teaching can be great for some students when the program is well managed and staffed; however, we cannot ignore the need for small group supports and remedial instruction when necessary.

Craig 2 years ago 2 years ago

Studies cited showing benefits of inclusion model typically suffer from selection bias, and there are no significant data on the effects of inclusion models on neurotypical peers. Does the author of this piece have data showing results that support her claims? Also, what do the teachers in this program have to say about it, in the first person? If this is truly working as presented it will be a game changer.

Monica Saraiya 2 years ago 2 years ago

The inclusion model is not a one size fits all one. Students with significant learning differences do not receive the services that best meet their needs in this model. As with all practices in education, inclusion must be one, but not the only way to service students who need specialized help with their learning.

EdSource Special Reports

Grassroots contributions fueled bid to oust two from Orange County school board

A grassroots campaign recalled two conservative members of the Orange Unified School District in an election that cost more than half a million dollars.

California moves a step closer to eliminating one of the state’s last teacher assessments

Legislation that would remove one of the last tests teachers are required to take to earn a credential in California passed the Senate Education Committee.

Community college faculty should all be allowed to work full time

Part-time instructors, many who work for decades off the tenure track and at a lower pay rate, have been called “apprentices to nowhere.”

Bill to mandate ‘science of reading’ in California classrooms dies

A bill to mandate use of the method will not advance in the Legislature this year in the face of teachers union opposition.

EdSource in your inbox!

Stay ahead of the latest developments on education in California and nationally from early childhood to college and beyond. Sign up for EdSource’s no-cost daily email.

Stay informed with our daily newsletter

Special Ed Shouldn’t Be Separate

Isolating kids from their peers is unjust.

In the fall of 2020, as my son and his neighborhood friends started to trickle back out into the world, my daughter, Izzy, stayed home. At the time, Izzy was 3 years old, ripe for the natural learning that comes from being with other kids. I knew by the way she hummed and flapped her hands around children at the playground—and by her frustration with me at home—that she yearned to be among them.

The question of where Izzy would attend school had been vexing me for two years. Izzy had been a happy infant, but she was small for her age and missed every developmental milestone. When she was eight months old, my husband and I learned that she had been born with a rare genetic disorder and would grow up with a range of intellectual and physical disabilities. Doctors were wary of giving us a prognosis; the families I found on Facebook who had children with similar disorders offered more definitive—and doomful—forecasts. When Izzy showed signs of some common manifestations (low muscle tone, lack of verbal communication, feeding troubles) but no signs of others (vision and hearing loss, seizures), I started to lose confidence in other people’s predictions—and to instead look to Izzy as the determinant of her own abilities.

While managing Izzy’s medical care and her therapy regimen, I also started the process of finding her a school in Oakland, California, where we lived at the time. I knew what options weren’t available to her, such as the small family-run preschool in a cozy Craftsman home that my son had attended. Private schools in general have fewer obligations to accommodate students with disabilities—they don’t directly receive government funding and aren’t covered by the federal special-education law that requires the provision of free and appropriate public education. California’s public preschools, at the time reserved largely for low-income families, weren’t an option, either, because our family exceeded the income threshold to qualify.

Read: Grieving the future I imagined for my daughter

Although kids with disabilities are spending more and more time in general classrooms, in the United States, “special” education still often means “separate.” Kids with disabilities rarely receive the same education as their peers without disabilities; commonly—or mostly, in the case of those with intellectual disabilities—they are cordoned off in separate classrooms. The one special-education preschool in Oakland I found that could accommodate Izzy would have sorted her into a siloed classroom for students with heavy support needs. The prospect of her being hidden away from other kids seemed unappealing to me—and unjust. As desperate as I was for Izzy to attend school, I didn’t want that to mean removing her at an early age from the rest of society.

Another approach—placing students with disabilities, with the support they need, into general-education classrooms—is known as inclusive education. If the goal of education is to prepare students for the real world, an inclusive approach makes a lot more sense. “Students educated in segregated settings graduate to inhabit the same society as students without disability,” writes Kate de Bruin, a senior lecturer at Monash University’s School of Curriculum, Teaching and Inclusive Education. “There is no ‘special’ universe into which they graduate.”

In her role training teachers, de Bruin promotes tiered intervention systems where all students are given a base layer of general support, and additional services (small groups, more time, more detailed or focused instruction) are added on for students who require them. (For example, when doing counting activities, my daughter’s teachers and therapists often pair her with another child and incorporate her favorite toys.) Depending on the situation, a specialist might “push in” to the general classroom, sitting alongside a student at her desk to work one-on-one or they might “pull out” and remove the student from the classroom to find a quieter separate space.

There’s a concept in disability studies called “the dilemma of difference.” The legal scholar Martha Minow coined the term in 1985, and discussed it in her book Making All the Difference: Inclusion, Exclusion, and American Law . The issue of whether students with disabilities should be treated as “different” or “the same” underlies many of the mechanics of special education. In both of my kids’ schools, specialists also build relationships with students without disabilities and include them in activities as a way to normalize disability and the basic human need for help. Thoughtful inclusion reinforces a paradox of the human condition: We are all different and the same.

Read: Is the bar too low for special education?

“Inclusion is quality teaching for all kids, designed to make sure that everybody gets access to quality instruction—and then for some kids, it’s intensified,” de Bruin told me.

In 2019, de Bruin published an analysis of 40 years of research on the benefits of inclusive education. She cites more than three dozen studies showing positive outcomes when students with disabilities are included in a classroom setting designed for all children, rather than siloed off for “special” instruction. In an inclusive model, she writes, students with disabilities achieve higher test scores and grade point averages, stronger math and literacy skills, and more developed communication and social skills. Some studies suggest that Individualized Education Programs, road maps for the schooling of students with disabilities, tend to be more ambitious and academically focused in inclusive settings; separate “special” schools (or siloed classrooms within schools) can sometimes resort to a focus on “life skills” instead of curriculum-based goals. Research has indicated that for students with disabilities, an inclusive education can have positive long-term effects on almost every aspect of their lives, including their likelihood of enrolling in college and graduating, finding employment, and forming long-term relationships.

A newer meta-analysis found mixed outcomes for inclusive education. The study doesn’t specify which types of disabilities are better served by inclusion or separate education; it merely states that some children “may benefit from traditional special education in a segregated setting” and that more tailored research is needed. If nothing else, the study’s inconclusive findings serve as a reminder that in my role as Izzy’s parent and advocate, some of the most important decisions I’ll make will rest not on data alone, but also on personal and moral judgments.

We know that failing to include students with their peers when they are young can leave them with deep and lasting psychological scars. In her memoir, Easy Beauty , the author Chloé Cooper Jones reckons with the emotional armor she built up over a lifetime of being excluded due to her physical disability, a congenital sacral disorder. “I’d believed completely that it was my nature to exist at a distance, to be essentially, at my core, alone,” she writes. “My body was constantly seen, but this thing I called my ‘self’ was invisible … People make spaces I cannot enter, teaching me how forgotten I am, how excluded I am from ‘real life.’”

Assessing how many U.S. schools are inclusive of students with disabilities is challenging. Sending students with disabilities to the same schools as their peers without disabilities is not the same as inclusion, which is an added layer of services within those general-education schools that allows students with disabilities to attend the same classes. Integrated schools, at least, have become very common—the U.S. Department of Education reported that, in 2020, 95 percent of students with disabilities attended regular schools. That’s considerable progress given that 50 years ago, before Congress codified their right to an education, only one in five children with disabilities attended school, according to the Department of Education; many lived full-time in residential facilities that resembled hospitals and prisons. In one well-known example , children with disabilities were warehoused in a “school” complex notorious for filthy conditions and rampant abuse.

Changes to federal legislation propelled this shift. In 1975, a law now known as the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) made it more difficult for school districts to separate students with disabilities from their peers, which led to a massive increase in the proportion of students with disabilities attending regular schools.

But a federal law like IDEA doesn’t reach into individual classrooms. In 2020, only 66 percent of students with disabilities spent 80 percent or more of their time in general classes; 30 percent spent significant time in segregated classrooms. Inclusion rates plummet for students with intellectual disabilities, just 19 percent of whom spent 80 percent or more of their day in general classes. In 2020, students with disabilities were more than twice as likely as their peers without disabilities to drop out of high school. The lack of a high-school diploma layers on an additional disadvantage: The national employment rate for people with disabilities hovers around 20 percent.

In fairness, inclusive models require resources that not all schools have access to. An inclusive program that provides individual and small-group support for students with disabilities will require more funding to pay a larger staff—a problem, given that well-trained teachers and specialists are becoming harder to find. Since 2010, nationwide enrollment in teacher-preparation programs has decreased by 36 percent , with a handful of states facing declines of 50 percent or more. Laurie VanderPloeg, the former director of the Office of Special Education Programs at the U.S. Department of Education, told me that the pandemic hit special-education teachers and their students especially hard, given the challenges of remote learning. “We have high demand; we simply don’t have a good supply of teachers to develop the effective workforce we need,” VanderPloeg explained, referring to a recent study estimating that at least 163,000 underqualified teachers—long-term substitutes and others without appropriate training—are teaching in U.S. schools.

VanderPloeg believes the shortage could be reduced by de-specializing teacher training. In her vision, all teachers, not just special-education teachers, are equipped with techniques to handle a much wider range of abilities. “What we’ve done in the past is focus on specific disability needs, instead of the teaching practices,” VanderPloeg said. “All teachers need to be trained to address all needs. That’s good teaching.”

Whether due to the teacher shortage or other factors such as dwindling school funding , it’s clear that many families don’t feel that their children with disabilities are getting an appropriate education. During the 2020–21 school year, families in the U.S. filed more than 20,000 IDEA-related complaints against schools, less than half of which were resolved without a legal hearing. In California, the state with the most people (and students), special-education-related disputes rose 85 percent from 2007 to 2017.

But despite funding and staffing challenges, de Bruin and other experts view historical bias as the primary hurdle to inclusion. “The problem we’re dealing with is a very entrenched attitude that these children remain ineducable,” de Bruin told me.

As the pandemic raged on and Izzy’s school search grew more urgent, I began to doubt that I just hadn’t looked hard enough and that an inclusive school would pop up out of nowhere. Stuck at home, Izzy wailed with boredom.

I contacted a special-education advocate who happened to work in New York City. The advocate recommended several schools and programs in the city, including a highly rated program for autistic students, a growing movement of intentionally inclusive classrooms , and a Brooklyn preschool with a 25-year history of integrating children with disabilities into regular classrooms. In all my searching, I hadn’t found any such programs in California.

“Can you move?” the advocate asked. She was serious.

Read: The pandemic is a crisis for students with special needs

California had been the backdrop for my entire adult life. It’s where I built my career, earned a master’s degree, developed deep friendships, met my husband, got married, and had two kids. And in the summer of 2021, my husband and I packed up our Oakland bungalow, stuffed our kids into the minivan, and drove away.

Morning drop-offs at Izzy’s new school in Brooklyn are chaotic: Pedestrians maneuver around parents crouching to hug their toddlers, their goodbyes drowned out by garbage trucks. Izzy’s wheelchair appears, pushed by Alanna, Izzy’s dedicated teacher and aide, whom Izzy greets with a gentle high five. I deposit Izzy into the wheelchair; she kicks her feet in anticipation of the day ahead. She might work on her expressive language by mastering ASL signs for “ready” or “music,” or on her receptive language by learning to recognize signs for body parts—two goals specified in her Individualized Education Program. Like her classmates, Izzy is occasionally expected to perform “helper of the day” duties (sorting the attendance ledger, helping a teacher pull lunch boxes from the fridge), which Alanna modifies so Izzy can do them from her wheelchair. In photos shared by her teachers, I can see from the proud smile on Izzy’s face that she gets satisfaction from helping others.

Alanna’s role is to include Izzy by making adaptations that allow her to participate; in official-speak, this is called “accessing the curriculum.” Recently, Izzy had trouble sitting through a 20-minute art lesson. Alanna gradually increased Izzy’s time in the class by a few minutes each day, moved her materials to a quieter spot in the classroom, and found some thicker oil pastels (which require less strength to hold than standard ones). Alanna also helps other kids relate to Izzy by demystifying her disabilities and framing them in neutral and age-appropriate terms. When they call now-5-year-old Izzy a “baby,” Alanna reminds them that Izzy is their same age with a smaller body. Her friends vie for a turn joining her for collaborative games in speech therapy, or to ride with her in the elevator. During recess, Izzy’s wheelchair is a choice prop for playing “queen”—the lucky throne bearer gets to rule the playground kingdom. I recently got a text from the father of one of Izzy’s classmates, a 5-year-old girl who’d been slithering around at home on her stomach—army-crawling in the way toddlers do before they learn to walk. When her dad asked what she was doing, the girl said, “I’m strong like Izzy.”

Izzy and her friends are different and the same. They have different learning needs, but they share a love of barn animals and ukuleles. Sure, Izzy is unique, rare, one in 10,000. But in an ideal world, no child’s specialness would override their contribution to a shared humanity, or be used to justify their separation from everyone else.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

What is Special Education?

There is a system of support available for students with learning differences.

Getty Images

The majority of students with disabilities -- about two-thirds -- are male, according to data from the Pew Research Center on the 2017-18 school year.

For decades, public schools have been required by law to provide a “free and appropriate education” to children with disabilities. The system for making that happen is a complicated web of acronyms and regulations that govern services and support. We call it special education.

Special education refers to a set of federal and state laws and regulations designed to educate millions of children with disabilities and serve as a safety net for those unable to take advantage of the mainstream school curriculum without help.

“The special education laws are a recognition that students with disabilities aren’t able to access an education the way other students can without special supports,” says Ron Hager, managing attorney for education and employment at the National Disability Rights Network. “Special education gives students with disabilities what they need to be successful.”

Special Education by the Numbers

Special education in the United States is governed by the landmark Individuals with Disabilities Education Act , sometimes called IDEA. The law states that children with cognitive, physical, emotional and medical conditions are entitled to special services, supports, technologies and individualized planning and goals outside the general education curriculum.

More than 7 million students , or about 14% of those ages 3 to 21 in public schools, were entitled to special services and accommodations to help with learning in the 2019-20 school year, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

The percentage of students in special education also varies by state, with differences likely due to inconsistencies in how states determine eligibility , as well as challenges that come with diagnosing disabilities. New York serves the largest percentage of disabled students.

Nationwide, the system helps children with disabilities gain a basic education, acquire life skills and integrate with their peers.

During the pandemic, when schooling moved online, that support continued in many cases, says Lindsay Kubatzky, director of policy and advocacy at the National Center for Learning Disabilities.

“As school systems navigated the pandemic, [special education laws] ensured that educators continued to provide high-quality, tailored education to students with disabilities, regardless of circumstances,” he wrote in an email. “In any learning setting, students are still guaranteed the accommodations and resources they need to be successful. The law protects the rights of students with disabilities even in the most challenging of times.”

However, Hager says there is still a great deal of work ahead.

“During the pandemic, no student really got what they needed,” he says. “Going forward, the special education system is going to make sure there is a closer look given so that students with disabilities are caught up.”

Who Receives Special Education Services?

Among all students receiving special education services that year, 34% had a specific learning disability, generally defined as a difference in the way they think, speak, read, write or spell. Dyslexia , a learning disorder that impacts the ability to read, is perhaps the most commonly known learning disability. But over the years, other key challenges have been identified, such as dysgraphia , which impacts writing, and dyscalculia , which impacts math and related activities.

Another 19% had a speech or language impairment. Autistic children made up about 10% of the nation’s disabled students in the 2017-18 school year, compared to about 1.5% in 2000-01, according to NCES data .

“It used to be that one in 10,000 people had autism, and now it is one in 100,” Hager says. “If you ask five different people why that is, you will get six different answers, including environmental factors. But the fact is, autism and the need for services is much more on people’s radars. And there is an understanding that autism is a spectrum, in which you can be high-functioning but also need special education services, particularly social-emotional services.”

The Special Case of ADHD

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder represents a special case when it comes to obtaining support and services at school. ADHD is not identified as one of the 13 federal disability categories that are guaranteed services, though there are ways that children with ADHD can receive help.

When the child has severe ADHD that leads to performing two grades below their level, the disability can be classified as “otherwise health impaired” and the student can be eligible for services under federal law. Less severe cases of ADHD, and other disabilities, can obtain special education services through something called a 504 Plan, which provides accommodations such as preferential seating or extended time on tests.

“Both medically and educationally, our understanding of ADHD continues to improve, but there is still tremendous confusion about what constitutes ADHD,” Elena Silva, director of PK-12 education at New America, a policy organization in Washington, D.C., wrote in an email.

Hager says that students with ADHD are often dismissed as “lazy or disorganized,” when what they actually need is special education supports and accommodations. “Students with ADHD often get shunted aside,” he says.

Obtaining Special Education Services

The first step in receiving special education services is to be identified by a school or district as a student who requires help. A teacher, parent or doctor will document a child’s challenges and make a case for services under the 13 federal disability categories.

Meetings and assessments will take place and a specialized plan known as an Individualized Education Program , or IEP, may be drafted to codify individual goals and accommodations. That plan will be revisited regularly to determine whether the disability classification is still valid and the child is still eligible for special education services.

However, Kubatzky says the system does not always align perfectly with the challenges faced by some students.

“Every student with a disability also presents a unique and individualized set of needs,” he says.

Searching for a school? Explore our K-12 directory .

Best States for Early Education

Tags: education , elementary school , parenting , K-12 education

2024 Best Colleges

Search for your perfect fit with the U.S. News rankings of colleges and universities.

Popular Stories

Best Colleges

College Admissions Playbook

You May Also Like

Choosing a high school: what to consider.

Cole Claybourn April 23, 2024

States With Highest Test Scores

Sarah Wood April 23, 2024

Map: Top 100 Public High Schools

Sarah Wood and Cole Claybourn April 23, 2024

Metro Areas With Top-Ranked High Schools

A.R. Cabral April 23, 2024

U.S. News Releases High School Rankings

Explore the 2024 Best STEM High Schools

Nathan Hellman April 22, 2024

See the 2024 Best Public High Schools

Joshua Welling April 22, 2024

Ways Students Can Spend Spring Break

Anayat Durrani March 6, 2024

Attending an Online High School

Cole Claybourn Feb. 20, 2024

How to Perform Well on SAT, ACT Test Day

Cole Claybourn Feb. 13, 2024

Special Education, Inc.

Private equity sees profit in the business of educating autistic kids. Parents and teachers see diminished services and added stress.

Emily had a lot of fight in her.

The petite 7-year-old had blonde hair and blue eyes. She was also diagnosed with autism, and she had been struggling ever since her mother, Sarah, moved her and her brother hours away from their dad during the pandemic. After the move, Emily became increasingly frustrated with her inability to articulate her thoughts and began boiling over into rages that required interventions at the public school she attended.

So in August 2021, Sarah moved Emily to New Story, a private school in State College, Pennsylvania, dedicated to serving children with special needs, in the hopes that the teachers there would know how to keep her little girl calm. But at New Story, Emily seemed to be having even more meltdowns, and the school called Sarah to intervene when her daughter broke down. So Sarah left work, again and again, to comfort her daughter with bear hugs.

She would rather miss work than let New Story teachers use their preferred tactic: corralling the first grader with gym mats that Emily would fight and scratch so hard, she'd come home with foam lodged beneath her bloody fingernails.

Then one afternoon in April last year, Sarah asked a family friend to pick up Emily from New Story. When the friend arrived, the little girl was on the playground, pinned down under the weight of four adults.

That night, Sarah decided that this nightmare had to end. Emily would not return to New Story. A year later, her daughter still hasn't talked about the incident at home or in therapy. New Story calls itself a "safe, nurturing environment for our students and their families," but Emily has a different term for her old school: "the mean people."

After nearly two semesters of second grade at a public school, Sarah said her daughter has progressed faster, academically and behaviorally, than she did at New Story. When Emily has an in-class meltdown, public school staff discreetly shepherd her to a quiet sensory room to calm down.

"Now, at the very least, I know that she is safe and she can communicate that to me," said Sarah, who asked that we use pseudonyms to protect her daughter. Their identities are known to Business Insider.

Sarah didn't know it at the time, but when she enrolled Emily in New Story, she was unwittingly signing on to an experiment in American education, one that worries former staff, US senators, and special-education researchers alike: New Story is the country's first large-scale special-education-school network owned by a private-equity firm.

In 2019, the Boston-based private-equity arm of Audax Group, which manages $36 billion for investors, including the Kentucky Teachers Retirement System and the Pennsylvania State Employees' Retirement System, purchased a mid-Atlantic special-education-school network called New Story Schools for an undisclosed price. Under Audax, New Story has purchased other local school chains, like Pennsylvania's River Rock Academy, as well as various behavioral-services companies, and rolled them up under New Story's corporate umbrella. The deals have created what New Story calls one of the largest special-education companies in the US, serving children with autism, behavioral problems, and other issues.

Now, Audax is reportedly looking to flip the company . More than a quarter of private-equity-owned companies across industries are sold to other private-equity firms, so the new owners may look much like the current one.

To some, private equity's business model appears antithetical to special education. In a basic private-equity deal, a firm pools money from investors like public pensions to buy a business, improve it (or load it up with debt), and sell it. Fast expansion means the firm can sell the business, typically four to seven years after buying it, and make a profit of 15% to 20% or more. Private equity targets companies that can grow fast, often by acquiring similar businesses.

A private-equity firm also makes money well before offloading the business, including by collecting fees from its investors and charging the businesses it owns for management and advisory services.

Special-education schools bring in a reliable income stream, typically from public funds: School districts and states pay New Story anywhere from $27,000 to $95,000 per student, and some schools operate year-round. (The average public school district in Pennsylvania, where New Story operates the most schools, spends about $23,000 per child across all types of public education. Additional services, such as providing an individual aide or specialized therapy, can push those costs much higher.) And a fragmented nationwide market means that a company like New Story — which Audax grew from 15 schools to a network of 75 schools and centers across seven states — has plenty of opportunities for expansion.

This year, New Story expects to bring in $305 million in revenue, the analytics firm Mergermarket said. The company serves a few thousand students, a tiny slice of the 8 million Americans between the ages of 3 and 21 who receive special-education services each year — a 25% increase from 2011, according to government data . (In 2021-22, 2% of these children attended public or private schools dedicated to students with disabilities.)

Under Audax, New Story gutted departments focused on quality and education and struggled with turnover.

To understand how New Story changed under private-equity ownership and what private-equity takeovers could mean for the special-education landscape, Business Insider reviewed more than 3,000 pages of public records and spoke to 20 current and former New Story employees and parents. Many of them said that under Audax, New Story pushed to expand at the expense of student safety and academic progress. While parental complaints and even lawsuits alleging mistreatment are not uncommon at special-education schools, records of complaints and interviews with parents and educators show that New Story's focus on profit under private-equity ownership added an alarming layer of stress to special education.

Under Audax, New Story gutted departments focused on quality and education and struggled with turnover. The company's hiring practices grew so lax in some instances — including hiring an administrator who was fired from her previous school for failing to report suspected sexual abuse — that state regulators expressed alarm. Some parents, like Sarah, grew concerned about the inappropriate use of restraints and isolation.

Shanon Taylor, a professor at the University of Nevada, Reno, who studies privately run special-education schools, told BI that private equity's push to make big profits is fundamentally at odds with special education's mission. Since the schools are generally paid flat reimbursement rates by school districts or insurers, she said private-equity firms make money by cutting costs.

"They'll cut the number of employees. They'll pay employees less. They'll hire less-qualified employees so they can pay them less. They're going to defer maintenance on their facilities and not have the equipment necessary in those facilities," Taylor said, speaking about private-equity firms generally. "All of those things then are impacting the services to these vulnerable populations."

As a parent of two adults with special needs, Taylor said she would not have sent her children to a private-equity-owned school.

"Most people don't even realize that the school that you may be sending your child to — because you're looking for a specialized setting — may not be run with the best interest of your child at heart," she said.

Top policymakers are concerned, too.

"Private equity has no place in education — especially special education," Sen. Sherrod Brown of Ohio told BI. "From nursing homes to retail to housing, we have seen private equity kill too many jobs, dismantle too many businesses, raise prices, and hurt too many patients in our state, and I am deeply alarmed it is now working to undermine — and endanger — a student's fundamental right to a free and appropriate public education." New Story runs 12 schools and centers in Ohio.

Brown's colleague, Sen. Bob Casey of Pennsylvania, where New Story operates 27 schools, agreed. "Public education dollars should be spent ensuring that students with disabilities have their individual education needs met by qualified teachers and health professionals, not padding the pockets of wealthy private equity executives," he said. Casey chairs the Senate's Health Subcommittee on Children and Families.

'A moneymaking machine'

New Story was founded in 1997 by Paul Volosov, a certified school psychologist who created several for-profit businesses to support adults and children with special needs and other challenges.

Volosov wasn't a perfect owner. Before New Story was acquired by Audax, its schools were the focus of a handful of lawsuits alleging improper treatment of students and employees. And Volosov drew internal scrutiny for his erratic behavior and off-color remarks about women and religion, some former employees said. Volosov stayed on as New Story's CEO until January 2022, when he transitioned to chairman.

Audax filled the company's four C-suite roles with people who had no education or behavioral-health experience.

But former staffers said some of New Story's problems under Volosov were magnified with Audax's ownership. After the education and quality departments were slashed in summer 2022, staff said the disconnect between corporate objectives and the classroom widened. Audax filled the company's four C-suite roles with people who had no education or behavioral-health experience.

"Since the expansion, I think it's just a moneymaking machine," said Jim Grinnen, a former regional manager of education for New Story's central Pennsylvania region. He joined the company in 2018 and left in 2021. "Being a special educator, knowing why I got into it 25 years ago, it just makes your stomach turn when you're seeing these rich people give speeches in front of you with no clue what we're doing here."

Despite those concerns, some parents and educators have expressed satisfaction with the level of care New Story offered. For some families, New Story schools were a last resort, taking a difficult child when no one else would. In Pennsylvania Department of Education records, 11 superintendents and other public school administrators praised one arm of New Story, an 11-campus alternative-education school called River Rock Academy that enrolls disruptive students.

"It is a company that truly cares about the students and treats them as if they were their own. The company provides a high level of service," wrote the superintendent of one Pennsylvania school district in River Rock's application for relicensure.

In an October letter to BI, New Story's senior vice president of operations for Pennsylvania, Christina Spielbauer, highlighted the improvements the "deeply mission-oriented" company has made under Audax, including hiring over 221 new staff members last summer and investing $2 million last year into facilities. Spielbauer wrote that the company was "open to sharing more information" with BI.

Nathaniel Garnick, a spokesman for the company, subsequently declined to answer a list of questions or make New Story or Audax representatives available to interview. Garnick issued two statements, one on behalf of Audax and another on behalf of New Story. He wrote that the company has invested almost $50 million into New Story facilities and improved the student-teacher ratio.

"Rather than focus on the positive impact we have every day on thousands of students with severe emotional and behavioral issues, it is unfortunate that Business Insider has chosen to cherry-pick a handful of isolated incidents in an effort to sully the reputation of our hard working, dedicated team who put their hearts and souls into the work they do," Garnick wrote.

Speaking for Audax, he wrote that staff shortages mean schools are "ill-equipped to confront the escalating mental health crisis on their own."

" Our investment has enabled New Story to expand access and provide vital support to a significantly underserved population of students who often cannot attend traditional public schools," he wrote.

Trying to do more with fewer people

Craig Richards loves teaching and doesn't shy away from a challenge. The elementary-school teacher started a chess club in the Reading School District, one of Pennsylvania's poorest and worst-performing districts. He's also worked in a youth detention center, and his wife is a teacher.

Under its new owners, Richards told Business Insider, River Rock subordinated student care to profits.

In 2017, Richards joined River Rock Academy, which specializes in educating students who can't stay in their public schools because of misconduct. He said staff members at River Rock were caring and tried their best to educate a group of students who often wanted to be anywhere else. Richards left the school after two years. While he was away, New Story bought the school. When he returned for the 2022-23 academic year, he found that the tenor had shifted: Under its new owners, he told Business Insider, River Rock subordinated student care to profits.

"Now since it's New Story, they're definitely more money-driven. They're trying to do more with fewer people," Richards said.

Several former staff members in Pennsylvania said New Story schools there chronically lacked substitute teachers. When Richards missed roughly a week of work during the last academic year for the flu and another three days to take care of his daughter when she broke her foot, behavioral staff — not teachers — covered his classroom.

Asking staff to double as subs might be reasonable if New Story expanded its staff for such needs. But Richards said the school employed fewer staff under New Story than during his first stint, putting extra pressure on teachers to work no matter what.

"It definitely made you feel a little less human. You're not allowed to be sick, your daughter can't have a problem, because we don't have enough people here," he said.

Teacher and staff turnover is a perennial problem for public and private schools nationally that was exacerbated by the pandemic. The people who spoke to BI said New Story turnover is high, even at the top levels. For instance, two Pennsylvania education directors left in spring 2023, according to records obtained by BI — one after just months in the role. Neither was immediately replaced. One Ohio school had four directors, including a 25-year-old, in 2022.

Such director turnover is highly unusual, Judith McKinney, a Virginia-based special-education advocate, said. In her five years evaluating private schools with Virginia's Department of Education, she said directors typically stayed at the same school for years, sometimes decades.

Several grad students working at Green Tree School were so deeply alarmed that they registered their concerns with the Pennsylvania Department of Education

At River Rock, Richards struggled with new curriculum demands under New Story's ownership. His school previously reimbursed teachers who bought worksheets and other items on a popular online marketplace called Teachers Pay Teachers. But last year, River Rock began directing teachers to upload their own worksheets or other material to share with colleagues across River Rock's 11 schools — a closed, unpaid version of Teachers Pay Teachers.

When Richards sought other curriculum resources, he was pointed to a school closet that contained donated materials.

"One of the manuals didn't even have the first unit — it was ripped out," he said. "I'm like, 'Can we look at getting something else?' I had ideas of books we could use. They wouldn't."

Though he loved his colleagues and some aspects of the job, when a position to manage a local running store came up, Richards eagerly took it. He left in June — just two semesters after his return.

(In state paperwork, River Rock said it offers teachers "a variety of textbooks and resources including a resource bank available to them to provide appropriate course content to students based on their individual need.")

Grinnen, the former Pennsylvania administrator, told BI that his schools also struggled with curriculum resources, including having to give 12th graders textbooks written for second graders. That surprised him since the company seemed to have deep pockets to open new locations. Some schools acted more like holding pens than educational facilities, Grinnen said.

Donnell McLean, who briefly ran a New Story campus in Virginia, said the school's lack of a standardized curriculum led to some students being warehoused.

There was "not a lot of challenging work, especially for the higher-functioning students," McLean said.

Last spring, several graduate students working at Philadelphia's Green Tree School were so deeply alarmed by what they saw that they registered their concerns with the Pennsylvania Department of Education. This, along with other complaints, prompted several visits to Green Tree by PDE employees in April and June. One state employee wrote to her supervisor that her visit's "purpose is to do a walk through to determine how much instruction is actually going on based on the complaints that were received." (Subsequent communication about employees' trips was redacted in PDE records obtained by BI.)

In Ohio, New Story administrators told BI they pushed back against the company's plans to increase school enrollment and convert some schools into centers with a half day for school and a half day for therapy. Such a switch would allow New Story to make more money per student by billing insurance companies for more therapy.

While enrollment data is difficult to come by across states, Ohio offers a window into how New Story has increased enrollment without similar teacher increases. Four New Story-branded Ohio schools collectively added 106 students from 2022 to 2024 — a 52% increase — but lost 31 licensed staff, per state data. (BI did not include a recently opened New Story school in this analysis.)

Private equity has been piling into other autism services and similar behavioral-health companies.

Meanwhile, huge additions to the ranks of support staff quickly changed New Story's employee composition. In 2022, support staff comprised 41% of New Story's staff — but 87% this year. For comparison, BI examined 19 other private, secular Ohio special-education schools' data. From 2022 through 2024, those schools' rosters were, on average, made up of about half support staff and half teachers. None had more than 75% support staff, who are generally paid less than teachers and have less training.

(New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Virginia do not track staff numbers for privately run schools.)

New Story employees questioned other corporate changes. Some staff disagreed with a plan to give bonuses to administrators based on student enrollment, something the company discussed across states, two people said.

"Our rationale was we never wanted to create a financial incentive to enroll a student that we couldn't properly serve or to keep a student that was ready to return to their public school," said one of the employees who said they pushed back on the plan.

Not all teachers take issue with New Story's approach. Natalie Stoup teaches seven autistic and intellectually and developmentally disabled students at New Story's New Cumberland, Pennsylvania, campus. Stoup, who has taught for 27 years, said she has loved her two years at the school.

"I absolutely really have a strong respect for the program," she told BI. "I think they're doing wonderful things."

Blackstone's autism bet

While New Story is the first large-scale, private equity-owned special-education school network, Audax's bet comes as private equity has been piling into other autism services and similar behavioral-health companies. Many of the biggest private-equity players have snapped up autism-services providers in the wake of state and federal changes requiring more payments for mental-health and autism services.

That shift made the industry look much more profitable and scalable, magic words for private-equity players like the industry giant Blackstone. In 2018, the firm bought a majority stake in the behavioral-therapy provider Center for Autism and Related Disorders. Blackstone then put the business into bankruptcy proceedings in June, citing labor costs and lease obligations for centers it closed. Forbes reported last year that former employees attributed the company's challenges to a "model that put profits ahead of patient care." (New Story bought CARD's Virginia locations during bankruptcy, and the bulk of the company was sold back to the founder.)

When employee costs rise quickly, companies like CARD and New Story can't pass on the costs to their customers as fast as other businesses, like a restaurant raising menu prices. Insurance reimbursement and school tuition haven't kept pace with the post-pandemic economic landscape, increasing pressure on behavioral-health companies to make money by trimming costs and expanding.

NBC News reported that CARD's staff training decreased under Blackstone's ownership and many employees left after wages stayed stagnant for three years. (Blackstone claimed that it increased training, though staff documents reviewed by NBC News showed the opposite.) Like New Story, CARD's private-equity-installed CEO had no special education or behavioral-health experience.

Other private-equity-owned healthcare companies have recently come under intense regulatory scrutiny. The Biden administration is pressing for transparency for private-equity-owned nursing homes, while the Federal Trade Commission is suing an anesthesiology company and its PE owner for creating what it calls an anticompetitive scheme. PE's special-education and autism-related companies have, so far, largely flown under the radar.

Restraining kids without uniform policies

Educational and disciplinary data about privately run schools like New Story is virtually impossible to obtain — and New Story doesn't volunteer it. The schools are not required to publicly report testing data, attendance, or other markers of school success. And because of the varied student populations, such data would be difficult to compare to public or private schools. In Pennsylvania and Virginia, state Department of Education spokespeople said their agencies don't even keep track of how many students attend private schools.

Nickie Coomer, a Colorado College education professor who has written about the privatization of special education, told BI that this data gap is a major regulatory hole, one that private-equity companies are happy to exploit.

"There's not a lot of accountability about how we're adhering to the laws we have in place to protect kids with disabilities," she said. "There's no governance, no elected school board … It's the antithesis of what schools should be."

One key metric for student safety that's reported at public schools is restraint usage. In most districts, when a student could endanger themselves or others, staff may use restraints, including physically immobilizing the student or isolating them so they can calm down. As with other data, New Story's restraint usage is not publicly reported.

Parents BI talked to had a wide array of experiences, from Sarah's ordeal to others who say New Story's restraint practices have been appropriate and effective for their children. One father of a student who graduated State College's New Story school in 2022 told BI that his young adult son, who frequently needs to be held down at home to avoid self-harm, was always appropriately restrained and the incidents were properly documented.

Interviews with multiple staff members indicate that their training on how to handle challenging student situations varied from school to school.

Donnell McLean, the former Virginia school director, said he never received any restraint training through New Story. Instead, he relied on what he knew from his prior job. In Virginia, public schools are legally required to document any restraint use and notify parents — but McLean said he didn't always receive reports from his staff after they restrained students.

In 2022, an Ohio school director at a New Story school fired an employee who restrained an 11-year-old with such force that his parents sent photos of hand-shaped bruises on the boy's shoulder.

Shyara Hill, a parent of three students at the New Story-owned Green Tree School in Philadelphia, told the Pennsylvania Department of Education that she wasn't properly notified when one of her children was placed in isolation. In emails and phone calls to the agency last spring, Hill detailed other troubling incidents at the school. She reported that one of her children was hurt in a classroom fight but wasn't examined by a nurse; one was repeatedly bullied with no staff intervention; and one came home soiled after staffing shortages prevented them from visiting the restroom.

"The school has not followed the agreement, safety protocols, [or] parent notification plan and has not responded to several communications from myself and [my] child's attorney," Hill wrote in the email, obtained in a public records request from the state Department of Education.

(Neither Hill nor her attorney responded to requests for comment.)

Documents that River Rock sent to Pennsylvania's Department of Education state that restraints "will be used as a last resort" and will be reported to the agency.

A staffer with a criminal record

BI's review of records and litigation turned up alarming lapses in New Story's vetting of new hires as Audax rapidly expanded operations.

This summer, the company hired Amy Hall Kostoff to oversee student services across seven Pennsylvania campuses and serve as the educational director for one of them.

Hall Kostoff was fired in April 2022 from her tenured job as an assistant supervisor at a Pennsylvania county special-education center for failing to properly report suspected sexual abuse involving two students, one of whom is nonverbal. In March 2023, the state's acting secretary of education assessed that Hall Kostoff was dishonest during the subsequent investigation.

A representative for the public school that fired Hall Kostoff declined to comment, including about New Story's background check.

Hall Kostoff, who was still employed at New Story as of late March, declined to comment.

Pennsylvania Department of Education records show that employees were concerned about the hiring practices at Philadelphia's Green Tree School. One department employee wrote to her colleagues in April that staff records at Green Tree were "missing a lot of information," including about background checks and teacher certifications. That employee later wrote that her background check of one Green Tree staff member turned up convictions for public intoxication, disorderly conduct, and indecent exposure — the latter of which would legally prohibit employment at a school. BI was unable to corroborate the PDE employee's claims, and it's unclear if the charges stemmed from incidents in or out of school, or if that employee continued working for Green Tree. The staff member did not respond to requests for comment.

New Story has terminated other staff members accused of wrongdoing, including an occupational therapist in Pennsylvania who was arrested in 2022 and charged with attempting to solicit a minor for sex. A company spokeswoman told a local newspaper the charges did not involve a New Story student.

In 2022, the principal of a New Story-owned school in Rochelle Park, New Jersey, told police that graduates of the school had received sexually inappropriate messages from their former gym teacher, who was still employed there. The teacher wrote to the female students about how he "was sexually attracted to students while they attended the school," and he named specific students, a police report said. (The students told police that no inappropriate behavior occurred while they attended the school.) The teacher also asked another former student if they wanted to smoke weed and gave the former student his Snapchat handle. The police report said the teacher was placed on leave pending an internal investigation; it is unclear whether further action was taken. A detective advised against pursuing charges because the former students are adults, and the messages, "though inappropriate," were not illegal, he wrote. Asked if the teacher was still employed, New Story's spokesman declined to answer and the school's principal did not respond to a request for comment.

Love, Emily

In State College, Emily is thriving in public elementary school. She splits her time between mainstream and special-education classes, spending time with her peers in a way she never did at New Story, where she was the school's only young student.

(Researchers told BI that students miss out on building key social skills when they're sequestered in special-education programs.)

This year, Emily has attended a birthday party and playdates, the kinds of childhood interactions Sarah feared she'd never experience.

"I want my children to be sound, functioning, responsible adults, but I don't want to break their spirits," Sarah said.

She said that public school employees have been kinder — a New Story staff member once said Emily had a "nasty side" — and that Emily is behaving better.

She recently asked Sarah how to sign a card with "love, Emily."

Do you have a story to share? Email this reporter on a non-work device at [email protected] .

Related stories

More from Finance

Most popular

- Main content

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 17 April 2024

Students with special educational needs in regular classrooms and their peer effects on learning achievement

- V. B. Salas García ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7568-3879 1 &

- José María Rentería ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6486-0032 2

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 521 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

375 Accesses

8 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Development studies