share this!

August 16, 2021

Is it time to get rid of homework? Mental health experts weigh in

by Sara M Moniuszko

It's no secret that kids hate homework. And as students grapple with an ongoing pandemic that has had a wide-range of mental health impacts, is it time schools start listening to their pleas over workloads?

Some teachers are turning to social media to take a stand against homework .

Tiktok user @misguided.teacher says he doesn't assign it because the "whole premise of homework is flawed."

For starters, he says he can't grade work on "even playing fields" when students' home environments can be vastly different.

"Even students who go home to a peaceful house, do they really want to spend their time on busy work? Because typically that's what a lot of homework is, it's busy work," he says in the video that has garnered 1.6 million likes. "You only get one year to be 7, you only got one year to be 10, you only get one year to be 16, 18."

Mental health experts agree heavy work loads have the potential do more harm than good for students, especially when taking into account the impacts of the pandemic. But they also say the answer may not be to eliminate homework altogether.

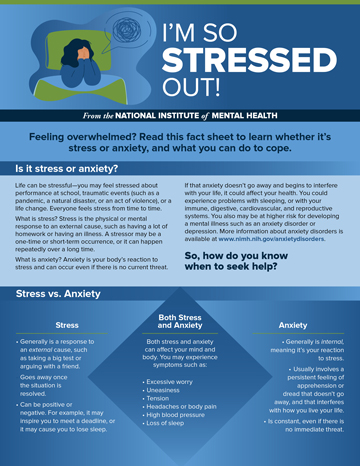

Emmy Kang, mental health counselor at Humantold, says studies have shown heavy workloads can be "detrimental" for students and cause a "big impact on their mental, physical and emotional health."

"More than half of students say that homework is their primary source of stress, and we know what stress can do on our bodies," she says, adding that staying up late to finish assignments also leads to disrupted sleep and exhaustion.

Cynthia Catchings, a licensed clinical social worker and therapist at Talkspace, says heavy workloads can also cause serious mental health problems in the long run, like anxiety and depression.

And for all the distress homework causes, it's not as useful as many may think, says Dr. Nicholas Kardaras, a psychologist and CEO of Omega Recovery treatment center.

"The research shows that there's really limited benefit of homework for elementary age students, that really the school work should be contained in the classroom," he says.

For older students, Kang says homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night.

"Most students, especially at these high-achieving schools, they're doing a minimum of three hours, and it's taking away time from their friends from their families, their extracurricular activities. And these are all very important things for a person's mental and emotional health."

Catchings, who also taught third to 12th graders for 12 years, says she's seen the positive effects of a no homework policy while working with students abroad.

"Not having homework was something that I always admired from the French students (and) the French schools, because that was helping the students to really have the time off and really disconnect from school ," she says.

The answer may not be to eliminate homework completely, but to be more mindful of the type of work students go home with, suggests Kang, who was a high-school teacher for 10 years.

"I don't think (we) should scrap homework, I think we should scrap meaningless, purposeless busy work-type homework. That's something that needs to be scrapped entirely," she says, encouraging teachers to be thoughtful and consider the amount of time it would take for students to complete assignments.

The pandemic made the conversation around homework more crucial

Mindfulness surrounding homework is especially important in the context of the last two years. Many students will be struggling with mental health issues that were brought on or worsened by the pandemic, making heavy workloads even harder to balance.

"COVID was just a disaster in terms of the lack of structure. Everything just deteriorated," Kardaras says, pointing to an increase in cognitive issues and decrease in attention spans among students. "School acts as an anchor for a lot of children, as a stabilizing force, and that disappeared."

But even if students transition back to the structure of in-person classes, Kardaras suspects students may still struggle after two school years of shifted schedules and disrupted sleeping habits.

"We've seen adults struggling to go back to in-person work environments from remote work environments. That effect is amplified with children because children have less resources to be able to cope with those transitions than adults do," he explains.

'Get organized' ahead of back-to-school

In order to make the transition back to in-person school easier, Kang encourages students to "get good sleep, exercise regularly (and) eat a healthy diet."

To help manage workloads, she suggests students "get organized."

"There's so much mental clutter up there when you're disorganized... sitting down and planning out their study schedules can really help manage their time," she says.

Breaking assignments up can also make things easier to tackle.

"I know that heavy workloads can be stressful, but if you sit down and you break down that studying into smaller chunks, they're much more manageable."

If workloads are still too much, Kang encourages students to advocate for themselves.

"They should tell their teachers when a homework assignment just took too much time or if it was too difficult for them to do on their own," she says. "It's good to speak up and ask those questions. Respectfully, of course, because these are your teachers. But still, I think sometimes teachers themselves need this feedback from their students."

©2021 USA Today Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Explore further

Feedback to editors

New 'atlas' provides unprecedented insights on how genes function in early embryo development

9 minutes ago

Researchers reveal dynamic structure of FLVCR proteins and their function in nutrient transport

24 minutes ago

International planet hunters unveil massive catalog of strange worlds

Earth 2.0 or its evil twin? Discovery of Earth-sized planet could shed light on conditions necessary for life

25 minutes ago

Birth of universe's earliest galaxies observed for first time

36 minutes ago

Drought in the Brazil's Cerrado is the worst for at least seven centuries, study shows

37 minutes ago

Three sisters garden study finds balanced pollinator-plant network faces an uncertain future

45 minutes ago

Dangerous brew: Ocean heat and La Nina combo likely mean more Atlantic hurricanes this summer

46 minutes ago

Study: While most of the world trusts climate scientists, a skeptical minority can lead to climate inaction

Silky shark makes record breaking migration in international waters of the Tropical Eastern Pacific

2 hours ago

Relevant PhysicsForums posts

Physics education is 60 years out of date.

May 16, 2024

Is "College Algebra" really just high school "Algebra II"?

May 14, 2024

Plagiarism & ChatGPT: Is Cheating with AI the New Normal?

May 13, 2024

Physics Instructor Minimum Education to Teach Community College

May 11, 2024

Studying "Useful" vs. "Useless" Stuff in School

Apr 30, 2024

Why are Physicists so informal with mathematics?

Apr 29, 2024

More from STEM Educators and Teaching

Related Stories

Smartphones are lowering student's grades, study finds

Aug 18, 2020

Doing homework is associated with change in students' personality

Oct 6, 2017

Scholar suggests ways to craft more effective homework assignments

Oct 1, 2015

Should parents help their kids with homework?

Aug 29, 2019

How much math, science homework is too much?

Mar 23, 2015

Anxiety, depression, burnout rising as college students prepare to return to campus

Jul 26, 2021

Recommended for you

First-generation medical students face unique challenges and need more targeted support, say researchers

Investigation reveals varied impact of preschool programs on long-term school success

May 2, 2024

Training of brain processes makes reading more efficient

Apr 18, 2024

Researchers find lower grades given to students with surnames that come later in alphabetical order

Apr 17, 2024

Earth, the sun and a bike wheel: Why your high-school textbook was wrong about the shape of Earth's orbit

Apr 8, 2024

Touchibo, a robot that fosters inclusion in education through touch

Apr 5, 2024

Let us know if there is a problem with our content

Use this form if you have come across a typo, inaccuracy or would like to send an edit request for the content on this page. For general inquiries, please use our contact form . For general feedback, use the public comments section below (please adhere to guidelines ).

Please select the most appropriate category to facilitate processing of your request

Thank you for taking time to provide your feedback to the editors.

Your feedback is important to us. However, we do not guarantee individual replies due to the high volume of messages.

E-mail the story

Your email address is used only to let the recipient know who sent the email. Neither your address nor the recipient's address will be used for any other purpose. The information you enter will appear in your e-mail message and is not retained by Phys.org in any form.

Newsletter sign up

Get weekly and/or daily updates delivered to your inbox. You can unsubscribe at any time and we'll never share your details to third parties.

More information Privacy policy

Donate and enjoy an ad-free experience

We keep our content available to everyone. Consider supporting Science X's mission by getting a premium account.

E-mail newsletter

- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty/Staff

News and Media

- News & Media Home

- Research Stories

- School's In

- In the Media

You are here

More than two hours of homework may be counterproductive, research suggests.

A Stanford education researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter. "Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good," wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education . The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students' views on homework. Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year. Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night. "The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students' advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being," Pope wrote. Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school. Their study found that too much homework is associated with: • Greater stress : 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor. • Reductions in health : In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems. • Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits : Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were "not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills," according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy. A balancing act The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills. Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as "pointless" or "mindless" in order to keep their grades up. "This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points," said Pope, who is also a co-founder of Challenge Success , a nonprofit organization affiliated with the GSE that conducts research and works with schools and parents to improve students' educational experiences.. Pope said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said. "Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development," wrote Pope. High-performing paradox In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. "Young people are spending more time alone," they wrote, "which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities." Student perspectives The researchers say that while their open-ended or "self-reporting" methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for "typical adolescent complaining" – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe. The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Clifton B. Parker is a writer at the Stanford News Service .

More Stories

⟵ Go to all Research Stories

Get the Educator

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Stanford Graduate School of Education

482 Galvez Mall Stanford, CA 94305-3096 Tel: (650) 723-2109

- Contact Admissions

- GSE Leadership

- Site Feedback

- Web Accessibility

- Career Resources

- Faculty Open Positions

- Explore Courses

- Academic Calendar

- Office of the Registrar

- Cubberley Library

- StanfordWho

- StanfordYou

Improving lives through learning

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

The Truth About Homework Stress: What Parents & Students Need to Know

- Fact Checked

Written by:

published on:

- December 21, 2023

Updated on:

- January 9, 2024

Looking for a therapist?

Homework is generally given out to ensure that students take time to review and remember the days lessons. It can help improve on a student’s general performance and enhance traits like self-discipline and independent problem solving.

Parents are able to see what their children are doing in school, while also helping teachers determine how well the lesson material is being learned. Homework is quite beneficial when used the right way and can improve student performance.

This well intentioned practice can turn sour if it’s not handled the right way. Studies show that if a student is inundated with too much homework, not only do they get lower scores, but they are more likely to get stressed.

The age at which homework stress is affecting students is getting lower, some even as low as kindergarten. Makes you wonder what could a five year old possibly need to review as homework?

One of the speculated reasons for this stress is that the complexity of what a student is expected to learn is increasing, while the breaks for working out excess energy are reduced. Students are getting significantly more homework than recommended by the education leaders, some even nearly three times more.

To make matters worse, teachers may give homework that is both time consuming and will keep students busy while being totally non-productive.

Remedial work like telling students to copy notes word for word from their text books will do nothing to improve their grades or help them progress. It just adds unnecessary stress.

Explore emotional well-being with BetterHelp – your partner in affordable online therapy. With 30,000+ licensed therapists and plans starting from only $65 per week, BetterHelp makes self-care accessible to all. Complete the questionnaire to match with the right therapist.

Effects of homework stress at home

Both parents and students tend to get stressed out at the beginning of a new school year due to the impending arrival of homework.

Nightly battles centered on finishing assignments are a household routine in houses with students.

Research has found that too much homework can negatively affect children. In creating a lack of balance between play time and time spent doing homework, a child can get headaches, sleep deprivation or even ulcers.

And homework stress doesn’t just impact grade schoolers. College students are also affected, and the stress is affecting their academic performance.

Even the parent’s confidence in their abilities to help their children with homework suffers due increasing stress levels in the household.

Fights and conflict over homework are more likely in families where parents do not have at least a college degree. When the child needs assistance, they have to turn to their older siblings who might already be bombarded with their own homework.

Parents who have a college degree feel more confident in approaching the school and discussing the appropriate amount of school work.

“It seems that homework being assigned discriminates against parents who don’t have college degree, parents who have English as their second language and against parents who are poor.” Said Stephanie Donaldson Pressman, the contributing editor of the study and clinical director of the New England Center for Pediatric Psychology.

With all the stress associated with homework, it’s not surprising that some parents have opted not to let their children do homework. Parents that have instituted a no-homework policy have stated that it has taken a lot of the stress out of their evenings.

The recommended amount homework

The standard endorsed by the National Education Association is called the “10 minute rule”; 10 minutes per grade level per night. This recommendation was made after a number of studies were done on the effects of too much homework on families.

The 10 minute rule basically means 10 minutes of homework in the first grade, 20 minute for the second grade all the way up to 120 minutes for senior year in high school. Note that no homework is endorsed in classes under the first grade.

Parents reported first graders were spending around half an hour on homework each night, and kindergarteners spent 25 minutes a night on assignments according to a study carried out by Brown University.

Making a five year old sit still for half an hour is very difficult as they are at the age where they just want to move around and play.

A child who is exposed to 4-5 hours of homework after school is less likely to find the time to go out and play with their friends, which leads to accumulation of stress energy in the body.

Their social life also suffers because between the time spent at school and doing homework, a child will hardly have the time to pursue hobbies. They may also develop a negative attitude towards learning.

The research highlighted that 56% of students consider homework a primary source of stress.

And if you’re curious how the U.S stacks up against other countries in regards to how much time children spend on homework, it’s pretty high on the list .

Signs to look out for on a student that has homework stress

Since not every student is affected by homework stress in the same way, it’s important to be aware of some of the signs your child might be mentally drained from too much homework.

Here are some common signs of homework stress:

- Sleep disturbances

- Frequent stomachaches and headaches

- Decreased appetite or changed eating habits

- New or recurring fears

- Not able to relax

- Regressing to behavior they had when younger

- Bursts of anger crying or whining

- Becoming withdrawn while others may become clingy

- Drastic changes in academic performance

- Having trouble concentrating or completing homework

- Constantly complains about their ability to do homework

If you’re a parent and notice any of these signs in your child, step in to find out what’s going on and if homework is the source of their stress.

If you’re a student, pay attention if you start experiencing any of these symptoms as a result of your homework load. Don’t be afraid to ask your teacher or parents for help if the stress of homework becomes too much for you.

What parents do wrong when it comes to homework stress

Most parents push their children to do more and be more, without considering the damage being done by this kind of pressure.

Some think that homework brought home is always something the children can deal with on their own. If the child cannot handle their homework then these parents get angry and make the child feel stupid.

This may lead to more arguing and increased dislike of homework in the household. Ultimately the child develops an even worse attitude towards homework.

Another common mistake parents make is never questioning the amount of homework their children get, or how much time they spend on it. It’s easy to just assume whatever the teacher assigned is adequate, but as we mentioned earlier, that’s not always the case.

Be proactive and involved with your child’s homework. If you notice they’re spending hours every night on homework, ask them about it. Just because they don’t complain doesn’t mean there isn’t a problem.

How can parents help?

- While every parent wants their child to become successful and achieve the very best, it’s important to pull back on the mounting pressure and remember that they’re still just kids. They need time out to release their stress and connect with other children.

- Many children may be afraid to admit that they’re overwhelmed by homework because they might be misconstrued as failures. The best thing a parent can do is make home a safe place for children to express themselves freely. You can do this by lending a listening ear and not judging your kids.

- Parents can also take the initiative to let the school know that they’re unhappy with the amount of homework being given. Even if you don’t feel comfortable complaining, you can approach the school through the parent-teacher association available and request your representative to plead your case.

- It may not be all the subjects that are causing your child to get stressed. Parents should find out if there is a specific subject of homework that is causing stress. You could also consult with other parents to see what they can do to fix the situation. It may be the amount or the content that causes stress, so the first step is identifying the problem.

- Work with your child to create a schedule for getting homework done on time. You can set a specific period of time for homework, and schedule time for other activities too. Strike a balance between work and play.

- Understanding that your child is stressed about homework doesn’t mean you have to allow them not to try. Let them sit down and work on it as much as they’re able to, and recruit help from the older siblings or a neighbor if possible.

- Check out these resources to help your child with their homework .

The main idea here is to not abolish homework completely, but to review the amount and quality of homework being given out. Stress, depression and lower grades are the last things parents want for their children.

The schools and parents need to work together to find a solution to this obvious problem.

Take the stress test!

Join the Find-a-therapist community and get access to our free stress assessment!

Additional Resources

Online therapy.

Discover a path to emotional well-being with BetterHelp – your partner in convenient and affordable online therapy. With a vast network of 30,000+ licensed therapists, they’re committed to helping you find the one to support your needs. Take advantage of their Free Online Assessment, and connect with a therapist who truly understands you. Begin your journey today.

Relationship Counceling

Whether you’re facing communication challenges, trust issues, or simply seeking to strengthen your connection, ReGain’ s experienced therapists are here to guide you and your partner toward a healthier, happier connection from the comfort of your own space. Get started.

Therapist Directory

Discover the perfect therapist who aligns with your goals and preferences, allowing you to take charge of your mental health. Whether you’re searching for a specialist based on your unique needs, experience level, insurance coverage, budget, or location, our user-friendly platform has you covered. Search here.

About the author

You might also be interested in

10 Harmful Effects of Stress on The Body

7 Young Adult Therapy Options Near Me in 2024

How To Confront A Liar (and one time when you just shouldn’t.)

Disclaimers

Online Therapy, Your Way

Follow us on social media

We may receive a commission if you click on and become a paying customer of a therapy service that we mention.

The information contained in Find A Therapist is general in nature and is not medical advice. Please seek immediate in-person help if you are in a crisis situation.

Therapy Categories

More information

If you are in a life threatening situation – don’t use this site. Call +1 (800) 273-8255 or check these resources to get immediate help.

Along with Stanford news and stories, show me:

- Student information

- Faculty/Staff information

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

Education scholar Denise Pope has found that too much homework has negative effects on student well-being and behavioral engagement. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

A Stanford researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter.

“Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good,” wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education .

The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students’ views on homework.

Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year.

Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night.

“The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students’ advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being,” Pope wrote.

Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school.

Their study found that too much homework is associated with:

* Greater stress: 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor.

* Reductions in health: In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems.

* Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits: Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were “not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills,” according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy.

A balancing act

The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills.

Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as “pointless” or “mindless” in order to keep their grades up.

“This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points,” Pope said.

She said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said.

“Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development,” wrote Pope.

High-performing paradox

In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. “Young people are spending more time alone,” they wrote, “which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities.”

Student perspectives

The researchers say that while their open-ended or “self-reporting” methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for “typical adolescent complaining” – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe.

The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Media Contacts

Denise Pope, Stanford Graduate School of Education: (650) 725-7412, [email protected] Clifton B. Parker, Stanford News Service: (650) 725-0224, [email protected]

Does homework really work?

by: Leslie Crawford | Updated: December 12, 2023

Print article

You know the drill. It’s 10:15 p.m., and the cardboard-and-toothpick Golden Gate Bridge is collapsing. The pages of polynomials have been abandoned. The paper on the Battle of Waterloo seems to have frozen in time with Napoleon lingering eternally over his breakfast at Le Caillou. Then come the tears and tantrums — while we parents wonder, Does the gain merit all this pain? Is this just too much homework?

However the drama unfolds night after night, year after year, most parents hold on to the hope that homework (after soccer games, dinner, flute practice, and, oh yes, that childhood pastime of yore known as playing) advances their children academically.

But what does homework really do for kids? Is the forest’s worth of book reports and math and spelling sheets the average American student completes in their 12 years of primary schooling making a difference? Or is it just busywork?

Homework haterz

Whether or not homework helps, or even hurts, depends on who you ask. If you ask my 12-year-old son, Sam, he’ll say, “Homework doesn’t help anything. It makes kids stressed-out and tired and makes them hate school more.”

Nothing more than common kid bellyaching?

Maybe, but in the fractious field of homework studies, it’s worth noting that Sam’s sentiments nicely synopsize one side of the ivory tower debate. Books like The End of Homework , The Homework Myth , and The Case Against Homework the film Race to Nowhere , and the anguished parent essay “ My Daughter’s Homework is Killing Me ” make the case that homework, by taking away precious family time and putting kids under unneeded pressure, is an ineffective way to help children become better learners and thinkers.

One Canadian couple took their homework apostasy all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada. After arguing that there was no evidence that it improved academic performance, they won a ruling that exempted their two children from all homework.

So what’s the real relationship between homework and academic achievement?

How much is too much?

To answer this question, researchers have been doing their homework on homework, conducting and examining hundreds of studies. Chris Drew Ph.D., founder and editor at The Helpful Professor recently compiled multiple statistics revealing the folly of today’s after-school busy work. Does any of the data he listed below ring true for you?

• 45 percent of parents think homework is too easy for their child, primarily because it is geared to the lowest standard under the Common Core State Standards .

• 74 percent of students say homework is a source of stress , defined as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss, and stomach problems.

• Students in high-performing high schools spend an average of 3.1 hours a night on homework , even though 1 to 2 hours is the optimal duration, according to a peer-reviewed study .

Not included in the list above is the fact many kids have to abandon activities they love — like sports and clubs — because homework deprives them of the needed time to enjoy themselves with other pursuits.

Conversely, The Helpful Professor does list a few pros of homework, noting it teaches discipline and time management, and helps parents know what’s being taught in the class.

The oft-bandied rule on homework quantity — 10 minutes a night per grade (starting from between 10 to 20 minutes in first grade) — is listed on the National Education Association’s website and the National Parent Teacher Association’s website , but few schools follow this rule.

Do you think your child is doing excessive homework? Harris Cooper Ph.D., author of a meta-study on homework , recommends talking with the teacher. “Often there is a miscommunication about the goals of homework assignments,” he says. “What appears to be problematic for kids, why they are doing an assignment, can be cleared up with a conversation.” Also, Cooper suggests taking a careful look at how your child is doing the assignments. It may seem like they’re taking two hours, but maybe your child is wandering off frequently to get a snack or getting distracted.

Less is often more

If your child is dutifully doing their work but still burning the midnight oil, it’s worth intervening to make sure your child gets enough sleep. A 2012 study of 535 high school students found that proper sleep may be far more essential to brain and body development.

For elementary school-age children, Cooper’s research at Duke University shows there is no measurable academic advantage to homework. For middle-schoolers, Cooper found there is a direct correlation between homework and achievement if assignments last between one to two hours per night. After two hours, however, achievement doesn’t improve. For high schoolers, Cooper’s research suggests that two hours per night is optimal. If teens have more than two hours of homework a night, their academic success flatlines. But less is not better. The average high school student doing homework outperformed 69 percent of the students in a class with no homework.

Many schools are starting to act on this research. A Florida superintendent abolished homework in her 42,000 student district, replacing it with 20 minutes of nightly reading. She attributed her decision to “ solid research about what works best in improving academic achievement in students .”

More family time

A 2020 survey by Crayola Experience reports 82 percent of children complain they don’t have enough quality time with their parents. Homework deserves much of the blame. “Kids should have a chance to just be kids and do things they enjoy, particularly after spending six hours a day in school,” says Alfie Kohn, author of The Homework Myth . “It’s absurd to insist that children must be engaged in constructive activities right up until their heads hit the pillow.”

By far, the best replacement for homework — for both parents and children — is bonding, relaxing time together.

Homes Nearby

Homes for rent and sale near schools

How families of color can fight for fair discipline in school

Dealing with teacher bias

The most important school data families of color need to consider

Yes! Sign me up for updates relevant to my child's grade.

Please enter a valid email address

Thank you for signing up!

Server Issue: Please try again later. Sorry for the inconvenience

US South Carolina

Recently viewed courses

Recently viewed.

Find Your Dream School

This site uses various technologies, as described in our Privacy Policy, for personalization, measuring website use/performance, and targeted advertising, which may include storing and sharing information about your site visit with third parties. By continuing to use this website you consent to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use .

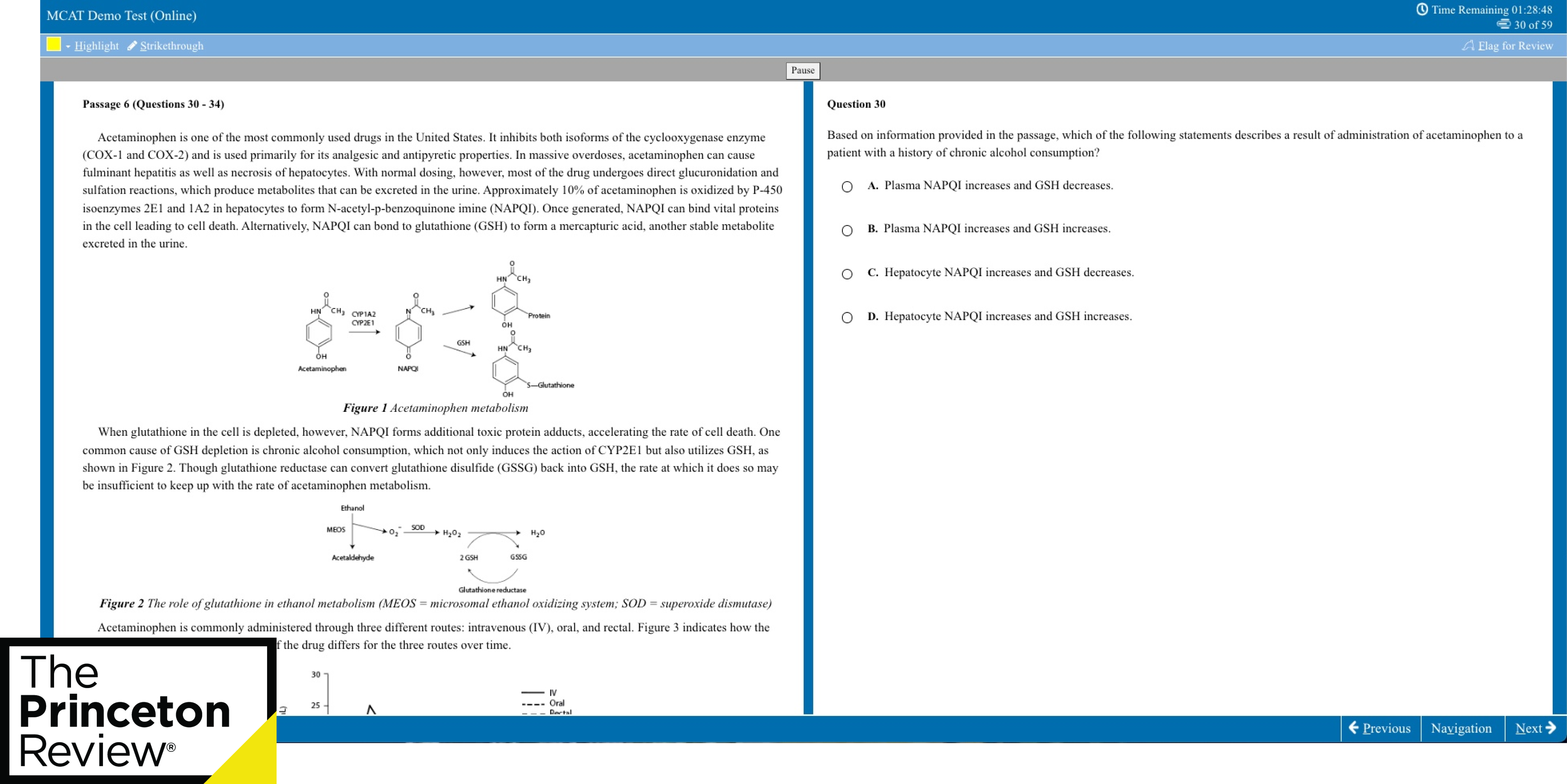

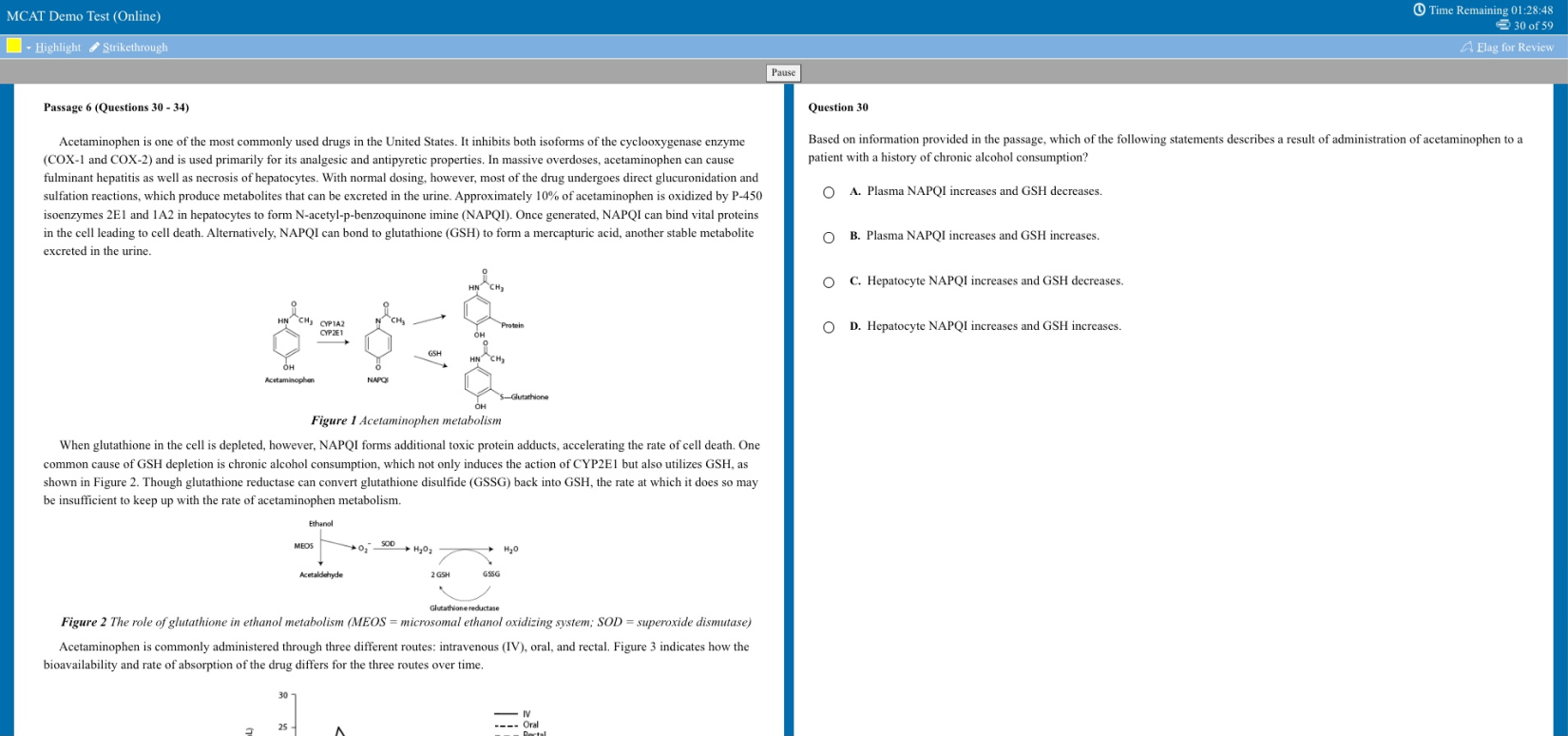

COVID-19 Update: To help students through this crisis, The Princeton Review will continue our "Enroll with Confidence" refund policies. For full details, please click here.

Enter your email to unlock an extra $25 off an SAT or ACT program!

By submitting my email address. i certify that i am 13 years of age or older, agree to recieve marketing email messages from the princeton review, and agree to terms of use., how to manage homework stress.

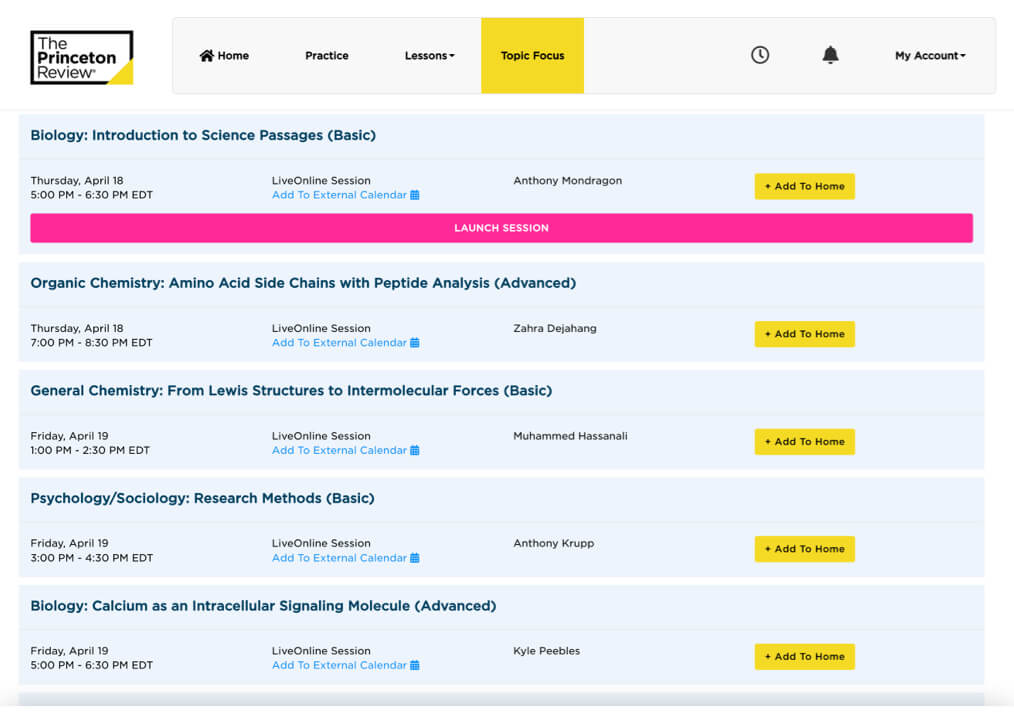

Feeling overwhelmed by your nightly homework grind? You’re not alone. Our Student Life in America survey results show that teens spend a third of their study time feeling worried, stressed, or stuck. If you’re spending close to four hours a night on your homework (the national average), that’s over an hour spent spent feeling panicky and still not getting your work done. Homework anxiety can become a self-fulfilling prophecy: If you’re already convinced that calculus is unconquerable, that anxiety can actually block your ability to learn the material.

Whether your anxiety is related to handling your workload (we know you’re getting more homework than ever!), mastering a particular subject like statistics, or getting great grades for your college application, stress doesn’t have to go hand-in-hand with studying .

In fact, a study by Stanford University School of Medicine and published in The Journal of Neuroscience shows that a student’s fear of math (and, yes, this fear is completely real and can be detectable in scans of the brain) can be eased by a one-on-one math tutoring program. At The Princeton Review this wasn’t news to us! Our online tutors are on-call 24/7 for students working on everything from AP Chemistry to Pre-Calc. Here’s a roundup of what our students have to say about managing homework stress by working one-one-one with our expert tutors .

1. Work the Best Way for YOU

From the way you decorate your room to the way you like to study, you have a style all your own:

"I cannot thank Christopher enough! I felt so anxious and stressed trying to work on my personal statement, and he made every effort to help me realize my strengths and focus on writing in a way that honored my personality. I wanted to give up, but he was patient with me and it made the difference."

"[My] tutor was 1000000000000% great . . . He made me feel important and fixed all of my mistakes and adapted to my learning style . . . I have so much confidence for my midterms that I was so stressed out about."

"I liked how the tutor asked me how was I starting the problem and allowed me to share what I was doing and what I had. The tutor was able to guide me from there and break down the steps and I got the answer all on my own and the tutor double checked it... saved me from tears and stress."

2. Study Smarter, Not Harder

If you’ve read the chapter in your history textbook twice and aren’t retaining the material, don’t assume the third time will be the charm. Our tutors will help you break the pattern, and learn ways to study more efficiently:

"[My] tutor has given me an easier, less stressful way of seeing math problems. It is like my eyes have opened up."

"I was so lost in this part of math but within minutes the tutor had me at ease and I get it now. I wasn't even with her maybe 30 minutes or so, and she helped me figure out what I have been stressing over for the past almost two days."

"I can not stress how helpful it is to have a live tutor available. Math was never and still isn't my favorite subject, but I know I need to take it. Being able to talk to someone and have them walk you through the steps on how to solve a problem is a huge weight lifted off of my shoulder."

3. Get Help in a Pinch

Because sometimes you need a hand RIGHT NOW:

"I was lost and stressed because I have a test tomorrow and did not understand the problems. I fully get it now!"

"My tutor was great. I was freaking out and stressed out about the entire assignment, but she really helped me to pull it together. I am excited to turn my paper in tomorrow."

"This was so helpful to have a live person to validate my understanding of the formulas I need to use before actually submitting my homework and getting it incorrect. My stress level reduced greatly with a project deadline due date."

4. Benefit from a Calming Presence

From PhDs and Ivy Leaguers to doctors and teachers, our tutors are experts in their fields, and they know how to keep your anxiety at bay:

"I really like that the tutors are real people and some of them help lighten the stress by making jokes or having quirky/witty things to say. That helps when you think you're messing up! Gives you a reprieve from your brain jumbling everything together!"

"He seemed understanding and empathetic to my situation. That means a lot to a new student who is under stress."

"She was very thorough in explaining her suggestions as well as asking questions and leaving the changes up to me, which I really appreciated. She was very encouraging and motivating which helped with keeping me positive about my paper and knowing that I am not alone in my struggles. She definitely eased my worries and stress. She was wonderful!"

5. Practice Makes Perfect

The Stanford study shows that repeated exposure to math problems through one-on-one tutoring helped students relieve their math anxiety (the authors’ analogy was how a fear of spiders can be treated with repeated exposure to spiders in a safe environment). Find a tutor you love, and come back to keep practicing:

"Love this site once again. It’s so helpful and this is the first time in years when I don’t stress about my frustration with HW because I know this site will always be here to help me."

"I've been using this service since I was in seventh grade and now I am a Freshman in High School. School has just started and I am already using this site again! :) This site is so dependable. I love it so much and it’s a lot easier than having an actual teacher sitting there hovering over you, waiting for you to finish the problem."

"I can always rely on this site to help me when I'm confused, and it always makes me feel more confident in the work I'm doing in school."

Stuck on homework?

Try an online tutoring session with one of our experts, and get homework help in 40+ subjects.

Try a Free Session

- Tutoring

- College

- Applying to College

Explore Colleges For You

Connect with our featured colleges to find schools that both match your interests and are looking for students like you.

Career Quiz

Take our short quiz to learn which is the right career for you.

Get Started on Athletic Scholarships & Recruiting!

Join athletes who were discovered, recruited & often received scholarships after connecting with NCSA's 42,000 strong network of coaches.

Best 389 Colleges

165,000 students rate everything from their professors to their campus social scene.

SAT Prep Courses

1400+ course, act prep courses, free sat practice test & events, 1-800-2review, free digital sat prep try our self-paced plus program - for free, get a 14 day trial.

Free MCAT Practice Test

I already know my score.

MCAT Self-Paced 14-Day Free Trial

Enrollment Advisor

1-800-2REVIEW (800-273-8439) ext. 1

1-877-LEARN-30

Mon-Fri 9AM-10PM ET

Sat-Sun 9AM-8PM ET

Student Support

1-800-2REVIEW (800-273-8439) ext. 2

Mon-Fri 9AM-9PM ET

Sat-Sun 8:30AM-5PM ET

Partnerships

- Teach or Tutor for Us

College Readiness

International

Advertising

Affiliate/Other

- Enrollment Terms & Conditions

- Accessibility

- Cigna Medical Transparency in Coverage

Register Book

Local Offices: Mon-Fri 9AM-6PM

- SAT Subject Tests

Academic Subjects

- Social Studies

Find the Right College

- College Rankings

- College Advice

- Applying to College

- Financial Aid

School & District Partnerships

- Professional Development

- Advice Articles

- Private Tutoring

- Mobile Apps

- Local Offices

- International Offices

- Work for Us

- Affiliate Program

- Partner with Us

- Advertise with Us

- International Partnerships

- Our Guarantees

- Accessibility – Canada

Privacy Policy | CA Privacy Notice | Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information | Your Opt-Out Rights | Terms of Use | Site Map

©2024 TPR Education IP Holdings, LLC. All Rights Reserved. The Princeton Review is not affiliated with Princeton University

TPR Education, LLC (doing business as “The Princeton Review”) is controlled by Primavera Holdings Limited, a firm owned by Chinese nationals with a principal place of business in Hong Kong, China.

- Search Please fill out this field.

- Manage Your Subscription

- Give a Gift Subscription

- Newsletters

- Sweepstakes

Is Homework a Waste of Students' Time? Study Finds It's the Biggest Cause of Teen Stress

As the debate over the need for homework continues, a new study found that it's the biggest cause of teen stress, leading to sleepless nights and poor academic performance

Julie Mazziotta is the Sports Editor at PEOPLE, covering everything from the NFL to tennis to Simone Biles and Tom Brady. She was previously an Associate Editor for the Health vertical for six years, and prior to joining PEOPLE worked at Health Magazine. When not covering professional athletes, Julie spends her time as a (very) amateur athlete, training for marathons, long bike trips and hikes.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/J.Mazziotta2334-e3daa71fe1a745929e739c08e585253f.jpg)

It’s the bane of every teen’s existence. After sitting through hours at school, they leave only to get started on mountains of homework. And educators are mixed on its effectiveness . Some say the practice reinforces what students learned during the day, while others argue that it put unnecessary stress on kids and parents , who are often stuck nagging or helping.

According to a new study, conducted by the Better Sleep Council , that homework stress is the biggest source of frustration for teens, with 74 percent of those surveyed ranking it the highest, above self-esteem (51 percent) parental expectations (45 percent) and bullying (15 percent).

Homework is taking up a large chunk of their time , too — around 15-plus hours a week, with about one-third of teens reporting that it’s closer to 20-plus hours.

The stress and excessive homework adds up to lost sleep, the BSC says. According to the survey, 57 percent of teenagers said that they don’t get enough sleep, with 67 reporting that they get just five to seven hours a night — a far cry from the recommended eight to ten hours. The BSC says that their research shows that when teens feel more stressed, their sleep suffers. They go to sleep later, wake up earlier and have more trouble falling and staying asleep than less-stressed teens.

“We’re finding that teenagers are experiencing this cycle where they sacrifice their sleep to spend extra time on homework, which gives them more stress — but they don’t get better grades,” said Mary Helen Rogers, the vice president of marketing and communications for the BSC.

RELATED VIDEO: To Help Or Not To Help: Moms Talk About Whether Or Not They Help Their Children With Homework

Another interesting finding from this study: students who go to bed earlier and wake up earlier do better academically than those who stay up late, even if those night owls are spending that time doing homework.

To end this cycle of sleep deprivation and stress, the BSC recommends that students try setting a consistent time to go to sleep each night, regardless of leftover homework. And their other sleep tips are good for anyone, regardless of age — keep the temperature between 65 and 67 degrees, turn off the electronic devices before bed, make sure the mattress is comfy and reduce noise with earplugs or sound machines.

Related Articles

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Student Opinion

Should We Get Rid of Homework?

Some educators are pushing to get rid of homework. Would that be a good thing?

By Jeremy Engle and Michael Gonchar

Do you like doing homework? Do you think it has benefited you educationally?

Has homework ever helped you practice a difficult skill — in math, for example — until you mastered it? Has it helped you learn new concepts in history or science? Has it helped to teach you life skills, such as independence and responsibility? Or, have you had a more negative experience with homework? Does it stress you out, numb your brain from busywork or actually make you fall behind in your classes?

Should we get rid of homework?

In “ The Movement to End Homework Is Wrong, ” published in July, the Times Opinion writer Jay Caspian Kang argues that homework may be imperfect, but it still serves an important purpose in school. The essay begins:

Do students really need to do their homework? As a parent and a former teacher, I have been pondering this question for quite a long time. The teacher side of me can acknowledge that there were assignments I gave out to my students that probably had little to no academic value. But I also imagine that some of my students never would have done their basic reading if they hadn’t been trained to complete expected assignments, which would have made the task of teaching an English class nearly impossible. As a parent, I would rather my daughter not get stuck doing the sort of pointless homework I would occasionally assign, but I also think there’s a lot of value in saying, “Hey, a lot of work you’re going to end up doing in your life is pointless, so why not just get used to it?” I certainly am not the only person wondering about the value of homework. Recently, the sociologist Jessica McCrory Calarco and the mathematics education scholars Ilana Horn and Grace Chen published a paper, “ You Need to Be More Responsible: The Myth of Meritocracy and Teachers’ Accounts of Homework Inequalities .” They argued that while there’s some evidence that homework might help students learn, it also exacerbates inequalities and reinforces what they call the “meritocratic” narrative that says kids who do well in school do so because of “individual competence, effort and responsibility.” The authors believe this meritocratic narrative is a myth and that homework — math homework in particular — further entrenches the myth in the minds of teachers and their students. Calarco, Horn and Chen write, “Research has highlighted inequalities in students’ homework production and linked those inequalities to differences in students’ home lives and in the support students’ families can provide.”

Mr. Kang argues:

But there’s a defense of homework that doesn’t really have much to do with class mobility, equality or any sense of reinforcing the notion of meritocracy. It’s one that became quite clear to me when I was a teacher: Kids need to learn how to practice things. Homework, in many cases, is the only ritualized thing they have to do every day. Even if we could perfectly equalize opportunity in school and empower all students not to be encumbered by the weight of their socioeconomic status or ethnicity, I’m not sure what good it would do if the kids didn’t know how to do something relentlessly, over and over again, until they perfected it. Most teachers know that type of progress is very difficult to achieve inside the classroom, regardless of a student’s background, which is why, I imagine, Calarco, Horn and Chen found that most teachers weren’t thinking in a structural inequalities frame. Holistic ideas of education, in which learning is emphasized and students can explore concepts and ideas, are largely for the types of kids who don’t need to worry about class mobility. A defense of rote practice through homework might seem revanchist at this moment, but if we truly believe that schools should teach children lessons that fall outside the meritocracy, I can’t think of one that matters more than the simple satisfaction of mastering something that you were once bad at. That takes homework and the acknowledgment that sometimes a student can get a question wrong and, with proper instruction, eventually get it right.

Students, read the entire article, then tell us:

Should we get rid of homework? Why, or why not?

Is homework an outdated, ineffective or counterproductive tool for learning? Do you agree with the authors of the paper that homework is harmful and worsens inequalities that exist between students’ home circumstances?

Or do you agree with Mr. Kang that homework still has real educational value?

When you get home after school, how much homework will you do? Do you think the amount is appropriate, too much or too little? Is homework, including the projects and writing assignments you do at home, an important part of your learning experience? Or, in your opinion, is it not a good use of time? Explain.

In these letters to the editor , one reader makes a distinction between elementary school and high school:

Homework’s value is unclear for younger students. But by high school and college, homework is absolutely essential for any student who wishes to excel. There simply isn’t time to digest Dostoyevsky if you only ever read him in class.

What do you think? How much does grade level matter when discussing the value of homework?

Is there a way to make homework more effective?

If you were a teacher, would you assign homework? What kind of assignments would you give and why?

Want more writing prompts? You can find all of our questions in our Student Opinion column . Teachers, check out this guide to learn how you can incorporate them into your classroom.

Students 13 and older in the United States and Britain, and 16 and older elsewhere, are invited to comment. All comments are moderated by the Learning Network staff, but please keep in mind that once your comment is accepted, it will be made public.

Jeremy Engle joined The Learning Network as a staff editor in 2018 after spending more than 20 years as a classroom humanities and documentary-making teacher, professional developer and curriculum designer working with students and teachers across the country. More about Jeremy Engle

- EXPLORE Random Article

How to Avoid Homework Stress

Last Updated: March 28, 2019 References

This article was co-authored by Emily Listmann, MA . Emily Listmann is a private tutor in San Carlos, California. She has worked as a Social Studies Teacher, Curriculum Coordinator, and an SAT Prep Teacher. She received her MA in Education from the Stanford Graduate School of Education in 2014. There are 10 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been viewed 133,057 times.

Students of all kinds are often faced with what can seem like an overwhelming amount of homework. Although homework can be a source of stress, completing it can be a very rewarding and even relaxing experience if done in an organized and timely manner. Remember, homework is not intended as punishment, but is used to reinforce everything you’ve learned in class. Try to view it as a chance to sharpen your skills and understanding.

Managing Your Time

- Try to work earlier, rather than later, if possible. This way, you won’t be rushing to finish your work before bedtime.

- Find a time of day during which you can concentrate well. Some people work best in the afternoon, while others can concentrate better on a full stomach after dinner.

- Choose a time when you will have relatively few distractions. Mealtimes, times during which you have standing engagements, or periods usually used for socializing are not the best choices.

- Allow enough time to complete your work. Making sure the total time you allow yourself for homework is sufficient for you to complete all your assignments is crucial. [1] X Research source [2] X Research source

- Save an appropriate amount of time for projects considering your normal homework load.

- Estimate how much time you will need each day, week, and month depending on your usual workload. Allow yourself at least this much time in your schedule, and consider allotting a fair amount more to compensate for unexpected complications or additional assignments.

- Reserve plenty of time for bigger projects, as they are more involved, and it is harder to estimate how much time you might need to complete them.

- Get a day planner or a notebook to write down your homework assignments, and assign an estimated amount of time to each assignment. Make sure to always give yourself more time than you think you’ll need.

- Plan to finish daily homework every day, then divide up weekly homework over the course of the entire week.

- Rank assignments in due-date order. Begin on those assignments due first, and work your way though. Finishing assignments according to due-date will help you avoid having to hurry through homework the night before it must be handed in.

- Allow more time for more difficult subjects and difficult assignments. Each individual person will have their strong subjects—and those that come a little harder. Make sure you take into account which subjects are harder for you, and allow more time for them during your scheduling.

Working Hard at School and in Class

- If you’re too shy to ask questions, or don’t feel it’s appropriate to do so during class, write them down in your notebook and then ask the teacher or professor after class.

- If you don't understand a concept, ask your teacher to explain it again, with specifics.

- If you're having trouble with a math problem, ask the teacher to demonstrate it again using a different example.

- Remember, when it comes to learning and education, there are no bad questions.

- Pay attention to important terms and ideas. Make sure to note things your teacher stresses, key terms, and other important concepts.

- Write clearly and legibly. If you can’t read your handwriting, it’ll take you longer to reference your notes at home.

- Keep your notebook organized with dividers and labels. This way, you’ll be able to locate helpful information in a pinch and finish your homework quicker. [4] X Research source

- Get permission.

- Sit up front and close to the instructor.

- Make sure to label your recordings so you don't lose track of them.

- Try to listen to them that same day while everything is fresh in your mind.

- Work in class. If you finish a class assignment early, review your notes or start your homework.

- Study at lunch. If you have time at lunch, consider working on homework. You can do this leisurely by just reviewing what you’ll need to do at home, or you can just jump right into your work.

- Don't waste time. If you get to class early, use that time for homework. In addition, many schools let students go to the library during this unplanned time, and it's a great place to finish uncompleted assignments.

Doing Your Homework

- Get some fresh air

- Go for a short run

- Do push-ups

- Walk your dog

- Listen to music

- Have a snack

- Study groups break up the monotony of daily homework and make for a less stressful experience than trying to cram on your own.

- Note that each person should turn in individualized assignments rather than collaborating to find the answers.

Balancing Homework with Life

- AP or IB classes often have 2 or 3 times the amount of reading and homework as regular courses.

- Honors classes may have up to double the amount of work required as regular courses.

- College students need to consider whether they want to take the recommended course load (often 4 classes) or more. More classes might help you finish your degree sooner, but if you are juggling work and extracurricular activities, you might be overwhelmed. [8] X Research source [9] X Research source

- Rank your classes and activities in order of importance.

- Estimate (realistically) how long your academic and extracurricular activities will take.

- Figure out how much time you have overall.

- If you’ve over committed, you need to drop your lowest ranked class or activity.

- Make sure to reserve mealtimes for family, rather than working.

- Try to set aside the weekend for family, and work only if you need to catch up or get ahead.

- Don’t plan on working on holidays, even if you try, your productivity likely won’t be high.

- Pick a reasonable hour to go to sleep every night.

- Try to do your morning prep work like ironing clothes and making your lunch at night.

- Take a nap after school or after classes if you need. You’ll probably be able to do better work in less time if you are rested. [10] X Research source [11] X Research source

- If you’re in middle or high school, talk to your parents and your teachers about the issue and ask them to help you figure out a solution.

- If you’re a college student, reach out to your professors and advisor for help.

- If it takes you much longer to finish your homework than it takes other students, it may be due to a learning difference. Ask your parents to schedule a meeting with a learning specialist.

Community Q&A

- Ask for help when you need it. This is the biggest thing you should do. Don't worry if people think you're dumb, because chances are, you're making a higher grade than them. Thanks Helpful 2 Not Helpful 4

- Actually pay attention to the teacher and ask if you don't know how to do the work. The stress can go away if you know exactly what to do. Thanks Helpful 2 Not Helpful 2

- Recognize that some teachers get mad if you do separate homework assignments for different classes, so learn to be discreet about it. Thanks Helpful 3 Not Helpful 0

You Might Also Like

- ↑ http://www.webmd.com/parenting/features/coping-school-stress

- ↑ http://www.kidzworld.com/article/24574-how-to-avoid-homework-stress

- ↑ http://www.dartmouth.edu/~acskills/success/notes.html

- ↑ https://stressfreekids.com/10038/homework-stress

- ↑ http://www.huffingtonpost.com/rebecca-jackson/5-ways-to-relieve-homework-stress-in-5-minutes_b_6572786.html

- ↑ https://stressfreekids.com/11607/reduce-homework-stress

- ↑ https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/education/how-students-can-survive-the-ap-course-workload/2012/03/01/gIQA8u28qR_story.html

- ↑ http://www.usnews.com/education/high-schools/articles/2012/05/10/weigh-the-benefits-stress-of-ap-courses-for-your-student

- ↑ http://www.nationwidechildrens.org/sleep-in-adolescents

- ↑ https://www.google.com/?gws_rd=ssl#q=how+much+sleep+do+20+year+old+need

About this article

Reader Success Stories

Angelina Wiseman

Oct 12, 2016

Did this article help you?

Apr 17, 2017

- About wikiHow

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Your Health

- Treatments & Tests

- Health Inc.

- Public Health

School Stress Takes A Toll On Health, Teens And Parents Say

Patti Neighmond

Colleen Frainey, 16, of Tualatin, Ore., cut back on advanced placement classes in her junior year because the stress was making her physically ill. Toni Greaves for NPR hide caption

Colleen Frainey, 16, of Tualatin, Ore., cut back on advanced placement classes in her junior year because the stress was making her physically ill.

When high school junior Nora Huynh got her report card, she was devastated to see that she didn't get a perfect 4.0.

Nora "had a total meltdown, cried for hours," her mother, Jennie Huynh of Alameda, Calif., says. "I couldn't believe her reaction."

Nora is doing college-level work, her mother says, but many of her friends are taking enough advanced classes to boost their grade-point averages above 4.0. "It breaks my heart to see her upset when she's doing so awesome and going above and beyond."

And the pressure is taking a physical toll, too. At age 16, Nora is tired, is increasingly irritated with her siblings and often suffers headaches, her mother says.

Teens Talk Stress

When NPR asked on Facebook if stress is an issue for teenagers, they spoke loud and clear:

- "Academic stress has been a part of my life ever since I can remember," wrote Bretta McCall, 16, of Seattle. "This year I spend about 12 hours a day on schoolwork. I'm home right now because I was feeling so sick from stress I couldn't be at school. So as you can tell, it's a big part of my life!"

- "At the time of writing this, my weekend assignments include two papers, a PowerPoint to go with a 10-minute presentation, studying for a test and two quizzes, and an entire chapter (approximately 40 pages) of notes in a college textbook," wrote Connor West of New Jersey.

- "It's a problem that's basically brushed off by most people," wrote Kelly Farrell in Delaware. "There's this mentality of, 'You're doing well, so why are you complaining?' " She says she started experiencing symptoms of stress in middle school, and was diagnosed with panic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder in high school.

- "Parents are the worst about all of this," writes Colin Hughes of Illinois. "All I hear is, 'Work harder, you're a smart kid, I know you have it in you, and if you want to go to college you need to work harder.' It's a pain."

Parents are right to be worried about stress and their children's health, says Mary Alvord , a clinical psychologist in Maryland and public education coordinator for the American Psychological Association.

"A little stress is a good thing," Alvord says. "It can motivate students to be organized. But too much stress can backfire."

Almost 40 percent of parents say their high-schooler is experiencing a lot of stress from school, according to a new NPR poll conducted with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Harvard School of Public Health. In most cases, that stress is from academics, not social issues or bullying, the poll found. (See the full results here .)

Homework was a leading cause of stress, with 24 percent of parents saying it's an issue.

Teenagers say they're suffering, too. A survey by the American Psychological Association found that nearly half of all teens — 45 percent — said they were stressed by school pressures.

Chronic stress can cause a sense of panic and paralysis, Alvord says. The child feels stuck, which only adds to the feeling of stress.

Parents can help put the child's distress in perspective, particularly when they get into what Alvord calls catastrophic "what if" thinking: "What if I get a bad grade, then what if that means I fail the course, then I'll never get into college."

Then move beyond talking and do something about it.

Colleen pets her horse, Bishop. They had been missing out on rides together because of homework. Toni Greaves for NPR hide caption

Colleen pets her horse, Bishop. They had been missing out on rides together because of homework.

That's what 16-year-old Colleen Frainey of Tualatin, Ore., did. As a sophomore last year, she was taking all advanced courses. The pressure was making her sick. "I didn't feel good, and when I didn't feel good I felt like I couldn't do my work, which would stress me out more," she says.

Mom Abigail Frainey says, "It was more than we could handle as a family."

With encouragement from her parents, Colleen dropped one of her advanced courses. The family's decision generated disbelief from other parents. "Why would I let her take the easy way out?" Abigail Frainey heard.

But she says dialing down on academics was absolutely the right decision for her child. Colleen no longer suffers headaches or stomachaches. She's still in honors courses, but the workload this year is manageable.

Even better, Colleen now has time to do things she never would have considered last year, like going out to dinner with the family on a weeknight, or going to the barn to ride her horse, Bishop.

Psychologist Alvord says a balanced life should be the goal for all families. If a child is having trouble getting things done, parents can help plan the week, deciding what's important and what's optional. "Just basic time management — that will help reduce the stress."

- Children's Health

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Top 10 Stress Management Techniques for Students

Elizabeth Scott, PhD is an author, workshop leader, educator, and award-winning blogger on stress management, positive psychology, relationships, and emotional wellbeing.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Elizabeth-Scott-MS-660-695e2294b1844efda01d7a29da7b64c7.jpg)

Akeem Marsh, MD, is a board-certified child, adolescent, and adult psychiatrist who has dedicated his career to working with medically underserved communities.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/akeemmarsh_1000-d247c981705a46aba45acff9939ff8b0.jpg)

Most students experience significant amounts of stress. This can significantly affect their health, happiness, relationships, and grades. Learning stress management techniques can help these students avoid negative effects in these areas.

Why Stress Management Is Important for Students

A study by the American Psychological Association (APA) found that teens report stress levels similar to adults. This means teens are experiencing significant levels of chronic stress and feel their stress levels generally exceed their ability to cope effectively .

Roughly 30% of the teens reported feeling overwhelmed, depressed, or sad because of their stress.

Stress can also affect health-related behaviors. Stressed students are more likely to have problems with disrupted sleep, poor diet, and lack of exercise. This is understandable given that nearly half of APA survey respondents reported completing three hours of homework per night in addition to their full day of school work and extracurriculars.

Common Causes of Student Stress

Another study found that much of high school students' stress originates from school and activities, and that this chronic stress can persist into college years and lead to academic disengagement and mental health problems.

Top Student Stressors

Common sources of student stress include:

- Extracurricular activities

- Social challenges

- Transitions (e.g., graduating, moving out , living independently)

- Relationships

- Pressure to succeed

High school students face the intense competitiveness of taking challenging courses, amassing impressive extracurriculars, studying and acing college placement tests, and deciding on important and life-changing plans for their future. At the same time, they have to navigate the social challenges inherent to the high school experience.

This stress continues if students decide to attend college. Stress is an unavoidable part of life, but research has found that increased daily stressors put college-aged young adults at a higher risk for stress than other age groups.

Making new friends, handling a more challenging workload, feeling pressured to succeed, being without parental support, and navigating the stresses of more independent living are all added challenges that make this transition more difficult. Romantic relationships always add an extra layer of potential stress.

Students often recognize that they need to relieve stress . However, all the activities and responsibilities that fill a student’s schedule sometimes make it difficult to find the time to try new stress relievers to help dissipate that stress.

10 Stress Management Techniques for Students

Here you will learn 10 stress management techniques for students. These options are relatively easy, quick, and relevant to a student’s life and types of stress .

Get Enough Sleep

Blend Images - Hill Street Studios / Brand X Pictures / Getty Images

Students, with their packed schedules, are notorious for missing sleep. Unfortunately, operating in a sleep-deprived state puts you at a distinct disadvantage. You’re less productive, may find it more difficult to learn, and may even be a hazard behind the wheel.

Research suggests that sleep deprivation and daytime sleepiness are also linked to impaired mood, higher risk for car accidents, lower grade point averages, worse learning, and a higher risk of academic failure.

Don't neglect your sleep schedule. Aim to get at least 8 hours a night and take power naps when needed.

Use Guided Imagery

David Malan / Getty Images

Guided imagery can also be a useful and effective tool to help stressed students cope with academic, social, and other stressors. Visualizations can help you calm down, detach from what’s stressing you, and reduce your body’s stress response.

You can use guided imagery to relax your body by sitting in a quiet, comfortable place, closing your eyes, and imagining a peaceful scene. Spend several minutes relaxing as you enjoy mentally basking in your restful image.

Consider trying a guided imagery app if you need extra help visualizing a scene and inducting a relaxation response. Research suggests that such tools might be an affordable and convenient way to reduce stress.

Exercise Regularly

One of the healthiest ways to blow off steam is to get regular exercise . Research has found that students who participate in regular physical activity report lower levels of perceived stress. While these students still grapple with the same social, academic, and life pressures as their less-active peers, these challenges feel less stressful and are easier to manage.

Finding time for exercise might be a challenge, but there are strategies that you can use to add more physical activity to your day. Some ideas that you might try include:

- Doing yoga in the morning

- Walking or biking to class

- Reviewing for tests with a friend while walking on a treadmill at the gym

- Taking an elective gym class focused on leisure sports or exercise

- Joining an intramural sport

Exercise can help buffer against the negative effects of student stress. Starting now and keeping a regular exercise practice throughout your lifetime can help you live longer and enjoy your life more.

Take Calming Breaths

When your body is experiencing a stress response, you’re often not thinking as clearly as you could be. You are also likely not breathing properly. You might be taking short, shallow breaths. When you breathe improperly, it upsets the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide in your body.