AQA A-Level Psychology Past Papers With Answers

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

AQA A-Level Psychology (7182) and AS-Level Psychology (7181) past exam papers and marking schemes. The past papers are free to download for you to use as practice for your exams.

November 2021 (Labelled as June 2021)

- Download Past Paper : A-Level (7182)

- Download Mark Scheme : A-Level (7182)

November 2020 (Labelled as June 2020)

- Download Past Paper : AS (7181)

- Download Mark Scheme : AS (7181)

- Download Past Paper: A-Level (7182)

- Download Past Paper: AS (7181)

- Download Mark Scheme: A-Level (7182)

- Download Past Paper

- Download Mark Scheme

- AQA Model Answers Info

- Purchase AQA Model Answers

- Private Tuition

- Info + Contact

PAST PAPERS: RESEARCH METHODS: AQA A-LEVEL PSYCHOLOGY RESOURCES

Psychology aqa a-level (7182) unit 2: 7182/2.

Full model answers for all of these questions are available here

Sign up to the PsychLogic newsletter at the bottom of this page to download printable AQA A-level Psychology revision notes + AQA A-level Psychology revision guide + A-level Psychology revision tips + more...

The best way to revise Psychology A-level

THE SYLLABUS

METHODS, TECHNIQUES & DESIGN

- Primary and secondary data, and meta-analysis. Quantitative and qualitative data

- Aims, operationalising variables, IV’s and DV’s

- Hypotheses - directional and non-directional

- Experimental design - independent groups, repeated measures, matched pairs

- Validity – internal and external; extraneous and confounding variables; types of validity and improving validity

- Control – random allocation, randomisation, standardisation

- Demand characteristics and investigator effects

- Reliability; types of reliability and improving reliability

- Pilot studies

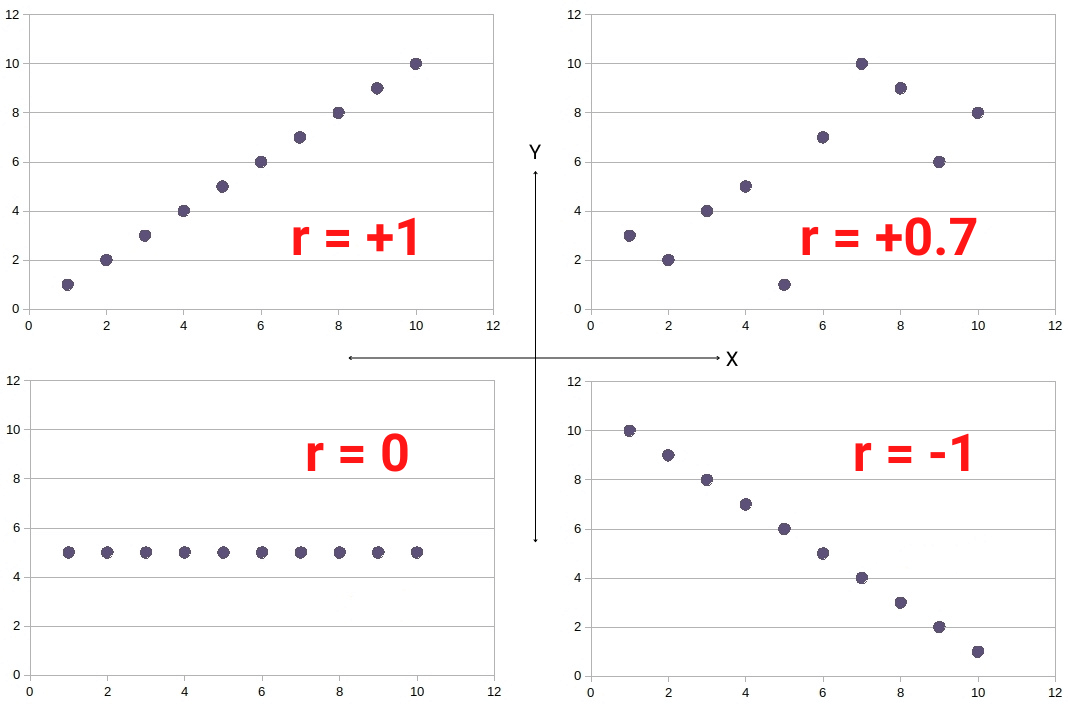

- Correlation analysis – covariables and hypotheses, positive/negative correlations

- Observational techniques – use of behavioural categories

- Self-report techniques – design of questionnaires and interviews

- Case studies

- Content analysis & thematic analysis

PARTICIPANTS; ETHICS; FEATURES OF SCIENCE & SCIENTIFIC METHOD; THE ECONOMY

- Selecting participants and sampling techniques

- The British Psychological Society (BPS) code of ethics and ways of dealing with ethical issues

- Forms and instructions

- Peer review

- Features of science: objectivity, empirical method, replicability and falsifiability, paradigms and paradigm shifts

- Reporting psychological investigations

- The implications of psychological research for the economy

DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS

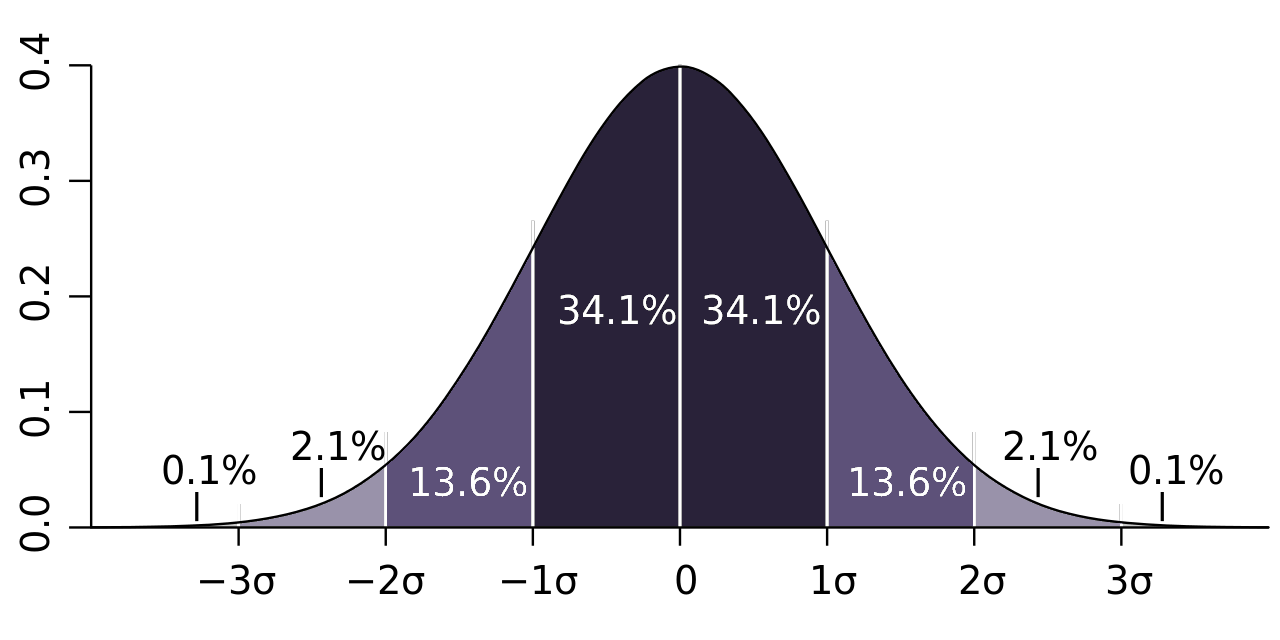

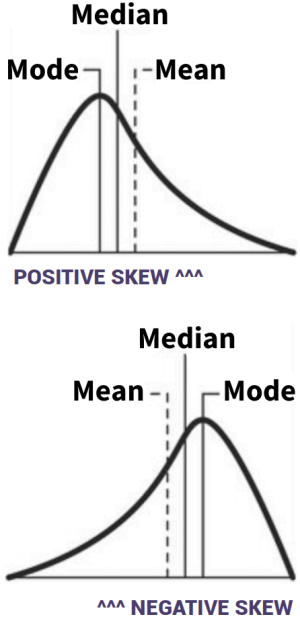

- Analysis and interpretation of quantitative data. Measures of central tendency - median, mean, mode. Calculating %’s. Measures of dispersion – range and standard deviation (SD)

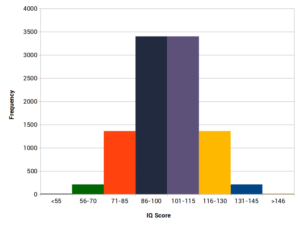

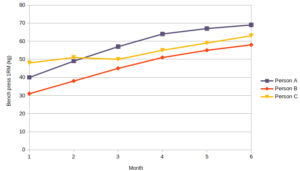

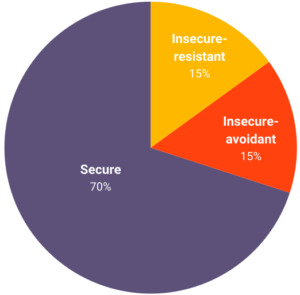

- Presentation and interpretation of quantitative data – graphs, histograms, bar charts, scattergrams and tables

- Analysis and interpretation of correlational data; positive and negative correlations and the interpretation of correlation coefficients

- Distributions: normal and skewed

INFERENTIAL STATISTICS

- Introduction

- Factors affecting choice of statistics test: Spearman’s rho, Pearson’s r, Wilcoxon, Mann-Whitney, related t-test, unrelated t-test, Chi-Squared test

- Levels of measurement – nominal, ordinal, interval

- Procedures for statistics tests

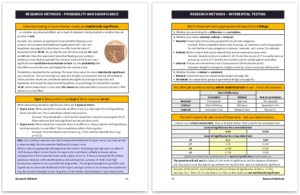

- Probability and significance: use of statistical tables and critical values in interpretation of significance; Type I and Type II errors

- Introduction to statistical testing: the sign test

>>>>>>>

SPECIMEN PAPER 1 ( Psychology A-level revision)

Read the item and then answer the questions that follow.

A psychologist wanted to see if verbal fluency is affected by whether people think they are presenting information to a small group of people or to a large group of people.

The psychologist needed a stratified sample of 20 people. She obtained the sample from a company employing 60 men and 40 women.

The participants were told that they would be placed in a booth where they would read out an article about the life of a famous author to an audience. Participants were also told that the audience would not be present, but would only be able to hear them and would not be able to interact with them.

There were two conditions in the study, Condition A and Condition B.

Condition A: 10 participants were told the audience consisted of 5 listeners.

Condition B: the other 10 participants were told the audience consisted of 100 listeners.

Each participant completed the study individually. The psychologist recorded each presentation and then counted the number of verbal errors made by each participant.

(a) Identify the dependent variable in this study. (2 marks)

(b) Write a suitable hypothesis for this study. (3 marks)

(c) Identify one extraneous variable that the psychologist should have controlled in the study and explain why it should have been controlled. (3 marks)

(d) Explain one advantage of using a stratified sample of participants in this study. (2 marks)

(e) Explain how the psychologist would have obtained the male participants for her stratified sample. Show your calculations. (3 marks)

(f) The psychologist wanted to randomly allocate the 20 people in her stratified sample to the two conditions. She needed an equal number of males in each condition and an equal number of females in each condition. Explain how she would have done this. (4 marks)

Mean number of verbal errors and standard deviations for both conditions

(g) What conclusions might the psychologist draw from the data in the table? Refer to the means and standard deviations in your answer. (6 marks)

(h) Read the item and then answer the question that follows.

The psychologist had initially intended to use the range as a measure of dispersion in this study but found that one person in Condition A had made an exceptionally low number of verbal errors.

Explain how using the standard deviation rather than the range in this situation, would improve the study. [3 marks]

(i) Name an appropriate statistical test that could be used to analyse the number of verbal errors in Table 1. Explain why the test you have chosen would be a suitable test in this case. [4 marks]

(j) The psychologist found the results were significant at p<0.05. What is meant by ‘the results were significant at p<0.05’? [2 marks]

(k) Briefly explain one method the psychologist could use to check the validity of the data she collected in this study. [2 marks]

(l) Briefly explain one reason why it is important for research to undergo a peer review process. [2 marks]

(m) Read the item and then answer the question that follows.

The psychologist focused on fluency in spoken communication in her study. Other research has investigated sex differences in non-verbal behaviours such as body language and gestures

Design an observation study to investigate sex differences in non-verbal behaviour of males and females when they are giving a presentation to an audience.

In your answer you should provide details of:

- The task for the participants

- The behavioural categories to be used and how the data will be recorded

- How reliability of the data collection might be established

- Ethical issues to be considered.

(Total 12 marks)

SPECIMEN PAPER 2 ( A-level Psychology revision)

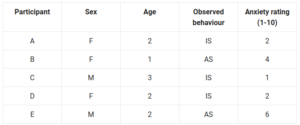

Researchers were interested in the spatial awareness skills of motorists. They decided to investigate a possible relationship between different aspects of spatial awareness. Motorists who had between ten and twelve years of driving experience and held a clean driving licence with no penalty points were asked to complete two sets of tasks.

Set 1: To follow a series of instructions and using a map, to identify various locations correctly. This provided a map reading score for each motorist with a maximum score of 20.

Set 2: To complete a series of practical driving tasks accurately. This involved tasks such as driving between cones, driving within lines and parking inside designated spaces. Each motorist was observed completing the Set 2 tasks by a single trained observer who rated each performance by giving the driver a rating out of 10.

The following results were obtained.

Table 1: The map reading scores and driver ratings of motorists

(a) Should the hypothesis be directional? Explain your answer. (2 marks)

(b) Write a suitable hypothesis for this investigation. (3 marks)

(c) Identify a suitable graphical display for the data in Table 1 and briefly explain why this display would be appropriate. (2 marks)

(d) Using the data in Table 1, comment on the relationship between the map reading scores and the driver rating scores of the participants. [3 marks]

(e) Briefly outline one problem of using a single trained observer to rate the participants’ driving skills in the practical task. Briefly discuss how this data collection method could be modified to improve the reliability of the data collected. (6 marks)

(f) The researchers decided to analyse the data using a Spearman’s rho test. Explain why this is a suitable choice of test for this investigation. (3 marks)

(g) After analysis of the data the researchers obtained a calculated value of r s = 0.808. Using the information in Table 2 above, what conclusion can the researchers draw about the relationship between the map reading and driving skills of the motorists? Explain your answer. [4 marks]

(h) Distinguish between a Type I error and a Type II error. (4 marks)

When the researchers looked at the data collected more closely they noticed possible gender differences in the results.

(i) What do the mean and standard deviation values suggest about the male and female performances in the investigation? (4 marks)

In a replication of the part of the study in which map reading skills were investigated, 20 men and 20 women completed the original map reading task and the researchers obtained the following data:

(j) The mean map reading score for both groups together was 12.23. What percentage of the male group scored above the mean score and what percentage of the female group scored above the mean score? Show your calculations. (4 marks)

(k) Using your answers to both 2 previous questions, comment on the performances of the male and the female participants in this study. (2 marks)

(l) Briefly explain one reason why it is important for research to be replicated. (2 marks)

(m) Imagine you have been asked to design a study to investigate possible gender differences in card sorting behaviours. You decide you will ask participants to sort a shuffled pack of playing cards into their suits of hearts, clubs, diamonds and spades. You decide you will time the participants as they do this using a stop watch.

Discuss the following aspects of this investigation:

- with reference to the card sorting task, explain how you would ensure that this is made the same task for all participants

- one methodological issue you should take into account when obtaining suitable participants for this study and explain how you would deal with this issue

- how you would ensure that the experience of your participants is ethical.

>>>>>>>

SPECIMEN PAPER 3 ( AQA A-level Psychology revision)

Following previous research indicating the social benefits of green space in urban areas, two psychology students decided to observe social behaviour in public spaces. They focused on two neighbouring towns, Greensville where most public spaces were planted with flowers and vegetables, and Brownton where most public spaces were paved with concrete.

The students compared the instances of considerate behaviours in the two towns.

Considerate behaviour categories included putting litter in the bin, having a dog on a lead and riding a bike with care.

The observations were carried out in four different areas of a similar size in each town on weekdays between the hours of 4.30pm and 6.00pm. The students worked together to ensure inter-observer reliability, recording each target behaviour whenever it occurred.

(a) Should the hypothesis for this research be directional or non-directional? Explain your answer. (2 marks)

(b) Before the observation could begin, the students needed to operationalise the behaviour category ‘riding a bike with care’.

Explain what is meant by operationalisation and suggest two ways in which ‘riding a bike with care’ could have been operationalised. (4 marks)

(c) The students thought that having a dog on a lead was a useful measure of considerate behaviour because it had face validity. Explain what is meant by face validity in this context. (3 marks)

(d) Identify and briefly outline two other types of validity in psychological research. (4 mark

(e) Identify the behaviour sampling method used by the students. Shade one box only.

- Time sampling

- Pair sampling

- Event sampling

- Target sampling

(f) Explain how inter-observer reliability could be ensured by working as a pair. (3 marks)

The students noted that overall more considerate behaviours occurred in Greensville than in Brownton.

(g) Calculate the ratio of considerate behaviours observed in Greensville to considerate behaviours observed in Brownton. Show your workings and present your answer in the simplest form. (3 marks)

(h) The students carried out a Chi-square test on their data. Explain why the Chi-square test was an appropriate test to use in this case. (3 marks)

(i) In order to interpret the results of the Chi-square test the students first needed to work out the degrees of freedom. They used the following formula.

Degrees of freedom (df) = (r–1) x (c–1)

r = number of rows and c = number of columns

Calculate the degrees of freedom for the data in Table 1. Show your workings.

(j) The calculated value of Chi-square was 6.20. Referring to Table 2 below, state whether or not the result of the Chi-square test is significant at the 0.05 level of significance. Justify your answer. (3 marks)

To be significant at the level shown the calculated value of Chi Square must be equal to or greater than the critical/table value

(k) In the discussion section of their report of the investigation the students wanted to further discuss their results in relation to levels of significance.

Write a short paragraph the students could use to do this. (4 marks)

(l) As a follow-up to their observation the students decided to interview some of their peers about inconsiderate behaviours in their 6th Form Centre. The interviews were recorded.

Explain how the students could develop their interview findings by carrying out a content analysis and why content analysis would be appropriate in this case. (3 marks

(m) Suggest one inconsiderate behaviour that the students might focus on in their content analysis. (1 mark)

(n) Design an experiment to investigate the effect of indoor plants on mood in office workers. For your measure of mood, you should devise a measure that would give data suitable for testing at the ordinal level of measurement.

- Design – include reference to the experimental design, variables and controls

- Materials/Apparatus – describe any special materials required

- Data analysis that could be used – include reference to descriptive and inferential analysis.

Justify your choices. (12 marks)

2017 ( AQA A-level Psychology revision guide)

A psychologist wanted to test whether listening to music improves running performance.

The psychologist conducted a study using 10 volunteers from a local gym. The psychologist used a repeated measures design. Half of the participants were assigned to condition A (without music) and half to condition B (with music).

All participants were asked to run 400 metres as fast as they could on a treadmill in the psychology department. All participants were given standardised instruction. All participants wore headphones in both conditions. The psychologist recorded their running time in seconds. The participants returned to the psychology department the following week and repeated the test in the other condition.

(a) Identify the type of experiment used in this study.

(b) Identify the operationalised dependent variable in the study. (2 marks)

The results of the study are given in Table 1 below.

Table 1. Mean number of second taken to complete the 400m run and the standard deviation for both conditions.

(c) Explain why a histogram would not be an appropriate way of displaying the means shown in Table 1. (2 marks)

(d) Name a more appropriate graph to display the means shown in Table 1. Suggest appropriate X (Horizontal) and Y (vertical) axis labels for your graph choice. (3 marks)

Name of graph

X axis label

Y axis label

(e) What do the mean and standard deviation values in Table 1 suggest about the participants’ performances with and without music? Justify your answer. (4 marks)

(f) Calculate the percentage decrease in the mean time it took participants to run 400 metres when listening to music. Show your workings. Give your answer to three significant figures. (4 marks)

The researcher used a directional hypothesis and analysed the data using a related t-test. The calculated value of t where degrees of freedom (df) = 9 was 1.4377. He decided to use the 5% level of significance.

Table 2. Table of critical values of t

Calculated value of t must be equal to or greater than the critical value in this table for significance to be shown.

(g) Give three reasons why the researcher used a related t-test in this study and, using Table 2, explain whether or not the results are significant (5 marks)

(h) What is meant by a Type II error? Explain why psychologists normally use the 5% level of significance in their research. (3 marks)

(i) Identify one extraneous variable that could have affected the results of this study. Suggest why it would have been important to control this extraneous variable and how it could have been controlled in this study. (3 marks)

(j) The report was submitted for peer review and a number of recommendations were advised.

Describe the process and purposes of peer review. (6 marks)

People’s perception of how they spent their time at the gym is often not very accurate. Some spent more time chatting than on the treadmill. A psychologist decides to observe the actual behaviour of an opportunity sample of gym users at a local gym.

(k) Explain why it is more appropriate for the psychologist to use an observation than a questionnaire in this case. (3 marks)

(l) Design an observational study to investigate how people spent their time at the gym.

In your answer you will be awarded credit for providing appropriate details of

- Type of observation with justification

- Operationalised behaviour categories

- Use of time and/or event sampling with justification

- How reliability of data collection could be assessed.

2018 ( A-level Psychology resources)

A psychologist was reading an article about typical dream themes in adults.

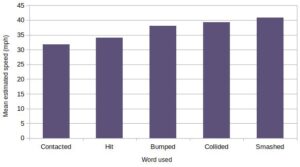

Figure 2 shows the main dream themes identified in the article.

Figure 2 Main dream themes

(a) Using Figure 2, estimate the percentage of dreams that were reported to be about being chased. Shade one box only. [1 mark]

A 4%

B 12%

C 27%

D 42%

The psychologist was interested in finding out whether dream themes differed between box males and females, particularly in terms of social interaction. She decided to conduct a pilot study. Twenty undergraduate students (8 male and 12 female) volunteered for the study. For a six-week period the students were interviewed at 9 am each morning when they arrived at university. Interviewers, who did not know the purpose of the study, carried out and recorded the dream interviews.

(a) What is meant by a pilot study? Explain one possible reason why the psychologist decided to conduct a pilot study for this investigation. [3 marks]

(b) The interviews produced qualitative data. What is meant by qualitative data? Give one strength of collecting qualitative data in this study. [2 marks]

(c) What are investigator effects? Suggest one way in which they could have been minimised during the dream interviews. [3 marks]

Another researcher, who did not know the purpose of the study, carried out a content analysis of the interview data.

(d) Explain how this content analysis could have been conducted. [4 marks]

The psychologist wanted to assess the reliability of the content analysis.

(e) Explain how the reliability of the content analysis could be assessed. [4 marks]

When comparing the data for males and females, the psychologist found that there was a difference in the proportion of friendly and aggressive social interactions. This is shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Percentage of friendly and aggressive social interactions in dreams reported by males and females

A total of 375 dreams reported by males included social interaction.

(f) Use the data in Table 2 to calculate how many of these dreams reported by males were classified as aggressive. Show your workings. [2 marks]

(g) Draw a suitable graphical display to represent the data in Table 2 box. Label your graph appropriately. [4 marks]

The psychologist decided to conduct an experiment to investigate the effect of watching box horror films before going to bed.

A volunteer sample of 50 university students consented to take part in the experiment.

The 50 students were randomly split into two groups. Group 1 watched a horror film before going to bed each night for the first week then a romantic comedy before going to bed each night for the second week. Group 2 watched the romantic comedy in the first week and the horror film in the second week.

When the students woke up each morning, each student received a text message that asked if they had had a nightmare during the night. They could respond ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

(h) Write a brief consent form that would have been suitable for use in this experiment. The consent form should:

- include some detail of what participants might expect to happen

- refer to ethical issues

- be in an appropriate format/style

(i) The psychologist proposed a directional hypothesis.

Write a directional hypothesis for this experiment. [3 marks]

The psychologist used a repeated measures design in this experiment.

(j) Explain why it was important to use a repeated measures design in this case. [2 marks]

The psychologist used counterbalancing in this experiment.

(k) Explain why it was appropriate to use counterbalancing in this experiment. [2 marks]

(l) Explain how the box psychologist could have randomly split the sample of 50 students into the two groups. [3 marks]

The psychologist collated the responses of all the participants over the two-week period and calculated the mean and standard deviation for each condition.

Table 3: Mean number of nightmares reported and the standard deviation for each condition

(m) What do the mean and standard deviation values in Table 3 suggest about the effect of the type of film watched on the occurrence of nightmares? Justify your answer. [4 marks]

The psychologist found that the difference in the number of nightmares reported in the two conditions was significant at p<0.05.

(n) Explain what is meant by ‘significant at p<0.05’ in the context of this experiment. [2 marks]

(o) The psychologist was concerned about the validity of the experiment.

Suggest one possible modification to the design of the experiment and explain how this might improve validity. [3 marks]

2019 ( AQA A-level Psychology resources)

(a) Which of the following does reliability refer to?

Shade one circle only. [1 mark]

A The accuracy of the data

B The consistency of the data

C The levels of the data

D The validity of the data

(b) Which of the following is not a role of peer review in the scientific process?

A To determine whether to award research funding

B To ensure only significant results are published

C To make sure research has high validity and reliability

D To retain the integrity of psychological research

(c) Give one reason why it is important for scientific reports to include a referencing section? [1 mark]

It was recently reported in a newspaper that time spent playing team sports increases happiness levels. A researcher was keen to find out whether this was due to participating in a team activity or due to participating in physical activity, as he could not find any published research on this.

The researcher used a matched-pairs design. He went into the student café and selected the first 20 students he met. Each student was assigned to one of two groups.

Participants in Group A were requested to carry out 3 hours of team sports per week. Participants in Group B were requested to carry out 3 hours of exercise independently in a gym each week. All participants were told not to take part in any other type of exercise for the 4-week duration of the study.

All participants completed a happiness questionnaire at the start and end of the study. The researcher then calculated the improvement in happiness score for each participant.

(d) Which of the following is correct?

A Groups A and B are conditions of the dependent variable and happiness is the independent variable.

B Groups A and B are conditions of the independent variable and happiness is the dependent variable.

C Groups A and B are the controls and happiness is the experimental condition.

D Groups A and B are the experimental conditions and happiness is the control.

(e) Would a directional or non-directional hypothesis be more suitable for the researcher to use? Explain your answer. 2 marks]

(f) Write a suitable hypothesis for this experiment. [3 marks]

(g) Identify the type of sampling method used in this experiment. Explain one limitation of using this sampling method in this study. [3 marks]

(h) Identify one variable on which participants should be matched in this matched-pairs design. Explain how the researcher could assign matched participants to either Group A or Group B. [4 marks]

(i) Explain one strength of using a matched-pairs design rather than a repeated-measures design. [2 marks]

The results of the study are given in Table 2 below.

Table 2 Improvement in happiness scores

The researcher decided to use the Sign Test to see whether there was a significant difference in the improvement in the scores between the two groups at the 5% level of significance.

(j) Calculate the value of S in this study. Show your workings. [2 marks]

Significance is shown if the calculated value of S is equal to or less than the critical value.

(k) Explain whether or not there was a significant difference in the improvement in the scores between the two groups. Use your answer to Question 22 and Table 3. [2 marks]

The validity of the data was questioned when the researcher presented his results. The researcher explained that he chose to use the happiness questionnaire because it had high concurrent validity.

(l) Explain what it means for a test to have high concurrent validity. [2 marks]

The questionnaire had high concurrent validity.

Validity was still a concern because the researcher knew which participants were in each experimental group.

(m) Explain how this could have affected the validity of the study. [4 marks]

(n) Using your answer to Question m, suggest one way in which the researcher could modify the study to improve the internal validity of the study? Justify your answer. [4 marks]

A psychology teacher read the researcher’s study on sport and happiness. She considered whether setting group tasks could improve her students’ level of happiness. She decided to conduct an independent groups experiment with 30 students taking A-level Psychology using the same happiness questionnaire.

(o) Suggest an appropriate statistical test the psychology teacher could use to analyse the data. Justify your choice of test. [4 marks]

(p) Design an independent groups experiment that the psychology teacher could conduct.

- the aim of the experiment

- identification and manipulation of variables including details of the task

- controls to minimise the effects of extraneous variables

- data handling and analysis – use of descriptive statistics and/or data presentation.

Justify your design choices. [12 marks]

2020 ( A-level Psychology notes)

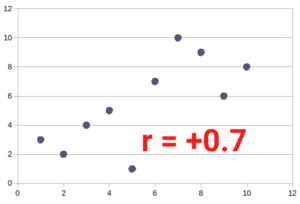

A study into the relationship between recreational screen time and academic achievement was conducted. Students were asked to self-report the number of hours spent watching TV, playing on their mobile phones or video games (daily recreational screen time) and their end-of-year test performances (academic performance).

The results of the study are shown in Figure 2.

(a) In which section(s) of a scientific report would you expect to find reference to the results/findings of the investigation?

A The abstract and the results sections only

B The abstract, the discussion and the results sections only

C The results and the discussion sections only

D The results section only

(b) Which of the following correlation co-efficients best describes the data represented in Figure 2?

A –0.80

B –0.25

C +0.25

D +0.80

(c) Identify the type of graph shown in Figure 2 and explain why this is an appropriate graph to use for the data collected. [3 marks]

(d) Explain why it would not be appropriate for the researchers to conclude that increased recreational screen time reduces academic performance. [2 marks]

A psychologist reads a review of a meta-analysis confirming the relationship between recreational screen time and academic performance.

(e) What is meant by the term meta-analysis? [2 marks]

The psychologist decided to design an experiment to test the effects of recreational screen time on children’s academic performance.

The psychologist randomly selected four schools from all the primary schools in her county to take part in the experiment involving Year 5 pupils. Three of the four schools agreed to take part. In total, there were 58 pupils whose parents consented for them to participate. The 58 pupils were then randomly allocated to Group A or Group B.

For the two-week period of the experiment, pupils in Group A had no recreational screen time. Pupils in Group B were allowed unrestricted recreational screen time. At the end of the experiment all pupils completed a 45-minute class test, to achieve a test score.

(f) Complete Table 1 by ticking the statement that best describes the population and the sample in the psychologist’s experiment.

Place one tick in each column. [2 marks]

(g) Briefly explain why a directional hypothesis would be most suitable for this experiment. [1 mark]

(h) Write an appropriate hypothesis for this experiment. [3 marks]

The results obtained from the experiment are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2 Descriptive statistics for the test performance scores for Group A and Group B

(i) Using the data in Table 2, explain how the distribution of scores in Group A differs from the distribution of scores in Group B. [4 marks]

(j) What do the mean and standard deviation values in Table 2 suggest about the effect of the recreational screen time on test performance? Justify your answer. [4 marks]

(k) The psychologist wanted to test the statistical significance of the data.

Identify the most appropriate choice of statistical test for analysing the data collected and explain three reasons for your choice in the context of this study. [7 marks]

One criticism of the study is that the pupils were not matched on their typical recreational screen time.

(l) Explain how the psychologist could have matched pupils on their typical recreational screen time across the experimental conditions. [4 marks]

(m) Identify one other variable for which the psychologist could have matched the pupils. Explain how this might have affected the test performance if it was not controlled. [2 marks]

The feedback from one of the schools was that recreational screen time affected pupils’ social interactions. The psychologist decided to investigate this further by using an observation of social interaction during playtime at the school.

(n) Design the observation to investigate pupils’ social interaction in the playground.

In your answer you will be awarded credit for providing appropriate details of:

- type of observation, with justification

- choice of time sampling or event sampling, with justification

- dealing with one relevant ethical issue

- assessing reliability of the data through inter-observer reliability.

2021 ( AQA A-level Psychology notes)

A researcher placed an advert in a university psychology department asking for third year students to participate in a sleep experiment.

Each student had a sleep tracker watch to wear at home for the two-week study. Each morning they were asked to open the sleep tracker app to view their sleep quality data on their mobile phones. The students were unaware that the sleep data they could see on their phones had been manipulated by the researcher. Over the two weeks of the study, each student saw that he or she had had poor sleep quality for seven random nights of the experiment and good sleep quality for the remaining nights.

Every morning, after viewing the sleep data, each student completed a questionnaire about the previous night’s sleep. One of the questions asked the students to rate how well rested they felt, on a scale from 1–10, after the previous night’s sleep. Apart from this, students were asked to continue their normal everyday activities.

(a) Which of the following best describes the experimental method used in this study?

Shade one box only. [1 mark]

A Field experiment

B Laboratory experiment

C Natural experiment

D Quasi-experiment

(b) Write a directional hypothesis the researcher might use for this study. [3 marks]

(c) Which of the following best describes the sampling method used in this study?

A Opportunity sampling

B Stratified sampling

C Systematic sampling

D Volunteer sampling

(d) Explain one strength and one limitation of using this sampling method in this study. [4 marks]

The researcher collected quantitative data about how well rested the students felt.

(e) Explain one strength of collecting quantitative data in this study. [2 marks]

One ethical issue in this study is deception, as the students were unaware that the sleep data they could see on their phones had been manipulated by the researcher.

(f) Explain one way in which the researcher might deal with the deception in this study. [2 marks]

Apart from the question about how well rested the students felt, the researcher’s questionnaire contained nine other questions. The responses to these questions were not analysed.

(g) Explain one reason why the researcher decided to include these additional questions on the questionnaire. [2 marks]

(h) Explain one limitation of assessing sleep quality using a rating scale of 1–10. [2 marks]

The researcher believed that the actual number of hours slept by the students could have affected the results of the study.

(i) Suggest one other extraneous variable that could have affected the results of this study. Explain why it would have been important to control this extraneous variable and how it could have been controlled in this study. [4 marks]

In a follow-up study, the researcher investigated whether there was a correlation between the number of hours slept and how well rested the students felt.

The researcher randomly selected 18 participants from first-year students at the university.

On the day of the study, each student participant was asked, ‘How many hours did you sleep last night?’ They then had to rate on a scale of 1 to 5 how well rested they felt.

The researcher hypothesised that there would be a positive correlation between the two co-variables.

(j) Outline one reason why it was appropriate to conduct a correlation rather than an experiment in this case. [2 marks]

(k) Describe how the researcher could have used random sampling to obtain the students for this study. [3 marks]

The researcher used Spearman’s rho statistical test to analyse the data from this study.

(l) Explain why Spearman’s rho was a suitable test for this study. Refer to the description of the study in your answer. [4 marks]

The researcher chose to use the 5% level of significance and the calculated correlation coefficient for the Spearman’s rho test was 0.395

(m) Identify the appropriate critical value from Table 1. Explain your choice. [4 marks]

(n) Explain whether the researcher’s hypothesis should be accepted. Refer to the critical value identified in Question 21 in your answer. [2 marks]

(o) Explain why the researcher decided to use the 5% level of significance rather than the 1% level in this study. [2 marks]

When the researcher compared the calculated and critical values of rho, he began to wonder if he might have made a Type II error.

(p) Explain what is meant by a Type II error in the context of this study. [2 marks]

(q) Discuss features of science. Refer to one or more examples of psychological research in your answer. [8 marks]

2022 ( A-level Psychology revision notes)

A controlled observation was designed to compare the social behaviours of pre-school children of working parents and pre-school children of stay-at-home parents. The sample consisted of 100 children aged three, who were observed separately. Half of the children had working parents and the other half had stay-at-home parents.

The observation took place in a room which looked like a nursery, with a variety of toys available. In the room, there were four children and one supervising adult. Their behaviour was not recorded.

Each child participant was brought into the room and settled by their parent. The parent then left to sit outside. Each child participant’s behaviour was observed covertly for five minutes while they played in the room.

The observation was conducted in a controlled environment and a standardised script was used when the children and their parents arrived.

(a) Explain why the researcher used a controlled observation and a standardised script in this study. [4 marks]

(b) Identify one limitation of controlled observations. [1 mark]

The researcher used two trained observers to record the social behaviours of each child during the observation.

(c) Give two behavioural categories that the observers could have used in the observation to assess the pre-school children’s social behaviour. Explain why your chosen categories are appropriate. [4 marks]

(d) Describe how the observers could use time sampling to record the social behaviour of each child during the five-minute period. [4 marks]

(e) Explain one strength and one limitation of using time sampling for this observation. [4 marks]

(f) Explain how the reliability of the controlled observation could be assessed through inter-observer reliability. [4 marks]

The data from the observation was summarised by converting the number of agreed observations into a total social behaviour score for each child.

The researcher then conducted a statistical test to identify whether there was a significant difference between the social behaviour scores for the children of stay-at-home parents and those of working parents.

(g) Identify an appropriate statistical test that the researcher could use to analyse the social behaviour scores in this study. Explain three reasons for your choice in the context of this study. [7 marks]

(h) Explain one reason why collecting quantitative data could reduce the validity of this study. [2 marks]

The findings of this study might have implications for the economy.

(i) Explain one or more possible implications of this study for the economy. [3 marks]

This study was written up as a scientific report.

(j) Describe features of the abstract section in a scientific report. [3 marks]

A new TV programme has been developed to increase positive social behaviours in pre-school children.

There is a proposal to carry out an experiment to compare the effects of the new TV programme and an existing TV programme, on positive social behaviours in pre-school children.

A sample of 500 pre-school children and their parents is available for the experiment. The parents have given consent for their children to take part in this experiment.

The experiment will take place over an 8-week period. Data on the children’s social behaviours will be gathered from the parents using a self-report method.

(j) Design the experiment to investigate whether watching the new TV programme leads to an increase in positive social behaviours in the children, compared with watching the existing TV programme.

In your answer you will gain credit for providing appropriate details of the following:

- the type of experimental design, with justification

- a self-report method of data collection, with justification

- how to control one extraneous variable, with justification as to why this would need to be controlled.

- Account details

AQA GCSE Psychology Research Methods

This section provides revision resources for AQA GCSE psychology and the Research Methods chapter. The revision notes cover the AQA exam board and the new specification. As part of your GCSE psychology course, you need to know the following topics below within this chapter:

- AQA Psychology

- Research Methods

We've covered everything you need to know for this research methods chapter to smash your exams.

- The latest AQA GCSE Psychology specification (2023 onwards) has been followed exactly so if it's not in this resource pack, you don't need to know it.

- We've provided practice questions at the end to help you get better with this topic.

- Completely free for schools , just get in touch using the contact form at the bottom.

- Teachers can print and distribute this resource freely in classrooms to aid students and teaching.

- Instant download, no waiting.

Formulation of Testable Hypotheses

For the formulation of testable hypotheses, the psychology specification states you need to know following:

- Null hypothesis and alternative hypothesis.

A hypothesis is simply a formal and testable statement of the relationship between two variables that is to be tested through experimentation. In psychology, as well as other sciences, we use them as part of the scientific method.

The hypothesis is not strictly speaking a prediction and should not be used in the future tense i.e. “this will happen”. It is only at the end of the study that the researcher decides whether the research evidence supports the hypothesis or not.

There are different types of hypotheses used in psychology, however, the main ones that crop up frequently are:

- Directional hypotheses

- Non-directional hypotheses

- Null hypotheses

- Alternative hypotheses

For GCSE Psychology and the AQA specification, we need to know about null hypotheses and alternative hypotheses .

What is a Null Hypothesis?

A null hypothesis is a general statement that the observed variables will have no impact as there is no relationship between them. This hypothesis assumes that any difference observed is due to sampling or experimentation errors.

An example of a null hypothesis for a hypothetical scenario is “watching television before bed has no impact on how well you sleep”

What is an Alternative Hypothesis?

The alternative hypothesis would be a prediction that one variable will affect the other.

An example would be “watching scary movies before bed affects how fast you fall asleep”. The alternative hypothesis does not specify the direction of the outcome, merely that there will be an effect.

Formulating Hypotheses

Once you know enough about hypotheses, you need to consider how to apply them. When conducting research, most of the time the experiment comes from a simple or vague idea we wish to test.

Here’s an example: does music affect peoples ability to learn?

This is rather a vague question and to turn it into a testable experiment, we need to be able to operationalise the two key variables; music and learning .

These two variables are then known as the independent variable and dependent variable – often referred to as the IV and DV for short. More information is given on them below.

Hypotheses are then easier to form, a suitable one for this experiment would be an alternative hypothesis such as:

- “ The presence or absence of music has an effect on the score in a learning test ”

A null hypothesis for this example would simply be:

- “The presence of music has no effect on the score in a learning test”

Type of Variables

For the different types of variables, the GCSE psychology specification states you need to know the following:

- Independent variable, dependent variable, extraneous variables.

There are 3 different types of variables we need to know about which are:

- The independent variable (IV)

- The dependent variable (DV)

- Extraneous variables.

Independent Variable

An experiment will look to measure the effect of one variable on another. These two variables have special names, which are the independent variable and dependent variable.

The independent variable is what researchers manipulate in order to test its effect on the dependent variable (the outcome). Let’s use the example mentioned earlier about music and learning to illustrate this: We are conducting an experiment to see if music affects the ability of students to learn. In this case, the independent variable (IV) we will be manipulating is music.

Within the context of an experiment, we may simply have two conditions where one group is exposed to music while another group is not while engaging in some learning activity. We would then compare the findings to assess the results.

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable (DV) is the outcome or effect we are measuring within the study. So using the example above, the dependent variable would be how well the students are able to learn with or without music. This may be measured in a number of ways (taking a memory test for example or quiz).

So to clarify – the independent variable is what we change and the dependent variable is the outcome we then measure .

A good way to remember the difference is to think of it like this:

- The dependent variable “depends” on what's being changed (the independent variable).

- Another way would be to remember that “we measure the effect of the IV on the DV”.

If you remember that the independent variable (IV) always comes first, you should be able to recall that the dependent variable (DV) is then the outcome. These are just two simple ways of remembering the difference between the IV and DV but feel free to use what works for you.

Extraneous Variable

The extraneous variable is a third variable that may unknowingly be affecting the outcome of the study (the DV).

We conduct experiments to measure the effect of the IV on the DV but sometimes extraneous variables are actually the cause of the changes. They can be seen as “nuisance variables” that affect the study and make it difficult to know whether it is the IV that affects the DV.

Let’s use that example mentioned earlier about how music may affect a students ability to learn. We may conduct this experiment and find that music improves learning as the students who listened to the music performed better.

We may, therefore, conclude music improves students ability to learn, however, what if it was actually a third variable affecting the results which is unaccounted for? (an extraneous variable).

Perhaps we find that the students who performed the best were those with prior knowledge of the questions in the test?. The extraneous variable could then be argued to be prior knowledge participants had that we have not accounted for or could control.

Looking into the study we could perhaps argue the extraneous variable may be the intelligence of participants from one group to another that is affecting the outcome. It may be that some participants in one group were more educated and therefore better problem solvers, and this is an extraneous variable that is affecting the dependent variable (outcome).

With research studies you will be presented, you can almost always find arguments to highlight extraneous variables in some form. It is handy to get into the habit of recognising these different forms as they prove useful in critically analysing studies and topping up your points with further evaluation marks, especially if you go on to study A-level psychology.

Sampling Methods

- Random sampling

- Opportunity sampling

- Systematic sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Strengths and weaknesses of each sampling method

- Understand principles of sampling as applied to scientific data.

This section of AQA GCSE psychology requires you to know about 4 different sampling methods and their strengths and weaknesses.

Sampling methods are merely the different strategies researchers use to get participants for their studies. In any psychological research study, there is usually a target population, which is the group of individuals the researcher is interested in. The aim of the researcher is to try and take a representative sample from this target population using a sampling method. The goal is to gain a representative sample that then allows the researcher to make generalisations across the whole population, based on the findings of this sample.

The four sampling methods you are required to know about are:

Random Sampling

Random sampling involves the researcher identifying members of the target population, numbering them and then attempting to draw out the required number of people for their study.

The selection of participants can be done in a randomised way such as drawing out numbers from a hat if the sample size is small or having a computer randomly select the participants if the sample size is large.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Random Sampling

- Random sampling has the benefit of being more unbiased as all members of the target population have an equal chance of being selected for the study. This would mean that the sample is likely to be more representative of the target population making more valid generalisations possible from the research findings.

- Random sampling also means there is less chance that researchers can influence the results as they have no say as to who is picked. This reduces the impact of investigator effects which means the findings may have more validity.

- However, even despite this, it is still possible for the researcher to end up with an unbalanced and biased sample by chance, particularly if the sample size is too small.

- Gathering randomised samples can also be time-consuming, as attempting to gather enough willing participants from the target population takes a considerable amount of time and effort.

Opportunity Sampling

Opportunity sampling is a form of sampling method that means you ask those who are around you and most easily available , that represent the target population, to participate in the study. This may involve asking those around you in your class, school or people walking in the street for their involvement.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Opportunity Sampling

- The main benefit of opportunity sampling is it is one of the fastest and easiest ways to gather participants for a study when compared to other sampling methods.

- Opportunity samples have a greater chance of being biased because the sample is drawn from a very narrow part of the target population. For example, if you selected participants at school, your sample is likely to consist of mostly students and the behaviours they display in the study may not generalise to adults. Participants may also try to “help” the researcher in a way that would support the hypothesis so the results may be unreliable and invalid.

- With opportunity sampling methods, it is possible the researcher can influence those selected as the process is not randomised. The researcher may select the people they think will support their hypothesis, so investigator effects is a potential hindrance.

Systematic Sampling

Systematic sampling involves selecting every “nth” member of the target population . An example of this would be if the researcher decided that “n” will be “5”, every 5th person in the target population is selected as a participant.

This is still unbiased as the researcher has no influence as to who is picked and it is technically not a “random sample” either as not everyone gets an equal opportunity to be selected (it is only the person 5 positions away). Be sure not to confuse this with the random sampling method due to this slight difference; just remember that there is a fixed systematic way for selection that determines this to be a systematic sample.

Strengths and weaknesses of systematic sampling

- A strength of the systematic sampling method is that it is a simple way for researchers to gather participants and there is little risk of research bias influencing this. Therefore the participants gathered should, in theory, be representative and unbiased which should lead to more reliable results.

- A weakness, however, is participants gathered could still be unrepresentative and biased due to chance selection. This would make the results unreliable when re-tested.

- Another weakness of systematic sampling is you need a bigger sample size to be able to filter out participants based on the “nth” selection. If you require 100 participants for a study and picked them based on every 10 participants, you would need 1000 participants to filter through. Therefore gathering participants for a study based on systematic sampling methods can be very time-consuming.

Stratified Sampling

Stratified sampling is the most complex of the sampling methods and it is most often used in questionnaires. Sub-groups (or strata) within the population are identified (e.g. boys and girls or age groups: 10-12 years, 13-15 years etc) and then participants are gathered from each strata in proportion to their occurrence in the population . The selection of participants is generally done using a random technique.

For example, in a school, there are several subgroups such as teachers, support staff, students and other staff. If the teachers made up 10% of the whole school’s population, then 10% of the sample must be teachers. This is then repeated for each sub-group.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Stratified Sampling

- A major strength of using stratified sampling techniques is that they are very representative of the target population. This means the findings should have high reliability and validity to make generalisations to the target population.

- A major weakness of using stratified sampling is that it is very time-consuming to identify the subgroups, select necessary participants and attempt to get a proportionate sample involved in the study. Therefore this form of sampling method is extremely difficult to execute and can be impractical.

Volunteer Sampling

A volunteer sample consists of people that have volunteered to take part in the study . Volunteers can be gathered in a number of ways such as putting an advert out on the newspaper, internet or some media outlet to try and gather people to take part.

Volunteers may put themselves forward to be part of the study but they may not necessarily be told the aim of the study or what they are really being tested in. For example, Milgram’s shock study gathered volunteers who agreed to take part but did not necessarily know what they were being tested on (obedience).

Strengths and Weaknesses of Volunteer Sampling

- A strength of using volunteer sampling is participants should be willing to give their informed consent to be a part of the study. The people that tend to volunteer tend to be those motivated to take part in the study.

- Volunteer sampling can also be a fast and efficient way of gathering research participants. Instead of having to search for volunteers, an advert could be placed to gather participants based on the traits/characteristics the researcher requires.

- A weakness of using volunteer sampling is the people that tend to volunteer may be a biased sample that are not representative of the target population. For example, volunteers are already motivated to engage in the research (volunteer bias) and more motivated than those that do not and this can influence the outcome of the study in some way.

Designing Research

This section on designing research for GCSE psychology and research methods is quite extensive and requires you to know about quite a few different aspects of designing psychological research studies.

The topics you need to know for research methods include:

Independent group design

- Repeated measures design

- Matched pairs design

- Strengths and weaknesses of each design

- Laboratory experiments

- Field and natural experiments

Questionnaires

- Case studies

- Observation studies

- Strengths and weaknesses of each research method and types of behaviour for which they are suitable.

An independent group design is the simplest to understand and conducted with participants involved in the study usually divided into two subgroups .

One group will take part in the experimental condition (with the independent variable introduced), while the other group would not be exposed to this and form the control group for comparison.

Let’s use the example we mentioned earlier with a study that measures the effects of music on learning.

In an independent group design, one group of participants would be measured on their ability to learn with music being played while the other group would be tested on their learning ability without music.

The results (dependent variable) are then compared between the two groups to measure the effects.

If the results are significantly different then researchers may conclude that this is because of the independent variable, which in our case would be music affecting learning ability.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Independent Group Design

- A strength of using independent group designs is there are no order effects that can invalidate the results, as participants only take part in one of the conditions. Order effects are apparent in experiments where repeated measure designs are used and this involves participants learning or improving from their experience of having to do the experiment more than once. This does not happen in independent group designs which can give more valid results.

- Independent group designs are beneficial as the materials or apparatus can usually be used across both the experimental condition and the control group (minus the independent variable being manipulated or introduced as required). This makes setting up independent group designs far easier than other experimental conditions due to saving time.

- Another strength of independent group designs is that participants are less likely to display demand characteristics. Demand characteristics are when participants change their own behaviour as they figure out (or think they do) the purpose of the study. The participants may then display behaviour that is different in response which can invalidate findings. Demand characteristics are less likely in independent group designs as participants are only exposed to one condition and they don’t have the opportunity to learn or adjust their behaviour in another condition (as they cannot compare).

- A weakness of independent group designs is that differences between the experimental condition and control group may be due to participant variables, such as individual differences between the two groups, rather than the independent variable. Just by probability or chance, one group may be smarter than another or have individual characteristics that make them more able (or less able) for the condition they are exposed. This would then be a confounding variable that affects the results. Using the music example mentioned previously, the group that performs best (whether its the group exposed to music or not) may do so simply because they have more educated or intelligent people than the other condition.

- Another criticism of using independent group designs in experiments is that you need to gather more participants. For example, you need a large enough sample to be exposed to the experimental condition to make generalisations but you then need to gather this number again for the control group condition. Using our example earlier, if we wanted to test how music affects people’s ability to learn and we gather 50 people, we need another 50 people for the control condition that is exposed to no music. Gathering too few participants increases the risks of individual differences being the difference in results while gathering a large number requires more time, effort and resources.

Repeated Measures Design

A repeated measures design sees all the gathered participants of the study being exposed to both conditions of the experiment.

Referring to our music and learning scenario (once again!), we would have a group of 50 participants that would first be exposed to the experimental condition whereby they attempt to learn with music present and then they would attempt to learn without music.

The results would then be compared between the conditions to assess what impact the IV had on the DV. In experiments where there were numerous different conditions, the same participants would be used across them while exposed to different independent variables.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Repeated Measures Design

- A major strength of repeated measure designs is that they require less effort to gather participants as they use the same people across the different experimental conditions. Therefore setting up the experiment tends to be faster compared to group designs such as independent measures where you would require double the amount of participants to cross-compare against.

- Another strength of using repeated measure designs is participant variables are eliminated. This is because the same people are used across the different conditions and they are comparing against themselves directly. This means there is less chance of individual differences influencing the results.

- A weakness of using repeated measure designs is that there is a high risk of order effects affecting the validity of findings. As participants are required to do multiple tasks across different conditions, there is the risk that participants may improve as they repeat the experiments. For example, if they were tested on their learning ability while music was played in one condition, when they are tested without music, the experience and practice gained from the first condition may see them improve. Researchers may then incorrectly view this improvement as due to the independent variable (IV) rather than order effects.

- Another criticism of using repeated measures is you need to create multiple different tasks or materials between the conditions. For example, you could not use the same content for participants to memorise from one condition to another in a memory test experiment. You would need to create content that was judged to be similar in difficulty which in itself would be a subjective measure. For example, having participants memorise 20 “easy” words with similar syllables in one condition, would require a researcher to spend significant time and effort in creating another set of similar words for another condition.

- There is a higher risk of demand characteristics when using repeated measure designs. This is because participants may be able to guess the purpose of the study (if it is intentionally obscured to improve the validity of findings) and then adjust their behaviour accordingly. This is more likely to happen as the same participants are used across the different conditions and they may notice the different setups and the purpose of the study. This may lead to invalid findings from the behaviour that is observed.

Matched Pairs Design

A matched pairs design involves gathering participants and testing them prior to them taking part in the study on certain characteristics . The tests allow them to be matched in pairs with someone who is deemed to have similar qualities as to them which may be relevant to the study.

The pairs may be identified as Pair Aa or Pair Bb etc.

In conducting a matched pairs design research study, one pair will take part in one experimental condition while their matched partner/pair is exposed to another experimental condition.

The results are then compared by the researcher between the conditions and treated as if they were gathered from one individual despite coming from two individuals.

Within psychological research, the most ideal matched pairs participants tend to be identical twins as they account have identical biology (as they are similar) and potentially very similar personality factors too.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Matched Pairs Design

- One strength of using matched pairs designs in research is they reduce participant variables which can affect the results. This is because the people are paired up together based on similar traits that are relevant to the study.

- Another strength of using matched pairs is that there are no order effects, unlike repeated measure design studies. This is because everyone does the experiment once and have no opportunity to learn from their previous attempts.

- Matched pairs designs can re-use the same materials/apparatus across the pairs as everyone will only be exposed to them once. This makes the setup of the experiment easier as researchers do not have to create unique set-ups across the two groups which can be time-consuming.

- A weakness of using matched pairs design is matching people on key variables is time-consuming and not always successful. Attempting to find people who can be matched requires an initial large sample to filter through and this can take a very long time to do.

- It is difficult to match people based on personality variables or filter out individual differences for certain. You can generally only match people based on fixed traits such as gender (sex), age, height etc, however, personality factors may be what determine differences in the experiments. Therefore matched pair designs can produce invalid results that are not the result of the independent variable.

Laboratory Experiments

Laboratory experiments are experiments that are conducted in a controlled setting , usually a research laboratory where participants are aware of being observed and part of a study.

Laboratory experiments tend to have high internal validity because researchers can control all the variables so the main differences between the experimental condition and control group are only the independent variable whose effect is being monitored. This allows researchers to more confidently assume that any differences between the conditions are due to the independent variable.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Laboratory Experiments

- A major strength of laboratory experiments is they have high validity. This means that researchers can be confident to a higher degree that what they are measuring is in fact due to the effect of the independent variable because this is the only difference between the experimental condition and control group.

- Another strength of using a laboratory setup is this limits the role of extraneous variables from influencing the results as researchers have complete control of the environment. This means unaccounted for outside influences are limited and makes drawing cause and effect between the IV and DV more reliable. Laboratory experiments can be checked for reliability as they are easier to replicate. Due to the artificial setup of the experiments (being in a laboratory setting), other researchers can recreate the experiment exactly to check the results for reliability. This can be harder to do with other setups.

- A weakness of using laboratory experiments is they lack ecological validity. This is because the setup of the experiment is artificial and in a completely controlled environment and the results gathered in the lab, may not generalise to real-world situations due to their contrived setup. Therefore laboratory experiments tend to lack ecological validity as the setup involved to test behaviour may not occur similarly in real life e.g. testing memory ability and learning in a lab setup is unlikely to be how people learn with or without music being present – or using a film clip to test eyewitness testimony is not realistic.

- Participants in laboratory setups may display demand characteristics and adjust their behaviour due to the contrived setup and being aware that they are being observed. Therefore the behaviour observed may lack validity as it may not be indicative of how people are likely to behave in the real world if they think they are not being observed or under supervision. Participants may, therefore, behave how they think researchers want them or what would be deemed normal with others watching, not necessarily what they would actually do.

Field Experiments

A field experiment is conducted in a more natural or everyday environment , unlike the laboratory experiment where the behaviour being measured is more likely to occur.

The field experiment can be conducted anywhere in real-world settings with researchers manipulating an independent variable to measure its impact on the dependent variable. A field experiment can include confederates that participants are unaware of also being involved to test their response in the field setting.

One key difference between a field experiment compared to a laboratory experiment, are participants may not be aware of being observed or studied. This is in an attempt to generate more realistic behaviour or responses from them that can generalise to real-world settings.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Field Experiments

- A strength of using field experiments is they are high in ecological validity as the setup and environments are more realistic. This is thought to increase more realistic responses from participants as they are not aware always aware of being observed (unlike lab settings). The argument here is field experiments have higher internal validity and the behaviours from participants can then be generalised to the wider population.

- A weakness of using field experiments is they are at higher risk of extraneous variables influencing the behaviour of participants. Researchers, therefore, have less control and cannot say with as much certainty that the behaviour they observed was in fact due to the independent variable or not.

- Another criticism of field experiments is they are difficult to replicate. Participants may be members of the public with personality factors that influence the results which are unaccounted for and the environment itself may be difficult to recreate in order to test the study for reliability in its findings. Therefore replication and reliability become an issue for field experiments.

- Another weakness of using field experiments is they raise ethical issues in regards to informed consent. This is because participants may be unaware of being observed or part of a study and this raises ethical concerns. On the other hand, this may also provide us with more realistic and valid results without demand characteristics being a potential confounding variable.

Natural Experiments

A natural experiment is conducted when ethical or practical reasons to manipulate an independent variable (IV) are not possible. It is therefore said that the IV occurs 'naturally'.

The dependent variable (DV), may however, be tested in a laboratory, for example, the effects of institutionalisation in some form, which may occur naturally due to imprisonment or disruption of attachment through the care system and how it may affect psychological development such as intellect or emotional development.

Another good example of a natural experiment is the study by Charlton et al. (2000) which measured the effects of television. Prior to 1995, the people of St. Helena, a small island in the Atlantic had no access to TV however it's arrival gave the researchers to examine how exposure to western programmes may influence their behaviour. The IV in this case was the introduction of TV which was not controlled by researchers and something they took advantage of would be practically difficult to control. The DV was measures of pro or anti-social behaviours that were assessed through the use of questionnaires, observations and psychological tests.

These types of experiments would either impractical or unethical to implement and therefore cases where this occurs naturally due to normal circumstances may be examined through natural experiments.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Natural Experiments

- One major weakness of natural experiments is the lack of control. It is more difficult to control extraneous variables which makes it difficult to establish causality.

- A strength of natural experiments is they are high in ecological validity. Due to the 'real world' environment, the results relate to everyday behaviour and can be generalised to other settings.

- Another strength of natural experiments is they often produce no demand characteristics as the participants are unaware of the experiment. Therefore the behaviour observed is more likely to be realistic and indicative of behaviour that can be generalised across wider populations.

- A weakness of natural experiments is they are difficult to replicate to double check the findings. As the conditions are never exactly the same, it becomes difficult to establish reliability in such experiments which then affects validity as causality cannot be determined.

- Participants are often not aware of being observed or taking part in natural experiments and this raises ethical issues, in particular, informed consent. They may not wish to take part or be monitored and this is another weakness of natural experiments, although they may be debriefed after the experiment and given the option of giving consent to use the data collected from them.

One way psychologists find out about peoples behaviour is to quite simply ask them through the form of interviews.

Interviews involve a researcher in direct contact with the participant and this could either be face to face or via phone/video call. The vast majority of interviews involve a questionnaire that the researcher records the responses on at the time of the interview. There are different forms of interviews used which vary in structure and we will look at specifically structured and unstructured interviews for GCSE psychology.

Structured Interviews

Structured interviews involve all participants being asked the same pre-set questions in the same order . The researcher is unable to ask additional questions outside of this.

The questions are often closed questions that require a yes or no response , or they can be open questions that simply require the researcher to record the participant’s response.

Open questions can be questions that begin with who, what, where, when, why and how.

These force a participant to explain their answers beyond simply saying yes or no.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Structured Interviews

- Structured interviews can be replicated far more easily than unstructured interviews as the questions are all pre-set. This helps in testing the reliability of research findings to check for consistency and validity in the conclusions drawn.

- A criticism/weakness of using structured interviews is they can be incredibly time consuming and require skilled researchers. People’s responses can also be affected by social desirability bias.

- Structured interviews gather quantitative data but lack qualitative data. When participants can only answer yes or no, this does not tell us why they think or respond this way which may be more important to understand behaviour.

Unstructured Interviews

In unstructured interviews, participants are free to discuss anything freely . The interviewer may devise new questions as the interview progresses or on the previous answers given, to explore further.

With unstructured interviews, each participant is likely to be asked different sets of questions within the interview. The questions asked in unstructured interviews may be a mix of open and closed questions.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Unstructured Interviews