National Endowment for the Arts

- Grants for Arts Projects

- Challenge America

- Research Awards

- Partnership Agreement Grants

- Creative Writing

- Translation Projects

- Volunteer to be an NEA Panelist

- Manage Your Award

- Recent Grants

- Arts & Human Development Task Force

- Arts Education Partnership

- Blue Star Museums

- Citizens' Institute on Rural Design

- Creative Forces: NEA Military Healing Arts Network

- GSA's Art in Architecture

- Independent Film & Media Arts Field-Building Initiative

- International

- Mayors' Institute on City Design

- Musical Theater Songwriting Challenge

- National Folklife Network

- NEA Big Read

- NEA Research Labs

- Poetry Out Loud

- Save America's Treasures

- Shakespeare in American Communities

- Sound Health Network

- United We Stand

- American Artscape Magazine

- NEA Art Works Podcast

- National Endowment for the Arts Blog

- States and Regions

- Accessibility

- Arts & Artifacts Indemnity Program

- Arts and Health

- Arts Education

- Creative Placemaking

- Equity Action Plan

- Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs)

- Literary Arts

- Native Arts and Culture

- NEA Jazz Masters Fellowships

- National Heritage Fellowships

- National Medal of Arts

- Press Releases

- Upcoming Events

- NEA Chair's Page

- Leadership and Staff

- What Is the NEA

- Publications

- National Endowment for the Arts on COVID-19

- Open Government

- Freedom of Information Act (FOIA)

- Office of the Inspector General

- Civil Rights Office

- Appropriations History

- Make a Donation

Research into the value and impact of the arts is a core function of the National Endowment for the Arts. Through accurate, relevant, and timely analyses and reports, the Arts Endowment elucidates the factors, conditions, and characteristics of the U.S. arts ecosystem and the impact of the arts on other domains of American life.

The NEA has four priority areas of research:

- Health and wellness for individuals

- Cognition and learning

- Economic growth and innovation

- In what ways do the arts contribute to the healing and revitalization of communities ?

- What is the state of diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility in the arts ?

- How is the U.S. arts ecosystem adapting and responding to social, economic, and technological changes and challenges to the sector?

NEA Research Agenda: FY 2022-2026

Infographic of high-level research priorities

Research Agenda Planning Study

Research Stories

Quick Study Podcast : This monthly audio feature uses research to explore the arts sector and to demonstrate the arts’ value in everyday life.

Measure for Measure : Monthly arts research blog post.

Arts Research & Data

Research Publications NEA-produced in-depth reports and analyses of research topics in the arts, such as:

- Arts Participation Patterns in 2022: Highlights from the Survey of Public Participation in the Arts

- Online Audiences for Arts Programming: A Survey of Virtual Participation Amid COVID-19

- Tech as Art: Supporting Artists Who Use Technology as a Creative Medium

- Arts Strategies for Addressing the Opioid Crisis: Examining the Evidence

Arts and Cultural Production Satellite Account The NEA partners with the Bureau of Economic Analysis (U.S. Department of Commerce) to provide annual reports of the economic impact of arts and culture in the United States.

Arts Data Profile Series Collections of statistics, graphics, and summary results from data-mining about the arts. Examples include datasets from the Survey for Public Participation on the Arts (SPPA), the Arts Basic Survey (ABS), the American Community Survey (ACS), and more.

Research Grants in the Arts Study Findings Working papers, publications, and presentations that so far have resulted from NEA Research Grants in the Arts funding. Topics include economy/workforce, arts participation, health, and education.

Research Labs Information on the NEA's current Research Labs, transdisciplinary research teams, grounded in the social and behavioral sciences, engaging with the NEA five-year research agenda.

National Archive of Data on Arts & Culture Hosted by the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research at the University of Michigan. A webinar tour around the latest data on arts and culture at the National Archive of Data on Arts and Culture is now available .

The NEA’ Research Awards cover two funding opportunities for research projects that engage with the NEA’s five-year research agenda :

Research Grants in the Arts: Support for research studies that investigate the value and/or impact of the arts, either as individual components of the U.S. arts ecology or as they interact with each other and/or with other domains of American life.

Research Labs: Transdisciplinary research teams investigating the value and impact of the arts.

Initiatives

Sound Health Network A partnership of the NEA with the University of California, San Francisco in collaboration with the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, and Renée Fleming, the center’s artistic advisor. The Sound Health Network (SHN) was established to promote research and public awareness about the impact of music on health and wellness. Visit SHN’s website for a database of key scientific publications on music and health research, webinars, funding opportunities, and more.

Creative Forces: NEA Military Healing Arts Network An initiative of the NEA in partnership with the U.S. Departments of Defense and Veterans Affairs that seeks to improve the health, well-being, and quality of life for military and veteran populations exposed to trauma, as well as their families and caregivers. Creative Forces is investing in research on the impacts and benefits—physical, social, and emotional—of these innovative treatment methods. Visit Creative Forces’ National Resource Center to learn more and to read all research associated with Creative Forces.

Arts & Human Development Task Force From 2011-2023, this federal interagency task force encouraged research on the arts and human potential.

Additional Resources

Program Evaluation and Performance Measurement Links to online resources about program evaluation and performance measurement for arts organizations.

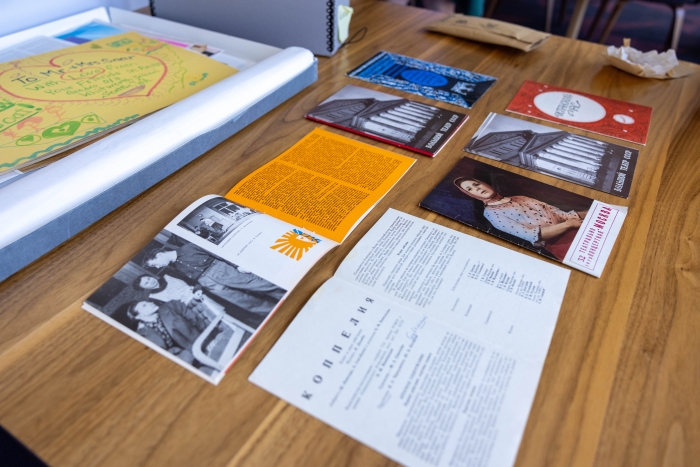

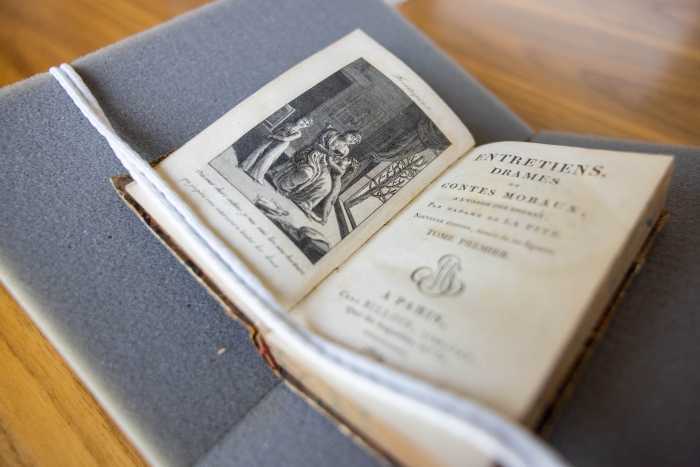

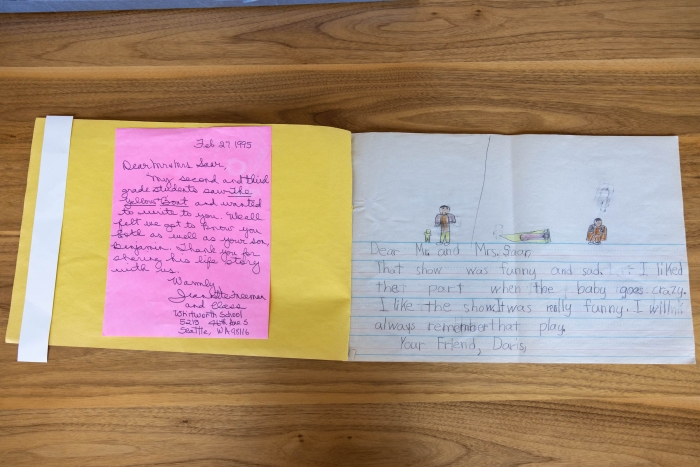

UMass Amherst NEA Archives Collection A digitization of more than 40 years of publications on the arts and arts management.

Research Convenings (archived) National gatherings with researchers and arts and community experts.

OLD TEXT Research Agenda: FY 2022‐2026

This document sets forth a five‐year research agenda for the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA). In preparing this agenda, the NEA’s Office of Research & Analysis supervised a planning study that included a review of NEA research activities in the past decade, and arts-related research supported by other federal agencies. The study also used focus group meetings and interviews with field experts to gather views on priority research areas. These activities preceded a public comment period. The resulting agenda aligns with the NEA’s FY 2022-2026 strategic plan, to be published in early 2022. The agenda is based on results from a planning study conducted in 2019-2020.

See an infographic of high-level research priorities, as discussed in the agenda.

Research Publications The Arts Endowment produces in-depth reports and analyses of research topics in the arts that demonstrate the value and impact of the arts in communities throughout the country.

Arts and Cultural Production Satellite Account The National Endowment for the Arts partners with the Bureau of Economic Analysis (U.S. Department of Commerce) to provide annual reports of the economic impact of arts and culture in the United States.

Arts Data Profile Series Collections of statistics, graphics, and summary results from data-mining about the arts.

Research Grants in the Arts Study Findings Working papers, publications, and presentations that so far have resulted from NEA Research Grants in the Arts funding.

National Endowment for the Arts Research Labs Transdisciplinary research teams investigating the value and impact of the arts.

Sound Health Network A partnership of the Arts Endowment with the University of California, San Francisco in collaboration with the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, and Renée Fleming, the center’s artistic advisor. The Sound Health Network was established to promote research and public awareness about the impact of music on health and wellness.

Creative Forces: NEA Military Healing Arts Network Creative arts therapies at the core of patient-centered care for military members, veterans, and their families.

Arts & Human Development Task Force The federal interagency task force established in 2011 to encourage research on the arts and human potential.

Quick Study Podcast

A new monthly audio feature using research to explore the arts sector and to demonstrate the arts’ value in everyday life. Listen

Research Convenings National gatherings with researchers and arts and community experts.

Creative Forces National Resource Center/Clinical Research Findings Creative Forces invests in research on the impacts and benefits – physical, emotional, social, and economic – of creative arts therapies as innovative treatment methods.

National Archive of Data on Arts and Culture Hosted by the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research at the University of Michigan. A webinar tour around the latest data on arts and culture at the National Archive of Data on Arts and Culture is now available .

Recent Research News

Arts & Cultural Sector Hit All-Time High in 2022 Value Added to U.S. Economy

New Resource from the NEA Will Monitor the Health and Vitality of the Arts in the U.S.

National Endowment for the Arts Announces More Than $32 Million in Arts Funding to Organizations Nationwide

Research blog posts.

Can the Arts Fortify State Economies in Times of Financial Crisis? Yes, Apparently

The expressive life of institutions—and other observations from the #healbridgethrive summit, indelible ink: the lasting benefits of print media for reading comprehension, stay connected to the national endowment for the arts.

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Performing arts as a health resource? An umbrella review of the health impacts of music and dance participation

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Institute for Music Physiology and Musicians’ Medicine, Hannover University for Music, Drama and Media, Hannover, Germany, Prince of Wales Clinical School, Faculty of Medicine, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia

Roles Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Division of Dance Science, Faculty of Dance, Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance, London, United Kingdom

Roles Data curation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Institute for Music Physiology and Musicians’ Medicine, Hannover University for Music, Drama and Media, Hannover, Germany

- J. Matt McCrary,

- Emma Redding,

- Eckart Altenmüller

- Published: June 10, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252956

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

An increasing body of evidence notes the health benefits of arts engagement and participation. However, specific health effects and optimal modes and ‘doses’ of arts participation remain unclear, limiting evidence-based recommendations and prescriptions. The performing arts are the most popular form of arts participation, presenting substantial scope for established interest to be leveraged into positive health outcomes. Results of a three-component umbrella review (PROSPERO ID #: CRD42020191991) of relevant systematic reviews (33), epidemiologic studies (9) and descriptive studies (87) demonstrate that performing arts participation is broadly health promoting activity. Beneficial effects of performing arts participation were reported in healthy (non-clinical) children, adolescents, adults, and older adults across 17 health domains (9 supported by moderate-high quality evidence ( GRADE criteria )). Positive health effects were associated with as little as 30 ( acute effects) to 60 minutes ( sustained weekly participation ) of performing arts participation, with drumming and both expressive ( ballroom , social ) and exercise-based ( aerobic dance , Zumba ) modes of dance linked to the broadest health benefits. Links between specific health effects and performing arts modes/doses remain unclear and specific conclusions are limited by a still young and disparate evidence base. Further research is necessary, with this umbrella review providing a critical knowledge foundation.

Citation: McCrary JM, Redding E, Altenmüller E (2021) Performing arts as a health resource? An umbrella review of the health impacts of music and dance participation. PLoS ONE 16(6): e0252956. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252956

Editor: Emily S. Cross, University of Glasgow, UNITED KINGDOM

Received: December 15, 2020; Accepted: May 25, 2021; Published: June 10, 2021

Copyright: © 2021 McCrary et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding: JMM was supported by a Postdoctoral Fellowship from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

1. Introduction

Participation and receptive engagement in the arts are increasingly recognized as being health promoting, most notably in policy briefs [ 1 ], a recent World Health Organization-commissioned scoping review [ 2 ], and social prescribing initiatives [ 3 ]. However, the widespread integration of the arts into healthcare and public health practices is limited by a disparate evidence base; the specifics of the most effective arts interventions–namely the mode (specific ‘type’ of art–e.g. ballroom dance, singing) and ‘dose’ (frequency and timing/duration)–for various clinical and public health scenarios are still unclear [ 4 ]. Consequently, formulation of evidence-based arts prescriptions and recommendations is presently difficult [ 4 ].

Participation in the performing arts is the most popular form of arts participation, with up to 40% of EU and US adults participating annually in performing arts activities [ 5 , 6 ]. Within the performing arts, music and dance participation are the two most popular modes of engagement, both involving engagement with music, and proposed to have common evolutionary origins [ 7 – 9 ]. The health effects of music and dance participation were thus considered likely to be both related and broadly studied and are the focus of this review. ‘Performing arts participation’ will be used to refer, jointly, to music and dance participation from this point forward.

Performing arts participation is particularly intriguing in a health context in that it combines creative expression with intrinsic levels of physical exertion associated with many health benefits (e.g. moderate–vigorous intensity cardiovascular demands) [ 10 ]. Both creative arts and physical activity have been independently linked to broad health benefits [ 2 , 11 – 13 ], albeit with a more robust body of evidence supporting the substantial and widespread health impact of physical activity–primary and/or secondary prevention for at least 25 chronic medical conditions and a 9–39% reduction in overall mortality risk [ 12 , 14 , 15 ]. Performing arts and exercise/ physical activity participation are distinguished by a distinctly expressive, rather than exertive, focus of the performing arts; exertion is an intrinsic byproduct, not an objective. Accordingly, the health impact of performing arts participation must be evaluated using frameworks that allow performing arts to remain a primarily expressive activity, but also consider the likely impact of intrinsic physical exertion.

Evidence regarding the full breadth of health impacts of performing arts participation, as well as the modes and doses underpinning these effects, has yet to be compiled, critically appraised and analyzed using a common framework. This umbrella review aims to address this knowledge gap by systematically reviewing and appraising evidence regarding the health effects of performing arts participation, including its impacts on both broad mortality and disease risk and more discrete health-related outcomes, in healthy (non-clinical) adults, adolescents and children. Performing arts participation is hypothesized to have similar health effects as physical activity due to its intrinsic physical exertion, as well as additional effects related to creative expression and engagement with music. Accordingly, a secondary aim of this review is to compile data regarding the intrinsic physical intensity of varying modes of performing arts participation to inform further hypotheses related to relationships between physical intensity and observed effects.

2.1 Review registration

This review was prospectively registered in the PROSPERO registry (ID: CRD42020191991).

2.2 Overview

Following informal literature searches, the authors made an a priori decision that an integrated, three component umbrella review would most effectively address study aims:

- A systematic review of systematic reviews of the health effects of performing arts participation;

- A systematic review of observational studies investigating the impact of performing arts participation on mortality and non-communicable disease risk. NB : initial searches revealed no prior systematic reviews addressing the effects of performing arts participation on mortality and/or non-communicable disease risk .

- A systematic review of studies of heart rate responses to performing arts participation.

Search terms and inclusion/exclusion criteria for each component are described below. All components involved searches of MEDLINE ( all fields , English & human subjects limiter ), EMBASE ( all fields , English & human subjects limiter ), SPORTDiscus ( all fields , English limiter ), and Web of Science ( Arts & Humanities citation index; all fields; English limiter) from inception– 15 June 2020. Abstracts of all database search results were screened, followed by full text review of potentially relevant articles. Hand searches of the reference lists of included articles were also conducted to locate additional relevant articles. The review procedure was conducted by the first author in consultation with the authorship team.

Across all components, ‘music participation’ was defined as singing or playing a musical instrument. ‘Dance participation’ was broadly defined as an activity involving “moving one’s body rhythmically…to music” [ 16 ], with an additional criterion that included articles must identify the investigated activity as ‘dance.’ Articles investigating music and dance participation conducted with an exertive aim (i.e. music or dance session(s) designed to elicit a target heart rate/rating of perceived exertion) were excluded to maintain review focus on performing arts vs. exercise participation. As noted in the introduction, performing arts participation is distinguished from exercise participation by its distinctly expressive, rather than exertive, focus; exertion is an intrinsic byproduct, not an objective.

2.3 Systematic review of systematic reviews of the health benefits of performing arts participation

2.3.1 database search terms..

Database searches were performed using the following search terms and a ‘Reviews’ limiter where available: ((music* OR danc* OR performing art* OR choir OR choral) AND (psycholog* OR biochem* OR immun* OR cognit* OR physical OR health)).

2.3.2 Inclusion/Exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria were systematic reviews examining the health effects of active performing arts participation in healthy adults, adolescents or children. A ‘systematic review’ was defined based on Cochrane definitions [ 17 ] as a review conducted using explicit, reproducible methodology and aiming to comprehensively synthesize all available relevant evidence. Exclusion criteria were assessed at the primary study level within relevant reviews: 1) studies with qualitative data only; 2) studies in which performing arts participation was conducted with a target exercise intensity or heart rate–these studies were judged to evaluate exercise, rather than performing arts participation; 3) studies of long-term dance or music interventions in experienced dancers or musicians; 4) single-group observational studies characterizing experienced dancers or musicians.

Systematic reviews including a mixture of primary studies meeting and not meeting inclusion/exclusion criteria were included if:

- Reviews in which study results were quantitatively synthesized (i . e . meta-analysis) –The majority (>50%) of included studies examined active performing arts participation in healthy populations and met no exclusion criteria

- Reviews in which results were narratively synthesized (i . e . descriptive synthesis of quantitative primary study results )–The results of primary studies of active participation in healthy populations meeting no exclusion criteria could be extracted and re-synthesized for the purposes of this review.

2.3.3 Data extraction.

Demographic and outcome data were extracted for all included reviews and their underlying primary studies meeting inclusion criteria and no exclusion criteria. For each outcome, the effect of performing arts participation was determined to be ‘positive’, ‘negative’, ‘no effect’, or ‘unclear’. Designations of ‘positive’, ‘negative’ and ‘no effect’ were given in cases where clear links between changes in a parameter and a corresponding positive/negative health effect exist in healthy populations (e.g. shift from pro- to anti-inflammatory tone–positive effect; delayed pubertal onset–negative effect). An ‘unclear’ designation was given in cases where such links between changes in a parameter and health effects do not exist (e.g. acute increase in IL-6).

2.3.4 GRADE quality of evidence appraisal.

The GRADE system was favored for this review because of its alignment with review aims and applicability to systematic reviews of systematic reviews [ 17 ]; GRADE is specifically “designed for reviews…that examine alternative management strategies” [ 18 ]. The GRADE system results in an appraisal of the quality of evidence supporting conclusions related to each outcome of interest—very low; low; moderate; high. Specific criteria and appraisal methodology are detailed in the S1 Appendix .

2.3.5 Evidence synthesis.

To minimize the biasing effects of overlapping reviews, all outcomes from primary studies included in multiple reviews were only considered once. The lone exception to this was one outcome (flexibility–sit & reach) from one primary study of dance [ 19 ] which was included in multiple meta-analyses [ 20 , 21 ] and thus considered twice. Re-calculation of meta-analyses to remove this duplication was not considered necessary due to consistent effects of dance on flexibility across 4 reviews considering 15 individual studies [ 20 – 23 ]. Common outcomes were first combined and assigned a grouped health effect and GRADE appraisal at the review level. Outcomes and GRADE appraisals were then combined across reviews and assigned a health effect and GRADE appraisal at the umbrella review level. Where appropriate, outcome results were stratified by music/dance participation, sex, age, GRADE appraisal, or instrument/style. Outcomes were categorized by domain–domains used to organize evidence of the health benefits of physical activity were used as an initial framework, with additional domains added as required [ 12 ]. Specific outcomes contained within each category are detailed in S1 Table in S1 Appendix .

2.4. Systematic review of observational studies investigating the impact of performing arts participation on mortality and non-communicable disease risk

Given an absence of known reviews of epidemiologic data regarding performing arts participation and the importance of these data in evaluating health effects, the authors made an a priori decision to conduct a separate systematic review.

2.4.1 Search terms.

Databases were searched using the following terms: ((music* OR danc* OR performing art* OR choir OR choral) AND (mortality OR public health OR disease OR risk) AND epidemiology).

2.4.2 Inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria were observational studies investigating the relationship between performing arts participation and all-cause mortality or non-communicable disease risk and/or non-communicable disease risk factors (i.e. metabolic syndrome) in adults, adolescents or children. No exclusion criteria were defined.

2.4.3 Evidence synthesis, GRADE appraisal and synthesis.

Conducted using an adaptation of the procedure detailed in sections 2.3.3–2.3.5, with included primary studies appraised individually and then synthesized at the level of this systematic review.

2.5 Systematic review of studies of heart rate responses to performing arts participation

2.5.1 search terms..

Database searches were performed using the following search terms: ((music* OR danc* OR performing art* OR choir OR choral) AND (load OR intensity OR heart rate)).

2.5.2 Inclusion/Exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria were studies reporting average/mean heart rate data collected from at least 1 minute of a representative period of active music or dance participation in any setting. Studies reporting heart rate such that raw heart rate data (beats per minute) could not be extracted were excluded.

2.5.3 Data extraction and appraisal.

Demographic and raw heart rate data were extracted from all included studies. Raw heart rate data were calculated where necessary (i.e. from data expressed as % maximum heart rate). Rigorous application of inclusion/exclusion criteria was used in lieu of a formal assessment of evidence quality.

2.5.4 Evidence synthesis.

%HR max values were then categorized by intensity according to American College of Sports Medicine definitions [ 26 ].

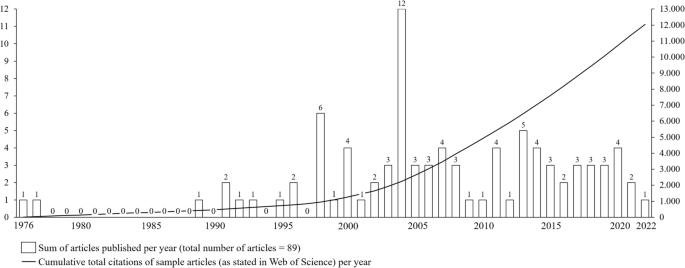

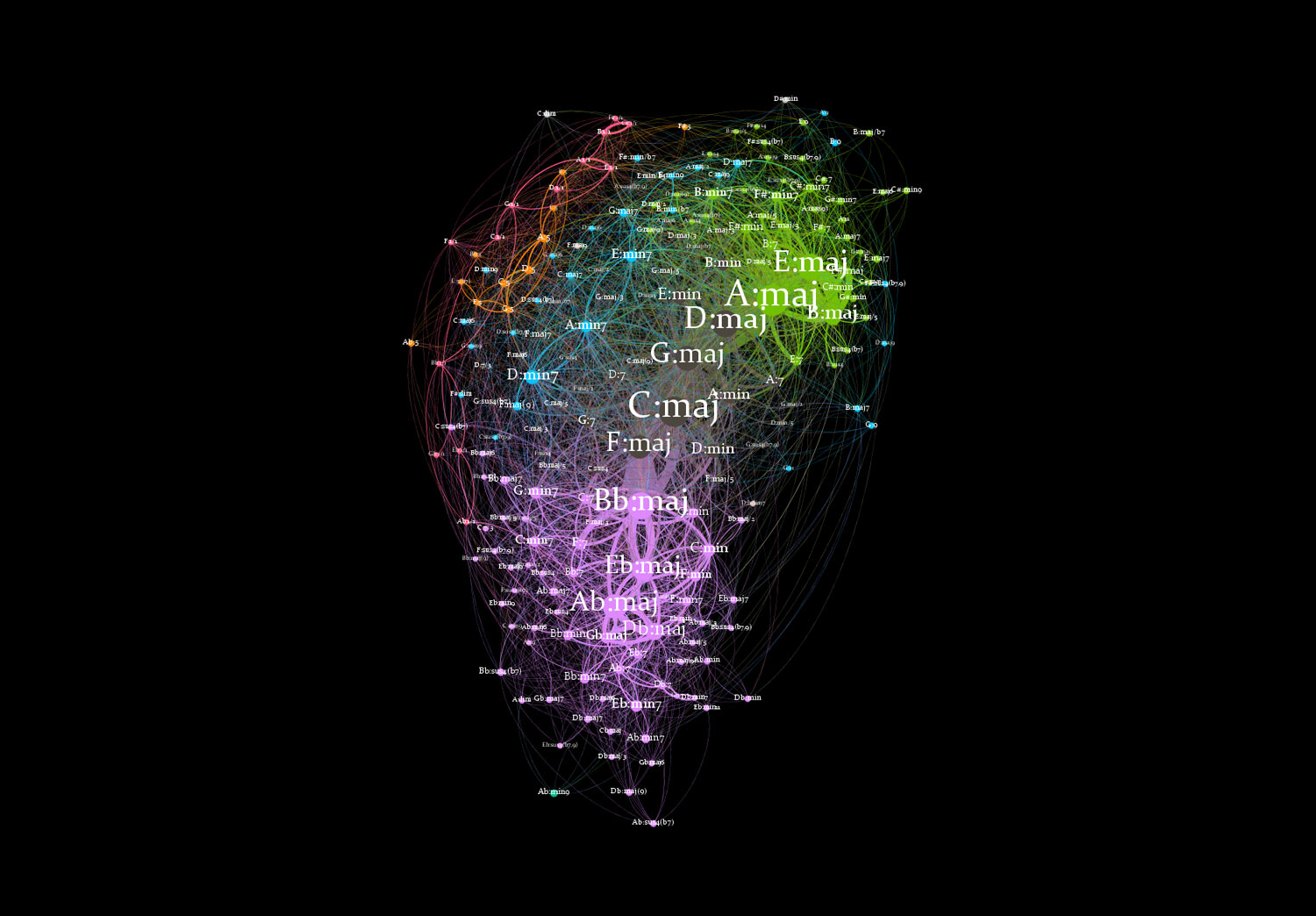

3.1 Systematic review statistics ( Fig 1 )

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

Specific details regarding excluded reviews/studies are contained in the S1 Appendix .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252956.g001

This umbrella review includes 33 systematic reviews of the health effects of performing arts participation (15 dance; 18 music), encompassing 286 unique primary studies (128 dance; 158 music) and 149 outcomes across 18 health domains. Additionally, 9 observational studies investigating the impact of performing arts participation on mortality and non-communicable disease risk (3 dance, 5 music, 1 dance & music) were included, as well as 87 studies reporting heart rate responses during performing arts participation (71 dance, 16 music). Review articles and observational studies of mortality and non-communicable disease risk are directly referenced in this manuscript (Tables 1 and 2 ); the complete list of references, including studies investigating heart rate responses, is contained in the S1 Appendix .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252956.t001

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252956.t002

3.2 General health effects of active performing arts participation

Positive effects of performing arts participation were reported in 17 of 18 investigated domains–only glucose/insulin outcomes were consistently reported to be unaffected by dance participation (no data related to music participation)( Table 1 ). Positive effects in 9 domains ( auditory; body composition; cognitive; immune function; mental health; physical fitness; physical function; self-reported health/wellbeing; social wellbeing ) were supported by moderate to high quality evidence; results in 4 of these 9 domains ( cognitive; mental health; physical fitness; self-reported health/wellbeing ) included a mixture of positive and neutral/no effects varying by specific outcome ( Table 2 ). Positive effects of performing arts participation were found in 9 of 13 domains (7 of 13 supported by moderate-high quality evidence) associated with the mechanisms of physical activity benefits (Tables 1 and 2 ) [ 12 , 28 ]. Raw data underpinning summary results and GRADE appraisals are detailed in the S1 Appendix .

Effects of performing arts participation were investigated in adult populations ( age 20–59 ) across all domains backed by moderate-high quality evidence. Benefits of performing arts participation ( moderate-high quality evidence ) in children ( age 0–9 ) and adolescents ( age 10–19 ) were reported in auditory (music), body composition (dance), cognitive (music), and physical fitness (dance) domains; positive effects of dance on adolescent mental health were also reported. Benefits of performing arts participation were reported in older adults ( age ≥60; moderate-high quality evidence ) across cognitive (dance); immune function (music), mental health (dance), physical fitness (dance), physical function (dance), self-reported health/wellbeing (music & dance), and social functioning (music & dance) domains.

3.3 Modes and ‘doses’ of performing arts participation associated with reported health effects ( Table 2 ; moderate–high quality evidence only)

The effects of dance participation were more broadly supported by higher quality evidence– 34 individual outcomes, with positive effects reported across 7 domains ( body composition; cognitive; mental health; physical fitness; physical function; self-reported health/wellbeing; social functioning ). The effects of music participation were supported by moderate to high quality evidence for 11 individual outcomes, with reported positive effects in 5 domains ( auditory; cognitive; immune function/inflammation; self-reported health/wellbeing; social functioning ). Modes of performing arts participation associated with the broadest positive health effects were: aerobic dance (4 domains ); ballroom dance ( 4 domains ); social dance ( 4 domains ); drumming ( 3 domains ); and Zumba dance ( 3 domains ).

Acute doses ( single session lasting 30–60 minutes ) were sparsely associated with positive effects—hip-hop dance benefited mental health (mood) and music participation (drumming; singing) was associated with positive changes in immune function/inflammation, self-reported health/wellbeing (fatigue), and social functioning (anger). All other results were based on studies of sustained performing arts participation. Significant heterogeneity in frequency and timing of sustained participation was found. Positive health effects were associated with sustained performing arts participation lasting at least 4 weeks, with a minimum of 60 minutes of weekly participation and at least one weekly session. Each individual session in intervention studies lasted 21–120 minutes; the length of individual sessions in cross-sectional studies of performing arts participants vs. non-participants was generally not reported.

3.4 Physical demands of performing arts participation

Heart rate responses to performing arts participation widely varied by style and/or performance setting, with studies of both music and dance participation reporting heart rates classified as very light, light, moderate, and vigorous intensity physical activity (Tables 3 and 4 ). Heart rate also varied substantially within the same mode of music/dance participation, with 16 modes (12 music; 4 dance) associated with heart rate responses at two intensity levels, 3 modes (1 music–trumpet; 2 dance–ballet, modern) associated with heart rate responses at three intensity levels, and active video game dancing associated with heart rate responses at all four intensity levels. Raw heart rate data underpinning summary results are detailed in the S1 Appendix .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252956.t003

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252956.t004

4. Discussion

This umbrella review presents an expansive and detailed synthesis and appraisal of evidence demonstrating that performing arts participation is, broadly, health promoting activity, with positive effects across 17 health domains. Moderate-high quality evidence supported positive effects across 9 of these domains, including 7 of 13 domains associated with the health benefits of physical activity. Positive effects were reported in adult populations across all 9 domains, with beneficial effects in children, adolescents, and older adults reported across 4, 5, and 7 domains, respectively. This review also provides preliminary insights into the modes and doses of performing arts participation underpinning observed benefits. Further, heart rate data from 87 additional studies indicate that both music and dance participation intrinsically elicit mean heart rate values corresponding to a range of intensities, including moderate and vigorous.

This review also reveals that the evidence regarding the health impacts of performing arts participation is still in its infancy. Accordingly, reported health benefits and preliminary insights regarding effective performing arts modes and doses must be considered within this context. Moderate-high quality results provide valuable guidance but should not be interpreted as supporting the totality of health benefits or superiority of modes or doses of performing arts participation. Key results of this review are due to greater amounts of high-quality studies of specific modes and doses in particular domains; the overall quality of included evidence is generally low ( 26% (45/173) of outcomes backed by moderate-high quality evidence ) due to a predominance of non-randomized and observational vs. randomized controlled trial study designs. Control and comparison groups varied widely across all study types, including no-intervention/waitlist control groups and exercise (various types), cognitive and/or language training and other art participation (e.g. visual art, drama) comparison groups.

All included studies were conducted without explicit intensity aims, yet 2 of 4 modes of dance participation associated with the broadest health benefits come from exercise, not artistic, traditions: aerobic dance [ 67 ] and Zumba [ 68 ]. Heart rate data ( Table 4 ) unsurprisingly confirm that both modes are associated with moderate to vigorous intensity physical demands as per global physical activity recommendations [ 69 ]. However, two traditionally expressive modes of dance–ballroom and social–were found to have similarly broad benefits, including in physical fitness and function domains. Heart rate data for ballroom and social dancing were sparsely available, precluding discussion of the potential impact of intrinsic physical intensity. Nonetheless, these results suggest that expressive dance participation is similarly health promoting to modes created from an exercise viewpoint. Further obscuring the relationships between physical intensity and observed benefits, drumming was the most broadly health promoting mode of music participation and associated, across various settings, with very light, light, moderate, and vigorous intensity heart rate responses. Additional research is needed to establish the relationships between intrinsic physical intensity and health impacts during performing arts participation.

Both acute and sustained performing arts participation were associated with health benefits, although the bulk of evidence relates to sustained participation. Acute benefits of singing and drumming on inflammation and immune parameters are particularly intriguing; similar short-term effects have been associated with physical activity and linked, with sustained participation, to long-term preventive benefits [ 70 ]. Epidemiologic studies suggest similar links between sustained performing arts participation and a reduced risk of non-communicable diseases and early mortality. However, the quality of these epidemiologic studies is presently low and specifically limited by the use of a range of bespoke survey instruments with unclear psychometric value to quantify the frequency, timing/duration and type of performing arts participation. Future studies using validated instruments for quantifying performing arts participation are needed.

The majority of health benefits backed by moderate-high quality evidence were associated with sustained performing arts participation lasting at least four weeks. Although substantial heterogeneity in results limits conclusions regarding the impact of specific doses of the performing arts, all reported benefits were associated with at least weekly participation. Some benefits were seen with as little as 60 minutes of weekly participation, demonstrating that, like physical activity, significant health benefits can be achieved with modest effort and time commitment [ 14 ]. Physical activity evidence indicates that greater levels of weekly participation are associated with greater health benefits–‘ some is better than none, more is better than less’ [ 14 ]. Substantial further research is required to determine the impact of the frequency and duration of performing arts participation on health benefits, as well as the potential additional impact of the setting (e.g. laboratory, classroom, live performance) of performing arts participation on observed benefits.

In sum, this review presents promising evidence regarding the health benefits of performing arts participation, but is limited by a young and disparate evidence base, as well as additional factors discussed below. Excepting studies of non-communicable disease risk, this umbrella review was limited to English language studies included in systematic reviews of the health effects of performing arts participation. It is thus probable that some primary studies were not considered; their exclusion could impact individual outcome results given the aforementioned infancy of the evidence base. However, it is less likely that individual primary studies would significantly impact the general conclusions of this review, which are based on aggregated moderate-high quality evidence grouped by domain of health impact.

This review is also potentially limited by the conduct of literature searches, data extraction, and evidence appraisal by the first author alone, in consultation with the authorship team, due to resource constraints. Single author search, extraction and appraisal has been demonstrated to increase the incidence of errors [ 71 ], yet these errors have been found to have a minimal impact on review results and conclusions [ 72 ]. To best meet study aims, the authors thus favored a broad, single author search, extraction and appraisal over a more constrained review conducted by multiple authors in duplicate. Additionally, the inclusion of a comprehensive and transparent S1 Appendix detailing all review data and subjective decision-making (i.e. article inclusions, GRADE appraisals) clarifies the basis for specific conclusions and serves as a foundation for discussion and future research.

Finally, while studies of participation-related performing arts injuries were beyond the scope of this review, it should be noted that, similar to exercise participation [ 73 ], the health impact of performing arts activities is not exclusively positive. Participation in performing arts does carry an injury risk, for example caused by overpractice [ 10 ]. These risks are considerably counterbalanced by the broad benefits of performing arts participation demonstrated in this review. However, on an individual level, participation risks must always be managed and weighed against potential benefits.

4.1 Conclusions

Performing arts participation is, broadly, a health promoting activity, with beneficial effects reported across healthy (non-clinical) children, adolescents, adults, and older adults in 17 domains (9 supported by moderate-high quality evidence). Positive health effects were associated with as little as 30 ( acute participation ) or 60 ( sustained weekly participation ) minutes of performing arts participation, with drumming and both expressive ( ballroom , social ) and exercise-based ( aerobic dance , Zumba ) modes of dance linked to the broadest health benefits. However, the evidence base is still very much in its infancy. Further research is necessary to optimize modes and doses of performing arts participation towards specific health effects, as well as clarify relationships between intrinsic physical intensity and observed benefits. The broad yet rigorous approach of this umbrella review provides a valuable knowledge foundation for such future research.

Supporting information

S1 appendix. the s1 appendix contains raw data underpinning grade appraisals and summary results of reviews, epidemiologic studies, and heart rate data..

Additionally, details of excluded articles are included.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252956.s001

- 1. Fancourt D, Warran K, Aughterson H. Evidence Summary for Policy—The role of arts in improving health & wellbeing. United Kingdom: Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport, 2020.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- PubMed/NCBI

- 16. Merriam-Webster. Merriam-Webster’s collegiate dictionary: Merriam-Webster; 2004.

- 17. Higgins JP, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions: John Wiley & Sons; 2019.

- 26. Medicine ACoS. ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013.

- 56. Ekholm O, Bonde LO. Music and Health in Everyday Life in Denmark: Associations Between the Use of Music and Health-Related Outcomes in Adult Danes. Music and Public Health: Springer; 2018. p. 15–31.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Performing arts as a health resource? An umbrella review of the health impacts of music and dance participation

J. Matt McCrary

1 Institute for Music Physiology and Musicians’ Medicine, Hannover University for Music, Drama and Media, Hannover, Germany

2 Prince of Wales Clinical School, Faculty of Medicine, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia

Emma Redding

3 Division of Dance Science, Faculty of Dance, Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance, London, United Kingdom

Eckart Altenmüller

Associated data.

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

An increasing body of evidence notes the health benefits of arts engagement and participation. However, specific health effects and optimal modes and ‘doses’ of arts participation remain unclear, limiting evidence-based recommendations and prescriptions. The performing arts are the most popular form of arts participation, presenting substantial scope for established interest to be leveraged into positive health outcomes. Results of a three-component umbrella review (PROSPERO ID #: CRD42020191991) of relevant systematic reviews (33), epidemiologic studies (9) and descriptive studies (87) demonstrate that performing arts participation is broadly health promoting activity. Beneficial effects of performing arts participation were reported in healthy (non-clinical) children, adolescents, adults, and older adults across 17 health domains (9 supported by moderate-high quality evidence ( GRADE criteria )). Positive health effects were associated with as little as 30 ( acute effects) to 60 minutes ( sustained weekly participation ) of performing arts participation, with drumming and both expressive ( ballroom , social ) and exercise-based ( aerobic dance , Zumba ) modes of dance linked to the broadest health benefits. Links between specific health effects and performing arts modes/doses remain unclear and specific conclusions are limited by a still young and disparate evidence base. Further research is necessary, with this umbrella review providing a critical knowledge foundation.

1. Introduction

Participation and receptive engagement in the arts are increasingly recognized as being health promoting, most notably in policy briefs [ 1 ], a recent World Health Organization-commissioned scoping review [ 2 ], and social prescribing initiatives [ 3 ]. However, the widespread integration of the arts into healthcare and public health practices is limited by a disparate evidence base; the specifics of the most effective arts interventions–namely the mode (specific ‘type’ of art–e.g. ballroom dance, singing) and ‘dose’ (frequency and timing/duration)–for various clinical and public health scenarios are still unclear [ 4 ]. Consequently, formulation of evidence-based arts prescriptions and recommendations is presently difficult [ 4 ].

Participation in the performing arts is the most popular form of arts participation, with up to 40% of EU and US adults participating annually in performing arts activities [ 5 , 6 ]. Within the performing arts, music and dance participation are the two most popular modes of engagement, both involving engagement with music, and proposed to have common evolutionary origins [ 7 – 9 ]. The health effects of music and dance participation were thus considered likely to be both related and broadly studied and are the focus of this review. ‘Performing arts participation’ will be used to refer, jointly, to music and dance participation from this point forward.

Performing arts participation is particularly intriguing in a health context in that it combines creative expression with intrinsic levels of physical exertion associated with many health benefits (e.g. moderate–vigorous intensity cardiovascular demands) [ 10 ]. Both creative arts and physical activity have been independently linked to broad health benefits [ 2 , 11 – 13 ], albeit with a more robust body of evidence supporting the substantial and widespread health impact of physical activity–primary and/or secondary prevention for at least 25 chronic medical conditions and a 9–39% reduction in overall mortality risk [ 12 , 14 , 15 ]. Performing arts and exercise/ physical activity participation are distinguished by a distinctly expressive, rather than exertive, focus of the performing arts; exertion is an intrinsic byproduct, not an objective. Accordingly, the health impact of performing arts participation must be evaluated using frameworks that allow performing arts to remain a primarily expressive activity, but also consider the likely impact of intrinsic physical exertion.

Evidence regarding the full breadth of health impacts of performing arts participation, as well as the modes and doses underpinning these effects, has yet to be compiled, critically appraised and analyzed using a common framework. This umbrella review aims to address this knowledge gap by systematically reviewing and appraising evidence regarding the health effects of performing arts participation, including its impacts on both broad mortality and disease risk and more discrete health-related outcomes, in healthy (non-clinical) adults, adolescents and children. Performing arts participation is hypothesized to have similar health effects as physical activity due to its intrinsic physical exertion, as well as additional effects related to creative expression and engagement with music. Accordingly, a secondary aim of this review is to compile data regarding the intrinsic physical intensity of varying modes of performing arts participation to inform further hypotheses related to relationships between physical intensity and observed effects.

2.1 Review registration

This review was prospectively registered in the PROSPERO registry (ID: CRD42020191991).

2.2 Overview

Following informal literature searches, the authors made an a priori decision that an integrated, three component umbrella review would most effectively address study aims:

- A systematic review of systematic reviews of the health effects of performing arts participation;

- A systematic review of observational studies investigating the impact of performing arts participation on mortality and non-communicable disease risk. NB : initial searches revealed no prior systematic reviews addressing the effects of performing arts participation on mortality and/or non-communicable disease risk .

- A systematic review of studies of heart rate responses to performing arts participation.

Search terms and inclusion/exclusion criteria for each component are described below. All components involved searches of MEDLINE ( all fields , English & human subjects limiter ), EMBASE ( all fields , English & human subjects limiter ), SPORTDiscus ( all fields , English limiter ), and Web of Science ( Arts & Humanities citation index; all fields; English limiter) from inception– 15 June 2020. Abstracts of all database search results were screened, followed by full text review of potentially relevant articles. Hand searches of the reference lists of included articles were also conducted to locate additional relevant articles. The review procedure was conducted by the first author in consultation with the authorship team.

Across all components, ‘music participation’ was defined as singing or playing a musical instrument. ‘Dance participation’ was broadly defined as an activity involving “moving one’s body rhythmically…to music” [ 16 ], with an additional criterion that included articles must identify the investigated activity as ‘dance.’ Articles investigating music and dance participation conducted with an exertive aim (i.e. music or dance session(s) designed to elicit a target heart rate/rating of perceived exertion) were excluded to maintain review focus on performing arts vs. exercise participation. As noted in the introduction, performing arts participation is distinguished from exercise participation by its distinctly expressive, rather than exertive, focus; exertion is an intrinsic byproduct, not an objective.

2.3 Systematic review of systematic reviews of the health benefits of performing arts participation

2.3.1 database search terms.

Database searches were performed using the following search terms and a ‘Reviews’ limiter where available: ((music* OR danc* OR performing art* OR choir OR choral) AND (psycholog* OR biochem* OR immun* OR cognit* OR physical OR health)).

2.3.2 Inclusion/Exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were systematic reviews examining the health effects of active performing arts participation in healthy adults, adolescents or children. A ‘systematic review’ was defined based on Cochrane definitions [ 17 ] as a review conducted using explicit, reproducible methodology and aiming to comprehensively synthesize all available relevant evidence. Exclusion criteria were assessed at the primary study level within relevant reviews: 1) studies with qualitative data only; 2) studies in which performing arts participation was conducted with a target exercise intensity or heart rate–these studies were judged to evaluate exercise, rather than performing arts participation; 3) studies of long-term dance or music interventions in experienced dancers or musicians; 4) single-group observational studies characterizing experienced dancers or musicians.

Systematic reviews including a mixture of primary studies meeting and not meeting inclusion/exclusion criteria were included if:

- Reviews in which study results were quantitatively synthesized (i . e . meta-analysis) –The majority (>50%) of included studies examined active performing arts participation in healthy populations and met no exclusion criteria

- Reviews in which results were narratively synthesized (i . e . descriptive synthesis of quantitative primary study results )–The results of primary studies of active participation in healthy populations meeting no exclusion criteria could be extracted and re-synthesized for the purposes of this review.

2.3.3 Data extraction

Demographic and outcome data were extracted for all included reviews and their underlying primary studies meeting inclusion criteria and no exclusion criteria. For each outcome, the effect of performing arts participation was determined to be ‘positive’, ‘negative’, ‘no effect’, or ‘unclear’. Designations of ‘positive’, ‘negative’ and ‘no effect’ were given in cases where clear links between changes in a parameter and a corresponding positive/negative health effect exist in healthy populations (e.g. shift from pro- to anti-inflammatory tone–positive effect; delayed pubertal onset–negative effect). An ‘unclear’ designation was given in cases where such links between changes in a parameter and health effects do not exist (e.g. acute increase in IL-6).

2.3.4 GRADE quality of evidence appraisal

The GRADE system was favored for this review because of its alignment with review aims and applicability to systematic reviews of systematic reviews [ 17 ]; GRADE is specifically “designed for reviews…that examine alternative management strategies” [ 18 ]. The GRADE system results in an appraisal of the quality of evidence supporting conclusions related to each outcome of interest—very low; low; moderate; high. Specific criteria and appraisal methodology are detailed in the S1 Appendix .

2.3.5 Evidence synthesis

To minimize the biasing effects of overlapping reviews, all outcomes from primary studies included in multiple reviews were only considered once. The lone exception to this was one outcome (flexibility–sit & reach) from one primary study of dance [ 19 ] which was included in multiple meta-analyses [ 20 , 21 ] and thus considered twice. Re-calculation of meta-analyses to remove this duplication was not considered necessary due to consistent effects of dance on flexibility across 4 reviews considering 15 individual studies [ 20 – 23 ]. Common outcomes were first combined and assigned a grouped health effect and GRADE appraisal at the review level. Outcomes and GRADE appraisals were then combined across reviews and assigned a health effect and GRADE appraisal at the umbrella review level. Where appropriate, outcome results were stratified by music/dance participation, sex, age, GRADE appraisal, or instrument/style. Outcomes were categorized by domain–domains used to organize evidence of the health benefits of physical activity were used as an initial framework, with additional domains added as required [ 12 ]. Specific outcomes contained within each category are detailed in S1 Table in S1 Appendix .

2.4. Systematic review of observational studies investigating the impact of performing arts participation on mortality and non-communicable disease risk

Given an absence of known reviews of epidemiologic data regarding performing arts participation and the importance of these data in evaluating health effects, the authors made an a priori decision to conduct a separate systematic review.

2.4.1 Search terms

Databases were searched using the following terms: ((music* OR danc* OR performing art* OR choir OR choral) AND (mortality OR public health OR disease OR risk) AND epidemiology).

2.4.2 Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were observational studies investigating the relationship between performing arts participation and all-cause mortality or non-communicable disease risk and/or non-communicable disease risk factors (i.e. metabolic syndrome) in adults, adolescents or children. No exclusion criteria were defined.

2.4.3 Evidence synthesis, GRADE appraisal and synthesis

Conducted using an adaptation of the procedure detailed in sections 2.3.3–2.3.5, with included primary studies appraised individually and then synthesized at the level of this systematic review.

2.5 Systematic review of studies of heart rate responses to performing arts participation

2.5.1 search terms.

Database searches were performed using the following search terms: ((music* OR danc* OR performing art* OR choir OR choral) AND (load OR intensity OR heart rate)).

2.5.2 Inclusion/Exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were studies reporting average/mean heart rate data collected from at least 1 minute of a representative period of active music or dance participation in any setting. Studies reporting heart rate such that raw heart rate data (beats per minute) could not be extracted were excluded.

2.5.3 Data extraction and appraisal

Demographic and raw heart rate data were extracted from all included studies. Raw heart rate data were calculated where necessary (i.e. from data expressed as % maximum heart rate). Rigorous application of inclusion/exclusion criteria was used in lieu of a formal assessment of evidence quality.

2.5.4 Evidence synthesis

Raw heart rate data were converted to % heart rate maximum (%HR max ) using common estimation methods [ 24 , 25 ]:

%HR max values were then categorized by intensity according to American College of Sports Medicine definitions [ 26 ].

3.1 Systematic review statistics ( Fig 1 )

Specific details regarding excluded reviews/studies are contained in the S1 Appendix .

This umbrella review includes 33 systematic reviews of the health effects of performing arts participation (15 dance; 18 music), encompassing 286 unique primary studies (128 dance; 158 music) and 149 outcomes across 18 health domains. Additionally, 9 observational studies investigating the impact of performing arts participation on mortality and non-communicable disease risk (3 dance, 5 music, 1 dance & music) were included, as well as 87 studies reporting heart rate responses during performing arts participation (71 dance, 16 music). Review articles and observational studies of mortality and non-communicable disease risk are directly referenced in this manuscript (Tables (Tables1 1 and and2); 2 ); the complete list of references, including studies investigating heart rate responses, is contained in the S1 Appendix .

#—domain linked to mechanisms of the health benefits of physical activity (no performing arts data associated with 3 proposed domains/mechanisms–cardiac function; blood coagulation; coronary blood flow) [ 12 , 28 ]. ‘Positive’ and ‘no effect’ results highlighted in green and black, respectively, are supported by moderate and/or high quality evidence.

Age group classifications based on United Nations/World Health Organization definitions: 0–9 years–children; 10–19 years–adolescents; 20–59 –adults; 60+–older adults. ‘Acute’ participation refers to a single session (up to 2.5 hours) of performing arts participation; ‘sustained’ participation refers to 4+ weeks of at least weekly performing arts participation.

#—domain linked to mechanisms of the health benefits of physical activity (no performing arts data associated with 3 proposed domains/mechanisms–cardiac function; blood coagulation; coronary blood flow). [ 12 , 28 ].

3.2 General health effects of active performing arts participation

Positive effects of performing arts participation were reported in 17 of 18 investigated domains–only glucose/insulin outcomes were consistently reported to be unaffected by dance participation (no data related to music participation)( Table 1 ). Positive effects in 9 domains ( auditory; body composition; cognitive; immune function; mental health; physical fitness; physical function; self-reported health/wellbeing; social wellbeing ) were supported by moderate to high quality evidence; results in 4 of these 9 domains ( cognitive; mental health; physical fitness; self-reported health/wellbeing ) included a mixture of positive and neutral/no effects varying by specific outcome ( Table 2 ). Positive effects of performing arts participation were found in 9 of 13 domains (7 of 13 supported by moderate-high quality evidence) associated with the mechanisms of physical activity benefits (Tables (Tables1 1 and and2) 2 ) [ 12 , 28 ]. Raw data underpinning summary results and GRADE appraisals are detailed in the S1 Appendix .

Effects of performing arts participation were investigated in adult populations ( age 20–59 ) across all domains backed by moderate-high quality evidence. Benefits of performing arts participation ( moderate-high quality evidence ) in children ( age 0–9 ) and adolescents ( age 10–19 ) were reported in auditory (music), body composition (dance), cognitive (music), and physical fitness (dance) domains; positive effects of dance on adolescent mental health were also reported. Benefits of performing arts participation were reported in older adults ( age ≥60; moderate-high quality evidence ) across cognitive (dance); immune function (music), mental health (dance), physical fitness (dance), physical function (dance), self-reported health/wellbeing (music & dance), and social functioning (music & dance) domains.

3.3 Modes and ‘doses’ of performing arts participation associated with reported health effects ( Table 2 ; moderate–high quality evidence only)

The effects of dance participation were more broadly supported by higher quality evidence– 34 individual outcomes, with positive effects reported across 7 domains ( body composition; cognitive; mental health; physical fitness; physical function; self-reported health/wellbeing; social functioning ). The effects of music participation were supported by moderate to high quality evidence for 11 individual outcomes, with reported positive effects in 5 domains ( auditory; cognitive; immune function/inflammation; self-reported health/wellbeing; social functioning ). Modes of performing arts participation associated with the broadest positive health effects were: aerobic dance (4 domains ); ballroom dance ( 4 domains ); social dance ( 4 domains ); drumming ( 3 domains ); and Zumba dance ( 3 domains ).

Acute doses ( single session lasting 30–60 minutes ) were sparsely associated with positive effects—hip-hop dance benefited mental health (mood) and music participation (drumming; singing) was associated with positive changes in immune function/inflammation, self-reported health/wellbeing (fatigue), and social functioning (anger). All other results were based on studies of sustained performing arts participation. Significant heterogeneity in frequency and timing of sustained participation was found. Positive health effects were associated with sustained performing arts participation lasting at least 4 weeks, with a minimum of 60 minutes of weekly participation and at least one weekly session. Each individual session in intervention studies lasted 21–120 minutes; the length of individual sessions in cross-sectional studies of performing arts participants vs. non-participants was generally not reported.

3.4 Physical demands of performing arts participation

Heart rate responses to performing arts participation widely varied by style and/or performance setting, with studies of both music and dance participation reporting heart rates classified as very light, light, moderate, and vigorous intensity physical activity (Tables (Tables3 3 and and4). 4 ). Heart rate also varied substantially within the same mode of music/dance participation, with 16 modes (12 music; 4 dance) associated with heart rate responses at two intensity levels, 3 modes (1 music–trumpet; 2 dance–ballet, modern) associated with heart rate responses at three intensity levels, and active video game dancing associated with heart rate responses at all four intensity levels. Raw heart rate data underpinning summary results are detailed in the S1 Appendix .

*—instruments / styles with reported heart rate responses at 2 intensity levels.

**—instruments/styles with reported heart rate responses at 3 intensity levels. See S1 Appendix for source data and citations.

*—dance styles with reported heart rate responses at 2 intensity levels

**—dance styles with reported heart rate responses at 3 intensity levels

***—dance styles with reported heart rate responses at all 4 intensity levels. See S1 Appendix for source data and citations.

4. Discussion

This umbrella review presents an expansive and detailed synthesis and appraisal of evidence demonstrating that performing arts participation is, broadly, health promoting activity, with positive effects across 17 health domains. Moderate-high quality evidence supported positive effects across 9 of these domains, including 7 of 13 domains associated with the health benefits of physical activity. Positive effects were reported in adult populations across all 9 domains, with beneficial effects in children, adolescents, and older adults reported across 4, 5, and 7 domains, respectively. This review also provides preliminary insights into the modes and doses of performing arts participation underpinning observed benefits. Further, heart rate data from 87 additional studies indicate that both music and dance participation intrinsically elicit mean heart rate values corresponding to a range of intensities, including moderate and vigorous.

This review also reveals that the evidence regarding the health impacts of performing arts participation is still in its infancy. Accordingly, reported health benefits and preliminary insights regarding effective performing arts modes and doses must be considered within this context. Moderate-high quality results provide valuable guidance but should not be interpreted as supporting the totality of health benefits or superiority of modes or doses of performing arts participation. Key results of this review are due to greater amounts of high-quality studies of specific modes and doses in particular domains; the overall quality of included evidence is generally low ( 26% (45/173) of outcomes backed by moderate-high quality evidence ) due to a predominance of non-randomized and observational vs. randomized controlled trial study designs. Control and comparison groups varied widely across all study types, including no-intervention/waitlist control groups and exercise (various types), cognitive and/or language training and other art participation (e.g. visual art, drama) comparison groups.

All included studies were conducted without explicit intensity aims, yet 2 of 4 modes of dance participation associated with the broadest health benefits come from exercise, not artistic, traditions: aerobic dance [ 67 ] and Zumba [ 68 ]. Heart rate data ( Table 4 ) unsurprisingly confirm that both modes are associated with moderate to vigorous intensity physical demands as per global physical activity recommendations [ 69 ]. However, two traditionally expressive modes of dance–ballroom and social–were found to have similarly broad benefits, including in physical fitness and function domains. Heart rate data for ballroom and social dancing were sparsely available, precluding discussion of the potential impact of intrinsic physical intensity. Nonetheless, these results suggest that expressive dance participation is similarly health promoting to modes created from an exercise viewpoint. Further obscuring the relationships between physical intensity and observed benefits, drumming was the most broadly health promoting mode of music participation and associated, across various settings, with very light, light, moderate, and vigorous intensity heart rate responses. Additional research is needed to establish the relationships between intrinsic physical intensity and health impacts during performing arts participation.

Both acute and sustained performing arts participation were associated with health benefits, although the bulk of evidence relates to sustained participation. Acute benefits of singing and drumming on inflammation and immune parameters are particularly intriguing; similar short-term effects have been associated with physical activity and linked, with sustained participation, to long-term preventive benefits [ 70 ]. Epidemiologic studies suggest similar links between sustained performing arts participation and a reduced risk of non-communicable diseases and early mortality. However, the quality of these epidemiologic studies is presently low and specifically limited by the use of a range of bespoke survey instruments with unclear psychometric value to quantify the frequency, timing/duration and type of performing arts participation. Future studies using validated instruments for quantifying performing arts participation are needed.

The majority of health benefits backed by moderate-high quality evidence were associated with sustained performing arts participation lasting at least four weeks. Although substantial heterogeneity in results limits conclusions regarding the impact of specific doses of the performing arts, all reported benefits were associated with at least weekly participation. Some benefits were seen with as little as 60 minutes of weekly participation, demonstrating that, like physical activity, significant health benefits can be achieved with modest effort and time commitment [ 14 ]. Physical activity evidence indicates that greater levels of weekly participation are associated with greater health benefits–‘ some is better than none, more is better than less’ [ 14 ]. Substantial further research is required to determine the impact of the frequency and duration of performing arts participation on health benefits, as well as the potential additional impact of the setting (e.g. laboratory, classroom, live performance) of performing arts participation on observed benefits.

In sum, this review presents promising evidence regarding the health benefits of performing arts participation, but is limited by a young and disparate evidence base, as well as additional factors discussed below. Excepting studies of non-communicable disease risk, this umbrella review was limited to English language studies included in systematic reviews of the health effects of performing arts participation. It is thus probable that some primary studies were not considered; their exclusion could impact individual outcome results given the aforementioned infancy of the evidence base. However, it is less likely that individual primary studies would significantly impact the general conclusions of this review, which are based on aggregated moderate-high quality evidence grouped by domain of health impact.

This review is also potentially limited by the conduct of literature searches, data extraction, and evidence appraisal by the first author alone, in consultation with the authorship team, due to resource constraints. Single author search, extraction and appraisal has been demonstrated to increase the incidence of errors [ 71 ], yet these errors have been found to have a minimal impact on review results and conclusions [ 72 ]. To best meet study aims, the authors thus favored a broad, single author search, extraction and appraisal over a more constrained review conducted by multiple authors in duplicate. Additionally, the inclusion of a comprehensive and transparent S1 Appendix detailing all review data and subjective decision-making (i.e. article inclusions, GRADE appraisals) clarifies the basis for specific conclusions and serves as a foundation for discussion and future research.

Finally, while studies of participation-related performing arts injuries were beyond the scope of this review, it should be noted that, similar to exercise participation [ 73 ], the health impact of performing arts activities is not exclusively positive. Participation in performing arts does carry an injury risk, for example caused by overpractice [ 10 ]. These risks are considerably counterbalanced by the broad benefits of performing arts participation demonstrated in this review. However, on an individual level, participation risks must always be managed and weighed against potential benefits.

4.1 Conclusions

Performing arts participation is, broadly, a health promoting activity, with beneficial effects reported across healthy (non-clinical) children, adolescents, adults, and older adults in 17 domains (9 supported by moderate-high quality evidence). Positive health effects were associated with as little as 30 ( acute participation ) or 60 ( sustained weekly participation ) minutes of performing arts participation, with drumming and both expressive ( ballroom , social ) and exercise-based ( aerobic dance , Zumba ) modes of dance linked to the broadest health benefits. However, the evidence base is still very much in its infancy. Further research is necessary to optimize modes and doses of performing arts participation towards specific health effects, as well as clarify relationships between intrinsic physical intensity and observed benefits. The broad yet rigorous approach of this umbrella review provides a valuable knowledge foundation for such future research.

Supporting information

S1 appendix.

Additionally, details of excluded articles are included.

Funding Statement

JMM was supported by a Postdoctoral Fellowship from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Data Availability

- PLoS One. 2021; 16(6): e0252956.

Decision Letter 0

PONE-D-20-39389

Dear Dr. McCrary,

Thank you for submitting your manuscript to PLOS ONE. After careful consideration, we feel that it has merit but does not fully meet PLOS ONE’s publication criteria as it currently stands. Therefore, we invite you to submit a revised version of the manuscript that addresses the points raised during the review process.

As you can see, both reviewers are generally supportive of this work, however several concerns they raise must be concerned. I felt like this was somewhere between a major and minor revision, but in order to give you more time to complete the revisions, I've decided to issue this as a major revision (but in reality, I am hoping it won't take that long to address the reviewers' comments and resubmit).

Please submit your revised manuscript by May 16 2021 11:59PM. If you will need more time than this to complete your revisions, please reply to this message or contact the journal office at gro.solp@enosolp . When you're ready to submit your revision, log on to https://www.editorialmanager.com/pone/ and select the 'Submissions Needing Revision' folder to locate your manuscript file.

Please include the following items when submitting your revised manuscript:

- A rebuttal letter that responds to each point raised by the academic editor and reviewer(s). You should upload this letter as a separate file labeled 'Response to Reviewers'.

- A marked-up copy of your manuscript that highlights changes made to the original version. You should upload this as a separate file labeled 'Revised Manuscript with Track Changes'.

- An unmarked version of your revised paper without tracked changes. You should upload this as a separate file labeled 'Manuscript'.

If you would like to make changes to your financial disclosure, please include your updated statement in your cover letter. Guidelines for resubmitting your figure files are available below the reviewer comments at the end of this letter.

If applicable, we recommend that you deposit your laboratory protocols in protocols.io to enhance the reproducibility of your results. Protocols.io assigns your protocol its own identifier (DOI) so that it can be cited independently in the future. For instructions see: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/submission-guidelines#loc-laboratory-protocols . Additionally, PLOS ONE offers an option for publishing peer-reviewed Lab Protocol articles, which describe protocols hosted on protocols.io. Read more information on sharing protocols at https://plos.org/protocols?utm_medium=editorial-email&utm_source=authorletters&utm_campaign=protocols .

We look forward to receiving your revised manuscript.

Kind regards,

Emily S. Cross

Academic Editor

Journal requirements:

When submitting your revision, we need you to address these additional requirements.

1. Please ensure that your manuscript meets PLOS ONE's style requirements, including those for file naming. The PLOS ONE style templates can be found at

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/file?id=wjVg/PLOSOne_formatting_sample_main_body.pdf and

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/file?id=ba62/PLOSOne_formatting_sample_title_authors_affiliations.pdf

2. In line with PLOS' guidelines on systematic reviews ( https://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/submission-guidelines#loc-systematic-reviews-and-meta-analyses ), please update your PRISMA flowchart to provide detailed reasons for the exclusion of manuscripts at each stage of analysis.