- Rights & Reproductions

Kirk Collection Box A Brown University Library Providence, RI 02912 Holly Snyder

Developed & hosted by Center for Digital Scholarship Box A Brown University Library Providence, RI 02912 [email protected]

Temperance and Prohibition Era Propaganda: A Study in Rhetoric

By leah rae berk, beginnings: the minister and the physician team up.

In 1805, Benjamin Rush, a physician from Philadelphia, wrote an essay titled "The Effects of Ardent Spirits Upon Man". Rush's writing reflected the changing attitudes towards distilled alcohol at the time, especially among the US medical community. Rush's article drew upon ideas from a century earlier; at the beginning of the eighteenth century, medical practitioners began taking a more scientific approach to medicine. Scientists and doctors like Rush felt that the American public needed to be made aware of the health hazards inherent in alcohol consumption. Rush's argument against the consumption of ardent spirits was not only scientific, but also moral. At the end of his essay, Rush described the moral evils that resulted from the use of distilled spirits such as fraud, theft, uncleanliness and murder (Runes 339). Not long after Rush began writing about alcohol's detrimental effects on moral and physical health, he began a correspondence with the Boston Minister Jeremy Belknap. The physician and the minister soon became collaborators, using a mixture of scientific and moral claims in their fight against the consumption of alcoholic beverages.

The teaming up of the minister and the physician is emblematic of a century of rhetoric surrounding alcohol use and abuse in America. For over a century, Americans argued for abstinence from alcohol using a combination of scientific and moral reasons. What made Rush and Belknap's writing compelling and persuasive for many Americans? Why did later propaganda continue to use Rush and Belknap's two-fold argument against alcohol consumption? In this paper I will address these questions by discussing the rhetorical methods used in Temperance and Prohibition Era propaganda.

Anti-liquor Propaganda: A Study in Rhetoric

W. J. Rorabaugh, author of the 1979 book The Alcoholic Republic, wrote "Temperance reformers…flooded America with propaganda" (196). Rorabaugh cited the American Tract Society as one example: by 1851 the Society had distributed nearly five million temperance pamphlets (196). Pamphlets and propaganda were an essential aspect of the American antiliquor crusade, from the Temperance Movement through the Prohibition Era. Although these publications came in a variety of forms and styles, they all used two fundamental rhetorical techniques: logos and pathos. Logos is an appeal to logic; it includes scientific evidence, statistics, facts and other provable forms of information. Rush's use of scientific evidence in "The Effects of Ardent Spirits Upon Man" is an example of logos. A subcategory of logos is ethos or credibility. Not only should facts be provable, they must also come from a trustworthy and reliable source.

The second rhetorical technique employed by anti-liquor propaganda is pathos or appeals to emotion. The final part of Rush's essay dealing with morals and value judgments is based in pathos. Both logos and pathos played an important role in Temperance and Prohibition era propaganda, although ultimately, pathos proved to be the most widely used rhetorical method. Temperance and Prohibition era propaganda appealed to emotion through religious language, drawing upon the prevalent morals and values of the times. Both the Temperance Movement and Prohibition Era coincided with periods of intense religious fervor in the US. These religious revivals were steeped in Puritan moral codes which in turn served as the basis for the underlying ideology of antiliquor propaganda.

Temperance, Prohibition and the Puritans: A Brief History

Widespread religious fervor was a central feature of the Temperance and Prohibition eras. In the early nineteenth century, a religious revival known as the Second Great Awakening took the nation by storm (284). As James Morone wrote in his recent book, Hellfire Nation: The Politics of Sin in American History, "With preachers announcing that the millennium lay at hand, men and women began to swear off hard spirits; the yearning for perfection drew them until they were pledging total abstinence" (284). Many of the original Temperance societies had religious affiliations, like the evangelical American Temperance Society which was founded in 1826. Ten years later, at the evangelical American Temperance Society's height, one out of every ten Americans was a member (Morone 284).

Roughly a century later, in the 1910s, there was conservative religious revival in the United States. The religious movements of the Prohibition Era promoted a back to basics approach with a clear, narrow definition of what it meant to be a faithful, observant Christian. Protestant fundamentalists warned of the approaching millennium and the Second Coming of Christ and criticized "the nation's slack morals, 'creampuff' religions" and "'godless social service nonsense'" (Morone 335). Fundamentalist preachers like Billy Sunday told Americans that "the path to heaven ran through a literal reading of the Bible" (335).

Prohibition provided political backing and legitimacy for the religious revivals of the early twentieth century. While critics scoffed at the fundamentalists' stance on the coming millennium and interpretations of the bible, calling them backwards and extreme, Christian fundamentalists held their ground regarding their anti-drinking crusade. According to Morone, "Prohibition offered them [fundamentalists] their one link to national authority, the one public commitment to resisting moral decay" (337).

The morals and values that the religious revivals of the Temperance and Prohibition Eras promoted were steeped in Puritan ideology. Who were the Puritans? What were their fundamental beliefs?

Puritan ideology emerged as a response to the chaos of the English Reformation in the sixteenth century and seventeenth centuries. The original Puritans criticized the corruption in the Church of England and demanded a return to religious purity. Critics mocked these people, calling them "Puritans," and the name stuck.

The Puritans were among the original English settlers of North America; their first fleet arrived in Massachusetts in 1630. According to James Morone, "No aspect of the Puritan world is more often recalled than the notion of a mission, an errand in the wilderness sealed by a covenant with God" (35). The mission of the Early American Puritans hinged upon the concepts of individual and communal responsibility. Individuals controlled their final destinies: salvation for the righteous and eternal damnation for the sinners, however, the Puritan covenant held the entire community responsible for sinners in this life. God would punish all, saint and sinner alike, with disease, drought, famine and other misfortunes if a community did not reform its sinners. How could individuals and communities achieve success and salvation? According to the Puritans, the answer lay in education, discipline and hard work. Puritans defined the home as the primary place of instruction and saw parents as the most important moral models and instructors for children. Industriousness was a virtue with positive outcomes in this life and the afterlife. The Puritans' emphasis on the importance of hard work developed into what it commonly known as the "Protestant work ethic" (Morone 15). The Early American Puritan values of individual and communal salvation, hard work and the proper education of children are constant themes in Temperance and Prohibition Era propaganda.

Types of Propaganda

I found five major categories of Temperance and Prohibition Era propaganda: scientific pamphlets, religious pamphlets, posters, children's pamphlets and the fifth category, songs and poems. Using examples of these five forms of propaganda, I will discuss how Temperance and Prohibition Era propaganda used logos and pathos and why these rhetorical techniques were effective.

Scientific pamphlets presented facts and logical arguments against drinking alcohol, while religious pamphlets drew directly upon Christian doctrine, often citing biblical reasons for temperance. Although the terms scientific and religious seem to translate directly in logos and pathos, both types of propaganda used a mixture of rational and emotional appeals to promote abstinence from alcohol.

The scientific pamphlets claimed proven, scientific evidence and practical advice as the basis for their arguments. Titles such as "Alcohol: Practical Facts for Practical People" and "Answers to Favorite Wet Arguments," both from the early 1900s, reinforced the idea that these pamphlets contained factual, objective truth. Most pamphlets also established their ethos or credibility by citing the research and conclusions of experts, including doctors and scientists. The names of the associations distributing these pamphlets, such as the Scientific Temperance Federation of Boston, added to this air of scientific credibility.

Scientific pamphlets also found truth in numbers, using statistics to prove that alcohol was harmful to individuals and society. Pamphlets like "The Cost of Beer (1880s)" and "A Way to Make Money - And a Better Way (early 1900s)" discussed the personal and social expenses of drinking. First they appealed to logos, using statistical evidence. These pamphlets calculated the cost of alcohol, from the price per gallon to the cost of yearly consumption in cities like New York. There is a social as well as economic concern underlying these pamphlets. For example, "The Cost of Beer" addressed pathos by claiming that alcohol consumption leads to noise, broils, stupidity and drunkenness.

The underlying message of many of the scientific pamphlets was that an individual must know all the facts in order to make an informed decision. Yet, the information provided in these pamphlets pointed to only one viable option: temperance. To further the idea that abstinence was obviously the one true answer, a number of scientific temperance pamphlets had rhetorical questions as titles, such as these pamphlets from the early 1900s: "Do you want to be efficient?" "Do you want to be powerful?" and "Do you want a better rating?" Who could say no to these questions? These titles in the form of rhetorical questions likely piqued readers' interest, and, as in the case of "The Cost of Beer," these pamphlets intertwined logical, moral and emotional appeals.

The three pamphlets "Do you want to be efficient?" "Do you want to be powerful?" and "Do you want to a better rating?" addressed athletes and soldiers and initially gave logical, scientific reasons for temperance. The first reason was that alcohol is unhealthy. "Do you want to be efficient?" quoted a noted European psychiatrist who said that "Alcohol in all forms and doses is a poison." Reasons regarding the health problems resulting from alcohol drew upon a variety of scientific fields including psychology, human biology, neuroscience and medicine. These reasons led to the same conclusion: alcohol interferes with mental and physical processes, hurting the body and putting the drinker at a disadvantage. For example, one of the section headings of "Do you want a better rating?" read "Mere Physical Fitness Is Not All" and included the following quotations:

Physical fitness is a farce without self-control, judgment, and discretion, which are the three qualities of mind first to be dulled by and made incompetent by the use of alcohol. - Dr. Haven Emerson

One of the effects of alcohol is to interfere with the coordination of nerve and muscle. It has been repeatedly found that moderate amounts of alcohol interfere with skilled actions which depend on this co-ordination, such as rifle shooting and typing speed. - Dr. E. H. Derrick, M.D.

These quotations not only bring up the health reasons for temperance but also a second reason: abstainers are more industrious and productive. This is another form of logos which uses practical, rather than scientific, knowledge. While the scientific evidence was impressive because it drew upon information and resources that may otherwise have been inaccessible to many readers, these more practical arguments were compelling because they were familiar, appealing to a deeply-ingrained value, the Protestant work ethic.

Like "The Cost of Beer," these three pamphlets addressed pathos by discussing social as well as physical health, an argument which hearkened to the Puritan idea of social welfare. The pamphlet "Do you want to be powerful?" stated:

Experiment shows that drinking but one small bottle of beer or one glass of wine may impair a man's driving capacity… Practically all the hit-run fatal accidents are caused by drunken drivers, says Frank A. Goodwin, Massachusetts Registrar of Motor Vehicles.

This common sense reasoning seems to be an appeal to logic: drinking interferes with one's ability to drive. Individual safety, however, was not the primary concern. The underlying message of this quotation was to alert drivers that their drinking could have harmful effects on others. The example the quotation uses, hit-run accidents, is an appeal to pathos, because it conjures up the image of an innocent victim who is left injured while the driver speeds away. The implication is that people who drink and drive are irresponsible and hurt others, clearly disregarding the Puritan value of concern and consideration for members of one's community.

Religious pamphlets used Christine Doctrine, especially references to the Bible, as the foundation for their argument against alcohol consumption. Pamphlets like "The Holy Bible and Drink" and "Christian Temperance Catechism" (both from the early 1900s) quoted passages from the bible that warned against the evils of drinking. Directly quoting the bible was taken from the Puritan tradition where "emphasis is nearly always on the Bible, which they [the Puritans] saw in sharp contrast to tradition and to merely human ideas and usages" (Emerson 46). "The Holy Bible and Drink" presented twenty frequently asked questions about alcohol consumption from "What about 'one will not hurt you'?" to "What about drunkards being saved?" (2) and a list of pro-temperance answers in the form of quotations from the bible. "Christian Temperance Catechism" took a more step by step approach, using a series of questions and answers which drew on Christian Doctrine and sometimes included quotations from the scriptures. It began with the simplest and most innocuous seeming question and answer: "What is temperance? The proper control of appetite" (1). The questions and answers become more specific and emotionally charged throughout the pamphlet, ending with question and answers like "How can we work successfully against intemperance? By learning and by showing others how the use of intoxicants ruins soul and body" (8). Although these pamphlets followed a logos structure with logical arguments citing evidence from an established source, i.e. the bible, their underlying messages appealed to pathos. For example, "Christian Temperance Catechism" mentioned alcohol as a major source of suffering in society, both spiritual and physical. According to this pamphlet, American society suffered more from intemperance than all other forms of sin and claimed alcohol was a poison and "the cause of three fourths of all of the disease and proverty [sic] and sorrow and crime in our land" (2).

Not all Religious pamphlets utilized a logos format to fight temperance. The early twentieth century pamphlet "Don't Unwittingly Join The Enemy's Forces" is a clear appeal to pathos. Taken from an address given by Bishop Nicholson of the Methodist Episcopal Church, this pamphlet draws upon the Puritan tradition of preaching. The Puritans placed great emphasis on preaching and most "insisted that 'human authorities' have no place in sermons" (Emerson 45). Religious leaders supporting the Temperance movement, like Bishop Nicholson, saw the fight against intemperance as a crusade, literally a holy war. The authority justifying and supporting this fight was not mere human beings, but God.

In his address Bishop Nicholson appealed to deeply held American values and Puritan morals, describing intemperance as a threat to democracy and morality. Nicholson, like many Temperance leaders, described the struggle against liquor as a second American revolution; first Americans freed themselves from the British, now they must free themselves from alcohol. This argument drew upon the American value of liberty and Puritan morals concerning individual and communal responsibility and salvation.

As in a crusade, there was a clearly defined enemy in Nicholson's address. Nicholson not only criticized his opposition, the "wets" or anti-Temperance supporters, he vilified them. Nicholson inspired pathos by describing those who protested temperance as hateful, unprincipled and criminal men with unworthy motives. His argument was passionate and urgent. Not only was the fight against intemperance "the greatest struggle since the Civil War for the effectuation of Democracy" (2), it was a "life and death struggle with the greatest single evil of the ages…the most unprincipled, the most unscrupulous, and the most Satanic forces possible to conceive" (5).

Following in the tradition of Puritan preaching, Nicholson explained that the fight against intemperance was not merely a human endeavor, but God's mission: "God expects every man and every woman to do his or her duty…" (5) He conflated divine and earthly aspirations, saying that people can take part in God's mission by voting against pro-liquor legislation. Nicholson then took his appeal to pathos a step further, claiming that those who do not actively fight intemperance were supporting the enemy, (hence the title of the pamphlet "Don't Unwittingly Join the Enemy's Forces") and therefore neglecting their responsibilities as American Patriots and Christians. He criticized voter apathy, describing those who do not vote as "criminal and unpatriotic" (5), because by not voting these people were effectively giving their vote to the enemy.

Although some religious pamphlets did contain appeals to logos in their structure or actual arguments, the overarching rhetorical technique in this form of propaganda was pathos. Religious pamphlets evoked emotional responses by appealing to people's deeply held religious values and patriotic sentiments.

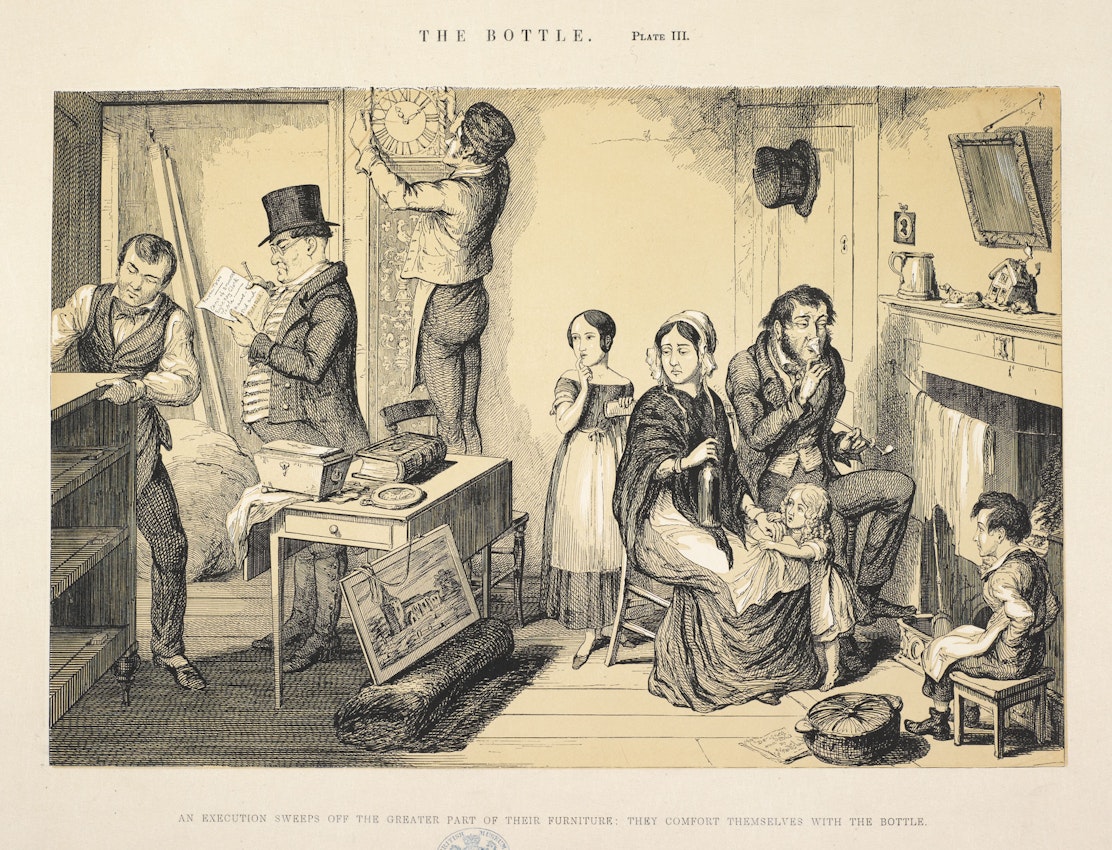

In many ways, Temperance and Prohibition Era posters offered a condensed version of the scientific and religious pamphlets, presenting their most striking and compelling arguments through images and sound bytes. Many of the posters took the Benjamin Rush approach, showing scientific and logical evidence to prove that alcohol consumption was detrimental to both body and soul.

Many posters referred to scientific studies and statistical information, citing medical and scientific experts for ethos. Like the titles of scientific pamphlets (ex. "Alcohol: Practical Facts for Practical People"), the headings of the posters purported indisputable information. Poster headings like "Deaths, Defect, Dwarfings in the Young of Alcoholized Guinea Pigs," "Death Rate From Various Diseases in Drinkers and General Class" and "Insurance Records Show that Drink Shortens Life 11%" with their graphs and charts hardly seem debatable. Despite their scientific and factual claims, many of the underlying messages of these posters were steeped in Puritan morality and appeals to pathos.

Temperance Era posters hinted both at the importance of responsible parenting and the Protestant work ethic, both deeply held Puritan values. A number of posters described how children of alcoholic parents suffered developmentally, both physically and emotionally, citing statistics and scientific studies as proof. Some described how parents who drink have a higher rate of defective children: "Defective Children Increased with Alcoholization of Fathers," "Drinkers' Children Developed More Slowly," "Hand in Hand: Feeblemindedness and Alcoholism: More alcoholism found in parents of Feebleminded than those of Normal Children" and "Child Death Rate Higher in Drinkers' Families." Others depicted the psychological problems drinking caused children: "Drink the Largest Cause of Unhappy Homes in Chicago," "Children in Misery, Parent's Drink to Blame in at Least Three Cases Out of Every Four" and "Drink Burdens Childhood."

Temperance and Prohibition Era posters described alcohol as the source of society's individual and social problems. Alcohol was the cause of laziness, inability to concentrate and other impediments to the ideals of success and the Protestant work ethic as noted in the posters: "Drink Impaired Scholarship," "The Better Chances of the Sober Workman," "Alcohol Impairs Muscle Work" and "Daily Drinking Impaired Memory." Like the scientific pamphlets, these posters used charts, percentages, results from studies and quotations from scientific and medical experts.

Still other posters were more explicitly moralizing, like the following poster which drew upon the Puritan value of care for others:

DRINK MAKES ONE MORE LIABLE TO ACCIDENT WHAT THE ACCIDENT INSURANCE COMPANY SAYS: "A man whose nerves have been made unsteady by a recent debauch or by the habitual use of alcohol, should not be permitted to operate dangerous machinery or to carry on dangerous work. He endangers not only his own life, but the lives of others."

The last line, "He endangers not only his own life, but the lives of others," is italicized, the implication being that individuals must care about the welfare of their fellow human beings.

A number of Temperance and Prohibition Era posters, like a number of the religious pamphlets, used a logos format to make a pathos appeal. These posters contained graphs and statistical information, presenting moral claims as factual information, such as "Alcoholism and Degeneracy," "Intemperance as a Cause of Poverty Greatly Reduced Since Prohibition" and "Drink A Great Cause of Immorality." The poster "Drink A Great Cause of Immorality" showed the results of a study of 865 Immoral Inebriate Women, claiming that 40% of their immorality was due solely to drink, including as evidence a statement by a medical expert: "There is no apparent reason why any of the persons…should have become immoral but for preceding alcoholism." "Intemperance as a Cause of Poverty Greatly Reduced Since Prohibition" presented a graph that tracked the drop in poverty as a result of increased temperance, therefore conflating intemperance and immoral behavior with greater social ills like poverty.

Posters are a powerful form of propaganda; their succinct and striking messages create a sense of urgency. In a poster, complex and extensive information must be condensed into a few words and images. Temperance and Prohibition Era posters did just this, using startling information and making emotional appeals to Americans' most deeply held morals and values.

A significant amount of Temperance and Prohibition Era propaganda was targeted towards children. Since logical and scientific arguments may not have made sense to young children, the main rhetorical technique in children's pamphlets was pathos. This form of anti-liquor propaganda related children's emotional responses and experiences to moral issues.

The large quantity of temperance pamphlets targeted towards children was likely a result of Puritan ideology. According to the Puritans, children's moral education began at home; as the Puritan minister and saint Richard Greenham, wrote in his essay "Of the good education of children":

If parents would have their children blessed at church and school, let them beware they give their children no corrupt examples at home by any carelessness, profaneness or ungodliness. Otherwise, parents will do them more harm at home than both pastors and schoolmasters can do them good abroad. (Emerson 152)

Although these pamphlets are written for children, it is probable that they are also targeting parents. A central theme in many children's pamphlets is the role of parents in promoting temperance and how a child should react if his/her parent is intemperate.

Children's pamphlets generally began with an illustration and a story about a child or an animal whose experiences served as a subtle or direct warning against intemperance. The next section would usually contain a poem, dialogue or mini-story which reinforced the ideas presented in the first story. Many of these pamphlets also ended with advice, telling children to abstain from alcohol and to join the temperance crusade. Two examples of children's pamphlets are "Grandmother's boy (1880s)" and "Look out for the trap! (1870s)"

The cover story of "Grandmother's boy" deals directly with Puritan values concerning salvation and good parenting. In the pamphlet's opening story, a little boy who has been raised by his pro-temperance grandmother pays his father a visit. The father is a wealthy, educated man who is enjoying a bottle of wine with his friends. The son, who has taken the temperance pledge, embarrasses his father, asking him why he is drinking alcohol, and then says: " 'If I'd known you drinked such stuff, I shouldn't wanted to come and see you. It makes folks drunkards, and makes them so wicked they can't go to heaven (3-4).'" The child's reaction to his father's drinking appeals to pathos, especially fear, in two ways. First, it plays upon parents' fear that their children will lose respect for them and not want to spend time with them. Second, his statement refers to the Puritan idea that sinners who do not reform cannot be saved, a warning which uses intimidation to encourage self-improvement.

The following section in the pamphlet "Grandmother's boy" is a poem titled "Johnny's Soliloquy," which expresses the messages of the first story even more explicitly. The poem encourages children to serve as models to their parents, as in the phrase, "The boy is father to the man (3)" which is repeated throughout the poem. By taking the temperance pledge of total abstinence from alcohol and encouraging their parents to do so, children modeled the Puritan ideal of saving oneself and others.

The last two paragraphs of the "Grandmother's Boy" titled "Stand Firm!" make a stirring call to arms. Describing temperance as the "way of truth and right (4)," this section of the pamphlet reads like an excerpt from a passionate sermon. It draws upon the crusade concept, telling the reader that "God will help us" and that the struggle against temptation is a fight children can and must win.

The children's pamphlet "Look out for the trap!" also warns against the dangers of temptation. This pamphlet begins with a picture and story of two squirrels. As in an Aesop's fable, the two squirrels come into trouble as a result of their own foolishness - both fell prey to temptation - and there is a moral at the end of the story: "Children, avoid temptation. Always be sure there is no trap beyond" (2). In this story the trap beyond is set by Charlie Wood, who tempts the squirrels into his home with good food. Once Charlie slams the door shut, the squirrels realize that "they were no longer their own masters" (2). Charlie's imprisonment of the squirrels is analogous to, as temperance supporters would have put it, a drunkard's enslavement to drink.

The story of the two squirrels ends with an anecdote. The narrator switches from third person omniscient to a more conversational, first person, telling the reader he saw a young boy give in to temptation. Worst of all, the one who tempted him was his mother. This final appeal to pathos is meant to shock both children and parents and to show children that even though their parents may have the best intentions, those intentions may be wrong and harmful.

The second part of "Look out for the trap!" is a short story titled "Why Joseph Signed the Pledge." The story draws upon a common theme in Temperance propaganda: a child living in poverty whose father is a drunkard and therefore cannot provide for his family. The story evokes a great deal of pity for Joseph, the protagonist, who is taunted by a wealthier classmate. "Oh! You needn't feel so big…" says the classmate, "your folks are poor and your father is a drunkard" (3).

The story describes the Puritan ideal of redemption through self-improvement and helping others. Joseph's mother reminds him to depend upon his own energies, trust in God and remember that he is responsible only for his own faults (4). Joseph remembers his mother's advice and, through his hard work and determination achieves the epitome of the Protestant work ethic, becoming "a useful and respected man." He follows the Puritan value of individual and communal improvement by helping his father become "a sober man and 'respected by other folks'" (4). The boy who taunted Joseph in school, however, lives to see his wealthy father become poor and a drunkard.

Joseph's story concludes with a piece of advice: "Boys, never twit another for what he can not help" (4). The moral of the story is a direct reference to the gold rule (i.e. Do unto others as you would have them do unto you) and appeals to human compassion, kindness and respect.

"Grandmother's boy," "Look out for the trap" and many other children's pamphlets present a dilemma whose solution is temperance. The dilemma is an extreme situation, often of pain, suffering or another intense emotion which must be immediately and directly addressed. Abstinence from alcohol is always the happy ending - as soon as the characters in the story swear off spirits they become successful, happy and achieve salvation.

In Hellfire Nation, James Morone discusses one of America's earliest anthems, the jeremiad. Dating back to the seventeenth century, the jeremiad was "a lament that the people have fallen into sinful ways and face ruin unless they swiftly reform" (14). The jeremiad described specific crimes which had invoked God's wrath, scolding Americans for their moral degeneracy, and reminding people of "their mission with an immodest goal: redeem the world" (Morone 42, 45).

The poems and songs of the Temperance and Prohibition Eras were direct descendants of the jeremiad. Like the jeremiad, these poems and songs defined a specific problem, intemperance, its ruinous effects on both individual and society, and the need for personal and communal responsibility and reform. Three central themes in Temperance era songs and poetry were the drunkard's story, the crusade and temperance as a form of liberty.

Although their themes were similar to other Temperance and Prohibition Era propaganda, songs and poems had a distinct style and structure. Unlike scientific and religious pamphlets, posters, and children's pamphlets, which used text and images, songs and poems formed part of an oral tradition. While a reader can always re-read a complex argument or refer to a new fact or statistic in a text, a listener cannot re-hear a song or poem. As a result, the songs and poems are more repetitive and direct, drawing upon common themes and widely accepted ideas rather than introducing new information. Like children's pamphlets, Temperance and Prohibition Era songs and poems use pathos more or less exclusively.

Many songs and poems speak specifically to the plight of drunkards, both as an example of the dangers of intemperance and to encourage people to join the temperance crusade. Religious references are especially prevalent: alcohol is described as an evil temptation and the devil's agent. Drunkards are those who have fallen from grace; they have lost control of their lives and sunk to ruin and damnation. According to these poems and songs, alcohol is to blame for most of society's ills. Once complete abstinence is achieved, prisons will empty, crime will cease, humanity will be saved and the kingdom of heaven will reign on earth.

The poems "The Curse of Rum (1800s)" and "The Face Upon the Floor (early 1900s)" and the song "The Drunkard's Fall (early 1900s)" depict the dangers of drinking and the plight of the drunkard. "The Curse of Rum" draws upon common religious themes in order to demonize alcohol. The poem describes rum as the serpent from the Garden of Eden, a "soul destroyer" (1) that has destroyed the paradise of the home by bringing disease and sin into society.

The underlying message in these songs and poems is not to take the first drink, because once people begin, they lose control and cannot stop. According to "The Face Upon the Floor" and "The Drunkard's Fall," even the most successful and promising individuals can fall prey to alcohol's evils once they take their first drink. "The Face Upon the Floor" depicts a penniless, filthy, wretched drunkard who wanders into a bar and tells a group of young men his story, from wealth, good looks and a loving wife to how drinking led him to current state, and then falls to the floor dead. "The Drunkard's Fall," whose subtitle reads "a warning for all college men wherein is declared how a Yale man was fired yesterday for over-cutting" describes how even the best and the brightest fall to ruin once they take to drinking. As the refrain states: "He was a Yale man, but he done all wrong." The young man becomes apathetic, lazy and eventually goes insane from drinking. Neither he nor the drunkard in "The Face Upon The Floor" can achieve the goals of the Protestant work ethic or reach spiritual salvation. Their alcohol abuse has taken away their capabilities for productivity and success, both on earth and in the world to come.

Songs and poetry make more direct appeals to pathos than other types of temperance propaganda because of their oversimplification and use of hyperbole. Oftentimes the title of a song or poem is enough to evoke a strong emotional response, as in the case of the song title "Father's a Drunkard and Mother is Dead (1866)." Song and poem titles may give a clear warning or command, like the songs "Girls, Wait For A Temperance Man (1867)" and "Help The Fallen Brother (mid to late 1800s)." The first song is a reference to the Puritan ideal of good parenting and addresses both children's' and parents' fears that children will not be taken care of and even abandoned. "Help The Fallen Brother" is a clear appeal to compassion and the Puritan idea that everyone must be reformed in order for a community to achieve success and salvation.

The solution to these individual and social ills, as mentioned in other types of Temperance Propaganda, was the crusade. The first verse and chorus of the "Anti-Saloon Battle Hymn (1907)" for example, provides a rousing call to arms:

The might are gathering for conflict; / The right is arrayed against wrong; / The hosts of the righteous are singing, / And this is the voice of their song: — Cho. — The Saloon, it must go! Do you hear us?/ Repeat it again and again. They strive to make millions of money;/ We strive to save hundreds of men!

As in Bishop Nicholson's address, the enemy, in this case the saloon, is clearly defined and its motives are proclaimed immoral and unjust. The battle hymn describes the saloon as an "awful, unspeakable monster" and asks God to free the people of the United states from its shackles.

Metaphors of slavery and liberation and their relationship to the temperance crusade are a significant aspect of Temperance era songs and poetry. The song "Emancipation (1914)" speaks of America as a nation with "True liberty so grand,/ that makes men free" and alcohol as a monster that enslaves Americans. The song conflates the crusade's mission with Puritan ideals of personal and communal salvation, ending with the stanza:

This is the hope of all / To see the traffic fall, / And not one slave. Then wave from sea to sea, / By union temperance plea, / Old Glory's jubilee, / Our nation free!

Even the most convincing anti-temperance supporter would have been hard pressed to refute the stanza above. It makes a powerful appeal to pathos, addressing many Americans' pride in their freedom and faith. How could anyone question such fundamental beliefs? And, if anyone did, who would listen?

Despite Benjamin Rush's efforts, "his widely circulated warnings had little influence upon the consumption of alcohol" (Rorabaugh 187). In fact, alcohol consumption actually rose during Rush's anti-liquor crusade and did not begin to decrease until the early 1830s (Rorabaugh 187). W.J. Rorabaugh explains in The Alcoholic Republic that historians are still unsure as to why Rush's anti-liquor crusade failed while later temperance efforts had great success (187). I propose that the answer lies in the rhetoric.

Benjamin Rush took a logos approach to promoting temperance, noting the harmful physiological effects of alcohol. He did not appeal to pathos until the end of "The Effect of Ardent Spirits Upon Man," when he described the moral depravity and social ills caused by alcohol consumption. Rush's use of pathos may have been too little too late. The weakness of using a logical argument is that it can be refuted, either with other logical explanations, new information or emotional appeals. It is harder to question people's emotions and deeply held morals and values. To do so would not only be considered offensive, it would also be futile. As I wrote earlier, how could anyone question such fundamental beliefs? And, if anyone did, who would listen?

Temperance and Prohibition Era propaganda were founded on pathos. Although a number of pamphlets drew upon both logos and pathos, many forms of propaganda, including children's pamphlets, songs and poems, used only emotional appeals. Temperance and Prohibition Era propaganda appealed to deeply held beliefs, based upon Puritan ideology and all-American values. While Rush's more scientific arguments could be disputed or ignored, most Americans would not question the importance of God, hard work, personal and communal salvation and freedom.

Works Cited

- "A Way to Make Money and a Better Way." Westerville, Ohio: American Anti-Saloon League Press Bureau, 19--?. Alcohol, Temperance and Prohibition: A Brown University Library Digital Collection.

Written in partial fulfillment of requirements for UC 116: Drug and Alcohol Addiction in the American Consciousness (Professor David Lewis — Fall 2004)

What Does the Bible Say About Drinking? Uncovering Scriptural Perspectives

- December 21, 2023

Biblical Perspectives on Alcohol and Drinking

Exploring the Bible provides varied perspectives on alcohol, showcasing its potential as a blessing and its dangers when abused.

The scriptures reflect on wine’s role in festivities, warnings against drunkenness, and guidance for leaders concerning alcohol consumption.

Old Testament References

In the Old Testament, wine is frequently mentioned.

For example, Proverbs 20:1 highlights that wine can lead to mockery and beer to brawling, pointing to the negative outcomes of excessive drinking.

Isaiah also speaks on the matter, cautioning against the lure of alcohol in Isaiah 5:11, where the pursuit of drink from morning to night is depicted as leading people astray.

Wine as a Gift and a Curse

The Bible portrays wine as both a blessing and a potential curse depending on its use. Ecclesiastes 9:7 encourages to “Go, eat your bread with joy, and drink your wine with a merry heart,” suggesting approval in moderation.

Conversely, passages like Proverbs 23:31–35 describe wine as deceptive when it “sparkles in the cup” and can lead to “woe, sorrow, and strife” when consumed in excess.

Leadership and Alcohol

Leadership roles within the scriptures come with particular warnings concerning alcohol.

"None of the wicked will understand, but those who are wise will understand." - (Daniel 12:10)

What does this mean for you ? Learn more here .

In Proverbs 31:4-5, it’s advised that it’s not for kings, O Lemuel, nor for rulers to crave wine.

Similarly, 1 Timothy 3:8 calls for deacons in the church to be worthy of respect, sincere, and not indulging in much wine, emphasizing sobriety and self-control.

The Role of Self-Control

A recurring theme in the Bible regarding alcohol is the necessity of self-control. Galatians 5:19-21 lists drunkenness among the acts of the flesh that are incompatible with inheriting the kingdom of God.

Titus also speaks of the virtues in leaders, where being “not given to drunkenness” is part of being upright and holy.

This section has made efforts to directly address the biblical meaning or relevance of the keywords through links and references to scripture, maintaining a friendly tone while remaining informative.

Frequently Asked Questions

When exploring what the Bible says about the use of alcohol, several questions frequently arise.

These questions touch on sin, moderation, Jesus’s actions, celebrations, various translations, and the distinction between moderate drinking and excess.

Is it considered a sin to consume alcohol in Christian teachings?

In Christian teachings, consuming alcohol is not universally regarded as a sin, but there is a clear warning against the abuse of alcohol .

The key is moderation and avoiding behaviors that lead to drunkenness.

What scriptural passages offer guidance on drinking wine in moderation?

Scriptural passages suggest that wine is a gift from God but also caution against its excess.

Verses such as Ephesians 5:18, which says “And be not drunk with wine, wherein is excess; but be filled with the Spirit,” offer guidance on drinking wine in moderation .

Can you provide instances where Jesus himself drank wine?

Jesus is recorded to have consumed wine in the New Testament, notably at the Last Supper.

John 2:1-11 details the first miracle of Jesus , turning water into wine at the wedding at Cana, indicating that He participated in social traditions involving wine.

How does Christian scripture address alcohol consumption and festive celebrations?

Christian scripture acknowledges that wine can be a part of festive occasions.

Psalm 104:14-15 praises God for the bounty of the earth, including “wine that gladdens human hearts,” suggesting a positive view of alcohol in celebratory contexts, when used responsibly.

What perspective does the King James Version present on the consumption of alcoholic beverages?

The King James Version of the Bible presents a balanced view on alcohol consumption, with verses like Proverbs 20:1 acknowledging that wine can be a mocker and beer a brawler, cautioning against overindulgence.

Does religious scripture differentiate between drinking in moderation and drunkenness?

Religious scripture clearly differentiates between moderate drinking and drunkenness.

Passages such as Galatians 5:19-21, which list drunkenness as an act of the flesh, draw a distinction, emphasizing that drunkenness is opposed in both the Old and New Testaments.

You may also like

Evening Prayer: Embracing Peace Through Nightly Devotion

- January 23, 2024

What is a Revival? Understanding Spiritual Renewal and Cultural Resurgence

- December 23, 2023

Romans 5:8 – Unpacking the Depths of God’s Love Through Scripture

- January 16, 2024

Document Deep Dive

This Chart From 1790 Lays Out the Many Dangers of Alcoholism

Founding father Benjamin Rush was greatly concerned with the amount of booze imbibed in post-Revolution America

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

Megan Gambino

Senior Editor

After the Revolutionary war, Americans were drinking staggering amounts of alcohol. Tastes were swiftly changing from ciders and beers, the preference of colonial times, to hard liquors from the nation’s earliest distilleries. By 1830, each person, on average, was swilling more than seven gallons of alcohol per year.

“The tradition in a lot of communities was to have a drink for breakfast. You had a drink mid-morning. You might have whiskey with lunch. You had a beer with dinner, and you ended with a nightcap,” says Bruce Bustard, a curator at the National Archives in Washington, D.C. “There was a fair amount of alcohol consumption by children too.”

Alcohol was thought to stave off fevers and ease digestion. “If you did not drink, you were endangering your health,” says Mark Lender, a historian and coauthor of Drinking in America . “There was a point at which you could not buy life insurance if you did not drink. You were considered ‘crank-brained.’”

So, when Benjamin Rush, a signer of the Declaration of Independence and foremost physician, spoke of the evils of hard liquor, people thought he was nuts. He published an essay, “An Inquiry Into the Effects of Ardent Spirits Upon the Human Body and Mind” in 1785, and to a later edition of the essay, released in 1790, he attached a dramatic illustration titled “A Moral and Physical Thermometer.”

The thermometer, now on display in “Spirited Republic: Alcohol in American History,” an exhibition at the National Archives through January 10, 2016, charts the medical conditions, criminal activities and punishments that could come from the frequent drinking of particular cocktails and liquors. Punch, for instance, could cause idleness, sickness and debt. Toddy and egg rum might elicit peevishness, puking and a trip to jail. And, drinking drams of gin, brandy and rum day in and day out was rock bottom as far as Rush was concerned. That habit could lead to murder, madness and, ultimately, the gallows.

Already a vocal proponent of women’s rights and mental health and prison reform, Rush emerged as a great champion of temperance, says Lender. His ideas may have been shocking in his time, but his essay became a bestseller and gradually much of the medical community would see, like he did, that chronic drunkenness itself was a disease. In the 1820s, when the temperance movement was picking up steam, early advocates adopted Rush’s thinking, cautioning against distilled liquors while condoning the drinking of beer, cider and wine in moderation. This distinction between hard liquors and other alcoholic beverages later fell away with the decades-long push for teetotalism, or a complete abstinence from alcohol. Prohibition took effect in 1920, and the 21st amendment repealed the ban on the production, sale, importation and transportation of alcohol 13 years later.

“The conception we have of addiction today can generally be traced back to Benjamin Rush,” says Lender. “There was a point, Rush believed, that the substance, in this case alcohol, controlled the individual rather than the other way around. He thought there was a physical dependence engendered in the body. He was a pioneer.”

Click on the pins on the document to learn more.

“Spirited Republic: Alcohol in American History” is on display in the Lawrence F. O’Brien Gallery of the National Archives through January 10, 2016.

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

Megan Gambino | | READ MORE

Megan Gambino is a senior web editor for Smithsonian magazine.

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 59, Issue 4

- The evils of drink and the temperance pioneers

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- John R Ashton

- North West Public Health Team, Department of Health, 18th Floor, Sunley Tower, Piccadilly Plaza, Manchester M1 4BE, UK; johnrashtonblueyonder.co.uk

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

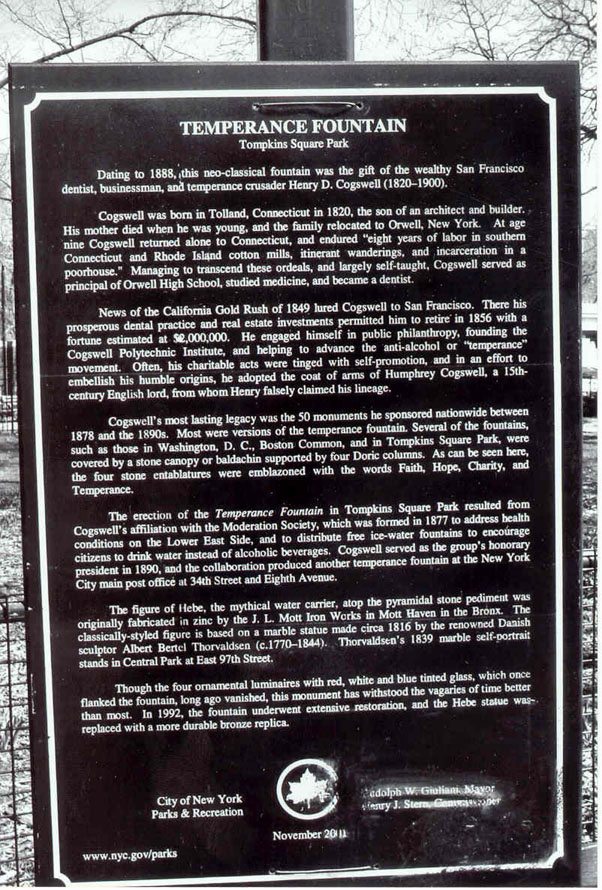

Alcohol has periodically been regarded as a public health curse around the world. Two examples here from Cork in Ireland and from New York City illustrate some of the artefacts of the temperance movement in the 19th century.

In New York, wealthy San Francisco born dentist, businessman, and temperance crusader, Henry D Cogswell (1820–1900) proved as committed and energetic as Father Mathew. He campaigned tirelessly to promote the consumption of water rather than alcohol. Cogswell’s memorial is this Temperance Fountain, erected in Tomkins Square Park in New York City.

Surrounded by a simple, classical Doric columned, open temple structure—with a stepped, pyramidal stone pediment—the structure is topped by the classical figure of Hebe, a mythical Greek water carrier (sculptor: Albert Bertel Thorvaldsen c1770–1844).

Supplementary materials

Web-only figures

Statue of Father Mathew, Cork, Ireland

Temperance Fountain, Tomkins Square Park, New York, USA

Files in this Data Supplement:

Linked Articles

- In this issue Is epidemiology popular enough? Carlos Alvarez-Dardet John R Ashton Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 2005; 59 253-253 Published Online First: 14 Mar 2005.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

The Good and Evil of Alcohol

Why do people drink why do they abstain.

Posted May 27, 2010

"If you mean the demon drink that poisons the mind, pollutes the body, desecrates family life, and inflames sinners, then I'm against it. But if you mean the elixir of Christmas cheer, the shield against winter chill, the taxable potion that puts needed funds into public coffers to comfort little crippled children, then I'm for it. This is my position, and I will not compromise!"

- A Congressman's response about his attitude toward whiskey.

We are returned to this politician's "insight" (is that the same thing as "equivocation") by "a major new study" (French) referenced in the Telegraph (U.K.): "Moderate drinkers have lower rates of heart disease, obesity and depression than people who abstain from alcohol entirely, the report indicates." Meanwhile, a Spanish study found recently, drinkers are less likely to succumb to Alzheimer's.

Personal disclosure : I earn my living from treating alcoholism and addiction , as well as writing and lecturing about them. I have also received money from alcohol producers. I receive many times as much for the former through my Life Process Program, which is the basis for a residential treatment center - as much in a good month as I have received in the last decade from the latter. I was an adviser on substance use disorders in the American Psychiatric Association's manual, DSM-IV .

Publication disclosure : In the August issue of Addiction Research and Theory, I have a commentary entitled, "Alcohol as Evil - Temperance and Policy" and a rejoinder to comments—one from an English-speaker, the other Italian—entitled, "Civil War in Alcohol Policy: Northern vs. Southern Europe."

A brief history of alcohol in America : Americans drank between three and four times as much per capita in the Colonial period as they do today. Since then, alcohol use has ebbed and flowed in arcing cycles in the United States; a national binge at the turn of the twentieth century led to Prohibition from 1920-1933. Sociologists have analyzed Prohibition as a war between a nativistic Protestant America and an immigrant Catholic one. Cities dominated by immigrants—like New York, Boston, and Detroit—barely acknowledged Prohibition. This split, although attenuated, is still highly evident in America. Twice the percentage of residents of Northeastern states drink alcohol (although still only about two thirds) as do in Southern states such as Kentucky and Tennessee (one third).

But wait. The last two states (33 percent and 30 percent drinkers respectively) are famous whiskey-distilling and moonshine states. Ah, therein lies a story. A remarkable number of Southern counties are still "dry," requiring people to drive to neighboring counties to drink or to drink illegally produced alcohol - both of which are associated with binge drinking.

A brief international analysis of alcohol consumption : After decades of casual observations that Scandinavians and English-speakers are binge drinkers and Southern Europeans drink wine casually with meals, the European Comparative Alcohol Study (ECAS), conducted by Scandinavians, found this was true. Scandinavians, the English and Irish are frequent bingers; Greeks, the Spanish, Italians and French rarely binge. But here's the rub - not only do the latter nations have fewer alcohol-related social problems, they actually have lower death rates due to drinking, even though Southern nations, due to their steady imbibing, drink more! Remarkably, ECAS found an inverse correlation between the amount of alcohol consumed in a country and that country's rate of alcohol-related mortality.

So some people drink alcohol well and healthily; and some binge, which can result in deadly accidents and culminate in periods—perhaps lifetimes—of alcohol abuse and alcoholism.

Is alcohol good or bad? As comments on this post may indicate, people hold different opinions. For some, the deathly, disease-like traits of the substance predominate; for some, the positive, fun and even health-seeking aspects prevail.

Positive and negative attitudes towards alcohol and good and bad experiences with alcohol are related. But—oh, the paradox—the former precede and determine the latter. The Telegraph article cited above noted that, while "recent research has highlighted the health-giving properties of wine and some other alcoholic drinks, the authors of the latest study sound a note of caution."

It may not be that alcohol produces these benefits, but that people who lead good lives are moderate drinkers, not teetotalers. What does this say about what we should teach about alcohol? People with better lives have more positive views of alcohol and alcohol contributes to their lives. (Residents in my treatment program—this does not include you—you have reached a different place at this point in your lives!)

P.S. Please don't send me comments like one I listened to from an active woman alcoholic (NOT a patient): "Don't tell me that your parents teaching you how to drink prevents you from becoming alcoholic—my father took me and my sister into the basement and made us both drink until we became sick—then he said, 'See what drinking does!' And look what happened to me."

I feel she missed my point. She's an example of how conveying negative attitudes about alcohol becomes self-fulfilling. On second thought, go ahead and make such comments.

Copyright (c) Stanton Peele, Ph.D.

Stanton Peele, Ph.D., J.D., is the author of A Scientific Life on the Edge: My Lonely Quest to Change How We See Addiction . He has worked in the addiction field since the publication of Love and Addiction in 1975.

- Find Counselling

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- Richmond - Tweed

- Newcastle - Maitland

- Canberra - ACT

- Sunshine Coast

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Search Menu

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Alcohol and Alcoholism

- About the Medical Council on Alcohol

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Contact the MCA

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, the gin epidemic, the ‘inferior sort of people’, drunkenness, national security, general conclusions and comments.

- < Previous

THE GIN EPIDEMIC: MUCH ADO ABOUT WHAT?

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Ernest L. Abel, THE GIN EPIDEMIC: MUCH ADO ABOUT WHAT?, Alcohol and Alcoholism , Volume 36, Issue 5, September 2001, Pages 401–405, https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/36.5.401

- Permissions Icon Permissions

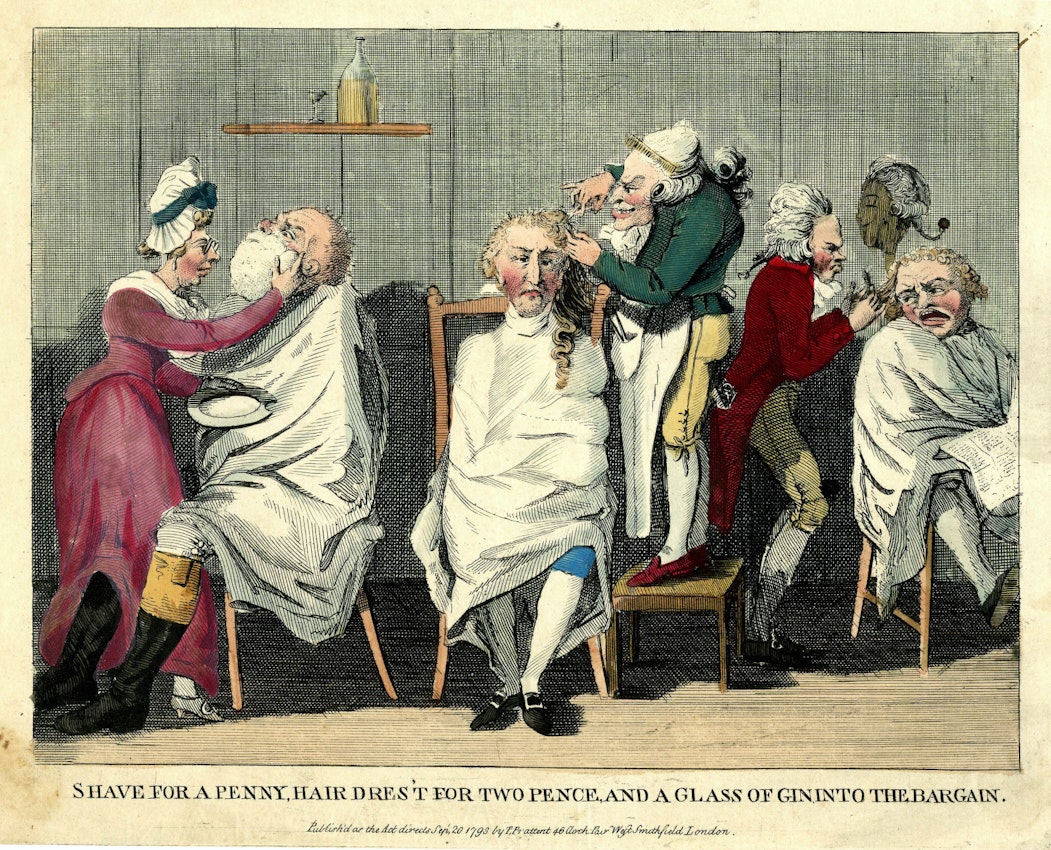

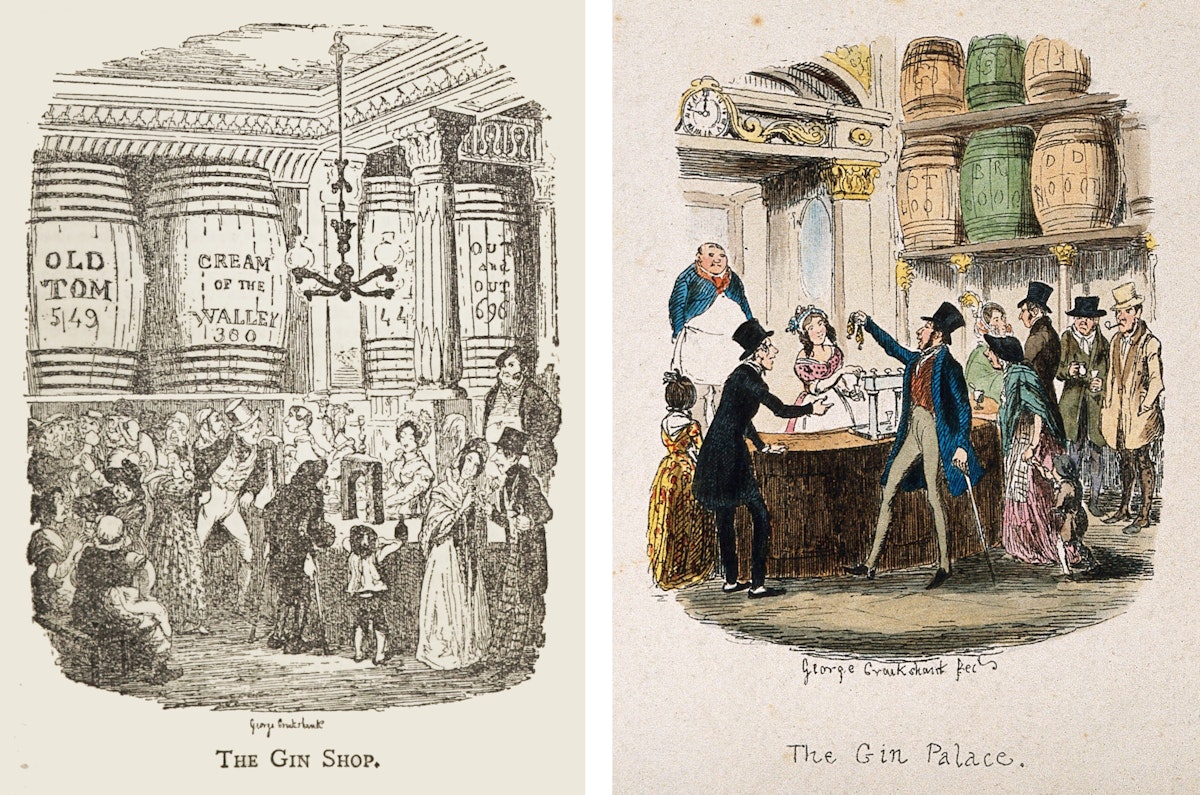

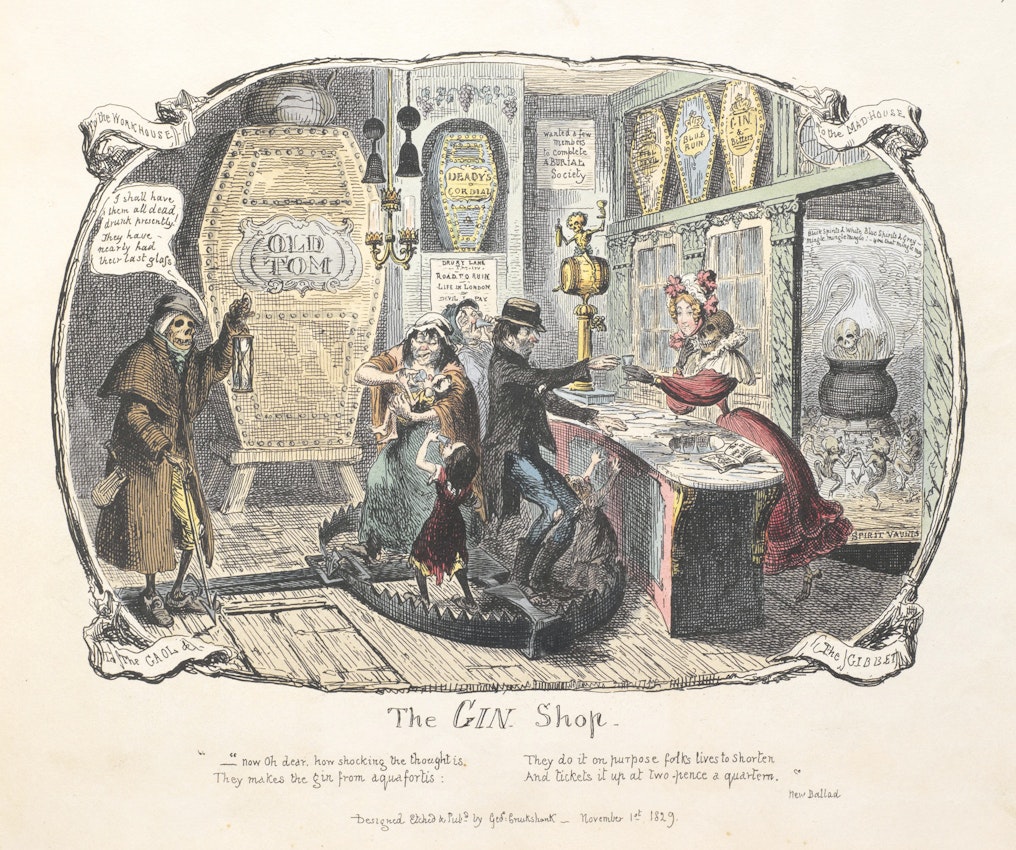

— While there is no doubt that the era of the ‘gin epidemic’ was associated with poverty and social unrest, the surge in gin drinking was localized to London and was a concomitant, not the cause, of these problems. The two main underlying social problems were widespread overcrowding and poverty. The former was related to an unprecedented migration of people from the country to London. The latter stemmed from an economic ideology called ‘poverty theory’, whose basic premise was that, by keeping the ‘inferior order’ in poverty, English goods would be competitive and would remain that way since workers would be completely dependent on their employers. Widespread overcrowding and poverty led to societal unrest which manifested itself in increased drunkenness when cheap gin became available after Parliament did away with former distilling monopolies that had kept prices high. Reformers ignored the social causes of this unrest and, instead, focused on gin drinking by the poor which they feared was endangering England's wealth and security by enfeebling its labour force, and reducing its manpower by decreasing its population. Part of this hostility was also related to gin itself. While drunkenness was often spoken of affectionately when it was induced by beer, England's national drink, gin was considered a foreign drink, and therefore less acceptable. These concerns were voiced less often after the passage of the Tippling Act of 1751, which resulted in an increase in gin prices and decreased consumption. However, the second half of the century was also a period in which England's military victory over the French gave it new wealth and power, which dispelled upper-class fears about an enfeebled and dissolute working class. It was also an era when new public health measures, such as mass inoculation against smallpox, and a decrease in the marrying age, led to a population increase that dispelled reformist fears about manpower shortages. The conclusion is that, while the lower cost of gin sparked the ‘gin epidemic’, the social unrest associated with this unprecedented surge in gin consumption was exacerbated, rather than caused, by the increase in drinking.

Any history of the ‘evils’ of alcohol will inevitably mention the ‘gin epidemic’, which allegedly besotted England, between 1720 and 1751, and will probably rely on George's (1925/1966) frequently republished graphic account for documenting that history (e.g. Coffey, 1966 ). However, the ‘gin epidemic’ did not occur in a vacuum. This article discusses the nature of the ‘epidemic’, and its social and economic background. A consideration of the gin epidemic in its context, offers a different interpretation of its causes and impact than that suggested by the standard histories of that period such as M. Dorothy George's (1925/1966).

Distillation was common throughout Europe by the Middle Ages, but was fairly uncommon in England, compared to beer and ale production, because a domestic monopoly kept prices very high. In 1689, Parliament banned imports of French wines and spirits and at the same time cancelled the domestic monopoly. Subsequently, anyone who could pay the required duties could set up a distillery business. Distillers became not only producers, but also sellers. The cost of gin fell below the cost of beer and ale (see Spring and Buss, 1977 ) and gin drinking became the favourite alcoholic beverage among the ‘inferior class’.

British statistical abstracts put the annual consumption of gin in England and Wales in 1700 at about 1.23 million gallons. By 1714, consumption was up to almost 2 million gallons per year. By 1735, it was 6.4 million gallons, and by 1751, 7.05 million gallons. In terms of population, per capita consumption increased by up to eightfold from between 1 and 2 pints in 1700 to between 8 and 9 pints, about a gallon per person in 1751 ( Mitchell and Deane, 1962 ). Beer consumption for the same period remained relatively constant at 3 million gallons a year.

George, one of the most influential historians of the early 20th century, blamed the increase in gin consumption for much of the social unrest that also increased during this period (e.g. George, 1925 /1966; Coffey, 1966 ). The most commonly cited support for this argument was that after the passage of the Tippling Act of 1751, which George called a ‘turning point in the social history of London’ ( George, 1925 /1966, p. 49), social unrest declined. The Tippling Act prohibited distillers from selling gin at retail, and levied severe penalties for non-compliance, such as imprisonment, whipping and even deportation for repeat offenders. As a result, gin prices rose, gin consumption steadily declined back to 2 million gallons [beer consumption, however, steadily increased to about 4 million gallons a year ( Mitchell and Deane, 1962 )], and social unrest did decline. However, in this article, I argue that the social unrest prior to and after the Tippling Act was the result of, and was fuelled and exacerbated by, excessive gin drinking, rather than having been its cause.

At the beginning of the 18th century, English society was divided into two basic classes. One, composed of gentlemen, employers and literary figures, was known as the ‘genteel’ class; the other, described by the Middlesex Grand Jury as ‘the meaner, though useful Part of the Nation’, ( Anonymous, 1736 b ), consisted of ‘Day-labourers, men and women Servants, and common Soldiers’. These manual or menial labourers, were also variously called the ‘inferior sort of people’, the ‘inferior rank’, the ‘lower sort’, or the ‘lower orders’ ( Eboranus, 1736 ; Wilson, 1736 ; Miege, 1748 ; Fielding, 1751 ). Though inferior in social status, labourers were the backbone of the nation's prosperity. To maintain that prosperity, ‘reasonable creatures’, the Middlesex Grand Jury's term for its own ‘genteel class’, strongly endorsed what has come to be known as ‘poverty theory’. The basic premise of this theory was that the genteel class comprised England's consumers and the ‘inferior class’ its producers. The wages of the latter of necessity had to be kept low to keep exports competitive and commodities beyond the income of its members, so that they would be forced to work steadily to survive. The corollary to this idea was that the more children these people produced, the greater would be the competition for jobs and the lower the wages that would have to be paid to do them. This in turn meant higher profits and a greater dependence on the part of workers ( Marshall, 1956 ; Gilmour, 1992 ). This theory was buttressed by an underlying belief that God himself had ordained that the ‘inferior class’ had been put on earth to serve the genteel class and the existing social order was a reflection of His will. The clergy supported this assumption with statements to the effect that ‘there can be no society without Government, and no Government without Subordination, or Submission of Inferiors to Superiors.’ (Quoted by Malcolmson, 1981 , p. 15.) Poverty theory took a new direction in Thomas Malthus' (1789) Essay on Population , which contended that while a larger population meant a larger working force, the poor had to be kept in abject poverty to avoid a food crisis that would endanger the welfare of their betters.

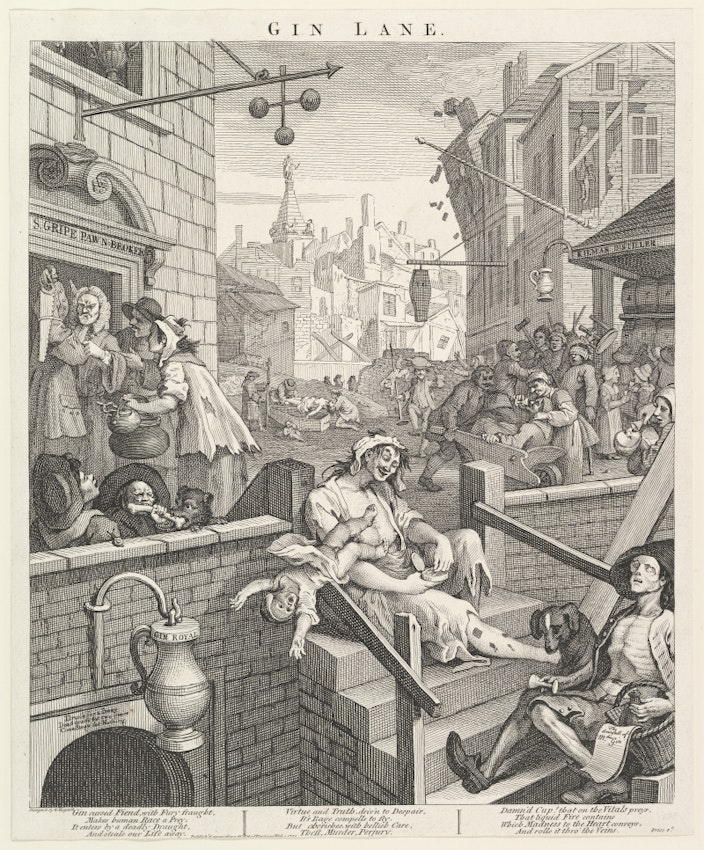

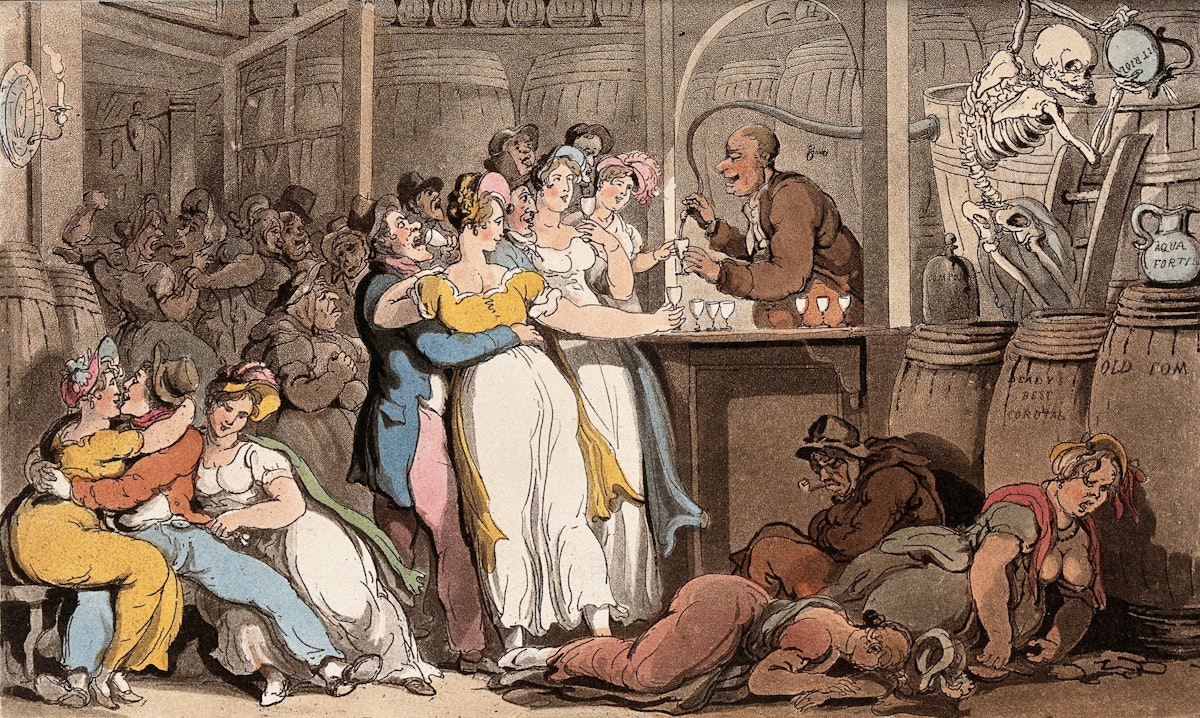

Whereas the gin-related drunkenness in 18th century England has typically been associated with the poor, drunkenness itself was commonplace among all social classes. However, the attitudes of the genteel towards their own drunkenness and those of the ‘inferior people’ reflected class distinctions. For the middle and upper classes — the only ones to record their perspective — their own drunkenness was simply amusing. In his Midnight Modern Conversation , for example, William Hogarth depicted drunkenness among well-to-do revellers in a humorous light; the whole scene triangulates on an exuberant drinker in the back of the room who is raising his glass in a toast to all his fellow topers, a tribute, rather than a denunciation of drunken conviviality ( Shesgreen, 1973 ). When Hogarth turned to drinking among the poor, as he did in Gin Lane , his attitude was completely different ( Abel, 2001 ).

Gin drinking among the ‘inferior class’ in the second quarter of the 18th century was attacked as an unprecedented problem not because drunkenness was more commonplace, or because of benevolent concern that it was impairing the health of the poor as individuals, but because of its perceived dangers to the Nation's welfare and economy. When a critic of cheap gin said that ‘it cannot be suppos’d that labouring people can spend their money in both beer and gin’, he wasn’t condemning drunkenness per se , he was merely pointing out that the money being spent was going to the gin makers and sellers instead of their counterparts in the beer industry. In the long run, he warned, the cheaper price for gin would lead to more drunkenness, which was a concern, he said, because their premature deaths would ‘deprive the landowners of a workforce which in turn would result in higher wages, (and) the demand for barley would also be reduced’ ( Holden, 1736 , p. 9). ‘To all this’ (i.e. the decrease in beer consumption and increased labour costs), our social critic added, was the added effect gin drinking had upon ‘the consumption of tobacco, no inconsiderable a branch of his Majesty's revenue, and to which the populace do not a little contribute. An honest man may smoak [ sic ] a pipe or two of tobacco, with a pint or two of good beer, a whole evening, but is so suddenly demolish'd by the force of tyrant gin, that he has scarcely time to puff out half a dozen wiffs' (p. 13).

When the London Grand Jury met at the Old Bailey in 1735 to present to the Lord Mayor ‘such publick Nusances as disturb and annoy the Inhabitants of the City’, among its main complaints was that gin was robbing the ‘lower kind of people’ of their will and power ‘to labor for an honest livelihood, which is a principal Reason of the great Increase of the Poor’ (pp. 2–3). The reason the ‘lower kind’ had no will to labour on behalf of those making this complaint, however, was not because gin enfeebled them, but because they were unwilling to work at hazardous jobs for long hours and low pay. Adam Smith, for instance, noted that, even the most fit carpenters in London did not remain so for more than 8 years, and at the height of their earning capacity, hardly earned enough to buy a newspaper ( Jarrett, 1974 ). In an unusually candid comment, one of the genteel class, an Arthur Young, admitted that ‘nobody but an idiot would expect them to work at such a rate, unless it was their only way of earning their living’ ( Jarrett, 1974 , p. 98). To keep their employees dependent, employers were especially reluctant for them to form and join unions referred to as ‘combinations’, because of the expectation that unionizing would lead to demands for higher wages. Such grievances and concerns were typically couched in terms of the national interest. Employers specifically blamed pub owners for providing a place for workmen to meet and use and for encouraging ‘these journeymen in their unlawful combinations for raising their wages, and lessening their hours’ ( Galton, 1896 ).

These social confrontations became more acute at the beginning of the 18th century as a result of the Enclosure Acts, which expropriated what previously little countryside had been held in common and used by any who cared to do so, and converted it into privately held fields by large landowners. Dispossessed of what little land they had been able to use and faced with extremely hard and oftentimes crippling farm labour that even the strongest couldn’t cope with for more than a few years ( Jarrett, 1974 ), people left their rural homes for cities, especially London. Once they arrived, many were often no better off since there was low demand in the cities and towns for unskilled labourers. Nevertheless, as more and more people migrated to London, serious overcrowding and unemployment occurred, especially for the unskilled, and wages were kept low, because the newcomers would work for less. Left with nothing to do, or unwilling to work for almost nothing, the ‘inferior sort of people’ who had some money repaired to their pubs which had become the centres of working class life in every community ( Spring and Buss, 1977 ); the rest coalesced into an unruly mob.

Not only was gin drinking accused of contributing to idleness, it was also said to be responsible for an increase in crime. ‘Most of the Murders and Robberies lately committed’, said the London Grand Jury ( Anonymous, 1736 a ), ‘have been laid and concentrated at Gin Shops’. It explained that ‘being fired with these Hot Spirits, they are prepared to execute the most bold and daring Attempts’ (p. 4). In 1751, despairing of the vices of the ‘lower order of people’, Henry Fielding, a London Magistrate, author of Tom Jones and other popular books of the era, published an Enquiry into the Causes of the Late Increase of Robbers explaining that there were two main causes of crime in England. The first was that the ‘lower order’ was no longer frugal and hardworking because of its wish for ‘luxury’; and this envy drove them to crime to achieve their goal. The second cause was drunkenness on the part of the ‘inferior order’.

While the crime rate did increase during the second quarter of the 18th century, it had been steadily increasing since the previous century ( Beattie, 1986 ) and would be expected to increase with an increase in population and overcrowding. When those factors are taken into account, the crime rate remained relatively stable during the first half of the 18th century during the height of the gin epidemic ( Beattie, 1986 ) and actually rose during the second half of the century, after the epidemic ended ( Langford, 1989 ). Although the ‘inferior class’ was at least as much under siege, ‘criminality, like poverty, is never at an acceptable level from the perspective of propertied classes’ ( Langford, 1989 , p. 155). Most capital crimes were offences against property ( Gilmour, 1992 ). London and Middlesex were considered the most lawless parts of the country, but fewer than 100 murders occurred there from 1749 to 1771 compared to 4000 in Rome, a city a quarter the size of London ( Gilmour, 1992 ). While crime was a perennial concern, the perception that the gin epidemic was responsible for an increase in crime was due more to its changing character and to the way in which the literate and semi-literate public was made aware of it through the growing influence of the popular press, rather than to any real increase in its incidence ( Langford, 1989 ).

To a large degree, the social unrest of the mob, which the genteel class equated with ‘lawlessness’, was due to sharply rising food costs throughout the 18th century. Labouring families spent as much as 50% and sometimes as much as 80% on essential foodstuffs, especially bread or grain. While they could barely make ends meet in good years, when prices shot up in times of poor harvests, families faced starvation. Rioting often occurred, and desperate people turned to robbery and other crimes for money ( Malcolmson, 1981 ), or to gin because it provided calories at a lower cost ( Spring and Buss, 1977 ), although it lacked associated nutrients.

Another of the constant concerns of the upper class was that gin drinking was undermining national security. ‘The Nation (if obliged to enter into a war) will want strong and lusty soldiers, the Merchant sailors, and the Husbandman Labourers’ warned the London Grand Jury ( Anonymous, 1736 a ), in arguing that if ‘the lower class’ continued to besot itself with gin, England would not have the manpower to win a war. Speaking on behalf of the upper class, Sir Robert Walpole and Sir Joseph Jekyll (1736) likewise denounced gin not only for contributing to ‘idleness’ and crime, but also for debilitating its collective manpower and, thereby, for undermining the ability of the Nation to defend itself.

The decreased price for gin and increased consumption in England, especially London, during the first half of the 18th century, occurred in the context of increased overcrowding and widespread poverty. The ‘epidemic’, however, was mainly confined to London, because gin was the preferred drink of the sedentary trades, such as weavers, which were situated in the cities. In the countryside, work was too strenuous for farmers to cope with constant hangovers and they continued to drink the traditional, and slower-acting, beer and ale ( Watney, 1976 ).

Despite the stressful overcrowding and poverty in London, European contemporaries visiting the city invariably wrote that the poor were better off there, than they were on the Continent, where there was no gin epidemic ( Marshall, 1956 ). The reason there was a ‘gin epidemic’ in London and not Paris, is that in London, prices for gin were lower than for beer and ale, whereas in Paris, they were higher than for wine, France's national drink. Wine consumption in Paris was about 40 gallons (155 litres) per person ( Brennan, 1989 ). If gin contained 40% alcohol and wine, 10%, England's 0.4 gallons at the height of the gin epidemic was about 10 times lower than France's 4 gallons per person. France's upper class did not approve of the level of consumption of its lower class, but did not become as strident in its outrage as its English counterpart until the next century, when its own national alcoholic drink was challenged by distilled spirits, which were of foreign origin.

Levels of consumption that are tolerated in different societies reflect underlying attitudes about public drinking as much as attitudes toward types of alcoholic beverages. Whereas France prided itself on its wine and its quality ( Brennan, 1989 ), England prided itself on its beer and ale ( Abel, 2001 ). In France, wine was called ‘boissons hygienique’, the ‘healthy drink’, to distinguish it from distilled drinks ( Brennan, 1989 ), whereas in England, Hogarth describes beer as the ‘happy produce of our Isle’ to distinguish it from gin ( Shesgreen, 1973 ).

In both cities, the common denominator of price influenced consumption among the lower classes, because they were the most responsive to price ( Abel, 1998 ). In England, there was a dramatic upsurge in consumption of gin in the first half of the 18th century, due to the abolition of distilling monopolies; in France, there was a corresponding surge in distilled spirits consumption the following century as a result of a phylloxera epidemic that destroyed the country's vineyards and caused an increase in wine prices. In neither country, however, was drunkenness itself considered a vice until much later ( Watney, 1976 ). As in England, French elites did not begin to criticize lower-class drinking until social unrest in that country coincided with the upsurge in consumption of distilled spirits, which became a metaphor for an irrational proletariat ( Brennan, 1989 ). Thus, one of the issues 18th century London and 19th century Paris had in common in their condemnation of drinking, was that the lower classes were drinking as much as they did.

Poverty was pervasive in 18th century Europe, regardless of whether people drank or did not drink gin, and poverty is strongly related to crime ( Abel, 1980 ). Drunkenness undoubtedly contributed to poverty, and hence crime, but both were also the result of poverty. Gin undoubtedly played a part in London's crime rates, but crime rates increased even more after gin drinking decreased. The same could be said of death rates due to drunkenness which increased from 17 in 1725 to 69 in 1735, but fell after 1736, even though drinking increased ( Clark, 1988 ). Gin drinking therefore could not have been the main factor influencing the crime rate.

Poverty has always been the ever constant handmaiden of crime and poor health, regardless of whether people use alcohol or any other drugs ( Abel, 1980 ; Abel and Hannigan, 1995 ). For the upper classes, which drank mainly beer and wine, gin, the preferred drink of the ‘inferior order’ because of its lower cost, was singled out as responsible for the social problems of the time. The prevailing opinion of the upper class was that, if members of the latter aspired to better themselves, they had but to give up their gin drinking and they would develop greater thrift and thereby improve their living conditions.

If the ‘gin epidemic’ were not the main reason behind the social unrest in London during the first half of the 18th century, how then are we to account for the decrease in upper class concerns about social conditions and unrest following the newly imposed restrictions on its sale and decreased gin consumption after the Tippling Act of 1751?