Psychology Discussion

How attitude influences our behaviour.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

How Attitude Influences our Behaviour – Answered!

Attitudes are said to influence our behaviour. But many times it may not be true. There are arguments on both sides. Some people say that our attitudes determine our behaviour. It is true also.

For example, if a person has a negative attitude towards some other person, he may not express it directly, rather he may not show any interest to join him in a party, or to share a common platform- with that person.

On the other hand, there are opinions which state that there is no valid proof to believe about the influence of attitude on behaviour.

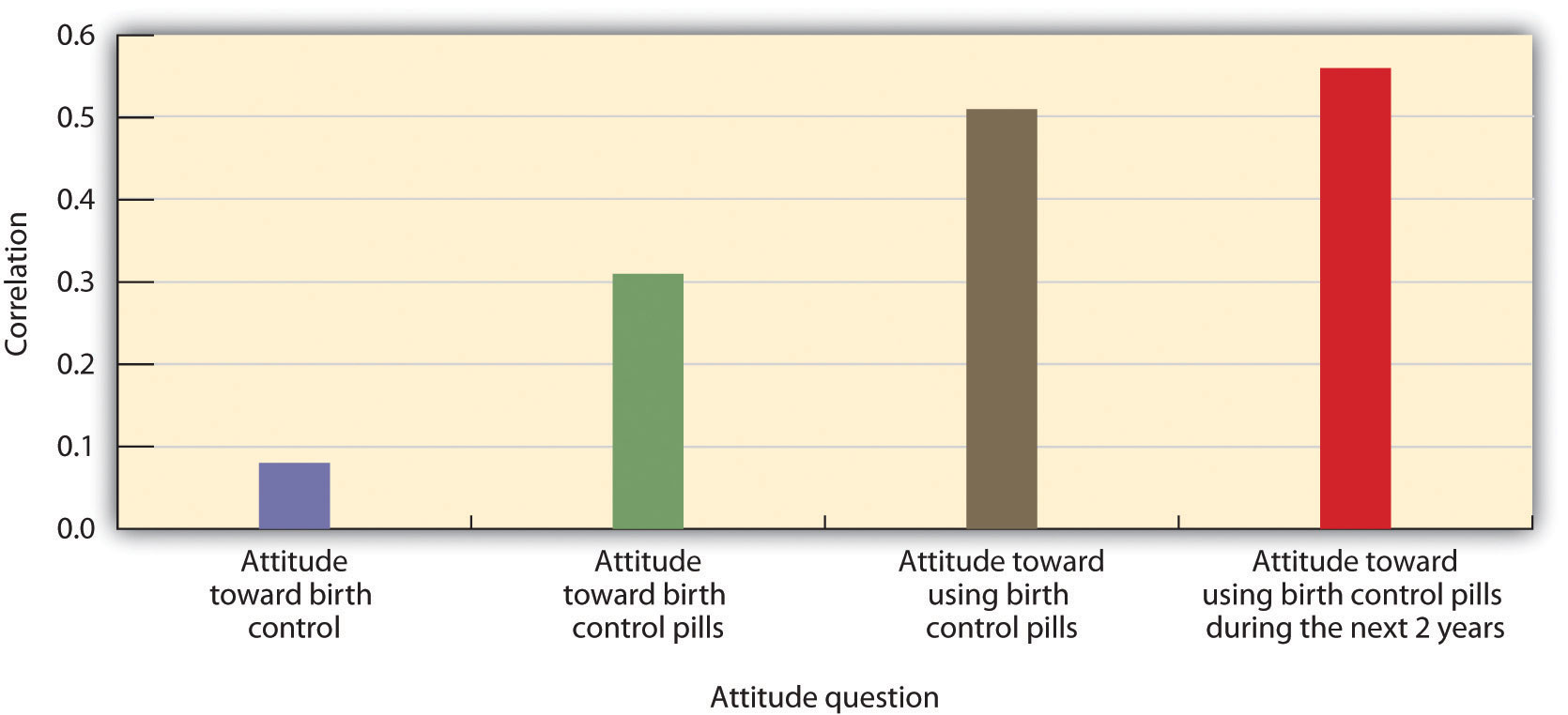

An important contribution to the study of behavioural prediction from attitudes has been made by Martin Fishbein (1967, 1975). He argues that there is no good reason to believe that an overall measure of attitude toward an object will necessarily predict a specific behaviour.

According to him attitude is a hypothetical concept abstracted from the totality of a person’s feelings, beliefs and behavioural intentions regarding an object. Thus an isolated specific behaviour may be unrelated, or even negatively related to the overall attitude.

Fishbein maintains that, in order to predict a specific behaviour, we should not focus on people’s overall attitude toward the object of that behaviour, but on their attitude toward the behaviour.

Attitude about specific behaviour depends on such factors as evaluations of the likely consequences of the behaviour and social norms concerning the behaviour. For example, a person may have a positive attitude for inter-caste marriage, but because of social norms he may show negative behaviour like disapproving it.

At times we may not like to have certain attitudes. But such a tendency may lead to incompatibility among people in the society who are living together. At that time we try to develop attitudes according to situations.

This has been explained by a famous theory called ‘Balance theory’ (Heider, 1958). The basic tenet of this theory is that there is a tendency to maintain or restore balance in one’s attitude structures. Because unbalanced attitude structure leads to uncomfortable and unpleasant feelings.

Although the influence of attitudes on behaviour is not clearly discernible; two theories viz., (1) Cognitive dissonance and (2) Self- fulfilling prophecy help us to understand the direction of attitudinal influences.

Cognitive dissonance refers to the feeling of inconsistency in feelings, beliefs and behaviour (the three components of attitudes).

This feeling makes people uncomfortable. So they get motivated to rectify the situation by modifying their behaviours that cause dissonance or disagreement. For example, a nurse may have a negative feeling to work in a Tuberculosis ward with a belief that her health will be affected. But she will not show it directly in her behaviour, but try to get a change from that ward itself or remains absent from her duties.

Self fulfilling prophecy is the process by which we try to convert our attitudes, beliefs and expectations-into reality. If we predict that something is going to happen, we will try very hard to make it happen. For example, if we feel that we are competent, we will undertake challenging tasks.

A nurse who has a negative attitude to work in major operation theatre may take it as a challenge and develop skills to work there. Consequently, we gain experience and skills that make us more competent, so that we accomplish even more. However, if we have negative attitudes towards ourselves, we will not provide ourselves with the chance to become competent.

In this way road between behaviour and attitudes is a two-way street. In some situations our behaviour is influenced by our attitudes and some other times our behaviour will determine our attitudes. For example, when a person is asked whether he likes music, he will examine his own behaviour to decide his attitude position. “I must like it, because I am regularly listening to it” or “I must not like it, I rarely listen music”. Here, his attitudes are determined on the basis of his behaviour.

In this way the regulation of balance in society, cognitive dissonance, self fulfilling prophecies are the factors which influence our behaviours and attitudes.

Related Articles:

- 5 Important Determinants of Attitude

- Attitude: Compilation of Essays on Attitude | Human Behaviour | Psychology

- Essay on Attitude: Top 8 Essays | Human Behaviour | Psychology

- Measurement of Attitude: How to Measure Social Attitude?| Psychology

Why Does Our Behavior Affect Our Attitudes?

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Human behavior is an element of inborn traits and socialization traits; when human beings interact, they shape each other’s behavior, values, norms, and personal perception.

According to psychologists, behavior can be defined simply as an expression of one’s attitude, perception, values, and believe to an act; human behavior is molded by internal feelings, thoughts, and beliefs; what come-outs or the acts that human call behaviors are the end result (Freud & Strachey, 1976). Psychologists have accepted that there is a close link between human behavior and attitude; this paper analyzes why behavior influences attitude.

Human behaviors and attitude

An act can be said to have become a behavior when it a person has repeatedly acted in a certain direction; according to the literature of human behavior, it is personal but shaped by the external environment that someone is operating. It is appreciated that human beings develop a certain mode of behavior from factors arising from socialization right from childhood and these follow him to adulthood; however attitude follow behavior in some circumstances . Our values, beliefs and morals are largely influenced by the society we live in, culture, and hereditary factors. Some situations where behavior can shape our attitudes they include:

Self presentation or creation of a self image

In this case, a person may be confronted with as situation that he is expected to adopt a certain behaviors that he thought that the behaviors belonged to a certain class of people. He may be role-playing to seek conformity with a certain community or class of people. When in the role-playing, he may have his attitudes towards something that he has seen it differently changed.

For example, the case of person who feels that the poor are poor because they do not think on ways they can use to gain wealth, then the person may be shooting a certain film in the slums where he interacts with the people and assumes the role of being one of them to get information and shot his movie.

At the end of the stay with the slums people, the person learns that life is difficult and the people lack the basics that they need to think and be creative, as he had anticipated they needed to do. Such a person is more likely to change his attitude toward the poor and learn how to respect them.

Cognitive dissonance

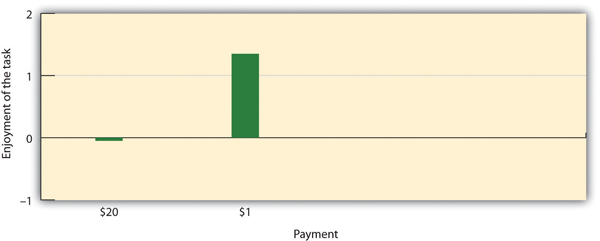

It is not always that people advocate for what they have positive attitude; they may be the advocators of something they rarely can believe or even do; however with time they are conditioning their minds towards the thing and they will eventually find themselves having a changed attitude.

Take the example of a person who feels that his employer is not acting well and is a nuisance, when such a person is chosen to teach new entrants on the company’s core values, ethics, and its human resources policies. He will offer the positive side of the story and in the end; he or she will have his attitude changed because of the positive talks engaged.

Dissonance after decision

For deviant people in the society, some consequences are likely to follow them; from the experience they get from the consequences of their deviant behavior, they may be forced to change their attitude.

This mostly happens with offenders; the behavior that gets someone to jail may have resulted from inner perception or belief, when such a behaviors is punished, the person may change the behavior for the good. On the other hand, if someone was doing good anticipating some gains, but instead of gains, he got some setbacks, he is more likely to have a negative attitude toward the good behavior.

For example, in work places, hard work is advocated and employers promise to compensate, reward and recognize those people who have an outstanding results; hard work is a behavior. In the case that after successful satisfaction of the employer an employee is not rewarded or in worse situation someone who had not done as much gets credit, then the hard-worker is more likely to develop a negative attitude towards working hard as well as his employer.

Self-perception

After being engaged in a certain behavior that someone thinks is good, what follow is a self-reflection of the decision as well as the behavior and the results of our actions. In the case that the act injured someone who had not been anticipated or un-justified, someone feels a sense of guilt that can change his attitude towards the act (Harold & Beigel, 1990).

For example, a teacher who supports punishment of students may change his perception after punishing a student then the student faints. The teacher may feel responsible of the act and his attitude towards canning completely changed. When attitude follows behavior, a person must have a reflection of the actions undertaken and if there is cognitive dissonance, the change of attitude is likely to follow.

Harold, R., & Beigel, A. (1990). Understanding of human behavior for effective police work . New York: San Diego.

Freud, S., & Strachey, J. (1976). The complete psychological work of Sigmund Freud (standard edition) vol. (1-24 ).New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

- Cognitive Dissonance and Reduction Strategies

- Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Games

- Cognitive Dissonance Definition

- History and Causes of the Sexual Deviants in People

- Sex and the city. Media Analysis

- The Psychoanalytic Approach to Personality

- Deviant behavior: Prostitution

- Causes of Different Personalities and Character Traits

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, September 20). Why Does Our Behavior Affect Our Attitudes? https://ivypanda.com/essays/why-does-our-behavior-affect-our-attitudes/

"Why Does Our Behavior Affect Our Attitudes?" IvyPanda , 20 Sept. 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/why-does-our-behavior-affect-our-attitudes/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'Why Does Our Behavior Affect Our Attitudes'. 20 September.

IvyPanda . 2018. "Why Does Our Behavior Affect Our Attitudes?" September 20, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/why-does-our-behavior-affect-our-attitudes/.

1. IvyPanda . "Why Does Our Behavior Affect Our Attitudes?" September 20, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/why-does-our-behavior-affect-our-attitudes/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Why Does Our Behavior Affect Our Attitudes?" September 20, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/why-does-our-behavior-affect-our-attitudes/.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Write for us

- Sex Educations

- Social Exchange Theory

- Self-Determination

- Sexual Assault

- Emotional Contagion

Understanding Attitudes and Behavior: Exploring the Psychology behind Human Actions

Abstract: This comprehensive blog post explores the intricate relationship between attitudes and behavior in psychology. It delves into the nature of attitudes, including their definition, components, formation, and structure. The influence of internal factors, such as beliefs and values, as well as external factors like social norms and cultural influences, are examined. The blog post discusses theories and models that explain attitudes and behavior, including the Theory of Planned Behavior, Cognitive Dissonance Theory, Social Learning Theory, and Elaboration Likelihood Model. Real-life applications of attitudes and behavior are explored in various contexts, such as interpersonal relationships, the workplace, health behavior, and social change. The abstract concludes by emphasizing the importance of understanding attitudes and behavior for personal growth, improved relationships, and positive societal impact.

Attitudes and Behavior

Table of Contents

Attitudes and behavior are fundamental aspects of human psychology that shape the way we perceive, interpret, and respond to the world around us. In this blog post, we will explore the intricacies of attitudes and behavior, shedding light on the factors that influence them and the significance they hold in our lives.

The Nature of Attitudes

Components of attitudes.

Attitudes are evaluative judgments formed towards objects, people, or ideas. They consist of three main components: cognitive, affective, and behavioral.

- Cognitive component: This component reflects the beliefs and thoughts associated with the attitude. It involves the individual’s knowledge and understanding of the object of their attitude. For example, someone with a positive attitude towards recycling may believe that it helps protect the environment.

- Affective component: The affective component of attitudes involves emotions and feelings associated with the attitude. It represents the individual’s emotional response or evaluation of the object of their attitude. For instance, a person with a negative attitude towards spiders may experience fear or disgust when encountering one.

- Behavioral component: The behavioral component of attitudes reflects the behavioral intentions and actions resulting from the attitude. It pertains to how individuals are likely to behave towards the object of their attitude. For example, someone with a pro-environmental attitude may actively participate in recycling programs or reduce their energy consumption.

Formation and Structure of Attitudes

Attitudes are formed through a variety of processes, including social learning and direct experience. They can be structured hierarchically, with more influential attitudes at the core.

- Formation of Attitudes: Attitudes can develop through various means, such as observation, learning from others, and personal experiences. For instance, an individual may acquire a positive attitude towards volunteering after witnessing the positive impact it has on others.

- Hierarchy of Attitudes: Attitudes can be organized hierarchically, with central attitudes being more fundamental and resistant to change. Central attitudes are closely tied to an individual’s core values and beliefs. Peripheral attitudes are more malleable and less central to one’s identity. They may change more readily based on situational factors.

- Explicit and Implicit Attitudes: Attitudes can be explicit (conscious) or implicit (unconscious). Explicit attitudes are those that individuals are aware of and can readily report. Implicit attitudes are automatic and can influence behavior without conscious awareness. For example, someone may consciously hold egalitarian attitudes but unconsciously display implicit biases towards certain groups.

Attitude-Behavior Consistency

Attitude-behavior consistency refers to the alignment between attitudes and subsequent behavior. Several factors influence the strength of this relationship.

- Factors Influencing Consistency: The strength of the relationship between attitudes and behavior can vary. Factors such as the strength and importance of the attitude, personal relevance, and previous experiences can increase the likelihood of consistent behavior. For example, a person with a strong anti-smoking attitude is more likely to engage in behavior consistent with that attitude.

- Situational Constraints: Despite having a particular attitude, individuals may not always behave consistently due to situational constraints. Factors such as social norms, external pressures, or situational demands can limit the expression of attitudes in behavior. For instance, a person who strongly supports environmental conservation may not always engage in eco-friendly behavior if they are in a time-constrained situation.

- Attitude-Behavior Inconsistencies: In some cases, individuals may display inconsistencies between their attitudes and behavior. This can occur due to various factors, including cognitive dissonance (the discomfort caused by conflicting cognitions) or external influences. Inconsistencies may lead to attitude change or rationalization of behavior.

Attitude Change and Persuasion

Attitudes can change through persuasive communication and social influence. Several theories explain how attitude change occurs.

- Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM): The ELM explains how attitudes are changed through central and peripheral routes of persuasion. The central route involves deep processing and critical evaluation of persuasive messages. Individuals carefully consider the arguments and information presented before forming or changing their attitudes. The peripheral route, on the other hand, relies on superficial cues and heuristics to form or change attitudes, such as the credibility of the source or the emotional appeal of the message.

- Factors Influencing Attitude Change: Several factors can influence the effectiveness of persuasive communication in changing attitudes. Source credibility, message content, receiver characteristics, and the context of communication all play a role. A credible and trustworthy source, persuasive and relevant message content, and the receiver’s motivation and ability to process the information can enhance attitude change. For example, a well-respected expert delivering a persuasive message supported by strong evidence is more likely to influence attitude change.

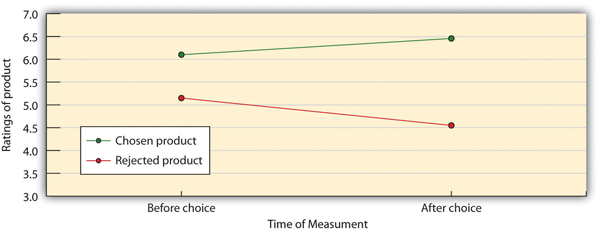

- Cognitive Dissonance Theory: Cognitive dissonance theory explains how inconsistencies between attitudes and behavior can lead to attitude change. When individuals experience cognitive dissonance—the discomfort caused by holding conflicting beliefs or engaging in behaviors that contradict their attitudes—they are motivated to reduce the dissonance. This can be done by changing the attitude, changing the behavior, or rationalizing the inconsistency. For instance, a person who smokes but holds a negative attitude towards smoking may either quit smoking or rationalize their behavior to reduce cognitive dissonance.

Attitudes are multidimensional constructs consisting of cognitive, affective, and behavioral components. They are formed through various processes and can be influenced by factors such as social learning and direct experience. Attitude-behavior consistency can be influenced by the strength of attitudes, personal relevance, and situational constraints. Attitude change can occur through persuasive communication and social influence, and theories such as the Elaboration Likelihood Model and Cognitive Dissonance Theory help explain these processes. Understanding the nature of attitudes and their relationship with behavior provides valuable insights into human psychology and societal dynamics.

Influential Factors in Attitudes and Behavior

Social influences on attitudes.

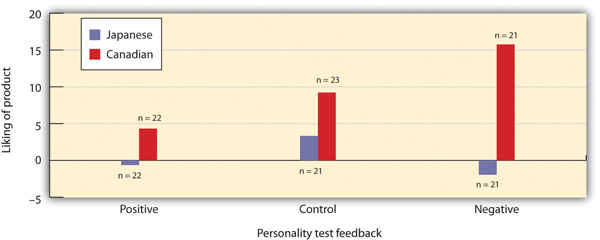

- Social norms and cultural values shape the development of attitudes: Social norms are unwritten rules and expectations that guide behavior within a specific social group or culture. Cultural values, on the other hand, are shared beliefs and ideals upheld by a society. Both social norms and cultural values influence the formation and expression of attitudes.

- Social norms: They provide a framework for what is considered acceptable or appropriate behavior in a given social context. Adhering to social norms often leads to the adoption of corresponding attitudes.

- Cultural values: Cultural values shape individuals’ beliefs and attitudes by instilling certain principles and priorities. Attitudes are often aligned with the prevailing cultural values within a society.

- Conformity and social comparison influence attitudes and behavior: Conformity refers to the tendency to adjust one’s attitudes and behavior to match those of a particular group or social norm. Social comparison involves evaluating one’s attitudes and behavior by comparing oneself to others.

- Conformity: Individuals may conform to group attitudes to gain social acceptance, avoid conflict, or seek approval. This can result in the adoption of attitudes that may not align with their personal beliefs.

- Social comparison: People often evaluate their attitudes and behavior by comparing themselves to others. This comparison can influence the adoption or modification of attitudes to align with those of others.

- Group membership and social identity impact attitude formation and expression: Group membership and social identity play a significant role in shaping attitudes. People tend to identify with specific social groups and develop attitudes consistent with their group’s values and beliefs.

- Group membership: Belonging to a particular social group can lead to the adoption of group-specific attitudes. The desire for group cohesion and a sense of belonging motivates individuals to align their attitudes with those of their group.

- Social identity: Social identity refers to the aspects of an individual’s self-concept that derive from group membership. Attitudes associated with social identity are often strong and influence behavior to maintain group cohesion and positive self-image.

- Social influence can lead to both positive and negative changes in attitudes and behavior: The influence of others can lead to changes in attitudes and subsequent behavior, both in positive and negative ways.

- Positive social influence: Positive role models, mentors, and supportive social networks can promote positive attitudes and behavior. Observing and interacting with individuals who exhibit desirable attitudes and behaviors can inspire personal growth and positive change.

- Negative social influence: Negative social influences, such as peer pressure, can lead to the adoption of harmful attitudes and behaviors. Conforming to negative social norms or engaging in deviant behavior may result from the desire to fit in or gain acceptance.

Cognitive Factors in Attitudes and Behavior

- Cognitive dissonance theory highlights the role of inconsistencies in shaping attitudes and behavior: Cognitive dissonance refers to the discomfort that arises from holding conflicting cognitions (thoughts, beliefs, attitudes). People strive to reduce cognitive dissonance by aligning their attitudes and behavior.

- Inconsistencies: When individuals encounter inconsistencies between their attitudes and behavior or between multiple attitudes, they experience cognitive dissonance. This discomfort motivates them to either change their attitudes or modify their behavior to restore consistency.

- Cognitive biases, such as confirmation bias and availability heuristic, influence attitudes: Cognitive biases are systematic errors in thinking that affect judgment and decision-making processes. These biases can influence the formation and maintenance of attitudes.

- Confirmation bias: This bias involves seeking and interpreting information in a way that confirms preexisting attitudes or beliefs while disregarding contradictory evidence. Confirmation bias reinforces existing attitudes and inhibits attitude change.

- Availability heuristic: The availability heuristic is a mental shortcut in which judgments are based on the ease Apologies for the cutoff.

- Here’s the continuation: with which examples or instances come to mind. The availability heuristic can influence attitudes by giving greater weight to easily recalled information, even if it is not representative or accurate.

- Belief perseverance explains the tendency to maintain attitudes despite contradictory evidence: Belief perseverance is the cognitive bias that leads individuals to cling to their initial attitudes or beliefs even when presented with evidence that contradicts them.

- Persistence of attitudes: When confronted with contradictory information, individuals may engage in selective attention, interpretation, and memory to maintain their existing attitudes. This bias prevents attitude change and reinforces initial beliefs.

- Motivated reasoning: People often engage in motivated reasoning, selectively accepting or interpreting information in a way that supports their existing attitudes and beliefs. This bias helps maintain cognitive consistency but can hinder objective evaluation.

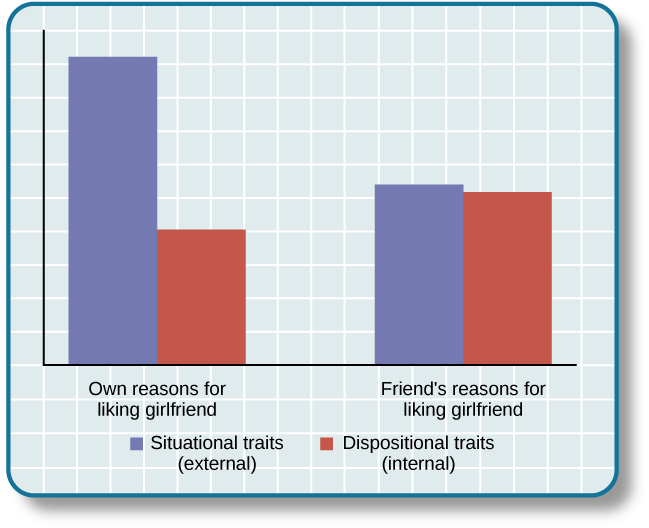

- Implicit biases and stereotypes affect behavior without conscious awareness: Implicit biases are unconscious attitudes or stereotypes that influence behavior without individuals being consciously aware of them. These biases can shape behavior in subtle and unintentional ways.

- Implicit biases: Implicit biases can develop through socialization and exposure to cultural messages. They influence behavior by activating automatic associations and affecting judgments, decisions, and actions.

- Stereotypes: Stereotypes are widely held beliefs or expectations about certain groups of people. These stereotypes can shape attitudes and behavior, leading to prejudiced actions or discrimination even without conscious intent.

Emotional Influences on Attitudes and Behavior

- Emotions play a crucial role in attitude formation and behavioral responses: Emotions are powerful internal experiences that influence attitudes and behavior by shaping perceptions, evaluations, and decision-making processes.

- Emotional valence: Positive or negative emotional experiences can influence the formation of attitudes. Pleasant emotions tend to promote positive attitudes, while unpleasant emotions can lead to negative attitudes.

- Emotional priming: Emotions can prime certain attitudes by activating associated memories, thoughts, and physiological responses. For example, feeling happy may prime positive attitudes, leading to more favorable evaluations.

- Emotionally charged events can shape attitudes and trigger corresponding behavior: Emotionally charged events or experiences can leave a lasting impact on attitudes and elicit behavioral responses.

- Emotional experiences: Strong emotional experiences, such as trauma or intense positive events, can shape attitudes and influence subsequent behavior. These events can create emotional associations with specific objects, people, or ideas.

- Emotional contagion: Emotions can be contagious, spreading from one person to another through social interactions. Observing others’ emotional expressions can trigger similar emotional states, which can influence attitudes and behavior.

- Emotional intelligence and emotional regulation influence attitudes and behavior: Emotional intelligence refers to the ability to understand and manage one’s own emotions and empathize with others. Effective emotional regulation contributes to adaptive attitudes and behavior.

- Emotional intelligence: Individuals with high emotional intelligence are more adept at recognizing and understanding their own emotions and the emotions of others. This awareness can facilitate the formation of empathetic attitudes and pro-social behavior.

- Emotional regulation: The ability to regulate and control emotions is crucial for managing attitudes and behavior. Effective emotional regulation strategies, such as reappraisal or distraction, can help individuals respond to situations in a more adaptive manner.

- Emotional contagion can lead to the adoption of attitudes and behaviors through social interactions: Emotional contagion is the phenomenon where emotions spread from one person to another, leading to the adoption of similar attitudes and behaviors.

- Mimicry and empathy: When individuals observe others’ emotional expressions, they may unconsciously mimic those expressions, leading to shared emotional experiences. Empathy also plays a role, as individuals can adopt attitudes and behaviors that align with the emotions of others.

- Social dynamics: Emotional contagion occurs within social groups and can influence the overall Apologies for the cutoff.

- Here’s the continuation: emotional climate and collective attitudes and behaviors. It can occur through direct face-to-face interactions, as well as through indirect means such as social media or mass media.

Environmental Factors and Attitudes

- Physical environment and spatial contexts can influence attitudes and behavior: The physical environment and spatial contexts in which individuals live and interact can shape their attitudes and subsequent behavior.

- Environmental cues: Environmental cues, such as cleanliness, noise levels, or natural elements, can impact mood and subsequently influence attitudes and behavior. For example, a clean and organized environment may promote positive attitudes and pro-social behavior.

- Architectural design: The design and layout of spaces can influence attitudes and behavior. Factors such as open spaces, natural lighting, and accessibility can affect individuals’ perceptions and attitudes.

- Socioeconomic factors, such as income and education, can shape attitudes: Socioeconomic status (SES), including factors like income, education, and occupation, can influence attitudes and behavior.

- Income and attitudes: Individuals with higher income levels may have different attitudes compared to those with lower income levels. Attitudes towards wealth, social issues, and economic policies can be influenced by socioeconomic factors.

- Education and attitudes: Education plays a role in shaping attitudes by providing individuals with knowledge, critical thinking skills, and exposure to different perspectives. Attitudes towards social issues, politics, and cultural values can be influenced by educational experiences.

- Cultural and societal norms impact attitudes and behavioral patterns: Cultural and societal norms, which vary across different communities and societies, shape individuals’ attitudes and behavior.

- Cultural norms: Cultural norms define what is considered acceptable or appropriate behavior within a particular culture. They influence attitudes related to topics such as family values, gender roles, and social interactions.

- Societal norms: Societal norms encompass broader norms and expectations that exist within a society. They can influence attitudes towards topics such as social justice, equality, and moral values.

- Media and advertising play a significant role in shaping attitudes and behavior: Media, including television, movies, social media, and advertising, has a powerful influence on attitudes and behavior.

- Media portrayal: The way individuals and groups are portrayed in media can shape attitudes and perceptions. Media can reinforce or challenge stereotypes, influence opinions on social issues, and shape consumer behavior.

- Advertising effects: Advertising aims to influence attitudes and behavior by presenting products, ideas, or values in a persuasive manner. It can shape attitudes towards brands, influence purchasing decisions, and promote certain behaviors.

Attitudes and behavior are influenced by a variety of factors. Social influences, such as social norms and conformity, cognitive factors like cognitive biases and belief perseverance, emotional influences, including emotional experiences and contagion, and environmental factors, such as the physical environment and media exposure, all play a role in shaping attitudes and subsequent behavior. Understanding these influential factors provides insights into how attitudes are formed and how they impact our actions. By examining these factors, we can gain a better understanding of human psychology and promote positive attitudes and behaviors in ourselves and others.

Theories and Models Explaining Attitudes and Behavior

Theory of planned behavior.

- The Theory of Planned Behavior: (TPB) is a psychological model that seeks to explain the relationship between attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control in influencing behavior.

- Attitudes: Attitudes refer to a person’s positive or negative evaluations of a particular behavior. According to TPB, positive attitudes towards a behavior increase the likelihood of engaging in that behavior, while negative attitudes decrease the likelihood.

- Subjective Norms: Subjective norms involve the perceived social pressure or expectations to perform a behavior. These norms are influenced by the individual’s beliefs about what others think they should do. TPB posits that the stronger the subjective norms favoring a behavior, the more likely an individual is to engage in it.

- Perceived Behavioral Control: Perceived behavioral control refers to an individual’s perception of their ability to perform a behavior. It takes into account factors such as skills, resources, and situational constraints. TPB suggests that individuals with higher perceived control are more likely to engage in a behavior.

- Behavioral Intentions: Behavioral intentions represent a person’s motivation and readiness to perform a specific behavior. They are influenced by attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. TPB asserts that strong behavioral intentions increase the likelihood of actual behavior.

- Actual Behavior: TPB emphasizes that behavioral intentions are strong predictors of actual behavior. However, other factors such as external constraints or unforeseen circumstances may also impact the translation of intentions into behavior.

- Applications of TPB: The Theory of Planned Behavior has been widely applied in various fields, including health psychology, consumer behavior, and environmental psychology. It has helped researchers and practitioners understand and predict behaviors such as exercise, smoking cessation, purchasing decisions, and pro-environmental actions.

Cognitive Dissonance Theory

- Cognitive Dissonance Theory: Cognitive Dissonance Theory, developed by Leon Festinger, posits that individuals strive for consistency between their attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors. When inconsistencies arise, it creates psychological discomfort called cognitive dissonance.

- Attitude-Behavior Inconsistency: Cognitive dissonance occurs when there is a mismatch between an individual’s attitudes and their behavior. For example, if someone holds a negative attitude towards smoking but continues to smoke, it creates a state of cognitive dissonance.

- Dissonance Reduction: To reduce cognitive dissonance, individuals may modify their attitudes, beliefs, or behaviors. They may either change their attitude to align with their behavior, change their behavior to align with their attitude, or rationalize the inconsistency through selective exposure to information.

- Selective Exposure: Selective exposure is a cognitive process where individuals seek information that supports their existing attitudes and avoids information that contradicts them. It helps individuals reduce dissonance by maintaining consistency in their belief system.

- Justification and Rationalization: Cognitive dissonance theory suggests that individuals tend to justify or rationalize their behavior to minimize the discomfort caused by inconsistency. This may involve finding alternative explanations or minimizing the perceived negative consequences of their actions.

- Impact on Attitude Change: Cognitive dissonance theory highlights that changing behaviors can lead to changes in attitudes. By engaging in actions that are incongruent with existing attitudes, individuals may adjust their attitudes to restore consistency.

- Real-Life Applications: Cognitive dissonance theory has been applied in various contexts, such as persuasive communication, decision-making, and attitude change. It has helped marketers influence consumer behavior, policymakers shape public opinion, and individuals resolve conflicts between their beliefs and actions.

Social Learning Theory

- Observational Learning: According to Social Learning Theory, individuals learn by observing the behavior of others and the consequences that follow. They imitate or model the observed behavior if they perceive it as rewarding or if the model is respected and influential.

- Vicarious Reinforcement and Punishment: Social Learning Theory suggests that individuals are motivated to adopt or reject certain attitudes and behaviors based on the consequences experienced by others. If they witness positive outcomes (reinforcement) resulting from a behavior, they are more likely to adopt it. Conversely, if they observe negative outcomes (punishment), they are more likely to avoid that behavior.

- Modeling and Identification: Role models play a significant role in social learning. Individuals are more likely to imitate behaviors and adopt attitudes of those they identify with or admire. This identification can be based on similarities in characteristics, values, or aspirations.

- Self-Efficacy: Social Learning Theory emphasizes the importance of self-efficacy, which refers to an individual’s belief in their ability to perform a behavior. Higher self-efficacy leads to increased motivation, effort, and persistence in adopting attitudes and behaviors.

- Reinforcement and Punishment: In addition to observational learning, Social Learning Theory recognizes the influence of direct reinforcement and punishment on attitudes and behavior. Positive reinforcement (rewards) strengthens desired behaviors, while punishment weakens undesired behaviors.

- Applications of Social Learning Theory: Social Learning Theory has found applications in various domains, including education, therapy, and behavior modification programs. It has helped shape interventions aimed at promoting positive attitudes, reducing aggressive behavior, and enhancing social skills.

Elaboration Likelihood Model

- The Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM) explains how attitudes are changed through two routes of persuasion: the central route and the peripheral route.

- Central Route: The central route involves a deep level of cognitive processing. When individuals are motivated and have the ability to process information critically, they carefully evaluate the content of persuasive messages. They focus on the logical arguments, evidence, and facts presented to form or change their attitudes.

- Peripheral Route: The peripheral route relies on superficial cues and heuristics rather than detailed analysis. Individuals may be influenced by factors such as the attractiveness of the communicator, the use of emotional appeals, or the consensus of others without deeply scrutinizing the message content.

- Motivation: According to the ELM, motivation plays a crucial role in determining the route of persuasion. When individuals have a personal involvement or vested interest in the topic, they are more likely to engage in central processing. If the topic is of low relevance or they lack motivation, they are more susceptible to peripheral cues.

- Ability: The ability to process information also affects the route taken. Factors such as cognitive capacity, time constraints, and distractions can hinder the ability to engage in central processing. When individuals lack the resources or mental effort required for central processing, they rely on peripheral cues.

- Contextual Factors: The Elaboration Likelihood Model recognizes that contextual factors, such as the expertise of the communicator, message clarity, and situational distractions, can influence the effectiveness of persuasive communication.

- Practical Implications: Understanding the central and peripheral routes of persuasion can help communicators tailor their messages accordingly. Depending on the audience’s motivation and ability to process information, persuasive strategies can be designed to emphasize logical arguments or peripheral cues to maximize attitude change.

Theories and models in psychology provide valuable frameworks for understanding attitudes and behavior. The Theory of Planned Behavior explains the role of attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control in predicting behavior. Cognitive Dissonance Theory explores the discomfort caused by attitude-behavior inconsistencies and how individuals strive for consistency.

Attitudes and Behavior in Everyday Life

Attitudes in interpersonal relationships.

- Attitudes shape interpersonal interactions and the formation of relationships: Attitudes, including beliefs, values, and preferences, significantly impact how individuals engage and connect with others. People tend to be drawn to others who share similar attitudes, as they provide a sense of familiarity and compatibility.

- Compatibility of attitudes contributes to relationship satisfaction and longevity: When individuals share common attitudes, there is a greater likelihood of understanding, acceptance, and agreement within the relationship. This alignment fosters a sense of connection and satisfaction, leading to healthier and more enduring relationships.

- Conflicting attitudes can lead to relationship conflicts and breakdown: Divergent attitudes between partners or individuals in a relationship can create tension and disagreement. Conflicts arising from conflicting attitudes may escalate if not effectively addressed, potentially leading to relationship deterioration or even dissolution.

- Attitude alignment and compromise are essential in maintaining healthy relationships: In order to maintain harmonious relationships, individuals need to practice attitude alignment and compromise. This involves actively seeking understanding, finding common ground, and finding ways to accommodate differences in attitudes. Open communication and willingness to find solutions together contribute to relationship resilience.

Attitudes in the Workplace

- Attitudes influence job satisfaction, motivation, and organizational commitment: Positive attitudes towards work, colleagues, and the organization contribute to job satisfaction, motivation, and commitment. Individuals with positive attitudes are more likely to be engaged and productive, leading to a healthier work environment.

- Positive attitudes contribute to a harmonious work environment and productivity: When employees have positive attitudes, they tend to foster a cooperative and supportive work environment. Positive attitudes also enhance teamwork, communication, and collaboration among colleagues, resulting in increased productivity and efficiency.

- Negative attitudes can lead to conflict, absenteeism, and reduced performance: Negative attitudes, such as cynicism, apathy, or hostility, can undermine workplace dynamics and productivity. They contribute to interpersonal conflicts, absenteeism, and reduced performance. Negative attitudes can also spread among team members, negatively affecting the overall work atmosphere.

- Organizational culture and leadership play a role in shaping attitudes within the workplace: The organizational culture and leadership style greatly influence the attitudes exhibited within a workplace. A positive and supportive organizational culture, along with effective leadership, can foster positive attitudes among employees. Conversely, a toxic or unsupportive work culture can contribute to negative attitudes and hinder productivity.

Attitudes and Health Behavior

- Attitudes impact health-related behaviors, such as exercise, diet, and substance use: Attitudes play a significant role in determining individuals’ health-related behaviors. Positive attitudes towards healthy lifestyles and preventive measures, such as exercise and balanced diet, can lead to the adoption of healthy habits. Conversely, negative attitudes or beliefs can contribute to unhealthy behaviors and risk-taking.

- Health promotion campaigns aim to change attitudes and promote healthy behaviors: Public health initiatives often target attitudes as a key factor in behavior change. Health promotion campaigns utilize various strategies to educate, persuade, and shift attitudes towards healthier choices. They aim to create awareness, provide information, and influence individuals’ attitudes to encourage positive health behaviors.

- The Theory of Planned Behavior is often applied to understand health behavior change: The Theory of Planned Behavior posits that attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control collectively influence behavioral intentions, which, in turn, shape behavior. It provides insights into how attitudes interact with other factors to influence health-related decision-making and actions.

- Attitude-behavior consistency is crucial for maintaining healthy lifestyles: For individuals to maintain healthy lifestyles, there should be consistency between their attitudes and behaviors. When attitudes and behaviors align, individuals are more likely to engage in sustained healthy practices. Efforts to bridge any gaps between attitudes and behaviors through self-reflection, goal-setting, and behavior change strategies are crucial for maintaining long-term health.

Attitudes and Social Change

- Attitudes play a vital role in driving social change and influencing collective behavior: Social change often begins with a shift in attitudes. When individuals develop new perspectives and beliefs, they are more likely to challenge existing norms, advocate for change, and engage in collective action.

- Attitude-behavior discrepancies can motivate activism and advocacy efforts: When there is a misalignment between attitudes and the current state of affairs, individuals may be motivated to take action. Attitude-behavior discrepancies can fuel activism, leading individuals to advocate for social causes, raise awareness, and work towards societal improvements.

- Public attitudes shape policy-making and societal norms: The attitudes held by the general public have a significant influence on policy-making processes and the establishment of societal norms. Public opinion, driven by attitudes, can shape the development of laws, regulations, and social expectations that reflect the values and beliefs of a given society.

- Social movements rely on attitude change to create lasting impact: Social movements often aim to challenge prevailing attitudes and promote new perspectives on issues such as civil rights, environmental protection, or gender equality. By raising awareness, mobilizing supporters, and challenging existing attitudes, social movements seek to create lasting change in society.

Attitudes and behavior intertwine in various aspects of everyday life. In interpersonal relationships, attitudes shape the formation and dynamics of connections, with compatibility fostering satisfaction and conflicts arising from divergent attitudes. In the workplace, attitudes influence job satisfaction, productivity, and organizational harmony, with positive attitudes promoting a healthy work environment. Attitudes also play a crucial role in health behavior, where positive attitudes towards healthy choices contribute to well-being. Additionally, attitudes are instrumental in driving social change, shaping policies, and fueling activism for societal improvements. Understanding the complex relationship between attitudes and behavior allows individuals to navigate their personal and social lives with greater awareness and intentionality.

Attitudes and behavior are intricately linked, shaping our thoughts, actions, and interactions with the world. By understanding the nature of attitudes, influential factors, theoretical frameworks, and real-life applications, we gain insight into the complexities of human psychology. Developing a greater understanding of attitudes and behavior can lead to personal growth, improved relationships, and positive social change.

To leverage the knowledge gained from this blog post, consider the following takeaways:

- Self-reflection: Reflect on your own attitudes and how they influence your behavior.

- Understanding others: Recognize that individuals have diverse attitudes shaped by their unique experiences and backgrounds. Seek to understand others’ perspectives and empathize with their attitudes and behaviors.

- Influence of social factors: Be mindful of the influence of social norms, cultural values, and media on attitudes and behavior. Critically evaluate messages and media content, and question societal norms that may perpetuate harmful attitudes.

- Promoting positive attitudes: Cultivate positive attitudes that contribute to healthy relationships, a positive work environment, and personal well-being. Practice open-mindedness, empathy, and respect in your interactions with others.

- Health behavior change: Be aware of the impact of attitudes on health-related behaviors. Strive to develop positive attitudes towards health and well-being, and make conscious efforts to adopt healthy behaviors.

- Advocacy and social change: Recognize the power of attitudes in driving social change. Engage in advocacy efforts aligned with your values and work towards promoting attitudes that foster equality, justice, and sustainability.

- Continuous learning: Stay curious and keep exploring the field of psychology to deepen your understanding of attitudes and behavior. Stay updated with the latest research and theories to broaden your perspective and knowledge.

By applying these takeaways to your own life, you can actively shape your attitudes and behavior in a way that aligns with your values and contributes to personal growth and positive societal impact.

- Attitudes: Evaluative judgments formed towards objects, people, or ideas. Attitudes consist of cognitive, affective, and behavioral components.

- Cognitive Component: The element of attitudes that represents beliefs and thoughts associated with a particular attitude.

- Affective Component: The emotional and feeling aspect of attitudes, reflecting the emotional response associated with a particular attitude.

- Behavioral Component: The behavioral intentions and actions resulting from a specific attitude.

- Central Attitudes: Core attitudes that are more resistant to change and have a stronger impact on behavior.

- Peripheral Attitudes: Attitudes that are more malleable and subject to change based on external influences.

- Explicit Attitudes: Conscious attitudes that individuals are aware of and can articulate.

- Implicit Attitudes: Unconscious attitudes that influence behavior without conscious awareness.

- Attitude-Behavior Consistency: The alignment between attitudes and subsequent behavior.

- Elaboration Likelihood Model: A model explaining how attitudes are changed through central and peripheral routes of persuasion.

- Cognitive Dissonance Theory: The theory that proposes individuals strive for consistency between attitudes and behavior, and inconsistencies create psychological discomfort, motivating attitude change or behavior modification.

- Social Learning Theory: A theory that suggests individuals acquire attitudes and behaviors through observation and imitation of others, with vicarious reinforcement and punishment playing a significant role.

- Theory of Planned Behavior: A theory explaining the relationship between attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control, where behavioral intentions strongly influence actual behavior.

- Vicarious Reinforcement: Learning through observing others being rewarded for their behavior, which influences the adoption or rejection of attitudes and behaviors.

- Attitude Alignment: The process of adjusting attitudes to match those of others in order to reduce cognitive dissonance.

- Selective Exposure: A cognitive bias where individuals seek out information that aligns with their existing attitudes and beliefs.

- Rationalization: The process of justifying or explaining away inconsistencies between attitudes and behavior to reduce cognitive dissonance.

- Interpersonal Relationships: Connections and interactions between individuals, influenced by attitudes, compatibility, and attitude alignment.

- Job Satisfaction: The level of contentment and fulfillment individuals experience in their work, influenced by attitudes towards the job.

- Organizational Commitment: The extent to which individuals identify with and are dedicated to their organization, influenced by attitudes towards the workplace.

- Health Behavior: Behaviors related to health and well-being, such as exercise, diet, and substance use, influenced by attitudes.

- Health Promotion: Efforts to promote and encourage healthy behaviors through campaigns, education, and awareness.

- Social Change: The transformation of societal attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors, often driven by attitude-behavior discrepancies and activism.

- Activism: Active efforts to promote social or political change based on attitudes and beliefs.

- Advocacy: Public support and promotion of a particular cause or issue based on attitudes and values.

Last worded from Author

As we conclude this journey through the intricate world of attitudes and behavior, I hope this exploration has shed light on the fascinating dynamics that shape our thoughts and actions. Remember, you possess the power to understand and influence your attitudes, and consequently, your behavior. By cultivating self-awareness and actively examining the alignment between your attitudes and actions, you can pave the way for personal growth and positive change. Embrace the potential within you to challenge, adapt, and shape your attitudes, contributing to a better understanding of yourself and creating a ripple effect on the world around you. Your journey towards self-discovery starts now.

Attitudes and behavior are closely interconnected. Attitudes serve as evaluative judgments that influence how we perceive and respond to the world. While attitudes provide insights into our beliefs and values, they don’t always directly translate into behavior. The relationship between attitudes and behavior can be influenced by various factors, including social norms, situational constraints, and individual characteristics. Stronger attitudes, personal relevance, and consistency between attitudes and behavior increase the likelihood of behavior alignment.

Yes, attitudes can change over time. Attitude change can occur through various processes, such as exposure to new information, persuasive communication, personal experiences, and social influences. Cognitive dissonance, which arises from inconsistencies between attitudes and behavior, can also motivate attitude change. However, changing attitudes is not always easy, as individuals may hold onto their beliefs due to factors like cognitive biases, emotional attachments, and social pressures. Attitude change often requires a combination of critical thinking, open-mindedness, and exposure to alternative perspectives.

Social influences play a significant role in shaping attitudes and behavior. Social norms, cultural values, and group membership influence the development of attitudes. Conformity and social comparison can impact how individuals adopt or modify their attitudes to align with the beliefs and behaviors of others. Additionally, social learning theory suggests that individuals acquire attitudes and behaviors through observation and imitation of others, including role models and influential figures. Peer pressure, social expectations, and the desire for acceptance can all influence attitudes and subsequent behavior.

While attitudes can provide valuable insights into behavior, they do not always predict behavior with absolute accuracy. Attitudes serve as predispositions that influence our intentions and inclinations, but they are subject to numerous factors that can inhibit or facilitate behavior expression. Situational constraints, external pressures, and conflicting motives can affect the translation of attitudes into behavior. Additionally, the strength and accessibility of attitudes, along with the level of personal relevance, can impact the consistency between attitudes and behavior. It is important to consider multiple factors beyond attitudes alone when predicting behavior.

Aligning attitudes and behavior requires self-awareness, introspection, and intentional action. Start by examining your beliefs and values, and identify any inconsistencies between your attitudes and behavior. Reflect on the underlying reasons for these discrepancies. Strive for clarity and self-reflection to understand the motivations behind your attitudes. Consider the influence of external factors and social pressures on your behavior. With this understanding, set realistic goals to align your behavior with your desired attitudes. Make a conscious effort to act in ways that are consistent with your beliefs, and continuously monitor and adjust your actions to ensure alignment.

Emotions play a crucial role in attitude formation and behavioral responses. Emotionally charged events can shape attitudes and trigger corresponding behavior. Emotions can influence the evaluation of information, the encoding of memories, and the decision-making process. Positive emotions can enhance the likelihood of adopting attitudes and engaging in behavior, while negative emotions can have the opposite effect. Emotional intelligence and regulation also impact how attitudes and behaviors are expressed and managed in social interactions. It is essential to recognize and understand the emotional influences on attitudes and behavior to foster healthy and adaptive responses.

(1) Relationship between Attitude and Behavior – theintactone. https://theintactone.com/2019/06/28/mpob-u3-topic-8-relationship-between-attitude-and-behavior/ .

(2) What Is Attitude in Psychology? Definition, Formation, Changes. https://www.verywellmind.com/attitudes-how-they-form-change-shape-behavior-2795897 .

(3) Attitudes | SpringerLink. https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-3-319-28099-8_1777-1 .

(4) Components of Attitude: ABC Model – Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/attitudes.html .

- The Relationship Between Attitudes and Behavior: Explained in Detail

- Attitude: A Key to Personal Growth and Success

Dr. Deeksha Mishra

Dr. Deeksha Mishra is a highly accomplished psychology counselor and training specialist with over a decade of experience. She holds a doctrine from Banaras Hindu University and has made significant contributions in her field.With a diverse background, Dr. Mishra has worked at esteemed institutions such as All India Institute of Medical Sciences [AIIMS], New Delhi, Lady Hardinge Medical College, New Delhi and Institute of Human Behaviour and Allied Sciences [IHBAS], New Delhi. She has served as a Psychology Counselor and Training Specialist at Hindustan Latex Family Planning Promotion Trust (HLFPPT), Lucknow, contributing to government projects.Dr. Mishra's expertise extends beyond traditional settings, as she continues to provide therapy and counseling to patients through video calls and phone consultations. Her commitment to mental health and well-being is unwavering, and she has positively impacted countless lives through her empathetic approach and insightful guidance.Join Dr. Deeksha Mishra on our blog site as she shares her extensive knowledge, experiences, and valuable insights. Discover the transformative power of psychology and gain inspiration to enhance your own well-being.

Related Articles

How To Control Ego : Strategies for Self-Mastery

Abstract: In this blog post, we delve into the profound topic of...

Understanding Aggressive Attitude: Causes, Effects, and Strategies for Managing it

Abstract: This blog post aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of aggressive...

Attitude and Character: Unveiling the Distinctions

Abstract: In this blog post, we will delve into the intriguing contrasts...

How To Stop Being An Introvert And Embrace a More Social Lifestyle

Abstract: In this blog post, we will explore How To Stop Being...

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics